A Novel Method of Path Planning for an Intelligent Agent Based on an Improved RRT* Called KDB-RRT*

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

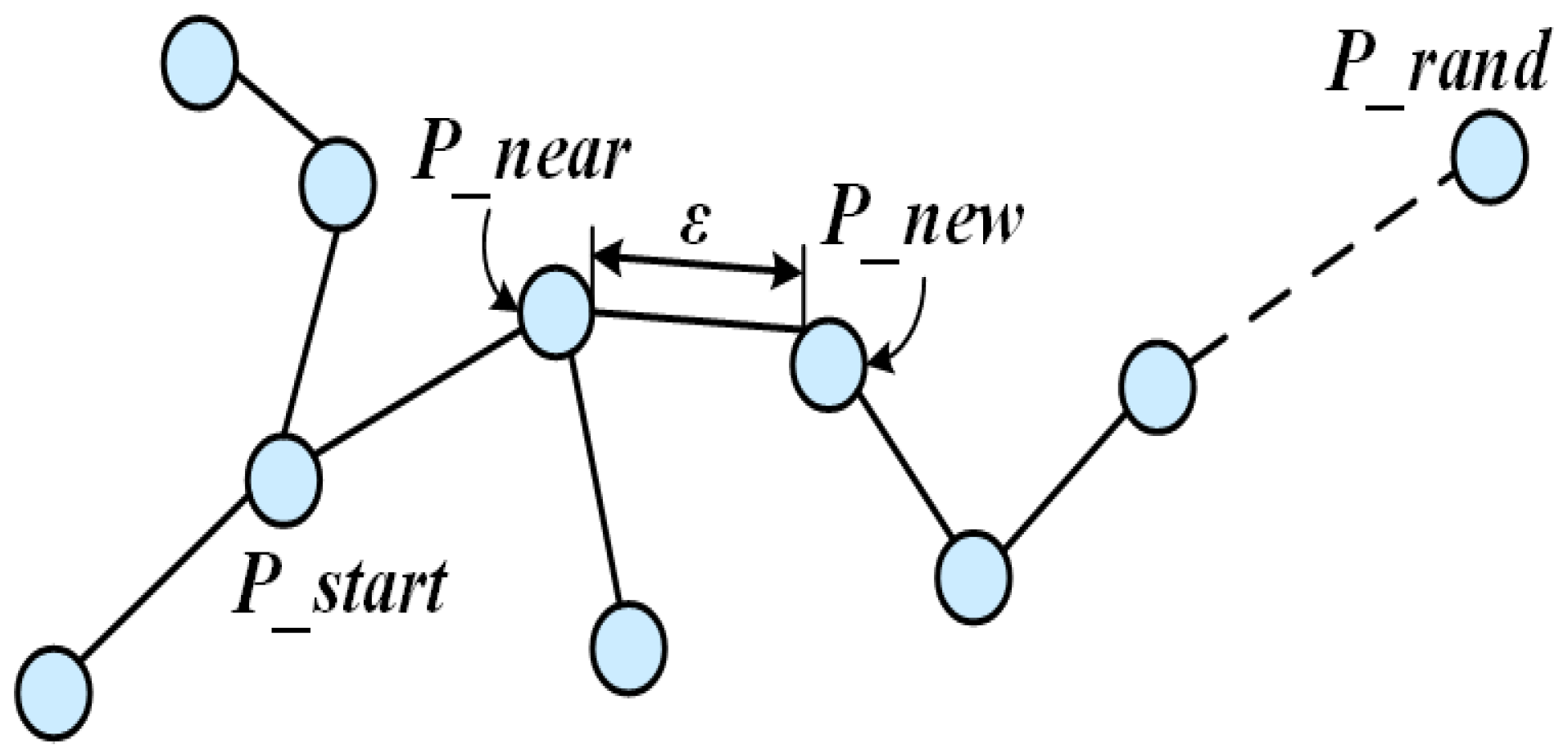

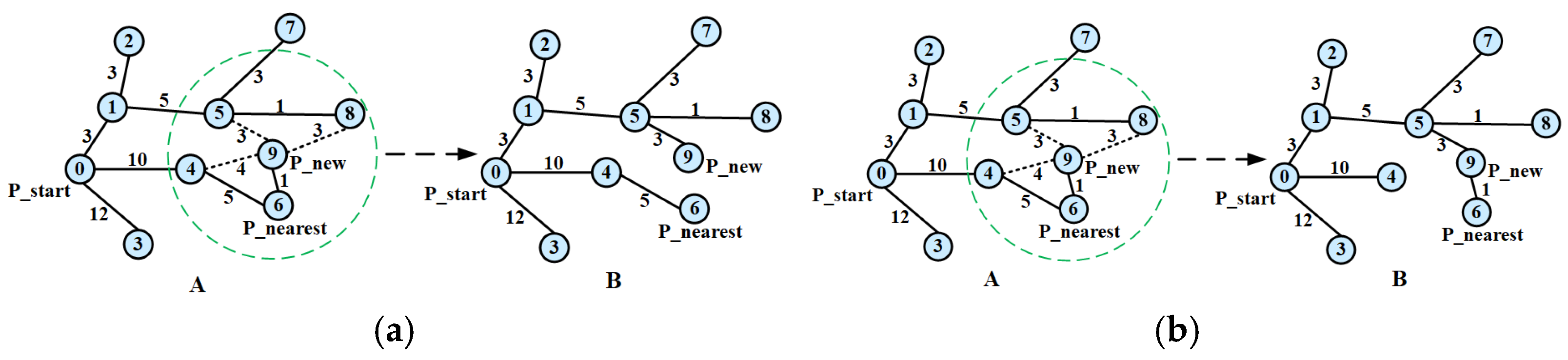

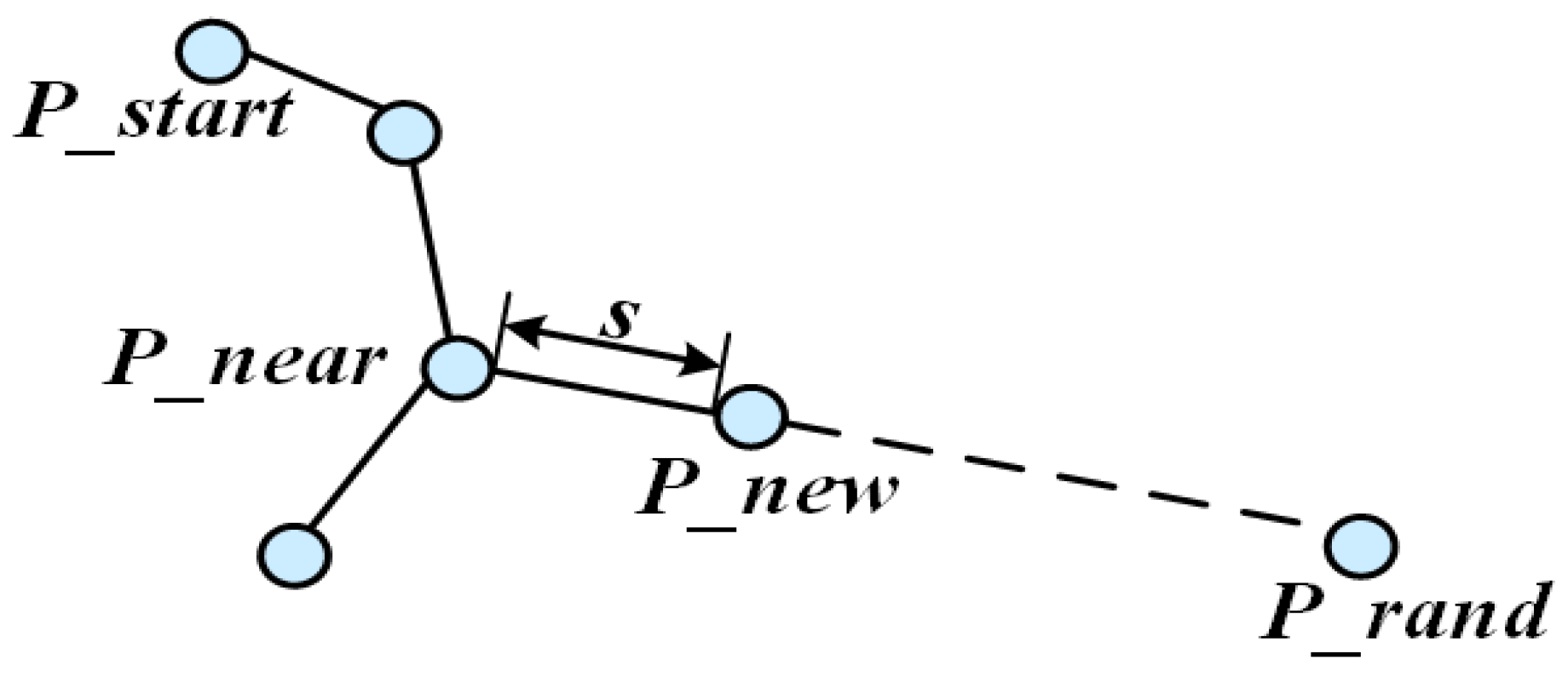

2.1. Basic Principle of RRT* Algorithm

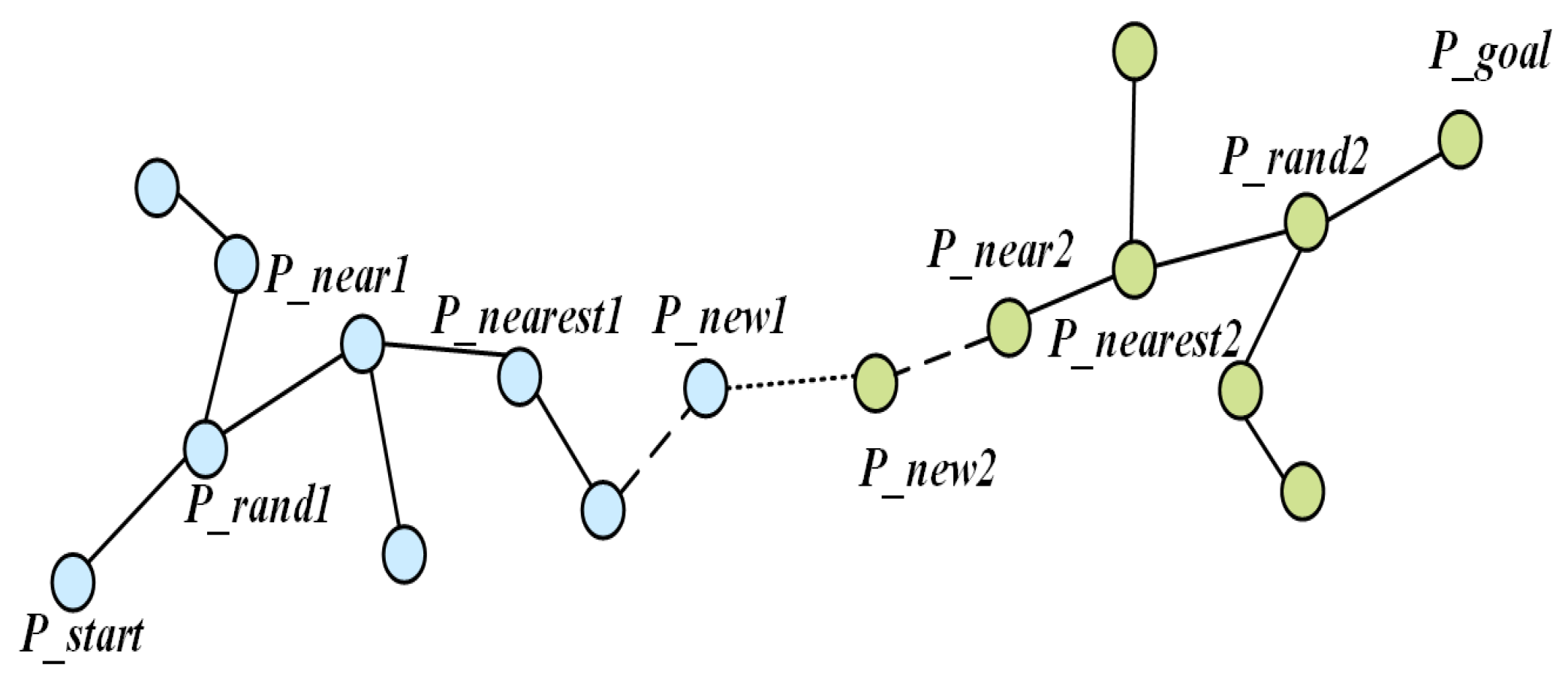

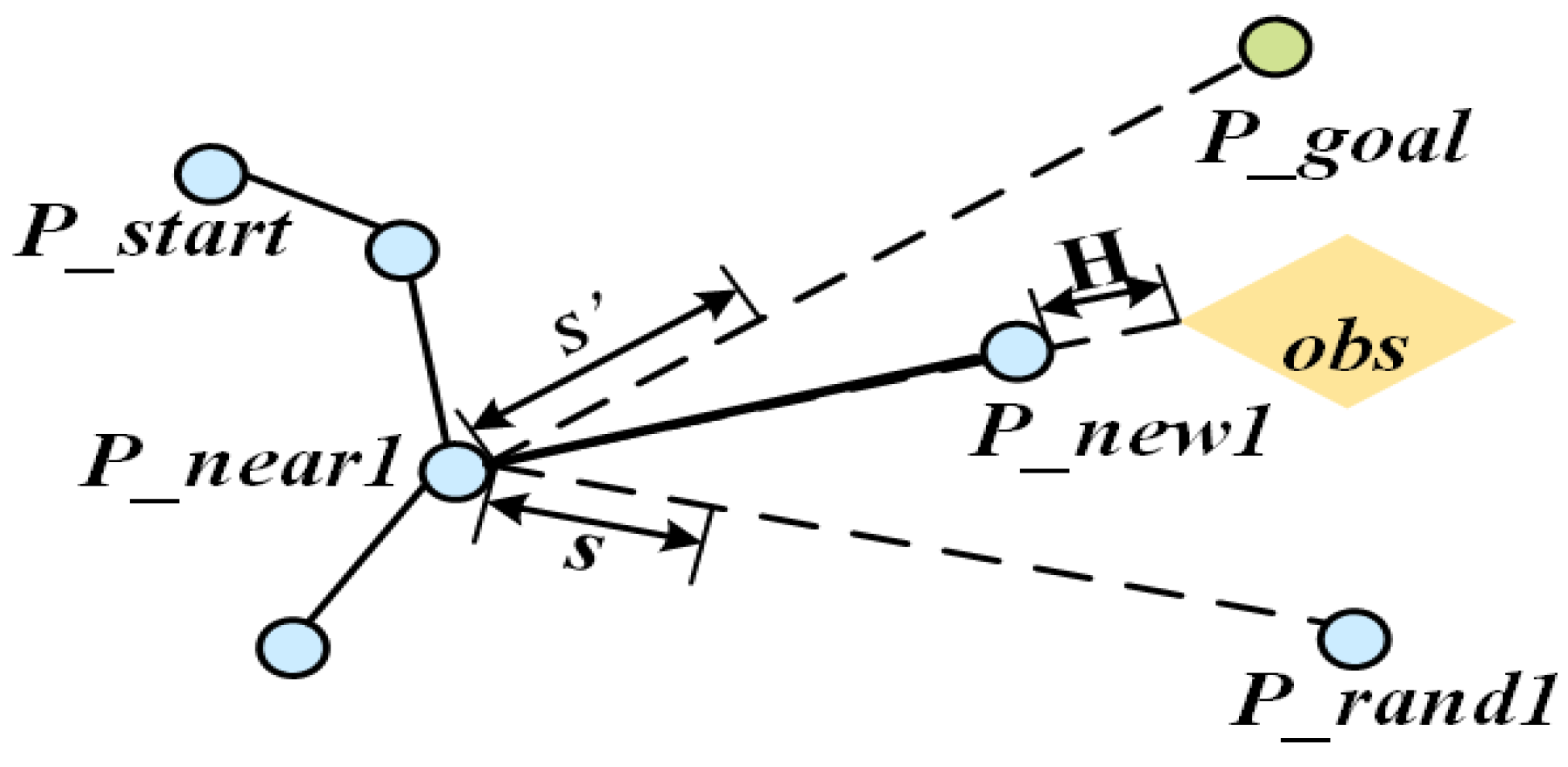

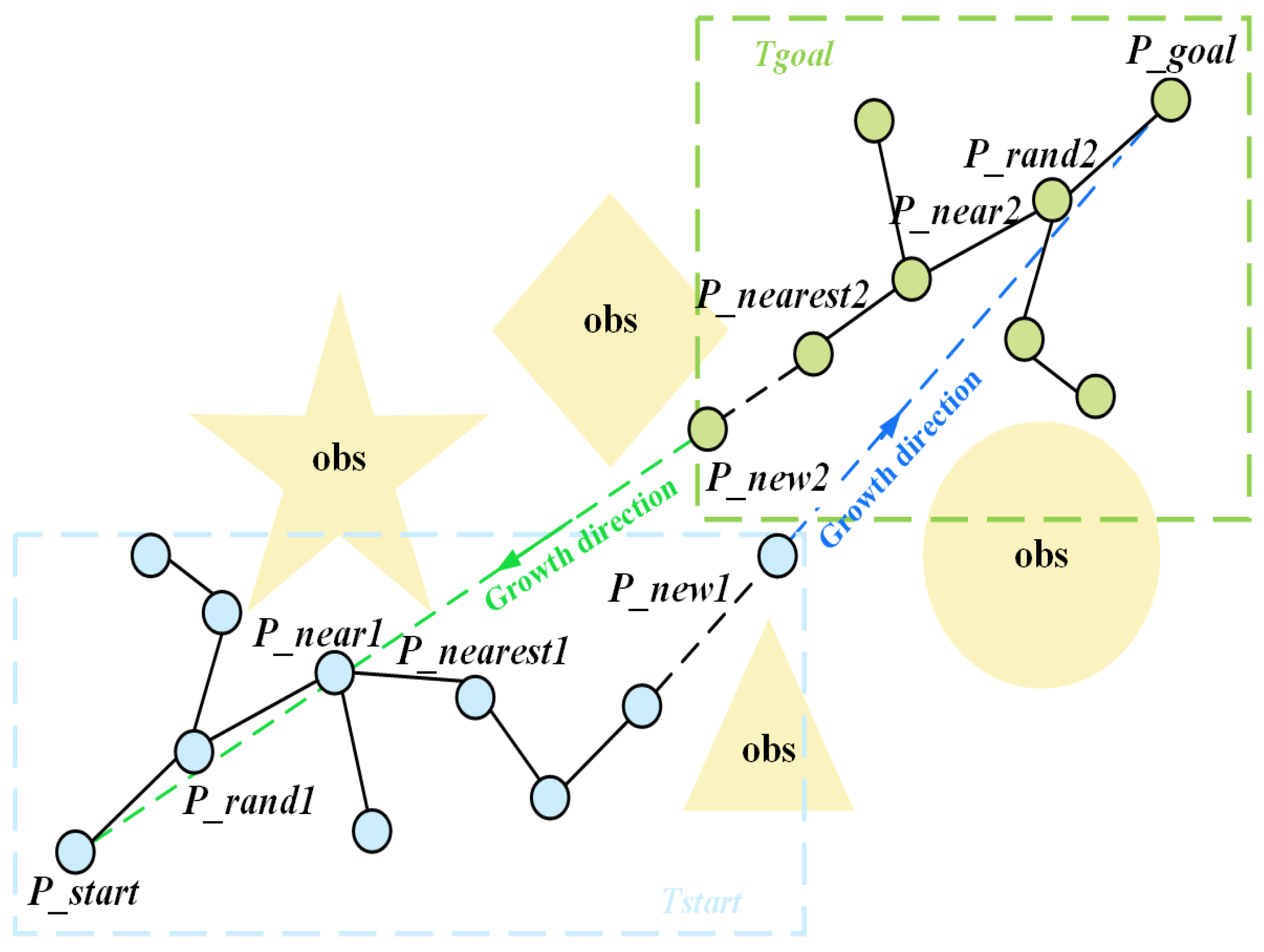

2.2. Basic Principle of B-RRT* Algorithm

3. Multi-Layer Optimization Architecture of KDB-RRT* Algorithm

3.1. KD-Tree Indexing for Nearest-Neighbor Query Optimization

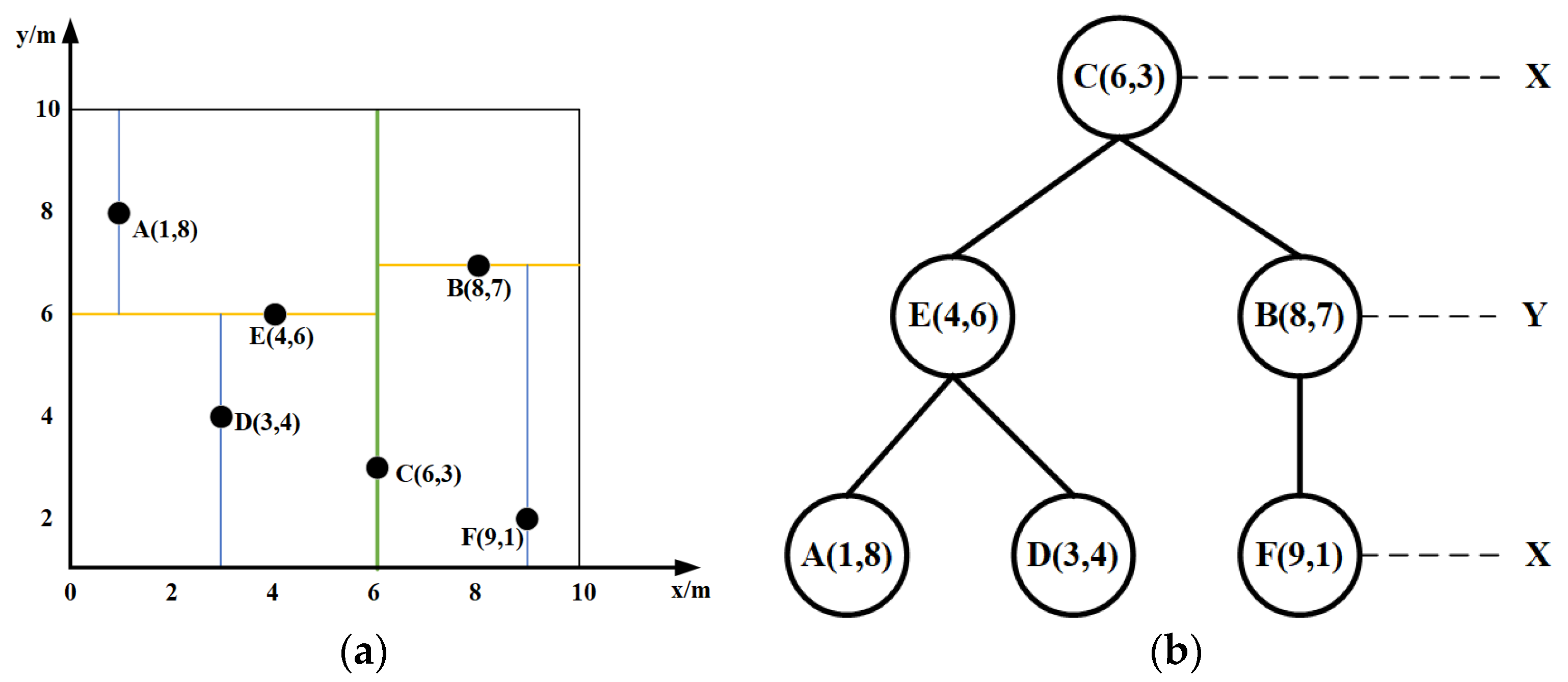

3.1.1. KD-Tree Organization

- Select Splitting Axis: Calculate the variance for both the x and y dimensions. Compare the variances and select the dimension with the larger variance as the splitting axis. Using Equation (1), the variances for the x and y dimensions in this example are calculated as and , respectively. Since , the x-dimension is chosen as the first splitting axis.

- Determine Median Point on Axis: Sort the data points based on the selected splitting dimension and choose the median point as the root node. Sorting all points by the x-dimension yields: A (1,8), D (3,4), E (4,6), C (6,3), B (8,7), F (9,1). The median point is C (6,3), which becomes the root node.

