Performance Assessment of Portable SLAM-Based Systems for 3D Documentation of Historic Built Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art and Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Studies

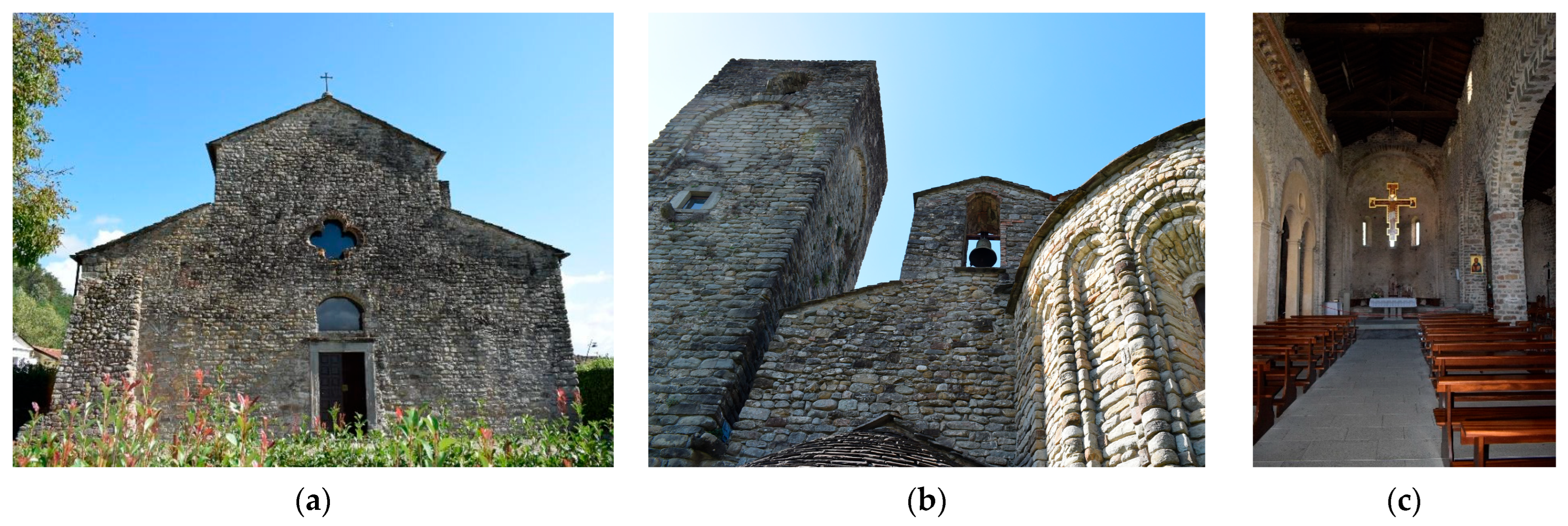

3.1.1. Pieve di Santo Stefano in Sorano

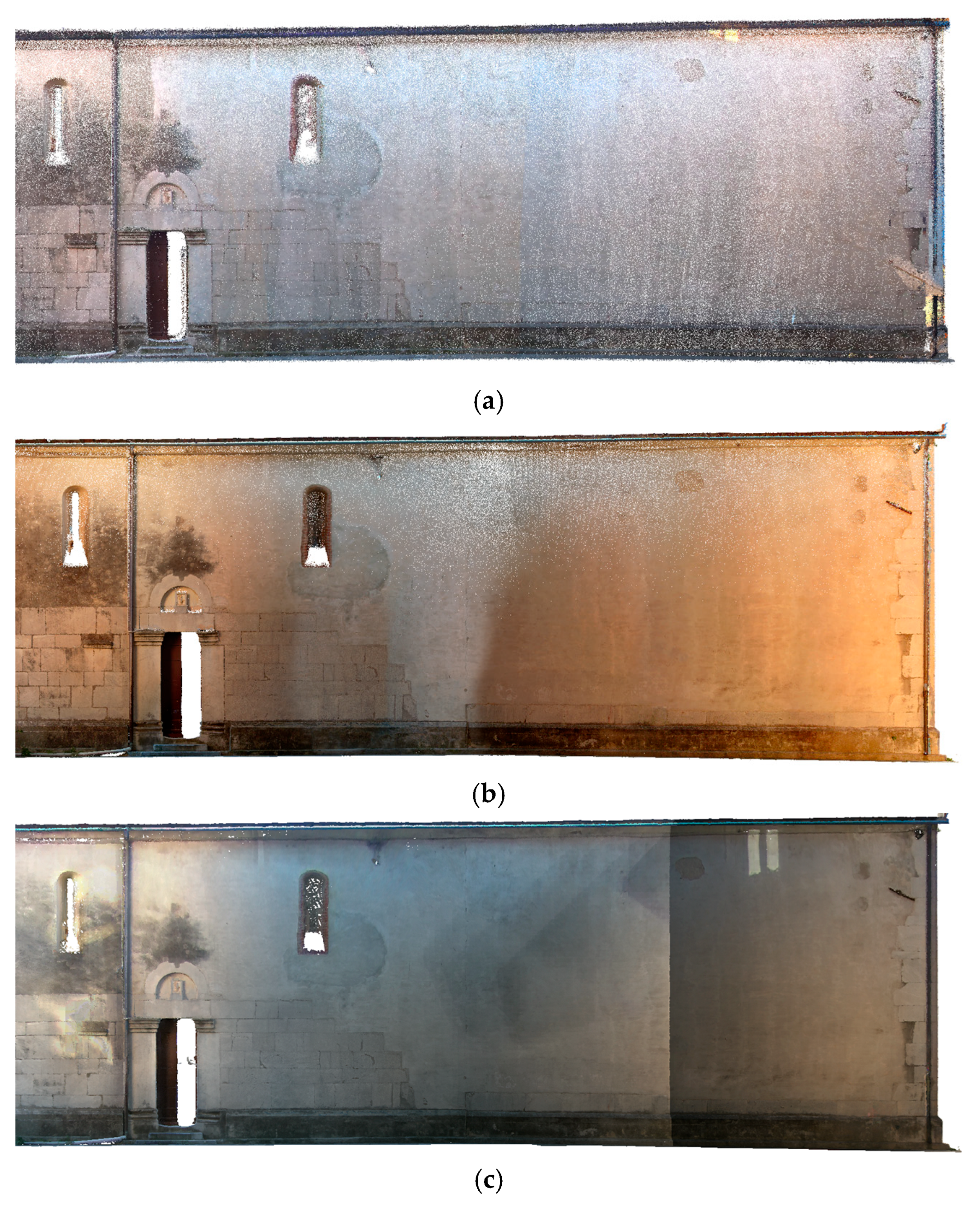

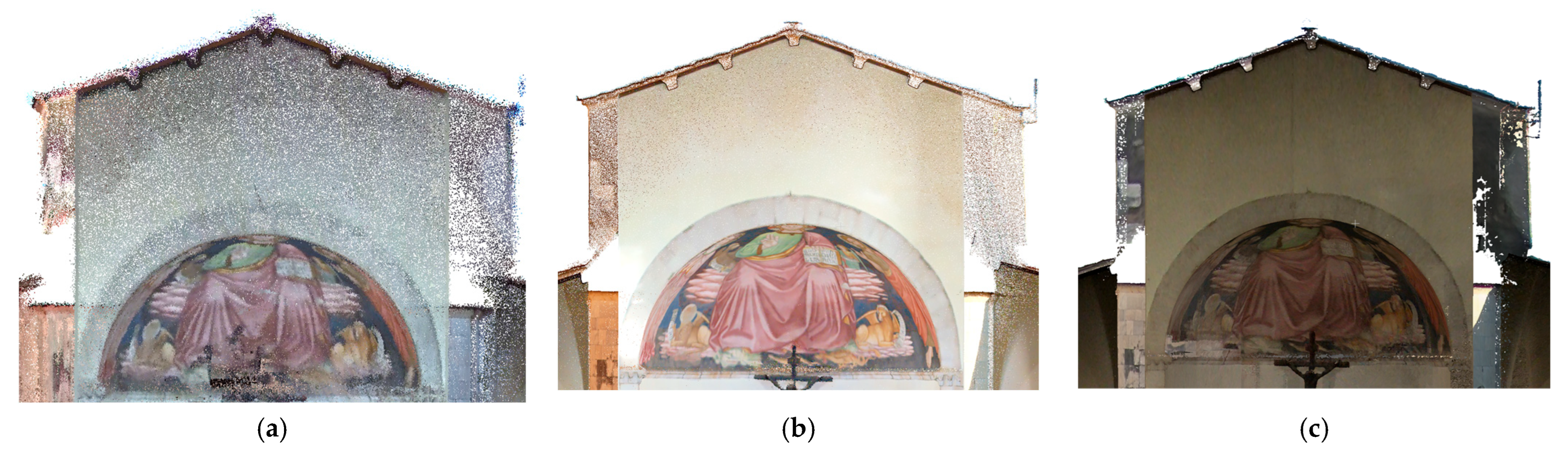

3.1.2. Pieve di Santo Stefano in Vallecchia

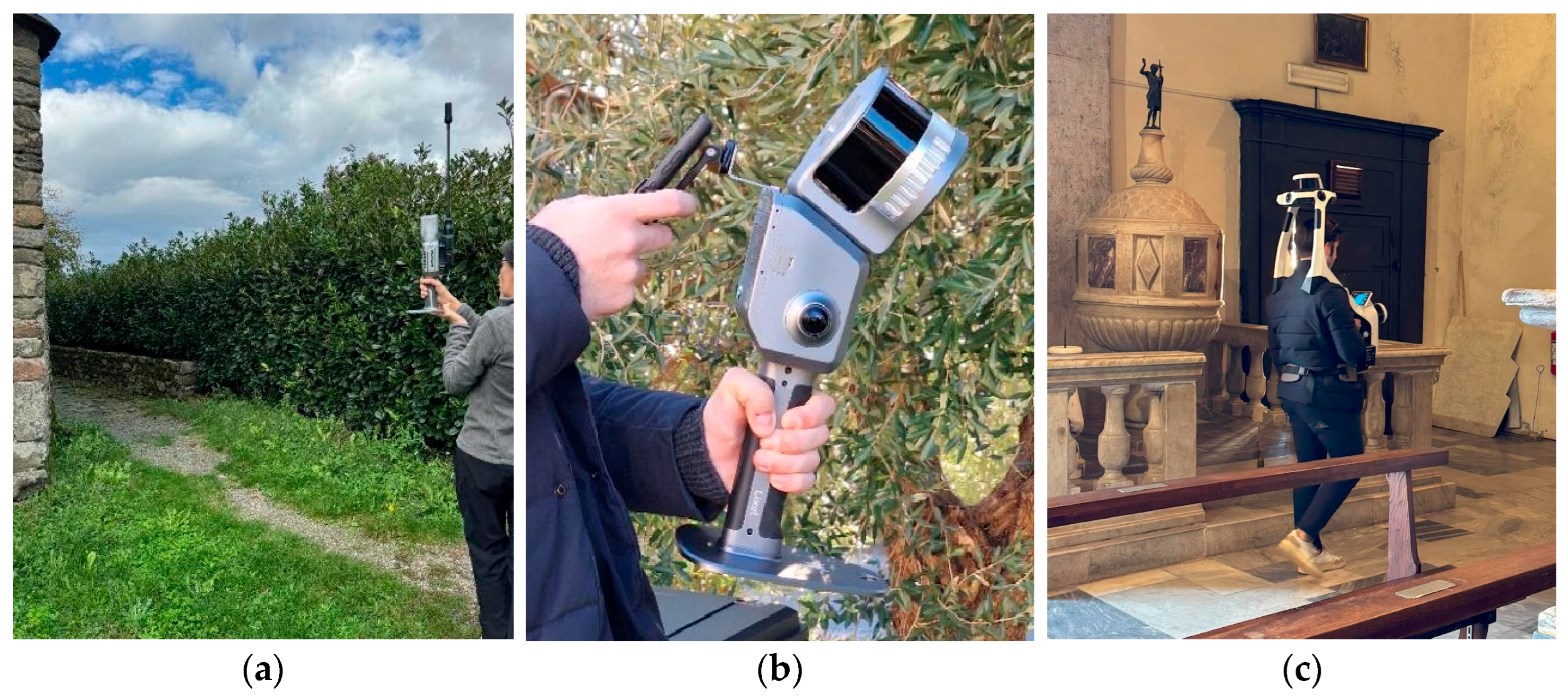

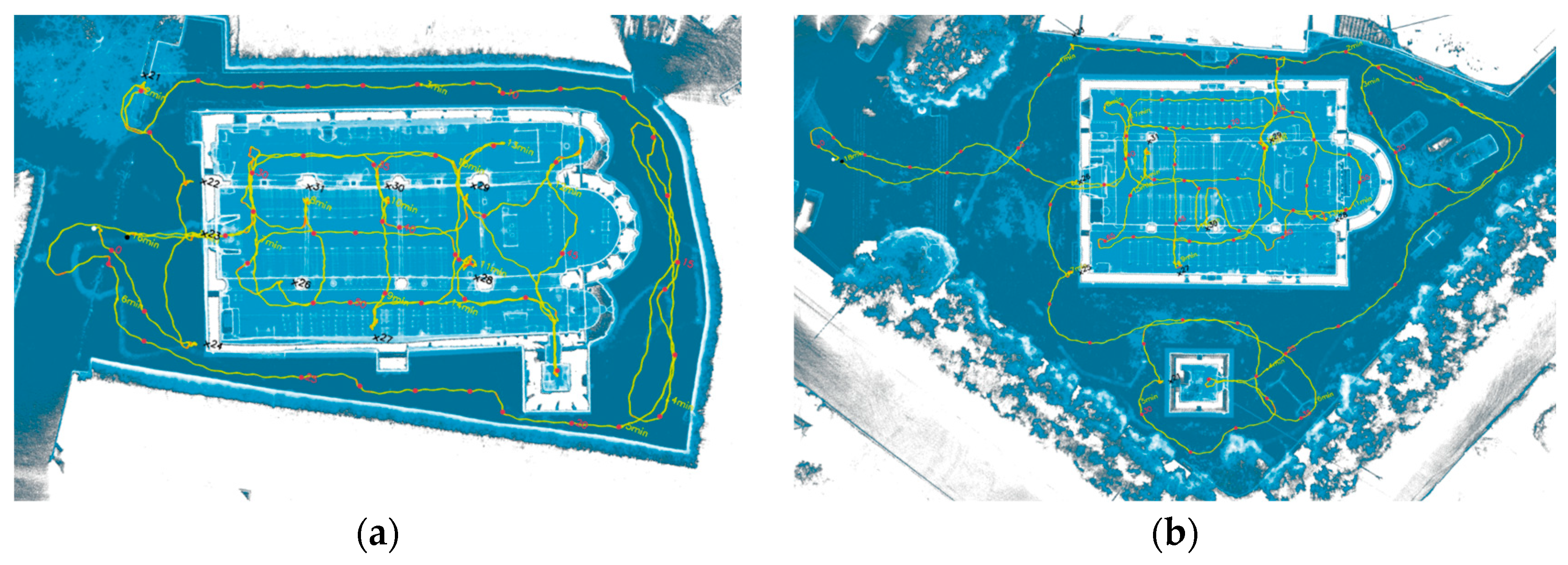

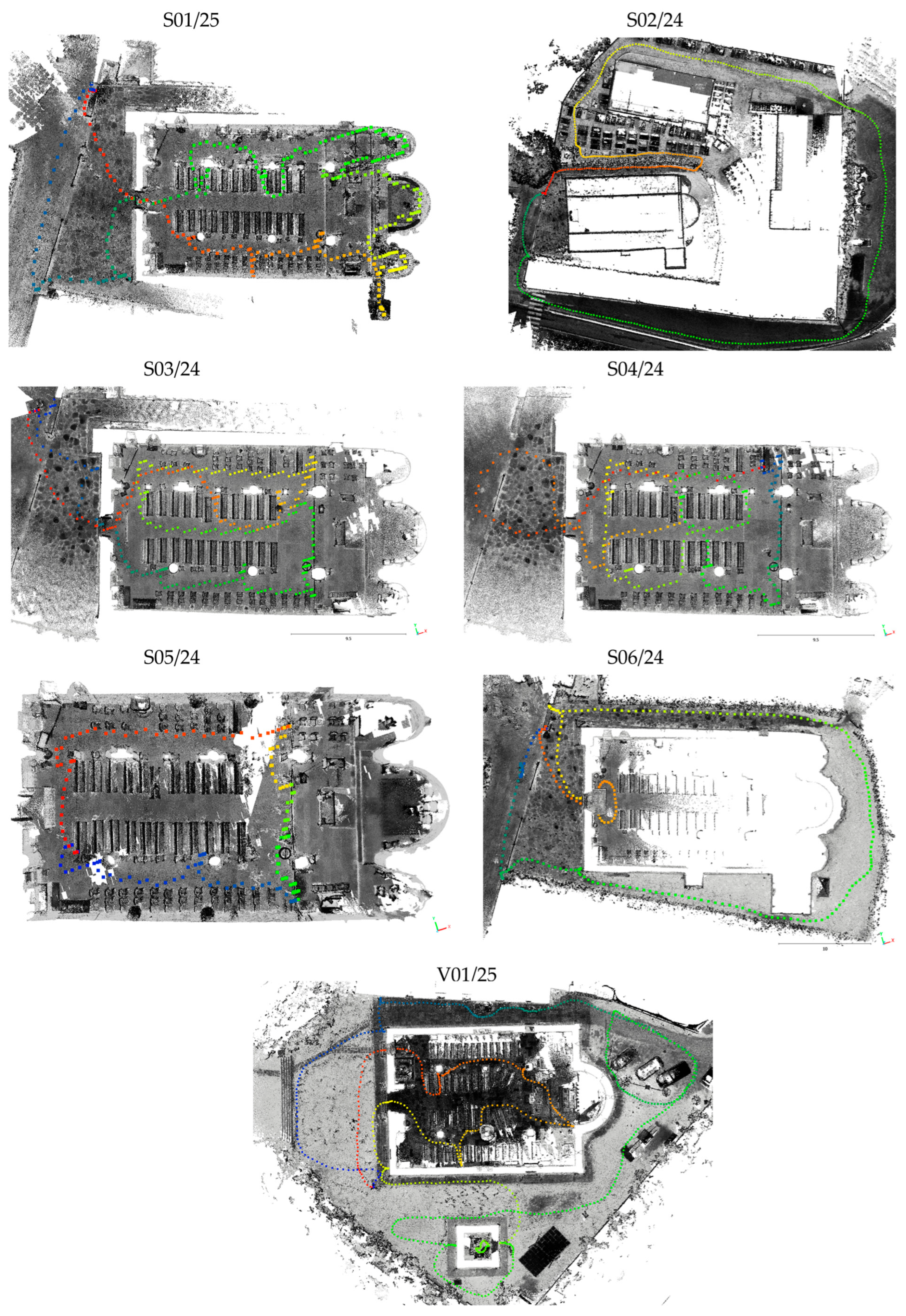

3.2. The Acquisition Campaigns

The Off-Line Processing

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Georeferencing Accuracy

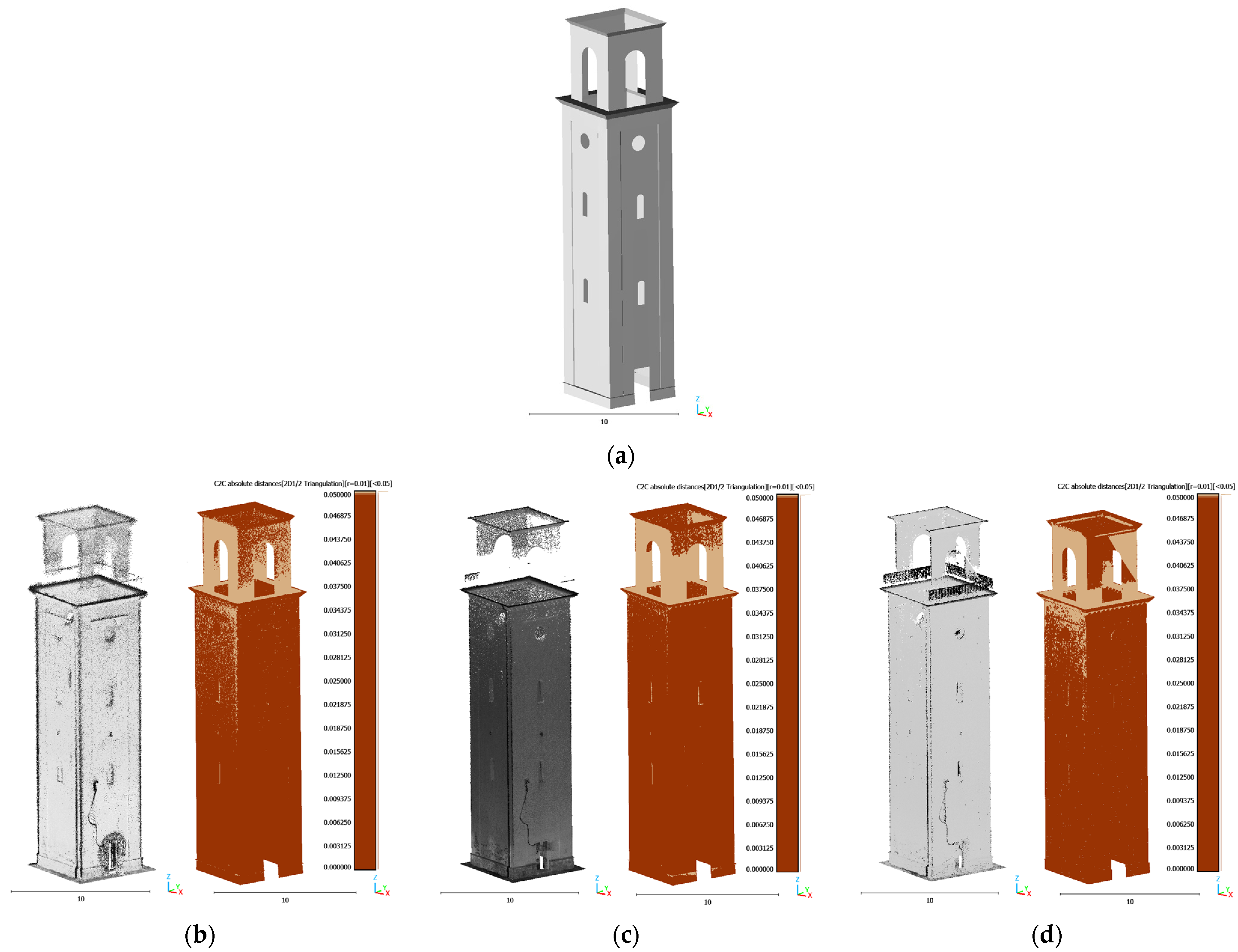

4.2. Analysis of 3D Models Accuracy

4.3. Analysis of 3D Model Density and Resolution

4.3.1. Point Cloud Density

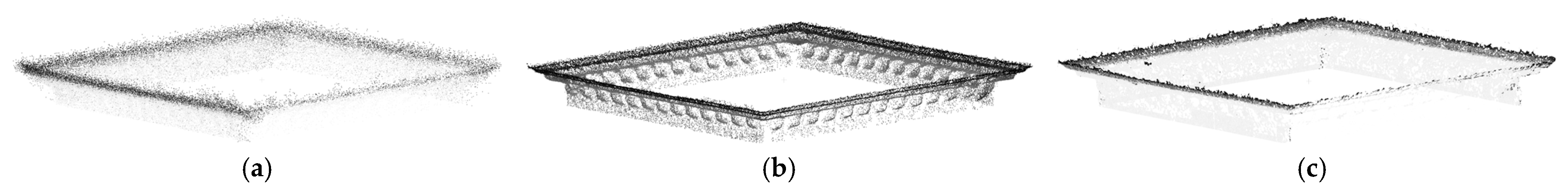

4.3.2. Point Cloud Resolution

4.4. Analysis of 3D Model Completeness

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calantropio, A.; Chiabrando, F.; Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A.; Teppati Losè, L. UAV strategies validation and remote sensing data for damage assessment in post-disaster scenarios. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 42, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, V.A. Tecniche Digitali per il Rilievo, la Modellazione Tridimensionale e la Rappresentazione Nel Campo dei Beni Culturali. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Malinverni, E.S.; Pierdicca, R.; Bozzi, C.A.; Bartolucci, D. Evaluating a slam-based mobile mapping system: A methodological comparison for 3D heritage scene real-time reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2018 Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (MetroArchaeo), Cassino, Italy, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Carballo, A.; Yang, H.; Takeda, K. Perception and sensing for autonomous vehicles under adverse weather conditions: A survey. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 196, 146–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How NeRFs and 3D Gaussian Splatting are Reshaping SLAM: A Survey. (n.d.). Available online: https://fabiotosi92.github.io/files/survey-slam.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A. Point clouds by SLAM-based mobile mapping systems: Accuracy and geometric content validation in multisensor survey and stand-alone acquisition. Appl. Geomat. 2018, 10, 317–339. