1. Introduction

Fifth-generation (5G) wireless communication systems are designed to deliver high-speed data transmission, ultra-low latency, and massive connectivity [

1]. 5G communication uses various frequency bands, including the sub-6 GHz and millimeter-wave (mmWave) bands, which enable significantly higher data rates than traditional cellular frequencies. This capability supports various applications, including enhanced mobile broadband, healthcare, Internet of Things (IoT), autonomous vehicles, and high-definition video streaming for augmented and virtual reality interactions [

2]. However, challenges in 5G mmWave communications include significantly higher free-space path loss and being more susceptible to attenuation from obstacles and atmospheric conditions [

1].

Antennas are crucial in 5G systems as they are designed to support increased bandwidth requirements, facilitating rapid data exchange and enabling the simultaneous connection of multiple devices. However, these antennas would work within shorter communication ranges and be more susceptible to obstacles, such as buildings and trees. To address the challenges of 5G networks, advanced techniques such as beamforming with high-gain arrays and MIMO (Multiple-Input Multiple-Output) are employed [

3]. Beamforming using antenna arrays directs the signal in specific directions, thereby enhancing coverage and signal strength. High-gain antennas are employed to focus the radiated energy into a narrower beam, thereby increasing the signal strength over longer distances and improving the signal-to-noise ratio. Antenna arrays are designed to achieve such high-gain radiation by optimizing the feeding network, which ensures precise phase and amplitude distribution across their elements. MIMO technology represents a significant advancement in data transmission and reception for modern wireless communication standards like LTE, Wi-Fi, and 5G. By utilizing multiple antennas at both the transmitter and receiver ends, MIMO systems exploit spatial diversity and multipath propagation [

4]. This leads to substantial improvements in data throughput, reliability, and spectral efficiency compared to traditional single-input, single-output (SISO) systems [

5]. These enhancements enable higher data rates, improved coverage, and better user experiences in dense urban environments and challenging propagation conditions.

In this paper, a low-profile wideband circularly polarized (CP) magneto-electric dipole (MED) antenna is proposed and implemented for a and MIMO systems, and an sequential array for mmWave 5G communications. The shape and dimensions of the CP-MED antenna are optimized to achieve a wideband CP radiation over the operating bandwidth. Next, the arrangements of two and four individual antenna elements in the MIMO system are investigated to achieve the best performance. Finally, high-gain radiation is achieved by designing a , , and MED sequential array for wideband CP communications, resulting in enhanced performance.

The following sections give a brief literature review of MED antennas and configurations in MIMO systems. This is followed by

Section 2, where the design methodology of a novel MED antenna is shown along with the simulation, equivalent circuit, and implementation results. In

Section 3, a numerical investigation is carried out to design an MIMO antenna system. This is followed by a MIMO diversity performance analysis in

Section 4. Next, the radiation characteristics of a high-gain sequential MED array are investigated in

Section 5. The paper is concluded in

Section 6.

1.1. Magneto-Dipole Antennas

A MED antenna combines the properties of both electric dipole and magnetic dipole antennas to achieve broad bandwidth, stable radiation patterns with low cross-polarization levels, and improved efficiency [

6]. It consists of an electric dipole component, a magnetic dipole component, and a proximity-coupled feeder. MED antennas are ideal for wireless communication systems, radar, and satellite systems applications. In [

7], a low-profile, dual-polarization MED antenna with dual orthogonal polarization and 36.8% bandwidth was proposed and investigated for 5G applications. CP antennas are preferred in wireless communication systems because they reduce polarization mismatch losses, enhance signal reliability, and improve quality [

8]. They offer consistent and reliable performance in changing environments. Further, in [

9], a compact CP-MED antenna with a 24.6% impedance matching bandwidth, 18.1% CP bandwidth, and a peak gain of 8 dBi. Another MED antenna based on substrate-integrated waveguide (SIW) technology featuring an aperture-coupled feeder with a CP bandwidth of 12.8% was also developed in [

10].

1.2. MIMO Configurations

MIMO-CP antennas are preferred in communication systems as they are particularly effective in improving signal quality and reliability, especially in scenarios where the orientation of transmitting and receiving devices varies. Additionally, MIMO-CP systems achieve higher data rates and better link reliability through spatial multiplexing and diversity techniques [

11]. Despite the benefits of MIMO systems, the performance of closely spaced antenna elements in such systems can be influenced by the elements’ proximity and electromagnetic interactions [

12]. Mutual coupling affects the system’s diversity gain, overall capacity, and the effective number of independent channels available for data transmission. Various techniques are employed to mitigate the mutual coupling effect in MIMO systems.

An example of such techniques is the incorporation of decoupling structures between elements [

12]. These decoupling structures include defected ground structures (DGS), parasitic elements, metamaterials, or orthogonal polarizations. In [

13], a planar MIMO-CP patch antenna with high isolation (

dB) using F-shaped DGS has been proposed. Furthermore, in [

14], four parasitic elements were inserted between two MIMO-CP diagonal slotted patches to improve isolation (

dB) and to achieve a gain of

dBi. Another method to reduce mutual coupling effects is the polarization diversity technique, which uses different polarization orientations for the MIMO elements. This includes using elements with orthogonal polarizations, which involves orienting antennas in different polarization planes, reducing the coupling effect as the antennas receive and transmit signals in different polarizations. For instance, in [

15], a two-port microstrip MIMO-CP array designed for WLAN applications achieved an impedance bandwidth ranging from

to

GHz, an axial ratio of less than 3 dB from

to

GHz, and high isolation of 37 dB.

Furthermore, MIMO systems utilizing decoupling structures and polarization diversity have been reported. For example, in [

16], a planar dual-port MIMO antenna array with left-hand circular polarization (LHCP) and right-hand circular polarization (RHCP) features has been reported for 5G sub-6 GHz applications. Here, an optimized Z-shaped slot-loaded DGS was designed to achieve high isolation and enhanced MIMO performance parameters, including an envelope correlation coefficient (ECC) less than

and a diversity gain (DG) of approximately

dB, with a mean effective gain (MEG) less than 3 dB. Another example is presented in [

17], where a polarization-reconfigurable MIMO antenna array was designed using a diagonal slotted cylindrical patch integrated with PIN diodes and a T-shaped power divider. Here, a sinusoidal-like DGS etched in the ground provided port isolation of 30 dB over the operating band. The MIMO array covered the

–

GHz band and achieved a peak gain of

dBi with switchable linearly polarized (LP) and CP states.

2. MED Antenna: Design Methodology

This section discusses the design methodology for a novel wideband circularly polarized MED antenna. The antenna is designed, simulated, and optimized using ANSYS HFSS (Latest version 2025). The results from ANSYS HFSS [

18] are then verified by simulating the optimized antenna using CST Microwave Studio (CST-MWS) [

19]. A lumped-element equivalent circuit (EC) is developed using particle swarm optimization for the optimum MED antenna. Next, the final antenna is fabricated, and the measurements are compared against the simulation and EC results.

2.1. Antenna Design Procedure

The MED antenna consists of three primary components: the electric dipole, the magnetic dipole, and the feeding element. The electric dipole consists of a pair of metal strips in a staircase design and a pair of rectangular strips with trimmed corners along the main diagonals. This configuration is introduced to excite two orthogonal degenerate modes (

and

equivalents) with equal amplitude and a

phase difference, which is essential for generating CP radiation. Furthermore, four groups of shorted-via holes are used to implement the magnetic dipole part. In addition, the feeding element consists of an L-shaped probe connected to a 50

SMA connector, which feeds the structure. The antenna was printed on a grounded Rogers 5880 substrate with a dielectric constant of 2.2, a loss tangent of 0.009, and a thickness of 1.5 mm. The final antenna geometry is shown in

Figure 1.

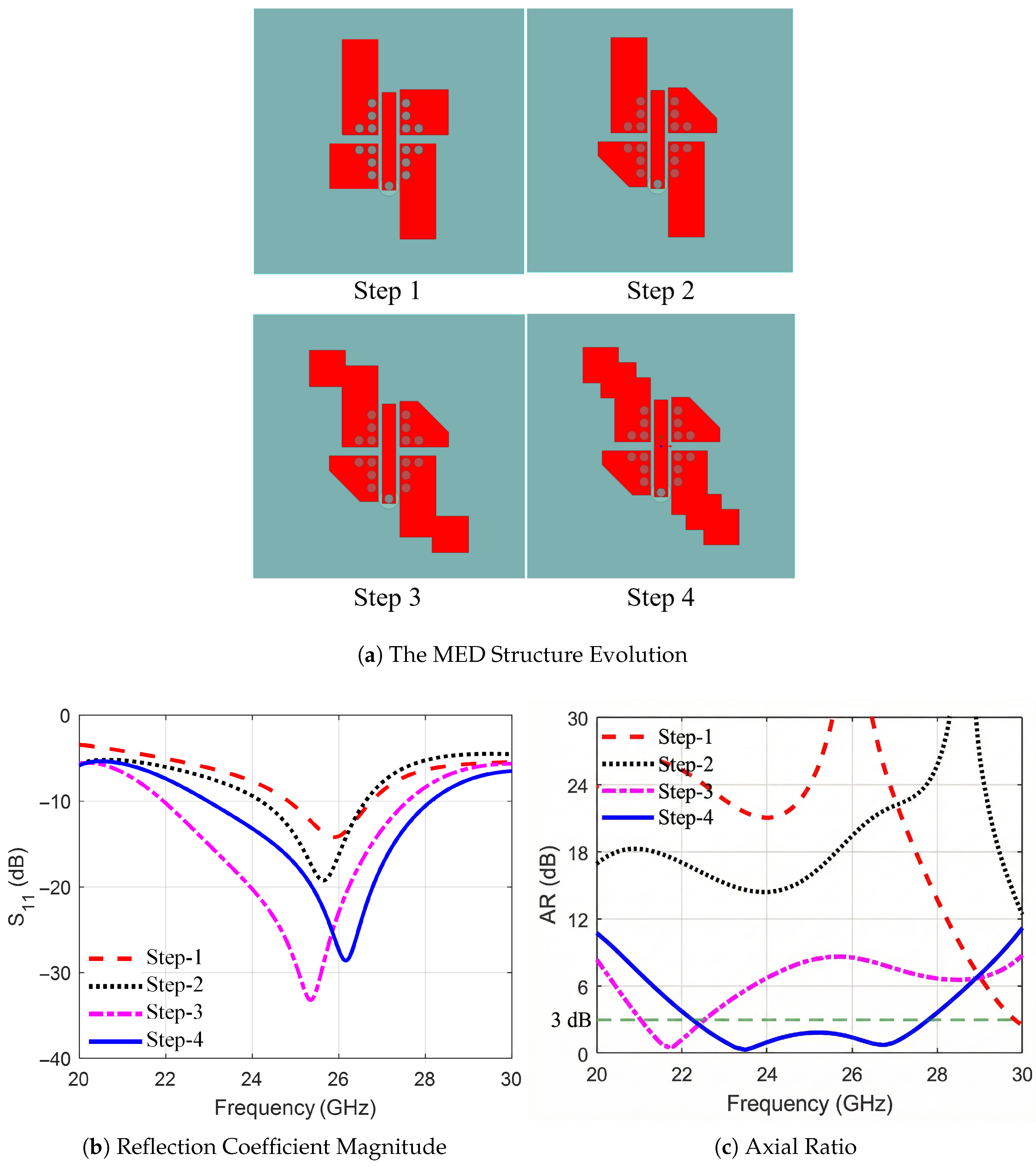

The antenna was designed in two stages. First, the MED antenna structure was obtained by following four steps, which are shown in

