Sub-Diffraction Photoacoustic Microscopy Enabled by a Novel Phase-Shifted Excitation Strategy: A Numerical Study

Highlights

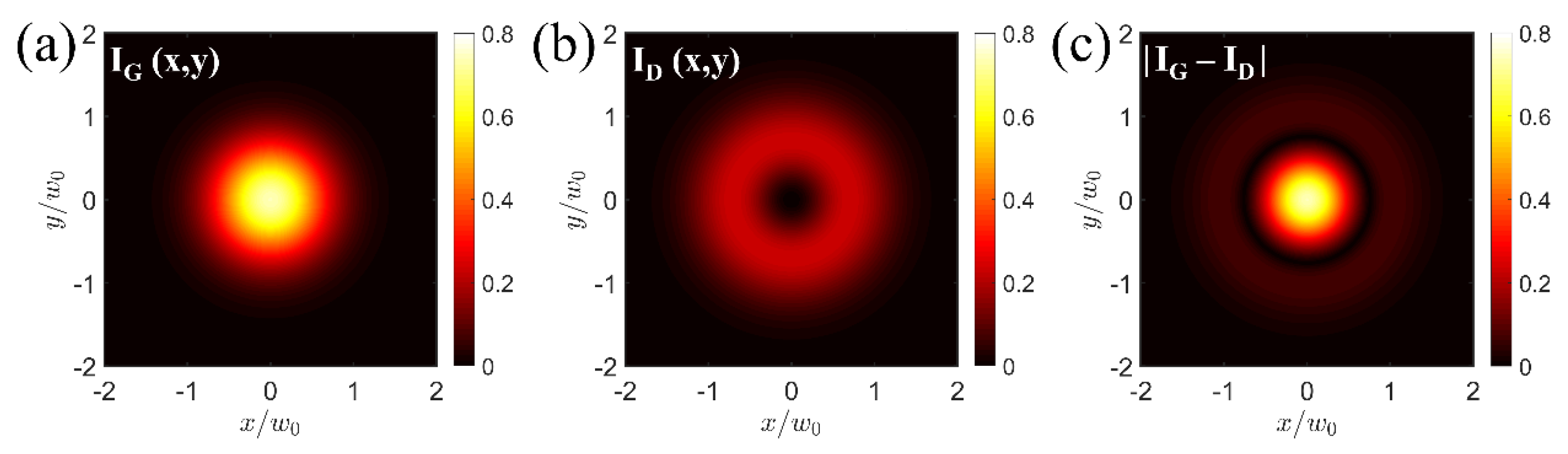

- The proposed phase-shifted Gaussian and donut beam excitation scheme may confine the effective photoacoustic excitation region beyond the conventional optical diffraction limit.

- Numerical simulations show a ~1.42× lateral resolution improvement at an optimal power ratio of 1.16 between the two beams.

- It is shown that sub-diffraction photoacoustic microscopy can be achieved using frequency-domain excitation with continuous-wave lasers.

- The method can pave the way for cost-efficient, high-resolution biomedical photoacoustic imaging without nonlinear contrast mechanisms.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Methods

