A Novel Denoising Method for Mud Continuous-Wave Signals Based on Selective Ensemble Strategy with Particle Swarm Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- For the first time, a selective ensemble strategy is proposed in the field of mud continuous-wave signal denoising, fully leveraging the complementarity of multiple excellent heterogeneous filtering algorithms in feature extraction and applicable scenarios.

- (2)

- The PSO algorithm is introduced to dynamically and adaptively realize the selection of filtering algorithms and their weight matching, which are compatible with the target scenario. This enables our method to achieve data-driven and intelligent filter combination configuration based on real-time signal characteristics, breaking through the limitations of fixed-parameter filters or fixed ensemble strategies.

2. Establishing the Mud Continuous-Wave Signal Model and Analysis of Difficulty in Denoising

2.1. Establishing the Mud Continuous-Wave Signal Model

2.2. Analysis of Difficulty in Denoising

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

3.2. PSO-Based Selective Ensemble Filtering Strategy

4. Experimental Result

4.1. Simulation Processing Example

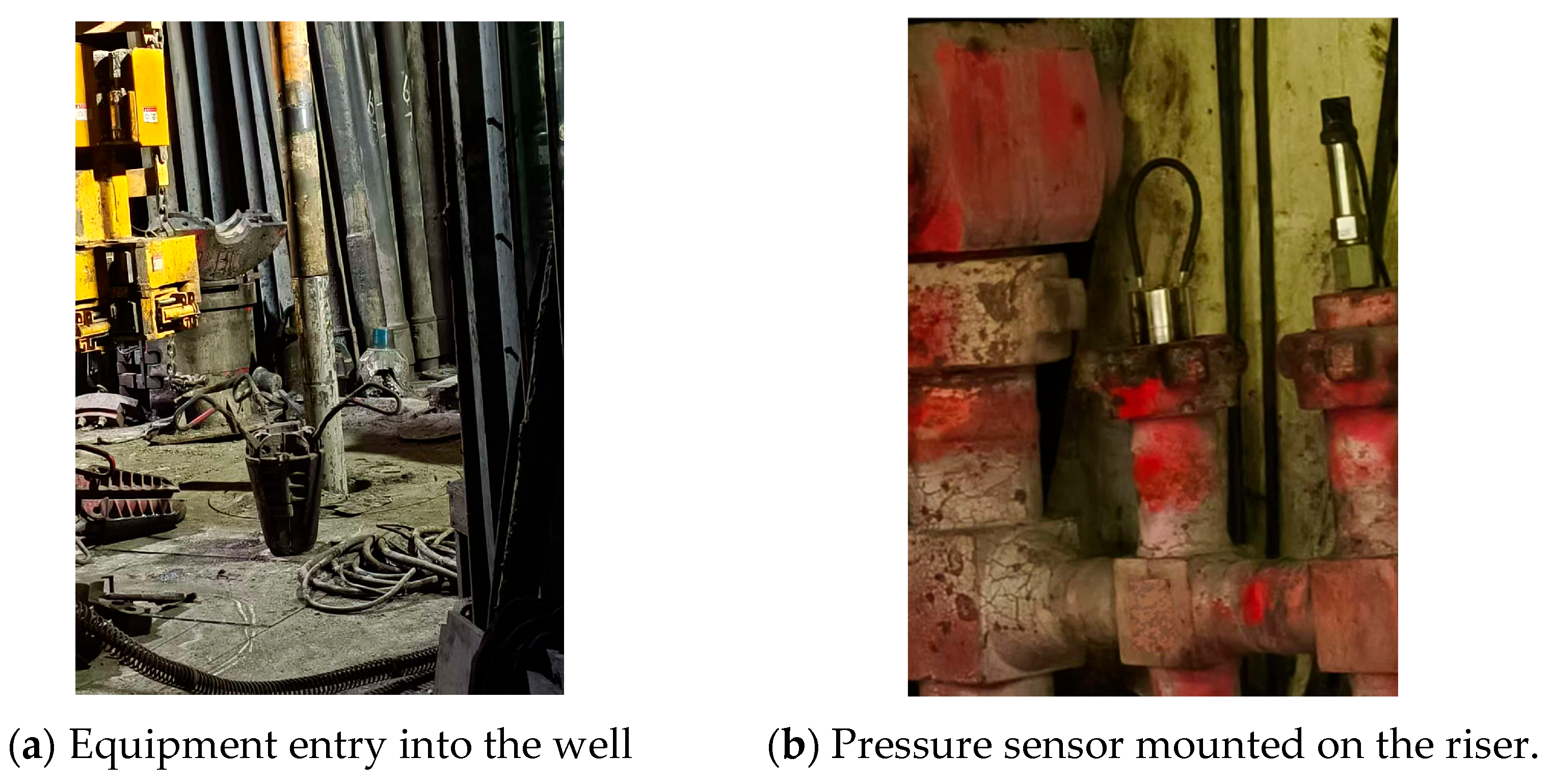

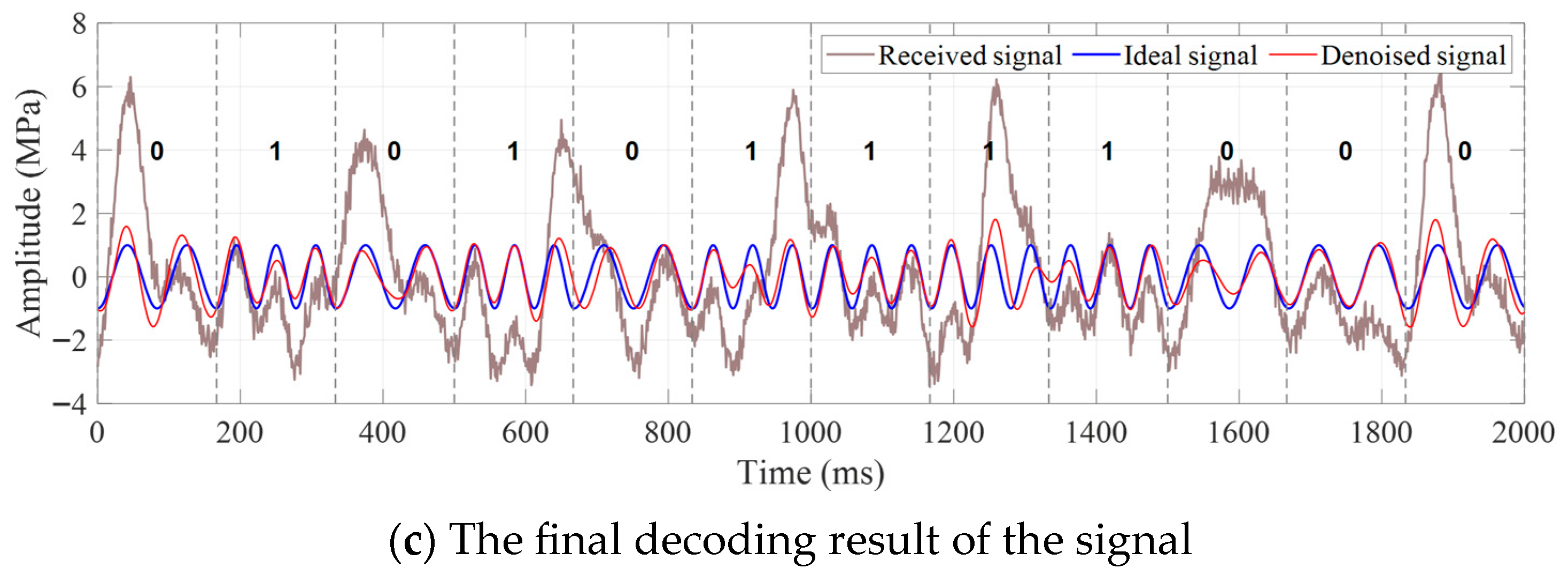

4.2. Real Data Processing Example

4.3. Analysis of Algorithm Runtime and Practicality

4.3.1. Theoretical Analysis of Computational Complexity

- (1)

- Using Equation (8), the N candidate signals are fused by weighting them with the current weight vector , which has a computational complexity of .

- (2)

- Compute the mean squared error between the fused signal and the ideal reference signal, which has a computational complexity of .