Figure 2a. The objectives of this stage were: (1) The reflection coefficient magnitude

should be less than −10 dB to achieve a wide-impedance matching bandwidth; (2) the axial ratio

should be less than 3 dB to achieve wideband CP radiation; and finally, (3) the bandwidths for

dB and

dB must coincide to achieve a wideband performance in both impedance matching and CP. The antenna characteristics at different design evolution steps are shown in

Figure 2b,c. In the second stage, a parametric study was carried out to investigate the effect of the different design dimensions,

,

,

,

,

, and

on

and AR bandwidths; the results of this study are shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The steps of the first stage are summarized as follows. In Step 1, two rectangular strips with shorted-via holes are designed to achieve asymmetrical displacement, resulting in a

GHz

bandwidth with LP radiation (AR 20–30 dB). Next, in Step 2, small rectangular strips with trimmed corners are utilized to broaden the

bandwidth to

GHz, with LP (AR 16–30 dB) and a CP (AR 3 dB) at 30 GHz. In Step 3 (single staircase), the step perturbs the current paths, shifting the resonance to lower frequencies and initiating CP from 21 GHz to 22.5 GHz by creating quadrature phase excitation.

Finally, the additional staircase in Step 4 further equalizes mode amplitudes, extending CP bandwidth to GHz (– GHz) by reducing AR sensitivity to frequency variations. The trimmed corners reduce cross-polarization by symmetrizing currents, while staircases create capacitive loading for quadrature modes, thereby broadening the AR bandwidth. This approach, unlike uniform patches, minimizes cross-polarization (≤−20 dB) and enhances CP bandwidth without increasing size.

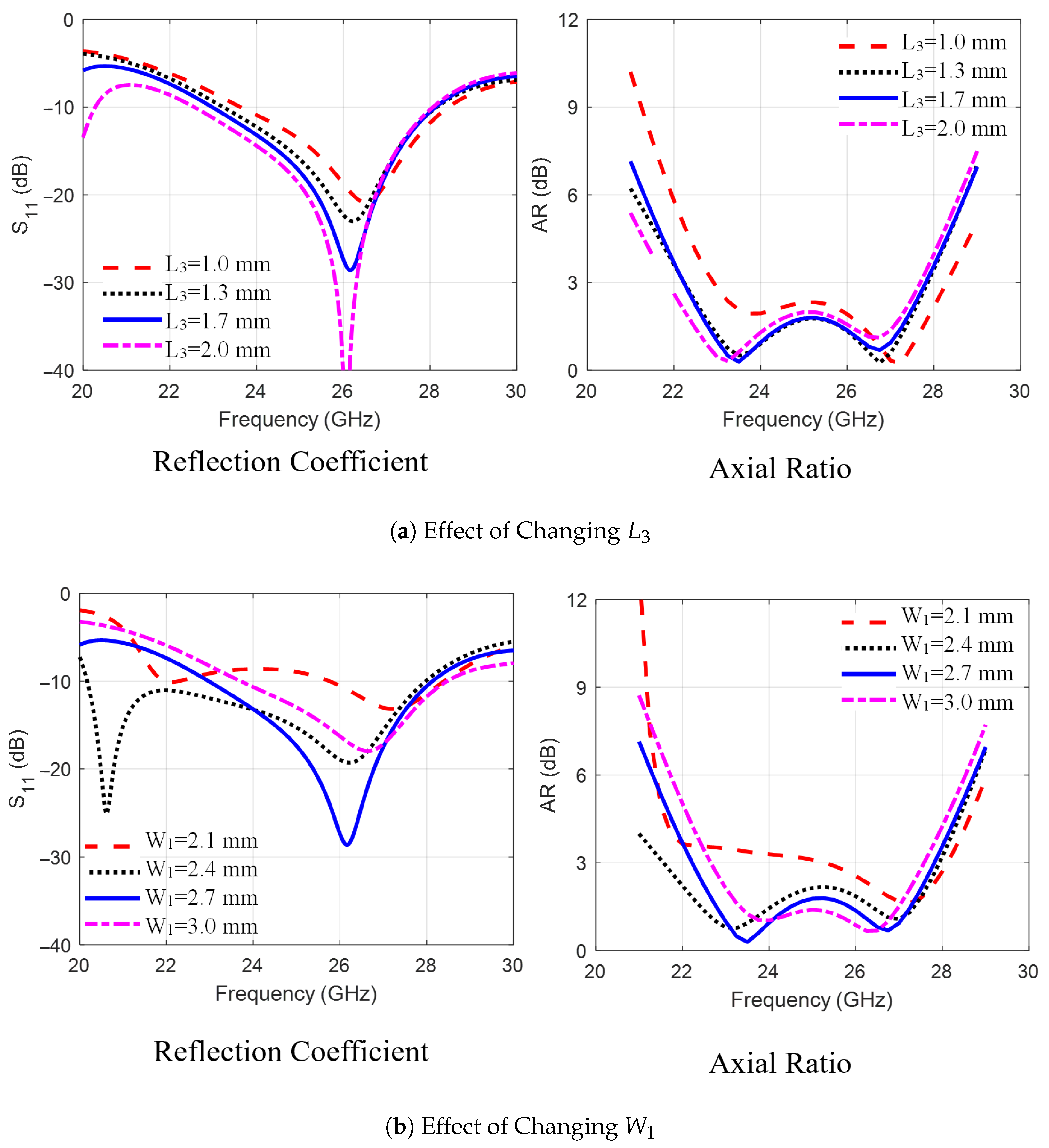

The findings of the parametric study performed in the second stage are summarized next. As shown in

Figure 3a, increasing the trimmed corner length

from 1 mm to 2 mm increased the bandwidths of

and AR by decreasing the lower frequency of the operating band. Next, as shown in

Figure 3b, increasing the arm width

at the trimmed corners from 2.1 mm to 3 mm impacts the matching and AR values in the frequency band, with the best results achieved at 2.7 mm. Next,

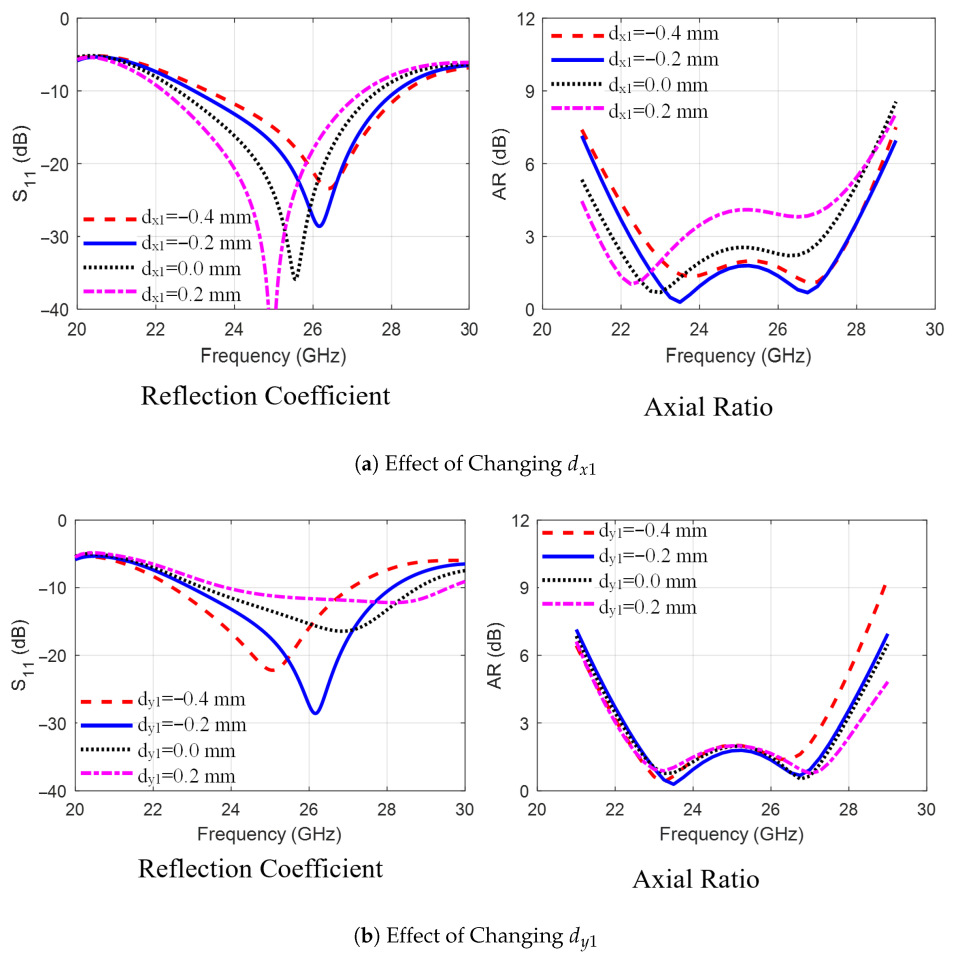

Figure 4a,b show the effect of shifting the staircase step positions relative to the patch corner,

and

, from −0.4 mm to 0.2 mm. It is observed that

affects the lower frequency limit while

shifts the upper limit of the operating band, with optimal values seen at

mm.

