Advancing Machine Learning Strategies for Power Consumption-Based IoT Botnet Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

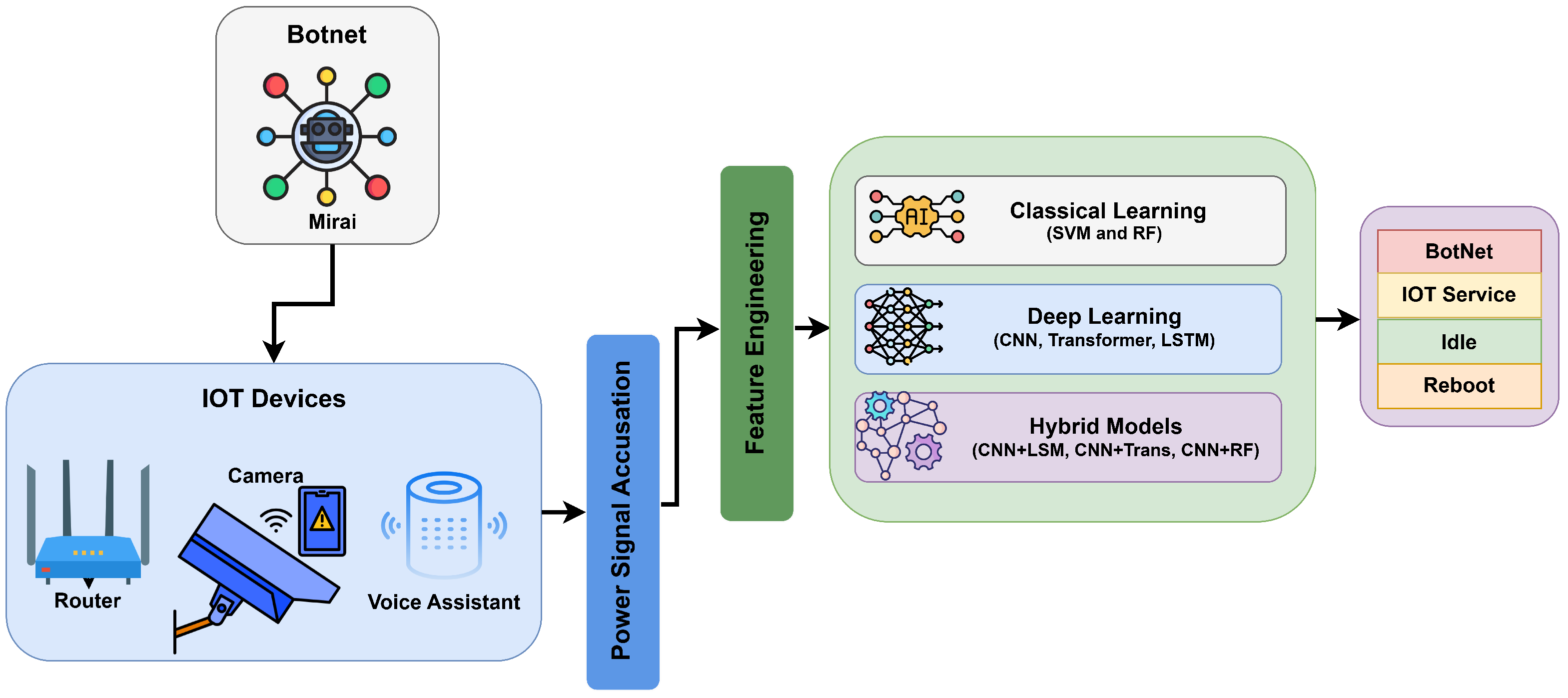

- A reproducible pipeline that compares classical (SVM, RF), deep (CNN, LSTM, 1D Transformer), and hybrid (CNN + LSTM, CNN + Transformer, CNN + RF) models on power side-channel signals under single-device, cross-device, and leave-one-device-out (LODO) regimes.

- A generalization-focused evaluation that makes device shift a first-class concern and quantifies when accuracy drops across devices.

- A deployment-oriented analysis that reports accuracy, together with latency and throughput, to guide edge implementations.

- Evidence indicates that RF attains the highest single-device accuracy on CHASE’19 99.43% on the Voice Assistant device with the best seed, while CNN + Transformer provides the best accuracy–efficiency trade-off in cross-device settings 97.83% test accuracy for the best seed (Seed 43) with a throughput of approximately 48,000 samples/s.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. From Signature to Learning-Based IDS in IoT

2.2. IoT Botnets: Threats and Traffic-Centric Detection

2.3. Power Side-Channel for Device-Level Detection

2.4. Gap Analysis and Positioning

3. Our Approach

- Stage 1. Data Preparation: IoT power traces are grouped into one-device and cross-device sets and split into Train/Val/Test.

- Stage 2. Data Preprocessing: Each 1.5 s window (7500 samples) is normalized and then routed either to (i) feature engineering, an 11-D vector of time/frequency statistics plus low-band energy used by SVM/RF or to (ii) deep-learning reshaping: for CNN/CNN + RF and for LSTM, a 1D Transformer, and hybrid models; Train/Val loaders are then built.

- Stage 3. Model Training: We train and validate under both single-device and cross-device regimes, compare validation metrics, and save the checkpoints.

- Stage 4. Evaluation and Benchmarking: The trained single-device and cross-device models are loaded in parallel lanes to run test-time intrusion detection (with the same normalization), compute accuracy, precision, recall, F1, ROC–AUC, and efficiency (latency, throughput), after which we compare models and select the best configuration for deployment.

3.1. Workflow

3.1.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

Three-Class Botnet Dataset (Robustness Benchmark)

3.1.2. Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Features for Classical Machine Learning

Preprocessing for Deep Learning

3.2. Experimental Setup

3.3. Model Architecture

3.3.1. Traditional Models

- Random Forest (RF): The RF classifier is trained on the engineered 11-dimensional feature vectors using 100 trees with a maximum depth of 20. These hyperparameters are selected to strike a balance between model complexity and interpretability, ensuring adequate ensemble diversity without overfitting on limited-dimensional inputs.

- SVM Pipeline: The SVM pipeline first extracts the 11-dimensional feature vector (using time-domain and frequency-domain statistics) from each raw signal. Following an 80/20 train-test split, an SVM with an RBF kernel is trained (with grid search tuning yielding parameters such as and ). Although grid search improves performance slightly, the SVM achieves only about 78% accuracy on cross-device evaluation.

