High-Efficiency Traceability Mechanism for Multimedia Data in Consumer Internet of Things Combined with Blockchain

Abstract

1. Introduction

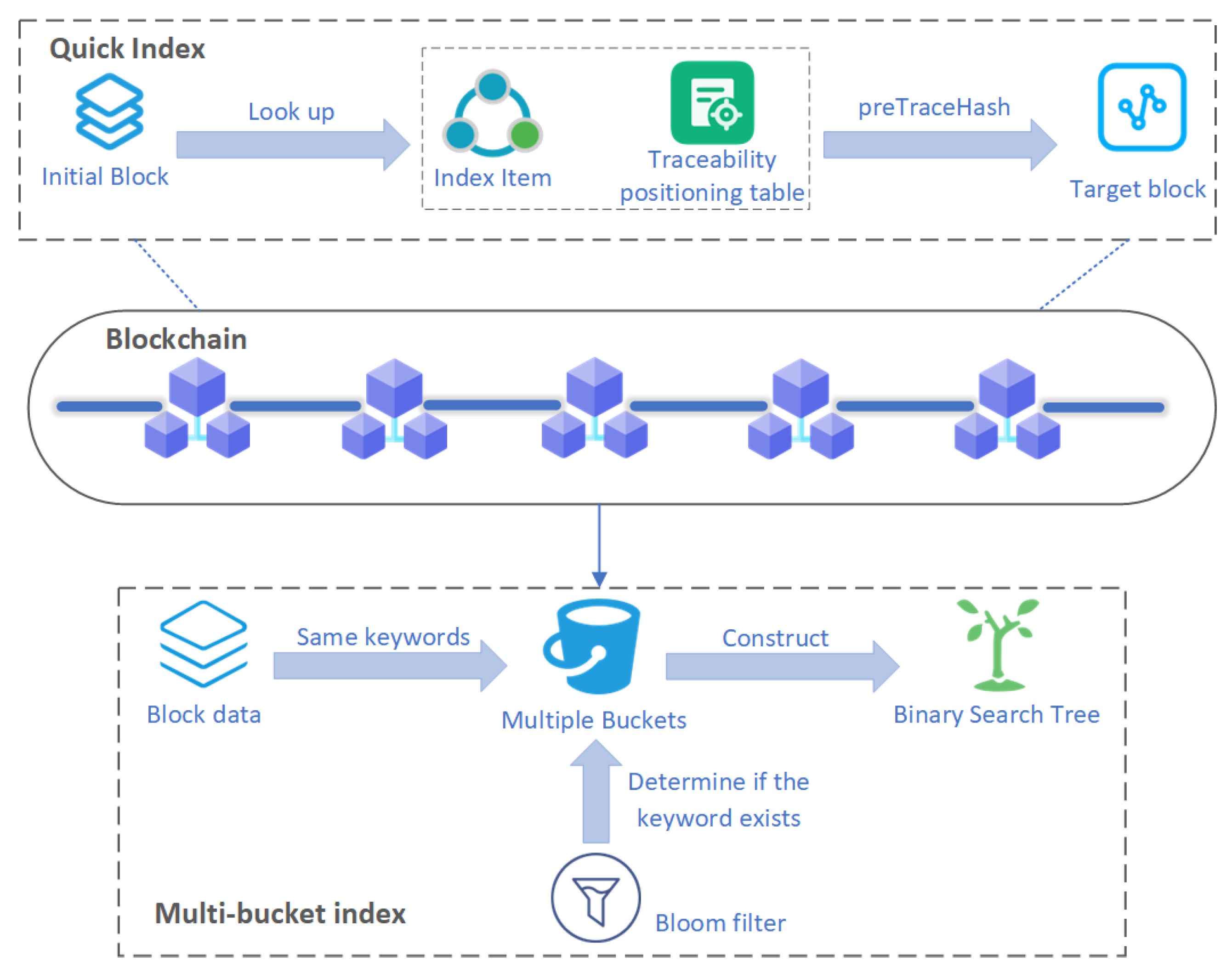

- A novel efficient blockchain-based multimedia data security traceability mechanism suitable for CIoT environments is proposed. This mechanism combines blockchain technology with the PROV model to ensure standardized recording of data operations and the credibility of data sources. A joint index structure, including fast indexing and multi-bucket indexing, is utilized to accelerate traceability queries while avoiding the introduction of external databases, improving data query efficiency, and maintaining blockchain security and transparency.

