Volatile Profiling and Variety Discrimination of Leather Using GC-IMS Coupled with Chemometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Leather Collection and Sample Preparation

2.2. Volatile Profiles Analysis of Leather

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

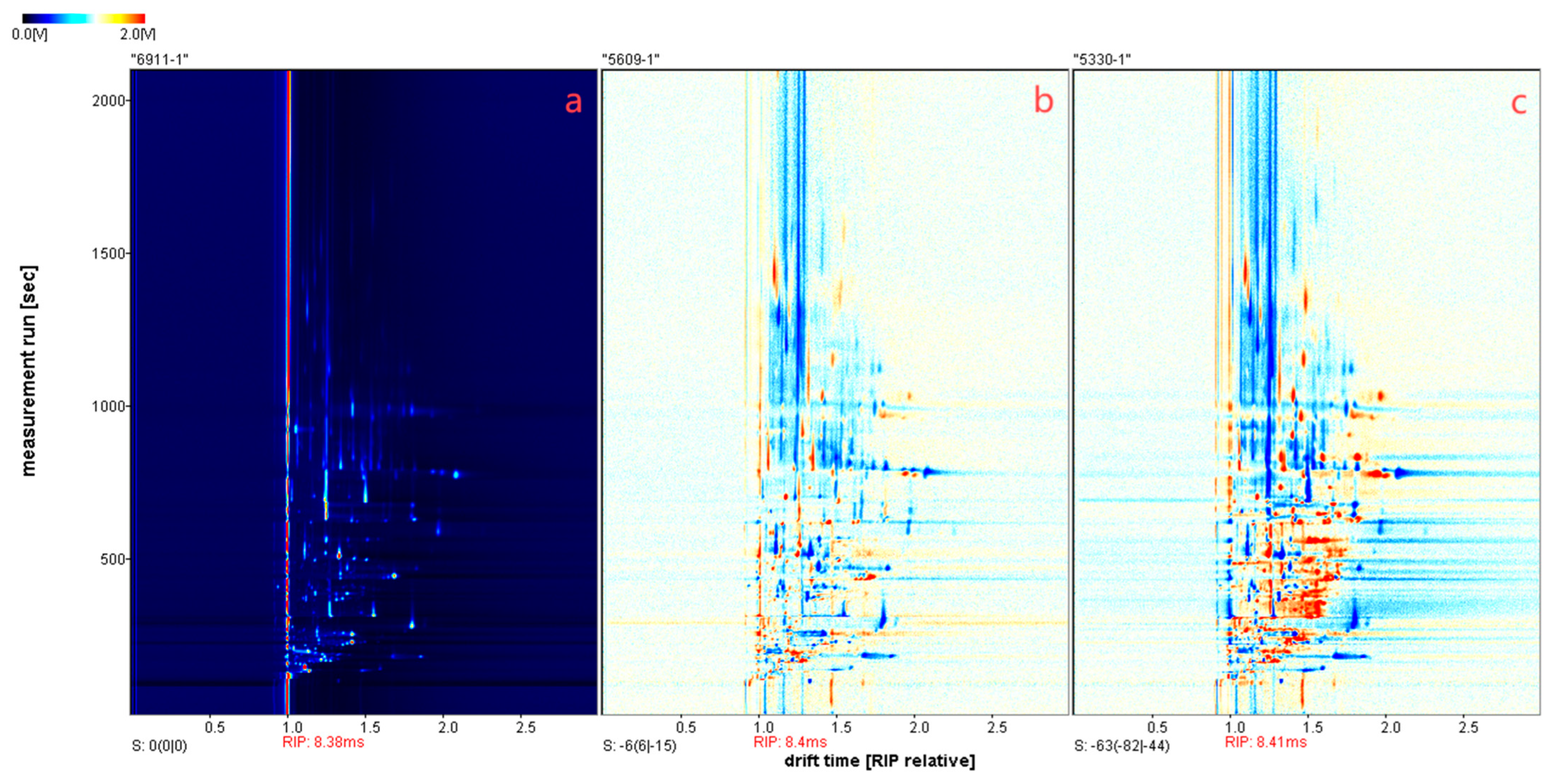

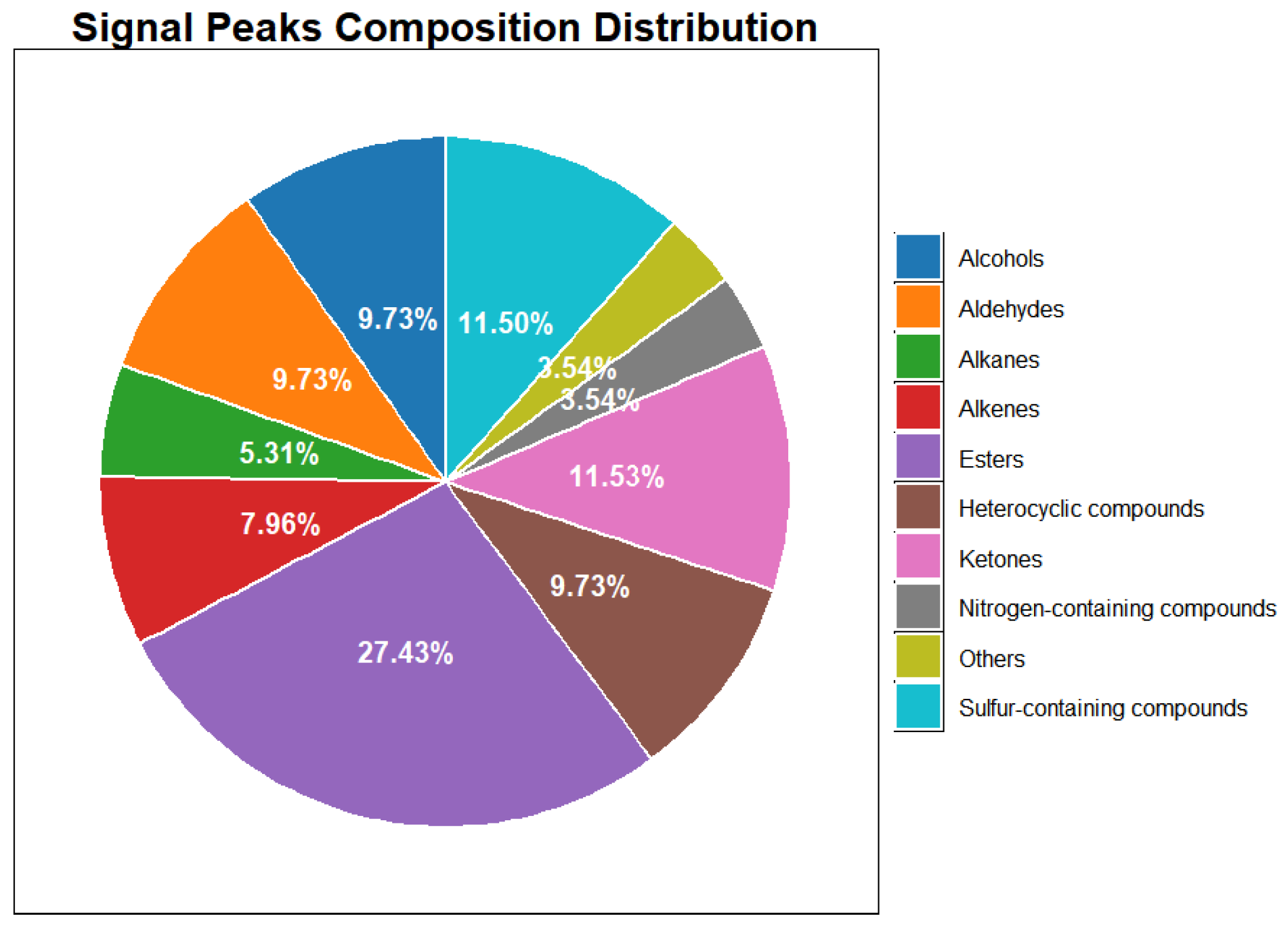

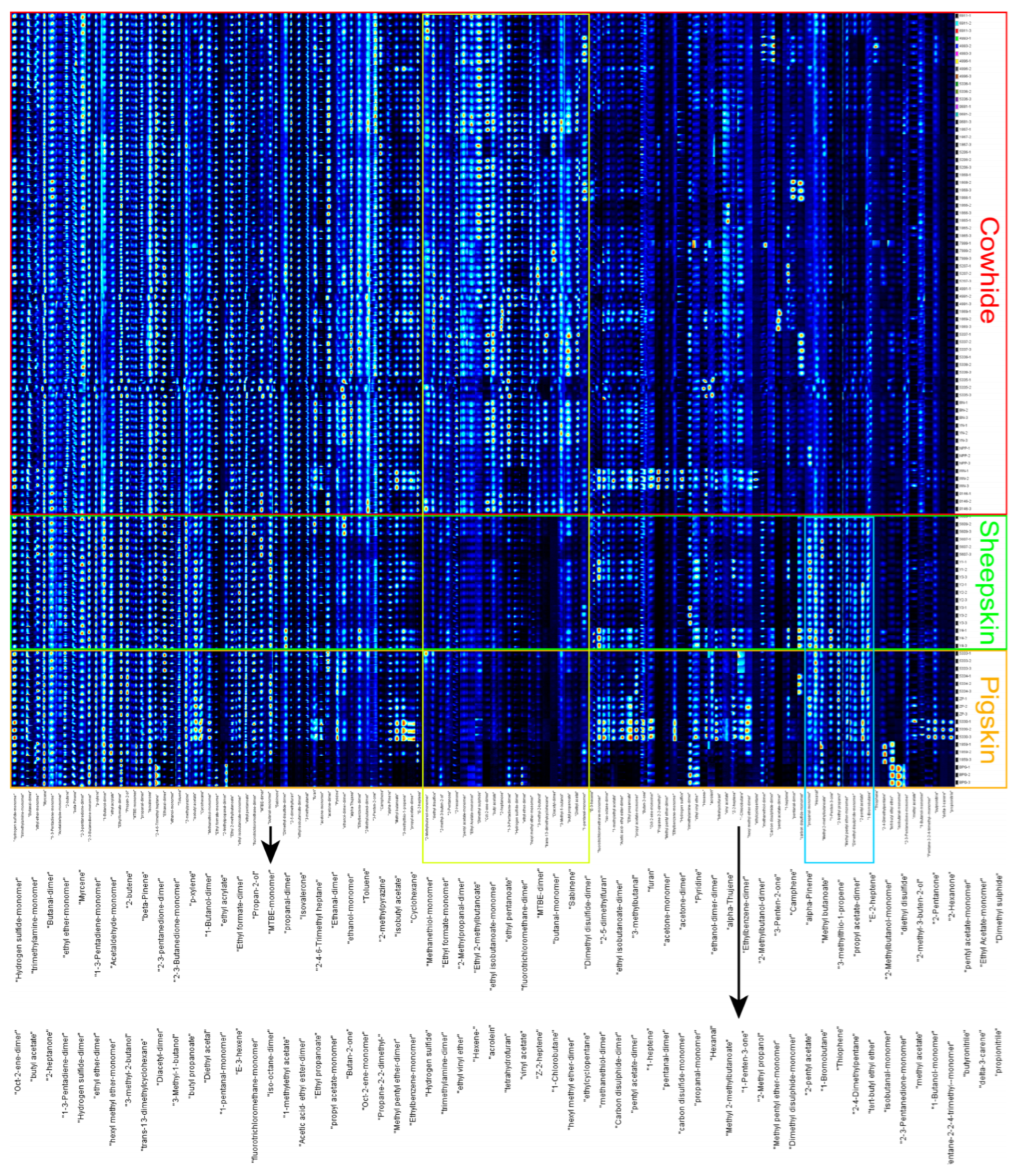

3.1. Volatile Profiles Analysis of Leather with Different Varieties

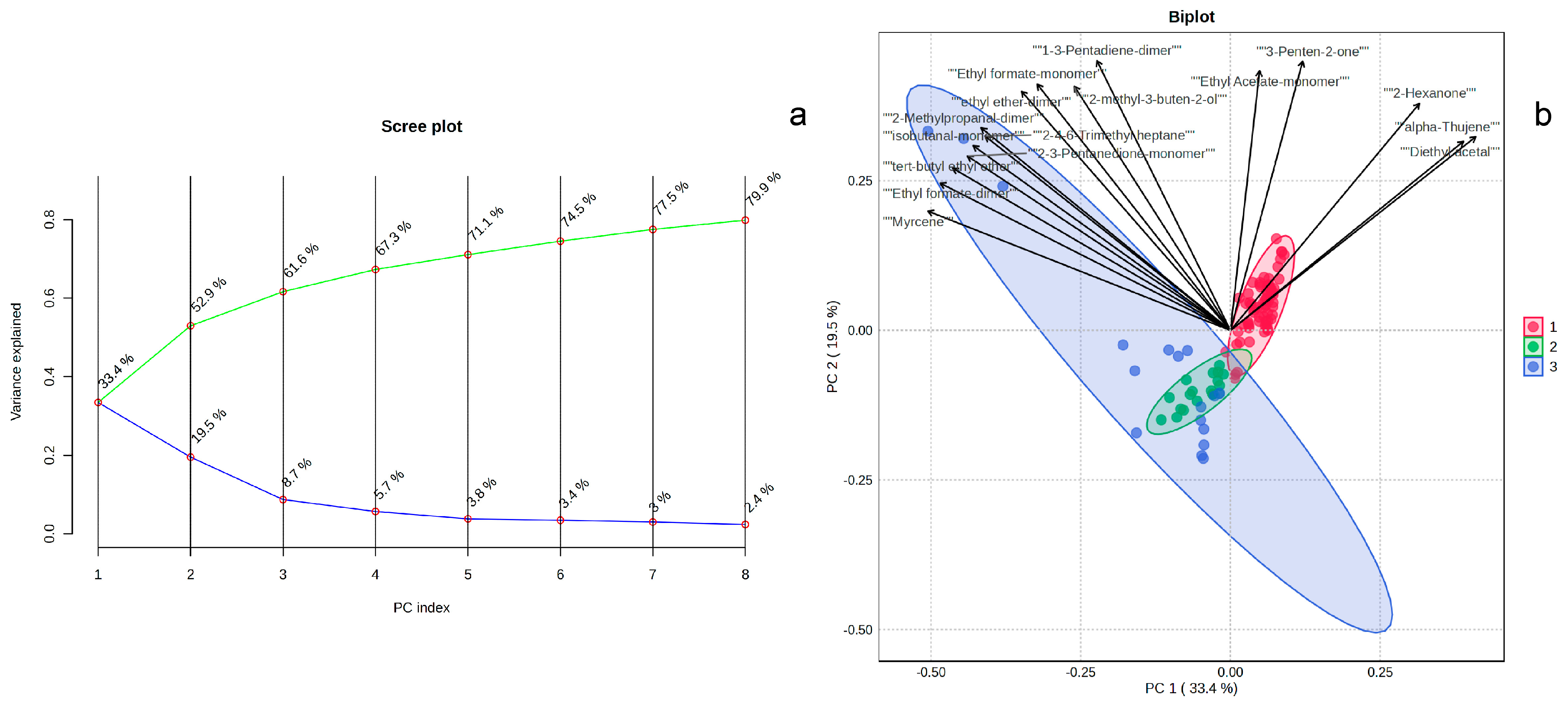

3.2. Principal Component Analysis of GC-IMS Data

3.3. Construction of Clustering Model and Elimination of Abnormal Samples

3.4. Construction of Discriminative Model and Screening of Key Signal Peaks

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, B.; Qian, Y.; Qian, X.; Fan, J.; Liu, F.; Duo, Y. Preparation and Properties of Split Microfiber Synthetic Leather. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2018, 13, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adem, M. Production of hide and skin in Ethiopia; marketing opportunities and constraints: A review paper. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1565078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Advantages of animal leather over alternatives and its medical applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 214, 113153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braz, C.E.M.; Jacinto, M.A.C.; Pereira, E.R.; Souza, G.B.; Nogueira, A.R.A. Potential of near-infrared spectroscopy for quality evaluation of cattle leather. Spectrochim. Acta Part A-Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 202, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catauro, M.; Guadagno, L.; D’Angelo, A.; Raimondo, M.; Zarrelli, M.; Piccirillo, A. Use of Spectroscopic, Mechanical, and Microbiological Analysis to Study a Natural Sheep Leather. