A Robust Complex α-Sigmoid Affine Projection Algorithm Under Non-Gaussian Noise

Abstract

1. Introduction

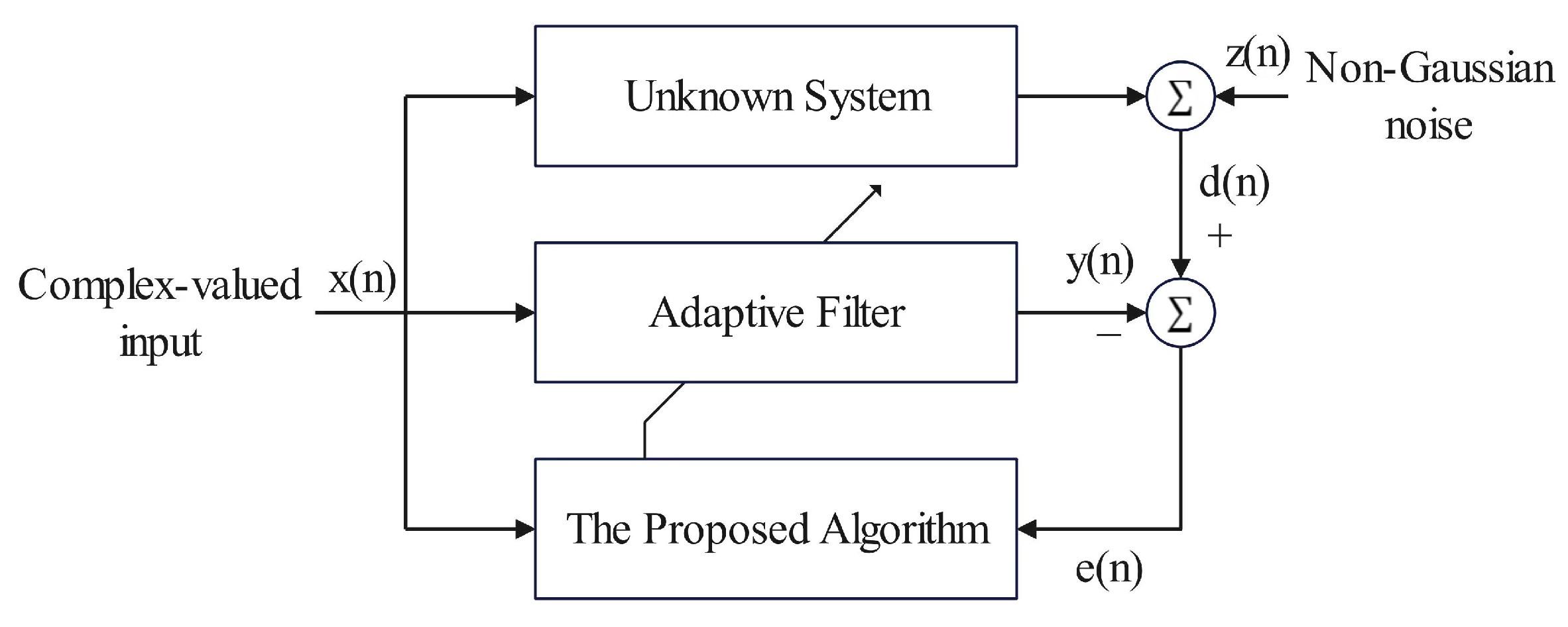

2. The Proposed -CSAP Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: The -CSAP Algorithm |

|

3. Theoretical Analysis

3.1. Unbiasedness in the Mean

- (A1) The input matrix is statistically independent of the weight error vector .

- (A2) In steady state, the diagonal weighting matrix varies slowly and can be approximated bywhere .

- (A3) is weakly correlated with and , while is zero-mean and independent of both.

