Recent Progress in Structural Integrity Evaluation of Microelectronic Packaging Using Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM): A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

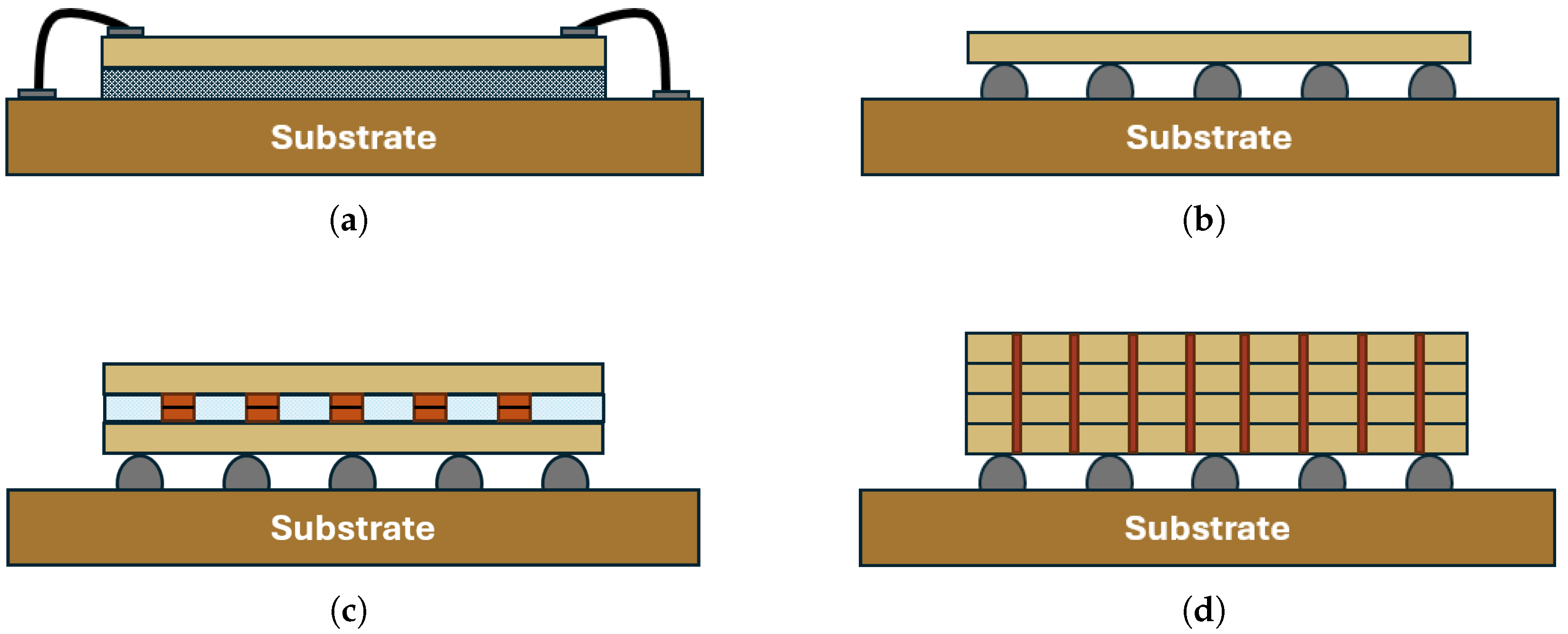

2. Microelectronic Packaging and Inspection

2.1. Packaging and Defect Formation

- Provide structural support for the chip;

- Protect the chip from environmental effects;

- Facilitate effective heat dissipation produced by the chips;

- Enable electrical connectivity for power and signal transfer.

2.1.1. Environmental Protection

2.1.2. Mechanical Protection and Thermal Management

- Eutectic bonding;

- Soldering;

- Epoxy;

- Resins;

- Sintering (Ag, Cu).

2.1.3. Electrical Connection

- Chip-level interconnections: These reside within the back-end-of-line (BEOL) of the silicon die and serve as microscopic wiring networks distributing power and signals among transistors and circuit blocks. They consist of alternating metal and dielectric layers (typically Cu or AlCu with SiO2 or low-k dielectrics) and terminate at the topmost redistribution layers that interface with the first-level interconnects.

- First-level interconnections: Often referred to as package-level interconnections, these connect the active dies to a package substrate or interposer. Common implementations include wire bonding (WB), flip-chip solder bumps, and hybrid Cu-to-Cu bonding. Certain vertical interconnects, such as through-silicon vias (TSVs), may also fall within this category when fabricated in passive interposers, though in stacked-die architectures, TSVs can instead function as chip-level pathways linking multiple active dies.

- Second-level interconnections: Sometimes referred to as board-level connections, these bridge the package substrate to the printed circuit board (PCB) through solder balls, pins, or other surface-mount contacts. They enable communication and power delivery between packaged devices and the larger electronic system.

