FireMM-IR: An Infrared-Enhanced Multi-Modal Large Language Model for Comprehensive Scene Understanding in Remote Sensing Forest Fire Monitoring

Highlights

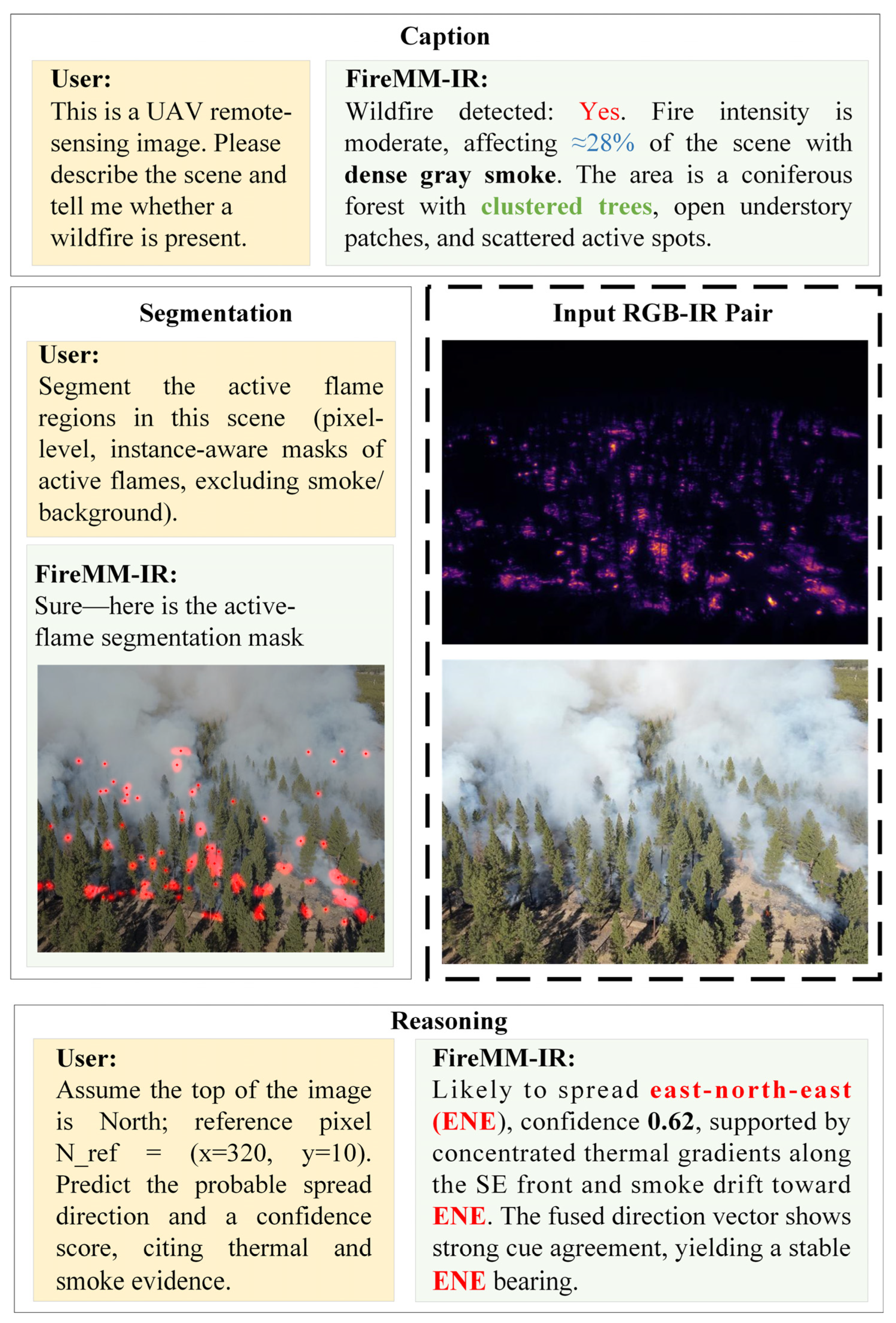

- First remote sensing multi-modal large language model for forest fire scene understanding: FireMM-IR is the first MLLM specifically designed for remote sensing forest fire imagery, enabling high-level scene understanding that integrates descriptive, analytical, and predictive insights—capabilities that conventional deep learning-based RS fire detection or segmentation models cannot provide.