2.1. Photoacoustic Equation Model

2.2. Optical Excitation Scheme

2.3. Intensity Distributions

2.4. Effective Photoacoustic Excitation Region

3. Results

3.1. Simulation of Lateral Resolution Enhancement

3.2. Temporal Evolution of the Excitation Process

3.3. Influence of the Optical Power Ratio

3.4. Phase-Shifted Photoacoustic Imaging Simulation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeon, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Baik, J.W.; Kim, C. Review on practical photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics 2019, 15, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic microscopy. Laser Photonics Rev. 2013, 7, 758–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielli, A.; Maslov, K.; Garcia-Uribe, A.; Winkler, A.M.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Dorn, G.W.; Wang, L.V. Label-free photoacoustic nanoscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 086006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xing, D. Super-resolution photoacoustic imaging based on saturation difference of transient absorption (TASD-PAM). Opt. Lasers Eng. 2022, 150, 106877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Xu, Z.; Ren, Y.; Song, L.; Liu, C. Nonlinear mechanisms in photoacoustics—Powerful tools in photoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 2021, 22, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tang, Y.; Yao, J. Advances in super-resolution photoacoustic imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2018, 8, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Liu, L. Resolution Enhancement Strategies in Photoacoustic Microscopy: A Comprehensive Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalitsounakis, P.; Zacharakis, G.; Tserevelakis, G.J. Towards affordable biomedical imaging: Recent advances in low-cost, high-resolution optoacoustic microscopy. J. Microsc. 2025, 298, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, M.; Stylogiannis, A.; Prade, L.; Glasl, S.; Ntziachristos, V. Overdriven laser diode optoacoustic microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylogiannis, A.; Prade, L.; Buehler, A.; Aguirre, J.; Sergiadis, G.; Ntziachristos, V. Continuous wave laser diodes enable fast optoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 2018, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellnberger, S.; Soliman, D.; Tserevelakis, G.J.; Seeger, M.; Yang, H.; Karlas, A.; Prade, L.; Omar, M. Optoacoustic microscopy at multiple discrete frequencies. Light Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, G.; Buchegger, B.; Jacak, J.; Klar, T.A.; Berer, T. Frequency domain photoacoustic and fluorescence microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 7, 2692–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tserevelakis, G.J.; Tekonaki, E.; Kalogeridi, M.; Liaskas, I.; Pavlopoulos, A.; Zacharakis, G. Hybrid fluorescence and frequency-domain photoacoustic microscopy for imaging development of Parhyale hawaiensis embryos. Photonics 2023, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, P.; Kellnberger, S.; Ntziachristos, V. Frequency domain optoacoustic tomography using amplitude and phase. Photoacoustics 2014, 2, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, U.; Singh, N.; Singh, K.; Hagone, V.N.; Singh, J.; Anand, A.S.; Cox, B.T.; Saha, R.K. Efficient implementations of a Born series for computing photoacoustic field from a collection of erythrocytes. Photoacoustics 2025, 43, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.V.; Wu, H. Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verdeyen, J.T. Laser Electronics, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Siegman, A.E. Lasers; University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hell, S.W.; Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: Stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 1994, 19, 780–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Ata, S.; Yamada, T.; Okazaki, T. Nondestructive real-space imaging of energy dissipation distributions in randomly networked conductive nanomaterials. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.-K.; Maslov, K.; Shung, K.K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L.V. In vivo label-free photoacoustic microscopy of cell nuclei by excitation of DNA and RNA. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 4139–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tserevelakis, G.J.; Velentza, S.; Liaskas, I.; Archontidis, T.; Pavlopoulos, A.; Zacharakis, G. Imaging Parhyale hawaiensis embryogenesis with frequency-domain photoacoustic microscopy: A novel tool in developmental biology. J. Biophotonics 2022, 15, e202200202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslov, K.; Zhang, H.F.; Hu, S.; Wang, L.V. Optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy for in vivo imaging of single capillaries. Opt. Lett. 2008, 33, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Yan, M.; Zheng, W.; Song, L. Longitudinal label-free optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy of tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2015, 5, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Ando, T.; Inoue, T.; Ohtake, Y.; Fukuchi, N.; Hara, T. Generation of high-quality higher-order Laguerre–Gaussian beams using liquid-crystal-on-silicon spatial light modulators. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2008, 25, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; DiSpirito, A.; Jang, H.; McGarraugh, C.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Shi, L.; Yao, J. Virtual-point-based deconvolution for optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. J. Biophotonics 2024, 17, e202400078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, D.; Ha, M.; Kim, D.; Kim, C. A comprehensive review of high-performance photoacoustic microscopy systems. Photoacoustics 2025, 44, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Menozzi, L.; Cho, S.W.; Yao, J. High speed innovations in photoacoustic microscopy. npj Imaging 2024, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, J.; Xia, J.; Yao, J.; Shi, J.; Li, C. Photoacoustic imaging with limited sampling: A review of machine learning approaches. Biomed. Opt. Express 2023, 14, 1777–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lan, H.; Gao, F.; Gao, F. Review of deep learning for photoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 2021, 21, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, W.; Kou, T.; Li, C.; You, M.; Shen, J. Unsupervised learning for enhanced computed photoacoustic microscopy. Electronics 2024, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tserevelakis, G.J. Sub-Diffraction Photoacoustic Microscopy Enabled by a Novel Phase-Shifted Excitation Strategy: A Numerical Study. Sensors 2026, 26, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020498

Tserevelakis GJ. Sub-Diffraction Photoacoustic Microscopy Enabled by a Novel Phase-Shifted Excitation Strategy: A Numerical Study. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020498

Chicago/Turabian StyleTserevelakis, George J. 2026. "Sub-Diffraction Photoacoustic Microscopy Enabled by a Novel Phase-Shifted Excitation Strategy: A Numerical Study" Sensors 26, no. 2: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020498

APA StyleTserevelakis, G. J. (2026). Sub-Diffraction Photoacoustic Microscopy Enabled by a Novel Phase-Shifted Excitation Strategy: A Numerical Study. Sensors, 26(2), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020498