3.1. PSA-Binding Aptameric Sequence Design and Validation

For the development of the US-AuNP-Aggregate, we evaluated two previously published aptameric sequences, aPSA [

20] and AS2 [

21]. The binding ability and affinity of these aptamers was assessed by direct ELONA [

27] (

Section S1, Figure S1). In our experiments, the aPSA aptamer did not exhibit any detectable binding response (

Figure S1A). In contrast, the AS2 sequence demonstrated significant binding starting at a concentration of 250 nM (

t-test,

p < 0.05), confirming its binding ability under our experimental conditions, which included a temperature of 37 °C and physiological saline concentration (

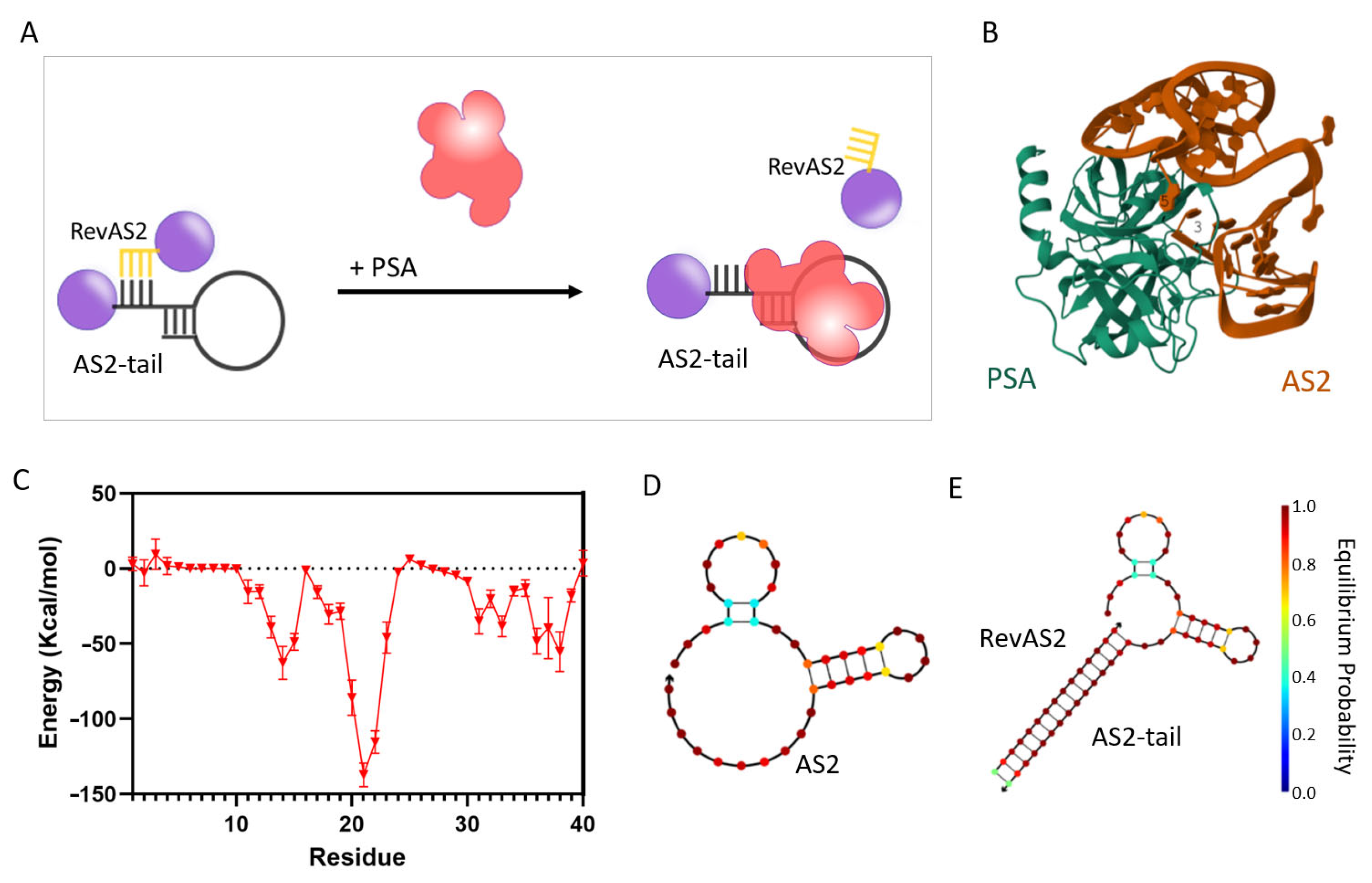

Figure S1B, black line; Section S1). Considering these results, we selected the AS2 aptamer for the development of the switchable nucleotidic architecture. This construct relies on two DNA sequences: AS2-tail, which includes the AS2 aptamer flanked by a tail of additional bases, and RevAS2, which is complementary to a portion of AS2-tail (as better explained below) and is designed to be released upon PSA recognition (

Figure 1A,

Table S1).