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Design and Technologies for Polymeric and Composites Products (POLCOM), Bucharest, Romania, 23–26 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.H.; Lee, K.H. Ethical Consumers’ Awareness of Vegan Materials: Focused on Fake Fur and Fake Leather. Sustainability 2021, 13, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Feng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, M.; Li, D.; Liu, L.; et al. Discriminative analysis of aroma profiles in diverse cigar products varieties through integrated sensory evaluation, GC-IMS and E-nose. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1733, 465241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhou, D.L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, P.X. Analyses of structures for a synthetic leather made of polyurethane and microfiber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 103, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Mu, C.H.; Cheng, X.; Tang, Y.L.; Zhou, J.F.; Shi, B. Distribution, ozone formation potential, and health risk assessments of VOCs in automotive seat cushion leather during finishing process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 499, 140022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banon, E.; García, A.N.; Marcilla, A. Thermogravimetric analysis and Py-GC/MS for discrimination of leather from different animal species and tanning processes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 159, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S. The violence of odors: Sensory politics of caste in a leather tannery. Senses Soc. 2021, 16, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilla, A.; García, A.N.; León, M.; Martínez, P.; Banón, E. Study of the influence of NaOH treatment on the pyrolysis of different leather tanned using thermogravimetric analysis and Py/GC–MS system. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2011, 92, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, H.; Tian, H.; Zou, J.; Li, J. Correlation analysis of the age of brandy and volatiles in brandy by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry. Microchem. J. 2020, 157, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, D.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z. Application progress of intelligent flavor sensing system in the production process of fermented foods based on the flavor properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 3764–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, S.; Ichikawa, K. Identification of small bits of natural leather by pyrolysis gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Bunseki Kagaku 2008, 57, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Li, S.; Wen, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, J. Volatile organic organic compounds fingerprinting in faeces and urine of Alzheimer’s disease model SAMP8 mice by headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and headspace-solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1614, 460717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z.; Canfyn, M.; Vanhee, C.; Delporte, C.; Adams, E.; Deconinck, E. Evaluating MIR and NIR Spectroscopy Coupled with Multivariate Analysis for Detection and Quantification of Additives in Tobacco Products. Sensors 2024, 24, 7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Seo, S.B.; Bae, Y.S. A Semi-Automatic Labeling Framework for PCB Defects via Deep Embeddings and Density-Aware Clustering. Sensors 2025, 25, 6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-K.; Lan, Y.-B.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Duan, C.-Q. Targeted metabolomics of anthocyanin derivatives during prolonged wine aging: Evolution, color contribution and aging prediction. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Liu, A.G.; Candy, C.; Martin, A.; Avery, J.A. Naturalistic food categories are driven by subjective estimates rather than objective measures of food qualities. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Li, Y. K-means algorithm of clustering number and centers self-determination. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2018, 54, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Punhani, A.; Faujdar, N.; Mishra, K.K.; Subramanian, M. Binning-Based Silhouette Approach to Find the Optimal Cluster Using K-Means. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 115025–115032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, E.; Saccenti, E.; Smilde, A.K.; Westerhuis, J.A. Double-check: Validation of diagnostic statistics for PLS-DA models in metabolomics studies. Metabolomics 2012, 8, S3–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, L. Classification of Different Dried Vine Fruit Varieties in China by HS-SPME-GC-MS Combined with Chemometrics. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2856–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Huang, G.; Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Lu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Deng, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H. Effects of Monascus purpureus on ripe Pu-erh tea in different fermentation methods and identification of characteristic volatile compounds. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Q.; Liu, S.; Hong, P.; Zhou, C.; Zhong, S. Characterization of the effect of different cooking methods on volatile compounds in fish cakes using a combination of GC-MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem.-X 2024, 22, 101291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Count | Compound | CAS | RI α | Rt (s) β | Dt (ms) γ | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Propane, 2,2-dimethyl- | 463-82-1 | 379.9 | 108.116 | 1.3318 | |

| 2 | Hydrogen sulfide | 7783-06-4 | 455.4 | 129.271 | 1.5488 | |

| 3 | Hydrogen sulfide | 7783-06-4 | 484.4 | 138.855 | 1.143 | monomer |

| 4 | Hydrogen sulfide | 7783-6-4 | 491 | 141.179 | 1.5009 | dimer |

| 5 | Trimethylamine | 75-50-3 | 544.8 | 162.041 | 1.0833 | monomer |

| 6 | Trimethylamine | 75-50-3 | 545 | 162.131 | 1.0521 | dimer |

| 7 | Fluorotrichloromethane | 83589-40-6 | 578.3 | 177.02 | 1.2807 | dimer |

| 8 | 2,4-dimethylpentane | 108-08-7 | 581.3 | 178.408 | 1.33 | |

| 9 | Ethyl ether | 60-29-7 | 586 | 180.702 | 1.0579 | monomer |

| 10 | Fluorotrichloromethane | 83589-40-6 | 594.9 | 185.07 | 1.2418 | monomer |

| 11 | Ethyl ether | 60-29-7 | 595 | 185.093 | 1.7039 | dimer |

| 12 | 1,3-pentadiene | 504-60-9 | 597.1 | 186.151 | 1.8622 | dimer |

| 13 | (E)-3-hexene | 13269-52-8 | 613.6 | 194.646 | 1.2246 | |

| 14 | Ethyl vinyl ether | 109-92-2 | 617 | 196.448 | 1.2858 | |

| 15 | 1,3-pentadiene | 504-60-9 | 617 | 196.463 | 1.1814 | monomer |

| 16 | Pentane, 2,2,4-trimethyl- | 540-84-1 | 622.6 | 199.5 | 1.3717 | monomer |

| 17 | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | 1634-04-4 | 632.3 | 204.879 | 1.1084 | monomer |