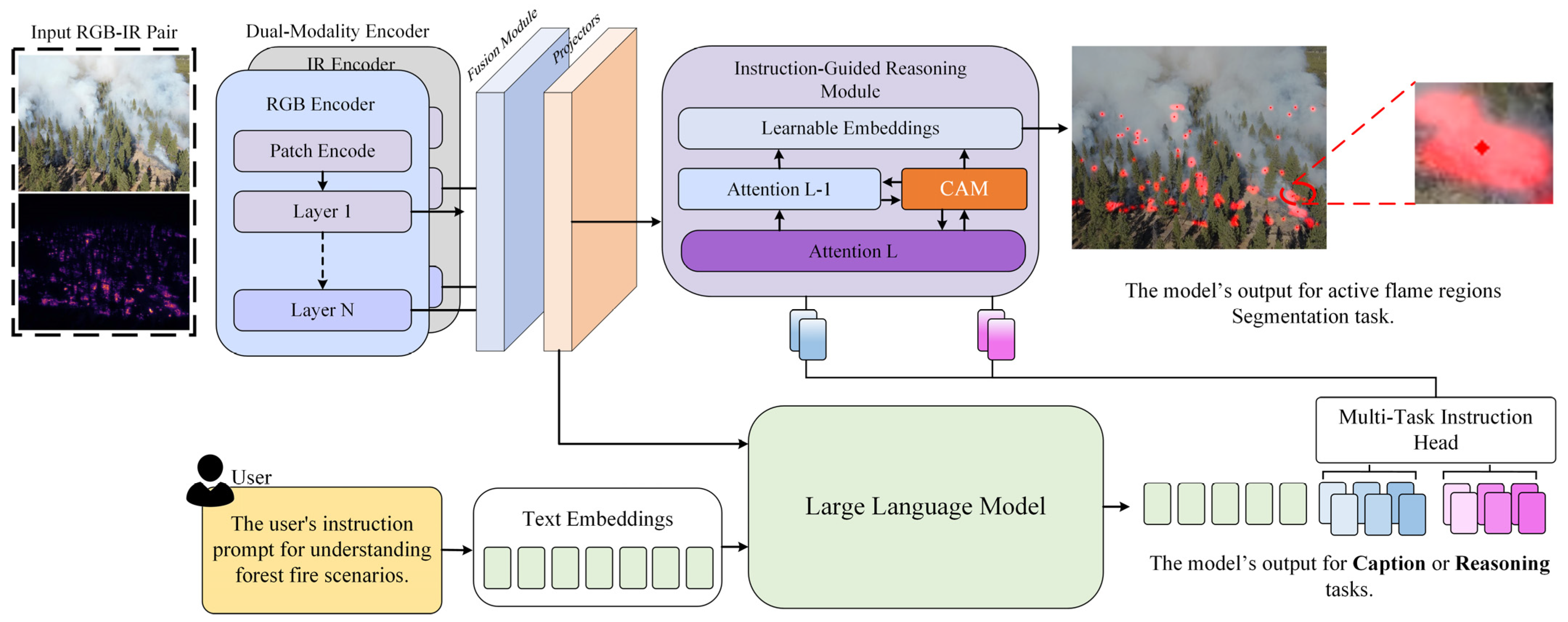

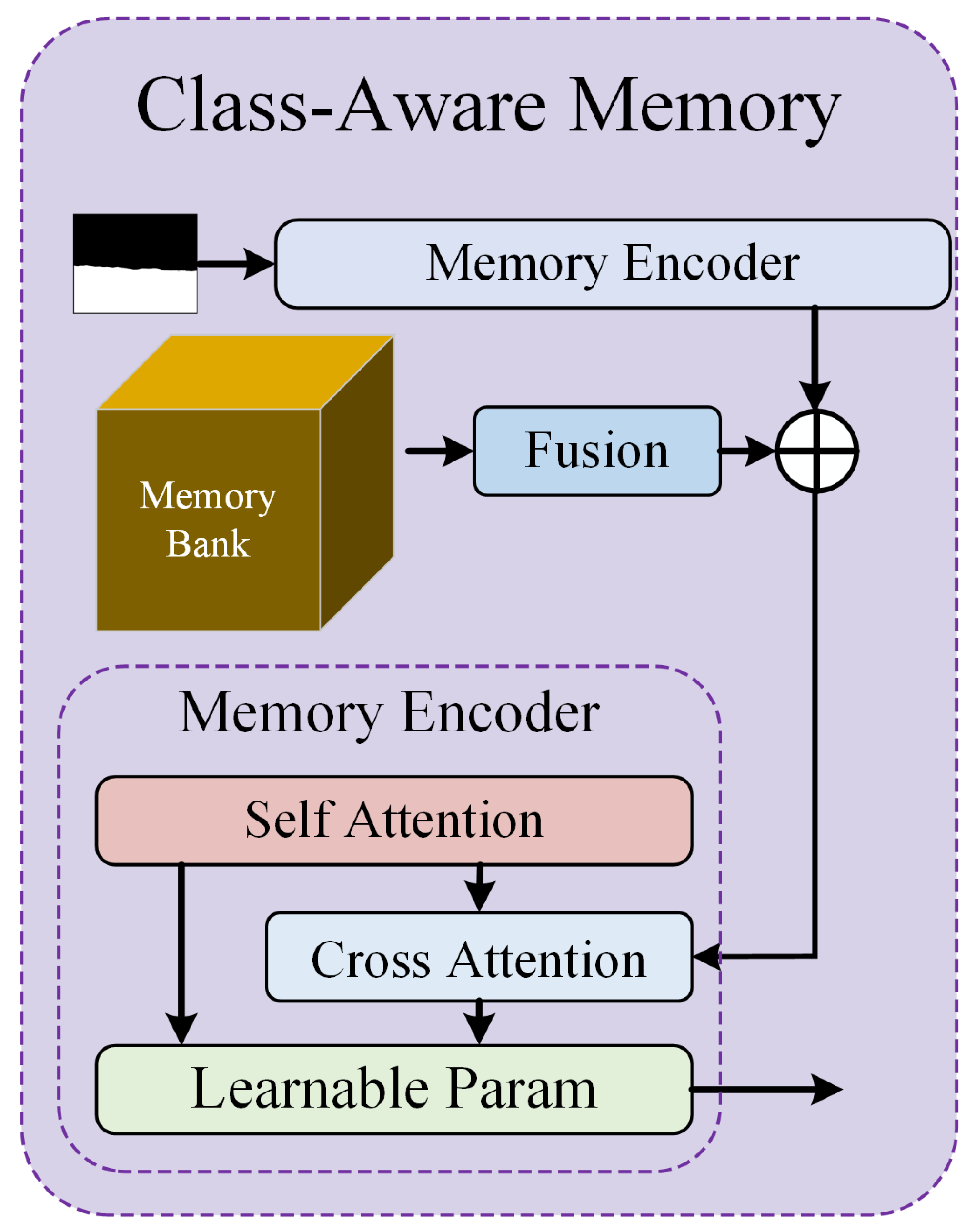

- Methodological superiority in RS applications: By fusing infrared and optical remote sensing data through a dual-modality encoder, incorporating a Class-Aware Memory (CAM) module for context-aware reasoning, and a multi-task instruction head for description, prediction, and pixel-level segmentation, FireMM-IR achieves state-of-the-art performance in remote sensing fire monitoring.