In order to achieve this, the design of RevAS2 is critical: in particular, the selection of the AS2 bases annealing to it is essential for enabling the switching mechanism. These specific AS2 nucleotides hybridising with RevAS2 (referred to as “trigger nucleotides”) should interact with PSA with an energy high enough to support the triggering of the system activation but should not be part of the highest-affinity binding domains. In this way, these high-affinity regions can start the recognition of PSA, bringing also the trigger nucleotides into close proximity to the domain of the protein where they bind. This spatial arrangement should facilitate the complete aptamer engagement with PSA, thereby inducing de-hybridisation of the duplex structure. However, experimentally identifying the most effective trigger nucleotides can be labour-intensive. To streamline this, we analysed the molecular interactions between the AS2 aptamer and PSA using a previously developed molecular docking approach [

19]. As shown in

Figure 1B, the energy contributions of individual nucleotides calculated from the docking results (

Figure 1C) revealed a key interaction domain spanning bases 17 to 24, part of a stem-loop structure spanning bases 17–30 (see the secondary structure prediction in

Figure 1D). Additional interactions derive from nucleotides 11 to 15, which form another part of a prominent stem-loop structure spanning bases 4–14 at the 5′ terminus (

Figure 1D), and from the 3′ end, between bases 31 to 39, in a region that is unstructured in the free aptamer. Based on these findings, RevAS2 was designed to hybridise this last region, in particular with nucleotides 32–40 at the 3′ terminus of the AS2 aptamer. Comparative secondary structure predictions at 37 °C for the unmodified AS2 aptamer and the AS2-tail:RevAS2 duplex (

Figure 1D,E) suggested the maintenance of the aptamer native folding, which is essential for PSA binding. A control duplex (AS2ctrl:RevAS2ctrl) was designed using a scrambled sequence for the aptamer (

Figure S2A,B). The full list of sequences used in this study is provided in

Table S1.

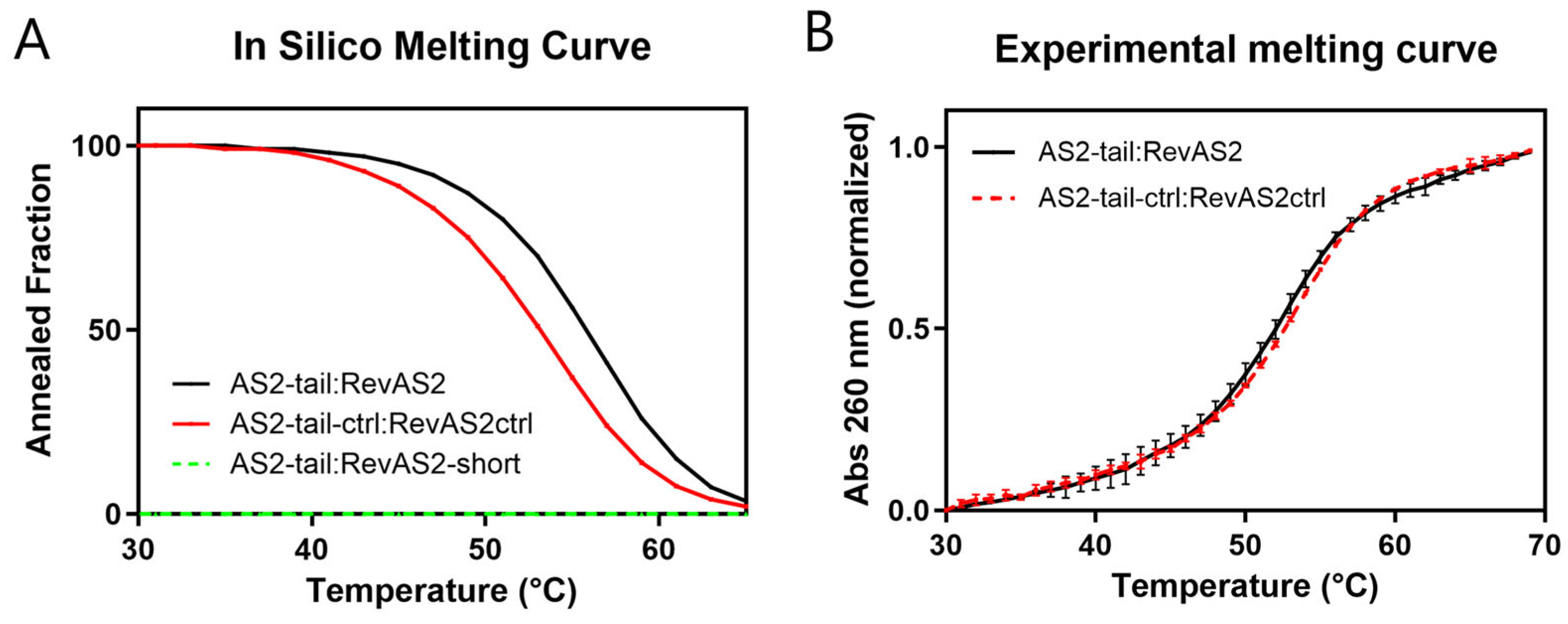

Since the sensing reaction is designed to work at body temperature (37 °C), we assessed the thermal stability of the AS2-tail:RevAS2 and AS2-tail-ctrl:RevAS2-ctrl duplexes. Melting temperatures (T

m) were calculated during the duplex design stage using NUPACK simulations, which predicted a T

m of 56 °C for the AS2-tail:RevAS2 duplex and 53 °C for the AS2-tail-ctrl:RevAS2-ctrl duplex (

