Analysis of Wellbore Wall Deformation in Deep Vertical Wells Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

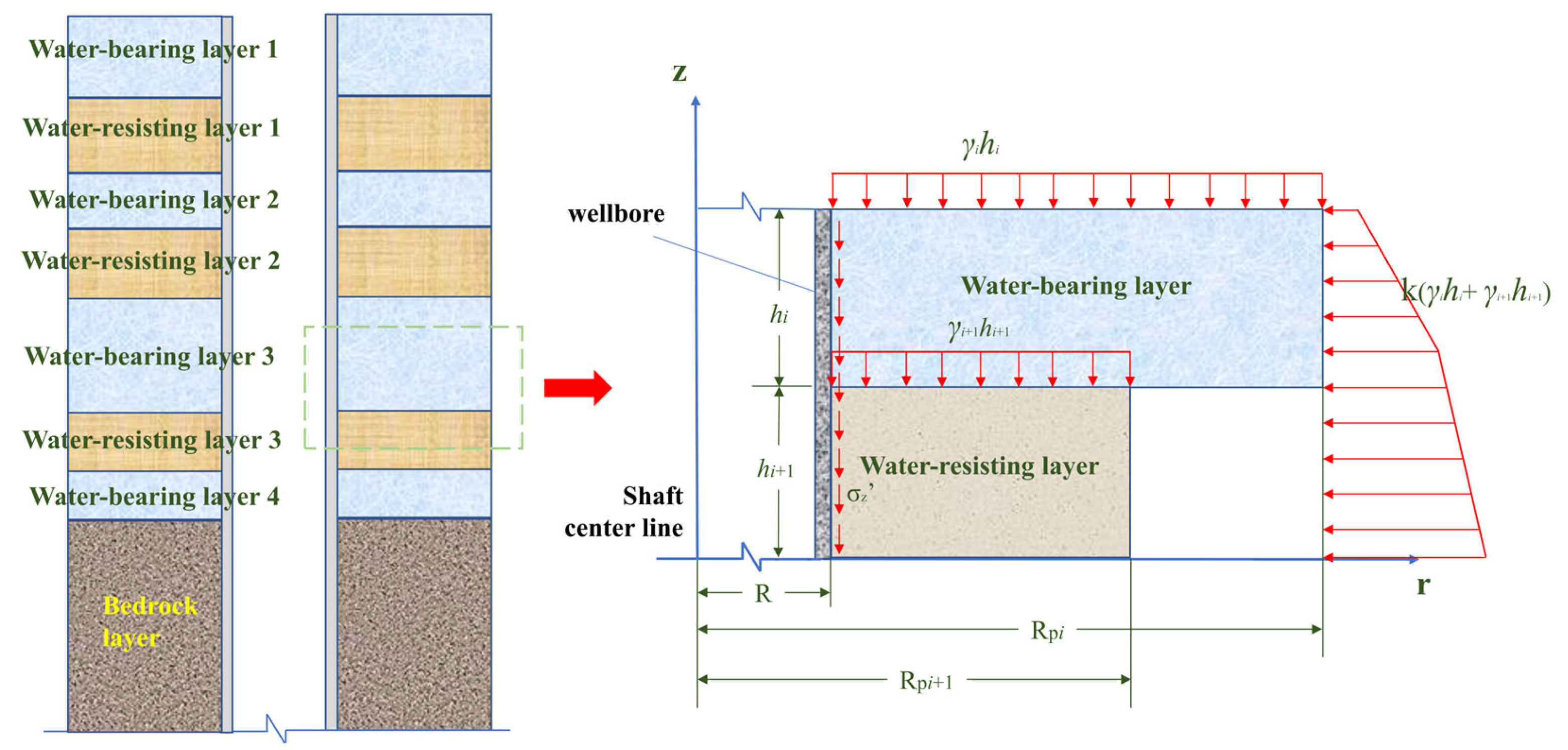

2. Analytical Solution of Wellbore Wall Stress

- (1)

- Both the soil layers and the concrete wellbore are assumed to be isotropic elastic bodies, in line with the basic principles of elastic mechanics.

- (2)

- The bedrock layer is assumed to possess high rigidity, and its settlement is considered negligible. Only the upper weathered bedrock layer and aquifer layer undergo vertical displacement.

- (3)

- The vertical additional forces on the wellbore wall are mainly the elastic vertical force and the plastic vertical force. The plastic zone may influence the upper part of the wellbore wall, resulting from the relative displacement between surface soil settlement and the wellbore wall, which generates shear forces exceeding the elastic shear strength limit [16]. In this study, FBG sensors are placed in the lower section of the wellbore, assuming that the entire wellbore exists within an elastic shear zone.

- (4)

- The monitoring scheme includes sensors arranged in the circumferential and vertical directions. Therefore, it is assumed that the radial deformation of the concrete wellbore wall can be disregarded, i.e., μr = 0.

- (5)

- The range of the soil’s influence on the wellbore wall is limited by a maximum influence radius Rpi [16], which is determined by the following Equation (1):where νi represents the Poisson’s ratio of each soil layer; l is the depth of the elastic segment of the wellbore, defined in this study as the distance from the upper edge of the wellbore to the corresponding soil layer.

