1. Introduction

Compared to RGB cameras where there are only three values per pixel [

1], hyperspectral and multispectral cameras record more detailed spectral signatures from a scene. The additional information in a multi- or hyperspectral capture has been shown to be important in applications ranging from medical imaging [

2,

3], remote sensing [

4,

5], food processing [

6,

7,

8] and art conservation [

9,

10]. However, the higher price tag, lower spatial resolution, longer integration time and/or bulkiness of spectral imagers limits their practical use.

There are many algorithms exploiting statistical regression and machine learning that attempt to recover high-quality spectral images from (or with the help of) the RGB images. In spectral reconstruction (SR), hyperspectral images are recovered directly from their RGB image counterparts. Here, a ground-truth dataset of paired hyperspectral and RGB data is used to train the SR method. Example approaches include regression (pixel-based one-to-one mapping) [

11,

12,

13,

14] and deep learning-based algorithms (patch-by-patch mapping) [

15,

16,

17].

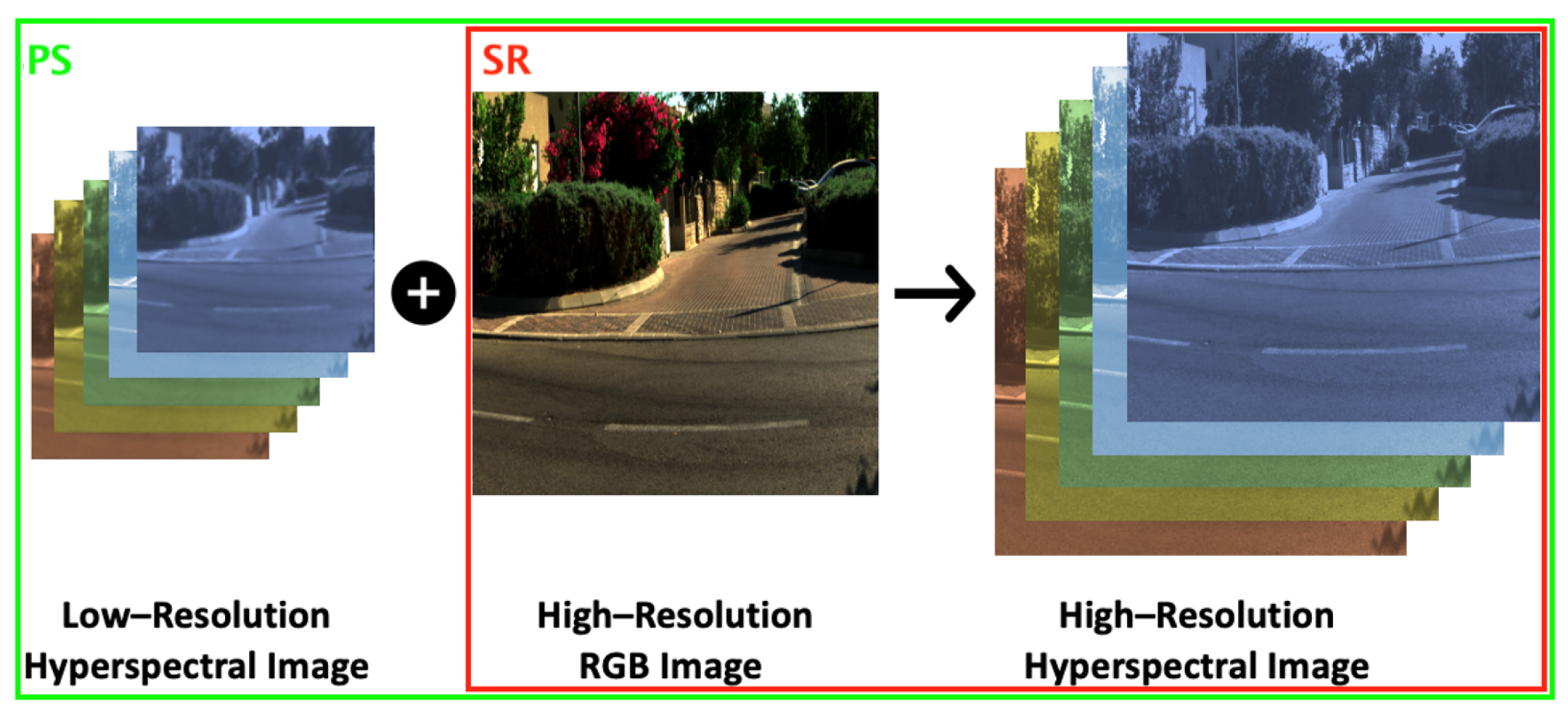

In RGB pan-sharpening (PS), a low-resolution hyperspectral or multispectral image is upsampled to full resolution using a full-resolution RGB image as a guide. The term “sharpened” comes from the fact that if we naively upsampled the images (e.g., using bilinear upsampling), the spectral image would appear blurred relative to the RGB counterpart. When pan-sharpening works well, it looks like the low-resolution spectral image has been sharpened.

There are two variants of RGB-guided pan-sharpening. When we upsample a low-resolution hyperspectral image (where finely sampled spectra are measured at every pixel), we call it

hyperspectral pan-sharpening. Often, however, the image we wish to upsample is still a multichannel image but with more channels than a 3-channel RGB image. In this case, we call this

multispectral pan-sharpening. While the image data is different, the algorithms themselves can often be applied to both the hyper- and multispectral capture scenarios, e.g., [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Together, SR and PS are examples of RGB-guided spectral recovery algorithms.

Unlike most recent works in spectral recovery, in this paper, we take a step back and ask a fundamental question: “Given a recorded RGB response and assuming the camera sensitivities are known, are there fundamental properties that any recovered spectrum must adhere to?” In 1953, Wyszescki [