2.2. NDE Methods for Microelectronic Packaging

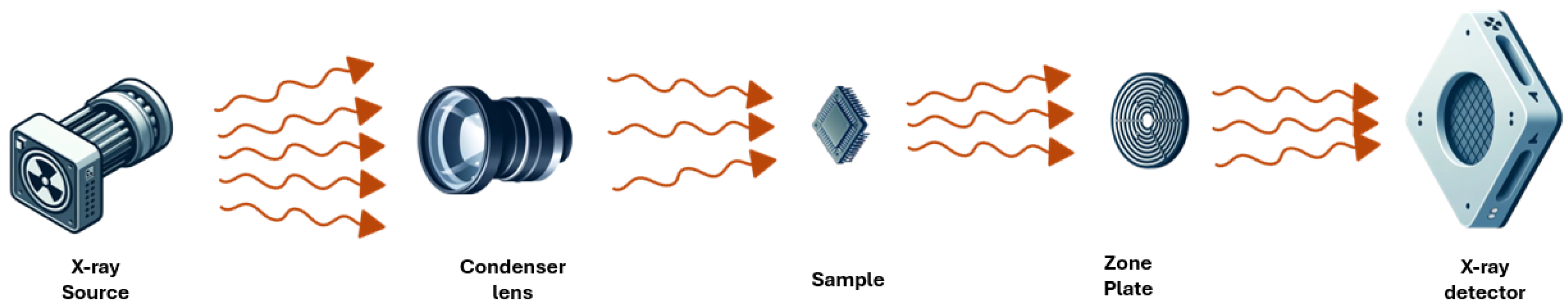

2.2.1. Radiography

2.2.2. Infrared Thermography (IRT)

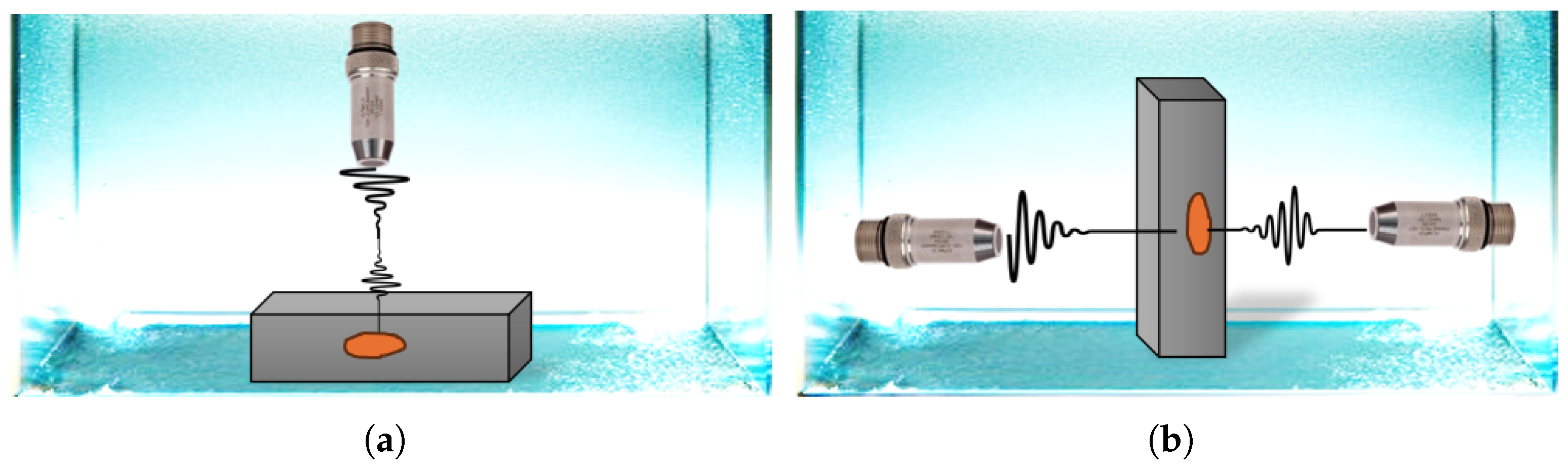

2.2.3. Low Frequency Ultrasonic Testing (UT)

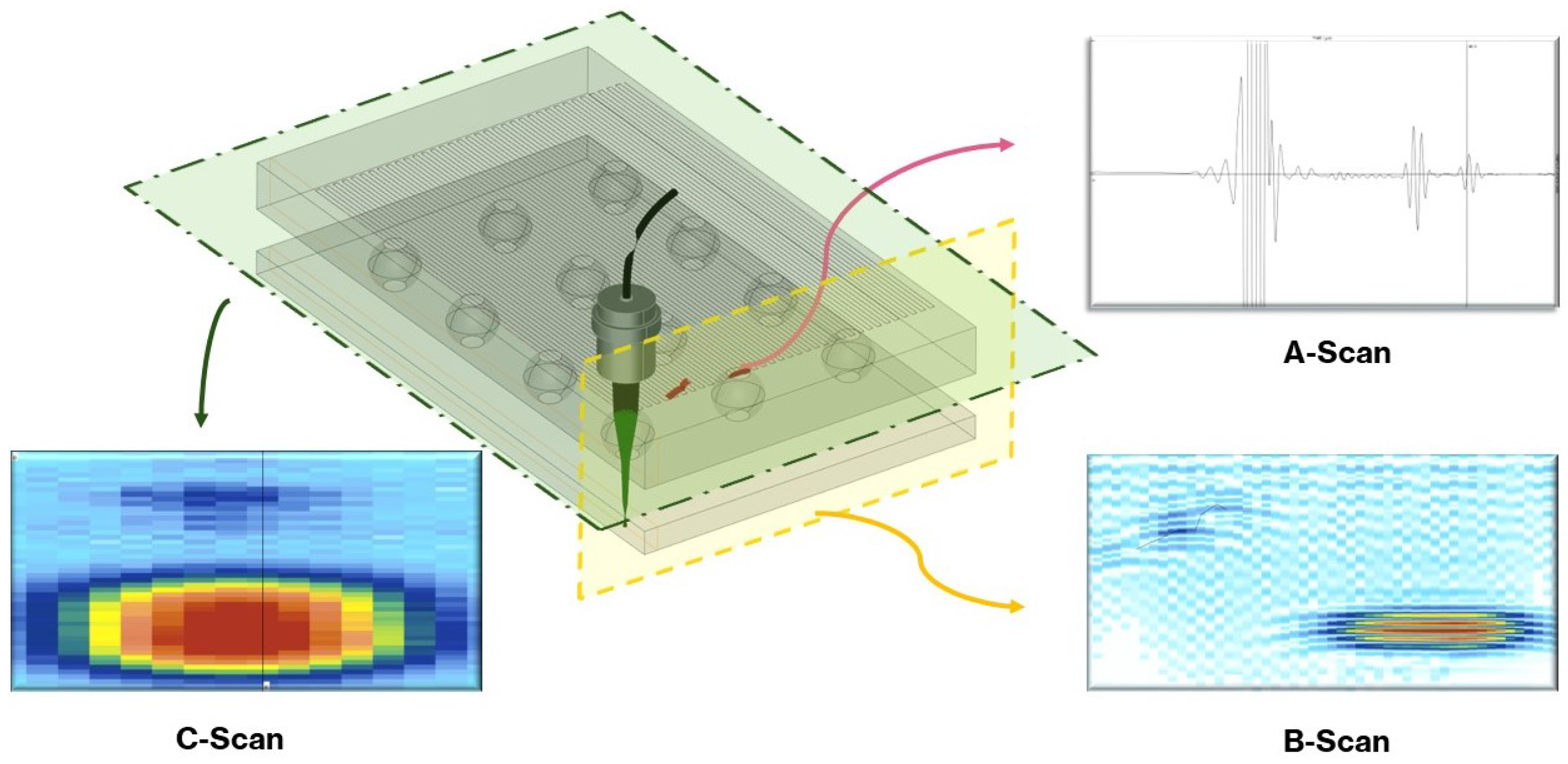

3. SAM Principle

4. Integrity Assessment Using SAM

- (i)

- Die-attach and sintered interfaces;

- (ii)

- Bump/underfill solder interconnects;

- (iii)

- Wire-bond interconnections and mold/leadframe interfaces;

- (iv)

- TSVs and interposers;

- (v)

- Cu–Cu (direct or hybrid) bonds.

4.1. Defect Identification

4.1.1. Die-Attach and Sintered Interfaces

4.1.2. Bump/Underfill Solder Interconnects (Flip-Chip and Wafer-Level)

4.1.3. Wire-Bond Interconnections and Mold/Leadframe Interfaces

4.1.4. TSVs and Interposers

4.1.5. Cu–Cu Bonding (Direct and Hybrid)

4.2. Resolution Enhancement

4.3. Artificial Intelligence for Damage Detection

5. Future Works

- Hardware Upgrade: Increasing the center frequency of transducers inherently reduces penetration depth, yet this approach remains essential given the continual miniaturization of modern microelectronic components. To alleviate this trade-off, the introduction of advanced excitation schemes, such as chirp waveforms, narrow-band pulses, or tone bursts with adjustable cycles, could enhance defect detectability and extend the sensitivity range of SAM. Implementing such waveform variations will necessitate corresponding upgrades in the signal generation, transducer design, and receiver electronics of SAM systems. These improvements could also facilitate compatibility with coded-excitation and pulse-compression techniques, paving the way for higher signal-to-noise ratios without compromising imaging depth.

- Signal and Data Processing: Future research should emphasize data-processing strategies that go beyond enhancing image contrast to directly improving defect detectability. Advanced beamforming and aperture-focusing algorithms could help reduce the number of scans required for layer-by-layer evaluation, thereby accelerating inspections while mitigating issues associated with overlapping signals. Moreover, physics-informed modeling and simulation frameworks can be leveraged to generate high-fidelity synthetic data for algorithm training, addressing data scarcity in experimental measurements. The accuracy of such models will be critical for ensuring that simulation-based analyses faithfully capture the acoustic behavior of multilayer microelectronic structures. Finally, scalable processing pipelines should be developed to minimize computational overhead while maintaining quantitative accuracy.

- Robotics and Automation: The integration of cutting-edge robotic platforms can substantially enhance the speed, precision, and reliability of SAM-based inspections. Autonomous and collaborative robots are increasingly deployed in semiconductor fabs to handle complex, high-throughput tasks within cleanroom environments. Extending this capability to NDE/T, particularly SAM, offers clear potential for automating sample handling, probe positioning, inference, and RoI extraction, reducing manual intervention and improving measurement consistency. Two practical considerations motivate this direction: (i) GHz-SAM systems operate with extremely short working distances; so, manual adjustments of the water path or focal plane carry a nontrivial risk of collision, potentially damaging either the transducer or the sample; and (ii) even slight angling introduced during sample mounting (e.g., trays screwed into the tank base) or during transducer positioning can deviate from perpendicular incidence, strengthening unintended ultrasonic modes and exacerbating multimode interpretation at high frequencies. Robotic assistance that maintains precise standoff and alignment, with closed-loop feedback, can mitigate these risks while enabling repeatable, high-quality inspections.

