Design and Primary Investigations of a Double Ring Loop Antenna for Ice, Frost and Wildfire Detection in Early Warning Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- -

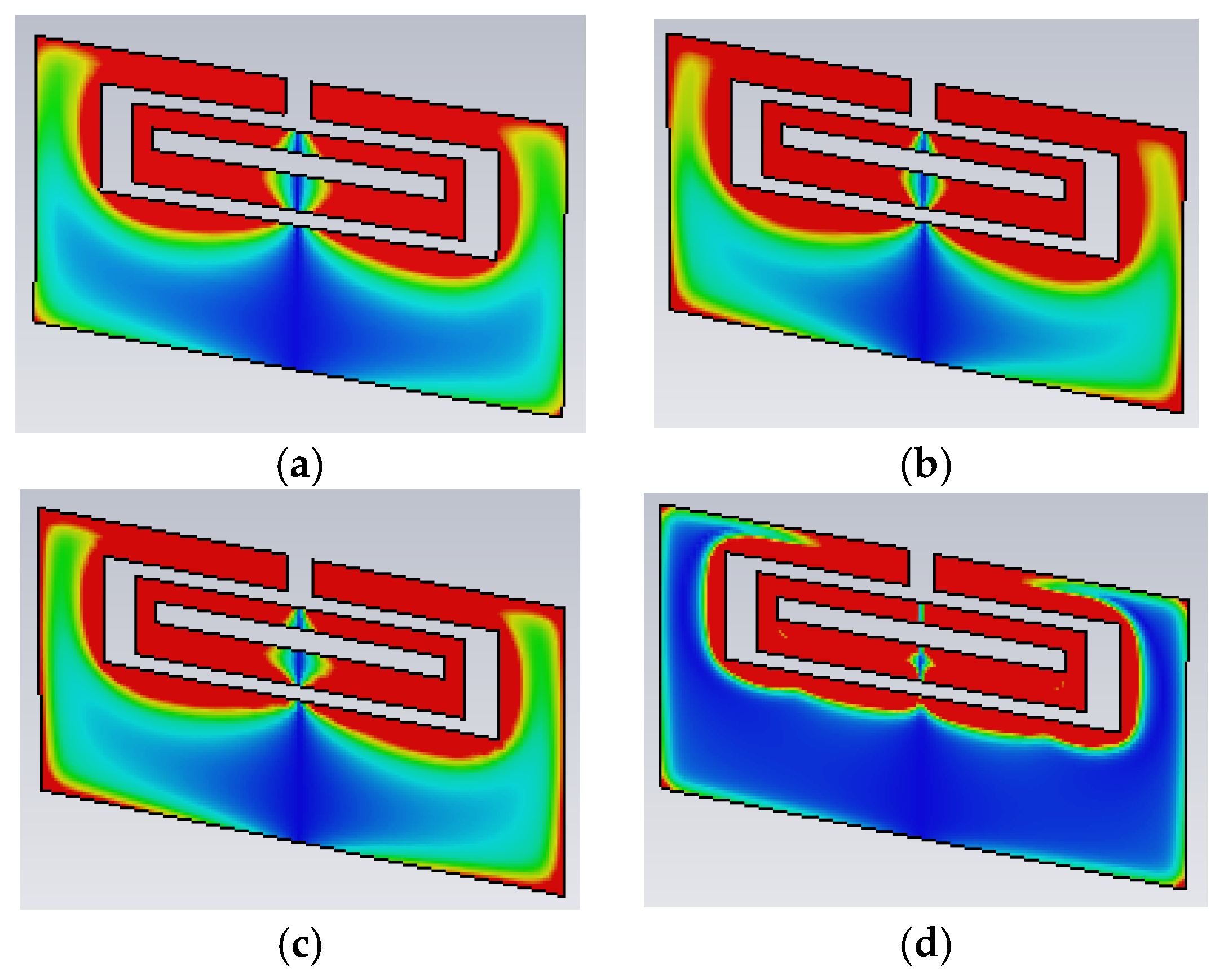

2. Structures and Concept

- Flexible materials were selected for the radiator due to their appealing features, including light weight and conformability [25].

- A loop structure was chosen and investigated in this work. This is because of its simplicity, making it well-suited for integration with flexible materials. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, loop antennas have been shown to be more sensitive than dipole antennas for ice detection applications [20].

