Improved Moth-Inspired Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Controller

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Robot locomotion in complex, obstacle-rich environments is susceptible to interference, leading to fragmented or discontinuous search paths and compromising their completeness.

- (2)

- During the initial search phase, current algorithms frequently employ random directional initialization. This contrasts with natural moth strategies, which leverage mechanisms like airflow direction sensing and bilateral olfactory comparison for efficient initial plume detection and localization.

- (3)

- Odor source identification strategies are oversimplified, typically relying solely on whether the current concentration surpasses a predefined threshold. This approach fails to fully exploit the richer sensory information utilized by biological systems, such as dynamic changes in odor intensity, temporal frequency of encounters, and spatial distribution patterns.

- (4)

- The use of fixed parameter settings in algorithms hinders their ability to adapt to the inherent dynamic nature of odor environments. This rigidity contrasts sharply with the remarkable adaptive capacity of biological organisms, which continuously adjust their behavior and parameters in real-time based on environmental feedback.

- (1)

- Employs a rebound strategy to guide the robot in obstacle avoidance;

- (2)

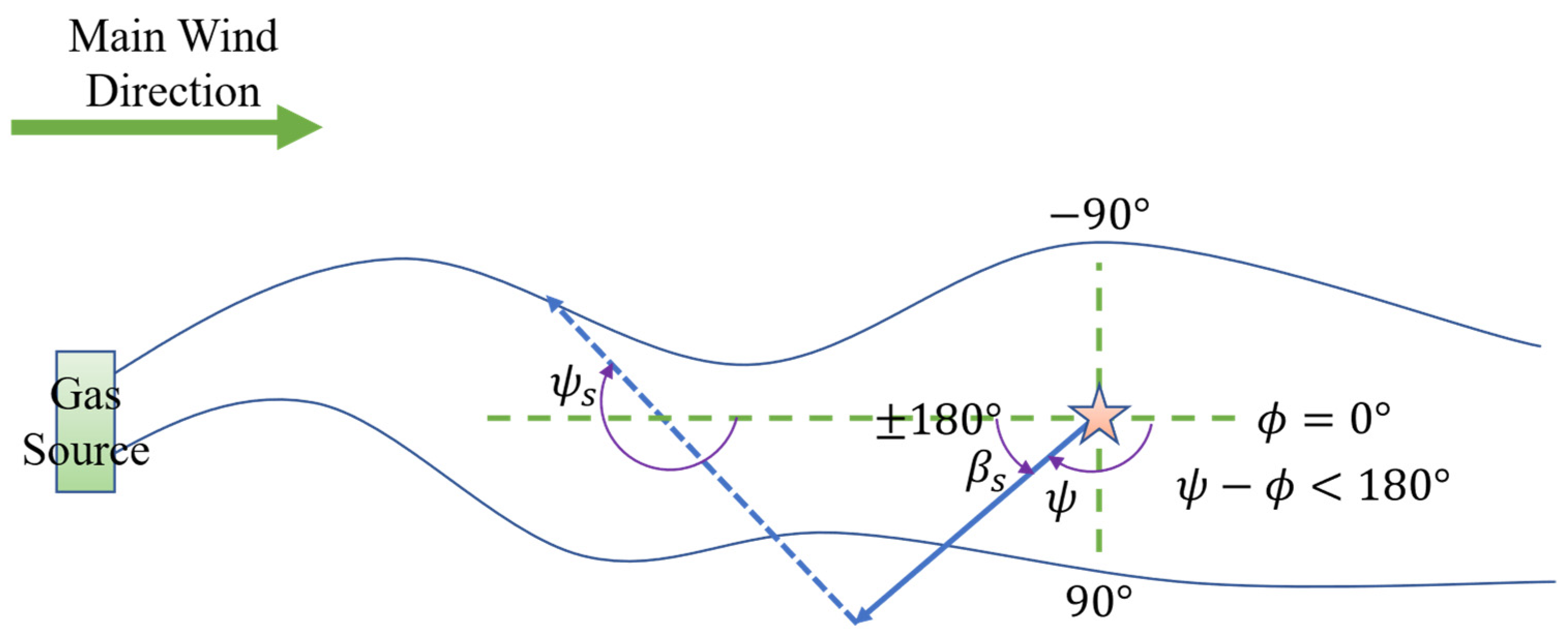

- Promptly records the robot’s movement direction upon exiting the plume and selects the opposite side for the subsequent surge or initial cast based on the detected concentration;

- (3)

- Optimizes the odor source identification strategy by analyzing the spatial clustering of regions where the concentration exceeds a preset threshold;

- (4)