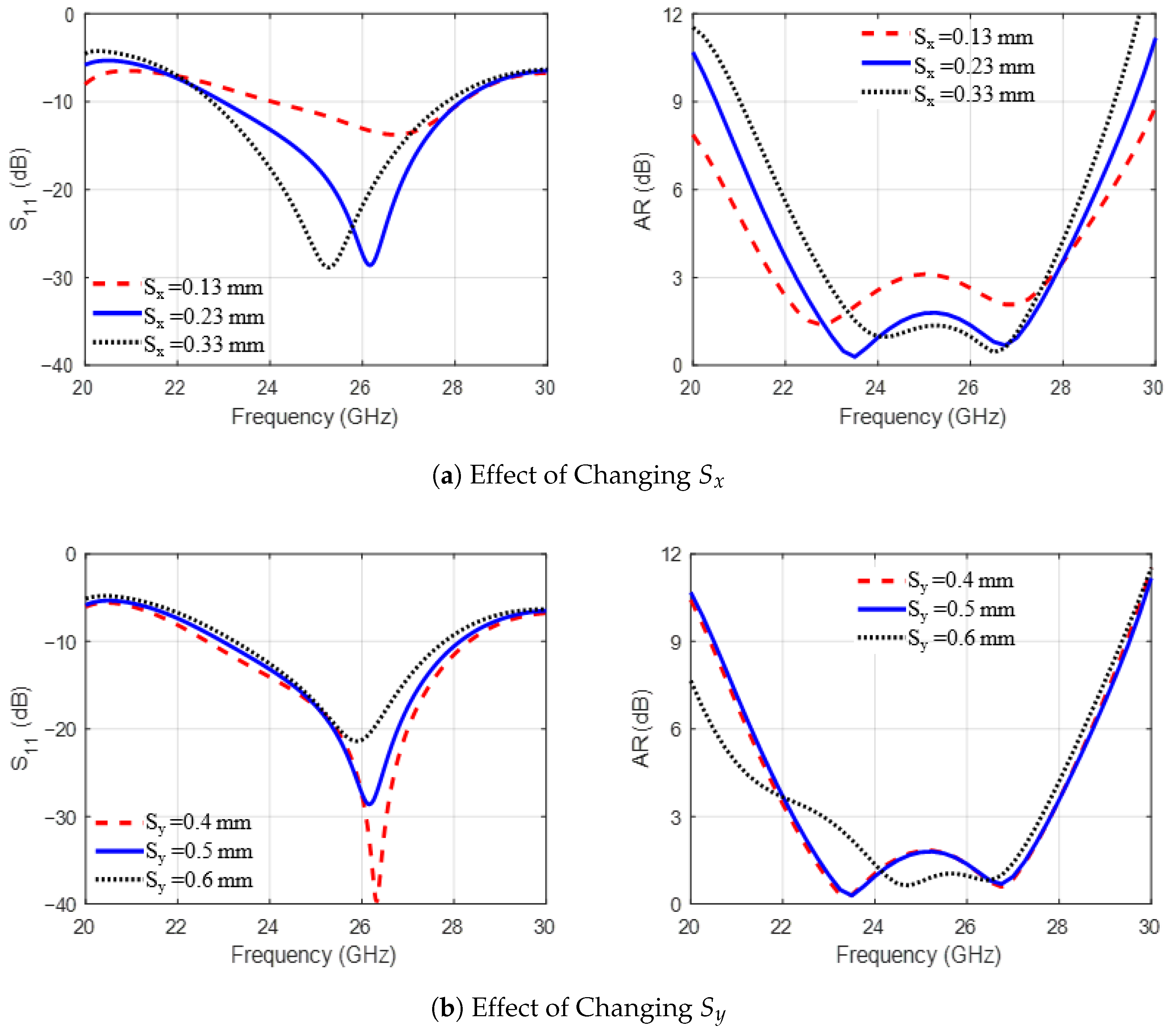

Figure 5a,b investigate the effect of varying distance

between the electric dipole arms and the L-feeder and changing the gap size

between the stairs-strip and the rectangular strip with trimmed corners. As observed in

Figure 5, changing

from 0.13 mm to 0.33 mm and

from 0.4 mm to 0.6 mm affects impedance matching and AR. This is due to changes in the induced current on the MED surface. From the parametric study, it can be concluded that the dimensions of the L-feeder, the rectangular strips, and the sets of via holes control the impedance-matching bandwidth of the proposed antenna. However, the CP radiation characteristics or AR are controlled via the staircase steps and trimmed corners of the rectangular strips. Furthermore, the distances between the L-feeder and the rectangular strip radiators,

and

, affect both

and the AR bandwidths. Additionally, it was observed during the study that small changes in other dimensions may deteriorate

or AR bandwidths.

2.2. Antenna Final Design

The optimized dimensions of the final MED antenna are given in

Table 1. The optimized structure’s radiation characteristics (

and AR) were simulated using ANSYS HFSS and CST Microwave Studio to verify the simulation results. The results are shown in

Figure 6. The values of

in

Figure 6a indicate a well-matched antenna over the band from

GHz to

GHz (20.6% fractional bandwidth). The CP covers the band from

to

GHz with a peak gain of

dBi as shown in

Figure 6c. The MED antenna introduces high radiation efficiency (≥

) in the operating bandwidth, as shown in

Figure 6d. Furthermore, since the results of both software are similar, the simulation setup of the proposed MED antenna is verified.

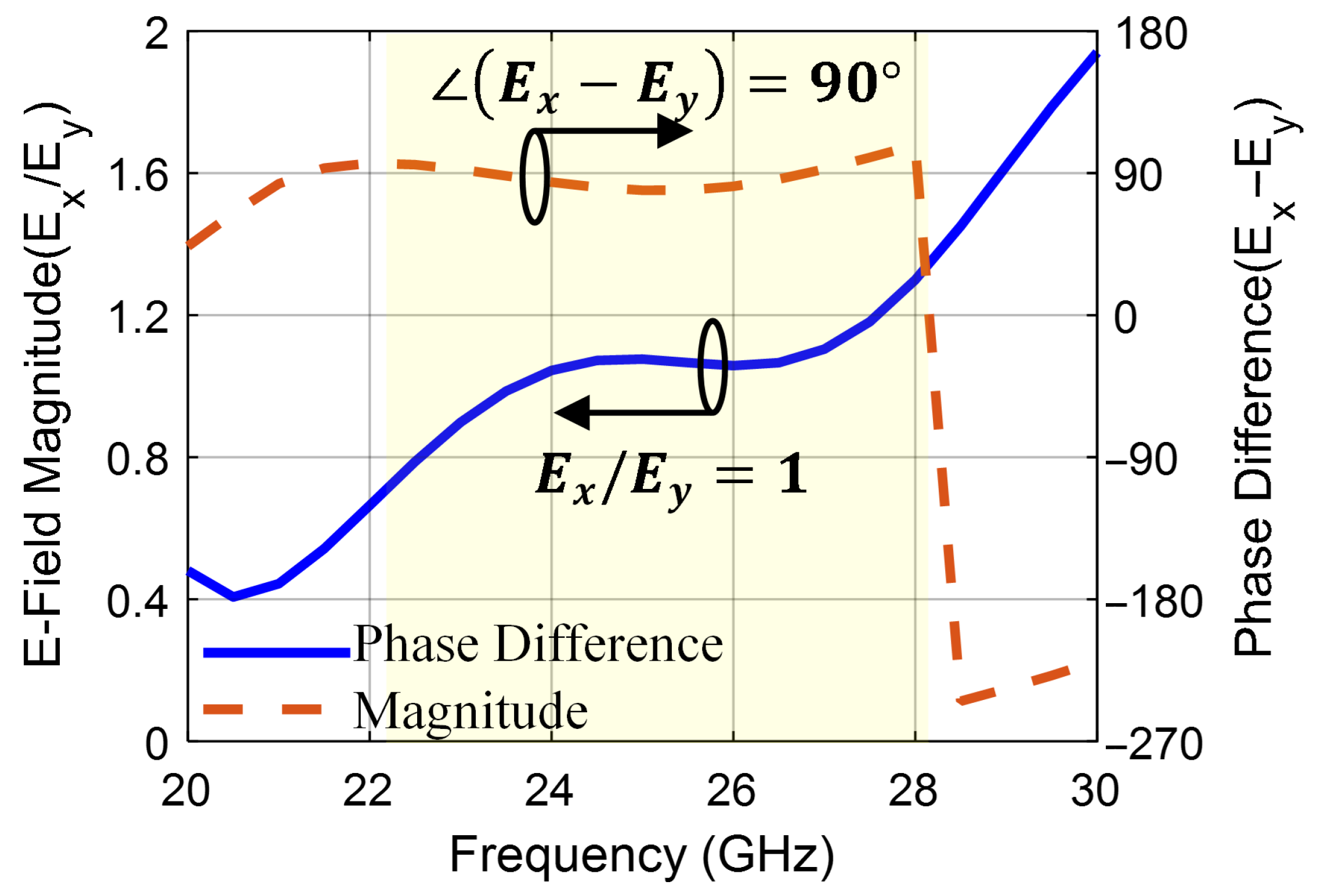

Next,

Figure 7 shows the surface current distribution at 25 GHz for different time phases

,

,

, and

. It can be observed that the current rotates in an anticlockwise direction, generating RHCP field in the

-direction. Two electric field components,

and

, with equal amplitude and a

phase shift, are generated from the electric dipole strips and magnetic dipole via holes as shown in

