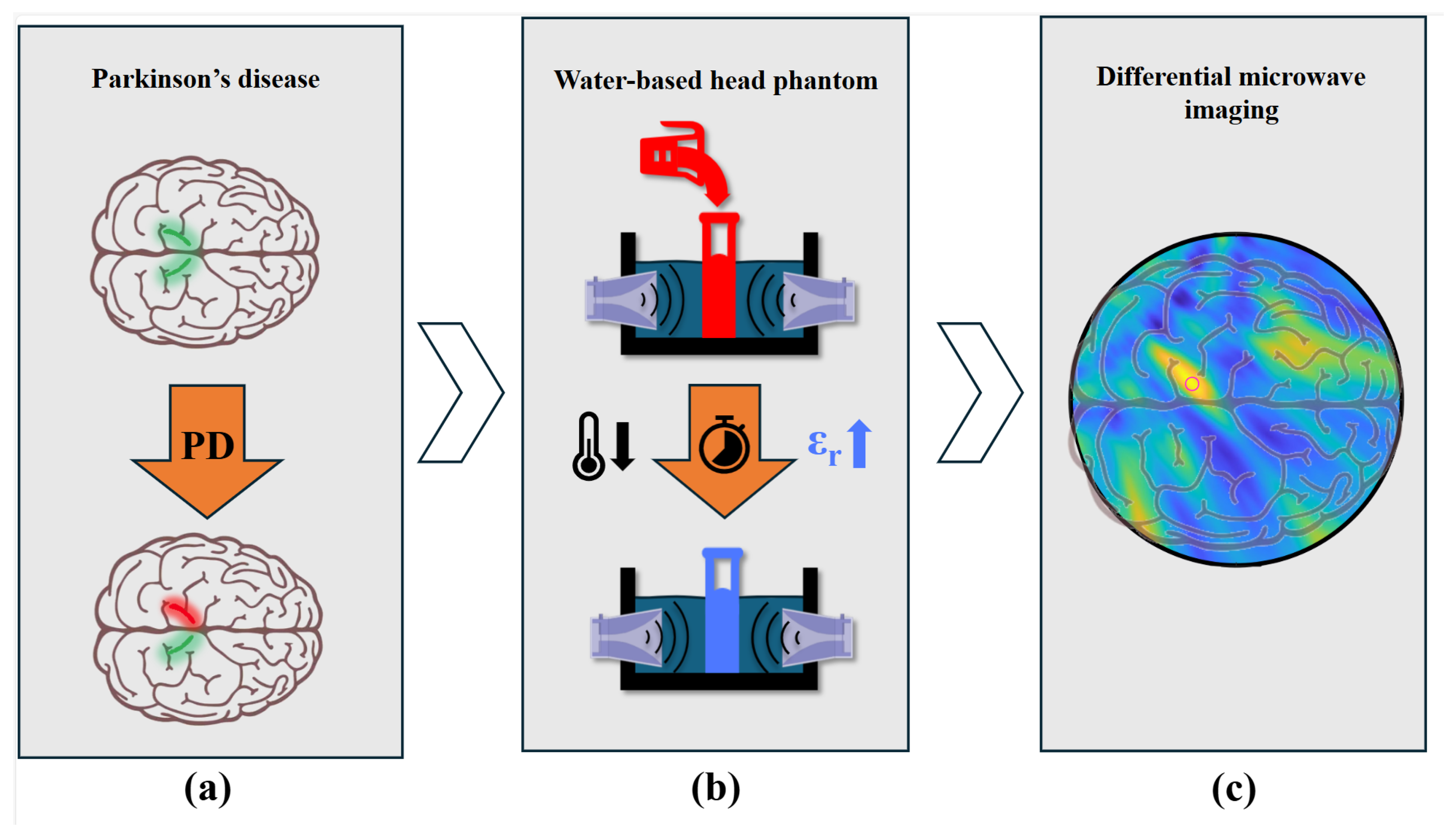

Microwave Imaging for Parkinson’s Disease Detection: A Phantom-Based Feasibility Study Using Temperature-Controlled Dielectric Variations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Parkinson’s Disease

