1. Introduction

Temperature measurement is one of the most common tasks in our daily life, and many instruments have been developed in a variety of principles [

1]. It is still evolving according to the requirements, both in science and technology, such as distributed temperature measurement [

2], ultra-high temperature measurement [

3], and wide-range temperature measurement [

4], etc. Here, we focus on the intrinsic characteristics of explosion-proof methods, which can carry out regular temperature measurements with an all-optic property in order to be used in the petrochemical industry, etc. Some of the all-optic temperature sensors belong to this category and can be available for use, such as fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors [

5], machine vision [

6], fluorescent fiber-optic temperature sensors [

7], infrared temperature sensors [

8], radiation temperature sensors [

9], etc.

The FBG temperature sensor [

5] has been widely used in engineering to replace conventional strain gauges. This sensor is an all-optic sensor that requires an interrogator to examine the wavelength shift for temperature resolution. A FBG temperature sensor is also needed to design a module to transfer the temperature to the strain. Thus, how to separate the strain with temperature is somehow a key point for the scheme. A similar thing also happens with Fabry–Perot temperature sensors [

10].

The machine vision [

6] method can measure temperature distribution in a large area in a remote way. It can determine the temperature field around a ground settlement (GS) sensor. However, the cylindrical structure of the oil tank requires at least three machine vision systems to cover all the surrounding GS sensors, and this leads to installation trouble.

Fluorescent fiber-optic temperature sensors [

7] is usually used for high-temperature measurement, even if it is also suitable for liquid temperature measurement.

Infrared [

8] and radiation temperature sensors [

9] are both non-contact sensors. As a remote method, they are able to measure temperature through an optical fiber, but they still need a separate interrogator.

On the other hand, temperature measurement is usually a topic accompanying with strain measurement in the distributed physical measurement [

2], FBG [

5], etc. And their cross-sensitivity of temperature with strain is a hot topic among these approaches [

11]. It means that temperature and strain are coupled together in these schemes. However, there is no publication to report a temperature measure by using a technique of low-coherent optical interferometer (LCOI), although it has been widely employed for the long-gauge strain measurement. A difficulty in developing a temperature sensor in the principle of LCOI is due to the lack of a high-stability in-fiber mirror to carry out a half-reflection of the light [

12,

13], by which a specific length of the sensing arm in Michelson configuration can be confined effectively. A similar problem can be found in the distributed situation, in which the width of an optical pulse is employed to control its spatial resolution [

14]. One approach was polishing the sensing fiber ends at a right angle and coat them with a thin layer of silver for a reflectivity of 4% to form a partial reflection. This scheme can carry out a quasi-distributed strain sensor in the principle of LCOI. However, it is difficult to configure it as a temperature sensor, due to hysteresis [

12].

A GS sensor in the principle of LCOI has been developed for non-uniform GS monitoring of large-storage oil tanks [

15]. In that case, the non-uniform temperature field exists surrounding a cylindrical structure of oil tanks, around which the solar irradiation will create a sunlit front and shadow around the tank. In the summer, their temperature differences can exceed over 30 °C [

16]. This requires a GS sensor to possess a good temperature performance in order to compare the GS data both from the sunlit front and shadow in an equal accuracy. Thus, to design a temperature sensor in the principle of LCOI becomes necessary in order to implement a corresponding compensation algorithm for the GS sensor. This is also the requirement for fireproofing in the petrochemical industry [

16].

This paper proposed an all-optic temperature sensor in the principle of LCOI. Its sensing arm was fabricated into a spring in order to obtain an expected Young’s modulus for temperature sensing in a thermoelastic way. This design can not only firstly implement a temperature sensor in the principle of LCOI but also share one interrogator with the GS sensor. The experimental results proved that this design could obtain an absolute temperature measuring accuracy of ±1.16 , and the sensitivity was 0.34 °C with a verification of a platinum resistance temperature sensor (PT-100). Therefore, the temperature and GS measurement can be integrated into one LCOI-based interrogator, and a compact instrumentation can be expected.

