A Review of SAW-Based Micro- and Nanoparticle Manipulation in Microfluidics

Abstract

1. Introduction

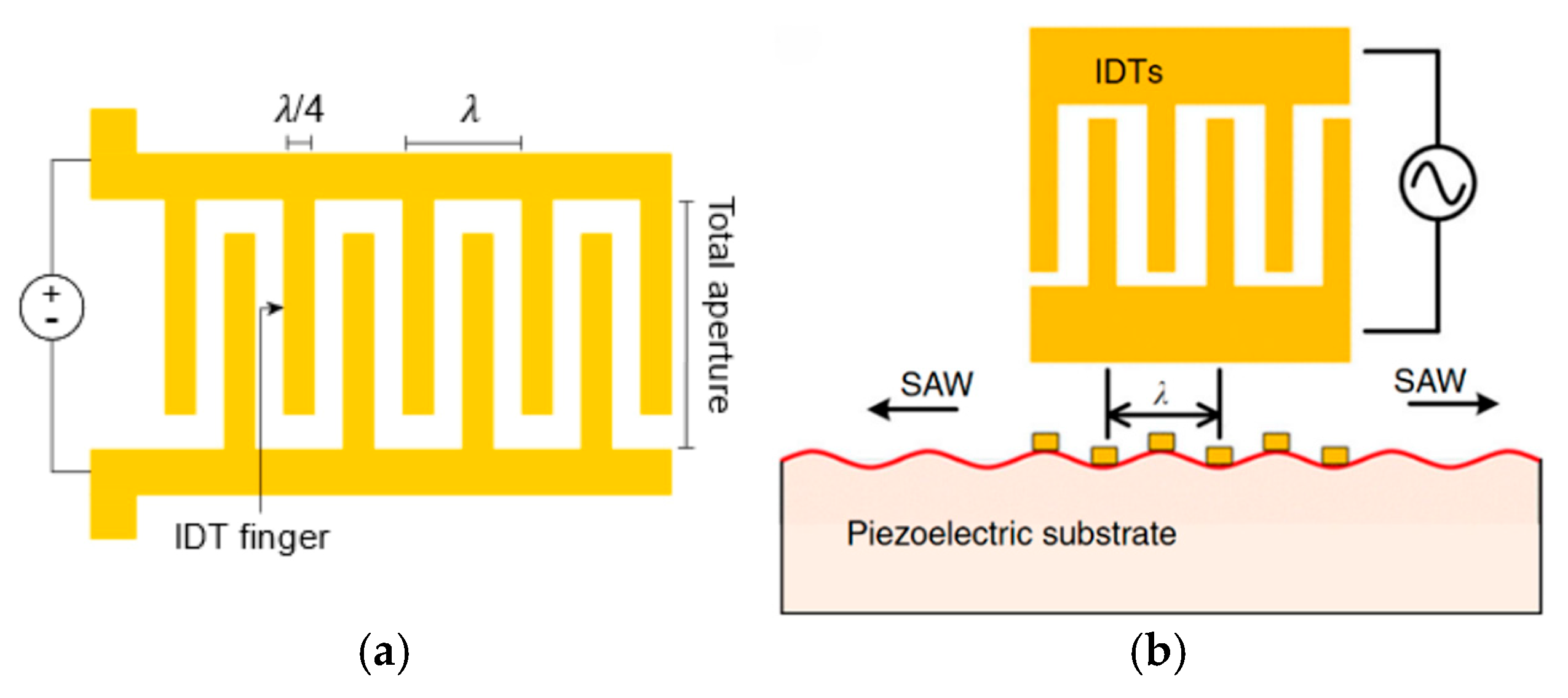

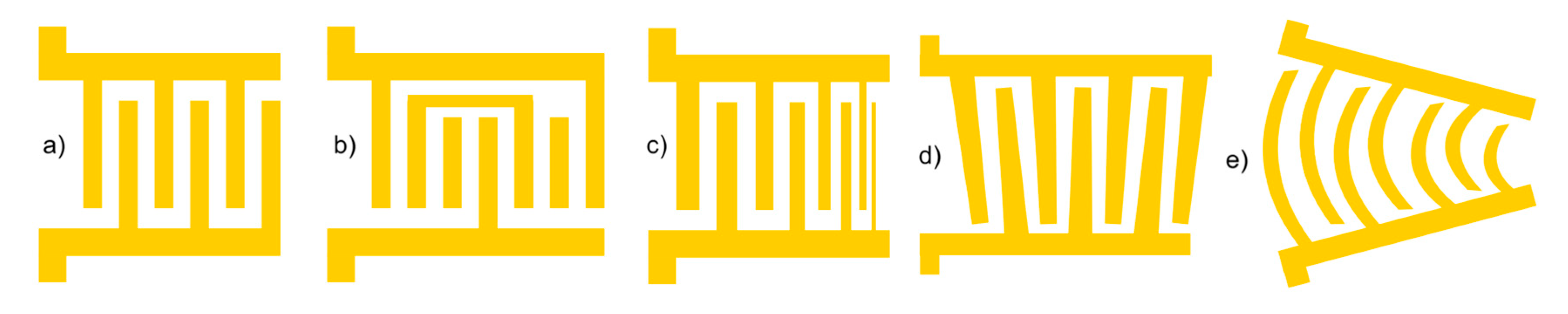

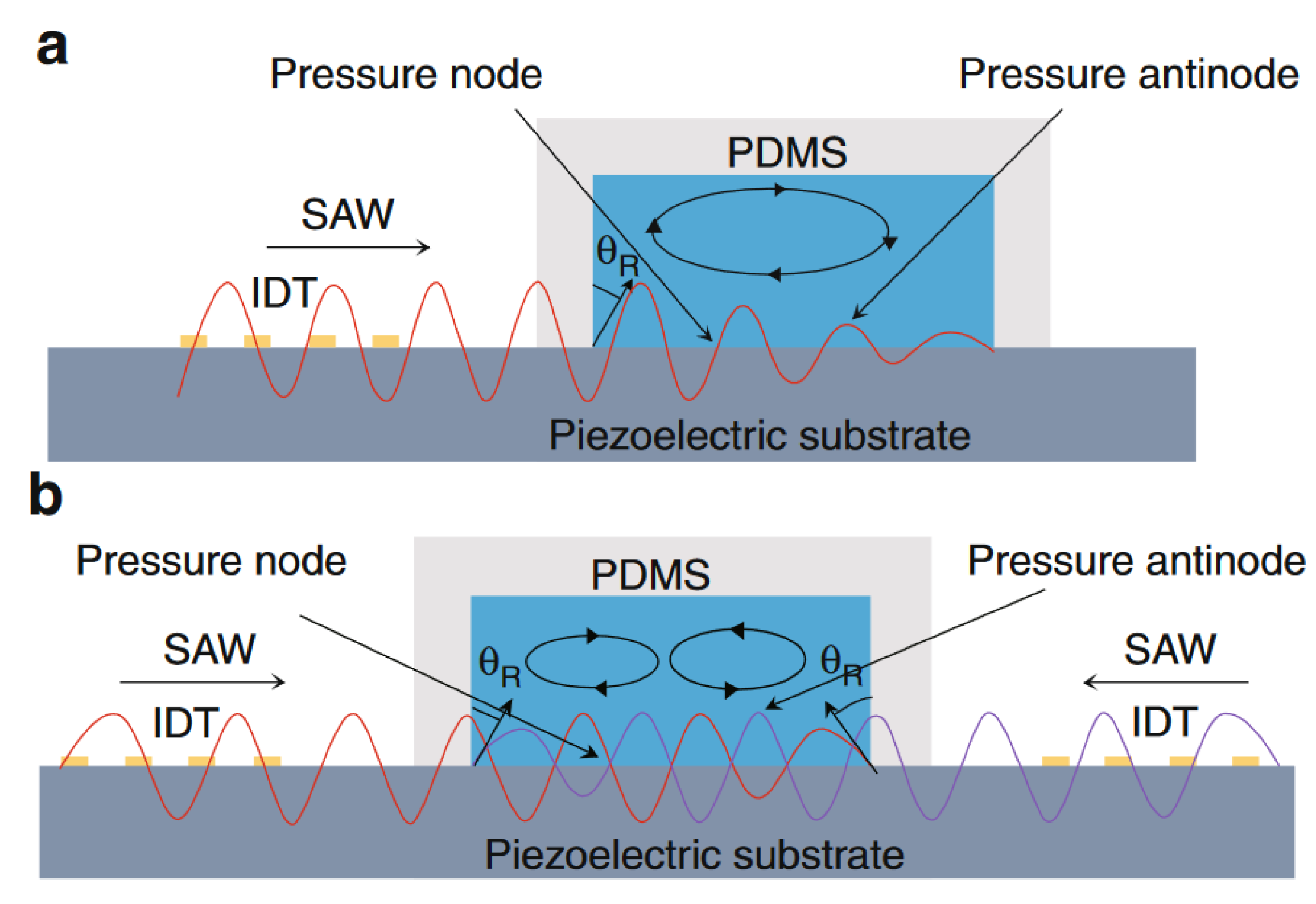