1.2. Diagnostic Techniques

1.3. Microwave Imaging for Parkinson’s Disease

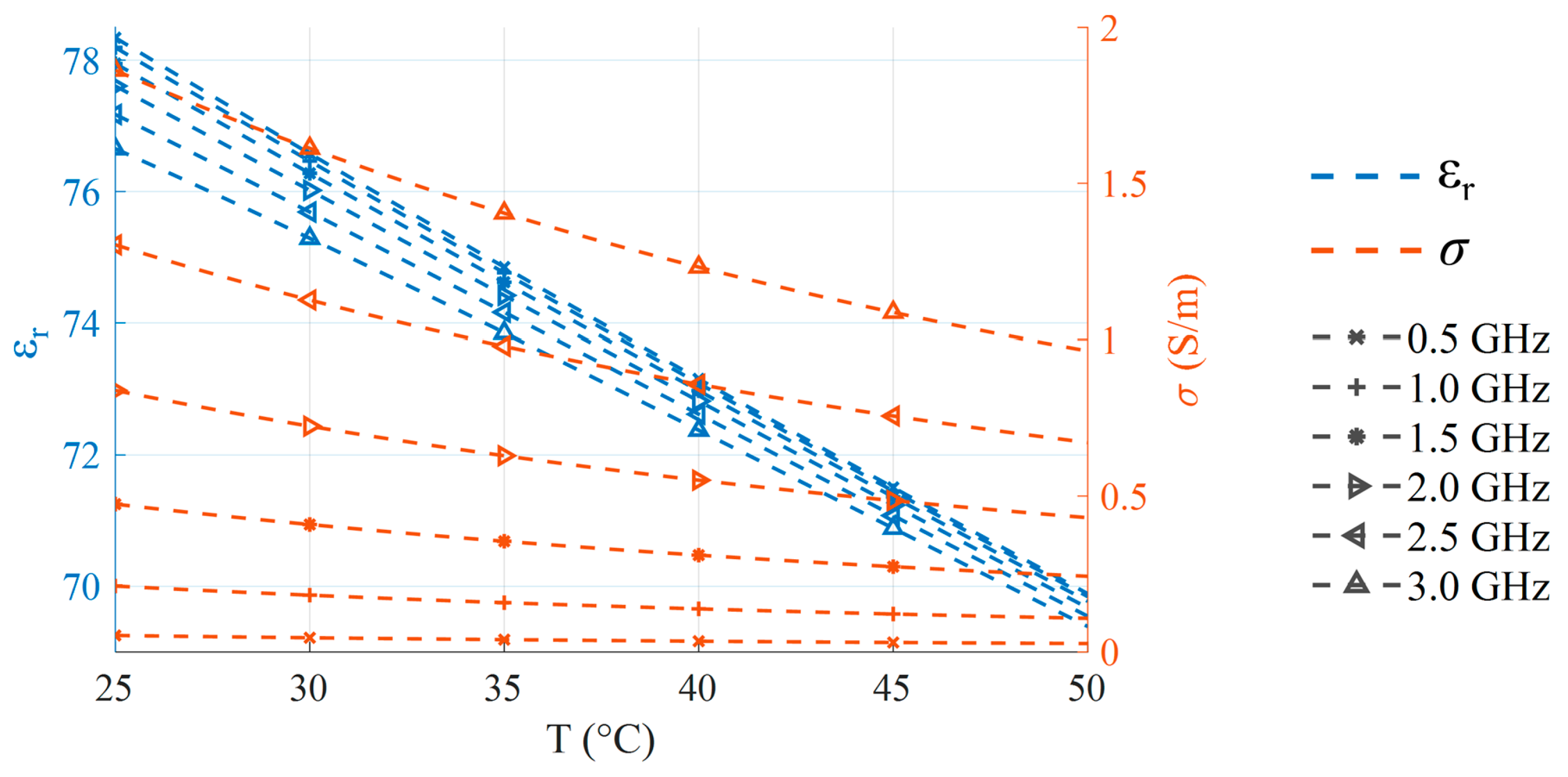

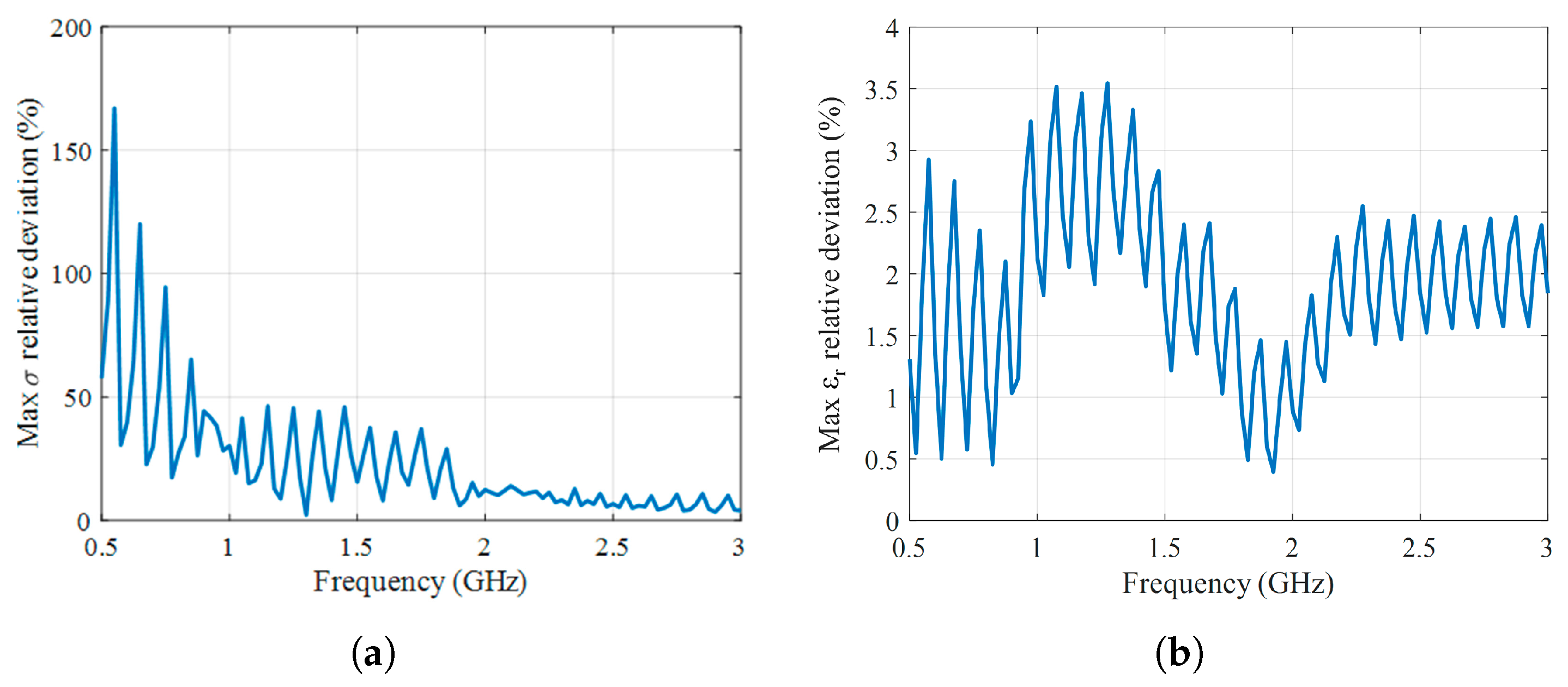

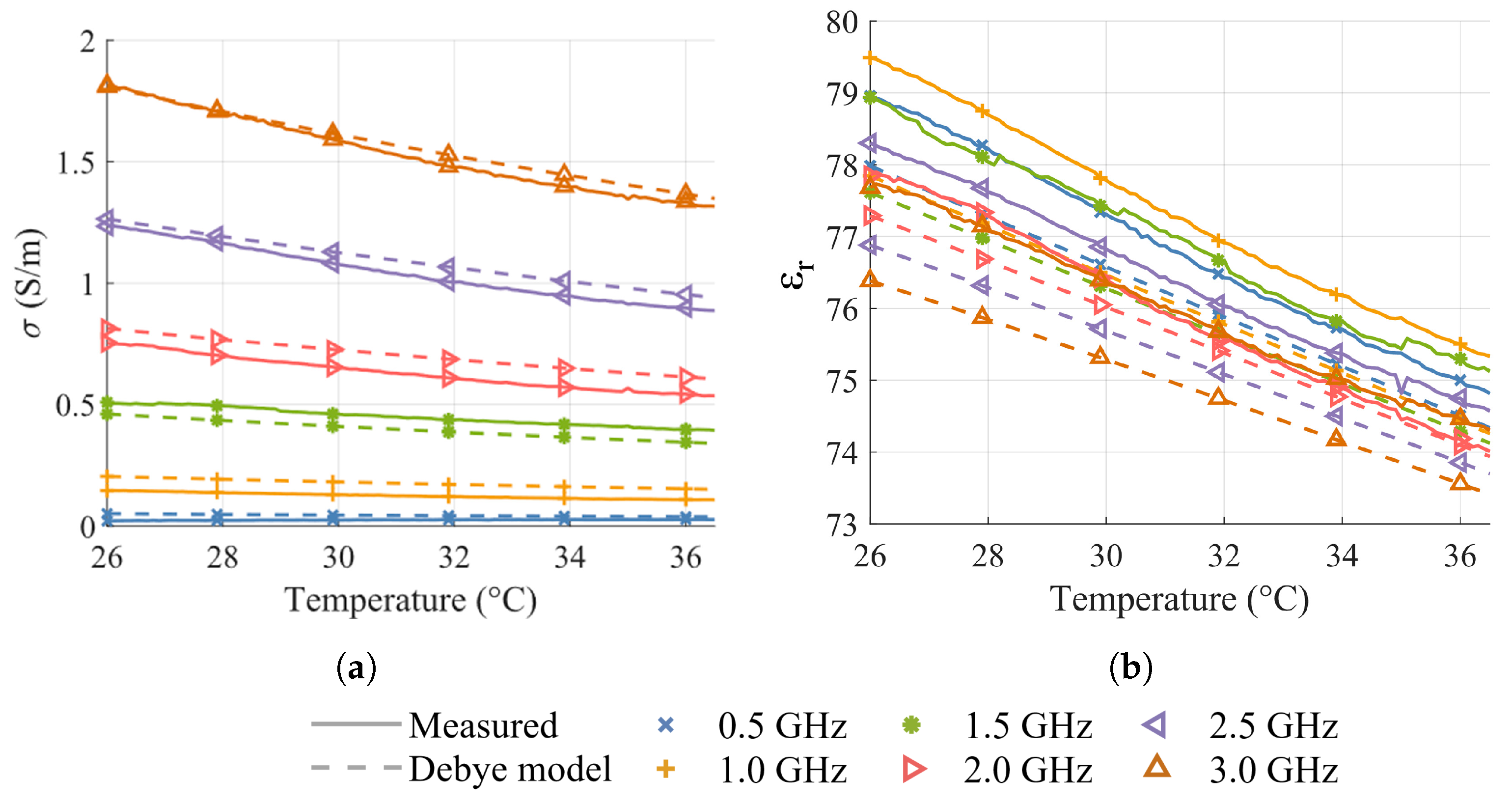

2. Temperature-Dependent Dielectric Characterization

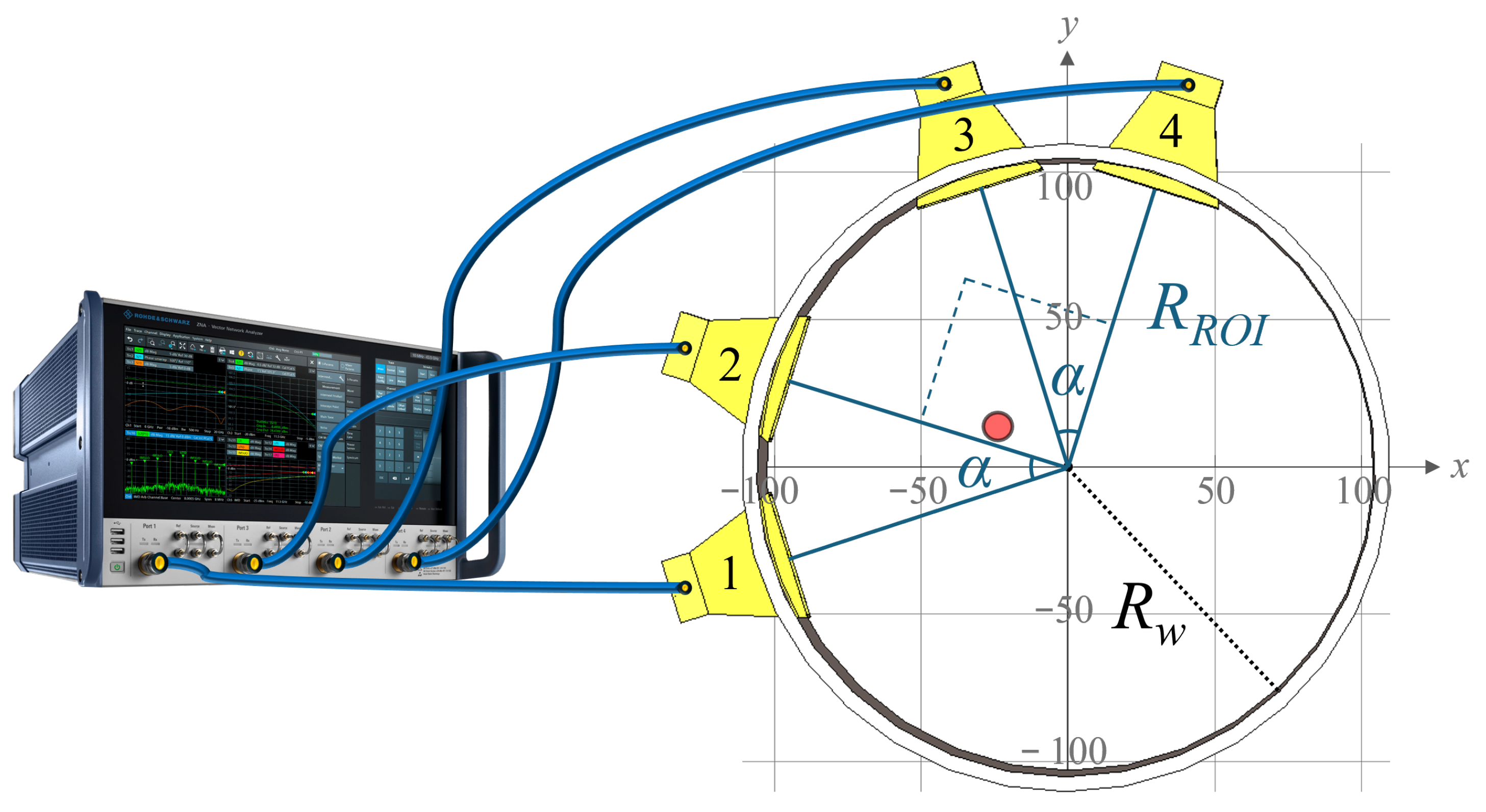