3.2. Steady-State MSD Analysis

3.2.1. Theoretical Value Derivation

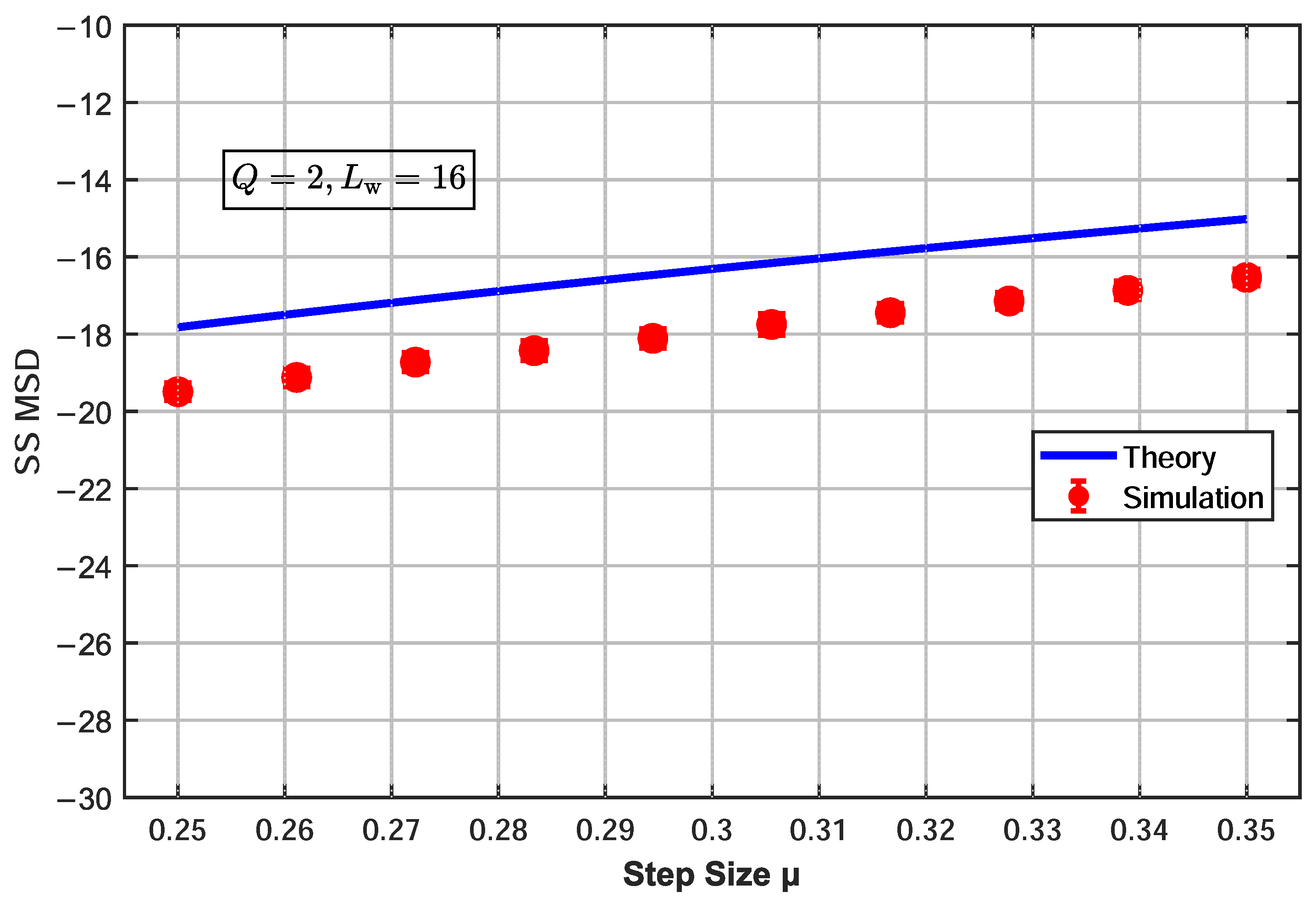

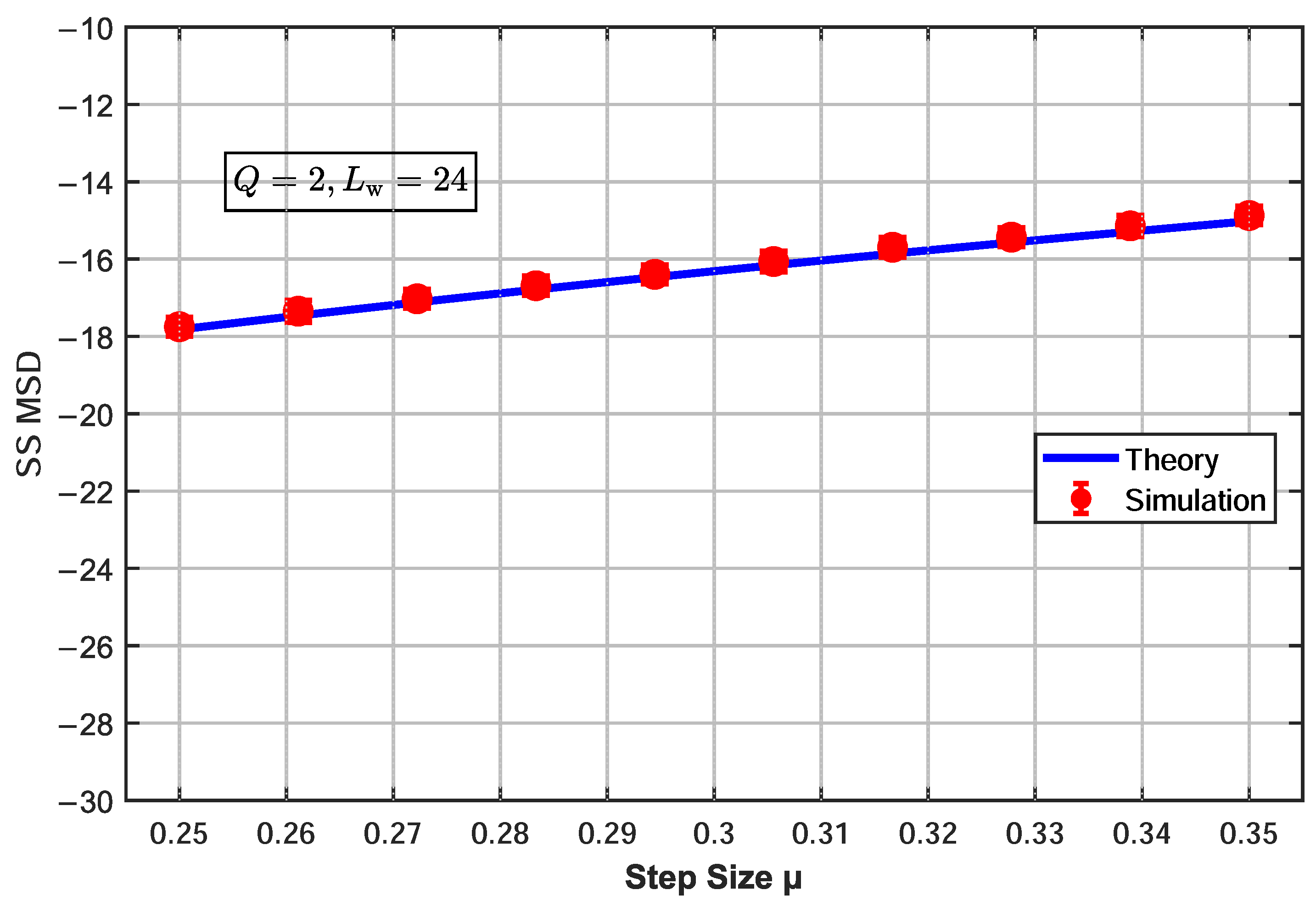

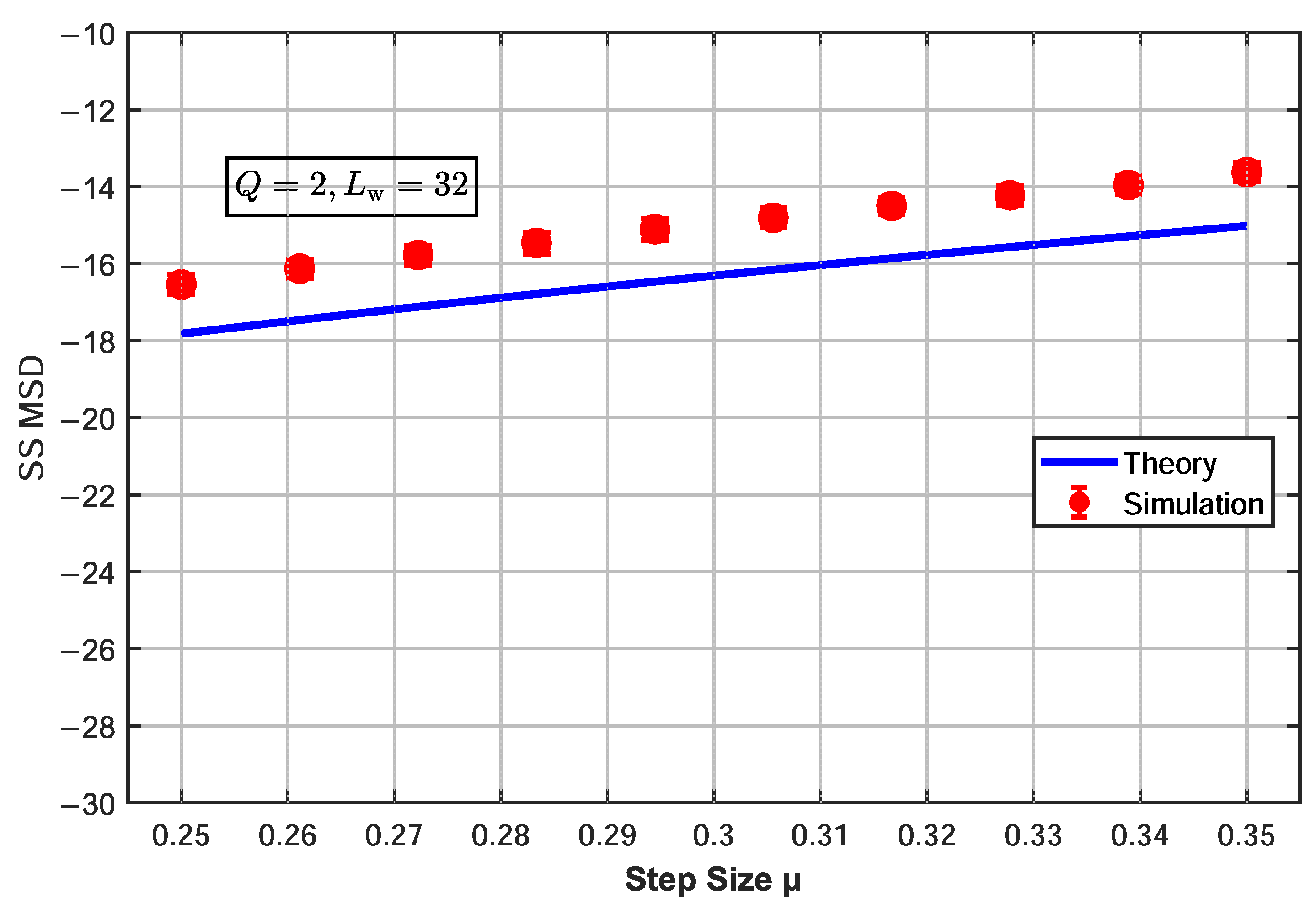

3.2.2. Theoretical Validation

3.3. Computational Complexity Analysis

4. Simulation

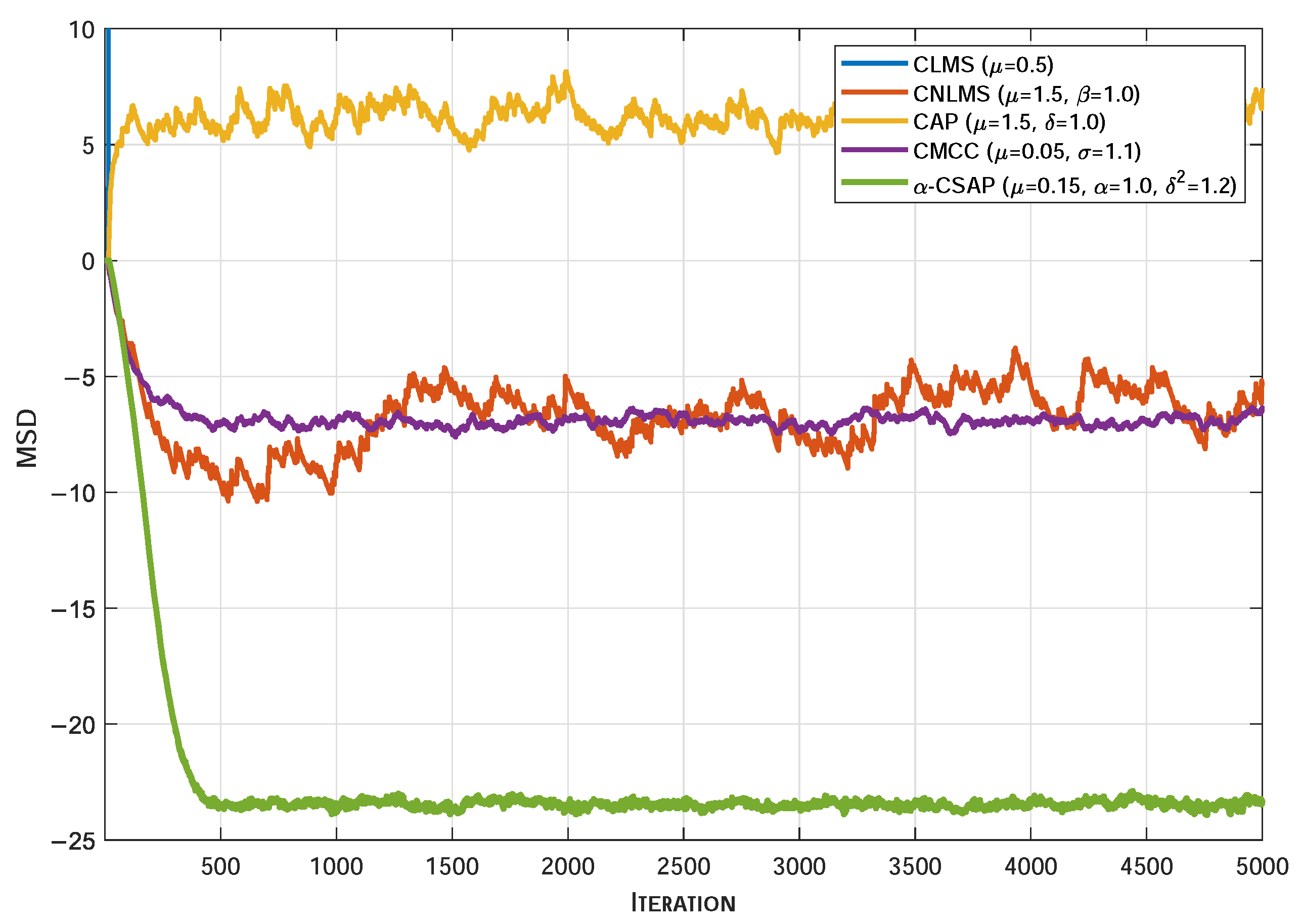

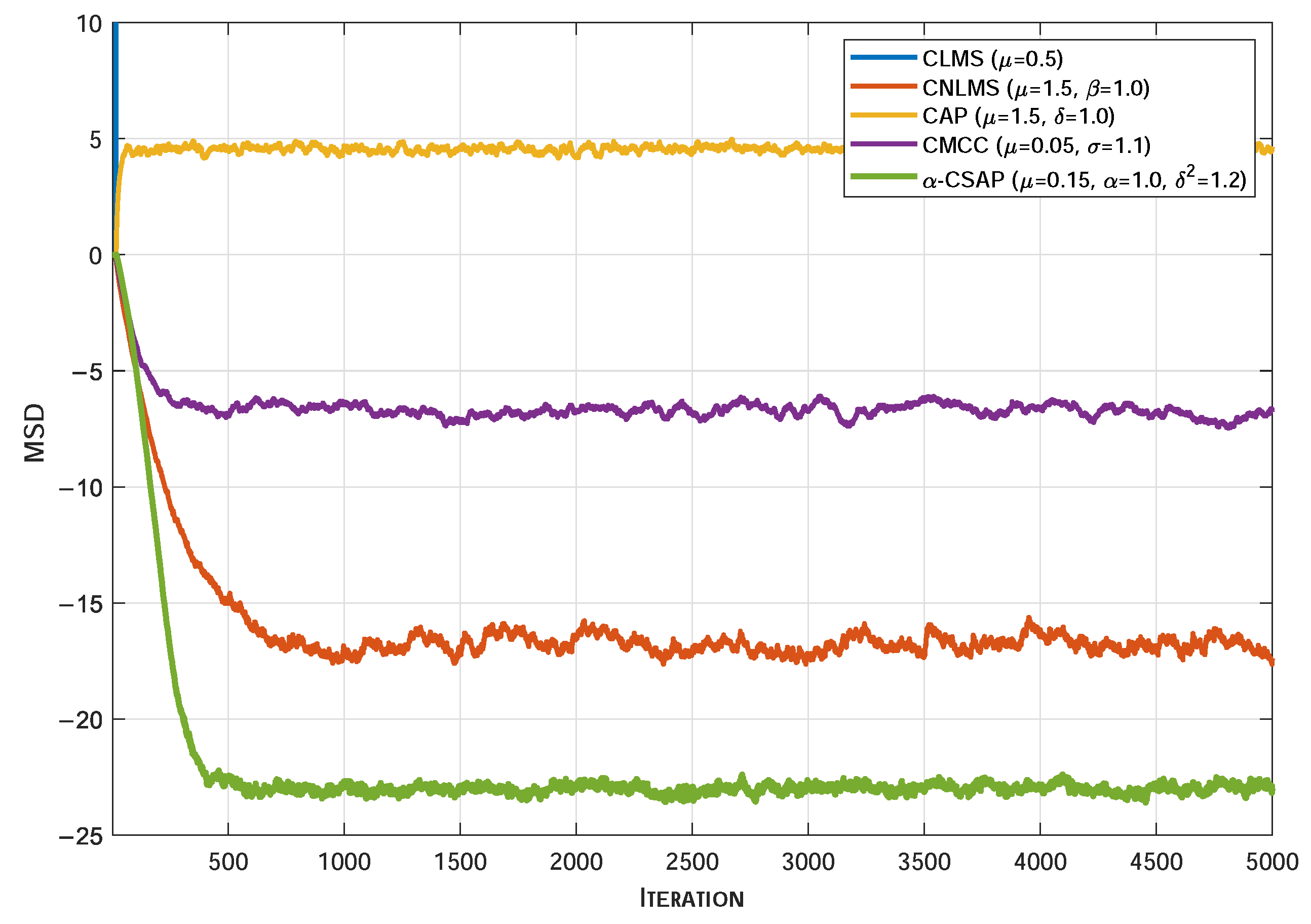