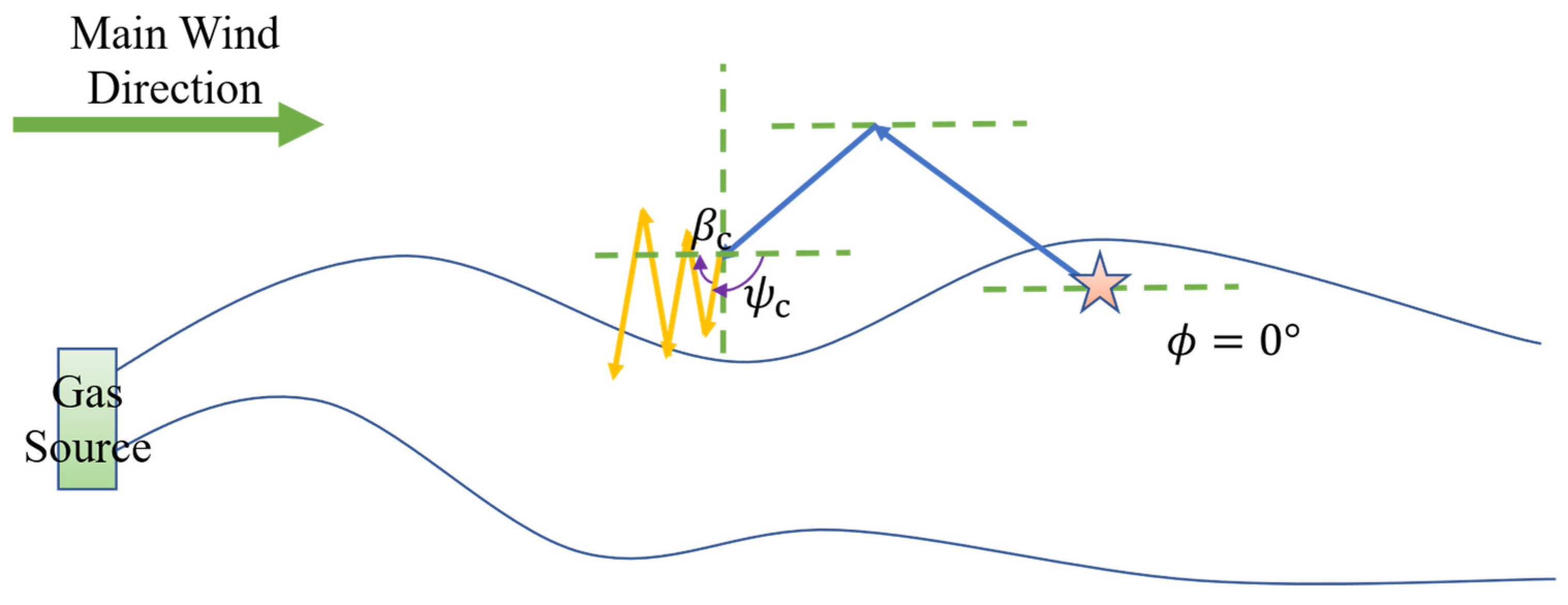

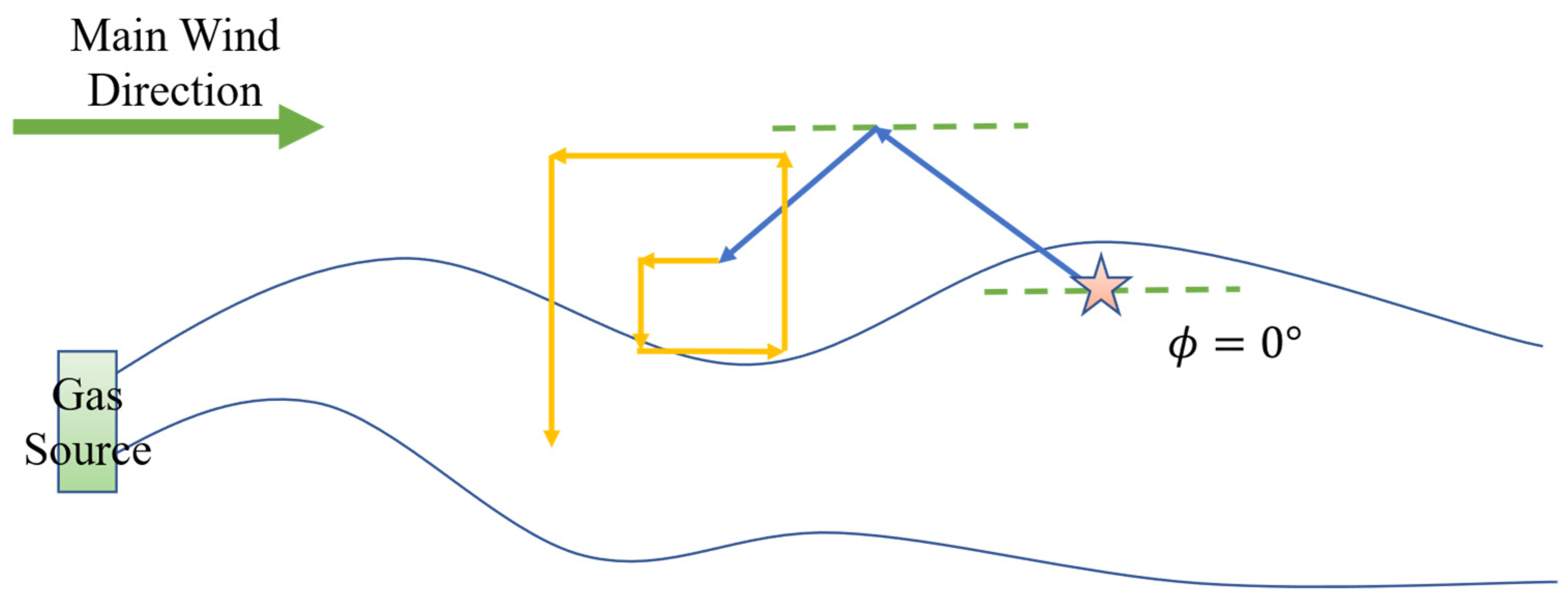

- Integrates the fuzzy inference method with the traditional moth-inspired algorithm to realize dynamic regulation of both parameters and behavior.

2. Methods Improvement

2.1. Obstacle Avoidance Strategy and Search Enhancement

- (1)

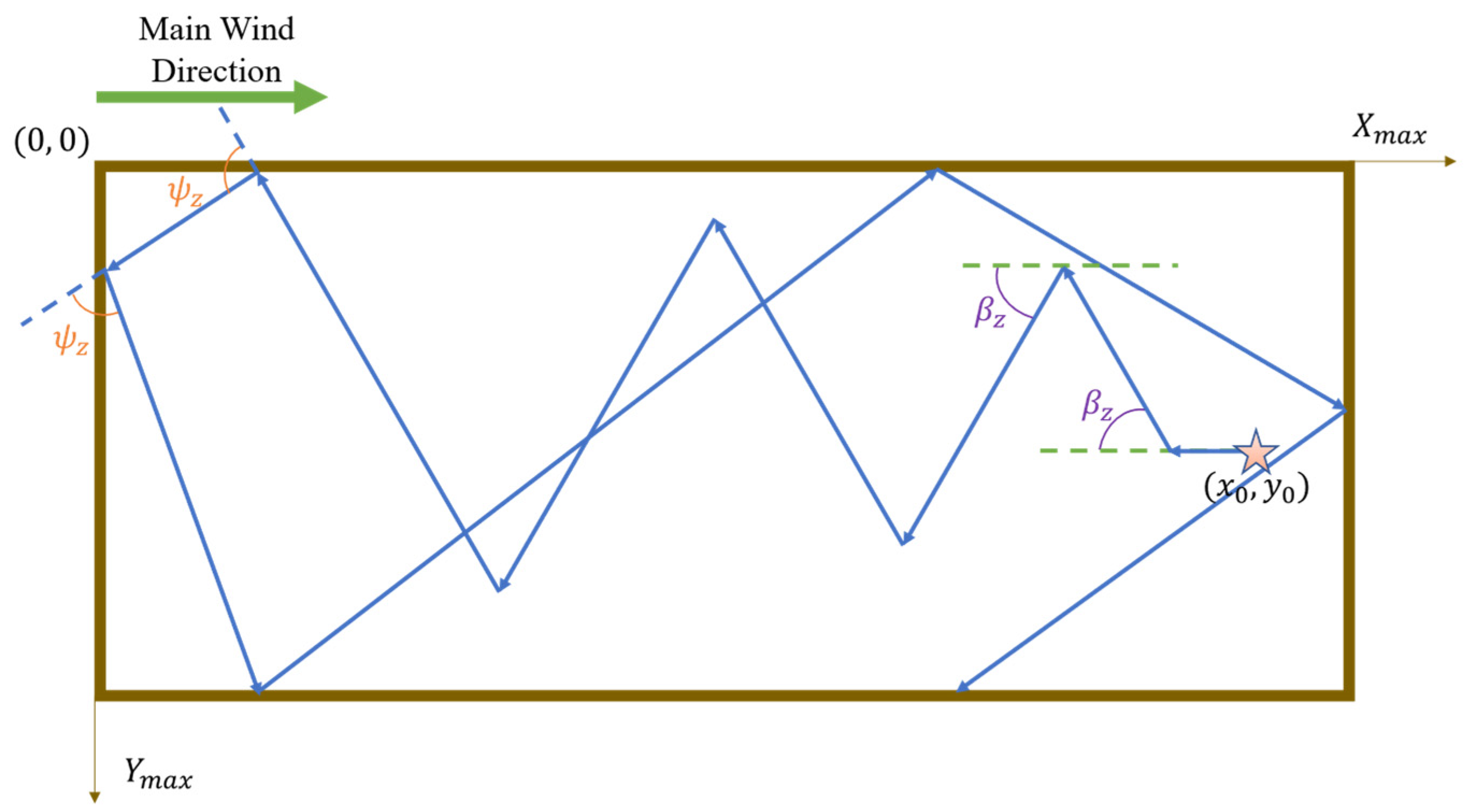

- Linear travel stage: The robot starts from the initial position and travels a fixed distance along the preset direction. This advance distance can be flexibly adjusted based on practical conditions. In real-world applications, experts familiar with the environment often designate a target navigation point based on experience; however, if there is insufficient information regarding the approximate location of the odor source or the gas concentration distribution, this step may be omitted.

- (2)

- Turning Phase: After completing a straight-line motion, if the robot has not detected an odor or met the designated target conditions, it then alternates its turns at a preset angle while maintaining a specific angle relative to the wind direction. By continuously repeating this turning process, the overall motion trajectory forms a “Z” pattern.