Figure 2A,

Table S2). To estimate the stability of AS2-tail:RevAS2 upon PSA binding, we predicted the melting curve for a RevAS2-short strand, obtained from RevAS2 removing the nucleotides complementary to the aptamer, hybridised with the complete AS2-tail. This resulted in no duplex formation within the considered temperature range, suggesting that the duplex would not remain stable upon PSA binding (

Figure 2A, green dashed line). The experimentally measured T

m was 52 °C for the AS2-tail:RevAS2 duplex and 53 °C for AS2ctrl:RevAS2ctrl (

Figure 2B,

Table S2), consistent with the simulated values.

The affinity of the AS2-tail:RevAS2 duplex for PSA was confirmed by ELONA, obtaining a significant signal starting from a dsDNA concentration of 250 nM (

t-test,

p < 0.05). These findings demonstrate that AS2 retains its binding capability when incorporated into the duplex structure, maintaining comparable affinity to the native aptamer sequence under physiological conditions (

Figure S1B, Supplementary Result S1).

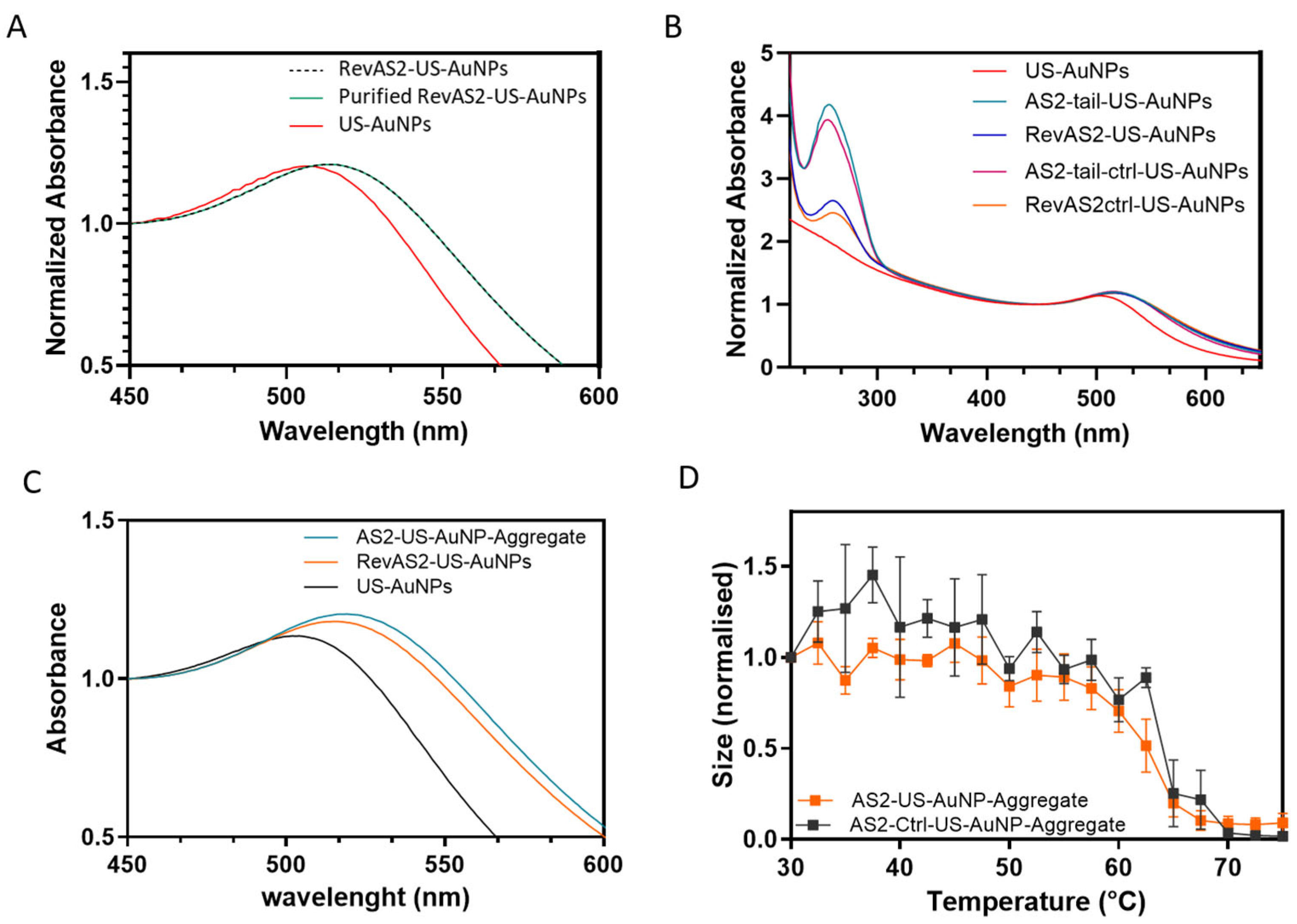

3.2. Ultrasmall-AuNP Functionalisation and Characterisation

US-AuNPs, synthetised as explained in the experimental section, were characterised for both size and zeta-potential by DLS (