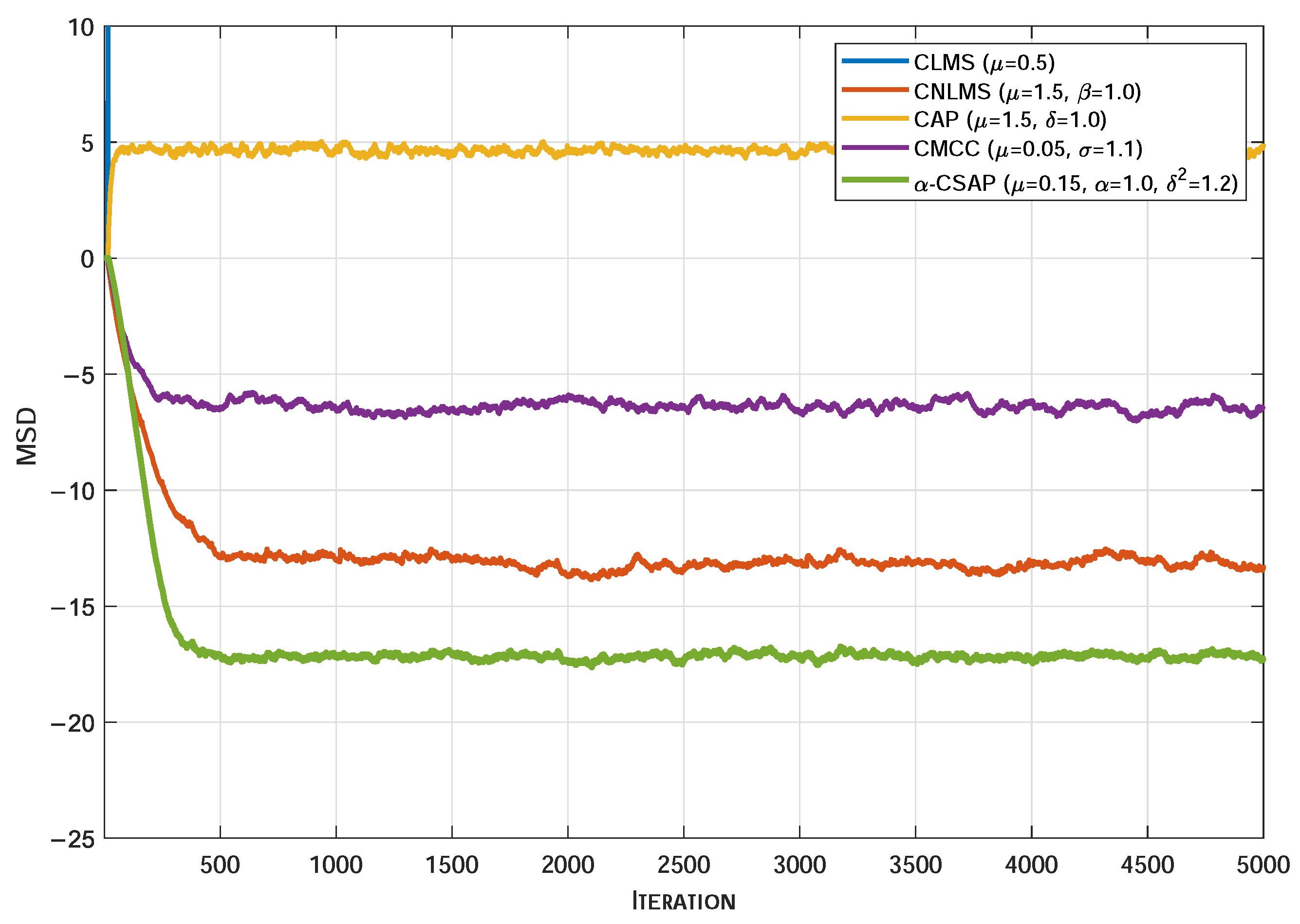

4.1. System Identification Application

- 1.

- Impulsive Mixture Noise with Bernoulli–Gaussian Structure: The composite noise is defined as . Here, denotes the background complex Gaussian noise of variance . The impulsive element is represented by , having a larger variance . A Bernoulli random variable , distributed as with , governs the occurrence of impulses: signifies no impulse, while its complement indicates an impulse event. All variables , , and are mutually independent.

- 2.

- Contaminated Complex Gaussian Noise (CG Noise): This noise model is synthesized by summing two independent zero-mean complex Gaussian components. The background component has a variance of 0.008 for the real part and 0.002 for the imaginary part. An intermittent impulsive component, with a variance of 8 for the real part and 2 for the imaginary part, is superimposed with an occurrence probability of 0.01. The combined signal exhibits a heavy-tailed distribution characteristic due to the occasional high-power impulses.

- 3.

- Symmetric Complex -Stable Noise (-Stable Noise): This model adopts a complex-valued symmetric -stable distribution, formulated by . The real component and imaginary component are generated as independent and identically distributed real -stable random variables, described by the distribution . The configuration employs the following: characteristic exponent , symmetry parameter , scale parameter , and location parameter .