3. Microwave Imaging System

3.1. System Overview

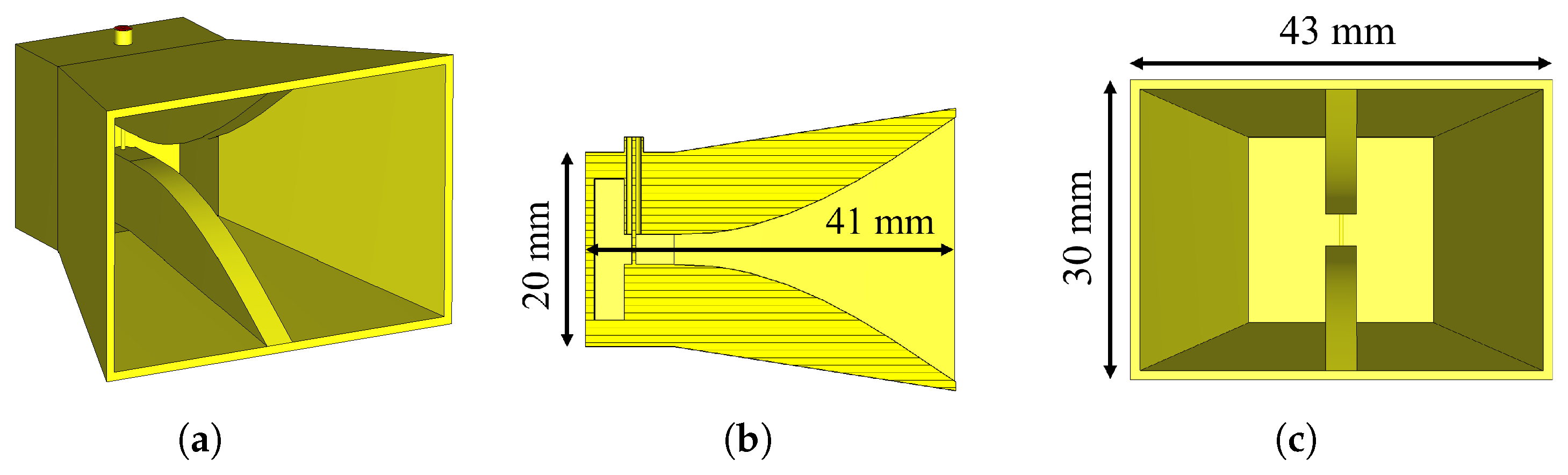

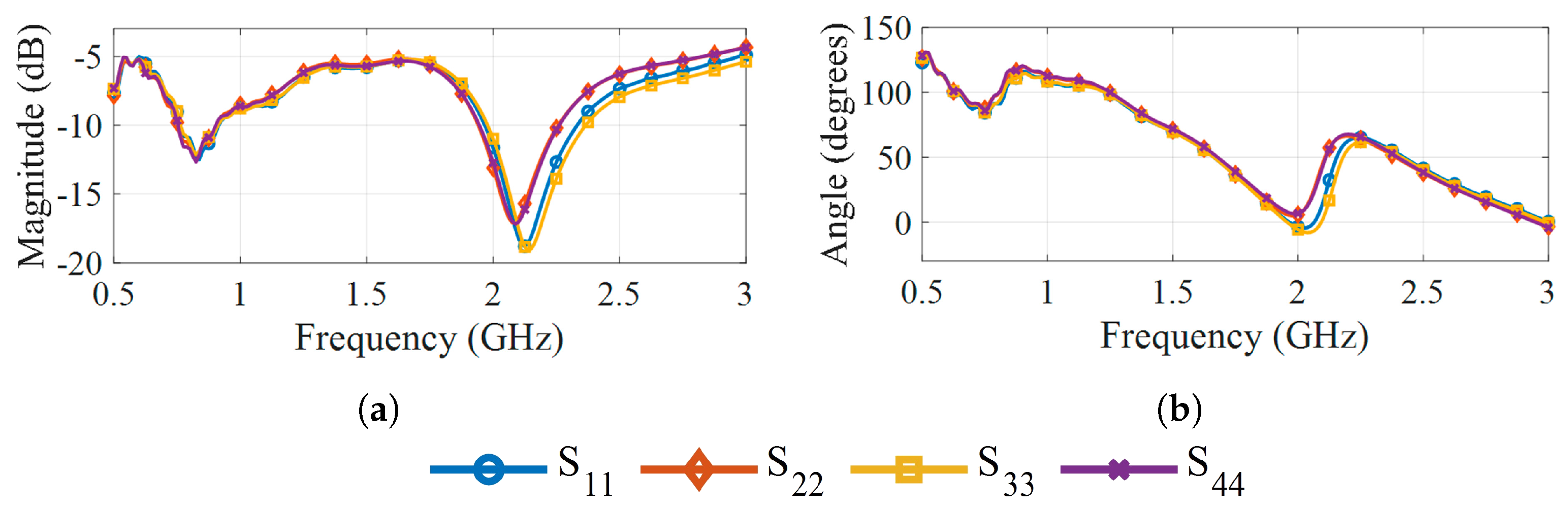

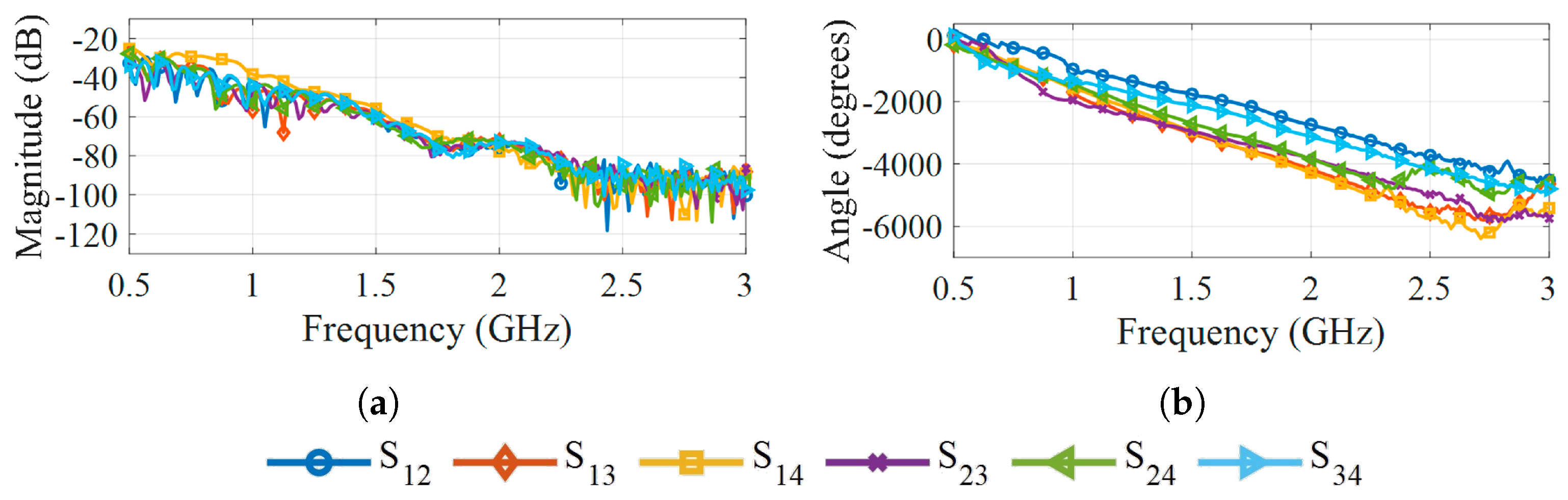

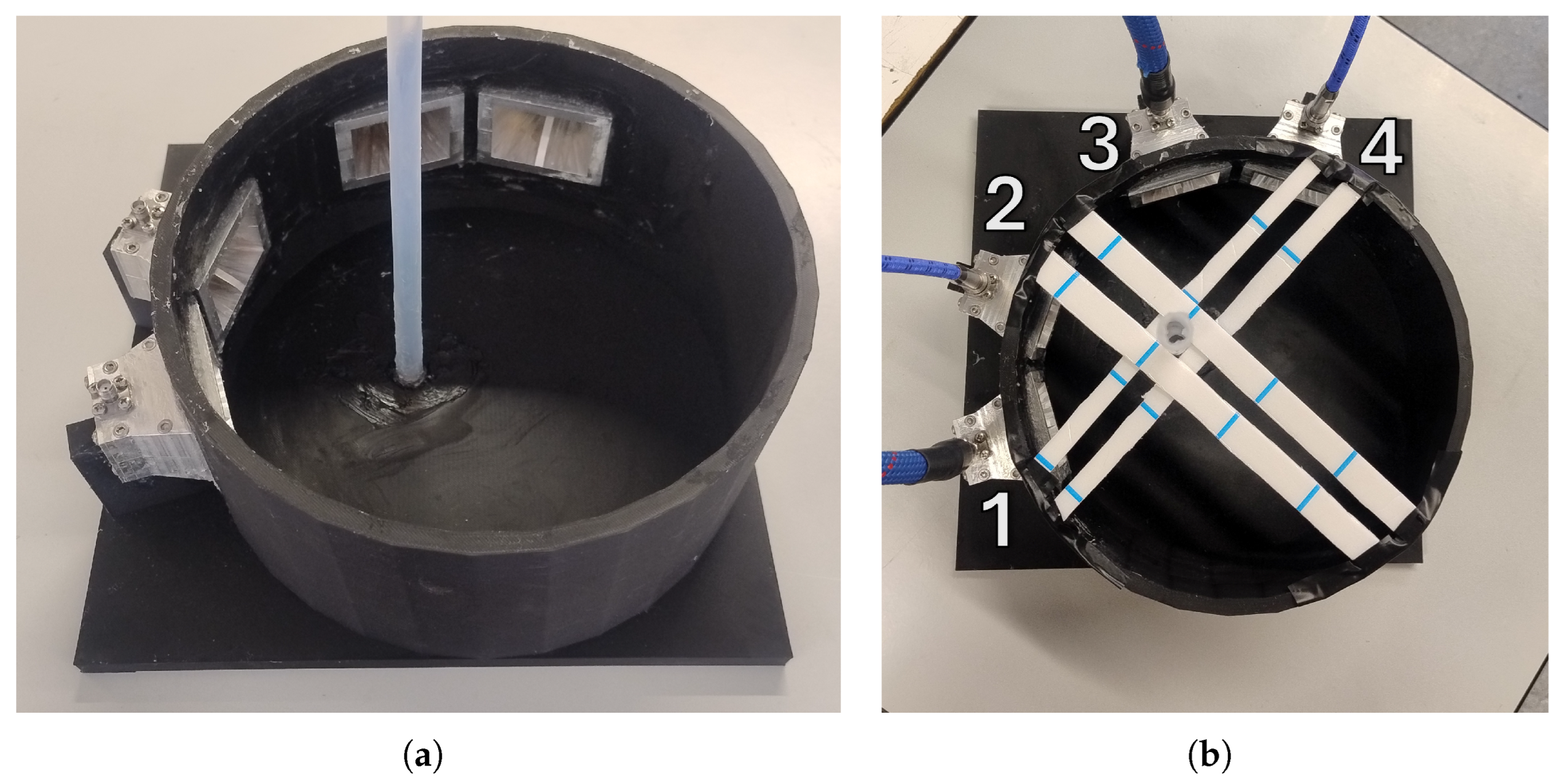

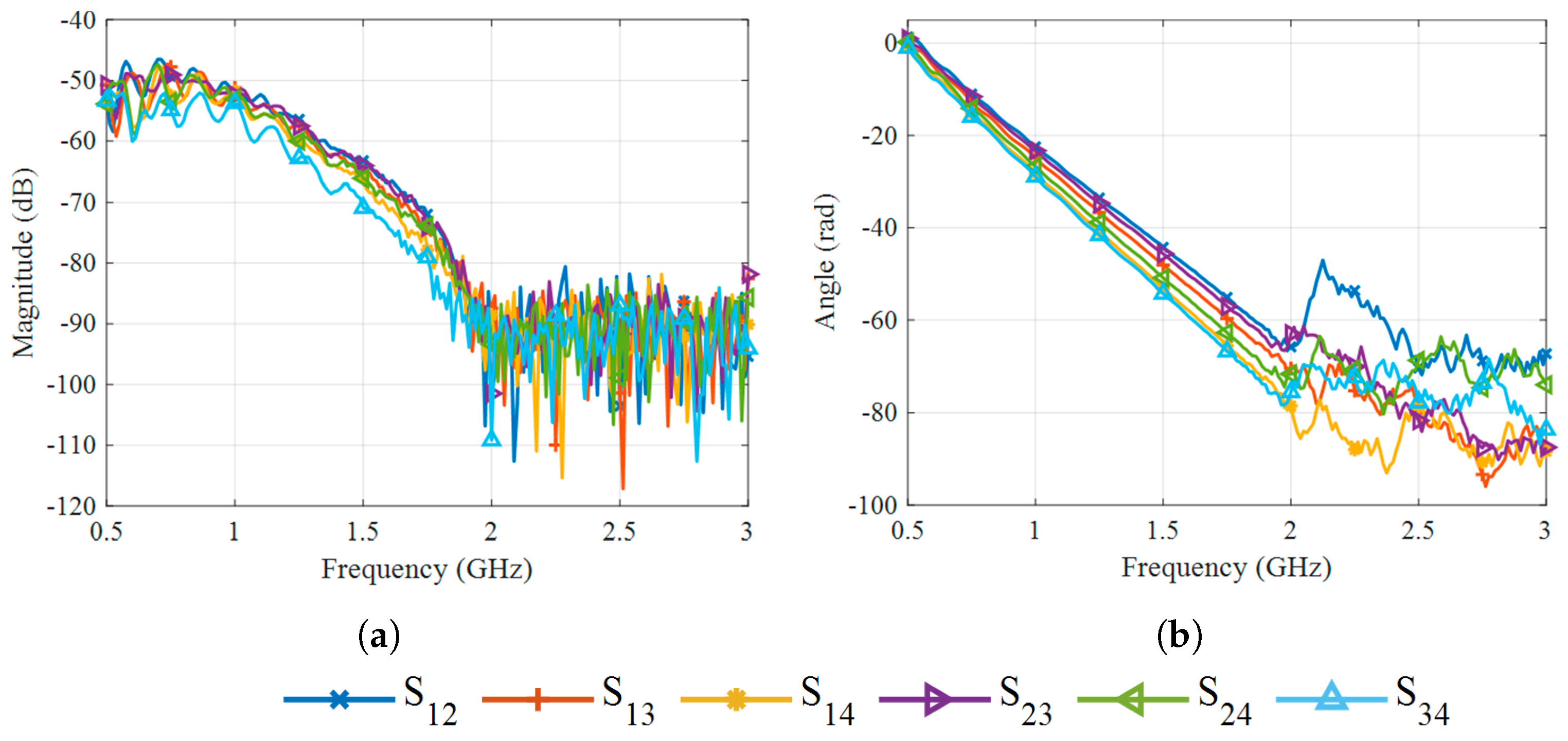

