Seafood Object Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Methods

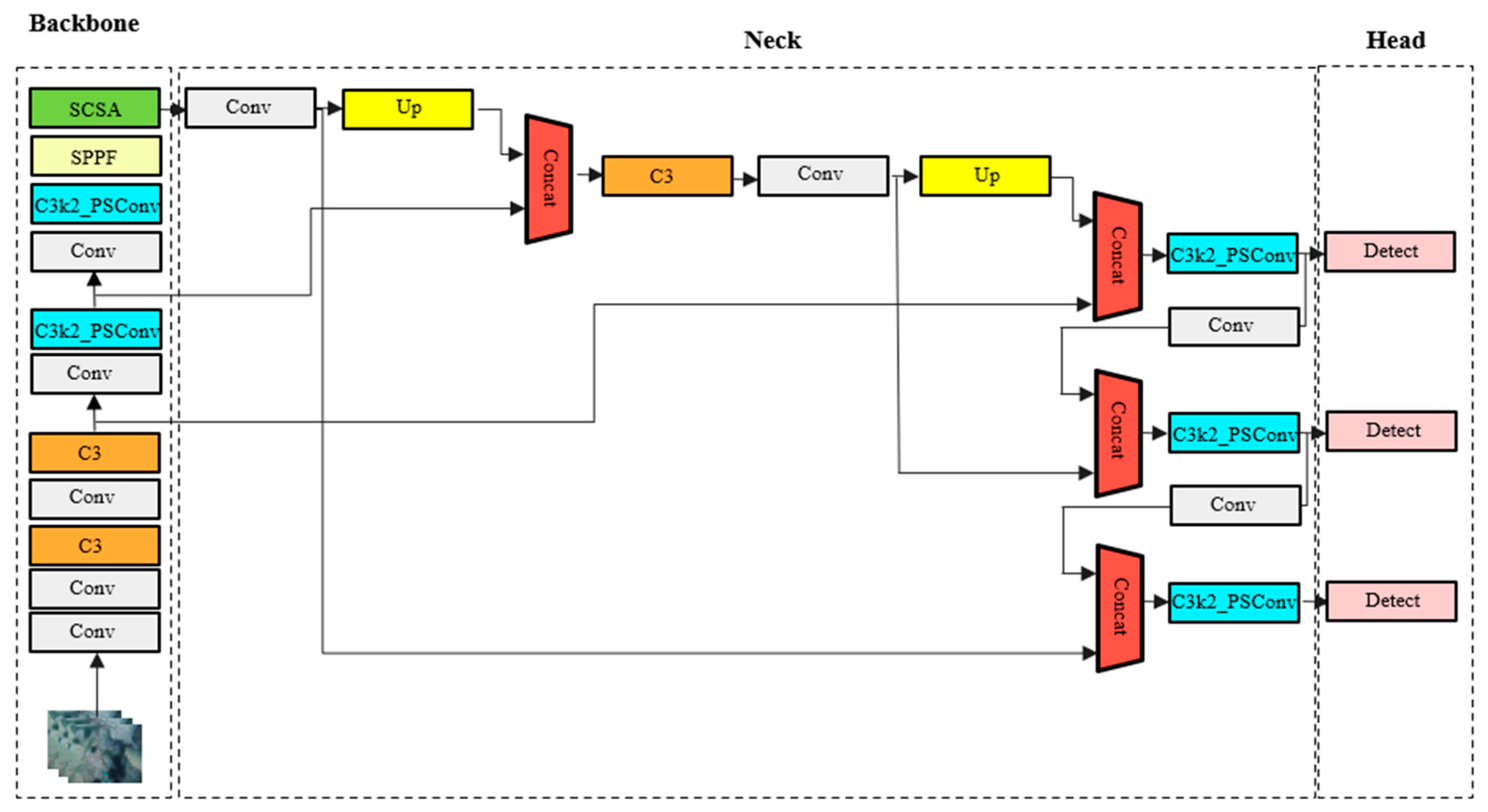

3.1. Network Architecture