Table S3) and for plasmonic properties by absorbance reading (

Figure 3A–C and

Table S3). The obtained US-AuNPs showed an hydrodynamic diameter with a number-weighted average size of 4.6 ± 0.2 nm; a plasmonic peak at 508.0 ± 1.0 nm, consistent with the expected nanoparticle size [

26] (

Figure 3A, red line); and a zeta-potential of −11.5 ± 1.3 mV (measurements are in triplicate and derived from a single batch preparation of nanoparticles; uncertainty is the standard deviation). The plasmon peak position of the naked US-AuNPs was evaluated 24 h post-synthesis, revealing a slight redshift, an indication of an increased size, thus of a colloidal instability (

Figure S3). This increase in size is supported by an increase in the measured intensity-weighted average of the diameters, from 7.4 ± 0.3 nm to 9.3 ± 1.0 nm (although the number-weighted average diameter remained consistent, from 4.5 ± 0.6 to 4.5 ± 0.2 nm). Even if the effect was small, these results suggest that naked US-AuNPs tend to aggregate into larger NPs and highlight the necessity for immediate functionalisation after preparation. Accordingly, in the following syntheses, we immediately functionalised the US-AuNPs with thiolated oligonucleotides (AS2-tail-thio, RevAS2-thio, AS2-tail-ctrl-thio, and RevAS2-ctrl-thio; see

Table S1). AS2-tail-, RevAS2-, AS2-tail-ctrl-, and RevAS2-ctrl-US-AuNPs refer to gold nanoparticles functionalised with the respective DNA sequences. ssDNA-US-AuNPs were characterised for size and plasmonic peak before and after the last purification step, revealing no changes in their properties (

Figure 3A), and this also supports the absence of aggregation. The obtained ssDNA-US-AuNPs showed an increased hydrodynamic radius (11.9 ± 0.4 nm for AS2-tail-US-AuNPs and 7.7 ± 0.4 for RevAS2-US-AuNPs), a plasmonic peak shifted toward longer wavelengths (517.5 ± 0.3 nm for As2-tail-US-AuNPs and 515.3 ± 0.3 for RevAS2-US-Au-NPs), and a lower zeta-potential (−19.7 ± 0.5 mV for AS2tail-US-AuNPs and −18.8 ± 1.8 mV for RevAS2-US-AuNPs) compared to US-AuNPs. AS2ctrl-US-AuNPs and RevAS2ctrl-US-AuNPs exhibited the same trend (full characterisation data are reported in

Table S3). The number of DNA molecules per nanoparticle was calculated by comparing the absorbance spectra of the US-AuNPs with those of the ssDNA-functionalised US-AuNPs (

Figure 3B), as explained in the experimental section, obtaining an averaged estimated ssDNA/particle functionalisation ratio of 8.1 ± 2.9.

3.3. US-AuNP-Aggregate Assembly and Characterisation

The aggregates were assembled as described in the experimental section. The resulting number-averaged sizes of the aggregates were 189 ± 35.3 nm for the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate and 157.5 ± 31.6 nm for the AS2ctrl-US-AuNP-Aggregate. The plasmonic peak fell at 526.5 ± 0.5 nm and 528.3 ± 0.5 nm, respectively (

Table S3,

Figure 3C). Even if the plasmonic shift was lower than the one expected for full gold NPs with the same diameter as the one measured by DLS, it was positive, as expected for the increase in US-AuNP-Aggregate size. In these aggregates, nanoparticles are linked by an oligonucleotide sequence of about 40 base pairs, resulting in an average interparticle distance of about 12 nm. As previously reported in similar structures [

19], this spacing leads to only partial plasmonic electromagnetic coupling between the US-AuNPs and therefore to a reduced plasmonic shift.

Thermal stability studies of the US-AuNP-Aggregates demonstrated that the nanostructures remain stable at physiological temperature and undergo disassembly into individual US-AuNPs upon reaching temperatures a little higher than the T

m of the involved duplexes (

Figure 3D and

Table S2). These results are also in agreement with the fact that aggregate formation is driven by annealing-induced assembly of the DNA-linked nanoparticle. The slightly higher melting temperature of the US-AuNP-Aggregates than the one of the dsDNA alone may be attributed to various factors that introduce complexity and influence the T

m when transitioning to DNA-linked nanoarchitectures, such as the DNA surface coverage, its high density on the surface, and the expected multiple dsDNA-linkages between NPs [

28].