| 18 | Acetaldehyde | 75-07-0 | 644.6 | 211.924 | 1.0176 | monomer |

| 19 | Methanethiol | 74-93-1 | 647.7 | 213.724 | 1.0416 | monomer |

| 20 | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | 1634-04-4 | 662.3 | 222.569 | 1.1165 | dimer |

| 21 | Hexene- | 592-41-6 | 665.2 | 224.396 | 1.3474 | |

| 22 | Isooctane | 540-84-1 | 673.7 | 229.822 | 1.3768 | dimer |

| 23 | Ethanal | 75-07-0 | 681.8 | 235.061 | 1.4181 | dimer |

| 24 | Dimethyl sulphide | 75-18-3 | 682.2 | 235.377 | 1.4999 | |

| 25 | 2-butene | 107-01-7 | 683.1 | 235.927 | 1.2078 | |

| 26 | tert-Butyl ethyl ether | 637-92-3 | 688.4 | 239.501 | 1.0649 | |

| 27 | Carbon disulfide | 75-15-0 | 692.9 | 242.564 | 1.096 | monomer |

| 28 | Methanethiol | 74-93-1 | 697.6 | 245.836 | 1.0462 | dimer |

| 29 | Carbon disulphide | 75-15-0 | 706.4 | 252.009 | 1.239 | dimer |

| 30 | (E)-2-heptene | 14686-13-6 | 717.5 | 260.128 | 1.4338 | |

| 31 | 1-heptene | 592-76-7 | 719.5 | 261.63 | 1.2951 | |

| 32 | Propanal | 123-38-6 | 722.5 | 263.88 | 1.0749 | monomer |

| 33 | Propanal | 123-38-6 | 725.1 | 265.854 | 1.1928 | dimer |

| 34 | Cyclohexane | 110-82-7 | 732.2 | 271.286 | 1.1105 | |

| 35 | Methyl pentyl ether | 628-80-8 | 745.2 | 281.703 | 1.029 | monomer |

| 36 | Methyl pentyl ether | 628-80-8 | 769.3 | 302.063 | 1.238 | dimer |

| 37 | ethylcyclopentane | 1640-89-7 | 769.7 | 302.375 | 1.6186 | |

| 38 | Ethyl formate | 109-94-4 | 773.4 | 305.734 | 1.812 | monomer |

| 39 | (Z)-2-heptene | 6443-92-1 | 778.5 | 310.276 | 1.1988 | |

| 40 | Methyl acetate | 79-20-9 | 782.7 | 314.139 | 1.5219 | |

| 41 | Furan | 110-00-9 | 798 | 328.564 | 1.473 | |

| 42 | Isobutanal | 78-84-2 | 798.6 | 329.101 | 1.3678 | monomer |

| 43 | 2-methylpropanal | 78-84-2 | 798.7 | 329.244 | 1.1604 | dimer |

| 44 | Acetone | 67-64-1 | 806.4 | 336.792 | 1.5628 | monomer |

| 45 | Butanal | 123-72-8 | 811.3 | 341.676 | 1.2846 | dimer |

| 46 | 1-methylethyl acetate | 108-21-4 | 836.9 | 368.634 | 1.1769 | |

| 47 | Oct-2-ene | 111-67-1 | 839 | 370.919 | 1.315 | dimer |

| 48 | Acetic acid, ethyl ester | 141-78-6 | 841.2 | 373.393 | 1.3519 | dimer |

| 49 | Butanal | 123-72-8 | 841.3 | 373.457 | 1.0976 | monomer |

| 50 | 1-chlorobutane | 109-69-3 | 842.5 | 374.798 | 1.4096 | |

| 51 | Acetone | 67-64-1 | 842.9 | 375.236 | 1.1251 | dimer |

| 52 | Oct-2-ene | 111-67-1 | 850.9 | 384.331 | 1.4867 | monomer |

| 53 | 2,4,6-trimethyl heptane | 2613-61-8 | 855.9 | 390.118 | 1.3973 | |

| 54 | Ethyl formate | 109-94-4 | 856.5 | 390.875 | 1.1718 | dimer |

| 55 | Ethyl acetate | 141-78-6 | 856.8 | 391.176 | 1.3159 | monomer |

| 56 | Acrolein | 107-02-8 | 864.1 | 399.795 | 1.0715 | |

| 57 | 3-methylbutanal | 590-86-3 | 872.6 | 410.114 | 1.1927 | |

| 58 | Butan-2-one | 78-93-3 | 877.8 | 416.684 | 1.2697 | |

| 59 | trans-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane | 2207-03-6 | 879.9 | 419.259 | 1.4252 | |