- Advances RS fire monitoring from perception to holistic scene understanding: FireMM-IR overcomes the limitations of conventional RS deep learning models, offering interpretable, instruction-driven insights into fire evolution, intensity, and spatial distribution.

- Provides actionable remote sensing solutions for disaster management: The combination of multi-spectral fusion, contextual memory, and multi-task learning allows accurate fire localization, predictive reasoning, and high-precision analysis, supporting timely decision-making in real-world RS-based forest fire scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Contributions

- We propose FireMM-IR, an infrared-enhanced multi-modal large language model for remote sensing forest fire monitoring, capable of unified scene understanding that integrates fire description, fire analysis and prediction, and pixel-level localization.

- We design a Class-Aware Memory (CAM) module that captures class-wise contextual information and enhances the semantic and spatial consistency of multi-scale fire understanding.

- We construct FireMM-Instruct, a large-scale multi-spectral dataset providing paired textual descriptions, bounding boxes, and pixel-level masks for forest fire scenes, enabling comprehensive instruction-tuned learning.

- We develop a two-stage training strategy to balance text-based reasoning and pixel-level segmentation objectives, achieving superior performance in both descriptive and analytical fire monitoring tasks.

2. Related Works

2.1. Forest-Fire Perception in Remote Sensing

2.2. Remote Sensing Multi-Modal Large Language Models

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Architecture

- (1)

- A caption describing the current fire situation;

- (2)

- A reasoning statement predicting intensity evolution and potential spread;

- (3)

- A segmentation mask localizing active fire regions.

