HyMambaNet: Efficient Remote Sensing Water Extraction Method Combining State Space Modeling and Multi-Scale Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

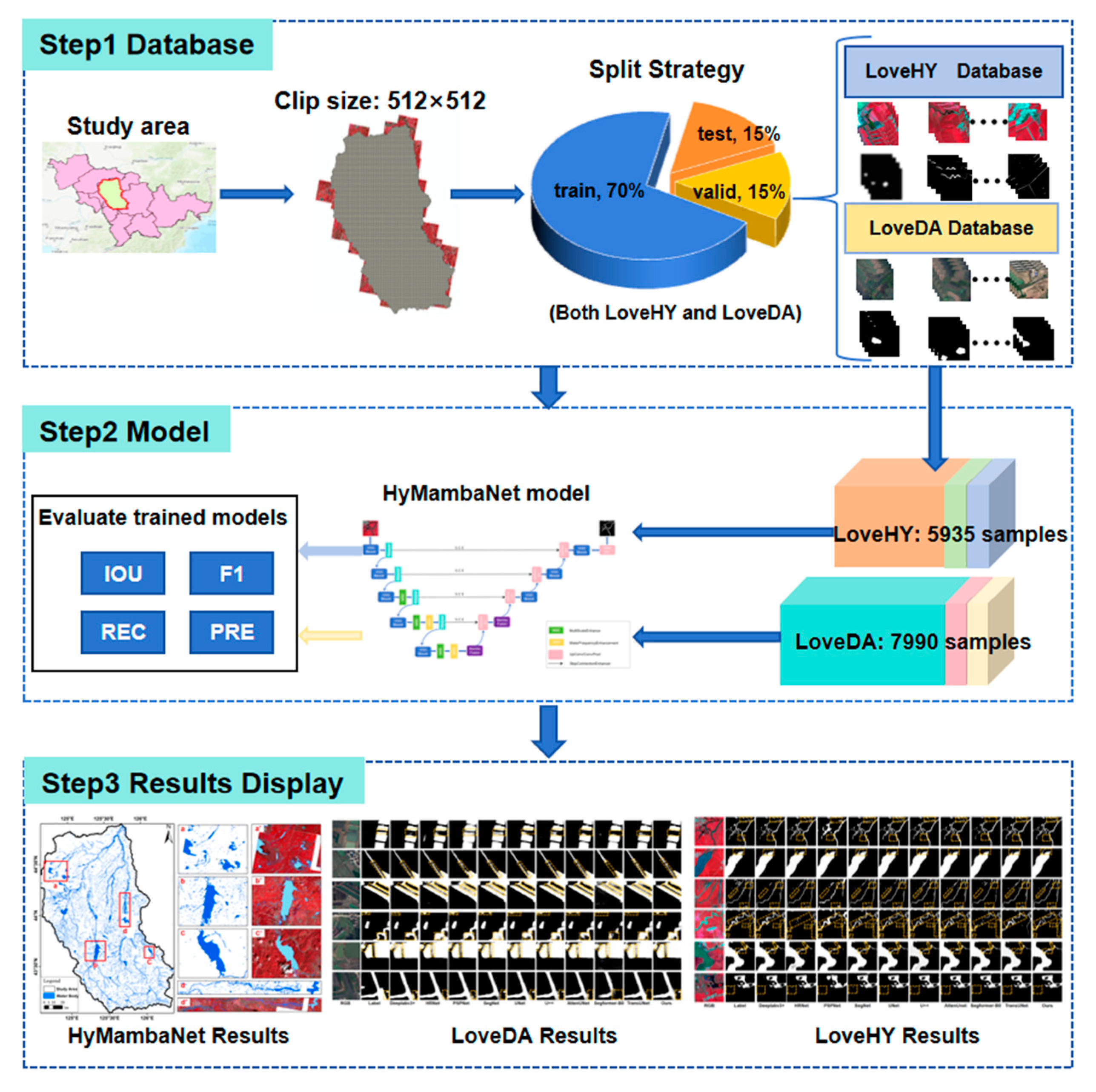

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.1.1. LoveHY Dataset

2.1.2. LoveDA Dataset

2.2. Overall Framework of HyMambaNet

2.3. Key Components of the Network

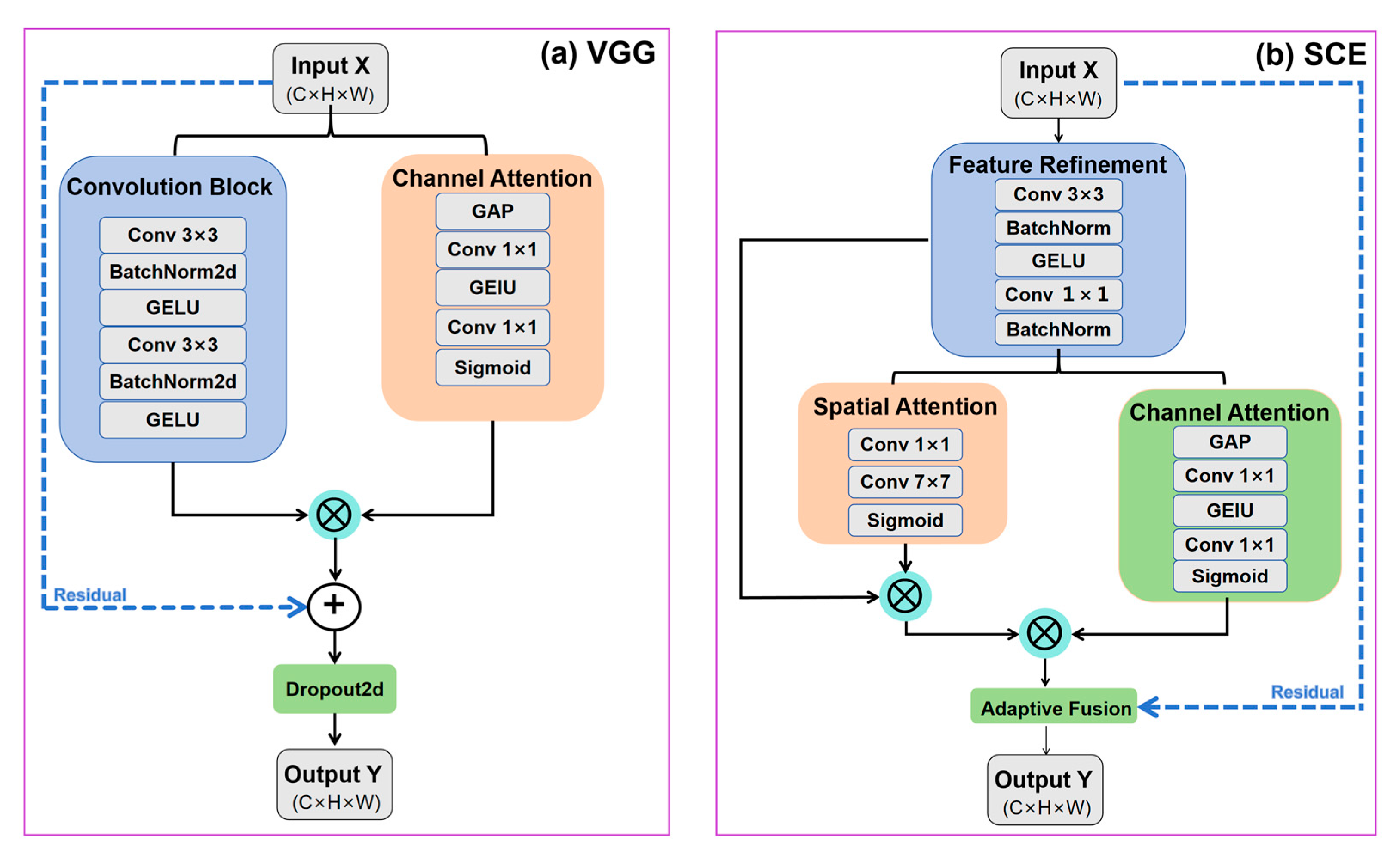

2.3.1. Enhanced VGGBlock

- is the input feature map, with input channels and spatial size H × W.

- (·) denotes a 3 × 3 convolution with padding = 1 to preserve spatial resolution.

- BN(·) denotes batch normalization.

- GELU(·) denotes the Gaussian Error Linear Unit activation.

- F1 and F2 are intermediate feature maps with channels.

- Dropout(F2) refers to spatial dropout applied to the enhanced feature map.

- ensures that the residual branch aligns with the enhanced branch in channel dimension.

- y is the final output of the enhanced VGGBlock.

2.3.2. Skip Connection Enhancer (SCE)

- is the refined encoder feature map.

- (·) denotes a 1 × 1 convolution for channel reduction and feature mixing.

- (·) denotes a large-kernel convolution for capturing long-range spatial context.

- (·) is the sigmoid activation.

- is the resulting spatial attention map.

- is the attention-enhanced feature after spatial and channel attention.