- Determine Left and Right Subtrees: Using the selected splitting axis and the median point as the splitting plane, construct the left and right subtrees. In this example, the left subtree contains {A (1,8), D (3,4), E (4,6)} and the right subtree contains {B (8,7), F (9,1)}.

- Recurse on Subtrees: Repeat steps (1) to (3) recursively for each subtree until each contains only one data point. Note: The splitting axis is typically selected by cycling through dimensions sequentially. Since the x-dimension was used at the first level, the y-dimension is used at the second level, the x-dimension again at the third level, and so on. In this example, step (4) proceeds as follows:

- For the left subtree {A, D, E}, select the y-dimension as the splitting axis. The median point on this axis is E (4,6). This splits the subtree into left child A (1,8) and right child D (3,4).

- For the right subtree {B, F}, select the y-dimension as the splitting axis. Point B (8,7) is chosen as the root node for this subtree (as it has the larger y-coordinate). This splits the subtree into right child F (9,1).

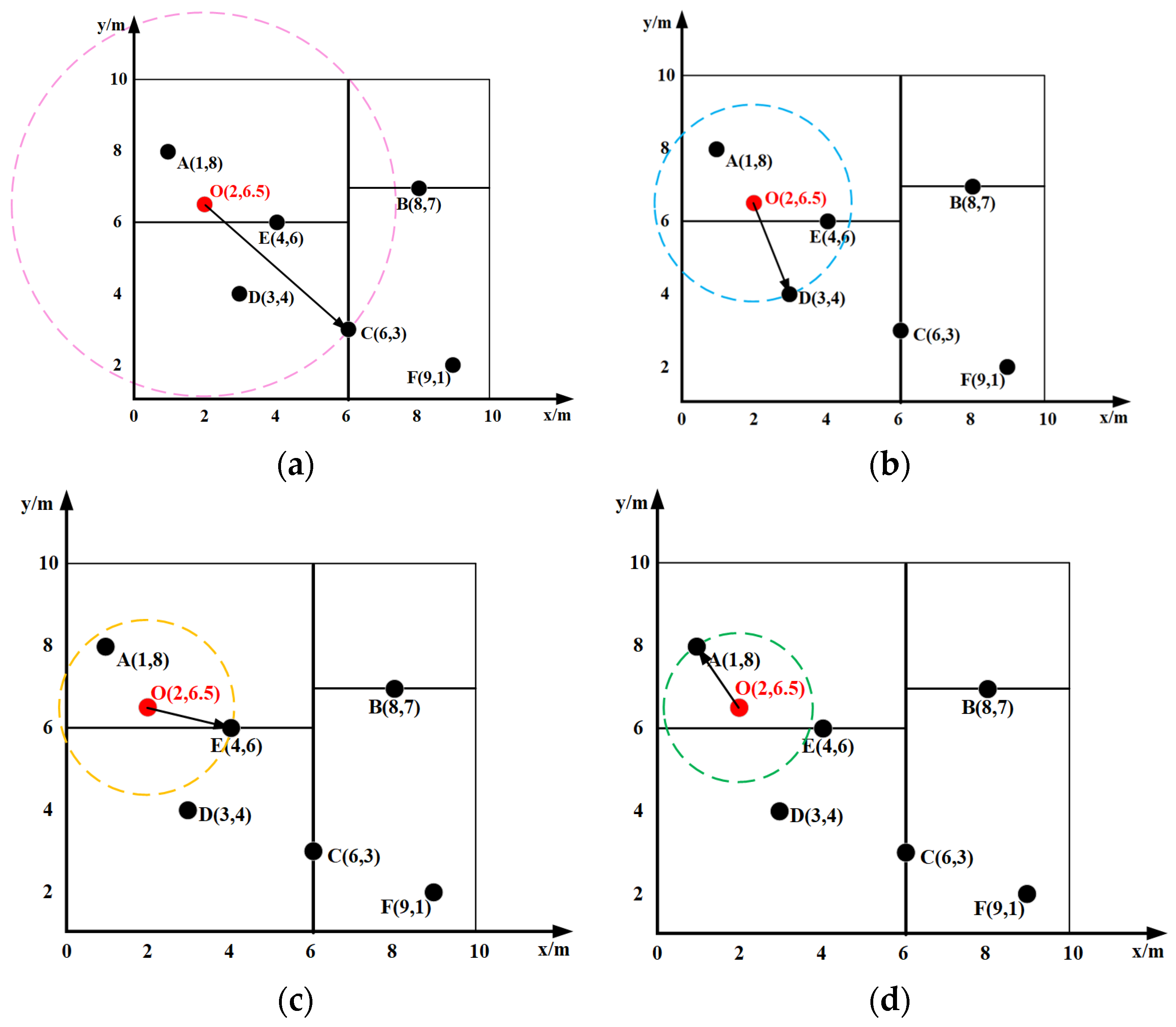

3.1.2. KD-Tree Nearest Neighbor Search

- Start at the root node C. Assume C is the current nearest neighbor. Define a red search circle centered at O with radius OC (Figure 5a). This circle intersects the hyperplanes y = 6 and y = 7. Since 6 < 7, search the right subspace of C first.