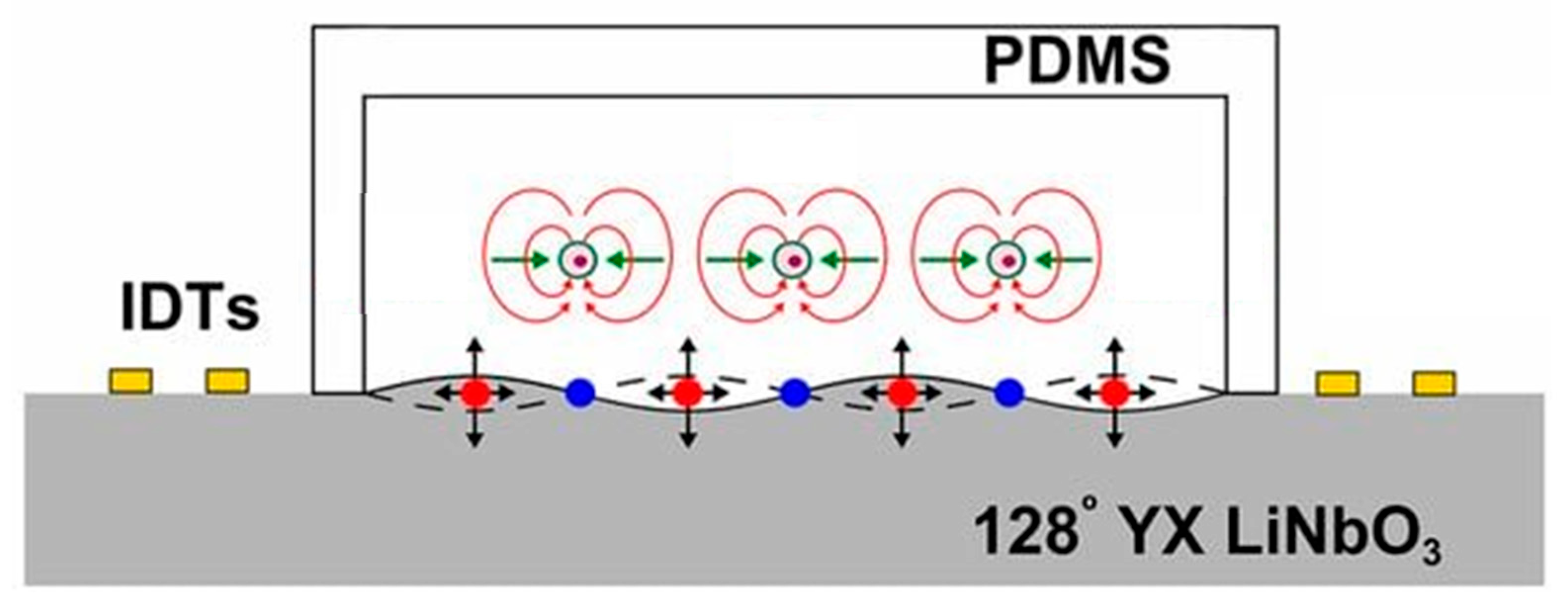

2. SAW Operating Principles

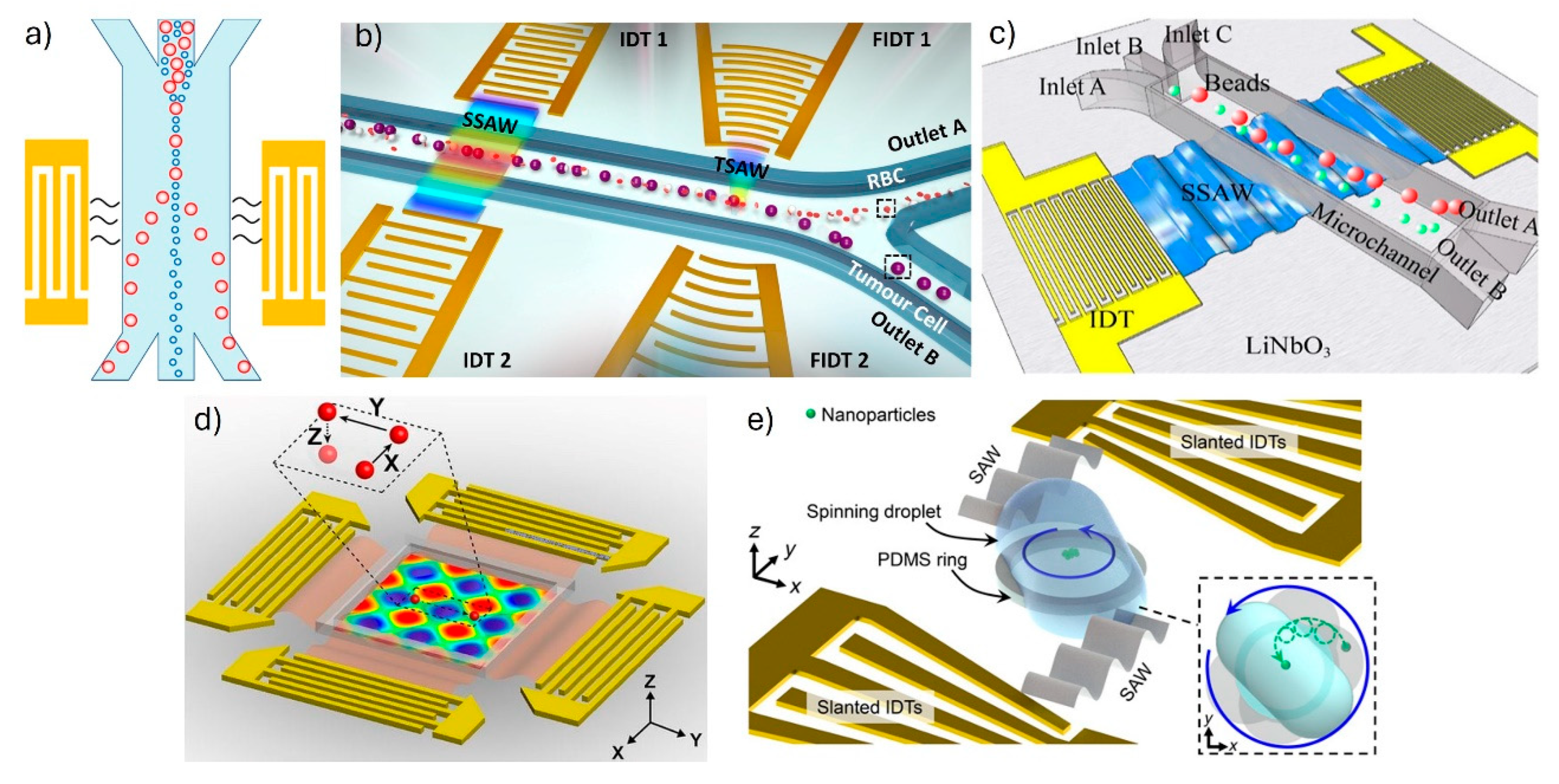

- Floating electrode configuration:

- Chirped IDTs:

- Slanted IDTs:

- Focused IDTs:

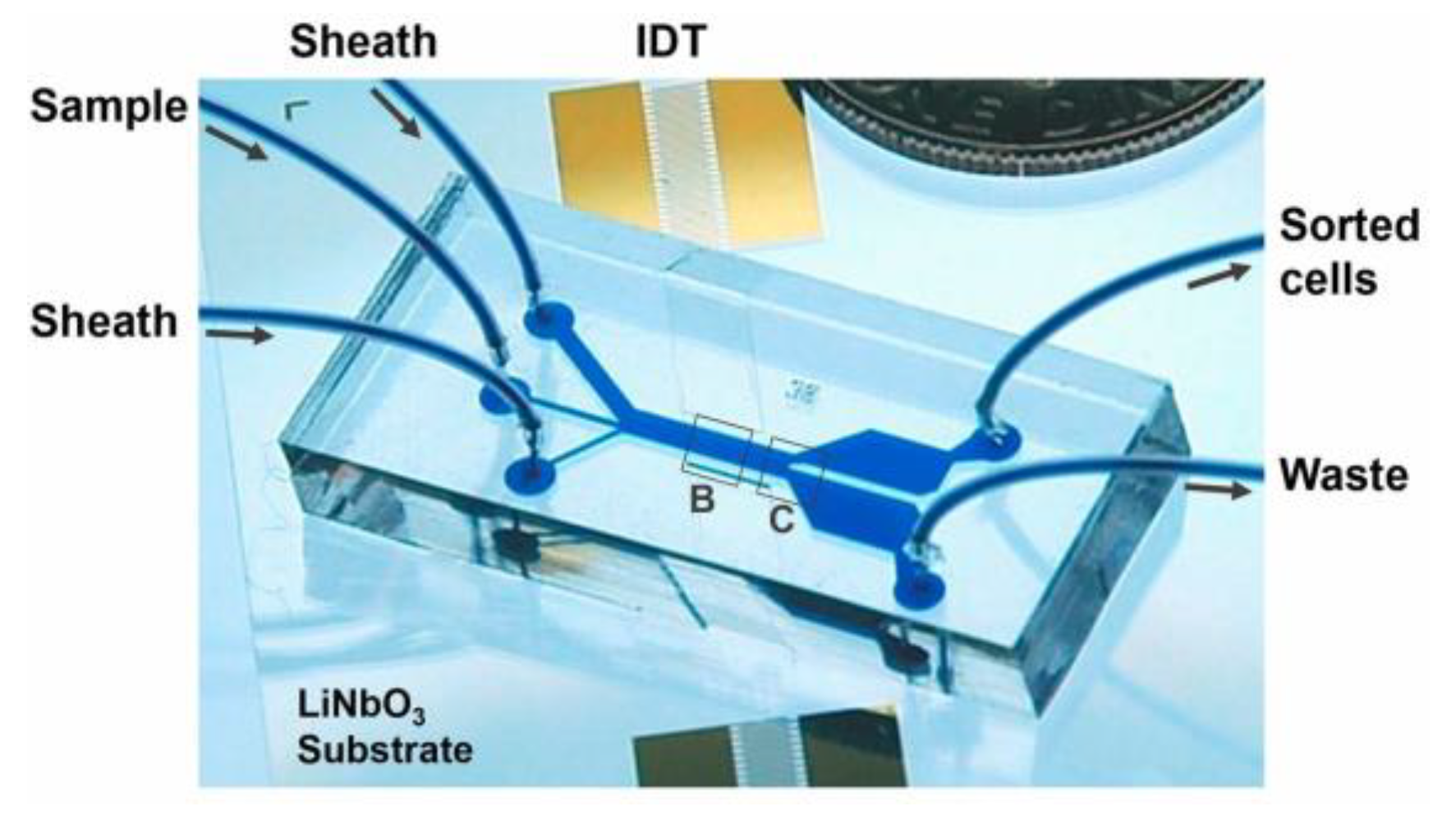

3. Acoustic Actuation in Microfluidics

Governing Equations

4. SAW-Based Microfluidic Devices for Manipulation

5. Discussion

5.1. Materials and Fabrication

5.2. Microfluidic Domain

5.3. SAW Operation Modes

5.4. Working Ranges

5.5. Applications

5.6. Accuracy and Efficiency

5.7. Other Considerations

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hossein, F.; Angeli, P. A review of acoustofluidic separation of bioparticles. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 2005–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, M.; Dang, D.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liang, W. Surface acoustic wave manipulation of bioparticles. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 4166–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, H.; Fallahi, H.; Dai, Y.; Yuan, D.; An, H.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Zhang, J. Multiphysics microfluidics for cell manipulation and separation: A review. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Guo, J.; Fu, Y.; Guo, J. Active microparticle manipulation: Recent advances. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2021, 322, 112616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, R.; Shamloo, A.; Ahadian, S.; Amirifar, L.; Akbari, J.; Goudie, M.J.; Lee, K.; Ashammakhi, N.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Di Carlo, D.; et al. Microfluidic-Based Approaches in Targeted Cell/Particle Separation Based on Physical Properties: Fundamentals and Applications. Small 2020, 16, 2000171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeesh, P.; Sen, A.K. Particle separation and sorting in microfluidic devices: A review. Microfluid. Nanofluidics 2014, 17, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, M.; Lin, Y.; Xu, J. Acoustic Microfluidic Separation Techniques and Bioapplications: A Review. Micromachines 2020, 11, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, S.O.; Silva, L.R.; Mendes, P.M.; Miranda, J.M.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; Minas, G. Piezoelectric actuators for acoustic mixing in microfluidic devices—Numerical prediction and experimental validation of heat and mass transport. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 205, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, S.; Miranda, J.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Minas, G. Numerical prediction of acoustic streaming in a microcuvette. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 92, 1988–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, W.; Lin, Z.; Cai, F.; Li, F.; Wu, J.; Meng, L.; Niu, L.; Zheng, H. Sorting of tumour cells in a microfluidic device by multi-stage surface acoustic waves. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 258, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Peng, Z.; Lin, S.-C.S.; Geri, M.; Li, S.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Dao, M.; Suresh, S.; Huang, T.J. Cell separation using tilted-angle standing surface acoustic waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12992–12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Mao, Z.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, P.-H.; Truica, C.I.; Drabick, J.J.; El-Deiry, W.S.; Dao, M.; et al. Acoustic separation of circulating tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4970–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Y.; Sanders, C.K.; Marrone, B.L. Separation of Escherichia coli Bacteria from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Using Standing Surface Acoustic Waves. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 9126–9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Wu, M.; Yang, S.; Wu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Chen, C.; Ye, J.; Xie, Z.; Tian, Z.; Bachman, H.; et al. A disposable acoustofluidic chip for nano/microparticle separation using unidirectional acoustic transducers. Lab. Chip 2020, 20, 1298–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, F.; Bachman, H.; Cameron, C.E.; Zeng, X.; Huang, T.J. Acoustofluidic bacteria separation. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2017, 27, 015031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, C.; Mao, Z.; Bachman, H.; Becker, R.; Rufo, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Mai, J.; Yang, S.; et al. Acoustofluidic centrifuge for nanoparticle enrichment and separation. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc0467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Ali, M.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, K.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Park, J. Acoustofluidic separation of prolate and spherical micro-objects. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, M.-J.; Sharma, M.; Li, Y.-C.; Lu, Y.-C.; Yu, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-L.; Huang, S.-F.; Chang, L.-B.; Lai, C.-S. Surface Acoustic Wave Sensor for C-Reactive Protein Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Kondoh, J. Feasibility Study on Shear Horizontal Surface Acoustic Wave Sensors for Engine Oil Evaluation. Sensors 2020, 20, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, D.B.; Atashbar, M.Z.; Ramshani, Z.; Chang, H.-C. Surface acoustic wave devices for chemical sensing and microfluidics: A review and perspective. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 4112–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Cai, H.; Ali, M.M.; Tian, X.; Tao, L.; Yang, Y.; Ren, T. Surface acoustic wave devices for sensor applications*. J. Semicond. 2016, 37, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhang, C.; Wei, X. Surface acoustic wave based microfluidic devices for biological applications. Sens. Diagn. 2023, 2, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Lin, F.; Wu, J. Recent advances in acoustofluidic separation technology in biology. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connacher, W.; Zhang, N.; Huang, A.; Mei, J.; Zhang, S.; Gopesh, T.; Friend, J. Micro/nano acoustofluidics: Materials, phenomena, design, devices, and applications. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 1952–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Bachman, H.; Ozcelik, A.; Huang, T.J. Acoustic Microfluidics. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. Palo Alto Calif. 2020, 13, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, S.; Cha, H.; Ouyang, L.; Mudugamuwa, A.; An, H.; Kijanka, G.; Kashaninejad, N.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Zhang, J. Recent microfluidic advances in submicron to nanoparticle manipulation and separation. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 982–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, J.; Lenshof, A.; Laurell, T. Acoustofluidic platforms for particle manipulation. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devendran, C.; Neild, A. Manipulation and Patterning of Micro-objects Using Acoustic Waves. In Field-Driven Micro and Nanorobots for Biology and Medicine; Sun, Y., Wang, X., Yu, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destgeer, G.; Sung, H.J. Recent advances in microfluidic actuation and micro-object manipulation via surface acoustic waves. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 2722–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ozcelik, A.; Rufo, J.; Wang, Z.; Fang, R.; Huang, T.J. Acoustofluidic separation of cells and particles. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2019, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Mandal, N. Saw Sensor Basics on Material, Antenna and Applications: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 5713–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D.; Banerjee, S. Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) Sensors: Physics, Materials, and Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Luo, J.K.; Nguyen, N.T.; Walton, A.J.; Flewitt, A.J.; Zu, X.T.; Li, Y.; McHale, G.; Matthews, A.; Iborra, E.; et al. Advances in piezoelectric thin films for acoustic biosensors, acoustofluidics and lab-on-chip applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 31–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

