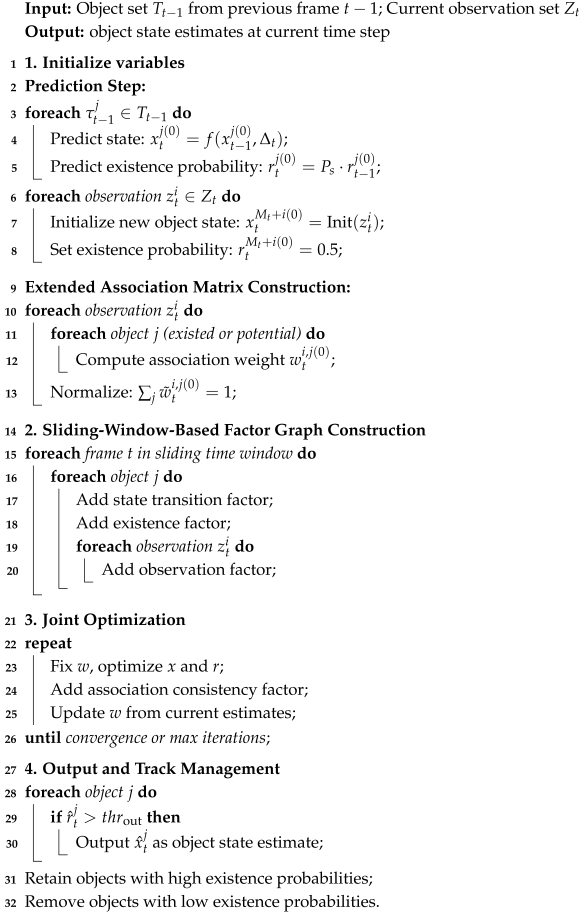

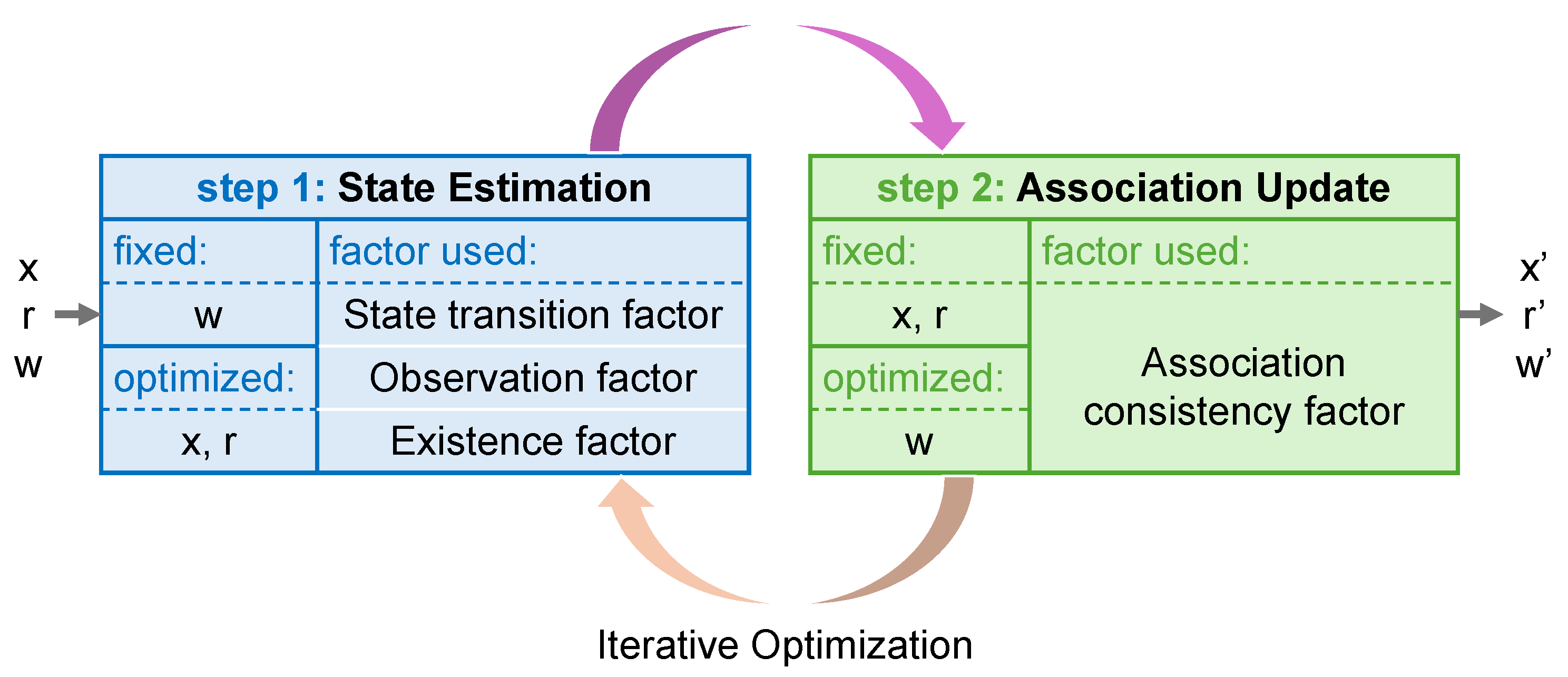

This section presents the proposed 3D MOT framework named FGO-PMB, which integrates RFS and FGO. The overall workflow is illustrated in

Figure 1. The process operates continuously over time steps. At each current frame

t, the system takes two inputs: the set of detections

from the detector and the estimated object states

from the previous frame. First, a Poisson Multi-Bernoulli (PMB) model is employed to predict the object states probabilistically. This involves computing the Poisson point process (PPP) intensity

for potential birth objects and the Multi-Bernoulli (MB) spatial density

for surviving objects. Based on these distributions, an extended association matrix is constructed to generate three key variables: the refined object states

X, the existence probabilities

R, and the association weights

W. Subsequently, these variables are collected within a sliding time window. A global optimization is performed using a factor graph to jointly solve for the optimal variables by considering multiple constraints, including state transition, observation, association consistency, and existence factors. Finally, the optimal states for the current frame are extracted through a matching and pruning process to produce the final tracking output.

3.1. Modeling

The proposed method uses the TBD paradigm to track multiple dynamic objects in a 3D scene online. Assume that at time t, there is a set of targets , where denotes the number of targets at time t. The state vector of each target is defined as . Here, represents the 3D center position of the object, denotes the height, width, and length of the 3D bounding box, is the velocity magnitude in the plane, denotes the heading angle, is the heading angular velocity or turning rate, represents the object class, and is the unique object identifier. Meanwhile, the detector provides a set of observations , where each observation represents the 3D center position, size, orientation, class, and detection confidence score of each detection box, and denotes the number of detections at time t. Notably, any 3D detector that produces standard 3D detections can be utilized with our proposed tracker.

3.2. Variable Initialization

Before performing FGO, it is necessary to provide reasonable initial estimates for all variables to be optimized, including object states, existence probabilities, and association weights. Good initialization is essential for efficiently solving nonlinear optimization problems. It improves convergence speed and stability, while also helping the optimizer avoid local optima in complex scenarios. This subsection presents our initialization strategy, which is derived from the principles of RFS theory. By modeling the survival of existing objects and the emergence of new ones within a unified probabilistic framework, it enables consistent and principled initialization for subsequent graph optimization.