- Find E (4,6) in 1. The splitting hyperplane at C is y = 6. As O’s y-coordinate is 6.5, proceed to the right subspace, finding D (3,4). The search path is C (6,3) → E (4,6) → D (3,4). Set D as the current nearest neighbor. Define a new (blue) search circle centered at O with radius OD (Figure 5b).

- Backtrack to E (4,6), and calculate OC. Since OE < OD, update the current nearest neighbor to E (4,6). Define a new (yellow) search circle with radius OE (Figure 5c).

- The yellow circle intersects the hyperplane y = 4. Therefore, search the other subspace of E (4,6) (the left subtree). Calculate OA. Since OA < OC, update the current nearest neighbor to A (1,8) and the distance to OA. Define a new (green) search circle (Figure 5d).

- Backtrack to the root C (6,3). The green circle does not intersect the hyperplane x = 6, so searching the right subspace of C (6,3) is unnecessary. The search concludes, returning A (1,8) as the nearest neighbor O with distance OA.

3.1.3. Complexity Analysis

- Select Splitting Axis: Cyclic dimension switching () requires time, as the number of dimensions for 2D path planning) is fixed and independent of the dataset size .

- Determine Median Point on Axis: The randomized quickselect algorithm achieves average-case complexity, avoiding worst-case performance through randomized pivot selection.

- Determine Left and Right Subtrees: Distributing the remaining nodes into left/right subtrees requires time.

