Adaptive Hoyer-L-Moment Envelope Spectrum: A Method for Robust Demodulation of Ship-Radiated Noise in Low-SNR Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A Hoyer-L-moment (HL) metric is proposed to evaluate the modulation intensity of individual spectral component from both sparsity and periodicity, without requiring prior knowledge.

- (2)

- A Golden Ratio Band Division (GRBD) method is proposed to adaptively divide the frequency spectrum and select the optimal integration bands. Based on the golden section search principle, GRBD efficiently partitions the frequency band and identifies the integration bands with the most intense modulation characteristics.

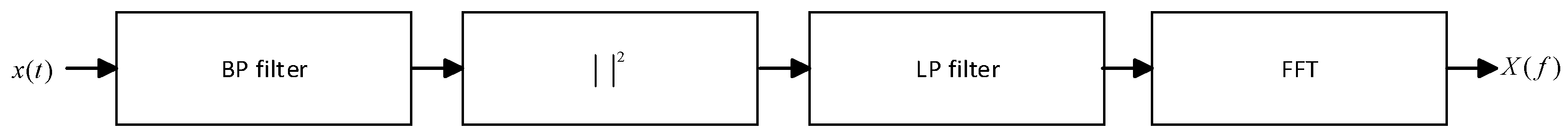

2. Cyclostationary Analysis

3. The Methodology of Adaptive Hoyer-L-Moment Envelope Spectrum

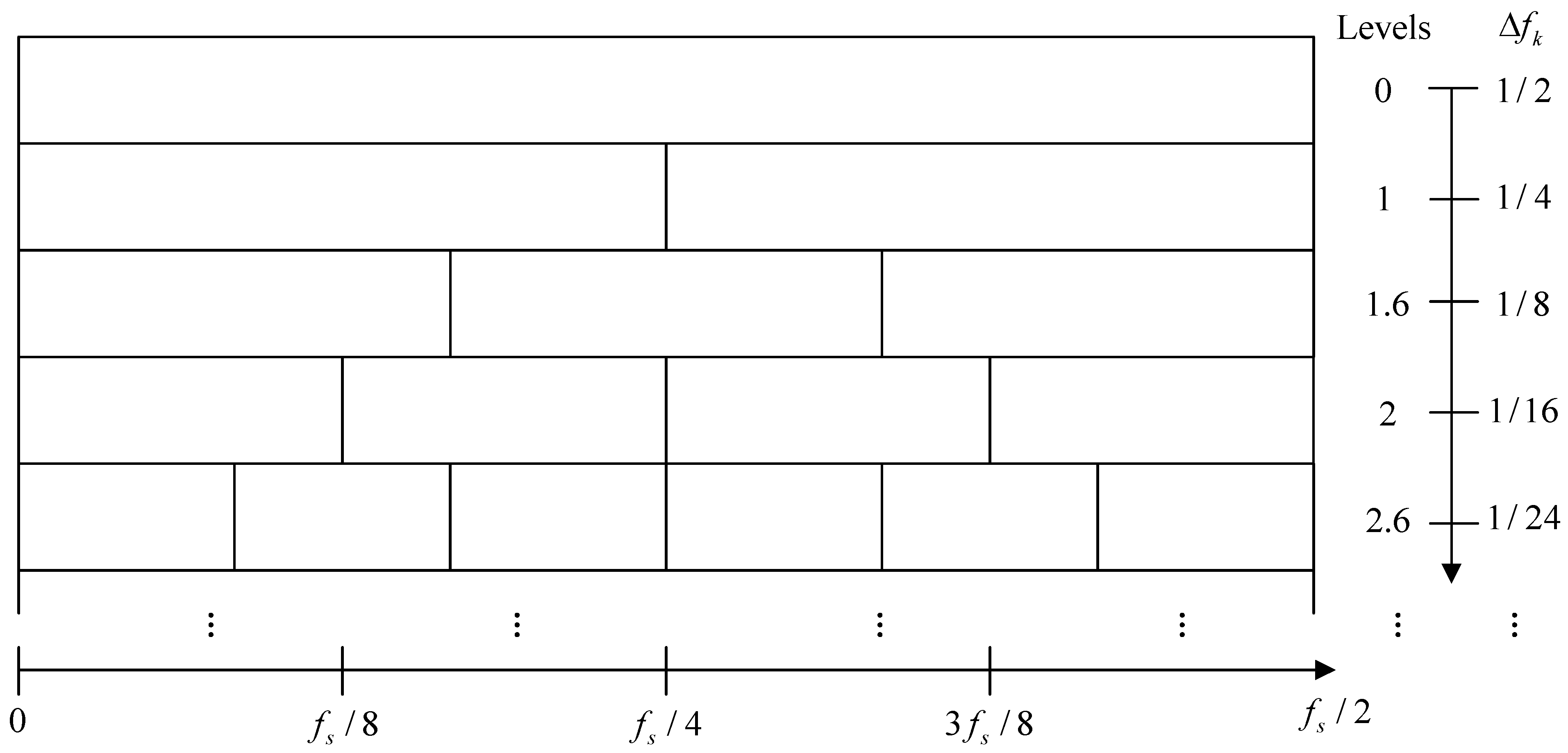

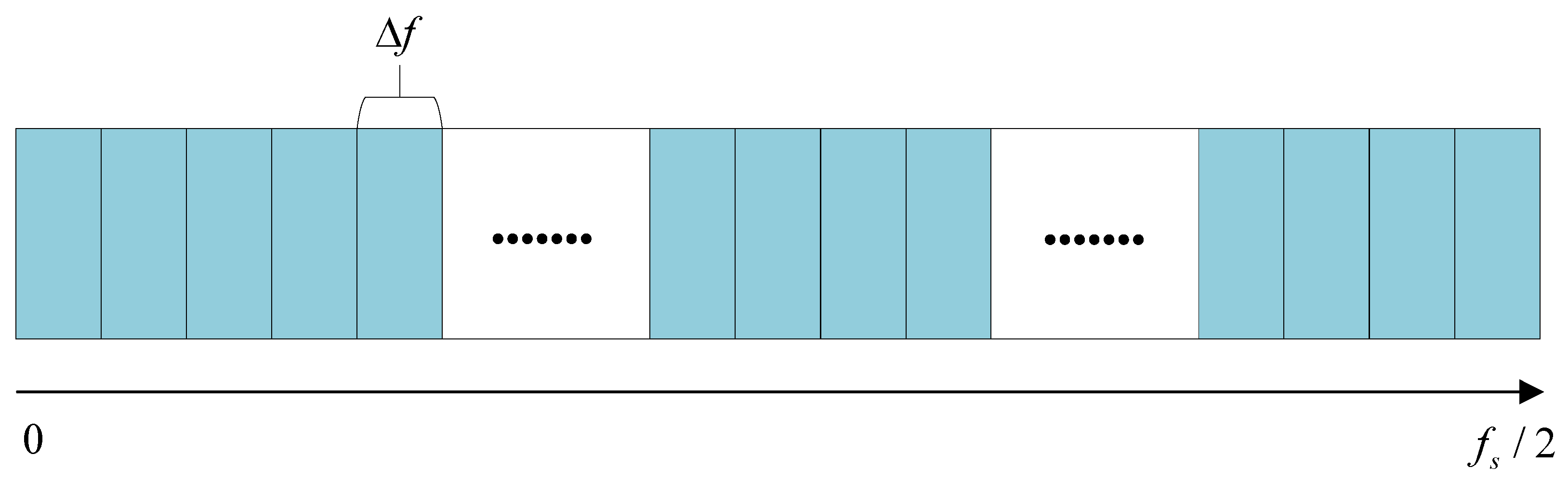

3.1. Golden Ratio Band Division

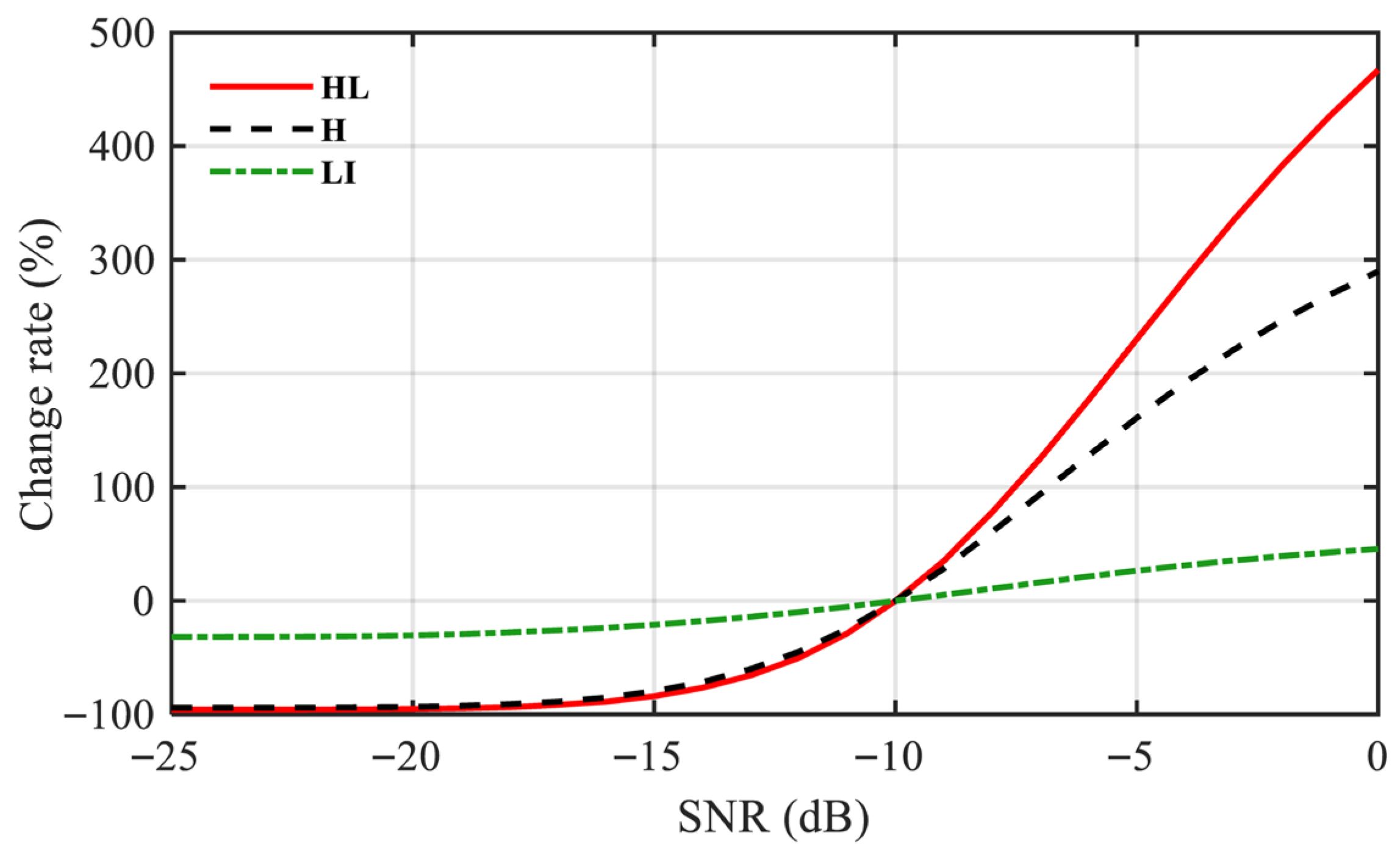

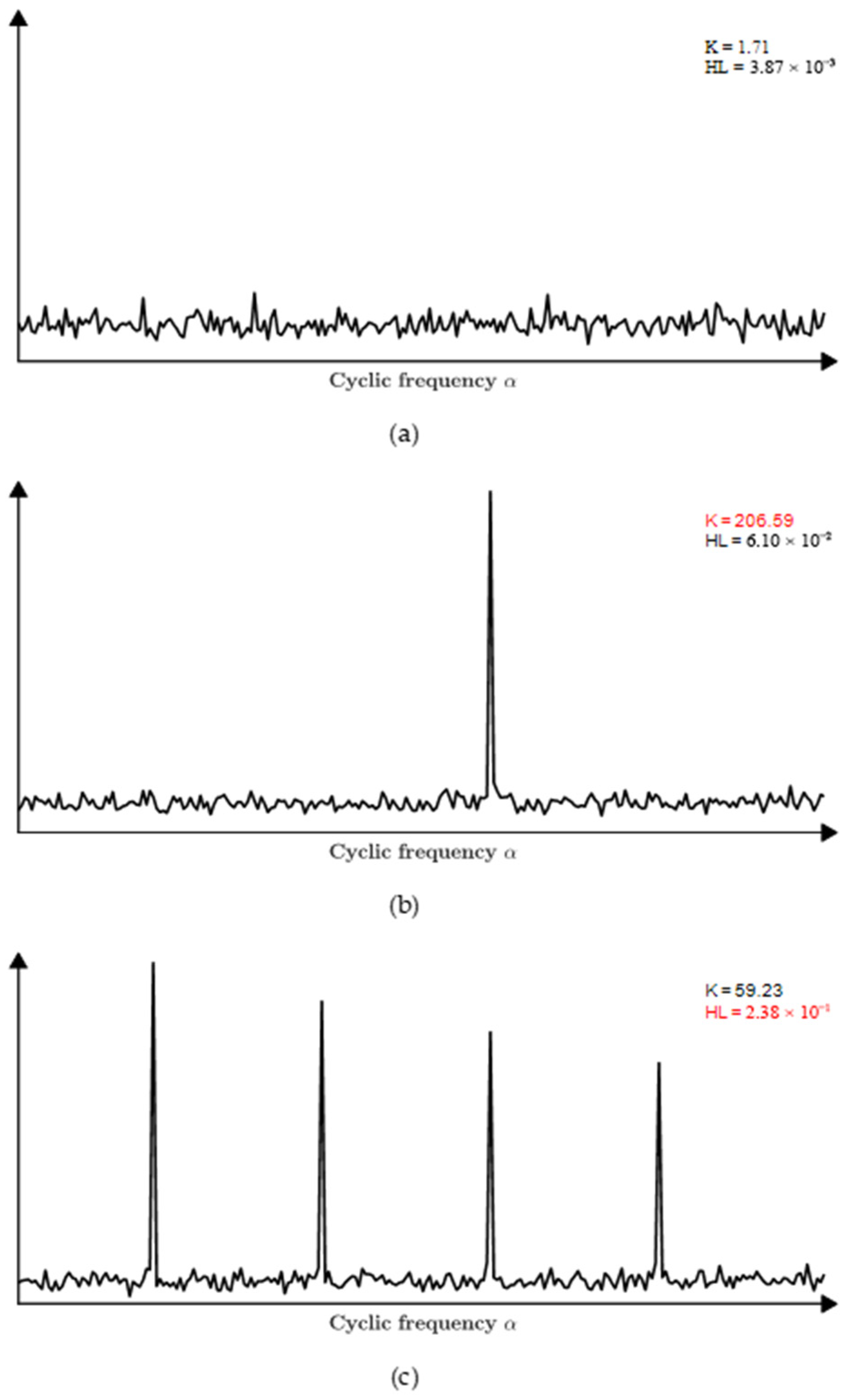