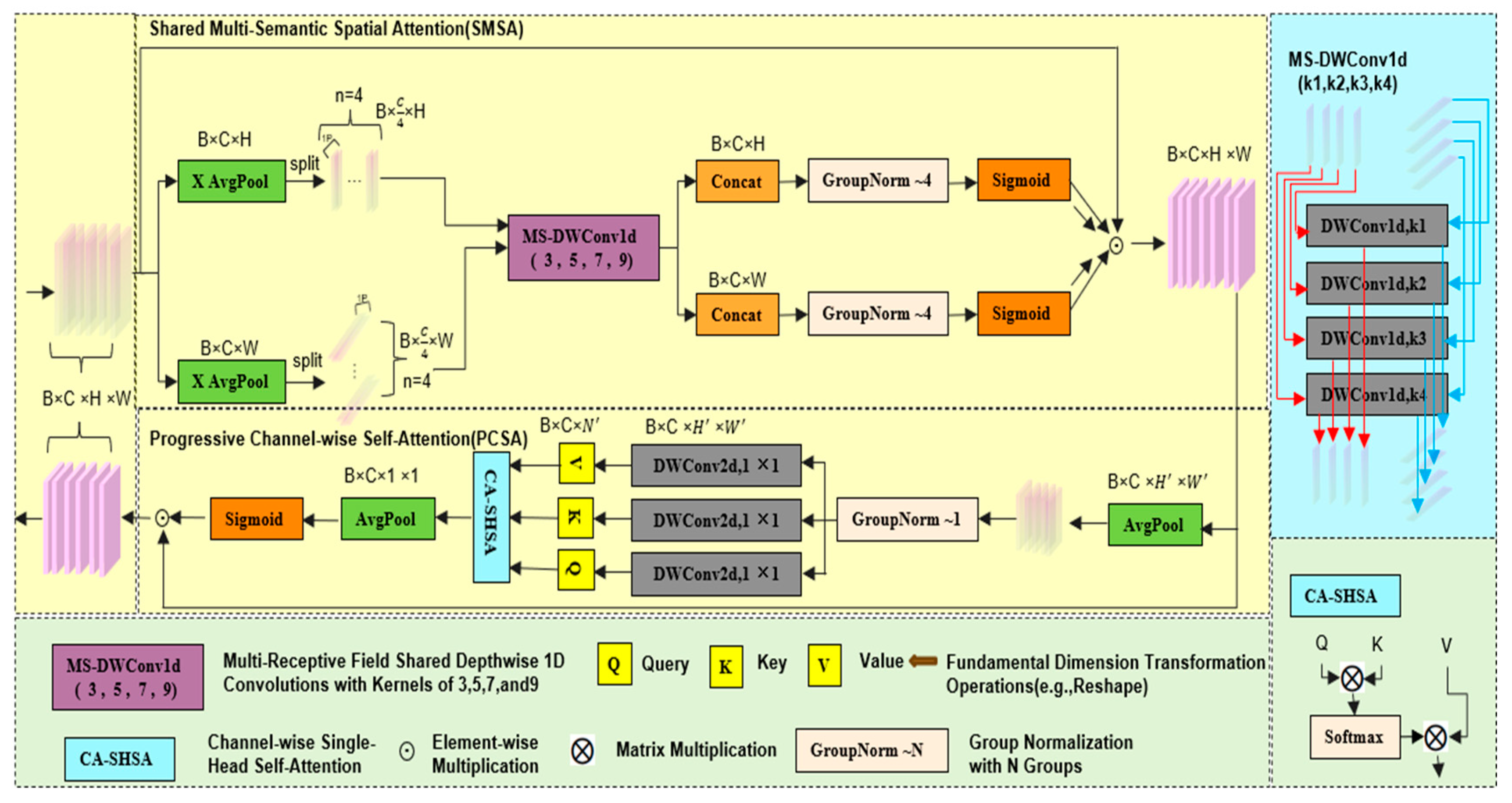

3.2. Spatial–Channel Synergistic Attention (SCSA)

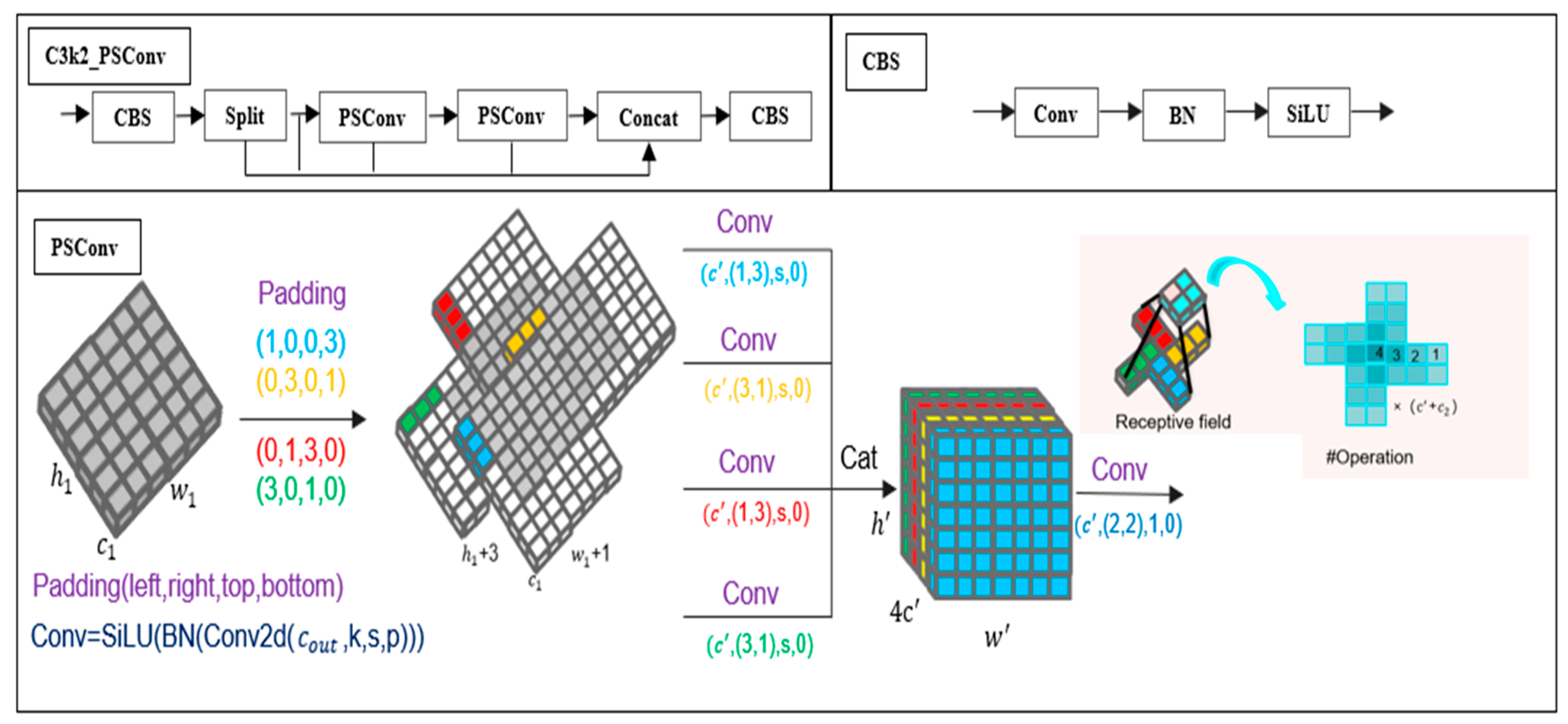

3.3. Three-Scale Convolution