HMT-Net: A Multi-Task Learning Based Framework for Enhanced Convolutional Code Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Novel Hybrid Architecture Design: We propose a feature extraction module integrating DCA and CWT. This structure expands the receptive field to capture global features under low SNR conditions while utilizing channel-wise attention to isolate task-specific features for code rate and constraint length recognition.

- Dataset Enhancement Strategy: We construct a comprehensive sequence dataset incorporating statistical features. This enhancement significantly improves the model’s discriminative power and robustness against channel noise.

- Performance Advantages: HMT-Net can recognize a broader set of convolutional code parameters, covering high code rates and approximately constrained lengths. Experimental results demonstrate that this model outperforms multiple state-of-the-art signal recognition frameworks in terms of recognition accuracy.

2. System Model

2.1. Digital Communication System

2.2. Multi-Task Recognition System

3. Proposed Approach

3.1. HMT-Net

3.1.1. Data Preprocessing Module

3.1.2. Shared Feature Module

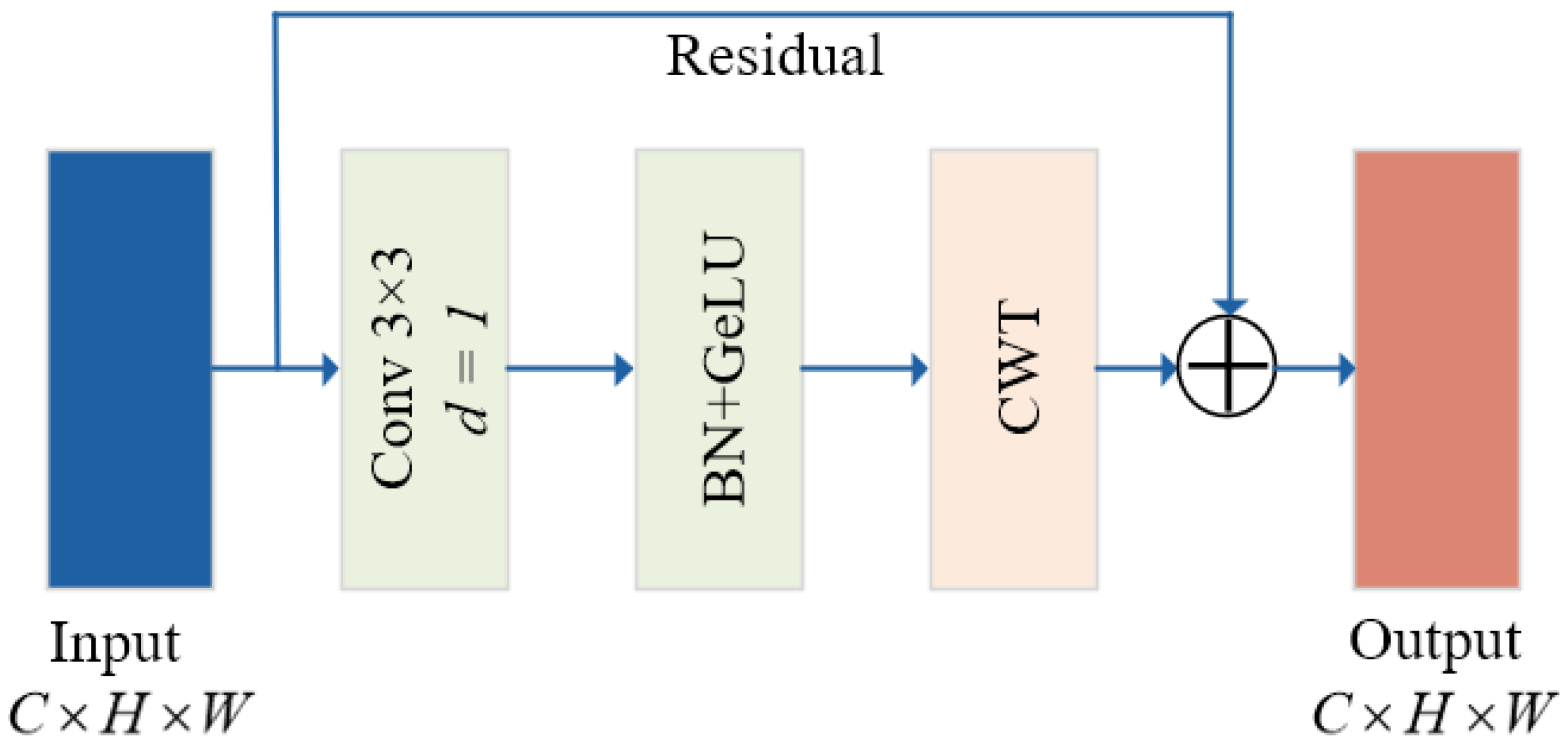

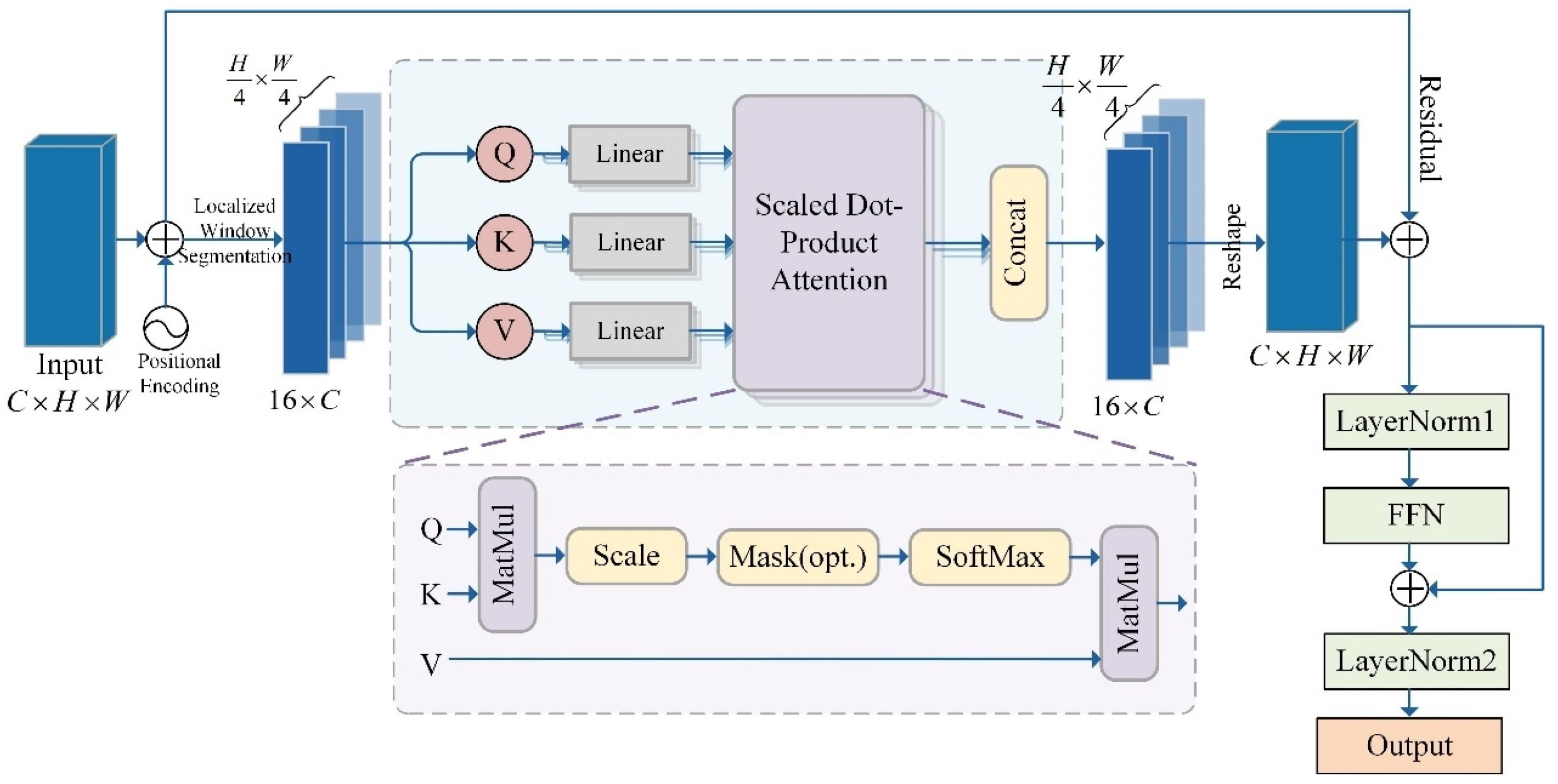

3.1.3. Task-Specific Modules

3.1.4. Dynamic Weight Adjustment

3.1.5. HMT-Net Parameterization

3.2. Data Processing

- Generate a binary random sequence m, with length of 300 bit.

- The corresponding convolutional encoding is performed according to the parameters specified in Table 1.

- BPSK modulation is used to modulate the coded sequence to generate the modulated signal s.

- Addition of AWGN produces a noisy signal and simulates the effect of channel transmission .

- The channel is demodulated to obtain a soft verdict affected by interference .

- From the first 0 to 20 digits of the sequence, one of them is randomly selected as the starting point, and 256 bits are extracted as the sample sequence r, and the label is added to it at the same time.

- Repeat steps 1–6 to generate the complete dataset, as formulated in Equation (13).