Specifically, for each object

j that may survive from time

to time

t, the prediction is derived from the multi-Bernoulli representation. Assuming that it survives independently with a constant survival probability

, its existence probability

at time

t is predicted as follows:

The corresponding state vector

is predicted according to a state transition function that characterizes the temporal evolution of the object based on its kinematic properties. The general state transition equation is formulated as:

In this work, to accurately capture the maneuvering characteristics of traffic participants, which often involve coordinated turns, we implement the function

using the nonlinear Constant Turn Rate and Velocity (CTRV) model [

37]. Unlike simple linear models such as Constant Velocity (CV), the CTRV model explicitly incorporates the heading angular velocity, enabling a more accurate representation of the curvilinear motion of maneuvering targets. The specific formulations of the CTRV model, presented in Equations (

3)–(

7), are derived by integrating the kinematic differential equations of the object state over the time interval

, under the assumption that both the velocity magnitude

and the heading angular velocity

remain constant during this period. Specifically, the state transition function

is formulated as:

where

donates the 2D center position in the

plane,

is the velocity magnitude,

is the heading angle,

is the heading angular velocity, and

represents the time interval.

To accommodate the potential new targets within a unified framework, the method models them using an observation-driven Poisson Point Process (PPP). Specifically, at time

t, a potential new target hypothesis is generated for each of the

observations

in the current frame. These potential new target hypotheses are indexed consecutively after the

existing objects, forming a unified and expanded set of object hypotheses. The initial state

of each potential new target hypothesis is directly initialized from its corresponding observation

:

where

denotes the number of surviving objects predicted at the current time step

t, and the initialization function

assigns the detected position and the heading angle directly to the position and angle component of the state, while the velocity and the heading angular velocity are initially set to zero. The existence probability

is initialized to an intermediate value reflecting maximum uncertainty (e.g., 0.5).

After initializing the survival objects and potential new targets, prior information on data association is incorporated into the FGO. Unlike traditional methods that treat association as an independent decision step, our method uses PMB to estimate the association probabilities of each observation

with all potential target sources and incorporates the probabilities into the optimizer as a soft prior. Specifically, for the i-

th observation and the j-

th object hypothesis, the initial association weight

is given by:

where

represents the Gaussian likelihood function,

R is the observation noise covariance,

is the detection confidence score, and

is the Poisson intensity representing the likelihood of new object’s occurrence. The proposed equation defines three cases: (1) For surviving objects, the weight is given by the product of their existence probability

, detection probability

, and the Gaussian observation likelihood function

, where

H is the observation matrix and

R is the observation noise covariance; (2) For potential new objects, the weight is defined by the product of the observation confidence

and the Poisson intensity

; (3) For all other cases, the association weight is set to zero. This covers associations rejected by the gating mechanism as well as invalid pairings involving potential new objects. Specifically, each potential new object is uniquely generated from a single observation; thus, the

i-th observation corresponds exclusively to the new object hypothesis indexed by

. Any association with

is invalid, as it implies associating an observation with a new object hypothesis generated by another measurement.

Then, the association weights of each observation are normalized as:

which ensures that for any observation

i, the total probability that it originates from all possible sources sums to 1, i.e.,

. The normalized association weights are subsequently used as soft priors in the FGO.

