Influence of Lens Systematic Errors on Autocollimator Angle Measurement: Theoretical and Experimental Explanations

Highlights

- Among the various aberrations of a collimator objective, only coma at various orders affects the accuracy of an autocollimator.

- The angle errors introduced by assembly deviation are a systematic shift. This shift is independent of the field of view and is determined solely by the aberrations and the decentration of the collimator objective. It can be expressed in terms of the Sensitivity of Assembly Deviation (SAD) coefficient.

- The coma-dominant influence can be used to correct the aberrations of a collimator objective during the design step.

- The Sensitivity of Assembly Deviation coefficient can be utilized to guide the positional and attitudinal adjustments of the collimator objective during the adjustment step.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Laser source. Li et al. proposed an algorithm for suppressing the influence of an imperfect Gaussian light source, especially for long working distances. They successfully reduced the errors caused by unbalanced light distribution to one-sixth [5]. Zhu et al. established a ray-tracing model based on the Gaussian formula, which could be used for analyzing the influence of an imperfect dotted light source [6]. The model above treats the lens as an ideal lens without any aberration.

- Diaphragm. Li et al. found that reducing the roughness of the diaphragm could result in improvements in measurement uncertainties [7]. Yu et al. used a diaphragm of array silts to average the influence of the manufacturing errors from each silt [8]. Fuetterer studied the effect of coherence on the imaging effect of slit diaphragms [9]. Lovchy et al. investigated the vignetting features of different slits and proposed a slit-selecting method for different areas of measuring range [10,11]. However, the use of the Diaphragm has also brought about new problems. When multiple slits are used, there will be cases where the object points deviate from the optical axis. The influence of aberrations on autocollimation angle measurement will be more complex.

- Target mirror. The expanded-size beam could reduce the impact of mirror defects on reflected light by the average effect. Dagne et al. designed a mini-autocollimator with an extra beam expander [12]. The systematic errors by the 8 mm beam were reduced to 11.274 arcsec, compared to 22.099 arcsec errors by the 2 mm beam. Eves and Leroux proposed an approach to find the direction of the normal vector of a real mirror with an imperfect surface, which is also proven to be effective in reducing errors [13]. Hiraku Matsukuma et al. investigated autocollimators with rough surfaces [14]. They revealed that the systematic errors induced by the rough surface could be suppressed by selecting a specific wavelength.

- The above research provides effective methods to reduce the impact of mirrors. However, it does not take into account the influence of an imperfect lens. When the impact of the mirror is coupled with the aberration of the lens, the influence on angle measurement becomes more complex.

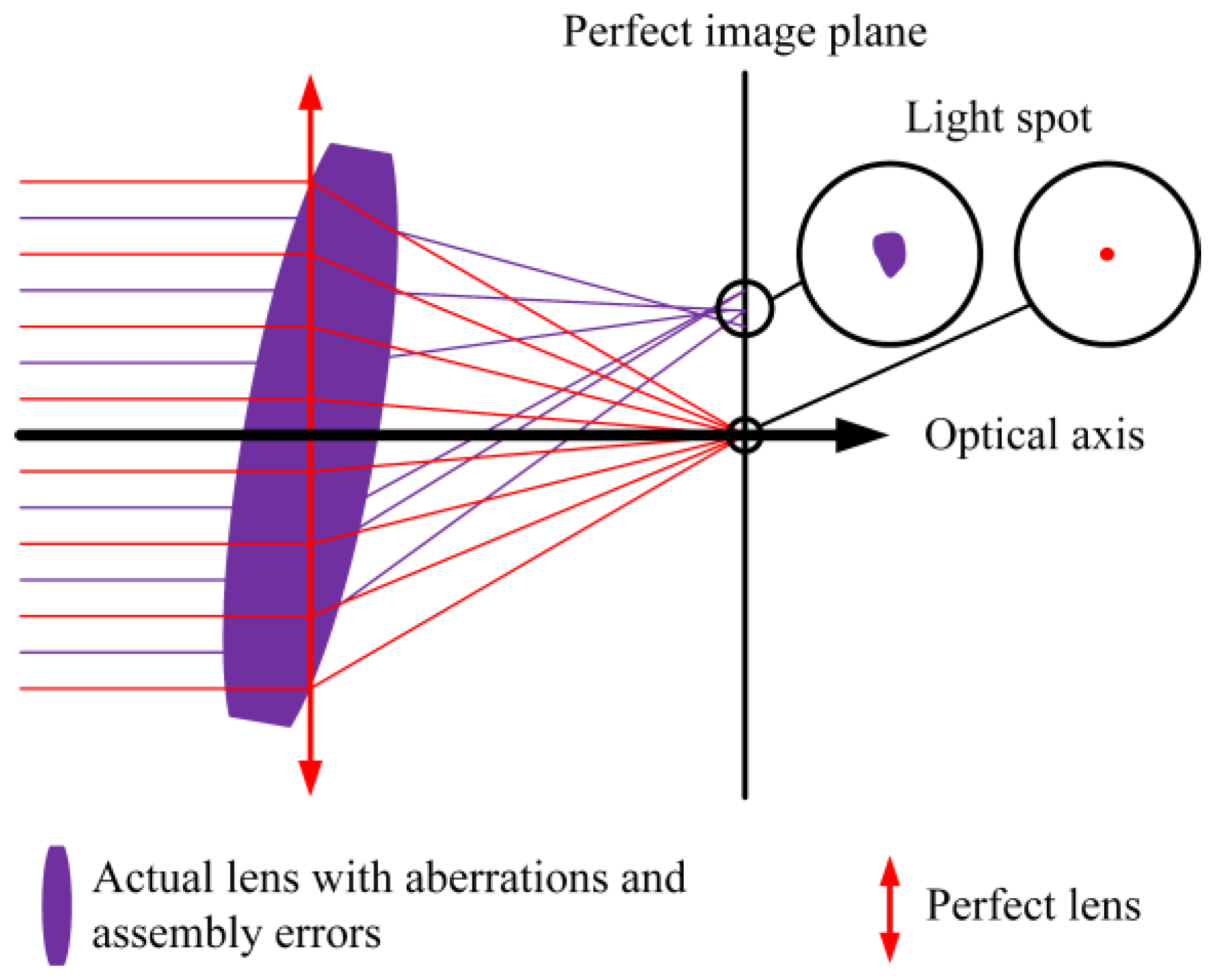

- Especially, the collimator objective is attributed to the quality of the collimated beam, which has received special attention from researchers. As Figure 1 shows, the assembly deviation will not deteriorate the image quality of a perfect lens without aberration. However, an actual lens with aberrations will produce an irregularly shaped spot, with a deviated centroid. The assembly deviation will further affect the shape of the light spot and the position of the centroid. Therefore, aberrations and assembly deviation are two coupled systematic errors of a collimator objective.

