Fault Diagnosis Method for Excitation Dry-Type Transformer Based on Multi-Channel Vibration Signal and Visual Feature Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

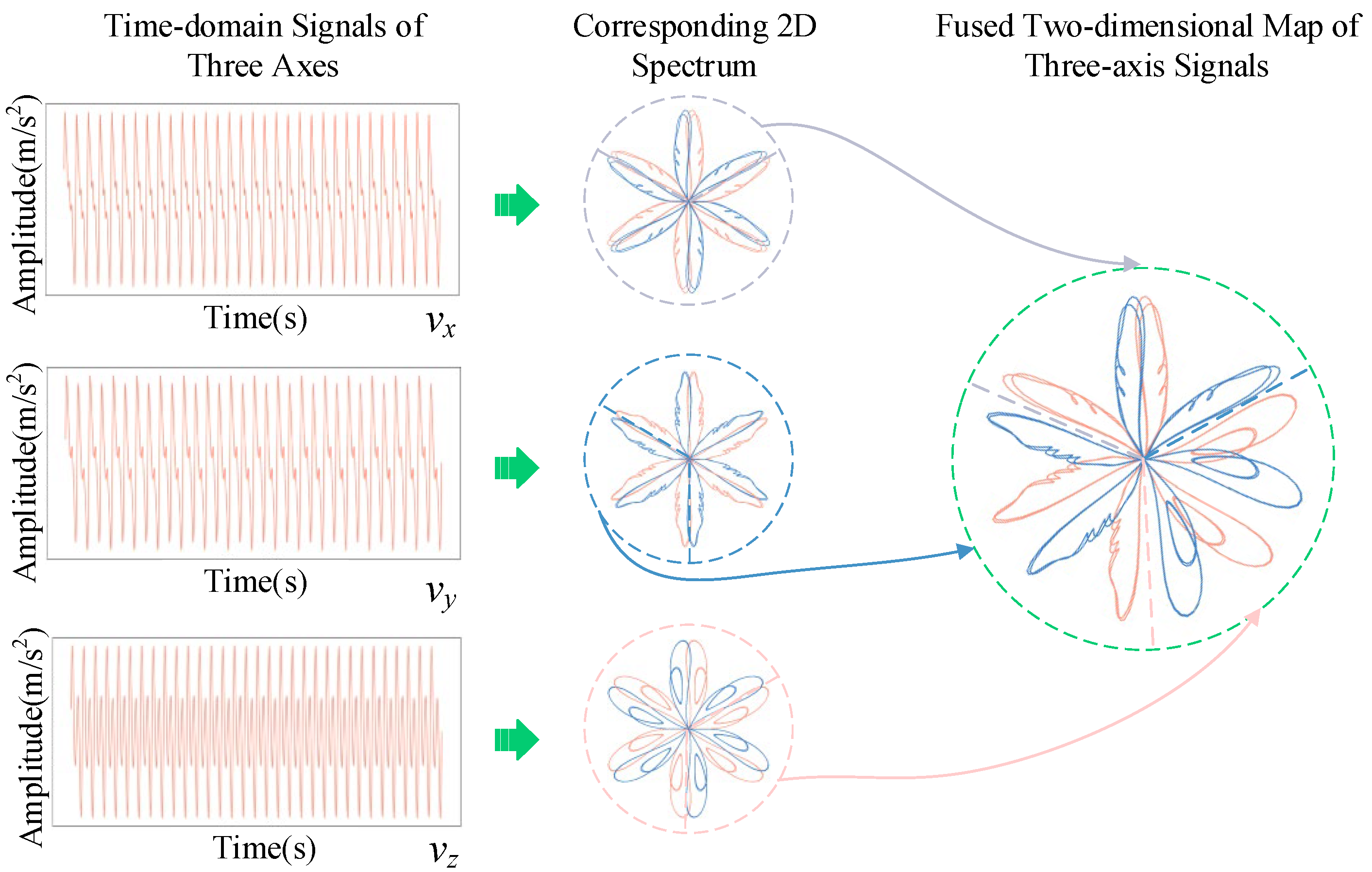

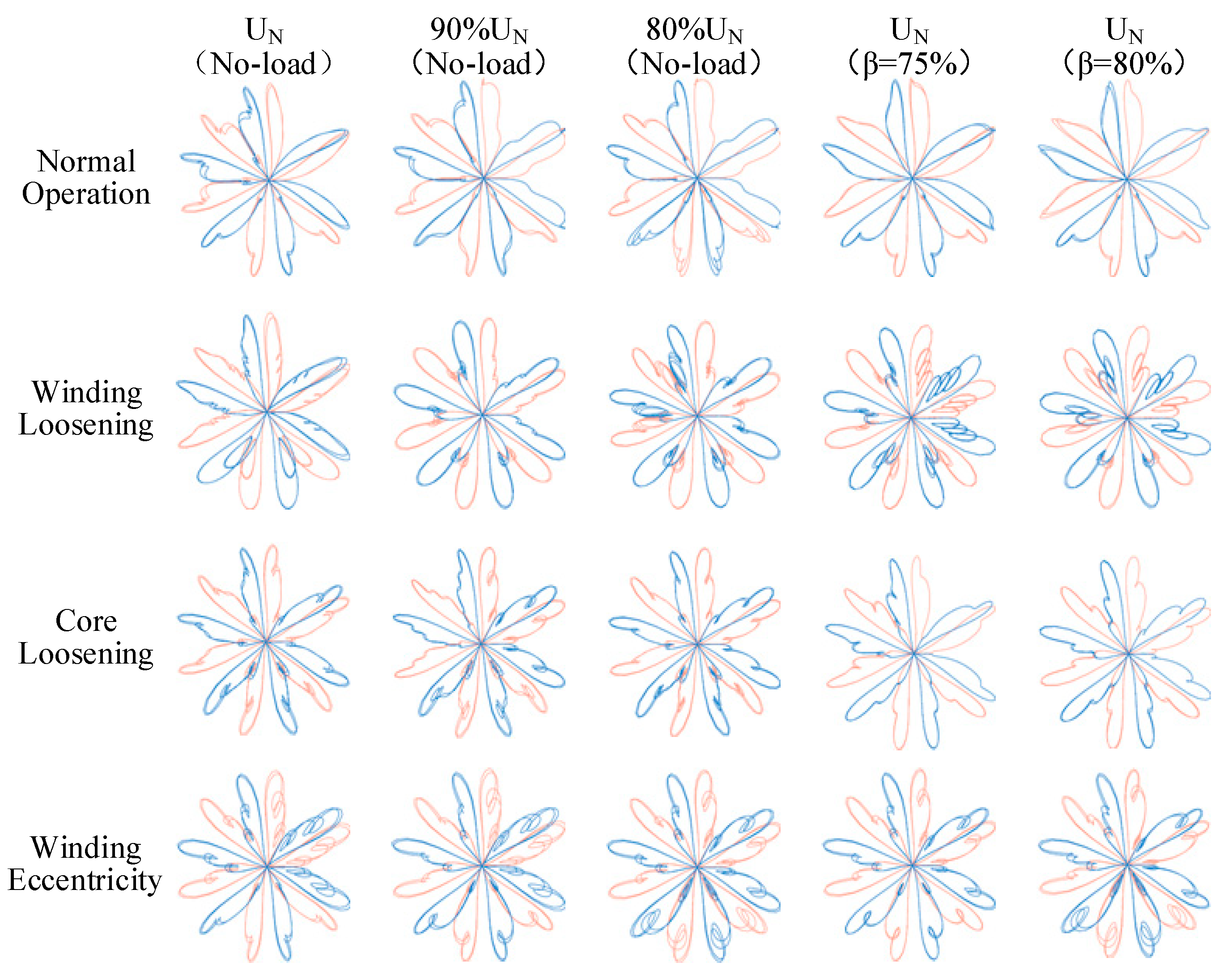

- Three-Axis Feature Aggregation and Dimensionality Reduction: An Improved Symmetrized Dot Pattern (ISDP) method is developed to aggregate and project the time- and frequency-domain features of x-, y-, and z-axis vibration signals into a unified two-dimensional map. This strategy preserves feature integrity while reducing data dimensionality and improving computational efficiency.