22] first described that each radiance spectrum is composed of a fundamental component intrinsic to its RGB tristimulus response (later called the “fundamental metamer”) and its “metameric black”. The fundamental metamer integrates to the same given RGB and the black component integrates to zero RGB, [0, 0, 0] (which is where “black” comes from).

Given an RGB of a spectrum and the device spectral sensitivities, we can find the

actual fundamental metamer defined to be the spectrum in the span of the spectral sensitivities of the camera sensors that projects to the given RGB. Then, we call the projection of a given estimated spectrum (estimated by an SR or PS algorithm) onto the same 3-dimensional spectral subspace spanned by the spectral sensitivities the

estimated fundamental metamer. We are being careful in our definitions here as, generally, a spectral recovery algorithm—even though the actual RGB is known—will recover a spectrum where the estimated fundamental metamer is not equal to the actual fundamental metamer. One consequence of this result is that when the estimated spectrum, from a given input RGB, is numerically integrated with the camera sensitivities, the calculated output RGB will not be the same as the input [

23,

24]. This also means that the estimated spectrum, for most prior-art algorithms, must be the wrong answer.

As we further apply Matrix-R theory to the application of spectral recovery, we learn that a given RGB suggests its corresponding spectrum must have a unique fundamental metamer but can have different metameric blacks. This said, we would argue that the problem of spectral recovery should be about recovering the metameric black because for a given RGB, the fundamental metamer is uniquely prescribed by the, assumed known, spectral sensitivities of the camera. Yet, curiously, the vast majority of algorithms, e.g., [

15,

21,

24,

25,

26,

27], formulate spectral recovery as minimizing a figure of merit (e.g., RMSE) for a given dataset. And, in so doing, the individual recovered spectra can have the wrong estimated fundamental metamers. In a couple of recent works the idea that spectral reconstruction should focus on recovering the metameric black has been investigated with promising results [

23,

28,

29]. In this paper, we show how, instead of re-architecting and retraining already deployed algorithms, we can always improve them via a simple post-processing step, as presented in