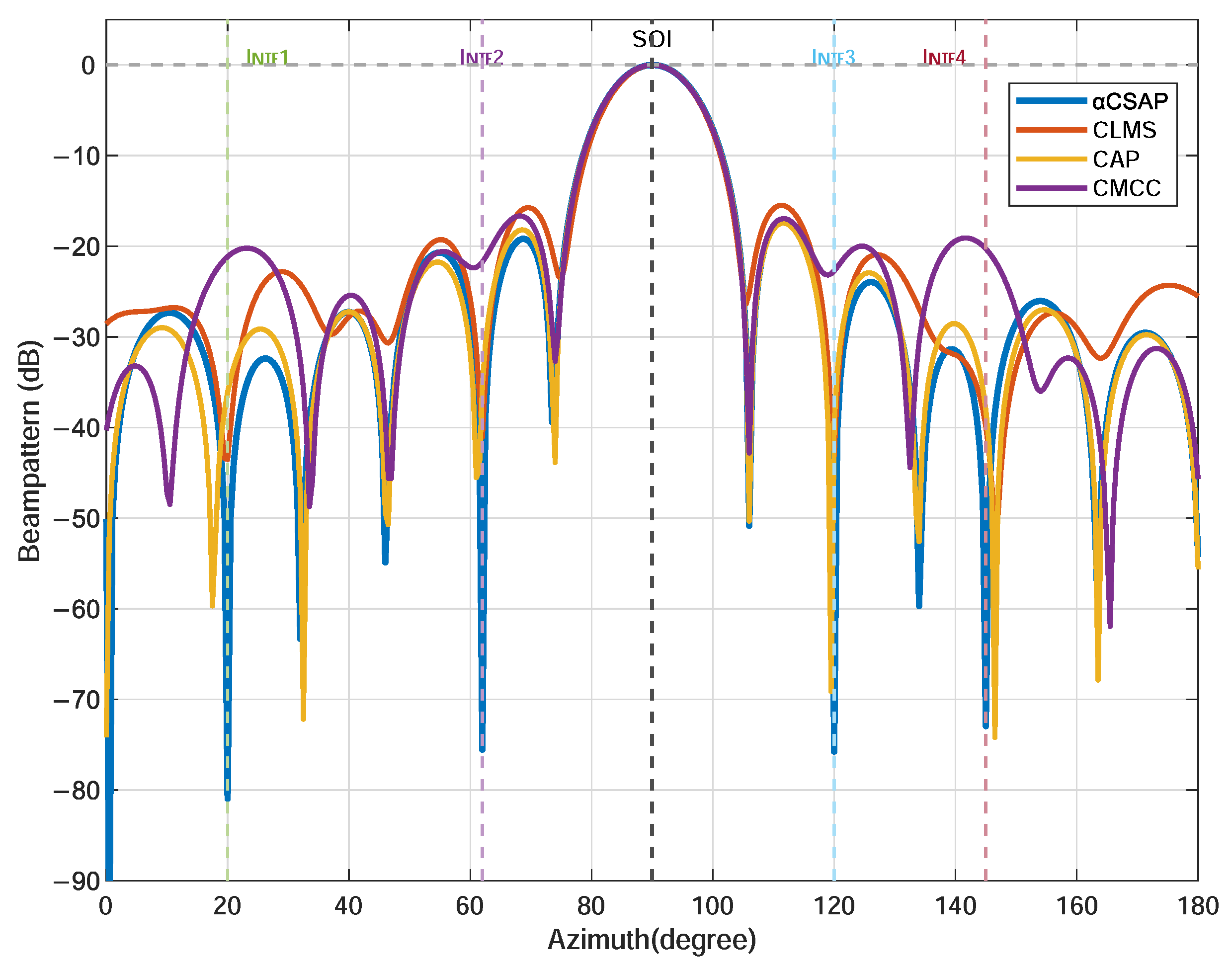

4.2. Beamforming Application

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| -CSAP | Complex -Sigmoid Affine Projection |

| MSD | Mean Square Deviation |

| LMS | Least Mean Square |

| RLS | Recursive Least Squares |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| AP | Affine Projection |

| CLMS | Complex Least Mean Square |

| CNLMS | Complex Norm Least Mean Squares |

| CAP | Complex Affine Projection |

| CMCC | Complex Maximum Correntropy Criterion |

| CG Noise | Contaminated Complex Gaussian Noise |

| -Stable Noise | Symmetric Complex -Stable Noise |

| QPSK | Quadrature Phase Shift Keying |

| DOA | Direction Of Arrival |

| INR | Interference-to-Noise Ratio |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| INR | Interference-to-Noise Ratio |

| SINR | Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio |

References

- Hassani, S.A.; van Liempd, B.; Bourdoux, A.; Horlin, F.; Pollin, S. Joint In-Band Full-Duplex Communication and Radar Processing. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 3391–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Yang, X. Target Tracking Method Based on Scale-Adaptive Rotation Kernelized Correlation Filter for Through-the-Wall Radar. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, W.; Zhou, W. Robust Cognitive Radar Tracking Based on Adaptive Unscented Kalman Filter in Uncertain Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 163405–163418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Adaptive PHD Filter with RCS and Doppler Feature for Space Targets Tracking via Space-Based Radar. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 3750–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-S.; Dao, D.-T.; Chien, H. Ship Echo Identification Based on Norm-Constrained Adaptive Beamforming for an Arrayed High-Frequency Coastal Radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramgiri, M.; Nooshabadi, S.; Olutomilayo, K.T.; Fuhrmann, D.R. Automotive Radar-Based Hitch Angle Tracking Technique for Trailer Backup Assistant Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 1922–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Lu, Z.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, B. Marine Radar Image Sequence Target Detection Based on Space–Time Adaptive Filtering and Hough Transform. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 13506–13522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, R.; Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Balz, T. A Modification to the Complex-Valued MRF Modeling Filter of Interferometric SAR Phase. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2015, 12, 681–685. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Huang, Y.; Guan, J. Adaptive Clutter Suppression and Detection Algorithm for Radar Maneuvering Target with High-Order Motions Via Sparse Fractional Ambiguity Function. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Wang, B.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, B. Enhanced Long Baseline Underwater Target Localization with Adaptive Track-Before-Detect Method. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 31, 1710–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohal, P.; Ochodnicky, J. Particle Filter Optimization for Adaptive Radar Data Processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 New Trends in Signal Processing (NTSP), Demanovska Dolina, Slovakia, 14–16 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, G.; Zhang, Y. Analysis and Comparison of RLS Adaptive Filter in Signal De-noising. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electrical and Control Engineering, Yichang, China, 16–18 September 2011; pp. 5754–5758. [Google Scholar]