- Digital Twin and NDT 4.0: When thinking about additional advancements for the SAM technology, the use of Digital Twins and the NDT 4.0 should be considered. Regarding SAM and NDE 4.0, the continuous alignment of virtual process models with actual inspection data would empower predictive maintenance, remote monitoring, and closed-loop optimization of inspection parameters. SAM in a digital-twin ecosystem enables real-time decision-making and provides traceable inspection records, which facilitate accountable design, fabrication, and reliability feedback loops for advanced microelectronic packaging.

- Workforce Development: The microelectronics manufacturing industry is facing a significant workforce shortage. For instance, in the U.S., this shortage is projected to exceed 27,000 by 2030, including 5300 PhDs, 12,300 Master’s, and 9900 bachelor’s degree holders [158]. Addressing this shortage requires sustained effort and innovative approaches to education and training.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D-IC | Three-Dimensional Integrated Circuit |

| Ag | Silver |

| Au | Gold |

| BCIT | Barker Code Infrared Thermography |

| BGA | Ball Grid Array |

| BP | Back Propagation |

| CMP | Chemical Mechanical Polishing |

| Cu | Copper |

| DBA | Direct Bonded Aluminium |

| DBC | Direct Bonded Copper |

| DBSCAN | Density-based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| DIC | Digital Image Correlation |

| ECPT | Eddy Current Pulse Thermography |

| EM | Electromigration |

| FC | Flip-Chip |

| FCM | Fuzzy C-means clustering |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradient |

| I/O | Input/Output |

| IC | Integrated Circuit |

| IMC | Intermetallic Compounds |

| IRT | Infrared Thermography |

| LFMTWI | Linear Frequency Modulation ThermalWave Imaging |

| LIT | Lock-in Infrared Thermography |

| LM-BP | Levenberg-Marquardt Back Propagation |

| LUT | Laser Ultrasonic |

| NDE/T | Nondestructive Evaluation/Testing |

| NDT | Nondestructive Test |

| RoI | Region of Interest |

| SAM | Scanning Acoustic Microscope |

| SiP | ystem-in-Pakcage |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| TAB | Tape Automated Bonding |

| ToF | Time-of-Flight |

| TSV | Through Silicon Vias |

| UBM | Under Bump Metallization |

| UT | Ultrasonic Test |

| VDSR | Very Deep Super Resolution |

| WB | Wire Bonding |

| XCT | X-ray Computed Tomography |

| XRM | X-ray Microscopy |

References

- Tong, H.M. Microelectronics packaging: Present and future. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1995, 40, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, H.K. Advanced Wire Bonding Technology: Materials, Methods, and Testing. In Materials for Advanced Packaging; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 113–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Goyal, D. Introduction to 3D Microelectronic Packaging; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, F. A data-driven method for enhancing the image-based automatic inspection of IC wire bonding defects. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 4779–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendiuch, I. Development in electronic packaging—Moving to 3D system configuration. Radioengineering 2011, 20, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Burkacky, O.; Dragon, J.; Lehmann, N. The Semiconductor Decade: A Trillion-Dollar Industry; Technical Report; McKinsey Global Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, M. Manufacturing processes for fabrication of flip-chip micro-bumps used in microelectronic packaging: An overview. J. Micromanuf. 2020, 3, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.E. Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. 50 years of Moore’s law. In Solid State Technology; PennWell Pub. Co.: Northbrook, IL, USA, 2015; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Beica, R.; Ivankovic, A.; Buisson, T.; Kumar, S.; Azemar, J. The Growth of Advanced Packaging: An Overview of the Latest Technology Developments, Applications and Market Trends. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Microelectronics, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–29 October 2015; pp. 000001–000005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Chen, K.S. Testing process quality of wire bonding with multiple gold wires from viewpoint of producers. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 5400–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, P.; Schmidt, R.; Vetter, A.; Hepp, J.; Karl, A.; Brabec, C.J. Non-destructive imaging of defects in Ag-sinter die attach layers—A comparative study including X-ray, Scanning Acoustic Microscopy and Thermography. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 88–90, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Shi, T.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Du, L.; Liao, G. Nondestructive diagnosis of flip chips based on vibration analysis using PCA-RBF. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 85, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torok, J.; Canfield, S.; Khambati, S.; Mullady, R.; Notohardjono, B.; Zhang, J. I/O Printed Circuit Board Assemblies; Recent Learning in Mechanical Stress Analysis, Verification Testing, and Post-test Analysis Techniques and Results. Int. Symp. Microelectron. 2015, 2015, 000169–000178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, G.; Li, B. Reliability study of package-on-package stacking assembly under vibration loading. Microelectron. Reliab. 2017, 78, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Kim, J.; Cinar, Y.; Kim, W.; Lee, B.; Jang, M.; Song, N.; Lee, S.; Park, J. FEA-based Layout Optimization of E1.S Solid-State Drive to Improve Thermal Cycling Reliability. In Proceedings of the 2023 24th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE), Graz, Austria, 16–19 April 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souare, P.M.; Bouchard, C.; Duchesne, E.; Zaccardi, J.; Pettit, D.; Vachon, F. Applied Modeling Framework in Integrated Circuit Design and Reliability. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 72nd Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 31 May–3 June 2022; pp. 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarvar, F.; Patel, S.; Vlasea, M.; Amini, H.; Varvani-Farahani, A. Nondestructive Characterization of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Components Using High-Frequency Phased Array Ultrasonic Testing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 6766–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryan, P.; Sampath, S.; Sohn, H. An overview of non-destructive testing methods for integrated circuit packaging inspection. Sensors 2018, 18, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yu, X.; Li, K.; Pecht, M. Defect inspection of flip chip solder joints based on non-destructive methods: A review. Microelectron. Reliab. 2020, 110, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Dong, M.; Liu, D. Research Status and Progress on Non-Destructive Testing Methods for Defect Inspection of Micro-Electronic Packaging. J. Electron. Packag. 2024, 146, 030801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, N.; Ghosh, S.; Craig, P.; Kottur, R.; Dalir, H.; Asadizanjani, N. Challenges and opportunities in non-destructive characterization of stacked ic packaging: Insights from sam and 3d x-ray analysis. Dev. X-Ray Tomogr. XV 2024, 13152, 1315225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaka, R.; Mendizabal, L.; Henry, D. Review on Joint Shear Strength of Nano-Silver Paste and Its Long-Term High Temperature Reliability. J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43, 2459–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Tan, K.; Shi, X.; Wang, Z. Microstructure and intermetallic growth effects on shear and fatigue strength of solder joints subjected to thermal cycling aging. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 307, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.; Pang, J.H. Characterization of IMC layer and its effect on thermomechanical fatigue life of Sn–3.8Ag–0.7Cu solder joints. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 541, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuruzi, A.S.; Lahiri, S.K.; Burman, P.; Siow, K.S. Correlation between intermetallic thickness and roughness during solder reflow. J. Electron. Mater. 2001, 30, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, K.S.; Lin, Y.T. Identifying the Development State of Sintered Silver (Ag) as a Bonding Material in the Microelectronic Packaging Via a Patent Landscape Study. J. Electron. Packag. 2016, 138, 020804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, K.S. Are Sintered Silver Joints Ready for Use as Interconnect Material in Microelectronic Packaging? J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Albright, C.E. The influence of atmospheric contamination in copper to copper ultrasonic welding. In Proceedings of the 34th Electronic Components Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 14–16 May 1984; pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, L.M.; Eichelberger, C.W.; Wojnarowski, R.J.; Carlson, R.O. High density interconnects using laser lithography. In Proceedings of the International Society for Hybrid Microelectronics Proceedings, Sobieszewo, Poland, 14–17 September 1988; pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Demmin, J.C. Ultrasonic Bonding Tools for Fine Pitch, High Reliability Interconnect. Multichip Modul. 1996, 2794, 397. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.; Berg, H.M. Micro-corrosion of Al-Cu bonding pads. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Reliability Physics Symposium, Orlando, FL, USA, 25–29 March 1985; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Totta, P.A.; Khadpe, S.; Koopman, N.G.; Reiley, T.C.; Sheaffer, M.J. Chip-to-package interconnections. In Microelectronics Packaging Handbook: Semiconductor Packaging; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 129–283. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, W. Integrated Circuit Packaging, Assembly and Interconnections; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Su, C.; Li, C.; Chang, A.; An, B. Research Progress on Bonding Wire for Microelectronic Packaging. Micromachines 2023, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Du, H. Computational simulation of voids formation and evolution in Kirkendall effect. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 554, 124285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Ramelow, M.; Schmitz, S.; Schuch, B.; Grubl, W. Kirkendall voiding in au ball bond interconnects on al chip metallization in the temperature range from 100–200 C after optimized intermetallic coverage. In Proceedings of the 2009 European Microelectronics and Packaging Conference, Rimini, Italy, 15–18 June 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Gao, L.Y.; Yu, D.; Liu, Z.Q. Comparison and mechanism of electromigration reliability between Cu wire and Au wire bonding in molding state. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 2967–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, W.J. Flip chip—The bumping processes. In Integrated Circuit Packaging, Assembly and Interconnections; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J.; Sanchez, J.; Moyer, R.; Bachman, M.; Stepniak, D.; Elenius, P. Direct bump-on-copper process for flip chip technologies. In Proceedings of the 52nd Electronic Components and Technology Conference 2002 (Cat. No. 02CH37345), San Diego, CA, USA, 28–31 May 2002; pp. 704–710. [Google Scholar]