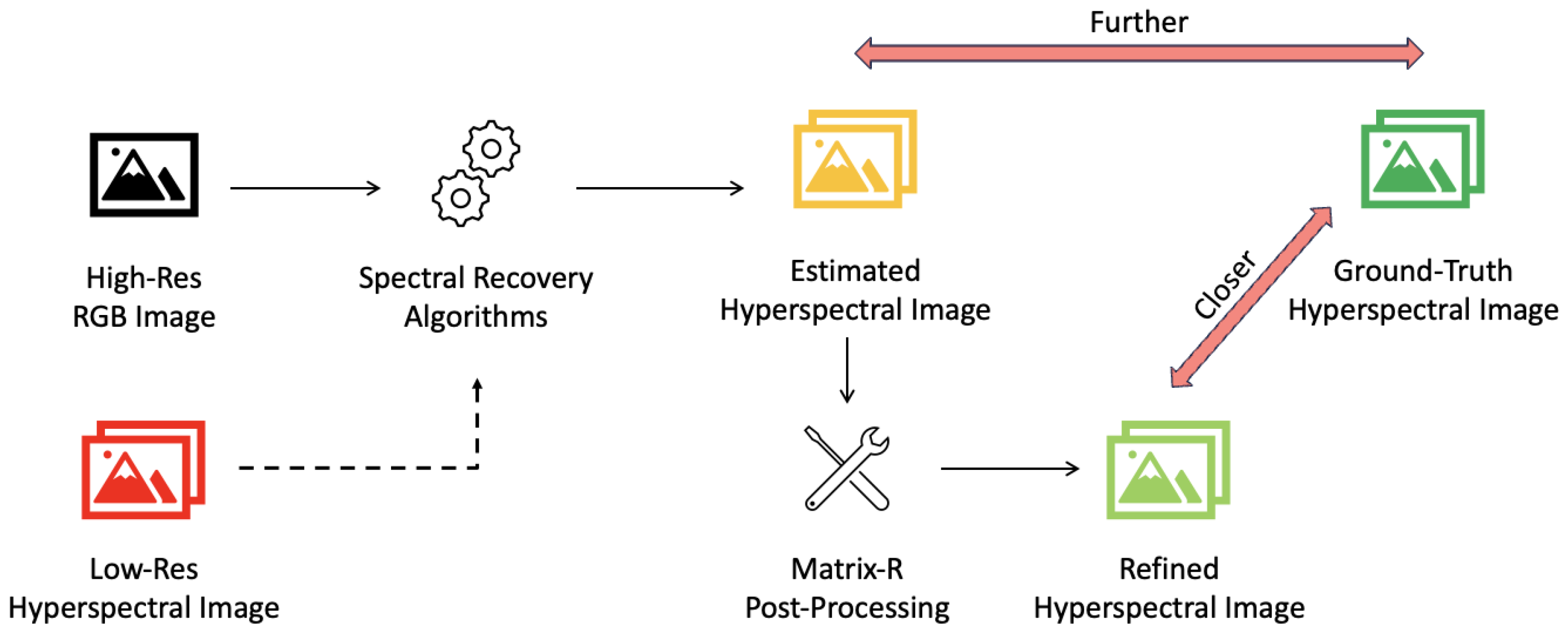

Figure 1. Here, the output of the existing spectral recovery algorithms is refined by the Matrix-R post-processing step, bringing it closer to the ground-truth hyperspectral images. Low-resolution hyperspectral images are indicated with a dashed arrow, as they are only used by the pan-sharpening algorithms; otherwise, if high-resolution RGB images alone are used, it is referred to as spectral reconstruction.