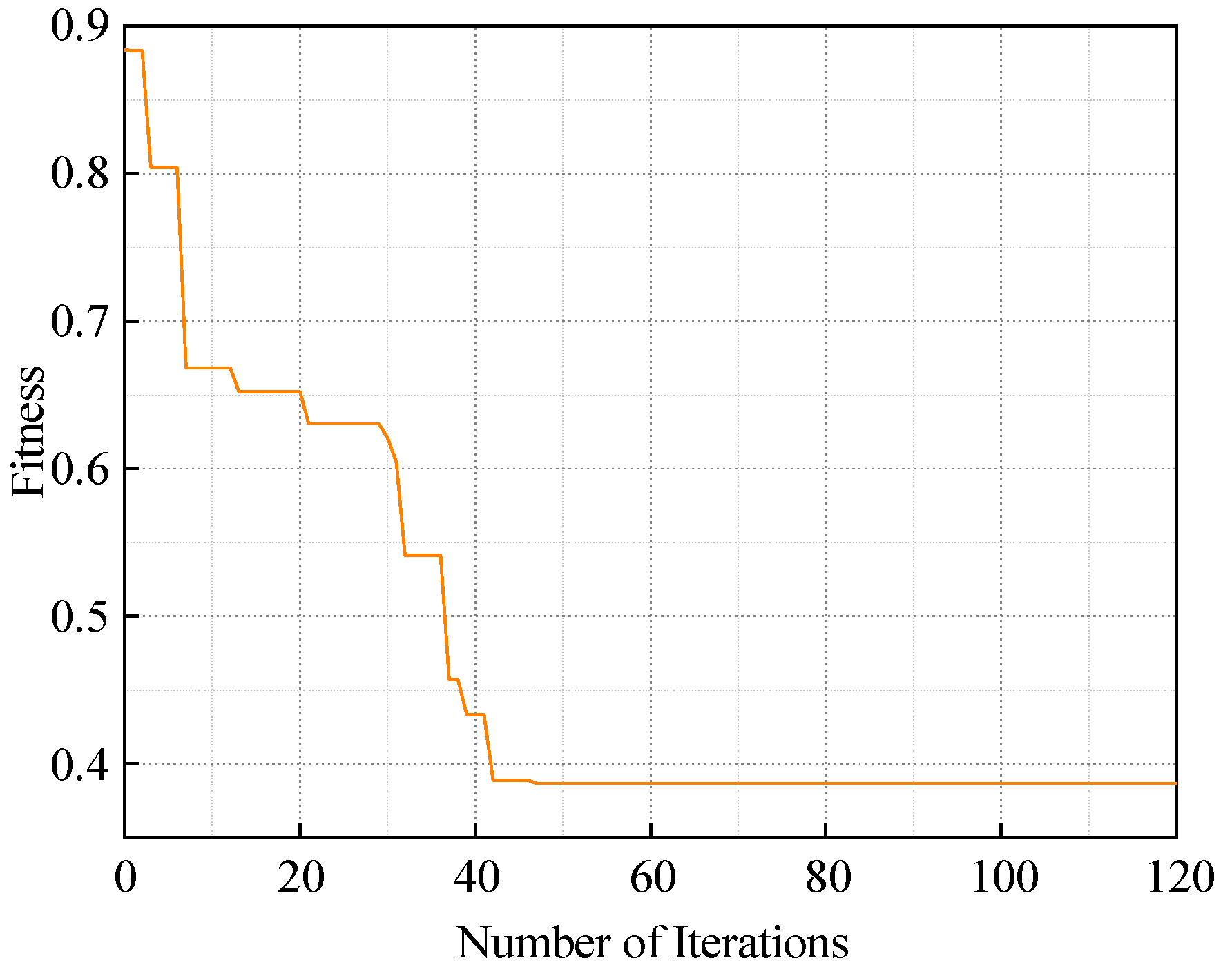

- Self-Adaptive Parameter Optimization: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is employed to automatically adjust the angle gain factor (η) and time-delay coefficient (t) of the ISDP method. This adaptive mechanism enhances inter-class separability and intra-class compactness of the feature map, effectively mitigating feature loss caused by manual, experience-based parameter selection.

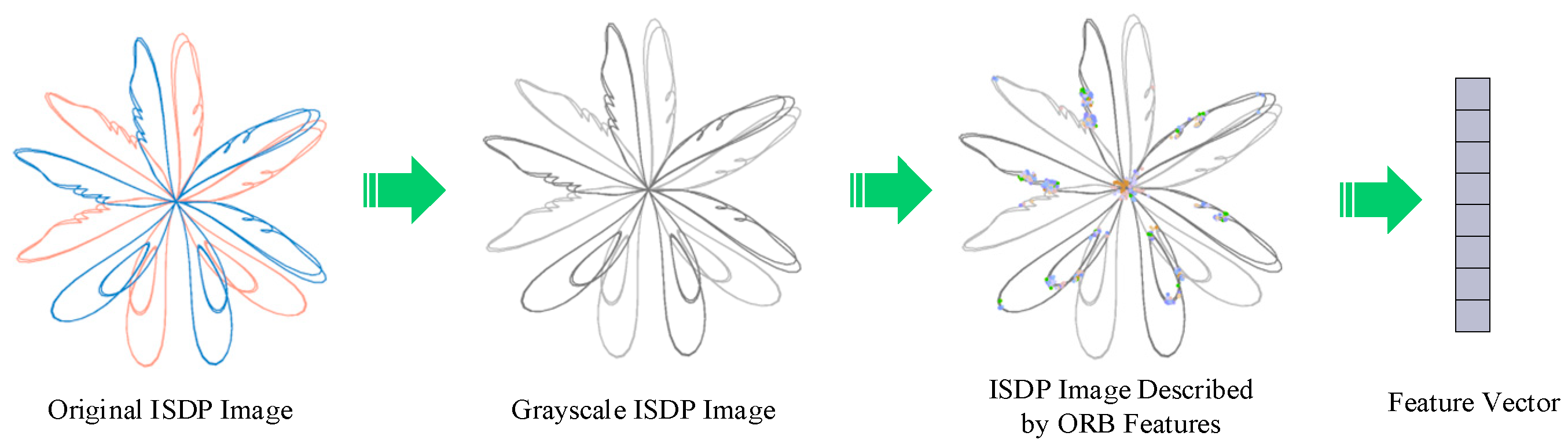

- Efficient Local Feature Extraction: The Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB) operator is applied to extract keypoint descriptors from the generated feature maps. This enables accurate capture of local distortions and texture variations while substantially reducing computational cost.

- Lightweight Classification Framework: An Adaptive Boosting Support Vector Machine (Adaboost-SVM) is integrated as the classification module, striking a balance between diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency. This framework is particularly advantageous for small-sample scenarios and real-time diagnostic requirements in practical engineering environments.