- Resonance at around 2.49 GHz is within the 2.4–2.5 GHz Industrial, Scientific and Medical (ISM) band. This is an unlicensed band compatible with a wide range of wireless technologies, including sensor networks. The 2.45 GHz ISM band offers several advantages for early warning systems, such as moderate range and good penetration through foliage, rain and obstacles, which supports effective sensing in outdoor environments, particularly for frost, flood and wildfire detection. This band experiences lower atmospheric attenuation if compared with others at higher frequencies such as 5.6 GHz. This ensures a longer range of communication or more robust communication at shorter distances. Additionally, lower power consumption is usually associated with this band, which extends the lifetime of the battery-powered system. Also, many technologies have already been deployed utilizing this frequency band. Hence, real-time data collection and transmission can be supported for early warning systems utilizing the existing infrastructure [28].

3. Methodology and Methods

- Design the antenna using simulation software with reference to theoretical basics. Computer Simulation Technology (CST) is used for this work [34]. Hexahedral meshes and a time-domain solver are used. A simulation accuracy of −40 dB is set, ensuring excellent convergence and stability and providing reliable and accurate results. In addition, open boundaries are selected to minimize reflections, which provides more accurate near and far field results and allows for modeling free space radiation accurately. The simulations are also run with a port impedance of a pure 50 Ohms resistance, ensuring compatibility with a real standard value for practical connectors.

- Simulate the antenna in free space under the following conditions:

- -

- Without any loading materials;

- -

- With a layer of ice-mimicking material;

- -

- With a layer of frost-mimicking material;

- -

- With water-equivalent material at 40 °C and 50 °C.

- -

- Free space conditions, excluding other parameters such as humidity and smoke;

- -

- A steady material status during the overall duration of the simulation (i.e., it is not melted or starting to melt);

- -

- The layer of the MUT is uniform;

- -

- Fixed dielectric properties for materials over the entire simulation frequency range;

- -

- A perfect conducting radiator.

- Study and analyze the simulated results. The key parameters (−10 dB matching, variations in the resonant frequency, radiation efficiency, gain, radiation pattern, communication distance) are evaluated at this stage. The effect of the ice layer thickness on the antenna performance is also evaluated at this stage.

