1. Introduction

All things being equal, deeper or wider convolutional neural networks (CNNs) perform better than shallower or thinner networks [

1]. This statement encourages the research community to explore state-of-the-art deeper CNNs and utilize more channels. These deeper and wider networks improve performance on image classification and recognition, speech recognition, pattern recognition, prediction of gene mutations, natural language processing and sentiment analysis, and more [

2].

However, these networks tend to have higher computational costs. These costs increase linearly with network depth; for example, the 26, 35, 50, 101, and 152 layer residual networks require 41M, 58M, 83M, 149M, and 204M parameters, and 2.6G, 3.3G, 4.6G, 8.8G, and 13.1G FLOPs, respectively [

3,

4,

5]. Moreover, the costs of wider networks increase exponentially with the widening factor; for example, the 26-layer WRNs with widening factors 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 are trained with 41M, 163M, 653M, 1469M, 2612M, and 4082M parameters and 2.5G, 10G, 41G, 92G, 163G, and 255G FLOPs, respectively [

1,

6].

We introduce novel CNNs that achieve near state-of-the-art visual classification performance, or better, while using fewer parameters. We call this topic

parameter efficiency. One approach toward parameter efficiency is to broaden the types of weight sharing used in the network by introducing hypercomplex numbers. Another approach involves adjusting the architecture to use fewer parameters, such as axial or separable designs. For one example, weight sharing across space allows CNNs to drastically reduce trainable counts while improving image classification accuracy as compared to classical fully connected networks for visual classification and object detection tasks [

7,

8,

9,

10], image segmentation [

11,

12] and captioning [

13]. Standard CNNs exploit weight sharing across spatial feature maps (height and width) but do not share weights across channels.

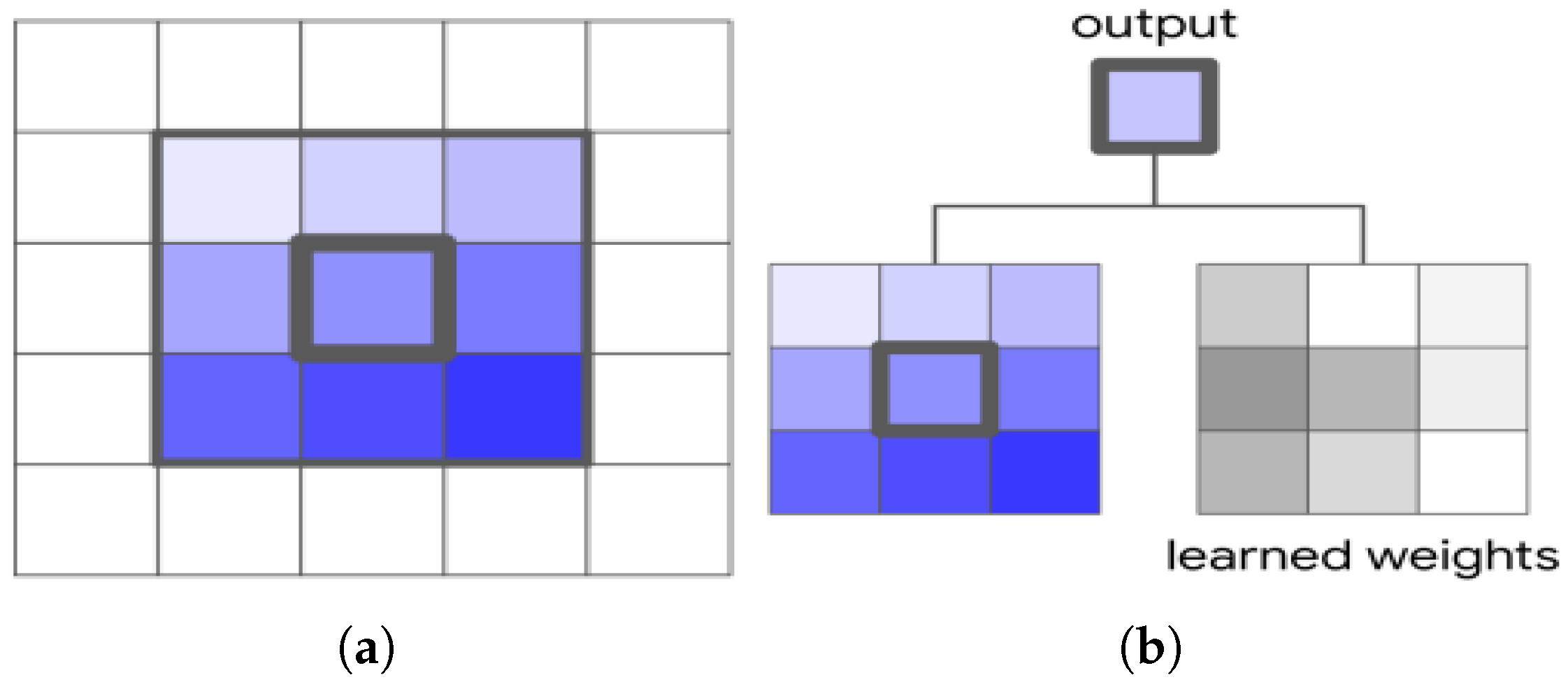

While developing hypercomplex CNNs (HCNNs), it was found that they share weights across channels as well as space [

4,

7]. This channel-based weight sharing can further reduce parameter requirements over standard CNNs. Their design is based on complex or hypercomplex number systems, usually with dimensions of two or four (but they can also be eight or sixteen dimensions using the octonion number system [

14] or sedenion number system, respectively). HCNN operations with different dimensions can be used for real-world applications using the complex number system (2D) [

15,

16], or the quaternion number system (4D) [

8,

9]. Also, it was found that the CNN calculations in an HCNN only use a subset of the number system. This removes the dimensionality constraint and allows the calculations to be replicated for any dimensions [

4,

17]. The success of all these HCNNs appears to be due to their cross-channel weight-sharing mechanism and consequent ability to treat data across feature maps coherently [

8,

9]. This space- and channel-based weight sharing reduces parameter costs significantly.