Figure 8. Finally, the right-hand (

) and left-hand (

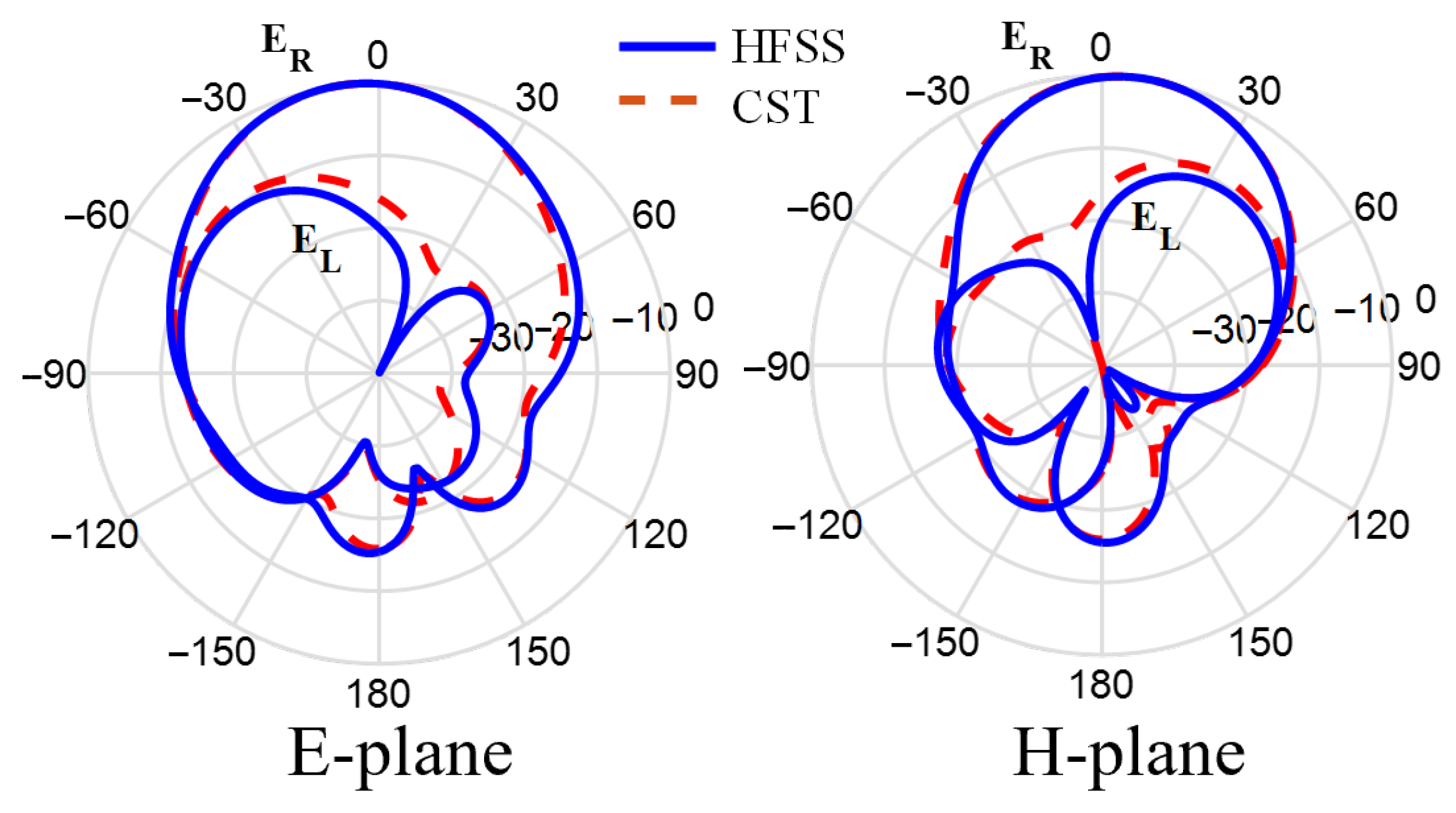

) electric field radiation patterns in the different planes are plotted in

Figure 9. The symmetrical radiation patterns are radiated with a co-/cross-polar level (

) of 20 dB and half-power beamwidth (HPBW) of

.

2.3. Antenna Equivalent Circuit

The equivalent circuit (EC) model characterizes the antenna’s electrical behavior as a network of lumped elements, which includes resistors, inductors, and capacitors [

20,

21,

22]. The EC effectively models the resonant and impedance properties that govern the antenna’s interaction with electromagnetic waves. The EC of the proposed wideband MED antenna is presented in

Figure 10a. The lumped-element EC accurately equivalent the MED physical structure by modeling the electric dipole as a series RLC branch (

for staircase capacitance,

for strip inductance,

for losses) and the magnetic dipole as parallel RLC branches, (

,

, and

) for shorted via holes, with the L-probe inductive and capacitive effects modeled by series circuit (

and

) aiding matching to

with the source. The EC input impedance of the MED antenna is given by:

The superposition of the electric and magnetic dipoles’ resonance frequencies leads to the MED antenna’s wideband characteristics [

23]. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is employed to determine the EC elements by iteratively adjusting their values within a defined search space to minimize a fitness function, as discussed in [

22]. The fitness function is the mean square error (MSE) between the simulated input impedance (HFSS),

and the impedance calculated using the EC model,

, over a range of frequency points,

. The fitness function

F is defined by [

20]:

Table 2 presents the estimated values of the EC elements, obtained by PSO via employing 26 particles at 1001 frequency points.

Figure 10 compares the simulated input impedance with that calculated using the EC model. The proposed EC model effectively characterizes the MED antenna across a wide frequency band, achieving a mean square error (MSE) of 0.22% in the resistance component and 3.09% in the reactance component relative to the simulation results.

The EC guides the design by enabling rapid parametric sweeps. For example, increasing the number of staircase steps correlated with higher C values, predicting AR bandwidth extension over the operating frequency band. This analytical tool complements HFSS/CST simulation to optimize dimensions prior to fabrication, ensuring wideband CP without the need for empirical trials.

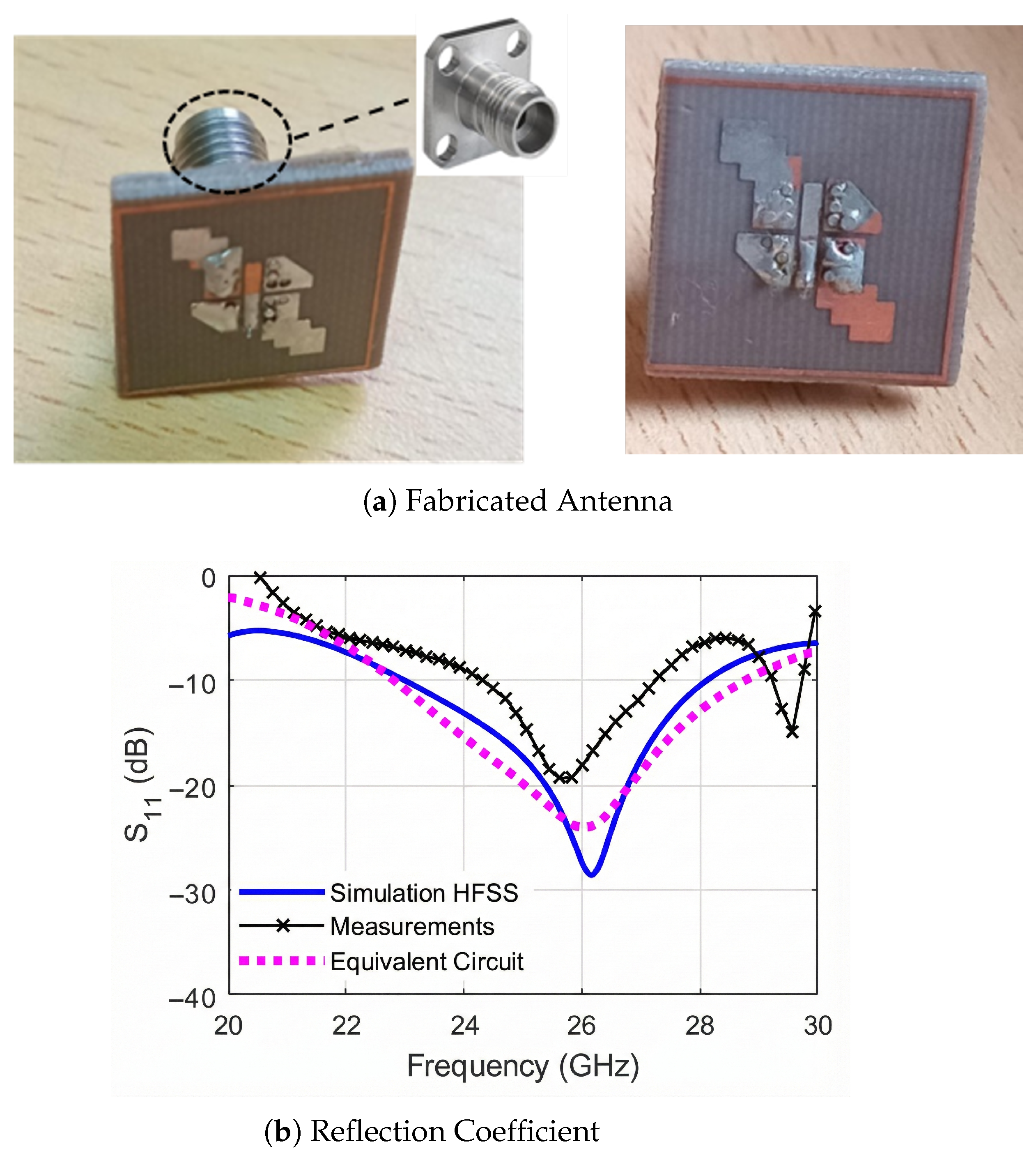

2.4. Antenna Fabrication Results

A prototype of the proposed MED antenna is fabricated on a Rogers 5880 substrate with dimensions

, where

is calculated at 25.5 GHz. The fabricated antenna is shown in

Figure 11a. The prototype is fed using a

2.92 mm connector. The magnitude of the reflection coefficient

of the prototype is measured using a calibrated Anritsu MS46322A (Anritsu, Kanagawa, Japan) vector network analyzer. The measurement results are plotted in

Figure 11b and are compared with the simulation and EC results. The measured

fractional bandwidth is 12.6% (24.13 GHz to 27.32 GHz). The differences between the measured and simulated results are due to the soldering effect and the losses from the connector and cable. Throughout the paper, the far-field radiation characteristics, including gain, AR, and radiation patterns, are simulated using ANSYS HFSS and CST Microwave Studio, as our laboratory currently lacks the necessary measurement equipment to conduct experimental validations.