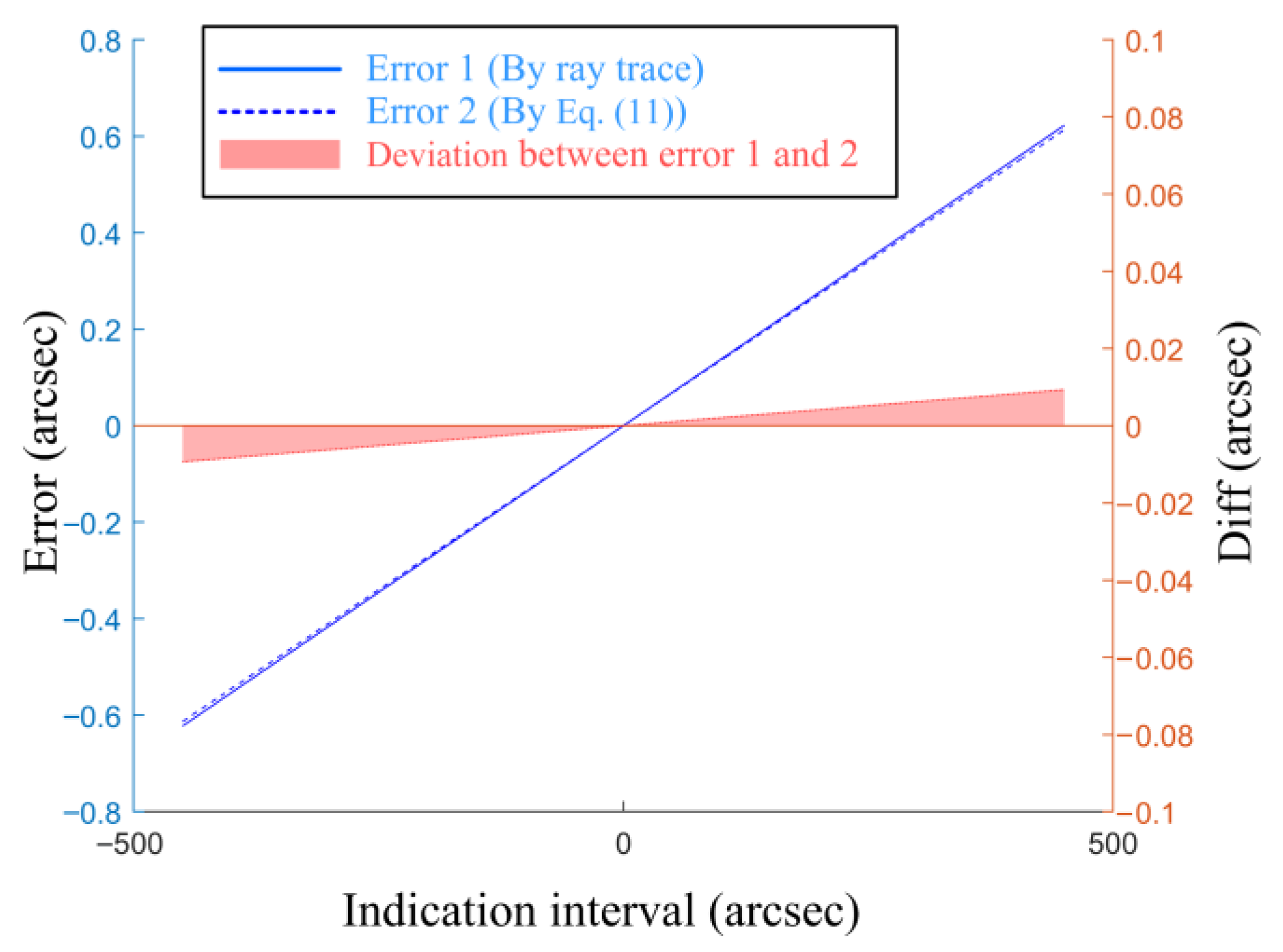

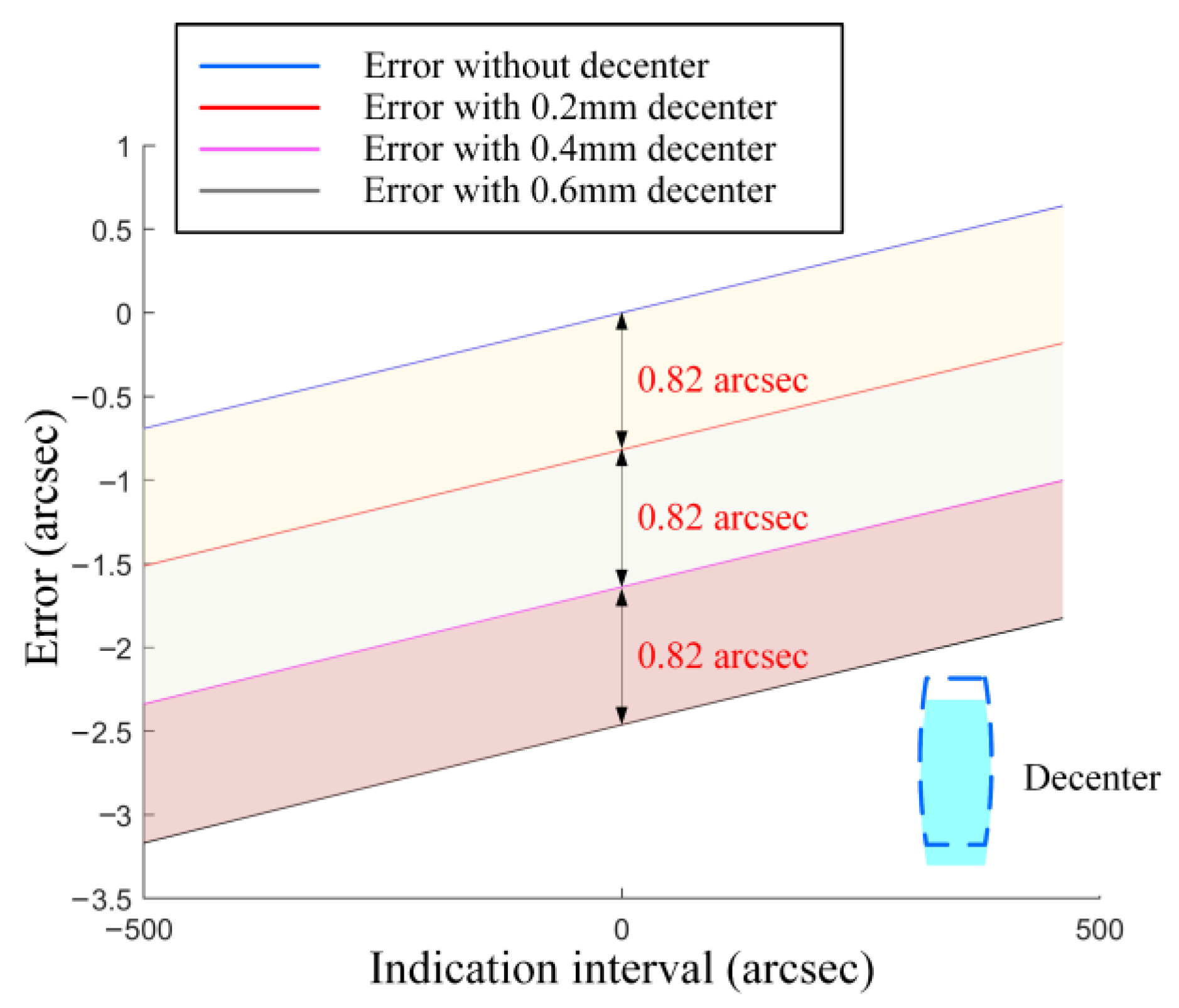

- Collimator objective. Shimizu et al. analyzed the influence on sensitivity caused by spherical aberration of the collimator objective and achieved a high resolution of 1 milli-arcsec [15]. Shi et al. investigated the assembly deviation of the lens by ray tracing. The experiment result shows that a lens offset of 20 μm resulted in a 13.09 arcsec increase in the optical aberration within a measuring range of 1000 arcsec [16]. The above research did not establish an explicit relationship between aberration and angle measurement error.