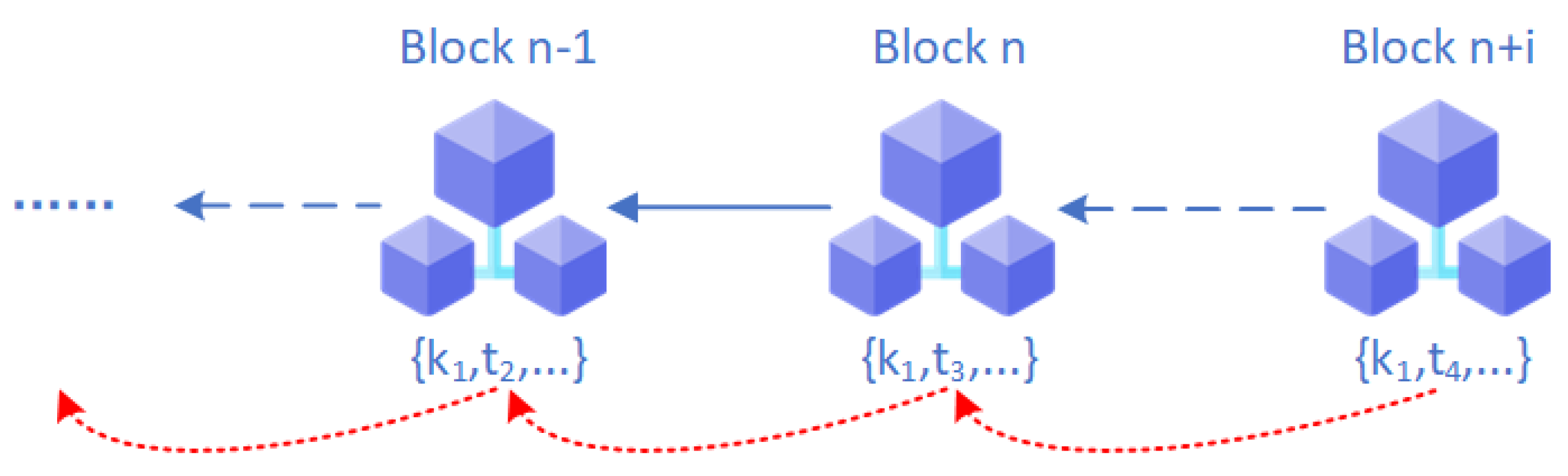

- A fast index structure optimized for CIoT multimedia application scenarios is designed. By storing key index items and combining them with the traceability positioning table, direct cross-block jumps can be achieved, significantly reducing block traversal operations. To further enhance the interpretability and decision-making value of the traceability path, a comprehensive path quantitative scoring method is proposed, evaluating the traceability path based on factors such as path length, block confirmation count, and node reputation.

