Sensor-Based Assessment of Post-Stroke Shoulder Pain and Balance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

Ethical Considerations

2.2. Assessment Tools

2.2.1. Pain Assessment

2.2.2. Balance Assessment

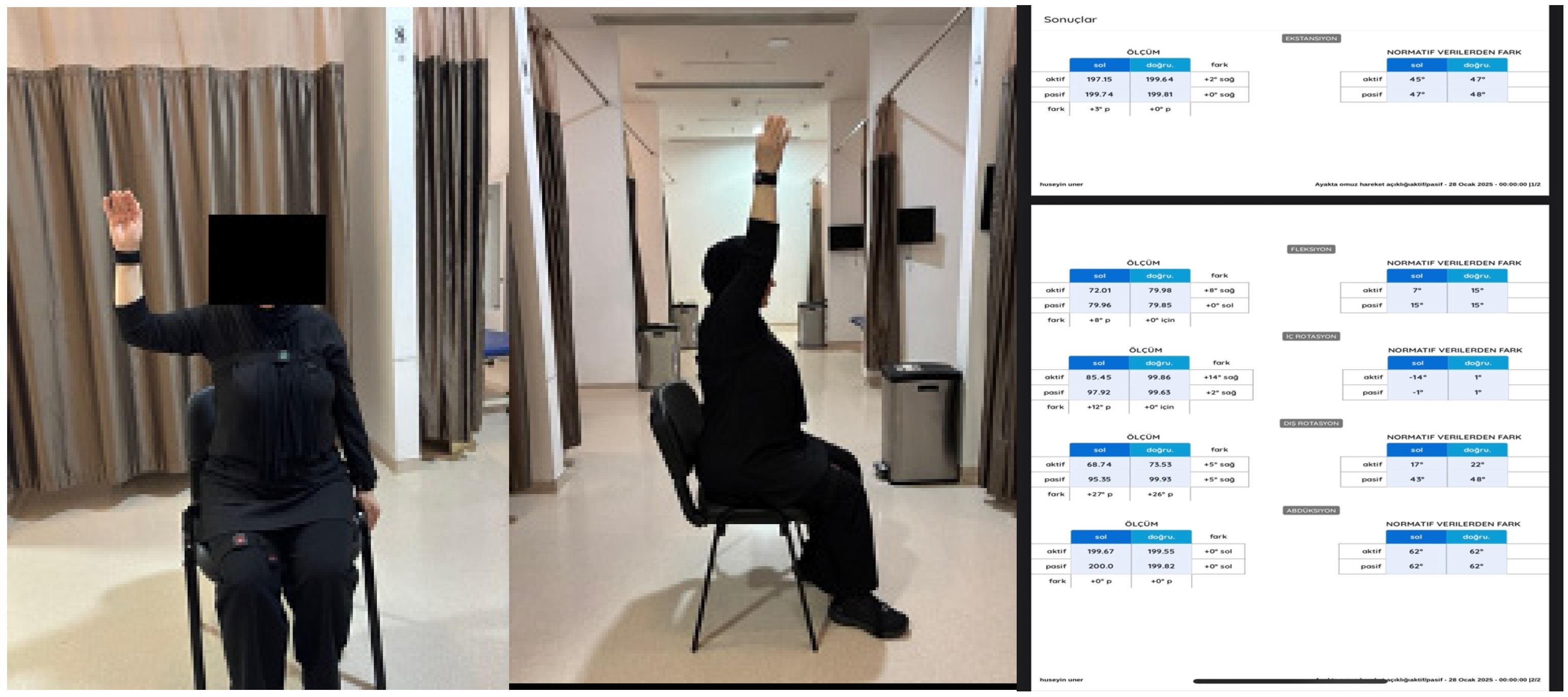

2.2.3. Sensor-Based Assessment

- Center of Pressure (CoP) displacement (mm): total distance traveled by the CoP during the test;

- Sway velocity (mm/s): average velocity of CoP movement, indicating postural stability;

- Root Mean Square (RMS) amplitude (mm): variability of sway around the mean CoP position;

- Symmetry index (%): weight distribution ratio between the affected and unaffected sides;

- Fall-risk index (score): a composite indicator generated by the system’s algorithm, integrating sway variability and CoP dispersion.

- Root Mean Square (RMS) sway amplitude—overall magnitude of postural sway;

- Mediolateral (ML) deviation—average and maximum displacement in the frontal plane;

- Anteroposterior (AP) deviation—average and maximum displacement in the sagittal plane;