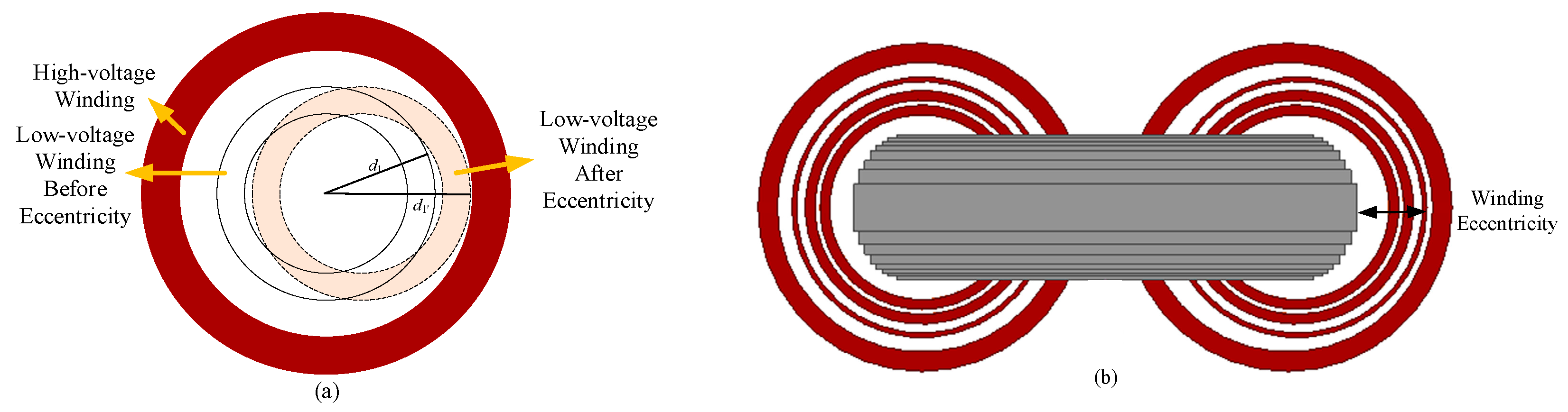

2. Vibration Modeling and Simulation of Excitation Dry-Type Transformer

2.1. Vibration Mechanisms

2.2. Multiphysics Simulation Model

2.3. Parametric Scanning and Calibration of the Model

3. Fault Diagnosis Methodology

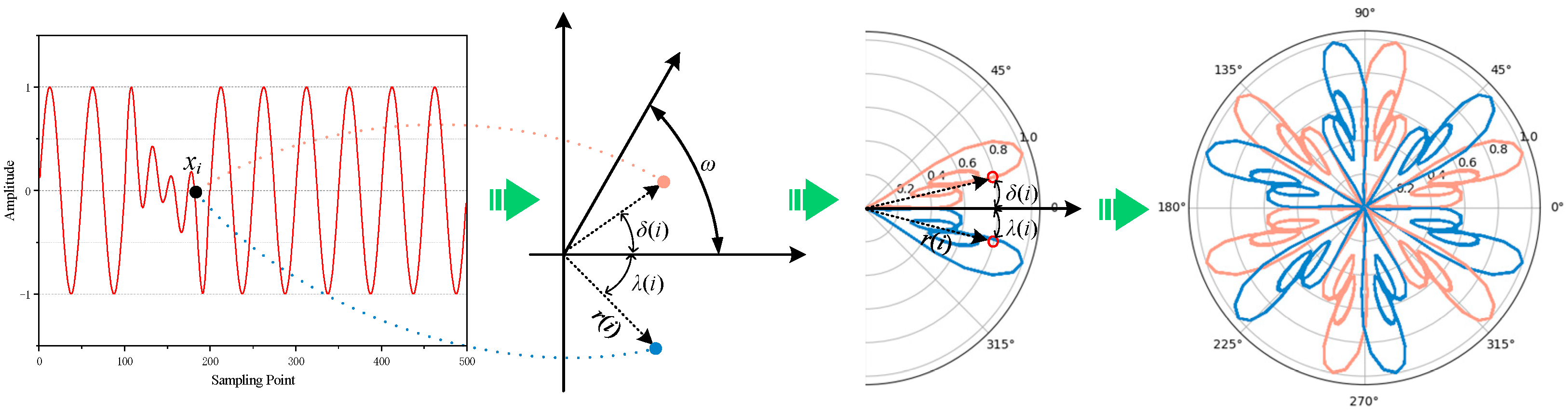

3.1. SDP Method (Symmetrized Dot Pattern Method)

3.2. ISDP Method (Improved Symmetrized Dot Pattern Method)

3.3. ORB Keypoint Feature Description Method

3.4. Construction of the Adaboost-SVM Fault Diagnosis Model

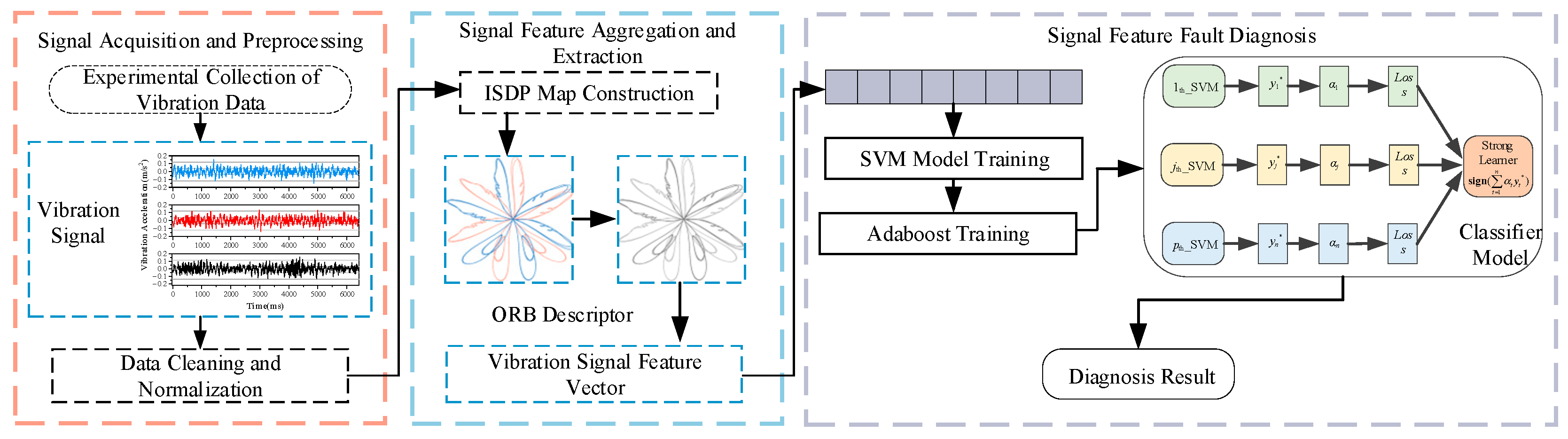

3.5. Diagnostic Process

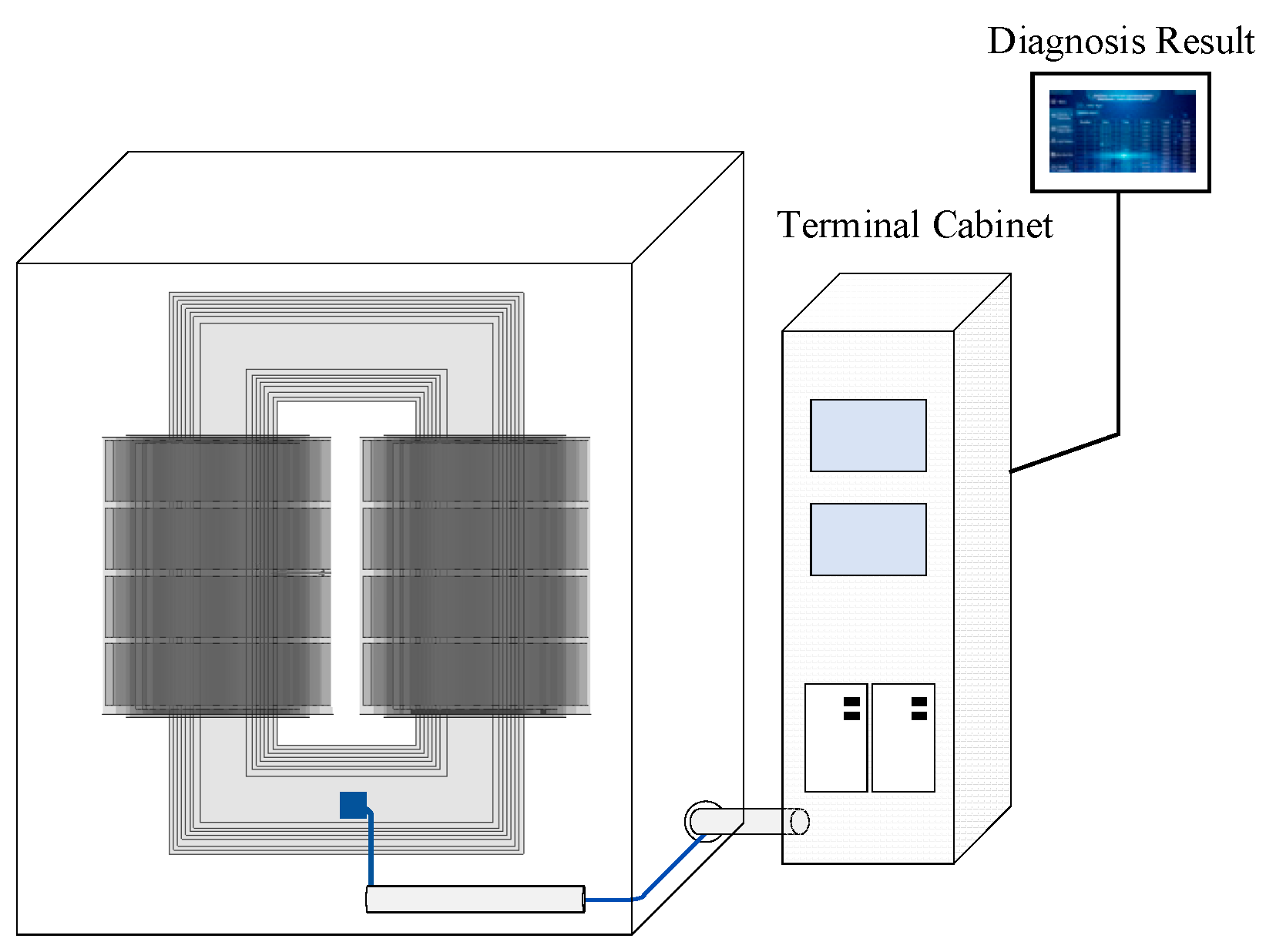

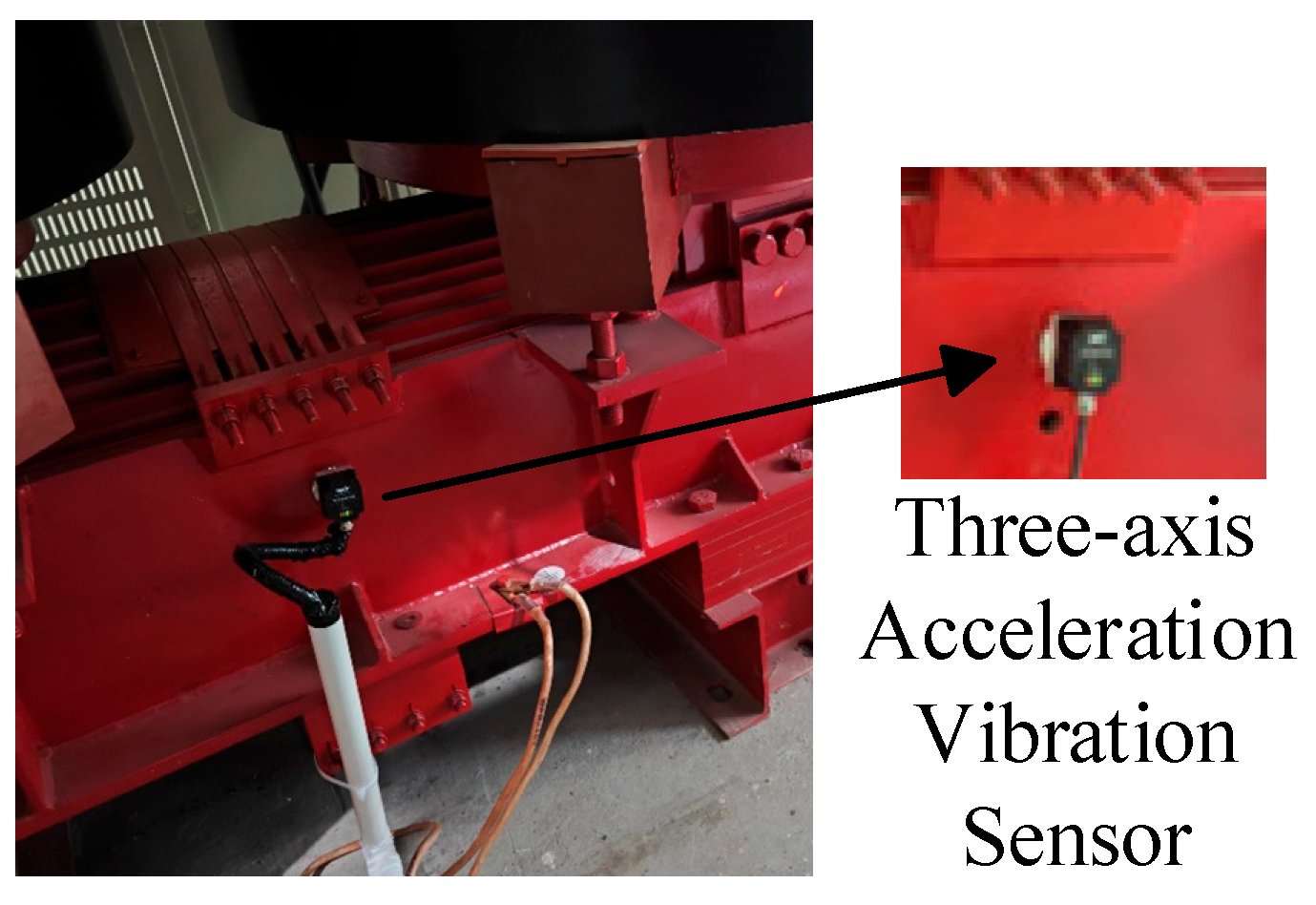

4. Field Experiments and Dataset Construction

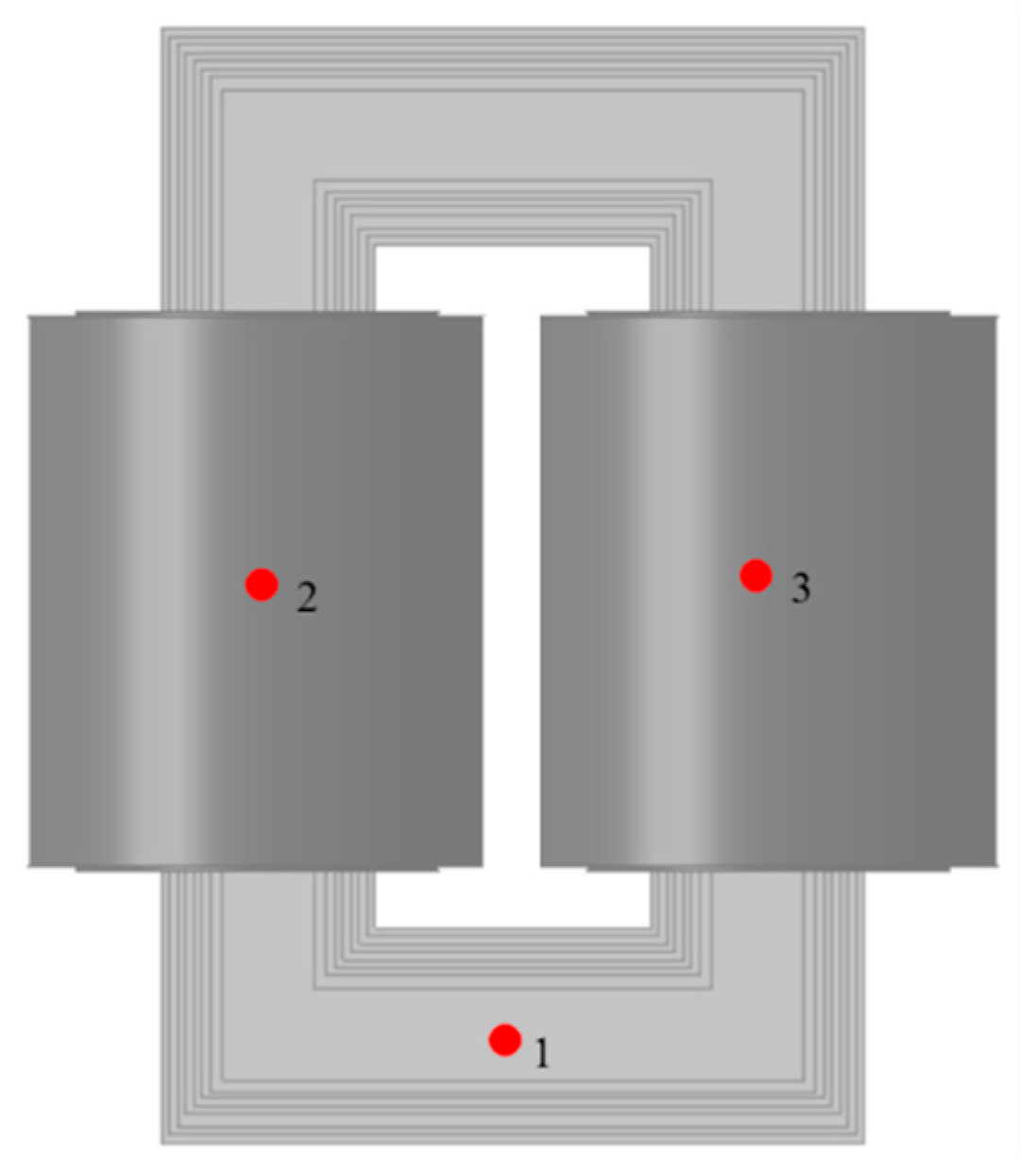

4.1. Selection of Measurement Point Locations

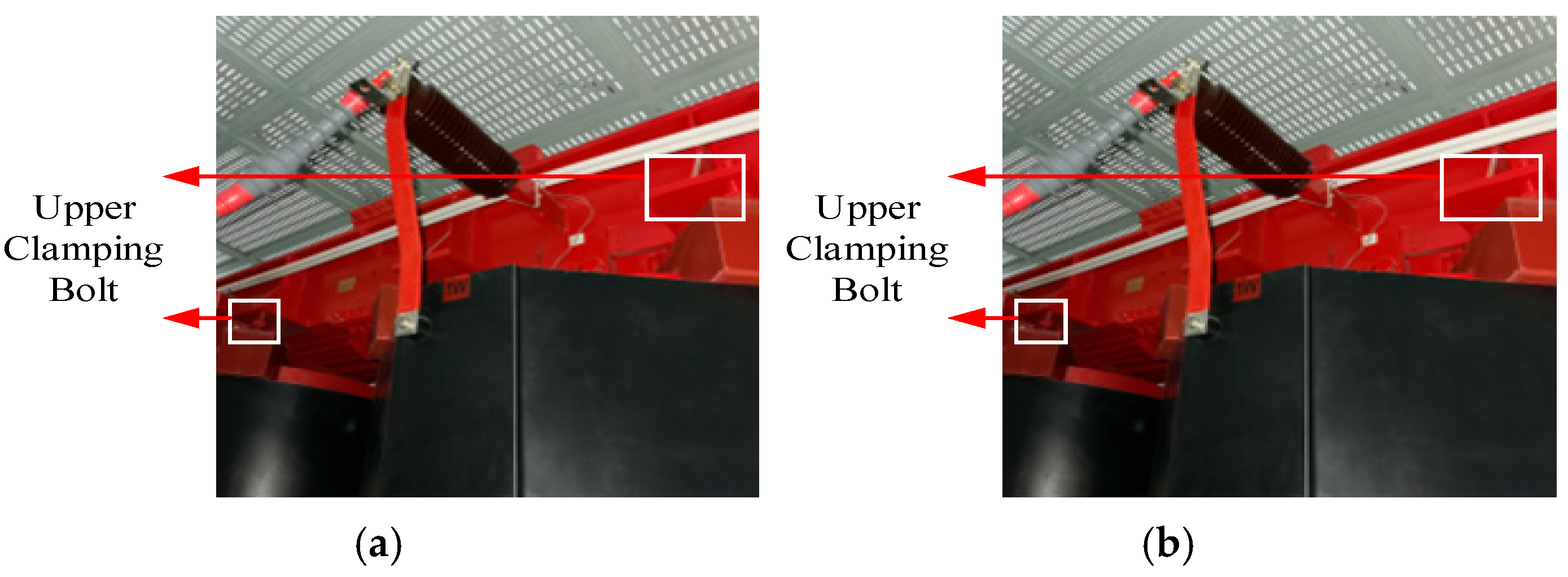

