Approach and Fork Insertion to Target Pallet Based on Image Measurement Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

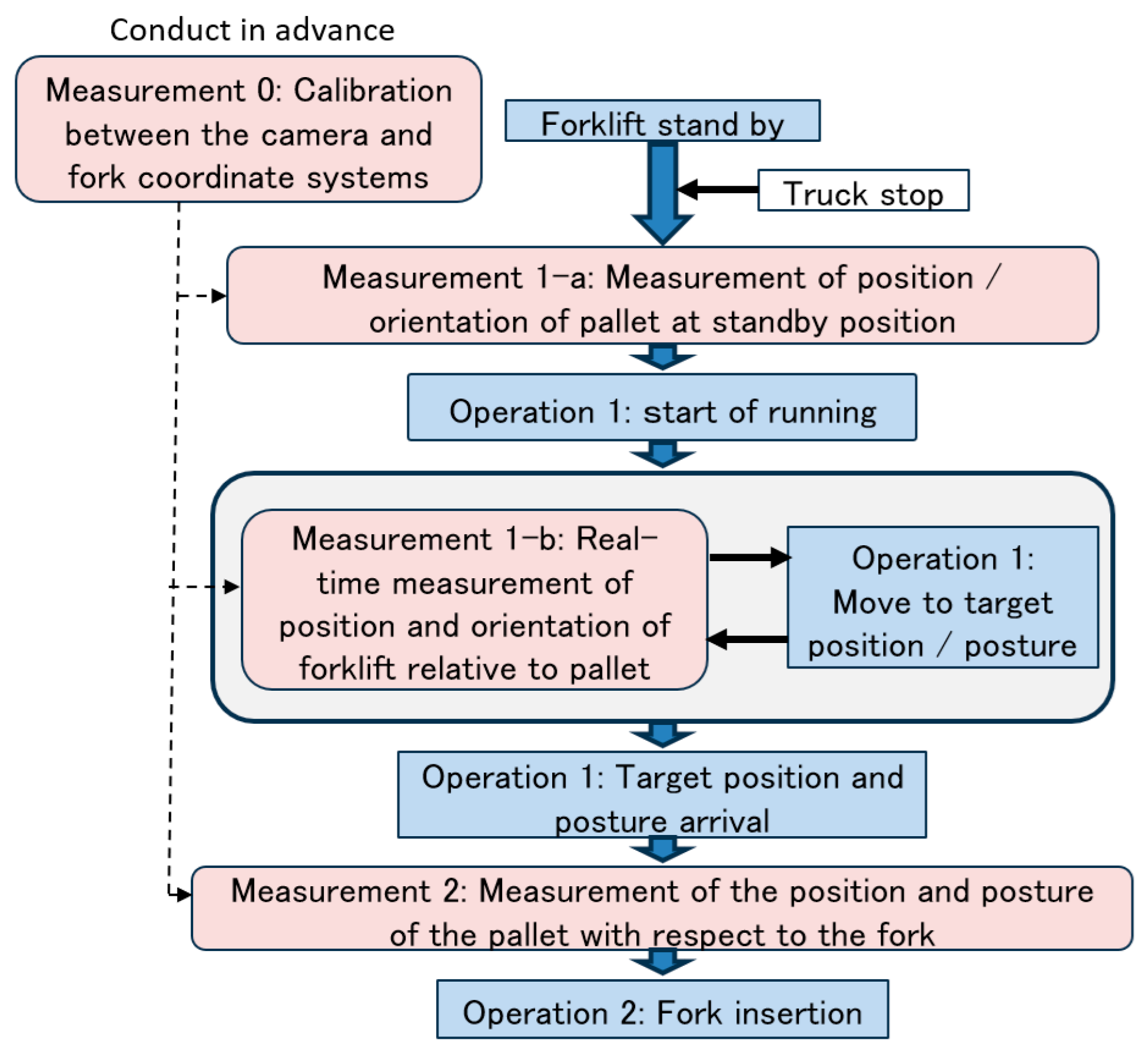

- Movement of the forklift from the standby position to the front of the pallet loaded on the truck that has arrived.

- Adjustment of the fork position and posture, and forward movement of the forklift.