3.3.2. Deep Learning Models

- Baseline CNN: A one-dimensional CNN is applied to inputs reshaped as (17, 500). The network uses 10 filters with a kernel size of 512 and a stride of 128, which is then followed by batch normalization, ReLU activation, and max pooling (kernel size of 4, stride of 4). Fully connected layers classify the flattened representation. Training is performed with Adam (learning rate of 0.001) over 20 epochs. Latency/throughput are reported in the Results tables.

- LSTM Model: Signals, reshaped to (75, 100), are processed by an LSTM with a hidden size of 128. The final hidden state is fed into a fully connected layer to yield the classification logits. Training uses Adam (learning rate of 0.001) over 20 epochs, with an average inference time of 0.0001710 s/batch.

- 1D Transformer Model: Inputs reshaped to (75, 100) are first projected via a linear embedding layer into a 128-dimensional space. Sinusoidal positional encoding is added, and a 2-layer Transformer encoder (consisting of four attention heads and a feedforward dimension of 256) processes the sequence. The final time-step representation is used for classification. This model is also trained with Adam (learning rate of 0.001) over 20 epochs, latency and throughput are reported in Table 2.

3.3.3. Hybrid Models

- Hybrid CNN + LSTM: Each normalized signal is reshaped to and passed through a CNN block consisting of a 1D convolution (kernel size of 3 with 16 filters), batch normalization, ReLU activation, and max pooling (kernel size of 2), resulting in a feature map of approximately , where B is the batch size. An LSTM then processes this feature map with a hidden size of 128. The final hidden state is classified via a fully connected layer. Training is conducted over 20 epochs with Adam, where learning rate is 0.001, and achieves 97–98% accuracy with a throughput up to 161K samples/s. Algorithm 1 describes the Hybrid CNN + LSTM model development process.

- Hybrid CNN + Transformer: After normalization and reshaping to , the signal is processed by the same CNN block as in the CNN + LSTM model to yield a feature map of shape , with . This feature map is linearly projected to the transformer dimension, augmented with positional encodings, and processed by a 2-layer Transformer encoder (with four heads and a feedforward dimension of 256). The final time-step representation is then classified via a fully connected layer. Training is performed for 20 epochs (Adam, learning rate = 0.001) with comparable accuracy to the CNN + LSTM hybrid. Algorithm 2 describes the Hybrid CNN + Transformer pipeline.

- Hybrid CNN + RF: For this approach, each raw signal (reshaped to ) is normalized and passed through a CNN block (conv, BN, ReLU, max pooling) to extract a feature embedding (e.g., 128-dimensional). The embeddings are then used as inputs to a Random Forest classifier. Embeddings are extracted using a CNN and classified using a pre-trained RF during inference. The CNN is trained normally, and then embeddings are extracted and used to train an RF. This yields about 95% accuracy on single-device data.