Dual-Path Variable-Kernel Module Based on Pinwheel-Shaped Convolution (C3k2-PSConv)

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Environment Configuration

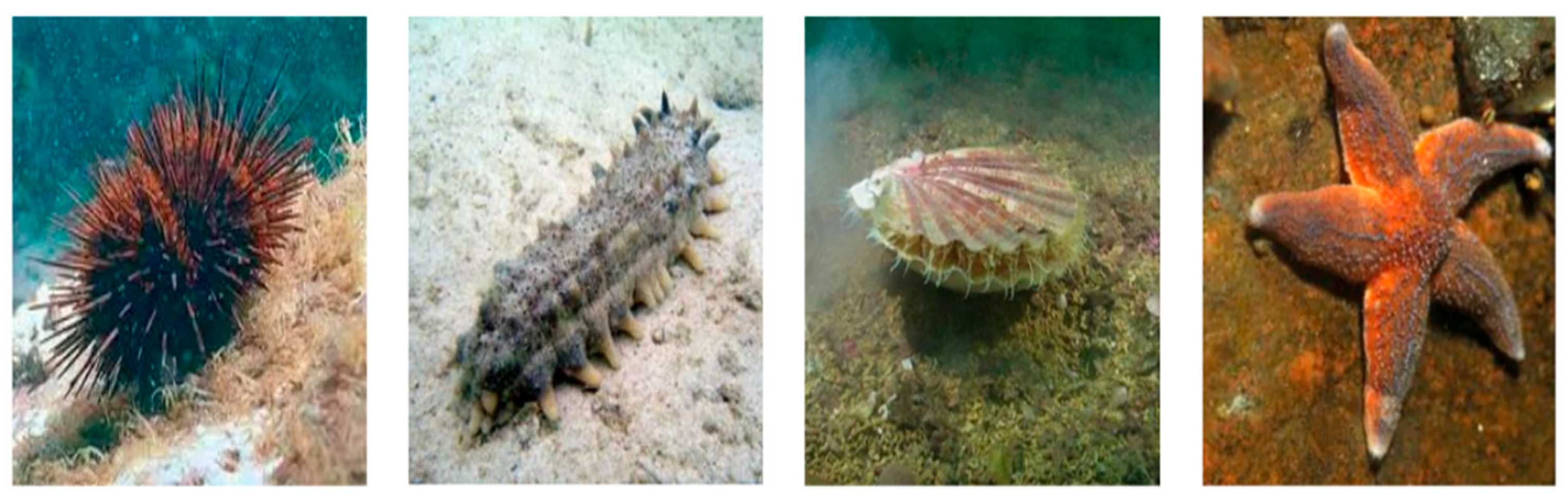

4.2. Dataset

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Analysis of Experimental Results