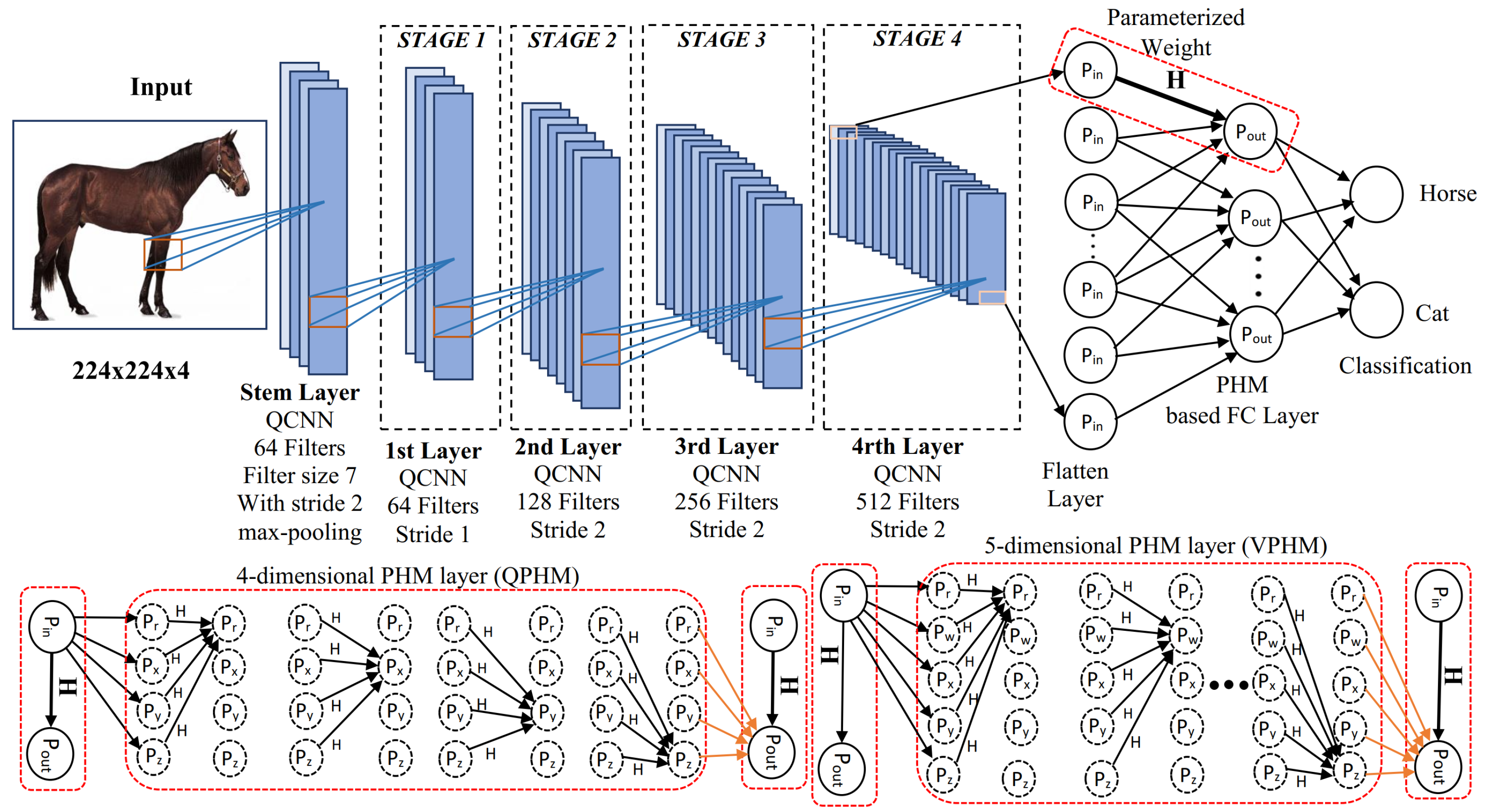

However, these early HCNNs did not use hypercomplex operations in all layers. Their fully connected backends were still real-valued. Full hypercomplex networks (FHNNs), introduced in [

5], include hypercomplex calculations in all layers, including the fully connected backend. These FHNNs reduce parameters moderately.

A separate concept, the axial concept was also used to reduce costs [

11,

18]. This concept splits the CNN operation into separate consecutive operations on the height and width input axes for vision tasks. These axial operations reduce costs

from

where

h and

w are the height and width of a 2D image. We review this axial concept for attention-based autoregressive models [

11,

18] and CNNs [

19].

Another CNN-based parameter-efficient concept has been introduced to split a

convolutional filter into two filters

and

[

12]. This separable CNN reduces cost from

to

. Also the channel reduction concept has been proposed to reduce parameters, although it also reduces the model’s performance [

10,

20,

21]. We review these concepts and trade-offs and compare them with the residual 1D convolutional networks (RCNs). The current paper analyzes separable FHNNs proposed by [

22] to analyze more parameter-efficient HCNNs.

This paper first reviews parameter efficiency for recent work and develops new CNN models in real-valued and hypercomplex space. It analyzes ways to reduce computational costs for CNNs in vision tasks. We review the parameter efficiency properties of HCNNs and then introduce several novel hypercomplex works that use weight sharing across channels and space. In modern deep CNNs, many convolutional layers are stacked, including the frontend (stem) layers, the backend layers, and the network blocks. This paper introduces and studies full hypercomplex networks (FHNNs) where hypercomplex dense layers are used in the backend of a hypercomplex network. It helps to reduce costs in the densely connected backend. This paper also studies attention-based CNNs, where feature maps generated by an HCNN layer are used in attention-based autoregressive models, and channel-based weight sharing is used. This channel-based weight sharing helps to reduce costs for attention-based networks, and the HCNN feature maps for the attention module help increase performance. The parameter efficiency for FHNNs can, however, be improved further. Separable HCNNs (SHNNs) have been introduced for vision classification [

22] to make CNNs more parameter efficient. SHNNs outperform the other HCNNs with lower costs (parameters, FLOPs, and latency).

