Edge Temporal Digital Twin Network for Sensor-Driven Fault Detection in Nuclear Power Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Continuous variable temporal representation. We introduce a novel continuous-variable time series modeling approach, in which the input data are no longer static or uniformly sampled but represented as continuous non-equidistant temporal variables. Time is incorporated as a probabilistic condition in variational inference, enabling the digital twin to learn temporal dependencies beyond discrete sampling intervals. This provides a theoretical advancement in representing irregular temporal dynamics for sensor-driven systems and significantly enhances time-domain generalization.

- Global representation-based digital twin module. A new global representation module is designed to mitigate the non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) nature of nuclear power data. Through cloud–edge collaboration, each subsystem independently trains its local model and contributes to a unified global digital twin without data sharing. This design realizes privacy-preserving global knowledge transfer across heterogeneous nuclear subsystems.

- Temporal attention representation mechanism. We further propose a temporal attention mechanism embedded within a graph neural network in the latent space, which for the first time models temporal evolution as graph evolution. This mechanism allows ETDTN to capture non-Euclidean temporal dependencies between historical and future states, offering stronger interpretability and generalization than conventional self-attention architectures.

2. Related Work

3. Edge Temporal Digital Twin Network

3.1. Digital Twin Autoregressive Training in Nuclear Power System

3.2. Mapping of Edge Time Series Samples

3.3. Input and Encoding of Edge Device Samples

3.4. Cloud-Edge Collaborative Temporal Attention Representation

3.5. Decoding Stage

4. Experiment

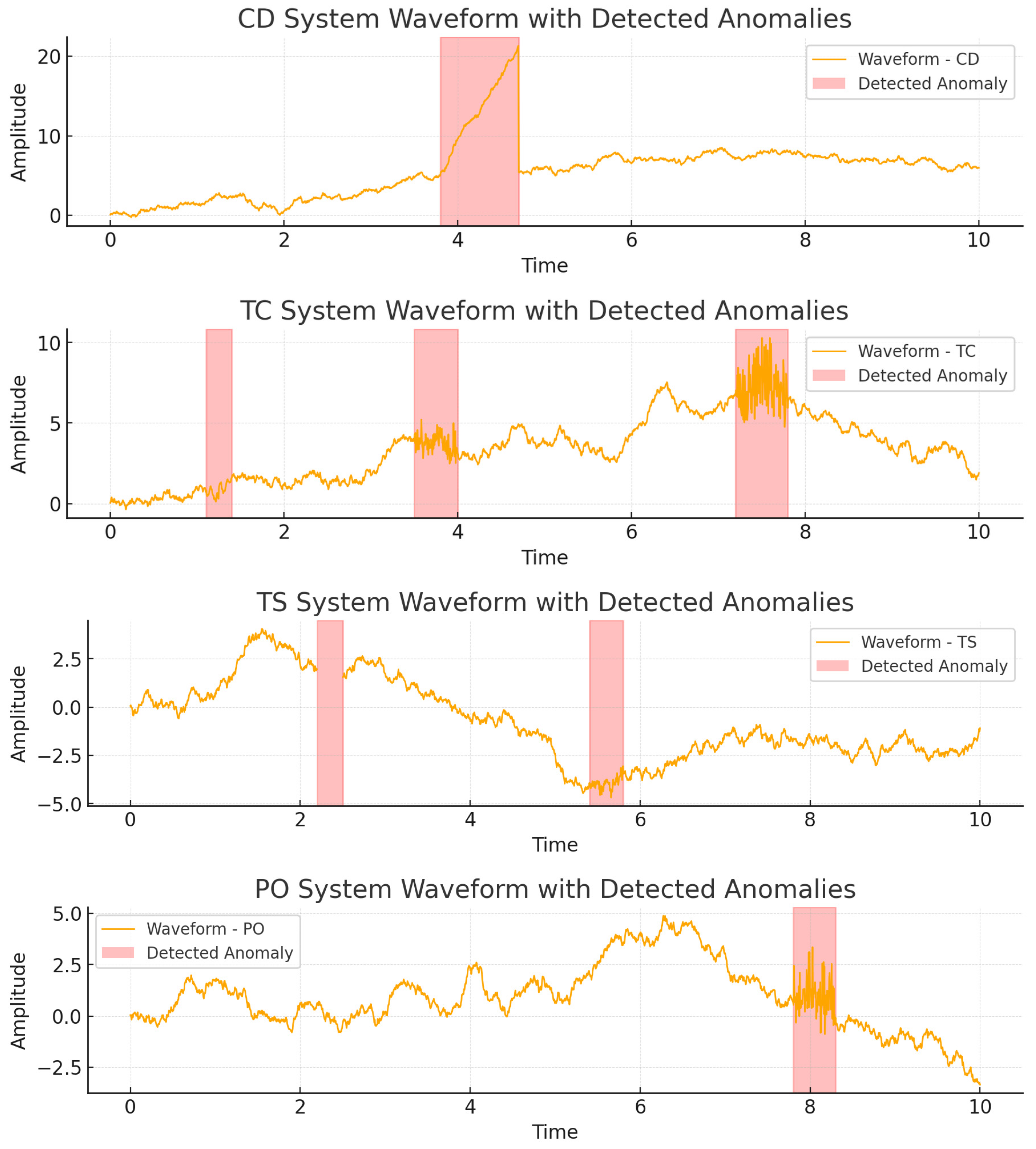

4.1. Fault Detection

4.2. Ablation Experiment

4.3. Parameter Analysis

4.4. Training Efficiency and Communication Overhead

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ozcanli, A.K.; Yaprakdal, F.; Baysal, M. Deep learning methods and applications for electrical power systems: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 7136–7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Xiao, B.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ji, P. Digital twin modeling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Dou, Z.; Cai, Y.; Li, W.; Lei, X.; Han, D. Digital twin and its application in power system. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE), Shanghai, China, 12–14 September 2020; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodavand, F.; Ramaji, I.J.; Sadeghi, N. Digital twin for fault detection and diagnosis of building operations: A systematic review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, C.; Ruan, C.; Zhang, L.; Hu, P.; Xiang, T. A privacy-preserving matching service scheme for power data trading. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 32296–32309.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Du, H.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Mao, S.; Han, Z.; Jamalipour, A.; Kim, D.I.; Shen, X.; et al. Unleashing the power of edge-cloud generative AI in mobile networks: A survey of AIGC services. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 1127–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Ma, G.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, M.; Teng, F.; Ding, H.; Yuan, Y. A deep learning-based remaining useful life prediction approach for bearings. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Müller, H.-G. Functional quadratic regression. Biometrika 2010, 97, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesecke, K. A simple exponential model for dependent defaults. J. Fixed Income 2003, 13, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Cao, L.; Li, R. Numerical simulation of sliding wear based on Archard model. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Mechanic Automation and Control Engineering (MACE), Xi’an, China, 6–8 June 2010; pp. 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Neto, E.A. A fast, one-equation integration algorithm for the Lemaitre ductile damage model. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2002, 18, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Zhong, M.; Li, L.; Ding, S.X. An optimal data-driven approach to distribution independent fault detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2020, 16, 6826–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Bashir, M.; Liu, Q.; Miao, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Ekere, N. A novel health indicator for intelligent prediction of rolling bearing remaining useful life based on unsupervised learning model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Alikhani, A.; Nahid-Mobarakeh, B.; Hsieh, M.F. One-dimensional LSTM-regulated deep residual network for data-driven fault detection in electric machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 3083–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakolaki, S.E.H.; Hakimian, V.; Sadeh, J.; Rakhshani, E. Comprehensive study on transformer fault detection via frequency response analysis. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 3300378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.B.; Shihabudheen, K.V. Neural architecture search algorithm to optimize deep transformer model for fault detection in electrical power distribution systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Sinaei, S.; Salcines, A.; Pampliega, D.; Clemente, R.; Lindgren, A. Anomaly detection based on LSTM and autoencoders using federated learning in smart electric grid. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2024, 193, 104951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, W.; Yuan, L.; Yu, K.; Hernández, Á.; Ureña, J.; Pang, Z. Federated learning-enabled digital twin optimization for Industrial IoT systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 370, 123523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Y. AI-enhanced digital twins for predictive maintenance: A comprehensive review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 76, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababio, I.B.; Bieniek, J.; Rahouti, M.; Hayajneh, T.; Aledhari, M.; Verma, D.K.; Chehri, A. A blockchain-assisted federated learning framework for secure digital twins in industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 8451–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh Ardebili, A.; Zappatore, M.; Ramadan, A.I.H.A.; Longo, A.; Ficarella, A. Digital Twins of Smart Energy Systems: A Systematic Literature Review on Enablers, Design, Management and Computational Challenges. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Improved adam optimizer for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM 26th International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS), Banff, AB, Canada, 4–6 June 2018; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrio, C.B.A.; Darmawan, W.; Nadia, B.U.; Hanafiah, N. Time series analysis and forecasting of coronavirus disease in Indonesia using ARIMA model and PROPHET. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 179, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Fu, S.; Storlie, C.B.; Mathis, K.L.; Larson, D.W.; Liu, H. Real-time risk prediction of colorectal surgery-related post-surgical complications using GRU-D model. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 135, 104202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Huang, C.J. Motor fault detection and feature extraction using RNN-based variational autoencoder. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 139086–139096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bao, J.; Jin, Y.; Yang, X. Learning generative RNN-ODE for collaborative time-series and event sequence forecasting. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 7118–7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 11106–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Peng, H.; Fu, J.; Ling, H. Autoformer: Searching transformers for visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12270–12280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baselines | CD | TC | TS | PO | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f < 0.001 | f < 0.01 | f < 0.05 | f < 0.001 | f < 0.01 | f < 0.05 | f < 0.001 | f < 0.01 | f < 0.05 | f < 0.001 | f < 0.01 | f < 0.05 | |