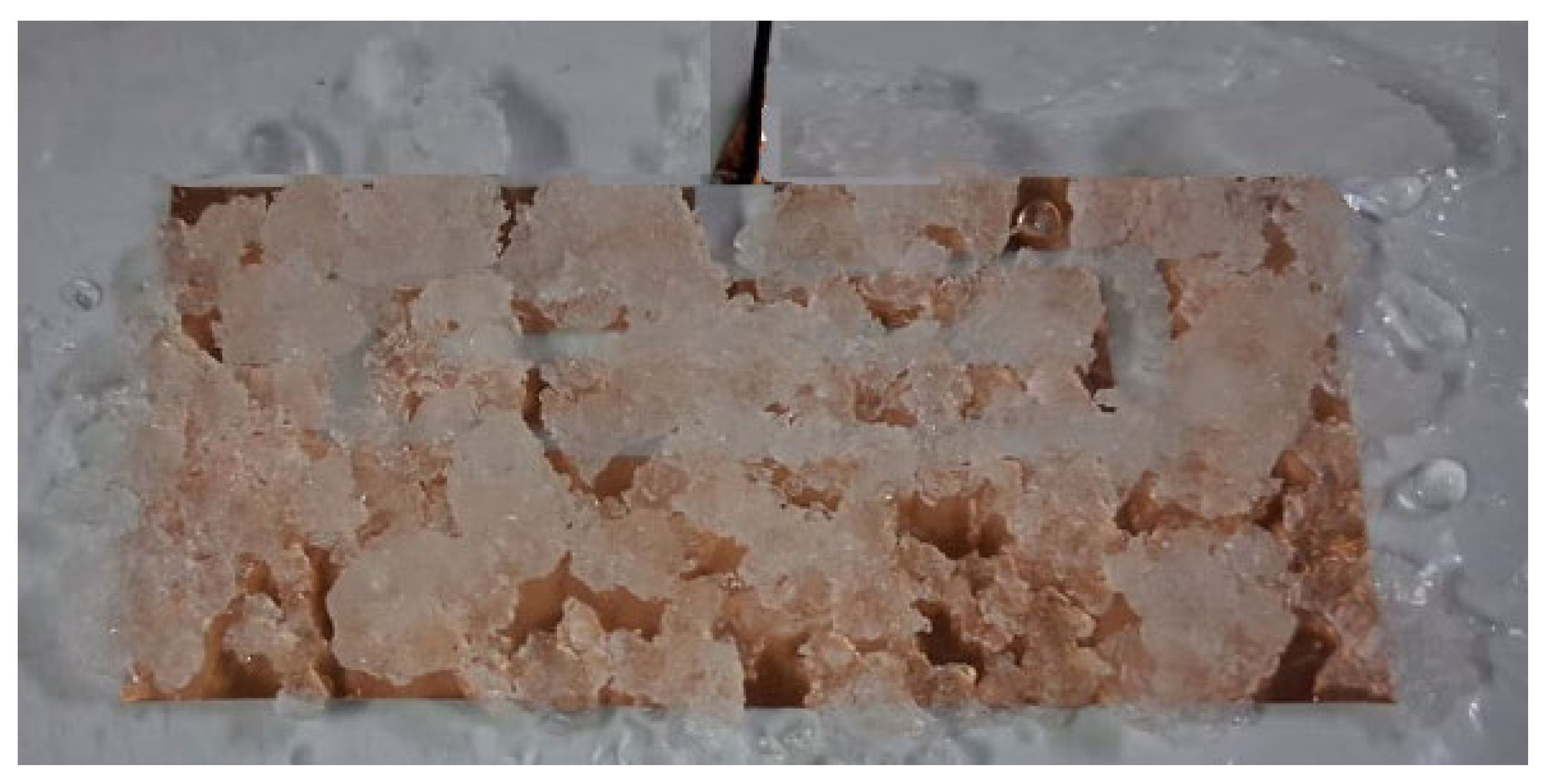

- Validate the antenna performance. The antenna is fabricated at this stage and its reflection coefficient along with its resonant frequency are measured for the case of ice. The same conditions of simulations are kept through measurements. The measured results are compared with the simulated ones to validate the performance.