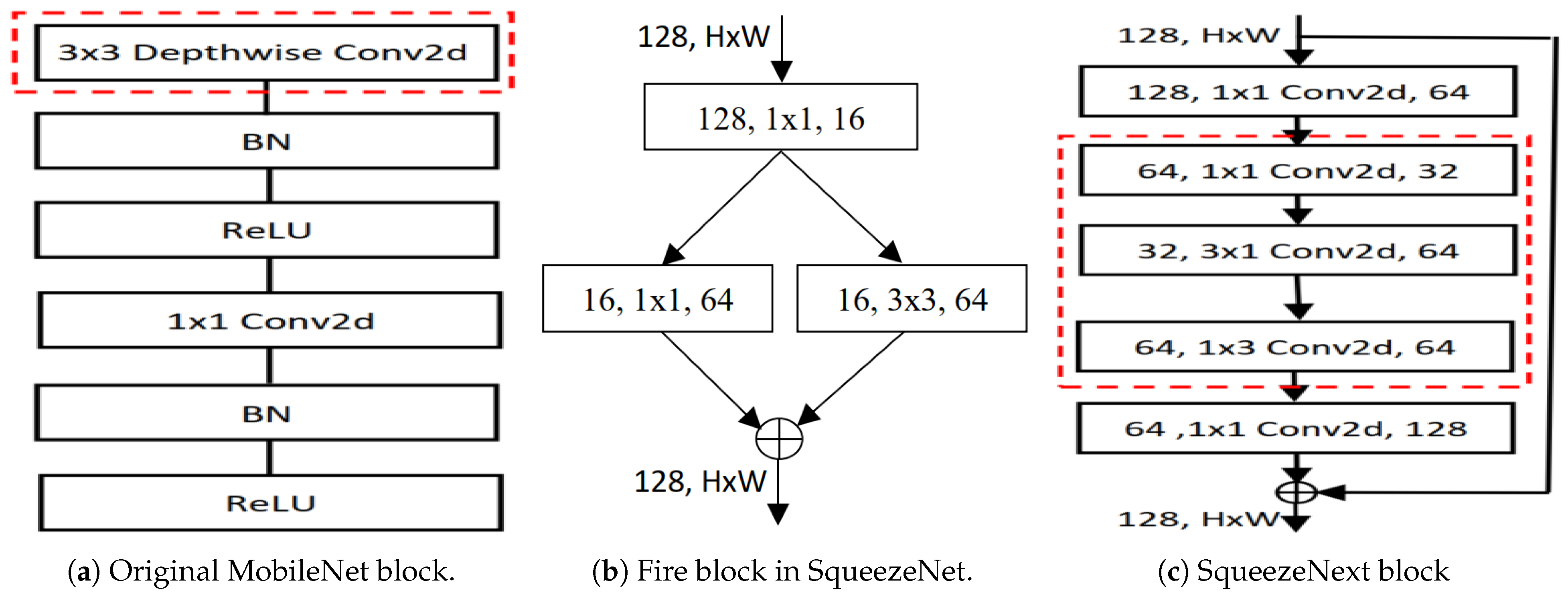

We then study parameter efficiency for real-valued CNNs. These CNNs extract local features and construct residual structures with identity mapping across layers [

3], MobileNets [

10,

21], SqueezeNets [

12,

20], and image super-resolution architectures [

23,

24,

25,

26]. As images are two-dimensional, these standard CNNs consume

computational costs (height

h, and width

w) per CNN layer. This paper analyzes a novel structure with 1D CNN (Conv1D) for vision to replace standard 2D CNN (Conv2D) and to reduce costs [

19]. The Conv1D consumes

compared to

of Conv2D. As two consecutive Conv1D are used instead of a Conv2D, a pair of layers costs

. A residual connection is used in each Conv1D layer dealing with gradient problems when training deep networks and improving the performance of network architectures [

19]. We also studied related work to compare it with this novel network. Our mathematical analysis shows the parameter efficiency, and empirical analysis shows that this novel real-valued CNN outperformed with fewer parameters, FLOPs, and latency.

2. Goals and Contributions

This paper analyzes the parameter efficiency of widely used CNN architectures, including hypercomplex CNNs, attention-based CNNs, and standard real-valued CNNs (for both computer and mobile settings), on visual classification tasks. This study offers valuable insights for designing cost-effective and parameter-efficient models. Prior hypercomplex CNNs leverage cross-channel weight sharing via the Hamiltonian product to reduce parameters, offering a strong foundation for efficiency [

2,

4,

9]. However, these models still use a conventional real-valued fully connected backend. We extend hypercomplex operations throughout the network (including the dense backend using a Parameterized Hypercomplex Multiplication layer) to construct a fully hypercomplex model. This design improves classification accuracy while reducing the parameter count and FLOPs compared to related networks, confirming the benefits of end-to-end hypercomplex modeling [

2]. Nevertheless, the reduction in parameters and computation from this step alone is modest. To significantly further improve efficiency, we introduce three novel architectures as outlined below.

