Monocular Near-Infrared Optical Tracking with Retroreflective Fiducial Markers for High-Accuracy Image-Guided Surgery

Highlights

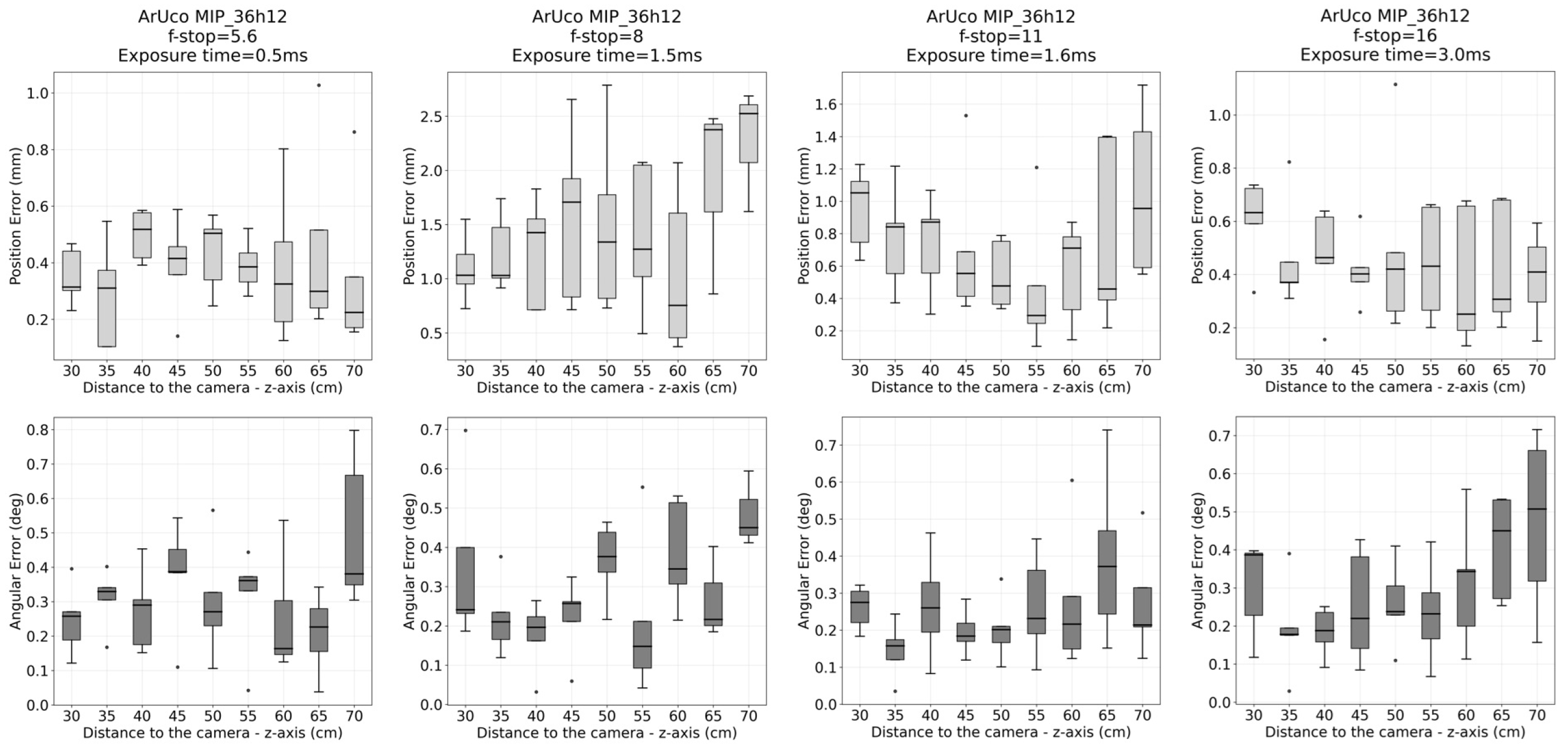

- A monocular near-infrared optical tracking system using compact dodecahedral retroreflective markers achieves submillimeter and sub-degree accuracy.

- The ArUco MIP_36h12 fiducial family offers the best performance, with translational errors of 0.44 ± 0.20 mm and rotational errors of 0.35 ± 0.16° at distances of 30–70 cm, as measured from static position estimates.

- The system offers a compact, low-latency, and high-precision alternative to traditional multi-camera tracking setups in surgical navigation.

- Its sterilizable, CT/MRI-compatible marker design makes it suitable for integration into image-guided surgical workflows.

