Flexible Electrospun PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofiber Piezoelectric Sensors for Passive Human Motion Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PVDF/PAN/Graphene Spinning Solution

2.2. Fabrication of PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofiber Films and Sensor Devices

2.3. Materials Characterization

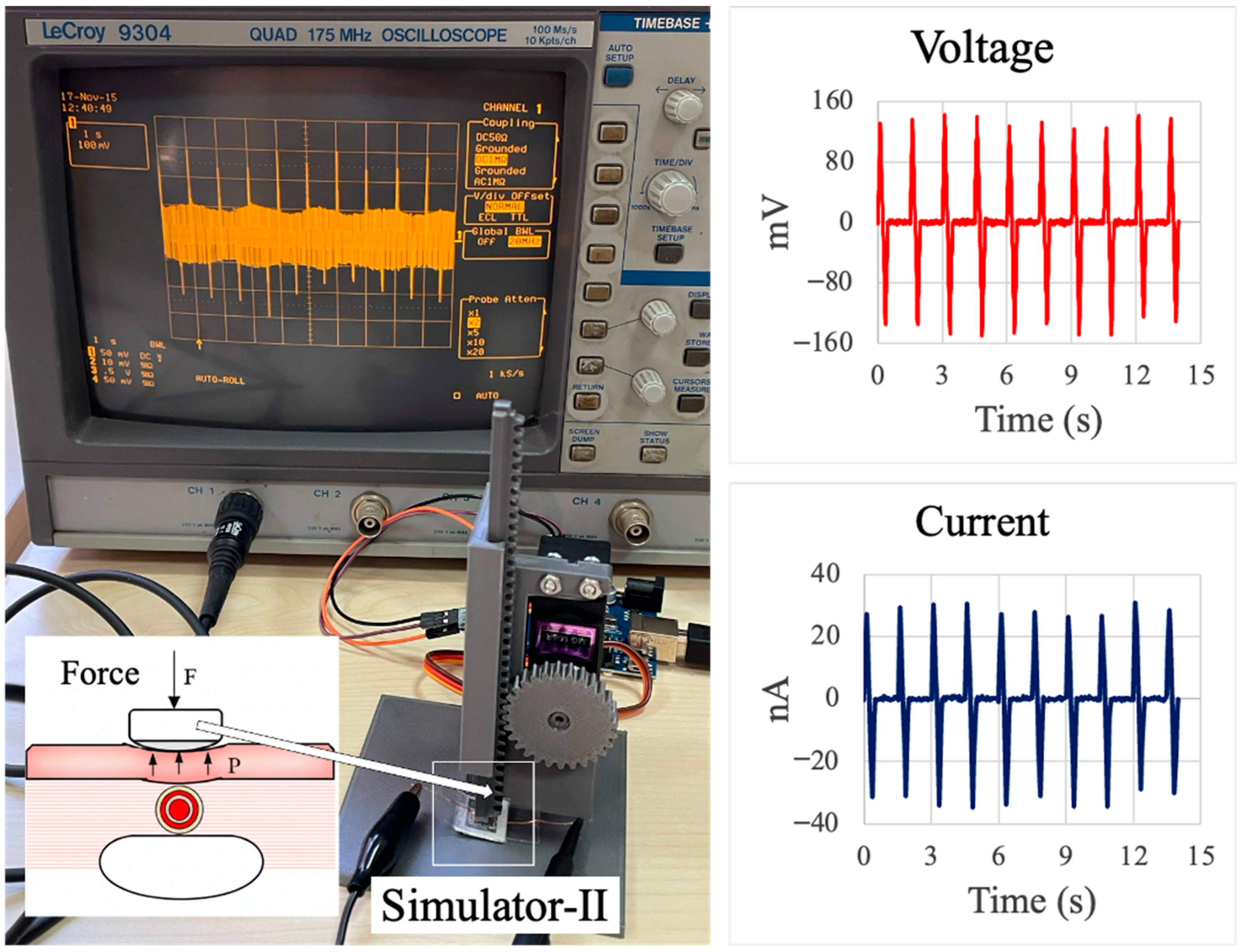

2.4. Electrical Characterization of the Sensor

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Analysis of PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofibers

3.2. FTIR Characterization of PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofibers

3.3. Custom Bending Test Device

3.4. Pressure–Voltage Measurement

3.5. Performance Evaluation of the Piezoelectric Sensor

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, C. Flexible piezoelectric materials and strain sensors for wearable electronics and artificial intelligence applications. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 16436–16466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Li, Y. Frontiers in medical physics: Material classification and blood pressure measurement of wearable piezoelectric sensors. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1529500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, C.; Yang, B.D.; Su, Y.; Tran, P.L.; Joe, P.; Anderson, E.; Xia, J.; Doraiswamy, V.; Dehdashti, B.; Feng, X.; et al. Conformal piezoelectric energy harvesting and storage from motions of the heart, lung, and diaphragm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, K.; Al Farisi, M.S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Matsushima, M.; Kawabe, T.; Shikida, M. Proof-of-concept quantitative monitoring of respiration using low-energy wearable piezoelectric thread. Electronics 2024, 13, 4577. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Hou, J.; Long, H.; Wang, M.; Wen, Z.; Yang, W.; Pan, H.; Xia, L.; Xu, W. High-Performance Degradable PLA-Based Sensors with Enhanced Strain Sensing and Triboelectric Power Generation for Wearable Devices. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 8790–8800. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, F.; Xu, L.; He, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, H. PVDF-based flexible piezoelectric tactile sensors. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2023, 58, 2300119. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning of nanofibers: Reinventing the wheel? Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sharma, V.; Mishra, P.K.; Ekielski, A. A review on polyacrylonitrile as an effective and economic constituent of adsorbents for wastewater treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovich, S.; Dikin, D.A.; Dommett, G.H.; Kohlhaas, K.M.; Zimney, E.J.; Stach, E.A.; Piner, R.D.; Nguyen, S.T.; Ruoff, R.S. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 2006, 442, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wei, X.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Xia, X.; Weng, G.J. Piezoelectricity enhancement in graphene/polyvinylidene fluoride composites due to graphene-induced α → β crystal phase transition. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 269, 116121. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari, F.; Azimi, B.; Salehi, M.; Hashemikia, S.; Danti, S. Recent advances of polymer-based piezoelectric composites for biomedical applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 122, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wu, J.; Xia, J.; Lei, W. Innovation strategy selection facilitates high-performance flexible piezoelectric sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Lu, N.; Ma, R.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, R.-H.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Won, S.M.; Tao, H.; Islam, A. Epidermal electronics. Science 2011, 333, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, H.; Ramakrishna, S. Piezoelectric materials for flexible and wearable electronics: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 211, 110164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ghahremani Arekhloo, N.; Karagiorgis, X.; Yalagala, B.P.; Skabara, P.J.; Heidari, H.; Zeze, D.A.; Hosseini, E.S. A Wearable and Highly Sensitive PVDF–TrFE–BaTiO3 Piezoelectric Sensor for Wireless Monitoring of Arterial Signal. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 7562–7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Cai, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, B.; Li, Q.; Zhang, P.; Deng, B.; Hou, P.; Liu, W. Ultrasensitive mechanical/thermal response of a P (VDF-TrFE) sensor with a tailored network interconnection interface. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Huang, W.; Guo, J.; Gong, T.; Wei, X.; Lu, B.-W.; Liu, S.-Y.; Yu, B. Ultra-sensitive strain sensor based on flexible poly (vinylidene fluoride) piezoelectric film. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Corsi, C.; Weiland, T.; Wang, Z.; Grund, T.; Pohl, O.; Bienia, J.M.; Weiss, J.; Ngo, H.D. Screen-printed PVDF piezoelectric pressure transducer for unsteadiness study of oblique shock wave boundary layer interaction. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Li, M.; Zhang, K.; Sun, D.; Lai, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Z. Development and evaluation of a flexible PVDF-based balloon sensor for detecting mechanical forces at key esophageal nodes in esophageal motility disorders. Biosensors 2023, 13, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.; Chan, H.; Or, S.W.; Cheung, Y.; Liu, P. Effect of electrode pattern on the outputs of piezosensors for wire bonding process control. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2003, 99, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cui, X.; Guo, R.; Zhang, Z.; Sang, S.; Zhang, H. Piezoelectric sensor based on graphene-doped PVDF nanofibers for sign language translation. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 11, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Xian, S.; Yu, J.; Zhao, J.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Hou, X.; Chou, X.; He, J. Synergistic enhancement properties of a flexible integrated PAN/PVDF piezoelectric sensor for human posture recognition. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.M.; Cardoso, V.F.; Martins, P.; Correia, D.M.; Goncalves, R.; Costa, P.; Correia, V.; Ribeiro, C.; Fernandes, M.M.; Martins, P.M.; et al. Smart and multifunctional materials based on electroactive poly (vinylidene fluoride): Recent advances and opportunities in sensors, actuators, energy, environmental, and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 11392–11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W. Recent progress in flexible wearable sensors for vital sign monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, M.; Mateev, V.; Iliev, I. Behavior of polymer electrode PEDOT: PSS/Graphene on flexible substrate for wearable biosensor at different loading modes. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimuldina, G.; Turdakyn, N.; Abay, I.; Medeubayev, A.; Nurpeissova, A.; Adair, D.; Bakenov, Z. A review of piezoelectric PVDF film by electrospinning and its applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulhussain, R.; Adebisi, A.; Conway, B.R.; Asare-Addo, K. Electrospun nanofibers: Exploring process parameters, polymer selection, and recent applications in pharmaceuticals and drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 90, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-Y.; Boaretti, C.; Lorenzetti, A.; Martucci, A.; Roso, M.; Modesti, M. Effects of solvent and electrospinning parameters on the morphology and piezoelectric properties of PVDF nanofibrous membrane. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolhasani, M.M.; Azimi, S.; Mousavi, M.; Anwar, S.; Hassanpour Amiri, M.; Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Naebe, M.; Michels, J.; Asadi, K. Porous graphene/poly (vinylidene fluoride) nanofibers for pressure sensing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaccio, T.; Bottino, A.; Capannelli, G.; Piaggio, P. Characterization of PVDF membranes by vibrational spectroscopy. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 210, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liao, C.; Tjong, S.C. Electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride-based fibrous scaffolds with piezoelectric characteristics for bone and neural tissue engineering. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, L. Fabrication of poly (vinylidene fluoride)/graphene nano-composite micro-parts with increased β-phase and enhanced toughness via micro-injection molding. Polymers 2021, 13, 3292. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Rault, F.; Lewandowski, M.; Mohsenzadeh, E.; Salaün, F. Electrospun PVDF nanofibers for piezoelectric applications: A review of the influence of electrospinning parameters on the β phase and crystallinity enhancement. Polymers 2021, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Su, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lu, N. Approaches for increasing the β-phase concentration of electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofibers. ES Mater. Manuf. 2019, 6, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chamankar, N.; Khajavi, R.; Yousefi, A.A.; Rashidi, A.; Golestanifard, F. A flexible piezoelectric pressure sensor based on PVDF nanocomposite fibers doped with PZT particles for energy harvesting applications. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 19669–19681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Shen, Y.; Wang, H.; Ji, K.; Mao, X.; Wei, L.; Sun, R.; Zhou, F. Electrospun PVDF-based piezoelectric nanofibers: Materials, structures, and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Chen, G.; Pan, L.; Chen, D. Electrospun flexible PVDF/GO piezoelectric pressure sensor for human joint monitoring. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 129, 109358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbal, G.B.; Tricoteaux, A.; Thuault, A.; Ageorges, H.; Roudet, F.; Chicot, D. Mechanical properties of thermally sprayed porous alumina coating by Vickers and Knoop indentation. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 19843–19851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Composition | Fabrication Method | Year | Fiber Diameter (nm) | Film Thickness (μm) | Peak Voltage | Sensitivity | Operating Range | Target Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF/PAN/Graphene/Li3PO4 | Electrospinning + fs-laser graphene | 2025 | 200–250 | 20–25 | 80–90 mV @ 120 mmHg | 0.7–0.8 mV/mmHg | 40–120 mmHg (physiological) | Pulse monitoring, wearable biomedical | This work |