4. Experimental Results

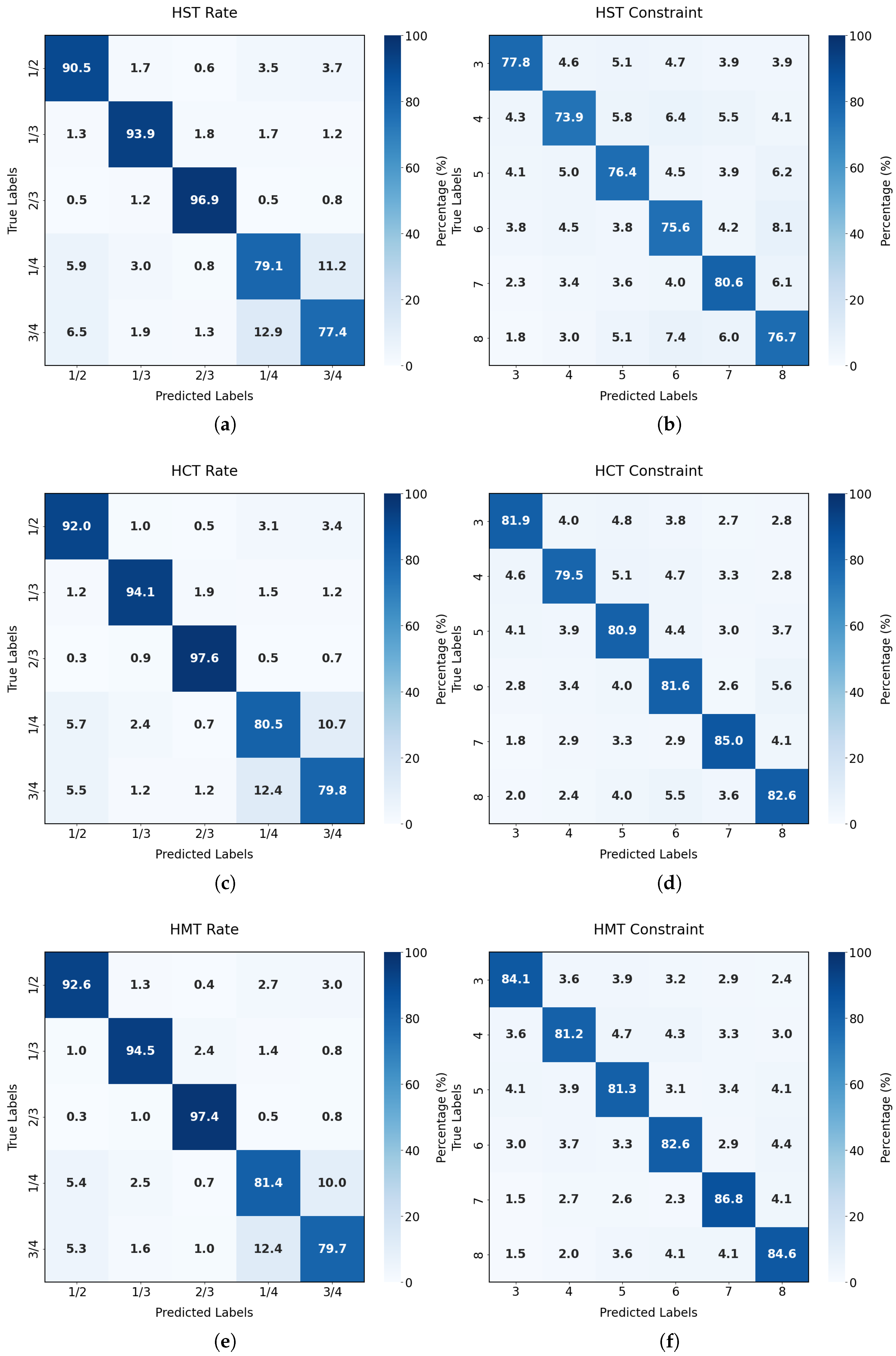

4.1. Multi-Task Effectiveness Analysis

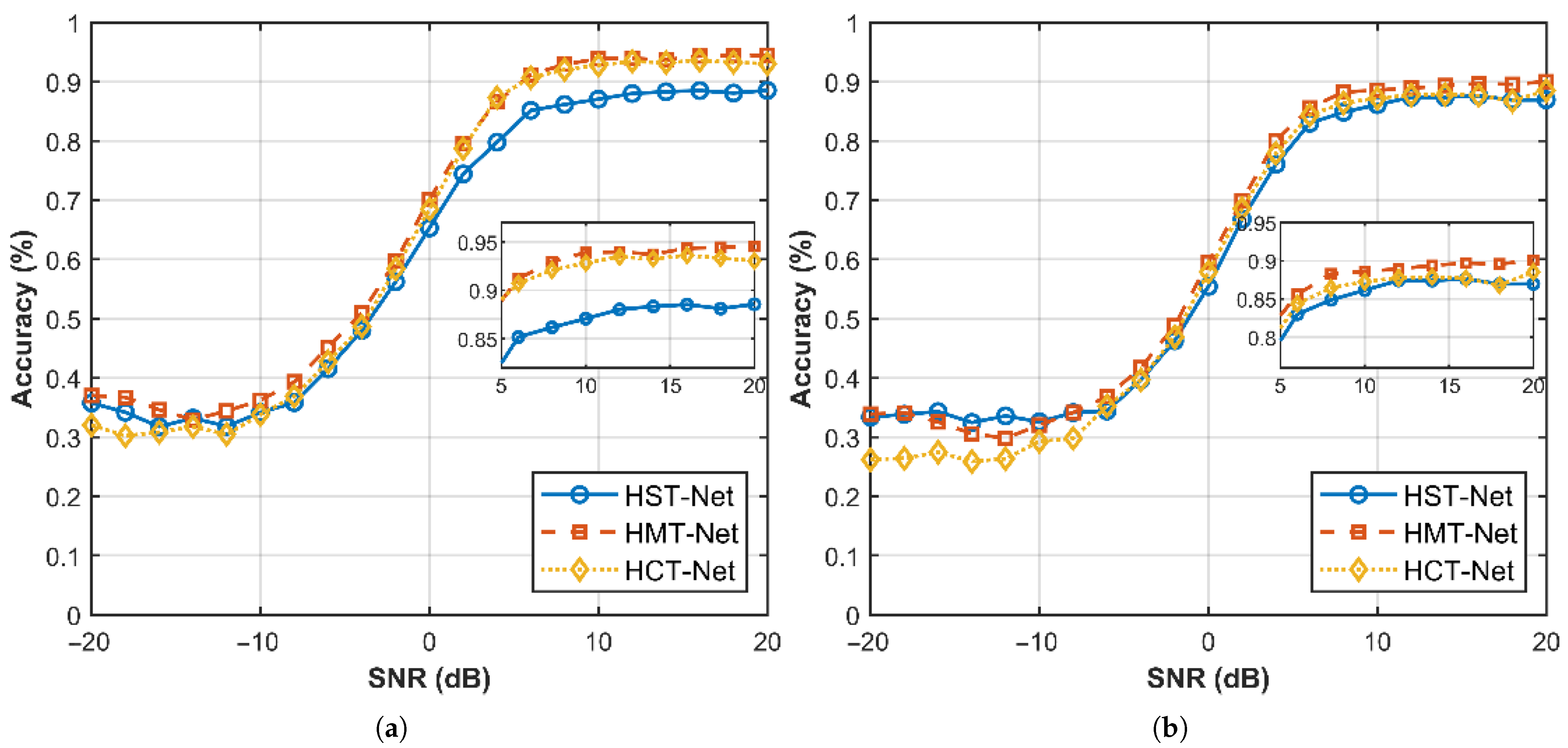

4.2. Performance Analysis of Multiple Networks

4.3. Effectiveness of Dynamic Loss Weighting Modules

4.4. Effect of Different Datasets on Recognition Performance

4.5. Ablation Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rice, B. Determining the parameters of a rate 1/n convolutional encoder over GF(q). In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Finite Fields and Applications, Glasgow, UK, 11–14 July 1995; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Filiol, E. Reconstruction of Convolutional Encoders over GF(q). In Proceedings of the 6th IMA International Conference on Cryptography and Coding, Cirencester, UK, 17–19 December 1997; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X. Blind recognition of convolutional coding based on Walsh-Hadamard transform. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2010, 32, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, G. Blind Recognition of (n-1)/n Rate Punctured Convolutional Encoders in a Noisy Environment. J. Commun. 2015, 10, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Peng, S.; Yang, X.; Yao, Y. Deep learning based channel code recognition using TextCNN. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks (DySPAN), Newark, NJ, USA, 11–14 November 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Tang, C.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Blind identification of convolutional codes based on deep learning. Digit. Signal Process. 2021, 115, 103086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Wang, J.; Li, J. A deep convolutional learning method for blind recognition of channel codes. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1621, 012088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdashtian, S.; Hashemi, M.; Salehkaleybar, S. Deep-Learning-Based Blind Recognition of Channel Code Parameters Over Candidate Sets Under AWGN and Multi-Path Fading Conditions. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2021, 10, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yan, C.; Ma, Y.; He, Y. Recognition of Punctured Convolutional Codes Based on Multi-scale CNN. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Hong Kong, China, 10–13 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gui, G.; Ohtsuki, T.; Adachi, F. Multi-task learning for generalized automatic modulation classification under non-Gaussian noise with varying SNR conditions. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 3587–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, A.; Jagannath, J. Multi-task learning approach for modulation and wireless signal classification for 5G and beyond: Edge deployment via model compression. Phys. Commun. 2022, 54, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F. Blind Channel Estimation and Data Detection With Unknown Modulation and Coding Scheme. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 72, 2595–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Peng, X.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Yang, X. Channel-Robust RF Fingerprint Identification using Multi-Task Learning and Receiver Collaboration. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 31, 2510–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagduyu, Y.E.; Erpek, T.; Yener, A.; Ulukus, S. Joint sensing and semantic communications with multi-task deep learning. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2024, 62, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Hu, T.; Gong, H.; Yang, S. Blind identification of space-time block code based on bp neural networks. J. Signal Process. 2022, 38, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Peng, S. Recognition of channel codes based on BiLSTM-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2022 31st Wireless and Optical Communications Conference (WOCC), Shenzhen, China, 11–12 August 2022; pp. 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, T.T.; Noh, D.I.; Pham, Q.V.; Hasegawa, M.; Sekiya, H.; Hwang, W.-J. VT-MCNet: High-accuracy automatic modulation classification model based on vision transformer. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2023, 28, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, K.A.; Heymann, R.; Swart, T.G. Attention turbo-autoencoder for improved channel coding and reconstruction. J. Commun. 2024, 19, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Luo, H.; Yu, T.; Mi, Q.; Xu, L. Blind Recognition of Channel Coding Schemes Based on Foundation Models and CNNs. In Proceedings of the 2025 10th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 16–18 May 2025; pp. 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H.; Cai, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, B.; Huang, J.; Hua, X.S.; Zhao, M.J. Improving 3D object detection with channel-wise transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2743–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, S. DCA-SSeqNet: Enhanced IMU Dead Reckoning via Dilated Channel-Attention. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Communications and Intelligent Science (ECIS), Beijing, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, J.C.; Farrell, P.G. Essentials of Error-Control Coding; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Haque, A.; Huang, D.A.; Yeung, S.; Li, F.-F. Dynamic task prioritization for multitask learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 270–287. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S. Research on Application of Multi-task Learning in Channel Coding Parameters Recognition. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, S.; Huang, S.; Chang, S.; He, J.; Feng, Z. AMSCN: A novel dual-task model for automatic modulation classification and specific emitter Identification. Sensors 2023, 23, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, M.; Fan, X. Deep joint source-channel coding for multi-task network. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 1973–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ma, Y.; Shi, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Blind Recognition of Convolutional Codes Based on the ConvLSTM Temporal Feature Network. Sensors 2025, 25, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module | Network Layer | Parameters | Output Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input: coded signal (dimension: ) | |||