4. Simulation Results

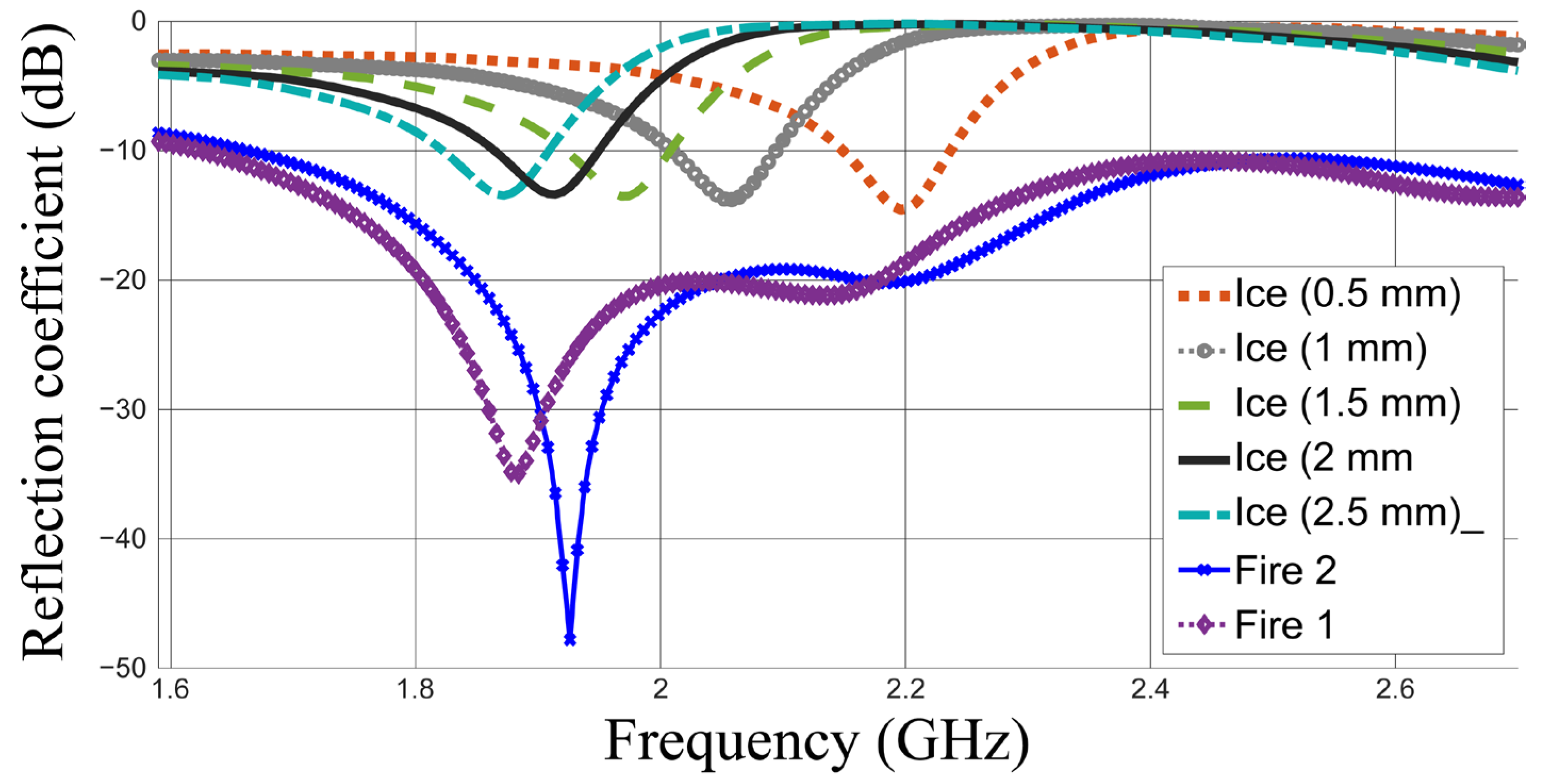

4.1. Sensing

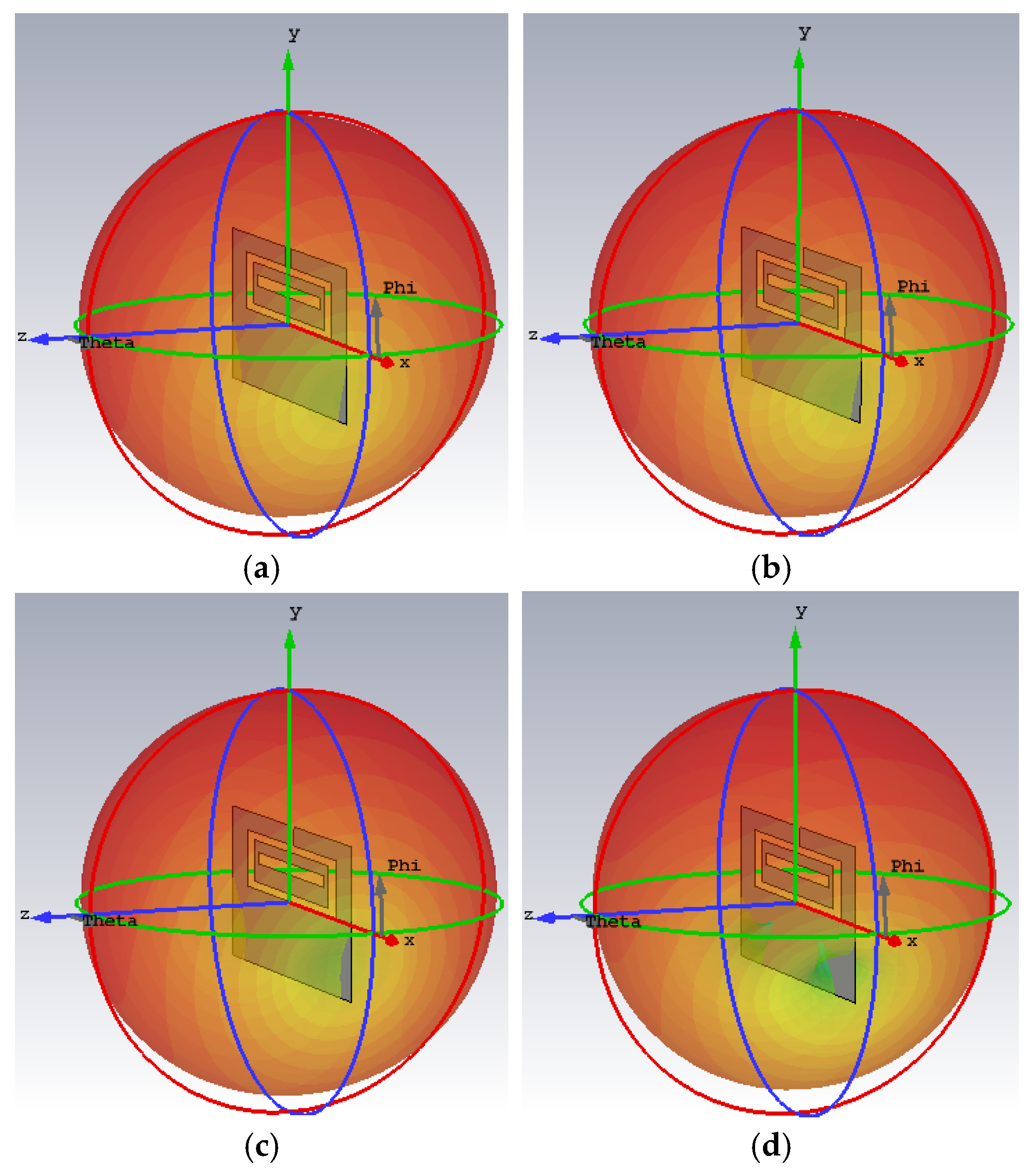

4.2. Data Transmission

5. Validation and Discussion

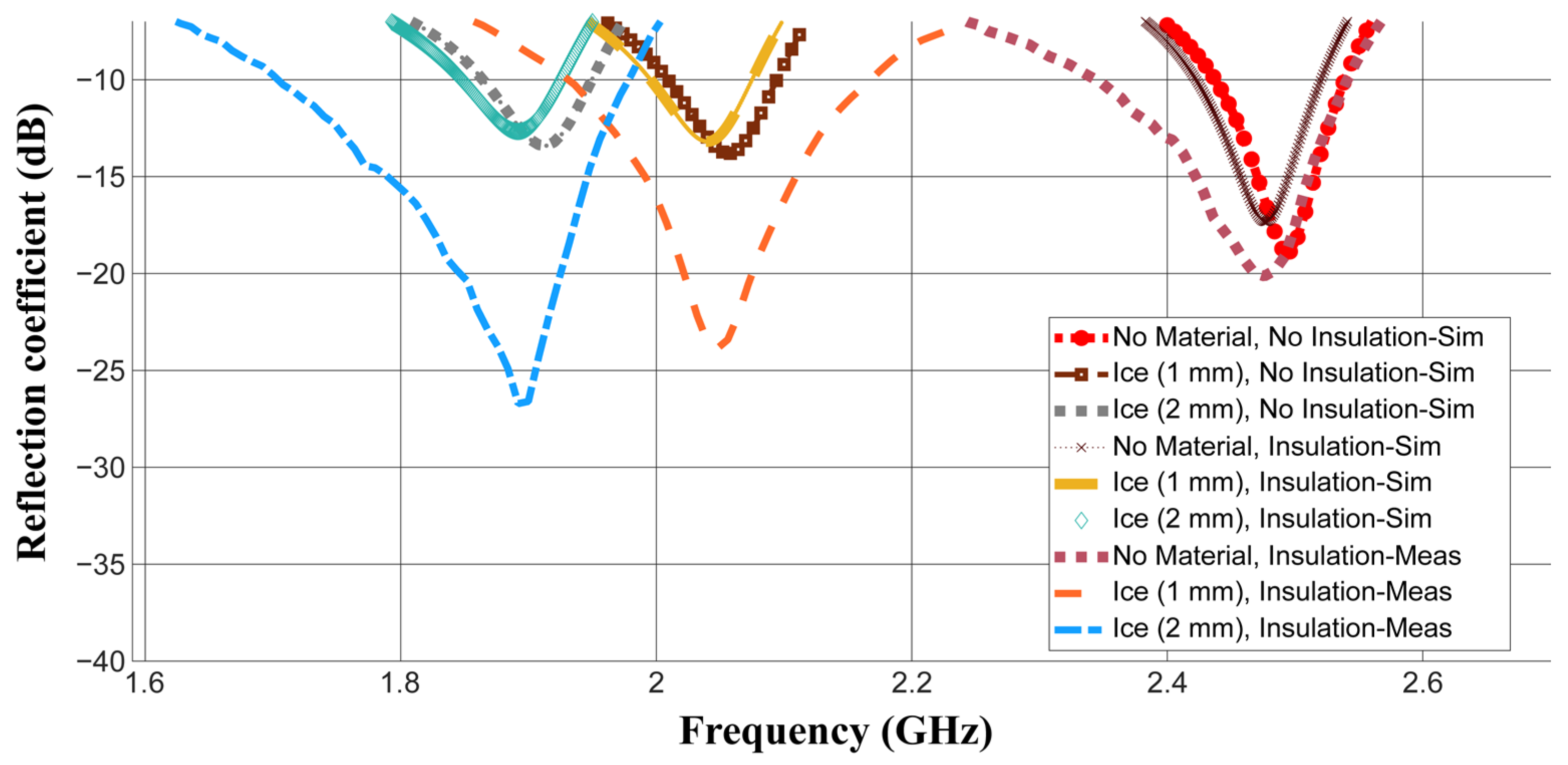

- -

- Simulated results without the insulation layer.

- -

- Simulated results with the insulation layer, taking into account its actual thickness and dielectric properties provided above.