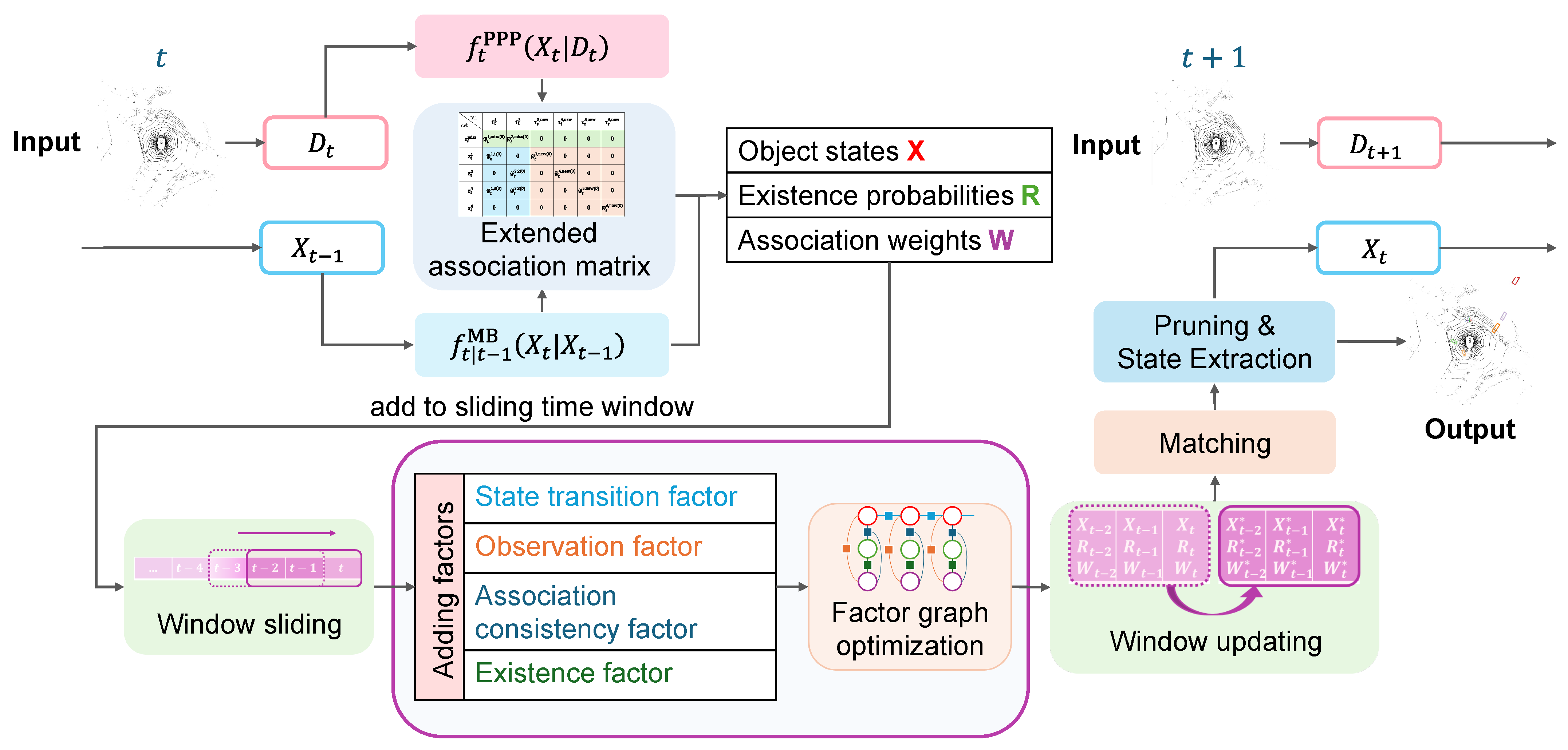

Figure 2 illustrates the final structure of the extended association matrix, whose elements are populated according to Equation (

10). Specifically, the rows of this matrix not only represent all actual observations

at the current time step, but also include an additional row

(the first row, shown in

green) corresponding to the missed-detection hypothesis, which accounts for undetected trajectories. The columns correspond to existing targets (

blue) and new target candidates (

red), with weights between unrelated pairs set to 0. This matrix thus provides a unified representation of the initial likelihood of association between observations and all potential targets.