2. Design of a Spring Temperature Sensor Based on a LCOI

2.1. The Principle of a LCOI

A LCOI was configured as given in

Figure 1. The system employed a low-coherence broadband light source, a super-luminescent emitting diode (SLED), with a central wavelength at 1310 nm and a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 45 nm. The coherence length of this source was limited to several tens of micrometers. The interference occurs only when the optical path difference between the reference arm and the sensing arm lies within this coherence length.

The principle of the LCOI given in

Figure 1 was that the broadband light emitted from a SLED passed through the first circulator and about half of the energy was reflected by a half-reflection mirror A. Then, it was coupled into the second circulator and projected onto the second half-reflection mirror C and total-reflection mirror D successively, thereby correspondingly forming Path 1 and Path 3. The other half of the energy passed through the half-reflection mirror A, reflected by the total-reflection mirror B, then went the same way to C and D and formed Path 2 and Path 4 one after another. The four paths were summarized in

Table 1.

Among them, Path 2 served as a reference arm and Path 3 as a sensing arm, while Path 1 and Path 4 represented the shortest and longest paths among all the four, respectively.

The LCOI is in a Michelson configuration, and the output interference signal reaches its maximum intensity only when the optical path difference (OPD) of the sensing arm, Path 3, along with reference arm, Path 2, tends to zero. This is because the wide spectrum of the SLED bears a short coherent length of approximately 38.14

here [

15]. The OPD was controlled through the moving stepping motor, and the position of the stepper motor is used to measure the OPD. According to Equation (4) in Ref. [

15], this output interference signal detected by PD can be described as

where

denotes the real part of the complex degree of coherence

;

and

represent the optical intensity from the two interference paths, respectively; then, the low-coherent interference signal can be detected by the PD and processed in the following data-processing part.

represents the length of Path 2,

is the length of Path 3, and

is the OPD between Path 2 and Path 3. In practice, the reference arm,

, was packaged in a well temperature-isolated chamber to keep its length stable, so the changes in OPD was determined by the sensing arm,

. After being divided by the initial length of the sensing arm

, the strain variations in sensing arm can be expressed as a function of temperature:

where α is the thermal expansion coefficient of the spring material, stainless here. We determined it by experimental data.

In contrast, the other two OPDs, and , are far beyond the coherence length of the light source, and thus they cannot interfere.

When temperature is being changed, the stainless-steel spring undergoes a thermal expansion or contraction, and results in a change in the optical length of sensing arm,

. The stepping-motor drives the total-reflection mirror B to adjust the length of the reference arm to find where the OPD of Path 2 and Path 3 equals to zero. After which, we recorded the locations of the stepping-motor as a measure of the OPD and compared it with temperature through a calibration procedure. All the regions in

Figure 1 apart from the marked red line were insensitive to the results. Thus, this sensor possessed good stability and was quite suitable for the measurement of a quasi-static variable.