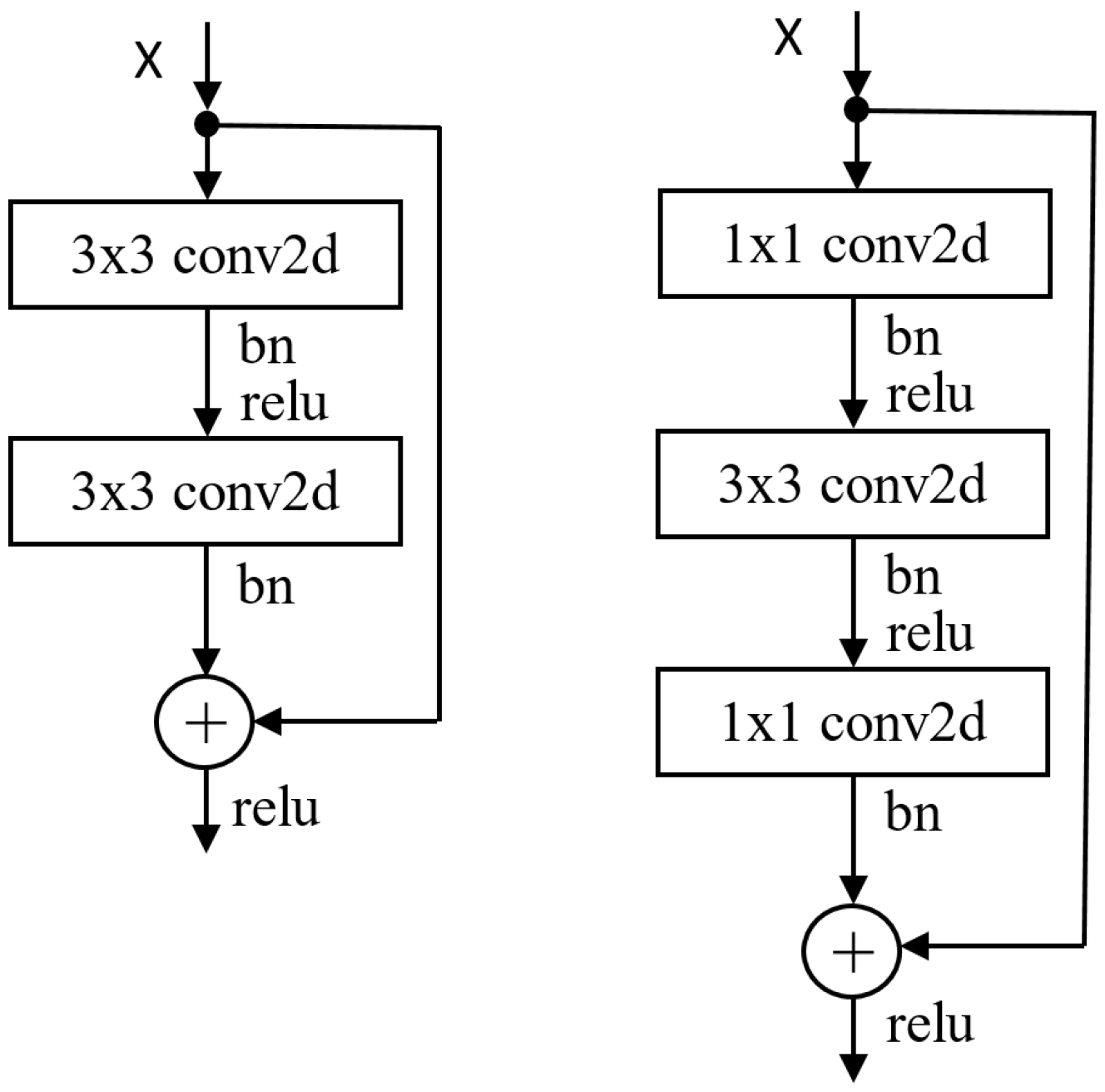

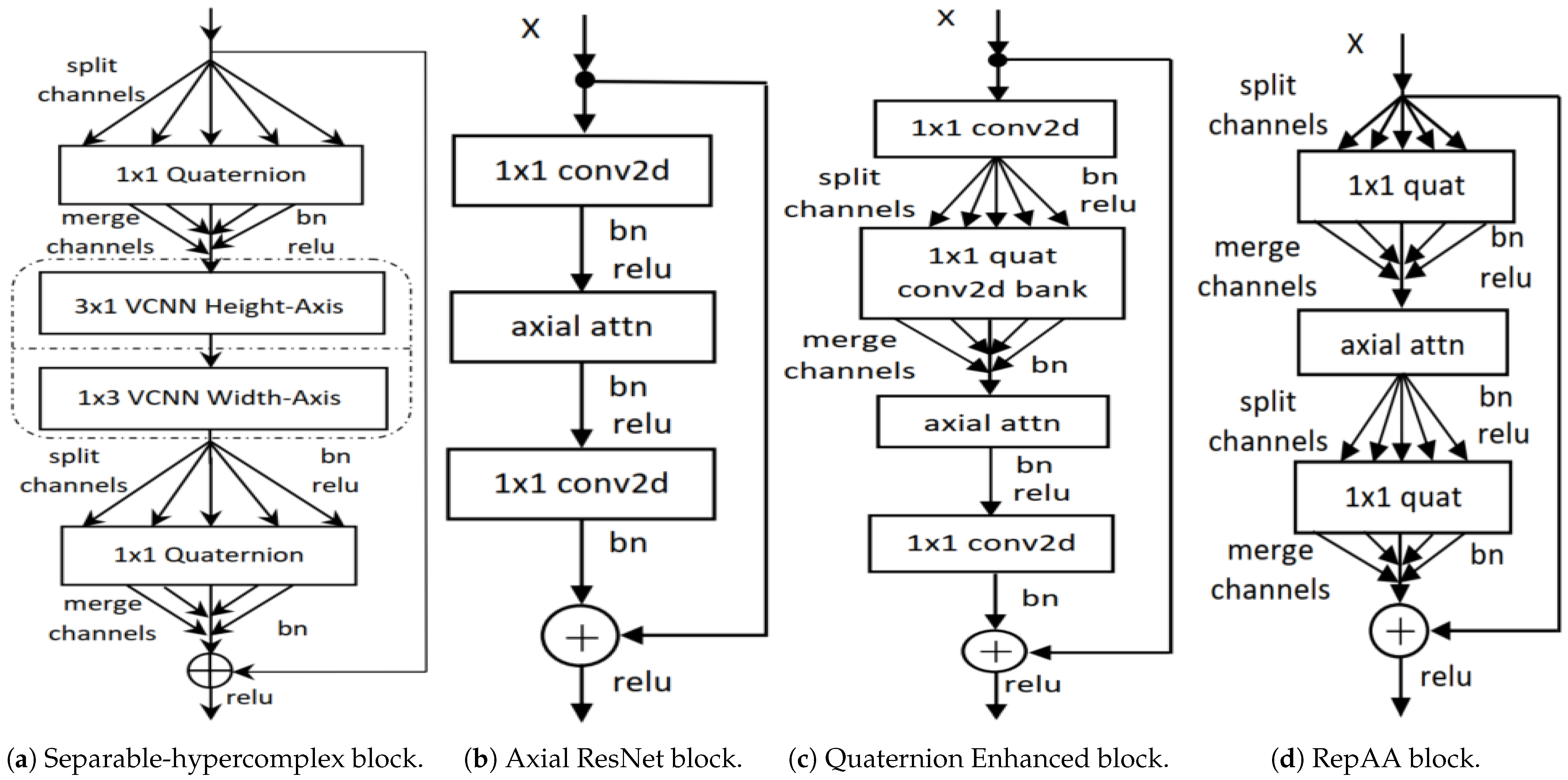

2.1. Separable Hypercomplex Neural Networks (SHNN)

We propose Separable Hypercomplex Neural Networks (SHNN) to achieve greater parameter reduction in hypercomplex CNNs. In a SHNN, each 2D quaternion convolution (QCNN) (e.g., a filter) is factorized into two sequential 1D convolutions ( followed by ) in the hypercomplex domain. Replacing a standard QCNN with two separable vectormap CNN layers yields a separable hypercomplex bottleneck block, which we stack to form the SHNN architecture. This separable design significantly reduces the number of parameters and FLOPs, while improving classification performance on CIFAR-10/100, SVHN, and Tiny ImageNet, compared to existing hypercomplex baselines. In fact, our SHNN models achieve state-of-the-art accuracy among hypercomplex networks. The only trade-off is a slight increase in latency. Overall, these results demonstrate that SHNN is a highly parameter-efficient hypercomplex CNN (HCNN) design.

2.2. Representational Axial Attention (RepAA) Networks

We introduce Representational Axial Attention (RepAA) networks to bring hypercomplex efficiency gains into attention-based models. Axial-attention CNNs are already more parameter efficient than full 2D attention models, yet they still rely on standard convolutional layers to compute attention weights. In our RepAA design, we incorporate HCNN layers with cross-channel weight sharing into the axial-attention architecture. Specifically, we replace key components of the axial-attention network (the early stem convolution, the axial attention blocks, and the final fully connected layer) with representationally coherent hypercomplex modules. The resulting RepAA network uses fewer parameters than the original axial-attention model while maintaining or improving classification accuracy. The result indicates that hypercomplex weight-sharing techniques can further reduce parameters in attention-based networks, making RepAA a promising approach for building more compact yet effective attention models.