| Algorithm 1: Hybrid CNN + LSTM Model |

|

| Algorithm 2: Hybrid CNN + Transformer Model |

|

| Algorithm 3: Hybrid CNN + RF Model |

|

4. Performance Evaluation

4.1. Evaluation Methodology

4.2. Evaluation Results

4.2.1. Single-Device Experiments

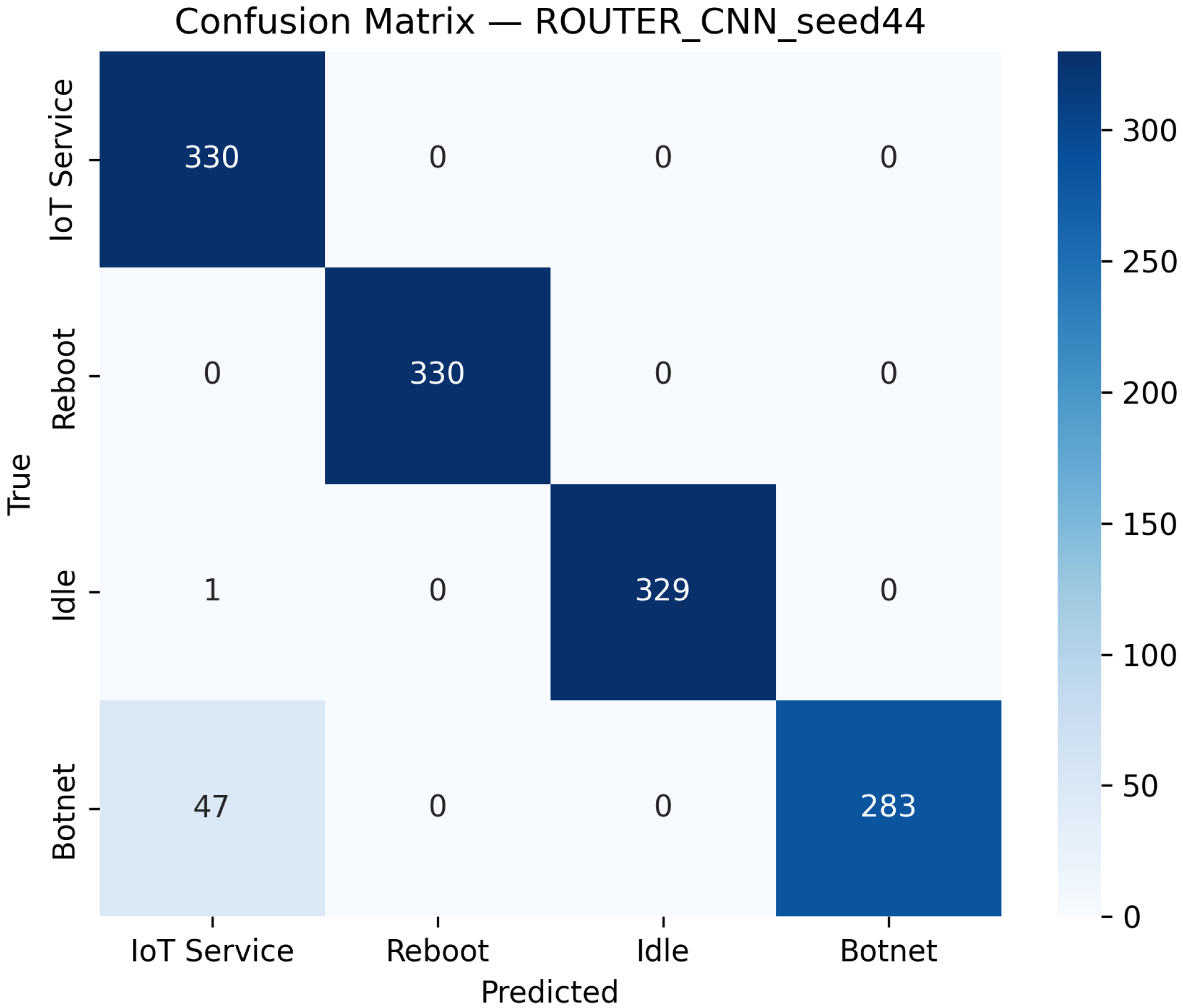

CNN Model Performance

LSTM Model Performance

1D Transformer Model Performance

4.2.2. Cross-Device Experiments

Classical Models on Combined Data

Deep Models on Combined Data

- CNN Model (Combined Device Data): Figure 9 illustrates the confusion matrix for the CNN model when applied to the combined device dataset. The matrix indicates that the model maintains high true positive rates across most classes, although slight performance degradations can be observed compared to single-device experiments. Figure 10 illustrates the ROC curves with strong AUC values for each class.For the LSTM and 1D Transformer models, similar evaluations (with corresponding tables and discussion) are performed on the combined device dataset.