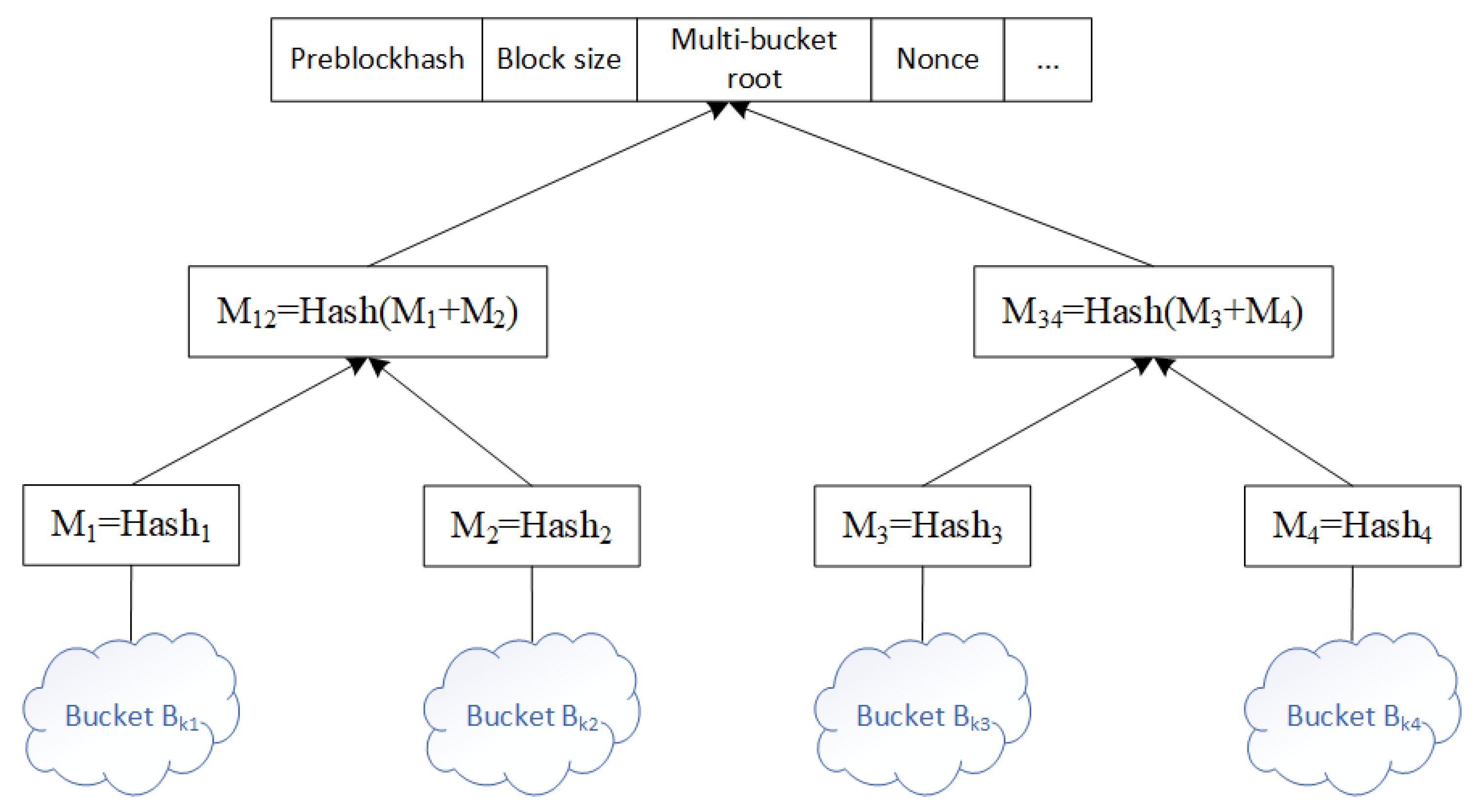

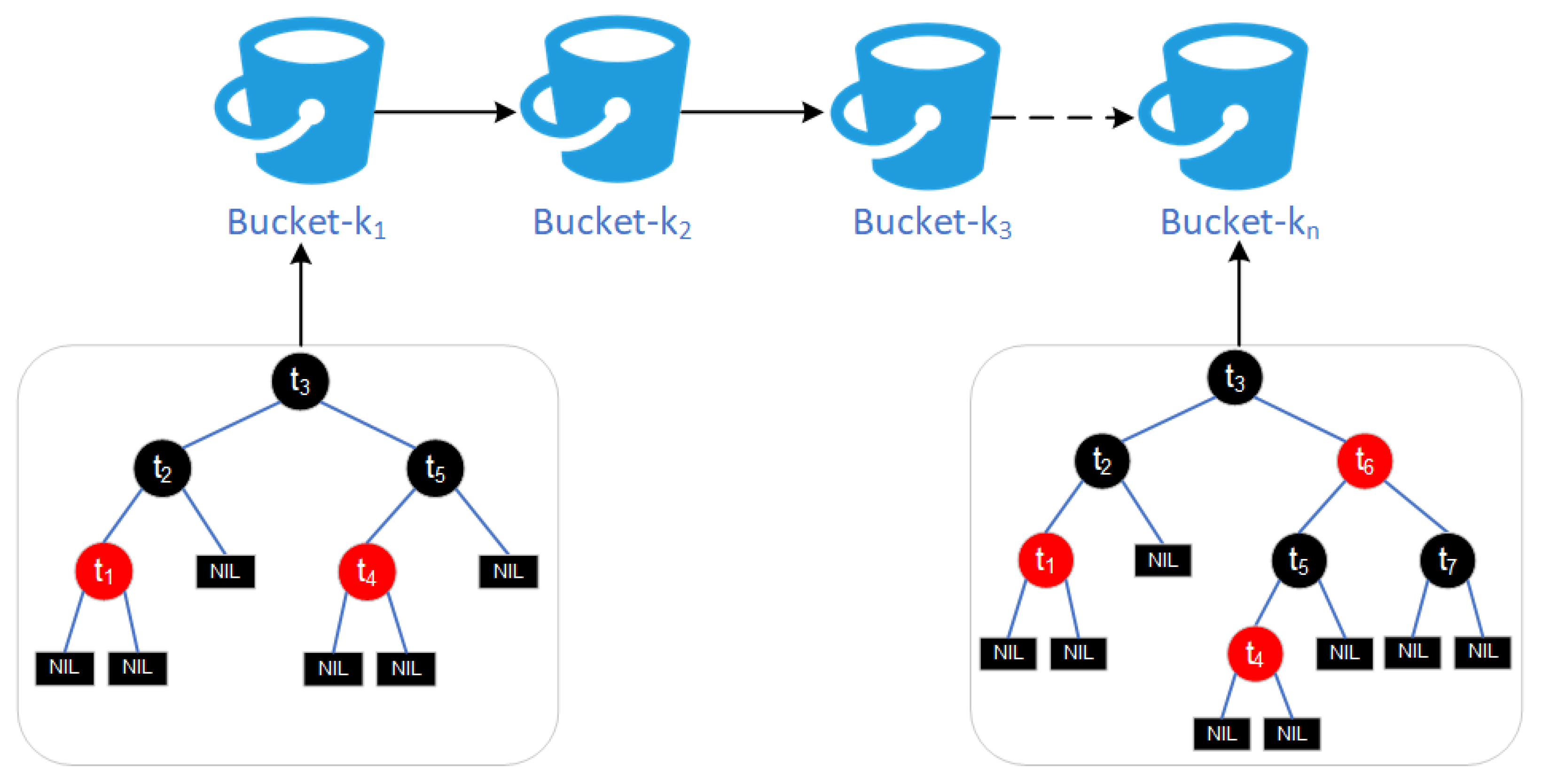

- A multi-bucket indexing mechanism based on multimedia keywords is constructed to efficiently manage the grouping of data objects within blocks. This structure groups data based on multimedia data characteristics using keywords, and maintains the order and searchability of data within each bucket using a self-balancing binary search tree. Additionally, an instant adjustment algorithm is designed to address structural imbalance issues in high-concurrency environments, improving system stability without sacrificing query efficiency.

- The proposed approach comprehensively addresses key security challenges in CIoT multimedia applications, including protection against content tampering, unauthorized distribution, and ensuring data authenticity through cryptographic techniques and immutable blockchain records. The mechanism provides a robust framework for copyright protection and ownership verification in distributed CIoT environments.