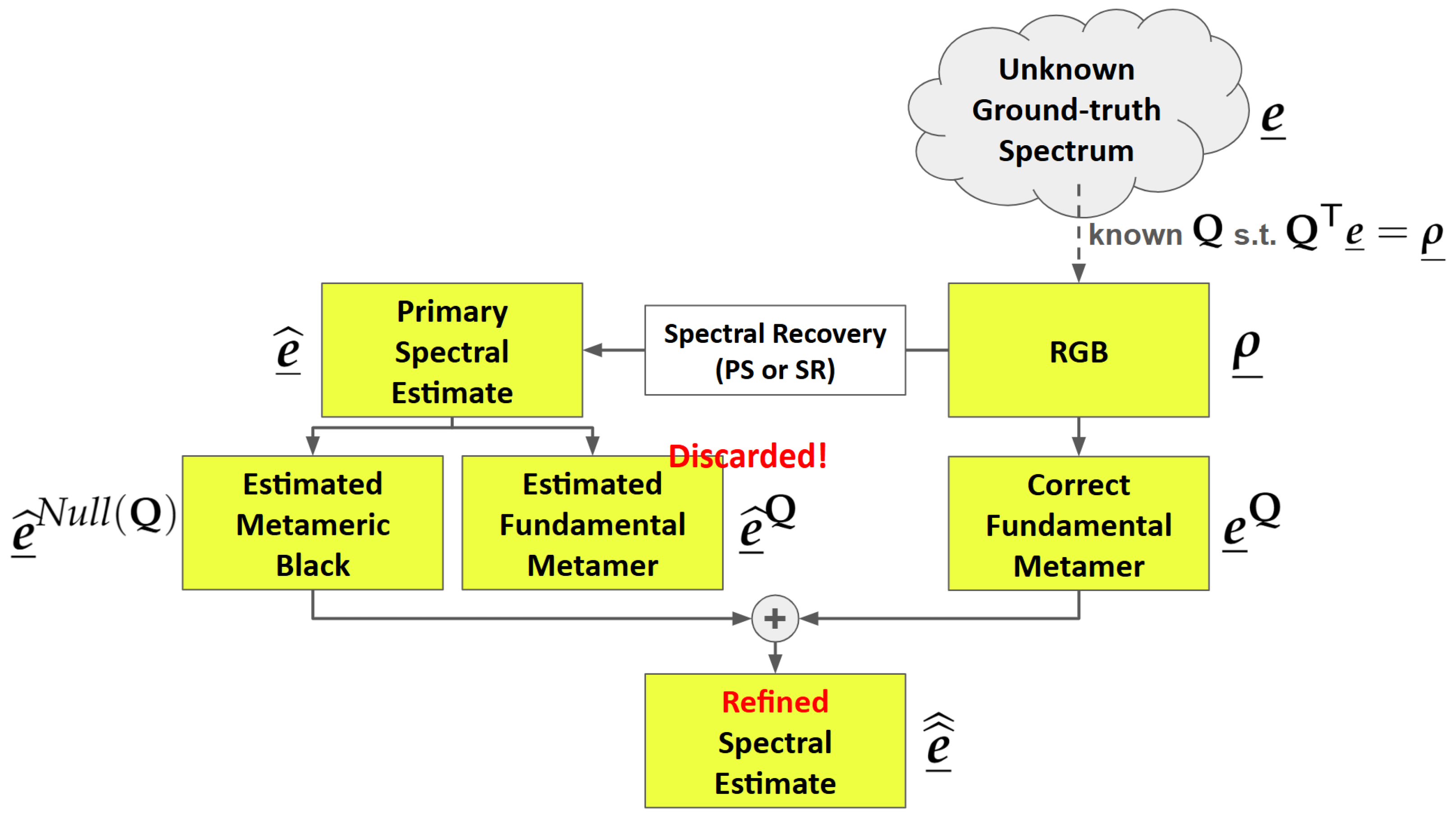

In more technical terms,

Figure 2 illustrates how our post-processing method is deployed. First, we denote the targeted (but unknown) ground-truth spectrum as

, which forms an RGB

through the camera system

. Here,

is an

n-dimensional vector corresponding to the measurements made across a range of

n sample wavelengths. A spectral reconstruction or pan-sharpening algorithm returns a primary estimation of the spectrum, denoted as

. In our method,

is uniquely decomposed into estimated fundamental metamer and metameric black components, respectively denoted

and

. The notation

Q indicates that the decomposition is done with respect to the camera system

, and the metameric black component lies in the null space [

30] of

.

Then, though the ground-truth

is unknown, given the observed RGB

and the camera system

, we can still derive its fundamental metamer,

[

31]. Finally, the refined spectral estimate is calculated as

. A key result of this paper is to prove that the refined estimate must be at least as close to the actual ground-truth than the primary estimate made by the SR or PS algorithms and it is, empirically, often much closer. This post-processing is generic and can be applied to all algorithms, using classical or deep learning approaches, reported in the literature.

We call our method “Matrix-R post-processing” because the algorithm illustrated in

Figure 2 depends on a particular projector matrix

[

22,

31] and the post-processing can be described in terms of simple matrix multiplications in terms of

. The operation of matrix

is summarized in the next section, and our post-processing algorithm and a proof of its efficacy are presented in

Section 3.

We go on to develop the underlying theory when additional constraints are known about the spectra in a scene. Specifically, it is well known that spectral reflectances are smooth and are well described by low-dimensional linear models (of around 6 to 8 [

32,

33]). Concomitantly, the spectra, in a scene illuminated by a single dominant light, will have the same dimension as the reflectances (though they will span a different subspace as light spectra are often not smooth). We show how we extend our method to incorporate this linear basis constraint into the Matrix-R theory.