3.2. Hoyer-L-Moment Metric

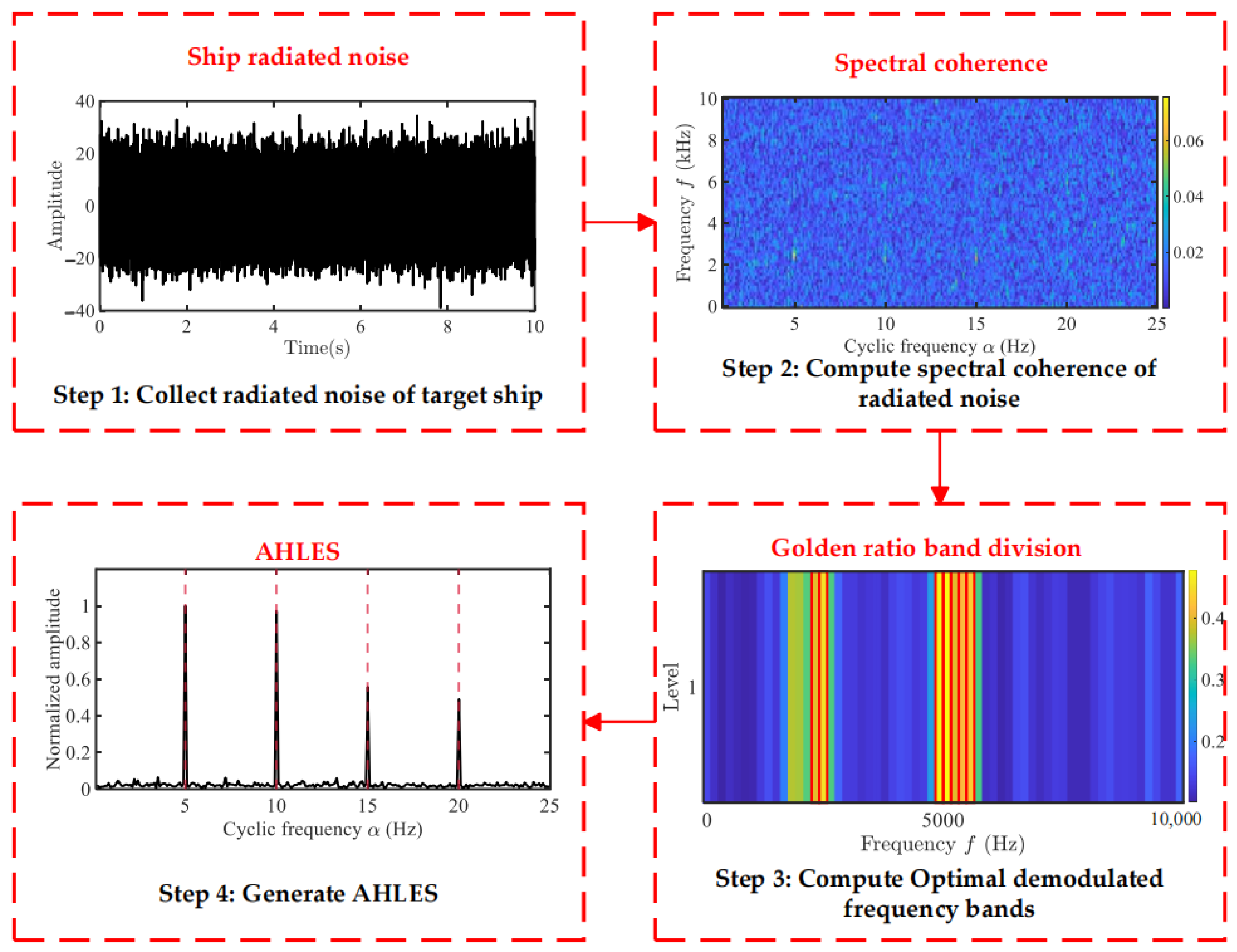

3.3. Modulation Feature-Extraction-Based AHLES

- (1)

- Acquire modulated signals from ship-radiated noise.

- (2)

- Using the fast SC algorithm [23], estimate the SCoh of the radiated noise by configuring an appropriate window length and a maximum cyclic frequency.

- (3)

- Use the GRBD structure to divide the demodulation frequency bands along the spectral frequency axis , obtaining a series of sub-band groups. Subsequently, a series of candidate EESs is constructed by integrating the SCoh magnitude over these spectrally partitioned sub-bands. Evaluate the richness of modulation information in each sub-band using the HL metric. Then, adaptively select the sub-bands using the golden section strategy.

- (4)

- Calculate the envelope spectrum:where denotes the adaptive Hoyer–L-moment envelope spectrum, N is the number of frequency bands in the sub-band , and represents the starting frequency of the sub-band .