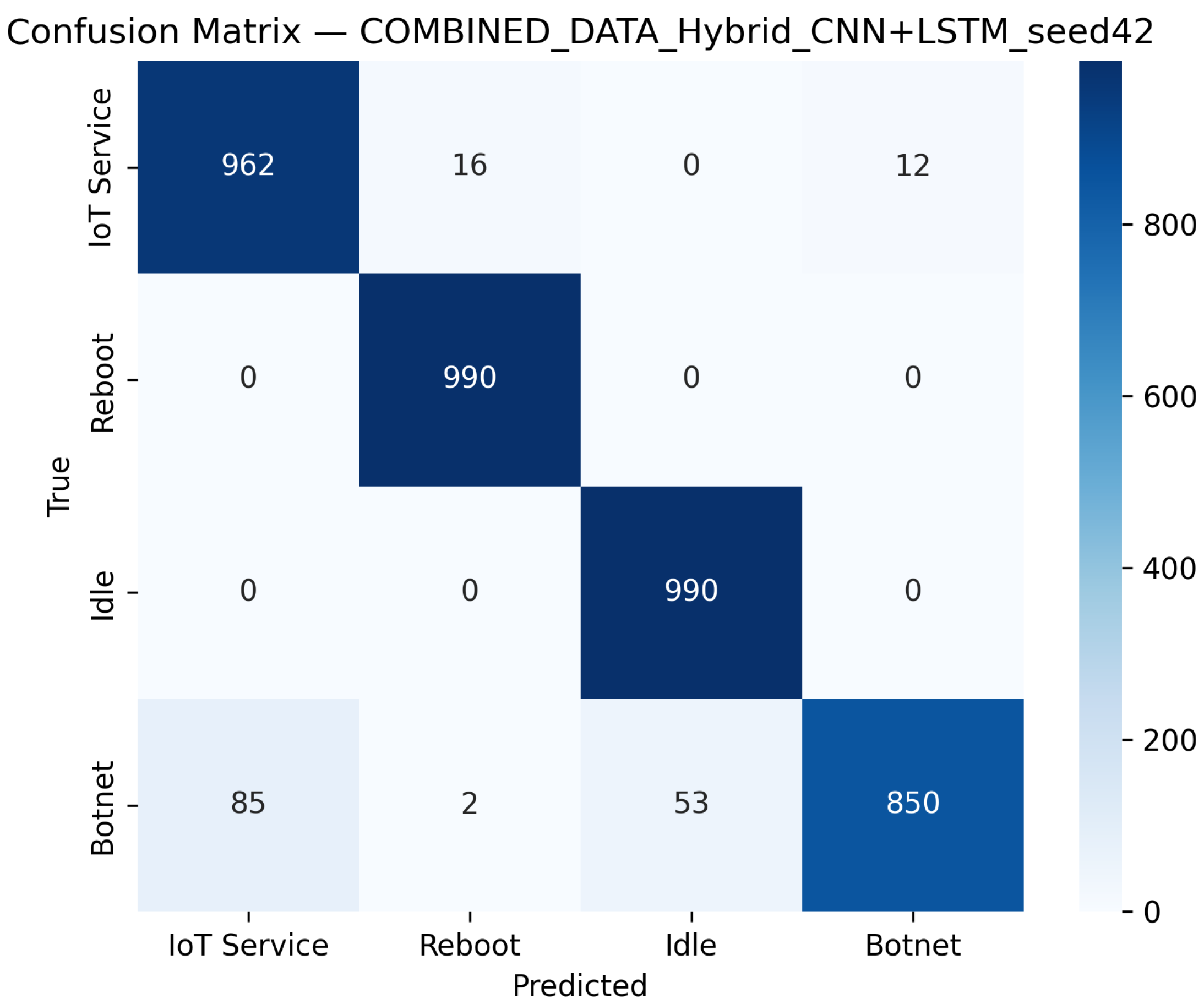

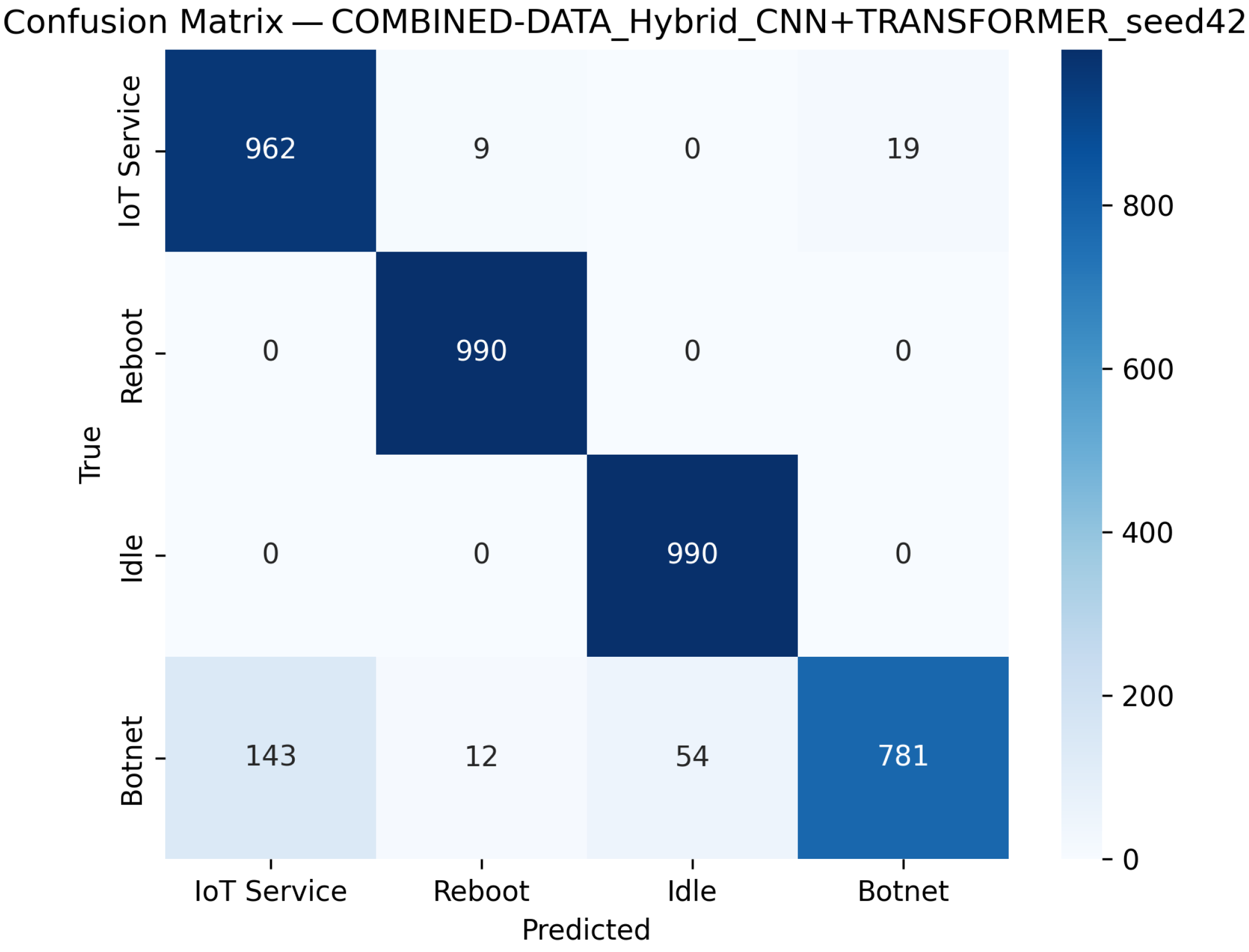

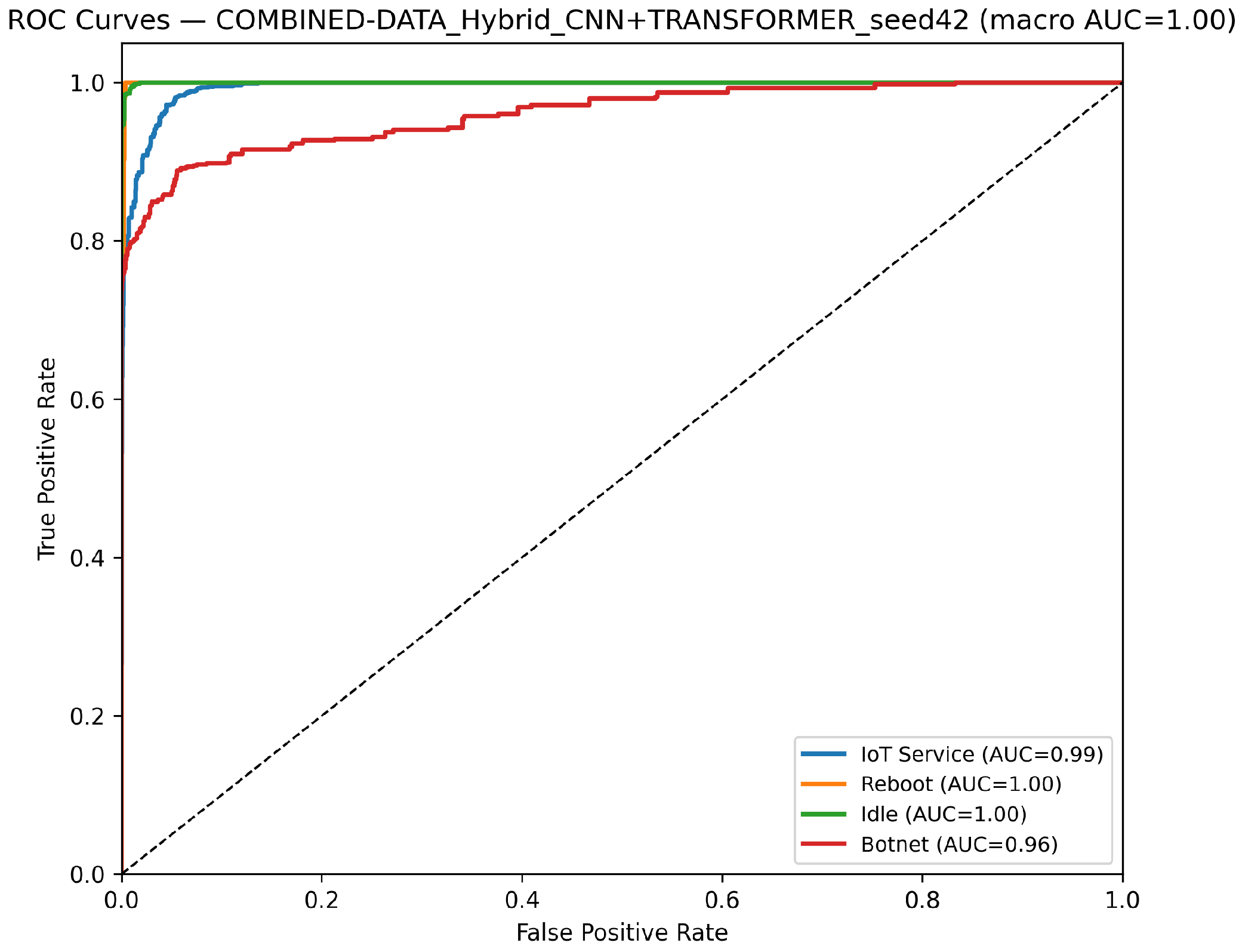

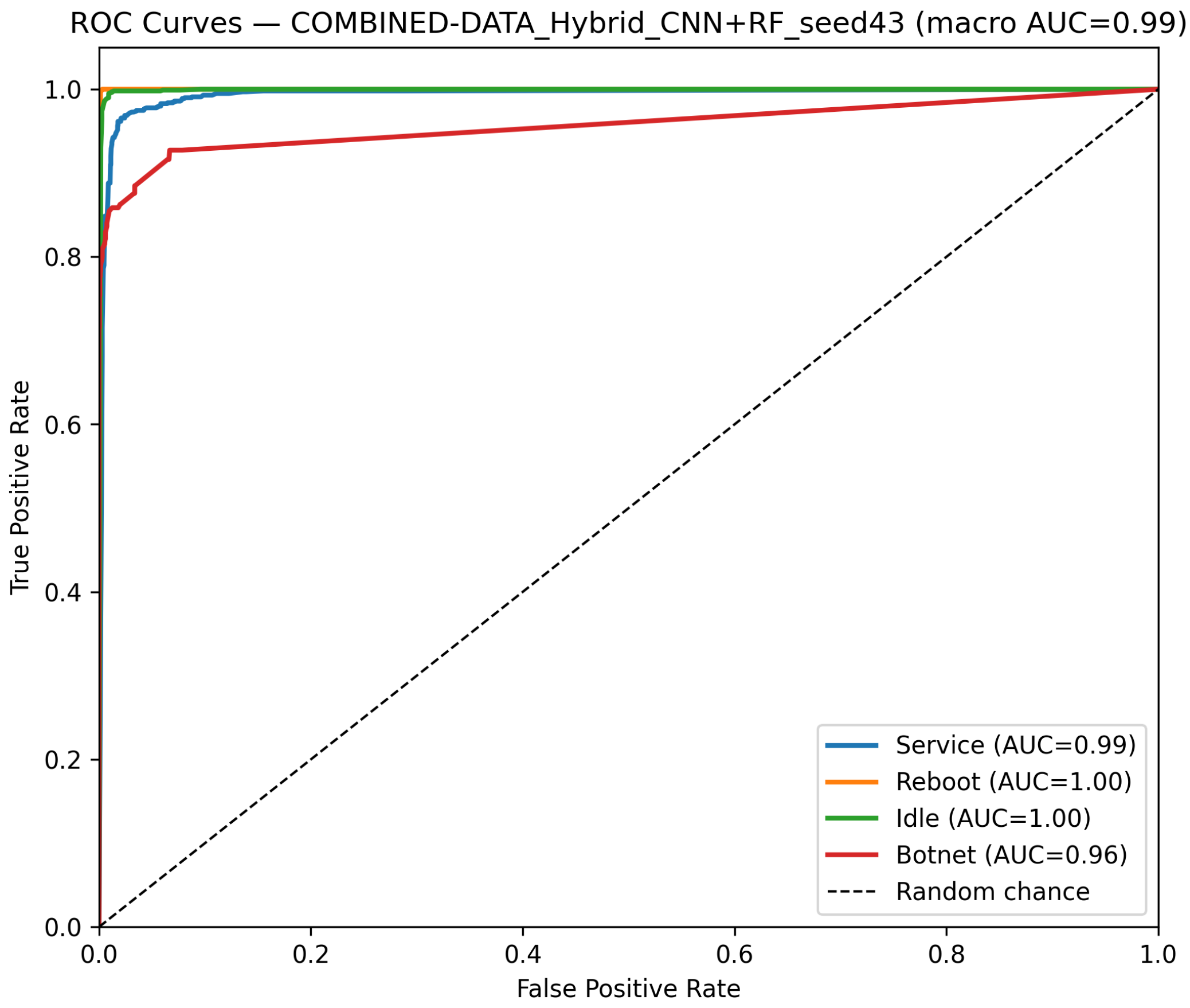

- Hybrid Models on Combined Data: Hybrid models, which integrate CNN-based feature extraction with sequential modules or classical classifiers, are critical for achieving robust cross-device performance. Their evaluations on the combined device dataset yield insights into both classification performance and computational efficiency.

- Hybrid CNN + LSTM (Combined Device Data): Figure 11 presents the confusion matrix for the CNN + LSTM model on the combined device dataset, while Figure 12 shows its ROC curves. These figures indicate that although the hybrid approach slightly reduces overall accuracy compared to single-device experiments, it still retains strong per-class performance.

4.2.3. Computational Efficiency Comparison

4.3. Performance Analysis

4.3.1. Single-Device Evaluation

Model Performance Comparison

Efficiency and Accuracy Trade-Offs

4.3.2. Cross-Device Evaluation

Model Performance Comparison

Efficiency and Accuracy Trade-Offs

4.3.3. LODO Evaluation Results

4.3.4. Best Model Trade-Off Analysis

5. Limitations and Threats to Validity

- While the CHASE’19 corpus enables consistent single-device, cross-device, and leave-one-device-out evaluations within a single source, it reflects devices and attack mixes that are now older. As a result, headline numbers may not fully anticipate changes in firmware, power management, or newer botnet families. We use CHASE’19 to preserve comparability with prior power-based IDS work and to isolate modeling and deployment trade-offs; however, we acknowledge that broader external validation remains necessary.