We empirically test our post-processing algorithm on several spectral reconstruction and spectral pan-sharpening algorithms. In all cases we improve the recovery error. When the spectra in a scene belong to a low-dimensional linear basis, our post-processing algorithm delivers an even larger reduction in the recovery error.

We also consider the case where we attempt not to recover full spectra but rather a multispectral representation (i.e., the multispectral pan-sharpening), where given an RGB guide and an m channel low-dimensional measurement of the scene (where ), we seek to recover the full-res m-channel multispectral image. We show how our developed theory can also be applied in this case and include a final small experimental section as a proof of concept.

This paper makes three key contributions:

While most studies in the field of spectral recovery are dedicated to presenting new models to solve the problem, the methods in this paper are designed to improve all existing and future methods.

Our approach is fundamental in nature—the guaranteed improvement of performance by our methods is grounded in mathematical proofs rather than empirical research.

The methods are developed as a post-processing process, which means no change or retraining needs to be done to apply to a given algorithm, including the off-the-shelves black-box solutions. We also note that our proposed methods are simple; that is, it does not incur excessive processing.

6. Discussion

Our proposed post-processing Matrix-R method can be applied in a wide context: the proposed process could be used to enhance the performance of off-the-shelves “black-box” algorithms where the algorithm source code is not available. Indeed, our theorems do not require the knowledge of the algorithm itself. We need only the input RGB and camera sensitivity information for the Matrix-R decomposition. Theorem 1 also gives the user comfort. It does no evil: it will always either improve the performance of any algorithm or, failing that, it will not reduce the algorithm’s performance.

As for Theorem 2, in our experiment, we were not given a known lower-dimensional basis that will definitely represent all spectra in each scene. This means that the interchangeability of

and

in Equation (

20) may not hold, i.e.,

can create color error, and subsequently, error in calculating the ground-truth fundamental metamer

from the RGB input

. Of course, we may sensibly assume that as the assumed spectral dimension

m increases (i.e., when

m approaching

n, the original spectral dimension), we get more accurate low-dimensional model that represents spectra. And yet, according to our results, this cannot be the only factor that affects the optimal selection of

m. The determination of the optimal basis dimension

m is heavily dependent on the fidelity of the initial spectral estimate. We observed that high-performing deep learning models, such as AWAN and MIAE, typically achieve peak performance with higher-dimensional subspaces. This is likely because these models successfully recover subtle spectral nuances; applying a restrictive, low-dimensional

m in these cases would discard valid spectral information, effectively acting as a form of over-regularisation. Conversely, simpler methods like bilinear interpolation often produce coarse spectral estimates with significant deviations from the ground-truth. For these algorithms, using a lower

m is advantageous as it enforces a stricter prior, constraining the noisy estimates to a fundamental subspace of natural spectra and thereby filtering out gross spectral errors. Consequently, we recommend determining

m empirically to match the specific capacity of the chosen reconstruction algorithm.