2. Related Work

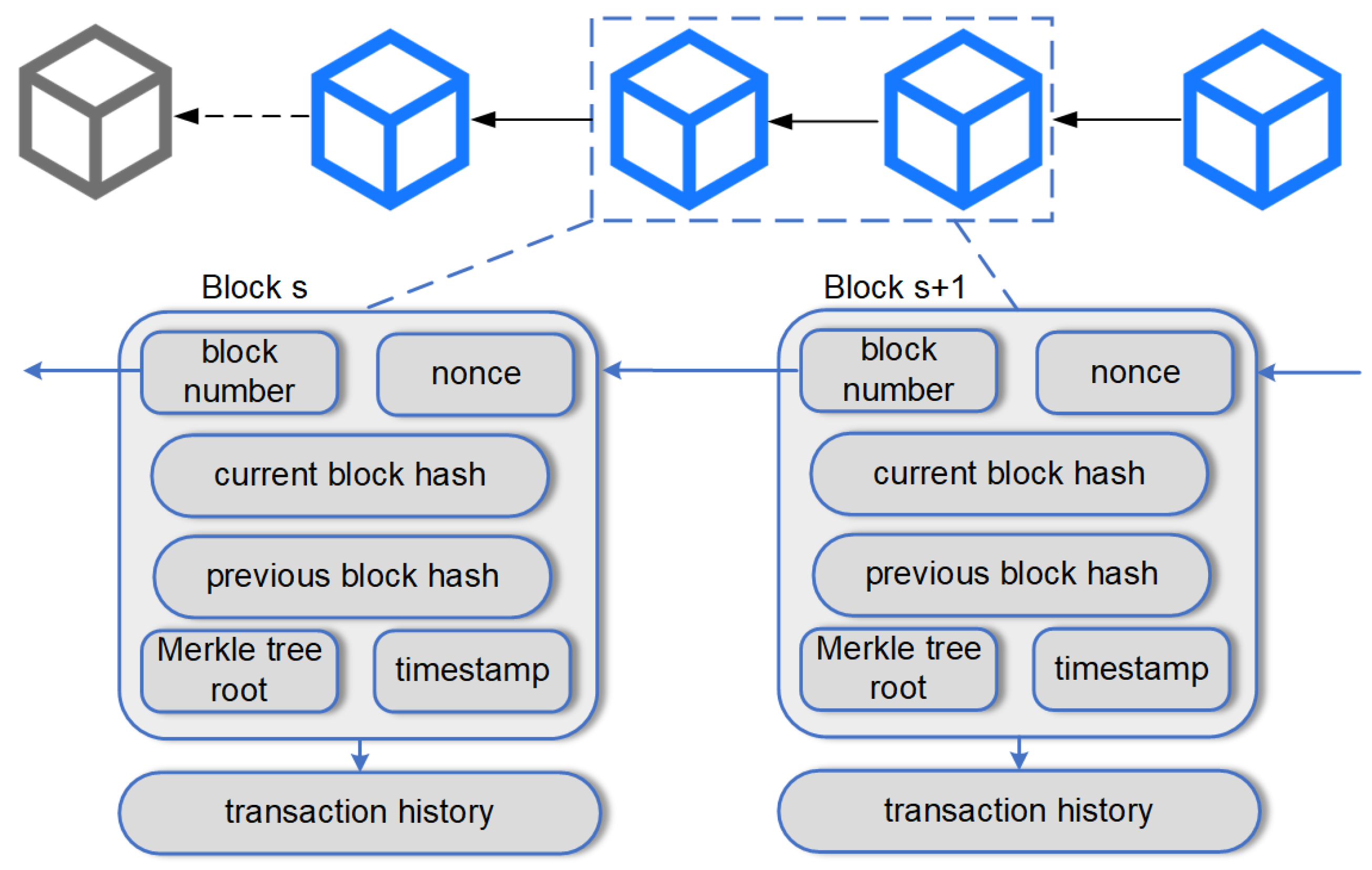

2.1. Blockchain Technology

2.2. Data Traceability Based on Blockchain

2.3. Multimedia Security Research in CIoT

3. Efficient Traceability Mechanism for Multimedia Data Security in CIoT Combined with Blockchain

3.1. Blockchain Efficient Traceability Model for Multimedia Data

3.2. PROV Security Model Based on Blockchain

3.3. Quick Index

3.3.1. Traceability Positioning Table

3.3.2. Comprehensive Path Quantitative Scoring

3.4. Multi-Bucket Index Structure and Data Query Optimization Within Blocks

3.4.1. Multi-Bucket Index Design

3.4.2. Bloom Filter-Based Screening Mechanism

3.4.3. Data Management and Self-Balancing Optimization Based on Binary Search Tree

| Algorithm 1 Timely Adjustment |

|

3.5. Security Analysis and Risk Mitigation

- Keyword Pattern Exposure Protection: Keywords are generated using cryptographic hashing of content identifiers combined with device-specific metadata, ensuring that patterns cannot be reconstructed from observable data. The hash-based approach prevents correlation attacks and maintains data privacy while enabling efficient indexing.

- Secure Key Management for CIoT Devices: We employ elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) for digital signatures, which provides strong security with relatively small key sizes suitable for resource-constrained CIoT devices. The system implements a lightweight key management protocol that includes periodic key rotation and secure key storage mechanisms, balancing security requirements with device limitations.

- Resilience to Prolonged Forks: Our traceability positioning table incorporates an automatic compensation mechanism with rollback logs that ensure consistency during blockchain reorganizations. This design maintains data integrity and query accuracy even during extended fork scenarios, preventing stale references and ensuring reliable traceability.

- Index Security and Tamper Resistance: All index structures are protected through the same cryptographic mechanisms as the blockchain data itself. Any attempt to modify index entries would require breaking the blockchain’s consensus, ensuring that indexes maintain the same immutability properties as the underlying data.

- Sybil Attack Resistance: The node reputation scoring system integrated into our path evaluation mechanism helps mitigate Sybil attacks by prioritizing queries through nodes with established trust histories, making it economically and computationally impractical for attackers to manipulate the traceability system.