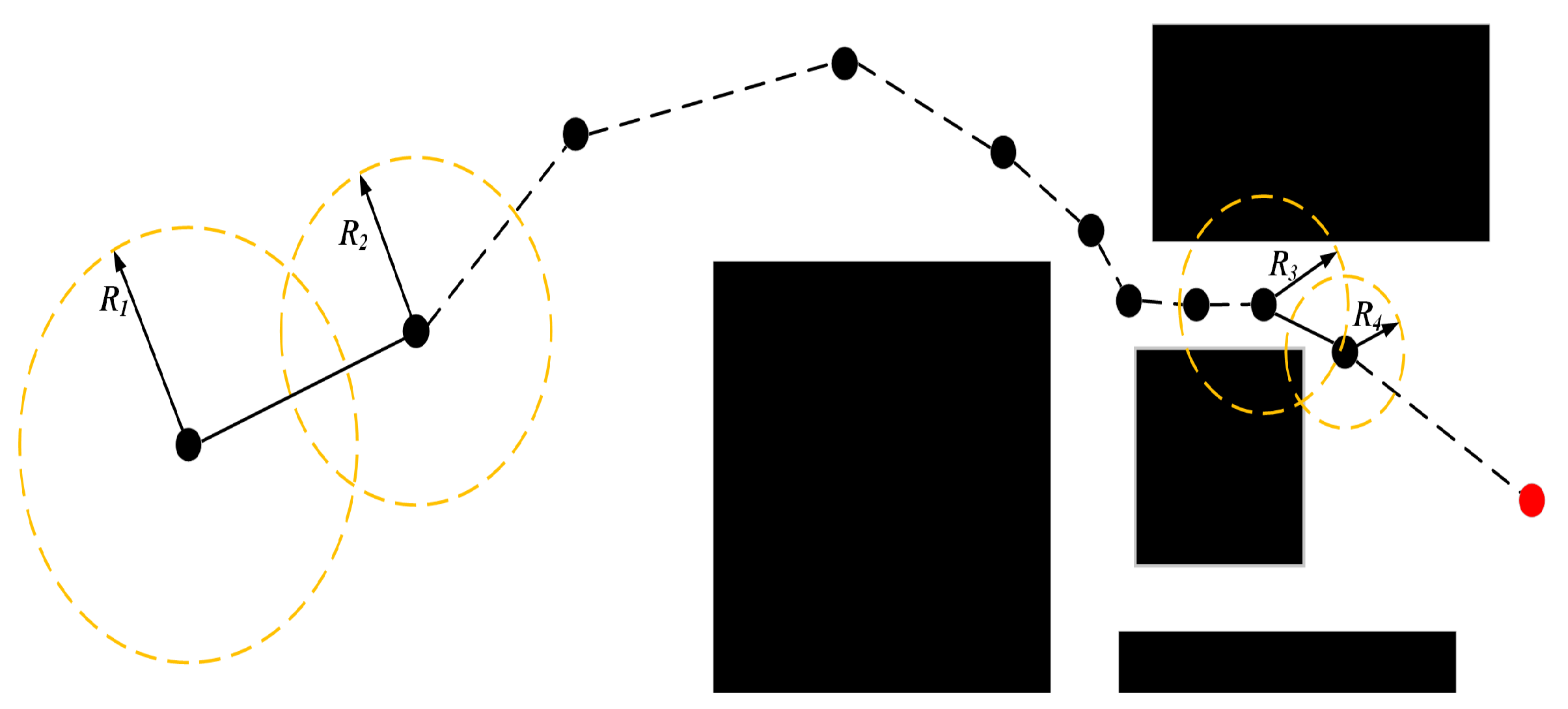

3.2. Target-Biased Dynamic Circular Sampling Strategy

3.3. Bidirectional Growth Guidance Model Based on Potential Field

3.4. Adaptive Step Size Based on Obstacle Density

3.5. Obstacle Avoidance and Collision Detection Mechanism

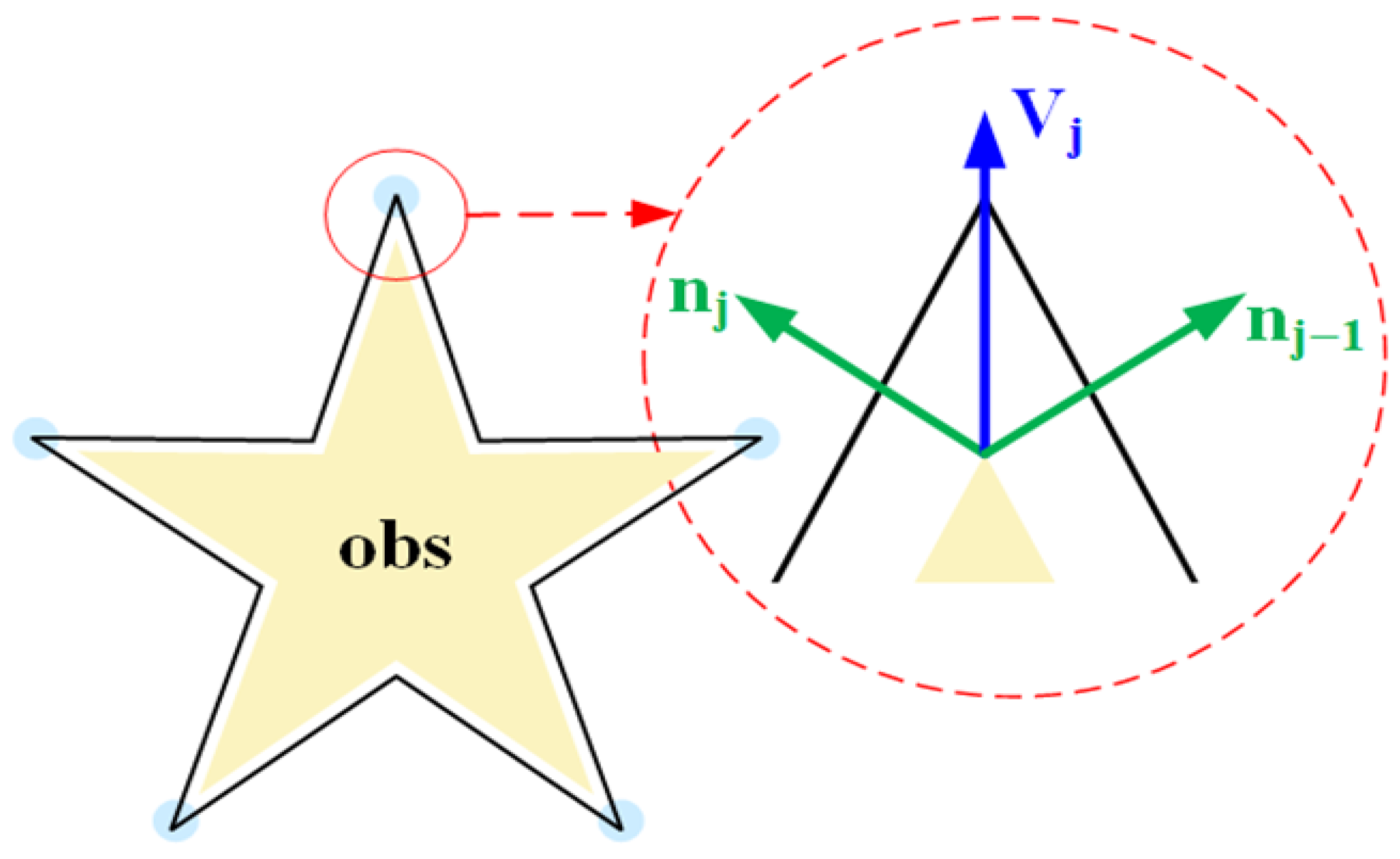

3.5.1. Collision Detection Framework

- Obstacle Modeling: In the 2D planning space, all obstacles are modeled as a set of polygons . Each obstacle is defined by an ordered sequence of vertices (vertices are arranged in a clockwise order to ensure polygon closure, with ).

- Collision Criterion: For any path segment (where and are consecutive nodes on the path), the necessary and sufficient condition for a collision with obstacle is that intersects with any boundary edge of (including endpoint contact) or lies entirely inside . Mathematically, it can be formalized as:where denotes the boundary edge of obstacle ; the operator represents the intersection relationship of geometric line segments (including endpoint contact). If the judgment is true, the path segment is invalid with a collision.

- Detection Acceleration Technologies: To address the inefficiency of detection in large-scale obstacle scenarios, this study introduces two key optimizations:

- Separating Axis Theorem (SAT) Pre-judgment: For polygonal obstacles, SAT is used to achieve fast collision judgment through projection analysis. Calculate the projection intervals of and on multiple feature axes (including the normal vectors of each edge of and the normal vector of ). If there exists any axis where the projection intervals do not overlap, it can be directly determined that and are collision-free without verifying all boundary edges. This method reduces the average time complexity of single obstacle detection from (where is the number of edges of the obstacle) to .

- Spatial Index Filtering (R-tree): In the preprocessing phase, an R-tree spatial index structure for obstacle boundary edges is constructed, partitioning them into several sub-regions based on the spatial coordinates (bounding boxes) of the boundary edges. When detecting path segment , the R-tree is first used to quickly retrieve the set of candidate boundary edges that are spatially intersecting or adjacent to (with a distance less than a preset threshold). Only these candidate edges are subjected to precise intersection verification and inner point judgment using SAT.

3.5.2. Active Obstacle Avoidance Mechanism

- Potential Field-Guided Growth Control: As described in Section 3.3, the repulsive force component generated by the potential field directly guides new nodes away from obstacles in the node expansion direction (Equation (7)), proactively avoiding potential collision areas.

- Adaptive Step-Size Control Based on Obstacle Density: As described in Section 3.4, the adaptive step size is dynamically adjusted according to the distance from the current node to the nearest obstacle. When approaching an obstacle, the step size is automatically reduced to lower the probability of path segments crossing obstacles due to excessively large step sizes and improve path quality in narrow areas.

- Safety Buffer Expansion: Considering the agent’s own physical size and uncertainty factors such as motion control and positioning errors, the original obstacle boundaries are expanded to construct a safety buffer zone, ensuring that the planned path maintains a minimum safe distance from the original obstacles. The minimum safe distance is defined as:where denotes the radius of the agent (since the agent is modeled as a mass point in this study, ), and is an additional safety margin to cope with uncertainties.

3.6. Path Optimization

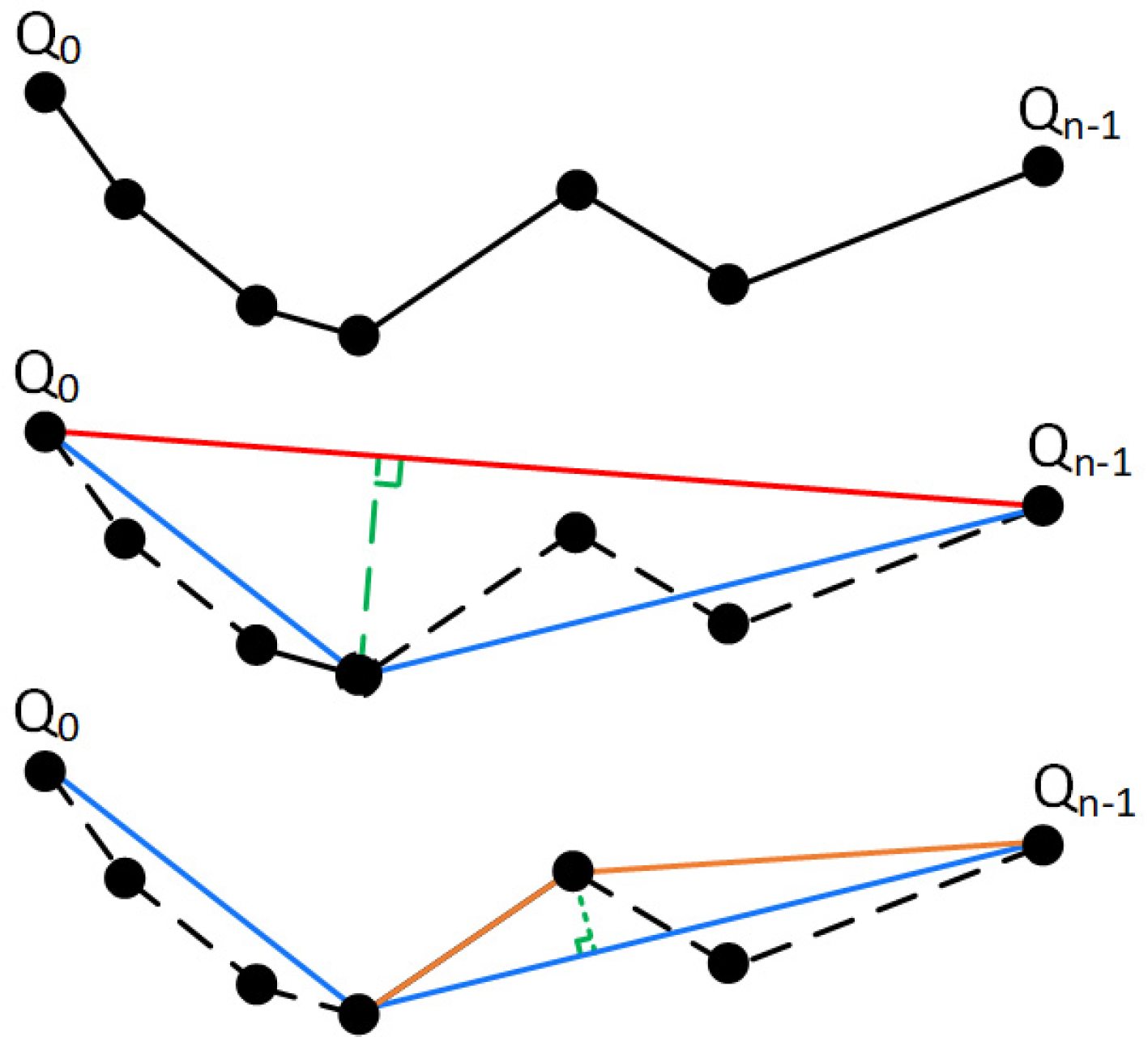

3.6.1. Pruning

- and last point of the curve;

- Calculate the perpendicular distance from each intermediate point to the line segment . Find the point with the maximum distance ;

- If , simplify the path to . If , split the path at into two sub-paths: and ;

- Repeat steps 1–3 for all path curve segments until all values are less than . This completes the thinning process.