4.3.2. Runtime Statistics

4.3.3. Discussion on Online Practicality

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mwachaka, S.M.; Wu, A.; Fu, Q. A Review of Mud Pulse Telemetry Signal Impairments Modeling and Suppression Methods. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2019, 9, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xue, L.; Fan, H.H.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z. Analysis of Pressure Wave Signal Generation in MPT: An Integrated Model and Numerical Simulation Approach. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 209, 109871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Li, G.; Meng, Y.F.; Shu, G.; Zhu, K.L.; Xu, X.F. Attenuation Law of MWD Pulses in Aerated Drilling. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yan, Z.D.; Sun, R.R.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H. Study on Signal Decomposition-Based Pump Noise Cancellation Method for Continuous-Wave Mud Pulse Telemetry. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 288, 211948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Reckmann, H. System and Method for Pump Noise Cancellation in Mud Pulse Telemetry. U.S. Patent 7,577,528 B2, 18 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Chin, W.C. High Speed Telemetry Signal Processing. U.S. Patent 2017/362933 A1, 26 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Keman, L. Adaptive Noise Cancellation for Electromagnetic-While-Drilling System. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information Science and Control Engineering (ICISCE), Beijing, China, 8–10 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reckmann, H.; Neubert, M.; Wassermann, I. Two Sensor Impedance Estimation for Uplink Telemetry Signals. U.S. Patent 7,423,550, 9 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reckmann, H.; Wassermann, I. Channel Equalization for Mud-Pulse Telemetry. U.S. Patent 7,940,192, 10 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, F.Z.; Zhang, Z.J.; Hu, J.W.; Xu, J.M.; Wang, S.Y.; Wu, Y.Z. Adaptive Dual-Sensor Noise Cancellation Method for Continuous Wave Mud Pulse Telemetry. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2018, 162, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.D.; Xu, W.Y.; Ai, C.W.; Geng, Y.F. Parametric Study on Pump Noise Processing Method of Continuous Wave Mud Pulse Signal Based on Dual-Sensor. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2019, 178, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, W.; Greten, A.; Ben Brahim, I.; Akimov, O. Evolution in Reliability of High-Speed Mud Pulse Telemetry. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 2–5 May 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Sun, F. A Drilling Fluid Pulse Signal Processing Method Based on Kalman Filtering. China Pet. Mach. 2015, 43, 39–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Yan, Z.D.; Gao, T.Z.; Sun, H.H.; Li, G.L.; Wang, J.F. Study on Model-Based Pump Noise Suppression Method of Mud Pulse Signal. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021, 200, 108433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.Z.; Wu, J.F.; Su, Z.G.; Ma, H. A Continuous Wave Signal Denoising Method for Measurement While Drilling. CN116955941B, 19 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.L. Study on Transmission Characteristics and Processing Methods of Continuous Wave Signals in Logging While Drilling. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Zheng, Q.; Yen, N.C.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The Empirical Mode Decomposition and the Hilbert Spectrum for Nonlinear and Non-Stationary Time Series Analysis. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmiri, S. Comparative Study of ECG Signal Denoising by Wavelet Thresholding in Empirical and Variational Mode Decomposition Domains. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2014, 1, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.Z.; Jiang, Q.; Jin, G.Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Z. Noise Cancellation for Continuous Wave Mud Pulse Telemetry Based on Empirical Mode Decomposition and Particle Swarm Optimization. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021, 200, 108308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K. Research on Weak Signal Detection Method Based on Empirical Mode Decomposition and Adaptive Filtering. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.Y. Signal Denoising and Modulation Pattern Recognition Based on VMD. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi, A.; Slock, D.T.M.; Meilhac, L. Sparse Recovery Using an Iterative Variational Bayes Algorithm and Application to AoA Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Signal Processing and Information Technology (ISSPIT), Limassol, Cyprus, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S.; Wu, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Ni, W.; Liu, Y. Efficiency-Optimized 6G: A Virtual Network Resource Orchestration Strategy by Enhanced Particle Swarm Optimization. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spantideas, S.T.; Kapsalis, N.C.; Kakarakis, S.J.; Capsalis, C.N. A Method of Predicting Composite Magnetic Sources Employing Particle Swarm Optimization. Prog. Electromagn. Res. M 2014, 39, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ba, W.; Wang, Y. Emergency Response Resource Allocation in Sparse Network Using Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Samanta, S.; Biswas, D.; Dey, N.; Chaudhuri, S.S. Particle Swarm Optimization Based Parameter Optimization Technique in Medical Information Hiding. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research, Enathi, India, 26–28 December 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.X. Research on Filtering and Decoding Technology of Continuous Wave Mud Pulser Signals. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmala, A.; Malone, D.; Masak, P. Mud Pump Noise Cancellation System and Method. U.S. Patent 5,146,433, 8 September 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hutin, R.; Tennent, R.W.; Kashikar, S.V. New Mud Pulse Telemetry Techniques for Deepwater Applications and Improved Real-Time Data Capabilities. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27 February –1 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Ren, X.H.; Yan, Z.D.; Niu, L.Y.; You, Z. Research on Mud Pulse Signal Denoising Method Based on Model Entropy Processing. J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. 2024, 39, 98–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.J.; Ma, H.Y. A Mud Pulse Signal Denoising Method Based on Wavelet Transform-RBF Neural Network. Chinese Patent 202011125201.6, 23 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.J.; Wang, Y.B.; Jiang, W. Optimal Design and Simulation Implementation of Butterworth High-Pass Filter. Mech. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 52, 292–296. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.M.; Wang, Z.H.; Hu, W.; Hu, A.D.; Sun, J.Z.; Sun, Y. Electricity Theft Detection Based on Selective Ensemble Ranked by Kappa Fusion Coefficient. Electron. Des. Eng. 2025, 33, 90–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.J.; Liang, W.Q.; Xu, P.; Tong, Y.L.; Lou, K.L.; Pu, J.B. Moisture Ratio Prediction of Peucedanum Praeruptorum Slices During Microwave Vacuum Drying Based on Intelligent Ensemble Model. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2024, 55, 2206–2215. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Wu, X.; Bongard, J.C. Active Learning Through Adaptive Heterogeneous Ensembling. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2015, 27, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’95), Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| swarm size | 40 | individual learning factor c1 | 1.5 |