- Median sway values—central tendency of sway, less affected by outliers.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Clinical Assessments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birschel, P.; Ellul, J.; Barer, D. Progressing Stroke: Towards an Internationally Agreed Definition. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2003, 17, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, K.K.; Faria, C.D.; Scianni, A.A.; Avelino, P.R.; Faria-Fortini, I.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F. Previous lower limb dominance does not affect measures of impairment and activity after stroke. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 53, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atasever, N. Kronik İnme Hastalarında Gövde Kontrolü Ve Alt Ekstremite Motor Koordinasyonunun Fonksiyonel Denge ve Yürüyüşün Zaman Mesafe Karakteristikleri ile İlişkisinin İncelenmesi. Master’s Thesis, Hacettepe Üniversitesi, Ankara, Turkey, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Szopa, A.; Domagalska-Szopa, M.; Lasek-Bal, A.; Zak, A. The Link Between Weight Shift Asymmetry and Gait Disturbances in Chronic Hemiparetic Stroke Patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P. Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain in People with Stroke: Present and the Future; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019; Volume 9, pp. 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.-K.; Wu, C.-H.; Özçakar, L. Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain: A Narrative Review. Rehabil. Pract. Sci. 2025, 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I.; Lexell, J.; Jönsson, A.-C.; Brogardh, C. Left-Sided Hemiparesis, Pain Frequency, and Decreased Passive Shoulder Range of Abduction are Predictors of Long-Lasting Poststroke Shoulder Pain. PMR J. Inj. Funct. Rehabil. 2012, 4, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Cui, L.; Bao, Y.; Gu, L.; Pan, H.; Wang, J.; Xie, Q. Prevalence, Risk Factor and Outcome in Middle-Aged and Elderly Population Affected by Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain: An Observational Study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1041263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalichman, L.; Ratmansky, M. Underlying Pathology and Associated Factors of Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 90, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatooni, M.; Dehghankar, L.; Samiei Siboni, F.; Bahrami, M.; Shafaei, M.; Panahi, R.; Amerzadeh, M. Association of Post-Stroke Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain with Sleep Quality, Mood, and Quality of Life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2025, 23, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.-C.; Cheng, P.-T.; Chen, C.-L.; Chen, S.-C.; Chung, C.-Y.; Yeh, T.-H. Effects of Balance Training on Hemiplegic Stroke Patients. Chang Gung Med. J. 2002, 25, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baierle, T.; Kromer, T.; Peterman, C.; Magosch, P.; Luomajoki, H. Balance Ability and Postural Stability Among Patients with Painful Shoulder Disorders and Healthy Controls. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi, L.-A.; Klerk, S.; Tapfurma, M. Occupational Therapy Intervention For Hemiplegia Shoulder Pain in Adults Post-Stroke: A Zimbabwean Perspective. S. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 51, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, I.S., IV; Guimaraes, M.; Ribeiro, T.; Gonçalves, A.; Natario, I.; Torres, M. Retrospective Cohort Study on the Incidence and Management of Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain in Stroke Inpatients. Cureus 2024, 16, e76030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayretli Atan, S.; Pehlivan, E. The Effect of Hemıplegıc Shoulder Pain on Balance, Upper Extremıty Functıonalıty, Descrıptıve Data of Partıcıpants and Qualıty of Lıfe. J. Selcuk. Health 2025, 6, 260–275. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, D.A.; Lambert, B.S.; Boutris, N.; Mcculloch, P.C.; Robbins, A.B.; Moreno, M.R.; Harris, J.D. Validation of Digital Visual Analog Scale Pain Scoring with A Traditional Paper-Based Visual Analog Scale in Adults. JAAOS Glob. Res. Rev. 2018, 2, E088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, F.; Büyükavci, R.; Sağ, S.; Doğu, B.; Kuran, K.B. Berg Denge Ölçeği’nin Türkçe Versiyonunun Inmeli Hastalarda Geçerlilik Ve Güvenilirliği. Türkiye Fiz. Tıp Rehabil. Derg. 2013, 59, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Leardini, A.; Lullini, G.; Giannini, S.; Berti, L.; Ortolani, M.; Caravaggi, P. Validation of the Angular Measurements of A New Inertial-Measurement-Unit Based Rehabilitation System: Comparison With State-of-The-Art Gait Analysis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frykberg, G.; Lindmark, B.; Lanshammar, H.; Borg, J. Correlation Between Clinical Assessment and Force Plate Measurement of Postural Control After Stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 2007, 39, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, J.-W.; Chou, C.-X.; Hsieh, Y.-W.; Wu, W.-C.; Yu, M.-Y.; Chen, P.-C.; Chang, H.-F.; Ding, S.-E. Randomized Comparison Trial of Balance Training by Using Exergaming and Conventional Weight-Shift Therapy in Patients With Chronic Stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupo, A.; Cinnera, A.M.; Pucello, A.; Iosa, M.; Coiro, P.; Personeni, S.; Gimigliano, F.; Iolascon, G.; Paolucci, S.; Morone, G. Effects on Balance Skills and Patient Compliance of Biofeedback Training With Inertial Measurement Units and Exergaming in Subacute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Funct. Neurol. 2018, 33, 1136. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir, J.; Mestenza Mattos, F.G.; Torchio, A.; Corrini, C.; Cattaneo, D. Fallers After Stroke: A Retrospective Study to Investigate the Combination of Postural Sway Measures and Clinical Information in Faller’s Identification. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1157453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group 1 N (%) | Group 2 N (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 32 (59.3) | 34 (63) | 0.554 |