Abstract

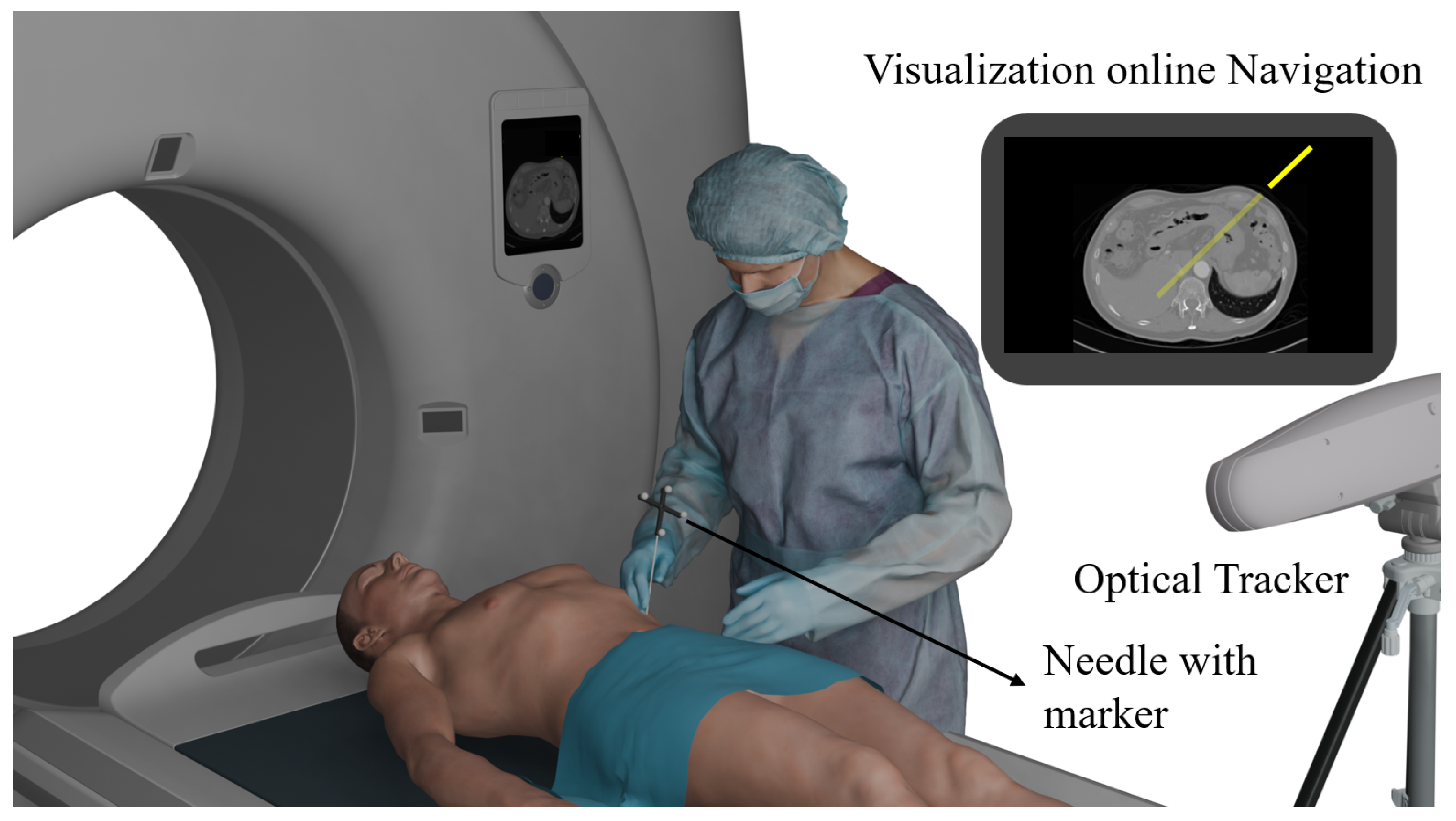

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

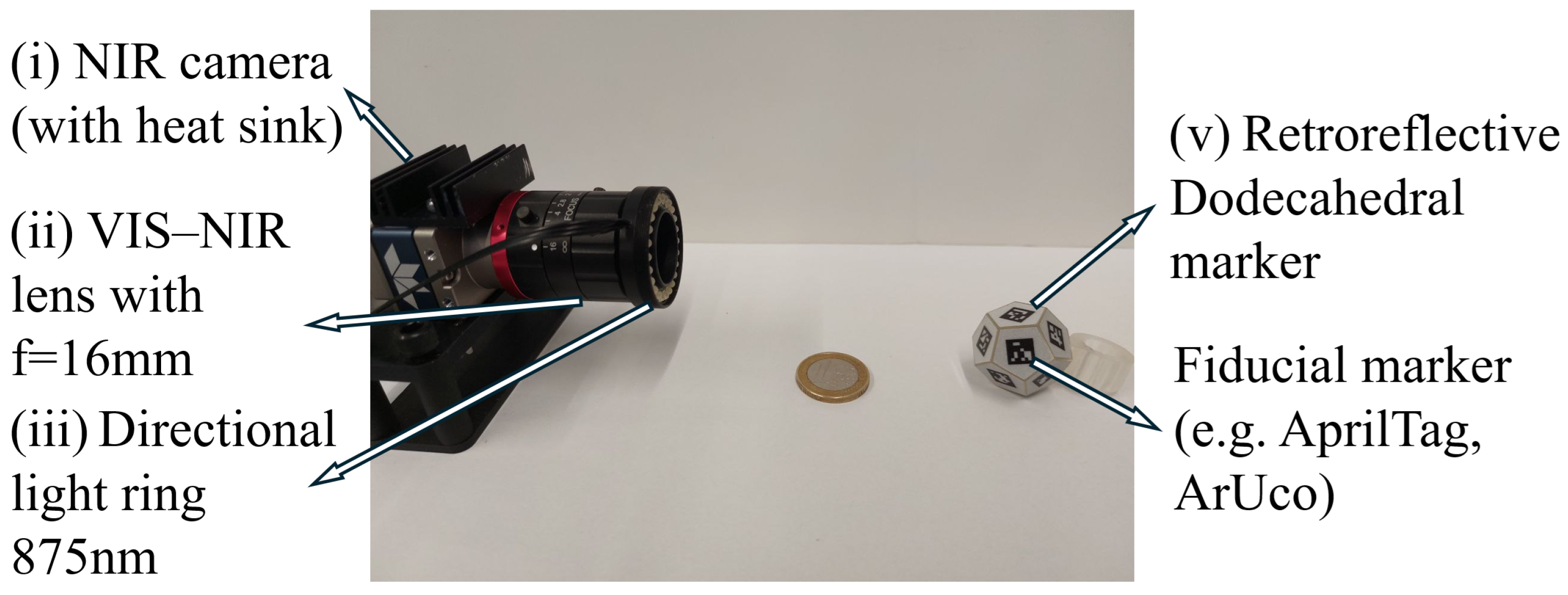

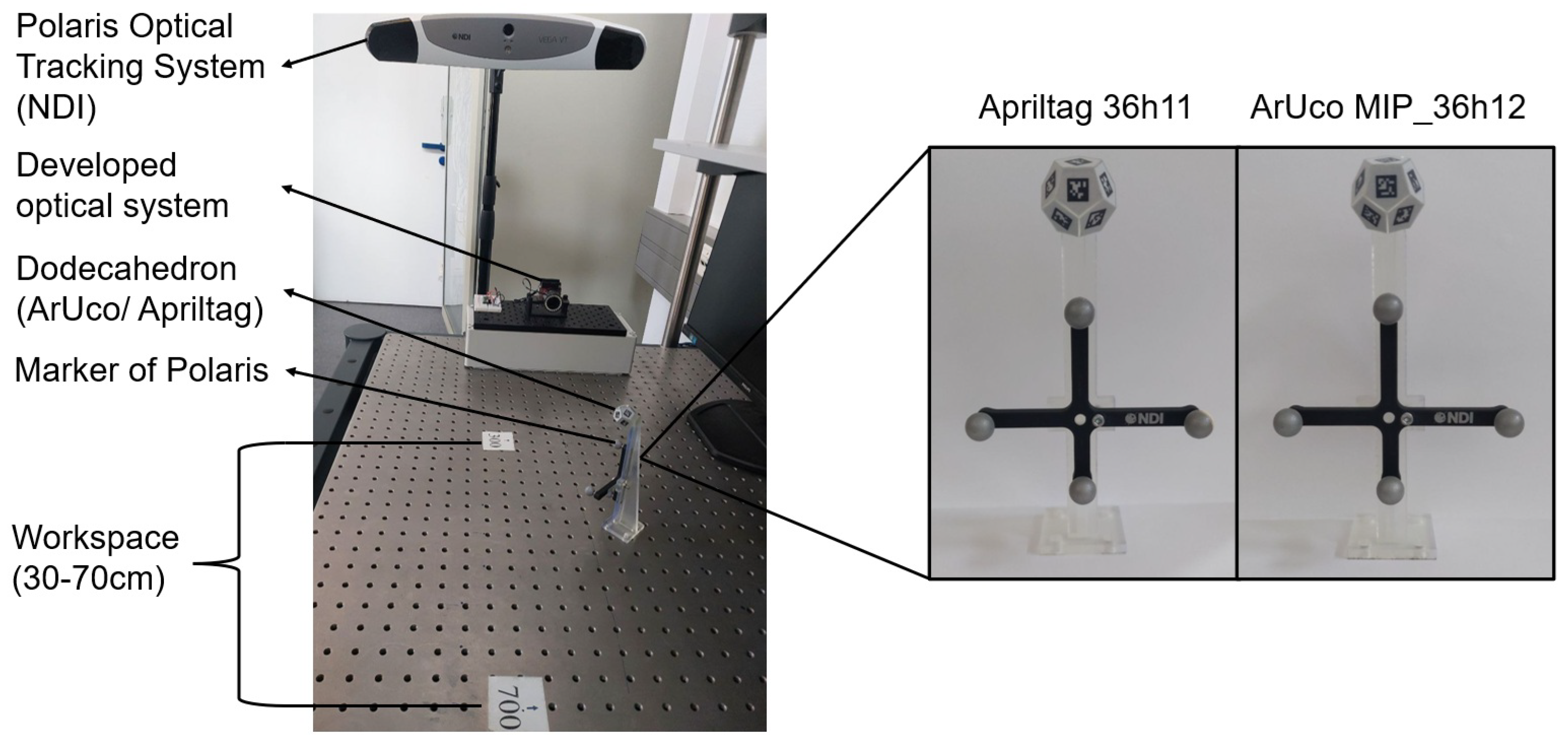