3.4. Post Processing

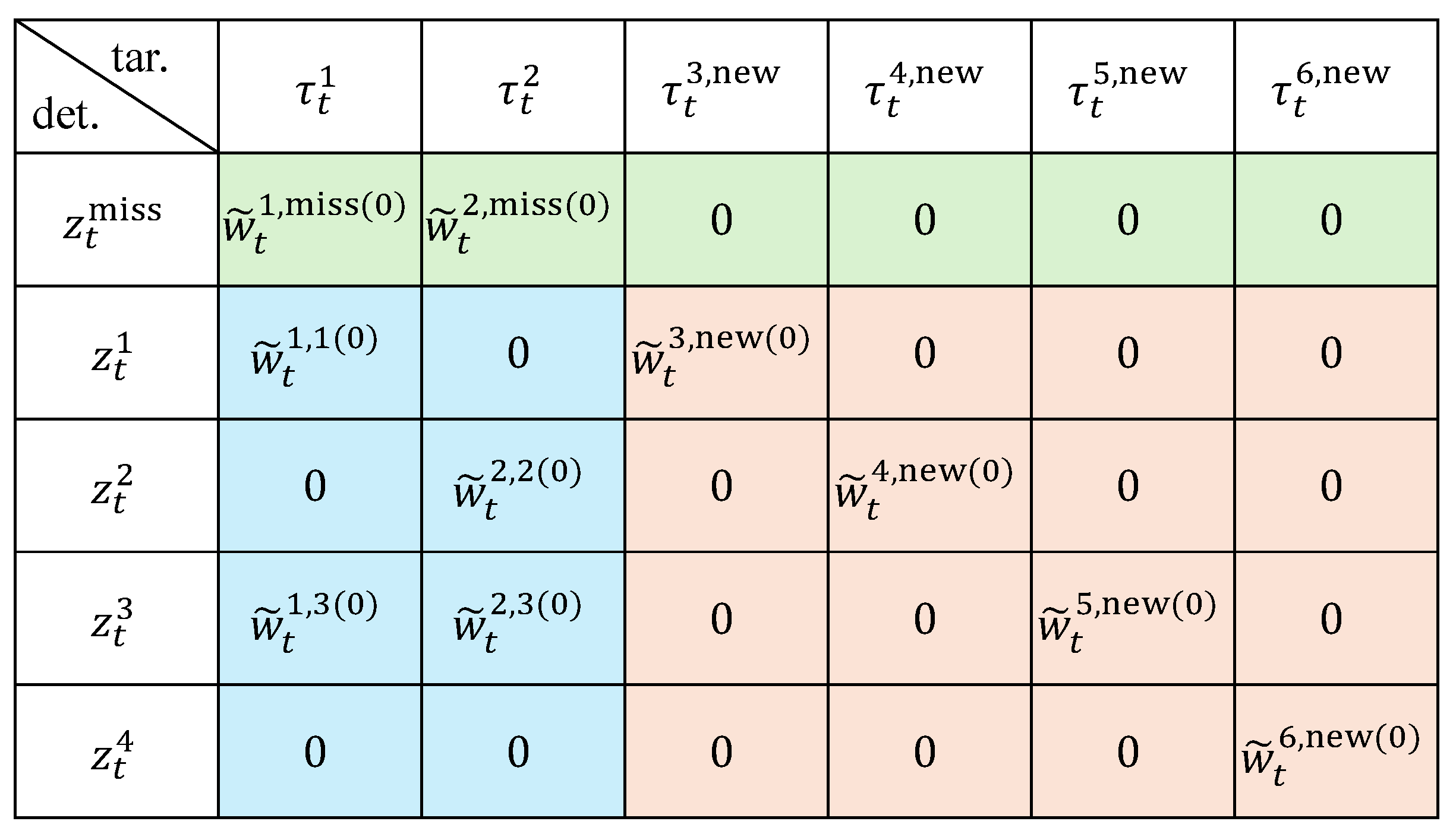

Rather than optimizing over an ever-growing trajectory history, the proposed framework adopts a sliding time window mechanism with a fixed length

L, which controls computational complexity while preserving tracking quality. All joint optimizations are restricted to the sliding time window. Consequently, at any time

t, the global objective function is expressed as the sum of the costs over all frames within the window, defined as follows:

After reaching convergence or the maximum number of iterations within the current window , the system proceeds with subsequent post-processing steps, including output, trajectory management, and window update.

3.4.1. Data Association

After FGO yields continuous association weight matrices over the sliding window, the matrix at the current time t is extracted and converted to discrete associations using the Hungarian or greedy algorithm.

3.4.2. Object State Output

Once the optimal matching solution at time t is determined, the final tracking output is obtained by retaining only the trajectories successfully associated with observations. Specifically, targets with an existence probability greater than the output threshold are considered high-confidence, and their estimated states are reported as the outputs of the current frame.

3.4.3. Object Lifecycle Management

The object lifecycle management mechanism is entirely based on the existence probability in RFS theory, rather than heuristic counters, enabling more robust handling of object birth and death.