3.4. AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate Response to PSA

The kinetic behaviour of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates alone and upon PSA introduction are key factors in assessing their suitability for potential practical in vivo applications. In the absence of PSA, the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate and the AS2-Ctrl-US-AuNP-Aggregate showed no significant size variation over time, as observed in the DLS measurements, indicating stability over at least 30 min at 37 °C (

Figures S4 and S5B). Moreover, although no specific long-time stability analysis was performed, we observed that the aggregates remained functional for at least one week if stored at 4 °C.

The AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate kinetic upon interaction with PSA was preliminary investigated by incubating it with PSA at 1 pM and 1 nM concentrations (

Figure S4A). Notably, the number-weighted size distribution analysis proved more sensitive than the intensity-weighted size distribution analysis for detecting smaller particles in the sample (

Figure S4A; cyan vs. violet dots in

Figure S5); these smaller particles likely correspond to single nanoparticles or smaller aggregates released from the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates. Smaller particles were observed by DLS at 15–20 min of incubation with PSA at 1 pM concentration, even if they were not always highlighted by the number-averaged size either (

Figure S4A and S5C). This occurred more frequently at 1 nM PSA, starting after about 5 min (

Figure S4A and S5D). Despite the occasional bigger impact of larger particles after the aggregate started to disassemble, these data indicate a concentration-dependent response. The AS2-Ctrl-US-AuNP-Aggregate, under the same conditions, did not show distinct changes in size over the observed period (

Figure S4B), confirming the specificity of the reaction.

To gain deeper insights into the mechanism underlying aggregate disassembly and, in particular, the irregular behaviour observed for the number-weighted size distributions, we conducted a more in-depth analysis of the DLS data. Indeed, the accuracy of the fit provided by the DLS software can be affected by long-time decays in the autocorrelation function, due to sedimentation or movement of large aggregates, dust particles, or bubbles. These can introduce a background signal that affect data interpretation. To mitigate this issue, we performed an additional regression analysis of an autocorrelation function generated by the DLS software, by fitting it with simpler functions from whose parameters we estimated one, two, or three sizes characterising the size distribution of the nanostructures in the observed suspension (

Figure S5A; refer to the experimental section for details). The results of this analysis did not contradict the previous results about stability and dose–response behaviour of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates. However, they helped with better visualising the appearance 8–15 min upon PSA introduction of at least two populations of scattering entities characterised by sizes d

1 and d

2 (see

Figure S5C,D and the experimental section for details). These observations are also supported by analysing the intensity-weighted distributions of sizes at different times after the introduction of different concentrations of PSA in the solution containing the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates (

Figure S6), which revealed the appearance of a second peak with smaller hydrodynamic radius 8/13 min after PSA addition (

Figure S6B,C). Another, simpler way to highlight and quantify this trend was to consider the time average (and standard error) of the DLS number-weighted-average size in a ~5-min range (or more) after 15 min upon PSA addiction (

Figure S6D). This approach allows for a faster automatic description of the DLS outputs and is utilised for the presentation of the next results.