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12518-018-0221-7 (accessed on 1 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, M.; Fink, E.; Anderson, J.; Fresa, A.; Antony Cassar, A.; Münster, S. 3D research challenges in cultural heritage VI: Digital twin versus memory twin. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Deng, F. LiDAR, IMU, and camera fusion for simultaneous localization and mapping: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeunne, C.; Vivet, D. A review of visual-LiDAR Fusion based simultaneous localization and mapping. Sensors 2020, 20, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarovoi, A.; Cho, Y.K. Review of simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) for construction robotics applications. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, G.; Qiao, Z.; et al. A Review of Research on SLAM Technology Based on the Fusion of LiDAR and Vision. Sensors 2025, 25, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toschi, I.; Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P.; Remondino, F.; Minto, S.; Orlandini, S.; Fuller, A. accuracy evaluation of a mobile mapping system with advanced statistical methods. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, XL-5/W4, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzino, G.P.C.; Grasso, N.; Matrone, F.; Osello, A.; Piras, M. Laser-visual-inertial odometry based solution for 3D heritage modeling: The Sanctuary of the Blessed Virgin of Trompone. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W15, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, G.; Visintini, D.; Bonora, V.; Parisi, E.I. Examination of indoor mobile mapping systems in a diversified internal/external test field. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbia, A.; Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A. Fostering Etruscan heritage with effective integration of UAV, TLS and SLAM-based methods. In Proceedings of the 2020 IMEKO TC-4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Toronto, Italy, 22–24 October 2020; Available online: https://www.imeko.org/publications/tc4-Archaeo-2020/IMEKO-TC4-MetroArchaeo2020-060.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- La Guardia, M.; Masiero, A.; Bonora, V.; Alessandrini, A. Open source deep learning solutions for the classification of MMS urban 3D data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, XLVIII-G-2025, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanduo, B.; Chiabrando, F.; Coluccia, L.; Auriemma, R. Underground heritage documentation: The case study of Grotta Zinzulusa in Castro (Lecce-Italy). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-M-2-2023, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlot, R.; Bosse, M.; Greenop, K.; Jarzab, Z.; Juckes, E.; Roberts, J. Efficiently capturing large, complex cultural heritage sites with a handheld mobile 3D laser mapping system. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, F.; Della Coletta, C.; Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A.; Spreafico, A. “Torino 1911” project: A contribution of a slam-based survey to extensive 3D heritage modeling. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, XLII-2, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharineiat, Z.; Tarsha Kurdi, F.; Henny, K.; Gray, H.; Jamieson, A.; Reeves, N. Assessment of NavVis VLX and BLK2GO SLAM scanner accuracy for outdoor and indoor surveying tasks. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, S.; Ferreyra, C.; Cotella, V.A.; di Filippo, A.; Amalfitano, S. A SLAM integrated approach for digital heritage documentation. In Culture and Computing. Interactive Cultural Heritage and Arts; Rauterberg, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtola, V.V.; Kaartinen, H.; Nüchter, A.; Kaijaluoto, R.; Kukko, A.; Litkey, P.; Hyyppä, J. Comparison of the selected state-of-the-art 3D indoor scanning and point cloud generation methods. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buill, F.; Núñez-Andrés, M.A.; Costa-Jover, A.; Moreno, D.; Puche, J.M.; Macias, J.M. Terrestrial laser scanner for the formal assessment of a Roman-medieval structure—the cloister of the cathedral of Tarragona (Spain). Geosciences 2020, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, D.; Rossi, G.; Pepe, M.; Leserri, M. Experiences of TLS, terrestrial and UAV photogrammetry in Cultural Heritage environment for restoration and maintenance purposes of Royal Racconigi castle, Italy. In Proceedings of the 2022 IMEKO TC4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Calabria, Italy, 19–21 October 2022; IMEKO: Budapest, Hungary, 2023; pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, G.; Bonora, V. Towers in San Gimignano: Metric survey approach. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2017, 31, 04017105. Available online: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE%29CF.1943-5509.0001085 (accessed on 1 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hamzić, A.; Kulo, N.; Đidelija, M.; Topoljak, J.; Mulahusić, A.; Tuno, N.; Ademović, N. Assessment of Minaret Inclination and Structural Capacity Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning and 3D Numerical Modeling: A Case Study of the Bjelave Mosque. Geomatics 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulahusić, A.; Tuno, N.; Topoljak, J.; Gačanović, F. Integration of UAV and terrestrial photogrammetry for cultural and historical heritage recording and 3D modelling: A case study of the ‘Sebilj’ Fountain in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. In New Technologies, Development and Application V. NT 2022; Karabegović, I., Kovačević, A., Mandžuka, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furini, A.; Bolognesi, M. Accuracy of cultural heritage 3D models by RPAS and terrestrial photogrammetry. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, XL-5, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawabkeh, Y.; Baik, A.; Miky, Y. Integration of laser scanner and photogrammetry for heritage BIM enhancement. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, J.L.; Gómez-López, J.M.; Mozas-Calvache, A.T.; Delgado- García, J. Analysis of the photogrammetric use of 360-degree cameras in complex heritage-related scenes: Case of the Necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa (Aswan Egypt). Sensors 2024, 24, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đurić, I.; Obradović, R.; Vasiljević, I.; Ralević, N.; Stojaković, V. Twodimensional shape analysis of complex geometry based on photogrammetric models of iconostases. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma, J.L.; Navarro, S.; Cabrelles, M.; Villaverde, V. Terrestrial laser scanning and close range photogrammetry for 3D archaeological documentation: The Upper Palaeolithic Cave of Parpalló as a case study. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, F.; Chiappini, S.; Gorreja, A.; Balestra, M.; Pierdicca, R. Mobile 3D scan LiDAR: A literature review. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 2387–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillia, E.; Sammartano, G.; Tocci, C. Spanò Modellare la conoscenza della vulnerabilità sismica delle chiese in muratura storica con tecnologie 3D speditive. In Proceedings of the Conferenza ASITA 2021, Genoa, Italy, 1–23 July 2021; pp. 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartano, G.; Avena, M.; Fillia, E.; Spanò, A. Integrated HBIM-GIS Models for Multi-Scale Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Historical Buildings. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, P.; Ciancio, V.; Nastri, E. Seismic performance assessment of the church of SS. Annunziata in Paestum through finite element analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 162, 108388. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1350630724004345 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tanduo, B.; Teppati Losè, L.; Chiabrando, F. Documentation of complex environments in cultural heritage sites. A slam-based survey in the Castello del Valentino basement. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-1/W1-2023, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, A.Y.; Gamze Hamal, S.N.; Ulvi, A.; Yakar, M. Comparative analysis of mobile laser scanning and terrestrial laser scanning for the indoor mapping. Build. Res. Inf. 2023, 52, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.; Alfio, V.S.; Costantino, D.; Herban, S. Rapid and accurate production of 3D point cloud via latest-generation sensors in the field of cultural heritage: A Comparison between SLAM and Spherical Videogrammetry. Heritage 2022, 5, 1910–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, M.; Bonora, V.; Galano, L.; Pellis, E.; Tucci, G.; Vignoli, A. An Integrated geometric and material survey for the conservation of heritage masonry structures. Heritage 2021, 4, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Ke, K. Fuse replacement implementation by shaking table tests on hybrid moment-resisting frame. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, M.; Lubowiecka, I.; Szymczak, C. Finite element modelling of a historic church structure in the context of a masonry damage analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 107, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DPCM 2011 Direttiva del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri per la Valutazione e Riduzione del Rischio Sismico del Patrimonio Culturale con Riferimento alle NTC 2008 (Directive of the President of the Council of Ministers for the Evaluation and Reduction of Seismic Risk of Cultural Heritage with Reference to the 2008 NTCs). G. U. n. 47 del 26.02.2011. 2011. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2011/02/26/11A02374/sg (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Lourenço, P.B.; Oliveira, D.V.; Leite, J.C.; Ingham, J.M.; Modena, C.; Da Porto, F. Simplified indexes for the seismic assessment of masonry buildings: International database and validation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 34, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapietro, M. Analisi Della