2.1. Physical System

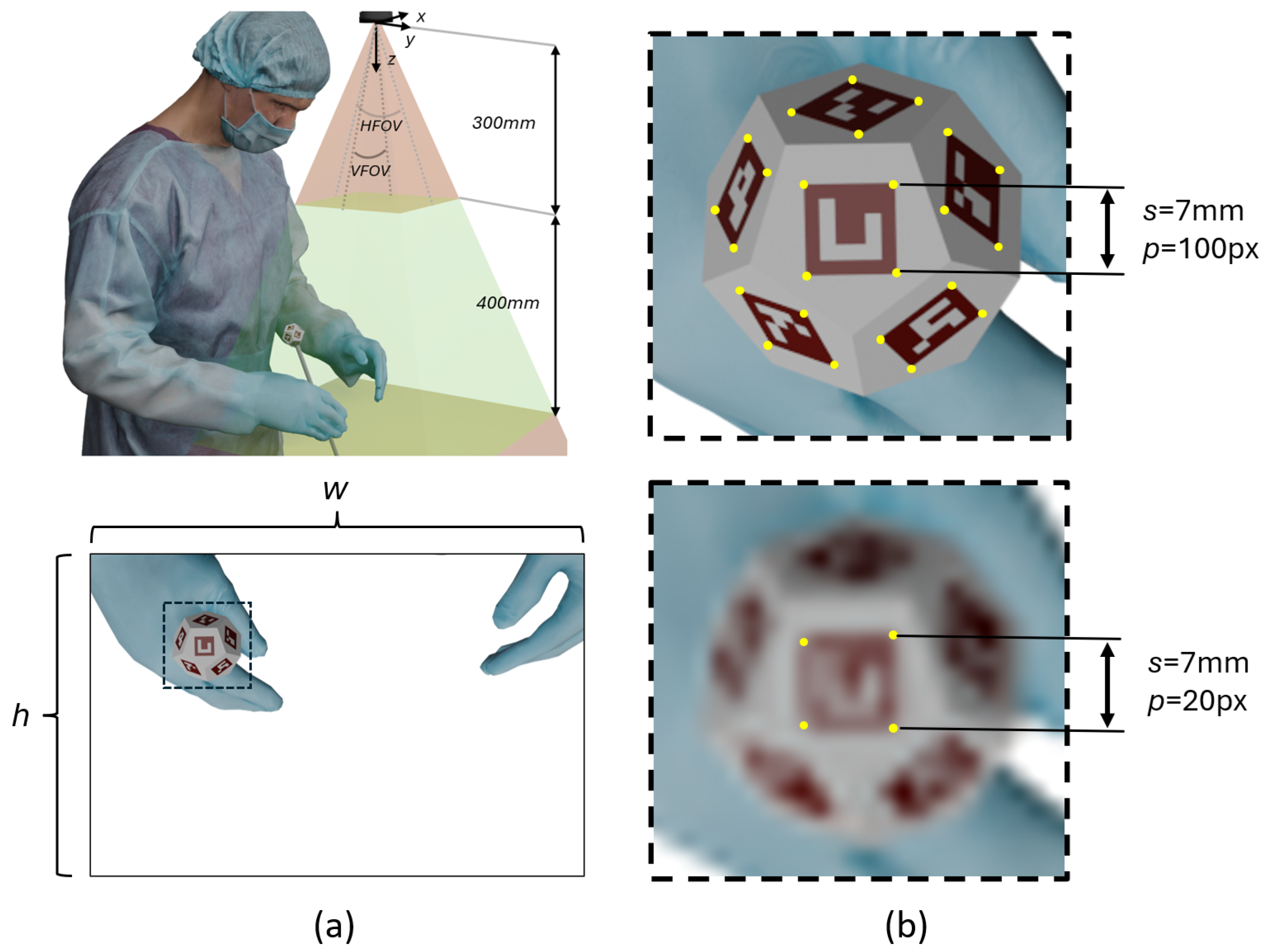

2.1.1. Optical System Setup

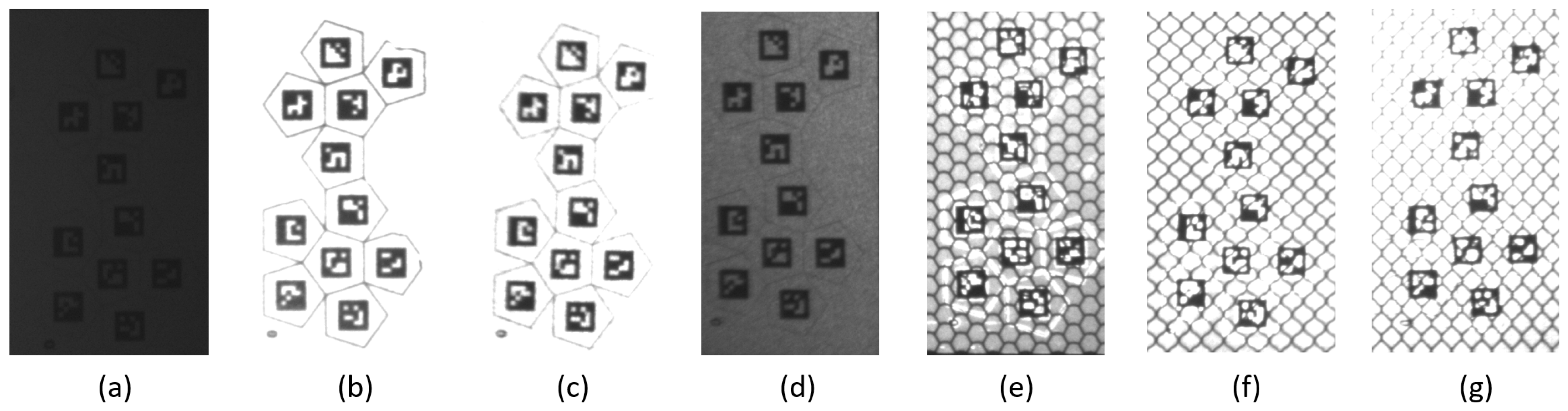

2.1.2. Marker Design

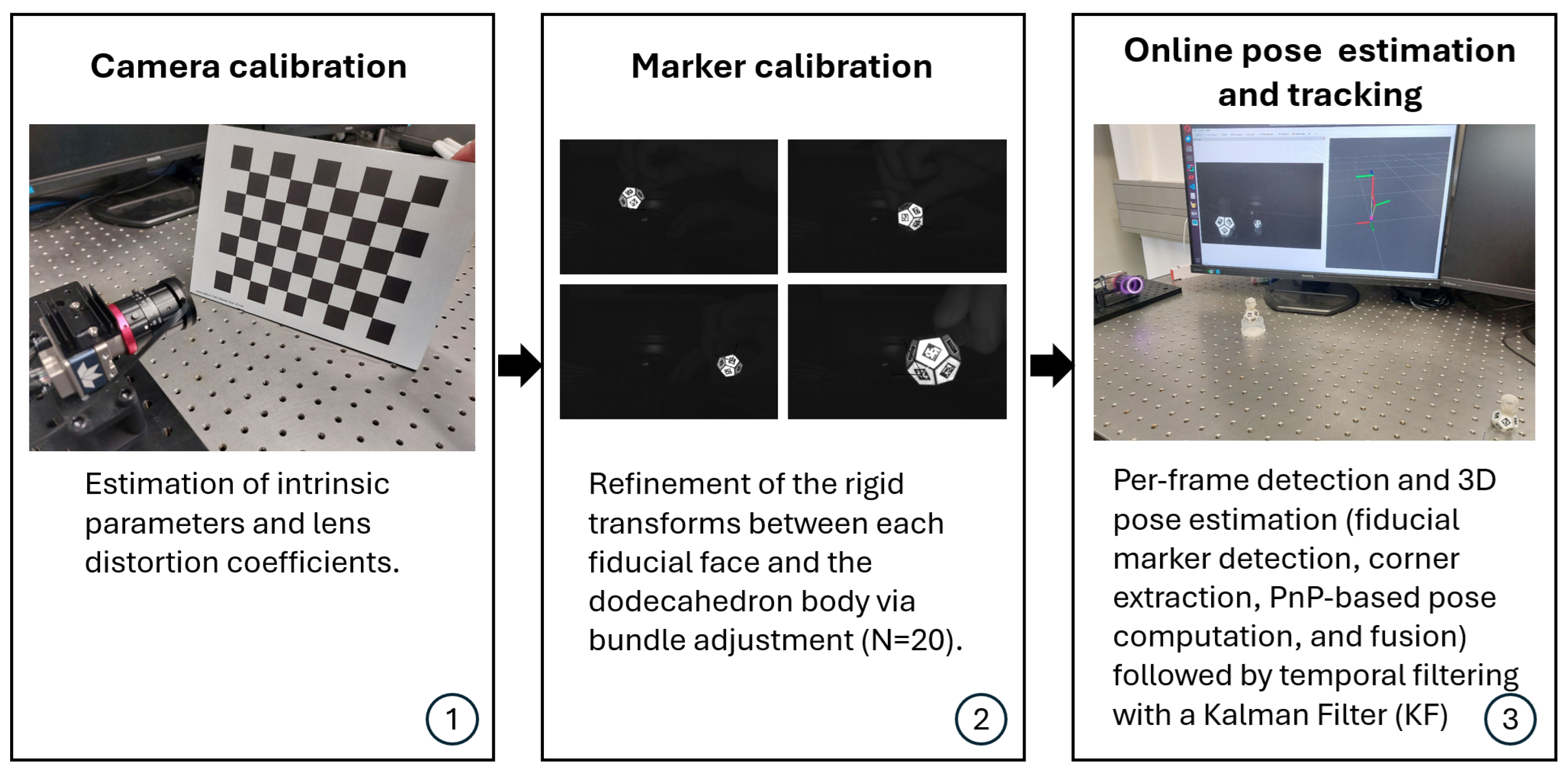

2.2. Algorithm

2.2.1. Camera Calibration

2.2.2. Marker Calibration

- The 3D positions of the markers relative to the dodecahedron.

- The 6-DOF poses of the dodecahedron for each camera frame.