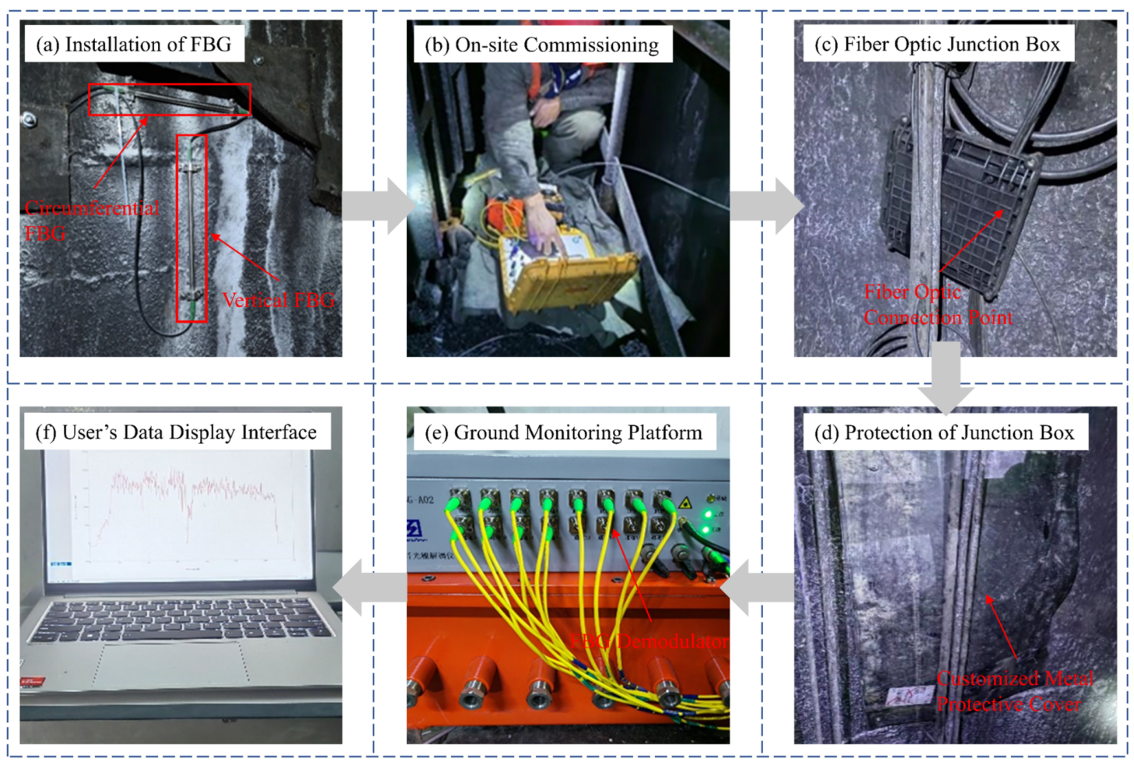

3. Layout of FBG Monitoring System

3.1. Principle of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing

3.2. Project Profile

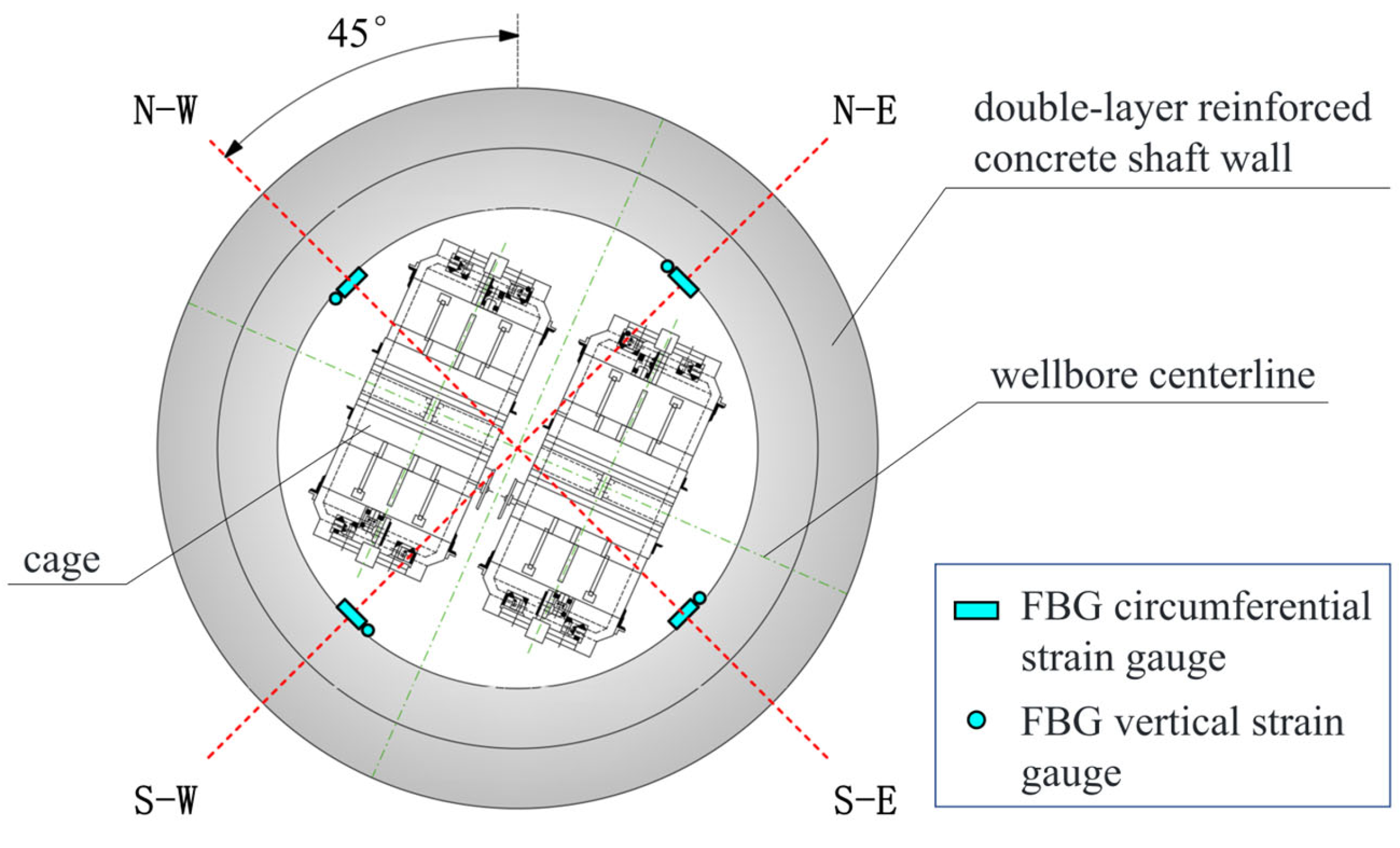

3.3. FBG Sensor Layout Scheme

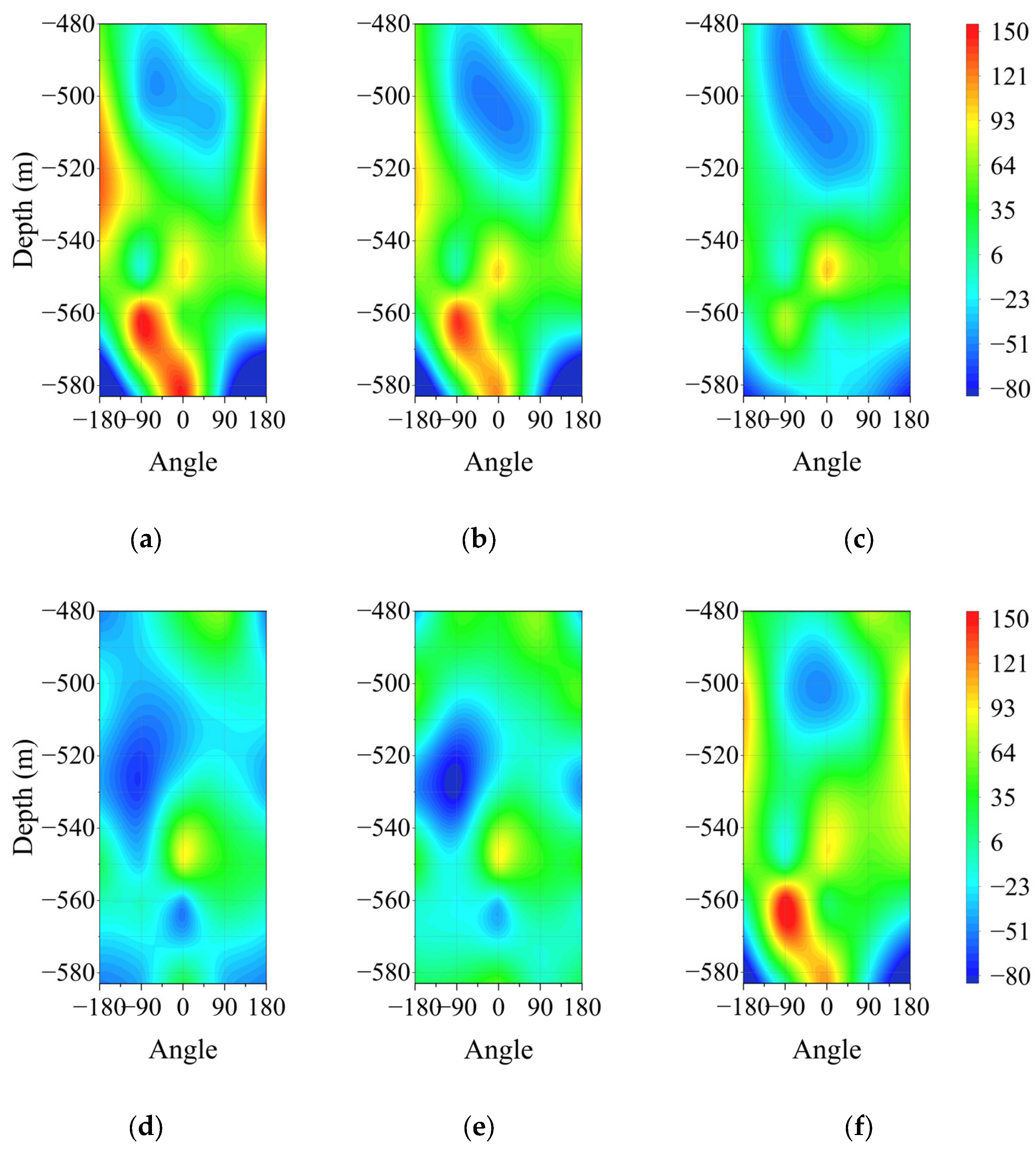

4. Analysis of Monitoring Results

4.1. Relationship Between Strain and Shaft Wall Depth

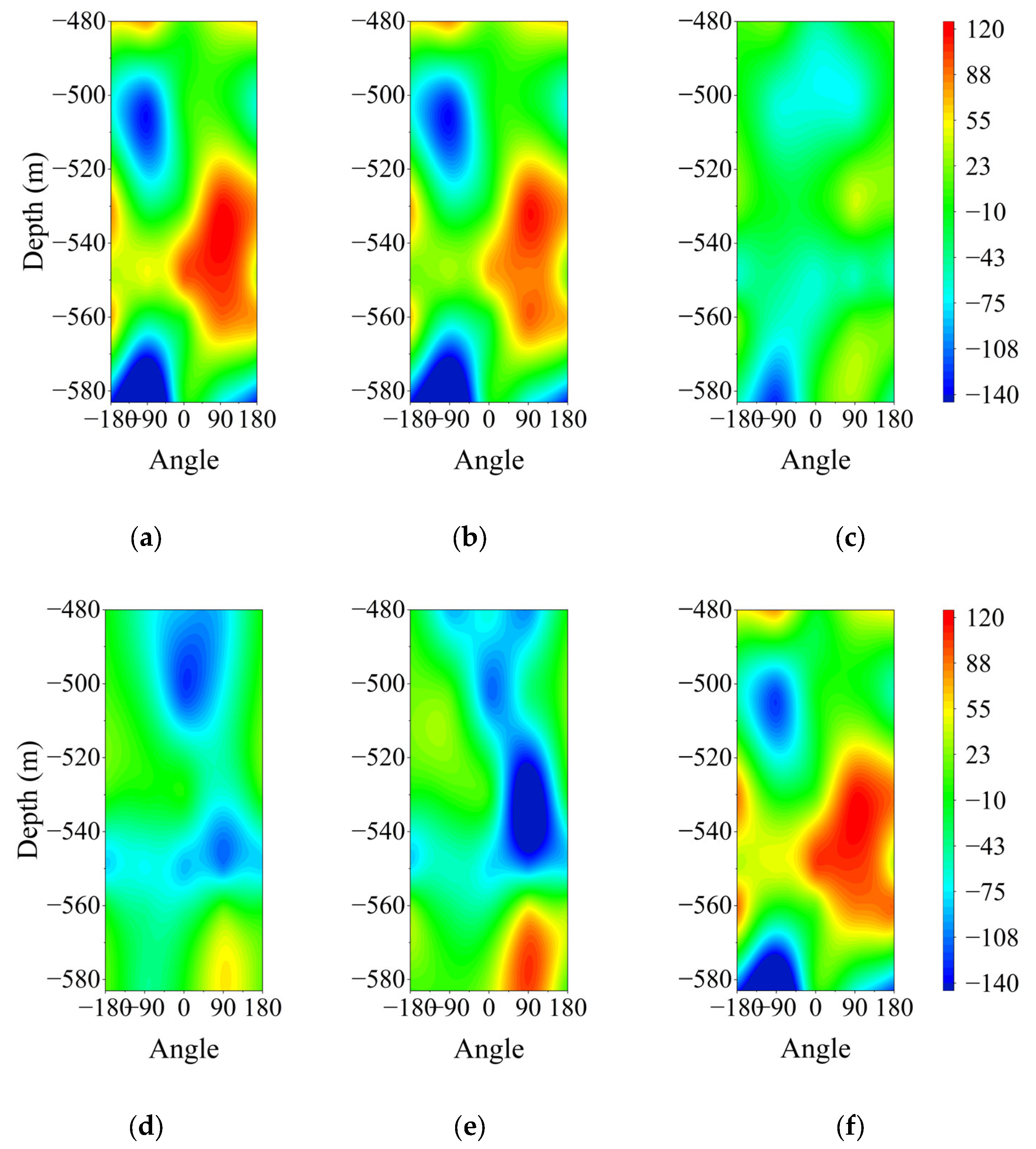

4.1.1. Variation Law of Circumferential Strain with Depth

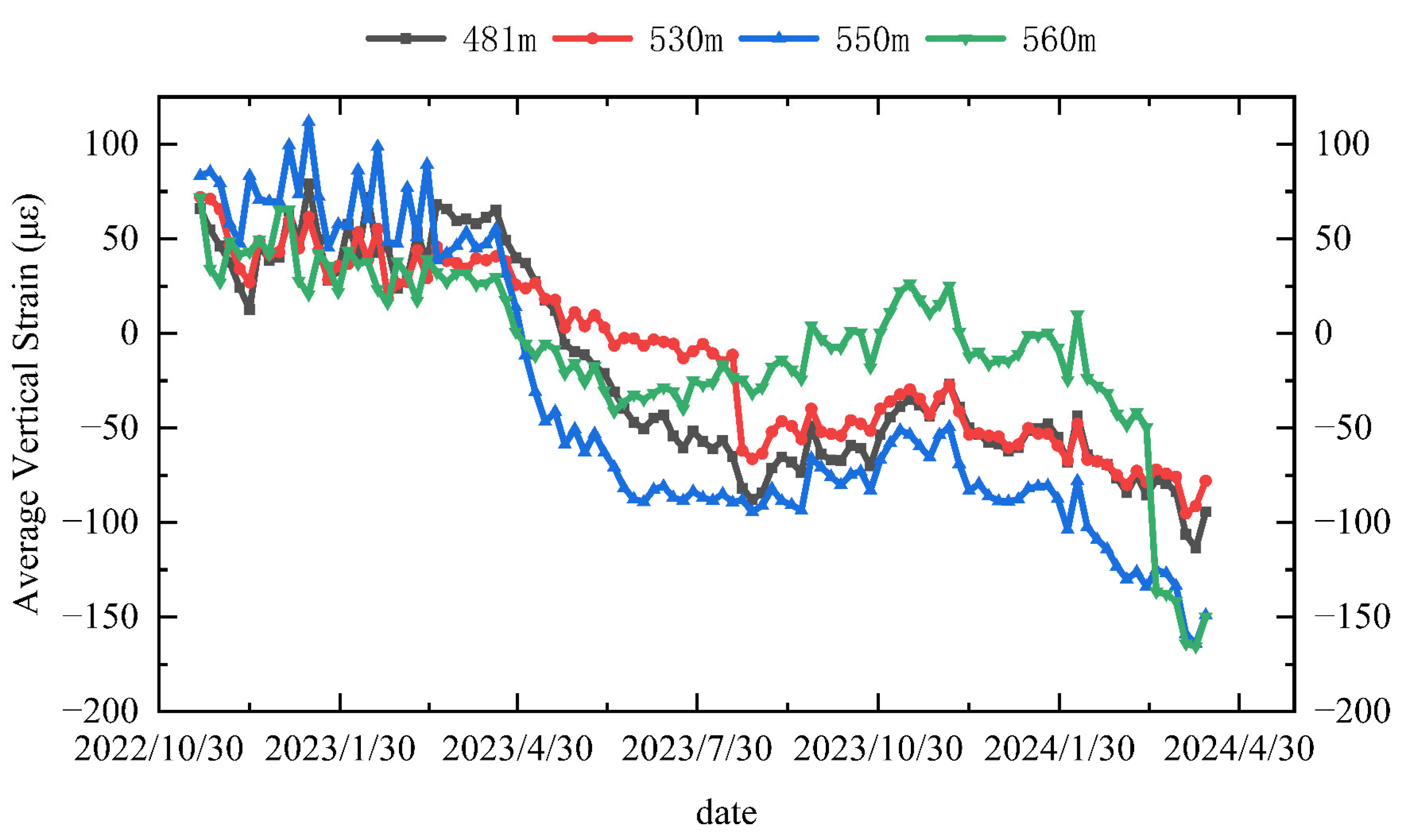

4.1.2. Variation Law of Vertical Strain with Depth