Furthermore, a comparison between the proposed MED antenna and work reported in the literature is presented in

Table 3. Although the size of the proposed MED is larger than that in [

24,

25], it prioritizes an AR bandwidth of

compared to

in [

24] and

in [

25] with a gain enhancement by

dBi. The increased size accommodates ground slots for ≥23 dB isolation, reducing mutual coupling by 5 dB over without parasitic elements, enhancing suitability for 5G massive MIMO.

3. MIMO-CP Antenna: Design Methodology

This section first discusses the design methodology for a

MIMO antenna using the optimized MED element from

Section 2. Furthermore, a numerical investigation is performed using two MED elements on a MIMO-CP antenna for 5G applications. The investigated parameters are the antennas’ configuration with respect to each other, the separation between them, and the introduction of a cutting slot in the ground between the antennas. Next, based on the

MIMO antenna investigation, the design is expanded to a

MIMO-CP antenna.

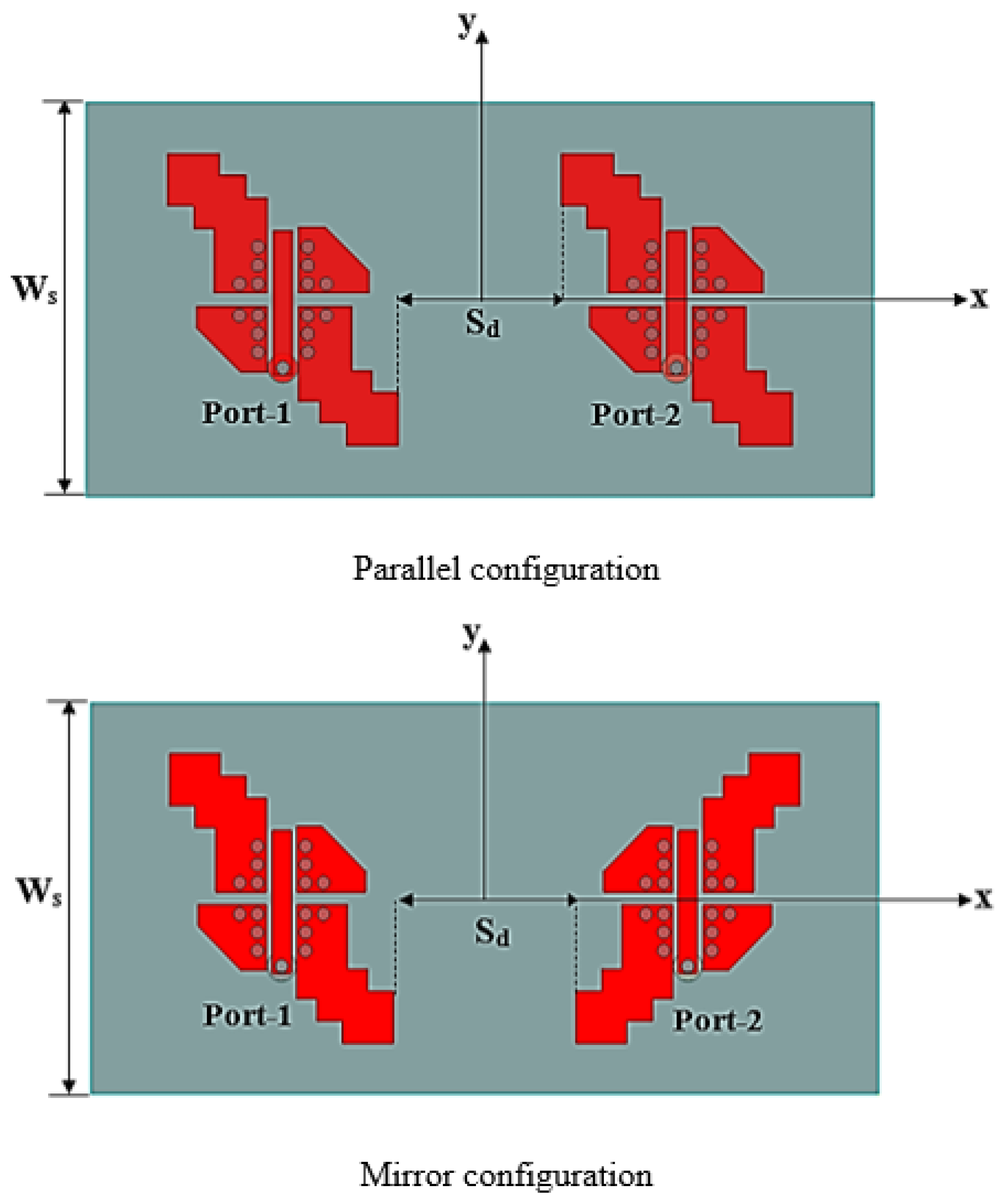

3.1. Antennas’ Configuration

The performance of the

MIMO antenna is studied under two configurations. The single antenna is either duplicated in a parallel or a mirror configuration, as shown in

Figure 12. Here, the MIMO-CP antenna size is

mm

3 with an interconnected grounded substrate to maintain uniform voltage levels for the entire antenna system.

Figure 13a,b compare the two MIMO configurations based on

,

,

,

, and AR. The parallel configuration introduces non-coherent reflection coefficients

and

at the two ports with the elements isolation (

and

) below

dB. The mirror configuration introduces coherent reflection coefficients with a better match (

dB) and good isolation, ranging from

dB to

dB at 24 GHz. Furthermore, the mirror configuration extends the AR bandwidth to

GHz, compared to

GHz for the parallel configuration.

The surface current distributions at 25 GHz for both configurations at different port excitations are shown in

Figure 14. In these simulations, when a port is excited (ON), the other port (OFF) is terminated with a matched load. From

Figure 14b, it can be observed that the surface current is maximum on the excited element (ON), while it is zero on the other element (OFF) for the mirror configuration; thus, high isolation is achieved between elements. However, for the parallel configuration in

Figure 14a, there is a small induced surface current on the L-feeder of the OFF element.

In conclusion, the polarization diversity in the mirror configuration enhances the isolation between elements and improves impedance matching, which aligns with the AR bandwidth. Thus, in the next sections, only the mirror configuration is considered.

3.2. Antennas’ Separation

A parametric study investigated the effect of changing the separation between the individual elements in the MIMO mirror configuration.

Figure 15 shows the effect of changing the inter-element spacing,

, from 1 mm to 6 mm on

and

. As the figure shows, the closely placed elements still have good isolation (

dB), with better isolation achieved at the high-frequency band. Thus,

mm was selected to reduce the size of the whole structure.

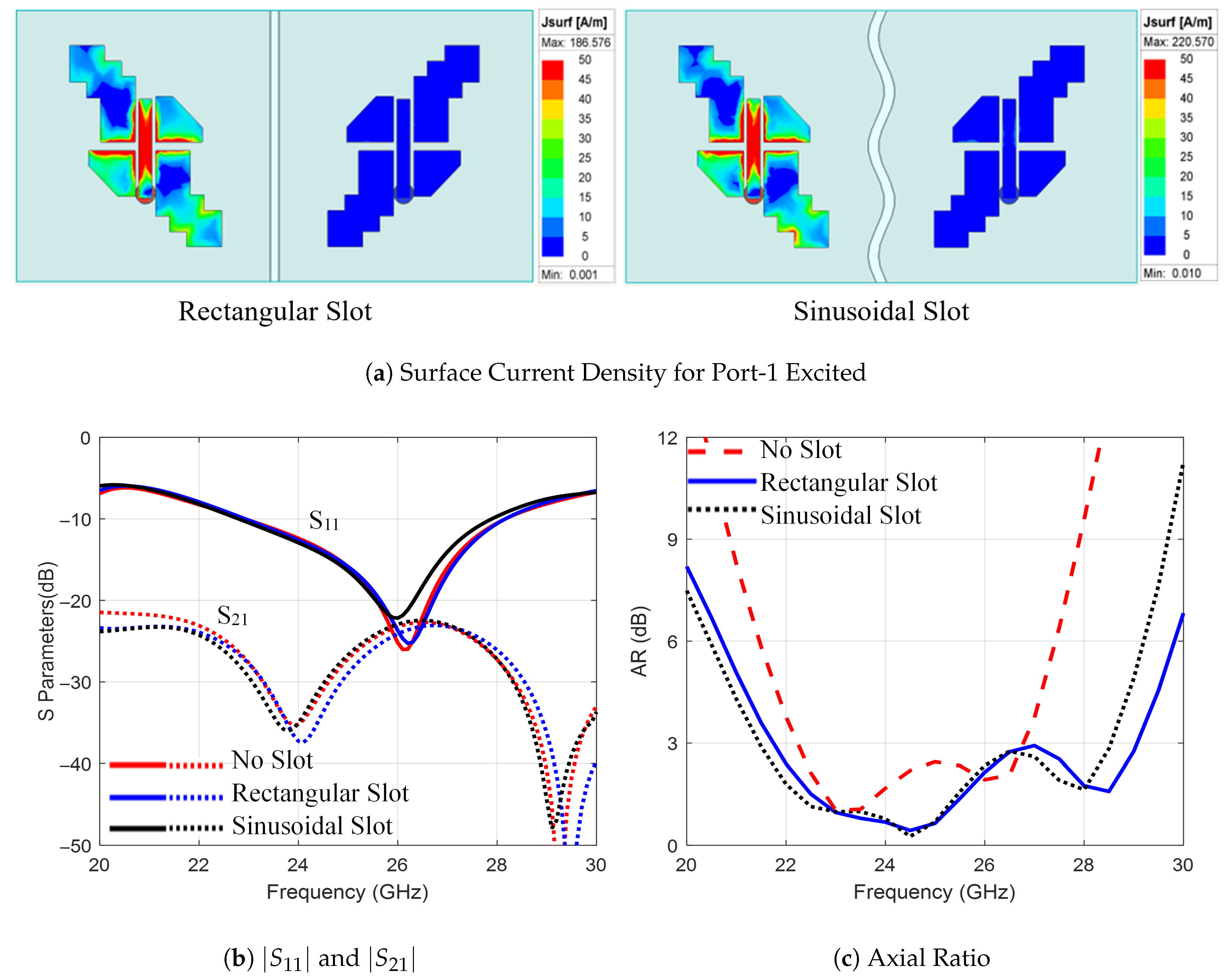

3.3. Ground Slot

Next, a cutting slot is centrally etched on the ground plane between the individual elements to compensate for the effect of closely spaced elements in the MIMO-CP structure. The cutting slots eliminate the current leakage between the elements, improving isolation and increasing the AR bandwidth.

