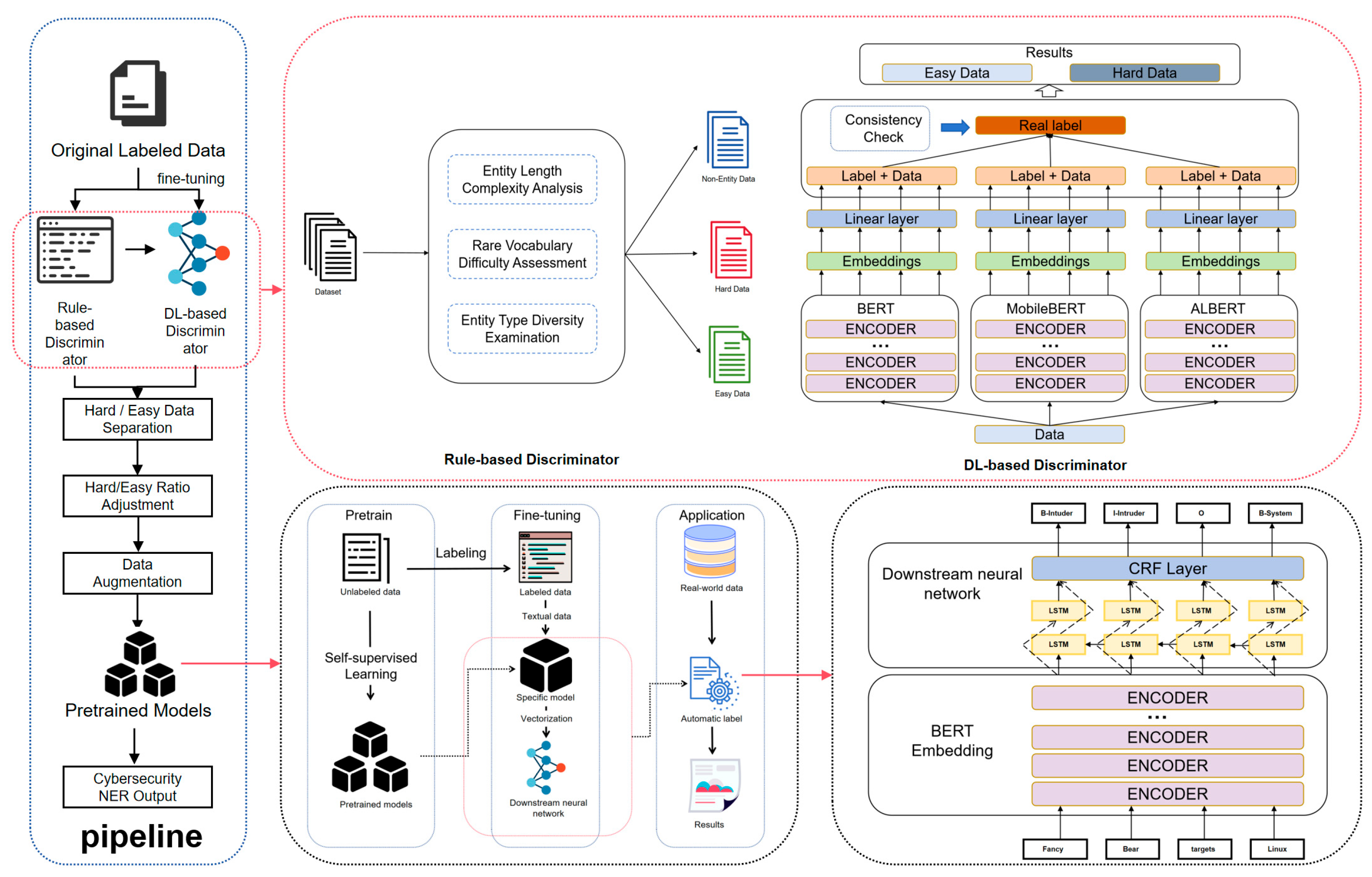

A Cybersecurity NER Method Based on Hard and Easy Labeled Training Data Discrimination

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We propose a novel approach tailored for cybersecurity Named Entity Recognition (NER) datasets, which effectively improves the accuracy of cybersecurity NER.