| Preproc- essing | Conv | Conv(3 × 3, 64), BN, GELU, MaxPool(2) | 64 × 16 × 16 |

| Feature sharing module (in software) | CT-Block 1 | Conv(3 × 3, 64) + CWT(64) | 64 × 16 × 16 |

| DCA-Block 1 | 64-channel convolution with attention mechanism | 64 × 16 × 16 | |

| CT-Block 2 | Conv(3 × 3, 64) + CWT(64) | 64 × 16 × 16 | |

| DCA-Block 2 | 64-channel convolution with attention mechanism | 64 × 16 × 16 | |

| Mission- specific module (in software) | CT-Block 3 | Conv(3 × 3, 64) + CWT(64) | 64 × 16 × 16 |

| CWT-Block | 64-channel, 4-head self- attention mechanism | 64 × 16 × 16 | |

| Global average pooling | (1 × 1) | 64 × 1 | |

| FC 1 | [64 → 256] + GELU activation | 256 × 1 | |

| FC 2 | [256 → K] + Softmax | K × 1 | |

| Output: subtask () prediction class probability vector (dimension: ) | |||

| Dynamic weighting | task weight parameter | Learnable parameters EMA update factor | N × 1 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Initial learning rate | 0.001 |

| Training cycle | 60 |

| Learning Rate Scheduler | ReduceLROnPlateau |

| Batch size | 64 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Classification of Tasks | Code Rate | Constraint Length |

|---|---|---|

| Convolutional code |

| Model | Code Rate Recognition Accuracy | Constraint Length Recognition Accuracy | Average Recognition Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| HST-Net | 62.01% | 59.21% | 60.61% |

| HCT-Net | 64.42% | 57.83% | 61.13% |

| HMT-Net | 66.31% | 60.68% | 63.50% |

| Task | Class | Per-Class Accuracy (Recall) | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code Rate | 1/2 | 92.60% | 90.52% |