2.2.3. Per-Frame Detection and 3D Pose Estimation

3. Results

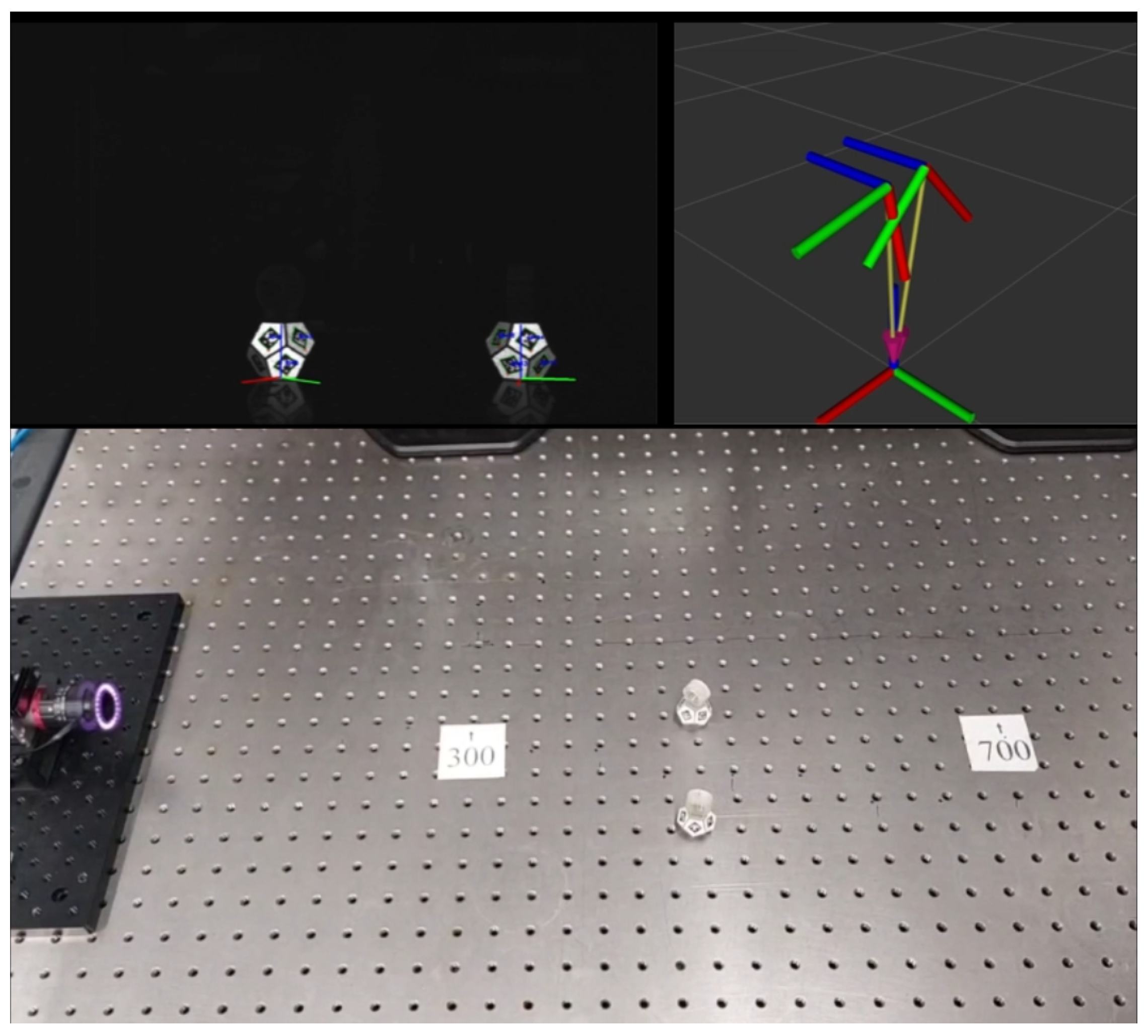

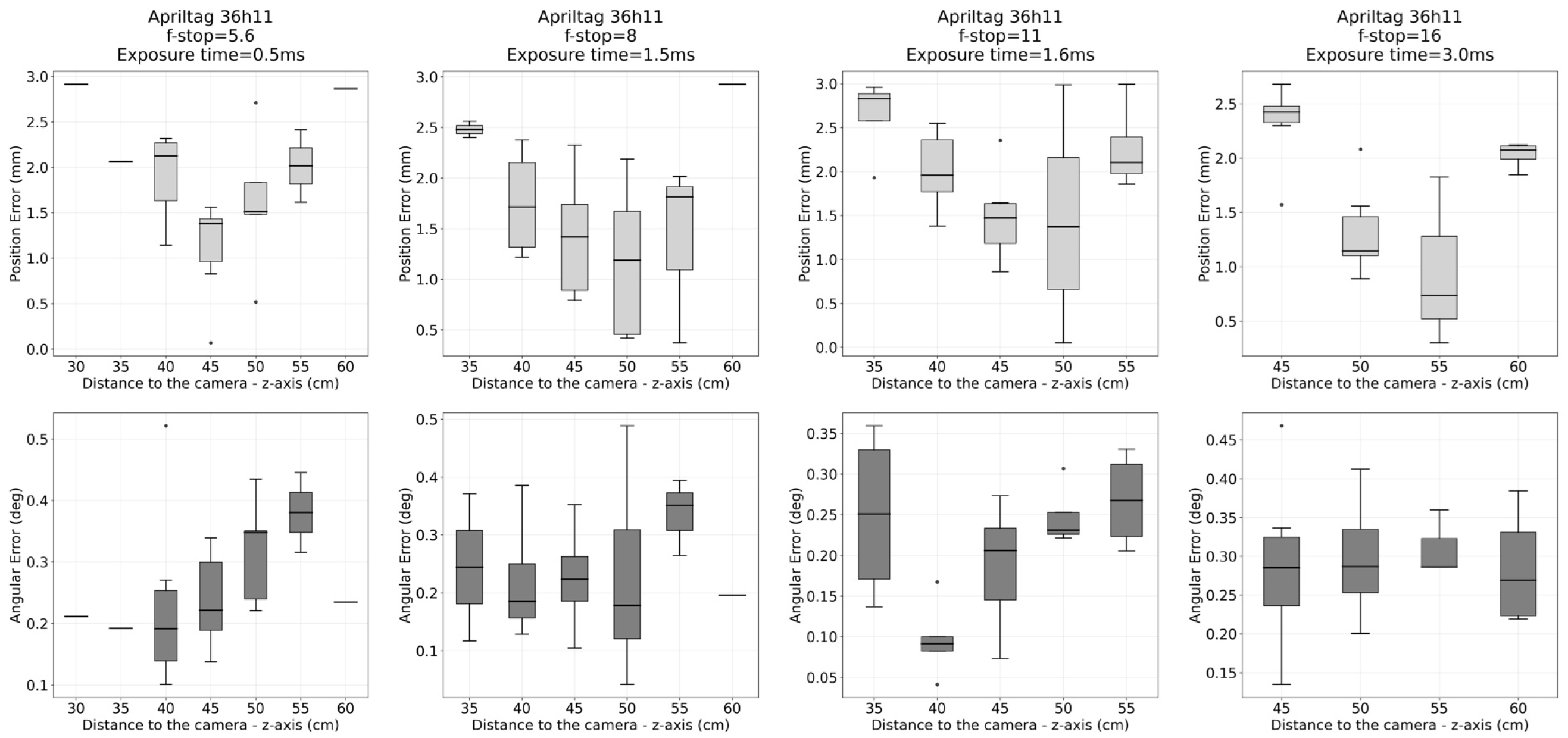

3.1. Evaluation of Accuracy and Precision in Static Positions

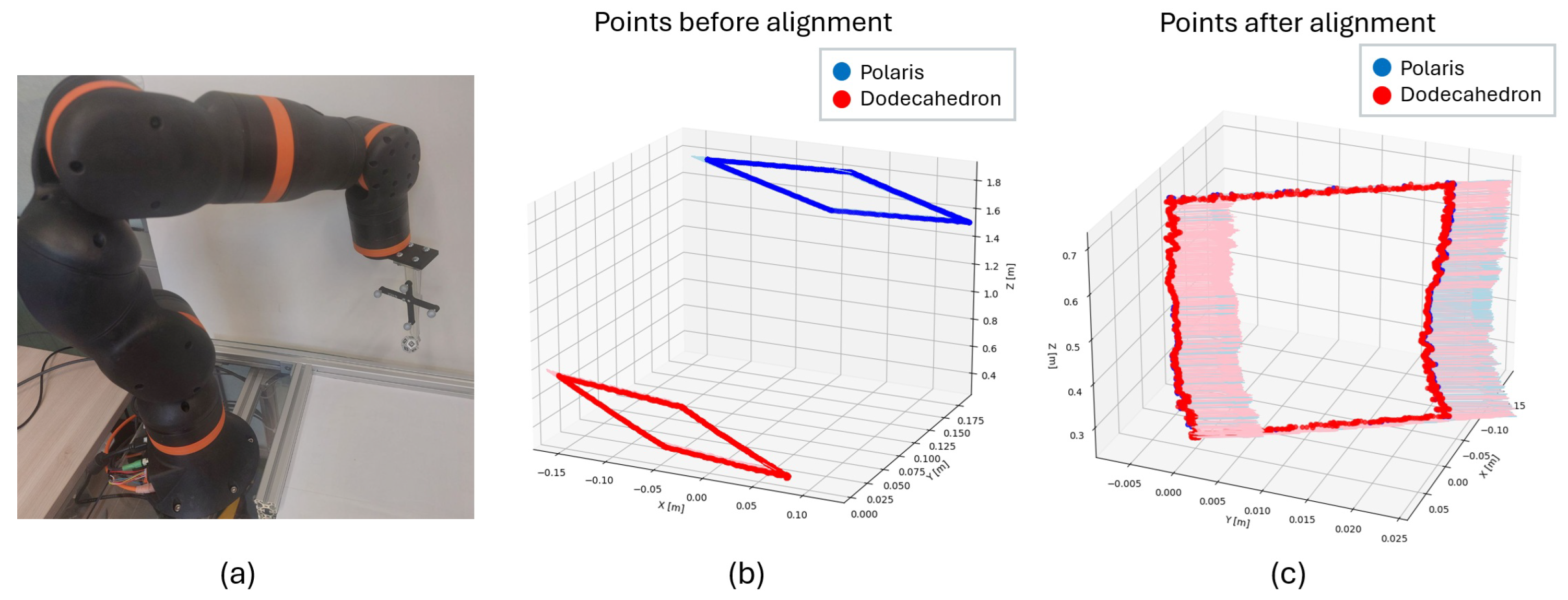

3.2. Evaluation of Accuracy and Precision in Dynamic Positions

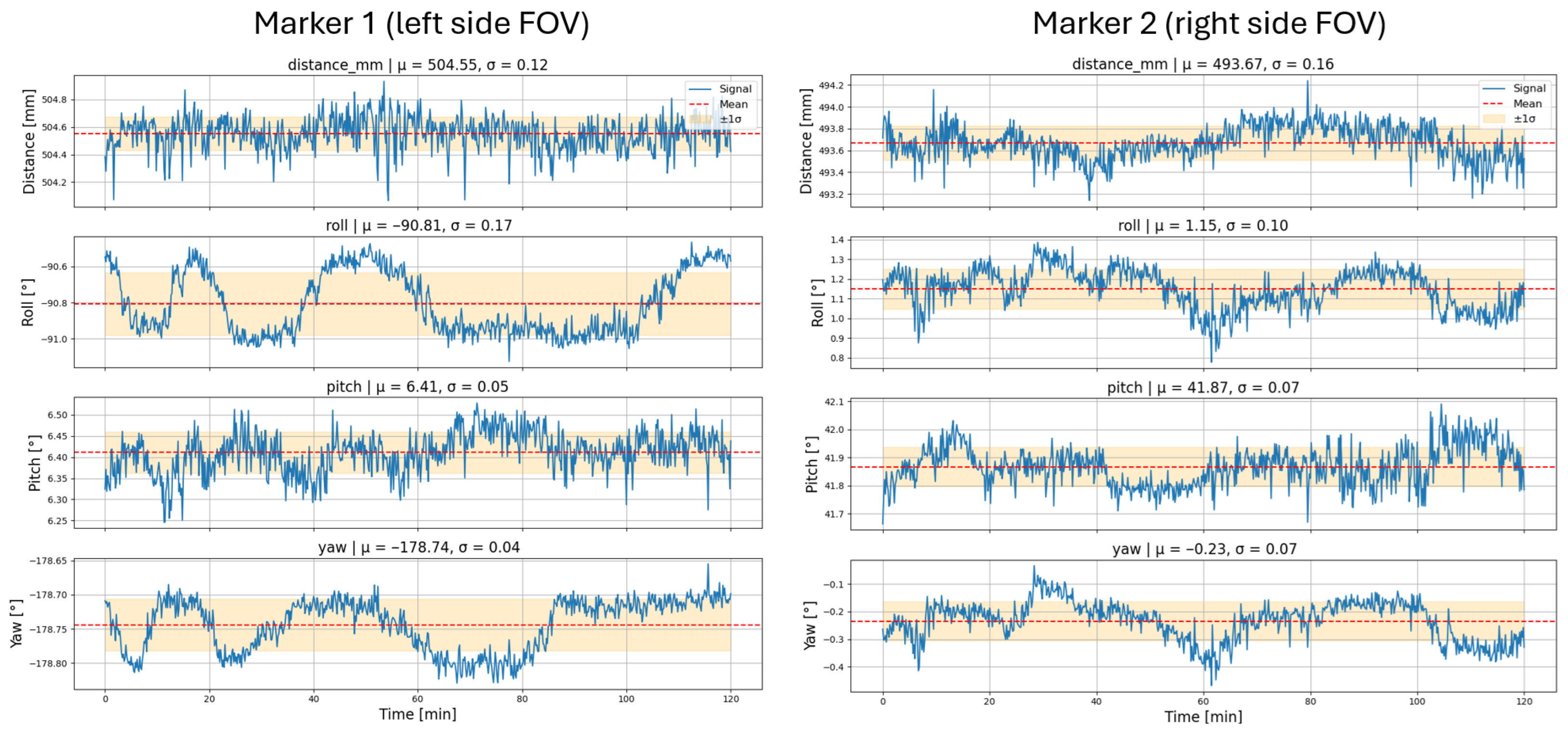

3.3. System Stability over Extended Operation Time

3.4. Latency

- : Image capture latency.

- : Data transfer latency.

- : Computational latency for detection and pose estimation.

- : Application latency.

3.5. Sterility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BA | Bundle Adjustment |

| BOP | Benchmark for 6D Object Pose Estimation |

| CoC | Circle of Confusion |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| DoF | Depth of Field |