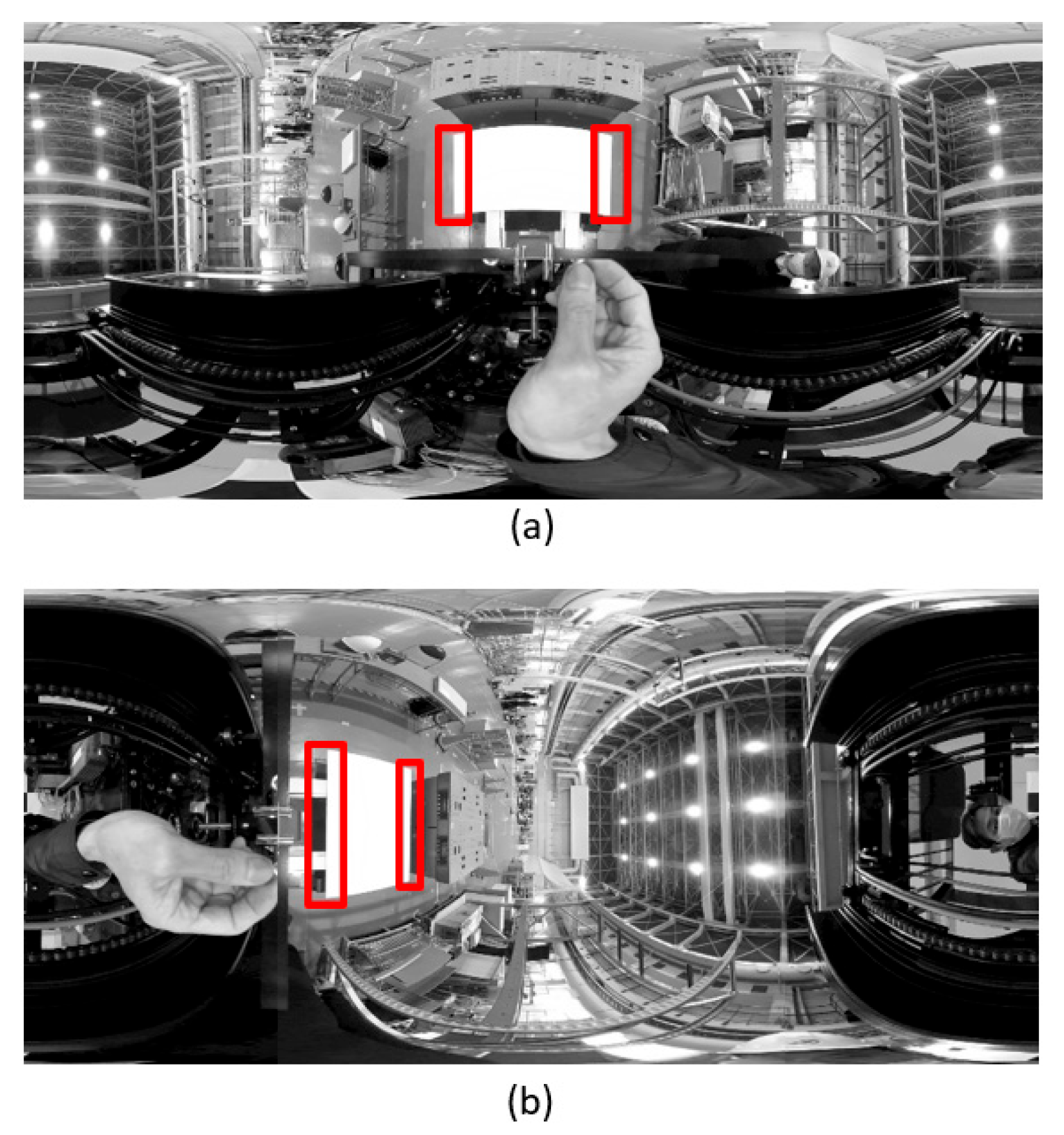

2. Related Works

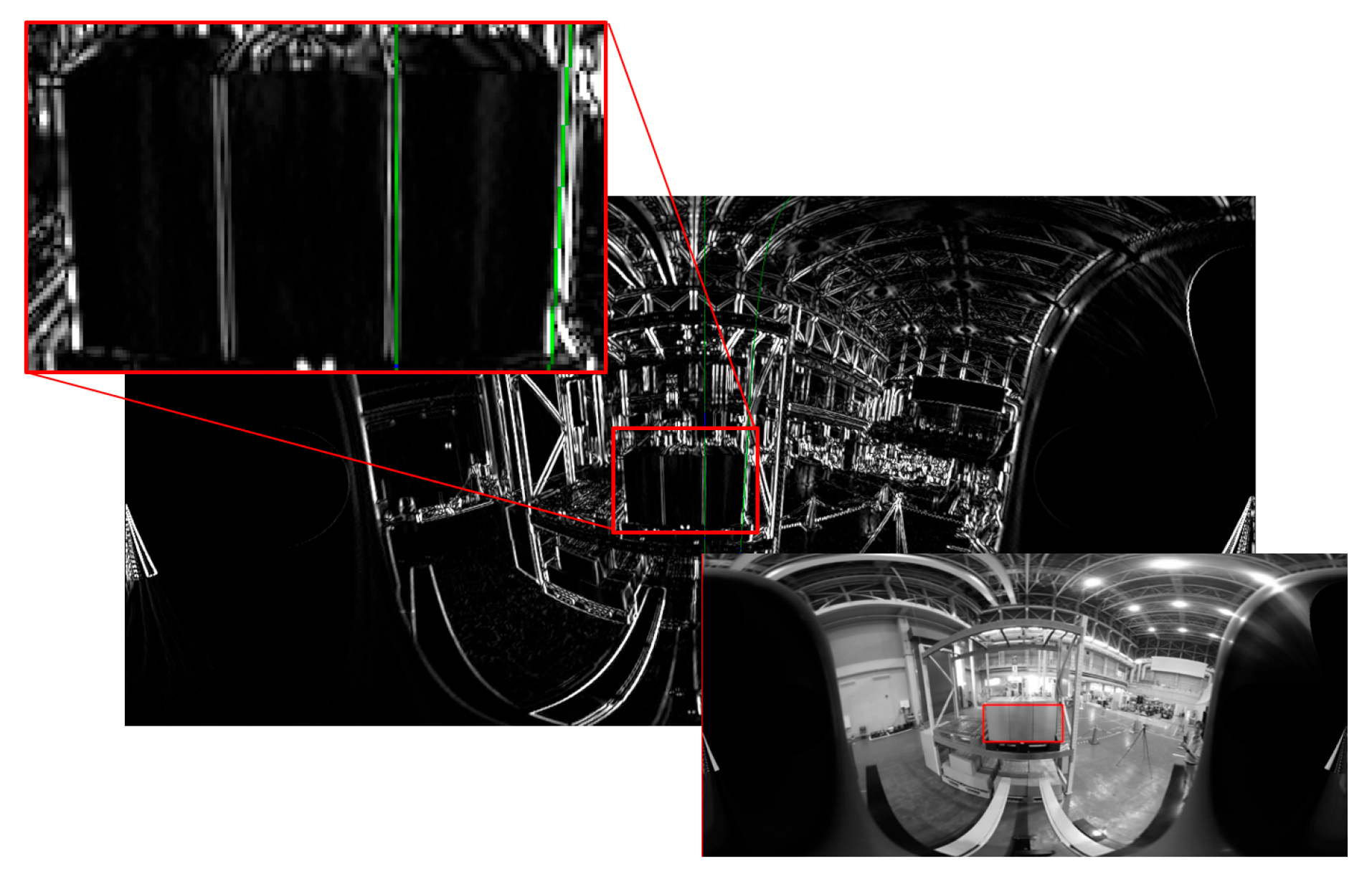

3. Overview of Wide-Field Image-Processing Methods

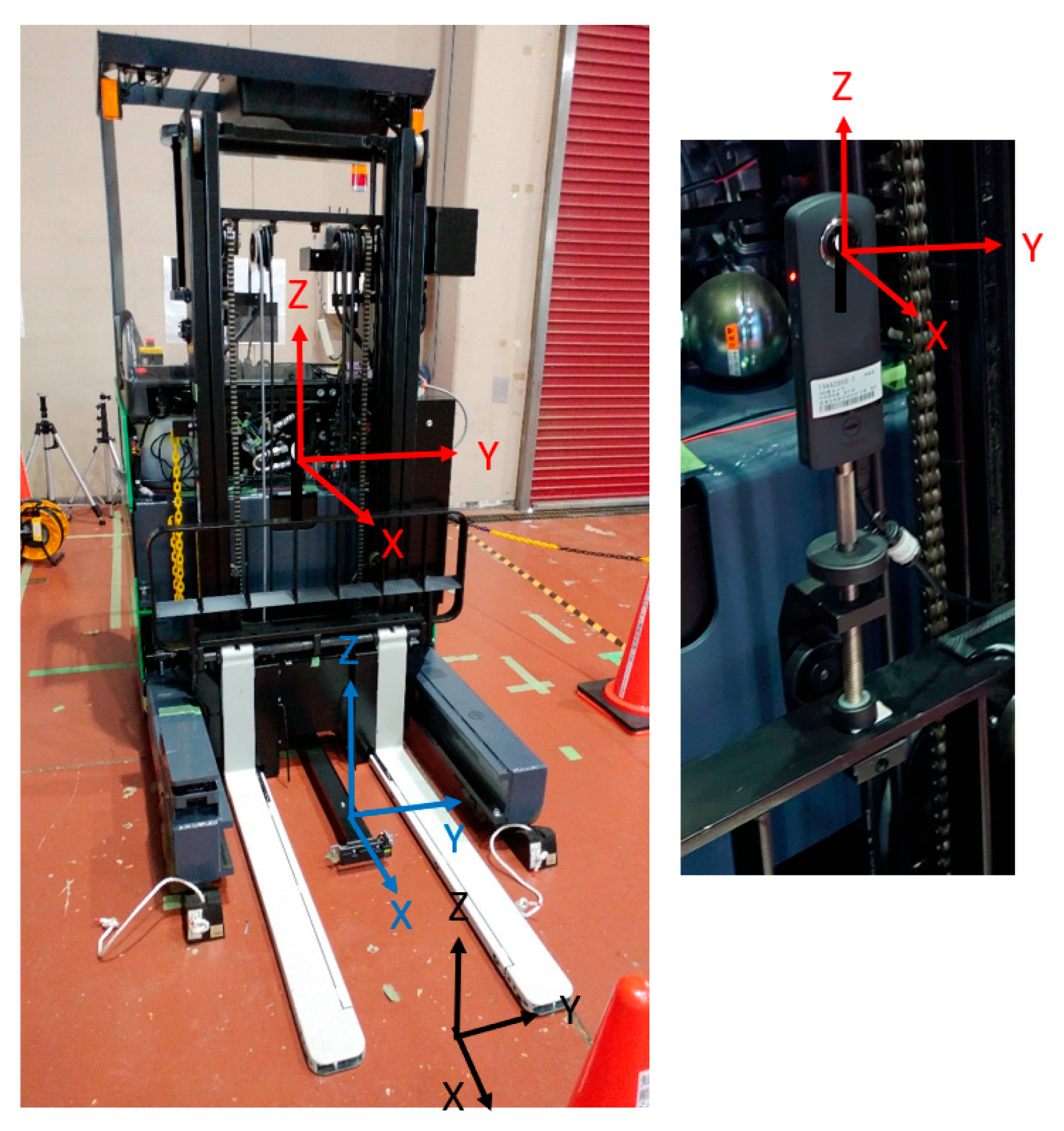

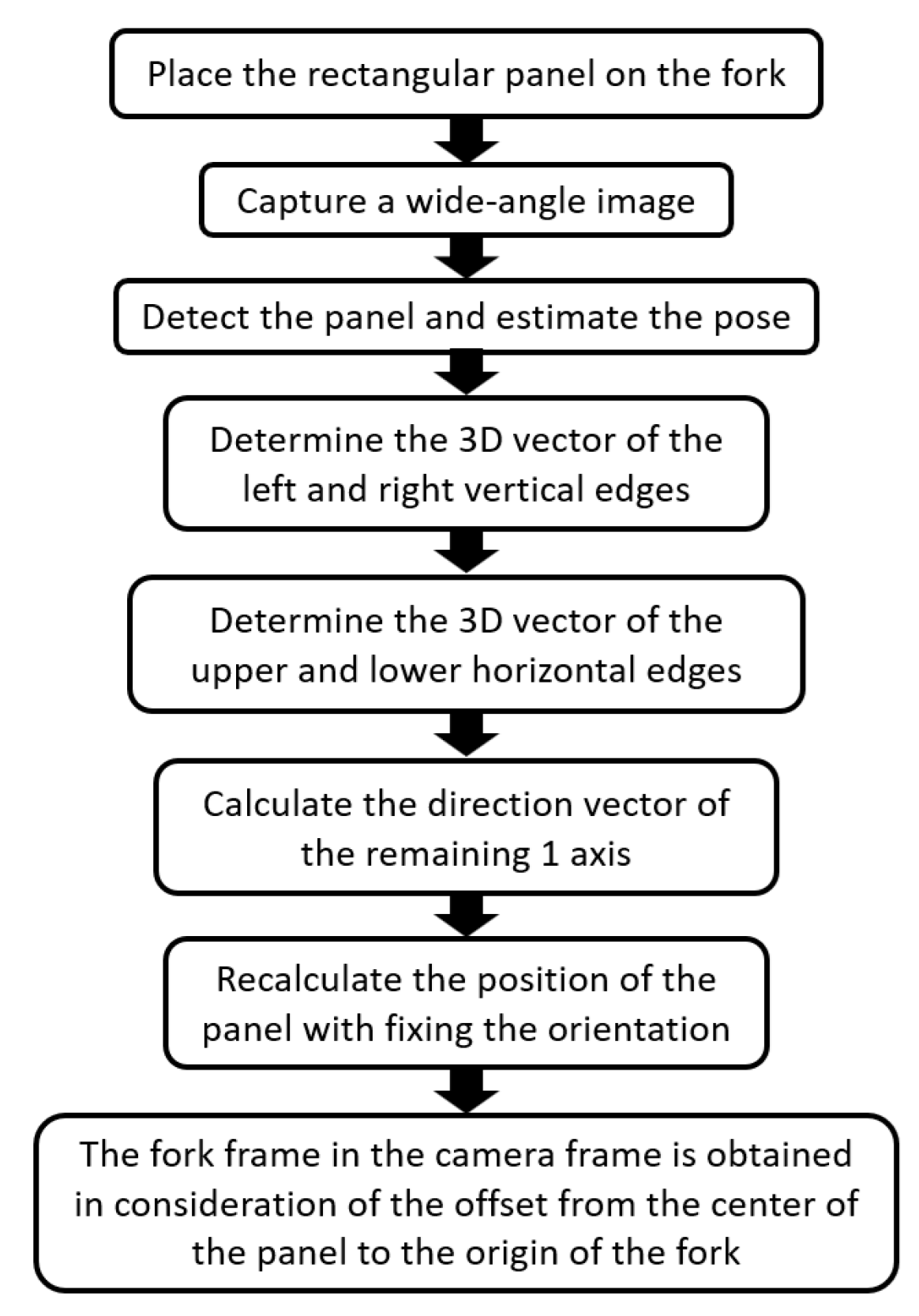

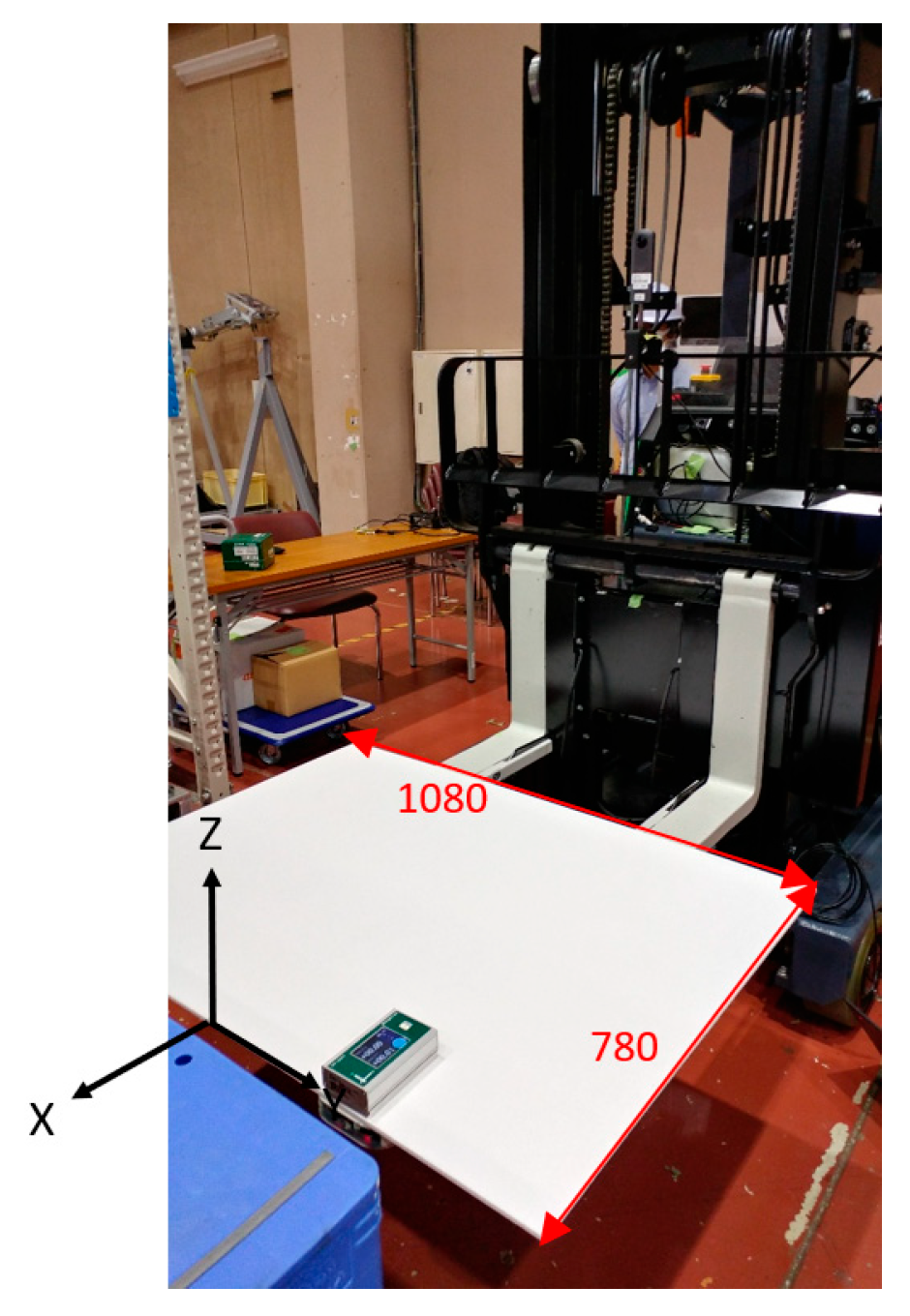

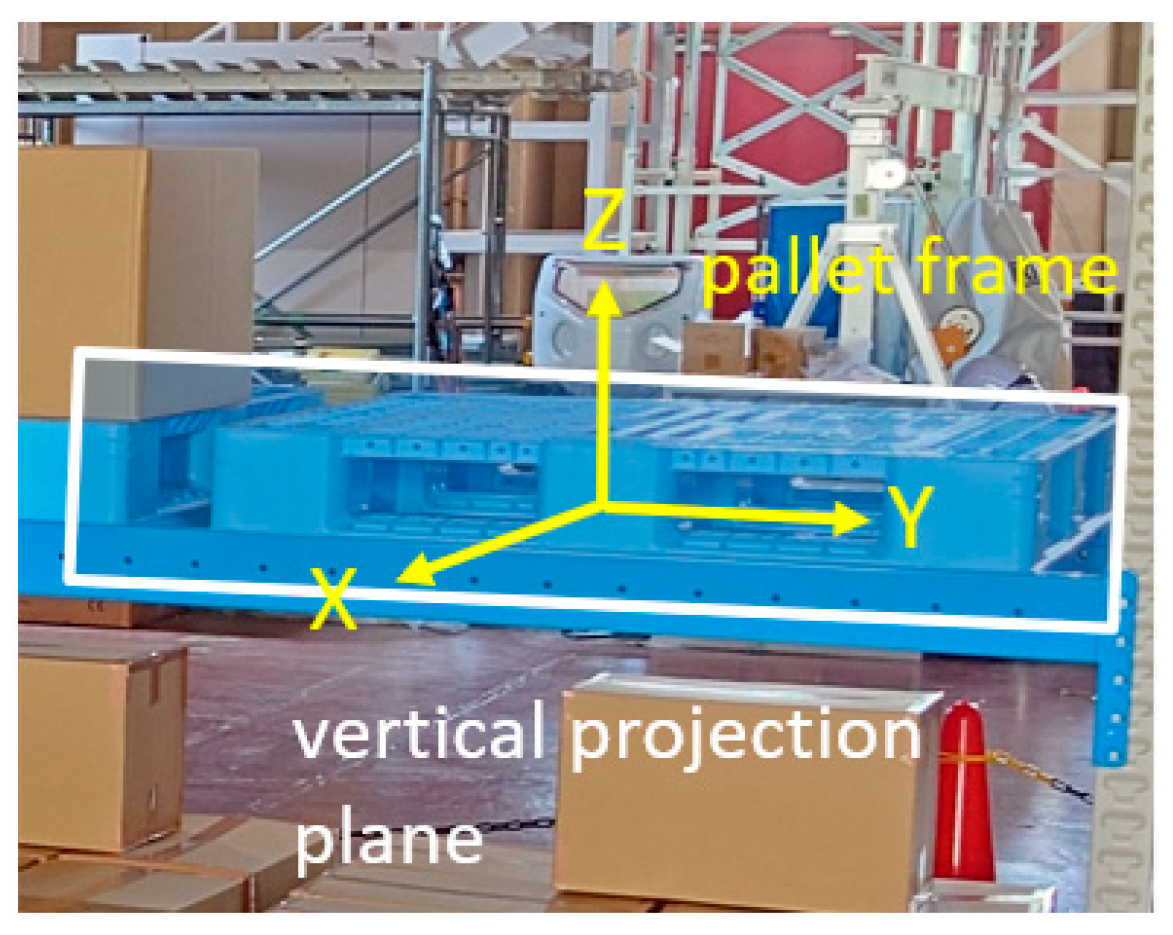

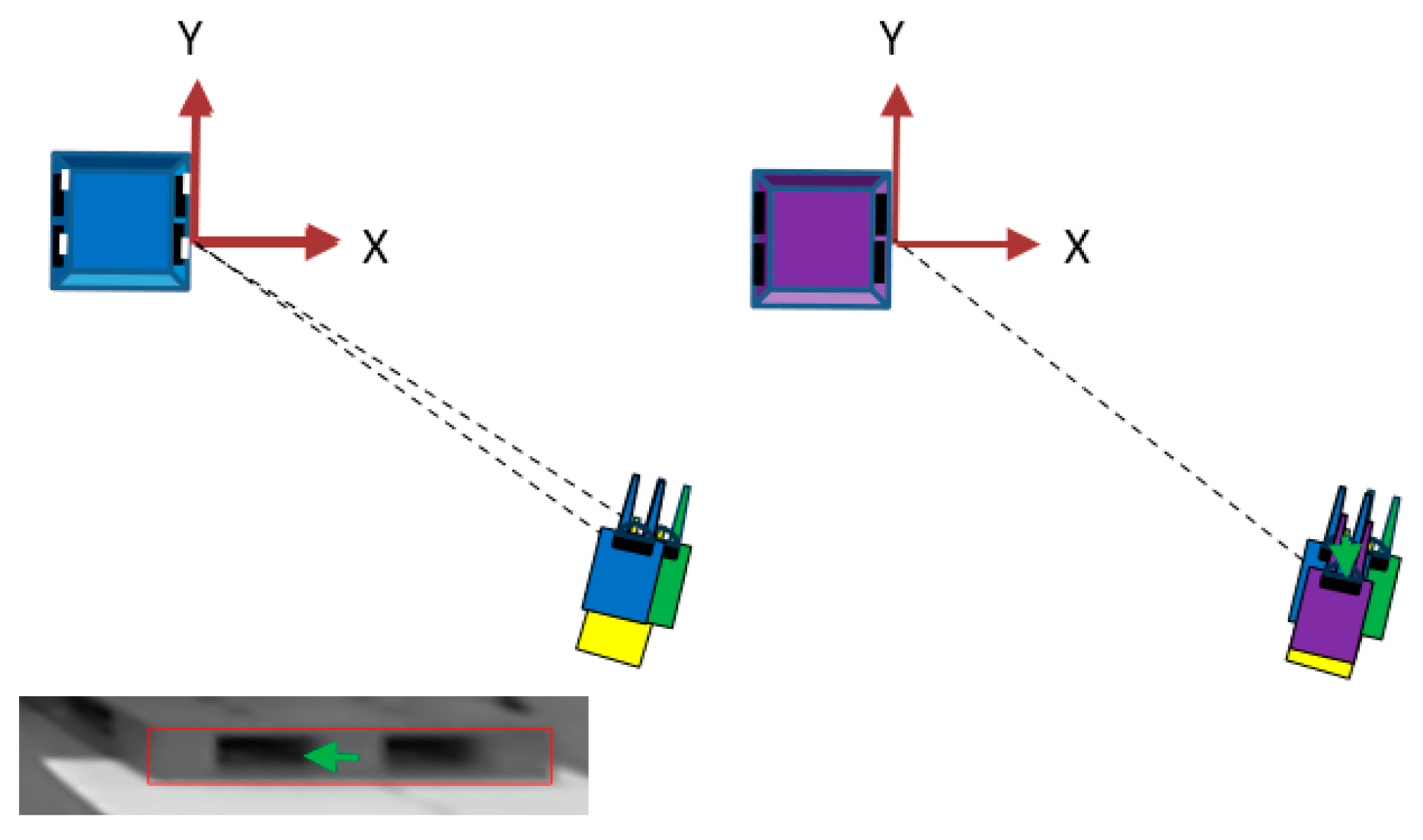

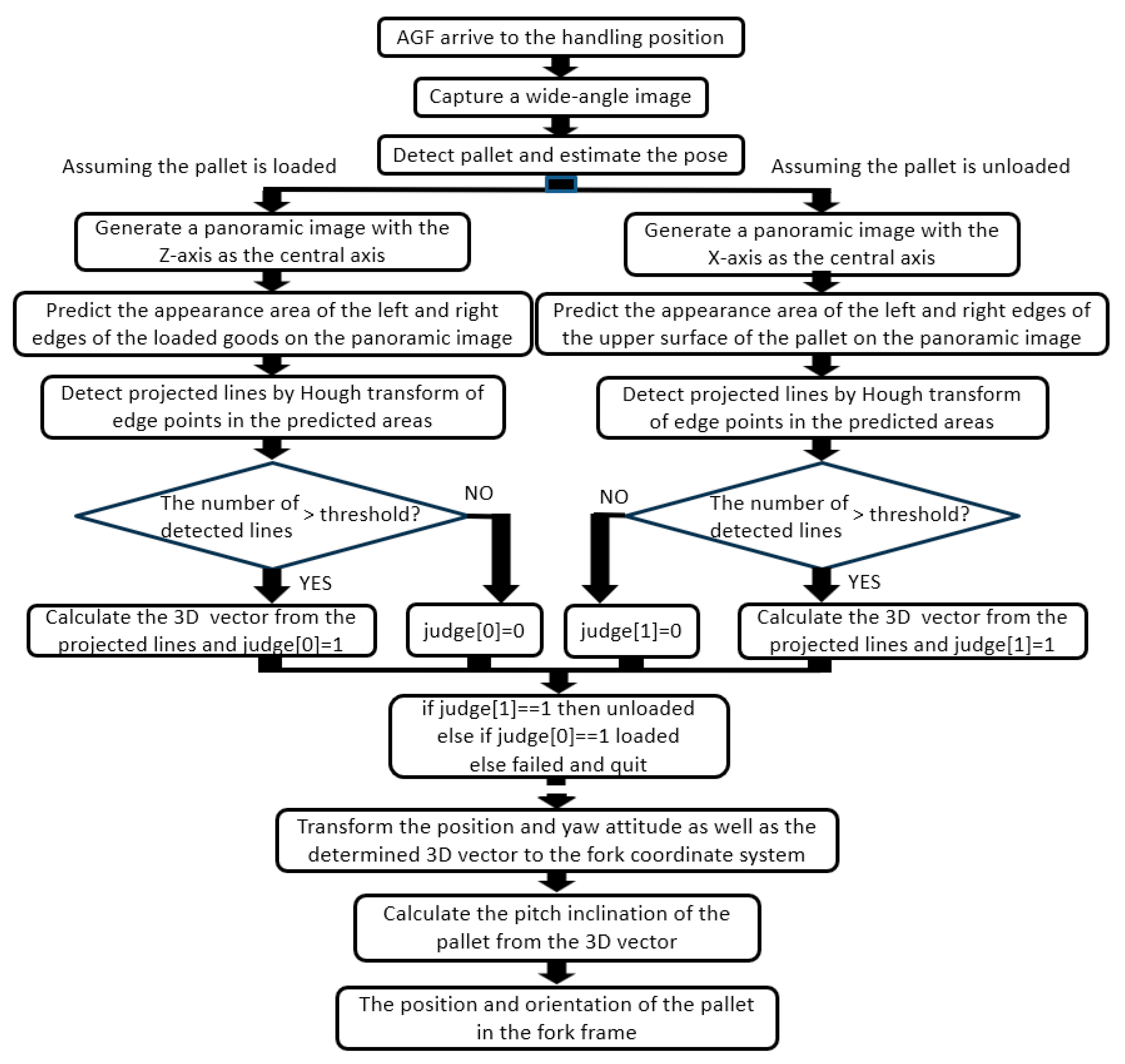

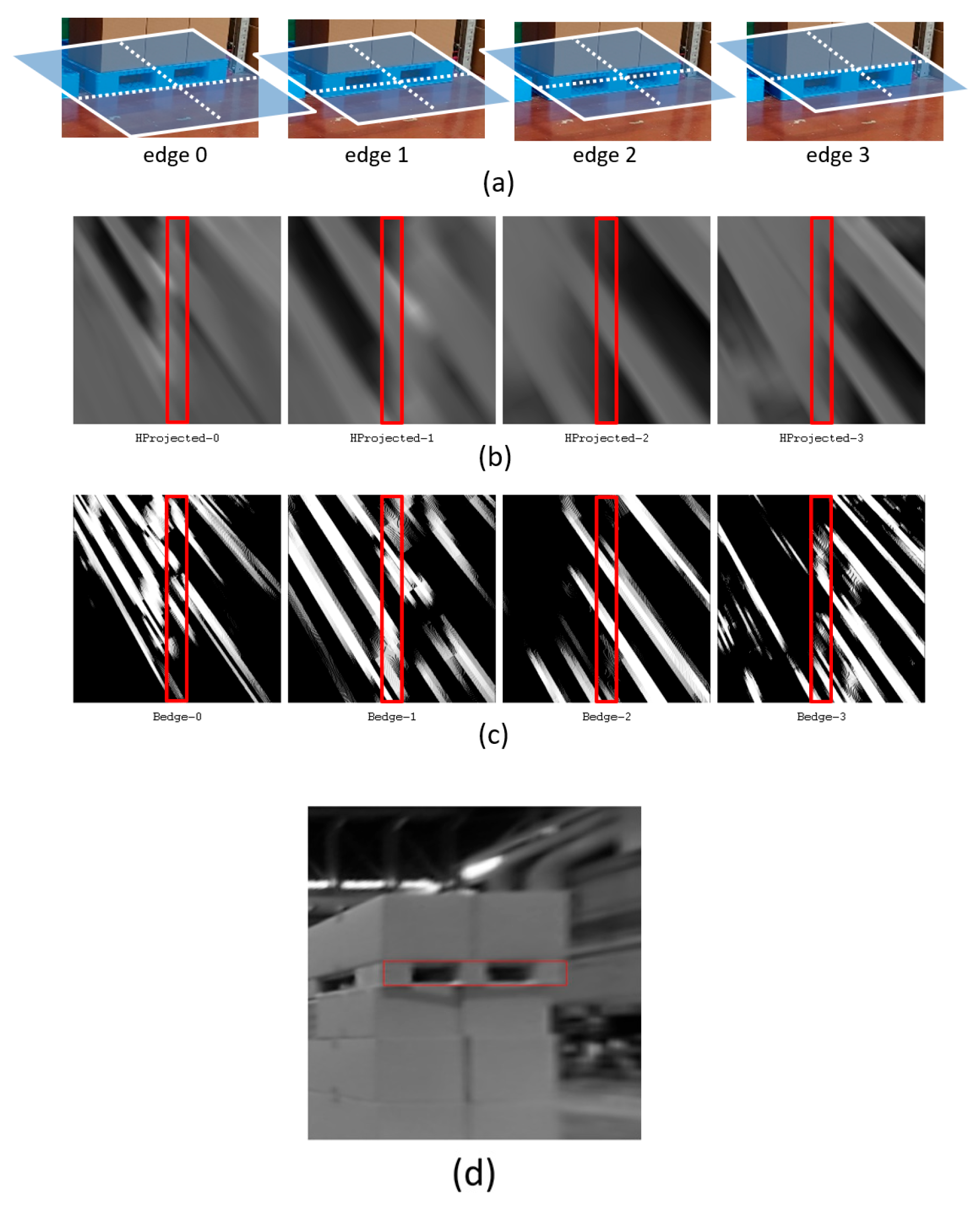

3.1. Overview of [Measurement 0]

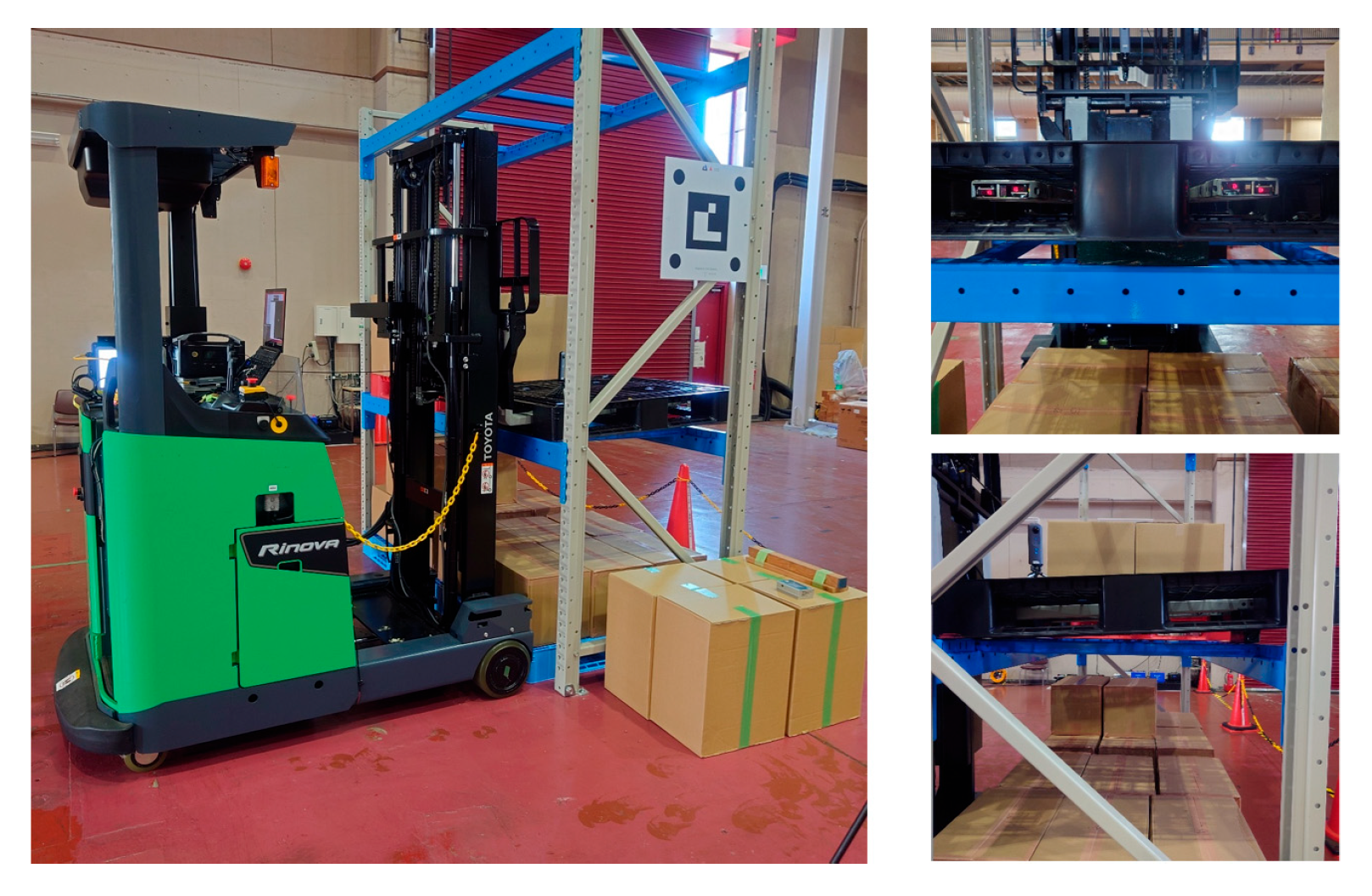

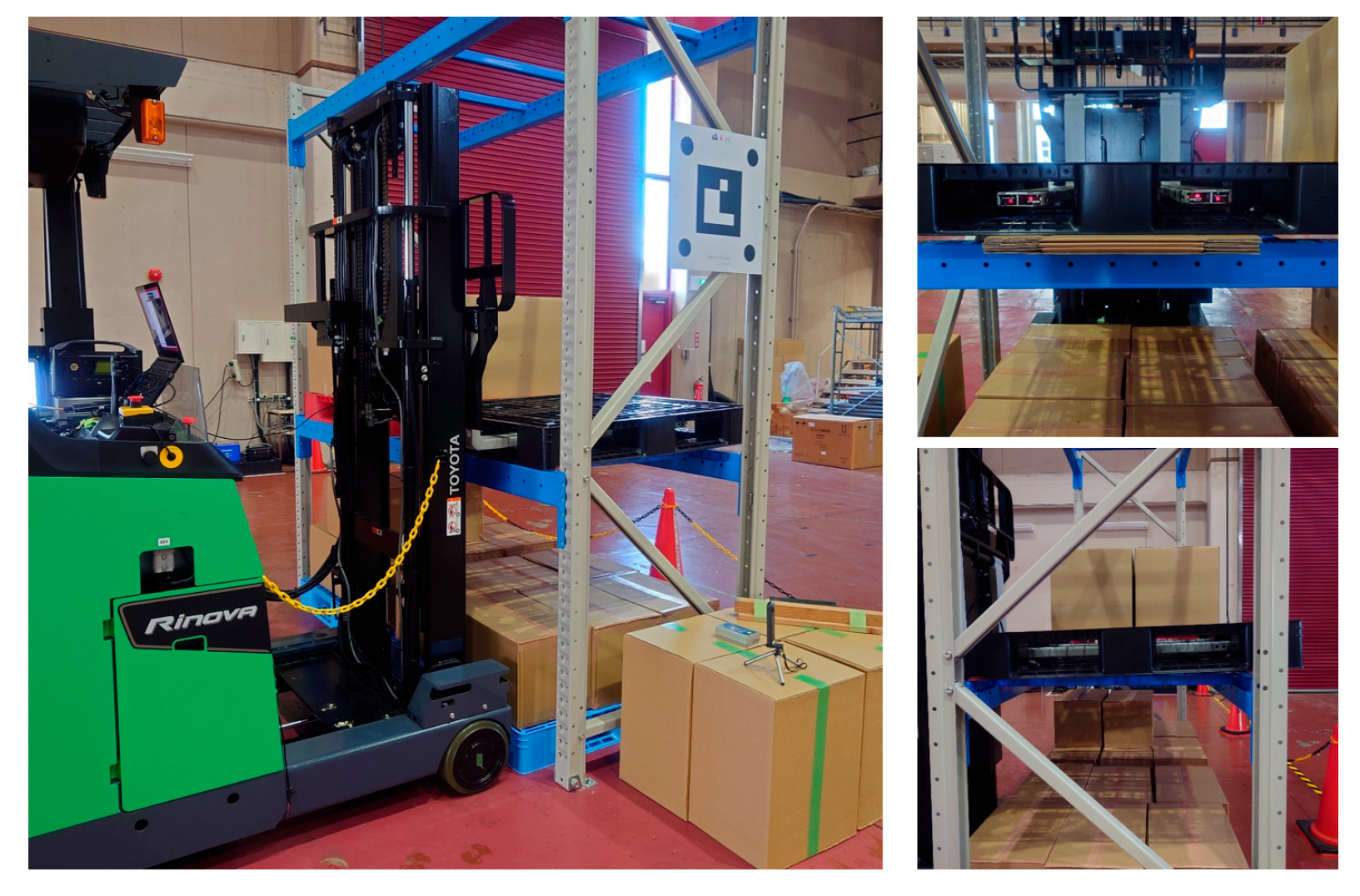

3.2. Overview of [Measurement 1-b]

3.3. Overview of [Measurement 2]

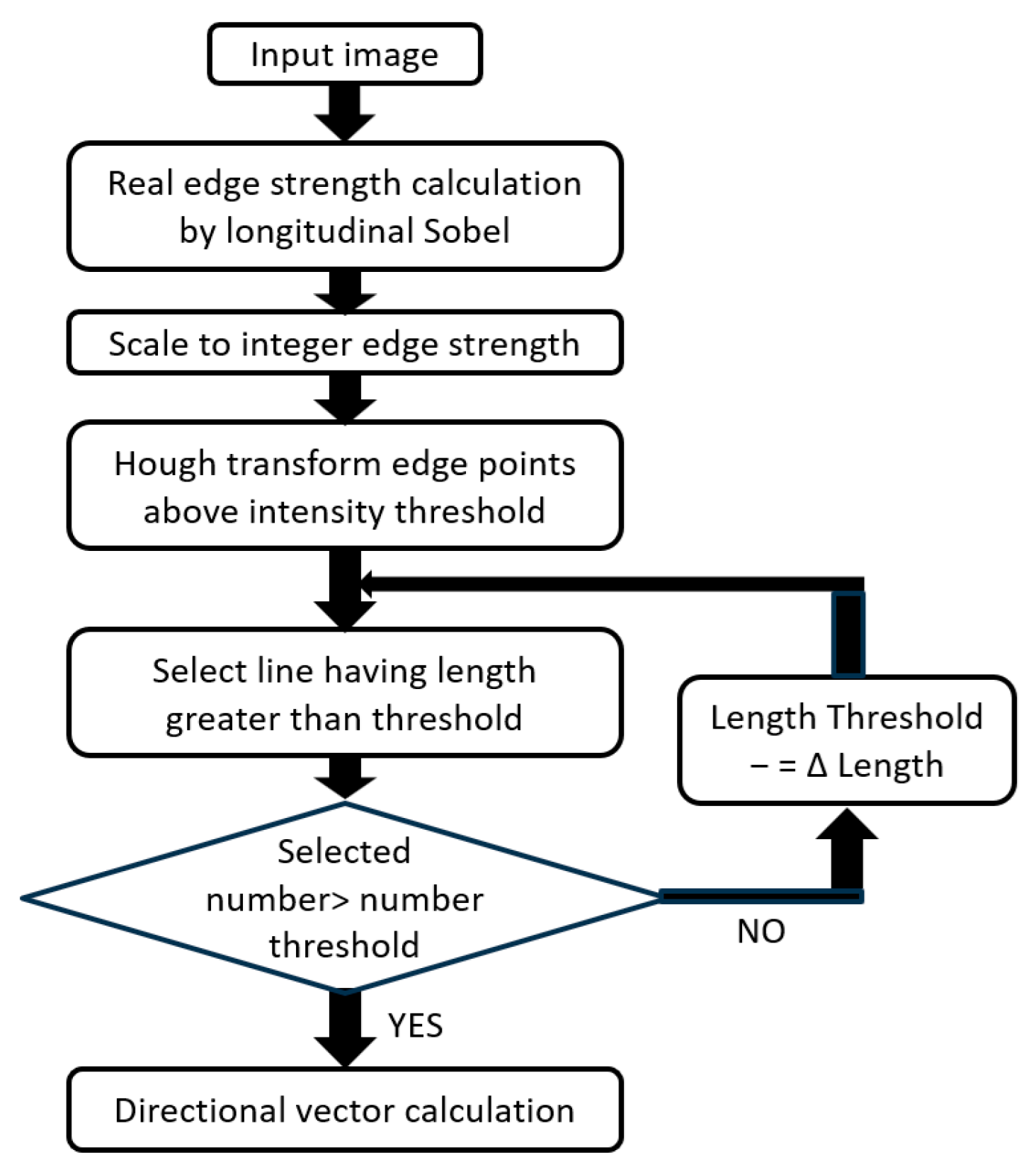

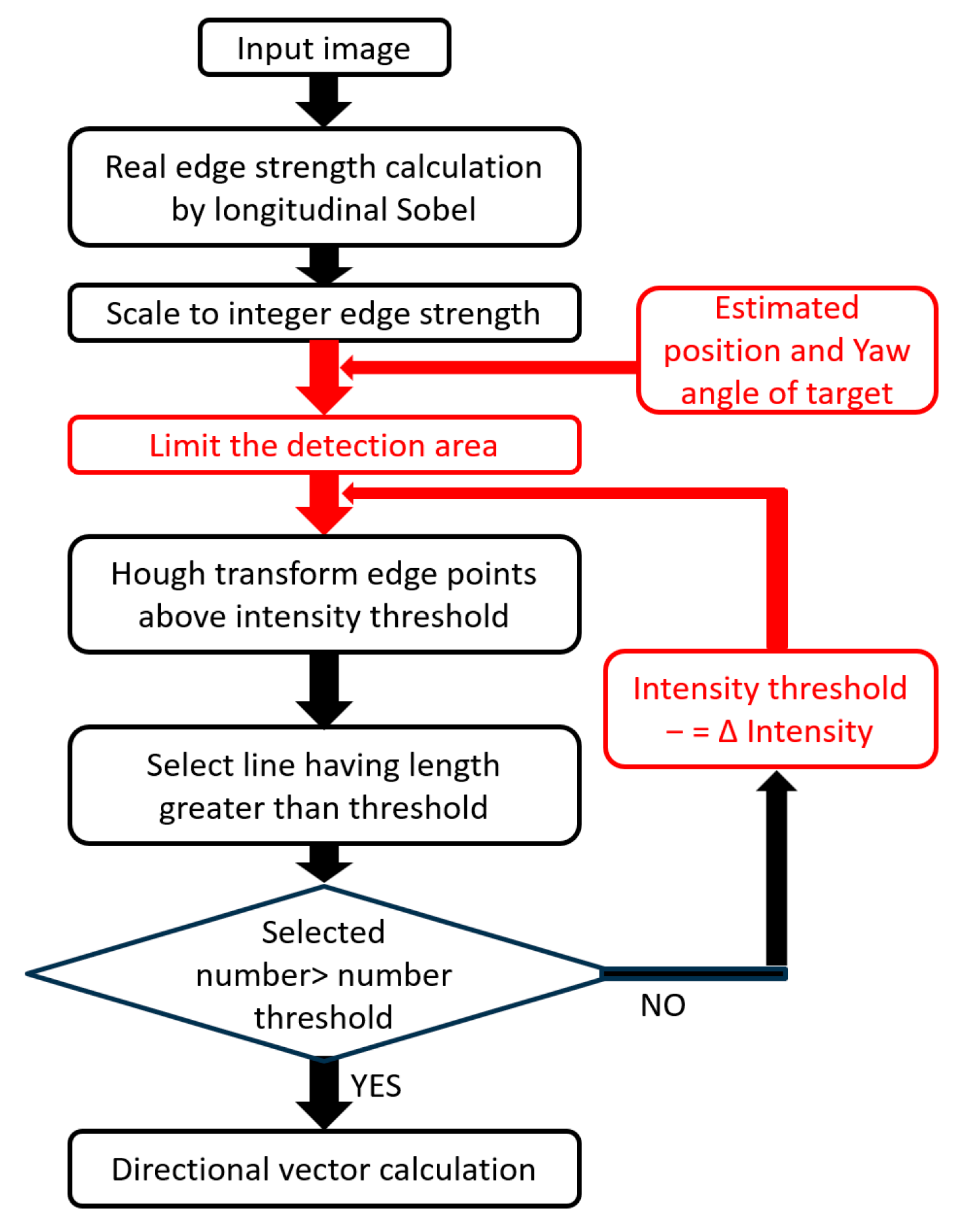

4. Robustness of Line Detection

5. Robustness of [Measurement 0]

5.1. Issues

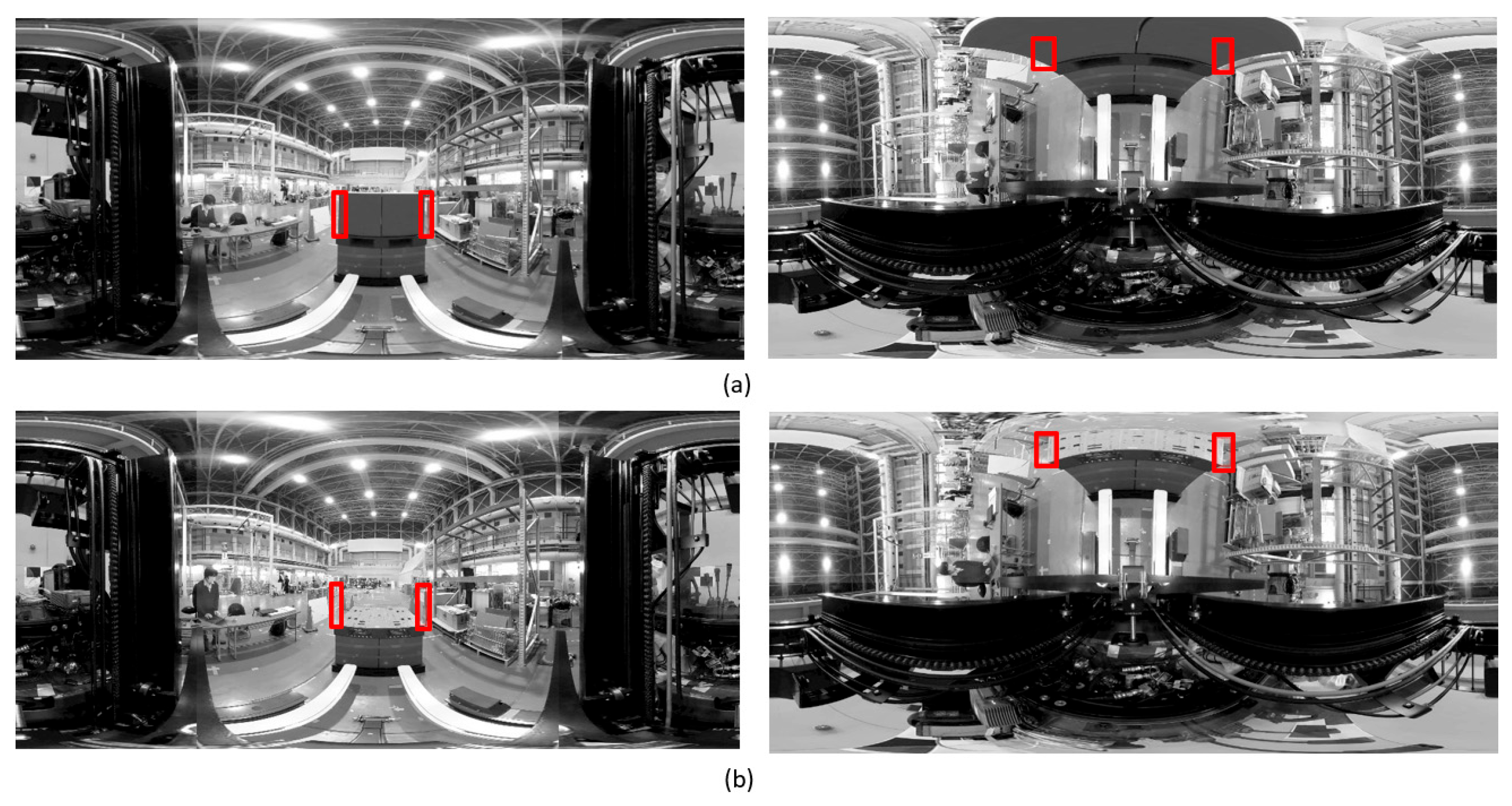

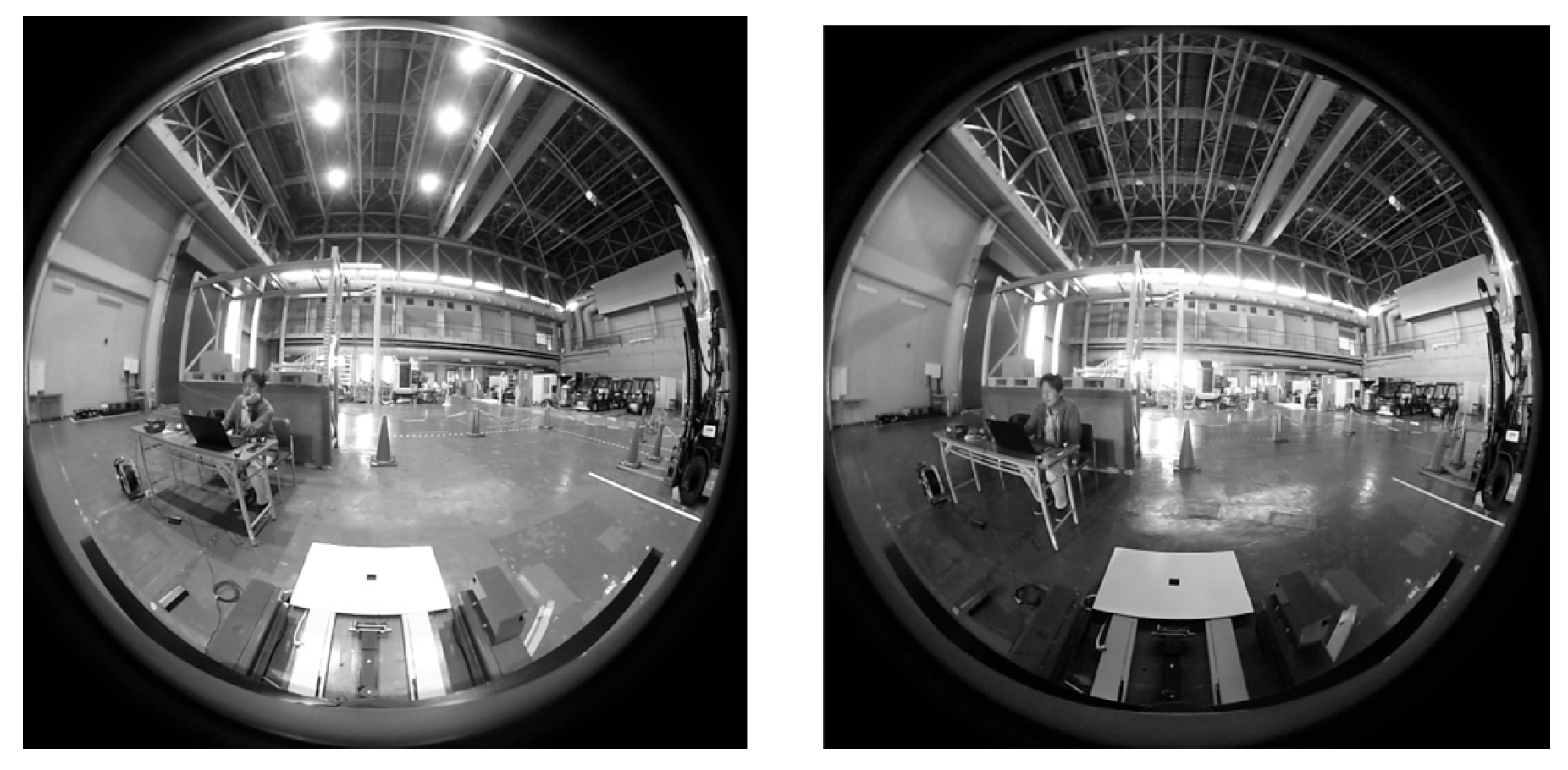

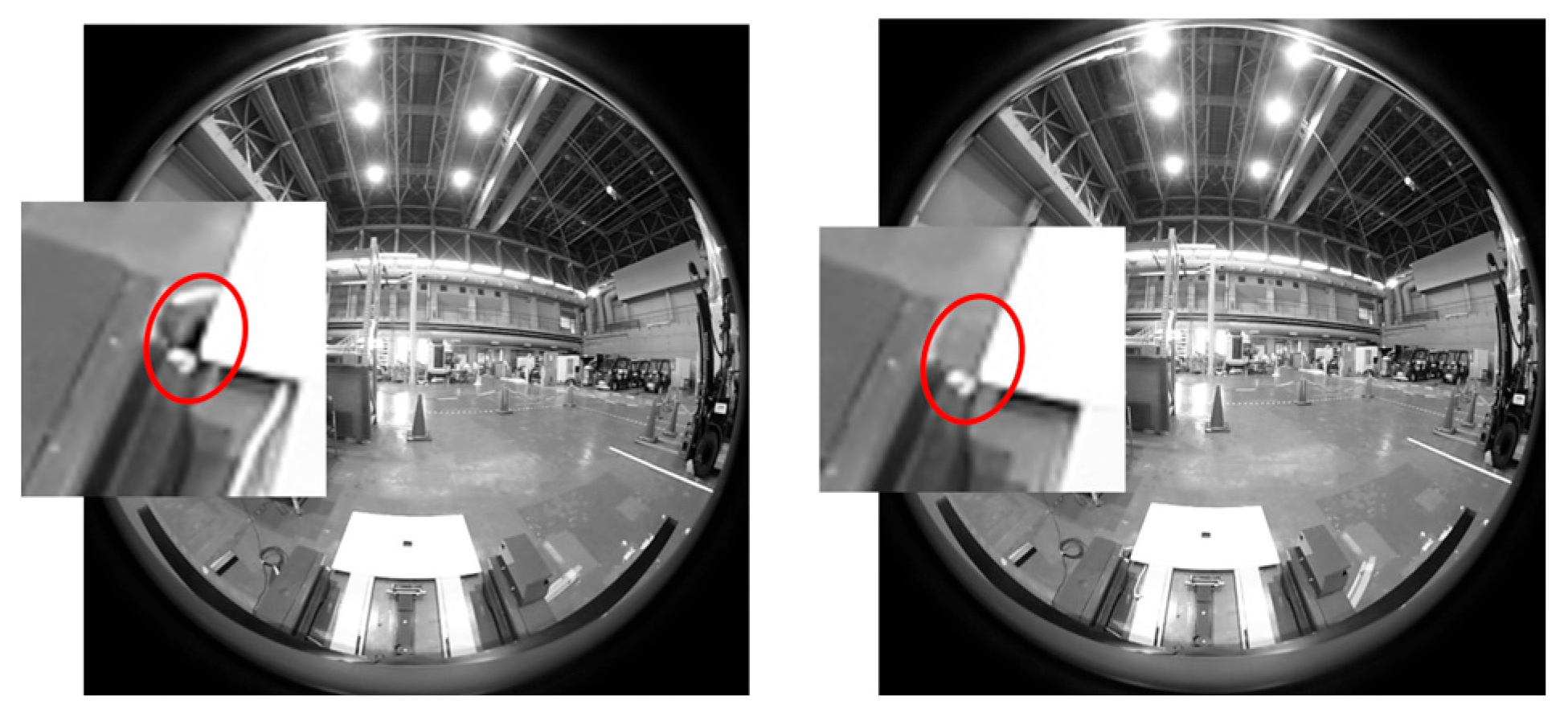

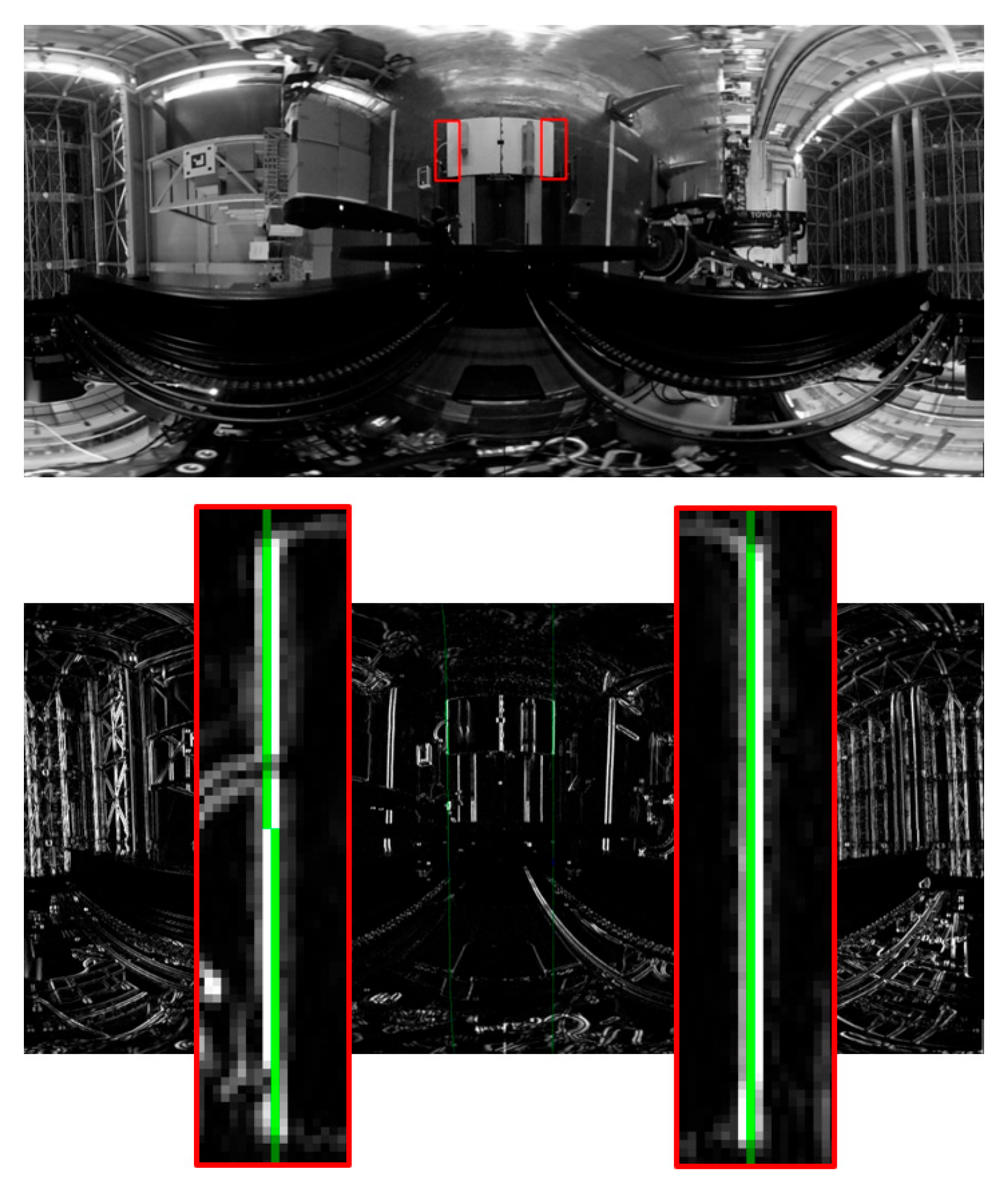

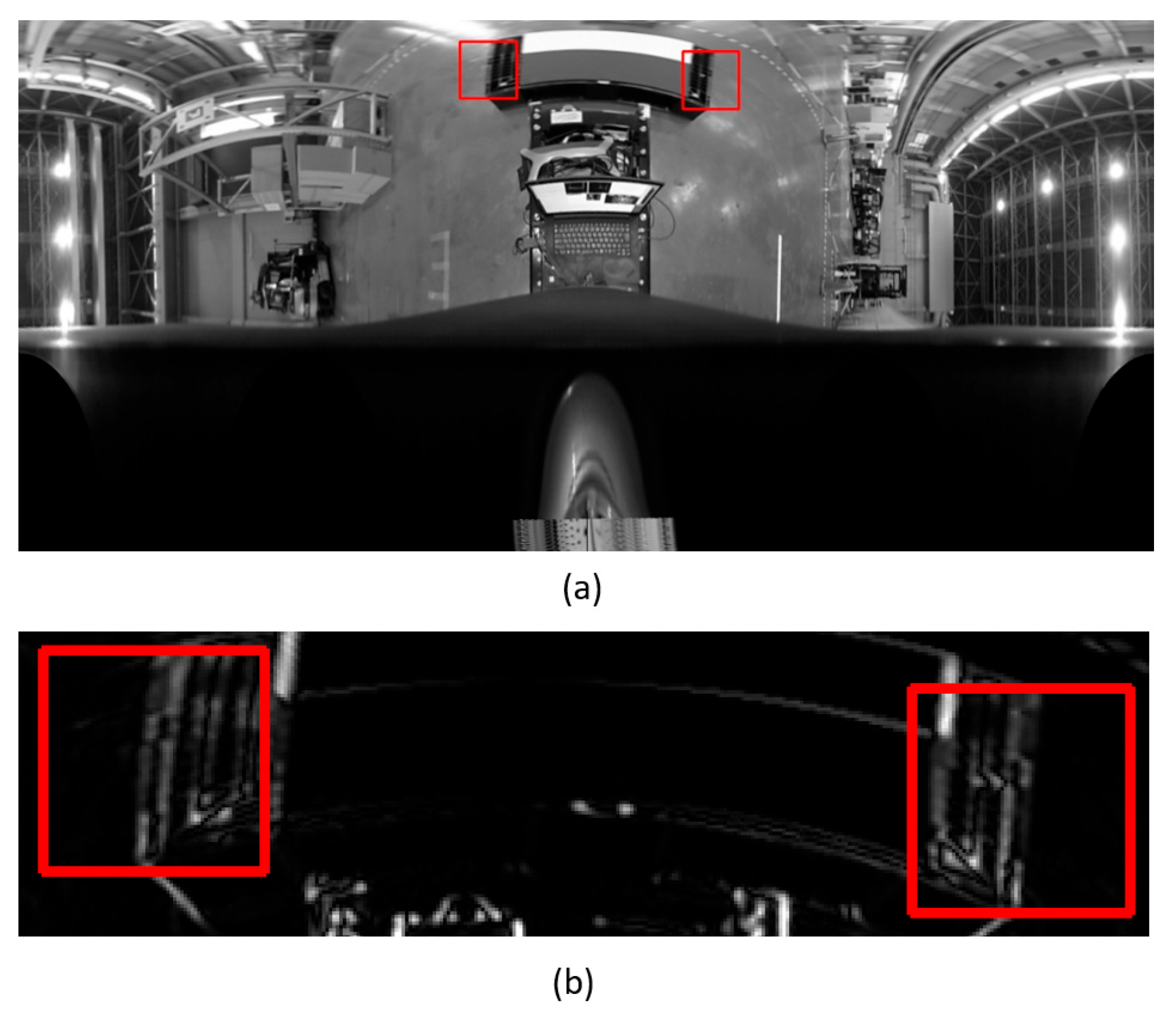

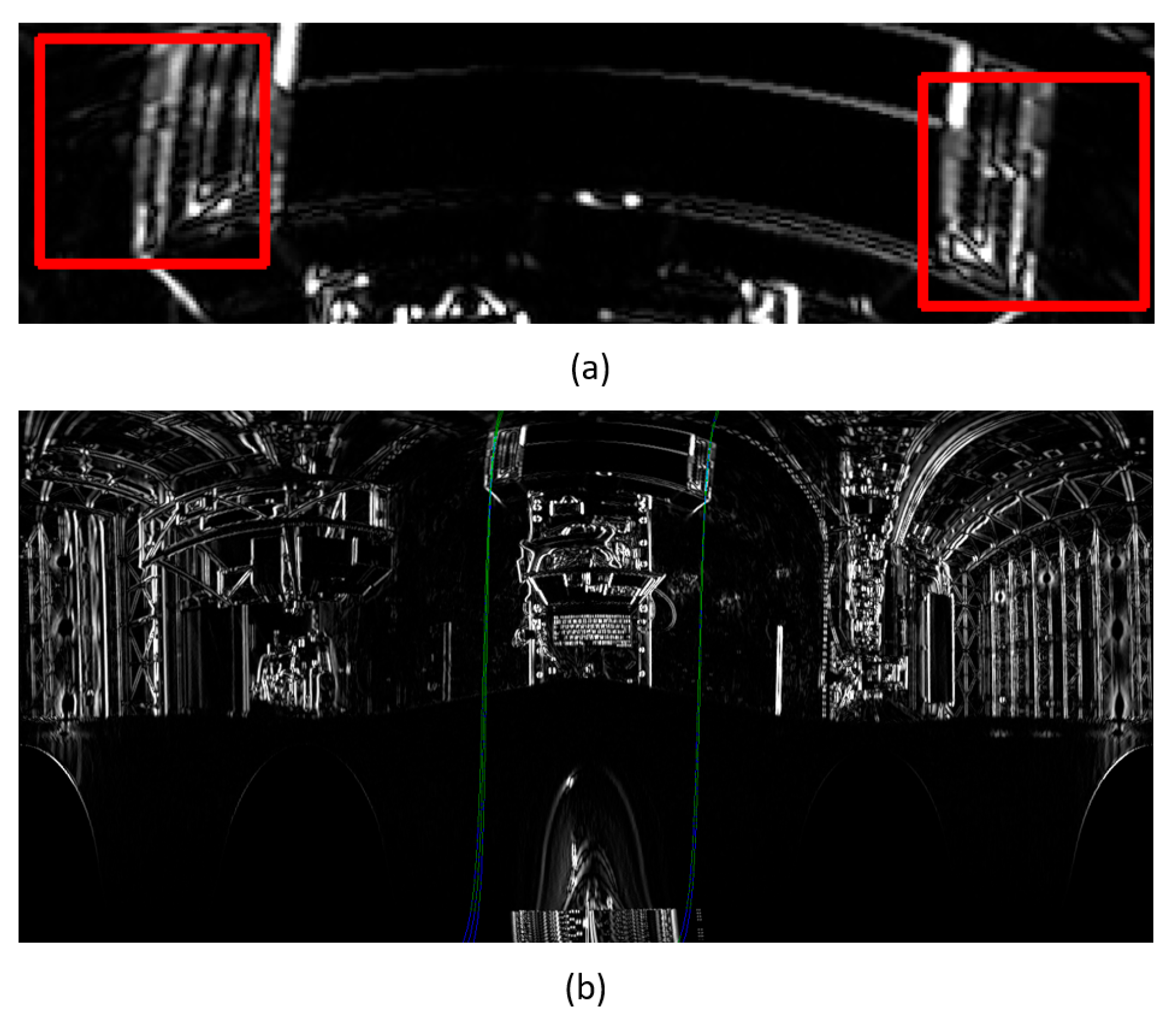

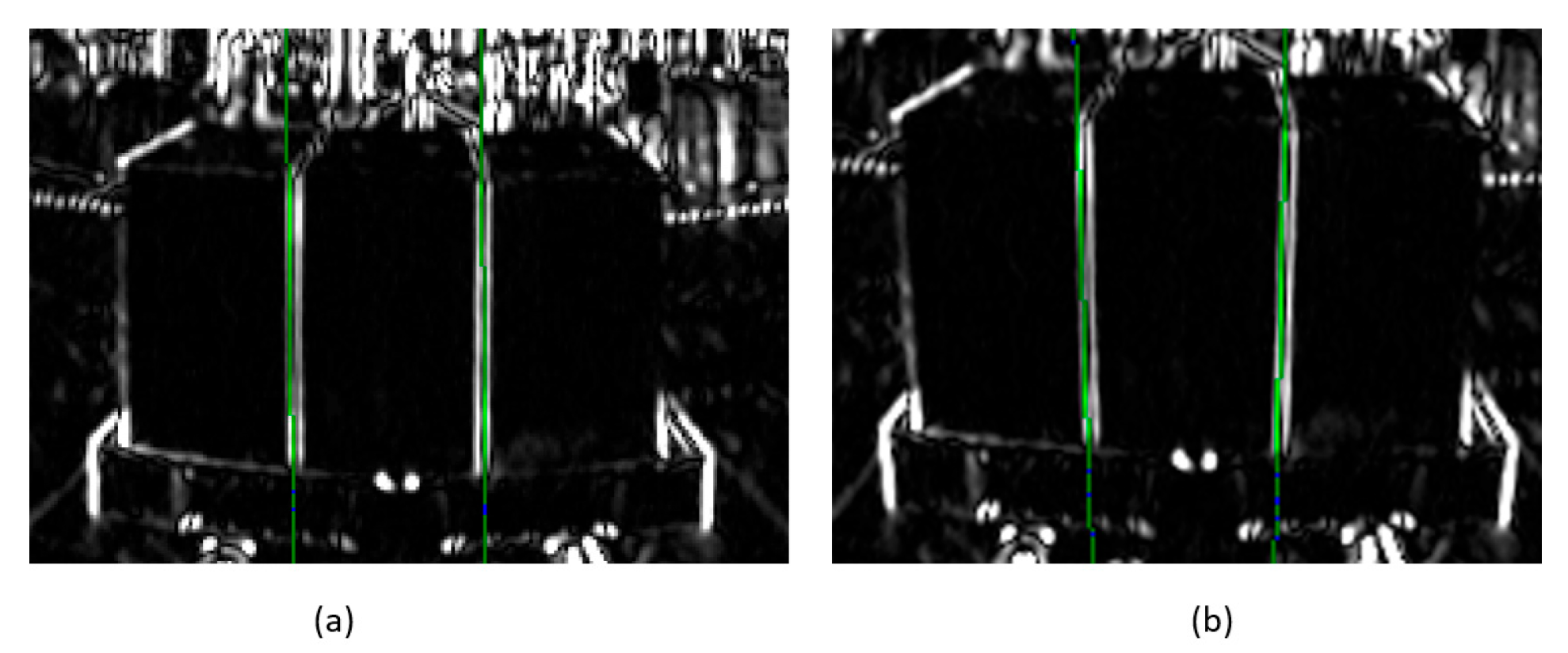

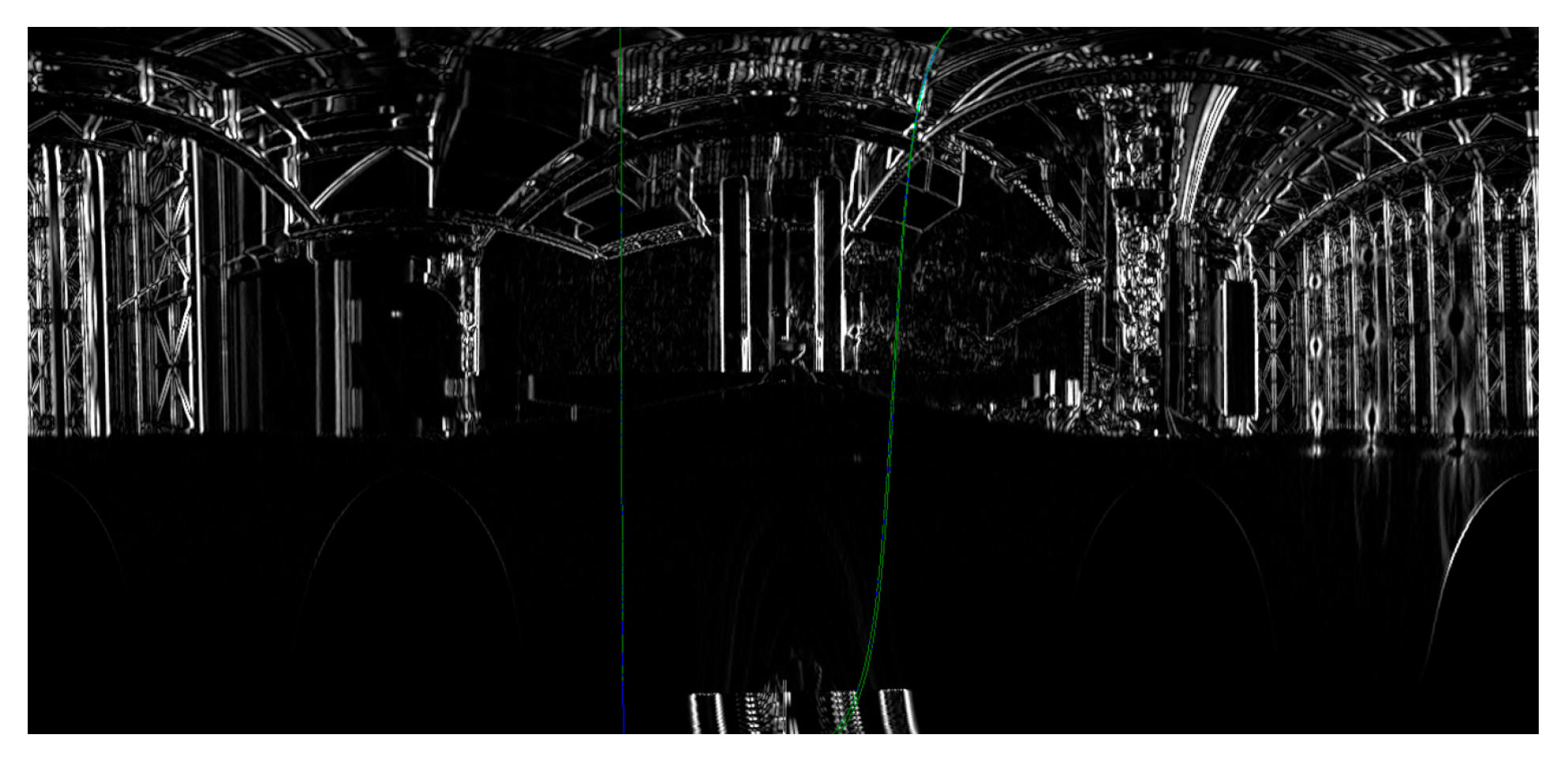

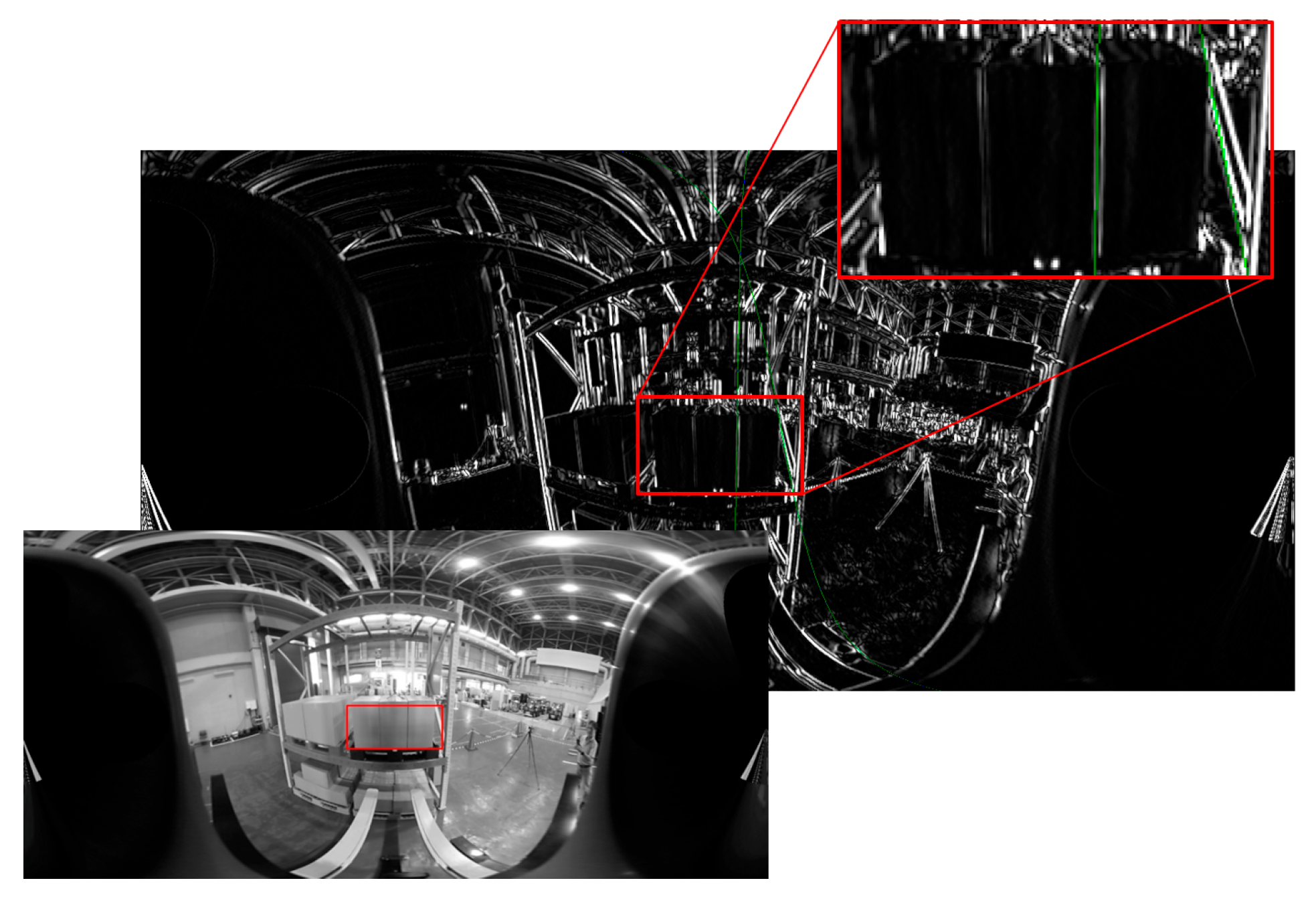

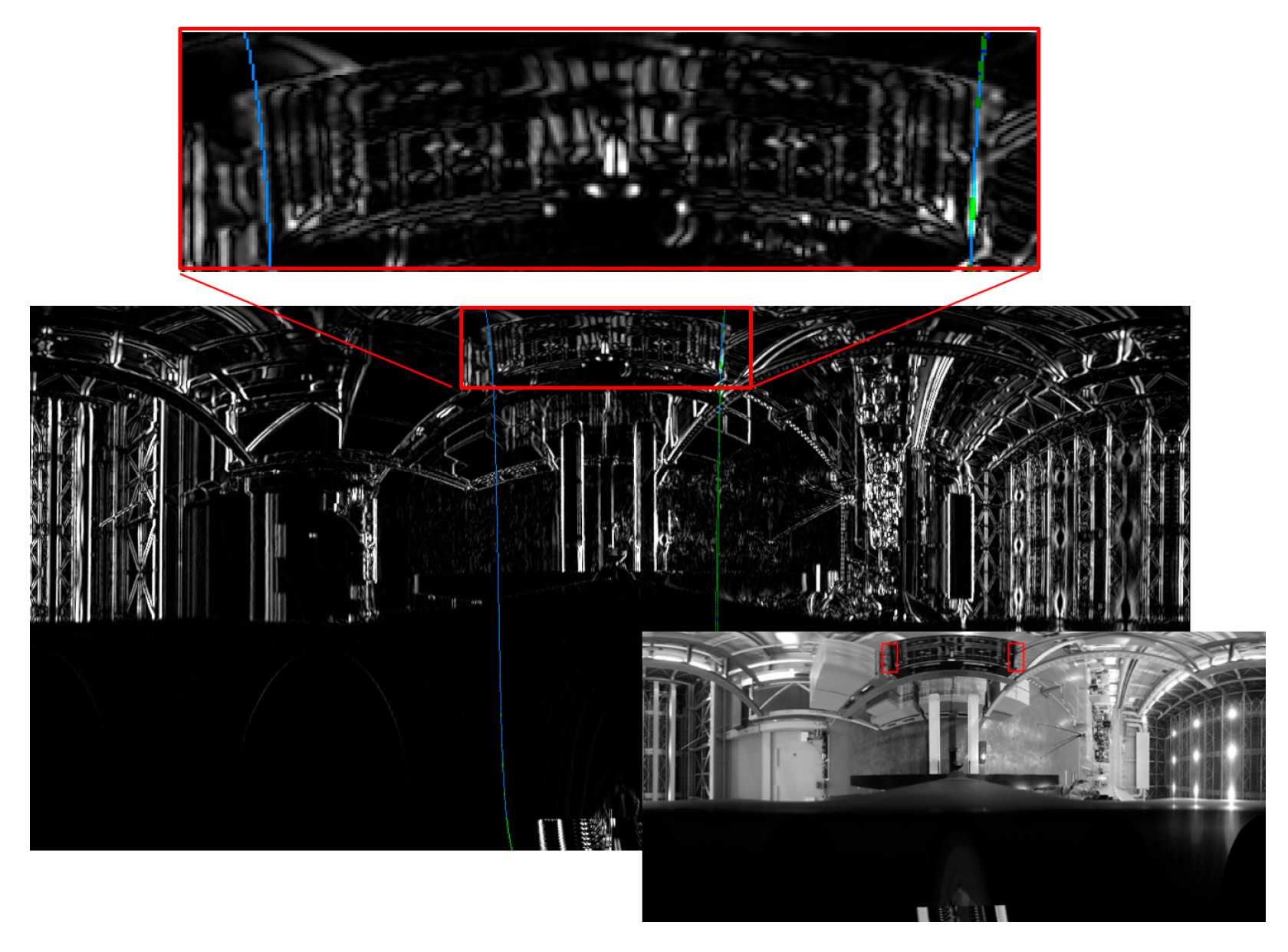

5.2. Improving the Central Axis of Panoramic Images

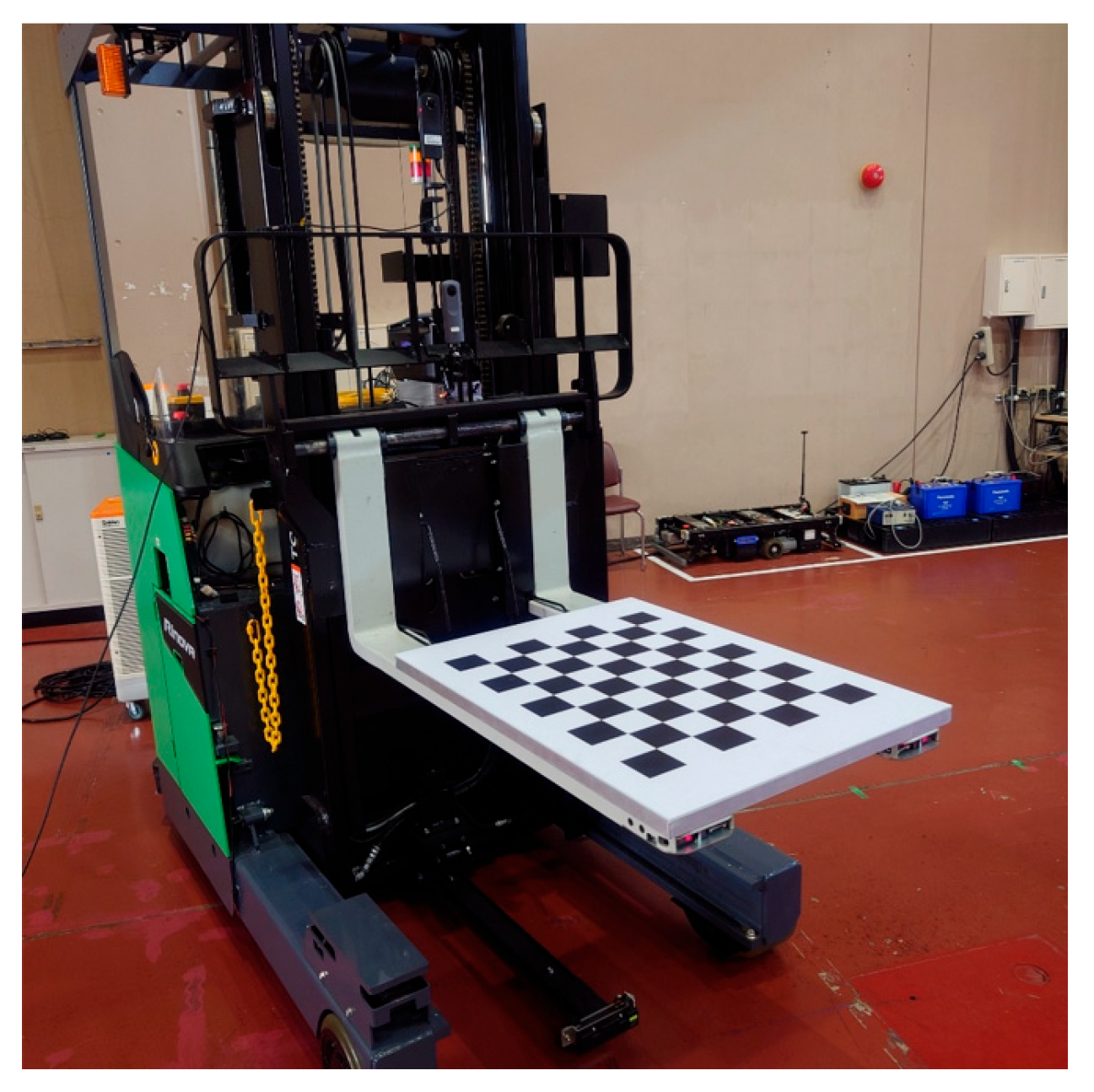

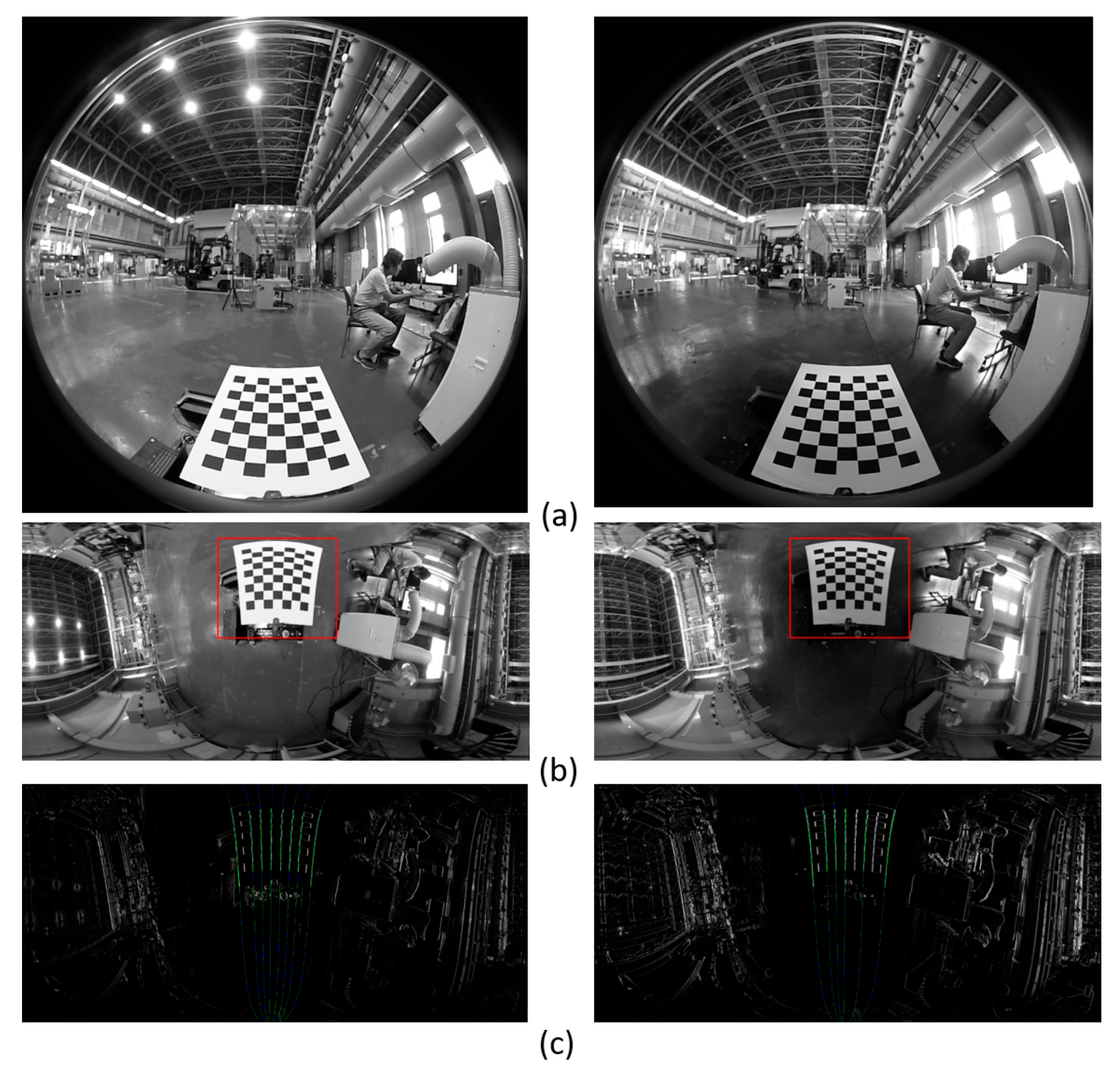

5.3. Use Rectangular Chess-like Panels

5.4. Results

6. Robustness of [Measurement 1-b]

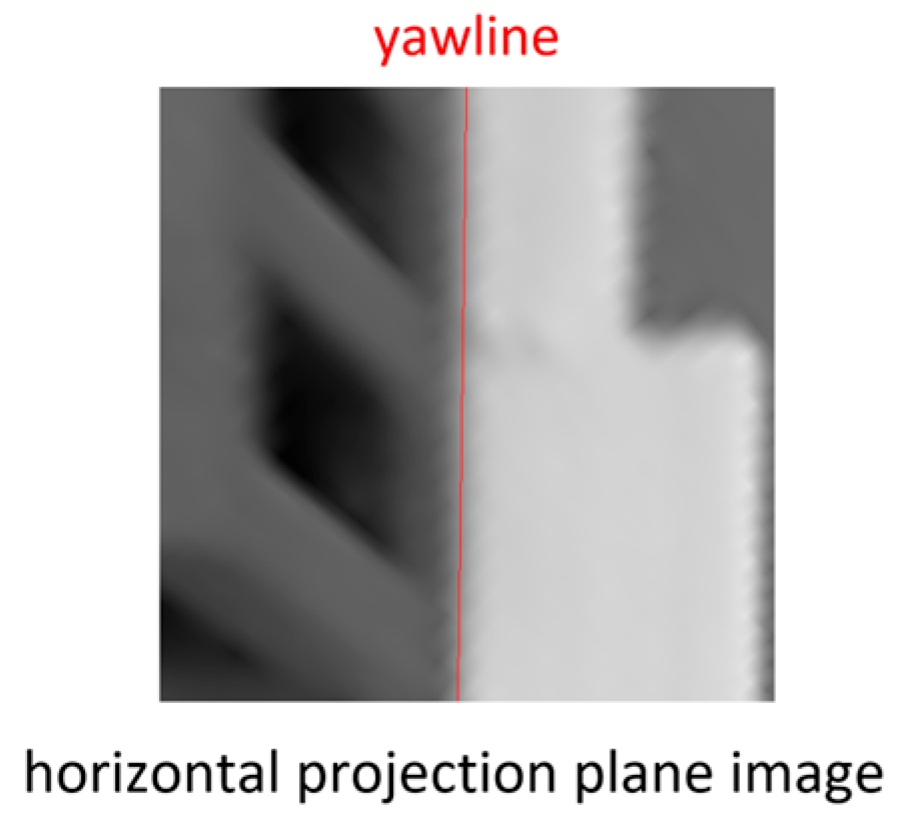

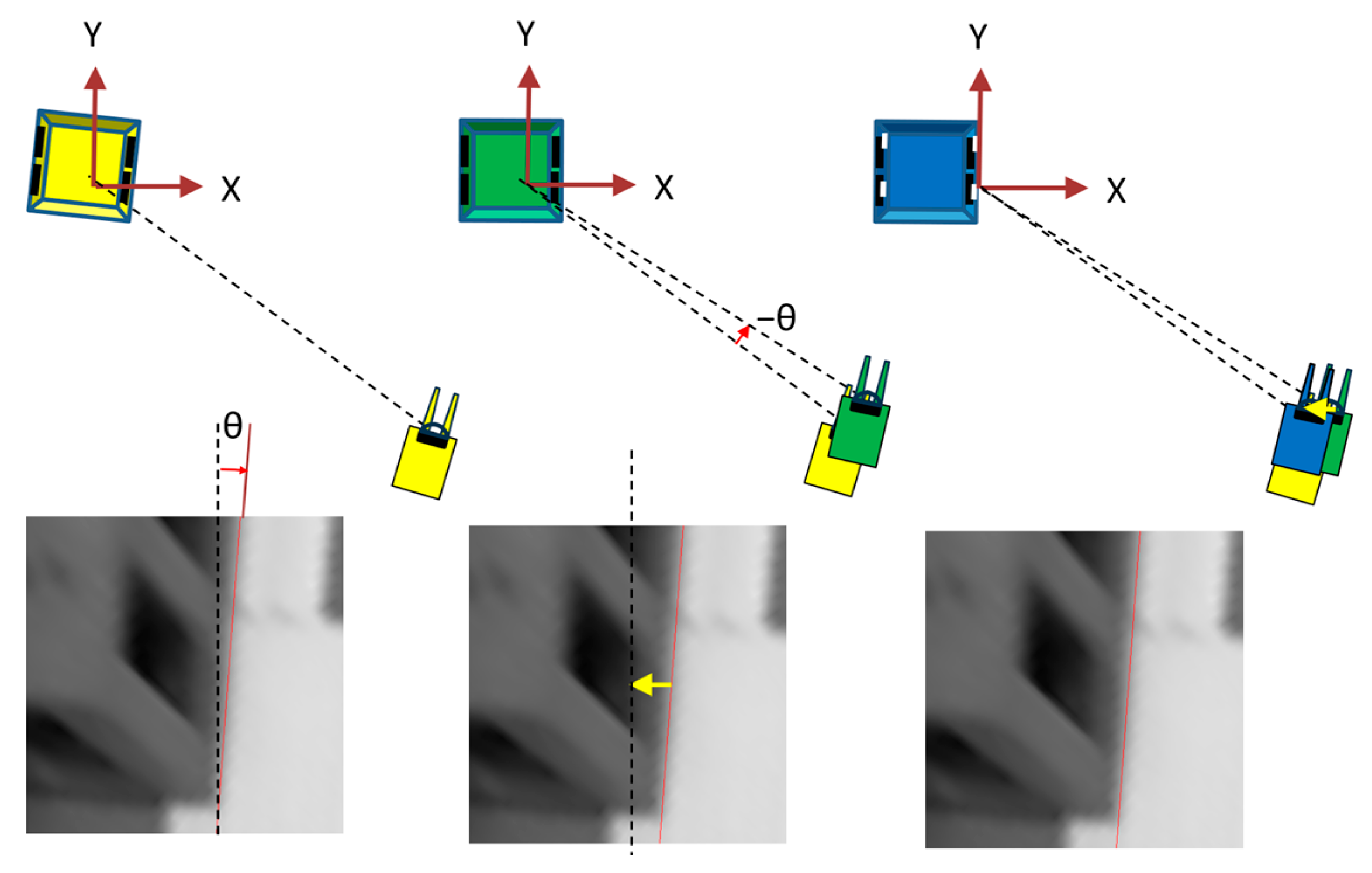

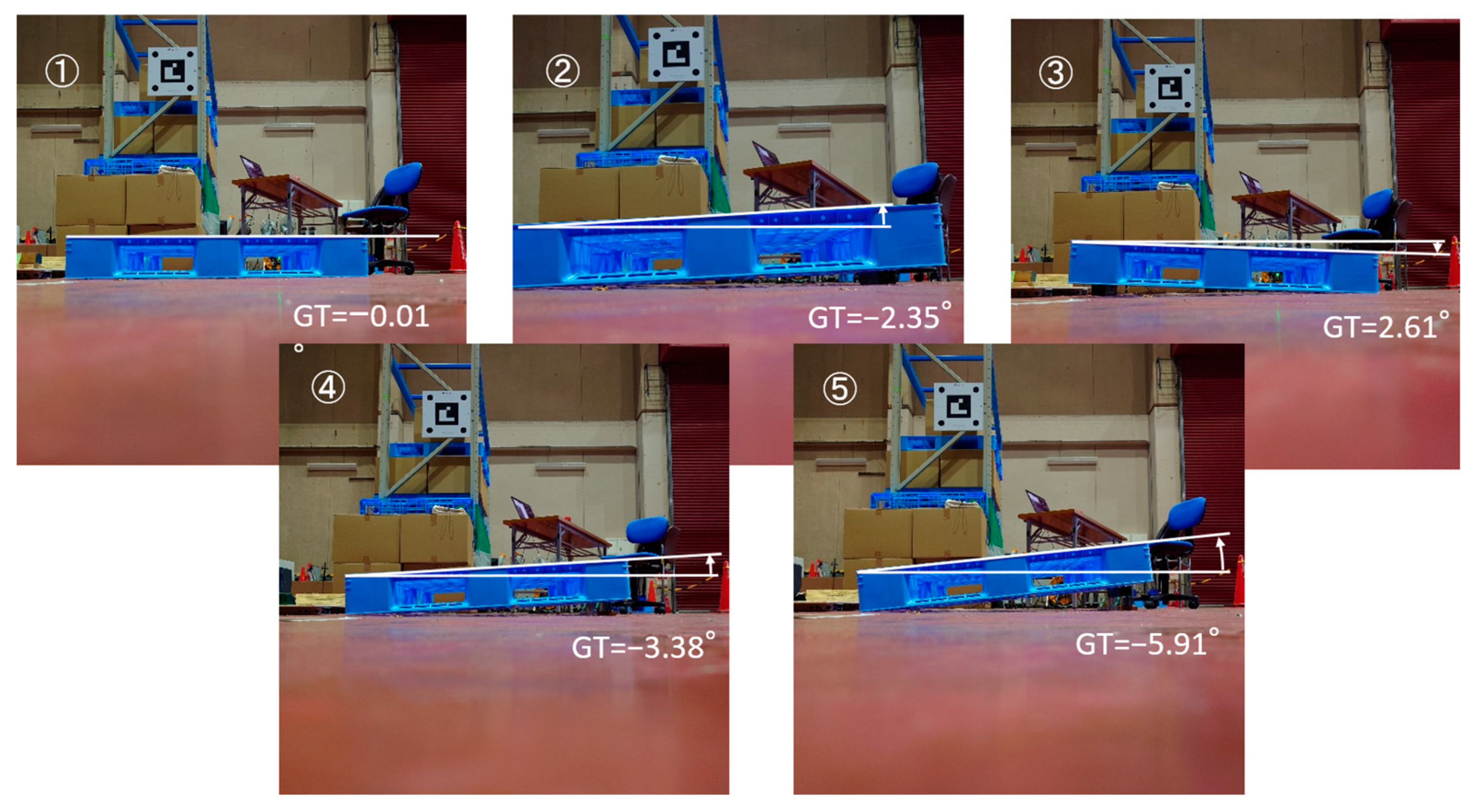

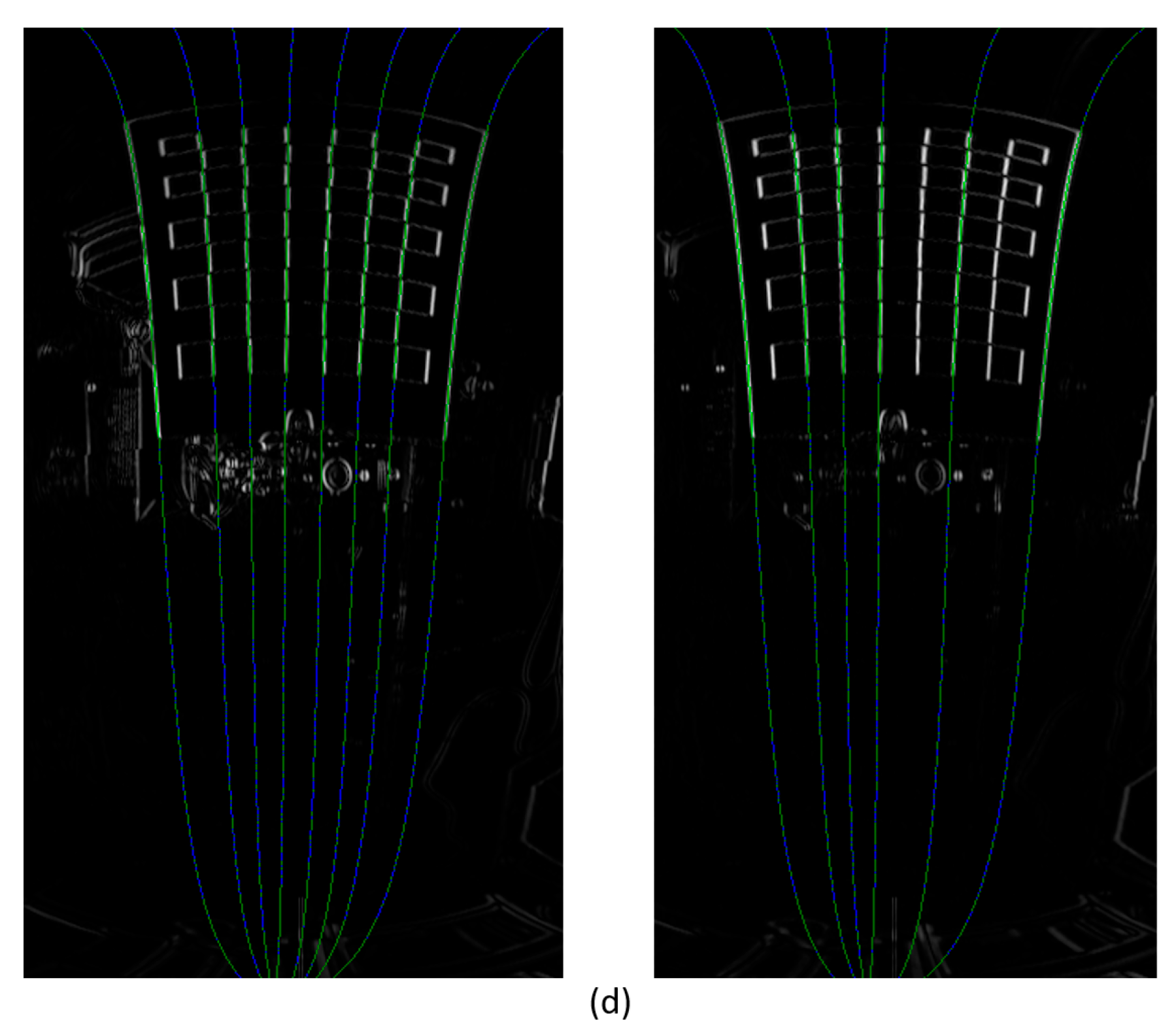

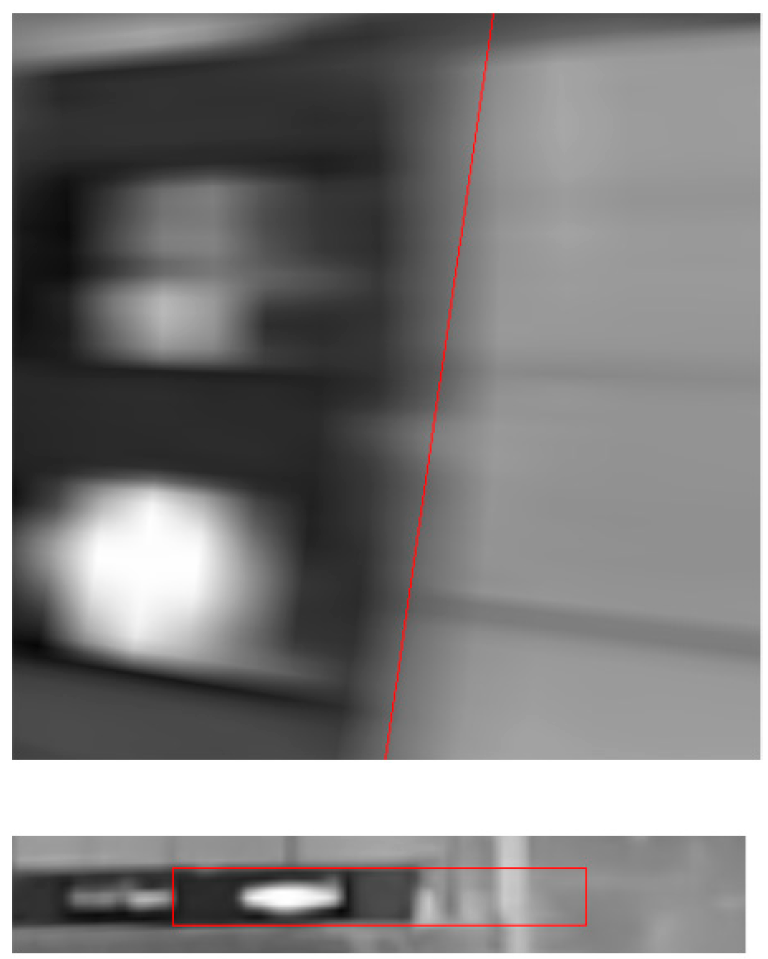

6.1. Yawline Detection Considering Edge Orientation

6.2. Compute Scale for Each Input Image

7. Robustness of [Measurement 2]

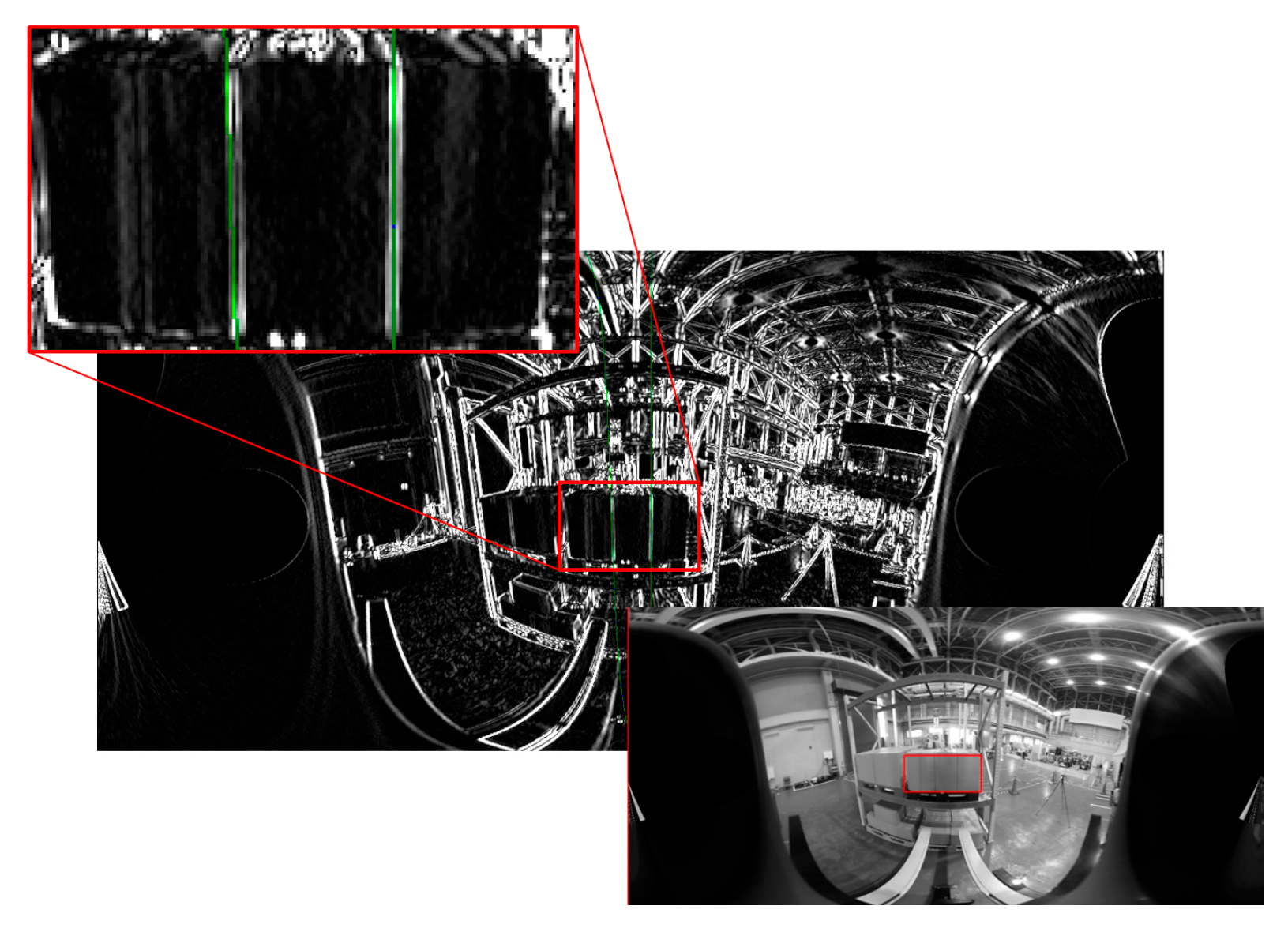

7.1. Compute Scale Adaptively

7.2. Improving the Central Axis of Panoramic Images

7.3. Improvement of Measurement Timing

8. Position and Attitude Control Experiment of Forklift and Fork Based on Image Measurement

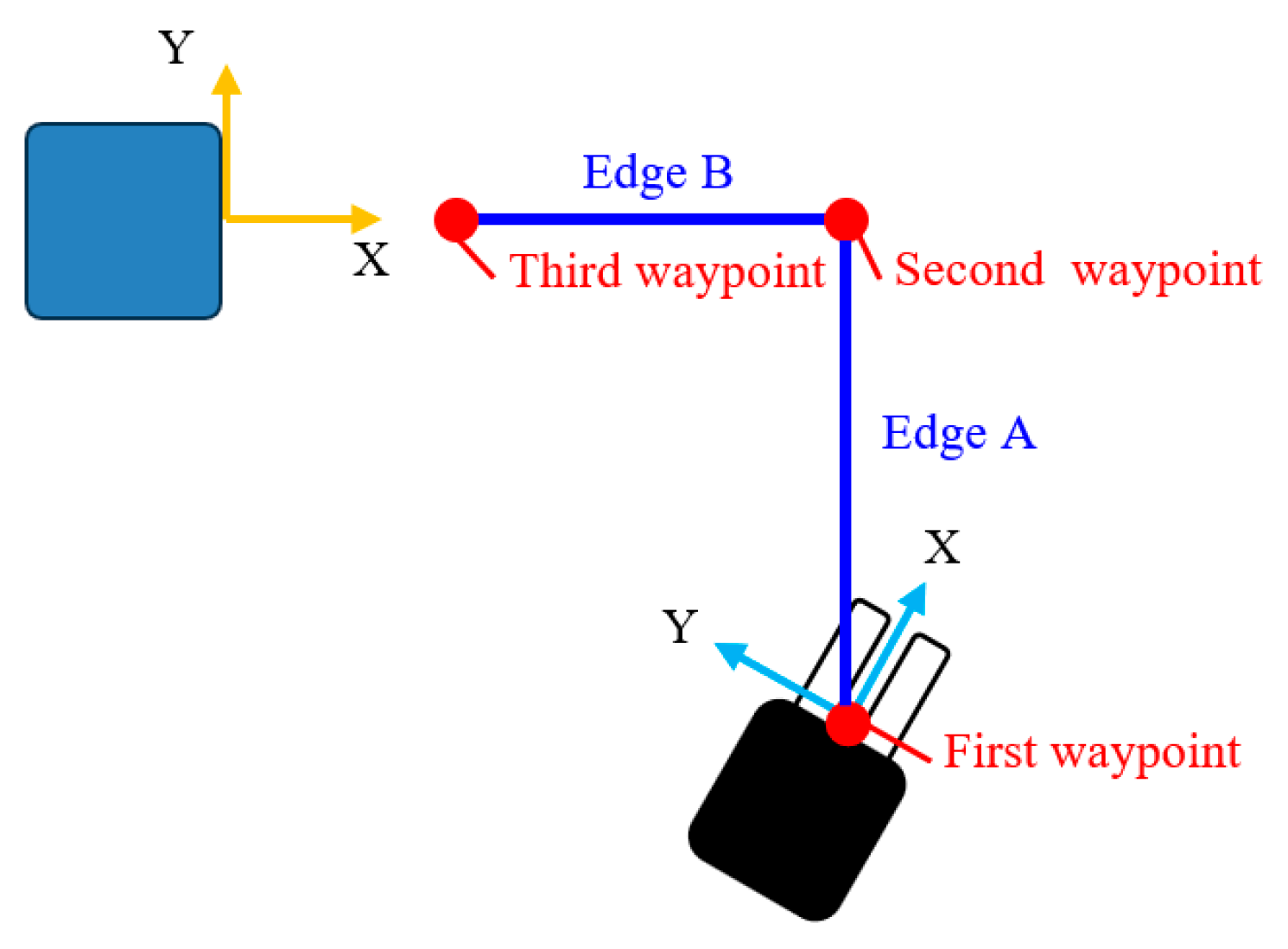

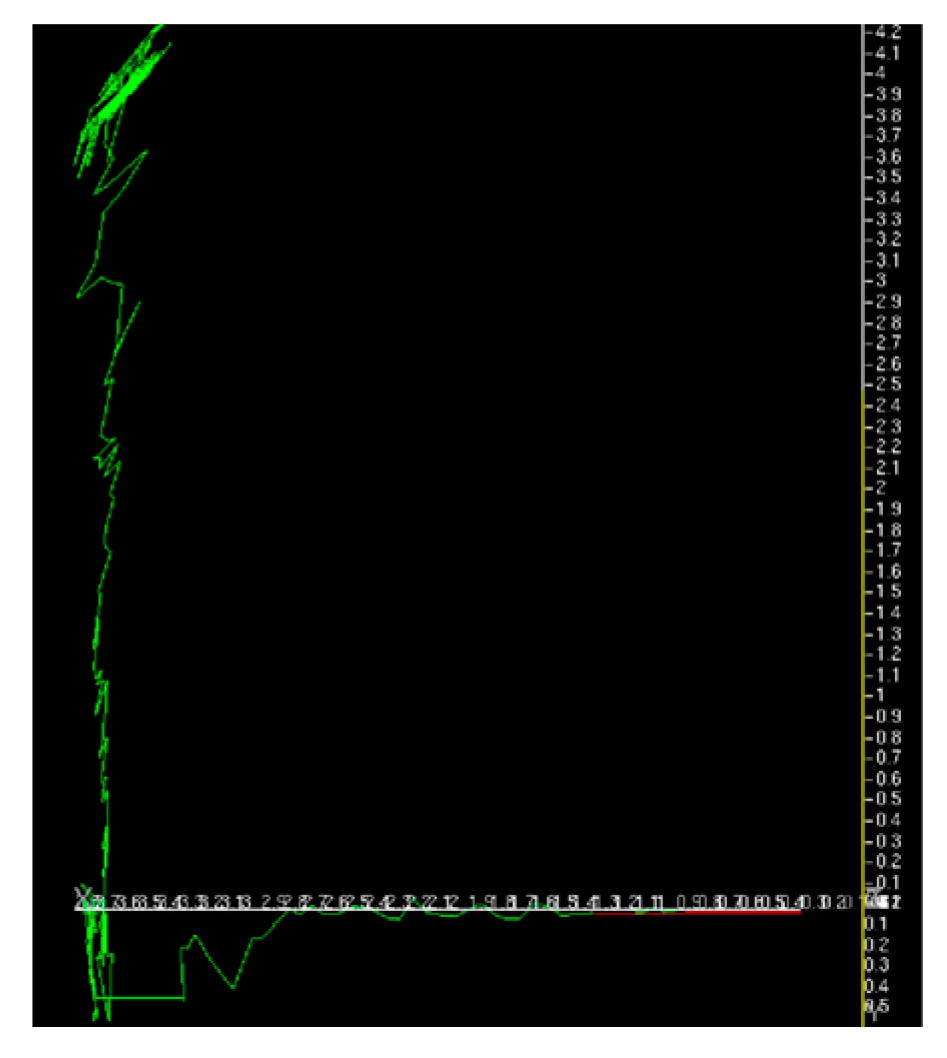

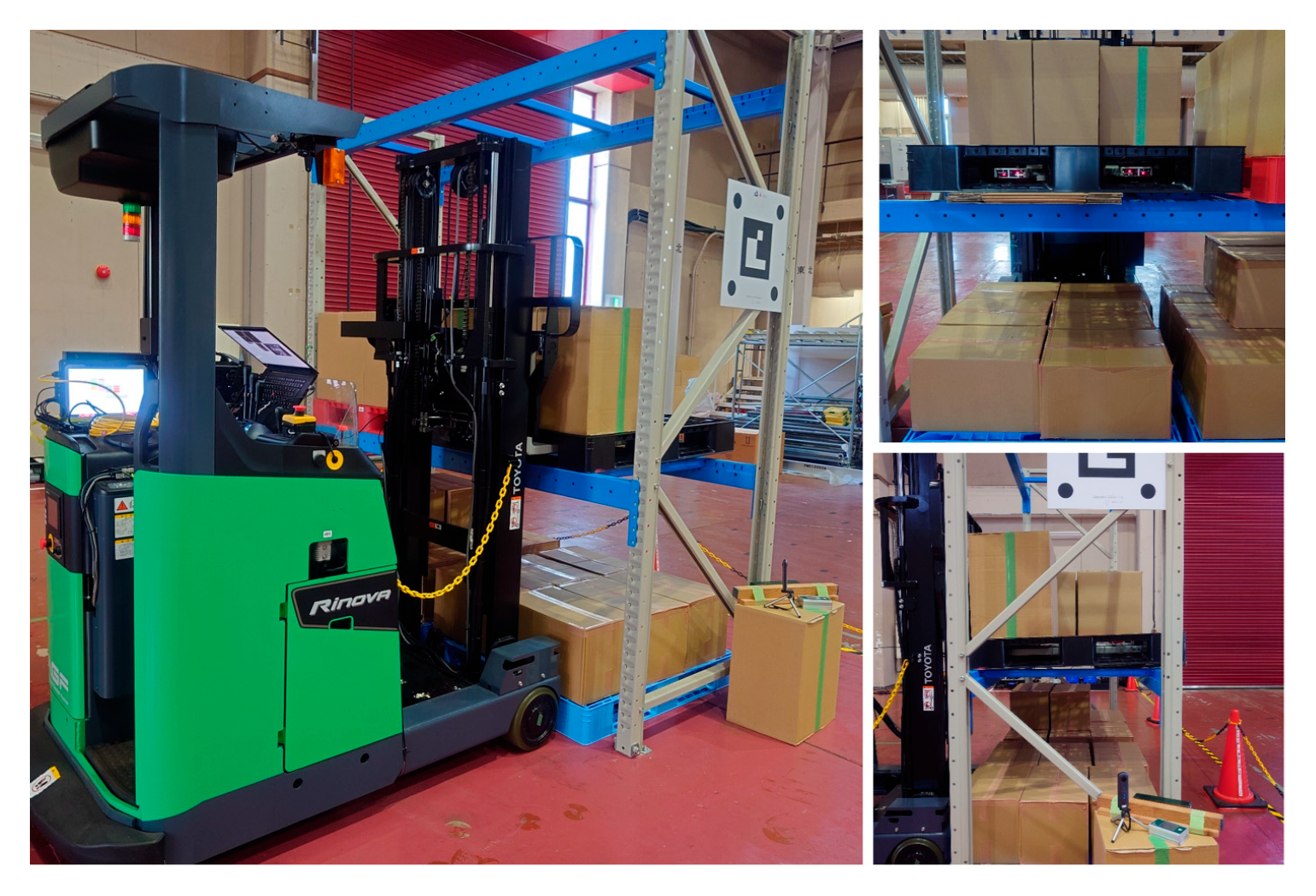

8.1. Forklift Movement Control Based on Image Measurement

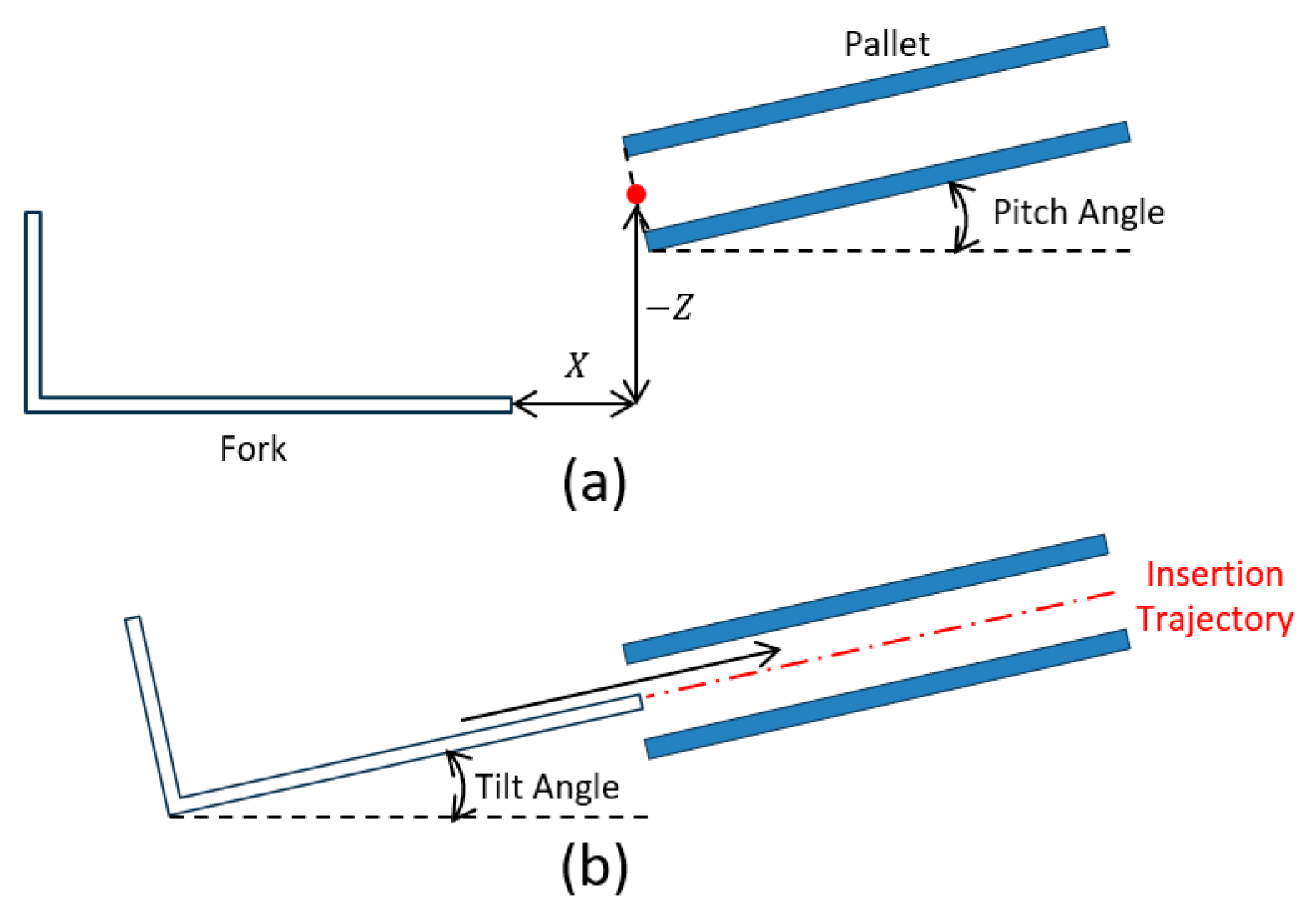

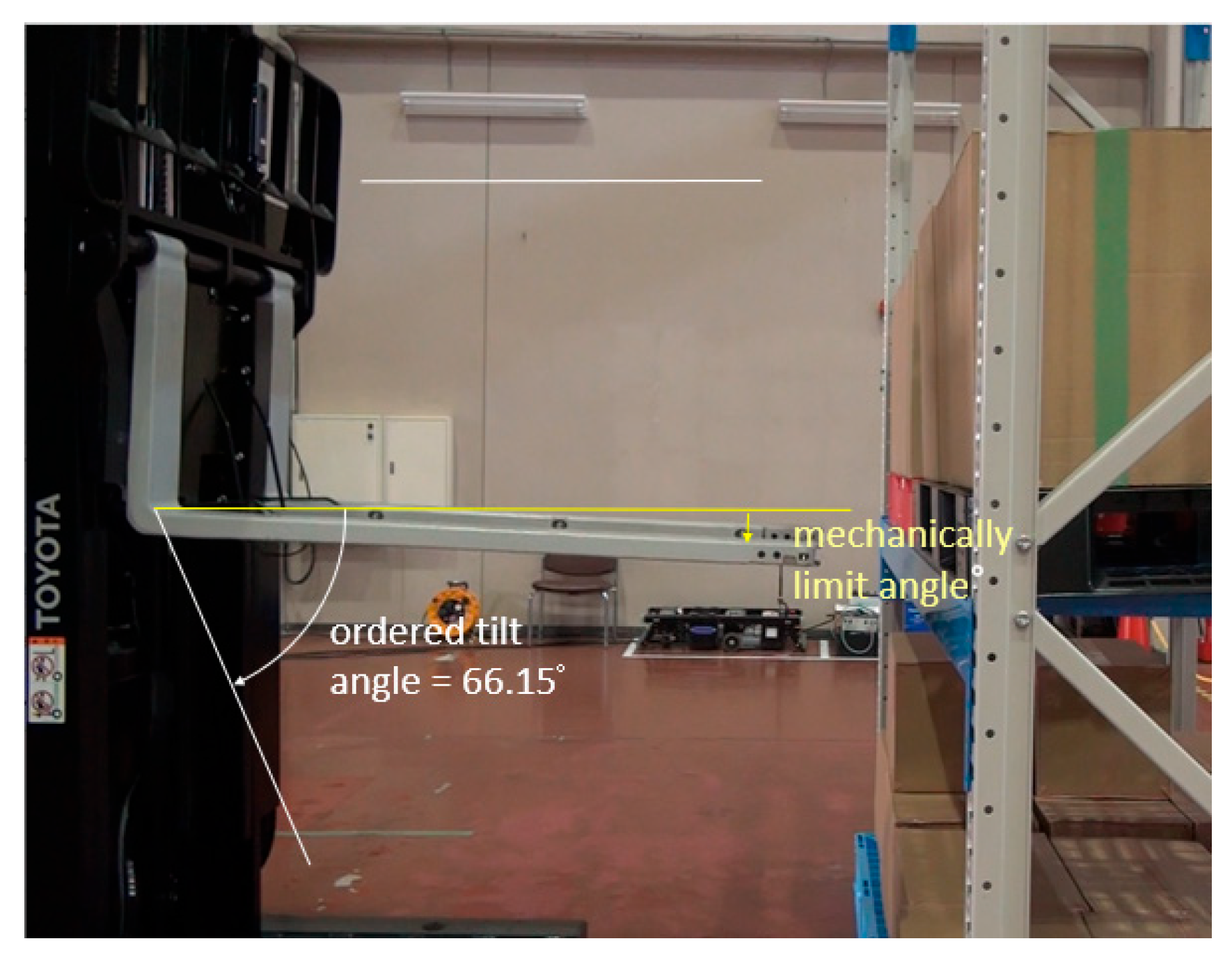

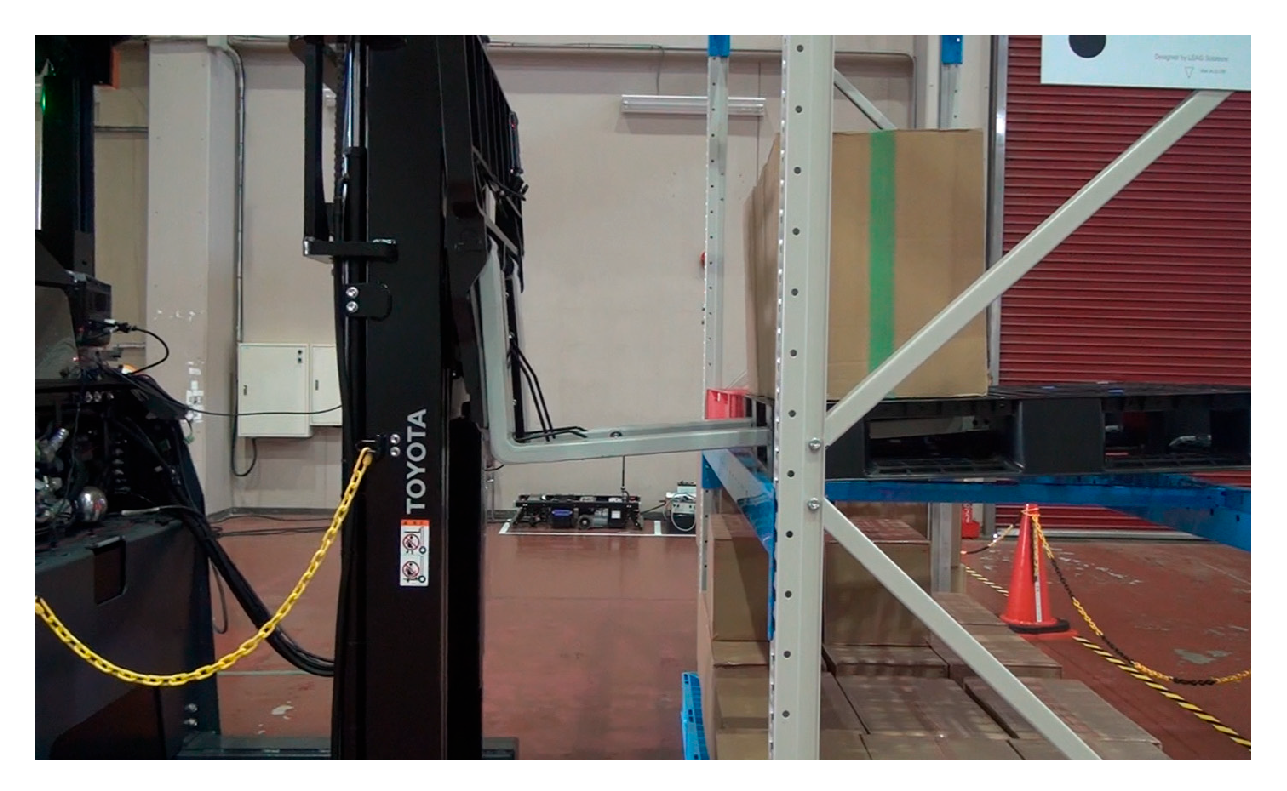

8.2. Fork Insertion Control

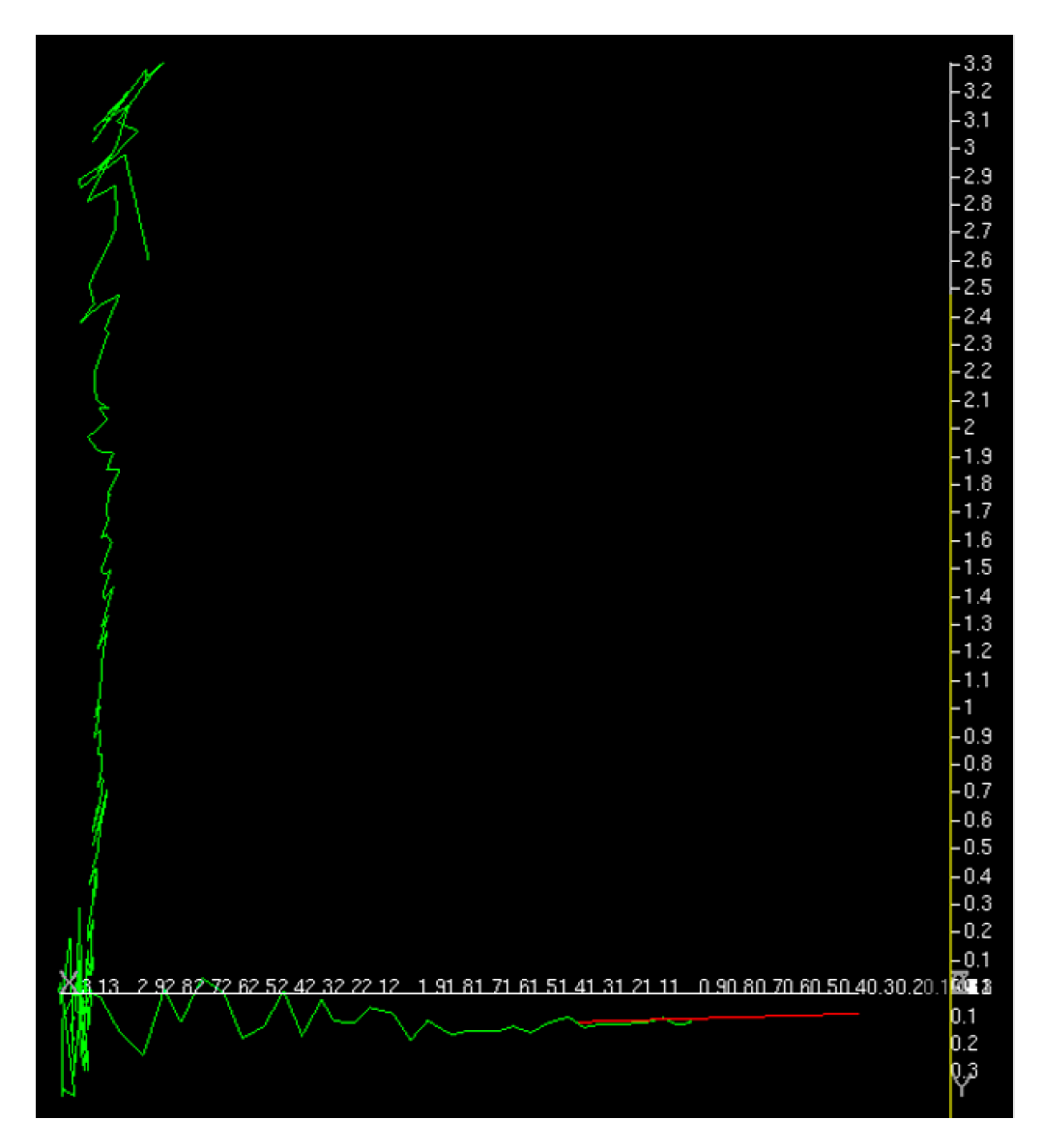

8.3. Results of Series of Motion Experiments

8.3.1. First Experiment

8.3.2. Second Experiment

8.3.3. Third Experiment

8.3.4. Fourth Experiment

8.3.5. Fifth Experiment

8.3.6. Sixth Experiment