- Shohji, I.; Fujiwara, S.; Kiyono, S.; Kobayashi, K.F. Intermetallic compound layer formation between Au and In-48Sn solder. Scr. Mater. 1999, 40, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, Y.; Nishimura, H.; Sakane, M.; Ohnami, M. Fatigue life analysis of solder joints in flip chip bonding. J. Electron. Packag. 2000, 122, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohji, I.; Mori, H.; Orii, Y. Solder joint reliability evaluation of chip scale package using a modified Coffin–Manson equation. Microelectron. Reliab. 2004, 44, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, T.T.; Kivilahti, J.K. The role of recrystallization in the failure of SnAgCu solder interconnections under thermomechanical loading. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Technol. 2010, 33, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Basaran, C.; Hopkins, D. Thermomigration in Pb–Sn solder joints under joule heating during electric current stressing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 1045–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chen, C.; Tu, K.N. Failure induced by thermomigration of interstitial Cu in Pb-free flip chip solder joints. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 122103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Theil, J.; Fountain, G.; Workman, T.; Guevara, G.; Uzoh, C.; Suwito, D.; Lee, B.; Bang, K.M.; Katkar, R. Die to wafer hybrid bonding: Multi-die stacking with TSV integration. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Wafer Level Packaging Conference (IWLPC), San Jose, CA, USA, 13–30 October 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, S.; Jourdon, J.; Lhostis, S.; Bouchu, D.; Ayoub, B.; Arnaud, L.; Frémont, H. Review—Hybrid Bonding-Based Interconnects: A Status on the Last Robustness and Reliability Achievements. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherbini, A.; Liff, S.; Swan, J.; Jun, K.; Tiagaraj, S.; Pasdast, G. Hybrid Bonding Interconnect for Advanced Heterogeneously Integrated Processors. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 71st Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 1 June–4 July 2021; pp. 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, C.K.; Chen, K.N. A Review on Hybrid Bonding Interconnection and Its Characterization. IEEE Nanotechnol. Mag. 2024, 18, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favata, J.; Shahbazmohamadi, S. Realistic non-destructive testing of integrated circuit bond wiring using 3-D X-ray tomography, reverse engineering, and finite element analysis. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 83, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, K.; Vaga, R. Recent Advances in X-ray for Semicon Applications. Int. Symp. Microelectron. 2019, 2019, 000573–000583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.A.; Li, J.; Han, L.; Zhong, J. Interface features of ultrasonic flip chip bonding and reflow soldering in microelectronic packaging. Surf. Interface Anal. 2007, 39, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, J.W.; Li, Y.; Barth, H.D.; Parkinson, D.Y.; Pacheco, M.; Goyal, D. Synchrotron Radiation Microtomography for Large Area 3D Imaging of Multilevel Microelectronic Packages. J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43, 4421–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, K.; Estrada, R.; Mirkarimi, L.; Katkar, R.; Buckminster, D.; Huynh, M. Applications of 3D X-Ray Microscopy for Advanced Package Development. Int. Symp. Microelectron. 2011, 2011, 001078–001083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pacheco, M.; Goyal, D.; Elmer, J.W.; Barth, H.D.; Parkinson, D. High resolution and fast throughput-time X-ray computed tomography for semiconductor packaging applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 64th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Orlando, FL, USA, 27–30 May 2014; pp. 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, L.C. Investigation of the solder void defect in IC semiconductor packaging by 3D computed tomography analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference (EPTC), Singapore, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shie, K.C.; Lin, T.W.; Tu, K.; Chen, C. Non-destructive Observation of Void Formation Due to Electromigration in Solder Microbump by 3D xray. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 71st Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 1 June–4 July 2021; pp. 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guin, U.; DiMase, D.; Tehranipoor, M. Counterfeit Integrated Circuits: Detection, Avoidance, and the Challenges Ahead. J. Electron. Test. 2014, 30, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muß, D.; Koch, R. Bonding wire characterization using non-destructive X-ray imaging. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 148, 115177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, Y.; Johnson, B.; Estrada, R.; Hunter, L.; Fahey, K.; Chou, T.; Kuo, Y.L. 3D X-Ray microscopy: A non destructive high resolution imaging technology that replaces physical cross-sectioning for 3DIC packaging. In Proceedings of the ASMC 2013 SEMI Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA, 14–16 May 2013; pp. 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C. 3-D X-Ray Imaging With Nanometer Resolution for Advanced Semiconductor Packaging FA. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 8, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Krampert, G.; Candell, S.; Terada, M.; Rodgers, T. A Breakthrough in Resolution and Scan Speed: Overcome the Challenges of 3D X-ray Imaging Workflows for Electronics Package Failure Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on the Physical and Failure Analysis of Integrated Circuits (IPFA), Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Zulkifli, S.; Zee, B.; Thomas, G.; Gu, A.; Yang, Y.; Masako, T.; Lee, W. High-resolution 3D X-ray Microscopy for Structural Inspection and Measurement of Semiconductor Package Interconnects. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Physical and Failure Analysis of Integrated Circuits (IPFA), Hangzhou, China, 2–5 July 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Shen, H.; Asadizanjani, N.; Tehranipoor, M.; Forte, D. Impact of X-Ray Tomography on the Reliability of Integrated Circuits. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2017, 17, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaby, H.J. Total-Ionizing-Dose Effects in Modern CMOS Technologies. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2006, 53, 3103–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wei, L.; Shao, M.; Lu, X. Detection of micro solder balls using active thermography and probabilistic neural network. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2017, 81, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, T.; Lu, X.; Liao, G. Using active thermography for defects inspection of flip chip. Microelectron. Reliab. 2014, 54, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; He, Z.; Su, L.; Fan, M.; Liu, F.; Liao, G.; Shi, T. Detection of Micro Solder Balls Using Active Thermography Technology and K-Means Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 5620–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargulski, D.R.; May, D.; Loffler, F.; Nowak, T.; Petrick, J.; Grosse, C.; Wunderle, B.; Boschman, E.; Ras, M.A. An In-line Failure Analysis System Based on IR Thermography Ready for Production Line Integration. In Proceedings of the 2019 25th International Workshop on Thermal Investigations of ICs and Systems (THERMINIC), Lecco, Italy, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahandeh, S.; May, D.; Wargulski, D.; Boschman, E.; Schacht, R.; Ras, M.A.; Wunderle, B. Infrared thermal imaging as inline quality assessment tool. In Proceedings of the 2021 22nd International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE), St. Julian, Malta, 19–21 April 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xue, Y.; Tian, G.; Liu, Z. Thermal Analysis of Solder Joint Based on Eddy Current Pulsed Thermography. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 7, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, X.; He, M. Intelligent Pseudo Solder Detection in PCB Using Laser-Pulsed Thermography and Neural Network. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Schindler, S.; Wolter, K.J.; Wiese, S.; Panchenko, I. Determination of melting and solidification temperatures of Sn-Ag-Cu solder spheres by infrared thermography. Thermochim. Acta 2022, 714, 179245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gao, Y.; Xiong, C.; Lei, X.; Lv, W.; Zhu, F. A full-field warpage characterization measurement method coupled with infrared information. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 149, 115237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.K.; Chandramohan, A.; Weibel, J.A.; Garimella, S.V. Simultaneous Measurement of Temperature and Strain in Electronic Packages Using Multiframe Super-Resolution Infrared Thermography and Digital Image Correlation. J. Electron. Packag. 2022, 144, 041019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, X.; Cao, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Research on life evaluation method of solder joint based on eddy current pulse thermography. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2019, 90, 084901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenstein, O.; Warta, W.; Schubert, M. Lock-in Thermography: Basics and Use for Evaluating Electronic Devices and Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Panahandeh, S.; May, D.; Grosse-Kockert, C.; Wunderle, B.; Ras, M.A. Failure Analysis of Sintered Layers in Power Modules Using Laser Lock-in Thermography. In Proceedings of the 2023 24th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE), Graz, Austria, 16–19 April 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Koegel, M.; Grosse, C.; Altmann, F.; Devarajulu, H.T.; Benito, F.M.; Goyal, D.; Pacheco, M. Localization enhancement in quantitative thermal lock-in analysis using spatial phase evaluation. Microelectron. Reliab. 2025, 168, 115690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, C.; Li, R.; Liu, T.; Shen, R.; Wang, J.; Tang, Q. Micro-crack defects detection of semiconductor Si-wafers based on Barker code laser infrared thermography. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 123, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lee, H.