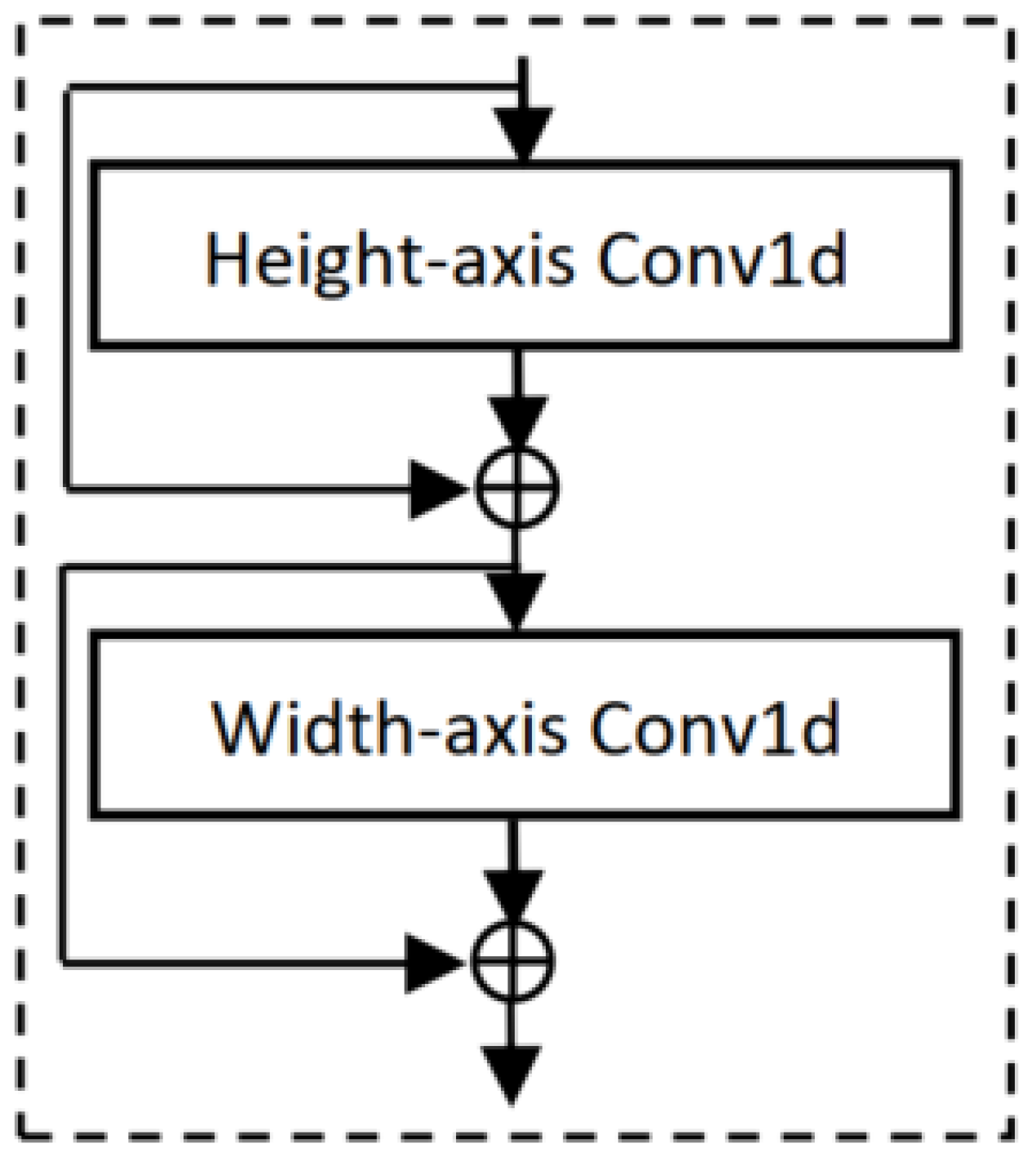

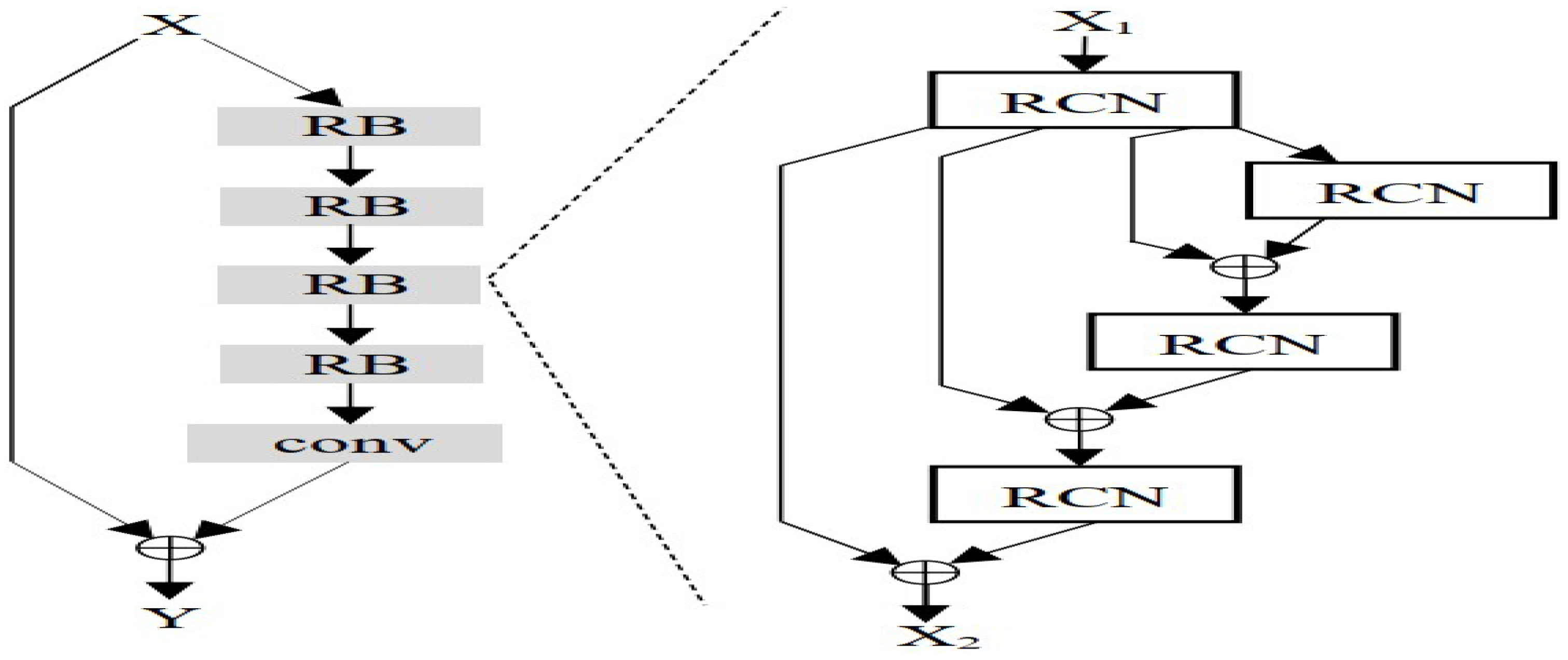

2.3. Residual 1D Convolutional Networks (RCNs)

To improve efficiency in real-valued CNNs, we propose Residual 1D Convolutional Networks (RCNs), which serve as direct substitutes for 2D CNNs in networks like ResNet. In an RCN block, a 2D spatial convolution is decomposed into two sequential 1D convolutions with an interleaved residual connection. We integrated RCN blocks into various ResNet architectures and found that RCN-based ResNets achieved better accuracy while using about 80% fewer parameters, 30% fewer FLOPs, and 35% lower inference latency. When we applied the RCN concept to other models, we observed significant reductions in computational cost with performance gains. These results confirm the effectiveness of the RCN architecture for creating lightweight, high-performing real-valued CNNs.

5. Performance Comparisons for Our Proposed Models

This section presents experimental results on three novel CNN types: hypercomplex CNNs (

Section 5.1), axial-attention-based CNNs (

Section 5.2), and real-valued CNNs in visual classification tasks (

Section 5.3). First, we compare the SHNNs with existing convolution-based hypercomplex networks, such as complex CNNs, QCNNs, octonion CNNs, and VCNNs. Then, we compare the representational axial attention networks with original axial-attention networks, QCNNs, and ResNets. Finally, we compare the residual conv1d networks with other related real-valued networks, such as original ResNets, wide ResNets, mobileNets, and squeezeNexts. All comparisons are performed on several image classification tasks. Our results primarily focus on parameter counts and performance.

5.1. Performance of Hypercomplex-Based Models

This section presents results that are related to HCNNs and are parameter efficient in hypercomplex space.

Table 1 shows the performance of different architectures along with the number of trainable parameters on CIFAR benchmarks (CIFAR10 and CIFAR100) [