3.6. Summary of Model Robustness and Security

4. Simulation Experiment and Analysis

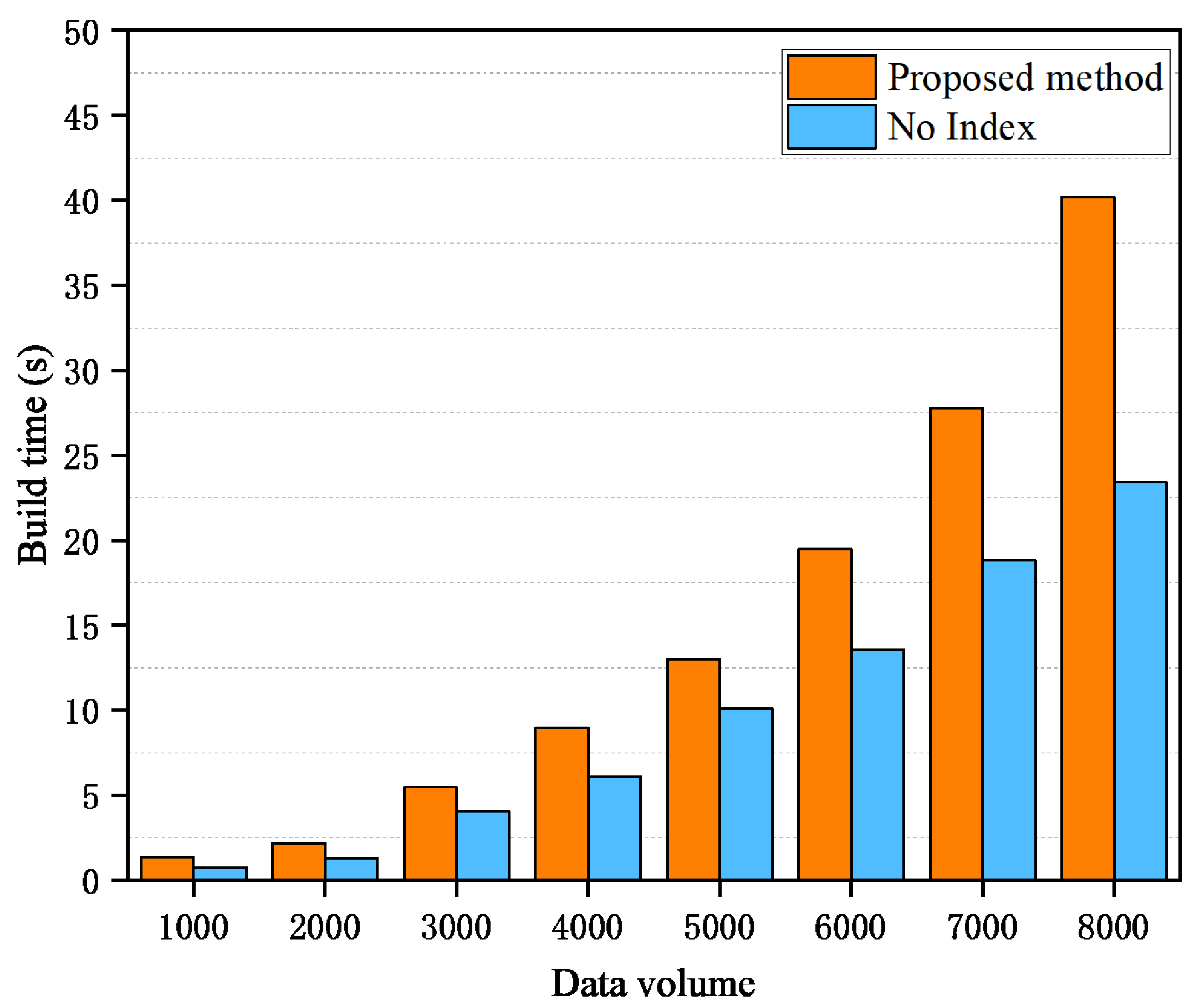

4.1. Build Time Overhead

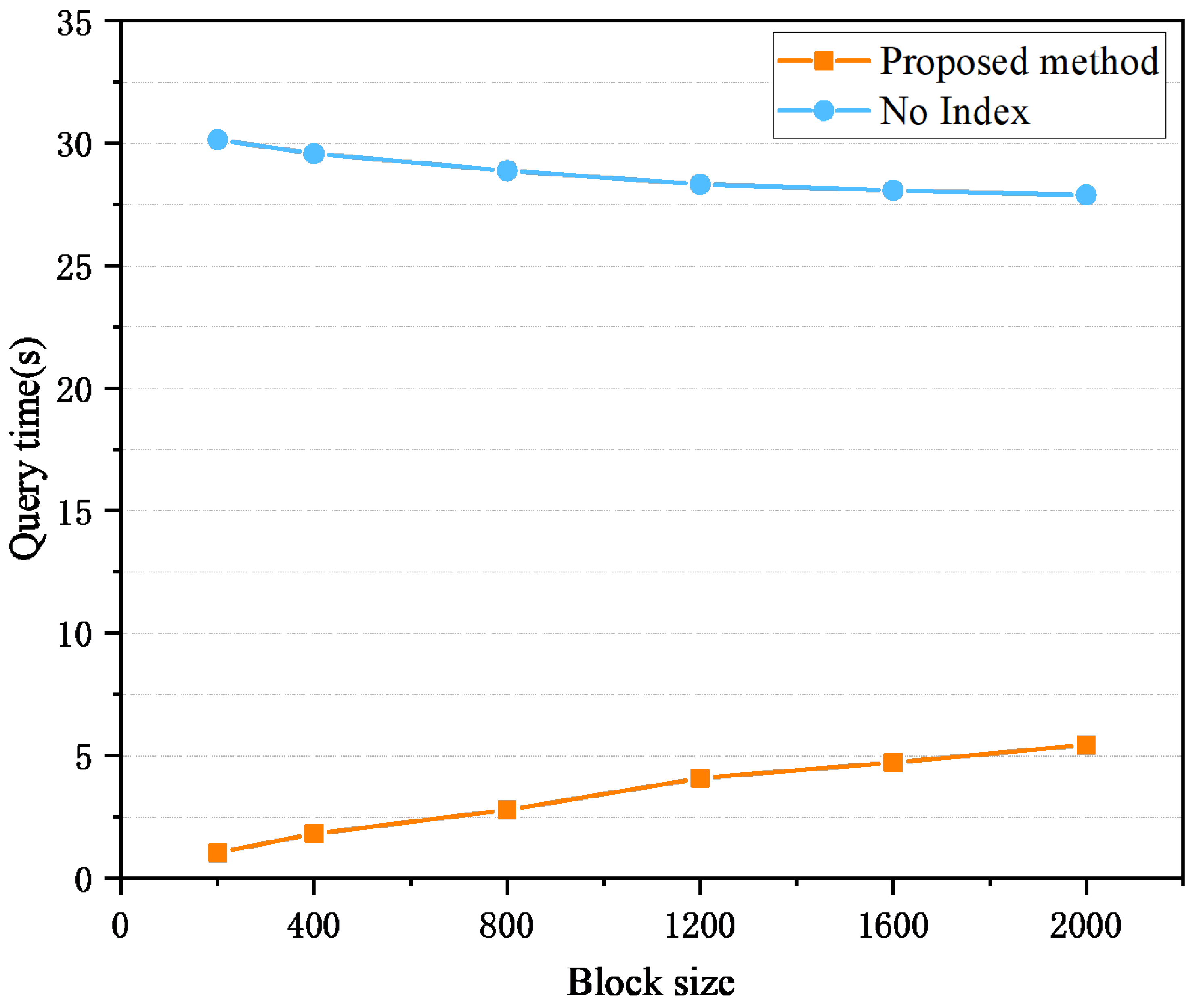

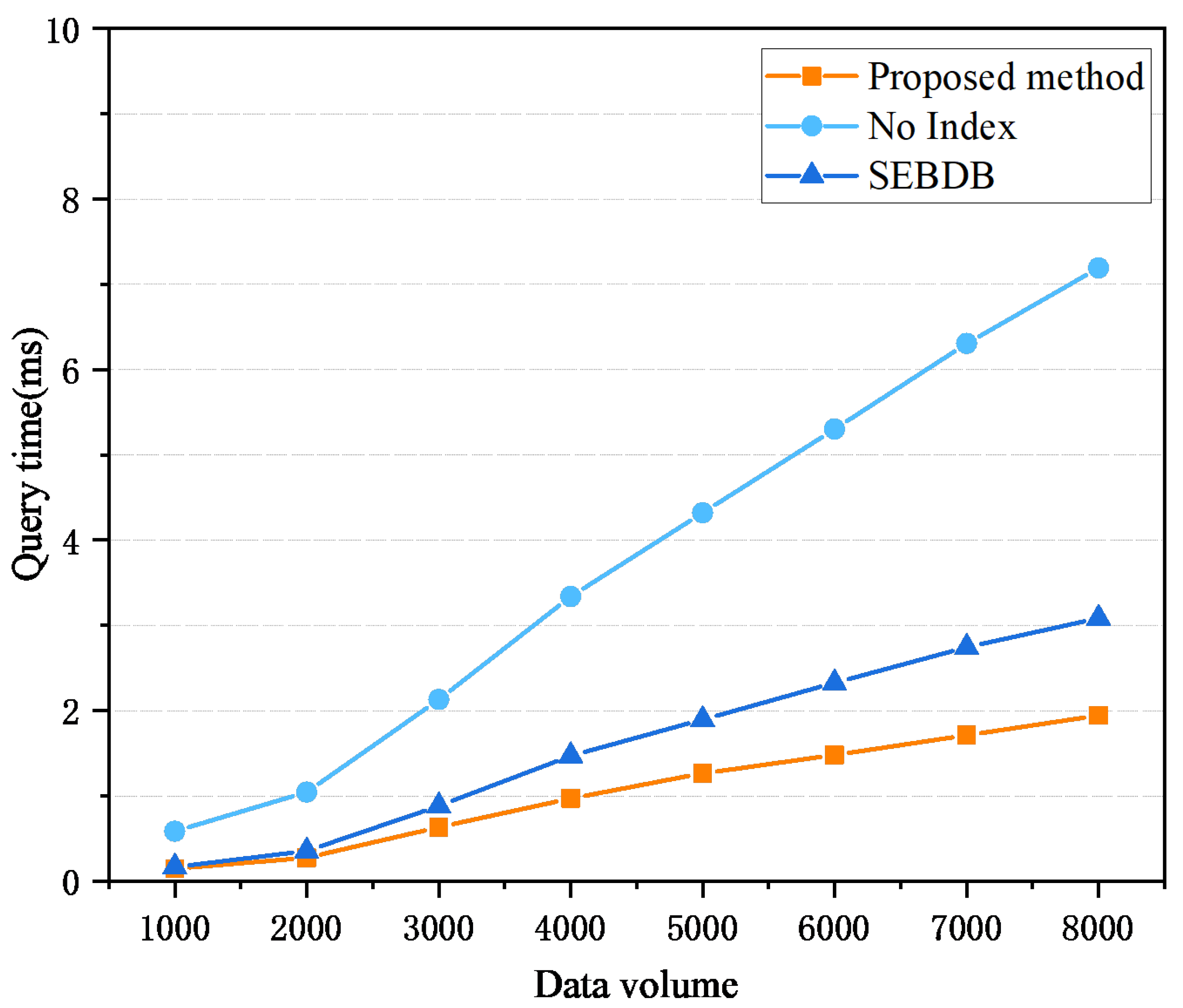

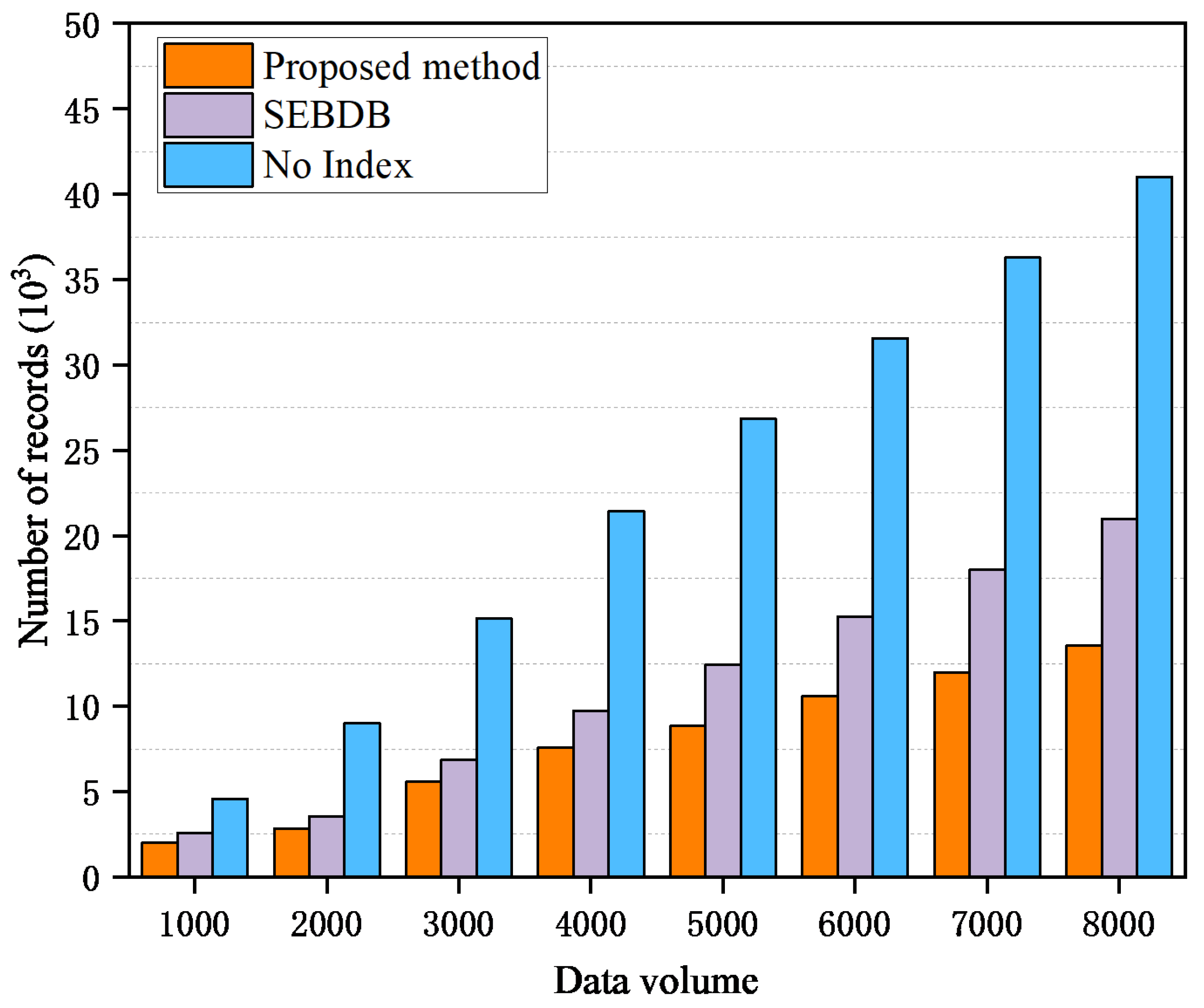

4.2. Query Performance Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enaya, A.; Fernando, X.; Kashef, R. Survey of Blockchain-Based Applications for IoT. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liang, W.; Wang, J.; Tan, G.; Lei, X.; Jing, L. TraceChain: A blockchain-based scheme to protect data confidentiality and traceability. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2022, 52, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Stakhanova, N.; Ray, S. Data provenance in security and privacy. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schintler, L.A.; McNeely, C.L. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Big Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hader, M.; Tchoffa, D.; Mhamedi, A.E.; Ghodous, P.; Dolgui, A.; Abouabdellah, A. Applying integrated Blockchain and Big Data technologies to improve supply chain traceability and information sharing in the textile sector. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 28, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Long, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Y. A controllable privacy data transmission mechanism for Internet of things system based on blockchain. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Lv, Z.; Xiong, N.; Wang, J. HCNCT: A Cross-chain interaction scheme for the blockchain-based metaverse. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Cheng, X.; Dai, Y. AI-driven hypergraph neural network for predicting gasoline price trends. Energy Econ. 2025, 151, 108895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Xia, F. Path signature-based XAI-enabled network time series classification. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2024, 67, 170305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Leng, Y.; Qi, J.; Sharma, P.; Wang, J.; Almakhadmeh, Z.; Tolba, A. Multiple cloud storage mechanism based on blockchain in smart homes. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 115, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Analysis of Cross-Border E-Commerce Commodities in Internet of Things Based on Semantic Traceability Algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2017827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdik, D.; Otoum, S.; Schmidt, N.; Porter, D.; Jararweh, Y. A survey on blockchain for information systems management and security. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omisola, J.O.; Bihani, D.; Daraojimba, A.I.; Osho, G.O.; Etukudoh, E.A.; Pub, A. Blockchain in supply chain transparency: A conceptual framework for real-time data tracking and reporting using blockchain and AI. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2023, 4, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Xie, W.; Pang, M.; Shi, Y. A novel discrete conformable fractional grey system model for forecasting carbon dioxide emissions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 13581–13609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Na, M.; Song, J. Dual-layer index for efficient traceability query of food supply chain based on blockchain. Foods 2023, 12, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, C.; Zhou, A.; Yan, Y. SEBDB: Semantics empowered blockchain database. In Proceedings of the 35th IEEE International Conference Data Engineering (ICDE), Macao, China, 8–11 April 2019; pp. 1820–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, Q. Using blockchain technology to enhance the traceability of original achievements. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, F.R.; Luan, T.H.; Zhao, P.; Liu, S. A survey of blockchain and intelligent networking for the metaverse. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 3587–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, C. Proof-of-work based blockchain technology and Anthropocene: An undermined situation? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz-Schilling, C.; Neu, J.; Monnot, B.; Asgaonkar, A.; Tas, E.N.; Tse, D. Three attacks on proof-of-stake ethereum. In Proceedings of the International Conference Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Saint George’s, Grenada, 2–6 May 2022; pp. 560–576. [Google Scholar]