Risposta e Sicurezza Sismica del Campanile di San Lorenzo a Minucciano (Analysis of the Response and Seismic Safety of the Bell Tower of San Lorenzo in Minucciano). Barchelor’s Thesis in Architecture, Università degli studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- BeWeb (Beni Ecclesiastici in Web—Beni Ecclesiastici in Web) Online Database of the Italian Catholic Church. Available online: https://beweb.chiesacattolica.it/?l=it_IT (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J.J. Past, present, and future of simultaneous localization and mapping: Toward the robust-perception age. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1309–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Pagliaricci, G.; Bonora, V.; Tucci, G. A comparison between terrestrial laser scanning and hand-held mobile mapping for the documentation of built heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-2/W4-2024, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CloudCompare, 3D Point Cloud and Mesh Processing Software, Open Source Project. Homepage. Available online: https://cloudcompare.org/index.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Diaz, V.; Van Oosterom, P.; Meijers, M.; Verbree, E.; Ahmed, N.; Van Lankveld, T. Comparison of Cloud-to-Cloud Distance Calculation Methods—Is the Most Complex Always the Most Suitable? In Recent Advances in 3D Geoinformation Science; Kolbe, T.H., Donaubauer, A., Beil, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lague, D.; Brodu, N.; Leroux, J. Accurate 3D comparison of complex topography with terrestrial laser scanner: Application to the Rangitikei canyon (N-Z). ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 82, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, A.Y.; Ulvi, A. Comparison of the Wearable Mobile Laser Scanner (WMLS) with Other Point Cloud Data Collection Methods in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Diokaisareia. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2022, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, C.; Patrucco, G.; Perri, S.; Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A. A new indoor lidar-based mms challenging complex architectural environments. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, XLVI-M-1-2021, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Dong, X.; He, Q. Calculating the optimal point cloud density for airborne lidar landslide investigation: An adaptive approach. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, C.; Bryan, P.; McDougall, L.; Reuter, T.; Payne, E.; Moitinho, V.; Rodgers, T.; Honkova, J.; O’Connor, L.; Blockley, C.; et al. 3D Laser Scanning for Heritage: Advice and Guidance on the Use of Laser Scanning in Archaeology and Architecture, 3rd ed.; English Heritage; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-84802-521-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartano, G.; Patrucco, G.; Avena, M.; Bonfanti, C.; Spanò, A. Enhancing terrestrial point clouds using upsampling strategy: First observation and test on faro flash technology. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-2/W4-2024, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X. A robust assessment method of point cloud quality for enhancing 3D robotic scanning. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Haala, N. Guided by model quality: UAV path planning for complete and precise 3D reconstruction of complex buildings. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 127, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fan, G.; Li, J. Improving completeness and accuracy of 3D point clouds by using deep learning for applications of digital twins to civil structures. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 58, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R.; Degener, P.; Klein, R. Completion and reconstruction with primitive shapes. Comput. Graph. Forum 2009, 28, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achlioptas, P.; Diamanti, O.; Mitliagkas, I.; Guibas, L. Learning representations and generative models for 3d point clouds. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; 2018; PMLR, pp. 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sipiran, I.; Mendoza, A.; Apaza, A.; Lopez, C. Data-driven restoration of digital archaeological pottery with point cloud analysis. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2149–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, M.; Patias, P. The complexity and quality in 3D digitisation of the past: Challenges and risks. In 3D Research Challenges in Cultural Heritage III; Ioannides, M., Patias, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurek, P.; Kasymov, A.; Mazur, M.; Janik, D.; Tadeja, S.K.; Tabor, J.; Trzciński, T. Hyper Pocket: Generative point cloud completion. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 6848–6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| X70GO | VLX 3 | Lixel L2 Pro | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device configuration | Handheld | Wearable | Handheld |