Two different-shaped slots are investigated: a rectangular slot and a sinusoidal slot. Each slot had a length of 15 mm and a width of

mm. Here, the MIMO mirror configuration with

mm was considered. The surface current density for different ports excited at 25 GHz is shown in

Figure 16, along with the S-parameters and the AR results. As shown in

Figure 16b, the bandwidth is improved to

GHz for rectangular slots and 5.1 GHz for sinusoidal slots. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 16c, the AR bandwidth is

GHz and 7 GHz for rectangular and sinusoidal slots, respectively. In conclusion, the rectangular slot is considered for the MIMO configuration.

Next, the 2D electric field components

and

radiation patterns for ports 1 and 2 at 25 GHz for the rectangular slot are shown in

Figure 17. Port-1 excitation results in the dominance of the RHCP field component. In contrast, port-2 excitation in the broadside direction leads to the dominance of the LHCP component. Moreover, the results show that the radiation pattern of each element was not affected by the MIMO configuration, which is due to the high isolation between the elements.

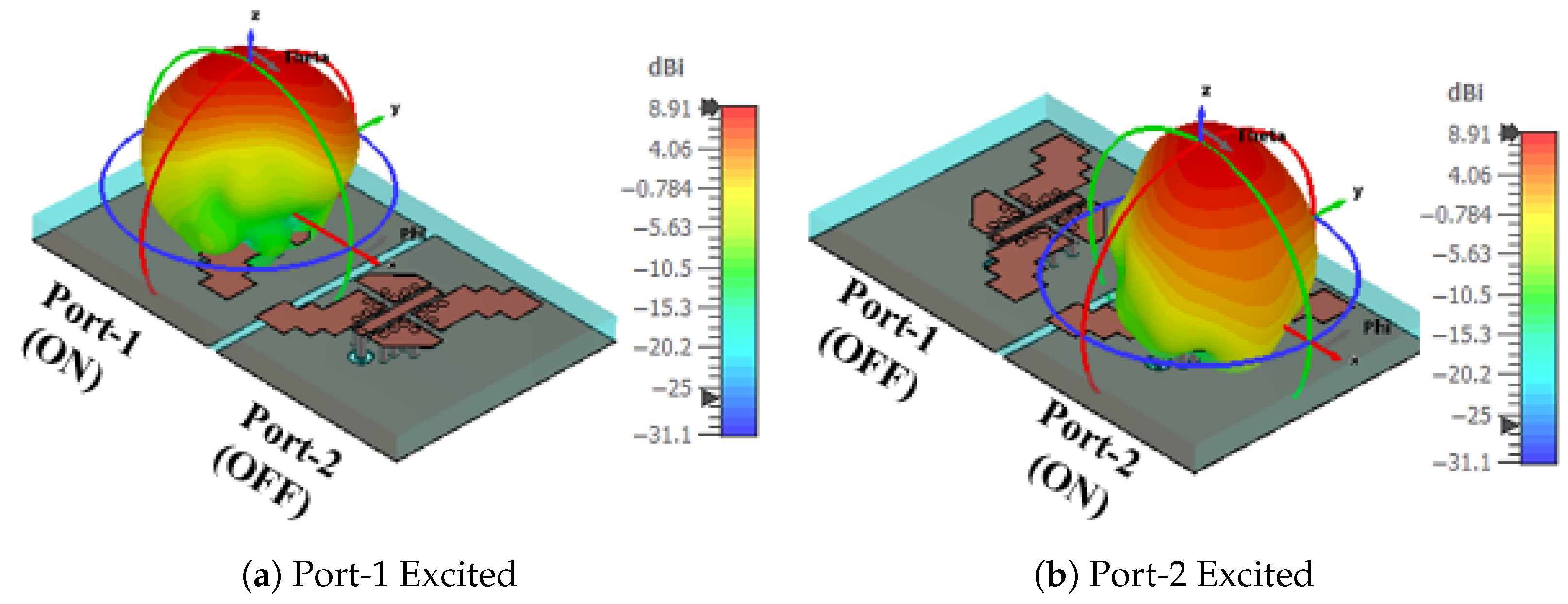

Figure 18 shows the 3D gain pattern radiated by each element of a

MIMO system operating at 25 GHz. The elements exhibit identical broadside radiation patterns, achieving a peak gain of

dBi per element, which is attributed to the high isolation between them.

3.4. A MIMO

Based on the results from the previous sections, a

MIMO system with four MED antenna elements is investigated and is shown in

Figure 19a. The MED elements are separated by

mm to maintain high isolation between them.

Figure 19b shows the response of the S parameters for the

MIMO system with (

dB) over the frequency band from 22 GHz to 28 GHz, with mutual coupling between ports maintained below (

dB). The 3D gain patterns for one single port (ON) at 25 GHz are shown in

Figure 20. An identical broadside gain pattern with a peak gain of 8.9 dBi is radiated from each element in the 4-element MIMO system.

Figure 21 shows the gain frequency response and the axial ratio of the

and

MIMO systems. Over the operating bandwidth, the gain varies from 8 dBi to 8.9 dBi, with AR bandwidth extending from 22.6 GHz to 27.1 GHz for a

MIMO system and from 23 GHz to 26.5 GHz for a

MIMO system. In conclusion, expanding the MIMO to a

design improved performance without affecting individual elements.

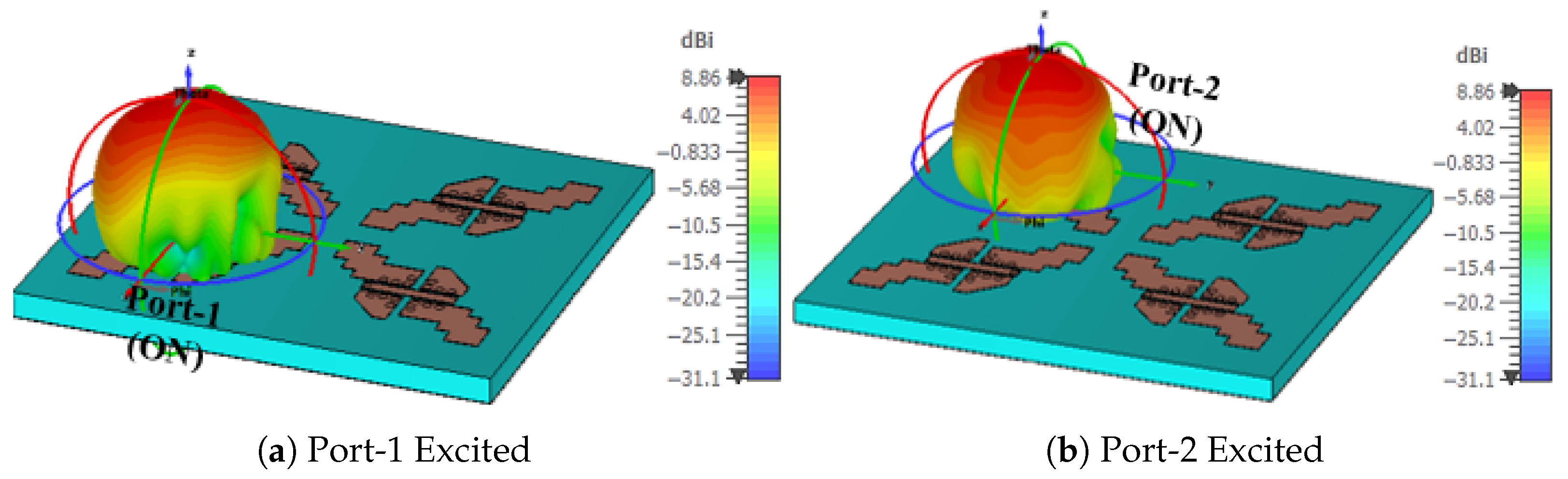

4. MIMO Diversity Performance Analysis

In this section, the MIMO diversity performance analysis is investigated for the

MIMO antenna system with optimized elements using different parameters. The considered MIMO is the mirror configuration with a ground rectangular slot and an

mm inter-element separation. The study is conducted to ensure the validity of the MIMO system within the performance metric threshold limits introduced in the literature [

27,

28]. First, the envelope correlation coefficient (ECC) is evaluated, which shows the efficiency of the communication channel isolation. The ECC can be computed using the scattering (S) parameters for high-efficiency antennas, or using the far-field radiation pattern for low-efficiency antennas to account for losses [

27].

Utilizing the S-parameters, the ECC between each pair of antenna elements can be calculated as

Here

, and “ * ” denotes the complex conjugate of the S-parameter.

and

are the reflection coefficients at ports

i and

j, respectively, and

and

are the transmission coefficients between ports

i and

j.

Furthermore, by using the radiation pattern, the ECC can be evaluated as

Here

is the 3D radiation pattern field with excitation at port

, “·” denotes the Hermitian product, and

is the solid angle.

Furthermore, an ideal MIMO system has a zero ECC value; however, ECC < 0.5 is acceptable [

27]. In a 4-element MIMO system, the ECC should be calculated for each pair of elements (for example, {1,2}, {1,3}, {1,4}, {2,3}, {2,4}, {3,4}), with the maximum ECC generally reported as a conservative measure of the system’s correlation. The ECC result for the

MIMO-CP MED antenna system is shown in

Figure 22a. Within the antenna bandwidth, the ECC value is less than

over the band from 22 GHz to 28 GHz, which satisfies the requirement and indicates a low correlation between the antennas. Consequently, the mutual coupling between the elements is low, which is desirable.

Next, diversity gain (DG) is evaluated. DG is the power transmission loss due to the employment of the diversity scheme in the MIMO systems [

28]. It is calculated as

Based on the ECC results in

Figure 22a, the value of DG for each pair of elements of the proposed MIMO is approximately 10 dB within the system bandwidth, which agrees with the required threshold to ensure good diversity performance of the MIMO system. The DG values are shown in

Figure 22b.