4.4.1. Impact of Different Improvement Strategies on Detection Performance

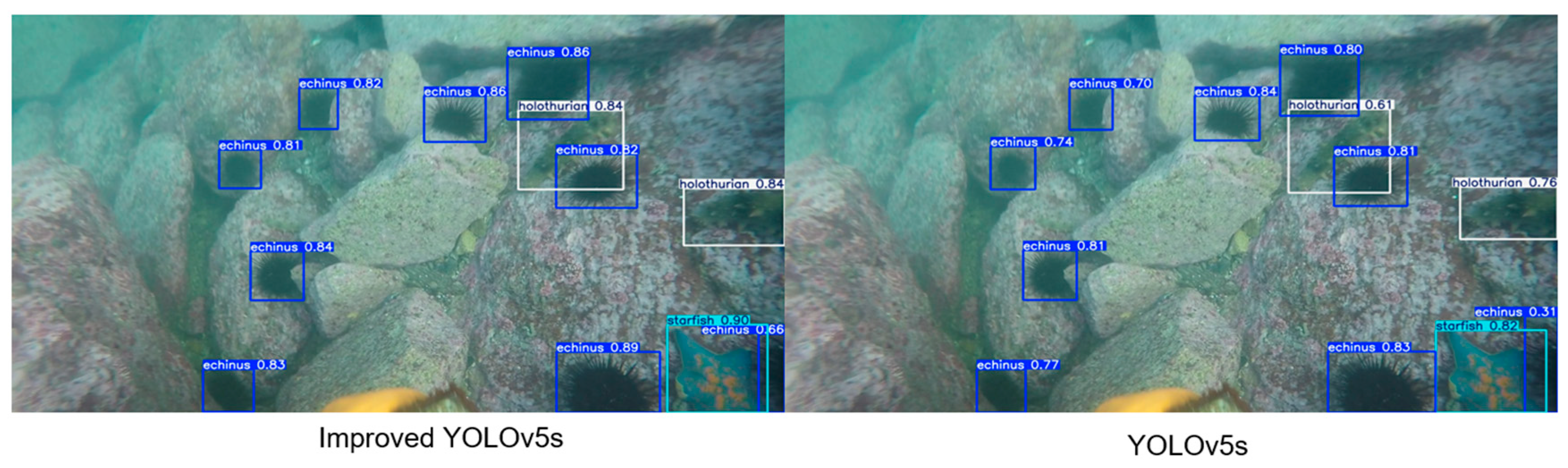

4.4.2. Qualitative Comparison

4.4.3. Comparison with Different Models

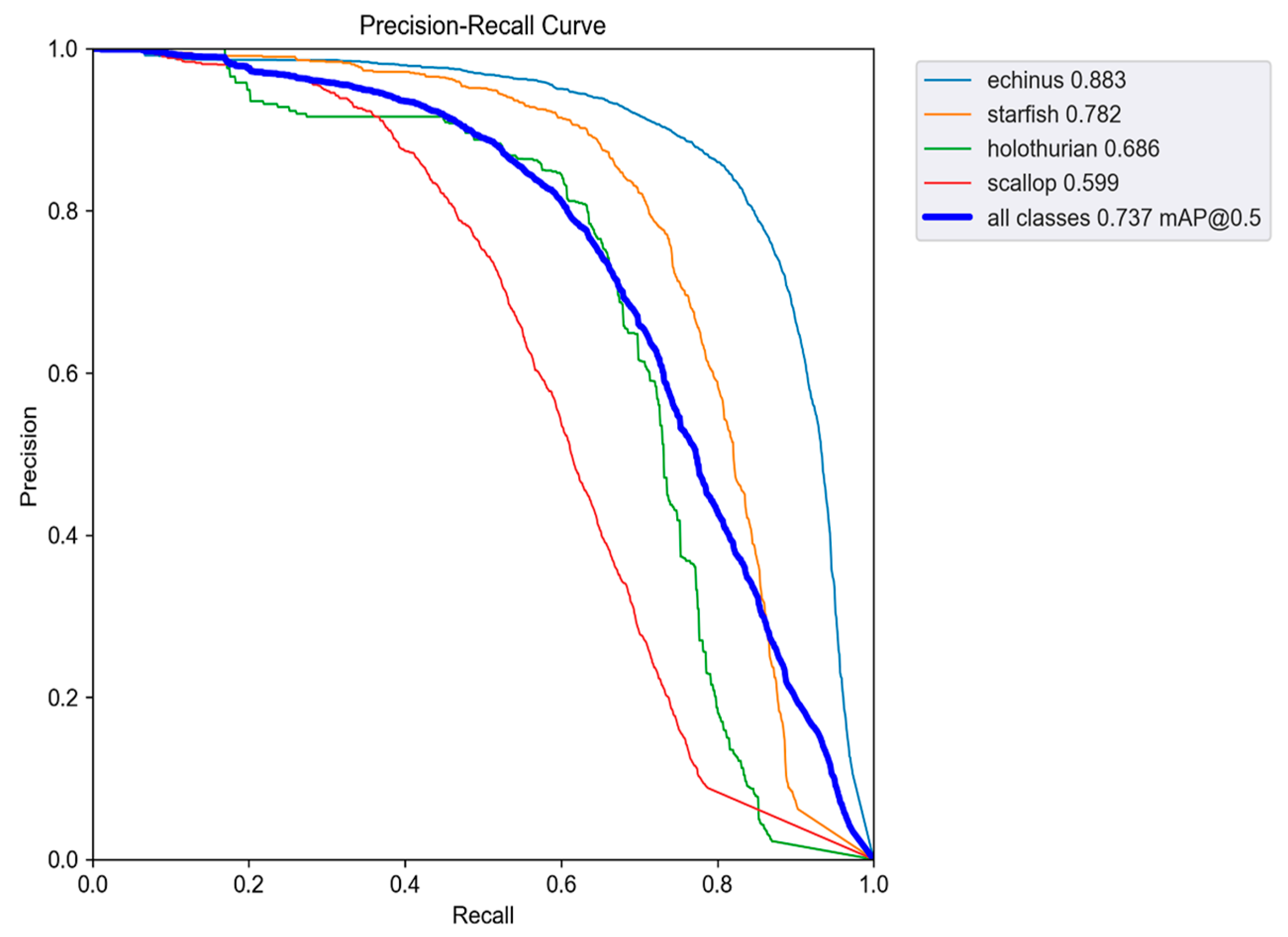

4.4.4. Category-Wise Detection Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Si, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H. SCSA: Exploring the synergistic effects between spatial and channel attention. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Su, X.; Hai, N.; Huang, X. Pinwheel-shaped convolution and scale-based dynamic loss for infrared small target detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; pp. 9202–9210. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2005 IEEE, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.H.; Lin, C.J.; Schölkopf, B. A tutorial on ν-support vector machines. Appl. Stoch. Models Bus. Ind. 2005, 21, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, C.; Chen-Burger, Y.H.; Nadarajan, G.; Fisher, R.B. Detecting, Tracking and Counting Fish in Low Quality Unconstrained Underwater Videos; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 514–519. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, K.; Hou, W.; Wang, S. Image feature detection and matching in underwater conditions. In Proceedings of the Ocean Sensing and Monitoring II, Orlando, FL, USA, 5–6 April 2010; pp. 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, T.; Mardiyanto, R.; Purwanto, D. Development of underwater object detection method base on color feature. In Proceedings of the CENIM 2018 IEEE, Surabaya, Indonesia, 26–27 November 2018; pp. 254–259. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2014 IEEE, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the ICCV 2015 IEEE, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the ICCV 2017 IEEE, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2016 IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2017 IEEE, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2023 IEEE, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2016 IEEE, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the ICCV 2017 IEEE, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Niu, J. Real-time underwater fish target detection based on improved YOLO and transfer learning. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2019, 32, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, H.; Song, Y. Marine organism recognition algorithm based on improved YOLOv3 network. Comput. Appl. Res. 2020, 37, 394–397. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, B.; Chen, W.; Cong, Y.; Tian, J. Dual refinement underwater object detection network. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, F.; Miao, Z.; Li, F.; Li, Z. S-FPN: A shortcut feature pyramid network for sea cucumber detection in underwater images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 182, 115306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S. Underwater target detection algorithm based on channel attention and feature fusion. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 2022, 40, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Han, Y.; Sun, P.; Li, J. Attention-Based Lightweight YOLOv8 Underwater Target Recognition Algorithm. Sensors 2024, 24, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, H.; Shu, X. BSE-YOLO: An Enhanced Lightweight Multi-Scale Underwater Object Detection Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, A.; Fu, Q. MAS-YOLOv11: An Improved Underwater Object Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv11. Sensors 2025, 25, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Environment Component | Configuration Details |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows11 |