4.2. Relationship Between Strain and Date

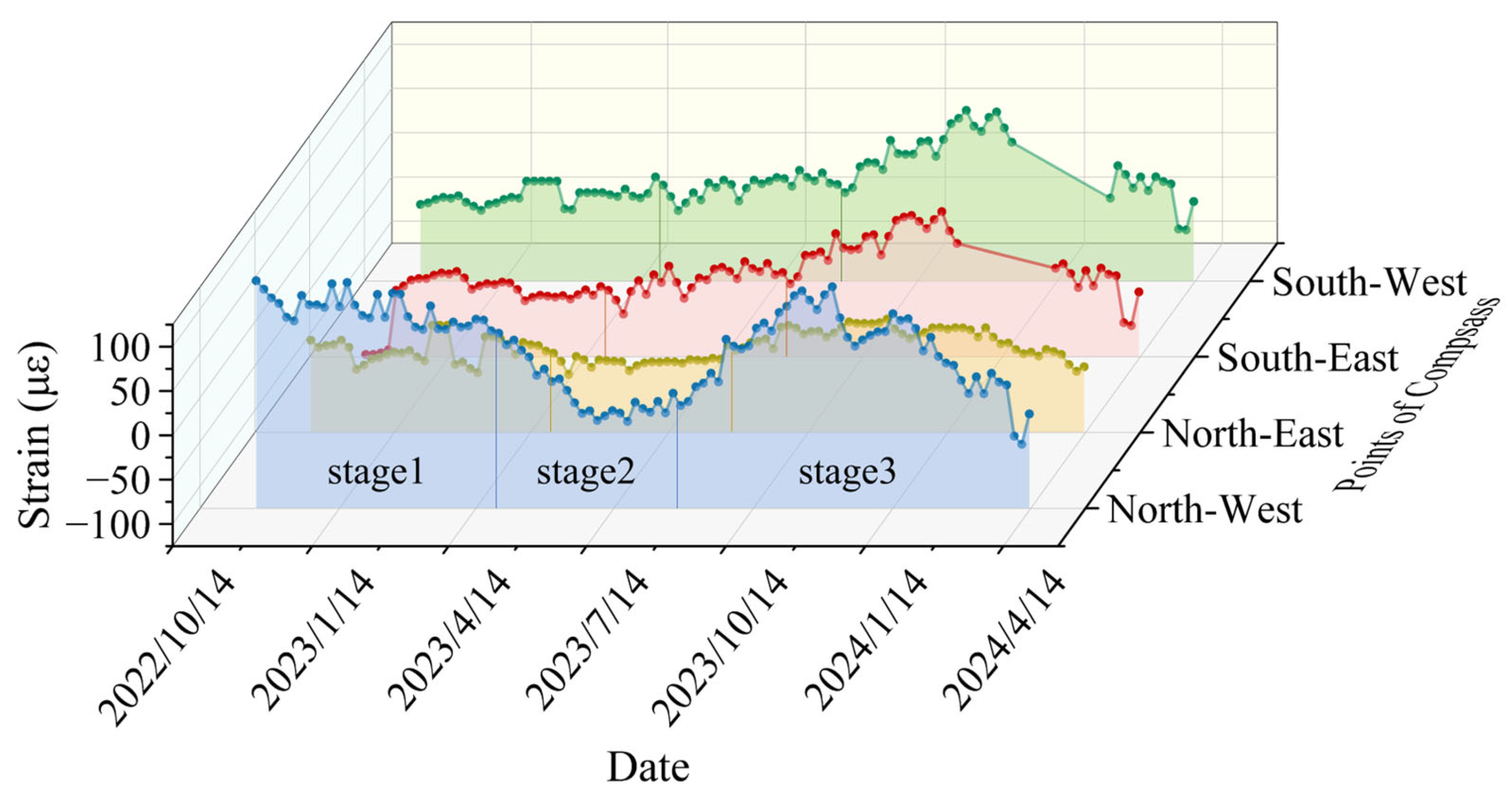

4.2.1. Variation Law of Circumferential Strain with Date

- (1)

- The region has a temperate monsoon climate, with January being the coldest month, averaging −1.8 °C. During winter, surface and some groundwater freeze, limiting effective aquifer recharge and minimizing the soil layer’s impact on the wellbore. This explains the minor strain changes during the first stage. Furthermore, if the surrounding soil is highly water-saturated, freezing causes volume expansion that exerts pressure on the wellbore, resulting in compressive strain. For instance, during this stage, the maximum compressive strain at the first monitoring level reaches −79.65 με.

- (2)

- The region experiences an average annual precipitation of 677.3 mm, primarily occurring in July and August, with a maximum daily rainfall of 223 mm. It also has an extensive network of artificial irrigation systems. During summer, abundant river flow replenishes groundwater, and some rainfall directly infiltrates the ground, leading to an increase in radial strain. The maximum strain at the first monitoring level during this period reaches 87.79 με. Higher summer temperatures, combined with increasing heat at greater depths, can cause concrete to expand and crack, further contributing to the rise in radial strain.

- (3)

- After September, rainfall decreases and temperatures drop, which reduces aquifer recharge. This water loss leads to soil compression and deformation, while the weathered bedrock weakens the supporting strength of the overlying loose soil. Consequently, soil deformation intensifies and affects the wellbore more significantly. On 30 November, the maximum tensile strain at the first monitoring level reaches 72.79 με.