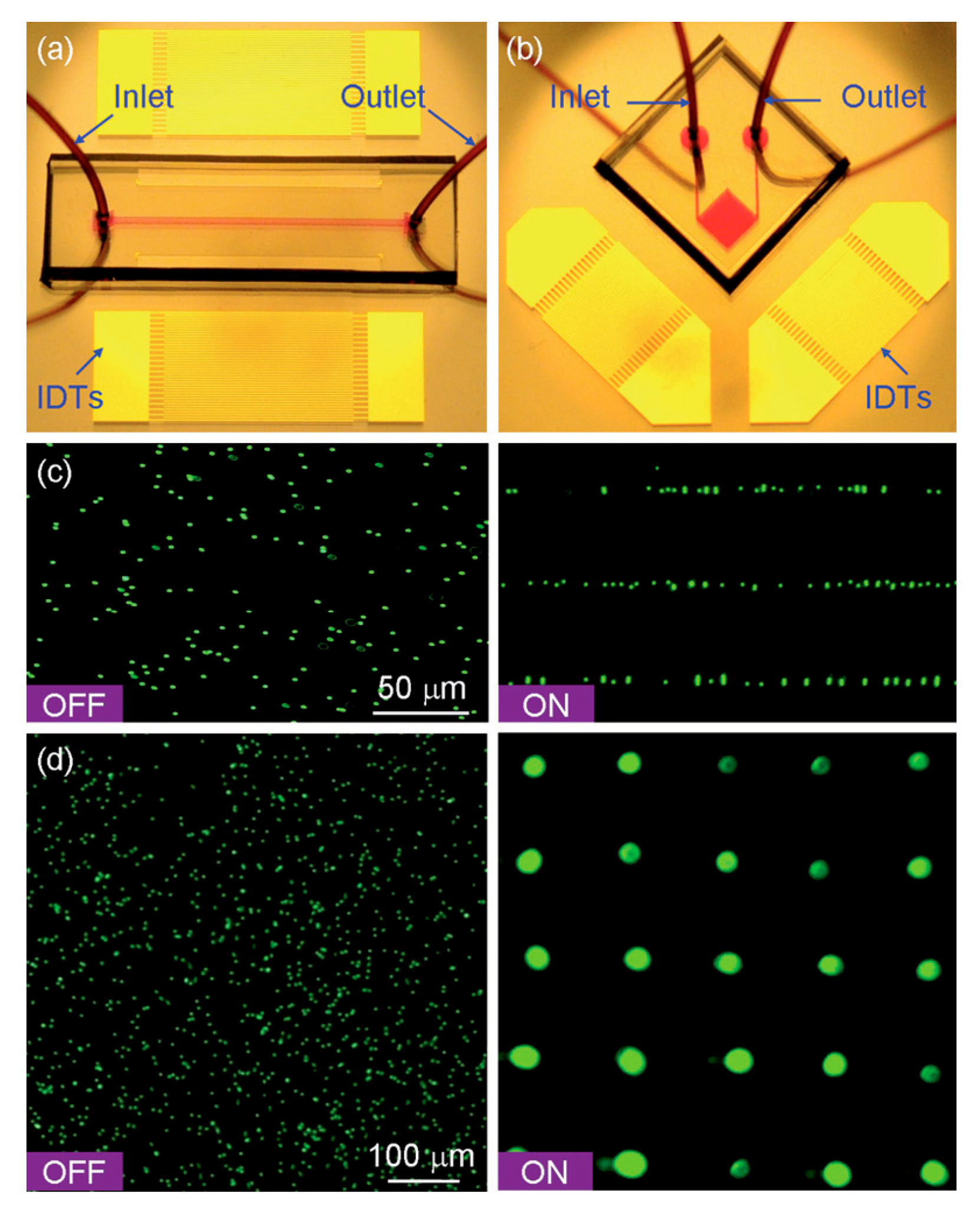

- Mao, Z.; Xie, Y.; Guo, F.; Ren, L.; Huang, P.-H.; Chen, Y.; Rufo, J.; Costanzo, F.; Huang, T.J. Experimental and numerical studies on standing surface acoustic wave microfluidics. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, G.; Andrade, M.A.B.; Reboud, J.; Marques-Hueso, J.; Desmulliez, M.P.Y.; Cooper, J.M.; Riehle, M.O.; Bernassau, A.L. Particle separation by phase modulated surface acoustic waves. Biomicrofluidics 2017, 11, 054115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, S.P.; Mao, Z.; Nama, N.; Gu, Y.; Huang, P.-H.; Jing, Y.; Guo, X.; Costanzo, F.; Huang, T.J. Three-dimensional numerical simulation and experimental investigation of boundary-driven streaming in surface acoustic wave microfluidics. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 3645–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhfouri, A.; Devendran, C.; Ahmed, A.; Soria, J.; Neild, A. The size dependant behaviour of particles driven by a travelling surface acoustic wave (TSAW). Lab Chip 2018, 18, 3926–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Riaud, A. Design of interdigitated transducers for acoustofluidic applications. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2022, 5, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.X.; Chen, C. Low-loss Floating Electrode Unidirectional Transducer for SAW Sensor. Acoust. Phys. 2019, 65, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, P.; Lin, S.C.S.; Stratton, Z.S.; Nama, N.; Guo, F.; Slotcavage, D.; Mao, X.; Shi, J.; Costanzo, F.; et al. Surface acoustic wave microfluidics. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 3626–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ahmed, D.; Mao, X.; Lin, S.-C.S.; Lawit, A.; Huang, T.J. Acoustic tweezers: Patterning cells and microparticles using standing surface acoustic waves (SSAW). Lab Chip 2009, 9, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hu, H.; Lei, Y.; Huang, Q.; Fu, C.; Gai, C.; Ning, J. Optimization Analysis of Particle Separation Parameters for a Standing Surface Acoustic Wave Acoustofluidic Chip. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, G.; Busch, C.; Andrade, M.A.B.; Reboud, J.; Cooper, J.M.; Desmulliez, M.P.Y.; Riehle, M.O.; Bernassau, A.L. Bandpass sorting of heterogeneous cells using a single surface acoustic wave transducer pair. Biomicrofluidics 2021, 15, 014105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, Z. Design and experiment of a focused acoustic sorting chip based on TSAW separation mechanism. Microsyst. Technol. 2020, 26, 2817–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Destgeer, G.; Park, J.; Jung, J.H.; Sung, H.J. Vertical Hydrodynamic Focusing and Continuous Acoustofluidic Separation of Particles via Upward Migration. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.J.; Alan, T.; Neild, A. Particle separation using virtual deterministic lateral displacement (vDLD). Lab Chip 2014, 14, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akther, A.; Marqus, S.; Rezk, A.R.; Yeo, L.Y. Submicron Particle and Cell Concentration in a Closed Chamber Surface Acoustic Wave Microcentrifuge. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 10024–10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, P.-H.; Zhang, R.; Mao, Z.; Chen, C.; Kemeny, G.; Li, P.; Lee, A.V.; Gyanchandani, R.; Armstrong, A.J.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Phenotyping via High-Throughput Acoustic Separation. Small 2018, 14, 1801131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namnabat, M.S.; Zand, M.M.; Houshfar, E. 3D numerical simulation of acoustophoretic motion induced by boundary-driven acoustic streaming in standing surface acoustic wave microfluidics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Rhyou, C.; Kang, B.; Lee, H. Continuously phase-modulated standing surface acoustic waves for separation of particles and cells in microfluidic channels containing multiple pressure nodes. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 165401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Lim, H.; Kim, C.; Kang, J.Y.; Shin, S. Density-dependent separation of encapsulated cells in a microfluidic channel by using a standing surface acoustic wave. Biomicrofluidics 2012, 6, 2412010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wu, W.; Yuan, D.; Zou, S.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Mehmood, K.; Zhang, B. Experimental exploration on stable expansion phenomenon of sheath flow in viscous microfluidics. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 122002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Destgeer, G.; Park, J.; Afzal, M.; Sung, H.J. Sheathless Focusing and Separation of Microparticles Using Tilted-Angle Traveling Surface Acoustic Waves. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 8546–8552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, W. Linear and Nonlinear Constitutive Model for Piezoelectricity in ALEGRA-FE; SAND-2017-11360; Sandia National Lab.: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, J.; Tan, K.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Duan, H.; Fu, Y. A simplified three-dimensional numerical simulation approach for surface acoustic wave tweezers. Ultrasonics 2022, 125, 106797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skov, N.R.; Sehgal, P.; Kirby, B.J.; Bruus, H. Three-Dimensional Numerical Modeling of Surface-Acoustic-Wave Devices: Acoustophoresis of Micro- and Nanoparticles Including Streaming. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 044028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nama, N.; Barnkob, R.; Mao, Z.; Kähler, C.J.; Costanzo, F.; Huang, T.J. Numerical study of acoustophoretic motion of particles in a PDMS microchannel driven by surface acoustic waves. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 2700–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Bachman, H.; Huang, T.J. Acoustofluidic methods in cell analysis. Trends Anal. Chem. TRAC 2019, 117, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Mao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Z.; Lata, J.P.; Li, P.; Ren, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Dao, M.; et al. Three-dimensional manipulation of single cells using surface acoustic waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X. Particle separation in microfluidics using different modal ultrasonic standing waves. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 75, 105603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Chen, M.; Spicer, J.B.; Jiang, X. Acoustics at the nanoscale (nanoacoustics): A comprehensive literature review. Part I: Materials, devices and selected applications. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2021, 332, 112719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, M.; Green, R.; Ohlin, M. Acoustofluidics 14: Applications of acoustic streaming in microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 2012, 12, 2438–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronek, V.; Rambach, R.W.; Schmid, L.; Haase, K.; Franke, T. Particle deflection in a poly(dimethylsiloxane) microchannel using a propagating surface acoustic wave: Size and frequency dependence. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 9955–9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Destgeer, G.; Ha, B.H.; Jung, J.H.; Sung, H.J. Submicron separation of microspheres via travelling surface acoustic waves. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 4665–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D.; Neild, A.; Ai, Y. Highly focused high-frequency travelling surface acoustic waves (SAW) for rapid single-particle sorting. Lab Chip 2015, 16, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, D.J.; Ma, Z.; Han, J.; Ai, Y. Continuous micro-vortex-based nanoparticle manipulation via focused surface acoustic waves. Lab Chip 2016, 17, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Collins, D.J.; Ai, Y. Detachable Acoustofluidic System for Particle Separation via a Traveling Surface Acoustic Wave. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 5316–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Li, P.; Wu, M.; Bachman, H.; Mesyngier, N.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Costanzo, F.; Huang, T.J. Enriching Nanoparticles via Acoustofluidics. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Jang, W.S.; Lim, C.S. Micromixing using a conductive liquid-based focused surface acoustic wave (CL-FSAW). Sens. Actuators Chem. 2018, 258, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Park, J.; Destgeer, G.; Afzal, M.; Sung, H.J. Surface acoustic wave-based micromixing enhancement using a single interdigital transducer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 043702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Back, S.M.; Choi, H.; Nam, J. Acoustic mixing in a dome-shaped chamber-based SAW (DC-SAW) device. Lab Chip 2019, 20, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Enhanced acoustofluidic mixing in a semicircular microchannel using plate mode coupling in a surface acoustic wave device. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2022, 336, 113401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, B.; Lee, S.H.; Iqrar, S.A.; Yi, H.-G.; Kim, J.; Park, J. Rapid acoustofluidic mixing by ultrasonic surface acoustic wave-induced acoustic streaming flow. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 99, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devendran, C.; Gunasekara, N.R.; Collins, D.J.; Neild, A. Batch process particle separation using surface acoustic waves (SAW): Integration of travelling and standing SAW. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 5856–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yazdi, S.; Lin, S.-C.S.; Ding, X.; Chiang, I.-K.; Sharp, K.; Huang, T.J. Three-dimensional continuous particle focusing in a microfluidic channelvia standing surface acoustic waves (SSAW). Lab Chip 2011, 11, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guldiken, R.; Jo, M.C.; Gallant, N.D.; Demirci, U.; Zhe, J. Sheathless Size-Based Acoustic Particle Separation. Sensors 2012, 12, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.C.; Guldiken, R. Particle manipulation by phase-shifting of surface acoustic waves. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2014, 207, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Shao, H.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. Acoustic Purification of Extracellular Microvesicles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2321–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Mao, Z.; Chen, K.; Bachman, H.; Chen, Y.; Rufo, J.; Ren, L.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Huang, T.J. Acoustic Separation of Nanoparticles in Continuous Flow. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1606039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Fu, Y.Q.; Tran, V.-T.; Gautam, A.; Pudasaini, S.; Du, H. Acoustofluidic closed-loop control of microparticles and cells using standing surface acoustic waves. Sens. Actuators Chem. 2020, 318, 128143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Lam, R.H.W.; Lee, J.E.-Y. A two-chip acoustofluidic particle manipulation platform with a detachable and reusable surface acoustic wave device. Analyst 2020, 145, 7752–7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.W.; Neild, A. Multiple outcome particle manipulation using cascaded surface acoustic waves (CSAW). Microfluid. Nanofluidics 2021, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Shen, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; He, F. Continuous separation of particles with different densities based on standing surface acoustic waves. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2022, 341, 113589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Continuous Particle Aggregation and Separation in Acoustofluidic Microchannels Driven by Standing Lamb Waves. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, S.; Baloochi, M.; Cierpka, C.; König, J. On the acoustically induced fluid flow in particle separation systems employing standing surface acoustic waves—Part I. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 2011–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, T.; Wang, C. Three-dimensional modeling and experimentation of microfluidic devices driven by surface acoustic wave. Ultrasonics 2023, 129, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.C.; Guldiken, R. Active density-based separation using standing surface acoustic waves. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2012, 187, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madou, M.J. Fundamentals of Microfabrication: The Science of Miniaturization, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino, V.; Catarino, S.O.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Biomedical microfluidic devices by using low-cost fabrication techniques: A review. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebert, F.; Wege, S.; Massing, J.; König, J.; Cierpka, C.; Weser, R.; Schmidt, H. 3D measurement and simulation of surface acoustic wave driven fluid motion: A comparison. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 2104–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lv, H.; Zhang, Y. A novel study on separation of particles driven in two steps based on standing surface acoustic waves. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 162, 112419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, D. Two-stage particle separation channel based on standing surface acoustic wave. J. Microsc. 2022, 286, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzanzanica, G.; Français, O.; Mariani, S. Surface Acoustic Wave-Based Microfluidic Device for Microparticles Manipulation: Effects of Microchannel Elasticity on the Device Performance. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Duan, X.; Gao, Y. Recent Advances in Acoustofluidics for Point-of-Care Testing. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202300489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husseini, A.A.; Yazdani, A.M.; Ghadiri, F.; Şişman, A. Developing a surface acoustic wave-induced microfluidic cell lysis device for point-of-care DNA amplification. Eng. Life Sci. 2023, 24, e2300230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Gai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Acoustofluidic Actuation of Living Cells. Micromachines 2024, 15, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Nam, H.; Cha, B.; Park, J.; Sung, H.J.; Jeon, J.S. Acoustofluidic Stimulation of Functional Immune Cells in a Microreactor. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, J.; Dervisevic, E.; Devendran, C.; Cadarso, V.J.; O’Bryan, M.K.; Nosrati, R.; Neild, A. High-Frequency Ultrasound Boosts Bull and Human Sperm Motility. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IDT Type | Key Characteristics | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Floating electrode | Incorporates additional unconnected electrodes to reduce insertion loss and enhance unidirectional wave propagation. | High-frequency SAW devices, improved impedance matching, enhanced signal clarity. |