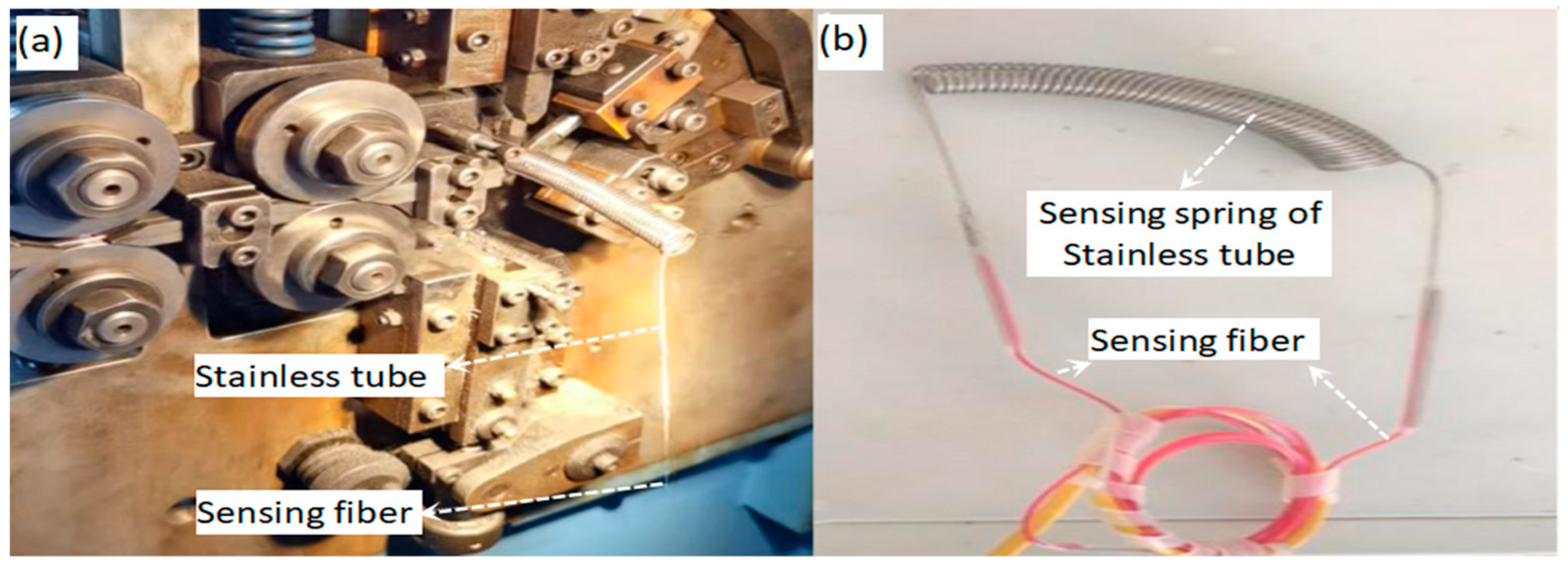

2.2. The Fabrication of a Spring Sensor

In order to design a temperature sensor with a low hysteresis, the sensing fiber was configured into a spring structure. This can guarantee an all-optic passive temperature sensing. This feature provides an intrinsic safety mechanism and makes the sensor the preferred option for petrochemical industry applications.

The spring sensor was made of a stainless tube threaded with the sensing arm,

. The stainless tube had an outside diameter of 1 mm and inner diameter of 0.4 mm; thus, it matched well with the outside diameter, at 0.25 mm, of the sensing arm optical fiber. The fiber was an anti-bending, single-mode optical fiber G657.A2, bearing a minimum bending radius of 7.5 mm. After a 3.5-m-long optical fiber being threaded through a 3-m-long stainless tube bonded with epoxy resin at two ends of the tube, as shown in

Figure 2a, a coiling machine was operated to make it into a spring, as shown in

Figure 2b, which served as an all-optic temperature sensor. The final size of the spring had a length of about 70 mm and an outside diameter of 13 mm, which satisfies the bending diameter of fiber G657.A2, say 15 mm (7.5 × 2 = 15 mm).

One of the advantages of this spring sensor is its passive all-optic property. And the stainless tube is suitable to measure the temperature of liquid or silicone oil, etc. The strain generated by the spring is less dependent on the deformation in its physical shape, so it is possible to be transformed to match a space where the sensor to be installed, thus keeping its sensitivity determined by thermoelastic effect.

The spring was made of stainless steel for like environmental compatibility. A calculation based on the thermoelastic property of stainless steel had been carried out. The results were discussed in the Conclusion (

Section 4).