4. Experimental Results and Performance

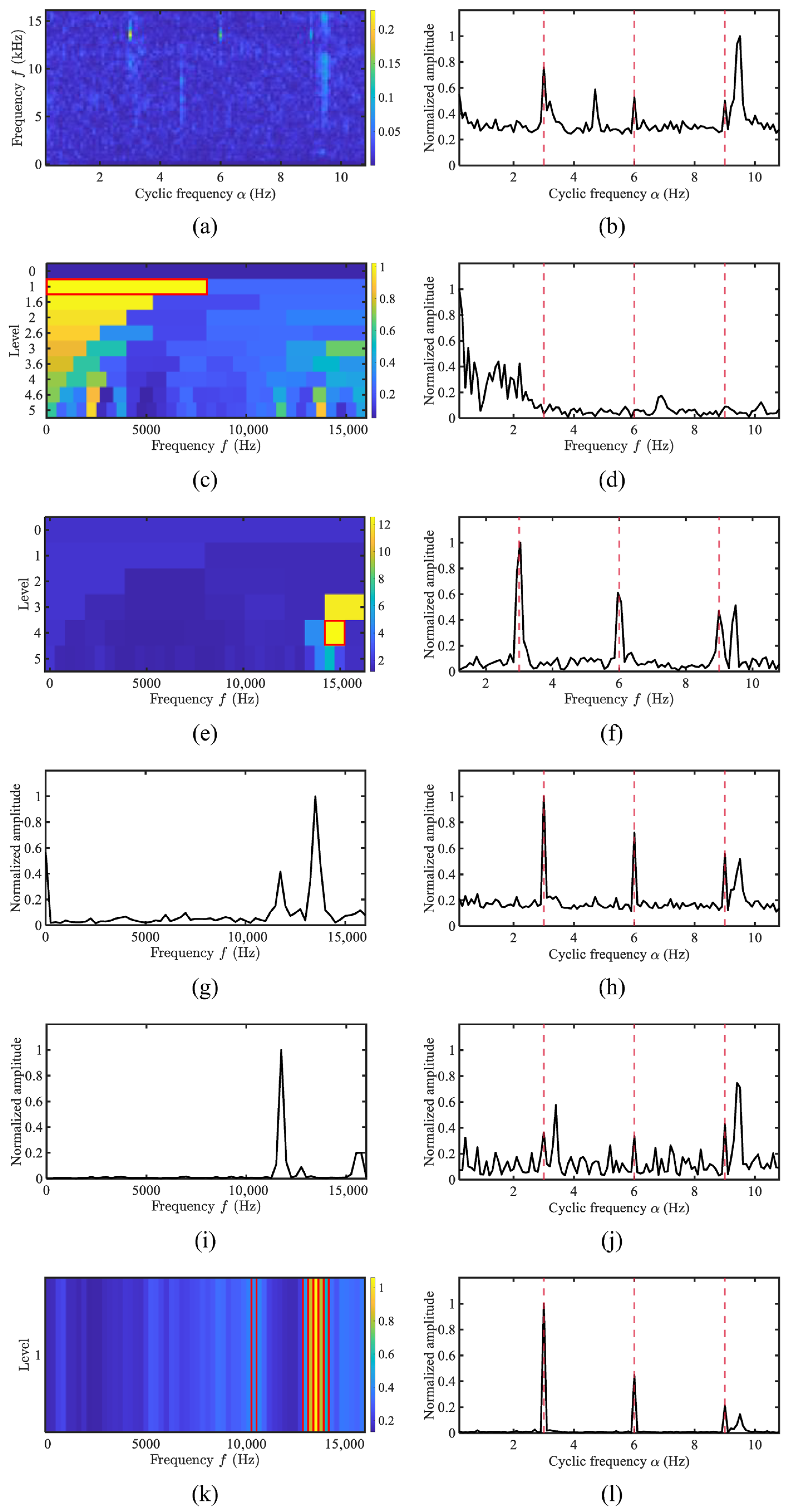

4.1. Simulation Analysis

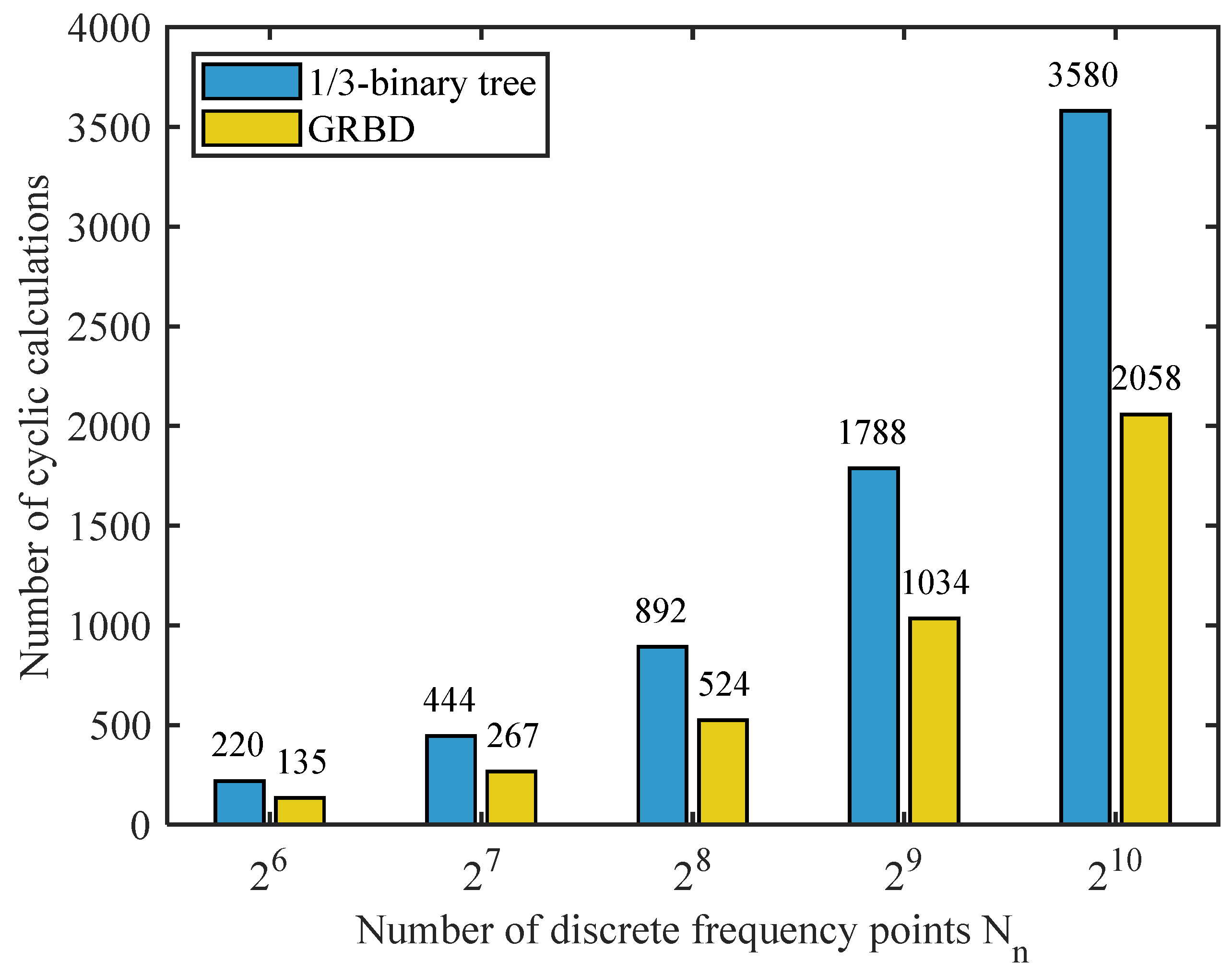

4.2. Calculation Cost

4.3. Performance Evaluation Using Monte Carlo Simulations

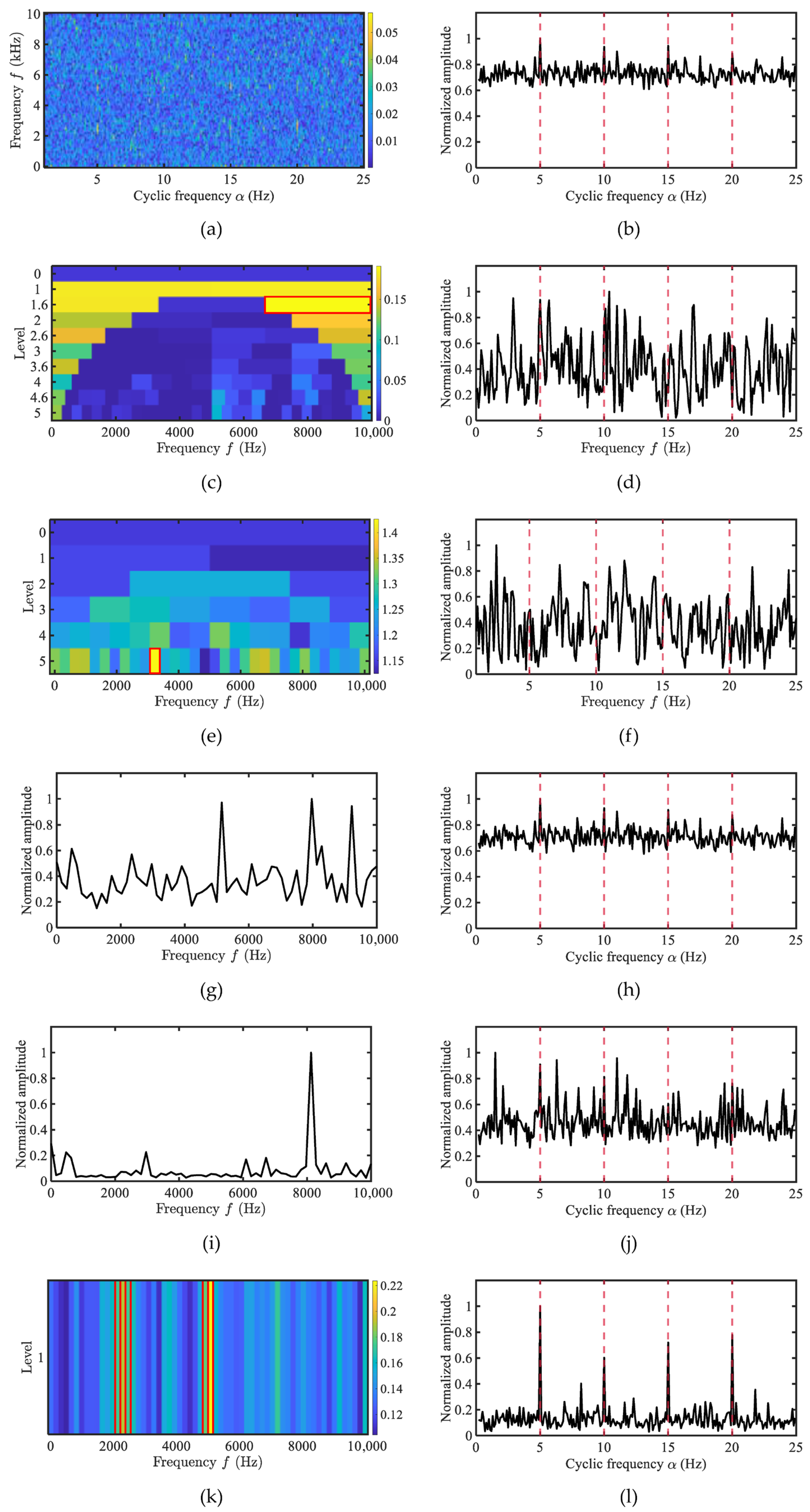

4.4. Performance Evaluation Using Merchant Ship Data

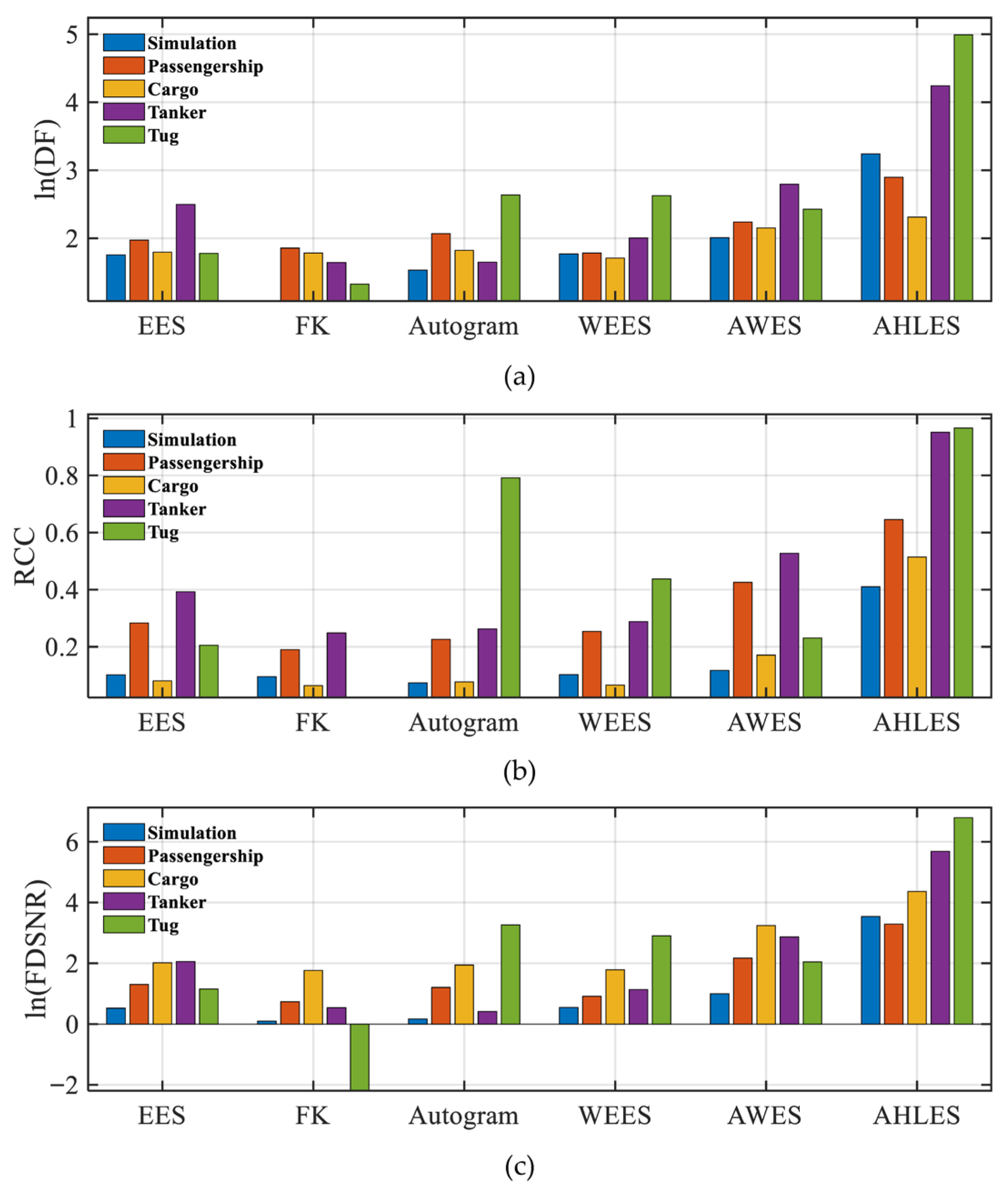

4.5. Quantitative Comparison of the Proposed Method and Typical Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siderius, M.; Gebbie, J. Environmental information content of ocean ambient noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 146, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourens, J.; Coetzer, M. Detection of mechanical ship features from underwater acoustic sound. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Dallas, TX, USA, 6–9 April 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtsev, A.A.; Luginets, K.P.; Mashoshin, A.I. Amplitude modulation of underwater noise produced by seagoing vessels. Acoust. Phys. 2003, 49, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, B.; Anoop, M.; Vijayan Pillai, S.; Sooraj, K.A. Performance Evaluation of the DEMON Processor for Sonar. In Proceedings of the IEEE Region 10 Symposium, Mumbai, India, 1–3 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, D.; Antoni, J.; Brown, G.; Emslie, R. Cyclostationarity for passive underwater detection of propeller craft: A development of DEMON processing. In Proceedings of the Acoustics and Sustainability, Geelong, Australia, 24–26 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pollara, A.; Sutin, A.; Salloum, H. Improvement of the Detection of Envelope Modulation on Noise (DEMON) and its application to small boats. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, Monterey, CA, USA, 19–23 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stinco, P.; Tesei, A.; Dreo, R.; Micheli, M. Detection of envelope modulation and direction of arrival estimation of multiple noise sources with an acoustic vector sensor. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2021, 149, 1596–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, J. Fast computation of the kurtogram for the detection of transient faults. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2007, 21, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, J. The infogram: Entropic evidence of the signature of repetitive transients. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 74, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshrefzadeh, A.; Fasana, A. The Autogram: An effective approach for selecting the optimal demodulation band in rolling element bearings diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 105, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.A. Introduction to random processes with applications to signals and systems. Automatica 1988, 24, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W. Measurement of spectral correlation. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1986, 34, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustany, R.; Antoni, J. A subspace method for the blind extraction of a cyclostationary source: Application to rolling element bearing diagnostics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2005, 19, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesani, P.; Antoni, J. CS2 analysis in presence of non-Gaussian background noise—Effect on traditional estimators and resilience of log-envelope indicators. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 90, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, J. Cyclic spectral analysis of rolling-element bearing signals: Facts and fictions. J. Sound Vib. 2007, 304, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, I.; Glossiotis, G. Cyclostationary Analysis of Rolling-Element Bearing Vibration Signals. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 248, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Enhancement of decomposed spectral coherence using sparse nonnegative matrix factorization. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 157, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Smith, W.A.; Borghesani, P.; Randall, R.B.; Peng, Z. Use of cyclostationary properties of vibration signals to identify gear wear mechanisms and track wear evolution. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 150, 107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, R.B.; Antoni, J.; Chobsaard, S. A comparison of cyclostationary and envelope analysis in the diagnostics of rolling element bearings. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Istanbul, Turkey, 5–9 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, R.B.; Antoni, J.; Chobsaard, S. The Relationship Between Spectral Correlation and Envelope Analysis in the Diagnostics of Bearing Faults and Other Cyclostationary Machine Signals. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2001, 15, 945–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustany, R.; Antoni, J. Cyclic Spectral Analysis from the Averaged Cyclic Periodogram. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2005, 38, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, J. Cyclic spectral analysis in practice. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2007, 21, 597–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, J.; Xin, G.; Hamzaoui, N. Fast computation of the spectral correlation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 92, 248–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesani, P.; Antoni, J. A faster algorithm for the calculation of the fast spectral correlation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 111, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Kou, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tsui, K. A simple and fast guideline for generating enhanced/squared envelope spectra from spectral coherence for bearing fault diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 122, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, A.; Qi, J.; Smith, W.A.; Sarazin, M.; Randall, R.B.; Janssens, K.; Gryllias, K. Bearing diagnostics under strong electromagnetic interference based on Integrated Spectral Coherence. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 140, 106673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, A.; Smith, W.A.; Randall, R.B.; Antoni, J.; Gryllias, K. Improved Envelope Spectrum via Feature Optimisation-gram (IESFOgram): A novel tool for rolling element bearing diagnostics under non-stationary operating conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 144, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. A weighting function for improvement of spectral coherence based envelope spectrum. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 160, 107929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Wu, K.; Wang, H.; Cao, L.; Huang, B.; Wu, D.; Antoni, J. Adaptive Weighted Envelope Spectrum: A robust spectral quantity for passive acoustic detection of underwater propeller based on spectral coherence. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 212, 111265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wu, P.; Wu, D. A periodic-modulation-oriented noise resistant correlation method for industrial fault diagnostics of rotating machinery under the circumstances of limited system signal availability. ISA Trans. 2024, 151, 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gu, F.; Mei, G. Optimal frequency band selection using blind and targeted features for spectral coherence-based bearing diagnostics: A comparative study. ISA Trans. 2022, 127, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghesani, P.; Pennacchi, P.; Chatterton, S. The relationship between kurtosis- and envelope-based indexes for the diagnostic of rolling element bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2014, 43, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Jiangbin, Z.; Ali, S.; Iqbal, M.; Masood, Z.; Hamid, U. DeepShip: An underwater acoustic benchmark dataset and a separable convolution based autoencoder for classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 183, 115270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | EES | FK | Autogram | WEES | AWES | AHLES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation time (s) | 0.090924 | 0.071979 | 2.063884 | 0.100143 | 0.091279 | 0.125408 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Wang, Q.; Du, S. Adaptive Hoyer-L-Moment Envelope Spectrum: A Method for Robust Demodulation of Ship-Radiated Noise in Low-SNR Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 7434. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247434

Zhang R, Wang Q, Du S. Adaptive Hoyer-L-Moment Envelope Spectrum: A Method for Robust Demodulation of Ship-Radiated Noise in Low-SNR Environments. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7434. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247434

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ruizhe, Qingcui Wang, and Shuanping Du. 2025. "Adaptive Hoyer-L-Moment Envelope Spectrum: A Method for Robust Demodulation of Ship-Radiated Noise in Low-SNR Environments" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7434. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247434

APA StyleZhang, R., Wang, Q., & Du, S. (2025). Adaptive Hoyer-L-Moment Envelope Spectrum: A Method for Robust Demodulation of Ship-Radiated Noise in Low-SNR Environments. Sensors, 25(24), 7434. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247434