- Injection of safety constraints: When calculating the maximum perpendicular distance , the minimum distance between the simplified path segment and obstacles is simultaneously verified. If a simplification operation results in the distance from the path segment to the nearest obstacle falling below the safety threshold (Equation (11)), the current simplification operation is aborted.

- Spatial index acceleration: A pre-constructed R-tree spatial index is utilized to quickly retrieve candidate obstacle edges within the neighborhood of the path segment. Only the candidate set undergoes precise distance calculation, avoiding global traversal of all obstacles.

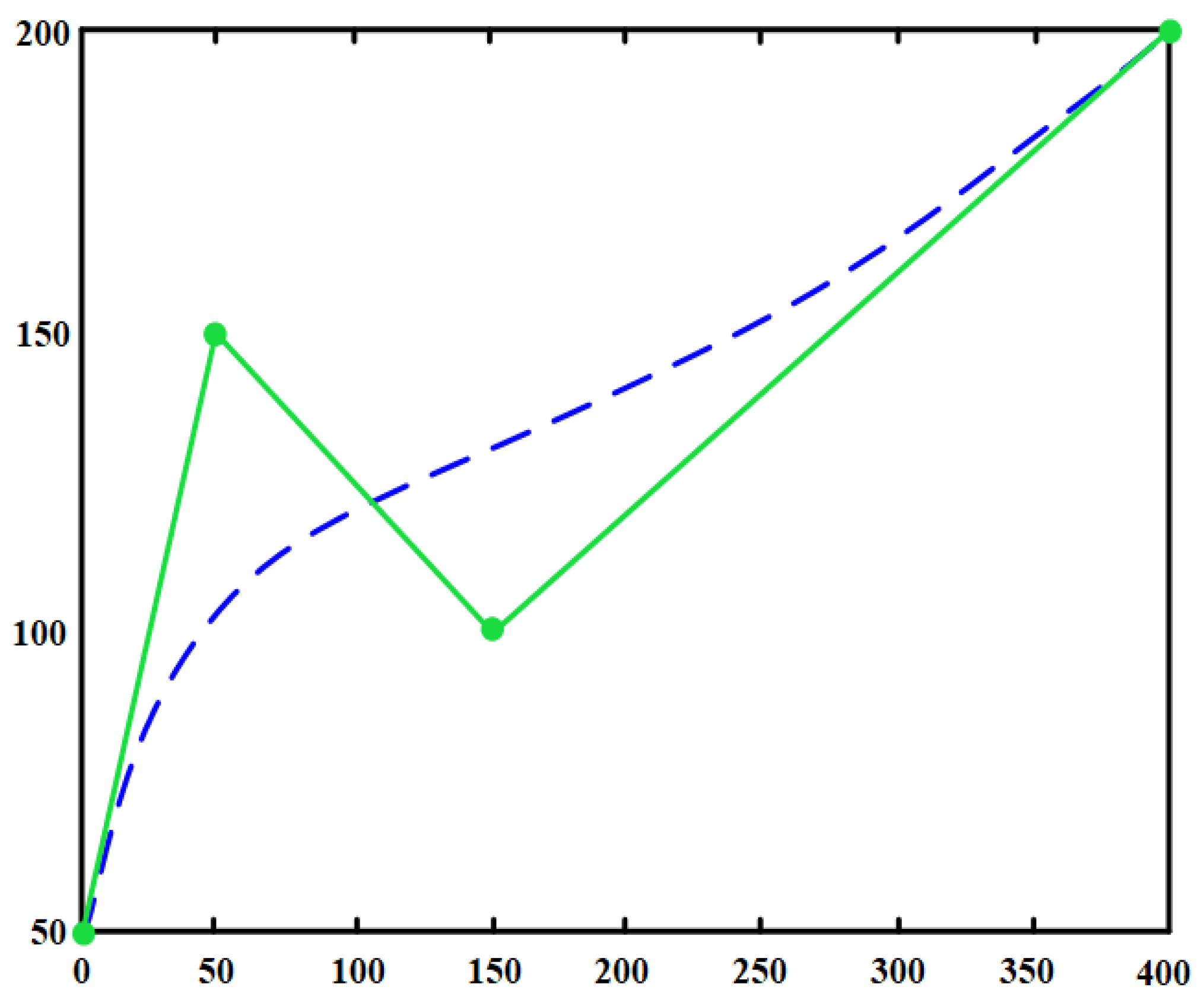

3.6.2. Smoothing

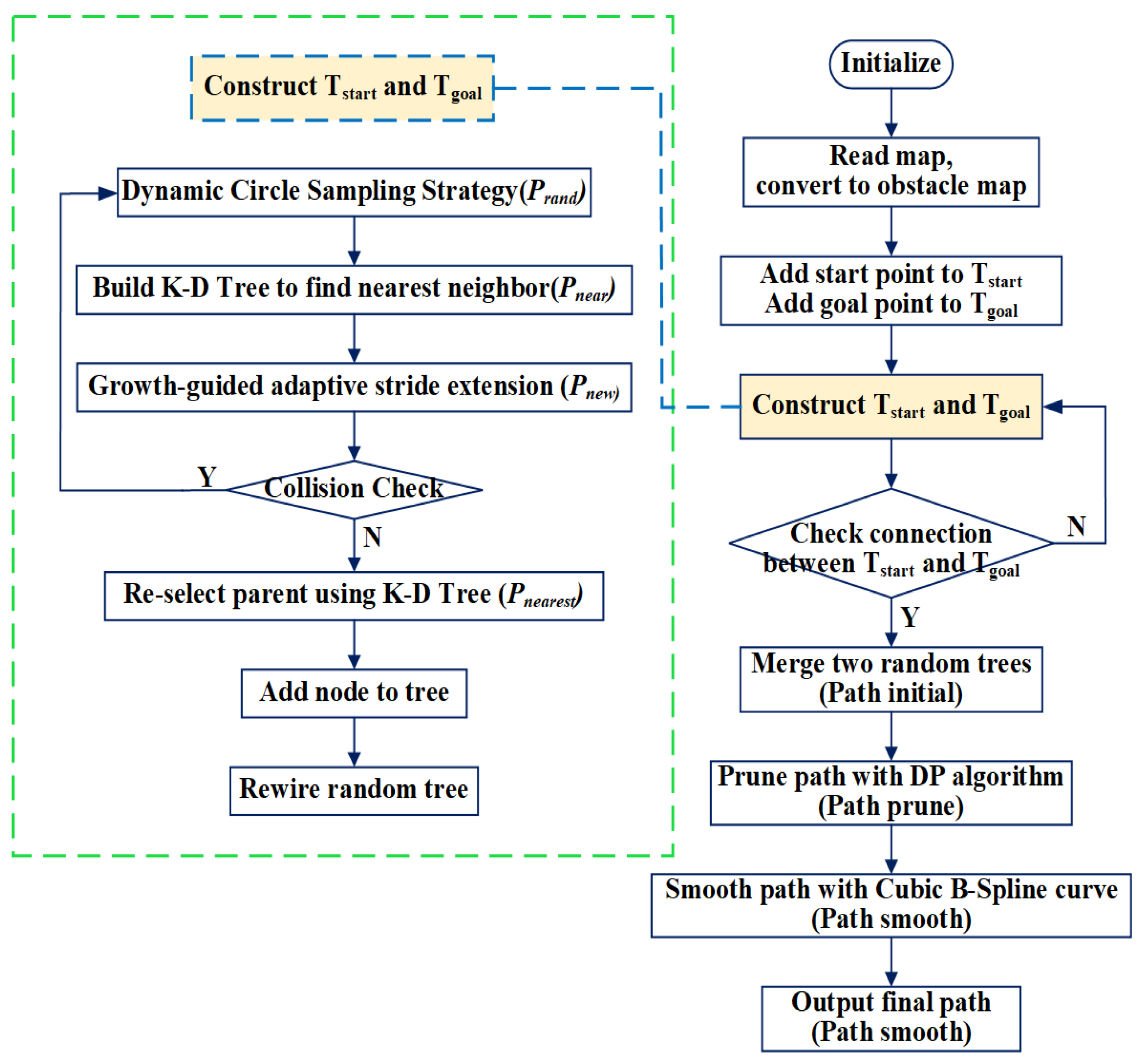

3.7. Algorithm Implementation

- Initialize: Map information, parameters, start (), and goal () are loaded. Initialize trees: with and with .

- Sample: For the current tree (e.g., ), generate sampling points within the dynamic circular sampling region with center and radius (Section 3.2, Equations (3) and (4)).

- Find Nearest Neighbor (): Using the KD-Tree (Section 3.1) built for the current tree, perform a nearest neighbor search to find closest to .

- Steer: Generate a new node using the growth guidance model (Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, Equations (6)–(8)) with the adaptive step size (Equation (9)).

- Collision Check: Verify if is collision-free and if the path segment connecting to is collision-free (Section 3.5).

- Re-select Parent: If collision-free, use the KD-Tree to find the set of potential parent nodes near . Select the node that provides the minimum cost path to and set it as the parent of .

- Add Node: Add the valid to the current tree.

- Rewire the tree: For nodes in , check if connecting them to provides a lower-cost path. If so, rewire their parent to .

- Check Connection: Check if the latest added node in and the latest added node in can connect (distance between them less than or equal to connection threshold or the latest added node in is near a node in or the latest added node in is near a node in ) via a collision-free path.

- Tree Connection: If connected, merge the trees and at the connection point to form the initial path . If not connected, return to Step 2 and continue constructing two trees.

- Path Pruning: Apply the DP algorithm (Section 3.6) to using threshold to remove redundant points, yielding the simplified path .

- Path Smoothing: Apply cubic B-spline fitting (Section 3.6, Equations (13) and (14)) to generate the final smooth path .

- Output: Return the optimized path .