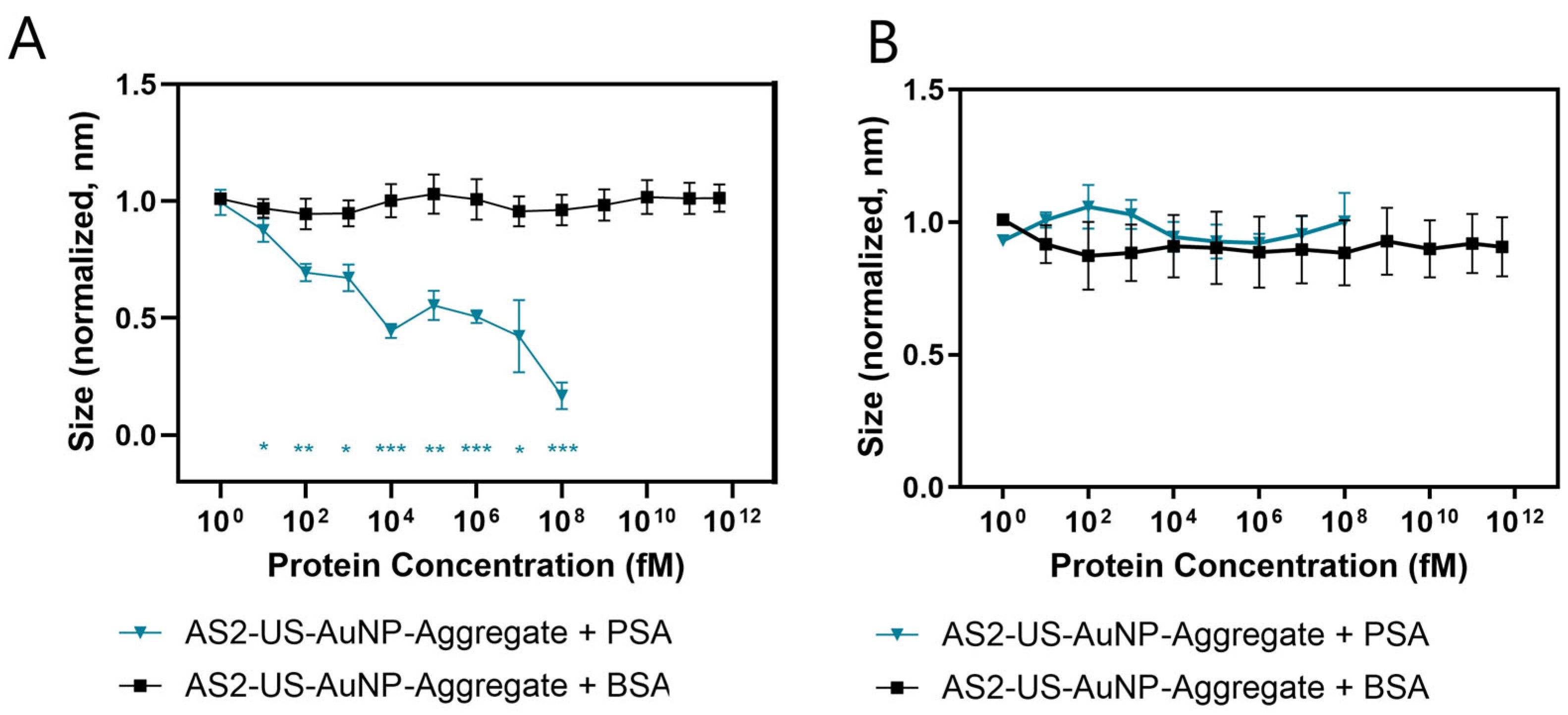

The response of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate to PSA was evaluated across a concentration range of 1 fM to 100 nM. Number-weighted means of sizes were averaged over a 5-min interval, beginning 15 min after PSA addition. These average sizes for AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates decreased upon incubation in a concentration-dependent manner (

Figure 4A, blue line and triangles). A statistically significant reduction in the aggregate size was observed starting at a PSA concentration of 10 fM (

t-test). The AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate response increases at higher PSA concentrations, as revealed from a further decrease in the detected average size of the nanostructures (

Figure 4A and

Figure S8A). The specificity of the reaction was tested by incubating the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates with BSA up to its physiological concentrations (500 μM). BSA was selected due to its structural similarity to Human Serum Albumin (HSA); both albumins are commonly used in biophysical and biochemical studies [

29]. No significant changes were observed in the aggregates size upon BSA incubation, even at the highest tested concentration (

Figure 4A, black line). Similarly, the AS2-Ctrl-US-AuNP-Aggregate, under the same conditions, showed no discernible trend either in size variation (

Figure 4B) or for plasmonic shift (

Figure S7B), neither with PSA nor with BSA.

We checked for changes in the UV-Vis absorbance spectra of AS2-Ctrl- and AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates upon introduction of PSA in all tested concentrations and conditions. The AS2-Ctrl-US-AuNP-Aggregate never showed a significant plasmon shift at any concentration, as expected. A tendency of the plasmonic peak towards shorter wavelengths was observed upon incubation of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate with increasing concentrations of PSA; however, this trend was not consistently significant. A clearer variation was detectable only at higher PSA concentrations, where the sensitivity of DLS proved more reliable in capturing aggregate disassembly, although even in this case, the trend was not fully consistent (

Figure S7A). This may be attributed to the weak plasmonic resonance of US-AuNPs and the limited efficiency of interparticle plasmon coupling within the aggregates [

19]. Moreover, larger aggregates are likely to contribute more strongly to UV–Vis measurements; in this context, even a small number of large aggregates may significantly affect the overall spectrum, as their increased scattering and absorbance can mask the contributions of smaller particles.

We are not suggesting to use the methods exploited here in a real clinical sensor to characterise the response of the aggregates to different PSA concentrations; nevertheless, in order to better describe this response, we calculated a sort of calibration curve for both size and plasmon peak position measurements using linear fits in a semilogarithmic scale (

Figure S8). In order to calculate a parameter corresponding to a limit of detection, the fluctuations in the measurement results without PSA are not a good estimate for the uncertainty to be used for the LoD calculation, since these measures are used to “normalise” the data reported in

Figure 4,

Figures S7 and S8 before averaging; for this reason, we extracted an average standard deviation from the fit residuals. In this way, and considering the logarithmic scale for the concentrations, we obtained indicative LoDs of 2.42 pM (from the normalised variation in the number-averaged size) and 1.89 × 10

8 pM (plasmon shift). Notably, the inconsistent trend of the plasmon shift indicates that it is not reliable for quantitative purposes; for this reason, subsequent experiments focused exclusively on DLS measurements. It is important to emphasise that the LoD values are reported only as reference metrics derived from the fitted data, without implying analytical performance or practical detectability for the conceived sensor based on the studied aggregates.

3.5. AS2:RevAS2 dsDNA in Blood-Mimicking Conditions

To accurately evaluate the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate stability and response under conditions that mimic in vivo environments, examination at least in plasma, serum, or mimicking conditions is essential. In the bloodstream, the presence and activity of nucleases, along with the formation of a plasma protein corona, likely affects nanoparticles properties [

30]. We examined how plasma components affect the stability of the AS2-tail:RevAS2 duplex and the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate by comparing the digestion kinetics in the presence of a single nuclease (DNaseI) and in full human plasma. The stability of AS2-tail:RevAS2 sequences in human plasma, or with DNaseI, were estimated using the AS2-tail-Atto580Q:RevAS2-Rhodamine duplex by monitoring the restoration of Rhodamine fluorescence upon nuclease digestion.