| 60 | Diethyl acetal | 105-57-7 | 881.6 | 421.385 | 1.1399 | |

| 61 | Ethyl propanoate | 105-37-3 | 896.8 | 441.186 | 1.6222 | |

| 62 | tetrahydrofuran | 109-99-9 | 900 | 445.476 | 1.6434 | |

| 63 | Ethyl isobutanoate | 97-62-1 | 901.8 | 447.994 | 1.6911 | monomer |

| 64 | 1-pentanal | 110-62-3 | 907.5 | 455.769 | 1.4088 | monomer |

| 65 | Pentanal | 110-62-3 | 913.9 | 464.679 | 1.4319 | dimer |

| 66 | Hexyl methyl ether | 4747-07-3 | 915.5 | 466.98 | 1.2256 | dimer |

| 67 | Vinyl acetate | 108-05-4 | 919 | 471.871 | 1.622 | |

| 68 | Diacetyl | 431-03-8 | 920.7 | 474.298 | 1.8371 | dimer |

| 69 | 1-bromobutane | 109-65-9 | 921.9 | 476.124 | 1.0954 | |

| 70 | Hexyl methyl ether | 4747-07-3 | 923 | 477.676 | 1.3968 | monomer |

| 71 | Propan-2-ol | 67-63-0 | 938.5 | 500.715 | 1.1769 | |

| 72 | Propyl acetate | 109-60-4 | 939.1 | 501.693 | 1.5123 | monomer |

| 73 | Ethyl isobutanoate | 97-62-1 | 941.8 | 505.795 | 1.4342 | dimer |

| 74 | 2,5-dimethylfuran | 625-86-5 | 946.9 | 513.048 | 1.3411 | |

| 75 | 2-pentanone | 107-87-9 | 952.2 | 522.155 | 1.1397 | |

| 76 | Methyl butanoate | 623-42-7 | 953.2 | 523.81 | 1.2479 | |

| 77 | Ethanol | 64-17-5 | 957.2 | 530.329 | 1.1107 | monomer |

| 78 | Ethanol | 64-17-5 | 967.6 | 547.455 | 1.144 | dimer |

| 79 | 3-(methylthio)-1-propene | 10152-76-8 | 978.8 | 566.602 | 1.5189 | |

| 80 | Propyl acetate | 109-60-4 | 980.1 | 568.886 | 1.591 | dimer |

| 81 | Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | 7452-79-1 | 984.3 | 576.38 | 1.2498 | |

| 82 | Thiophene | 110-02-1 | 993.4 | 592.674 | 2.0955 | |

| 83 | 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol | 115-18-4 | 999.2 | 603.426 | 1.982 | |