| EMTS | Electromagnetic Tracking Systems |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HFOV | Horizontal Field of View |

| ICP | Iterative Closest Point |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IR | Infrared |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| OR | Operating Room |

| OTS | Optical Tracking Systems |

| PnP | Perspective-n-Point |

| RA | Retroreflective Adhesive |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| ROS2 | Robot Operating System 2 |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| UWB | Ultra-Wideband |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| US | Ultrasound |

| VFOV | Vertical Field of View |

| VIS | Visible |

| 5G | 5th Generation mobile networks |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| aruco_dictionary_id | DICT_ARUCO_MIP_36h12 |

| adaptiveThreshWinSizeMin | 3 |

| adaptiveThreshWinSizeMax | 60 |

| adaptiveThreshWinSizeStep | 10 |

| adaptiveThreshConstant | 7 |

| minMarkerPerimeterRate | 0.02 |

| maxMarkerPerimeterRate | 4.0 |

| polygonalApproxAccuracyRate | 0.03 |

| minCornerDistanceRate | 0.05 |

| minDistanceToBorder | 3 |

| minMarkerDistanceRate | 0.02 |

| cornerRefinementMethod | CORNER_REFINE_CONTOUR |

| cornerRefinementWinSize | 7 |

| cornerRefinementMaxIterations | 100 |

| cornerRefinementMinAccuracy | |

| markerBorderBits | 1 |

| perspectiveRemovePixelPerCell | 16 |

| perspectiveRemoveIgnoredMarginPerCell | 0.13 |

| maxErroneousBitsInBorderRate | 0.4 |

| minOtsuStdDev | 5.0 |

| errorCorrectionRate | 0.6 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| tag_family | tag36h11 |