Considering the effect of DNAseI alone, we were able to compare the digestion kinetics of the AS2tail:RevAS2 sequences in solution, and when incorporated into the AS2tail-US-AuNP-Aggregates: the stability of AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates was tested for DNAseI digestion, monitored by size variations via DLS, and compared with the results on AS2-tail-Atto580Q:RevAS2-Rhodamine at the same DNA and DNAseI concentrations (

Supplementary Section S2). We obtained a recovery of fluorescence for AS2-tail-Atto580Q:RevAS2-Rhodamine with a half-life of 1.07 ± 0.53 h (

Figure S9A), with complete digestion achieved after 2 h. Checking the DLS-measured number-weighted averaged sizes of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates over time, under identical DNA and DNaseI concentrations, we estimated a half-life of 2.1 ± 0.1 h (

Figure S9B). This finding indicates that the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate provides increased stability to nuclease digestion, as the embedded duplex exhibits almost a two-fold increase in half-life compared to free dsDNA. These results highlight the ability of DNA-driven nanoaggregated architectures to offer a protective effect against deoxyribonucleases activity [

31].

Then, we tested the AS2-tail-Atto580Q:RevAS2-Rhodamine duplex in human plasma; full plasma could not be used with the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate because the background scattering compromised the reliability of the DLS measurements. Also, in the case of fluorescence measurements, we needed to consider a background arising from the plasma components (see

Supplementary Section S3 and Figure S10A). After its subtraction, we obtained an estimated half-life of fluorescence recovery for the AS2-tail-Atto580Q:RevAS2-Rhodamine in 1:8 diluted plasma of 13.2 ± 1.3 h (

Figure S10). Adjusting for the dilution factor and considering a first-order kinetics, the estimated half-life in undiluted plasma was approximately 1.65 ± 0.17 h.

Finally, we investigated the stability and PSA response of AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates in blood-mimicking conditions. However, as stated above, following the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate behaviour in whole plasma using DLS is challenging due the presence of similarly sized particles, including small vesicles, lipoproteins, and protein aggregates. These biological components contribute to significant scattering background and interference, complicating the interpretation of the aggregate size distribution measurements. To address this, female human plasma was purified by centrifugation and filtration to remove all these components. Analysis of the untreated human plasma with DLS revealed two main peaks: one at 145.3 ± 5.9 nm and another at 13.2 ± 2.7 nm. The purification left only smaller molecules, including proteins, as confirmed by the presence of a single peak at 15.9 ± 1.3 nm in the centrifuged and filtered plasma (we show a representative intensity-weighted distribution in

Figure S11).