3.2. Dual-Modality Encoder

3.3. Instruction-Guided Reasoning and Contextual Memory Mechanism

3.4. Multi-Task Instruction Head

3.5. Two-Stage Optimization Strategy

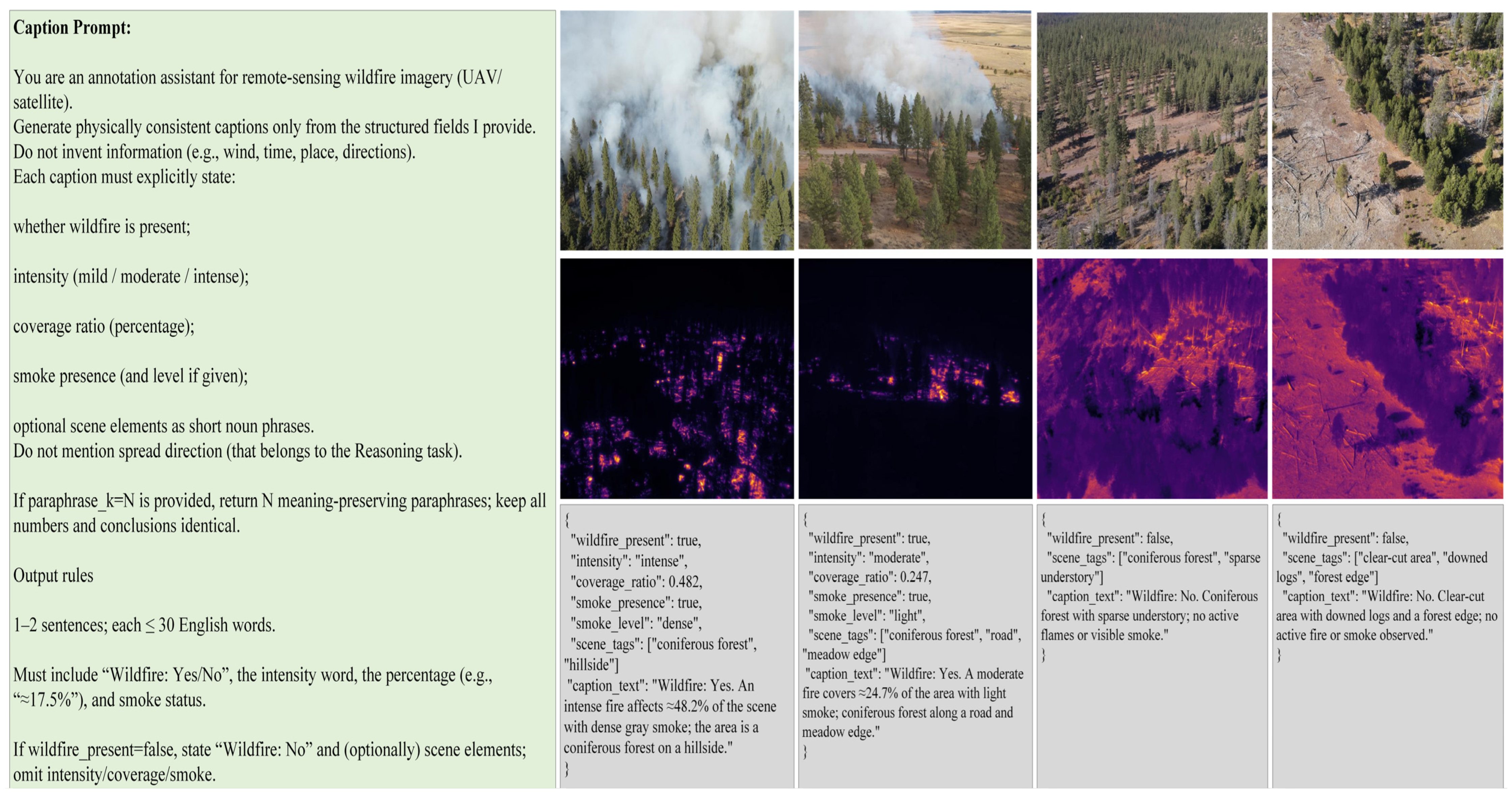

4. Dataset

4.1. Motivation and Requirements

4.2. Dataset Construction

4.2.1. Data Integration: Unifying FLAME Series into FireMM-Instruct

4.2.2. Data Annotation and Instruction Alignment

4.3. Dataset Statistics and Analysis

5. Experiments and Discussion

5.1. Implementation Details

- Captioning: evaluated using BLEU-4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, and CIDEr to measure fluency, semantic relevance, and alignment with physical descriptors.

- Reasoning: quantified by Directional Accuracy (%)—the agreement between predicted and reference spread directions—and Factual Consistency (%), computed using a GPT-based textual comparison of physical evidence (infrared or smoke cues).

- Segmentation: assessed using mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU).

5.2. Compare with Existing Models

5.3. Ablation Studies

5.4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barmpoutis, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. A review on early forest fire detection systems using optical remote sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, F.; Zidda, C.; Putzu, M.; Loru, D.; Anedda, M.; Giusto, D. Advancements in forest fire prevention: A comprehensive survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daryal, U.; Giri, A.; Karki, S.; Lepcha, P.; Alam, S.; Singh, A.P. Early Warning Systems: Enhancing Fire Prediction and Response. In Forest Fire and Climate Change: Insights into Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 451–474. [Google Scholar]