| CPU | 13th Gen Intel® CoreTM i7-13650HX |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 |

| Framework | PyTorch2.0.1 |

| CUDA Version | Cuda 12.6 |

| Programming Language | Python 3.8 |

| Parameter Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Batch Size | 16 |

| Number of Epochs | 200 |

| Input Image Size | 640 × 640 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Initial Learning Rate | 0.01 |

| Momentum | 0.937 |

| Weight Decay | 0.0005 |

| Warm-up Epochs | 3 |

| Baseline Model | SCSA | C3k2-PSConv | P(Precision)/% | R(Recall)/% | mAP(%) | Parameters (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5s | × | × | 78.8 | 63.3 | 71.4 | 7.02 |

| √ | × | 79.5 | 65.2 | 72.5 | 7.03 | |

| × | √ | 79.1 | 65.5 | 72.8 | 6.83 | |

| √ | √ | 80.1 | 66.3 | 73.7 | 6.85 | |

| YOLOv10n | × | × | 79.3 | 65.3 | 72.4 | 2.70 |

| √ | × | 78.7 | 64.0 | 70.2 | 2.59 | |

| × | √ | 78.2 | 64.6 | 69.2 | 2.58 | |

| √ | √ | 74.0 | 63.9 | 68.8 | 2.59 | |

| YOLOv11n | × | × | 78.7 | 64.5 | 71.9 | 2.59 |

| √ | × | 77.8 | 63.6 | 69.7 | 2.59 | |

| × | √ | 76.7 | 63.3 | 69.3 | 2.45 | |

| √ | √ | 74.1 | 62.8 | 68.5 | 2.45 |

| Model | AP(%) | mAP(%) | FPS (Frames per Second) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echinus | Starfish | Holothurian | Scallop | |||

| Faster-RCNN | 83.7 | 79.5 | 61.4 | 54.3 | 69.7 | 28.4 |

| SSD | 86.7 | 77.5 | 63.4 | 58.3 | 71.5 | 35.6 |

| Yolov3 | 85.3 | 78.8 | 61.8 | 56.2 | 70.5 | 56.4 |

| Yolov5s | 87.1 | 77.1 | 65.4 | 55.2 | 71.2 | 221.7 |

| Yolov8n | 86.0 | 75.7 | 62.0 | 60.7 | 71.1 | 173.2 |

| Yolov10n | 85.4 | 76.0 | 67.0 | 61.5 | 72.4 | 169.5 |

| Yolov11n | 86.7 | 77.3 | 65.8 | 58.0 | 71.9 | 116.7 |

| Yolov5s-Improve | 88.3 | 78.2 | 68.6 | 59.9 | 73.7 | 225.3 |

| Seafood Category | Algorithm | Precision (P) | Recall (R) |

|---|---|---|---|

| echinus | YOLOv5s | 0.817 | 0.767 |

| YOLOv5s-Improve | 0.841 | 0.82 | |

| starfish | YOLOv5s | 0.825 | 0.748 |

| YOLOv5s-Improve | 0.837 | 0.751 | |

| holothurian | YOLOv5s | 0.751 | 0.572 |

| YOLOv5s-Improve | 0.824 | 0.654 | |

| scallop | YOLOv5s | 0.646 | 0.464 |

| YOLOv5s-Improve | 0.797 | 0.475 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, N.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xie, Z. Seafood Object Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Sensors 2025, 25, 7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247546

Zhu N, Liu Z, Wang Z, Xie Z. Seafood Object Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247546

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Nan, Zhaohua Liu, Zhongxun Wang, and Zheng Xie. 2025. "Seafood Object Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247546

APA StyleZhu, N., Liu, Z., Wang, Z., & Xie, Z. (2025). Seafood Object Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Sensors, 25(24), 7546. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247546