4.2. On-Site Data Collection

4.3. Dataset Construction

5. Analysis of the Experimental Results

5.1. Evaluation Metric

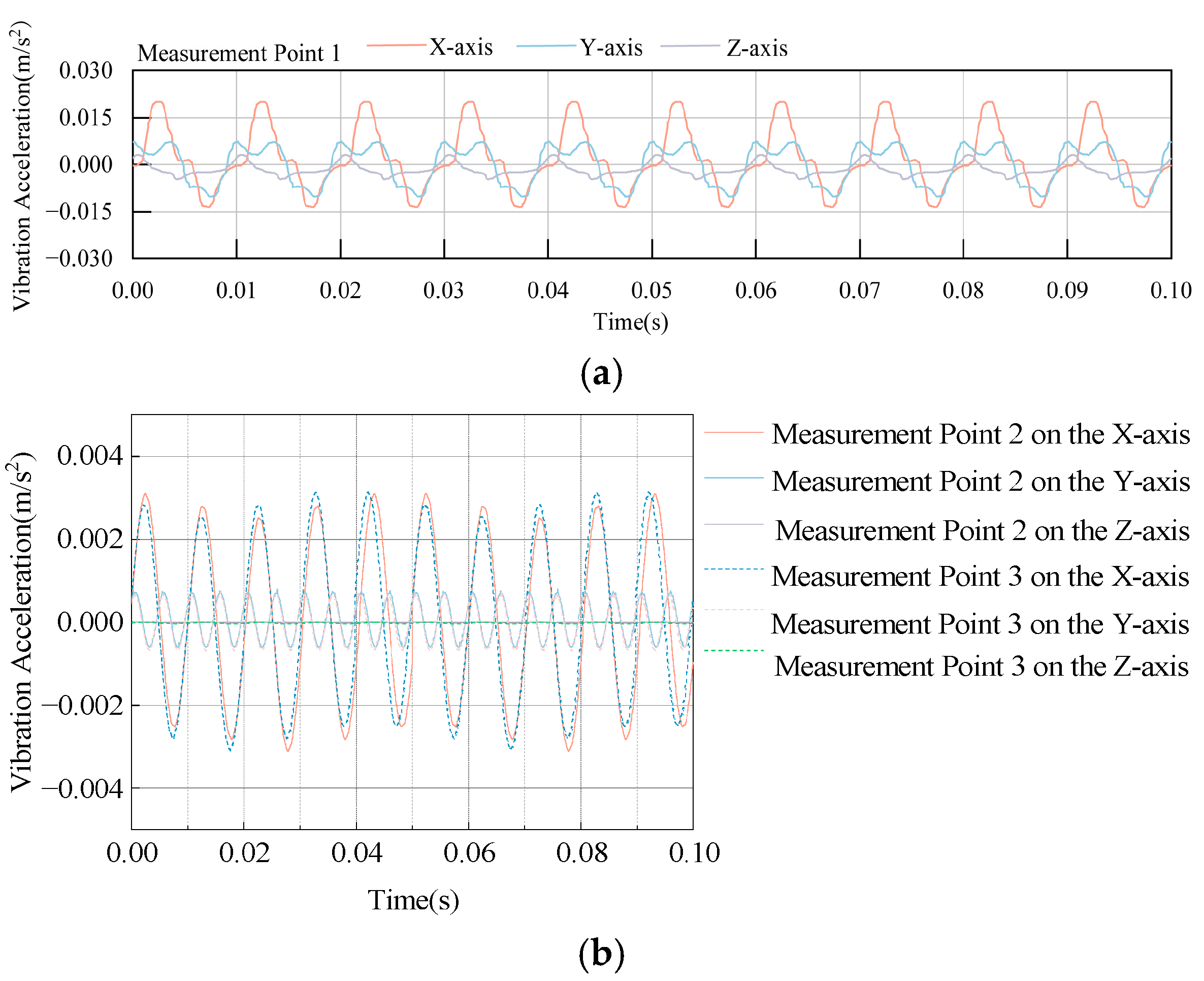

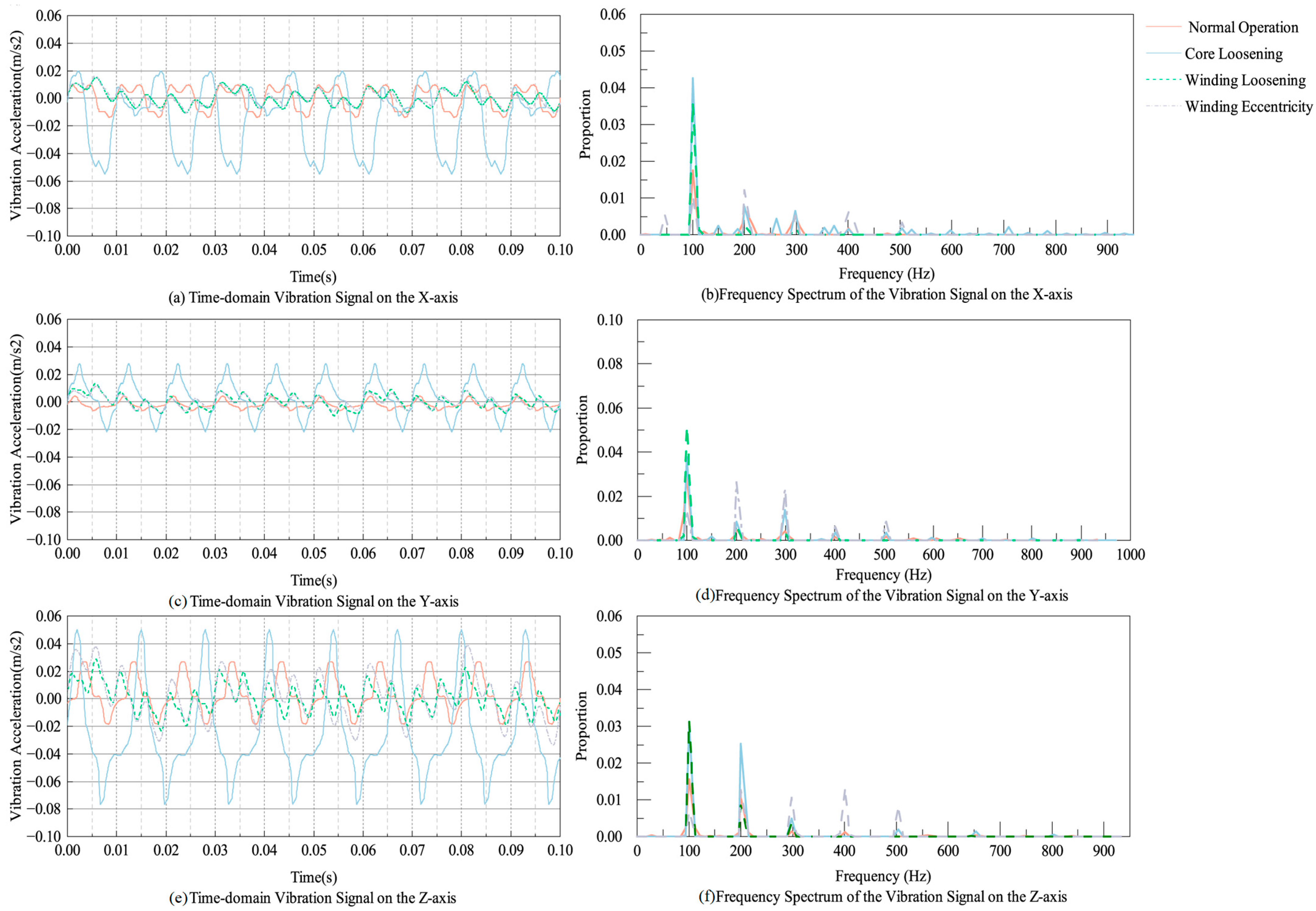

5.2. Simulation Results of Vibration Signals

5.3. Simulation Results of Fault Simulations

5.4. Analysis of Fault Diagnosis Results

5.4.1. Parameter Optimization Using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

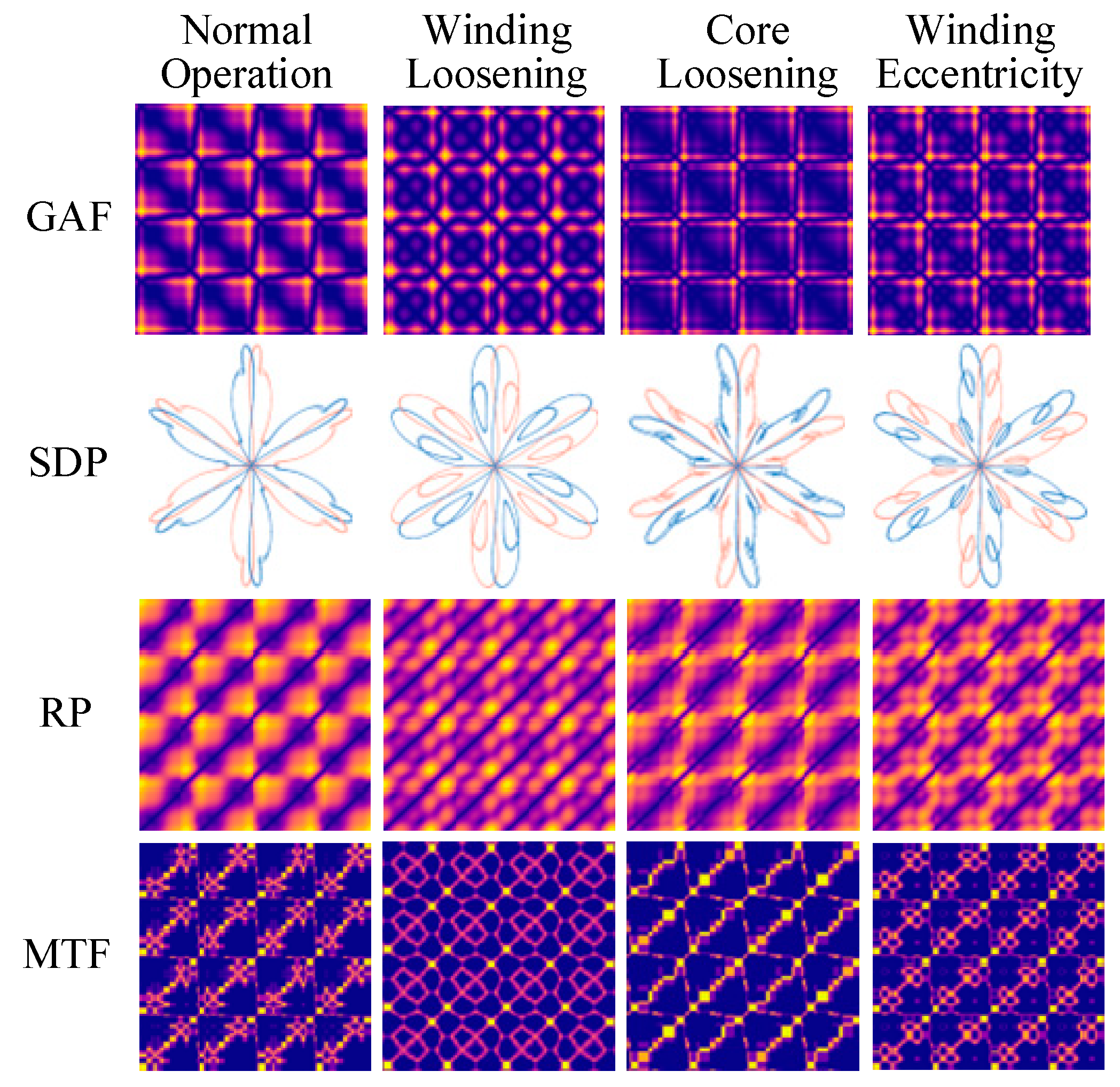

5.4.2. ISDP Image Similarity and Feature Extraction

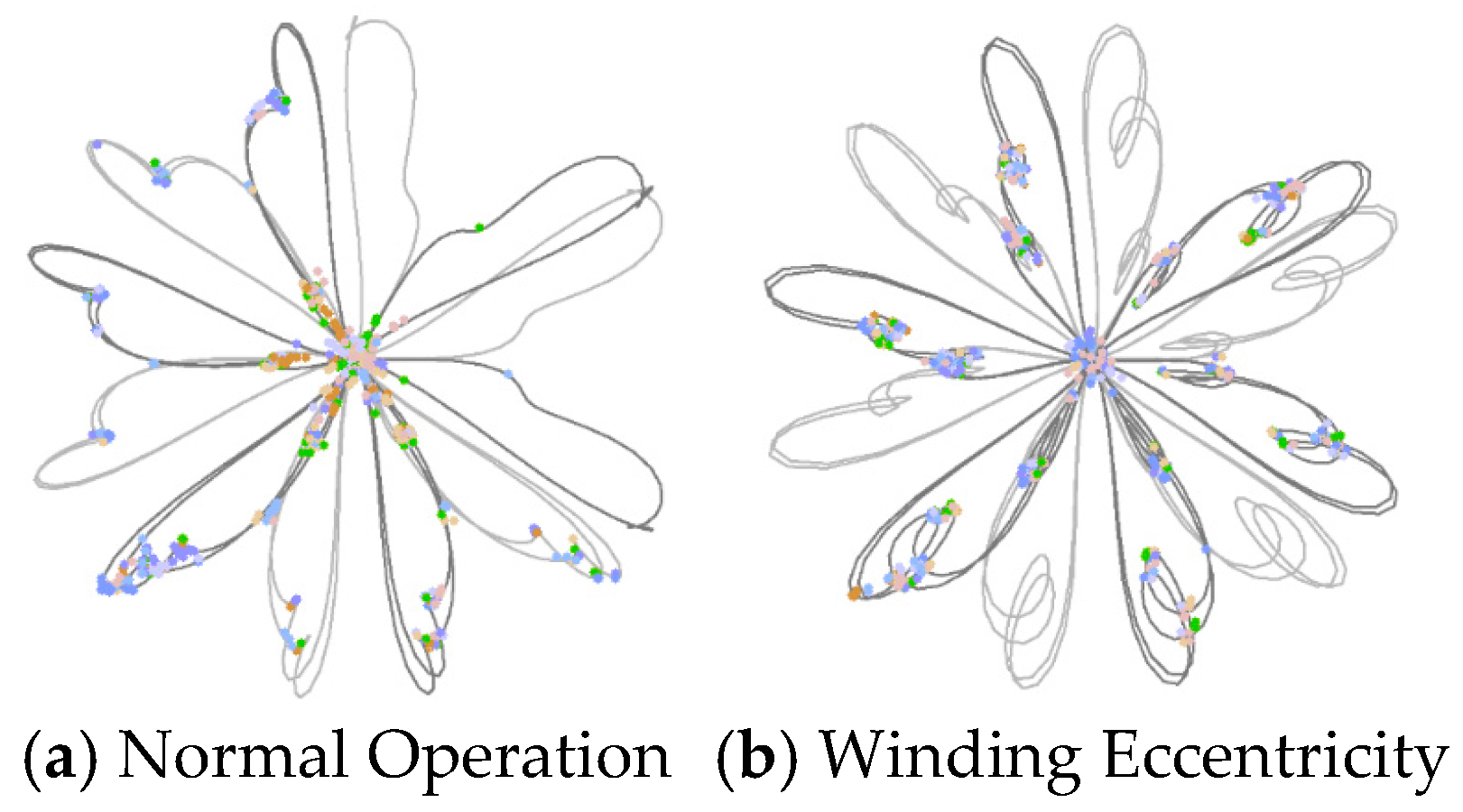

5.4.3. ISDP Feature Map Generation and Analysis

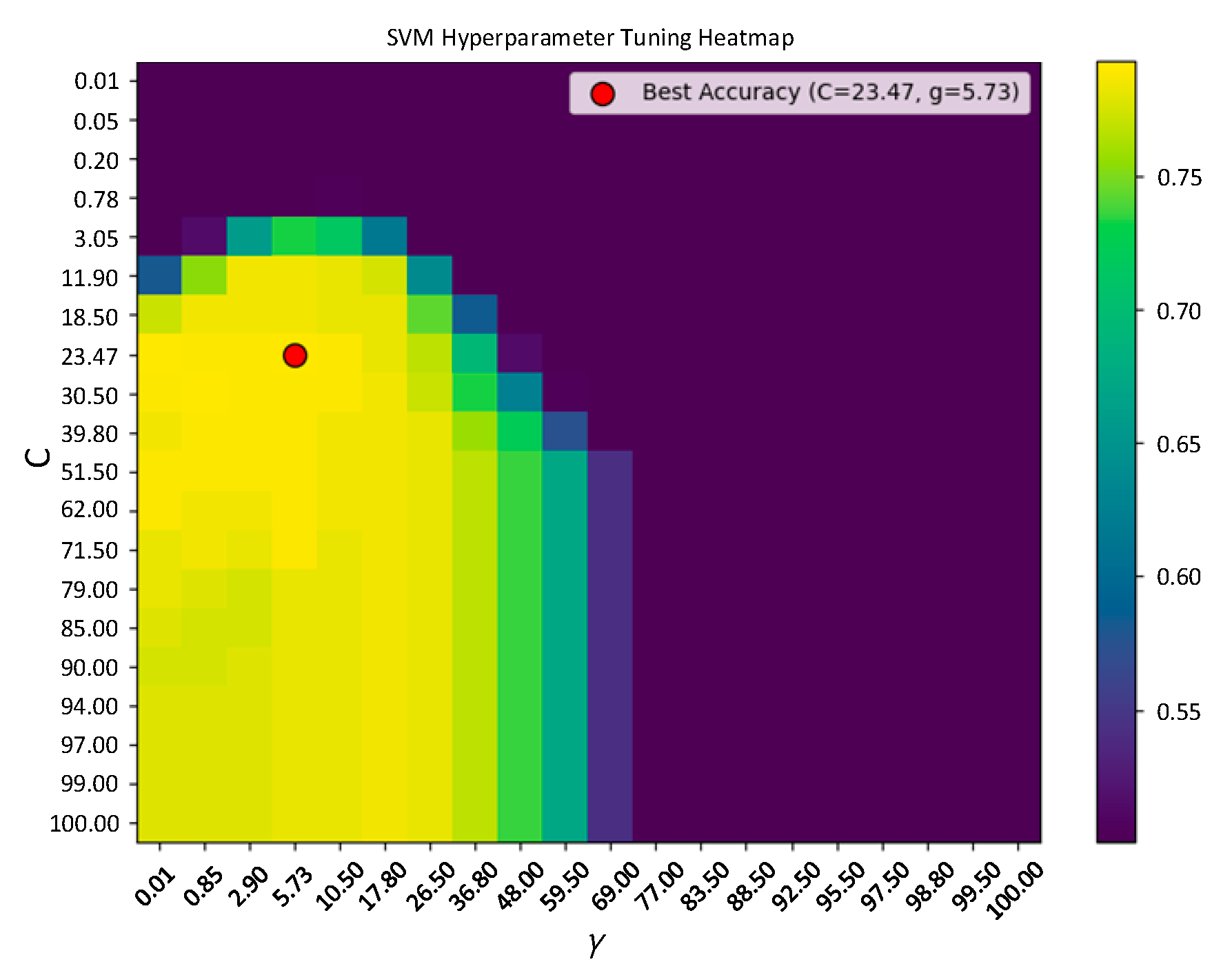

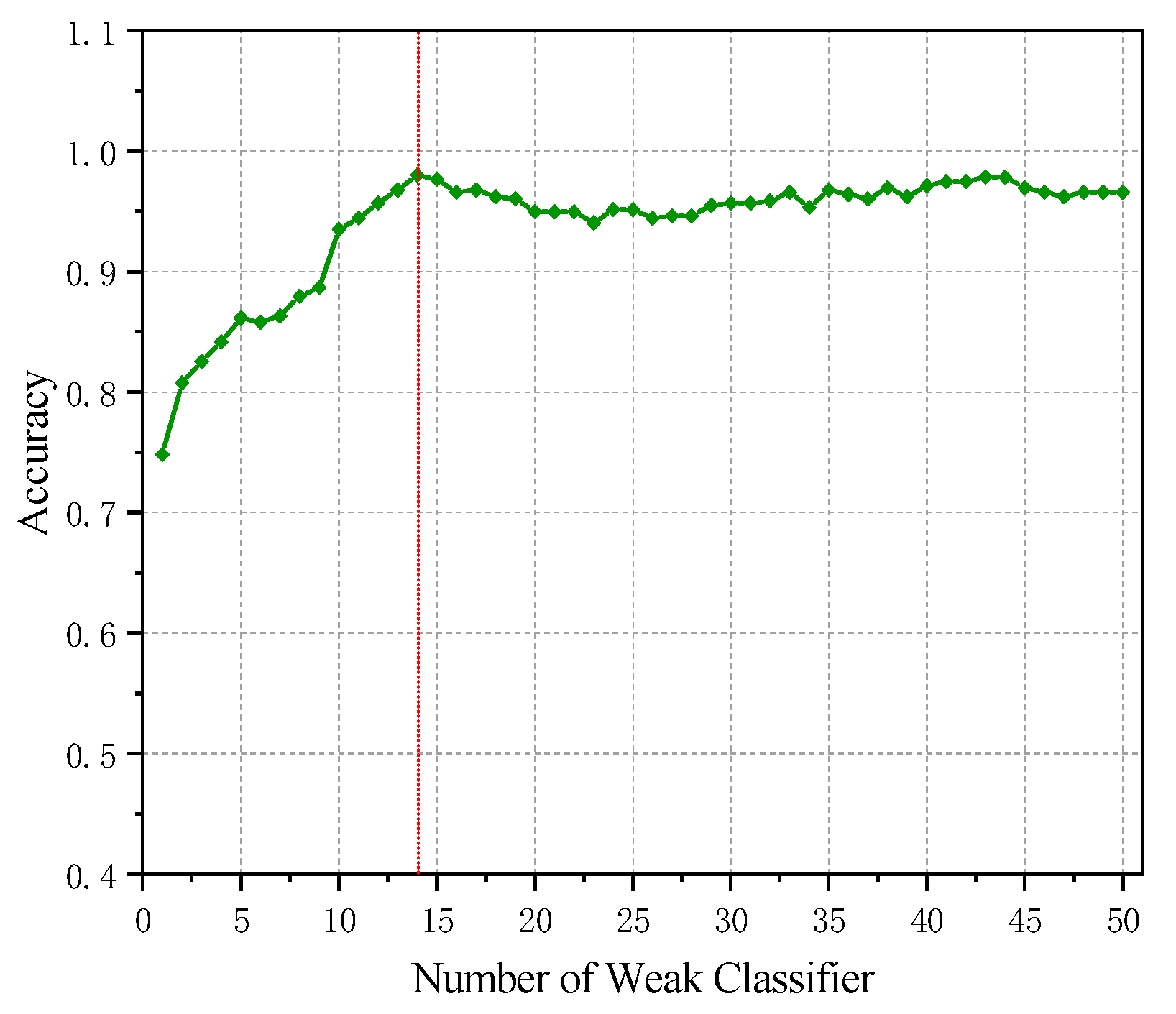

5.4.4. Adaboost-SVM Parameter Optimization for Fault Diagnosis

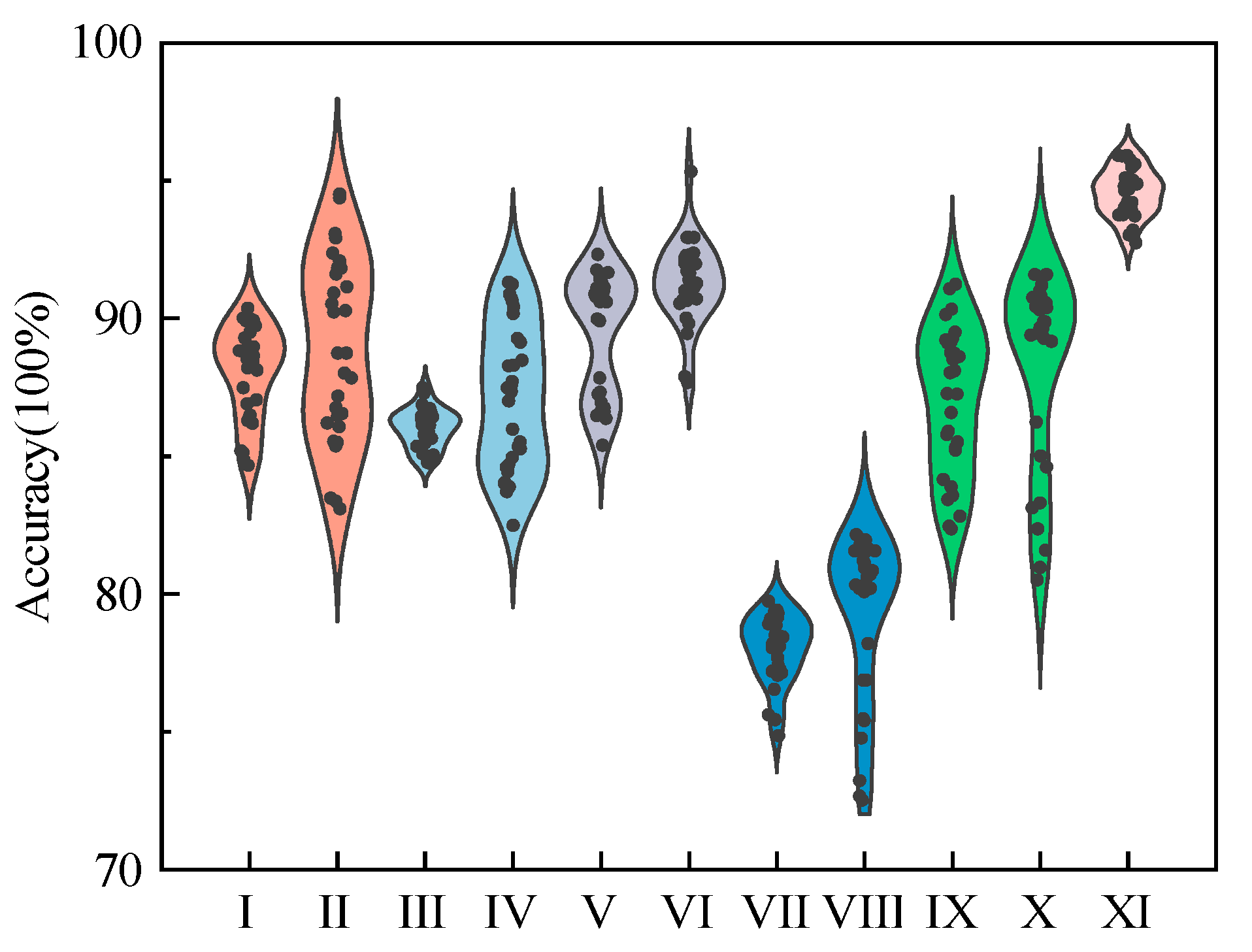

5.4.5. Performance Evaluation and Comparison of Classification Models

