Characterization of a 100 nm RADFET as a Proton Beam Detector

Abstract

1. Introduction

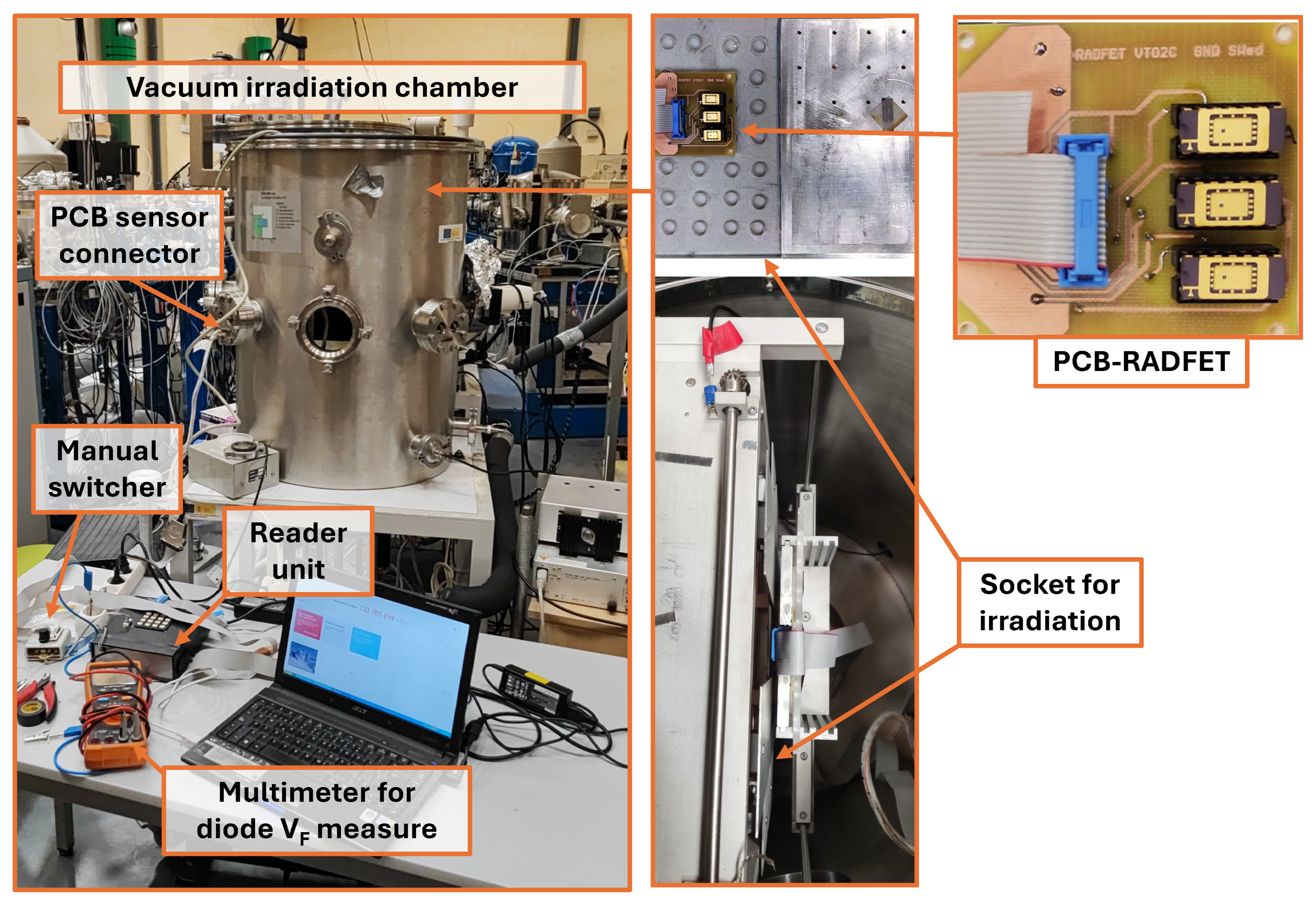

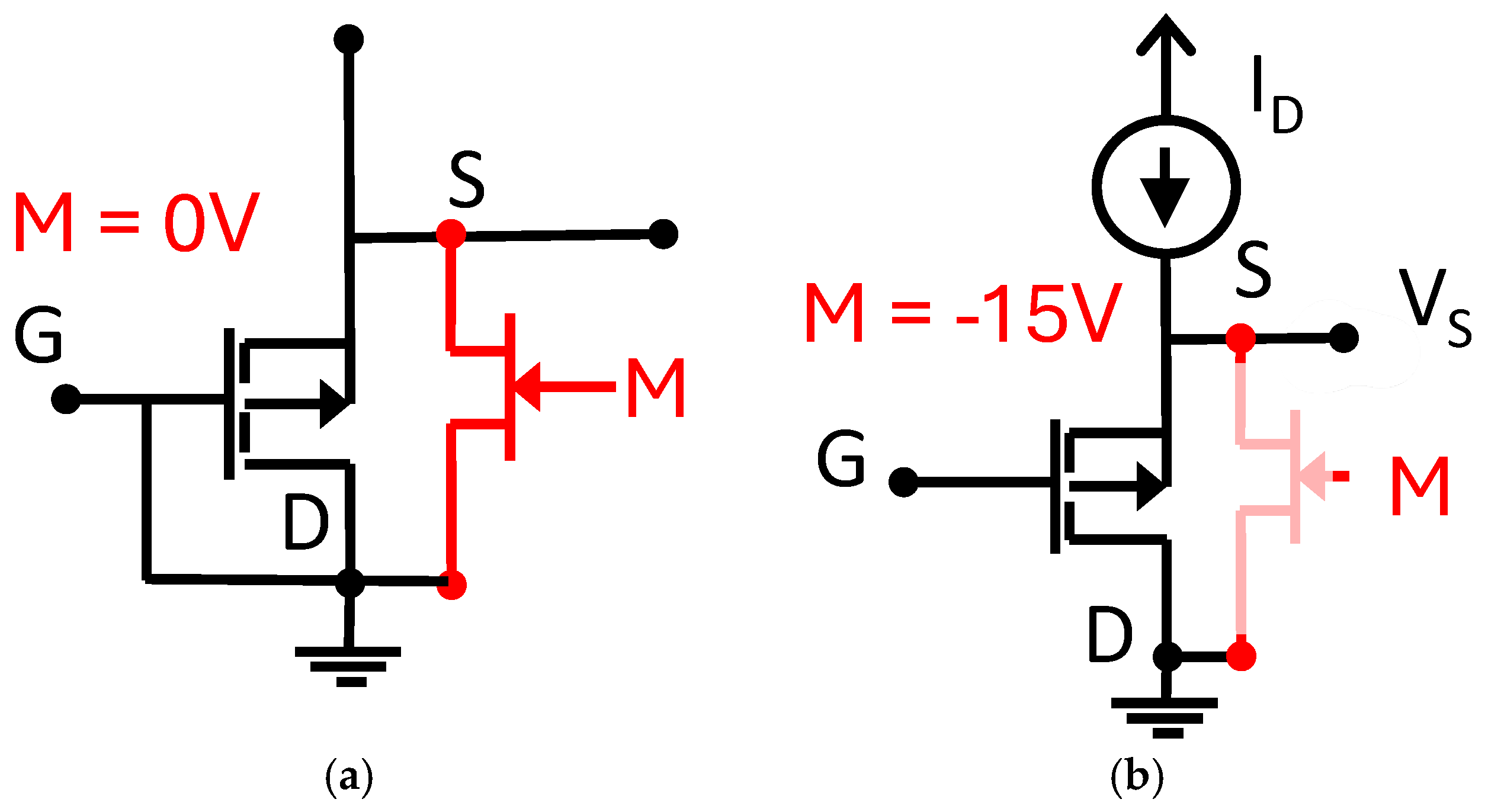

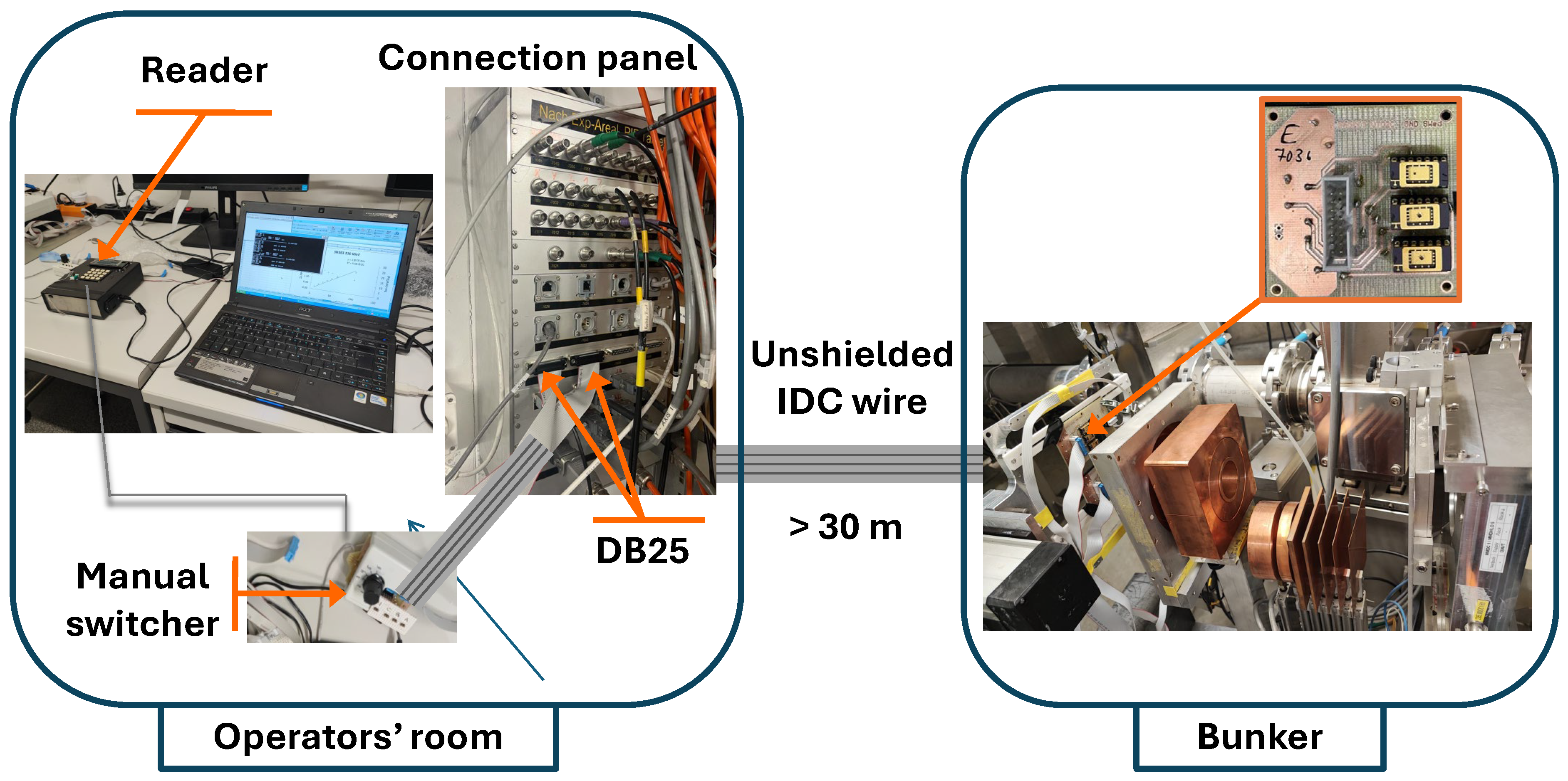

2. Materials and Methods

- Zeroing: The initial source voltage is recorded per each transistor (switching manually).

- Irradiation: The devices are irradiated with all terminal short-circuited.

- Measurement: After at least two minutes since the radiation stops, the source voltage shift is measured and stored per transistor.

- Temperature monitoring: The forward voltage of the chip diode is registered.