- Elvidge, C.D.; Baugh, K.E.; Ziskin, D.; Anderson, S.; Ghosh, T. Estimation of Gas Flaring Volumes Using NASA MODIS Fire Detection Products; NOAA National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC), Annual Report; NGDC: Boulder, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Escuin, S.; Navarro, R.; Fernández, P. Fire severity assessment by using NBR (Normalized Burn Ratio) and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) derived from LANDSAT TM/ETM images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.A.; Ackerman, S.A.; Holz, R.E.; Dutcher, S.; Griffith, Z. The continuity MODIS-VIIRS cloud mask. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töreyin, B.U.; Dedeoğlu, Y.; Güdükbay, U.; Çetin, A.E. Computer vision based method for real-time fire and flame detection. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, A.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, S.; Xiang, L.; Cai, C.; Wang, C. FIRE-DET: An efficient flame detection model. Nanjing Xinxi Gongcheng Daxue Xuebao 2023, 15, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, B.; O’Neill, L.; Afghah, F.; Razi, A.; Rowell, E.; Watts, A.; Fule, P.; Coen, J. Flame 2: Fire detection and modeling: Aerial multi-spectral image dataset. IEEE DataPort 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.; ONeill, L.; Marinaccio, M.; Rowell, E.; Parsons, R.; Flanary, S.; Nazim, I.; Seielstad, C.; Afghah, F. Flame 3 dataset: Unleashing the power of radiometric thermal uav imagery for wildfire management. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.02831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, C.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Rsgpt: A remote sensing vision language model and benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 224, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zheng, O.; Wang, D.; Yin, J.; Wang, Z.; Ding, S.; Yin, H.; Xu, C.; Yang, R.; Zheng, Q. ChatGPT for shaping the future of dentistry: The potential of multi-modal large language model. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadon, A.; Omama, M.; Varshney, A.; Ansari, M.S.; Sharma, R. FireNet: A specialized lightweight fire & smoke detection model for real-time IoT applications. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.11922. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.T.; Oh, T.S.; Lee, D.H. Preparation and characteristics of nitrile rubber (NBR) nanocomposites based on organophilic layered clay. Polym. Int. 2003, 52, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckreja, K.; Danish, M.S.; Naseer, M.; Das, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. Geochat: Grounded large vision-language model for remote sensing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 27831–27840. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chu, R.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. Mini-gemini: Mining the potential of multi-modality vision language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.18814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A survey of convolutional neural networks: Analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Ye, Y.; Zhu, B.; Cui, J.; Ning, M.; Jin, P.; Yuan, L. Video-llava: Learning united visual representation by alignment before projection. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 5971–5984. [Google Scholar]

- Manakitsa, N.; Maraslidis, G.S.; Moysis, L.; Fragulis, G.F. A review of machine learning and deep learning for object detection, semantic segmentation, and human action recognition in machine and robotic vision. Technologies 2024, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldamurat, K.; La Spada, L.; Zeeshan, N.; Bakyt, M.; Kuanysh, A.; bi Zhanibek, K.; Tilenbayev, A. AI-Enhanced High-Speed Data Encryption System for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Fire Detection Applications. J. Robot. Control. (JRC) 2025, 6, 1899–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Mowla, M.N.; Asadi, D.; Tekeoglu, K.N.; Masum, S.; Rabie, K. UAVs-FFDB: A high-resolution dataset for advancing forest fire detection and monitoring using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Data Brief 2024, 55, 110706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, K.; Ahmad, J.; Baik, S.W. Early fire detection using convolutional neural networks during surveillance for effective disaster management. Neurocomputing 2018, 288, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtar, D.; Li, Z.; Gu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P. Lhrs-bot: Empowering remote sensing with vgi-enhanced large multimodal language model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 440–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y. GeoPix: A multimodal large language model for pixel-level image understanding in remote sensing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 13, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Ko, B.C. Keyword-Conditioned Image Segmentation via the Cross-Attentive Alignment of Language and Vision Sensor Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persello, C.; Wegner, J.D.; Hänsch, R.; Tuia, D.; Ghamisi, P.; Koeva, M.; Camps-Valls, G. Deep learning and earth observation to support the sustainable development goals: Current approaches, open challenges, and future opportunities. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 172–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsoshoara, A.; Afghah, F.; Razi, A.; Zheng, L.; Fulé, P.Z.; Blasch, E. Aerial imagery pile burn detection using deep learning: The FLAME dataset. Comput. Netw. 2021, 193, 108001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shees, A.; Ansari, M.S.; Varshney, A.; Asghar, M.N.; Kanwal, N. Firenet-v2: Improved lightweight fire detection model for real-time iot applications. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 218, 2233–2242. [Google Scholar]