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Improvement | Efficacy | |

| Measurement 0 | Line detection method | Precision up |

| Create a panoramic image with a tilted center axis | Precision up | |

| Use rectangular chess-like panels | Reduces the effects of background and lighting changes | |

| Measurement 1-b | Line detection method | False positive suppression |

| Considering edge orientation | False positive suppression | |

| Compute scale for each input image | Robustness to illumination conditions with viewpoint variations | |

| Measurement 2 | Line detection method | False positive suppression |

| Compute scale for each input image | Robustness to illumination variation | |

| Create a panoramic image with a tilted center axis | Precision up |

References

- Fazlollahtabar, H.; Saidi-Mehrabad, M. Autonomous guided vehicles. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Nahavandi, S.; Alizadehsani, R.; Nahavandi, D.; Mohamed, S.; Mohajer, N.; Rokonuzzaman, M.; Hossain, I. A comprehensive review on autonomous navigation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, H.; Chew, D.A.; Yang, S.-H.; Gibb, A.G.; Li, Q. Towards an autonomous real-time tracking system of near-miss accidents on construction sites. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jung, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. Accuracy improvement of magnetic guidance sensor using fuzzy inference system. In Proceedings of the 2012 Joint 6th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems (SCIS) the13th Intelligence Symposium on Advanced Intelligent Systems, Kobe, Japan, 20–24 November 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1639–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Beinschob, P.; Reinke, C. Graph SLAM based mapping for AGV localization in large-scale warehouses. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 3–5 September 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Lü, E.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, G.; Lu, H. Efficient stereo visual simultaneous localization and mapping for an autonomous unmanned forklift in an unstructured warehouse. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišković, D.; Milić, L.; Čilag, A.; Berisavljević, T.; Gottscheber, A.; Raković, M. Implementation of robots integration in scaled laboratory environment for factory automation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, Y.; Takase, R.; Komuro, T.; Kato, N.; Kita, N. Detection and localization of pallets on shelves using a wide-angle camera. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2–6 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 785–792. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, Y.; Takase, R.; Komuro, T.; Kato, N.; Kita, N. Localization of pallets on shelves in a warehouse using a wide-angle camera. In Proceedings of the IEEE 17th International Conference on Advanced Motion Control (AMC), Padova, Italy, 18–20 February 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, Y.; Fujieda, Y.; Matsuda, I.; Kita, N. Localization of Pallets on Shelves Using Horizontal Plane Projection of a 360-degree Image. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.17118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, N.; Kato, T. Image Measurement method for automatic insertion of forks into inclined pallet. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV), Singapore, 11–13 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, N.; Kita, Y.; Kato, T. Image measurement method for navigating an AGF to a pallet. In Proceedings of the 4th IFSA Winter Conference on Automation, Robotics & Communications for Industry 4.0/5.0 (ARCI’ 2024), Innsbruck, Austria, 7–9 February 2024; pp. 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, N.; Kato, T. Enhancing robustness of image measurement method for navigating an AGF to a pallet for real site use. In Proceedings of the 5th IFSA Winter Conference on Automation, Robotics & Communications for Industry 4.0/5.0 (ARCI’ 2025), Granada, Spain, 19–21 February 2025; pp. 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cucchiara, R.; Piccardi, M.; Prati, A. Focus based feature extraction for pallets recognition. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2000, Bristol, UK, 11–14 September 2000; pp. 70.1–70.10. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, R.; Nedevschi, S. Robust pallet detection for automated logistics operations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications, Rome, Italy, 27–29 February 2016; pp. 470–477. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Huang, B.; Li, C.; Huang, M. Application of convolution neural network object detection algorithm in logistics warehouse. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9053–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaria, M.; Monica, R.; Aleotti, J. A comparison of deep learning models for pallet detection in industrial warehouses. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 3–5 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; Tao, Z.; Wang, F. Pallet detection based on Halcon and AlexNet network for autonomous forklifts. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Internet, Education and Information Technology (IEIT), Suzhou, China, 16–18 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bostelman, R.; Hong, T.; Chang, T. Visualization of pallets. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Robots and Computer Vision XXIV: Algorithms, Techniques, and Active Vision, Boston, MA, USA, 2 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, S.; Kim, M. Real-time positioning and orienting of pallets based on monocular vision. In Proceedings of the 2008 20th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Dayton, OH, USA, 3–5 November 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Pallet recognition and localization using an rgb-d camera. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2017, 14, 1729881417737799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molter, B.; Fottner, J. Real-time pallet localization with 3d camera technology for forklifts in logistic environments. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics (SOLI), Singapore, 31 July–2 August 2018; pp. 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jin, Q.; Huang, B.; Li, C.; Huang, M. Cargo pallets real-time 3D positioning method based on computer vision. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8551–8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhu, B.; Lu, J.; Lang, Y. A point cloud data-driven pallet pose estimation method using an active binocular vision sensor. Sensors 2023, 23, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Hiratsuka, S.; Ohta, M.; Matsubara, H.; Ogawa, M. Small imaging depth LIDAR and DCNN-Based localization for automated guided vehicle. Sensors 2018, 18, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knitt, M.; Schyga, J.; Adamanov, A.; Hinckeldeyn, J.; Kreutzfeldt, J. Estimating the Pose of a Euro Pallet with an RGB Camera based on Synthetic Training Data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.-D.; Hoang, D.D.; Tan, P.X.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Nguyen, T.-U.; Hoang, N.-A.; Phan, K.-T.; Tran, D.-T.; Vu, D.-Q.; Ngo, P.-Q.; et al. Occlusion-robust pallet pose estimation for warehouse automation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 1927–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleznai, C.; Reisinger, L.; Pointner, W.; Murschitz, M. Pallet detection and 3D pose estimation via geometric cues learned from synthetic data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence, Hangzhou, China, 15–17 August 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, N.; Yoshida, H.; Shibata, T. Pallet Pose Estimation Based on Front Face Shot. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 37624–37631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; Kim, Y.; Gee, T.; Nejati, M. Pallet Detection and Localisation from Synthetic Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pages, J.; Armangué, X.; Salvi, J.; Freixenet, J.; Martí, J. A computer vision system for autonomous forklift vehicles in industrial environments. In Proceedings of the 9th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation MEDS, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 27–29 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lecking, D.; Wulf, O.; Wagner, B. Variable pallet pick-up for automatic guided vehicles in industrial environments. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation, Prague, Czech Republic, 20–22 September 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 1169–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivo, L.; Bellomo, N.; Miori, G.; Marcuzzi, E.; Pertile, M.; De Cecco, M. An object localization and reaching method for wheeled mobile robots using laser rangefinder. In Proceedings of the 2008 4th International IEEE Conference “Intelligent Systems” (IS), Varna, Bulgaria, 6–8 September 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivo, L.; Biasi, N.; Biral, F.; Bellomo, N.; Bertolazzi, E.; Da Lio, M.; De Cecco, M. Autonomous pallet localization and picking for industrial forklifts: A robust range and look method. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 085502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molter, B.; Fottner, J. Semi-automatic pallet pick-up as an advanced driver assistance system for forklifts. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference—ITSC, Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 4464–4469. [Google Scholar]

- Seelinger, M.; Yoder, J.-D. Automatic visual guidance of a forklift engaging a pallet. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2006, 54, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R.; Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E.; Teller, S. Closed-loop pallet manipulation in unstructured environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2010), Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 5119–5126. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiogas, E.; Kleitsiotis, I.; Kostavelis, I.; Kargakos, A.; Giakoumis, D.; Bosch-Jorge, M.; Ros, R.J.; Tarazon, R.L.; Likothanassis, S.; Tzovaras, D. Pallet detection and docking strategy for autonomous pallet truck agv operation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 3444–3451. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, A.; Takao, K.; Tsujisaka, R.; Kitajima, K.; Hasegawa, N.; Araki, R. Feasibility study of pallet handling in mixed fleet environment. Mitsubishi Heavy Ind. Tech. Rev. 2021, 58, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Garibott, G.; Masciangelo, S.; Ilic, M.; Bassino, P. Robolift: A vision guided autonomous fork-lift for pallet handling. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS’96, Osaka, Japan, 8 November 1996; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 656–663. [Google Scholar]

- Huemer, J.; Murschitz, M.; Schörghuber, M.; Reisinger, L.; Kadiofsky, T.; Weidinger, C.; Niedermeyer, M.; Widy, B.; Zeilinger, M.; Beleznai, C.; et al. ADAPT: An Autonomous Forklift for Construction Site Operation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iinuma, R.; Kojima, Y.; Onoyama, H.; Fukao, T.; Hattori, S.; Nonogaki, Y. Pallet handling system with an autonomous forklift for outdoor fields. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2020, 32, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iinuma, R.; Hori, Y.; Onoyama, H.; Fukao, T.; Kubo, Y. Pallet detection and estimation for fork insertion with RGB-D camera. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 8–11 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 854–859. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. A flexible new technique for camera calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaar, S.; Brockman, W.; Jang, W. Three-dimensional camera space manipulation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1990, 9, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, N. Precise upright adjustment of panoramic images. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications, Vienna, Austria, 8–10 February 2021; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Paden, B.; Cap, M.; Yong, S.Z.; Yershov, D.; Frazzoli, E. A survey of motion planning and control techniques for self-driving urban vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2016, 1, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [Measurement 0] | [Measurement 1-a] | [Measurement 1-b] | [Measurement 2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | × | ◯ | × | × |

| [36] | ◯ | ◯ | △ | × |

| [32] | × | ◯ | △ | × |

| [37] | × | ◯ | × | × |

| [34] | × | ◯ | △ | × |

| [43] | × | ◯ | × | ◯ |

| [39] | × | ◯ | ◯ | × |

| [38] | × | ◯ | ◯ | × |

| [41] | × | ◯ | ◯ | × |