2.2. Side Leaving the Plume Guided Search

2.3. Suprathreshold Positional Aggregation

- (1)

- Sorting Suprathreshold Detection Points by Airflow Direction: The robot collects a series of NS detection points, each recording a gas concentration exceeding the threshold CT, which is dynamically adjusted by the fuzzy controller introduced in Section 2.4. These points are then sorted according to the dominant wind direction. Specifically, whenever a concentration reading exceeds the threshold, the detection point is appended to a sequence, which is re-sorted based on the current predominant wind direction so that the detection point nearest the upwind side is positioned at the end of the sequence. This sorting reflects the dynamic trajectory of the robot as it progressively approaches the odor source, with the dominant wind direction obtained by averaging data from the onboard wind sensor.

- (2)

- Evaluating the Aggregation Degree of Detection Points: The sorted NS detection points are then assessed for clustering using a deliberately simple and computationally efficient geometric heuristic. This process involves calculating the distances between consecutive points in the ordered sequence—an operation with linear complexity NS. A cluster is identified if all these distances are below the threshold DS. This lightweight check serves as a practical and efficient alternativeto the computationally intensive probability map maintenance or entropy minimization employed in other methods, directly addressing the criticism of complex models and making it highly suitable for real-time implementation.

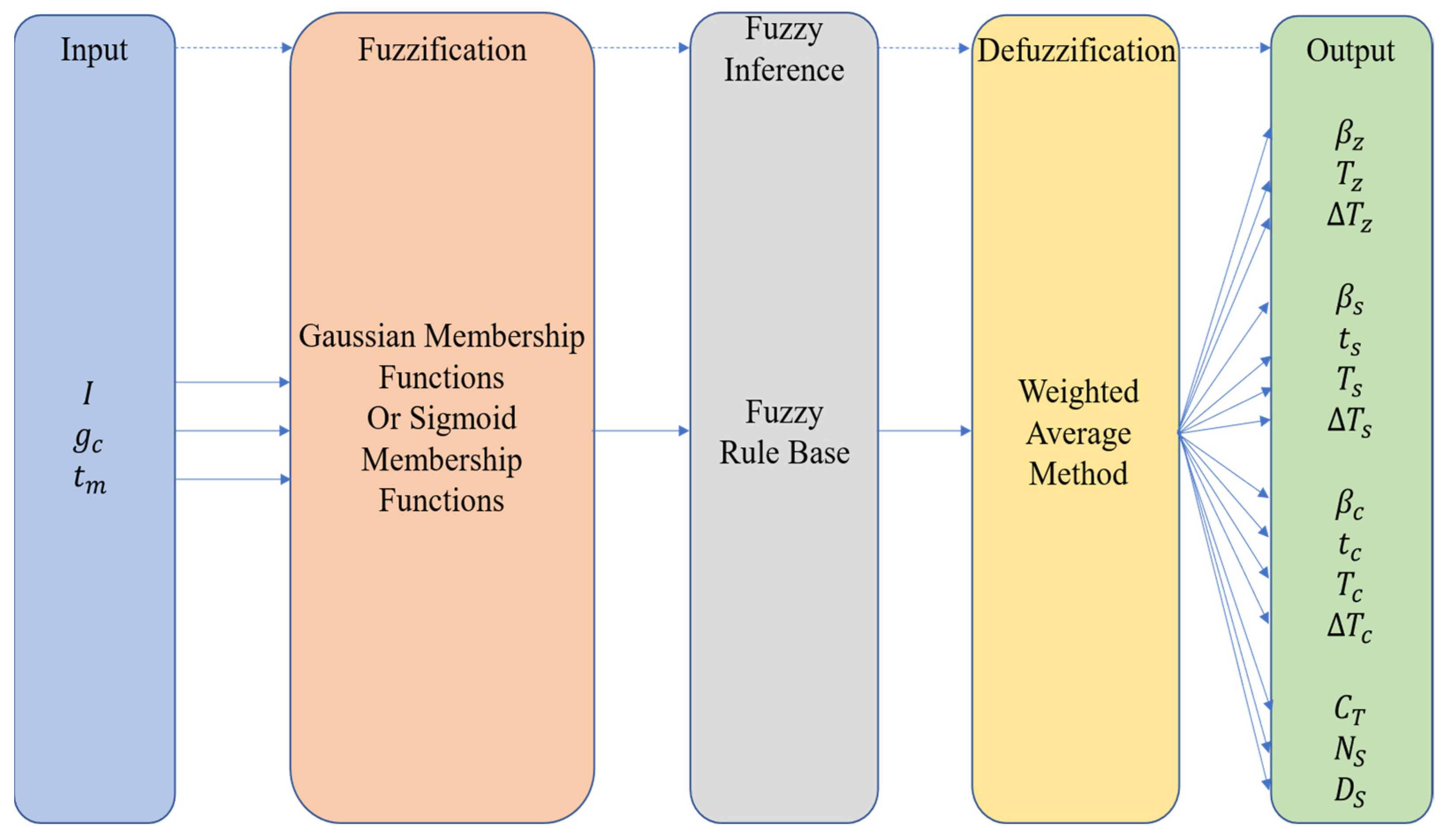

2.4. Design of Fuzzy Controller