- Sivachandra, K.; Kumudham, R. A review: Object detection and classification using side scan sonar images via deep learning techniques. In Modern Approaches in Machine Learning and Cognitive Science: A Walkthrough; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 4, pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, A.; Tran, M.; Marti, E.; Cothren, J.; Rainwater, C.; Eksioglu, S.; Le, N. Land8Fire: A Complete Study on Wildfire Segmentation Through Comprehensive Review, Human-Annotated Multispectral Dataset, and Extensive Benchmarking. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Cui, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, B.; Han, J.; Zhou, W.; Yao, H.; Xie, C. How many unicorns are in this image? A safety evaluation benchmark for vision llms. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.16101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.; Roger, J.-C.; Franch, B.; Skakun, S. LaSRC (Land Surface Reflectance Code): Overview, application and validation using MODIS, VIIRS, LANDSAT and Sentinel 2 data’s. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2018—2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 8173–8176. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, D.; Qiu, C.; Jin, S.; Li, T.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, Z. Sequence matching for image-based uav-to-satellite geolocalization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5607815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X. A review on deep learning approaches to image classification and object segmentation. Comput. Mater. Contin 2019, 60, 575–597. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtkulu, S.C.; Şahin, Y.H.; Unal, G. Semantic segmentation with extended DeepLabv3 architecture. In Proceedings of the 2019 27th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Sivas, Turkey, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yuan, Y. Skyeyegpt: Unifying remote sensing vision-language tasks via instruction tuning with large language model. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 221, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Navasardyan, S.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Shi, H. Mask matching transformer for few-shot segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 823–836. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Mao, X. EarthGPT: A universal multimodal large language model for multisensor image comprehension in remote sensing domain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5917820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset/Year | Collection, Perspective | Image Type | Pre/Post Burn Data? | Radiometric Data? | Applications | Image Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIDER [28], 2020 | Web | RGB | No | No | Classification | 1000 |

| FireNet [29], 2019 | Web | RGB | No | No | Classification | 1900 |

| FireDet [30], 2020 | web | RGB | No | No | Classification | 3225 |

| FireNetv2 [31], 2023 | web | RGB | No | No | Object detection | 502 |

| UAVs-FFDB [24], 2024 | UAV | RGB | Yes | No | Classification; Modeling; Segmentation | 1635 |

| FLAME [32], 2020 | UAV, Aerial | RGB/infrared (not pairs) | No | No | Classification; Segmentation | 47,992 |

| FLAME 2 [33], 2022 | UAV, Aerial | RGB/infrared Pairs | Yes | No | Classification | 53,451 |

| FLAME 3 [34], 2024 | UAV, Aerial | Dual RGB/IR + Radiometric infrared TIFF | Yes | Yes | Classification; Modeling; Segmentation | 13,997 |

| FireMM-Instruct (ours), 2025 | UAV, Aerial (unified from FLAME series) | Paired RGB–IR Radiometric | No | Yes | Classification; Captioning; Reasoning; Segmentation; | 83,000 pairs |

| Split | Image Pairs | Fire Images | Non-Fire Images | Caption & Reasoning Templates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train set | 66,400 | 43,200 | 23,200 | 12 base templates + LLM paraphrases |

| Test set | 16,600 | 10,800 | 5800 | |

| Total set | 83,000 | 54,000 | 29,000 |

| Group | Method | Input | mIoU ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | U-Net (ResNet34) [35] | RGB | 66.8 |

| DeepLabv3+ (R101) [36] | RGB | 69.6 | |

| SegFormer-B3 [37] | RGB | 70.4 | |

| Mask2Former (R50) [38] | RGB | 71.2 | |

| LLM/Promptable | LLaVA-1.5 + SAM2 (prompt) [39] | RGB | 22.7 |

| GeoPix-style referring seg [27] | RGB | 43.9 | |

| Ours | FireMM-IR | RGB + IR | 78.2 |

| Method | BLEU-4 ↑ | METEOR ↑ | ROUGE-L ↑ | CIDEr ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniGPT4v2 [40] | 8.7 | 17.1 | 30.8 | 21.4 |