2.3. Data-Processing Part

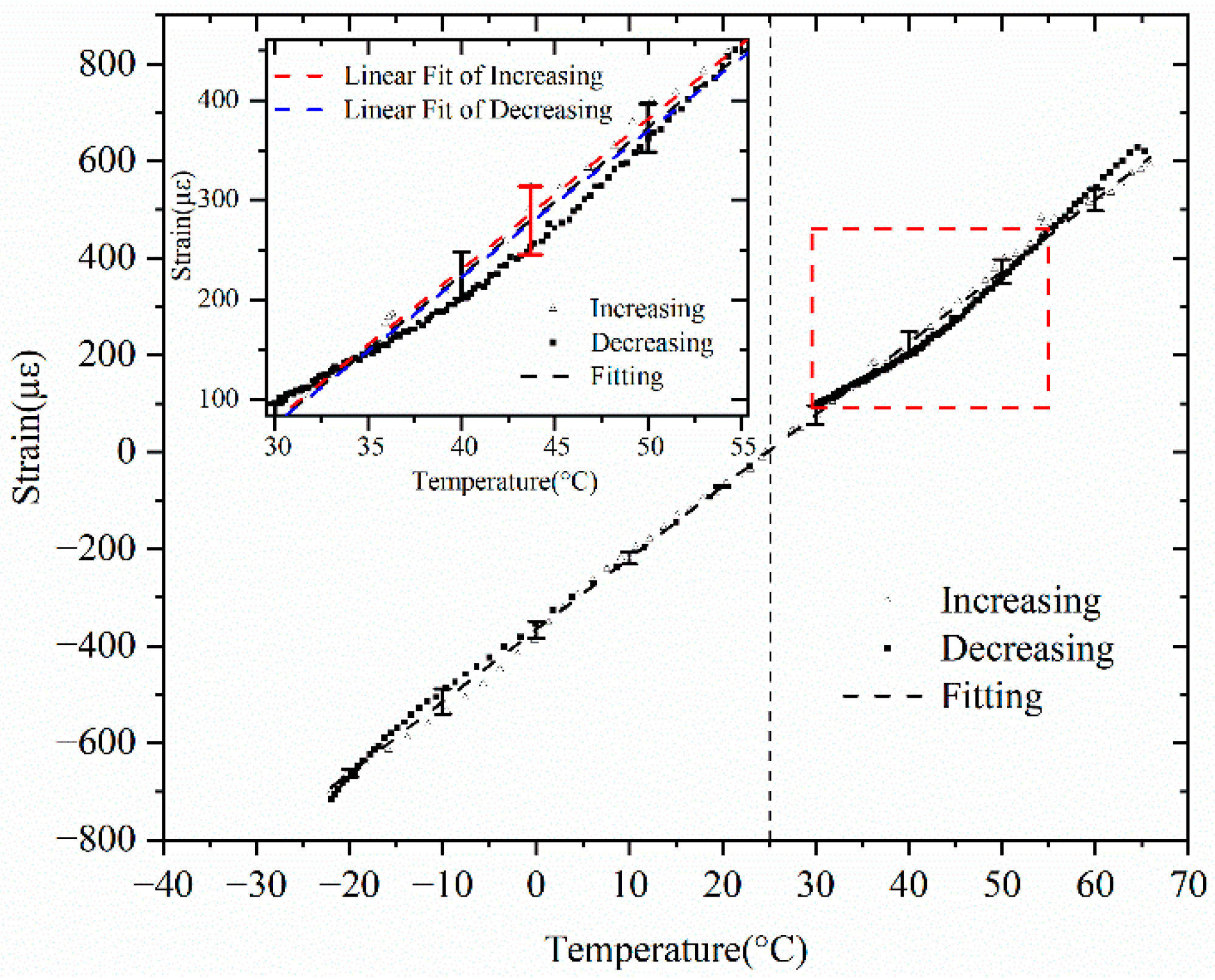

The data-processing part was mainly to convert the optical interferometric fringe signal into electric information and calibrate the environmental temperature variations into the strain determined by the thermoelastic effect, such as thermal expansion or contraction. During the calibration experiment, the interference fringes generated from the optical interferometer were simultaneously recorded, with the temperature measured by a commercial Pt-100. In this way, two datasets were collected: the central peak of interference fringe displacement (in micrometers) and the corresponding temperature.