2.4.1. Overall Framework of the Fuzzy Controller

2.4.2. Inputs and Outputs of the Fuzzy Controller

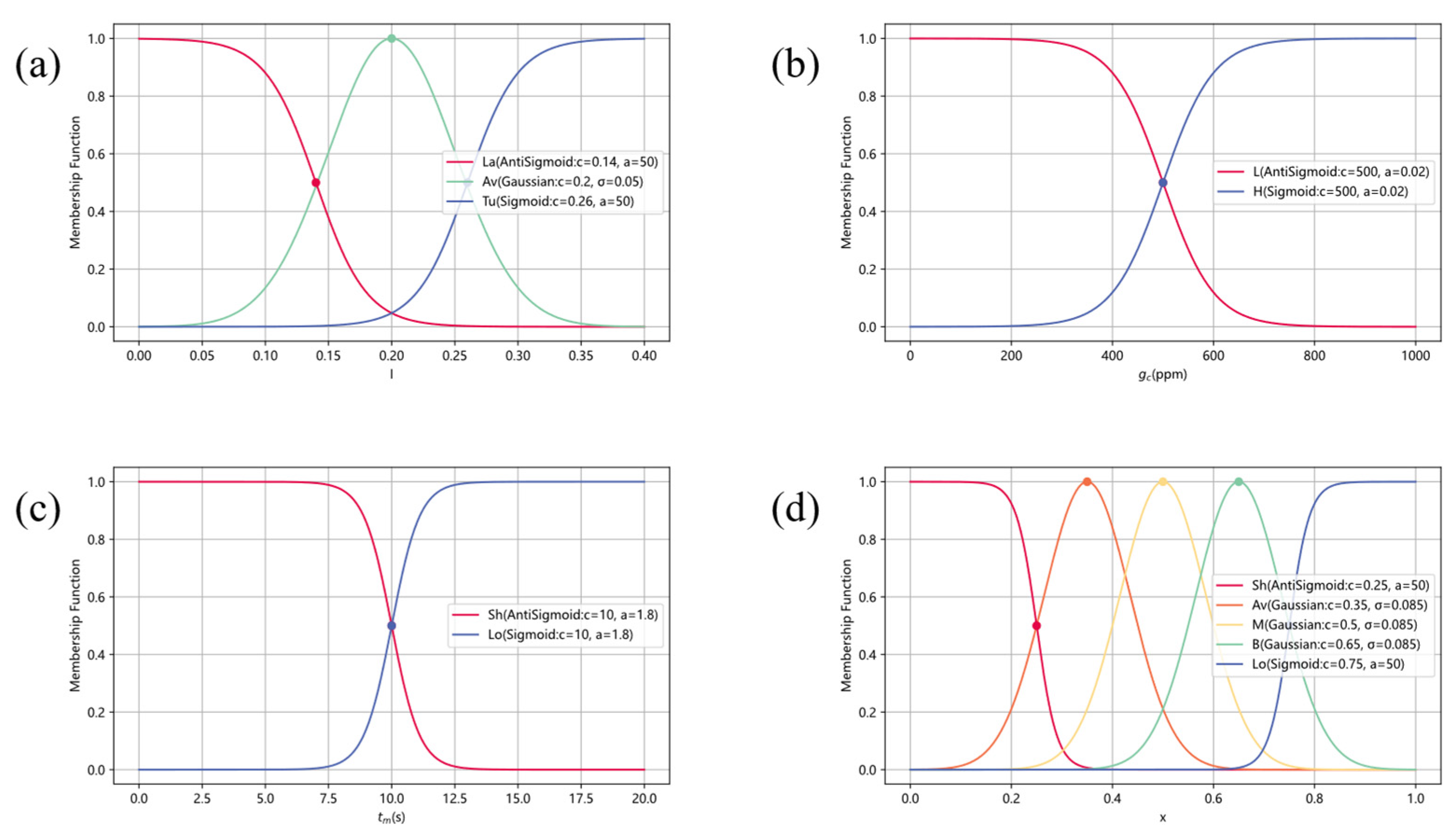

2.4.3. Fuzzification

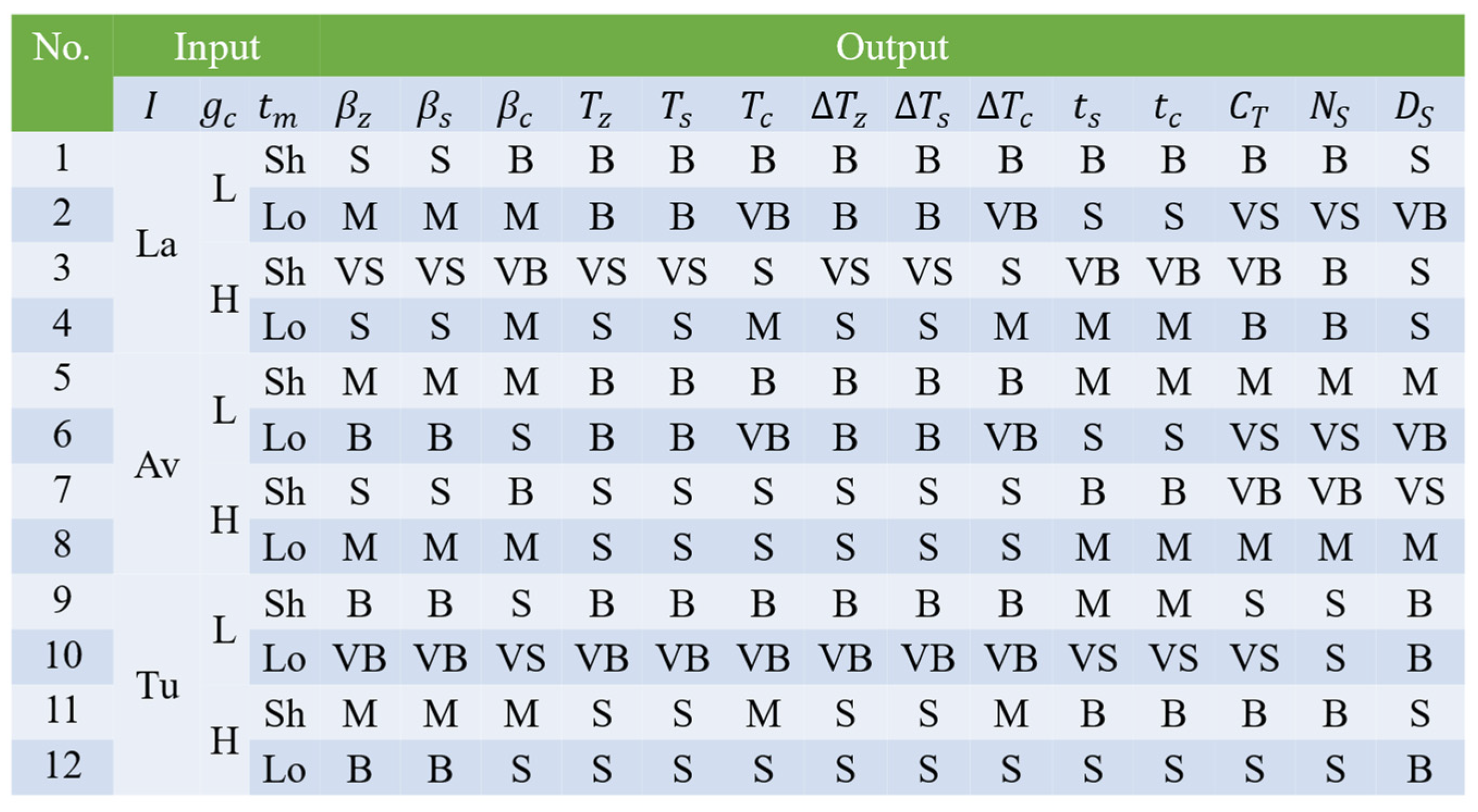

2.4.4. Fuzzy Inference

2.4.5. Defuzzification

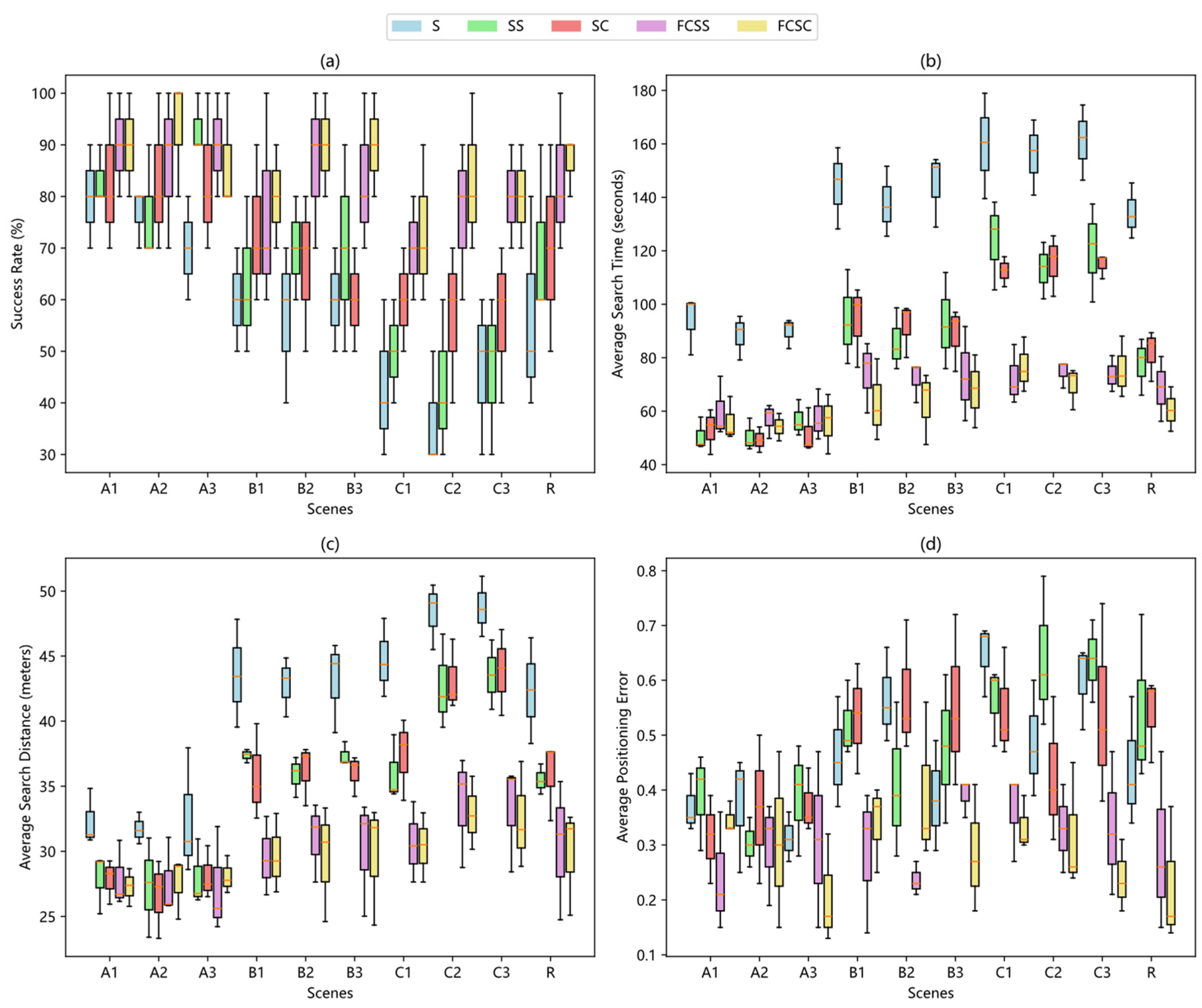

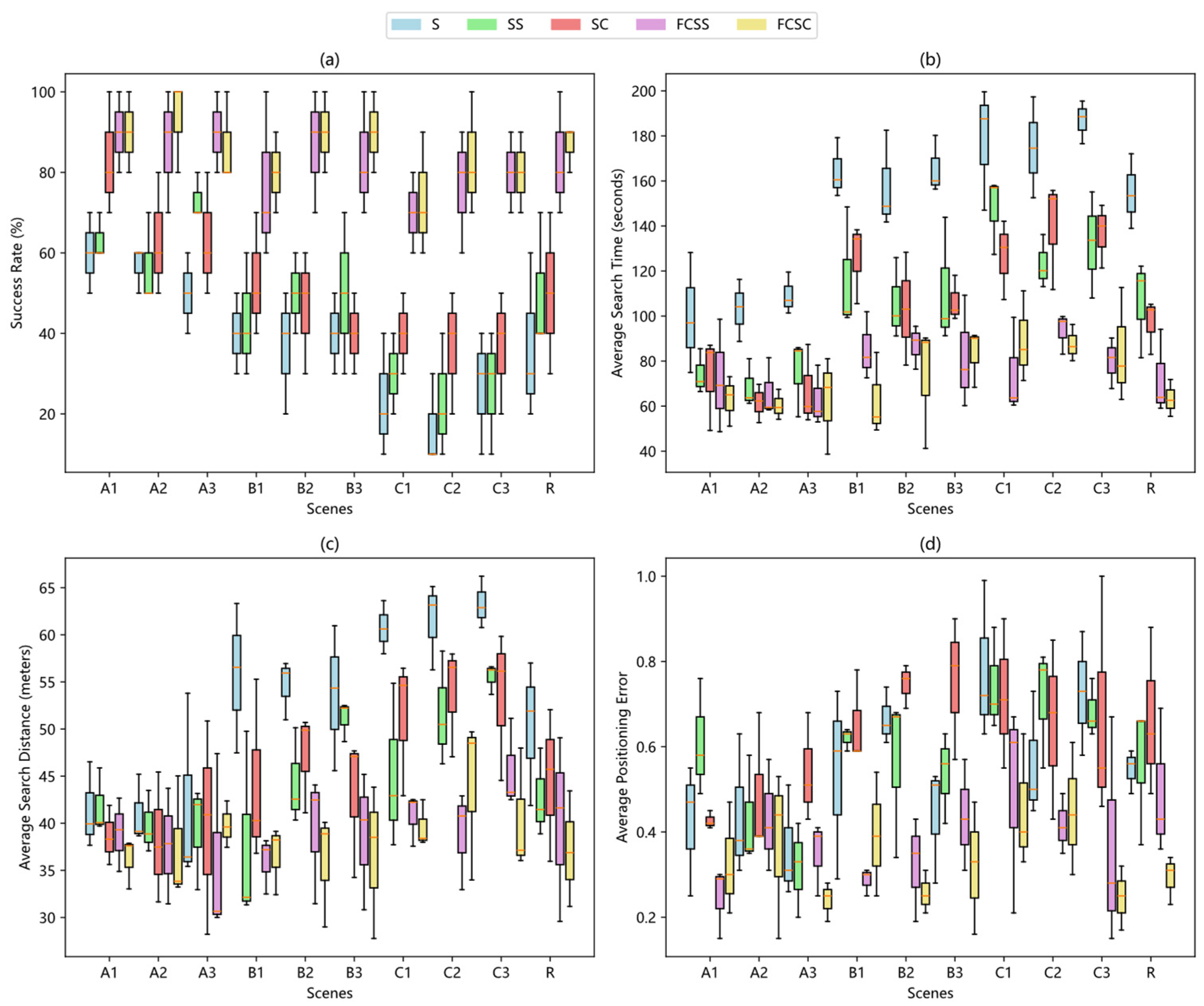

3. Results and Discussion

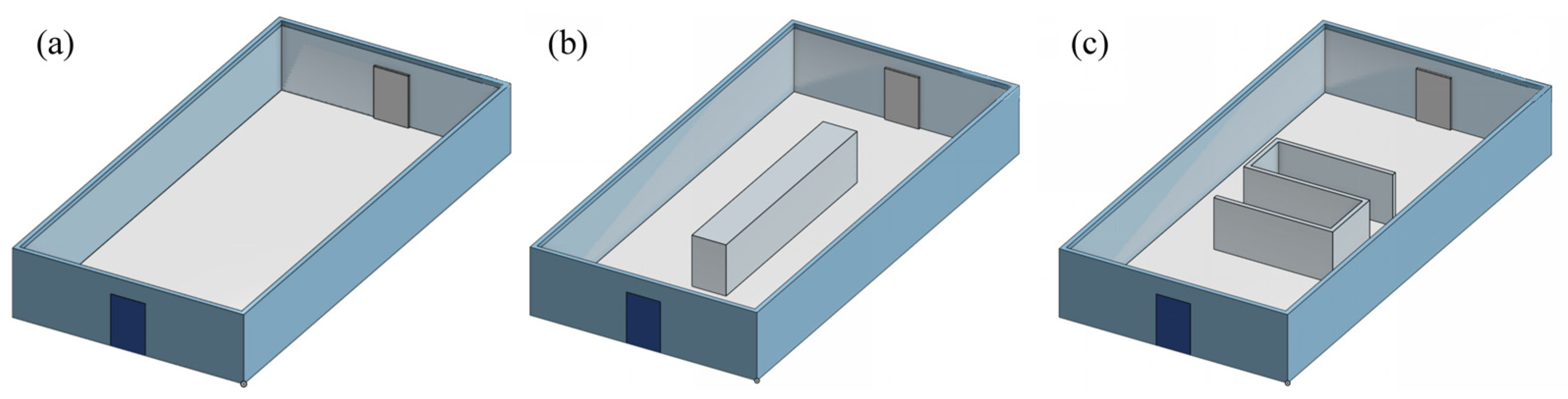

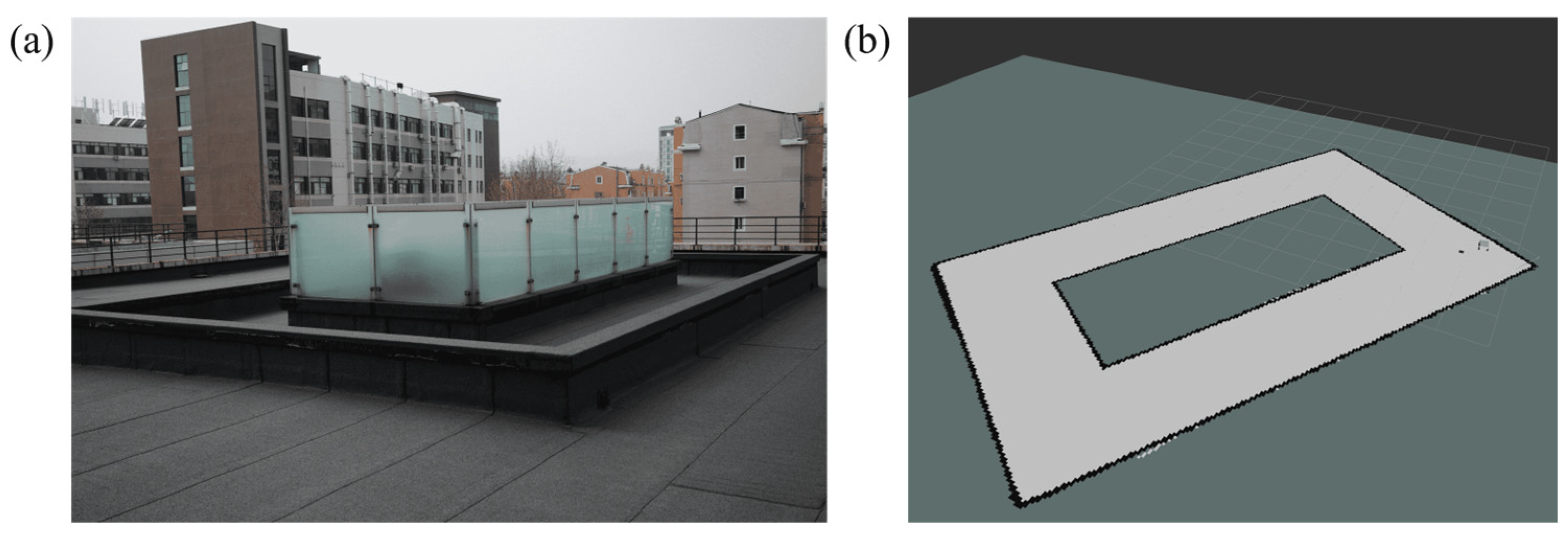

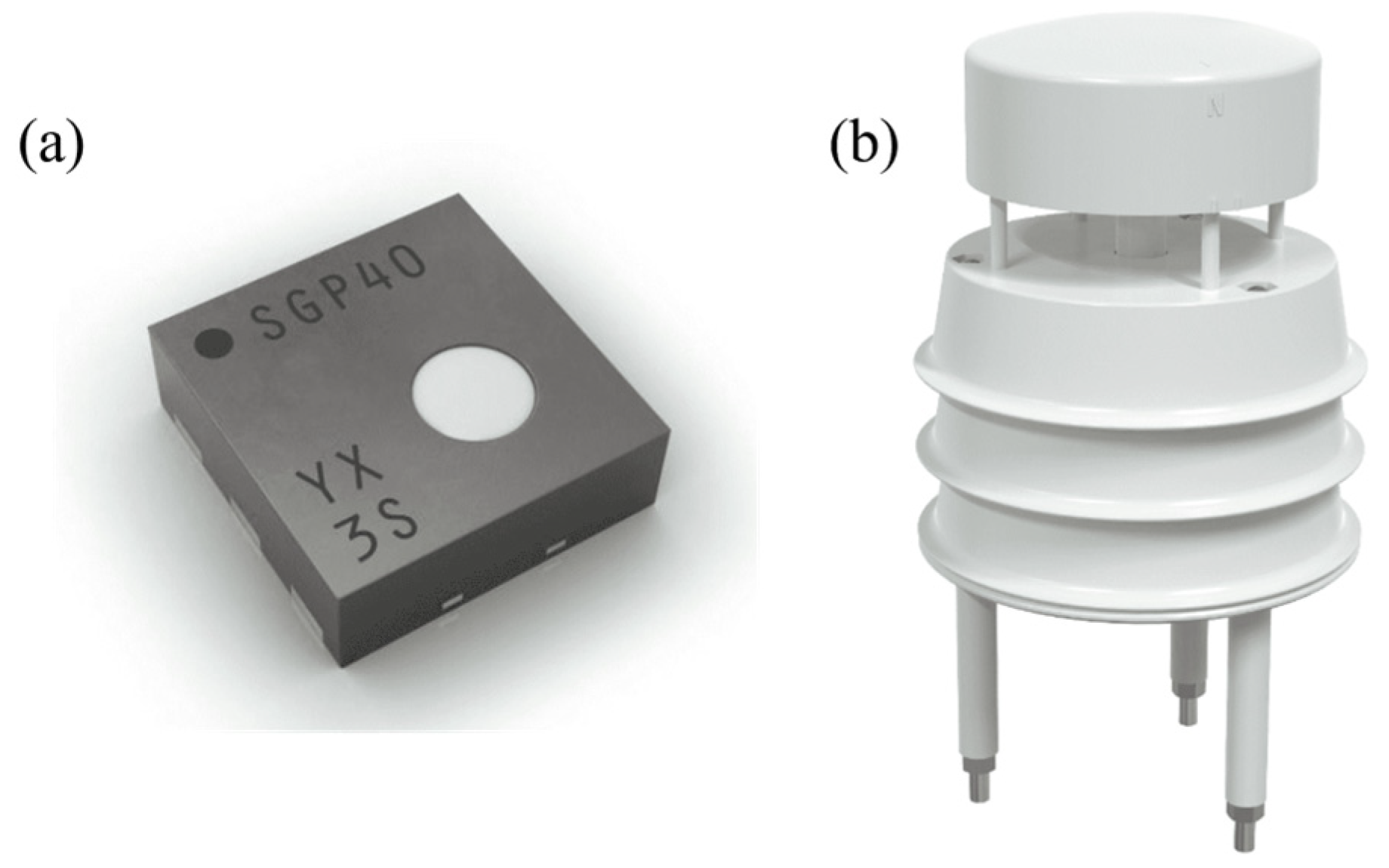

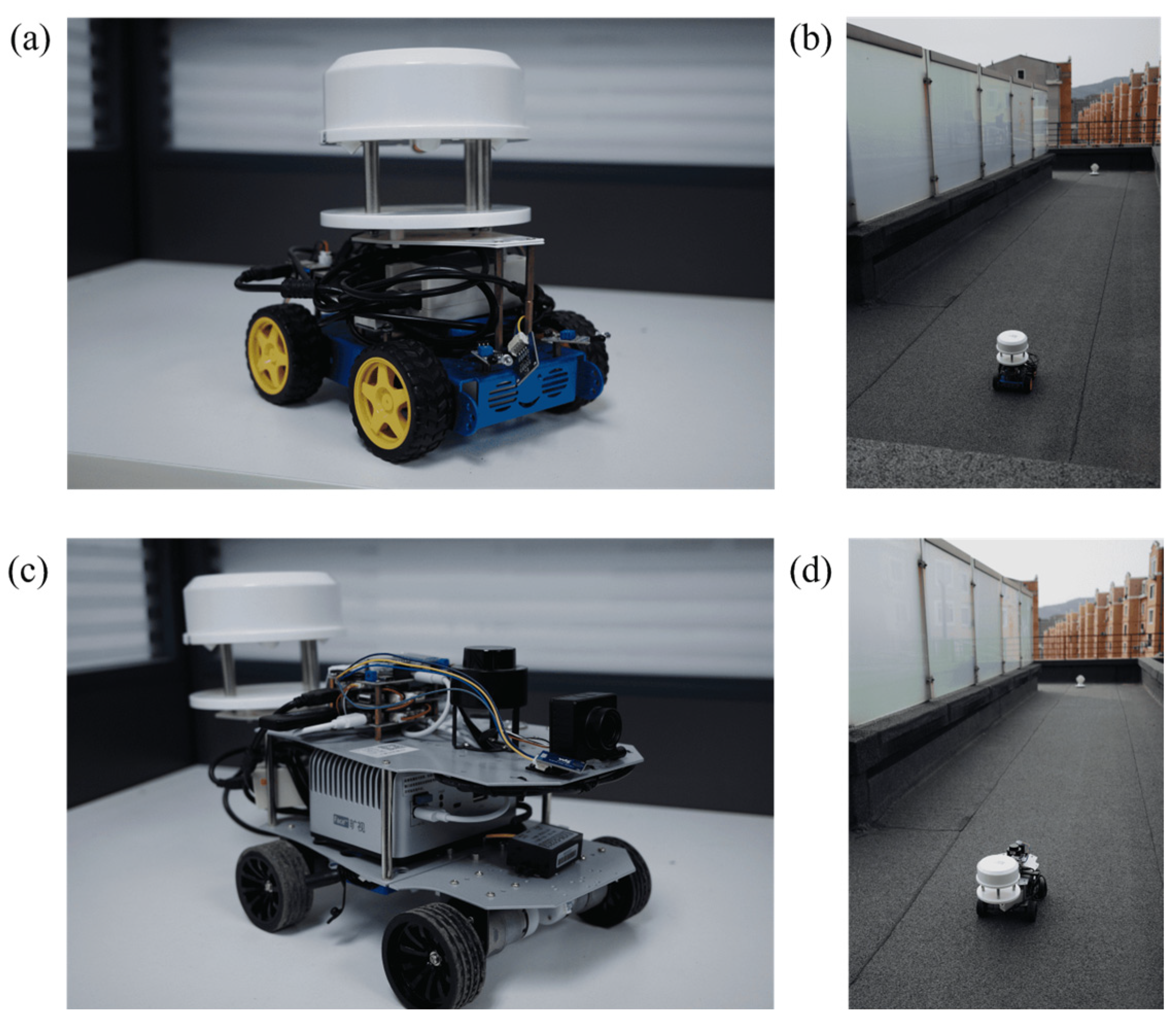

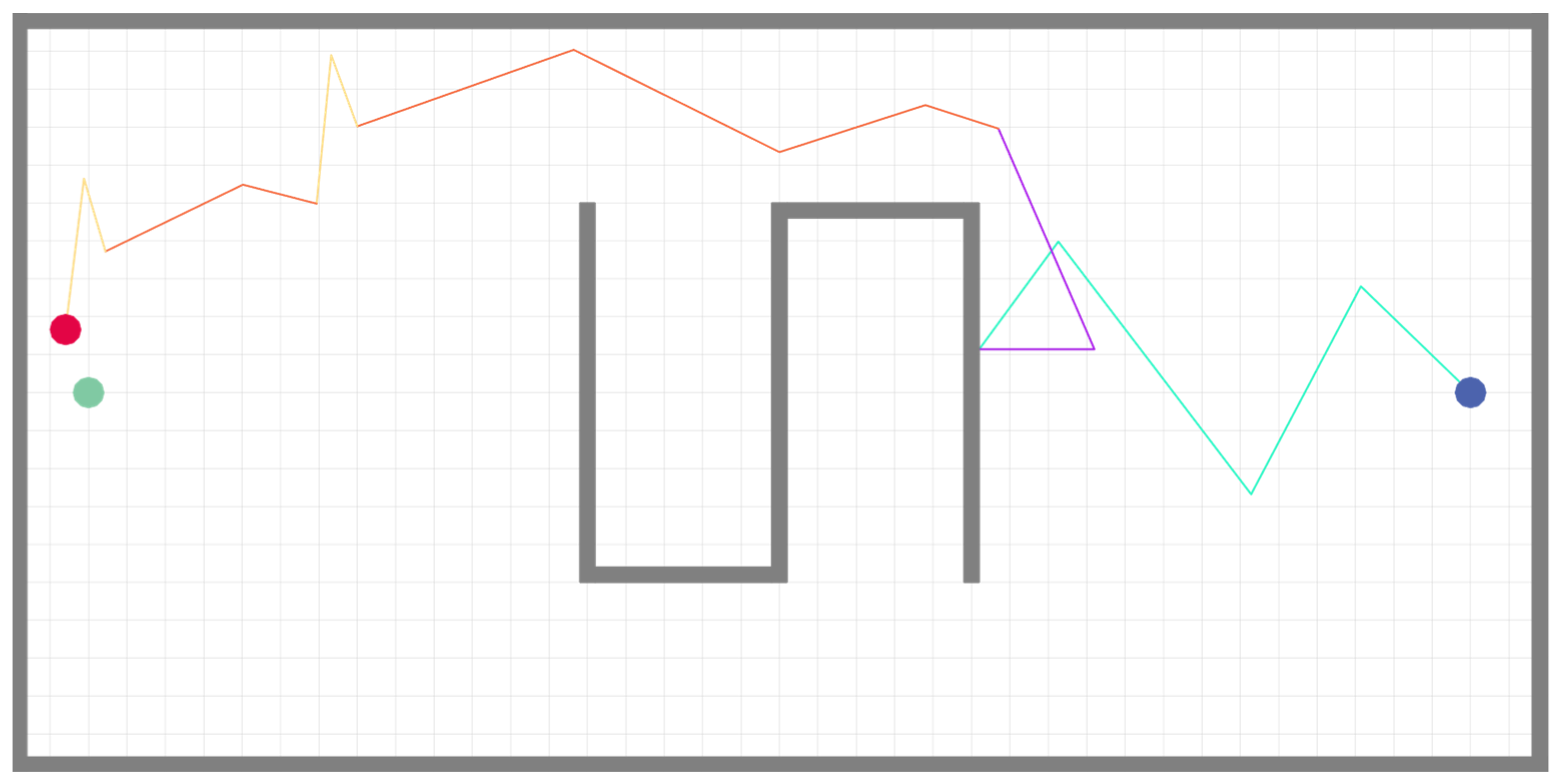

3.1. Experiment

3.2. Results Analysis

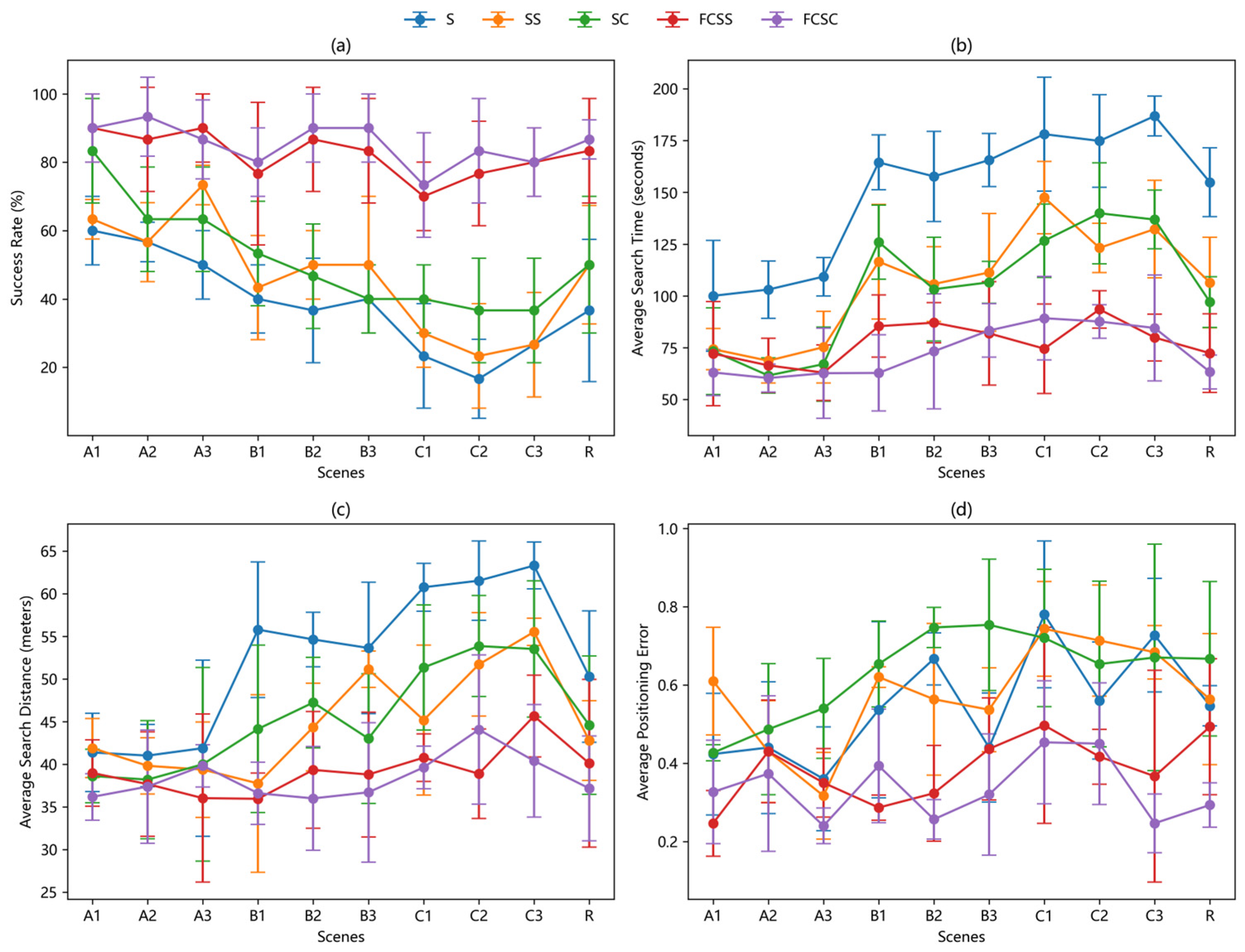

3.3. Generalization Capability Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almqvist, E. History of Industrial Gases; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyıldız, Y.; Tarhan, L. Case study applications in chemistry lesson: Gases, liquids, and solids. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2013, 14, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, H.; Joseph, A.; Park, J.; Comini, E. Advanced micro- and nano-gas sensor technology: A review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, T.; Meng, Q.H.; Ishida, H. Recent progress and trend of robot odor source localization. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2021, 16, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, J. Odor source localization algorithms on mobile robots: A review and future outlook. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 112, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Li, S.; Griffiths, C.; Li, W. Gas source localization and mapping with mobile robots: A review. J. Field Robot. 