| 84 | 2,3-butanedione | 431-03-8 | 1009.5 | 622.947 | 1.1548 | monomer |

| 85 | 1-penten-3-one | 1629-58-9 | 1011.3 | 626.475 | 1.456 | |

| 86 | Isobutyl acetate | 110-19-0 | 1012.2 | 628.154 | 1.6298 | |

| 87 | Ethyl acrylate | 1408-8-5 | 1016.2 | 635.904 | 1.4152 | |

| 88 | Alpha-pinene | 80-56-8 | 1019.3 | 642.148 | 1.8121 | |

| 89 | Methyl 2-methylbutanoate | 868-57-5 | 1028 | 659.752 | 1.0758 | |

| 90 | alpha-thujene | 2867-05-2 | 1036.1 | 676.501 | 1.8107 | |

| 91 | Propionitrile | 107-12-0 | 1039.7 | 682.903 | 1.6689 | |

| 92 | Butyl acetate | 123-86-4 | 1050.7 | 707.915 | 1.4015 | |

| 93 | 2,3-pentanedione | 600-14-6 | 1050.9 | 708.423 | 1.2415 | monomer |

| 94 | 2-methyl propanol | 78-83-1 | 1051.4 | 709.576 | 1.1786 | |

| 95 | Toluene | 108-83-8 | 1059.9 | 728.594 | 1.0302 | |

| 96 | Butyronitrile | 109-74-0 | 1063.6 | 737.001 | 1.3336 | |

| 97 | 2-hexanone | 591-78-6 | 1064.7 | 739.541 | 1.5034 | |

| 98 | beta-pinene | 127-91-3 | 1081.6 | 779.633 | 1.4939 | |

| 99 | Camphene | 79-92-5 | 1082.8 | 782.662 | 2.1019 | |

| 100 | Dimethyl disulphide | 624-92-0 | 1084 | 785.563 | 1.9874 | monomer |

| 101 | 2-pentyl acetate | 53496-15-4 | 1084.4 | 786.42 | 1.9273 | |

| 102 | 3-penten-2-one | 625-33-2 | 1098.8 | 822.725 | 1.533 | |

| 103 | 2,3-pentanedione | 600-14-6 | 1099.9 | 825.49 | 1.2307 | dimer |

| 104 | delta-3-carene | 13466-78-9 | 1103.6 | 835.155 | 1.8255 | |

| 105 | Ethylbenzene | 100-41-4 | 1104.6 | 837.785 | 1.5932 | monomer |

| 106 | Ethyl pentanoate | 539-82-2 | 1108.1 | 846.941 | 1.067 | |

| 107 | Sabinene | 3387-41-5 | 1109.1 | 849.775 | 1.3507 | |

| 108 | 3-methyl-2-butanol | 598-75-4 | 1111.8 | 856.801 | 1.4296 | |

| 109 | 1-butanol | 71-36-3 | 1121.1 | 882.027 | 1.3987 | monomer |

| 110 | 1-butanol | 71-36-3 | 1135.5 | 922.724 | 1.165 | dimer |

| 111 | Butyl propanoate | 590-01-2 | 1136.8 | 926.422 | 1.2831 | |

| 112 | p-Xylene | 106-42-3 | 1138.7 | 932.193 | 1.0633 | |

| 113 | Hexanal | 66-25-1 | 1150.1 | 966.019 | 1.5509 | |

| 114 | Pentyl acetate | 628-63-7 | 1157.3 | 987.804 | 1.7517 | monomer |

| 115 | Isovalerone | 108-83-8 | 1158 | 989.942 | 1.8 | |

| 116 | Myrcene | 123-35-3 | 1159.2 | 993.738 | 1.4226 | |

| 117 | Ethylbenzene | 100-41-4 | 1159.3 | 994.188 | 1.655 | dimer |

| 118 | Dimethyl disulfide | 624-92-0 | 1161.9 | 1002.07 | 1.1443 | dimer |

| 119 | Pyridine | 110-86-1 | 1173.4 | 1038.763 | 1.4065 | |

| 120 | 2-methylbutanol | 137-32-6 | 1176.2 | 1047.912 | 1.2216 | dimer |

| 121 | Pentyl acetate | 628-63-7 | 1201.3 | 1133.621 | 1.7843 | dimer |

| 122 | 2-heptanone | 110-43-0 | 1204.4 | 1144.726 | 1.2709 | |

| 123 | 2-methylbutanol | 137-32-6 | 1219.1 | 1198.459 | 1.1739 | monomer |

| 124 | 3-methyl-1-butanol | 123-51-3 | 1220.9 | 1205.32 | 1.2351 | |

| 125 | Diethyl disulfide | 110-81-6 | 1255.2 | 1341.576 | 1.13 | |

| 126 | 2-methylpyrazine | 109-08-0 | 1272.8 | 1417.545 | 1.1038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, Z. Volatile Profiling and Variety Discrimination of Leather Using GC-IMS Coupled with Chemometric Analysis. Sensors 2026, 26, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020382

Wang L, Li S, Zhou X, Lu Y, Wang X, Wei Z. Volatile Profiling and Variety Discrimination of Leather Using GC-IMS Coupled with Chemometric Analysis. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020382

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lingxia, Siying Li, Xuejun Zhou, Yang Lu, Xiaoqing Wang, and Zhenbo Wei. 2026. "Volatile Profiling and Variety Discrimination of Leather Using GC-IMS Coupled with Chemometric Analysis" Sensors 26, no. 2: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020382

APA StyleWang, L., Li, S., Zhou, X., Lu, Y., Wang, X., & Wei, Z. (2026). Volatile Profiling and Variety Discrimination of Leather Using GC-IMS Coupled with Chemometric Analysis. Sensors, 26(2), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020382