| Chirped | Varies finger spacing for a broad frequency response. | Frequency-tunable SAW devices, precise manipulation, broadband signal processing, acoustic tweezer modulation. |

| Slanted | Gradually decreases finger spacing on one side, enabling frequency-dependent SAW excitation. | Multi-frequency operation, frequency filtering, size-selective manipulation. |

| Focused | Uses curved electrodes to concentrate acoustic energy at a focal point. | High-resolution sensors, precise particle manipulation, acoustic trapping. |

| Team | Year | SAW Type | IDT Design | λSAW (μm) | Microfluidic Domain | Goal | Target Dimensions | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skowronek, Viktor et al. [63] | 2013 | TSAW | 1 slanted IDT Widths = 800 or 1200 or 800 μm Finger pairs = 12 or 65 or 25 | [24.7–16.5] or [10.9–9.1] or [5.6–4.6] | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets. Dimensions: height = 50 μm; width = 200 μm; Flow rate: sample = 120 μL/h | Study deflection, sorting | Microscale: 2, 3, 4.5 and 10 μm PS particles | All beads deflected except 2 μm particles, which followed the flow field. The smaller particles deflected at higher frequencies (265–325 MHz). |

| Destgeer, Ghulam et al. [64] | 2014 | TSAW | 1 focused IDT Finger pairs = 30 Degree of arc = 40° Focal length = 4 mm | 20 or 25 or 30 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets. Dimensions: height = 40 μm; width = 200 or 500 μm; Flow rate: sample = 2.5 μL/h; sheath flow = 22.5 and 100 μL/h | Separation | Micro- and nanoscales: 710 nm, 3, 3.2, 3.4, 4.2, 4.5, 5 μm PS particles | Successful separation of PS particles having size differences as low as 200 nm. |

| Collins, David et al. [65] | 2015 | TSAW | 1 focused IDT Finger pairs = 36 Total proximal aperture = 56 μm Total distal aperture = 210 μm Degree of arc = 26° | 10 | Channel with 3 inlets and 3 outlets. Dimensions: height = 20 μm; width = 40 or 80 μm; Flow rate: sample = 0.5 or 1 μL/min; sheath flow = 3 and 8 μL/min | Rapid Sorting | Microscale: 1, 2, 3 μm particles | Highly focused SAW enabled deterministic sorting with a narrow beam width of 25 μm, frequency of 386 MHz and λ = 10 μm. |

| Collins, David et al. [66] | 2016 | TSAW | 1 focused IDT Finger pairs = 42 Terminal aperture = 14 μm Degree of arc = 26° | 6 or 10 | Channel with 1 inlet and various outlets. Dimensions: height = 20 or 40 μm; width = 160 or 400 μm; Flow rate = 0.45 μL/min | Focusing | Micro- and nanoscales: 1, 2 μm, and 100, 300, 500 nm PS particles | Demonstrated the streaming-induced manipulation of particles with diameter below 1 μm. |

| Ma, Zhichao et al. [67] | 2016 | TSAW | 1 single-electrode IDT Width = λ/4 Spacing = λ/4 | 160 or 80 or 40 | Channel with 2 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 25 μm; width = 400 μm; length = 7 mm Flow rate: sample = 5 μL/min; sheath flow = 8 μL/min | Separation | Microscale: 10 and 15 μm PS particles | Separation efficiency of 98% (for λ = 80 μm). |

| Mao, Zhangming et al. [68] | 2017 | TSAW | 2 chirped IDTs Spacing = [50–160] or [140–330] μm Finger pairs = 20 Total aperture = 30 mm | ≈[202–633] or [570–1209] | Channel with 1 inlet and 1 outlet (static sample) Dimensions: height = 100 or 200 μm; width = 100 or 200 μm; length = 10 mm | Focusing and enrichment | Nanoscale: 80, 200 nm SiO2 and 110, 220 and 500 nm PS particles + streptavidin | Successful focusing of particles of all sizes and detection of streptavidin at a concentration as low as 0.9 nM. |

| Ahmed, Husnain et al. [45] | 2018 | TSAW | 1 single-electrode IDT placed beneath the microchannel Width = 6.5 μm Spacing = 6.5 μm Finger pairs = 20 Total aperture = 0.5 mm | 26 | Channel with 2 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 80 μm; width = 250 μm Flow rate: sample = 50 μL/h; sheath flow = 450 μL/h | Vertical focusing and separation | Microscale: 4.8, 3.2 and 2 μm PS particles | Successful separation of PS particles, presenting purity > 97% and recovery rate > 99%. |

| Fakhfouri, Armaghan et al. [37] | 2018 | TSAW | 1 single-electrode IDT Width = λ/4 Spacing = λ/4 Total aperture = 750 μm | 15 or 21 or 25 or 36 | Channel with 1 inlet and 1 outlet (static sample) Dimensions: height = 26 μm (also studied 9.5 and 35 μm); width = 200 μ; length = 13.5 mm | Study patterning | Micro- and nanoscales: 100, 300, 500 nm, and 1, 2, 3, 5 μm PS particles | Observation of the transition in acoustophoretic behavior of particles based on particle diameter, channel height, frequency, and intensity of the TSAW. |

| Nam, Jeonghun et al. [69] | 2018 | TSAW | 1 focused double-electrode IDT Width = 100 μm Spacing = 100 μm Finger pairs = 20 Degree of arc = 60° | 800 | Channel with 2 inlets and 1 outlet Dimensions: width = 300 μm Flow rate: 5–70 μL/min | Mixing | NA | With an applied voltage of 21 V, the mixing efficiency was greater than approximately 97% at a flow rate of Q ≤ 80 μL/min. |

| Ahmed, Husnain et al. [53] | 2018 | taTSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs placed beneath the microchannel Finger pairs = 20 Total aperture = 0.5 mm Tilted angle = 30° | 19 or 26 | Channel with 1 inlet and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 20 μm; width = 500 μm Flow rate = 5.56 mm/s or 83.3 mm/s | Focusing and separation | Microscale: 4.8 and 3.2 μm PS particles | High purity > 99% at both outlets (lower flow rate), one outlet decrease purity to >93% at higher flow rate. |

| Ahmed, Husnain et al. [70] | 2019 | TSAW | 1 single-electrode IDT placed beneath the microchannel Width = 6.5 μm Spacing = 6.5 μm Finger pairs = 20 Total aperture = 1 mm | 26 | Channel with 2 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 80 μm; width = 250 μm Flow rate = 50–400 μL/min | Mixing | NA | The mixing efficiency reached 100% at 12 Vpp and flow rate of 50 μL/min. As the flow rate was increased to 200 μL/min, the mixing efficiency decreased to 90%. |

| Lim, Hyunjung et al. [71] | 2020 | TSAW | 1 focused IDT Width = 25 μm Spacing = 25 μm Finger pairs = 80 Degree of arc = 10° | 100 | Chamber with 2 inlets and 1 outlet Dimensions: diameter = 3 mm Flow rate: 50–450 μL/min | Mixing | NA | The mixing index (with voltage of 20 V) was greater than 0.9 at a total flow rate of Q ≤ 300 μL/min. |

| Liu, Guojun et al. [44] | 2020 | TSAW | 1 focused IDT Width = 7.5 μm Spacing = 7.5 μm Finger pairs = 35 Degree of arc = 40° Focal length = 4 mm | 30 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 50 μm; width = 300 μm Flow rate: sample = 0.33 mm/s; sheath flow = 3.33 and 0.33 mm/s | Sorting and separation | Microscale: 1 and 10 μm PS particles | Separation and sorting efficiency over 99%. |

| Gu, Yuyang et al. [16] | 2021 | TSAW | 2 slanted IDTs (3 different configurations) Width and spacing decreased from:

| ≈[570–285] or [307–143] or [133–71] | Two configurations: 1. Circular open chamber; 2. Circular open chambers connected by a channel. Dimensions: chamber radius proportional to droplets; channel height = 100 μm; channel width = 200 μm | Enrichment and separation | Nanoscale: Droplets + DNA segments and exosome subpopulations | Achieve isolation of different exosome subpopulations with purity > 80%. |