2022, 39, 1341–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.W.; Yang, J.H.; Tang, Z.L. Experimental Study on Odor Compass System Based on Gas Sensor Array and DSP Technology. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 317–319, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, U.; Kansal, V.; Kumari, S.; Dewangan, R.K.; Mishra, K. A Review of the Evolution of Mobile Robot Odor Source Localization Methods. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, M.; Meng, Q.-H.; Jing, T.; Hou, H.-R. Robot Odor Source Localization in Indoor Environments Based on Gradient Adaptive Extremum Seeking Search. Build. Environ. 2023, 229, 109983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Wu, S.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Development and Simulation of Two Novel Indoor Odor Source Localization Methods Using a Modified Shark Smell Optimization Algorithm. Build. Environ. 2024, 318, 120200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qi, Q.; Liu, Y. Probabilistic Generative Olfactory-Based Navigation in Turbulent Environments for Mars Methane Exploration. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 13167–13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Cheng, L.; Pan, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H. Gas Source Localization Using Dueling Deep Q-Network with an Olfactory Quadruped Robot. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2024, 21, 17298806241255797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, J.H.; Willis, M.A. Biologically-Inspired Search Algorithms for Locating Unseen Odor Sources. In Proceedings of the IEEE ISIC/CIRA/ISAS Joint Conference, Galthersburg, MD, USA, 14–17 September 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, G.; Caselli, E.; Mattoli, V.; Mondini, A.; Dario, P. A Biologically-Inspired Algorithm Implemented on a New Highly Flexible Multi-Agent Platform for Gas Source Localization. In Proceedings of the First IEEE/RAS-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob 2006), Pisa, Italy, 20–22 February 2006; pp. 573–578. [Google Scholar]

- Lochmatter, T.; Martinoli, A. Tracking Odor Plumes in a Laminar Wind Field with Bio-Inspired Algorithms. In Experimental Robotics XI; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Waphare, S.; Gharpure, D.; Shaligram, A.; Kharate, G.K. Implementation of 3-Nose Strategy in Odor Plume-Tracking Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Signal Acquisition and Processing, Bangalore, India, 9–10 February 2010; pp. 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Zhang, Y. Subsumption Architecture Based Mobile Robot Gas Source Localization in Time-Variant-Airflow Environment. In Proceedings of the 31st Chinese Control Conference, Hefei, China, 25–27 July 2012; pp. 4814–4819. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Pang, S. Robotic Odor Source Localization via Adaptive Bio-Inspired Navigation Using Fuzzy Inference Methods. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2022, 147, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Ma, K.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J. Incorporating Animal Klinotaxis Behavior and Bilateral Concentration Information: A 3-D Bio-Inspired Odor Source Localization Algorithm and Its Performance Evaluation. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyk, P.; Badia, S.B.I.; Bernardet, U.; Knüsel, P.; Carlsson, M.; Gu, J.; Chanie, E.; Hansson, B.S.; Pearce, T.C.; Verschure, P.F.M.J. An artificial moth: Chemical source localization using a robot based neuronal model of moth optomotor anemotactic search. Auton. Robot. 2006, 20, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eu, K.S.; Yap, K.M. Chemical plume tracing: A three-dimensional technique for quadrotors by considering the altitude control of the robot in the casting stage. Int. J. Adv. Rob. Syst. 2018, 15, 1729881418755877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, P.; Monroy, J.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. PSGSL: A Probabilistic Framework Integrating Semantic Scene Understanding and Gas Sensing for Gas Source Localization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgues, J.; Marco, S. Wind-independent estimation of gas source distance from transient features of metal oxide sensor signals. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 140460–140469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, J.; Aggarwal, A.; Fricke, G.M.; Moses, M.E. LOCUS: A Multi-Robot Loss-Tolerant Algorithm for Surveying Volcanic Plumes. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC 2020), Electr Network, 9–11 November 2020; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Yang, B.; Huang, J.; Leng, Y.Q.; Fu, C.L. A reinforcement learning fuzzy system for continuous control in robotic odor plume tracking. Robotica 2023, 41, 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithms | Average Success Rate (%) | Average Search Time (s) | Average Search Distance (m) | Average Positioning Error (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 58.67 | 131.01 | 41.02 | 0.47 |