| Presented | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Target Image | Possible Appearance Area | Expected Length | Probability of Appearing | Edge Strength | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal line detection for zenith correction | Panorama image (Z axis center) | No restriction, i.e., the entire image | Not limited: longer is better | Unknown | Random: stronger is better | |

| Longitudinal line detection for calibration | Panorama image (X axis center & Y axis center) | Can be limited | Limitable: For example, 80% of the length of the limited area | 100% | They should be strong in the area. | |

| yawline detection | Horizontal projection plane image | Can be limited | Limitable: For example, 80% of the length of the limited area | 100% | It should be relatively strong within the area, but the strength will change. | |

| Longitudinal line detection for pitch angle measurement | Unloaded | Panorama image (X axis center) | Can be limited | Limitable: For example, 80% of the length of the limited area | 50% | It should be relatively strong in the area, but its strength is unknown. |

| Loaded | Panorama image (Z axis center) | Can be limited | Limitable: For example, 80% of the length of the limited area | 50% | It should be relatively strong in the area, but its strength is unknown. | |

| GT | Before Improvement | After Improvement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esti. | Esti. − GT | (Esti. − Offset) − GT | Esti. | Esti. − GT | (Esti. − Offset) − GT | ||

| ① | −0.01 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

| ② | −2.34 | −1.50 | 0.84 | 0.33 | −1.87 | 0.47 | 0.10 |

| ③ | 2.61 | 3.27 | 0.65 | 0.14 | 3.02 | 0.41 | 0.04 |

| ④ | −3.38 | −3.07 | 0.31 | −0.20 | −3.12 | 0.26 | −0.11 |

| ⑤ | −5.91 | −5.96 | −0.05 | −0.56 | −5.67 | 0.24 | −0.13 |

| Offset | 0.51 | 0.37 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kita, N.; Kato, T. Approach and Fork Insertion to Target Pallet Based on Image Measurement Method. Sensors 2026, 26, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010154

Kita N, Kato T. Approach and Fork Insertion to Target Pallet Based on Image Measurement Method. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010154

Chicago/Turabian StyleKita, Nobuyuki, and Takuro Kato. 2026. "Approach and Fork Insertion to Target Pallet Based on Image Measurement Method" Sensors 26, no. 1: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010154

APA StyleKita, N., & Kato, T. (2026). Approach and Fork Insertion to Target Pallet Based on Image Measurement Method. Sensors, 26(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010154