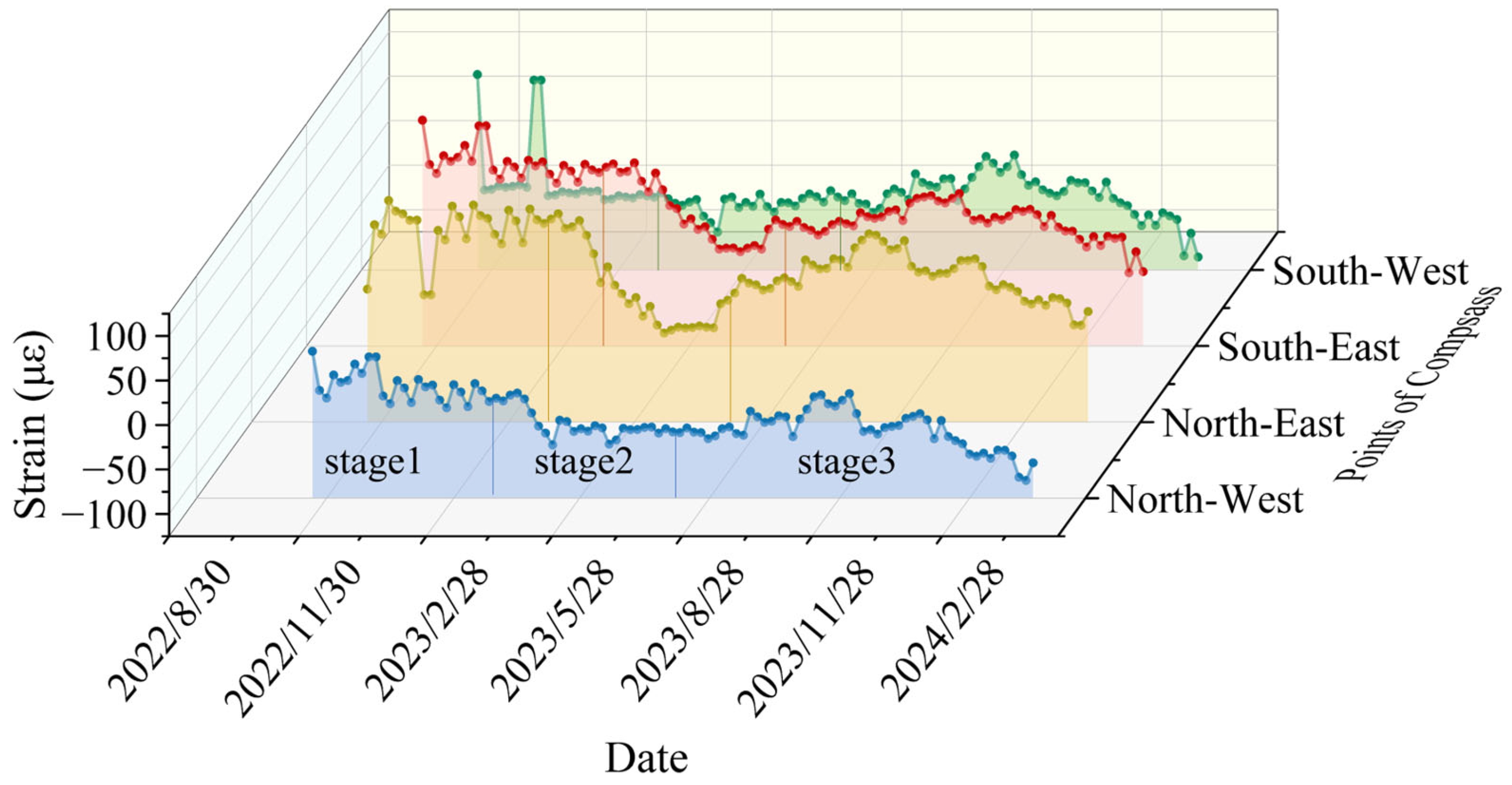

4.2.2. Variation Law of Vertical Strain with Date

4.3. Analytical Solution of Wellbore Wall Stress

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The monitoring system successfully captured the spatial characteristics of shaft wall deformation. Both circumferential and vertical strains exhibit pronounced spatial anisotropy, with deeper monitoring levels showing significantly larger compressive and tensile deformation. The site-specific mechanical model that incorporates the stratigraphy, dual-layer concrete lining, and influence radius provides a clear physical basis for interpreting these deformation patterns.

- (2)

- The temporal evolution of shaft wall strain is strongly influenced by groundwater variations and the consolidation of overlying strata. Quantitative analysis shows that strain increases progressively over time, consistent with the seasonal changes in groundwater recharge and subsequent drainage, demonstrating the importance of hydrogeological conditions in long-term deformation development.

- (3)

- The stresses inferred from the measured strains agree well with the analytical solution in both magnitude and depth-dependent trend. All stress values remain below the strength limits of the C70/C50 concrete lining and the allowable values specified by relevant standards, indicating that the shaft is currently in a safe stress state. These results also validate the effectiveness of the proposed monitoring–analysis framework for evaluating shaft deformation under complex hydrogeological conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chai, J.; Zhu, L.; Wei, S.; Li, Y.; Qiu, B.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z. Settlement deformation detecting in deep unconsolidated soil layer by fiber Bragg grating sensing technology. J. China Coal Soc. 2009, 34, 741–746. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Li, G.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, H.; Wang, J.; Li, P. Exploration and application of deep learning based wellbore deformation forecasting model. J. China Coal Soc. 2025, 50, 732–747. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Cheng, H. Analysis on additional forces of shaft with drainage of stratum. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2000, 19, 310–313. [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat, O.; Crosetto, M. Deformation measurement using terrestrial laser scanning data and least squares 3D surface matching. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2008, 63, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chai, J.; Chen, N. Shaft deformation monitoring based on fiber Bragg grating. Saf. Coal Mines 2017, 48, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Testing and theoretical studies on the interaction between soil and shaft wall during deep soil compression due to losing water. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2000, 22, 475–480. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, D.; Lu, H.; Xue, L.; Zhu, N. Elastic mechanics analysis of non-mining failure Criteria for shaft lining in Hengyuan coal mine. Saf. Coal Mines 2017, 48, 208–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.; Cao, G.; Yao, Z.; Rong, C.; Zhang, L. Tensile fracture mechanism of drilling shaft under the special engineering conditions of thick alluvium and thin bedrock. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Q.; Piao, C.; Cui, Y.; Yan, S.; Yu, B.; Qu, C. Remote real-time monitoring and early warning system for shaft wall deformation by fiber Bragg grating. Saf. Coal Mines 2023, 54, 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Wu, B.; Liu, H.; Tan, Z. The development of shaft monitoring and early warning system based on the technology of fiber Bragg grating. China Civ. Eng. J. 2015, 48, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; Yao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. Application of FBG Sensor to Safety Monitoring of Mine Shaft Lining Structure. Sensors 2022, 22, 4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Choudhary, S.; Chen, W.-B.; Wu, P.-C.; Kumar, M.; Rajput, A.; Borana, L. Applications of Fibre Bragg Grating Sensors for Monitoring Geotechnical Structures: A Comprehensive Review. Measurement 2023, 218, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Xie, F.; Yuan, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. Failure law of shaft lining in thick topsoil and fiber monitoring analysis. Saf. Coal Mines 2022, 53, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, Q.; Xu, F.; Chen, Z.; Liang, D. Real-time monitoring system for stability of shaft surrounding rock based on optical fiber technology. J. Shenyang Univ. Technol. 2013, 35, 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, S.; Fu, X.; Wu, R. Internal deformation characteristics and full section monitoring for extremely thick loose layers under mining conditions. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 628–644. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Jing, L.; Yang, R. Distribution rules of additional force and secondary ground pressure stress of shaft wall in seepage sedimentation. J. China Coal Soc. 2010, 35, 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, F.; Shi, Z.; Liang, M.; Song, Y. Research and Application of Multi-Mode Joint Monitoring System for Shaft Wall Deformation. Sensors 2022, 22, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Hu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Feng, D.; Cheng, C.; Zhou, Z. Application status and prospect of distributed optical fiber and fiber grating sensing technology in coal mine safety monitoring. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, Z.; Shi, B.; Zhu, H.; Li, G.; Zhang, P.; Wei, G. Research progress of DFOS in safety mining monitoring of mines. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 2923–2949. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Jing, L.; Yang, R. Analysis of shear force between surface soil and vertical shaft in mine. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2006, 25, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C.; Sun, X.; He, M.; Tao, Z. Application of FBG Sensing Technology for Real-Time Monitoring in High-Stress Tunnel Environments. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FBG Interrogator | Performance Parameters |