| dimensions | 10 | social learning factor c2 | 1.5 |

| inertia weight | 0.9→0.4 | 100 |

| Number | Denoising Method | The 1st Signal Group | The 2nd Signal Group | The 3rd Signal Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | SNR | MSE | SNR | MSE | SNR | ||

| 1 | Gaussian filter | 1.6108 | −5.0805 | 1.7785 | −5.5102 | 1.4972 | −4.7505 |

| 2 | EMD | 0.2273 | 3.4708 | 0.6407 | −0.6948 | 0.1899 | 3.2459 |

| 3 | Butterworth | 0.1107 | 6.5486 | 0.1184 | 6.2553 | 0.1101 | 6.3204 |

| 4 | Chebyshev | 0.0904 | 7.4264 | 0.1109 | 6.5410 | 0.0933 | 7.3092 |

| 5 | FIR | 2.8070 | −7.4926 | 3.0991 | −7.9221 | 2.6068 | −7.1686 |

| 6 | Wavelet processing | 1.6926 | −5.2956 | 1.9001 | −5.7976 | 1.5859 | −4.9689 |

| 7 | Kalman filter | 1.6289 | −5.0991 | 1.5121 | −4.7783 | 1.4531 | −4.3006 |

| 8 | VMD | 0.1123 | 6.4864 | 0.1272 | 5.9461 | 0.1151 | 6.7189 |

| 9 | EMD + band-pass | 0.1113 | 6.5254 | 0.1184 | 6.2567 | 0.1091 | 6.2745 |

| 10 | VMD + band-pass | 0.1047 | 6.7903 | 0.1182 | 6.2641 | 0.1095 | 6.5227 |

| 11 | PSO-based selective ensemble | 0.0849 | 7.7014 | 0.1039 | 6.8237 | 0.0870 | 7.4403 |

| Signal Group | Optimal Single Base Filter | Elective Ensemble Method | Improvement MSE | Improvement SNR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | SNR | MSE | SNR | |||

| 1st Group | 0.0904 | 7.4264 | 0.0849 | 7.7014 | 6.09% | 3.70% |

| 2nd Group | 0.1109 | 6.5410 | 0.1039 | 6.8237 | 6.31% | 4.32% |

| 3rd Group | 0.0933 | 7.3092 | 0.0870 | 7.4403 | 6.75% | 1.84% |

| Number | Filtering Method | MSE | SNR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gaussian filter | 3.6335 | −8.6052 |

| 2 | EMD | 1.5116 | −4.7749 |

| 3 | Butterworth | 0.1557 | 5.0745 |

| 4 | Chebyshev | 0.1890 | 4.2339 |

| 5 | FIR | 5.6002 | −10.4839 |

| 6 | Wavelet processing | 3.8655 | −8.8739 |

| 7 | Kalman filter | 2.5762 | −7.0410 |

| 8 | VMD | 0.1701 | 4.6909 |

| 9 | EMD+ band-pass | 0.1537 | 5.1310 |

| 10 | VMD+ band-pass | 0.1448 | 5.3917 |

| 11 | PSO-based selective ensemble | 0.1371 | 5.6308 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, C.; Cai, W.; Pang, D.; Yang, Y.; Du, X.; Duan, X.; Zhou, Y. A Novel Denoising Method for Mud Continuous-Wave Signals Based on Selective Ensemble Strategy with Particle Swarm Optimization. Sensors 2025, 25, 7594. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247594

Huang C, Cai W, Pang D, Yang Y, Du X, Duan X, Zhou Y. A Novel Denoising Method for Mud Continuous-Wave Signals Based on Selective Ensemble Strategy with Particle Swarm Optimization. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7594. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247594

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Chongjun, Wenbo Cai, Dongxiao Pang, Yan Yang, Xingwang Du, Xi Duan, and Yunxu Zhou. 2025. "A Novel Denoising Method for Mud Continuous-Wave Signals Based on Selective Ensemble Strategy with Particle Swarm Optimization" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7594. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247594

APA StyleHuang, C., Cai, W., Pang, D., Yang, Y., Du, X., Duan, X., & Zhou, Y. (2025). A Novel Denoising Method for Mud Continuous-Wave Signals Based on Selective Ensemble Strategy with Particle Swarm Optimization. Sensors, 25(24), 7594. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247594