2. Principle and Simulation

2.1. Coordinate System Definition

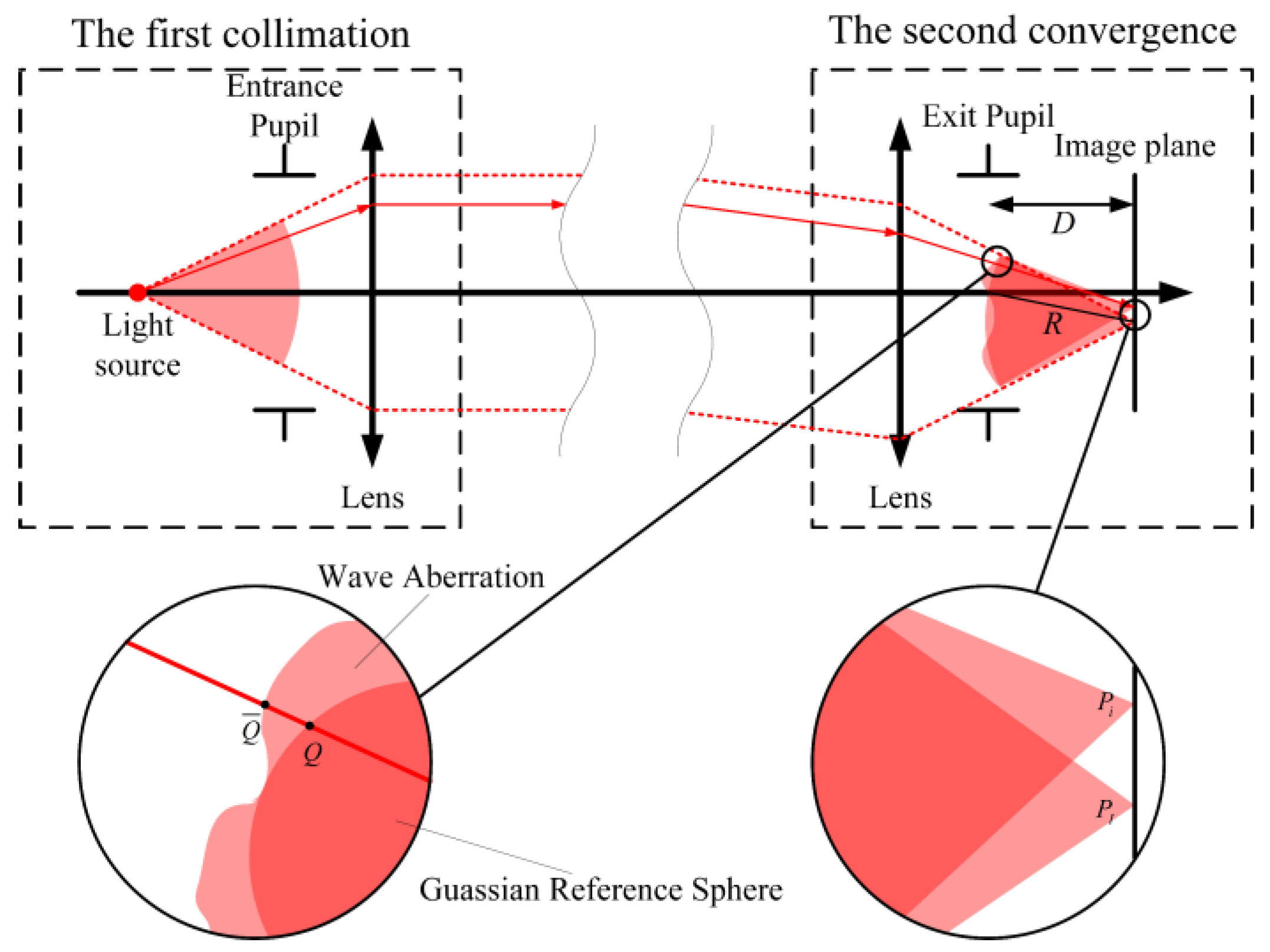

2.2. Mechanism of the Aberrations on Autocollimation Angle Measurement

2.2.1. Principle

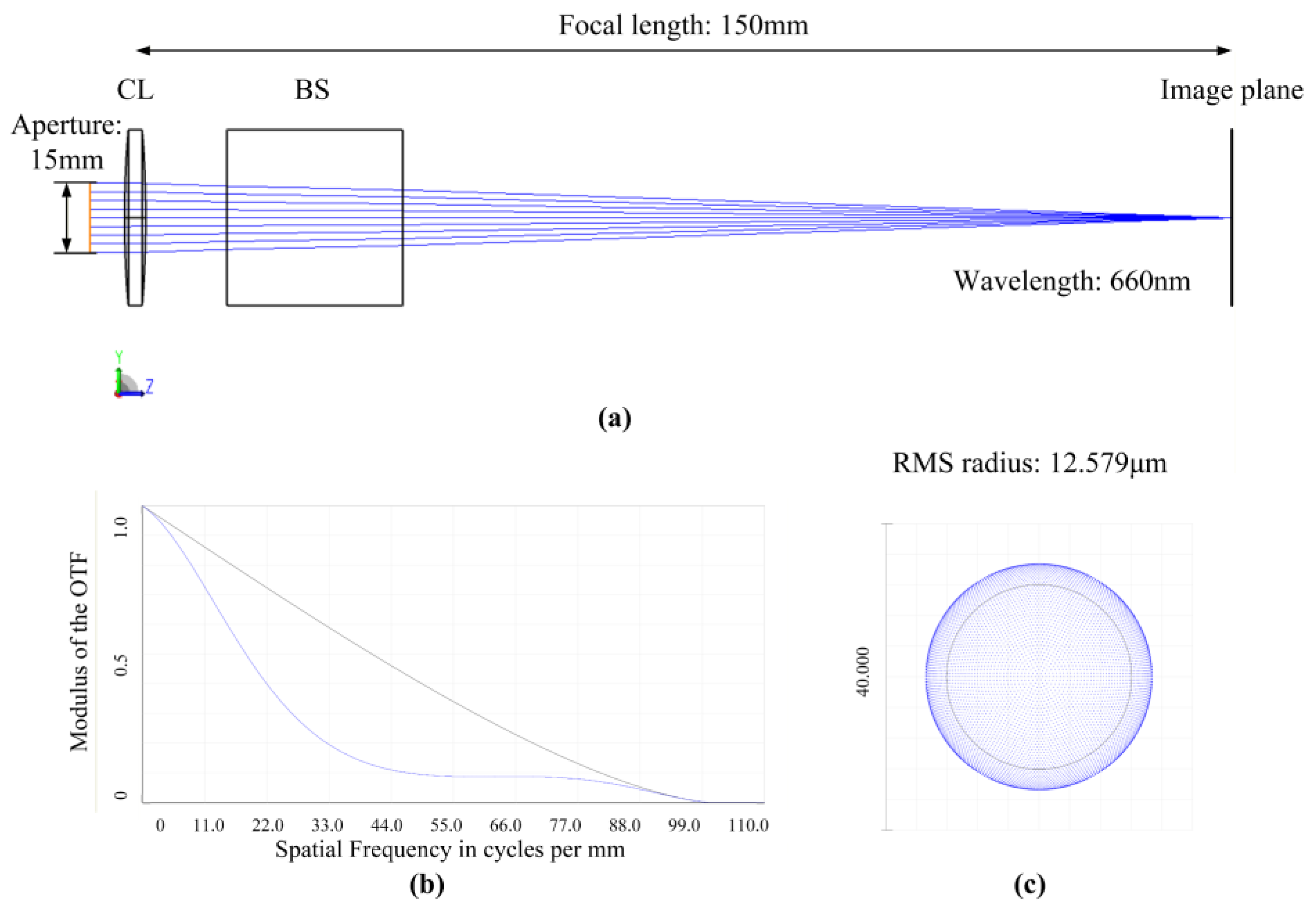

2.2.2. Simulation

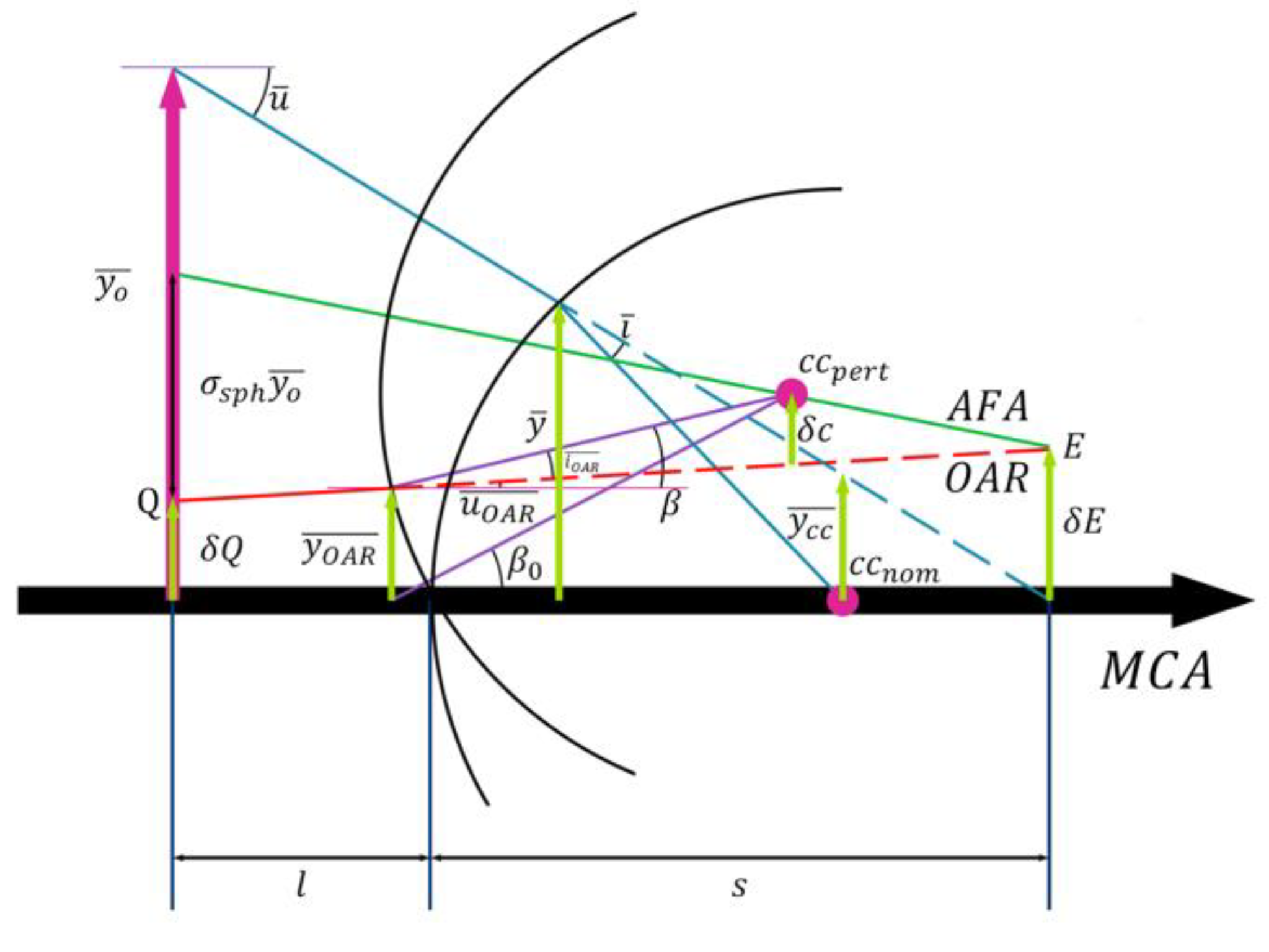

2.3. Mechanism of Assembly Deviation on Autocollimation Measurement

2.3.1. Principle

2.3.2. Simulation

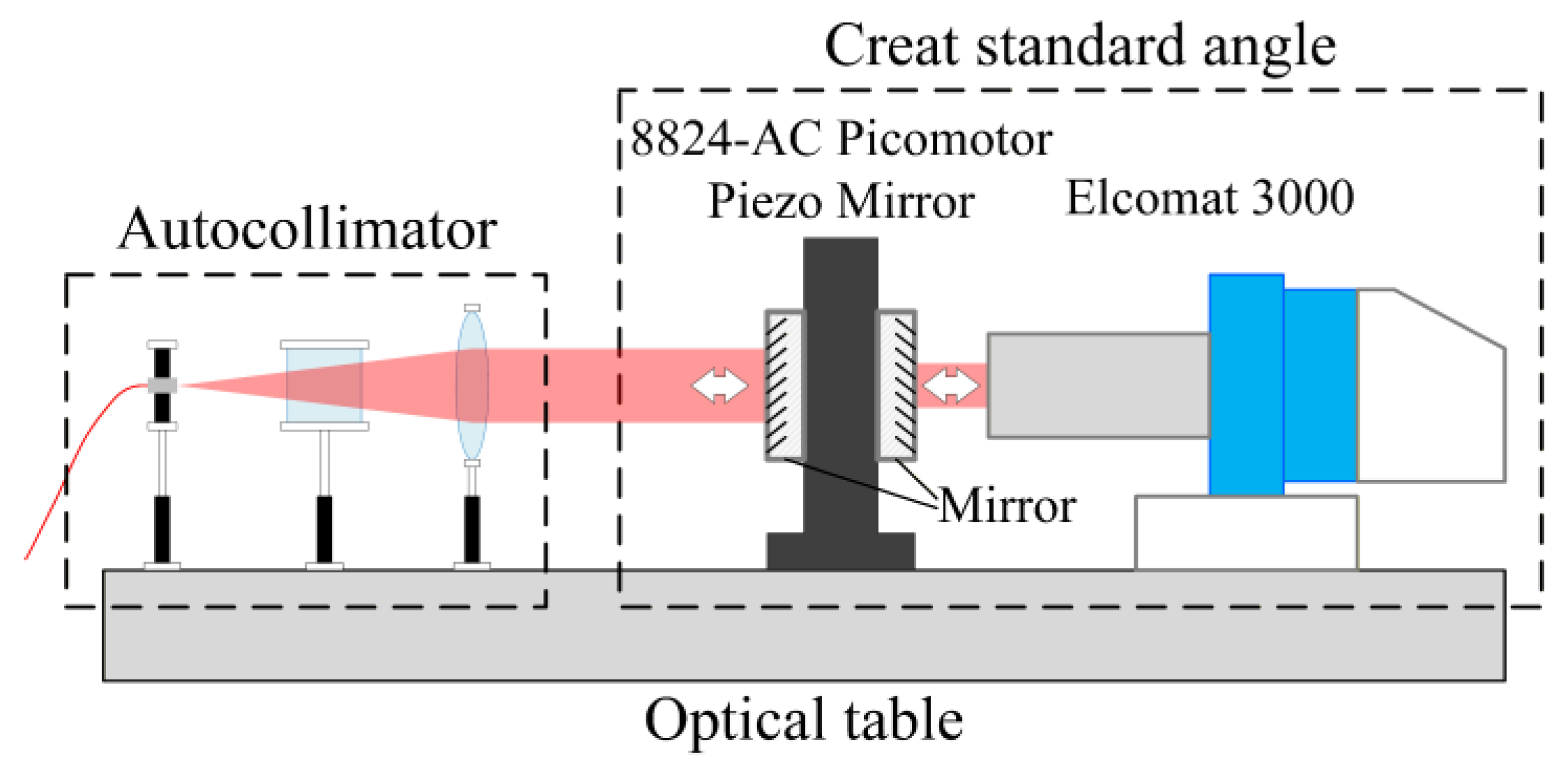

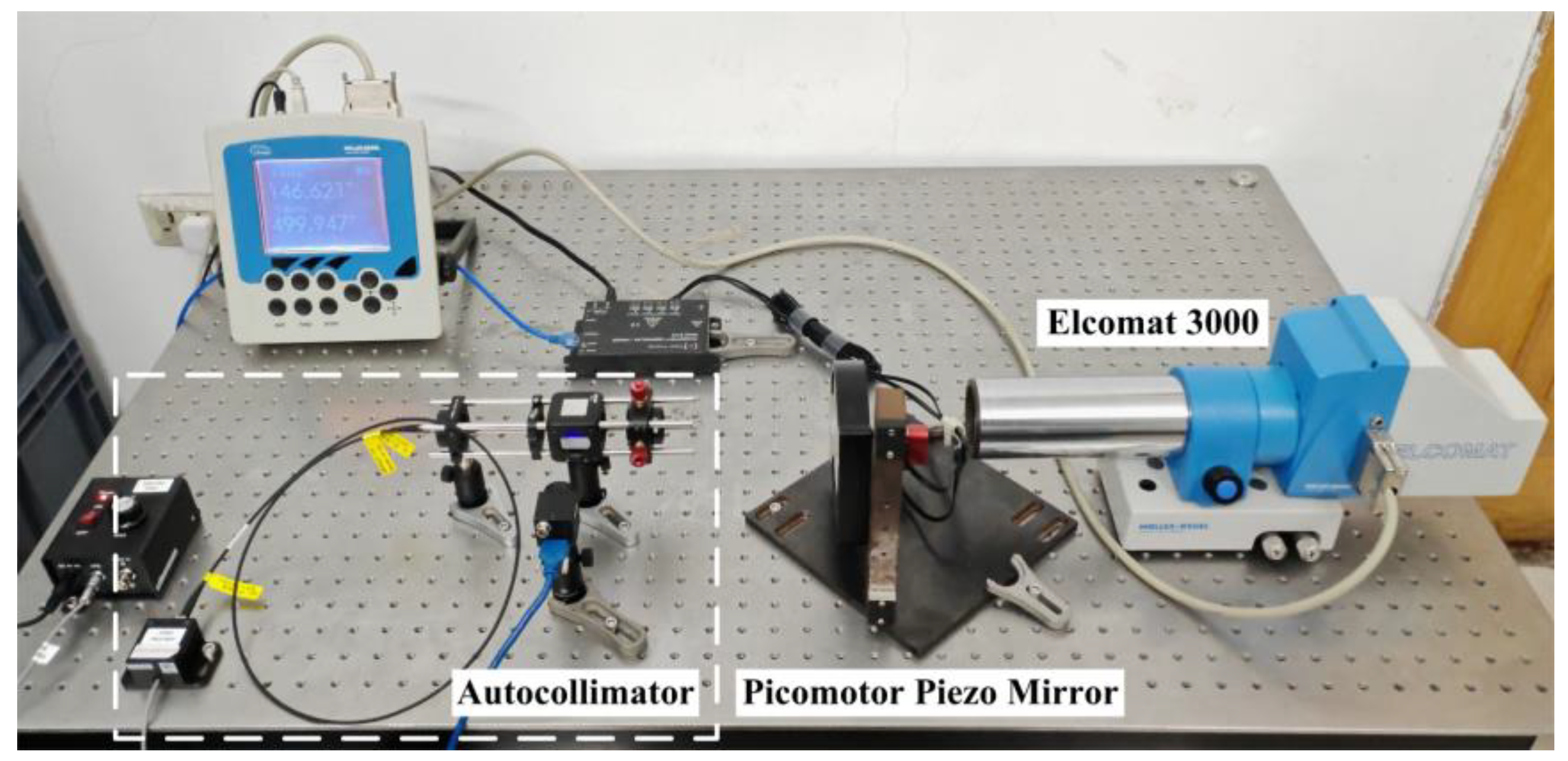

3. Experiment

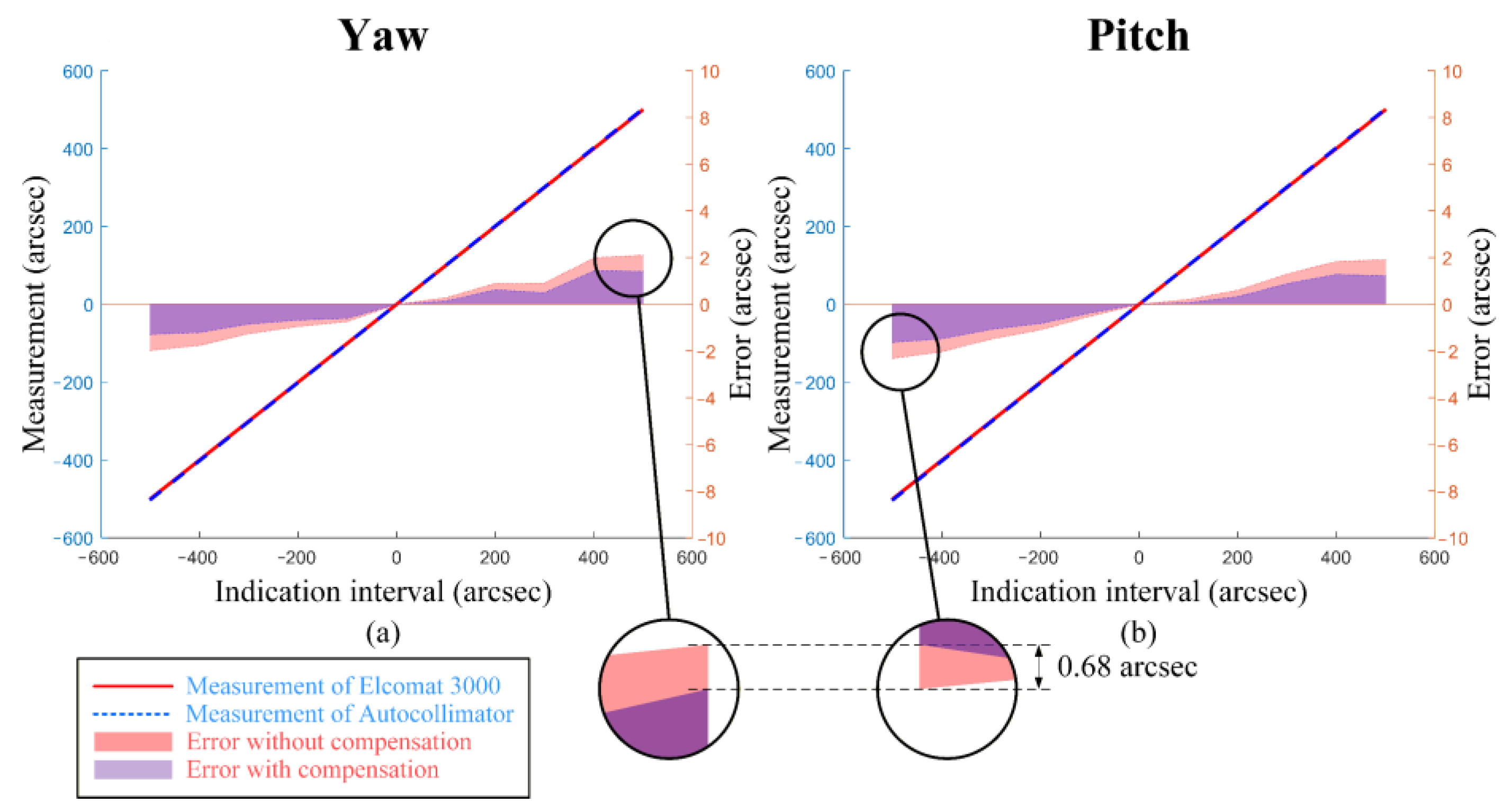

3.1. Verification of the Aberration-Based Mechanism