- Device diversity in our experiments is limited to three categories: routers, cameras, and voice assistants. This narrows the space of hardware states, idle behaviors, and power delivery conditions. Cross-device and leave-one-device-out protocols reduce partition bias, but they do not substitute for systematic evaluations on additional device classes, different power monitors, or mains conditions that vary across environments.

- All models were trained and evaluated on fixed 1.5 s windows with balanced splits for CHASE’19. Fixed windows aid reproducibility and controlled comparison, yet they may smooth longer temporal dynamics and reduce sensitivity to bursty or slowly evolving behaviors. Class balancing simplifies learning in homogeneous settings, although it can move the operating point away from natural prevalence in deployment.

- Regarding the Three-Class Botnet Dataset used for robustness checks, our rigorous validation (using 5-fold cross-validation and multiple random seeds) consistently yielded 100% accuracy across all folds. Despite ensuring strict separation between training and testing sets to prevent data leakage, this uniform perfection suggests that the specific attack signatures in this smaller dataset (e.g., high-intensity DDoS power spikes) are highly separable from the idle/benign baselines. Consequently, while these results confirm the models’ ability to distinguish distinct anomalies, this dataset may lack the complexity or noise required to stress-test deep architectures or differentiate fine-grained model performance compared to the CHASE’19 benchmark.