6. Conclusions

- Enhanced Feature Representation: The three-axis aggregation significantly improves feature representation. The improved ISDP fuses time- and frequency-domain data from all three axes. With PSO, this method outperforms traditional techniques like SDP, GAF, and MTF in terms of inter-class separability and intra-class consistency;

- Improved Computational Efficiency via ORB: ORB feature extraction enhances efficiency and sensitivity to local details, capturing distortions while reducing redundant dimensions, all while maintaining feature integrity;

- Superior Adaboost-SVM Performance: The Adaboost-SVM model achieves 94.00% accuracy, with a training time of 60 s and a testing time of 8.30 s. It outperforms models like CNN, SVM, and LightGBM, making it highly effective for real-time fault diagnosis;

- Stability and Adaptability: The method demonstrates strong stability and adaptability in multi-class fault diagnosis, maintaining minimal variation across different fault types and conditions. It is effective in resource-constrained environments, well-suited for real-time monitoring, and provides valuable support for operational decision-making, with potential for broader application in other transformer types.

- It is worth noting that although this study examined various operating conditions and parameter variations, the focus was primarily on single-excitation dry-type transformers. Cross-validation with devices of different capacities and core geometries has not yet been conducted but will be addressed in future research. However, the proposed diagnostic framework is model-independent and based on the vibration characteristics of the general electromechanical mechanism, suggesting that it is transferable across different transformer types.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDP | Symmetrized Dot Pattern |

| ISDP | Improved Symmetrized Dot Pattern |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| ORB | Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF |

| Adaboost-SVM | Adaptive Boosting Support Vector Machine |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| GAF | Gramian Angular Field |

| RP | Recurrence Plot |

| MTF | Markov Transition Field |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| BP | Backpropagation |

| VFRA | Vibration Frequency Response Analysis |

| GASF | Gramian Angular Summation Field |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| DTW | Dynamic Time Warping |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| Adaboost-BP | Adaboost with Backpropagation |