3. Results and Discussion

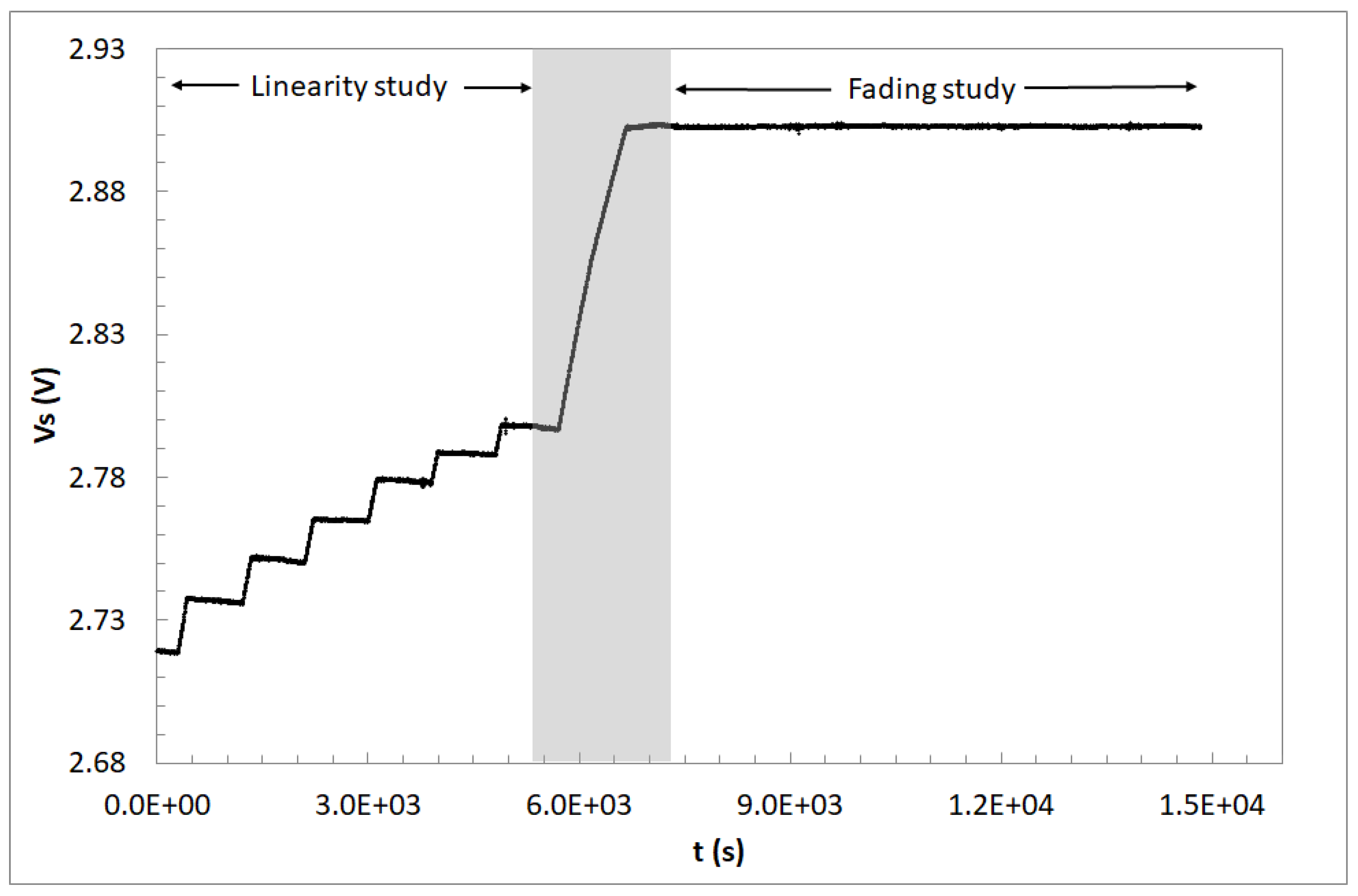

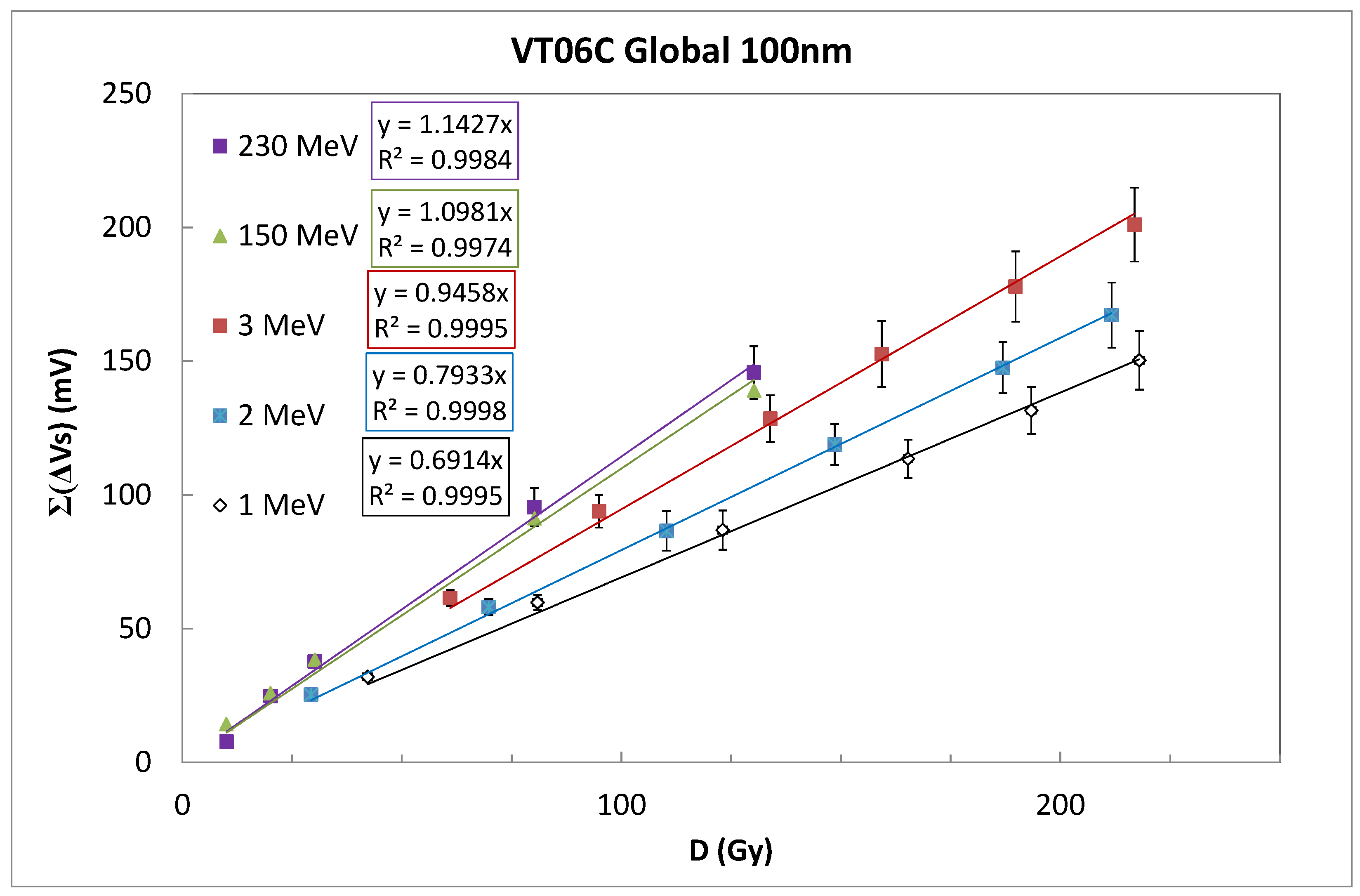