- Our efficiency measurements report average inference latency and throughput under a single hardware and software stack, including warm-up. These measurements capture relative trends between model families, however absolute values can change with batch size, kernel implementations, scheduler variability, and different accelerators. Energy per inference and end-to-end system latency on embedded platforms were not measured in this study.

- Finally, this work does not evaluate zero-day families or adversaries that attempt to obscure or perturb power signatures. We also do not include interpretability analyses beyond aggregate metrics. Both aspects are important for practical adoption and for diagnosing failure modes under device shift.

6. Extension

- Future Data Acquisition and Evaluation: We plan to extend the benchmark with newer devices and firmware, a wider set of benign scenarios, and additional botnet families. We will expand cross-dataset testing, include calibrated precision–recall at fixed false alarm rates, and report energy per inference and on-device latency. We also intend to add repeated trials with multiple seeds, training curves, and per-class operating points, then release matched splits and scripts to enable apples-to-apples comparisons on future corpora.

- Larger-scale benchmarking across datasets and models: In this direction, we will expand the unified benchmark by adding more public and in-house datasets and by including additional model families. On the model side, this includes temporal convolutional variants, lightweight 1D architectures suitable for embedded use, and gradient-boosted trees trained on learned embeddings. On the data side, we will diversify device types and operating conditions to stress-test single-device, cross-device, and leave-one-device-out protocols under broader distribution shift. All preprocessing, training, and evaluation scripts will follow the same standardized pipeline used in this paper to ensure reproducibility.

- Cross-device adaptation and calibration-free transfer: To improve robustness under device shift, we will explore source-only domain generalization, test-time adaptation using batch statistics, and few-shot calibration that uses short unlabeled power windows collected on a new device. These methods will be assessed using the same metrics and protocols as before, with additional stress tests for firmware updates, sampling rate changes, and operating mode drift.

- Edge co-design with efficiency profiling and compression: To translate the best models into deployable systems, we will combine quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation with the latency and throughput measurements already reported. We will extend efficiency profiling to include energy per inference and end-to-end latency on representative gateways and microcontrollers, and then report accuracy, latency, throughput, and energy together to guide practical deployments.

- Explainable AI (XAI) integration: To address the “black box” nature of deep learning models and enhance trust in edge deployment, we will integrate post-hoc interpretability frameworks such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations). This will allow us to map specific power consumption features (e.g., CPU frequency spikes vs. transceiver idle states) to model predictions, providing security analysts with actionable insights beyond raw classification scores.

7. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agoramoorthy, M.; Ali, A.; Sujatha, D.; Michael Raj, T.F.; Ramesh, G. An Analysis of Signature-Based Components in Hybrid Intrusion Detection Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 Intelligent Computing and Control for Engineering and Business Systems (ICCEBS), Chennai, India, 14–15 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Lang, B. Machine learning and deep learning methods for intrusion detection systems: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Griffith, D.; Ge, L.; Bhattarai, S.; Golmie, N. An integrated detection system against false data injection attacks in the smart grid. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2015, 8, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, G.; Mahalingam, V.; Ge, L.; Nguyen, J.; Yu, W.; Lu, C. A Cloud Computing Based Network Monitoring and Threat Detection System for Critical Infrastructures. Big Data Res. 2016, 3, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Xu, G.; Chen, Z.; Moulema, P. A cloud computing based architecture for cyber security situation awareness. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), National Harbor, MD, USA, 14–16 October 2013; pp. 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Xuan, D.; Zhao, W. An Invisible Localization Attack to Internet Threat Monitors. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2009, 20, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Hatcher, W.G.; Liao, W.; Gao, W.; Yu, W. Machine Learning for Security and the Internet of Things: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 158126–158147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, W.G.; Yu, W. A Survey of Deep Learning: Platforms, Applications and Emerging Research Trends. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 24411–24432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Chen, Z.; Yu, W.; Liao, W. Towards asynchronous federated learning based threat detection: A DC-Adam approach. Comput. Secur. 2021, 108, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalaxmi, P.L.S.; Saha, R.; Kumar, G.; Conti, M.; Kim, T.H. Machine and Deep Learning Solutions for Intrusion Detection and Prevention in IoTs: A Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 121173–121192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Garadi, M.A.; Mohamed, A.; Al-Ali, A.K.; Du, X.; Ali, I.; Guizani, M. A Survey of Machine and Deep Learning Methods for Internet of Things (IoT) Security. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 1646–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniriho, P.; Mahmood, A.N.; Chowdhury, M.J.M. A Survey of Recent Advances in Deep Learning Models for Detecting Malware in Desktop and Mobile Platforms. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. Development of an IoT-Based Parking Space Management System Design. Int. J. Appl. Inf. Manag. 2023, 3, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, S.; Indirani, M.; Maidin, S.S.; Wei, J. Intelligent Transportation System’s Machine Learning-Based Traffic Prediction. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2024, 5, 1826–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qian, C.; Hatcher, W.G.; Xu, H.; Liao, W.; Yu, W. Secure Internet of Things (IoT)-Based Smart-World Critical Infrastructures: Survey, Case Study and Research Opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 79523–79544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Jabraeil Jamali, M.A. Internet of Things intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive review and future directions. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 3753–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yu, W.; Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, W. A Survey on Internet of Things: Architecture, Enabling Technologies, Security and Privacy, and Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiheidari, S.; Wakil, K.; Badri, M.; Navimipour, N.J. Intrusion detection systems in the Internet of things: A comprehensive investigation. Comput. Netw. 2019, 160, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saied, M.; Guirguis, S.; Madbouly, M. Review of filtering based feature selection for Botnet detection in the Internet of Things. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, R.A.; Maciá-Fernández, G.; García-Teodoro, P. Survey and taxonomy of botnet research through life-cycle. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2013, 45, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawi, O.; Lever, C.; Valakuzhy, K.; Snow, K.; Monrose, F.; Antonakakis, M. The circle of life: A large-scale study of the IoT malware lifecycle. In Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 11–13 August 2021; pp. 3505–3522. [Google Scholar]