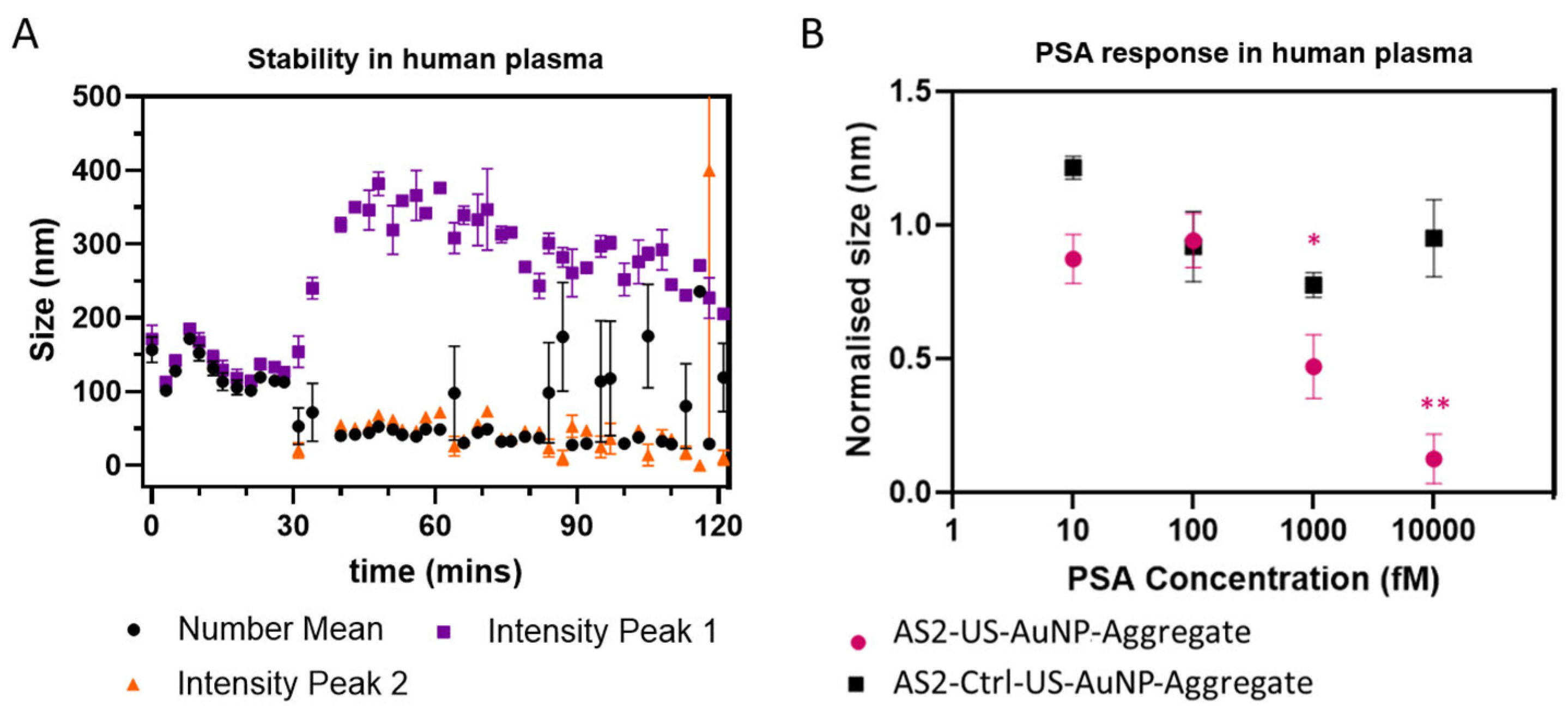

The stability of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates was evaluated in filtered plasma by DLS, as identifying the time window during which the aggregate remains intact is crucial for enabling effective monitoring of the PSA binding reaction.

Figure 5A summarises the results, showing the time behaviour of the number-weighted average size and of the intensity-weighted average size on the total distribution.

Figure 5A shows that the measured size distributions remain relatively constant during the first ~30 min, with a single peak characterised by a number-weighted size of about 110–160 nm and a slightly higher value for intensity-weighted size distributions (see also

Figure S12, black and orange curves), consistent with the stability of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate. After ~30 min, a bipartite distribution of sizes becomes evident in the intensity-weighted size distributions, with two peaks (see also

Figure S12, cyan, blue, and violet curves). The smaller peak has an intensity-averaged size around 50 nm or below, with a tendency towards smaller sizes at longer times. This suggests the formation of smaller components, likely due to the disassembly of AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregates upon their interaction with plasma molecules and, in particular, by nuclease digestion. Additionally, the number-weighted averaged size usually follows the position of this peak, confirming that the size derived from the number distribution highlights the presence of smaller particles in the solution. The larger peak in the intensity-weighted distribution initially increases rapidly, reaching a broad maximum at ~350 nm around 50–60 min, suggesting aggregation or fusion with plasma components. Then, it shows a gradual decrease in size, indicative of ongoing erosion of the aggregates (

Figure 5A and violet and blue curves in

Figure S12). This dynamic behaviour underscores the partial instability of the system beyond 30 min in the plasma environment. Differently from what is observed with DNaseI, the observed half-life of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate in filtered plasma is shorter than the one estimated for the free AS2-tail:RevAS2 duplex in whole plasma. This difference could be caused by differences in the compositions of the two environments (different lots of plasma, treated differently) but anyhow highlights how plasma—a more complex matrix than PBS with DNaseI, even when purified and filtered—affects the aggregate stability differently, likely due to the presence of additional interacting components.

These observations indicate a critical time frame of around 30 min for monitoring PSA before significant structural changes occur. Therefore, we followed the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate response to PSA within 20 min upon analyte addition using DLS (

Figure S13). PSA was tested across a concentration range from 100 fM to 10 pM, taking into account the clinically relevant nadir points of 150 and 300 fM proposed by Thaxton [

5] and Doherty [

4], respectively, as well as the classical nadir point of 6 pM. Time-course analysis revealed a concentration-dependent response. At 1 pM PSA (

Figure S13C), the lowest concentration at which a statistically significant and consistentreduction in the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate size was observed starting at around 8 min, a progressive decrease in size was observed. This size reduction became increasingly distinct over time if compared to the AS2-Ctrl-US-AuNP-Aggregate, with statistically significant differences detected at multiple time points. At 10 pM PSA (

Figure S13D), the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate exhibited a faster and more pronounced reduction in size, with significant changes detectable as early as at 3 min and becoming more evident over the 20-min monitoring period. These results suggest a concentration-dependent response of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate also in filtered plasma, with higher PSA levels inducing a more rapid and more significant structural change.

Figure 5B summarises the results for the number-weighted average size after 20 min of incubation, the longest time point considered to avoid the instability observed in plasma. As already stated, a significant reduction in size of the AS2-US-AuNP-Aggregate was observed starting at 1 pM PSA. These results indicate that the aggregate retains its ability to respond to PSA within a suitable time frame (i.e., before 30 min), even when incubated in a complex environment that mimics physiological blood conditions.