| SS | 66.67 | 86.64 | 35.16 | 0.49 |

| SC | 69.33 | 85.28 | 35.09 | 0.48 |

| FCSS | 82.33 | 68.38 | 30.15 | 0.31 |

| FCSC | 85.33 | 64.25 | 29.74 | 0.30 |

| Algorithms | Average Success Rate (%) | Average Search Time (s) | Average Search Distance (m) | Average Positioning Error (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 38.67 | 149.43 | 52.41 | 0.55 |

| SS | 46.67 | 106.11 | 44.94 | 0.58 |

| SC | 51.33 | 103.84 | 45.45 | 0.63 |

| FCSS | 82.33 | 77.61 | 39.21 | 0.38 |

| FCSC | 85.33 | 72.97 | 38.42 | 0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, Z.; Liu, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, H. Improved Moth-Inspired Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Controller. Sensors 2025, 25, 7633. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247633

Lv Z, Liu D, Wu Y, Zhu H. Improved Moth-Inspired Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Controller. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7633. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247633

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Zhoujing, Dongxu Liu, Yu Wu, and Huichao Zhu. 2025. "Improved Moth-Inspired Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Controller" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7633. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247633

APA StyleLv, Z., Liu, D., Wu, Y., & Zhu, H. (2025). Improved Moth-Inspired Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Controller. Sensors, 25(24), 7633. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247633