- Merlino, V.; Allegra, D. Energy-based approach for attack detection in IoT devices: A survey. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Zhao, H.; Sun, M.; Zhou, G. IoT botnet detection via power consumption modeling. Smart Health 2020, 15, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Feng, Y.; Khan, S.A.; Xin, C.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, G. Deepauditor: Distributed online intrusion detection system for iot devices via power side-channel auditing. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN), Virtual, 4–6 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.; Li, Z.; Jung, W.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, D.; Xin, C.; Zhou, G. DeepShield: Lightweight privacy-preserving inference for real-time IoT botnet detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 37th International System-on-Chip Conference (SOCC), Dresden, Germany, 16–19 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, W.; Feng, Y.; Khan, S.A.; Xin, C.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, G. Demo Abstract: A Distributed Power Side-channel Auditing System for Online loT Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN), Milan, Italy, 4–6 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 509–510. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Perez, B.; Khan, S.A.; Feldhaus, B.; Zhao, D. A new design of smart plug for real-time iot malware detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Microelectronics Design & Test Symposium (MDTS), Virtual, 23–26 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Dong, J.; Hu, M.; Zhou, Q. A Lightweight Method for Botnet Detection in Internet of Things Environment. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 2458–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybocki, P.; Vassilakis, V.G. An analysis into physical and virtual power draw characteristics of embedded wireless sensor network devices under dos and rpl-based attacks. Sensors 2023, 23, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbir. IoT Malware Data. 2025. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sa05042/iot-malware-data (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Saied, M.; Guirguis, S. Explainable artificial intelligence for botnet detection in internet of things. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikissagbe, B.R.; Adda, M. Machine learning-based intrusion detection methods in IoT systems: A comprehensive review. Electronics 2024, 13, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayadi, B.H.; El Emary, I.M. Enhancing Security and Efficiency in Decentralized Smart Applications through Blockchain Machine Learning Integration. J. Curr. Res. Blockchain 2024, 1, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetio, A.B. Scam Detection in Metaverse Platforms Through Advanced Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Res. Metaverse 2025, 2, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, S.F. Fraudulent Transaction Detection in Online Systems Using Random Forest and Gradient Boosting. J. Cyber Law 2025, 1, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Al Shakil, S.; Mustakim, M.R. A survey on intrusion detection system in IoT networks. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Iqbal, S.; Buffett, S.; Sultana, M.; Taylor, A. Deep learning for intrusion detection in emerging technologies: A comprehensive survey and new perspectives. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagui, S.; Wang, X.; Bagui, S. Machine Learning Based Intrusion Detection for IoT Botnet. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2021, 11, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissi, I.; Boukabous, M.; Azizi, M.; Moussaoui, O.; El Fadili, H. Toward a deep learning-based intrusion detection system for IoT against botnet attacks. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2021, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, B.; Mandya, A.; Bapat, R.; Alali, F.; Brown, D.E.; Veeraraghavan, M. A Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches to Detect Botnet Traffic. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Wu, J.; Lin, Z.; Kamal, M.M.; Mostafa, H.; Sheraz, M.; Chuah, T.C. Comparative analysis of deep learning and traditional methods for IoT botnet detection using a multi-model framework across diverse datasets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A. Deep learning-based intrusion detection for IoT networks: A scalable and efficient approach. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korba, A.A.; Diaf, A.; Bouchiha, M.A.; Ghamri-Doudane, Y. Mitigating iot botnet attacks: An early-stage explainable network-based anomaly detection approach. Comput. Commun. 2025, 241, 108270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Li, H.; Luo, F.; Hu, H.; Cheng, L.; Xiao, H.; Ge, R. DeepPower: Non-intrusive and deep learning-based detection of IoT malware using power side channels. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Kyoto, Japan, 30 November–4 December 2020; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, N.; Acar, A.; Aris, A.; Uluagac, A.S.; Gungor, V.C. Energy consumption of on-device machine learning models for IoT intrusion detection. Internet Things 2023, 21, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.D.; Lemus-Prieto, F.; González-Sánchez, J.L.; Lindo, A.C. Intrusion Detection for IoT Environments Through Side-Channel and Machine Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 98450–98465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hai, T.; Jawawi, D.N.A.; Wang, D.; Lakshmanna, K.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Iwendi, M. A lightweight energy consumption ensemble-based botnet detection model for IoT/6G networks. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushehri, A.S.; Amirnia, A.; Belkhiri, A.; Keivanpour, S.; de Magalhães, F.G.; Nicolescu, G. Deep learning-driven anomaly detection for green IoT edge networks. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2023, 8, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathis, A.; Li, G.; Wei, S.; Orshansky, M.; Tiwari, M.; Gerstlauer, A. Sok paper: Power side-channel malware detection. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Hardware and Architectural Support for Security and Privacy 2024, Austin, TX, USA, 2 November 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nimmy, K.; Dilraj, M.; Sankaran, S.; Achuthan, K. Leveraging power consumption for anomaly detection on IoT devices in smart homes. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 14045–14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Asif, M.; Rahman, M.T.; Rahman, M.A. Side-Channel-Driven Intrusion Detection System for Mission Critical Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2024 25th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–5 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbody, D.; Ngo, D.M.; Temko, A.; Murphy, C.C.; Popovici, E. Attacks on IoT: Side-channel power acquisition framework for intrusion detection. Future Internet 2023, 15, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightbody, D.; Ngo, D.M.; Temko, A.; Murphy, C.C.; Popovici, E. Dragon_Pi: IoT side-channel power data intrusion detection dataset and unsupervised convolutional autoencoder for intrusion detection. Future Internet 2024, 16, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Albasir, A.; Naik, K.; Manzano, R. Toward improving the security of IoT and CPS devices: An AI approach. Digit. Threat. Res. Pract. 2023, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Lahkar, M.P.; Gogor, A.; Boro, D. Side-Channel Analysis for Malicious Activity Detection Using Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Cognitive & Cloud Computing (IC3Com 2024), Jaipur, India, 1–2 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Model Family | Specific Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Classical | Random Forest: Trees = 100, Max Depth = 20, Criterion = Gini |

| SVM: Kernel = RBF, , | |

| Deep Learning | CNN: Conv1D(10 filters, k = 512, s = 128), BN, ReLU, MaxPool(4), FC |

| LSTM: Input = (75, 100), Hidden = 128, Layers = 1, Dropout = 0.0 | |

| Transformer: Layers = 2, Heads = 4, , , Sinusoidal PE | |

| Hybrid | CNN + LSTM: CNN block (as above) + LSTM (Hidden = 128) |

| CNN + Transformer: CNN block (as above) + Transformer (as above) | |

| CNN + RF: CNN Feature Extractor + RF Classifier (as above) | |

| Training Config | Optimizer = Adam, Learning Rate = , Epochs = 20 |

| Model (Device) | Test Acc. (Best Seed) | Macro-F1 (Best Seed) | K-Fold Acc. (Mean ± Std) | Avg. Inf. Time (s/Batch) | Throughput (Samples/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Models | |||||