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Kumar Neerukatti, R.; Liu, K.C. Detection of Sealant Delamination in Integrated Circuit Package Using Nondestructive Evaluation. J. Electron. Packag. 2021, 143, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Koo, B.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Neerukatti, R.K.; Liu, K.C. Damage detection technique using ultrasonic guided waves and outlier detection: Application to interface delamination diagnosis of integrated circuit package. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 160, 107884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.V.B.; Ume, I.C.; Williamson, J.; Sitaraman, S.K. Evaluation of the Quality of BGA Solder Balls in FCBGA Packages Subjected to Thermal Cycling Reliability Test Using Laser Ultrasonic Inspection Technique. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.V.B.; Gupta, S.; Williamson, J.; Sitaraman, S.K. Correlation Studies Between Laser Ultrasonic Inspection Data and Finite-Element Modeling Results in Evaluation of Solder Joint Quality in Microelectronic Packages. J. Electron. Packag. 2022, 144, 011009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.V.B.; Williamson, J.; Sitaraman, S.K. Measurement Capability of Laser Ultrasonic Inspection System for Evaluation of Ball-Grid Array Package Solder Balls. J. Microelectron. Electron. Packag. 2021, 18, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.V.B.; Ume, I.C.; Mebane, A.; Akinade, K.; Rogers, B.; Guirguis, C.; Patel, P.B.; Derksen, K.; Case, R. Evaluation of FCBGA Package Subjected to Four-Point Bend Reliability Test Using Fiber Array Laser Ultrasonic Inspection System. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.V.; Ume, I.C.; Williamson, J.; Nguyen, L. Non-destructive Failure Analysis of Various Chip to Package Interaction Anomalies in FCBGA Packages Subjected to Temperature Cycle Reliability Testing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 69th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28–31 May 2019; pp. 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebane, A.M.; Reddy, V.V.B.; Ume, I.C.; Akinade, K. Feasibility Studies and Advantages of Using Dual Fiber Array in Laser Ultrasonic Inspection of Electronic Chip Packages. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehendale, M.; Mair, R.; Kotelyanskii, M.; Murray, T.; Dove, J.; Ru, X.; Cohen, J.D.; Mukundhan, P.; Kryman, T.J. Non-destructive acoustic metrology for void detection in TSV. In Proceedings of the International Wafer Level Packaging Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 11–13 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, R.; Kotelyanskii, M.; Mehendale, M.; Ru, X.; Mukundhan, P.; Kryman, T.; Liebens, M.; Van Huylenbroeck, S.; Haensel, L.; Miller, A.; et al. Non-destructive acoustic metrology and void detection in 3 × 50 μm TSV. In Proceedings of the 2016 27th Annual SEMI Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference (ASMC), Saratoga Springs, NY, USA, 16–19 May 2016; pp. 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Czurratis, P.; Hoffrogge, P.; Petzold, M. Automated inspection and classification of flip-chip-contacts using scanning acoustic microscopy. Microelectron. Reliab. 2010, 50, 1469–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Varshney, N.; Roy, A.; Woychik, C.; Dalir, H.; Asadizanjani, N. Motivating automated multimodal failure analysis for heterogeneously integrated devices. Dev. X-Ray Tomogr. XV 2024, 13152, 1315228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Roy, A.; Al Hasan, M.M.; Craig, P.; Varshney, N.; Koppal, S.J.; Asadizanjani, N. Demystifying Edge Cases in Advanced IC Packaging Inspection through Novel Explainable AI Metrics. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 74th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Denver, CO, USA, 28–31 May 2024; pp. 2286–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Bottge, B.; Kogel, M.; Naumann, F.; Zijl, J.; Kersjes, S.; Behrens, T.; Altmann, F. Non-destructive Assessment of the Porosity in Silver (Ag) Sinter Joints Using Acoustic Waves. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 68th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 May–1 June 2018; pp. 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutt, D.; Webb, D.; Hung, K.; Tang, C.; Conway, P.; Whalley, D.; Chan, Y. Scanning acoustic microscopy investigation of engineered flip-chip delamination. In Proceedings of the Twenty Sixth IEEE/CPMT International Electronics Manufacturing Technology Symposium (Cat. No. 00CH37146), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 3 October 2000; pp. 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdan Mehr, M.; Bahrami, A.; Fischer, H.; Gielen, S.; Corbeij, R.; van Driel, W.; Zhang, G. An overview of scanning acoustic microscope, a reliable method for non-destructive failure analysis of microelectronic components. In Proceedings of the 2015 16th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems, Budapest, Hungary, 19–22 April 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Cai, X.; Huang, W.; Cheng, Z. Research of Underfill Delamination in Flip Chip by the J-Integral Method. J. Electron. Packag. 2004, 126, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Zhang, G.M.; Harvey, D.M.; Qi, A. Characterization of micro-crack propagation through analysis of edge effect in acoustic microimaging of microelectronic packages. NDT E Int. 2016, 79, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, A.; Keswani, M. Integrated circuit packaging review with an emphasis on 3D packaging. Integration 2018, 60, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Liao, G.; Zha, Z.; Xia, Q.; Shi, T. A novel approach for flip chip solder joint inspection based on pulsed phase thermography. NDT&E Int. 2011, 44, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderle, B.; Michel, B. Progress in reliability research in the micro and nano region. Microelectron. Reliab. 2006, 46, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Kiong, S.; Yung, L.C. Assessment Methodology on Mold Void Defect by Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM) Non-Destructive Technique. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 38th International Electronics Manufacturing Technology Conference (IEMT), Melaka, Malaysia, 4–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.M.; Lai, K.K.; Chen, K.S.; Chang, T.C. Process-Quality Evaluation for Wire Bonding With Multiple Gold Wires. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106075–106082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, G.; Rusev, R.; Nikolov, D.; Rusev, R. Identifying of Delamination in Integrated Circuits using Surface Acoustic Microscopy. In Proceedings of the 2021 30th International Scientific Conference Electronics (ET 2021), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 15–17 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario, P.; Josef, M.; Michael, I. Inverted high frequency Scanning Acoustic Microscopy inspection of power semiconductor devices. Microelectron. Reliab. 2012, 52, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lee, S.W.; Wu, H.; Zhang, R. Nondestructive inspection of through silicon via depth using scanning acoustic microscopy. In Proceedings of the International Microsystems Packaging Assembly and Circuits Technology Conference, IMPACT 2010 and International 3D IC Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–22 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, E.; Rosc, J.; Hammer, R.; Czurratis, P.; Koch, M.; Kraft, J.; Schrank, F.; Brunner, R. Automatized failure analysis of tungsten coated TSVs via scanning acoustic microscopy. Microelectron. Reliab. 2016, 64, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Kang, D.; Kim, J.N.; Park, I.K. Through-Silicon via Device Non-Destructive Defect Evaluation Using Ultra-High-Resolution Acoustic Microscopy System. Materials 2023, 16, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossut, S.; Devos, A.; Lhostis, S.; Deloffre, E.; Euvrard, C.; Dettoni, F.; Chaton, C. Scanning Acoustic Microscopy versus Colored Picosecond Acoustics to detect interface defects in hybrid wafer bonding. In Proceedings of the Forum Acusticum, Lyon, France, 7–11 December 2020; pp. 2553–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.; Mirkarimi, L.; Fountain, G.; Wang, L.; Uzoh, C.; Workman, T.; Guevara, G.; Mandalapu, C.; Lee, B.; Katkar, R. Scaling package interconnects below 20 μm pitch with hybrid bonding. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 68th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 May–1 June 2018; pp. 314–322. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Seo, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, S.E. Low-Temperature (260 °C) Solderless Cu–Cu Bonding for Fine-Pitch 3-D Packaging and Heterogeneous Integration. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 11, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Park, H.S.; Kim, S.E. Two-Step Plasma Treatment on Sputtered and Electroplated Cu Surfaces for Cu-To-Cu Bonding Application. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Yu, S.; Roma, M.P.C.; Maganty, S.; Park, S.; Bersch, E.; Kim, C.; Sapp, B. Mechanism of low-temperature copper-to-copper direct bonding for 3D TSV package interconnection. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 63rd Electronic Components and Technology Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28–31 May 2013; pp. 1133–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, T.H.; Kang, T.C.; Mao, S.Y.; Chou, T.C.; Hu, H.W.; Chiu, H.Y.; Shih, C.L.; Chen, K.N. Investigation of wet pretreatment to improve Cu-Cu bonding for hybrid bonding applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 71st Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 1 June–4 July 2021; pp. 700–705. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, S.; Czurratis, P.; Hoffrogge, P.; Temple, D.; Malta, D.; Reed, J.; Petzold, M. Extending acoustic microscopy for comprehensive failure analysis applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2011, 22, 1580–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Lapadatu, A.; Djuric, T.; Czurratis, P.; Schischka, J.; Petzold, M. Scanning acoustic gigahertz microscopy for metrology applications in three-dimensional integration technologies. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2014, 13, 011207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Appenroth, T.; Naumann, F.; Steller, W.; Wolf, M.J.; Czurratis, P.; Altmann, F.; Petzold, M. Acoustic GHz-microscopy and its potential applications in 3D-integration technologies. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 65th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 May 2015; pp. 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Vogg, G.; Petzold, M. Defect analysis using scanning acoustic microscopy for bonded microelectronic components with extended resolution and defect sensitivity. Microsyst. Technol. 2018, 24, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogg, G.; Heidmann, T.; Brand, S. Scanning acoustic GHz-microscopy versus conventional SAM for advanced assessment of ball bond and metal interfaces in microelectronic devices. Microelectron. Reliab. 2015, 55, 1554–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Simon-Najasek, M.; Kögel, M.; Jatzkowski, J.; Portius, R.; Altmann, F. Detection and analysis of stress-induced voiding in Al-power lines by acoustic GHz-microscopy. Microelectron. Reliab. 2016, 64, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, I.; Khaled, A.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.W.; Beyne, E.; Kögel, M.; Brand, S.; Djuric-Rissner, T.; Wiesler, I. Detection of local Cu-to-Cu bonding defects in wafer-to-wafer hybrid bonding using GHz-SAM. In Proceedings of the International Symposium for Testing and Failure Analysis, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 28 October–1 November 2018; Volume 81009, pp. 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.M.; Harvey, D.M.; Braden, D.R. Microelectronic package characterisation using scanning acoustic microscopy. NDT&E Int. 2007, 40, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, K.; Jang, H.; Park, B.; Ha, J.; Park, I.; Kim, K. Wavelet analysis based deconvolution to improve the resolution of scanning acoustic microscope images for the inspection of thin die layer in semiconductor. NDT&E Int. 2002, 35, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrenfeldt, C.; Munk-Nielsen, S.; Bȩczkowski, S. Frequency domain scanning acoustic microscopy for power electronics: Physics-based feature identification and selectivity. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 88–90, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Altmann, F. Lock-In-Thermography, Photoemission, and Time-Resolved GHz Acoustic Microscopy Techniques for Nondestructive Defect Localization in TSV. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 8, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Kögel, M.; Altmann, F.; DeWolf, I.; Khaled, A.; Moore, M.J.; Strohm, E.M.; Kolios, M.C.; Strohm, E.M. Acoustic and photoacoustic inspection of through-silicon vias in the GHz-frequency band. In Proceedings of the International Symposium for Testing and Failure Analysis, Pasadena, CA, USA, 5–9 November 2017; Volume 81504, pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Huang, H.; Xie, W.; Gu, J.; Li, K.; Su, L. Simulation Research on Sparse Reconstruction for Defect Signals of Flip Chip Based on High-Frequency Ultrasound. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tan, S.; Qi, Y.; Gu, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, G.; Ming, X.; Li, K.; Pecht, M. An improved orthogonal matching pursuit method for denoising high-frequency ultrasonic detection signals of flip chips. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 188, 110030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, A.L.; Pound, M.P.; Watson, N.J. A review of ultrasonic sensing and machine learning methods to monitor industrial processes. Ultrasonics 2022, 124, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M. Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, N.; Du, H.; Li, W. Automated defect recognition of C-SAM images in IC packaging using Support Vector Machines. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2005, 25, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel, M.; Brand, S.; Altmann, F. Machine Learning Assisted Signal Analysis in Acoustic Microscopy for Non-Destructive Defect Identification. In Proceedings of the Electronic Device Failure Analysis Society, Portland, OR, USA, 10–14 November 2019; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Shi, T.; Xu, Z.; Lu, X.; Liao, G. Defect inspection of flip chip solder bumps using an ultrasonic transducer. Sensors 2013, 13, 16281–16291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Su, L.; Fan, M.; Yin, J.; He, Z.; Lu, X. Using scanning acoustic microscopy and LM-BP algorithm for defect inspection of micro solder bumps. Microelectron. Reliab. 2017, 79, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zha, Z.; Lu, X.; Shi, T.; Liao, G. Using BP network for ultrasonic inspection of flip chip solder joints. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 34, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Wei, L.; He, Z.; Wei, W.; Lu, X. Defect inspection of solder bumps using the scanning acoustic microscopy and fuzzy SVM algorithm. Microelectron. Reliab. 2016, 65, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.N.; Liu, F.; He, Z.Z.; Li, L.Y.; Hu, N.N.; Su, L. Defect inspection of flip chip package using SAM technology and fuzzy C-means algorithm. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2018, 61, 1426–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Fan, M.; He, Z.; Lu, X. Using RBF algorithm for Scanning Acoustic Microscopy inspection of flip chip. In Proceedings of the 2018 19th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT), Shanghai, China, 8–11 August 2018; pp. 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; He, Z.; Su, L.; Lu, X. Intelligent detection of flip chip with the scanning acoustic microscopy and the general regression neural network. Microelectron. Eng. 2019, 217, 111127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; He, Z.; Gutierrez, H.; Du, J.; Yang, W.; Lu, X. The intelligent detection method for flip chips using CBN-S-Net algorithm with SAM images. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 83, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, W.; Chen, T.; Lu, X.; He, Z. Micro solder bump detection of flip chip using improved decision tree model based on SAM image. J. Instrum. 2022, 17, P10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu Ha Vu, T.; Hung Vo, T.; Nhan Nguyen, T.; Choi, J.; Mondal, S.; Oh, J. Optimizing Scanning Acoustic Tomography Image Segmentation With Segment Anything Model for Semiconductor Devices. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2024, 37, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Koegel, M.; Altmann, F.; Bach, L. Deep Learning assisted quantitative Assessment of the Porosity in Ag-Sinter joints based on non-destructive acoustic inspection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 71st Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 1 June–4 July 2021; pp. 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lu, X.; He, Z.; Shi, T. Using convolutional neural network for intelligent SAM inspection of flip chips. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 115022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Varshney, N.; Roy, A.; Craig, P.; Hasan, M.M.A.; Ghane-Motlagh, R.; Elsayed, N.; Koppal, S.J.; Asadizanjani, N. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for SAM Image Enhancement with a Novel Physics-Constrained Metric for Advanced Semiconductor Packaging Inspection. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 75th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Dallas, TX, USA, 27–30 May 2025; pp. 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiao, M.; Lv, H.; Luo, J.; Wang, X.; Luo, D. Research on Scanning Acoustic Image Defects Detection of Integrated Circuits based on YOLOX. In Proceedings of the 2022 23rd International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT), Dalian, China, 10–13 August 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Kögel, M.; Grosse, C.; Altmann, F.; Hollerith, C.; Gounet, P. Advances in High-Resolution Non-Destructive Defect Localization Based on Machine Learning Enhanced Signal Processing. In Proceedings of the Electronic Device Failure Analysis Society, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–16 November 2023; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.S.; Hoffrogge, P.; Czurratis, P.; Kuehnicke, E.; Wolf, M. Automated Defect Classification In Semiconductor Devices Using Deep Learning Networks. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Physical and Failure Analysis of Integrated Circuits, IPFA, Singapore, 18–21 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; He, Z.; Du, J.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, X. Intelligent detection technology of flip chip based on H-SVM algorithm. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 134, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Lu, J.; Feng, J.; Zhou, J. Deep Localized Metric Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018, 28, 2644–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Shi, J.; Qi, G.; Lei, Z. Prior-knowledge and attention based meta-learning for few-shot learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 213, 106609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y. A Deep Hybrid Few Shot Divide and Glow Method for Ill-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 17767–17778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; He, S.; Chen, J.; Pan, T.; Zhou, Z. Toward Small Sample Challenge in Intelligent Fault Diagnosis: Attention-Weighted Multidepth Feature Fusion Net With Signals Augmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3502413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Peng, Y. Region- and Strength-Controllable GAN for Defect Generation and Segmentation in Industrial Images. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 4531–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; He, Z.; Gutierrez, H.; Du, J.; Yang, W.; Lu, X. Small sample classification based on data enhancement and its application in flip chip defection. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 141, 114887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Doan, V.H.M.; Vo, T.H.; Vu, D.D.; Tran, L.H.; Vu, T.T.H.; Vo, T.T.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Mondal, S.; Choi, J.; et al. Image-enhanced generative model for industrial scanning acoustic super-resolution in non-destructive testing. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 162, 112500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipping Away: Assessing and Addressing the Labor Market Gap Facing the U.S. Semiconductor Industry; Semiconductor Industry Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