| XGBoost-SVM | Extreme Gradient Boosting with Support Vector Machine |

References

- He, D.S.; Jia, Z.D.; Wang, J.X.; Fu, J.B.; He, F.; Dai, F. Investigating temperature rise dynamics at hot-spots within dry-Type transformer windings: A comparative analysis across varied loading rates and an extrapolative computational model. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 60, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghi, M.; Zolfaghari, M.; Mohseni, A.; Nosratian-Ahour, J. Real-time transient stability estimation of power system considering nonlinear limiters of excitation system using deep machine learning: An actual case study in Iran. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virant-Doberlet, M.; Stritih-Peljhan, N.; Žunič-Kosi, A.; Polajnar, J. Functional diversity of vibrational signaling systems in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2023, 68, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, F.; Dang, Y.; Zhan, C.; Wang, S.; Ji, S. A mechanical-electromagnetic coupling model of transformer windings and its application in the vibration-based condition monitoring. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Zheng, T.; Gao, Y.; Wang, G.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X. DGA-GNN: Dynamic Grouping Aggregation GNN for Fraud Detection. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 11820–11828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, P.A.R.; Yusoff, M.; Sallehud-Din, M.T.M. Improving Transformer Failure Classification on Imbalanced DGA Data Using Data-Level Techniques and Machine Learning. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwinisin, P.; Mingotti, A.; Peretto, L.; Tinarelli, R.; Tefferi, M. Electrical Diagnosis Techniques for Power Transformers: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Instrumentation, and Research Challenges. Sensors 2025, 25, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, A.; Adhikari, A.; Dhakal, G.; Silwal, B. Partial Discharge Detection in Transformer Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Power System Technology (PowerCon), Kathmandu, Nepal, 4–6 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tag, A.; Refaat, S.S.; Kameli, S.M.; Saleh, M.A. Machine Learning Applications for Online Partial Discharge Detection, Classification, and Localization in Power Transformers: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Smart Grid and Renewable Energy (SGRE), Doha, Qatar, 10 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili Nezhad, A.; Samimi, M.H. A Review of Vibration-Based Techniques for the Condition Assessment and Failure Detection of Transformers. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, Y.; Xing, Z.; Wang, L.; Shao, K.; Lei, L.; Li, Z. Vibration Signal-Based Fusion Residual Attention Model for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 17231–17242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, O.; Ibrahim, R.A.; Zakzouk, N.E. A Lightweight Deep Learning Framework for Transformer Fault Diagnosis in Smart Grids Using Multiple Scale CNN Features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Huang, L.; Jiang, X. Residual Attention Guided Vision Transformer with Acoustic-Vibration Signal Feature Fusion for Cross-Domain Fault Diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 64, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, M.; Xiao, J.; Shen, Z.; Tang, L.; Wang, J. Random vibration-based virtual fatigue test for large-scale welded structures using frequency-domain structural stress method and its application to traction transformers. Eng. Comput. 2023, 40, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, L. Research and application of intelligent diagnosis method of mechanical fault based on transformer vibration and noise and BP neural network. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Electrical Materials and Power Equipment (ICEMPE), Chongqing, China, 11–15 April 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Ji, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, H. A novel vibration frequency response analysis method for mechanical condition detection of converter transformer windings. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 8176–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Dan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Deng, J. Multifeature extraction and semi-supervised deep learning scheme for state diagnosis of converter transformer. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Jin, M.; Huang, H. Transformer winding fault diagnosis using vibration image and deep learning. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 36, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, X.; Xu, W.; Li, W. Research on High-Frequency Modification Method of Industrial-Frequency Smelting Transformer Based on Parallel Connection of Multiple Windings. Energies 2025, 18, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.S.; Jia, Z.D.; Yue, Y.G.; Wang, J.X.; Xiong, L.R.; Xia, S.; Fu, J.B.; He, F.W. Simulation and experimental analysis of dynamic thermal rise relaxation characteristics for dry-type distribution transformer. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2025, 26, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamian, M.; Bigdeli, M.; Abu-Siada, A. High frequency modeling of dry type detuned reactor for transient studies: Simulation and experimental analyses. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 228, 110102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q. Research on Simulation Analysis and Joint Diagnosis Algorithm of Transformer Core-Loosening Faults Based on Vibration Characteristics. Energies 2025, 18, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, X. Numerical Analysis of Flow-Induced Resonance in Pilot-Operated Molten Salt Control Valves. Energies 2025, 18, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrych, M.; Gorzkiewicz, D.; Deja, M.; Chodnicki, M. Application of 3D scanning and computer simulation techniques to assess the shape accuracy of welded components. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behara, R.K.; Saha, A.K. Comparative Performance Analysis of Deep Learning-Based Diagnostic and Predictive Models in Grid-Integrated Doubly Fed Induction Generator Wind Turbines. Energies 2025, 18, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, R.I.; Harjoko, A. Improved ORB Algorithm Through Feature Point Optimization and Gaussian Pyramid. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yao, L.; Xu, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Horticultural image feature matching algorithm based on improved ORB and LK optical flow. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Anand, R.S. Bearing fault diagnosis using multiple feature selection algorithms with SVM. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2024, 13, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.S.; Zaidi, S.S.H. Adaboost ensemble approach with weak classifiers for gear fault diagnosis and prognosis in dc motors. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, A.M.; Greenland, S. Causal directed acyclic graphs. JAMA 2022, 327, 1083–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.T.; Hu, M.; Wang, C.R.; Li, D.; Chen, D.C.; Ouyang, C.L.; Bai, Y.Z.; Qu, S.B.; Zhou, Z.B. A method for high-precision measuring differential transformer asymmetry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2023, 94, 065006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, J. Design and simulation of micro piezoelectric fiber triaxial acceleration sensor. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2483, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61158-2:2023; Industrial Communication Networks—Fieldbus Specifications—Part 2: Physical Layer Specification and Service Definition. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Isari, A.A.; Ghaffarkhah, A.; Hashemi, S.A.; Wuttke, S.; Arjmand, M. Structural design for EMI shielding: From underlying mechanisms to common pitfalls. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X. Variational multi-harmonic duality mode pursuit method for extracting repetitive transient components from vibration signals. Measurement 2024, 225, 113987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, K.; Huang, C.; Zhu, P.; Wu, Q.; Hao, J. Hybrid DWT NLM method with NOA optimization for ECG signal denoising. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Wen, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Shen, G. A Visual Fault Detection Method for Induction Motors Based on a Zero-Sequence Current and an Improved Symmetrized Dot Pattern. Entropy 2022, 24, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Z.; Wang, D. GAF-MAE: A self-supervised automatic modulation classification method based on Gramian angular field and masked autoencoder. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2023, 10, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Iu, H.H.C. A new fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on Markov transition field and CNN. Entropy 2022, 24, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xia, L.; Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Bai, L.; Wang, S. A fault diagnosis method of rolling bearing based on improved recurrence plot and convolutional neural network. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 10767–10775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Methods | Core Principles | Advantages | Disadvantages | Application Fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Gas Analysis (DGA) [5,6] | Detects gas types and concentrations in transformer oil to identify faults. | Mature technology; rich data accumulation. | Slow response; hard for real-time diagnosis. | Fault diagnosis of oil-immersed transformers. |

| Traditional Electrical Detection [7] | Measures parameters (e.g., resistance) to detect faults. | Simple, low-cost, versatile equipment. | Requires shutdown; low accuracy; human-dependent. | Fault screening for small to medium-sized transformers. |

| Partial Discharge Detection [8,9] | Captures discharge signals to locate faults. | Early fault detection; strong fault location. | Susceptible to interference; complex equipment. | Online monitoring of transformer insulation faults. |

| Single Vibration Signal Analysis [10,11] | Analyzes vibration signals for mechanical faults. | Non-invasive; sensitive to mechanical faults. | Prone to noise; limited by single-channel data. | Initial mechanical fault detection in transformers. |

| Deep Learning Diagnostics [12] | Classifies faults using deep learning (e.g., CNN, BP neural networks). | High accuracy; automatic feature extraction. | Needs labeled data; high computational cost. | Offline diagnosis of labeled transformer data. |

| Multi-source Signal Fusion [13] | Combines vibration, noise, and electrical signals for improved diagnosis. | Comprehensive; enhances accuracy and robustness. | Requires synchronized data and complex algorithms. | Multi-fault diagnosis under complex conditions. |

| Geometric Parameters | Value | Technical Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Voltage Winding Inner/Outer Radius | 278/303 mm | Number of Phases | 3 |

| High Voltage Winding Inner/Outer Radius | 385/415 mm | Rated Voltage (High/Low Voltage Windings) | 24/1.1 kV |

| High/Low Voltage Winding Height | 1020 mm | Rated Current (High/Low Voltage Windings) | 231/5039 A |

| Core Radius | 475 mm | Rated Capacity | 3 × 3200 kVA |

| Core Height | 2070 mm | Rated Frequency | 50 Hz |

| Silicon Steel Sheet Thickness | 3.3 mm | Insulation Class | F |

| Parameter | Normal | 20% Loosening | 40% Loosening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Modulus (Pa) | 1.16 × 1011 | 9.28 × 1010 | 6.96 × 1010 |

| Parameter | Initial Value | Final Value | Step Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-voltage Side Voltage | 23.5 kV | 29.5 kV | 0.1 kV |

| High-voltage Side Winding Resistance | 0.5 Ω | 5 Ω | 0.1 Ω |

| Low-voltage Side Winding Resistance | 0.01 Ω | 0.3 Ω | 0.002 Ω |

| Low-voltage Side Load Resistance | 10 Ω | 100 Ω | 1 Ω |

| Operating Condition | UN (No-Load) | 90%UN (No-Load) | 80%UN (No-Load) | UN (β = 75%) | UN (β = 80%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Operation | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 600/200/200 |

| Winding Loosening | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 600/200/200 |

| Core Loosening | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 120/40/40 | 600/200/200 |

| Winding Eccentricity | 120/40/40 * | 120/40/40 * | 120/40/40 * | 120/40/40 * | 120/40/40 * | 600/200/200 |

| Operating Condition | DTW Distance | Spectral Coherence |

|---|---|---|

| No-load Normal Operation | 0.23 | 0.76 |

| No-load Winding Loosening | 0.39 | 0.83 |

| No-load Core Loosening | 0.37 | 0.78 |

| 75% Load Normal Operation | 0.35 | 0.83 |

| Serial Number | Method | Accuracy (%) | Training Time (s) | Testing Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⅰ | GAF + VGG-16 | 87.50 | 6200.00 | 38.00 |

| Ⅱ | GAF + ResNet | 87.90 | 7500.00 | 40.80 |

| Ⅲ | SDP + VGG-16 | 85.50 | 5500.00 | 18.50 |

| Ⅳ | SDP + ResNet | 86.50 | 5710.00 | 22.80 |

| Ⅴ | ISDP + VGG-16 | 89.00 | 5600.00 | 22.80 |

| Ⅵ | ISDP + ResNet | 91.50 | 5980.00 | 26.10 |

| Ⅶ | RP + VGG-16 | 77.50 | 5700.00 | 24.40 |

| Ⅷ | RP + ResNet | 79.00 | 6030.00 | 27.20 |

| Ⅸ | MTF + VGG-16 | 86.50 | 6800.00 | 32.00 |

| Ⅹ | MTF + ResNet | 88.00 | 6900.00 | 37.10 |

| XI | ISDP + ORB + Adaboost-SVM | 94.00 | 60.00 | 8.30 |

| Model | td | ts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 85.53% | 84.20% | 51.03 s | 6.95 s |

| LightGBM | 91.25% | 89.71% | 65.02 s | 7.81 s |

| Adaboost-BP | 93.12% | 92.72% | 120.42 s | 9.45 s |

| XGBoost-SVM | 92.59% | 91.21% | 64.93 s | 7.89 s |

| CNN | 90.70% | 89.74% | 160.97 s | 9.96 s |

| Adaboost-SVM | 94.00% | 93.50% | 60.00 s | 8.30 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, J.; Bao, P.; Zu, W.; Deng, Y.; Chen, S.; Ma, L.; Zhao, P.; Dou, J. Fault Diagnosis Method for Excitation Dry-Type Transformer Based on Multi-Channel Vibration Signal and Visual Feature Fusion. Sensors 2025, 25, 7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247460

Liu Y, Yu M, Wang J, Bao P, Zu W, Deng Y, Chen S, Ma L, Zhao P, Dou J. Fault Diagnosis Method for Excitation Dry-Type Transformer Based on Multi-Channel Vibration Signal and Visual Feature Fusion. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247460

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yang, Mingtao Yu, Jingang Wang, Peng Bao, Weiguo Zu, Yinglong Deng, Shiyi Chen, Lijiang Ma, Pengcheng Zhao, and Jinyao Dou. 2025. "Fault Diagnosis Method for Excitation Dry-Type Transformer Based on Multi-Channel Vibration Signal and Visual Feature Fusion" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247460

APA StyleLiu, Y., Yu, M., Wang, J., Bao, P., Zu, W., Deng, Y., Chen, S., Ma, L., Zhao, P., & Dou, J. (2025). Fault Diagnosis Method for Excitation Dry-Type Transformer Based on Multi-Channel Vibration Signal and Visual Feature Fusion. Sensors, 25(24), 7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247460