To measure the maximum data transmitted across a communication channel without losses, the channel capacity loss (CCL) is calculated. The CCL for 4-port MIMO is calculated as follows [

27]:

where

and

The CCL results are shown in

Figure 22c. Within the MIMO bandwidth, the CCL value is less than

bits/s/Hz. This result is acceptable since it is less than the threshold value of

bits/s/Hz required for industrial applications [

28].

The next calculated parameter is the Mean effective gain (MEG) of the MIMO antenna. MEG is the ratio of the MIMO antenna’s received power to the isotropic antenna’s received power. MEG is calculated for each port of the system as [

27]

Here

is the radiation efficiency of the

ith antenna. Furthermore, a MIMO antenna’s performance improves when the ratios of the MEG1/MEG2 and MEG3/MEG4 are less than 3 dB [

28]. Moreover,

Figure 22d shows the plots of MEG1, MEG2, MEG3, MEG4, MEG1/MEG2, and MEG3/MEG4. In this figure, the values of the MEG1/MEG2 and MEG3/MEG4 are 0 dB within the operating band.

The last calculated parameter is the total active reflection coefficient (TARC), which describes the changes in self and mutual impedance of the individual and adjacent elements. In MIMO systems, the allowable value for TARC should be less than

dB. TARC is calculated as [

27]

Here

is the excitation phase difference between the two ports. From the results shown in

Figure 22e, the TARC values are less than

dB within the desired band; thus, the requirement is satisfied.

In conclusion, the performance parameters of the MED MIMO system are presented and compared with those reported in the literature in

Table 4. The proposed antenna meets the requirements of MIMO systems with high-gain and efficient performance with consistent impedance matching and CP bandwidths.

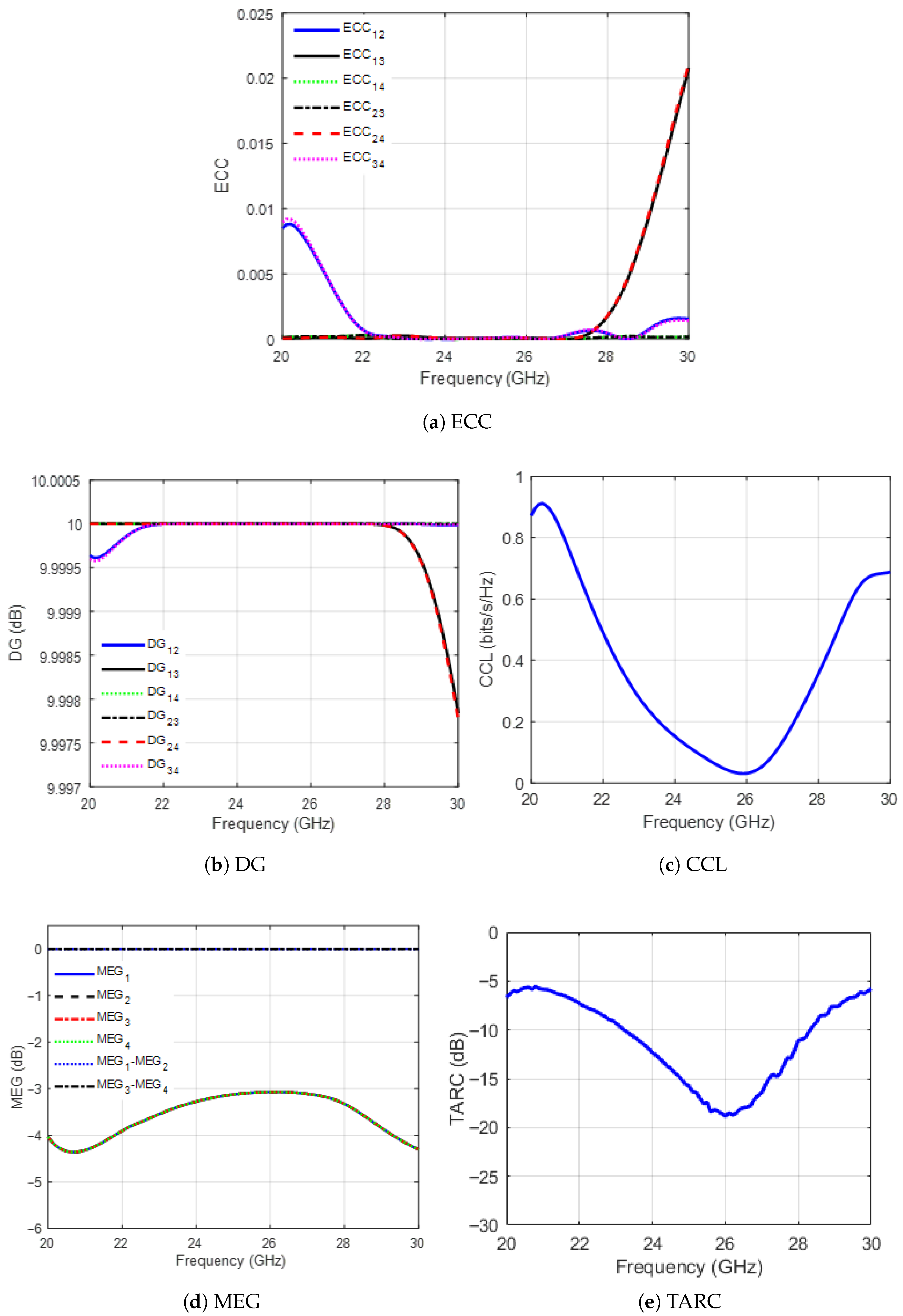

5. Wideband Sequential MED Antenna Arrays

The radiation characteristics of the MED antenna are significantly improved by implementing a sequential array configuration [

32,

33]. It employs a sequential array of elements characterized by a

orientation, rotation angle, and a

phase difference between adjacent elements. For example, in [

34], the authors designed an

SIW-MED antenna array for CP radiation over the frequency band from 23.3–30.8 GHz and AR bandwidth of 27.8% (23.2–30.8 GHz) with a peak gain of 20.2 dBi.

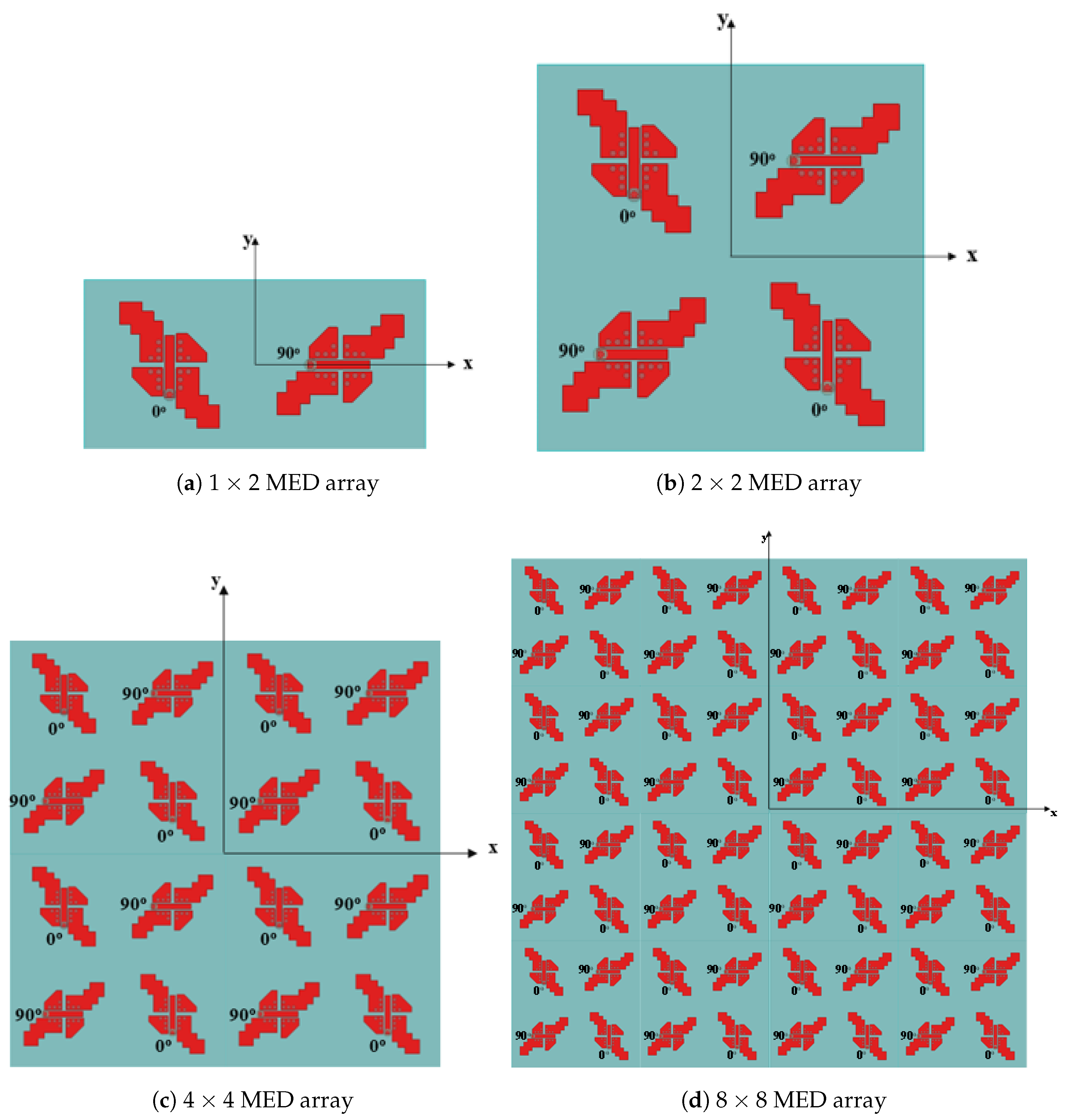

Figure 23 shows various sequential array arrangements,

,

,

, and

MED element configurations, to evaluate their impact on antenna performance. The frequency responses of the reflection coefficients