| Hsu, Jin-Chen and Chang, Chih-Yu [72] | 2022 | TSAW + APM | 2 single-electrode IDTs (1 transducer and 1 receiver) Width = 100 μm Spacing = 100 μm Finger pairs = 20 Total aperture = 1.2 mm | 400 | Channel (semicircular) with 2 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: diameter = 800 μm; length = 6 mm Flow rate: 50–450 μL/min | Mixing | NA | Efficient acoustic mixing for a continuous flow in a semicircular microchannel actuated by SAWs and coupled plate modes. |

| Cha, Beomseok et al. [73] | 2023 | TSAW (parallelpropagation to the flow) | 1 single-electrode IDT placed beneath the microchannel Width = 6.5 μm Spacing = 6.5 μm Finger pairs = 30 Total aperture = 1.5 mm | 26 | Channel with 2 inlets and 1 outlet Dimensions: height = 160 μm; width = 600 μm; length = 12 mm Flow rate: sample = 10 μL/min; sheath flow = 40 μL/min. Also tested flow rates between 50–200 μL/min. | Mixing and cellular lysis | Microscale: 6.1 μm PS particles and human RBC | Rapid, controlled flow mixing at low power (< 6.0 Vrms) and high throughput (∼ 0.2 mL/min) with viscous fluids. High lysis efficiency (> 90%). |

| Khan, Muhammad S. et al. [17] | 2024 | TSAW | 1 slanted IDT Width = λ/4 Spacing = λ/4 Finger pairs = 40 Total aperture = 1 mm | [6.5–8.5] or [5–7] | Channel with 3 inlets and 3 outlets Dimensions: height = 67 μm; width = 500 μm Flow rate: sample = 20 μL/h; sheath flow = 30 and 200 μL/h | Separation by shape | Microscale: 4 and 6 μm microspheres, prolate ellipsoids, and peanut-shaped PS particles/ Thalassiosira eccentrica as bioparticle | High purity and recovery rate of the separated spherical and peanut shaped PS microparticles (percentages details by size in [17]). |

| Devendran, Citsabehsan et al. [74] | 2016 | SSAW + TSAW | 4 chirped IDTs (Two pairs arranged orthogonally to each other) Width = [20–70] μm Finger pairs = 34 Total aperture = 1140 μm | ≈[67–44] or [57–33] | Chamber (static sample) Dimensions: height = 25 μm; width = 707 μm; length = 707 μm | Focusing and separation | Microscale: 3.1, 5.1, and 7 μm PS particles | TSAW component pushed larger particles across the chamber, while smaller particles were collected at the center by SSAW for both mixtures (5.1 and 7 μm, and 5.1 and 3.1 μm). |

| Wang, Kaiyue et al. [10] | 2018 | SSAW + TSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs + 2 focused IDTs Width = λ/4 Spacing = λ/4 | 130 (SSAW) 100 (TSAW) | Channel with 1 inlet and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 50 μm; width = 65 μm Flow rate = 0.3 μL/min | Focusing and separation | Microscale: 2 and 5 μm PS particles + U87 glioma cells and RBCs | 90% ± 2.4% of U87 glioma cells could be isolated from the RBCs. |

| Shi, Jinjie et al. [75] | 2011 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 25 μm Spacing = 25 μm Finger pairs = 20 | 100 | Channel with 1 inlet and 1 outlets Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 50 μm Flow rate = 7 μL/min | 3D focusing (sheathless) | Microscale: 1.9 μm PS particles | The particles are focused laterally and vertically. |

| Nam, Jeonghun et al. [51] | 2012 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 250 μm Spacing = 250 μm | 1000 | Channel with 3 inlets and 5 outlets Dimensions: height = 200 μm; width = 300 μm Flow rate: sample = 8 μL/min; sheath flow = 16 μL/min | Separation by density | Microscale: 150.7 ± 11.3 μm cells encapsulated in alginate beads | More dense beads were collected with a recovery rate of over 97% and a purity of over 98% at a rate of 2300 beads per minute with acceptable cell viability. |

| Guldiken, Rasim et al. [76] | 2012 | SSAW | 4 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 20 | 300 | Channel with 1 inlet and 3 outlets Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 150, 300 μm Flow rate = [0.5–5] μL/min | Focusing and sheathless separation | Microscale: 3, 5, and 10 μm PS particles | Separation of 100% for 10 μm and 94.8% for 3 μm particles (with the lowest flow rate). |

| Ai, Ye et al. [13] | 2013 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 20 Length = 9 mm | 300 | Channel with 3 inlets and 3 outlets Dimensions: height = 25 μm; width = 120 μm; length = 15 mm Flow rate: sample = 0.2 (PS) and 0.5 μL/min (bacteria); sheath flow = 0.8 (PS) and 4 μL/min (bacteria) | Separation | Microscale: 1.2, 5.86 μm synthetic microspheres + Escherichia coli bacteria, peripheral blood mononuclear cells | The purity of separated E. coli bacteria was 95.65% |

| Jo, Myeong Chanand and Guldiken, Rasim [77] | 2014 | SSAW (phase shift) | 4 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 25 | 300 | Channel with 1 inlet and 3 outlets Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 150 μm | Manipulation | Microscale: 5 μm PS particles | The particle displacement changed almost linearly as a function of the phase-shift. |

| Ding, Xiaoyun et al. [11] | 2014 | taSSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 50 μm Spacing = 50 μm Finger pairs = 24 Tilted angle = 15° Total aperture = 4 mm | 200 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 75 μm; width = 1 μm; length = 4 mm Flow rate: sample (PS) = 1.50 mm/s; sample (MCF-7) = 2 μL/min | Separation | Microscale: 2, 7.3, 9.9 and 10 μm PS particles + MCF-7 breast cancer cells and WBCs | Separation efficiency of 97% for 9.9 μm and 7.3 μm and 99% for 2 and 10 μm. MCF-7 recovery rate of 71% and purity of 84%. |

| Lee, Kyungheon et al. [78] | 2015 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 25 μm Spacing = 25 μm Length = 5.2 mm | 100 | Channel with 3 inlets and 3 outlets Dimensions: height = 80 μm; width = 60 μm Flow rate = 2.8 mm/s | Separation | Nanoscale: 190 nm, 1000 nm PS particles + Exosomes, larger microvesicles + microvesicles, red blood cells | > 90% separation yields (PS particles) + recovery rate > 80% for exosomes and > 90% for microvesicles. |

| Li, Peng et al. [12] | 2015 | taSSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 50 μm Spacing = 50 μm Length = 10 mm Tilted angle = 5° | 200 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 110 μm; width = 800 μm; length = 10 mm Flow rate: sample = 20 μL/min; sheath flow = 50 μL/min | Separation | Microscale: CTCs (average diameters of 16 or 20 μm) and WBCs (∼12 μm) | Cancer cell recovery rate was > 83% (83–96%) and WBC removal rate was ∼90%. |

| Guo, Feng et al. [59] | 2016 | SSAW (phase shift) | 4 single-electrode IDTs (Two pairs arranged orthogonally to each other) Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 40 Total aperture = 1 cm | 300 | Chamber (static sample) Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 1.8 mm; length = 1.8 mm | 3D trapping and manipulation | Microscale: 1, 4.2, 7.3, and 10.1 μm PS particles + 3T3 mouse fibroblast, HeLa S3 cellse | Manipulation of a single cell or particle placing it at a desired location with 1 µm accuracy in the x–y plane and 2 µm accuracy in the z direction. |

| Mao, Zhangming et al. [34] | 2016 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 30 | 300 | Channel with 1 inlet and 1 outlet Dimensions: height = 60 μm; width = 170, or 340 μm Flow rate = 10 μL/min | Study manipulation in narrow channels | Microscale: 10.11 μm PS and PDMS particles | The 2D SSAW microfluidic model developed matched the experiments, whereas the 1D harmonic standing waves model failed in the predictions. |