| SVM (Router) | 27.05% | 13.95% | % | 0.63533 | 2770 |

| SVM (Camera) | 27.05% | 13.95% | % | 0.63486 | 2773 |

| SVM (Voice Assistant) | 40.74% | 32.71% | % | 0.55116 | 3194 |

| SVM (Router) | 27.05% | 13.95% | % | 0.6355 | 2769 |

| SVM (Camera) | 27.05% | 13.95% | % | 0.6258 | 2812 |

| SVM (Voice Assistant) | 40.74% | 32.71% | % | 0.5443 | 3233 |

| Deep Learning | |||||

| CNN (Router) | 96.36% | 96.35% | % | 0.00058 | 108,840 |

| CNN (Camera) | 93.94% | 93.94% | % | 0.00058 | 109,408 |

| CNN (Voice Assistant) | 92.42% | 92.27% | % | 0.00058 | 109,321 |

| LSTM (Router) | 99.09% | 99.09% | % | 0.00060 | 104,903 |

| LSTM (Camera) | 95.53% | 95.51% | % | 0.00059 | 105,707 |

| LSTM (Voice Assistant) | 88.71% | 87.77% | % | 0.00059 | 106,387 |

| 1D Transformer (Router) | 98.86% | 98.86% | % | 0.00119 | 52,864 |

| 1D Transformer (Camera) | 95.83% | 95.83% | % | 0.00123 | 51,100 |

| 1D Transformer (Voice Assistant) | 86.36% | 84.88% | % | 0.00119 | 52,695 |

| Hybrid Learning | |||||

| CNN + LSTM (Router) | 95.15% | 95.10% | % | 0.00069 | 92,566 |

| CNN + LSTM (Camera) | 93.33% | 93.22% | % | 0.00068 | 93,439 |

| CNN + LSTM (Voice Assistant) | 91.74% | 91.55% | % | 0.00065 | 96,781 |

| CNN + Transformer (Router) | 99.39% | 99.40% | % | 0.00092 | 68,235 |

| CNN + Transformer (Camera) | 96.36% | 96.36% | % | 0.00109 | 57,629 |

| CNN + Transformer (Voice Assistant) | 97.12% | 97.11% | % | 0.00103 | 61,019 |

| CNN + RF (Router) | 96.52% | 96.49% | % | 0.0117 | 113,535 |

| CNN + RF (Camera) | 91.97% | 91.64% | % | 0.0108 | 163,000 |

| CNN + RF (Voice Assistant) | 86.67% | 85.68% | % | 0.0094 | 188,000 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LSTM | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1D Transformer | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Random Forest | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SVM | 84.00 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| CNN + LSTM | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CNN + Transformer | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CNN + RF | 100.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| IoT Service | 0.8730 | 1.0000 | 0.9322 |

| Reboot | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Idle | 1.0000 | 0.9970 | 0.9985 |

| Botnet | 1.0000 | 0.8576 | 0.9233 |

| Overall Accuracy | 96.36% | ||

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| IoT Service | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| Reboot | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Idle | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Botnet | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Overall Accuracy | 99.09% | ||

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoT Service | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 324 |

| Reboot | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 334 |

| Idle | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 333 |

| Botnet | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 329 |

| Overall Accuracy | 97.80% | |||

| Model | Test Acc. (Best Seed) | Macro-F1 (Best Seed) | K-Fold Acc. (Mean ± Std) | Avg. Inf. Time (s/Batch) | Throughput (Samples/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 99.58% | 99.58% | % | 0.00808 | 59,566 |

| SVM | 79.07% | 76.20% | % | 3.73637 | 1413 |

| CNN | 94.60% | 94.44% | % | 0.00054 | 118,688 |

| LSTM | 94.42% | 94.31% | % | 0.00060 | 107,023 |

| 1D Transformer | 93.16% | 93.03% | % | 0.00119 | 53,898 |

| CNN + LSTM | 94.12% | 94.13% | % | 0.00053 | 114,025 |

| CNN + Transformer | 94.02% | 93.85% | % | 0.00119 | 53,682 |

| CNN + RF | 93.36% | 93.14% | % | 0.0238 | 166,726 |

| Model | Avg. Inference Time (s/Batch) | Throughput (Samples/s) |

|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.00808 | |

| SVM | 3.73637 | |

| CNN | 0.000541 | |

| LSTM | 0.000600 | |

| 1D Transformer | 0.00119 | |

| CNN + LSTM | 0.000573 | |

| CNN + Transformer | 0.001067 | |

| CNN + RF | 0.0238 |

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Avg. Inference Time (s/Batch) | Throughput (Samples/s) | Training Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Models | |||||||

| SVM | 75.00 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.0015199 | – | N/A |

| RF | 62.95 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.0077908 | – | N/A |

| Deep Learning Models | |||||||

| CNN | 74.91 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.000382 | 83,822 | 17.00 |

| LSTM | 78.52 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.0001677 | – | 14.43 |

| 1D Transformer | 77.84 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.0008380 | 17,024 | 51.25 |

| Hybrid Models | |||||||

| CNN + LSTM | 88.24 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.0003687 | 78,809 | 8.71 |

| CNN + Transformer | 89.85 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.0007675 | 35,313 | 47.22 |

| CNN + RF | 89.09 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.0085857 | 87,170 | 8.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wakili, A.A.; Guni, S.; Khan, S.A.; Yu, W.; Jung, W. Advancing Machine Learning Strategies for Power Consumption-Based IoT Botnet Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247553

Wakili AA, Guni S, Khan SA, Yu W, Jung W. Advancing Machine Learning Strategies for Power Consumption-Based IoT Botnet Detection. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247553

Chicago/Turabian StyleWakili, Almustapha A., Saugat Guni, Sabbir Ahmed Khan, Wei Yu, and Woosub Jung. 2025. "Advancing Machine Learning Strategies for Power Consumption-Based IoT Botnet Detection" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247553

APA StyleWakili, A. A., Guni, S., Khan, S. A., Yu, W., & Jung, W. (2025). Advancing Machine Learning Strategies for Power Consumption-Based IoT Botnet Detection. Sensors, 25(24), 7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247553