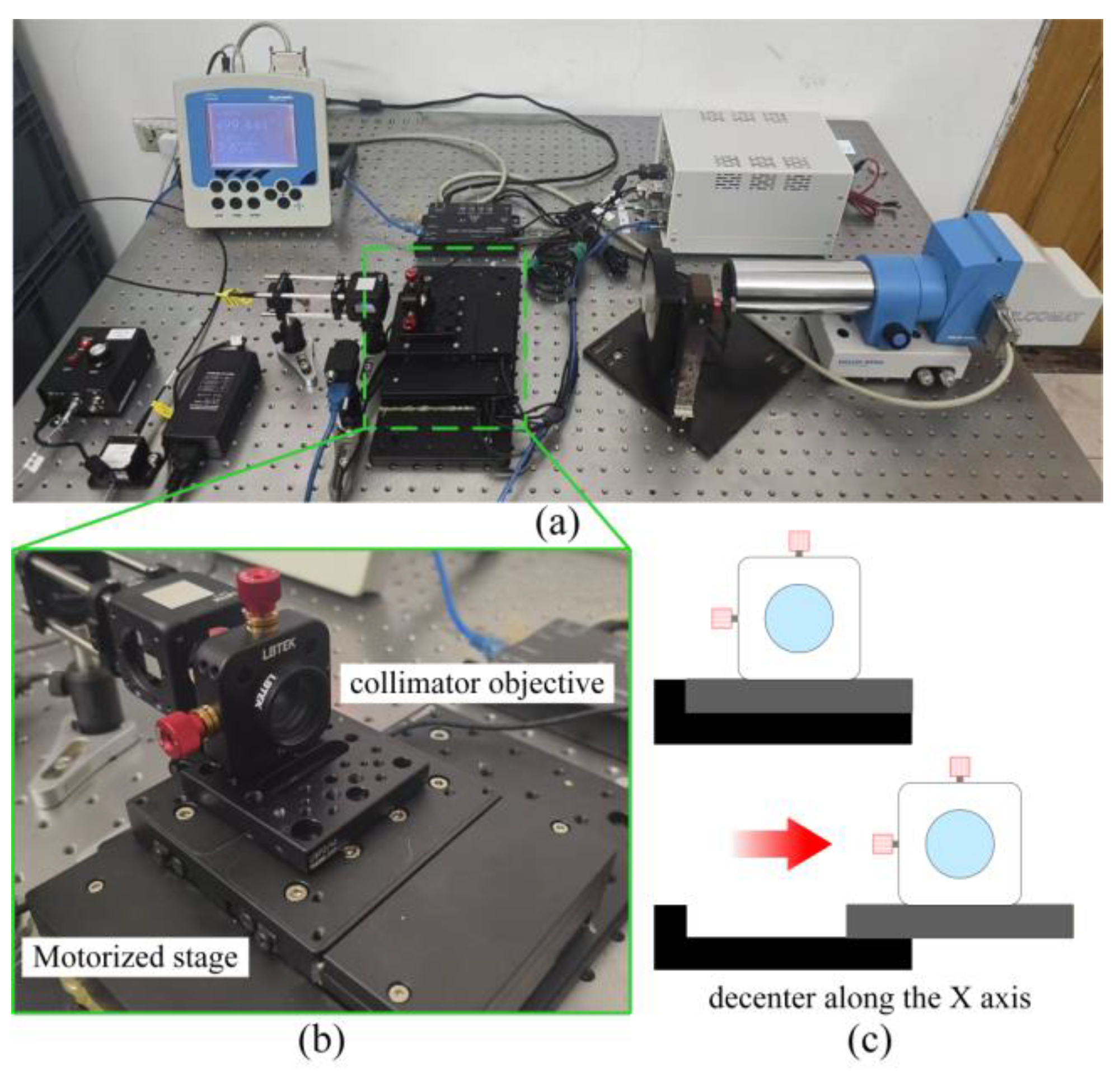

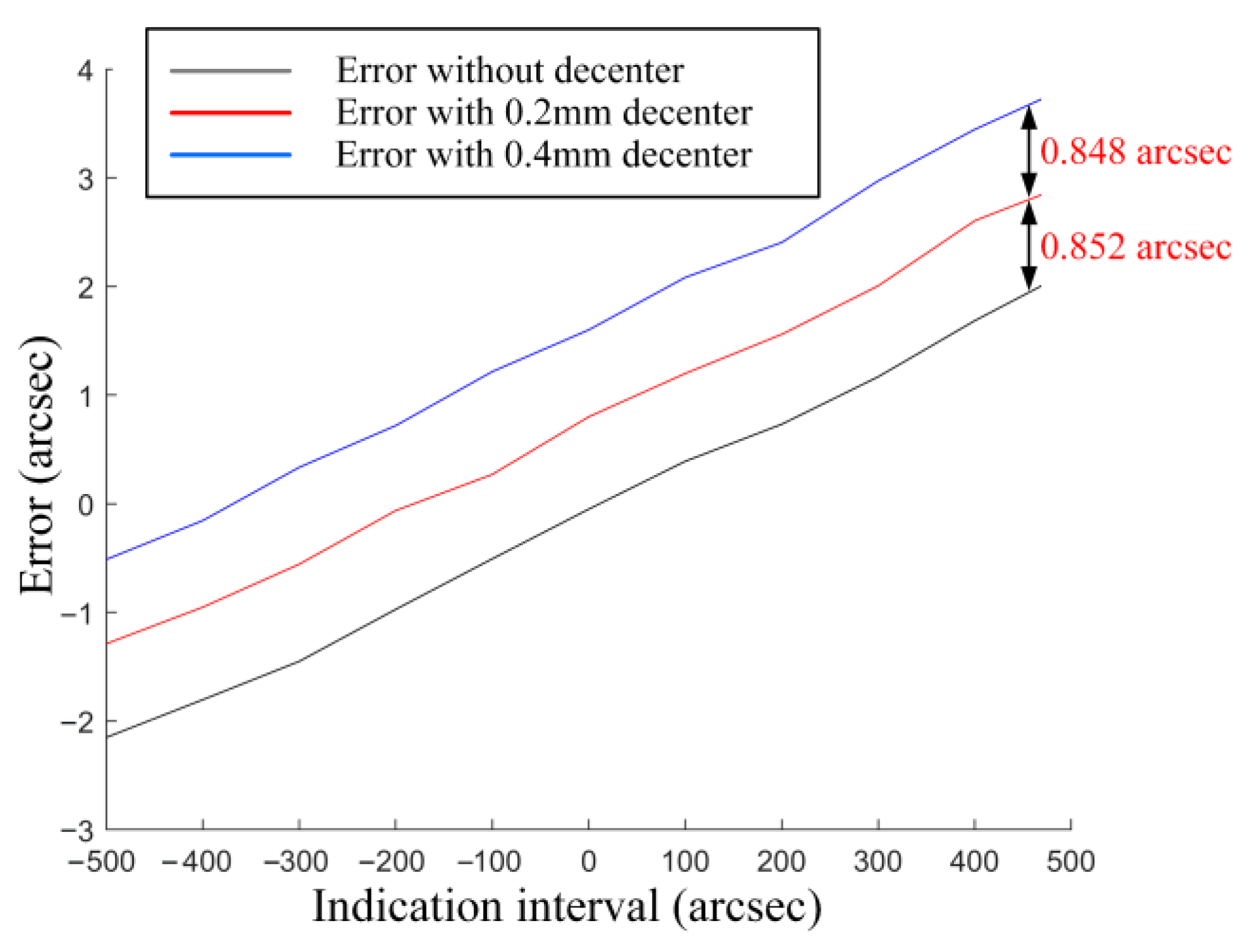

3.2. Verification of the Assembly Deviation Mechanism

4. Discussion

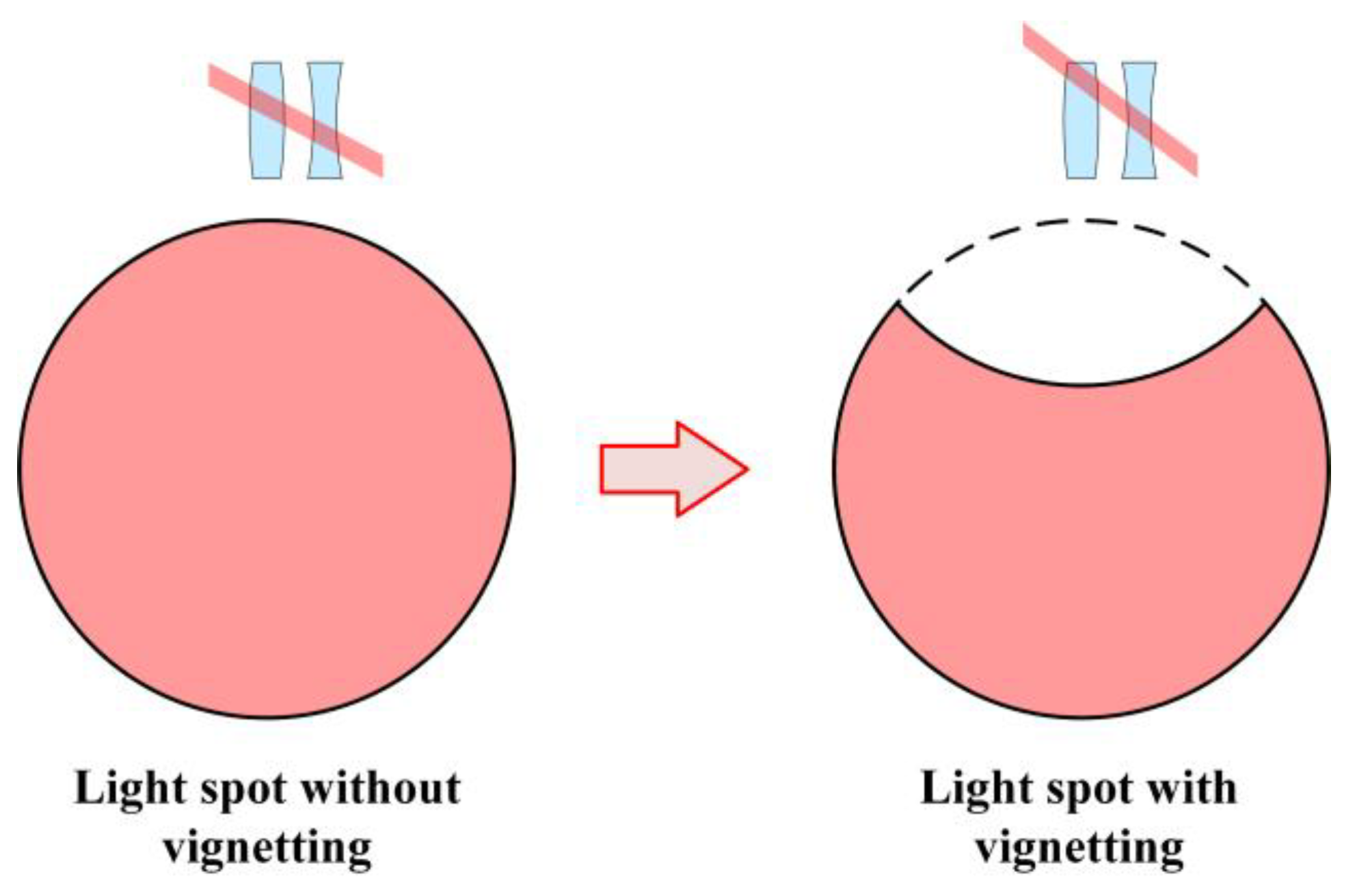

- About the vignetting. As shown in Figure 16, when the optical system has vignetting, the shape of the light spot loses its symmetry. At this point, the idealized circular pupil integration cannot be achieved. This will result in each Zernike coefficient no longer being 0 or an integer multiple of π. In this case, the relationship between the aberration and the