- It involves a high sensitivity level combined with a relatively large gain compared to existing antennas of the same type operating at the same frequency.

- It proposes what is probably the first loop antenna proposed with a wide temperature detection range between 0 and 50 °C.

- It investigates and underscores the effect of multiple rings on the sensor loop antenna performance with the purpose of inspiring more optimized loop antenna structures for sensing applications in the future.

- It validates the robustness of flexible antennas for use in harsh environments, with applications in early warning systems and environmental monitoring.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

- Further investigations on other contributing parameters such as smoke for wildfire detection and humidity may be needed in the future. This is to model the actual environment more accurately.

- Further work should investigate other loop and ring structures in addition to possible coupling techniques. For example, multiple split rings instead of a single ring may be investigated. The capabilities of the internal ring and split rings in strengthening the near electric field and boosting the sensitivity level may be studied.

- Measurements of the radiation efficiency, gain and radiation pattern should be conducted.

- Measurements over longer periods of time involving variations in the status of the material under test, which may include ice melting and temperature variations, should be conducted.

- Measurements after integration in a prototype sensing system should be conducted.

- Calculation and estimation of a more accurate link budget taking actual data rates and channel capacity into consideration should be conducted.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alrawashdeh, R. A Cross-Shaped Slotted Patch Sensor Antenna for Ice and Frost Detection. Technologies 2025, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Antenna Sensors in Passive Wireless Sensing Systems. In Handbook of Antenna Technologies; Chen, Z., Liu, D., Nakano, H., Qing, X., Zwick, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, Z.U.; Bermak, A.; Wang, B. A Review of Microstrip Patch Antenna-Based Passive Sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, C.; Li, Y.; Tan, J.; Xuan, F.; Ling, X. Flexible Multimode Antenna Sensor with Strain and Humidity Sensing Capability for Structural Health Monitoring. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2022, 347, 113960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Chefena, M.; Rajo-Iglesias, E. Dual-Functional Communication and Sensing Antenna System. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ser, W. Robust Beam Pattern Synthesis for Antenna Arrays with Mutual Coupling Effect. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2011, 59, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shafai, L.; Isleifson, D.; Shafai, C. Split Ring Antennas and Their Application for Antenna Miniaturization. Sensors 2023, 23, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.-C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Hsu, P. Miniaturization of Slot Loop Antenna Using Split-Ring Resonators. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium (APSURSI), North Charleston, SC, USA, 1–5 June 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, K.; Guo, S.; Ye, J.; Saeed, N. Near-Field Integrated Sensing and Communications: Unlocking Potentials and Shaping the Future. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Signal, Information and Data Processing (ICSIDP), Zhuhai, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Albishi, A.M. A Novel Coupling Mechanism for CSRRs as Near-Field Dielectric Sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, A.S.; Pujiana, D.; Husni, N.L.; Amin, J.M.; Sitompul, C.R.; Taqwa, A.; Suroso; Soim, S. Robustness of Sensors Network in Environmental Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Applied Science and Technology (iCAST), Manado, Indonesia, 26–27 October 2018; pp. 515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Alieldin, A.; El-Agamy, A.F.; Mowafy, M.; El-Akhdar, A.M. A Dual Circularly Polarized Omnidirectional Antenna for Radar-Warning Receiver. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Telecommunications Conference (ITC-Egypt), Alexandria, Egypt, 13–15 July 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xuan, X.-W.; Zhao, W.-Y.; Nie, H.-K. An Implantable Antenna Sensor for Medical Applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 14035–14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Zhang, C.; Luo, J.; Liu, J.; Ren, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, R.; Feng, Q.; Chen, Y.Y.; et al. A Highly Sensitive and Miniaturized Wearable Antenna Based on MXene Films for Strain Sensing. Mater. Adv. 2022, 4, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheakh, D.N.; Mohamed, R.A.; Fahmy, O.M.; Ezzat, K.; Eldamak, A.R. Complete Breast Cancer Detection and Monitoring System by Using Microwave Textile-Based Antenna Sensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghlatoon, H.; Mirzavand, R.; Honari, M.M.; Mousavi, P. Sensor Antenna Transmitter System for Material Detection in Wireless-Sensor-Node Applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghiti, M.K.; El Gibari, M.; Rhallabi, A.; El Fallah Serghrouchni, A. Development and Optimization of Gas Sensors for Ammonia detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR), Belgrade, Serbia, 26–27 November 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, R.; Khorsand, K.; Zarifi, T.; Golovin, K.; Zarifi, M.H. Patch Antenna Sensor for Wireless Ice and Frost Detection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altakhaineh, A.T.; Alrawashdeh, R.; Zhou, J. Machine Learning-Aided Dual-Function Microfluidic SIW Sensor Antenna for Frost and Wildfire Detection Applications. Energies 2024, 17, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagih, M.; Shi, J. Toward the Optimal Antenna-Based Wireless Sensing Strategy: An Ice Sensing Case Study. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 2022, 3, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, R. A Wearable Finger-Ring Antenna for Smart-Home Internet of Things. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2024, 100, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-L.; Fusco, V.F.; Nakano, H. Circularly Polarized Open-Loop Antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2003, 51, 2475–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Tarawneh, A. A Triple Band Flexible Antenna Based on Asymmetric Spiral Split Rings Coupled to External Loop. Jordan J. Energy 2024, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, R.; Huang, Y.; Kod, M.; Sajak, A.A.B. A Broadband Flexible Implantable Loop Antenna with Complementary Split Ring Resonators. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2015, 14, 1506–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Flexible Wireless Antenna Sensor: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 3865–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayt, W.; Kemmerly, J.; Durbin, S. Engineering Circuit Analysis; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sedra, A.S.; Smith, K.C. Microelectronic Circuits, 8th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson Process Management. Impact of Weather on Smart Wireless Networks. 2010. Available online: https://www.emerson.com/documents/automation/white-paper-impact-of-weather-on-smart-wireless-networks-en-42650.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Boyle, K. Antennas: From Theory to Practice; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glen, J.W.; Paren, J.G. The Electrical Properties of Snow and Ice. J. Glaciol. 1975, 15, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, C. Microwave Permittivity of Dry Snow. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1996, 34, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, R.; Jain, R.; Sharma, K.S. Dielectric Properties of Water at Microwave Frequencies. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2015, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hufford, G. A Model for the Complex Permittivity of ice at Frequencies Below 1 THz. Int. J. Infrared Millim. Waves 1991, 12, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CST—Computer Simulation Technology. CST Studio Suite, Version 2024; Dassault Systèmes: Darmstadt, Germany, 2024.