3.8. Computational Complexity Analysis of KDB-RRT*

4. Algorithm Testing and Simulation

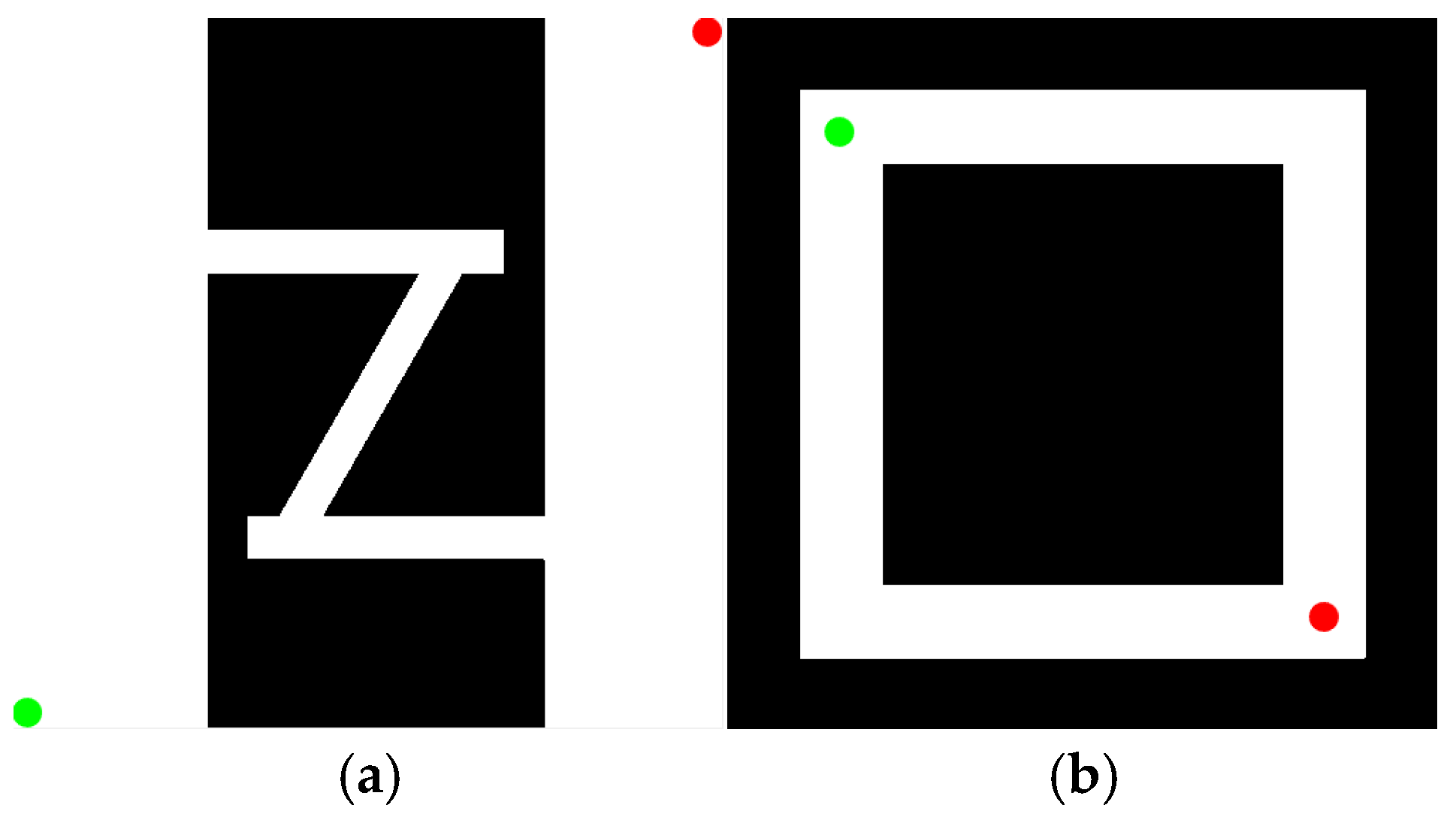

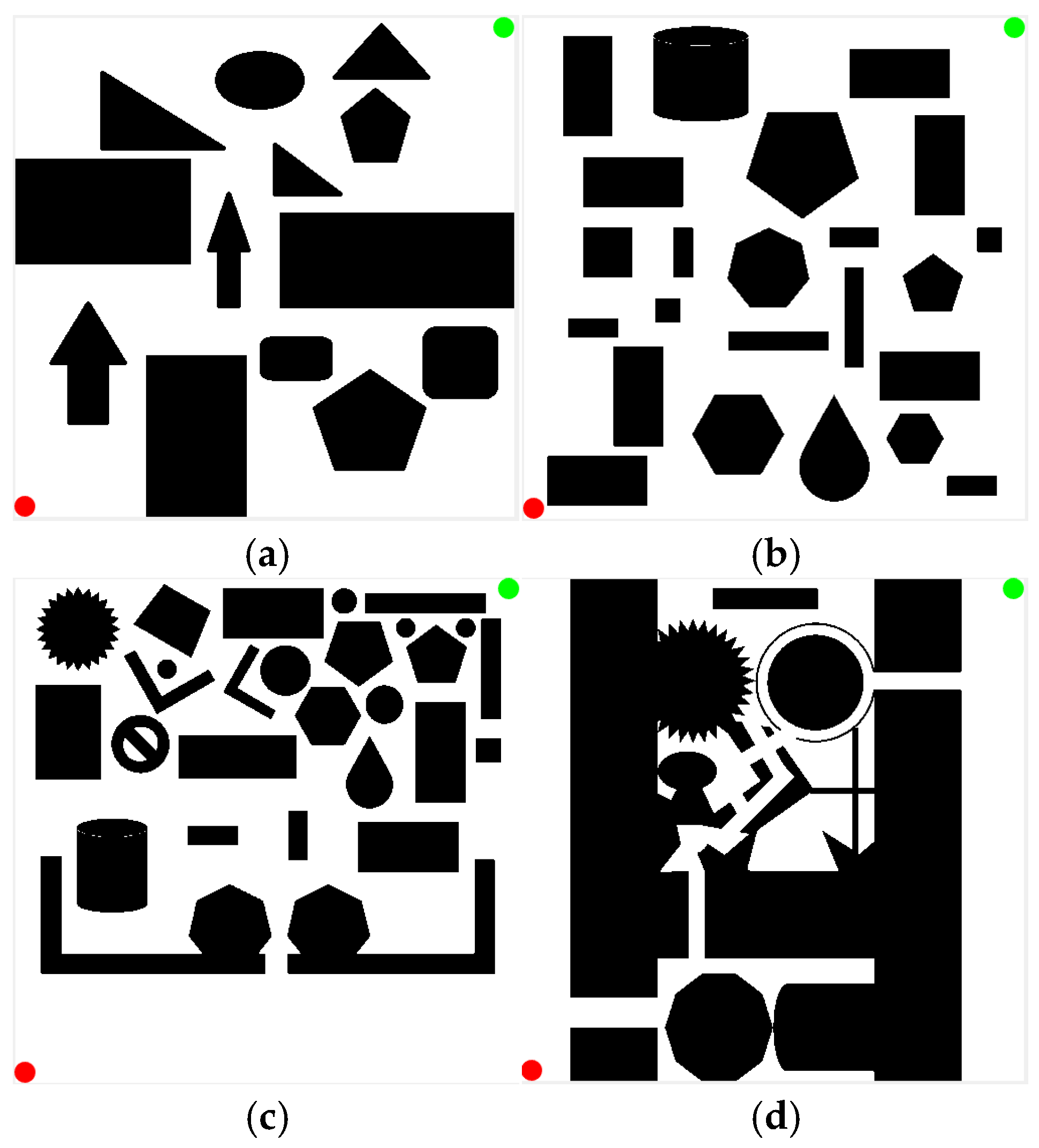

4.1. Simulation Experiment Design

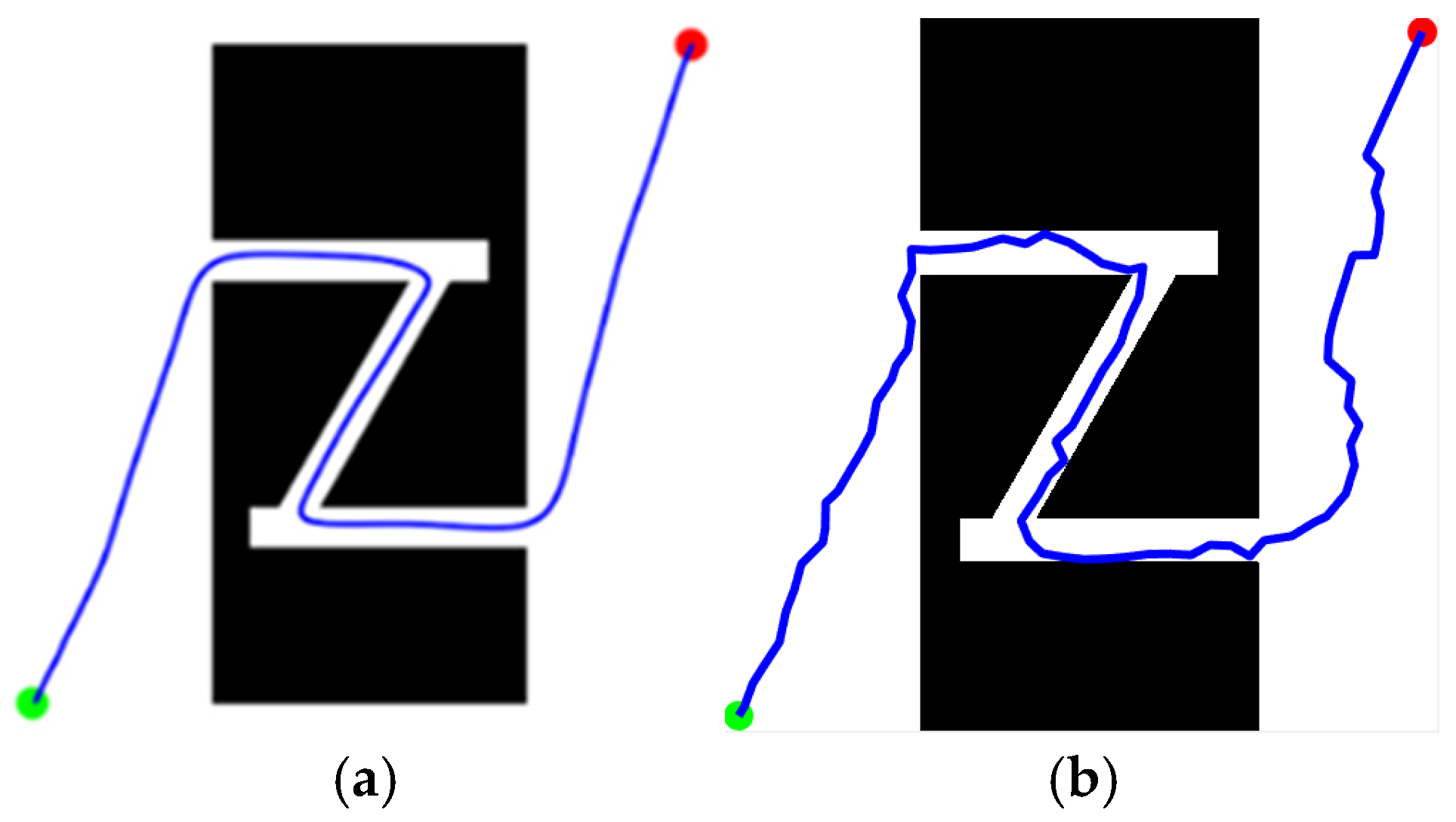

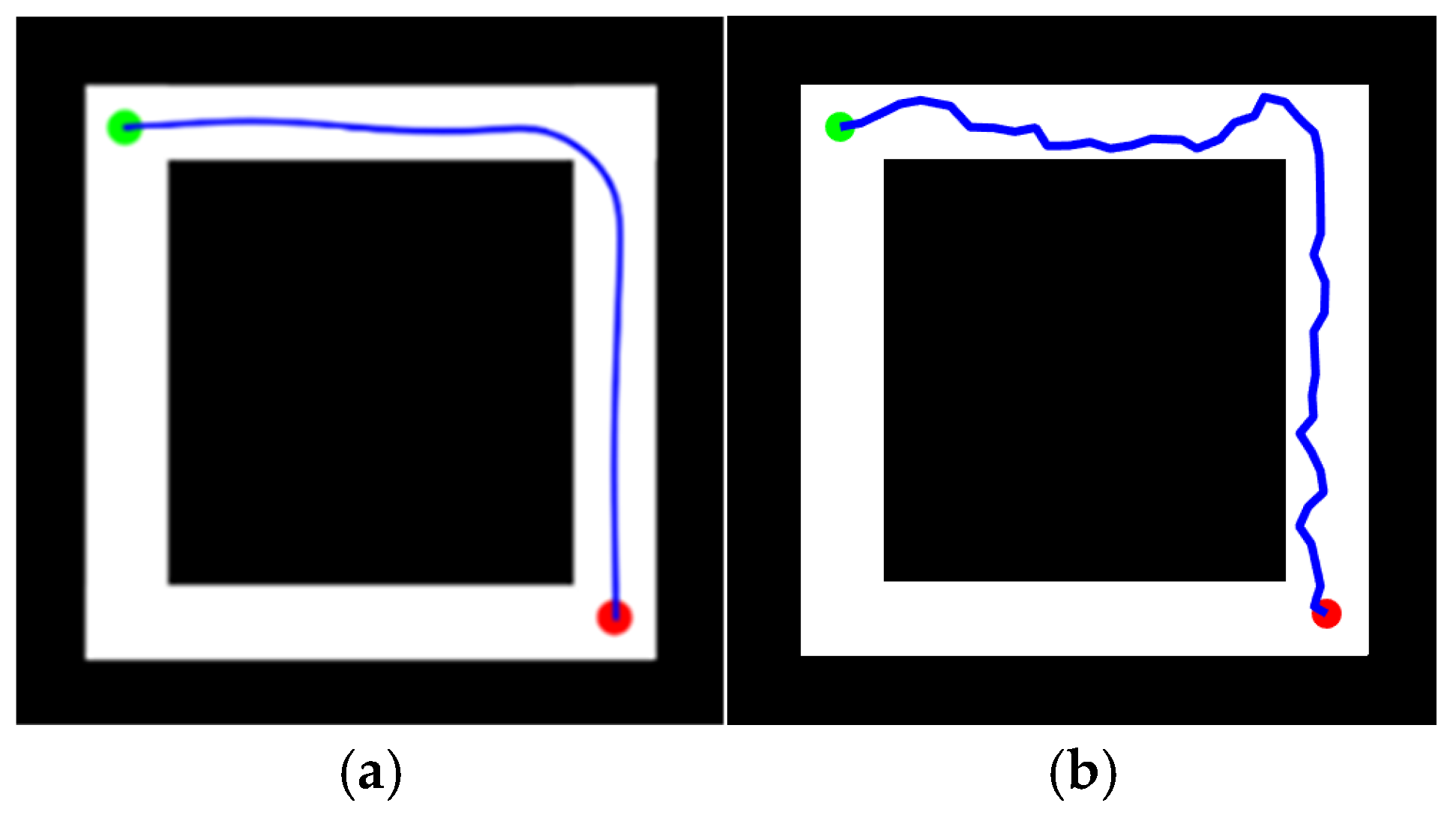

4.2. Feasibility of KDB-RRT*

4.3. Superiority of KDB-RRT*

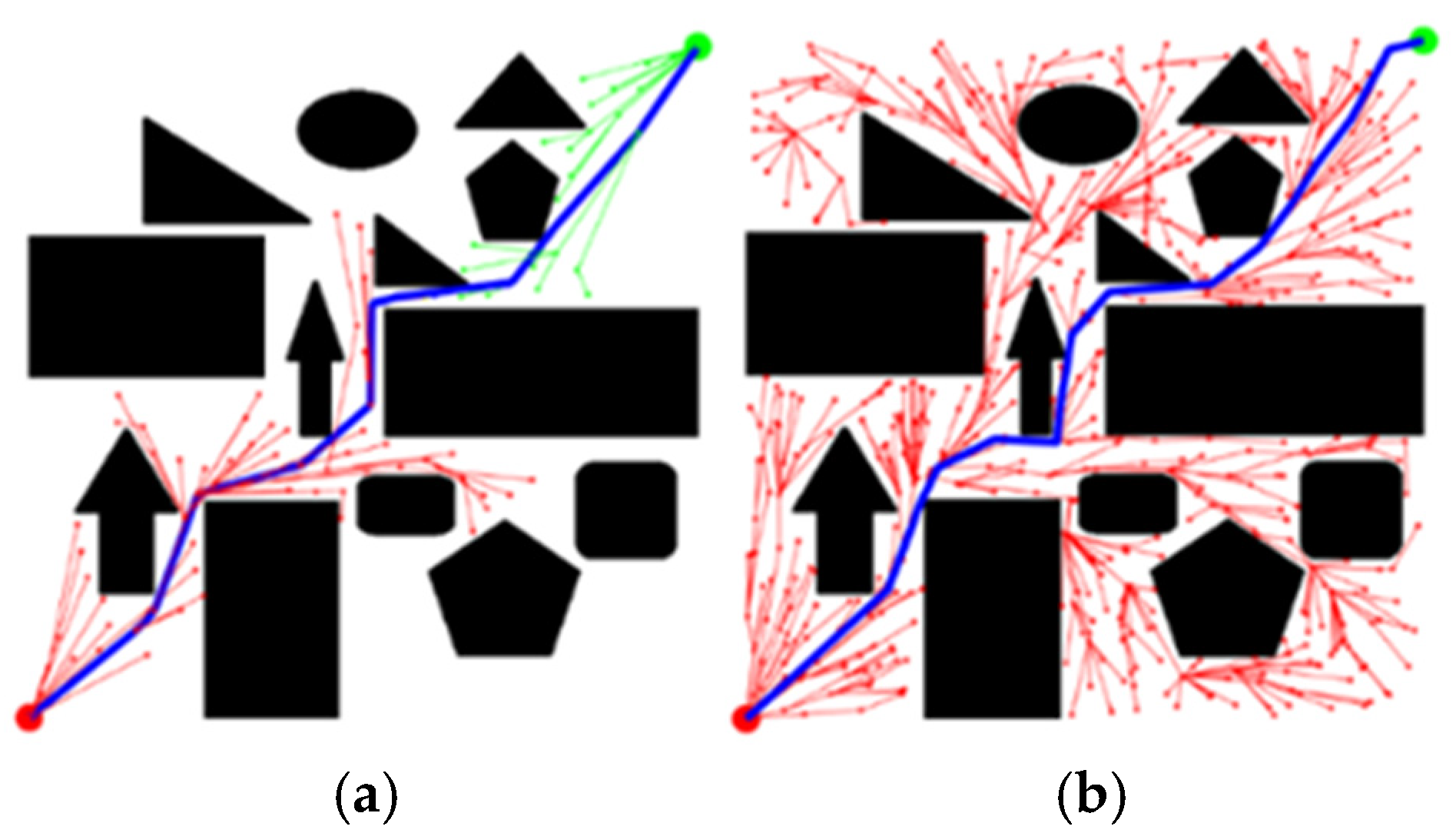

4.3.1. Superiority of KD-Tree Integration

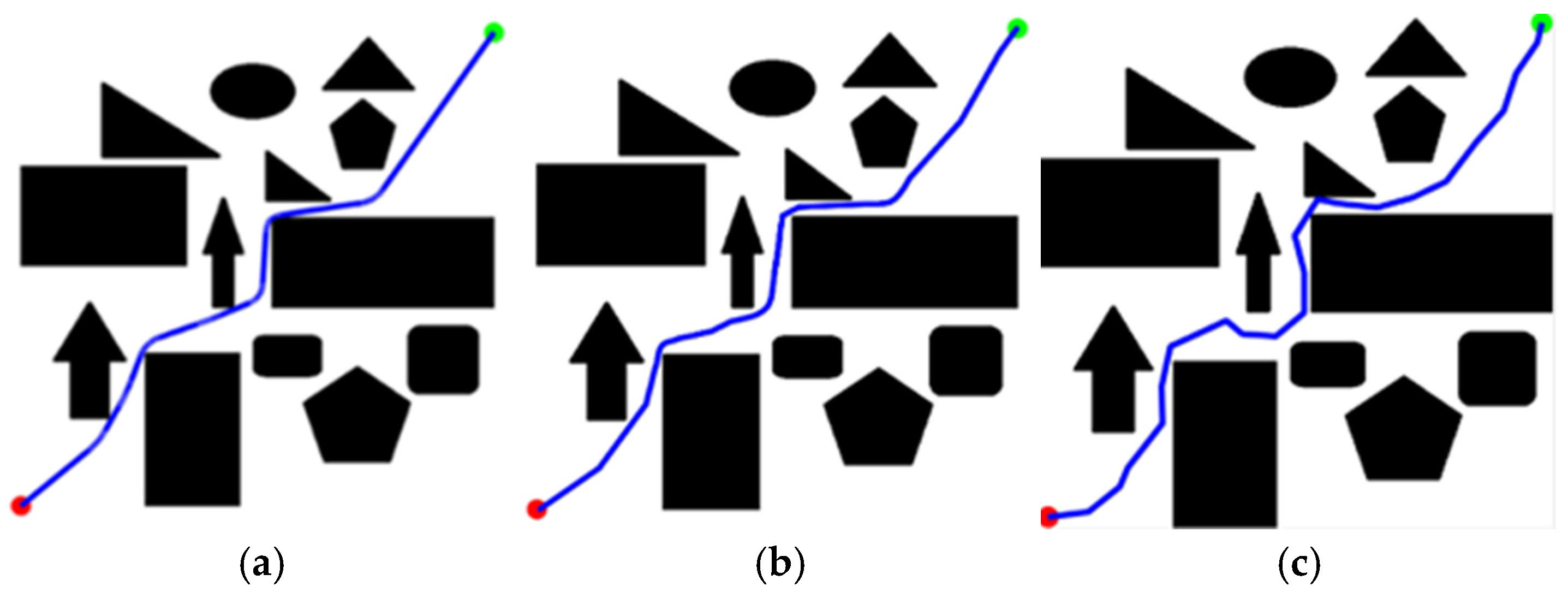

4.3.2. Superiority of DP Pruning

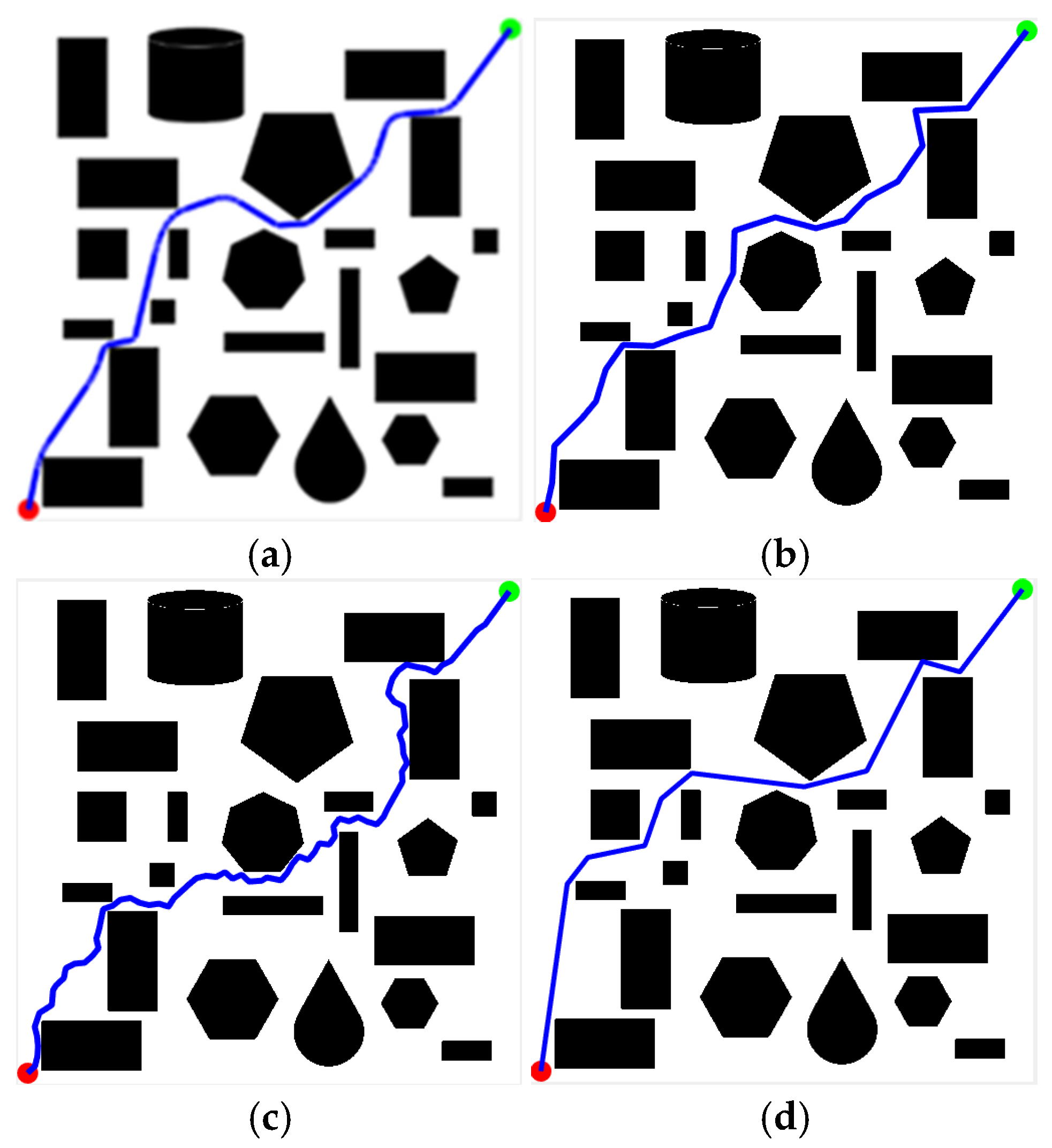

4.3.3. Simulation Experiment Based on KDB-RRT*

4.4. Agent Path Planning Experiments Based on KDB-RRT*

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Path planning techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: A review, solutions, and challenges. Comput. Commun. 2020, 149, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.J.; Yin, Y.K.; Li, Y.X.; Yu, X.T.; Zhang, P. Mobile robot path planning integrating improved A and TEB algorithms. J. Henan Univ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 44, 57–65+7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.Y.; Fu, Z.M.; Tao, F.Z.; Si, P.J.; Song, S.Z. Research on intelligent vehicle obstacle avoidance algorithm based on improved artificial potential field. J. Henan Univ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 28–34+41+5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, G.Y.; Guan, H.S.; Zheng, B.G. Improved RRT path planning algorithm based on multi-sampling heuristic strategy. Comput. Meas. Control 2024, 32, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Shi, M.H.; Han, Y.X.; Li, Y.S.; Tian, Z.K. Global route planning model for unmanned surface vehicle based on improved ant colony algorithm. J. Henan Univ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 45, 50–56+118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Ni, X.C.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Du, B.W. Research progress of mobile robot path planning algorithms. Intell. Comput. Appl. 2024, 14, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.Z.; Tu, H.Y.; Song, M.J. Robot path planning algorithm based on improved RRT. Modul. Mach. Tool Autom. Manuf. Tech. 2024, 6, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, B.H.; Godage, I.S.; Kanj, I. RRT*-based path planning for continuum arms. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 6830–6837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, H.; Yi, Q.; Zheng, K.; Gu, T. An improved rrt* path planning algorithm for service robot. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 1824–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X. Improved RRT-connect based path planning algorithm for mobile robots. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145988–145999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.Y.; Fang, L.Q.; Li, Y.N.; Su, X.J. Research on unmanned target vehicle path planning based on improved RRT algorithm. J. Gun Launch Control 2024, 45, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Sangrok, S. Safe Trajectory Path Planning Algorithm Based on RRT* While Maintaining Moderate Margin from Obstacles. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 2023, 21, 3540–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.L.; Liu, Y.; Yue, G.; Sun, S.W.; Li, T.S.; Fu, Y.Y. Fast path planning based on improved RRT algorithm. J. Ordnance Equip. Eng. 2022, 43, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Li, S. Adaptive path planning algorithm based on IRRT-Connect. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2024, 47, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.J.; Li, Z.W.; Luo, C. Safe and smooth path generation for mobile robot based on RRT algorithm. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2024, 47, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.G.; Liu, H.W.; Luo, T.; Wang, Z.M. RRT algorithm path optimization and simulation verification. J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. 2022, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.L.; Shi, H.W. Improved DBSCAN clustering algorithm based on KD-tree. Comput. Syst. Appl. 2022, 31, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, D.W.; Li, J.Z. Optimization of k-means clustering algorithm based on KD-tree. Intell. Comput. Appl. 2021, 11, 194–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yoon, S.; Lee, Y. A Hybrid Approach Combining R*-Tree and k-d Trees to Improve Linked Open Data Query Performance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, X.J.; Zhang, J. Grid k-d tree approach for point location in polyhedral data sets—Application to explicit MPC. Int. J. Control 2020, 93, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W. Research on Path Planning and Tracking Control for Automatic Parking in Complex Environments; Jilin Institute of Chemical Technology: Jilin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S.; Lyu, Y.M.; Wu, H.B. An interactive learning method for robot obstacle avoidance based on DP-KMP. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2024, 45, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Hou, M.; Zhang, X.D. Path planning for mobile robots based on improved RRT combined with B-spline. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2022, 45, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

| Algorithmic Step | KDB-RRT* | RRT* | Optimization Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest-neighbor query | KD-tree spatial partitioning (Section 3.1) | ||

| Collision detection | R-tree indexing + SAT pre-check (Section 3.5) | ||

| Rewiring operation | Optimized neighborhood retrieval (Steps 6 & 8) | ||

| Total per iteration | Hierarchical spatial indexing | ||

| Asymptotic | Bidirectional search + multi-layer optimization | ||

| Path pruning | ~ | Douglas–Peucker algorithm (Section 3.6.1) | |

| Path smoothing | ~ | Cubic B-spline fitting (Section 3.6.2) |

| Algorithm | KDB-RRT* | Optimized RRT* |

|---|---|---|

| Average planning time/s | 4.10 | 13.77 |

| Average path length/cm | 1258.25 | 1321.92 |

| Average number of path nodes | 269 | 827 |

| Node utilization | 54.7% | 38.5% |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 5.23 | 2.17 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 4.69 | 1.36 |

| Algorithm | KDB-RRT* | Optimized RRT* |

|---|---|---|

| Average planning time/s | 0.85 | 3.04 |

| Average path length/cm | 646.47 | 721.08 |

| Average number of path nodes | 70 | 230 |

| Node utilization | 81.4% | 67.9% |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 4.36 | 1.89 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 3.74 | 1.27 |

| Algorithm | KDB-RRT* | Optimized RRT* |

|---|---|---|

| Average planning/s | 1.13 | 12.95 |

| Average path/cm | 747.06 | 790.79 |

| Average | 97 | 1075 |