| PVDF-TrFE + 3 wt% BaTiO3 | Electrospinning | 2025 | 200–300 | 43 | 9800 mV @ 16 kPa | 370 mV/kPa (6.4–16 kPa) | 6.4–16 kPa | Arterial pulse, wireless wearable | [16] |

| Graphene-doped PVDF (1 wt%) | Electrospinning | 2020 | 400–600 | 30–50 | 2000–3000 mV | 0.006 V/° (angular) | Bending 120–60°, low pressure | Gesture recognition, motion tracking | [22] |

| Porous Graphene/PVDF (0.1 wt%) | Electrospinning + spinodal decomposition | 2021 | 500–800 | 40–60 | 1500–2000 mV | Not specified | Low pressure, motion sensing | Biocompatible wearable | [30] |

| PVDF/ZnO nanorods-Graphene | Electrospinning | 2023 | 300–500 | 35 | 1700–4400 mV @ 5 N | 0.34–0.88 V/N | Medium–high pressure (up to 5 N) | Motion sensing, nanofiber devices | [37] |

| PVDF/Graphene Oxide (GO) | Electrospinning | 2022 | 250–450 | 30–40 | 4930 mV @ 120 N | 0.041 V/N | High-force impact (120 N) | Joint monitoring, impact sensing | [38] |

| PVDF + PZT nanoparticles | Solution mixing/casting | 2020 | N/A | N/A | 184 mV @ 2.125 N | 86.5 mV/N | Impact/pressure (0–2.125 N) | Energy harvesting, pressure sensor | [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cirik, H.; Kabakci, Y.G.; Basyooni-M. Kabatas, M.A.; Kiliç, H.Ş. Flexible Electrospun PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofiber Piezoelectric Sensors for Passive Human Motion Monitoring. Sensors 2026, 26, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020391

Cirik H, Kabakci YG, Basyooni-M. Kabatas MA, Kiliç HŞ. Flexible Electrospun PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofiber Piezoelectric Sensors for Passive Human Motion Monitoring. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020391

Chicago/Turabian StyleCirik, Hasan, Yasemin Gündoğdu Kabakci, M. A. Basyooni-M. Kabatas, and Hamdi Şükür Kiliç. 2026. "Flexible Electrospun PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofiber Piezoelectric Sensors for Passive Human Motion Monitoring" Sensors 26, no. 2: 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020391

APA StyleCirik, H., Kabakci, Y. G., Basyooni-M. Kabatas, M. A., & Kiliç, H. Ş. (2026). Flexible Electrospun PVDF/PAN/Graphene Nanofiber Piezoelectric Sensors for Passive Human Motion Monitoring. Sensors, 26(2), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020391