| N° LiDAR | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Points per second | 200,000 pts/s | 2 × 1,280,000 pts/s | 640,000 pts/s |

| N° of cameras | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Visual SLAM | yes | No | yes |

| Camera resolution | 12 MP | 20 MP | 48 MP |

| RTK GNSS | Integrable | No | Integrated |

| Declared accuracy | 6 mm | 5 mm | 5 mm |

| Processing software | GOpost | NavVis IVION (cloud-based) | LixelStudio |

| GOpost | NavVis IVION | LixelStudio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Stonex | NavVis | XGRIDS |

| Post-elaboration | Desktop (Windows) | Cloud | Desktop (Windows) |

| Georeferencing | RTK–GCP | GCP | RTK–GCP |

| Colouring | yes | yes | yes |

| Densification | Yes, up to version 66; optional for newer versions | Down- or over-sampling option | Optional |

| Filtering | Persons removal | Blurring of faces, bodies and plates | Moving objects removal |

| X70GO | VLX 3 | Lixel L2 Pro | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paths | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Acquisition time | 6–12 min | 18–25 min | 20 min |

| Processing time | 1–2 h | 4 h | 2 h |

| Instrument | Path | Georeferencing | # Target | Trajectory | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorano Church | VLX 3 | S01/25 | Targets | 10 | 500 m |

| X70GO | S03/24 | Targets | 9 | 140 m | |

| 4 | |||||

| S04/24 | Targets | 6 | 140 m | ||

| S05/24 | Targets | 3 | 70 m | ||

| S01/25 | Targets | 10 | 180 m | ||

| 5 | |||||

| RTK GNSS | - | 180 m | |||

| S02/24 | RTK GNSS | - | 300 m | ||

| S06/24 | RTK GNSS | - | 150 m | ||

| Vallecchia Church | VLX 3 | V01/25 | Targets | 9 | 450 m |

| X70GO | V01/25 | Targets | 10 | 340 m | |

| 4 | |||||

| RTK GNSS | - | ||||

| Lixel L2 Pro | V01/25 | Targets | 9 | 450 m |

| Path | Target | Planimetric Residuals (XY, Absolute Values) [m] | Vertical Residuals (Z, Signed Values) [m] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | RMSE | 68th %tile | 95th %tile | Mean | σ | RMSE | ||||

| Sorano Church | VLX 3 S01/25 | GCPs | 10 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| X70GO S03/24 | GCPs | 9 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| GCPs | 4 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.002 | ||

| CPs | 5 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.015 | −0.004 | 0.006 | 0.007 | ||

| X70GO S04/24 | GCPs | 6 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| X70GO S05/24 | GCPs | 3 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| X70GO S01/25 | GCPs | 10 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| GCPs | 5 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.026 | 0.035 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.004 | ||

| CPs | 5 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.036 | −0.003 | 0.008 | 0.009 | ||

| Vallecchia Church | VLX 3 | GCPs | 9 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| X70GO V01/25 | GCPs | 10 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| CPs | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| GCPs | 4 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| CPs | 6 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.031 | −0.003 | 0.015 | 0.016 | ||

| Path | Target (GCPs/CPs) or GNSS | Planimetric Residuals (XY, Absolute Values) [m] | Vertical residuals (Z, Signed Values) [m] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | RMSE | 68th %tile | 95th %tile | Mean | σ | RMSE | |||

| Sorano Church | X70GO S02/24 | GNSS | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| X70GO S03/24 | 9/0 | 0.019 | 0.010 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.040 | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.023 | |

| 4/5 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.019 | 0.051 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.024 | ||

| X70GO S04/24 | 6/0 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.039 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.024 | |

| X70GO S05/24 | 3/0 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.041 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.020 | |

| X70GO S06/24 | GNSS | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| X70GO S01/25 | 10/0 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.026 | 0.020 | 0.047 | 0.008 | 0.020 | 0.022 | |

| 5/5 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.046 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.024 | ||

| GNSS | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.033 | 0.037 | 0.058 | −0.003 | 0.020 | 0.014 | ||

| VLX 3 2025 | 10/0 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.019 | 0.052 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.025 | |

| Vallecchia church | X70GO V01/25 | 10/0 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| 4/6 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| GNSS | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.020 | 0.018 | 0.036 | −0.003 | 0.015 | 0.015 | ||

| VLX 3 2025 | 9/0 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Lixel L2 Pro 2025 | 9/0 | 0.074 | 0.080 | 0.075 | 0.085 | 0.088 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| Dataset | Missing Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| X70GO | 4,487,135 | 926,905 (12%) |

| VLX 3 | 6,951,798 | 1,048,059 (13%) |

| Lixel L2 Pro | 10,027,081 | 982,476 (12%) |

| Dataset | Missing Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| X70GO | 12,932,352 | 4,370,866 (55%) |

| VLX 3 | 22,099,022 | 4,011,038 (50%) |

| Lixel L2 Pro | 19,294,359 | 4,332,166 (54%) |

| Dataset | Missing Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| X70GO | 145,903 | 75,370 (25%) |

| VLX 3 | 225,472 | 73,187 (24%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bonora, V.; Colapietro, M. Performance Assessment of Portable SLAM-Based Systems for 3D Documentation of Historic Built Heritage. Sensors 2026, 26, 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020657

Bonora V, Colapietro M. Performance Assessment of Portable SLAM-Based Systems for 3D Documentation of Historic Built Heritage. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):657. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020657

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonora, Valentina, and Martina Colapietro. 2026. "Performance Assessment of Portable SLAM-Based Systems for 3D Documentation of Historic Built Heritage" Sensors 26, no. 2: 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020657

APA StyleBonora, V., & Colapietro, M. (2026). Performance Assessment of Portable SLAM-Based Systems for 3D Documentation of Historic Built Heritage. Sensors, 26(2), 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020657