angle error is no longer as simple as shown in Equations (11) and (12). However, when the vignetting significantly influences, the collimator objective is not available for an autocollimator anymore. Therefore, when designing the autocollimator, one should avoid the occurrence of vignetting. And that is why the coma is mainly investigated in this work.

- About the center wavelength. The center working wavelength used for all the simulations above was 660 nm, consistent with the nominal wavelength of the light source used in the experiments. Obviously, the real center wavelength is not exactly 660 nm. When the center wavelength alters, the linear relationship presented in this article is still applicable, but only differs in value. Figure 17 shows the simulation results at different wavelengths. Since the wavelength range of the used light source is 660 ± 10 nm, we selected 650 nm and 670 nm for further investigation. It could be seen that the angle measurement still exhibits good linearity within the measurement range. The only difference is that when the wavelength changes, the slope of the error line undergoes a slight alteration. That is because the values of the aberration coefficients will change under different wavelengths.

- About the chromatic aberration. Some autocollimators equip two light sources with significantly different wavelengths to implement measurement of three rotation angles simultaneously [20]. Longitudinal and lateral chromatic aberrations would cause different wavelengths to focus at different positions. Therefore, the influence of chromatic aberrations on angle measurement should be taken into account. An achromatic objective is an effective solution for such autocollimator designs.