The specific management rules are as follows: for each object within the sliding time window, including potential newly born targets, survivability is assessed based on its existence probability . For a newly generated object hypothesis from an observation, if exceeds the output threshold , it is recognized as a new trajectory. For any object j, if falls below the deletion threshold , the object is regarded as lost; if the loss persists for more than moments, the object is permanently removed and will no longer participate in subsequent optimization.

3.4.4. Window Update

After completing the optimization and lifecycle management for the current window , the window advances by one time step. Specifically, all variables and factors at the earliest time within the window are removed, the surviving targets at time t are predicted to obtain the prior at , the new observations are introduced, and potential new targets are initialized. At this point, the factor graph covering the updated window is constructed and ready for the next round of optimization.

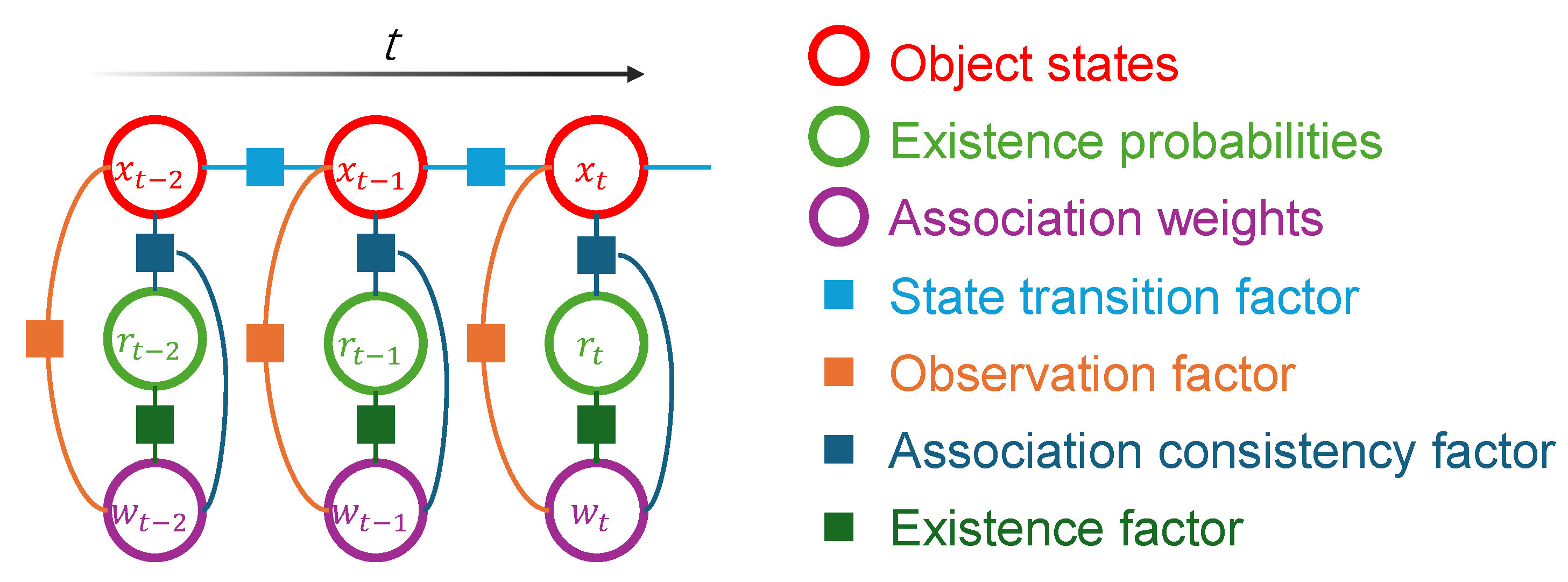

Algorithm 1 summarizes the proposed 3D MOT framework and provides the pseudo-code of its online tracking procedure.

| Algorithm 1: 3D Multi-Object Tracking based on PMB and FGO |

![Sensors 26 00591 i001 Sensors 26 00591 i001]() |