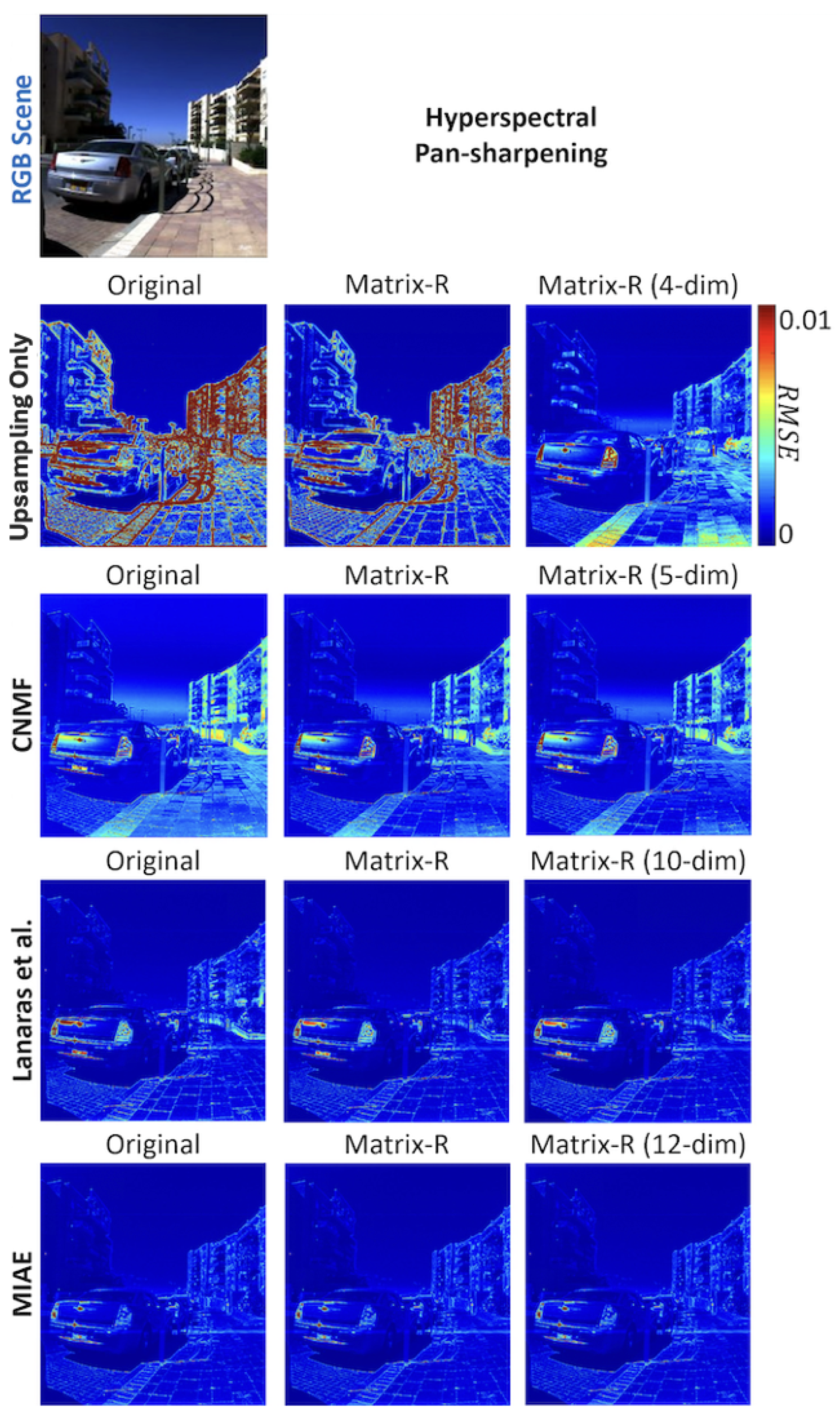

Another observation on optimal

m is that, for some algorithms, the optimal

m is different for mean and worst-case (99-percentile) results, and the latter generally suggests a smaller optimal

m. This is understandable as a lower-dimensional linear model has the effect of bounding the outliers from exceeding what the underlying assumed basis can explain. Conversely, some originally more accurate pixels could be overgeneralized by the basis and lose accuracy. We can observe both effects in the “Upsampling Only” result in