3.2. Antennas

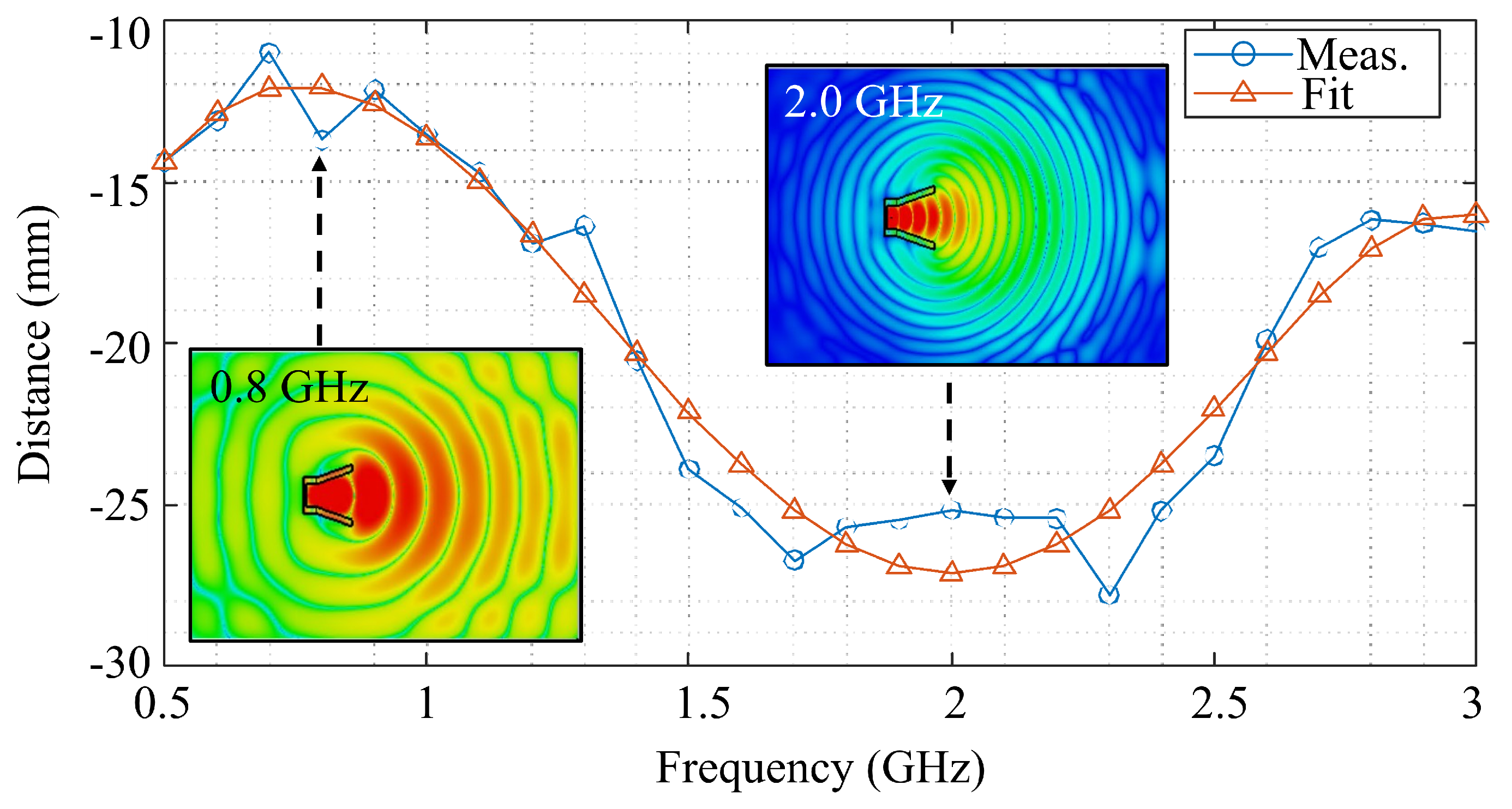

3.3. Reconstruction Algorithm

4. Experimental Assessment

4.1. The Phantom

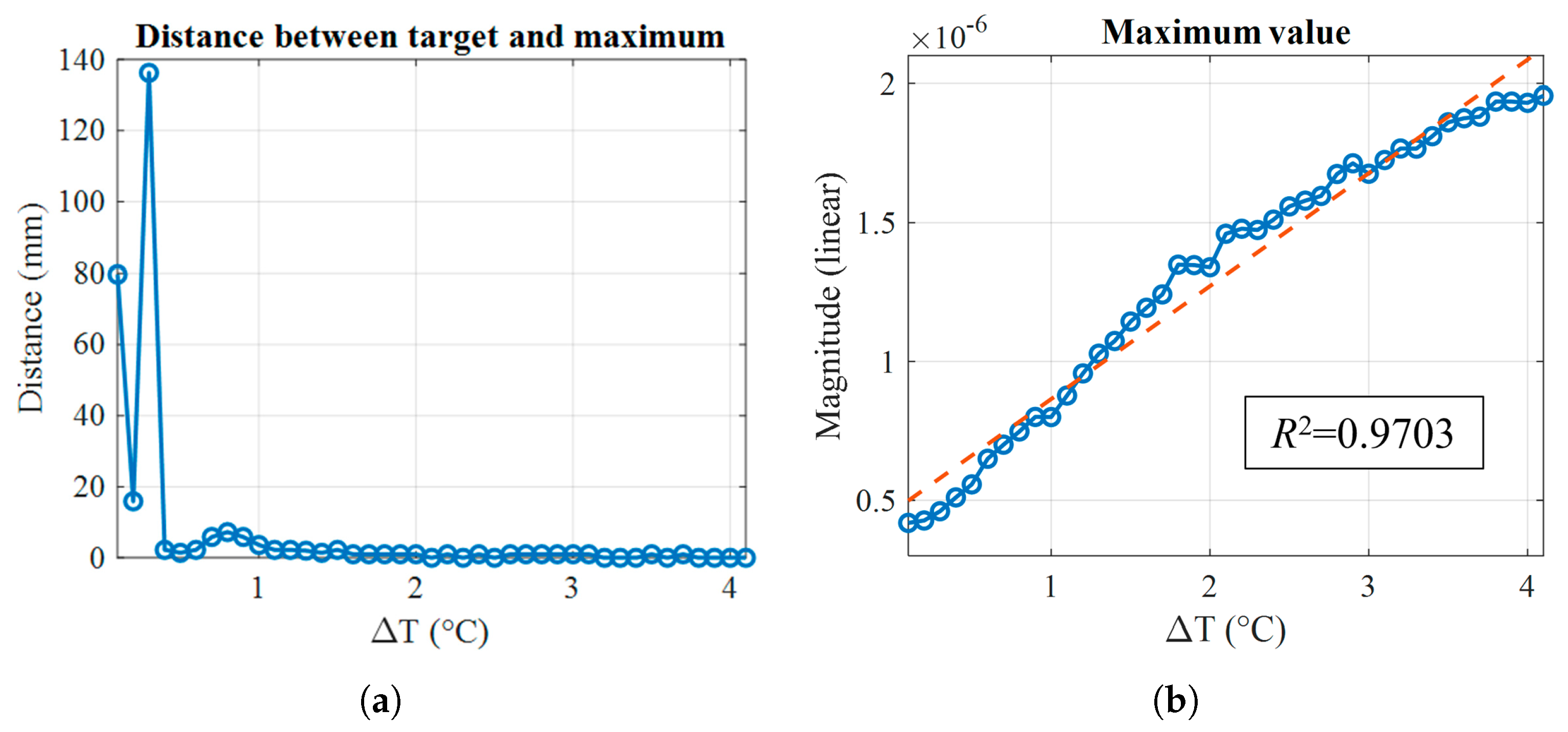

4.2. Thermal Analysis

4.3. Measurement Protocol

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DaT-SPECT | Dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography |

| EGRH | Extended gap ridge horn |

| FDM | Fused deposition modeling |

| IMUs | Inertial measurement units |

| MFBF | Multi-frequency bi-focusing |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MWI | Microwave imaging |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PET | Photon emission tomography |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| SNpc | Substantia nigra pars compacta |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| SWR | Standing wave ratio |