| Female | 22 (40.7) | 20 (37) | |

| Dominant Side | |||

| Right | 52 (96.3) | 52 (96.3) | 0.310 |

| Left | 2 (3.7) | 2 (3.7) | |

| Hemiplegic Side | |||

| Right | 25 (46.3) | 25 (46.3) | 0.123 |

| Left | 29 (53.7) | 29 (53.7) | |

| Smoking Status | |||

| Yes | 14 (25.9) | 12 (22.2) | 0.654 |

| No | 40 (74.1) | 42 (77.8) | |

| Lesion Site | |||

| Cortical | 24 (44.4) | 17 (31.5) | |

| Subcortical | 19 (35.2) | 24 (44.4) | 0.378 |

| Cortical + Subcortical | 11 (20.4) | 13 (24.1) | |

| Chronic Diseases | |||

| Hypertension | 18 (33.3) | 16 (29.6) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 7 (13) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Hearth Disease | 3 (5.6) | 0 (0) | |

| HT + DM | 10 (18.5) | 14 (25.6) | 0.101 |

| HT + Heart Disease | 4 (7.4) | 3 (5.6) | |

| DM + Heart Disease | 4 (7.4) | 4 (7.4) |

| Group 1 (N = 54) Mean ± SS (Min–Max) | Group 2 (N = 54) Mean ± SS (Min–Max) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 64.25 ± 9.52 (46–80) | 66.09 ± 9.92 (45–80) | 0.20 |

| Disease Duration (Months) | 10.04 ± 6.68 (3–13) | 10.17 ± 5.99 (3–23) | 0.650 |

| Group 1 (N = 54) | Group 2 (N = 54) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active shoulder flexion | p | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| r | 0.467 | 0.461 | |

| Passive shoulder flexion | p | 0.018 | 0.110 |

| r | 0.323 | 0.348 | |

| Active shoulder abduction | p | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| r | 0.483 | 0.400 | |

| Passive shoulder abduction | p | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| r | 0.390 | 0.361 | |

| Active shoulder internal rotation | p | 0.000 | 0.012 |

| r | 0.524 | 0.342 | |

| Passive shoulder internal rotation | p | 0.310 | 0.245 |

| r | 0.297 | 0.165 | |

| Active shoulder external rotation | p | 0.001 | 0.052 |

| r | 0.456 | 0.268 | |

| Passive shoulder external rotation | p | 0.363 | 0.004 |

| r | 0.007 | 0.390 |

| Group 1 (N = 54) Mean ± SS (Min–Max) | Group 2 (N = 54) Mean ± SS (Min–Max) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder VAS Activity Score | 6.00 ± 1.86 (0–9) | — | 0.00 |

| Shoulder VAS Rest Score | 2.85 ± 1.84 (0–6) | — | 0.00 |

| Berg Balance Scale Score | 20.96 ± 8.71 (6–52) | 34.58 ± 11.71 (6–52) | 0.928 |

| VAS Activity Score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Berg Balance Score | p | 0.043 |

| r | 0.196 |

| GK Sway Medyan | GK Sagittal Medyan | GK Sagittal Maks | GK Frontal Medyan | GK RMS Medyan | GK Frontal Maks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg Balance Scale | r | −0.520 | −0.278 | −0.561 | −0.331 | −0.352 | −0.490 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| VAS Activity Score | r | 0.018 | 0.112 | 0.324 | −0.550 | 0.501 | 0.291 |

| p | 0.854 | 0.247 | 0.001 | 0.575 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| GA Sway (RMS) | GA Sagittal Median | GA Sagittal Max | GA Frontal Max | GA Frontal Median | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg Balance Scale | r | −0.259 | −0.112 | −0.135 | −0.210 | −0.137 |

| p | 0.007 | 0.252 | 0.167 | 0.300 | 0.160 | |

| VAS Activity Score | r | 0.547 | 0.271 | 0.293 | 0.450 | 0.315 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Static Fall Risk | Dynamic Fall Risk | Balance | Strength | Mobility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg Balance Scale | r | 0.248 | 0.249 | 0.301 | 0.176 | 0.230 |

| p | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.135 | 0.002 | 0.137 | |

| VAS Activity Score | r | 0.676 | 0.657 | 0.277 | 0.378 | 0.133 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.169 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salgut, E.; Özkoçak, G.; Dinç Yavaş, A. Sensor-Based Assessment of Post-Stroke Shoulder Pain and Balance. Sensors 2025, 25, 7665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247665

Salgut E, Özkoçak G, Dinç Yavaş A. Sensor-Based Assessment of Post-Stroke Shoulder Pain and Balance. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247665

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalgut, Eda, Gökhan Özkoçak, and Arzu Dinç Yavaş. 2025. "Sensor-Based Assessment of Post-Stroke Shoulder Pain and Balance" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247665

APA StyleSalgut, E., Özkoçak, G., & Dinç Yavaş, A. (2025). Sensor-Based Assessment of Post-Stroke Shoulder Pain and Balance. Sensors, 25(24), 7665. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247665