41], SVHN [

42], and tiny ImageNet [

43] datasets. This table compares 26-, 35-, and 50-layer architectures of ResNets [

3], QCNN [

9], VCNN [

4], QPHM [

5], VPHM [

5], and SHNN [

22]. It also compares hypercomplex networks with full HCNNs, i.e., QPHM and VPHM, which stand for QCNNs with hypercomplex backend and VCNN with hypercomplex backend. Although the full HCNNs showed better performance in hypercomplex areas, they did not significantly reduce the parameter count and other computational costs.

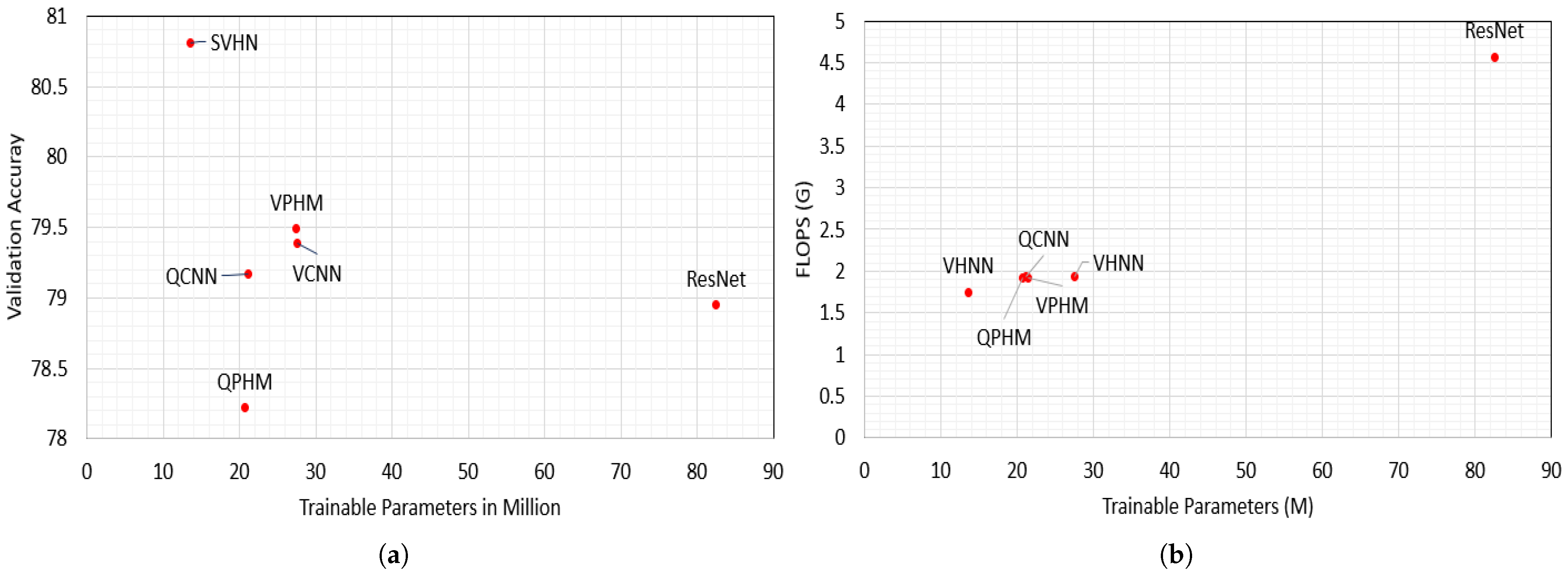

We compare our proposed SHNNs with full HCNNs and other HCNNs in regard to parameter count, FLOPS, latency, and validation accuracy results, shown in

Table 1. This table and

Figure 11a,b show that SHNNs outperform in validation accuracy with lower parameter count and FLOPs for all image classification datasets.

Figure 12a,b show the accuracy and loss curves for 50 layer ResNet, QCNN, QPHM and SHNN. We also compare the performance of SHNNs with other HCNNs where the SHNNs show state-of-the-art results for CIFAR benchmarks, shown in

Table 2.

For an input image with sizes height h, and width w, the HCNNs take resources for an image of length N where N is the flattened pixel set , and . The SHNN reduces these computational costs and is constructed in a parameter-efficient manner. To construct SHNNs, the spatial QCNN operation is replaced by two 3-channels VCNN layers. The 3-channel VCNN operation is first applied along the 1D input image region of length h and then applied along the 1D input image region of length w. These two 1D operations that are finally merged together reduce the cost to from the HCNNs cost of .

However, the SHNN latency is slightly higher than that of other HCNNs due to the transition from 4D HCNN to 3D HCNNs and 3D HCNNs to 4D HCNN [

22]. The latency for VCNNs is also high.