|---|---|

| Model | NZS-FBG-A02 |

| Number of channels | 8/16/32 |

| Wavelength range (nm) | 1527~1568 |

| Wavelength resolution (pm) | 1 |

| Repeatability (pm) | 3 |

| Demodulation rate (Hz) | 1 |

| Dynamic range (dB) | 35 |

| Optical interface type | FC/APC |

| Monitoring Layer | Depth (m) | Soil Properties | Layer Thickness (m) | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio ν | Unit Weight γ (kN/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 481 | Fine Sand | 22.7 | 25 | 0.32 | 20.0 |

| 2 | 503 | Clay | 26.6 | 14 | 0.29 | 18.9 |

| 3 | 530 | Medium Sand | 15.3 | 17 | 0.38 | 18.7 |

| 4 | 550 | Medium Sand | 12.5 | 25 | 0.33 | 18.7 |

| 5 | 560 | Coarse Sand | 6.7 | 35 | 0.30 | 18.8 |

| 6 | 583 | Coarse Sand | 18.4 | 48 | 0.25 | 18.2 |

| Layer | Depth (m) | Maximum Circumferential Strain (με) | Minimum Circumferential Strain (με) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 481 | 74.68 | −51.50 |

| 2 | 503 | 109.43 | −55.03 |

| 3 | 530 | 127.51 | −68.46 |

| 4 | 550 | 100.82 | −41.84 |

| 5 | 560 | 180.45 | −44.48 |

| 6 | 583 | 148.52 | −98.97 |

| Layer | Depth (m) | Maximum Circumferential Strain (με) | Minimum Circumferential Strain (με) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 481 | 89.10 | −102.18 |

| 2 | 503 | 18.61 | −133.29 |

| 3 | 530 | 146.22 | −191.06 |

| 4 | 550 | 120.96 | −103.98 |

| 5 | 560 | 95.18 | −50.01 |

| 6 | 583 | 102.25 | −263.63 |

| Monitoring Layer | Layer Thickness (m) | Influence Radius Rp (m) | Undetermined Coefficient Ai (10−9) | Vertical Additional Stress σz’ (kPa) | Circumferential Strain σθ (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.7 | 171.19 | 10.2 | 4.09 | −16.52 |

| 2 | 26.6 | 188.19 | 18.0 | 10.71 | −17.28 |

| 3 | 15.3 | 169.07 | 5.06 | 15.81 | −18.21 |

| 4 | 12.5 | 186.90 | 1.81 | 16.12 | −18.90 |

| 5 | 6.7 | 197.61 | 0.32 | 20.16 | −19.24 |

| 6 | 18.4 | 218.63 | 1.96 | 38.19 | −20.03 |

| Monitoring Layer | Vertical Additional Stress σz′ (kPa) | Circumferential Strain σθ (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Value | Measured Value | Theoretical Value | Measured Value | |

| 1 | 4.09 | 7.52 | −16.52 | −20.32 |

| 2 | 10.71 | 14.28 | −17.28 | −22.57 |

| 3 | 15.81 | 17.17 | −18.21 | −22.95 |

| 4 | 16.12 | 20.43 | −18.90 | −24.13 |

| 5 | 20.16 | 25.86 | −19.24 | −24.88 |

| 6 | 38.19 | 30.26 | −20.03 | −26.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, W.; Cai, H.; Yang, L.; Li, Z. Analysis of Wellbore Wall Deformation in Deep Vertical Wells Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Technology. Sensors 2025, 25, 7626. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247626

Huang W, Cai H, Yang L, Li Z. Analysis of Wellbore Wall Deformation in Deep Vertical Wells Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Technology. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7626. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247626

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Wenchang, Haibing Cai, Longfei Yang, and Zixiang Li. 2025. "Analysis of Wellbore Wall Deformation in Deep Vertical Wells Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Technology" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7626. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247626

APA StyleHuang, W., Cai, H., Yang, L., & Li, Z. (2025). Analysis of Wellbore Wall Deformation in Deep Vertical Wells Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Technology. Sensors, 25(24), 7626. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247626