TGDNet: A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Defect Detection Method for Transparent Industrial Headlight Glass

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A dataset was constructed, and SWAM was developed to enhance class-imbalanced defect images. This process resulted in the LDD, comprising 5532 images with balanced category distribution and real-world applicability.

- A transparent glass defect detection algorithm named TGDNet was proposed, which includes the TGFE module in the backbone and the TGD attention mechanism. These components enable adaptive feature extraction for irregular small defect targets, improving both detection accuracy and efficiency. They address the challenges posed by diverse defect shapes and inconsistent defect sizes in transparent glass defect detection.

- Subsequent experiments demonstrate that TGDNet exhibits significant advantages in both detection accuracy and speed compared to multiple classical defect detection algorithms on the LDD.

2. Related Works

2.1. Dataset Enhancing

2.2. Defect Detection

2.3. Attention Mechanism

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

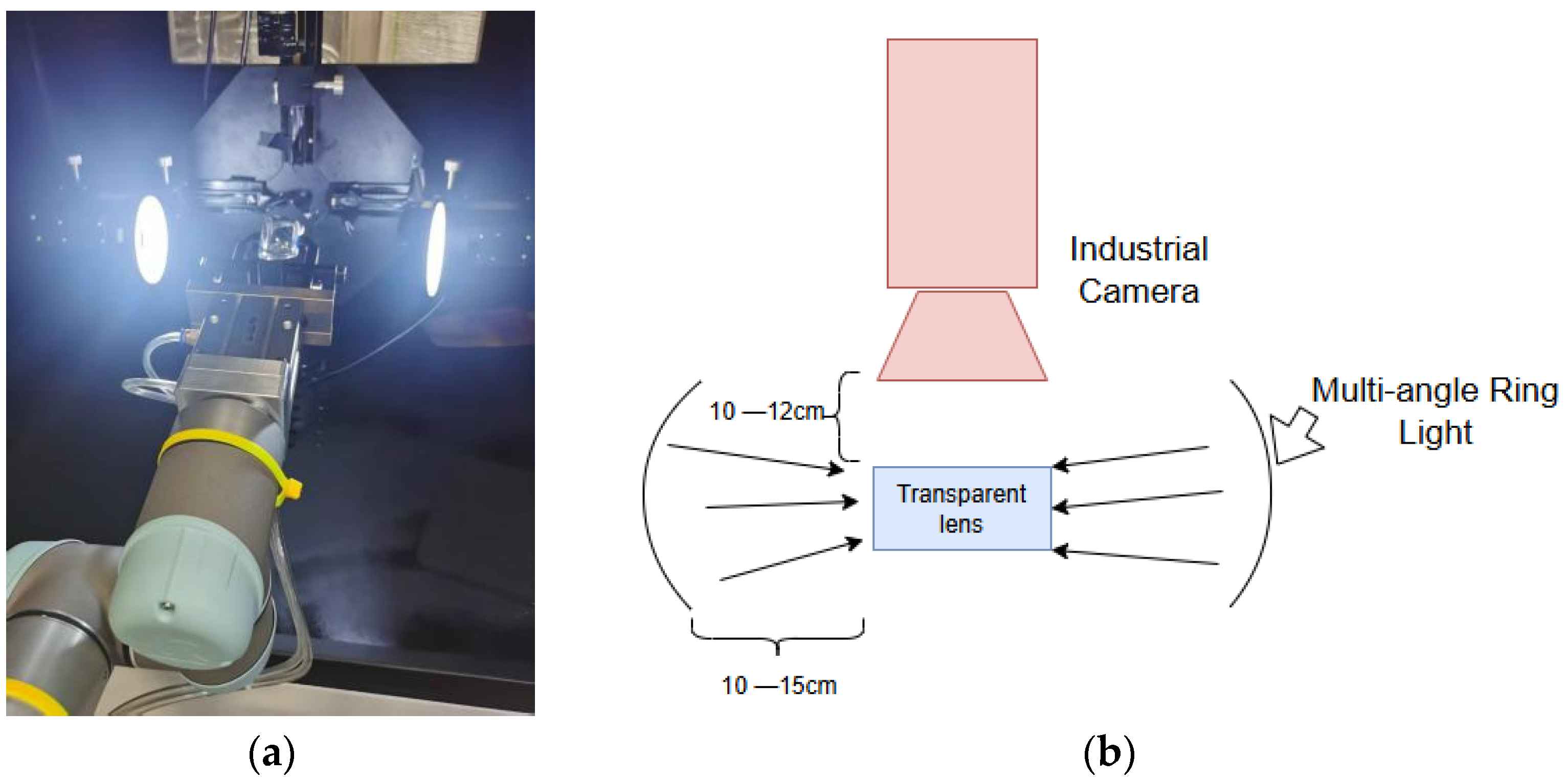

3.2. Dataset Preparation and Lighting Configuration

3.3. TGDNet

3.3.1. TGFE Block

3.3.2. Transparent Glass Defect Attention Mechanism

3.3.3. Neck of Network

4. Experiments

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Experiment Results

4.3.1. Accuracy Comparison

4.3.2. Efficiency Comparison

4.3.3. Ablation Experiment

4.3.4. Visualization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H. Multi-scale defect detection of printed circuit board based on feature pyramid network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), Dalian, China, 28–30 June 2021; pp. 911–914. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Jing, J.; Lu, P.; Song, S. Improved MobileNetV2-SSDLite for automatic fabric defect detection system based on cloud-edge computing. Measurement 2022, 201, 111665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Chen, J.; Lu, J. Subdomain adaptation network with category isolation strategy for tire defect detection. Measurement 2022, 204, 112046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, W.; Shen, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Chen, Z.; Cao, Y. A comprehensive review of defect detection in 3C glass components. Measurement 2020, 158, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yang, R.; Li, S.; Hu, R.; Li, X. SSGD: A smartphone screen glass dataset for defect detection. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yao, Y.; Wen, R.; Liu, Q. Dual-modal illumination system for defect detection of aircraft glass canopies. Sensors 2024, 24, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, S.; Lv, H.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J. Defect detection in automotive glass based on modified YOLOv5 with multi-scale feature fusion and dual lightweight strategy. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 8099–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, G. A lightweight and robust detection network for diverse glass surface defects via scale-and shape-aware feature extraction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 153, 110640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisantal, M.; Wojna, Z.; Murawski, J.; Naruniec, J.; Cho, K. Augmentation for small object detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvornik, N.; Mairal, J.; Schmid, C. Modeling visual context is key to augmenting object detection datasets. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 364–380. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.C.; Tenenholtz, N.A.; Rogers, J.K.; Schwarz, C.G.; Senjem, M.L.; Gunter, J.L.; Andriole, K.P.; Michalski, M. Medical image synthesis for data augmentation and anonymization using generative adversarial networks. In International Workshop on Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging, Proceedings of the Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging Third International Workshop SASHIMI 2018, Granada, Spain, 16 September 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Lin, H. Defect image sample generation with GAN for improving defect recognition. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Zhu, W.; Yu, A.; Jin, M.; Zhang, J. Rotation invariant local binary pattern based on glcm for fluorescent tube defects classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), Chengdu, China, 15–18 July 2018; Volume 2, pp. 612–618. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Xiao, X.; Ge, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhao, S.; Jin, X. ScratchNet: Detecting the scratches on cellphone screen. In Computer Vision, Proceedings of the CCF Chinese Conference on Computer Vision, Tianjin, China, 11–14 October 2017; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chi, C.; Yao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Li, S.Z. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–18 June 2020; pp. 9759–9768. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; Fang, J.; Yifu, Z.; Wong, C.; Montes, D.; et al. Ultralytics/Yolov5: v7.0-Yolov5 Sota Real Time Instance Segmentation; Zenodo: Geneve, Schwitzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Kang, X. Mobile-YOLO: An accurate and efficient three-stage cascaded network for online fiberglass fabric defect detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 134, 108690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. YOLOv8-QSD: An improved small object detection algorithm for autonomous vehicles based on YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 2513916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; An, P.; Hong, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, T. UAV-YOLOv8: A small-object-detection model based on improved YOLOv8 for UAV aerial photography scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23, 7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Dong, Y. YOLO-SE: Improved YOLOv8 for remote sensing object detection and recognition. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. YOLO-Drone: An optimized YOLOv8 network for tiny UAV object detection. Electronics 2023, 12, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing System 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, Z.; Song, G.; Liu, Y. Detrs with collaborative hybrid assignments training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 6748–6758. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; Xu, M.; Sun, Q.; Yang, Y. LCCD-Net: A Lightweight Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network for Cigarette Capsules Defect Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 041012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Yang, J. Selective kernel networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 510–519. [Google Scholar]

| Model | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | mAP50 (%) | mAPs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faster RCNN | 69.1 | 73.2 | 71.1 | 60.9 | 40.9 |

| YOLOv5 | 74.3 | 69.0 | 72.5 | 60.0 | 42.2 |

| YOLOX | 69.0 | 72.1 | 70.4 | 56.6 | 34.8 |

| YOLOv8 | 74.0 | 77.9 | 75.0 | 61.6 | 43.1 |

| YOLOv10 | 70.6 | 72.4 | 71.2 | 59.8 | 41.9 |

| YOLOv11 | 66.7 | 73.0 | 70.4 | 58.5 | 39.3 |

| TGDNet | 80.8 | 75.5 | 77.8 | 68.7 | 48.6 |

| Model | (img/s) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faster RCNN | 41.2 | 40.1 | 197.1 |

| YOLOv5 | 73.2 | 25.5 | 70.2 |

| YOLOX | 70.0 | 22.3 | 75.2 |

| YOLOv8 | 79.5 | 25.9 | 80.0 |

| YOLOv11 | 82.1 | 16.0 | 60.1 |

| TGDNet | 71.1 | 28.4 | 65.8 |

| Model | TGFE | TGD | BiPANet | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | mAP50 (%) | mAPs (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | (img/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | × | × | × | 73.9 | 56.1 | 63.5 | 61.6 | 41.7 | 21.8 | 75.2 | 78.1 |

| M1 | √ | × | × | 77.3 | 58.3 | 65.2 | 65.3 | 47.2 | 26.0 | 95.2 | 62.9 |

| M2 | √ | √ | × | 78.1 | 76.5 | 76.0 | 66.8 | 48.1 | 26.6 | 95.9 | 58.5 |

| TGDNet | √ | √ | √ | 80.8 | 75.5 | 77.8 | 68.7 | 48.6 | 26.1 | 65.8 | 71.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Tang, J. TGDNet: A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Defect Detection Method for Transparent Industrial Headlight Glass. Sensors 2025, 25, 7437. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247437

Zhang Z, Tang J. TGDNet: A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Defect Detection Method for Transparent Industrial Headlight Glass. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7437. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247437

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zefan, and Jin Tang. 2025. "TGDNet: A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Defect Detection Method for Transparent Industrial Headlight Glass" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7437. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247437

APA StyleZhang, Z., & Tang, J. (2025). TGDNet: A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Defect Detection Method for Transparent Industrial Headlight Glass. Sensors, 25(24), 7437. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247437