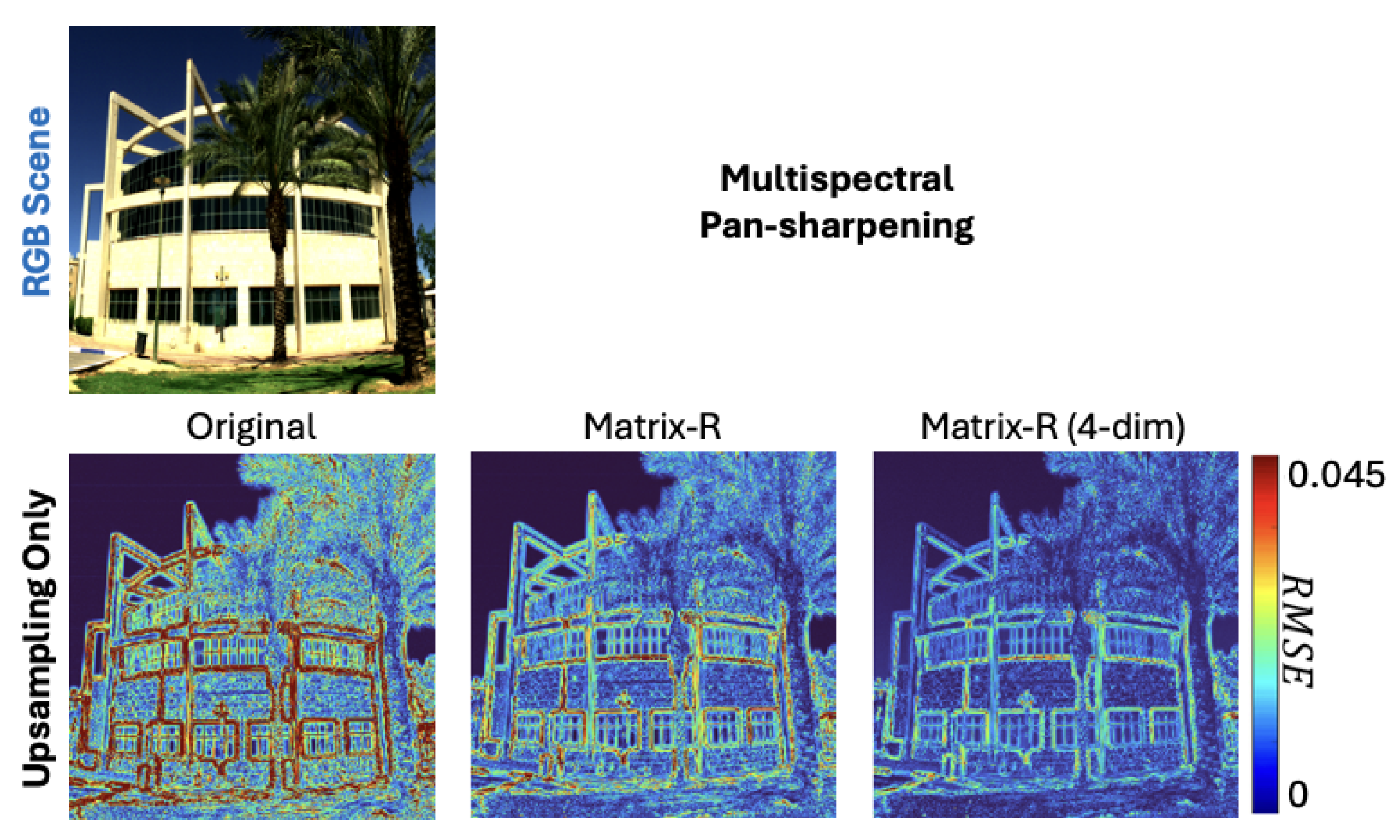

Figure 4. Here, in the subplot labeled “Matrix-R (4-dim)”, we see that a 4-dimensional spectral representation make the boundaries of buildings and the sky much more accurate, while loses accuracy in areas around the sidewalk.

We also observed that the magnitude of improvement from Matrix-R post-processing is inversely related to the baseline algorithm’s accuracy. Unlike “physically blind” algorithms, advanced models such as AWAN and MIAE explicitly incorporate the camera’s spectral sensitivity functions, resulting in spectral estimates with highly accurate fundamental metamers. Thus, our method offers the most significant value to algorithms that are not explicitly constrained by sensor physics.

Looking ahead, we recognize that employing real images from different cameras could present additional challenges [

49,

63], including image registration and varying exposure levels [

24,

39]. While our aim in this study was to propose a theoretical solution through simulation as a preliminary step, future research may explore these methods using actual camera setups.

7. Conclusions

The Matrix-R theorem teaches that, given the RGB observation and the spectral sensitivity functions of the sensors, we can certainly calculate the fundamental metamer component of the ground-truth spectrum, leaving the residual metameric black component to be uncertain. On the other hand, hyperspectral pan-sharpening algorithms seek to super-resolve low-spatial-resolution hyperspectral images given their high-spatial-resolution RGB counterparts, and spectral reconstruction (SR) algorithms recover hyperspectral images directly from the RGBs. Yet, most of these algorithms do not guarantee the exact reproduction of the fundamental metamers.

In this paper, we showed how the Matrix-R method can be used to always improve the performance of pan-sharpening and spectral recovery: we simply make sure that it has the correct fundamental metamer. And, we provide mathematical proof that this improvement will always happen. Furthermore, we developed the Matrix-R method where spectra are represented by a low-dimensional linear model.

Experiments on several historic and state-of-the-art PS and SR algorithms show that our proposed post-processing Matrix-R method always improved these algorithms. In addition, the low-dimensional linear basis variant of our theorem was shown to yield the best recovery results. Finally, our exploration of multispectral pan-sharpening reaffirms the efficacy of the Matrix-R method and its lower-dimensional variant.