| Node utilization | 80.41% | 41.02% |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 2.56 | 1.63 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 1.38 | 1.24 |

| Algorithm | DP Pruning | Triangle Pruning | Before Pruning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average path length/cm | 742.23 | 757.18 | 762.74 |

| Average number of inflection points | 5 | 11 | 18 |

| Average processing time/s | 0.67 | 1.12 | ~ |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 2.48 | 2.65 | 2.37 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 1.65 | 1.71 | 1.62 |

| Algorithm | KDB-RRT* | Optimized RRT* | RRT*-Connect | Informed-RRT* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average planning time/s | 1.11 | 26.68 | 24.34 | 4.86 |

| Average path length/cm | 774.89 | 783.60 | 835.66 | 780.14 |

| Average number of inflection points | 9 | 26 | 41 | 10 |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 2.05 | 1.72 | 1.68 | 2.23 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 1.39 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.41 |

| Planning success rate | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Algorithm | KDB-RRT* | Optimized RRT* | RRT*-Connect | Informed-RRT* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average planning time/s | 1.17 | 46.76 | 37.16 | 8.26 |

| Average path length/cm | 792.48 | 866.32 | 844.52 | 812.37 |

| Average number of inflection points | 4 | 25 | 42 | 10 |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 4.12 | 1.98 | 1.85 | 4.37 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 3.69 | 1.35 | 1.32 | 3.82 |

| Planning success rate | 100% | 68% | 72% | 100% |

| Algorithm | KDB-RRT* | Optimized RRT* | RRT*-Connect | Informed-RRT* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average planning time/s | 1.96 | 94.77 | 48.57 | 8.58 |

| Average path length/cm | 791.88 | 866.13 | 1007.24 | 809.31 |

| Average number of inflection points | 9 | 24 | 59 | 15 |

| Average distances to obstacles/cm | 3.05 | 2.13 | 1.97 | 2.68 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/cm | 2.42 | 1.57 | 1.38 | 2.04 |

| Planning success rate | 100% | 28% | 36% | 98% |

| Algorithm | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Average path length/m | 3.23 | 6.72 |

| Average planning time/s | 0.78 | 1.64 |

| Average traveling time of UGV/s | 1.46 | 3.08 |

| Average distances to obstacles/dm | 3.5 | 2.7 |

| Minimum distances to obstacles/dm | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| Whether a collision occurs | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, W.; Wei, K.; Zhang, J. A Novel Method of Path Planning for an Intelligent Agent Based on an Improved RRT* Called KDB-RRT*. Sensors 2025, 25, 7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247545

Wei W, Wei K, Zhang J. A Novel Method of Path Planning for an Intelligent Agent Based on an Improved RRT* Called KDB-RRT*. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247545

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Wenqing, Kun Wei, and Jianhui Zhang. 2025. "A Novel Method of Path Planning for an Intelligent Agent Based on an Improved RRT* Called KDB-RRT*" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247545

APA StyleWei, W., Wei, K., & Zhang, J. (2025). A Novel Method of Path Planning for an Intelligent Agent Based on an Improved RRT* Called KDB-RRT*. Sensors, 25(24), 7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247545