| Year | Package Type | Inspection Location/Region | Defect Type | Key Findings | Limitations/Challenges | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Flip-chip | Underfill/chip interface | Delamination | Used 230 MHz transducer to detect controlled delamination before and after thermal cycling in C-scan images | Could not reveal poor adhesion in the absence of air gaps; failed to detect weak bonding without separation | [96] |

| 2004 | Flip-chip | Underfill/chip interface | Delamination | Measured delamination crack length and growth rate under thermal cycling using C-scans of a 230 MHz transducer; correlated with FE J-integral to derive a Paris-type reliability relation | No specific SAM-related limitations reported | [98] |

| 2016 | Flip-chip | Die/solder bump interface | Micro-crack | The B-scan and C-scan pixel-intensities of a 230 MHz transducer used as features for an indirect estimation of crack growth under thermal cycling; validated via simulation and accelerated testing | Quantitative accuracy limited by transducer resolution and edge-effect interference; mainly applicable to cracks near bump periphery | [99] |

| 2018 | Flip-chip | Underfill and interconnect regions | Internal voids, mold voids, delamination | Demonstrated feasibility of 50 MHz transducer C-scan images for mold void detection; SAM indications validated destructively | Verification still required destructive tests | [103] |

| 2010 | 3D IC | TSV depth and wafer interfaces | Depth variation and incomplete etching | A-scans were used to extract time-of-flight to measure TSV depth using a 110 MHz transducer; B-scans identified via depths with <5% error vs cross-section; effective for vias ≥ 30 μm | Accuracy limited for smaller vias (<30 μm) due to diffraction and resolution; higher-frequency transducers recommended | [107] |

| 2013 | 3D IC | Cu-Cu direct bonding interface | Interfacial voids from oxide and stress non-uniformity | Studied surface cleaning effects on Cu–Cu bonding; C-scans were used to localize voids | Frequency unspecified | [114] |

| 2021 | 3D IC | Cu-Cu hybrid bonding interface | Voids; oxidation-induced bonding failures | C-scans used for evaluating wet-acid pretreatments (acetic, citric, sulfuric, hydrochloric) for oxide removal prior to hybrid bonding | Frequency unspecified | [115] |

| 2023 | 3D IC | TSV | Internal voids and seam defects in via holes | Custom ultra-high-resolution 400 MHz SAM detected 20 μm voids at ∼32.5 μm depth (confirmed by FIB-SEM); precise visualization of TSV defects through C-scans and B-scans | Detection limited by scattering at extreme depths; further hardware optimization needed for vias < 20 μm | [109] |

| 2016 | Bonded wafers | TSV and Si substrate | Crack in TSV coating; defect at TSV bottom | Detected damage of ∼50 μm with a 100 MHz transducer; SAM’s C-scans were validated with X-ray; provided EFIT simulation | No specific SAM-related limitations reported | [108] |