| PROPHET | 59.32 | 53.28 | 49.49 | 72.27 | 71.81 | 64.6 | 71.04 | 67.39 | 54.35 | 47.8 | 45.24 | 40.49 |

| GRU-D | 64.52 | 61.3 | 57.08 | 70.72 | 66.18 | 59.35 | 74.25 | 70.19 | 64.59 | 60.32 | 58.13 | 52.28 |

| VAE-RNN | 61.62 | 58.46 | 53.29 | 71.38 | 67.16 | 63.47 | 74.64 | 73.41 | 63.28 | 56.31 | 53.86 | 49.70 |

| ODE-RNN-ODE | 77.66 | 81.15 | 65.77 | 87.95 | 83.71 | 78.64 | 79.24 | 84.17 | 79.82 | 83.36 | 80.39 | 72.12 |

| Informer | 80.42 | 84.9 | 74.54 | 83.39 | 85.35 | 82.01 | 91.09 | 84.49 | 79.23 | 87.66 | 82.94 | 78.56 |

| Autoformer | 85.45 | 87.18 | 82.25 | 80.32 | 80.59 | 82.86 | 83.36 | 84.20 | 79.26 | 81.33 | 86.10 | 80.28 |

| ETDTN | 92.01 | 87.99 | 83.13 | 96.2 | 89.32 | 87.18 | 92.35 | 88.24 | 87.99 | 89.27 | 86.27 | 85.98 |

| c | CD | TC | TS | PO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAR- | 53.52 | 44.03 | 32.12 | 35.72 |

| TW- | 51.15 | 48.21 | 37.72 | 41.85 |

| CVTR- | 74.76 | 71.65 | 72.49 | 76.20 |

| ETDTN | 87.71 | 90.90 | 89.53 | 87.16 |

| The Value of τ | CD | TC | TS | PO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 79.8 | 78.3 | 78.1 | 75.2 |

| 0.25 | 82.2 | 79.4 | 78.3 | 76.6 |

| 0.5 | 82.9 | 80.2 | 79.2 | 77.2 |

| 0.75 | 83.2 | 81.5 | 80.0 | 78.8 |

| 1 | 82.0 | 79.2 | 78.5 | 77.4 |

| 1.25 | 81.3 | 78.7 | 76.4 | 76.3 |

| Method | Avg. Time per Round (s) | Uplink + Downlink Payload (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| FedAvg | 0.42 | 5.2 |

| FedProx | 0.47 | 5.4 |

| ETDTN | 0.63 | 6.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Ye, G.; Zhao, X. Edge Temporal Digital Twin Network for Sensor-Driven Fault Detection in Nuclear Power Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 7510. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247510

Liu S, Ye G, Zhao X. Edge Temporal Digital Twin Network for Sensor-Driven Fault Detection in Nuclear Power Systems. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7510. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247510

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shiqiao, Gang Ye, and Xinwen Zhao. 2025. "Edge Temporal Digital Twin Network for Sensor-Driven Fault Detection in Nuclear Power Systems" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7510. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247510

APA StyleLiu, S., Ye, G., & Zhao, X. (2025). Edge Temporal Digital Twin Network for Sensor-Driven Fault Detection in Nuclear Power Systems. Sensors, 25(24), 7510. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247510