- (2)

- We design a hybrid discriminator that combines DL-based and rule-based methods to identify hard and easy samples within training data. Together with a data augmentation strategy, this improves the overall quality and diversity of the training set.

- (3)

- Our experiments demonstrate that the optimal hard to easy data ratio for cybersecurity NER is 1:1. And the proposed method not only validates this balance but also significantly enhances the ability of compact models to capture sparse entities. Moreover, the experiments are conducted on relatively small-scale datasets with lightweight models, indicating that the proposed approach is well suited for deployment in sensor networks and other resource-constrained environments.

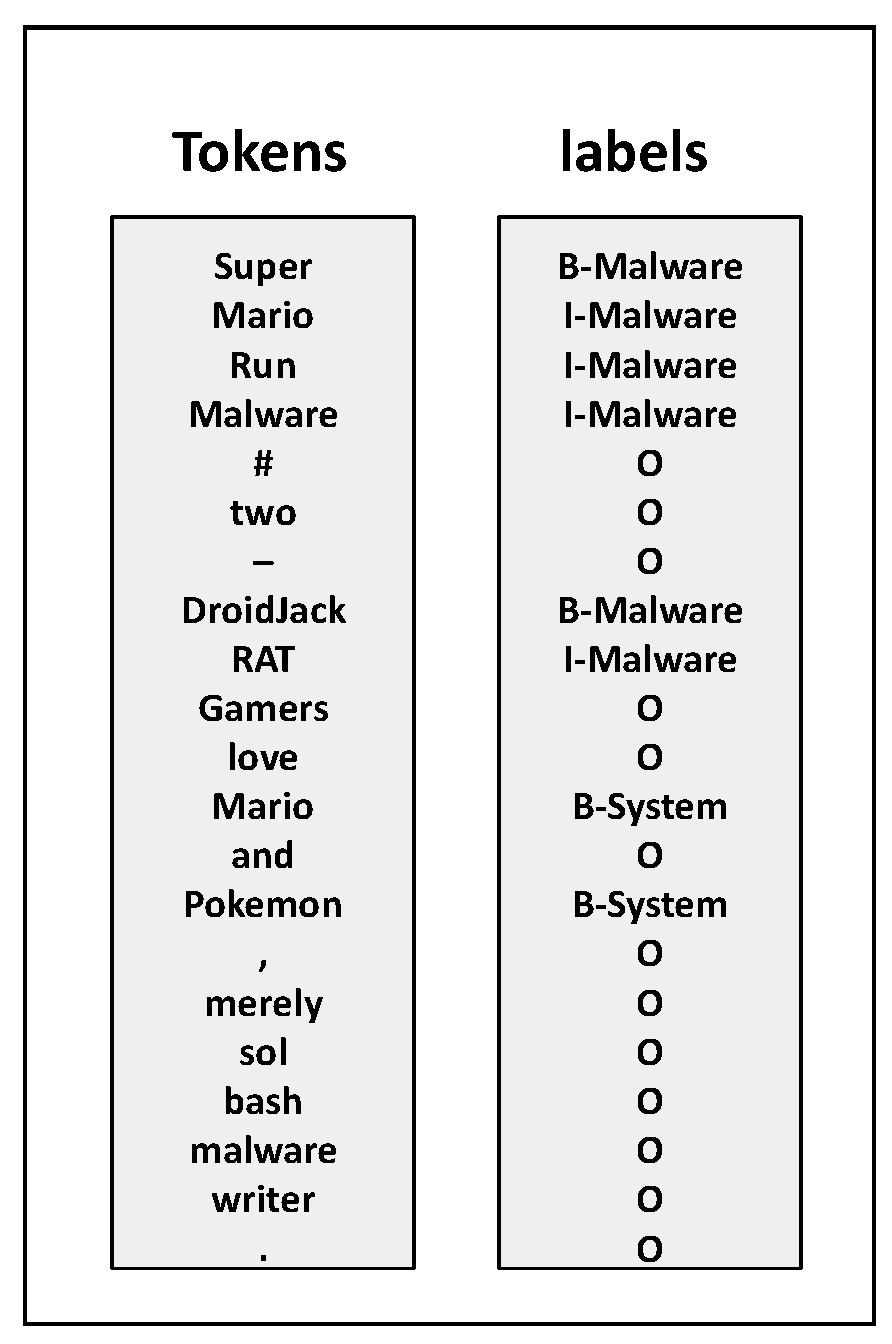

2. Materials and Methods

- “B” stands for the beginning of a named entity.