| Wu, Mengxi et al. [79] | 2017 | taSSAW | 2 IDTs with floating electrodes Width = 10 μm Spacing = 10 μm Finger pairs = 80 Tilted angle = 15° | 120 | Channel with 2 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 800 μm Flow rate: sample = 4 μL/min; sheath flow = 12 μL/min | Deflection and separation | Nanoscale: 110, 220, 240, 500, 600, 700 and 900 nm PS particles | For 900 and 600 nm particles, the removal rates were 96.6% and 80.4%, respectively. The recovery rates for 220 and 110 nm particles were 85.6% and 90.7%. |

| Lee, Junseok et al. [50] | 2017 | SSAW (phase shift) | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = λ/4 Spacing = λ/4 Finger pairs = 23 | 285 | Channel with 2 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 80 μm; width = 1050 μm Flow rate: sample = 5 μL/min; sheath flow = 5 μL/min | Separation | Microscale: 2, 6, and 12 μm PS particles + Human Keratinocytes (HaCaT) | Cell-bead mixture (2 μm PS and HaCaT) was separated with 83% efficiency. |

| Simon, Gergely et al. [35] | 2017 | SSAW (phase shift) | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 20 | 300 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 50 μm; width = 240 μm; length = 2 cm | Separation | Microscale: 4.5, 5, 6, 10, and 15 μm PS particles | Efficiency of 90% (separating 10–15 µm) and 75% (separating 5–6 µm). |

| Li, Sixing et al. [15] | 2017 | taSSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 50 μm Spacing = 50 μm Tilted angle = 15° | 200 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 75 μm; width = 1000 μm Flow rate: sample = 0.5 or 1 μL/min; sheath flow = 7 and 9 μL/min | Separation | Microscale: Escherichia coli bacteria (2 μm × 0.25–1.0 μm), RBCs (≈6.2–8.2 μm) and human blood samples | E. coli was separated from RBCs with a purity of more than 96%. |

| Nguyen, Tan Dai et al. [80] | 2020 | SSAW (phase shift) | 4 single-electrode IDTs (two pairs arranged orthogonally to each other) Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 60 Total aperture = 1 cm | 300 | Chamber (static sample) Dimensions: height = 100 (2D), 1000 (3D) μm; width = 1.5 mm; length = 1.5 mm | 3D manipulation | Microscale: 10, 20 μm PS particles + Breast cancer cells (MCF-7) | Successfully relocated targets to specified coordinates. |

| Qian, Jingui et al. [81] | 2020 | SSAW—Lamb waves | 4 chirped IDTs (two pairs arranged orthogonally to each other) Width = [50–75] μm Finger pairs = 26 Total aperture = 4.4 cm | ≈[210–285] | Chamber (static sample) Dimensions: height = 50 μm; diameter = 1000 μm; sidewall width = 1 mm | 2D manipulation in a single-use microfluidic chamber | Microscale: 5, 9 and 13 μm PS particles | Successfully shifted the position of microbeads on the disposable microchamber. |

| Zhao, Shuaiguo et al. [14] | 2020 | taSSAW | 2 IDTs with floating electrodes Width = 10 μm Spacing = 10 μm Finger pairs = 80 Tilted angle = 15° | 120 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 75 μm; width = 800 μm Flow rate: sample = 2 μL/min; sheath flow = 2 and 6 μL/min | Deflection and separation | Micro- and nanoscale: 110 nm, 400 nm, 1 μm, 2, 4.5, 6, and 10 PS particles, 660 nm SiO2 and 200 nm Ag particles + E. coli and human RBCs | Separation purity of up to 96% when separating E. coli from human RBCs. |

| Simon, Gergely et al. [43] | 2021 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm | 300 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 50 μm; width = 240 μm Flow rate: sample = 0.15 μL/min; sheath flow = 0.4 and 0.5 μL/min | Sorting | Microscale: 1, 6, 10, and 14.5 μm PS particles + RBCs, white blood cells | Purity and efficiency coefficients above 75 ± 6% and 85 ± 9% (for particles with 6, 10, and 14.5 μm) + 78 ± 8% efficiency and 74 ± 6% purity (for blood cells and 1 μm particle). |

| Ng, Jia Wei and Neild, Adrian [82] | 2021 | Cascaded SSAW | 3 pairs of single-electrode IDTs Width = 25 μm Spacing = 25 μm Total aperture = 1 mm IDTs pairs distance = 12.5 λ | 100 | Channel with 3 inlets and 4 outlets Dimensions: height = 25 μm; width = 200 μm Flow rate: sample = 5 μL/min; sheath flow = 2 μL/min | Sorting and separation controlling multiple particle trajectories | Microscale: 5 μm PS particles | The particles were sorted into four distinct outlets using different actuation combinations. |

| Liu, Guojun et al. [83] | 2022 | taSSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 50 μm Spacing = 50 μm Finger pairs = 50 Tilted angle = 15° | 200 | Channel with 3 inlets and 3 outlets Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 500 μm Flow rate (for the authors’ best results): sample = 1.39 μL/min; sheath flow = 3.47 and 13.89 μL/min | Separation by density | Microscale: 10 μm PS particles, PMMA and SiO2 microspheres | Separation rates were 94.86%, 92.21%, and 90.36%, and the separation purities were 93.24%, 89.07%, and 91.81% for SiO2, PMMA, and PS particles, respectively. |

| Hsu, Jin-Chen and Chang, Chih-Yu [84] | 2022 | SSAW—Lamb waves | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 100 μm Spacing = 100 μm Finger pairs = 20 Total aperture = 4.4 mm | 400 | For aggregation: channel with 2 inlets and 2 outlets; dimensions: height = 60 μm; width = 500 μm Flow rate = 4 μL/min For separation: channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets; dimensions: height = 60 μm; width = 300 or 600 μm Flow rate: sample = 3 μL/min; sheath flow = 1 μL/min | Aggregation and separation | Microscale: 2, 7, and 10 μm PS particles | Separation of 2 and 10 μm particles with a manual estimation of the separation rate > 90%. |

| Sachs, Sebastian et al. [85] | 2022 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs (3 different configurations) Width Spacing = 20 or 90 or 150 μm Finger pairs = variable Total aperture = 2 mm | 20 or 90 or 150 | Channel with 1 inlet and 1 outlet Dimensions: height = 85 or 185 or 530 μm; width = 500 μm; length = 800 μm Flow rate = [0.15–4] μL/min | To study channel height and SAW wavelength impact on separation | Micro- and nanoscale: 0.55, 1.14, μm PS particles | The numerical model optimized based on experimental data showed that shallow microchannels and large wavelengths are advantageous for particle separation. |

| Han, Junlong et al. [42] | 2023 | taSSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 44 μm Spacing = 44 μm Tilted angle = 15° Total aperture = 6 mm | 175 | Channel with 3 inlets and 2 outlets Dimensions: height = 100 μm; width = 800 μm; length = 8 mm Flow rate: sample = 2 μL/min; sheath flow = 2 and 6 μL/min | Separation | Micro- and nanoscale: 1, 3, 6 μm, and 100 nm PS particles + 750 nm SiO2 particles | In the different experiments, the separation purity was 80 to 95% and the separation efficiency (yield) was 83 to 97%. (depending on size and flow rate). |

| Liu, Xia et al. [86] | 2023 | SSAW | 2 single-electrode IDTs Width = 75 μm Spacing = 75 μm Finger pairs = 20 | 300 | Channel with 1 inlet and 1 outlet (static sample) Dimensions: height = 70 μm; width = 500 μm | Study precise 3D motion control | Micro- and nanoscale: 0.5, 5, and 10 μm PS particles | They demonstrated that micro- and nanoparticles can move in three dimensions when acoustic radiation force and acoustic streaming interact. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amorim, D.; Sousa, P.C.; Abreu, C.; Catarino, S.O. A Review of SAW-Based Micro- and Nanoparticle Manipulation in Microfluidics. Sensors 2025, 25, 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051577

Amorim D, Sousa PC, Abreu C, Catarino SO. A Review of SAW-Based Micro- and Nanoparticle Manipulation in Microfluidics. Sensors. 2025; 25(5):1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051577

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmorim, Débora, Patrícia C. Sousa, Carlos Abreu, and Susana O. Catarino. 2025. "A Review of SAW-Based Micro- and Nanoparticle Manipulation in Microfluidics" Sensors 25, no. 5: 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051577

APA StyleAmorim, D., Sousa, P. C., Abreu, C., & Catarino, S. O. (2025). A Review of SAW-Based Micro- and Nanoparticle Manipulation in Microfluidics. Sensors, 25(5), 1577. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051577