| 1/3 | 94.41% | 94.03% | |

| 2/3 | 97.40% | 96.48% | |

| 1/4 | 81.40% | 82.06% | |

| 3/4 | 79.70% | 82.04% | |

| Macro-Avg | 89.10% | 89.03% | |

| Constraint Length | K = 3 | 84.02% | 84.99% |

| K = 4 | 81.12% | 82.35% | |

| K = 5 | 81.38% | 81.59% | |

| K = 6 | 82.68% | 82.81% | |

| K = 7 | 86.80% | 85.35% | |

| K = 8 | 84.68% | 83.56% | |

| Macro-Avg | 83.45% | 83.44% | |

| Note: The bold text indicates the macro-average performance across all classes. | |||

| Methodologies | Task | Parameter Quantification | Inference Time | FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HST-Net | Code rate | 304.02 K | 5.73 ms | 18.4 MFLOPs |

| Constraint length | 304.27 K | 5.84 ms | 18.4 MFLOPs | |

| HCT-Net | Combined | 612.15 K | 11.08 ms | 36.7 MFLOPs |

| HMT-Net | Combined | 385.16 K | 6.94 ms | 22.5 MFLOPs |

| Model | Code Rate Recognition | Constraint Length Recognition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNR ∈ [0, 20] | SNR ∈ [−20, 20] | SNR ∈ [0, 20] | SNR ∈ [−20, 20] | |

| MAR-Net [26] | 93.16% | 61.74% | 86.21% | 56.37% |

| AMSCN [27] | 87.84% | 59.98% | 84.93% | 56.20% |

| FFMNet [28] | 72.38% | 51.05% | 51.81% | 37.58% |

| ConvLSTM-TFN [29] | 86.60% | 59.58% | 78.15% | 53.62% |

| HMT-Net | 95.01% | 66.31% | 88.05% | 60.68% |

| (1.85%) | (4.57%) | (1.84%) | (4.31%) | |

| Recognition Accuracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Code Rate | Constraint Length | ||

| 0.1 | 0.9 | 30.19% | 59.53% |

| 0.2 | 0.8 | 59.73% | 59.33% |

| 0.3 | 0.7 | 64.82% | 59.61% |

| 0.4 | 0.6 | 65.77% | 59.74% |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 65.39% | 58.87% |

| 0.6 | 0.4 | 64.83% | 57.82% |

| 0.7 | 0.3 | 64.97% | 53.77% |

| 0.8 | 0.2 | 63.89% | 42.48% |

| 0.9 | 0.1 | 63.21% | 24.31% |

| EMA | 66.31% | 60.68% | |

| Module | Backbone | DCA | CT | CWT | Recognition Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | Constraint Length | |||||

| Baseline 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 63.46% | 58.26% | |

| Baseline 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 58.93% | 52.29% | |

| Baseline 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 60.08% | 55.52% | |

| HMT-Net | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 66.31% | 60.68% |

| Note: ✓ indicates that the module is included; bold text indicates the best performance. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, R.; Jia, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. HMT-Net: A Multi-Task Learning Based Framework for Enhanced Convolutional Code Recognition. Sensors 2026, 26, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020364

Xu L, Chen X, Ma Y, Shi R, Jia R, Zhang L, Zhang Y. HMT-Net: A Multi-Task Learning Based Framework for Enhanced Convolutional Code Recognition. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020364

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Lu, Xu Chen, Yixin Ma, Rui Shi, Ruiwu Jia, Lingbo Zhang, and Yijia Zhang. 2026. "HMT-Net: A Multi-Task Learning Based Framework for Enhanced Convolutional Code Recognition" Sensors 26, no. 2: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020364

APA StyleXu, L., Chen, X., Ma, Y., Shi, R., Jia, R., Zhang, L., & Zhang, Y. (2026). HMT-Net: A Multi-Task Learning Based Framework for Enhanced Convolutional Code Recognition. Sensors, 26(2), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020364