- “I” indicates the inside of a named entity.

- “O” denotes that a token is outside any named entity.

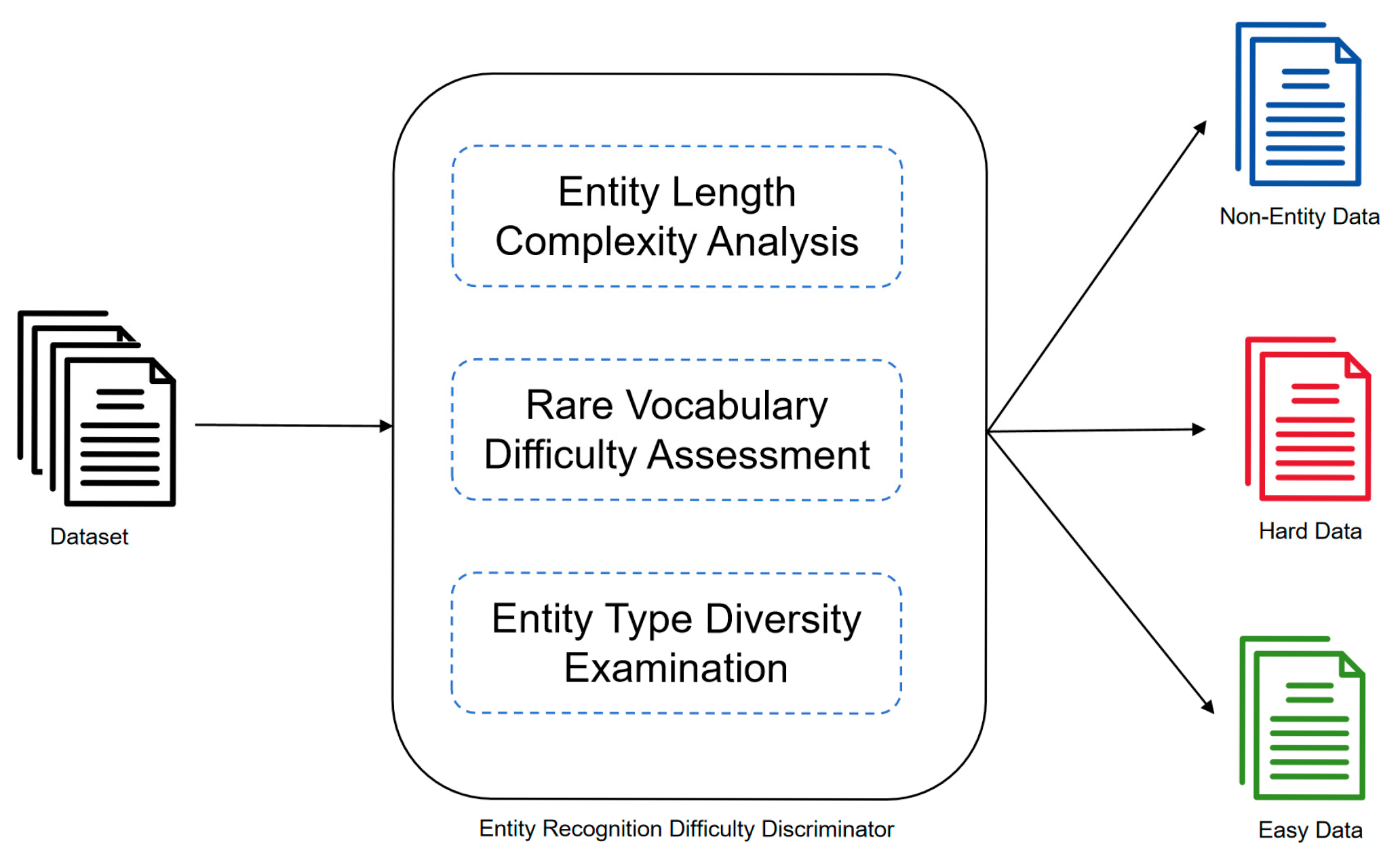

2.1. Rule-Based Discriminator

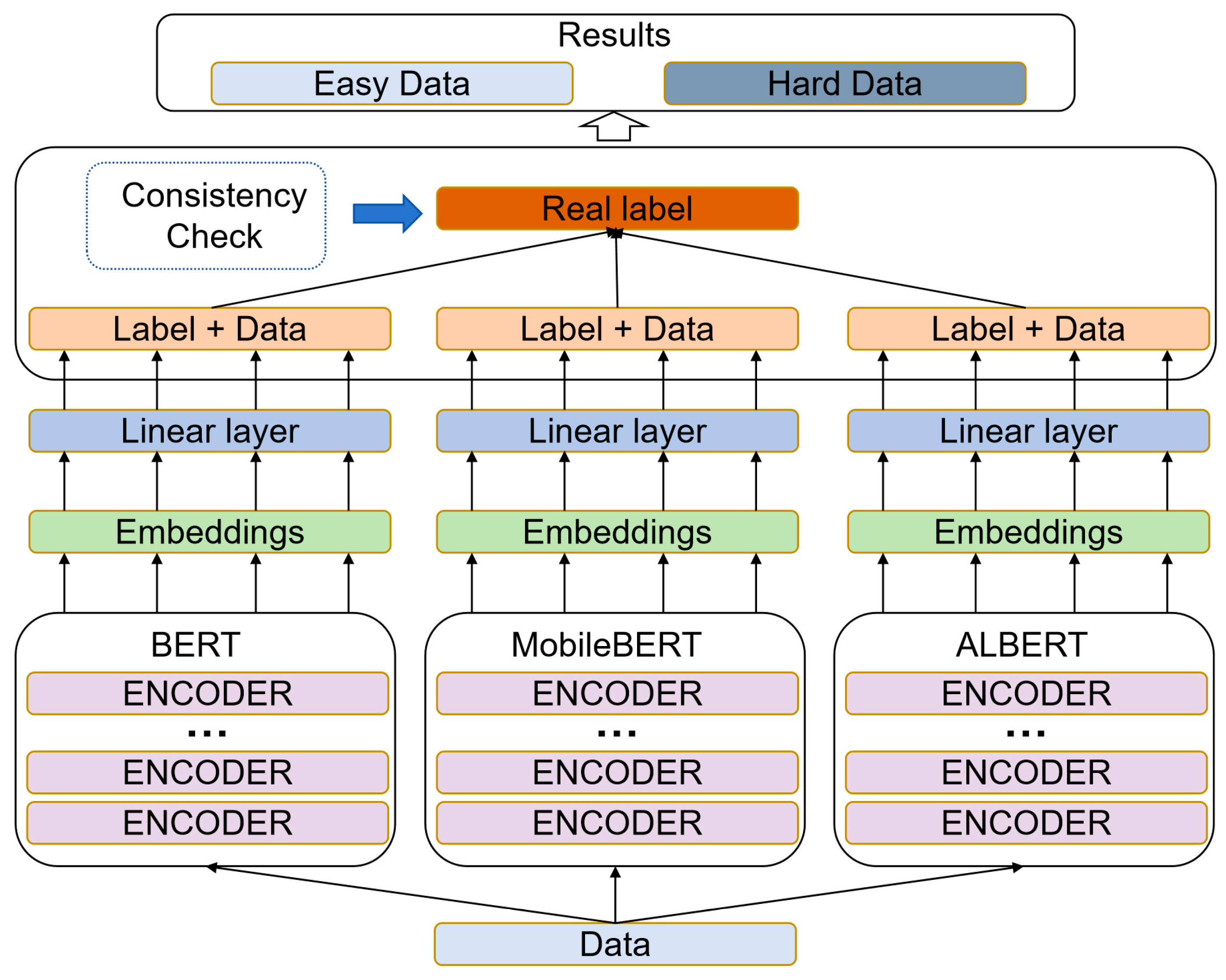

2.2. DL-Based Discriminator

2.3. Data Augmentation

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Settings

3.2. Impact of Hard and Easy Data on NER Performance in Training Sets

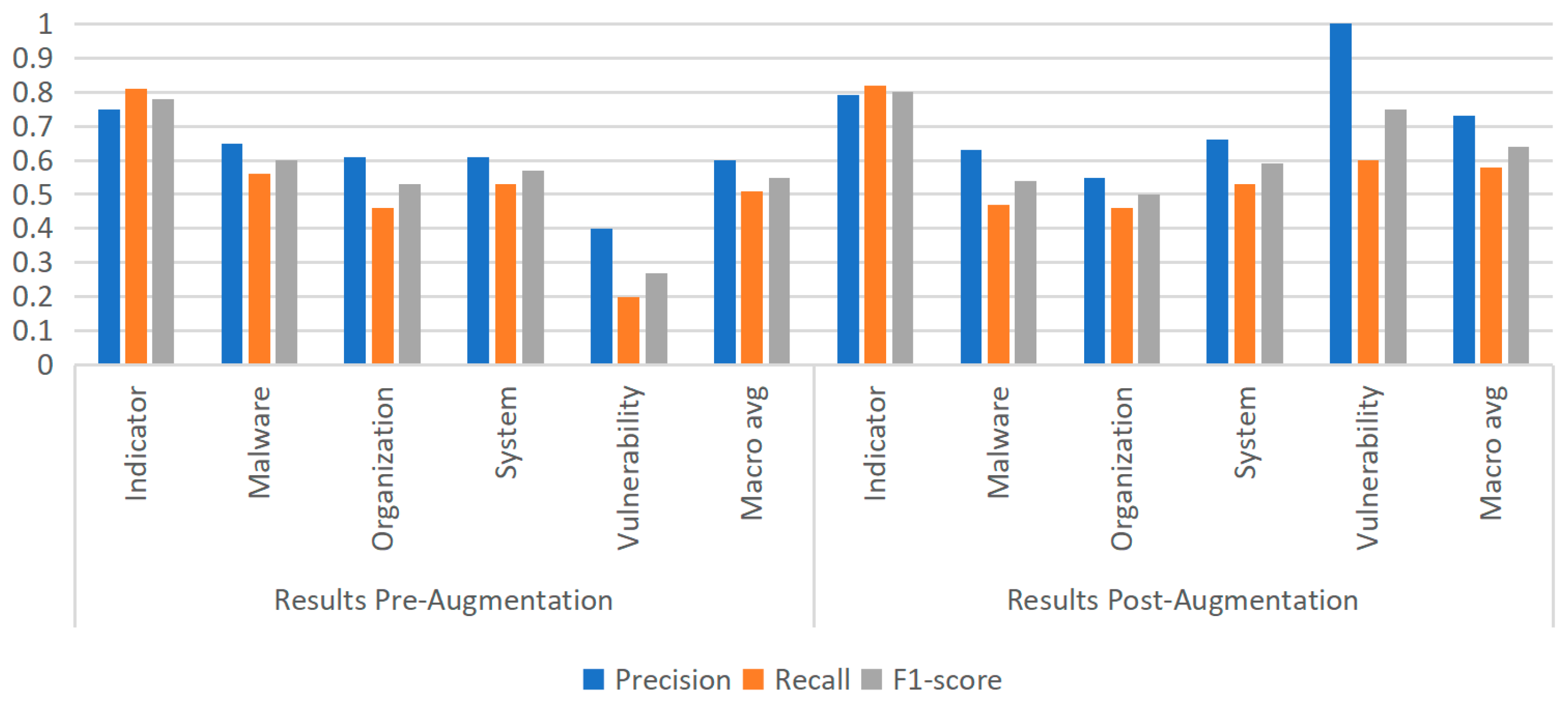

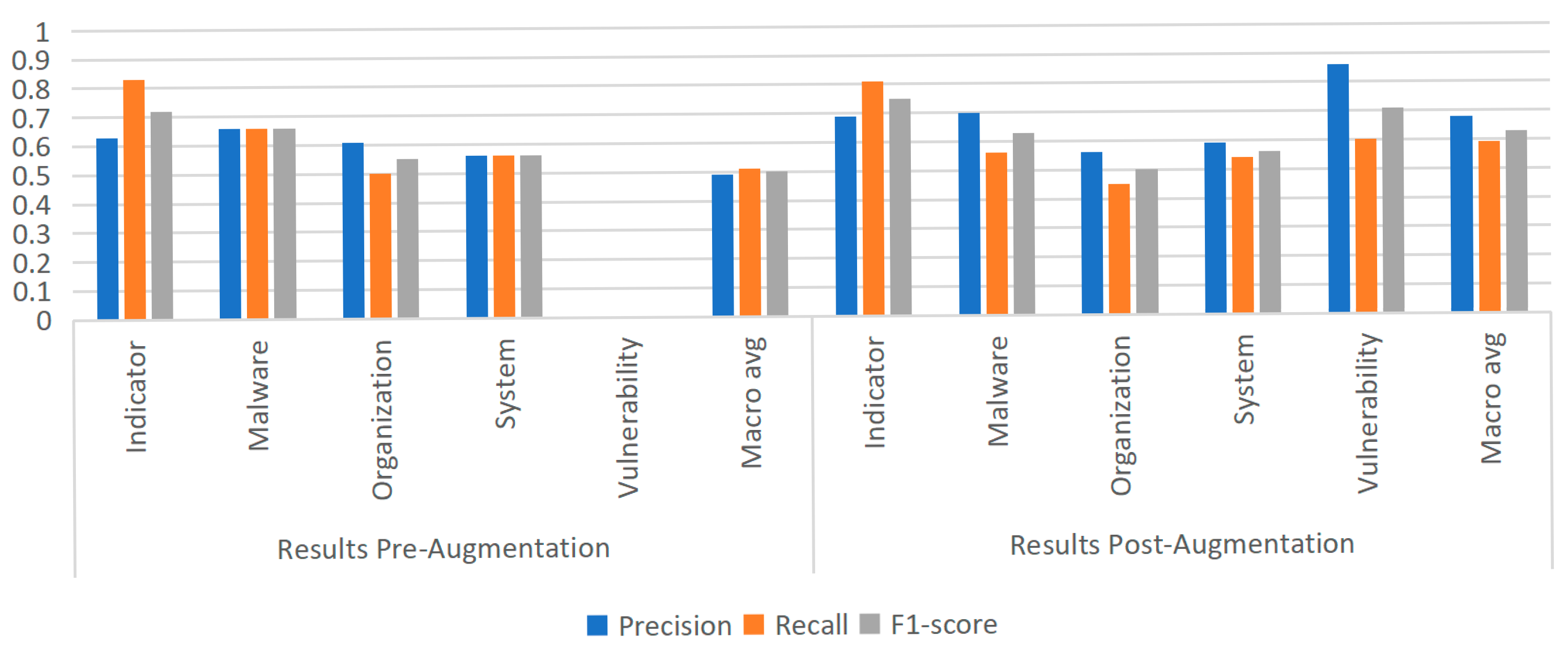

3.3. Ablation Study: Effect of Data Augmentation on Sparse Entity Types

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mondal, K.; Ebenezar, U.S.; Karthikeyan, L.; Senthilvel, P.G.; Preetham, B.S. Integrating NLP for Intelligent Cybersecurity Risk Detection from Bulletins. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computing for Sustainability and Intelligent Future (COMP-SIF), Bangalore, India, 21–22 March 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Le, Q.V. XLNet: Generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32, pp. 5753–5763. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Niu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, S.; Deng, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y. A Cybersecurity Entity Recognition Method for Enhancing Situation Awareness in Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th New Energy and Energy Storage System Control Summit Forum (NEESSC), Hohhot, China, 29–31 August 2024; pp. 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-training; Technical Report; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, W.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Han, X. Gat-Ti: Extracting Entities From Cyber Threat Intelligence Texts. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 6th International Seminar on Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Information Technology (AINIT), Shenzhen, China, 11–13 April 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Ding, M.; Jiang, J.; Xu, W.; Mo, X.; Tai, Y.; Zhang, J. Cyber Threat Intelligence Mining for Proactive Cybersecurity Defense: A Survey and New Perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1748–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Z. CSKG4APT: A Cybersecurity Knowledge Graph for Advanced Persistent Threat Organization Attribution. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 5695–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Gupta, G.P.; Tripathi, R.; Garg, S.; Hassan, M.M. DLTIF: Deep Learning-Driven Cyber Threat Intelligence Modeling and Identification Framework in IoT-Enabled Maritime Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Bhusal, D.; Park, Y.; Rastogi, N. Cyner: A python library for cybersecurity named entity recognition. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Chen, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. ALBERT: A Lite BERT for Self-supervised Learning of Language Representations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1909.11942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Shang, L.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q. TinyBERT: Distilling BERT for natural language understanding. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics Findings of ACL: EMNLP 2020, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 4163–4174. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Song, X.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D. MobileBERT: A Compact Task-Agnostic BERT for Resource-Limited Devices. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Dong, L.; Bao, H.; Yang, N.; Zhou, M. Minilm: Deep self-attention distillation for task-agnostic compression of pre-trained transformers. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5776–5788. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhan, D.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, B.; Du, X.; Tian, Z. Distributed machine learning for next-generation communication networks: A survey on privacy, fairness, efficiency, and trade-offs. Inf. Fusion 2025, 126, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, C.; Huang, H.; Zhan, D.; Qu, J. Hybrid Recommendation Algorithm for User Satisfaction-oriented Privacy Model. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2022, 16, 3419–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Debeyan, F.; Madeyski, L.; Hall, T.; Bowes, D. The impact of hard and easy negative training data on vulnerability prediction performance. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 211, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hou, Y.; Che, W. Data augmentation approaches in natural language processing: A survey. AI Open 2022, 3, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, C.; Huang, H.; Zhan, D.; Qu, J. Federation Boosting Tree for Originator Rights Protection. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 74, 4043–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: A lexical database for English. Commun. ACM 1995, 38, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhan, D.; Qu, J. Content Feature Extraction-based Hybrid Recommendation for Mobile Application Services. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 71, 6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yo, E. An Analytical Study of the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Formulae to Explain Their Robustness over Time. In Proceedings of the 38th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation, Tokyo, Japan, 7–9 December 2024; Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 989–997. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, R. Expectation-based syntactic comprehension. Cognition 2008, 106, 1126–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Qiu, W.; Chen, M.; Wang, R.; Huang, F. Boundary enhanced neural span classification for nested named entity recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 9016–9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M.; Mandera, P.; Keuleers, E. The word frequency effect in word processing: An updated review. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dou, S.; Xiong, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gui, T.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, X.-J. MINER: Improving out-of-vocabulary named entity recognition from an information theoretic perspective. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Volume 1, pp. 5590–5600. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Data and knowledge-driven named entity recognition for cyber security. Cybersecurity 2021, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejadgholi, I.; Fraser, K.C.; De Bruijn, B. Extensive error analysis and a learning-based evaluation of medical entity recognition systems to approximate user experience. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.05281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenetorp, P.; Pyysalo, S.; Topić, G.; Ohta, T.; Ananiadou, S.; Tsujii, J. Brat: A web-based tool for nlp-assisted text annotation. In Proceedings of the Demonstrations at the 13th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Avignon, France, 23–27 April 2012; pp. 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