| 2018 | Die-to-wafer and die-to-die bonding | Cu–Cu bonding interface | Voids/unbonded regions | CSAM assessed Cu-Cu bond quality; SAM-identified voids confirmed by electrical testing | Frequency unspecified | [111] |

| 2019 | Bonded wafers | Cu-Cu bonding interface | Incomplete Cu diffusion/poor bonding | CSAM (SAT) provided qualitative evaluation of Cu-Cu interface after plasma treatment | Frequency unspecified | [113] |

| 2021 | Bonded wafers | Cu-Cu bonding interface | Unbonded/void regions | CSAM (SAT) localized unbonded regions attributed to SiO2 patterning and etching defects | Frequency unspecified | [112] |

| 2012 | Power semiconductor device (DIP-style) | Die-attach and wire-bond interfaces | Delamination, voids, bond lift-off | Performed inspection of power devices using CSAM (75 and 230 MHz) | Inspections required metallization removal via mechanical grinding and chemical etching | [106] |

| 2018 | Si-die on DCB substrate | Die-attach (Ag-sinter layer) | Porosity (1–5 μm pores) | Correlated 175 MHz SAM B-scans (reflectivity + ToF) with porosity level | Quantitative porosity estimation limited by sinter-layer thickness variation and scattering from other inhomogeneities | [95] |

| 2018 | Si-IGBT on DBC substrate | Die-attach (Ag-sinter joint) | Voids; adhesion defects (interface delamination) | Minimum detectable defect reported as ∼427 μm (circular) or ≥120 μm (line); interface defect >451 μm for a 50 MHz transducer; sensitive to porosity | Requires water coupling; inspection time ∼8 min per substrate; in-line integration limited by immersion setup | [12] |

| Year | Technique | Enhancement Strategy | Key Findings | Limitations/Challenges | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | GHz-SAM | 1 GHz transducer (burst mode) | Achieved ∼3 μm resolution through ∼5 μm polymer; localized delaminations in Cu/Sn micro-bump arrays verified by SEM | Limited penetration depth; requires thinning and surface access | [116] |

| 2014 | GHz-SAM | 1.12 GHz for 3D IC applications; focus and defocus imaging for near-surface defect localization | Demonstrated the superiority of GHz-SAM in inspection of TSVs smaller than 100 μm over a 200 MHz transducer; GHz-SAM lateral resolution was about 1–3 μm; detected voids ∼1.5 μm below the surface; verified acoustic contrast by PFIB and SEM | Limited penetration depth (<10 μm); sensitivity to surface condition | [117] |

| 2015 | GHz-SAM | 1.12 GHz for 3D IC applications | Provided comparative analysis between 400 MHz and 1.12 GHz; demonstrated that 1.12 GHz SAM achieved ∼1–3 μm lateral resolution, enabling detection of voids and rim-delaminations at depths up to ∼40 μm; 400 MHz scans provided lower resolution but deeper penetration; verified structural correspondence with FIB/SEM | Penetration depth limited (<50 μm); interpretation complicated by multimode propagation | [118] |

| 2015 | GHz-SAM | 1 GHz for inspection of molded packages | A Comparative analysis between several MHz range transducers and the GHz transducer is provided; The employed transducers were varied with respect to lens aperture; Adhesion defects and micro-voids in 25 μm Cu ball bonds and 30 μm wire–metal contacts were clearly shown; emphasized on the necessity of GHz-SAM for reliable evaluation of 10 μm | Limited penetration depth at 1 GHz (<10 μm); requires thinning and surface access | [120] |

| 2016 | GHz-SAM | 1 GHz for inspection of AlCu power lines | Stress-induced voids in the power lines were inspected using GHz-SAM; verification of the results was performed with FIB/SEM cross-sections | Limited to near-surface inspection (<10 μm depth); requires thinning and surface access; quantitative depth estimation complicated by varying acoustic velocities. | [121] |

| 2007 | Signal Processing | Sparse signal representation and adaptive dictionary learning | Introduced a signal-processing framework using matching-pursuit and adaptive sparse representations in Gabor dictionaries to decompose ultrasonic A-scans; enabled separation of overlapping echoes; improved time-of-flight accuracy; enhanced lateral and depth resolution beyond conventional 230 MHz SAM performance | Computationally expensive; sensitive to noise model and sample-dependent echo distortions | [123] |

| 2011 | Image Processing | Blind deconvolution; Gaussian and Sobel filters | Enhanced edge definition and contrast in bonded-wafer and interfacial images | Parameter tuning required; processing not standardized across samples; improvement primarily near-surface | [116] |

| 2011 | Signal Processing | Wavelet-based features; backscatter amplitude integral (BAI); parametric/cepstral analysis for echo separation | Improved defect detectability and interpretability in inspection of flip-chip interconnections; Better adhesion contrast compared to C-scans of raw data; Verification performed with SEM and X-ray microscopy | Computationally intensive; method and thresholds must be re-tuned for device regions and stacks; sensitivity to noise/sampling | [116] |

| 2018 | Signal Processing | Frequency-domain transformation | Introduced a frequency-domain SAM framework for multilayered power-module inspection; Fourier analysis of gated A-scans enabled layer-selective contrast and thickness estimation by identifying resonant dips and harmonic interference frequencies linked to internal reflections; demonstrated accurate separation of overlapping echoes | Analysis limited to 25 MHz transducer range | [125] |

| 2018 | GHz-SAM and Signal Processing | 1 GHz transducer and FFT-based computation of power spectral density | Developed time-resolved acoustic gigahertz microscopy (GHz-SAM) combined with spectral-domain analysis of unprocessed RF echo data for inspection of TSVs; power spectral density computed in 5 MHz bands (800–1200 MHz) enabled frequency-selective imaging and improved defect sensitivity; the method successfully detected sub-surface voids (∼3–10 μm) in Cu-filled TSVs; validated with FIB/SEM; demonstrated that spectral decomposition increases sensitivity to weak scattering signals compared to intensity-only SAM. | Limited penetration depth (<10 μm); high-frequency attenuation; Large dataset and computationally expensive | [126] |

| 2020, 2023 | Signal Processing | Sparse signal reconstruction | Introduced sparse-representation denoising using Gabor dictionaries and orthogonal matching pursuit ([128]), later refined with adaptive artificial-bee-colony optimization (AABC-OMP) and wavelet-threshold post-processing ([129]). The approach separates overlapping echoes, enhances SNR, and improves convergence in high-frequency SAM of flip-chip solder joints | Computationally expensive | [128,129] |

| RoI Extraction | Features | Classification Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Correlation | , , , , , , C | BP Network | [136] |

| , Var, Kurt | FCM | [137] | |

| Binary Mask | , Mean, Range, Var, Skew | Fuzzy-SVM | [138] |

| Var, Mean, Skew | Radial Basis Function Neural Network | [139] | |

| Correlation Coefficient | , Mean, Var, Range | General Regression Neural Network | [140] |

| HOG | , Mean, Range | SVM | [141] |

| Threshold Gradient | , , , , , , C | Improved Decision Tree | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meshki Zadeh, P.; Brand, S.; Dehghan-Niri, E. Recent Progress in Structural Integrity Evaluation of Microelectronic Packaging Using Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM): A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247499

Meshki Zadeh P, Brand S, Dehghan-Niri E. Recent Progress in Structural Integrity Evaluation of Microelectronic Packaging Using Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM): A Review. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247499

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeshki Zadeh, Pouria, Sebastian Brand, and Ehsan Dehghan-Niri. 2025. "Recent Progress in Structural Integrity Evaluation of Microelectronic Packaging Using Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM): A Review" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247499

APA StyleMeshki Zadeh, P., Brand, S., & Dehghan-Niri, E. (2025). Recent Progress in Structural Integrity Evaluation of Microelectronic Packaging Using Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM): A Review. Sensors, 25(24), 7499. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247499