- Alrawashdeh, R.S.; Alharazneh, F.; Alsarayreh, F.; Aladaileh, E. A Novel Flexible Cloud Shape Loop Antenna for Muscle Implantable Devices. Jordan J. Electr. Eng. 2019, 5, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrosemoli, E.; Zennaro, M. Link Budget Calculation, PowerPoint Presentation. Available online: https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Link-Budget-Calculation.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- RS PRO Copper Foil Shielding Tape 19 mm × 33 m Datasheet. Available online: https://docs.rs-online.com/c965/0900766b8170b009.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Fine Metals Corporation. Copper Foil. Available online: https://finemetalscorp.com/product/copper-foil/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Chao, H.-W.; Chen, H.-H.; Chang, T.-H. Measuring the Complex Permittivity of Plastics in Irregular Shapes. Polymers 2021, 13, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anritsu Corporation. Economy Vector Network Analyzer MS46322B. Available online: https://www.anritsu.com/en-us/test-measurement/products/ms46322b (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Anritsu ShockLine. ShockLine MS46122A/B, MS46131A, ME786xA, and MS46322A/B Series Vector Network Analyzer. In Calibration and Measurement Guide; Anritsu Company: Morgan Hill, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://dl.cdn-anritsu.com/en-us/test-measurement/files/Manuals/Measurement-Guide/10410-00336V.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Matzler, C.; Wegmuller, U. Dielectric Properties of Fresh-Water Ice at Microwave Frequencies. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1987, 20, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaccia, S.; Patty, C.H.L.; Thomas, N.; Pommerol, A. Experimental Study of Frost Detectability on Planetary Surfaces Using Multicolor Photometry and Polarimetry. Icarus 2023, 396, 115503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, B.; Mirshahidi, K.; Golovin, K.; Zarifi, M.H. Robust and sensitive frost and ice detection via planar microwave resonator sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 301, 126881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagih, M.; Shi, J. Complex-Impedance Dipole Antennas as RFID-Enabled Ice Monitors. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting (APS/URSI), Singapore, 4–10 December 2021; pp. 399–400. [Google Scholar]

| Material | Relative Permittivity | Conductivity (S/m) |

|---|---|---|

| ice | 3.2 | 1 × 10−5 |

| frost 1 | 1.5 | |

| frost 2 | 2 | |

| frost 3 | 2.5 | 1 × 10−5 |

| High temperature 40 °C (fire 1) | 71.7 | 1.59 |

| High temperature 50 °C (fire 2) | 67.7 | 1.59 |

| Case | Resonant Frequency | Gain in the Direction of Maximum Radiation (dBi) | Maximum Radiation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| without material | 2.49 | 2.83 | 98.7 |