The interference fringe displacement was normalized and represented as the strain by dividing it by the sensing fiber length of 3.5 m, and it was then expressed in microstrain (με). By plotting the measured strain as a function of the actual temperature, a linear fitting curve was obtained. The slope of the fitted line represented the sensitivity of the sensor, which provided the conversion coefficient between strain and temperature.

After being calibrated, the spring sensor can be directly applied in the petrochemical industry, such as oil tank GS monitoring. When the spring sensor was placed in the field, only the interferometric displacement needed to be measured. The corresponding temperature was able to be calculated from the established linear relationship, realizing an all-optical detection scheme without any electrical dangers.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

An intrinsic spring temperature sensor was designed and fabricated. The calibration results demonstrated its effectiveness. The sensitivity based on the calibrated curve given in

Figure 4 was 14.78 με/°C, from which the temperature sensitivity was able to be estimated as 0.34 °C. This result was determined by the resolution of the interrogator, which was 5 με in our experiment and was determined by the accuracy of the stepping motor given in

Figure 1.

According to the theory of thermoelasticity, the Duhamel–Neumann relation [

17] is known as

where

is the strain tensor,

is the compliance tensor (inverse of the stiffness tensor

),

is the stress tensor,

is the thermal expansion tensor, and

is the temperature change.

For Equation (3), the equivalent form [

18] can be derived as

where

is Young’s modulus of the material,

is Poisson’s ratio,

is the thermal expansion coefficient,

are Kronecker deltas.

When thermally exposed to a free stainless tube that has no external mechanical limitations, stresses do not occur in the material, but a linear strain is observed, proportional to the temperature change. This effect can be described by the thermoelasticity equation in the form of , where is the coefficient of linear thermal expansion of the stainless tube, and is the initial tube length ( m at in the experiment with heating, and in the experiment with cooling). In the absence of fasteners, the tube deforms freely, which eliminates the appearance of internal stresses, despite the presence of thermal deformation.

The maximum hysteresis error was 2.31 (±1.16 ) between the temperature increases and decreases.

For the increasing process, , where °C, µm/(m·°C).

For the decreasing process, , where = 28.25 , α = 14.65 µm/(m·). Thus, the fitting of calibration curve turns out as , where = 28.22 °C and α = 14.78 µm/(m·°C) are the fitting parameters.

Of course, there are nonlinear effects, since thermoelastic expansion must lead to friction, local clamping, or even micro-sliding between the fiber and the inner surface of the tube. Additionally, the result of full thermoelastic derivation depends on the spring geometry (wire diameter, coil radius, number of turns, etc.). It also depends on the mechanical transfer factor between tube expansion and inner fiber strain, effects of coil deformation, axial stiffness, or friction between the fiber and inner tube. However, our experiments have shown that both heating and cooling nonlinear effects lead to deviations of no more than 0.19% of the measured optical path length from the calculated linear approximation. This is sufficient accuracy for our purposes.

This work presented a design and fabrication of an all-optic temperature spring sensor. The experimental test demonstrated that the proposed spring sensor could carry out temperature measurement and provided a possibility to carry out a GS of oil tank measurement with fine temperature compensation. This provided a reference for future intrinsic sensor development.

For further optimization, we will focus on two key aspects:

The first is to improve temperature resolution. We will systematically modify the spring structure parameters (e.g., diameter, pitch, and number of coils) through iterative testing to identify the optimal configuration that maximizes strain output per unit temperature change.

The second is to reduce hysteresis. We will implement a continuous or multi-point bonding technique along the fiber-tube interface to minimize micro-slip and ensure more uniform strain transfer.

The third is choosing an optical fiber with a low stress birefringence. Even if an optical fiber can be a good strain material by acting as a basis of FBG, for example, when it is being coiled along with the spring, a low-stress-birefringence fiber should be preferred. In the future, we can separate this effect by using a specifically designed optical scheme. A long-term field validation of both its durability and reliability is also an on-going work.