3.1. Sensitivity and Linearity

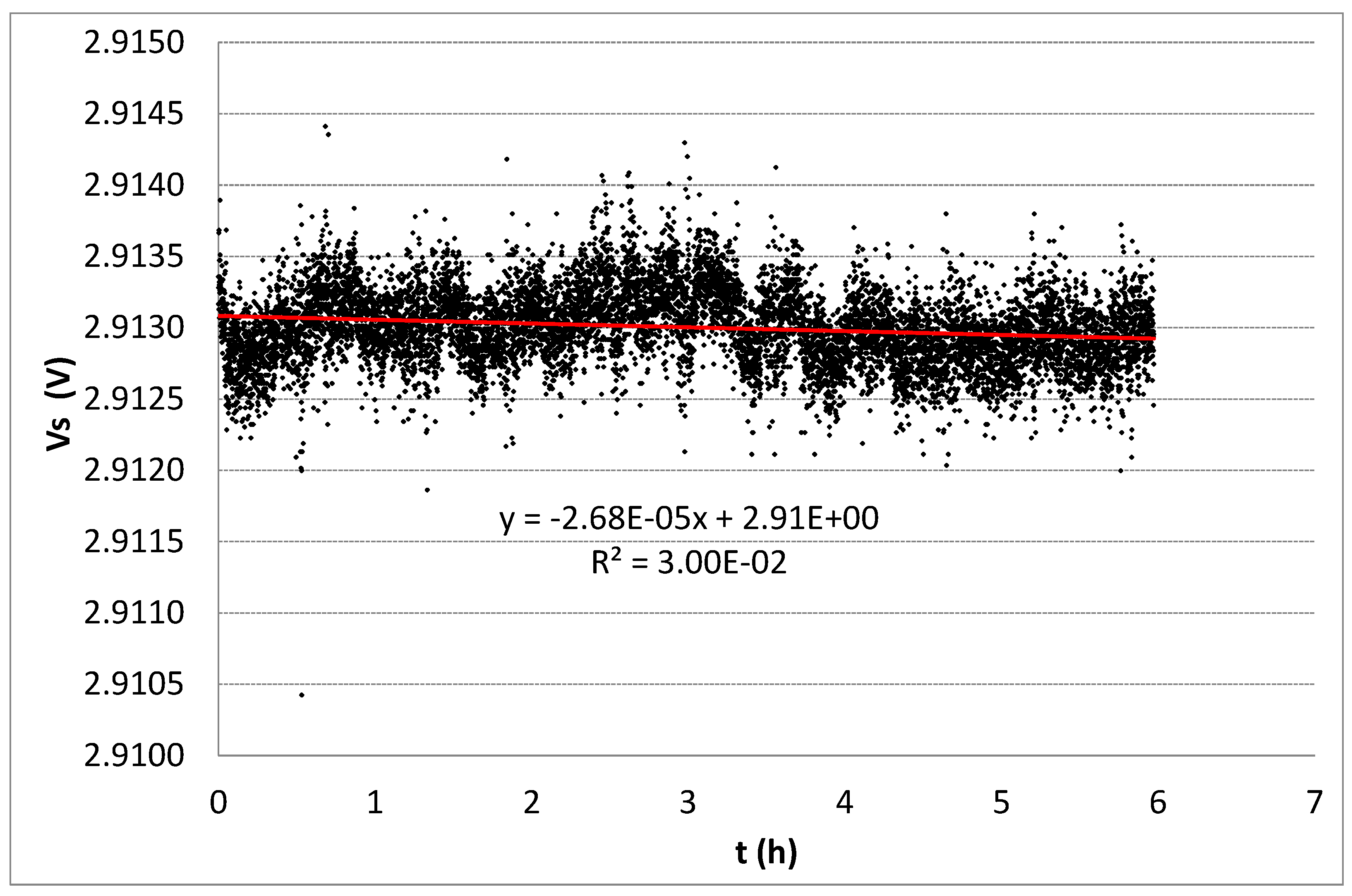

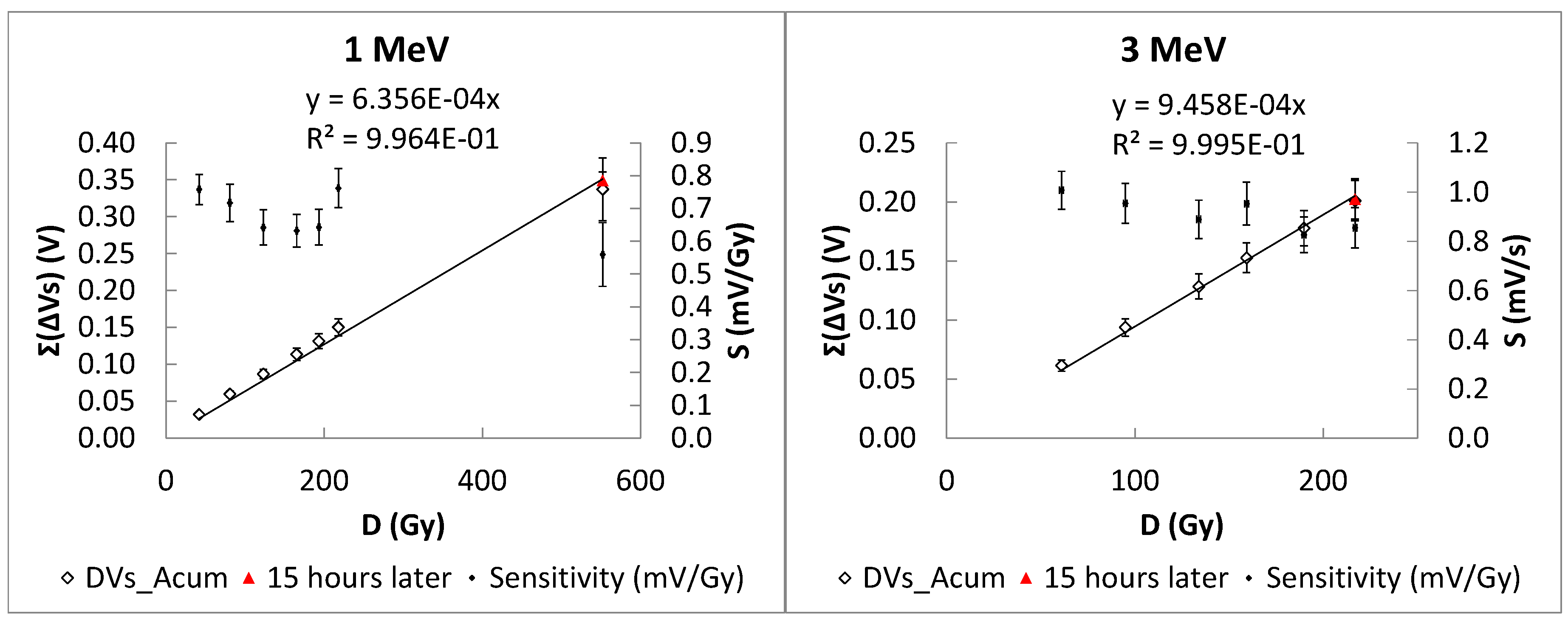

3.2. Fading

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOSFET | Metal Oxide Field Effect Transistor |