| ice (0.5 mm) | 2.196 | 2.72 | 96.5 |

| Ice (1 mm) | 2.058 | 2.68 | 95.8 |

| ice (1.5 mm) | 1.968 | 2.672 | 95.96 |

| ice (2 mm) | 1.914 | 2.66 | 95.9 |

| ice (2.5 mm) | 1.872 | 2.652 | 95.8 |

| frost 1 | 2.358 | 2.76 | 97.7 |

| frost 2 | 2.25 | 2.714 | 97 |

| frost 3 | 2.16 | 2.7 | 96.55 |

| fire 1 | 1.884 | −8.27 | 6.5 |

| fire 2 | 1.926 | −8.423 | 6.67% |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| frequency | 2.49 | GHz | |

| 2.196 | |||

| 2.058 | |||

| 1.986 | |||

| 1.914 | |||

| 1.872 | |||

| 2.358 | |||

| 2.25 | |||

| 2.16 | |||

| 1.884 | |||

| 1.926 | |||

| input power | 20 | dBm | |

| receiver sensitivity | −89 | dBm | |

| transmitter antenna gain | 2.83 | dBi | |

| 2.72 | |||

| 2.68 | |||

| 2.672 | |||

| 2.66 | |||

| 2.652 | |||

| 2.76 | |||

| 2.714 | |||

| 2.7 | |||

| −8.27 | |||

| −8.423 | |||

| receiver antenna gain | 14 | dBi | |

| link margin | 10 | dB | |

| reference distance | 1 | m | |

| path loss exponent | 3 | --- | |

| cable loss | 2.76 | dB |

| Case | Distance (m) |

|---|---|

| without | 315.355 |

| ice—0.5 mm | 338.844 |

| ice—1 mm | 353.9786 |

| ice—1.5 mm | 364.754 |

| ice—2 mm | 370.936 |

| ice—2.5 mm | 375.84 |

| frost 1 | 323.594 |

| frost 2 | 334.426 |

| frost 3 | 343.8745 |

| fire 1 | 157.76 |

| fire 2 | 162.0317 |

| Frequency Range in GHz | Matching Level (S11) in dB | Case |

|---|---|---|

| >2.16 | −20 to −10 | frost |

| 2–2.15 | >−30 to −10 | ice |

| <2 | >−30 to −10 | ice |

| <2 | <−30 | wildfire |

| Ref. | Resonant Frequency (GHz) | Sensing Technique | Antenna Type | Gain (dBi) | Targeted Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 5.6 | resonant frequency | cross-slotted patch | ice: 3.52 frost: 4.052 | ice, frost and water detection |

| [5] | 2.45 (data transmission) 4.9 (sensing) | resonant frequency | modified monopole with a T-shape patch antenna | 3.5 not provided | ice and water detection |

| [18] | 2.45 | resonant frequency (shifts and amplitude) | T-slotted patch antenna | ice (4.3) water (4.9) | frost, ice and water detection |

| [19] | 5.4 | resonant frequency | substrate-integrated waveguide | ~5.2 | frost and wildfire detection |

| [20] | 2.4 | received signal strength | loop | −5: ice (1 mm) | ice thickness measurements |

| dipole | −3: ice (1 mm) | ||||

| [44] | 3.5 | resonant amplitude and transmission coefficient | split-ring resonator | not provided | ice detection |

| [45] | 915 | received signal strength | dipole | not provided | ice detection |

| This work | 2.45 | resonant frequency and matching level | flexible loop | frost: 2.76 ice: 2.72 wildfire: −8.27 | frost, ice and wildfire detection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alrawashdeh, R. Design and Primary Investigations of a Double Ring Loop Antenna for Ice, Frost and Wildfire Detection in Early Warning Systems. Sensors 2026, 26, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010155

Alrawashdeh R. Design and Primary Investigations of a Double Ring Loop Antenna for Ice, Frost and Wildfire Detection in Early Warning Systems. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010155

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrawashdeh, Rula. 2026. "Design and Primary Investigations of a Double Ring Loop Antenna for Ice, Frost and Wildfire Detection in Early Warning Systems" Sensors 26, no. 1: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010155

APA StyleAlrawashdeh, R. (2026). Design and Primary Investigations of a Double Ring Loop Antenna for Ice, Frost and Wildfire Detection in Early Warning Systems. Sensors, 26(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010155