- Distler, T. Byzantine fault-tolerant state-machine replication from a systems perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belchior, R.; Vasconcelos, A.; Guerreiro, S.; Correia, M. A survey on blockchain interoperability: Past, present, and future trends. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalodner, H.; Goldfeder, S.; Chator, A.; Möser, M.; Narayanan, A. Design and applications of a blockchain analysis platform. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.02489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, S.; Roggia, M.; Ioini, N.E.; Pahl, C. Ethernitydb–integrating database functionality into a blockchain. In Proceedings of the New Trends in Databases and Information Systems: ADBIS 2018 Short Papers and Workshops, Budapest, Hungary, 2–5 September 2018; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Muzammal, M.; Qu, Q.; Nasrulin, B. Renovating blockchain with distributed databases: An open source system. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 90, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wei, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Y. An efficient query scheme for privacy-preserving lightweight bitcoin client with Intel SGX. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Shi, J.; Huang, C.; Hu, X. Blockchain based data integrity verification for cloud storage with T-merkle tree. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing, New York City, NY, USA, 2–4 October 2020; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Kong, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q. ECBC: A high performance educational certificate blockchain with efficient query. In Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Theoretical Aspects of Computing–ICTAC, Hanoi, Vietnam, 23–27 October 2017; pp. 288–304. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Li, M.; Yu, H.; Wang, M.; Xu, D.; Sun, C. A trusted blockchain-based traceability system for fruit and vegetable agricultural products. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36282–36293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y. Blockchain-based data traceability platform architecture for supply chain management. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE International Conference Big Data Security on Cloud, IEEE International Conference High Performance and Smart Computing (HPSC), and IEEE International Conference Intelligent Data and Security (IDS), Baltimore, MD, USA, 25–27 May 2020; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Shetty, S.; Tosh, D.; Kamhoua, C.; Kwia, K.; Njilla, L. Provchain: A blockchain-based data provenance architecture in cloud environment with enhanced privacy and availability. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE/ACM International Symposium Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID), Madrid, Spain, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Luo, X.; Liu, H.; Xia, X. Merkle tree: A fundamental component of blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Science (EIECS), Changchun, China, 23–26 September 2021; pp. 556–561. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Xu, C. Blockchain-based secure data provenance for cloud storage. In Proceedings of the International Conference Information and Communications Security, Lille, France, 29–31 October 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, A.; Kantarcioglu, M. Smartprovenance: A distributed, blockchain based dataprovenance system. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference Data and Application Security and Privacy, Tempe, AZ, USA, 19–21 March 2018; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs, K.N.; Ossipova, O.; Kohlios, C.P.; Baccarini, A.N.; Howson, E.A.; Hayajneh, T. Healthcare blockchain system using smart contracts for secure automated remote patient monitoring. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkodi, S.; Kesavaraja, D. Secure data provenance in Internet of Things using hybrid attribute based crypt technique. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 118, 2821–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Zhang, K.; Gherbi, A. Privacy-preserving smart grid traceability using blockchain over IoT connectivity. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Virtual Event, Republic of Korea, 22–26 March 2021; pp. 699–706. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakos, T.; Dilshener, T.; Kravtsov, A.; Marra, A.L.; Martinelli, F.; Rizos, A. Trust aware continuous authorization for zero trust in consumer internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Guangzhou, China, 29 December 2020; pp. 1801–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Namakshenas, D.; Yazdinejad, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Srivastava, G. Federated quantum-based privacy-preserving threat detection model for consumer internet of things. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 5829–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; McMahon, E.; Samtani, S.; Patton, M.; Chen, H. Identifying vulnerabilities of consumer Internet of Things (IoT) devices: A scalable approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Beijing, China, 22–24 July 2017; pp. 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, B.; Sharma, C. Adaptive and Context-Aware Authentication Framework for Future Vehicular Networks Using Edge AI and Blockchain. J. Secur. Risk Manag. 2024, 15, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords | Timestamp | preTraceHash |

|---|---|---|

| 0x124ghb246… | ||

| 0x634brx537… | ||

| 0x483dgd709… | ||

| 0x638agh971… | ||

| … | … | … |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, T.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, G. High-Efficiency Traceability Mechanism for Multimedia Data in Consumer Internet of Things Combined with Blockchain. Sensors 2026, 26, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010074

Yan T, Chen J, Zhang X, Hu G. High-Efficiency Traceability Mechanism for Multimedia Data in Consumer Internet of Things Combined with Blockchain. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Tianyi, Jimin Chen, Xiaorui Zhang, and Gang Hu. 2026. "High-Efficiency Traceability Mechanism for Multimedia Data in Consumer Internet of Things Combined with Blockchain" Sensors 26, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010074

APA StyleYan, T., Chen, J., Zhang, X., & Hu, G. (2026). High-Efficiency Traceability Mechanism for Multimedia Data in Consumer Internet of Things Combined with Blockchain. Sensors, 26(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010074