5.2. Performance of Axial Attention-Based Models

This section presents experimental results for attention-based parameter-efficient architectures in visual classification tasks. The comparisons involve hypercomplex axial-attention networks [

18] using ResNets [

3], QCNNs [

9], QPHM [

5], and axial-attention networks [

11], and are shown in

Table 3 for the ImageNet300k dataset.

Table 3 compares 26- layer (33-layer for QuatE-1 as QuatE-1 added an extra

quaternion CNN bank module), 35-layer, and 50-layer (66-layer for QuatE-1, as QuatE-1 added an extra

quaternion CNN bank module) architectures.

Although the layer count is increased for quaternion-enhanced (QuatE) axial-attention networks (26-layer becomes 33-layer networks, and 50-layer becomes 66-layers), the performance of the 35-layer networks does not improve enough to surpass the QuatE (33-layer) version. A similar situation happens for the 50-layer (66-layer for QuatE) version. The quaternion front end has more impact (the quaternion modules produce more usable interlinked representations) than the layer count [

18] but uses more parameters. To address this, we use a quaternion-based dense layer (QPHM) in the backend of QuatE axial attention networks [

18]. As explained in

Section 4.1.1, this reduces parameter counts slightly.

The most impressive results come from our novel axial-attention ResNets (RepAA) explained in

Section 4.2. We propose another quaternion-based axial attention ResNet named representational (because of improved feature map representations) axial-attention ResNets (RepAA) to reduce parameters significantly [

18].

The most important comparison is the RepAA networks with other attention-based ResNets (QuatE axial-ResNet and axial-ResNet). It directly shows the effect of applying representational effects throughout the attention network. In all architectures, excluding 35 layers where our first proposed architecture (QuatE-1) perform better, the RepAA networks outperform in classification accuracy with far fewer parameters. This solves the problem encountered in QuatE-1 networks (discussed in the previous paragraph) and supports our analysis of parameter-efficient attention models, as our proposed RepAA network architectures consumes fewer parameters than the other relevant network architectures, shown in

Table 3.

5.3. Performance of Real-Valued CNNs

This section presents results on parameter-efficient real-valued computer and mobile-embedded CNNs (explained in

Section 4.3), and parameter-efficient convolutional vision transformers. We compare ResNets and RCNs of

and 152-layer residual CNN architectures. We also compare MobileNet with parameter-efficient RCMobileNet, and SqueezeNext (23 layers with widening factors 1 and 2) with parameter-efficient RCSqueezeNext architectures.

We start by showing comparisons between ResNets and RCNs in

Table 4. The experiments use the CIFAR benchmarks [

41], Street View House Number (SVHN) [

42], and Tiny ImageNet [

43] image classification datasets. We compare a range of shallow and deep architectures consisting of

, and 152 layers. Our comparison for this part of the paper is in terms of parameter count, FLOPS count, latency, and validation accuracy on the four datasets.

Table 4 describes that the

and 152-layer RCN architectures reduce by

,

,

,

, and

trainable parameters, respectively, and 15 to 36 percent fewer FLOPS in comparison to real-valued convolutional ResNets. We propose parameter-efficient RCNs that improve the validation performance significantly for all network architectures mentioned in

Table 4 than the original ResNets for all datasets [

19]. We demonstrate the layer-wise performance improvement as “the deeper, the better” in classification. The parameter-efficient RCN-based ResNets consume

,

,

,

, and

fewer latency than the original ResNets for

and 152-layer architectures, respectively. These costs state the parameter-efficient computer-based networks.

We present results examining the widening factors for residual networks [

19] in

Table 5. For a fair comparison with WRNs [

1], we use 26-layer RCNs with widening factors

and 10 to 28-layer WRNs. WRCNs outperform the original WRNs for all widening factors shown in

Table 5. Shahadat and Maida [

19] show that our 26-layer proposed WRCNs consume 86% fewer parameters than the original WRN [

1] and demonstrate “the wider, the better”.

We also analyze mobile-embedded architectures with our parameter-efficient RCN blocks (see

Figure 9) [

19]. We apply our RCN concept in MobileNet and SqueezeNext architectures to propose RCMobileNet and RCSqueezeNext architectures. As seen in

Table 4, the RCMobileNet achieves more than validation accuracy on CIFAR10 with 75% fewer trainable parameters and almost

fewer FLOPs than the original MobileNet architecture. Our RCMobileNet has a similar latency to the original MobileNet.

Table 4 compares the performance for 23-layer SqueezeNext architectures with widening factors 1 and 2. Our RCSqueezeNexts consume 34%, 24%, and 33% fewer parameters, FLOPs, and latency, respectively, and show better validation performance than the original SqueezeNexts [

19].

We also apply our proposed RCN modules to the CMT and DRRN architectures and proposed parameter-efficient RCMT and RCRN for image classification and image super-resolution datasets. The performance comparisons of CMT architectures are in

Table 4 for CIFAR benchmarks and SVHN datasets. We compare the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) results of our parameter-efficient proposed RCRN with different networks on image super-resolution dataset [

19]. We compare DRRN and RCRN, as they directly indicate the effectiveness of parameter-efficient RCN blocks. For fair comparison, we construct RCRN19 (

) and RCRN125 (

) to compare with the original DRRN19 (

) and DRRN125 (

), respectively [

19]. Our comparisons are shown in

Table 6 on the Set5 dataset and for all scaling factors. Also, our parameter-efficient proposed RCRN19 takes 18182 parameters compared to the 297,216 parameters of DRRN19.

5.4. Basis for Selecting the 1D Convolution Kernel Size in RCNs

Residual one-dimensional convolutional networks (RCNs) replace the spatial 2D convolutional layer with two sequential 1D depthwise separable convolution (DSC) operations, each using a kernel of size. Because the receptive field of each 1D convolution is controlled entirely by

k, the choice of the kernel size is central to the representational capacity and efficiency of the RCN block, defined in Equation (

30). The effective receptive field of each RCN block is therefore determined by the depthwise kernel size

k applied independently along the height and width axes.

5.4.1. Rationale Behind Kernel Size Selection

The kernel size

k is selected to preserve the spatial modeling capability of standard 2D convolution while significantly reducing computational cost. A conventional 2D convolution with a kernel of size

incurs a computational cost, shown in Equation (

2), whereas a single 1D depthwise convolution in an RCN has linear complexity, shown in Equation (

31). Because the RCN block applies two such 1D operations, its total cost becomes

resulting in a substantial reduction in complexity relative to standard 2D convolution. Consequently,

k is chosen to ensure sufficient spatial coverage, analogous to 3 × 3 or 5 × 5 filters in 2D convolution, while maintaining the linear computational growth that characterizes the 1D formulation.