| Entity Type | Entity Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | 1490 | 32.9% |

| Malware | 1199 | 26.4% |

| Organization | 508 | 11.2% |

| System | 1267 | 28.0% |

| Vulnerability | 67 | 1.5% |

| Model Name | Model Size (MB) | Parameter Count (Million) |

|---|---|---|

| BERT-base-uncase | 440 | 110 |

| AlBERT-base-v2 | 47 | 11 |

| MobileBERT-uncase | 147 | 25 |

| Model Name | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| BERT-base-uncase | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.66 |

| MobileBERT | 0.64 | 0.6 | 0.62 |

| ALBERT | 0.6 | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| Model Name | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| BERT-base-uncased | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| BERT-large-uncased | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| RoBERTa-base | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| RoBERTa-large | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ge, M. A Cybersecurity NER Method Based on Hard and Easy Labeled Training Data Discrimination. Sensors 2025, 25, 7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247627

Ye L, Wu Y, Zhang H, Ge M. A Cybersecurity NER Method Based on Hard and Easy Labeled Training Data Discrimination. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247627

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Lin, Yue Wu, Hongli Zhang, and Mengmeng Ge. 2025. "A Cybersecurity NER Method Based on Hard and Easy Labeled Training Data Discrimination" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247627

APA StyleYe, L., Wu, Y., Zhang, H., & Ge, M. (2025). A Cybersecurity NER Method Based on Hard and Easy Labeled Training Data Discrimination. Sensors, 25(24), 7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247627