| quad_decimate | 1.5 |

| quad_sigma | 0.0 |

| nthreads | 4 |

| refine_edges | true |

| decode_sharpening | 0.1 |

| debug | false |

| critical_rad | 0.785 |

| max_line_fit_mse | 10.0 |

| min_white_black_diff | 40 |

References

- Fitzpatrick, J.M. The role of registration in accurate surgical guidance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2010, 224, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Deng, Z.; Shen, N.; He, Z.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Yao, J. A fully automatic surgical registration method for percutaneous abdominal puncture surgical navigation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, P.; Simon, R.; Linte, C.A. Surgical Tracking, Registration, and Navigation Characterization for Image-guided Renal Interventions. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 5081–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, C.; Whitaker, J.; Nyland, J.; Roberts, C.; Carlson, J.; Zamora, R. Skin fiducial markers enable accurate computerized navigation resection of simulated soft tissue tumors: A static cadaveric model pilot study. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 118, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kapoor, A.; Mansi, T.; Kamen, A. A Wide-Area, Low-Latency, and Power-Efficient 6-DoF Pose Tracking System for Rigid Objects. IEEE Sensors J. 2022, 22, 4558–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorriento, A.; Porfido, M.B.; Mazzoleni, S.; Calvosa, G.; Tenucci, M.; Ciuti, G.; Dario, P. Optical and Electromagnetic Tracking Systems for Biomedical Applications: A Critical Review on Potentialities and Limitations. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 13, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NDI Inc., Waterloo, ON, Canada. Polaris Vega: Advanced Optical Navigation for OEMs. 2023. Available online: https://www.ndigital.com/optical-navigation-technology/polaris-vega/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- NaturalPoint, Inc. OptiTrack: Motion Capture Systems. 2025. Available online: https://www.optitrack.com/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada. Navient Surgical Navigation System. 2024. Available online: https://medical.claronav.com/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- BOP: Benchmark for 6D Object Pose Estimation. 2025. Available online: https://bop.felk.cvut.cz/home/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Romero-Ramirez, F.J.; Muñoz-Salinas, R.; Medina-Carnicer, R. Speeded up detection of squared fiducial markers. Image Vis. Comput. 2018, 76, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogius, M.; Haggenmiller, A.; Olson, E. Flexible Layouts for Fiducial Tags. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 1898–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, P.; Romero-Ramirez, F.J.; Muñoz-Salinas, R.; Marín-Jiménez, M.J.; Medina-Carnicer, R. Fiducial Objects: Custom Design and Evaluation. Sensors 2023, 23, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.C.; Xu, R.; Lee, G.H.; Chou, P.H.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chen, B.Y. DodecaPen: Accurate 6DoF Tracking of a Passive Stylus. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST’17), New York, NY, USA, 22–25 October 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, M.; Padhan, J.; Navkar, N.V.; Deng, Z. Preliminary Design and Evaluation of an Interfacing Mechanism for Maneuvering Virtual Minimally Invasive Surgical Instruments. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR), Atlanta, GA, USA, 13–15 April 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalerud, A.; Dybedal, J.; Hovland, G. Automatic Calibration of an Industrial RGB-D Camera Network Using Retroreflective Fiducial Markers. Sensors 2019, 19, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Surgical Technologists. Guidelines for Best Practices for Establishing the Sterile Field in the Operating Room; Association of Surgical Technologists: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2019; pp. 218–226. Available online: https://www.ast.org/uploadedFiles/Main_Site/Content/About_Us/Guidelines%20Establishing%20the%20Sterile%20Field.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Moviglia, J.; Dittmann, M.; Stallkamp, J. Proof of Concept of a Novel Tracking System with a Monocular Camera for Image-Guided Surgery Navigation. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the 58th Annual Meeting of the German Society for Biomedical Engineering, Stuttgart, Germany, 18–20 September 2024; p. 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. A flexible new technique for camera calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepon, G.; Ocepek, D.; Kodrič, M.; Demšar, M.; Bregar, T.; Boltežar, M. Impact-Pose Estimation Using ArUco Markers in Structural Dynamics. Exp. Tech. 2024, 48, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Rodriguez, D.; Muñoz-Salinas, R.; Garrido-Jurado, S.; Medina-Carnicer, R. Planar fiducial markers: A comparative study. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDI Inc. Polaris Vega®VT: Technical Specifications of the Optical Tracker. In NDI Product Specification Sheet; NDI Inc.: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, A.M.; Haidegger, T.; Birkfellner, W.; Cleary, K.; Peters, T.M.; Maier-Hein, L. Electromagnetic Tracking in Medicine—A Review of Technology, Validation, and Applications. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2014, 33, 1702–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Zhu, T.S.; Downes, T.; Cheng, L.; Kass, N.M.; Andrews, E.G.; Biehl, J.T. Understanding Effects of Visual Feedback Delay in AR on Fine Motor Surgical Tasks. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 29, 4697–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Feature | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Camera | Type | NIR, Monochromatic |

| Sensor size | 9.22 × 5.76 mm | |

| Exposure Time | <4 ms | |

| Resolution | 1920 × 1200 | |

| FPS | 80 | |

| Analog Gain | 0 dB | |

| Lens | Focal Length | 16 mm |

| f-stop | 5.6, 8, 11, 16 | |

| Light | Wavelength | 875 nm |

| Power | 2 × 3 W | |

| Type | Directional Ring |

| Image | Material | Technology | Category (RA) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | White and black | Not retroreflective | - | - |

| (b) | Orafol ORALITE 5710 | Glass Beads | RA1 | A |

| (c) | 3M™ Scotchlite™ 8906 | Glass Beads | RA1 | A |

| (d) | Orafol ORALITE 5600E | Glass Beads | RA1 | A |

| (e) | Orafol ORALITE 5910 | Microprismatic | RA2 | B |

| (f) | Orafol ORALITE 6910 | Full-cube microprismatic | RA3 | C |

| (g) | 3M™ Scotchlite™ 4090 | Full-cube microprismatic | RA3 | C |

| F-Stop = 5.6 Exp. Time = 0.5 ms | F-Stop = 8 Exp. Time = 1.5 ms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ArUco | AprilTag | ArUco | AprilTag | |

| Translational RMS (mm) | 0.438 | 1.872 | 1.559 | 1.772 |

| Std. Dev. (mm) | 0.195 | 0.712 | 0.667 | 0.744 |

| Angular RMS (deg) | 0.349 | 0.285 | 0.330 | 0.269 |

| Std. Dev. (deg) | 0.157 | 0.106 | 0.152 | 0.116 |

| F-Stop = 11 Exp. Time = 1.6 ms | F-Stop = 16 Exp. Time = 3.0 ms | |||

| ArUco | AprilTag | ArUco | AprilTag | |

| Translational RMS (mm) | 0.831 | 2.070 | 0.503 | 1.846 |

| Std. Dev. (mm) | 0.398 | 0.754 | 0.213 | 0.656 |

| Angular RMS (deg) | 0.290 | 0.221 | 0.327 | 0.304 |

| Std. Dev. (deg) | 0.140 | 0.088 | 0.156 | 0.078 |

| Configuration | ArUco | AprilTag | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Latency (ms) | Proc. Latency (ms) | Total Latency (ms) | Proc. Latency (ms) | |

| F-stop = 5.6, | ||||

| Exp. Time = 0.5 ms | 31.95 ± 8.31 | 10.08 ± 3.84 | 24.40 ± 3.17 | 4.76 ± 1.13 |

| F-stop = 8, | ||||

| Exp. Time = 1.5 ms | 30.28 ± 7.29 | 9.50 ± 3.27 | 22.75 ± 4.41 | 5.10 ± 1.32 |

| F-stop = 11, | ||||

| Exp. Time = 1.6 ms | 33.06 ± 7.87 | 9.90 ± 2.66 | 26.03 ± 3.08 | 4.55 ± 0.77 |

| F-stop = 16, | ||||

| Exp. Time = 3 ms | 30.83 ± 4.58 | 9.83 ± 1.83 | 24.07 ± 3.37 | 5.03 ± 1.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moviglia, J.H.; Stallkamp, J. Monocular Near-Infrared Optical Tracking with Retroreflective Fiducial Markers for High-Accuracy Image-Guided Surgery. Sensors 2026, 26, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020357

Moviglia JH, Stallkamp J. Monocular Near-Infrared Optical Tracking with Retroreflective Fiducial Markers for High-Accuracy Image-Guided Surgery. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020357

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoviglia, Javier Hernán, and Jan Stallkamp. 2026. "Monocular Near-Infrared Optical Tracking with Retroreflective Fiducial Markers for High-Accuracy Image-Guided Surgery" Sensors 26, no. 2: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020357

APA StyleMoviglia, J. H., & Stallkamp, J. (2026). Monocular Near-Infrared Optical Tracking with Retroreflective Fiducial Markers for High-Accuracy Image-Guided Surgery. Sensors, 26(2), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020357