| LLaVA-1.5 [39] | 14.7 | 21.9 | 36.9 | 33.9 |

| Mini-Gemini [41] | 14.3 | 21.5 | 36.8 | 33.5 |

| GeoChat [2] | 13.8 | 21.1 | 35.2 | 28.2 |

| GeoPix [27] | 14.0 | 23.4 | 36.3 | 31.3 |

| FireMM-IR (ours) | 15.9 | 24.6 | 38.7 | 36.5 |

| Method | Directional Accuracy (%) ↑ | Factual Consistency (%) ↑ |

|---|---|---|

| MiniGPT4v2 [40] | 61.3 | 72.6 |

| LLaVA-1.5 [39] | 66.8 | 75.2 |

| Mini-Gemini [41] | 66.1 | 74.1 |

| GeoChat [2] | 68.7 | 76.4 |

| GeoPix [27] | 71.5 | 77.3 |

| FireMM-IR (ours) | 78.4 | 82.7 |

| Setting | mIoU ↑ |

|---|---|

| RGB-only | 72.1 |

| IR-only | 70.4 |

| Early fusion (concat) | 75.0 |

| Late fusion (sum) | 76.1 |

| w/o temperature gating | 76.8 |

| Ours (full) | 78.2 |

| Setting | mIoU ↑ | CIDEr ↑ |

|---|---|---|

| Single-stage | 76.0 | 34.0 |

| w/o Stage-I ε | 76.5 | 34.8 |

| w/o Stage-II up-weight | 75.4 | 34.1 |

| Two-stage (ours) | 78.2 | 36.5 |

| Setting | Input | mIoU ↑ | Prompt→Mask Match Acc. (%) ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| No instruction tokens | RGB+IR | 74.3 | 88.5 |

| LLaVA-1.5 + SAM2 [39] | RGB | 73.9 | 90.7 |

| Instruction-only (no CAM) | RGB+IR | 77.0 | 92.1 |

| Instruction + CAM (ours) | RGB+IR | 78.2 | 94.6 |

| Setting | mIoU ↑ | Directional Acc. (%) ↑ |

|---|---|---|

| w/o CAM | 77.0 | 76.1 |

| CAM (K = 64) | 77.6 | 77.4 |

| CAM (K = 128, learnable) | 78.2 | 78.4 |

| CAM (K = 256, learnable) | 78.1 | 78.3 |

| CAM (K = 128, frozen) | 77.3 | 77.0 |

| Setting | BLEU-4 ↑ | METEOR ↑ | ROUGE-L ↑ | CIDEr ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Templates-only | 15.1 | 23.5 | 37.2 | 34.2 |

| LLM-augmented (1×) | 15.6 | 24.1 | 38.0 | 35.3 |

| LLM-augmented (3×, ours) | 15.9 | 24.6 | 38.7 | 36.5 |

| LLM-augmented (5×) | 15.8 | 24.6 | 38.6 | 36.4 |

| Setting | mIoU ↑ |

|---|---|

| RGB-Only | 69.0 |

| IR-Only | 66.8 |

| Early fusion (concat) | 72.4 |

| w/o temperature gating | 74.0 |

| Ours (full) | 74.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, J.; Liu, X.; Xue, R. FireMM-IR: An Infrared-Enhanced Multi-Modal Large Language Model for Comprehensive Scene Understanding in Remote Sensing Forest Fire Monitoring. Sensors 2026, 26, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020390

Cao J, Liu X, Xue R. FireMM-IR: An Infrared-Enhanced Multi-Modal Large Language Model for Comprehensive Scene Understanding in Remote Sensing Forest Fire Monitoring. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020390

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Jinghao, Xiajun Liu, and Rui Xue. 2026. "FireMM-IR: An Infrared-Enhanced Multi-Modal Large Language Model for Comprehensive Scene Understanding in Remote Sensing Forest Fire Monitoring" Sensors 26, no. 2: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020390

APA StyleCao, J., Liu, X., & Xue, R. (2026). FireMM-IR: An Infrared-Enhanced Multi-Modal Large Language Model for Comprehensive Scene Understanding in Remote Sensing Forest Fire Monitoring. Sensors, 26(2), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020390