5.4.2. Parameter and Computational Cost Implications

The cost reduction ratio between a 2D convolution and the RCN block is expressed as demonstrating that RCNs reduce computation by a factor proportional to . Because RCN complexity grows linearly with k, in contrast to the quadratic growth of 2D convolution, larger kernel sizes can be used without incurring prohibitive parameter or FLOP increases. This property is particularly advantageous for mobile and embedded applications, where computational budgets are limited.

5.4.3. Summary of Selecting the 1D Convolution Kernel Size in RCNs

The selection of the 1D convolution kernel size in RCNs is guided by the need to preserve spatial representational power while exploiting the linear-cost benefits of 1D depthwise separable convolution. Larger kernel sizes improve accuracy by expanding the receptive field, while RCN linear scaling ensures that computational costs remain manageable. This design principle enables RCN-based architectures to deliver strong classification performance with significantly reduced parameter counts, FLOPs, and latency compared with standard 2D convolutional networks.

5.5. Ablation Study on 1D Convolution Kernel Size in RCN-Based Architectures

This section presents an ablation analysis that evaluates the impact of the size of the 1D convolution kernel k on classification accuracy and parameter efficiency in two architectures: RCMobileNet and RCSqueezeNext. Since RCNs replace each spatial 2D convolution with two sequential 1D depthwise separable convolutions, the kernel size directly determines the effective 1D receptive field and plays a fundamental role in controlling both accuracy and model complexity.

The results indicate that increasing k consistently improves accuracy on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 up to a saturation point. The linear dependence of parameter count on k allows larger kernels to be used without significantly increasing model size, in contrast to the quadratic scaling found in 2D convolutions.

5.5.1. Kernel-Size Effect in RCMobileNet

Table 7 evaluates the effect of varying

k in RCMobileNet. Moderate kernel enlargement (up to

) improves accuracy with minimal increases in parameter count, demonstrating that the RCN substitution for MobileNet’s depthwise convolution remains highly efficient.

5.5.2. Kernel-Size Effect in RCSqueezeNext

Table 8 presents the ablation results for RCSqueezeNext. As with other architectures, kernel sizes up to

produce consistent accuracy gains, while larger kernel sizes yield diminishing returns.

Overall, across all two architectures, kernel sizes in the range of to offer the best balance between accuracy and efficiency for CIFAR-scale data.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This paper analyzed the parameter efficiency of many widely used models, including hypercomplex CNNs, attention-based CNNs, and real-valued computer and mobile-embedded CNNs on vision classification tasks. This information is essential for those interested in implementations of parameter-efficient models.

The cross-channel weight-sharing concept used in hypercomplex filters, along with the Hamiltonian product, helps to implement parameter-efficient hypercomplex convolutional networks. Also, this weight-sharing property of HCNNs allows building models as cost-effective architectures, which is a perfect fit for three- or four-dimensional input features. Although traditional HCNNs form a good foundation for parameter-efficient implementations [

4,

9,

15], our efficiency can be improved as all models use the real-valued backend in their architectures. We applied hypercomplex properties throughout the network, including the backend dense layer, to construct a full hypercomplex-based model. They applied the PHM-based dense layer in the backend of hypercomplex networks, which helped to imply hypercomplex concepts throughout the network. This novel design improved classification accuracy, and reduced parameter counts, and FLOPs more than the other related networks. The results [

5] support our analysis that the PHM operation in the densely connected backend implements parameter-efficient HCNNs, but it did not reduce parameters and FLOPs significantly.

To further reduce parameter counts, we proposed separable HCNNs by splitting the 2D convolutional () filter into two separable filters with size of and . To apply separable filters, we replaced the quaternion operation in the quaternion CNN block using two separable vectormap convolutional networks and formed the SHNN block. This separable hypercomplex bottleneck block improves classification performance on the CIFAR benchmarks, SVHN, and Tiny ImageNet datasets compared to the baseline models. These SHNNs also show state-of-the-art performance in hypercomplex areas and reduce parameter counts and FLOPS significantly. But they have longer latency than real-valued and hypercomplex-valued CNNs. The reason behind this higher latency is the model performs convolution twice and takes transition time from 2D convolution to two consecutive 1D convolutions. The parameter and FLOP reduction support our analysis that the SHNNs are parameter-efficient HCNNs.

Although axial-attention networks are parameter-efficient attention-based networks, they still use convolution-based spatial weight sharing. We applied cross-channel weight sharing along with spatial weight sharing to the attention-based models. They applied representationally coherent modules generated by HCNNs in the stem, the bottleneck blocks, and the fully connected backend [

18]. These results are important because the improvement was observed when the hypercomplex network was applied for the axial attention block. This suggests that this technique may be useful in reducing parameters and making parameter-efficient attention-based networks.

We also reviewed real-valued models like residual networks, vision transformers, and mobile-supported MobileNet and SqueezeNext architectures. Our comparison is limited to classification-based vision models. We compared the RCN block, constructed with two sequential 1D DSCs and residual connections, with original ResNets for different layer architectures. These modifications helped to reduce by around the number of trainable parameters, around FLOPs, and around latency, as well as improving validation performance on image classification tasks. This cost reduction supports our hypothesis that the RCN is a parameter-efficient architecture.

We also checked our proposed RCN block for ResNets, WRNs, MobileNet, and SqueezeNext architectures, which showed that the RCNs-based ResNets, WRCNs, MobileNet, and SqueezeNext take fewer parameters, FLOPs, and latency and obtain better validation accuracy on different image classification tasks. We also applied our proposed method to DRRNs that improve PSNR results on image super-resolution datasets and reduce around trainable parameters compared to the other CNN-based super-resolution models. These suggest that the RCN block helps construct parameter-efficient real-valued computer, mobile, and vision transformer embedded networks for vision tasks.

Future research can extend the proposed parameter-efficient CNN architectures in several meaningful directions. First, while this study focused on image classification tasks, applying SHNN, RepAA, and RCN models to other domains such as object detection, semantic segmentation, or even few-shot learning could test their adaptability and generality. Second, integrating additional compression techniques such as quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation with the current architectures may further reduce model size and computational requirements. Evaluating the performance of these networks on real-world edge devices like mobile GPUs or microcontrollers would validate their practicality, particularly given the RCN design for embedded systems. It would also be valuable to test the cross-domain robustness of these models by applying them to fields like medical imaging or satellite image analysis. Finally, future work could explore the integration of lightweight and hypercomplex CNN components into transformer-based or multimodal vision architectures, opening paths for more efficient vision–language models. These directions build on the core principle of structural efficiency and weight sharing demonstrated in SHNN, RepAA, and RCN, aiming to broaden their impact across both tasks and platforms.