| VNA | Vector network analyzer |

References

- Yamashita, K.Y.; Bhoopatiraju, S.; Silverglate, B.D.; Grossberg, G.T. Biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease: A state of the art review. Biomark. Neuropsychiatry 2023, 9, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkali, A.; Thomas, G.E.; Zetterberg, H.; Weil, R.S. Neuroimaging and fluid biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease in an era of targeted interventions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubignat, M.; Tir, M.; Krystkowiak, P. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease from pathophysiology to early diagnosis. Rev. Méd. Interne 2021, 42, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demailly, A.; Moreau, C.; Devos, D. Effectiveness of continuous dopaminergic therapies in Parkinson’s disease: A review of L-DOPA pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. J. Park. Dis. 2024, 14, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regensburger, M.; Ip, C.W.; Kohl, Z.; Schrader, C.; Urban, P.P.; Kassubek, J.; Jost, W.H. Clinical benefit of MAO-B and COMT inhibition in Parkinson’s disease: Practical considerations. J. Neural Transm. 2023, 130, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, M.L.; Meystedt, J.C.; Turchan, M.; Cannard, K.R.; Harper, K.; Fan, R.; Ye, F.; Davis, T.L.; Konrad, P.E.; Charles, D. Eleven-year outcomes of deep brain stimulation in early-stage parkinson disease. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2023, 26, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Chiu, R.; Lee, J. Parkinson disease primer, part 2: Management of motor and nonmotor symptoms. Can. Fam. Physician 2023, 69, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolosa, E.; Garrido, A.; Scholz, S.W.; Poewe, W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, U.; Lang, A.E.; Masellis, M. Neuroimaging advances in Parkinson’s disease and atypical Parkinsonian syndromes. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 572976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujral, J.; Gandhi, O.H.; Singh, S.B.; Ahmed, M.; Ayubcha, C.; Werner, T.J.; Revheim, M.E.; Alavi, A. PET, SPECT, and MRI imaging for evaluation of Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 14, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burade, A.; Dagher, R.; Kaviani, P.; Lakhani, D.A.; Sair, H.I.; Luna, L.P. Comparative Diagnostic Efficacy of Neuromelanin MRI vs. Dopamine Transporter (DAT) imaging in Parkinson’s disease: A Systematic Review. Park. Relat. Disord. 2025, 137, 107898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, A.D.; Binzer, M.; Stenager, E.; Gramsbergen, J.B. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for P arkinson’s disease—A systematic review. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2017, 135, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.C.; Lu, C.H.; Chiu, P.Y.; Yang, S.Y. Plasma total α-synuclein and neurofilament light chain: Clinical validation for discriminating Parkinson’s disease from normal control. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2020, 49, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadalti, C.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Baiardi, S.; Mastrangelo, A.; Rossi, M.; Zenesini, C.; Giannini, G.; Candelise, N.; Sambati, L.; Polischi, B.; et al. Neurofilament light chain and α-synuclein RT-QuIC as differential diagnostic biomarkers in parkinsonisms and related syndromes. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hällqvist, J.; Bartl, M.; Dakna, M.; Schade, S.; Garagnani, P.; Bacalini, M.G.; Pirazzini, C.; Bhatia, K.; Schreglmann, S.; Xylaki, M.; et al. Plasma proteomics identify biomarkers predicting Parkinson’s disease up to 7 years before symptom onset. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, L.B.; Calil, B.C.; da Silva, A.P.S.P.B.; Dionísio, V.C.; Vieira, M.F.; de Oliveira Andrade, A.; Pereira, A.A. Discrimination between healthy and patients with Parkinson’s disease from hand resting activity using inertial measurement unit. Biomed. Eng. Online 2021, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou, L.; Peters, J.; Wong, E.; Akers, R.; Dossou, M.S.; Sosnoff, J.J.; Rice, L.A. Gait and balance assessments using smartphone applications in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Med. Syst. 2021, 45, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.M.; Mahgoub, I.; Du, E.; Leavitt, M.A.; Asghar, W. Advances in healthcare wearable devices. npj Flex. Electron. 2021, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.; Rouaud, T.; Grabli, D.; Benatru, I.; Remy, P.; Marques, A.R.; Drapier, S.; Mariani, L.L.; Roze, E.; Devos, D.; et al. Overview on wearable sensors for the management of Parkinson’s disease. npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Chen, Y.; LeWitt, P.A.; Yan, F.; Haacke, E.M. Application of neuromelanin MR imaging in Parkinson disease. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 57, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Li, D.; Tian, Y.; Li, R.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Yin, X. Hybrid PET-MRI for early detection of dopaminergic dysfunction and microstructural degradation involved in Parkinson’s disease. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, Ü.Ö.; Bora, H.A.T.; Atay, L.Ö. Dopamine transporter spect imaging in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsoniandisorders. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fear, E.; Stuchly, M. Microwave detection of breast cancer. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2000, 48, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, M.; Capdevila, S.; Romeu, J.; Jofre, L. 3-D microwave magnitude combined tomography for breast cancer detection using realistic breast models. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2012, 11, 1622–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, M.R.; Vacca, M.; Tobon, J.A.; Pulimeno, A.; Sarwar, I.; Solimene, R.; Vipiana, F. A COTS-based microwave imaging system for breast-cancer detection. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2017, 11, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaeebi, M.A.; Alzoubi, K.; Almoneef, T.S.; Bamatraf, S.M.; Attia, H.; Ramahi, O.M. Review of microwaves techniques for breast cancer detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.P.; Dey, M.; Loretoni, R.; Duranti, M.; Ghavami, M.; Dudley, S.; Tiberi, G. Radiation-free microwave technology for breast lesion detection using supervised machine learning model. Tomography 2023, 9, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhager, A.; Candefjord, S.; Elam, M.; Persson, M. Microwave diagnostics ahead: Saving time and the lives of trauma and stroke patients. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2018, 19, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Origlia, C.; Vasquez, J.A.T.; Scapaticci, R.; Crocco, L.; Vipiana, F. Experimental assessment of real-time brain stroke monitoring via a microwave imaging scanner. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 2022, 3, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Alqadami, A.S.M.; Abbosh, A. Stroke Diagnosis Using Microwave Techniques: Review of Systems and Algorithms. IEEE J. Electromagn. Microwaves Med. Biol. 2023, 7, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inum, R.; Rana, M.M.; Shushama, K.N.; Quader, M.A. EBG based microstrip patch antenna for brain tumor detection via scattering parameters in microwave imaging system. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2018, 2018, 8241438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, A.; Islam, M.T.; Beng, G.K.; Kashem, S.B.A.; Soliman, M.S.; Misran, N.; Chowdhury, M.E. Microwave brain imaging system to detect brain tumor using metamaterial loaded stacked antenna array. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Dong, Y.; Arslan, T.; Chandran, S. A Machine Learning-Based Classification Method for Monitoring Alzheimer’s Disease Using Electromagnetic Radar Data. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2023, 71, 4012–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhatullah; Chen, X.; Zeng, D.; Ullah, R.; Nawaz, R.; Xu, J.; Arslan, T. A deep learning approach for non-invasive Alzheimer’s monitoring using microwave radar data. Neural Netw. 2024, 181, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, L.; Mariano, V.; Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Tobón Vasquez, J.A.; Scapaticci, R.; Crocco, L.; Vipiana, F. Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease via Machine Learning-Based Microwave Sensing: An Experimental Validation. Sensors 2025, 25, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazzim, Y.; Arias, C.P.; Jofre, M.; Mrabet, O.E.; Romeu, J.; Jofre-Roca, L. UWB microwave functional brain activity extraction for Parkinson’s disease monitoring. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 24, 3844–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origlia, C.; Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Tobon Vasquez, J.A.; Bolomey, J.C.; Vipiana, F. Review of microwave near-field sensing and imaging devices in medical applications. Sensors 2024, 24, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzicchia, E.; Lu, P.; Guo, W.; Karadima, O.; Sotiriou, I.; Ghavami, N.; Kallos, E.; Palikaras, G.; Kosmas, P. Metasurface-Enhanced Antennas for Microwave Brain Imaging. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolomey, J.C.; Jofre, L.; Peronnet, G. On the possible use of microwave-active imaging for remote thermal sensing. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2003, 31, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, L.; Aldana, R.; Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Tobon-Vasquez, J.A.; Vipiana, F.; Jofre-Roca, L. Differential Permittivity Modeling in Biological Phantoms via Water Temperature Control. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced Applications (ICEAA), Palermo, Italy, 8–12 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kaatze, U. Complex permittivity of water as a function of frequency and temperature. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1989, 34, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bucchianico, A. Coefficient of determination (R 2). In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Quality and Reliability; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keysight Technologies. N9918A FieldFox Handheld Microwave Analyzer, 26.5 GHz. Available online: https://www.keysight.com/us/en/product/N9918A/fieldfox-a-handheldmicrowave-analyzer-26-5-ghz.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Keysight Technologies. N1500A Materials Measurement Suite. 2022. Available online: https://www.keysight.com/it/en/product/N1500A/materialsmeasurement-suite.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Akazzim, Y.; El Mrabet, O.; Romeu, J.; Jofre-Roca, L. Multi-element UWB probe optimization for medical microwave imaging. Sensors 2022, 23, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akazzim, Y.; Jofre, M.; El Mrabet, O.; Romeu, J.; Jofre-Roca, L. UWB-modulated microwave imaging for human brain functional monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde & Schwarz. R&S ZNA26 Vector Network Analyzer. Available online: https://www.rohde-schwarz.com/us/products/test-and-measurement/network-analyzers/rs-zna-vector-network-analyzers_63493-551810.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rashid, S.; Jofre, L.; Garrido, A.; Gonzalez, G.; Ding, Y.; Aguasca, A.; O’Callaghan, J.; Romeu, J. 3-D printed UWB microwave bodyscope for biomedical measurements. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2019, 18, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofre, L.; Broquetas, A.; Romeu, J.; Blanch, S.; Toda, A.P.; Fabregas, X.; Cardama, A. UWB tomographic radar imaging of penetrable and impenetrable objects. Proc. IEEE 2009, 97, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonne, J.; Reddy, V.; Beato, M.R. Neuroanatomy, substantia nigra. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536995/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Frequency (GHz) | Debye (%) | Measured (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | ||

| 1.0 | ||

| 1.5 | ||

| 2.0 | ||

| 2.5 | ||

| 3.0 |

| Frequency (GHz) | Debye (%) | Measured (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | ||

| 1.0 | ||

| 1.5 | ||

| 2.0 | ||

| 2.5 | ||

| 3.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardinali, L.; Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Tobón Vasquez, J.A.; Vipiana, F.; Jofre-Roca, L. Microwave Imaging for Parkinson’s Disease Detection: A Phantom-Based Feasibility Study Using Temperature-Controlled Dielectric Variations. Sensors 2025, 25, 7562. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247562

Cardinali L, Rodriguez-Duarte DO, Tobón Vasquez JA, Vipiana F, Jofre-Roca L. Microwave Imaging for Parkinson’s Disease Detection: A Phantom-Based Feasibility Study Using Temperature-Controlled Dielectric Variations. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7562. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247562

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardinali, Leonardo, David O. Rodriguez-Duarte, Jorge A. Tobón Vasquez, Francesca Vipiana, and Luis Jofre-Roca. 2025. "Microwave Imaging for Parkinson’s Disease Detection: A Phantom-Based Feasibility Study Using Temperature-Controlled Dielectric Variations" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7562. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247562

APA StyleCardinali, L., Rodriguez-Duarte, D. O., Tobón Vasquez, J. A., Vipiana, F., & Jofre-Roca, L. (2025). Microwave Imaging for Parkinson’s Disease Detection: A Phantom-Based Feasibility Study Using Temperature-Controlled Dielectric Variations. Sensors, 25(24), 7562. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247562