- Took, C.C.; Mandic, D.P. The Quaternion LMS Algorithm for Adaptive Filtering of Hypercomplex Processes. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009, 57, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic, D.; Goh, V. Complex Valued Nonlinear Adaptive Filters: Noncircularity, Widely Linear and Neural Models; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, C.; Qian, G.; Wang, S. Widely Linear Maximum Complex Correntropy Criterion Affine Projection Algorithm and Its Performance Analysis. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 3540–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Qian, G.; Wang, S. Bias-Compensated MCCC Algorithm for Widely Linear Adaptive Filtering with Noisy Data. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 3587–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Mei, J.; Iu, H.H.C.; Wang, S. Fixed-Point Maximum Total Complex Correntropy Algorithm for Adaptive Filter. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 2188–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Ning, X.; Wang, S. Recursive Constrained Maximum Correntropy Criterion Algorithm for Adaptive Filtering. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 2229–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandarani, M.Z. Investigation of Energy Consumption in WSNs Within Enclosed Spaces Using Beamforming and LMS (BF-LMS). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 63932–63941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Bando, Y.; Mimura, M.; Itoyama, K.; Yoshii, K.; Kawahara, T. Unsupervised Speech Enhancement Based on Multichannel NMF-Informed Beamforming for Noise-Robust Automatic Speech Recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 27, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Su, H.-J.; Takano, Y. Underdetermined AOA Estimation Using Non-Uniform Sub-Connected Hybrid Beamforming Systems. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S. Affine Projection Versoria Algorithm for Robust Adaptive Echo Cancellation in Hands-Free Voice Communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 11924–11935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.-R.; Wu, S.-T.; Tsao, H.-W.; Diniz, P.S.R. Correntropy-Based Data Selective Adaptive Filtering. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeki, K.; Umeda, T. An Adaptive Filtering Algorithm Using an Orthogonal Projection to an Affine Subspace and Its Properties. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 1984, 67, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.J.; Zhao, H.Q.; Lv, S.H. Robust Constrained Affine-Projection-Like Adaptive Filtering Algorithms Using the Modified Huber Function. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey Vega, L.; Rey, H.; Benesty, J. A New Robust Variable Step-Size NLMS Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2008, 56, 1878–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Jin, J.; Mei, S. L0 Norm Constraint LMS Algorithm for Sparse System Identification. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2009, 16, 774–777. [Google Scholar]

- Bhotto, M.Z.A.; Ahmad, M.O.; Swamy, M.N.S. Robust Shrinkage Affine-Projection Sign Adaptive-Filtering Algorithms for Impulsive Noise Environments. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 3349–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.V.S.; Martins, W.A.; Diniz, P.S.R. Affine Projection Algorithms for Sparse System Identification. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 May 2013; pp. 5666–5669. [Google Scholar]

- Bhotto, M.Z.A.; Antoniou, A. Affine-Projection-Like Adaptive-Filtering Algorithms Using Gradient-Based Step Size. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Pap. 2014, 61, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleologu, C.; Benesty, J.; Ciochina, S. A Variable Step-Size Affine Projection Algorithm Designed for Acoustic Echo Cancellation. IEEE Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2008, 16, 1466–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, C.; Miao, Y.; Zakharov, Y.; Diniz, P.S. An α-Sigmoid Affine Projection Algorithm for In-Car Echo Cancellation and Channel Estimation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 10297–10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | × | + | ÷ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization: | ||||

| 1. | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2. , | Q | 0 | 0 | |

| 3. | Q | 0 | ||

| 4. | 0 | Q | ||

| 5. | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6. | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7. | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8. | 0 | 1 | ||

| Total | Q | |||

| Algorithm | × | + | ÷ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLMS | 0 | 0 | ||

| CNLMS | 0 | 1 | ||

| CMCC | 1 | 0 | ||

| CAP | 0 | 0 | ||

| -CSAP | Q |

| Algorithm | Final SINR (dB) | SINR Improvement (dB) | Interference Direction (dB) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20° | 62° | 120° | 145° | |||

| -CSAP | 34.72 | +61.02 | −80.95 | −75.53 | −75.76 | −72.94 |

| CLMS | 18.72 | +45.02 | −43.52 | −41.05 | −43.10 | −39.92 |

| CAP | 11.44 | +37.74 | −36.14 | −35.33 | −39.49 | −38.04 |

| CMCC | 12.27 | +38.57 | −21.15 | −21.73 | −22.72 | −20.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Guo, B.; Qian, G. A Robust Complex α-Sigmoid Affine Projection Algorithm Under Non-Gaussian Noise. Sensors 2026, 26, 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030961

Guo Y, Guo B, Qian G. A Robust Complex α-Sigmoid Affine Projection Algorithm Under Non-Gaussian Noise. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):961. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030961

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yaowei, Bin Guo, and Guobing Qian. 2026. "A Robust Complex α-Sigmoid Affine Projection Algorithm Under Non-Gaussian Noise" Sensors 26, no. 3: 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030961

APA StyleGuo, Y., Guo, B., & Qian, G. (2026). A Robust Complex α-Sigmoid Affine Projection Algorithm Under Non-Gaussian Noise. Sensors, 26(3), 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030961