- About the type of lens. Both the simulations and experiments in this paper investigate an optical system with biconvex lenses. During the derivation of the formulas in this paper, the optical system was treated as a black box. Discussions on aberrations and assembly errors were all conducted at the exit pupil. Therefore, the conclusions drawn in this paper remain valid when the optical lens is a meniscus lens or any other type. In addition, it can be known from Equations (11) and (12) that some optical system parameters have an impact on the measurement error. For instance, when other variables remain constant, the higher the optical power of the lens, the greater the angle error. This can help us select or design a suitable collimator objective for the autocollimator.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAD | Sensitivity of Assembly Deviation |

| MCA | Mechanical coordinate axis |

| OAR | Optical Axis Ray |

| MFOV | Marginal field of view |

| OFOV | On-axis field of view |

| AFA | Aberration field axis |

| MTF | Modulation Transfer Function |

| BS | Beam splitter |

| CL | Collimator lens |

| RMS | Root mean square |

References

- Wang, S.T.; Ma, R.; Cao, F.F.; Luo, L.B.; Li, X.H. A Review: High-Precision Angle Measurement Technologies. Sensors 2024, 24, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.L.; Di, H.G.; Yan, Q.; Wang, L.; Hua, D.X. Autocollimation-Based Roll Angle Sensor Using a Modified Right-Angle Prism for Large Range Measurements. Sensors 2025, 25, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, J.P.; Su, J.J.; Miao, L.J.; Huang, T.C. Research on Field Application Technology of Dynamic Angle Measurement Based on Fiber Optic Gyroscope and Autocollimator. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 15308–15317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjid, M.A. Improvements of the calibration of the electronic level and by a new multiple reflections technique-based setup. Measurement 2025, 256, 118115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.P.; Konyakhin, I.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, W.; Wen, D.D.; Zou, X.H.; Guo, J.Q.; Liu, Y. Error compensation for long-distance measurements with a photoelectric autocollimator. Opt. Eng. 2019, 58, 104112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Tan, X.R.; Tan, J.B.; Fan, Z.G. Rigid geometric-optics autocollimation model and its theoretical analysis based on ray-tracing method. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Advanced Optical Manufacturing and Testing Technology: Optical Test, Measurement Technology, and Equipment, Suzhou, China, 26–29 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.P.; Yan, J.; Cui, J.W.; Guo, J.Q.; Kulikov, A.; Kongyakhin, I.; Nikitin, M.; Guo, Y.R.; Wen, D.D. Research on the influence of aperture process defects on the measurement precision and accuracy of autocollimator and compensation methods. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 47504–47514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Zhang, W.X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Tan, J.B. Nanoradians level high resolution autocollimation method based on array slits. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 25690–25705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuetterer, G. Reticles in autocollimators: Change in image quality due to changed coherence properties. In Proceedings of the 11th European Seminar on Precision Optics Manufacturing, Teisnach, Germany, 9–10 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovchy, I.L. Modeling a broad-band single-coordinate autocollimator with an extended mark and a detector in the form of a linear-array camera. J. Opt. Technol. 2021, 88, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovchy, I.L. Modeling the parameters of a two-coordinate autocollimator with a multi-element mark and a matrix photodetector. J. Opt. Technol. 2024, 91, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagne, H.; Lou, Z.F.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, J.J. Roll Angle Error Measurement of Linear Guideways Using Mini Autocollimators. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mechatronics and Robotics Engineering (ICMRE), Milan, Italy, 27–29 February 2024; pp. 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Eves, B.J.; Leroux, I.D. Autocollimators: Plane angle measurand ambiguities and the impact of surface form. Metrologia 2023, 60, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukuma, H.; Asumi, Y.; Nagaoka, M.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W. An autocollimator with a mid-infrared laser for angular measurement of rough surfaces. Precis. Eng.-J. Int. Soc. Precis. Eng. Nanotechnol. 2021, 67, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Tan, S.L.; Murata, D.; Maruyama, T.; Ito, S.; Chen, Y.L.; Gao, W. Ultra-sensitive angle sensor based on laser autocollimation for measurement of stage tilt motions. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 2788–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Li, Y.C.; Zhang, D.X.; Xing, H.Y.; Tao, Z.X.; Tan, J.B. Research on the Influence Model of Collimating Lens Aberrations in Autocollimation System Based on the Ray-Tracing Method. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.B.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, T. Effect of Optical Aberrations on Laser Transmission Performance in Maritime Atmosphere Turbulence. Photonics 2025, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Ameur, K.; Hasnaoui, A. Relationship Between Aberration Coefficients of an Optical Device and Its Focusing Property. Photonics 2024, 11, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.S.; Qin, T.X.; Li, W.B.; Wang, X.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Liu, Z.Y. Astigmatism analysis and correction method introduced by an inclined plate in a convergent optical path. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.H.; Cai, S.; Qiao, Y.F. Design, fabrication, and verification of a three-dimensional autocollimator. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 9986–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables Name | Definitions of Variables |

|---|---|

| Pitch angle, the angle subtended between the principal ray and the optical axis in the YOZ plane | |

| Yaw angle, the angle subtended between the principal ray and the optical axis in the XOZ plane | |

| Focal length of the collimator objective | |

| The image height of the light spot centroid for the off-axis parallel beam’s image spot in the YOZ plane | |

| The image height of the light spot centroid for the off-axis parallel beam’s image spot in the XOZ plane | |

| The image height of the perfect image point in the YOZ plane | |

| The image height of the perfect image point in the XOZ plane | |

| The image height of the i-th ray from the off-axis parallel beam in the YOZ plane | |

| The image height of the i-th ray from the off-axis parallel beam in the XOZ plane | |

| The coordinate in the tangential direction of the intersection point between the i-th ray from the off-axis parallel beam and the actual wavefront | |

| The coordinate in the sagittal direction of the intersection point between the i-th ray from the off-axis parallel beam and the actual wavefront | |

| The refractive index in the image space of the optical system | |

| The exit pupil distance of the optical system | |

| The exit pupil diameter of the optical system | |

| The wavefront error in the exit pupil |

| Variable Name | Definitions of Variables |

|---|---|

| The center of curvature of optical surface without assembly deviation lies on the reference axis | |

| The center of curvature of optical surface with assembly deviation lies off the reference axis | |

| The surface inclination of optical surface with assembly deviation | |

| The center deviation of the optical surface with assembly deviation | |

| The vertex deviation of the optical surface with assembly deviation from the reference axis | |

| Object space center of the optical surface | |

| Image space center of the optical surface | |

| Center of the entrance pupil for the optical surface | |

| Center of the exit pupil for the optical surface | |

| The deviation of the object space center of the optical surface with assembly deviation from the reference axis | |

| The deviation of the image space center of the optical surface with assembly deviation from the reference axis | |

| The deviation of the entrance pupil center of the optical surface with assembly deviation from the reference axis | |

| The deviation of the exit pupil center of the optical surface with assembly deviation from the reference axis | |

| Paraxial object height of the optical surface | |

| Paraxial image height of the optical surface | |

| Entrance pupil radius of the optical surface | |

| Exit pupil radius of the optical surface | |

| The object intersection distance of the optical surface | |

| Entrance pupil distance of the optical surface | |

| Radius of curvature of the optical surface | |

| The angle subtended between the optical axis ray and the reference axis | |

| The deviation of the intersection point between the optical axis ray and the optical surface with assembly deviation from the reference axis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chang, D.; Yu, T.; Tan, J. Influence of Lens Systematic Errors on Autocollimator Angle Measurement: Theoretical and Experimental Explanations. Sensors 2025, 25, 7654. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247654

Li Y, Zhang S, Chang D, Yu T, Tan J. Influence of Lens Systematic Errors on Autocollimator Angle Measurement: Theoretical and Experimental Explanations. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7654. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247654

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuechao, Shuo Zhang, Di Chang, Tongmiao Yu, and Jiubin Tan. 2025. "Influence of Lens Systematic Errors on Autocollimator Angle Measurement: Theoretical and Experimental Explanations" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7654. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247654

APA StyleLi, Y., Zhang, S., Chang, D., Yu, T., & Tan, J. (2025). Influence of Lens Systematic Errors on Autocollimator Angle Measurement: Theoretical and Experimental Explanations. Sensors, 25(24), 7654. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247654