| RADFET | RADiation FET |

| CNA | Accelerator National Centre |

| PSI | Paul Scherrer Institute |

| PIF | Proton Irradiation Facility |

References

- Bruzzi, M.; Nava, F.; Pini, S.; Russo, S. High quality SiC applications in radiation dosimetry. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2001, 184, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.R.; McNulty, P.J.; Beauvais, W.J.; Reed, R.A.; Stassinopoulos, E.G. Solid state microdosimeter for radiation monitoring in spacecraft and avionics. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1994, 41, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, P.; Quinn, A.; Loo, K.; Lerch, M.; Petasecca, M.; Wong, J.; Hardcastle, N.; Carolan, M.; McNamara, J.; Cutajar, D.; et al. Review of four novel dosimeters developed for use in radiotherapy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2013, 444, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damulira, E.; Yusoff, M.N.S.; Omar, A.F.; Mohd Taib, N.H. A Review: Photonic Devices Used for Dosimetry in Medical Radiation. Sensors 2019, 19, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, N.I.; Nam, H.G.; Cha, K.H.; Lee, K.H.; Noh, S.J. Fabrication of silicon PIN diode as proton energy detector. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2006, 6, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, G.F. Radiation Detection and Measurement, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-13148-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bertuccio, G.; Puglisi, D.; Macera, D.; Di Liberto, R.; Lamborizio, M.; Mantovani, L. Silicon Carbide Detectors for in vivo Dosimetry. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2014, 61, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A.B. MOSFET Dosimetry on Modern Radiation Oncology Modalities. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 2002, 101, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharanidharan, G.; Manigandan, D.; Devan, K.; Subramani, V.; Gopishankar, N.; Ganesh, T.; Joshi, R.; Rath, G.; Velmurugan, J.; Aruna, P.; et al. Characterization of responses and comparison of calibration factor for commercial MOSFET detectors. Med. Dosim. 2005, 30, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksic, A.; Ristic, G.; Pejovic, M.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Sudre, C.; Lane, W. Gamma-ray irradiation and post-irradiation responses of high dose range RADFETs. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2002, 49, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjelković, M.S.; Ristić, G.S.; Jakšić, A.B. Using RADFET for the real-time measurement of gamma radiation dose rate. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2015, 26, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, M.; Beck, P.; Jaksic, A. Investigation of the Energy Response of RADFET for High Energy Photons, Electrons, Protons, and Neutrons. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2009, 56, 3387–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Assessment of high-k gate stacked In2 O5 Sn gate recessed channel MOSFET for x-ray radiation reliability. Eng. Res. Express 2020, 2, 035017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat, E.; Martínez-Domingo, C.; Fleta, C.; Mas-Torrent, M.; Lozano, M. Exploration of alternative gate dielectric materials for RADFET sensors. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2025, 566, 165775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaldo, S.; Zhang, E.X.; Zhao, S.E.; Putcha, V.; Parvais, B.; Linten, D.; Gerardin, S.; Paccagnella, A.; Reed, R.A.; Schrimpf, R.D.; et al. Total-Ionizing-Dose Effects in InGaAs MOSFETs with High- k Gate Dielectrics and InP Substrates. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2020, 67, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, M.A.; Martínez-García, M.S.; Guirado, D.; Banqueri, J.; Palma, A.J. Dose verification system based on MOS transistor for real-time measurement. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2016, 247, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes-Siedle, A.; Ravotti, F.; Glaser, M. The Dosimetric Performance of RADFETs in Radiation Test Beams. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Radiation Effects Data Workshop, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–27 July 2007; IEEE: Honolulu, HI, USA; pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pejović, M.M. Dose response, radiation sensitivity and signal fading of p-channel MOSFETs (RADFETs) irradiated up to 50 Gy with 60Co. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2015, 104, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Wang, C. Radiation and Annealing Effects on GaN MOSFETs Irradiated by 1 MeV Electrons. Electronics 2022, 11, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.; Ralston, A.; Suchowerska, N. Clinical application of the OneDoseTM Patient Dosimetry System for total body irradiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005, 50, 5909–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, G.P.; Mann, G.G.; Pursley, J.A.; Espenhahn, E.T.; Fraisse, C.; Godfrey, D.J.; Oldham, M.; Carrea, T.B.; Bolick, N.; Scarantino, C.W. An Implantable MOSFET Dosimeter for the Measurement of Radiation Dose in Tissue During Cancer Therapy. IEEE Sens. J. 2008, 8, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfiky, D.; Abd-Rabou, A.S.; Akah, H.; Mahmoud, A.; Ernest, K.; Mohamed, A.; Ali, A.M.; Elshorbagy, A.; Mohamed, S.; Bayoumi, A.M. Development and Fabrication of MOSFET-Based Radiation Dosimeter (RadFET) for Enhanced Performance in Space Missions. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 39, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, G.S.; Vasović, N.D.; Kovačević, M.; Jakšić, A.B. The sensitivity of 100 nm RADFETs with zero gate bias up to dose of 230 Gy(Si). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2011, 269, 2703–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksic, A.; Kimoto, Y.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Hajdas, W. RADFET Response to Proton Irradiation Under Different Biasing Configurations. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2006, 53, 2004–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, R.; Nishio, T.; Miyagishi, T.; Hirano, E.; Hotta, K.; Kawashima, M.; Ogino, T. Experimental evaluation of a MOSFET dosimeter for proton dose measurements. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, 6077–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, J.A.; Ruiz-García, I.; Martín-Holgado, P.; Romero-Maestre, A.; Anguiano, M.; Vila, R.; Carvajal, M.A. General Purpose Transistor Characterized as Dosimetry Sensor of Proton Beams. Sensors 2023, 23, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datasheet RADFET-VT06 (rev.2202/04). Available online: https://www.varadis.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/VT06-Datasheet_rev2p2.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Peng, C.; Chen, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, F.; Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Ding, L.; Guo, X. Low-energy proton-induced single event effect in NAND flash memories. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2020, 969, 164064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CNA | PIF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run | 1 MeV | 2 MeV | 3 MeV | 150 MeV | 230 MeV |