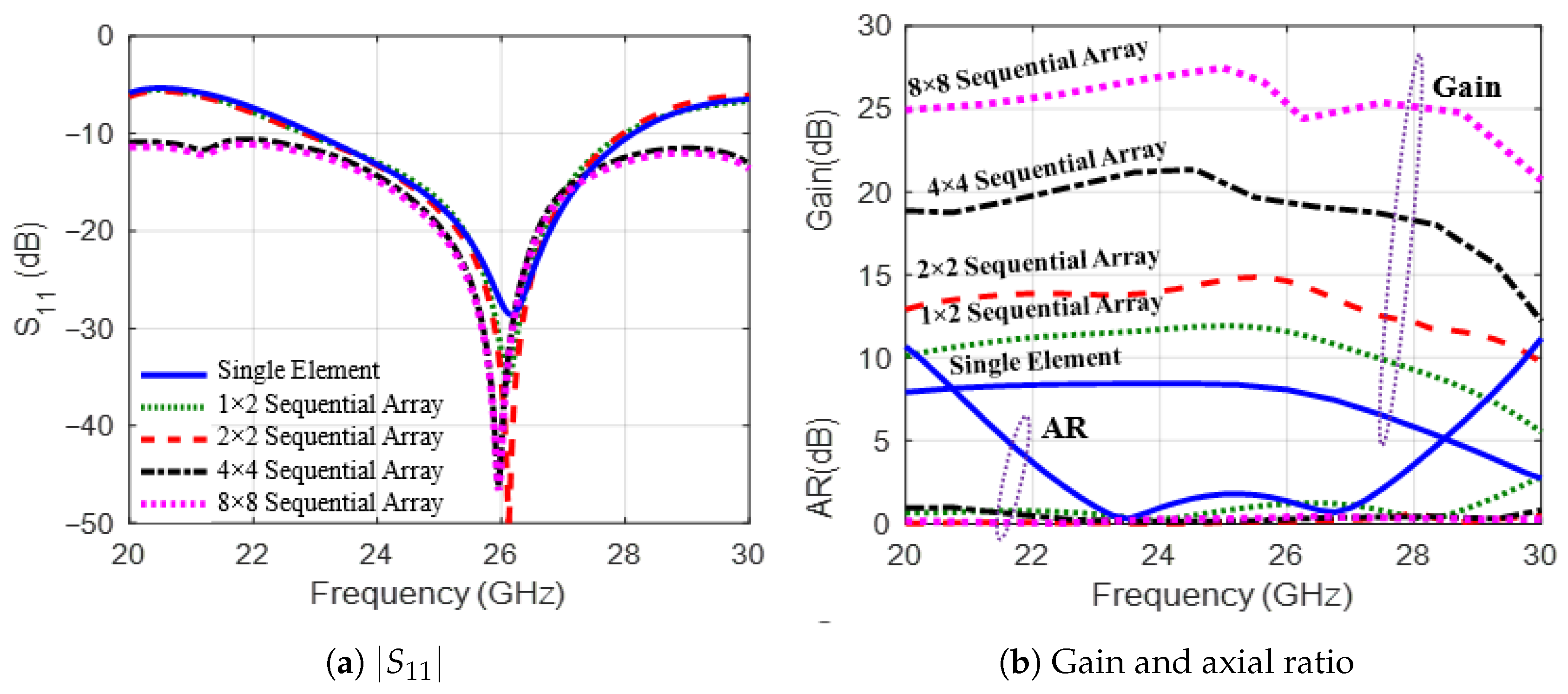

, gain, and AR for these different array arrangements are presented in

Figure 24.

The single element achieves a minimum

of approximately

dB around 25 GHz, with a fractional bandwidth of

as shown in

Figure 24a. The sequential array improves the impedance matching with a minimum of

dB for the

array, and

dB for the

array. Furthermore, the

and

arrays exhibit the best impedance matching with a minimum

of

dB at 25 GHz, corresponding to a significantly enhanced fractional bandwidth of

. As shown in

Figure 24b, the gain for the single element peaks at around 8 dBi. Furthermore, the sequential arrays demonstrate progressive improvement: the

array achieves a peak gain of 12 dBi, the

array reaches

dBi, the

array attains a

dBi gain, and the

array enhances the gain to

dBi with all configurations maintaining stability across the operating bandwidth. Moreover, incorporating a

sequential phase shift between array elements significantly improves the CP bandwidth, maintaining an

dB and stable gain across the entire frequency range from 20 GHz to 30 GHz.

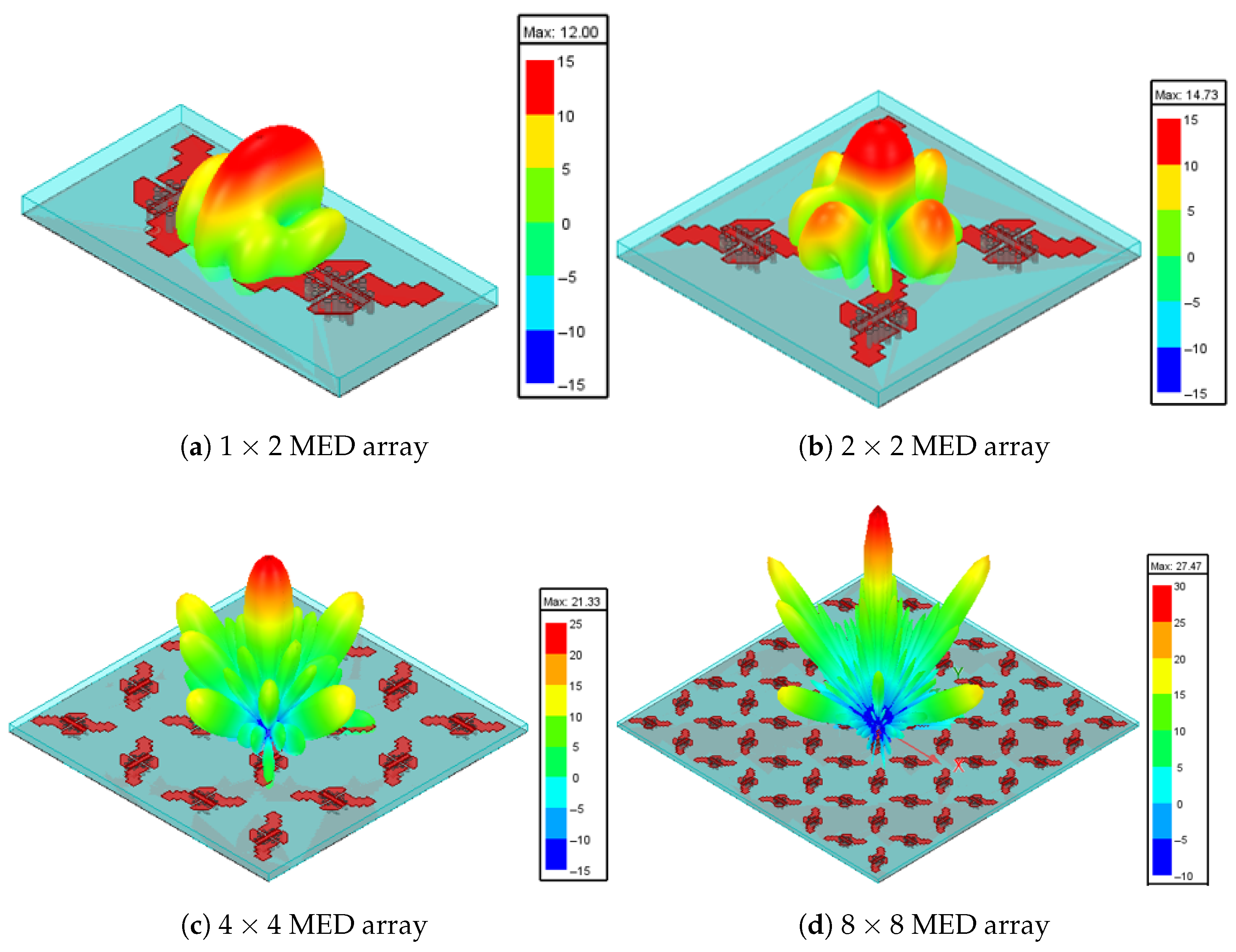

Figure 25 illustrates the 3D gain patterns at 25 GHz for different sequential arrays. The broadside radiation characteristic has a peak gain of 12 dBi, 14.7 dBi, 21.3 dBi, and 27.47 dBi for the

,

,

, and

MED array configurations, respectively. The cumulative effect of increasing the array size and the sequential phase improves the directivity of the main lobe and reduces the side lobes.

In [

35], a

MED array achieves a peak gain of

dBi with a wide-impedance bandwidth (

–

GHz) and CP bandwidth (

–43 GHz). However, its multilayer design with five substrates increases fabrication complexity. In contrast, the proposed sequential

MED array in this work uses a single-layer

substrate with staircase dipoles, achieving a higher gain of 22 dBi, consistent impedance bandwidth, and an

dB over 20–30 GHz, which allows easier integration for 5G systems.

6. Conclusions

A wideband circularly polarized novel MED antenna is designed, optimized, and implemented for 5G mmWave applications. The antenna features a proximity-coupled L-feeder, an electric dipole composed of diagonally placed rectangular staircase strips and trimmed corner strips, and a magnetic dipole made of sets of via holes. To achieve wideband impedance matching and CP bandwidths, the design evolution is investigated through a four-step process and a parametric study. Next, various MIMO systems utilizing the proposed MED antenna are designed. The effects of the elements’ arrangement, the separation between them, and the inclusion of a ground slot are studied. Furthermore, a MIMO diversity performance analysis is conducted for the optimum configuration of a MIMO antenna system. The results show that the performance metrics fulfill the requirements within the desired bandwidth.

Finally, MED arrays are investigated, achieving wideband performance through the implementation of sequential array configurations. Employing sequential rotation and a phase shift between MED array elements enhances impedance matching and CP bandwidths over the band from 20 GHz to 30 GHz. A high gain of 27.47 dBi with dB is achieved using an arrangement of array. All reported AR, radiation pattern, and gain results are simulation-based, due to the unavailability of far-field measurement facilities in this study. In future work, we intend to conduct experimental far-field measurements to validate these results and optimize the design for practical applications.