| 1 | 42.2 | 29.3 | 61.0 | 10.03 | 10.08 |

| 2 | 80.9 | 69.8 | 94.9 | 20.09 | 20.09 |

| 3 | 123.1 | 110.3 | 133.9 | 30.16 | 30.14 |

| 4 | 165.3 | 148.6 | 159.3 | 80.24 | 80.19 |

| 5 | 193.4 | 186.9 | 189.8 | 130.24 | 130.2 |

| 6 | 218.0 | 211.7 | 216.9 | -- | -- |

| 7 | 552.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| DUTs in D.M. | #1.1,…,#1.5 | #2.1,...,#2.5 | #3.1,...,#3.5 | #150.1, #150.2 | #230.1, #230.2 |

| DUTs in C.M. | #1.6 | #2.6 | #3.6 | -- | -- |

| Sample | S (mV/Gy) | ΔS (mV/Gy) | R2 | Sample | S (mV/Gy) | ΔS (mV/Gy) | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 MeV | #1.1 | 0.729 | 0.006 | 0.9996 | 3 MeV | #3.1 | 1.038 | 0.010 | 0.9995 |

| #1.2 | 0.633 | 0.007 | 0.9994 | #3.2 | 0.868 | 0.010 | 0.9994 | ||

| #1.3 | 0.721 | 0.006 | 0.9997 | #3.3 | 0.967 | 0.009 | 0.9996 | ||

| #1.4 | 0.637 | 0.008 | 0.9993 | #3.4 | 0.860 | 0.009 | 0.9994 | ||

| #1.5 | 0.737 | 0.007 | 0.9995 | #3.5 | 0.996 | 0.008 | 0.9997 | ||

| #1.6 | 0.375 | 0.003 | 0.9996 | #3.6 | 0.568 | 0.009 | 0.9989 | ||

| Avg | 0.69 | 0.05 | -- | Avg | 0.95 | 0.08 | -- | ||

| Global | 0.691 | 0.007 | 0.9995 | Global | 0.946 | 0.009 | 0.9995 | ||

| 2 MeV | #2.1 | 0.865 | 0.005 | 0.9998 | 150 MeV | #150.1 | 1.109 | 0.023 | 0.9983 |

| #2.2 | 0.738 | 0.005 | 0.9998 | #150.2 | 1.09 | 0.03 | 0.9960 | ||

| #2.3 | 0.824 | 0.005 | 0.9998 | Avg | 1.10 | 0.03 | -- | ||

| #2.4 | 0.732 | 0.005 | 0.9998 | Global | 1.10 | 0.03 | 0.9974 | ||

| #2.5 | 0.807 | 0.005 | 0.9998 | 230 MeV | #230.1 | 1.20 | 0.03 | 0.9981 | |

| #2.6 | 0.596 | 0.038 | 0.9804 | #230.2 | 1.089 | 0.021 | 0.9985 | ||

| Avg | 0.79 | 0.06 | -- | Avg | 1.14 | 0.02 | -- | ||

| Global | 0.793 | 0.005 | 0.9998 | Global | 1.143 | 0.023 | 0.9984 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moreno-Pérez, J.A.; Ruiz-García, I.; Duane, R.; Martín-Holgado, P.; Morvaj, L.; Vasovic, N.; Hajdas, W.; Morilla, Y.; Carvajal, M.A. Characterization of a 100 nm RADFET as a Proton Beam Detector. Sensors 2026, 26, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010202

Moreno-Pérez JA, Ruiz-García I, Duane R, Martín-Holgado P, Morvaj L, Vasovic N, Hajdas W, Morilla Y, Carvajal MA. Characterization of a 100 nm RADFET as a Proton Beam Detector. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010202

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Pérez, J. A., I. Ruiz-García, R. Duane, P. Martín-Holgado, L. Morvaj, N. Vasovic, W. Hajdas, Y. Morilla, and M. A. Carvajal. 2026. "Characterization of a 100 nm RADFET as a Proton Beam Detector" Sensors 26, no. 1: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010202

APA StyleMoreno-Pérez, J. A., Ruiz-García, I., Duane, R., Martín-Holgado, P., Morvaj, L., Vasovic, N., Hajdas, W., Morilla, Y., & Carvajal, M. A. (2026). Characterization of a 100 nm RADFET as a Proton Beam Detector. Sensors, 26(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010202