- is the original skip-connection feature.

- α∈[0, 1] is a learnable weight initialized to 0.5.

- Y is the output feature of the SCE module.

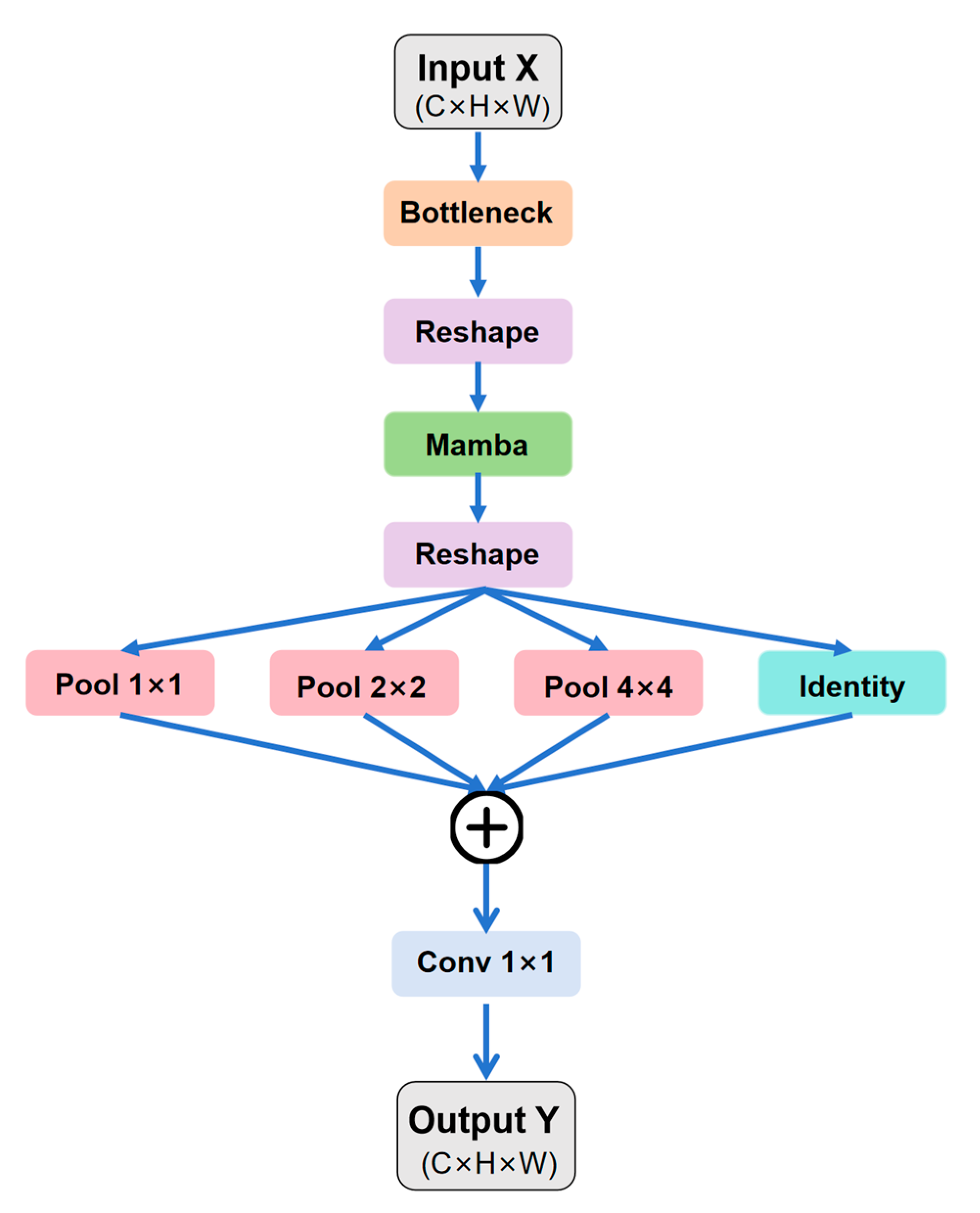

2.3.3. MambaFusion

- denotes the hidden state.

- and represent the input and output sequences.

- A, B, and C are the system matrices. Unlike conventional SSMs with fixed parameters, Mamba dynamically adapts these matrices using a selective scanning mechanism (S6), enabling context-aware parameter evolution based on input features.

- is the global-context feature modeled by the Mamba branch.

- is the multi-scale pooled local feature.

- is the residual feature ensuring boundary preservation.

- λ is a learnable scalar balancing global and local contributions.

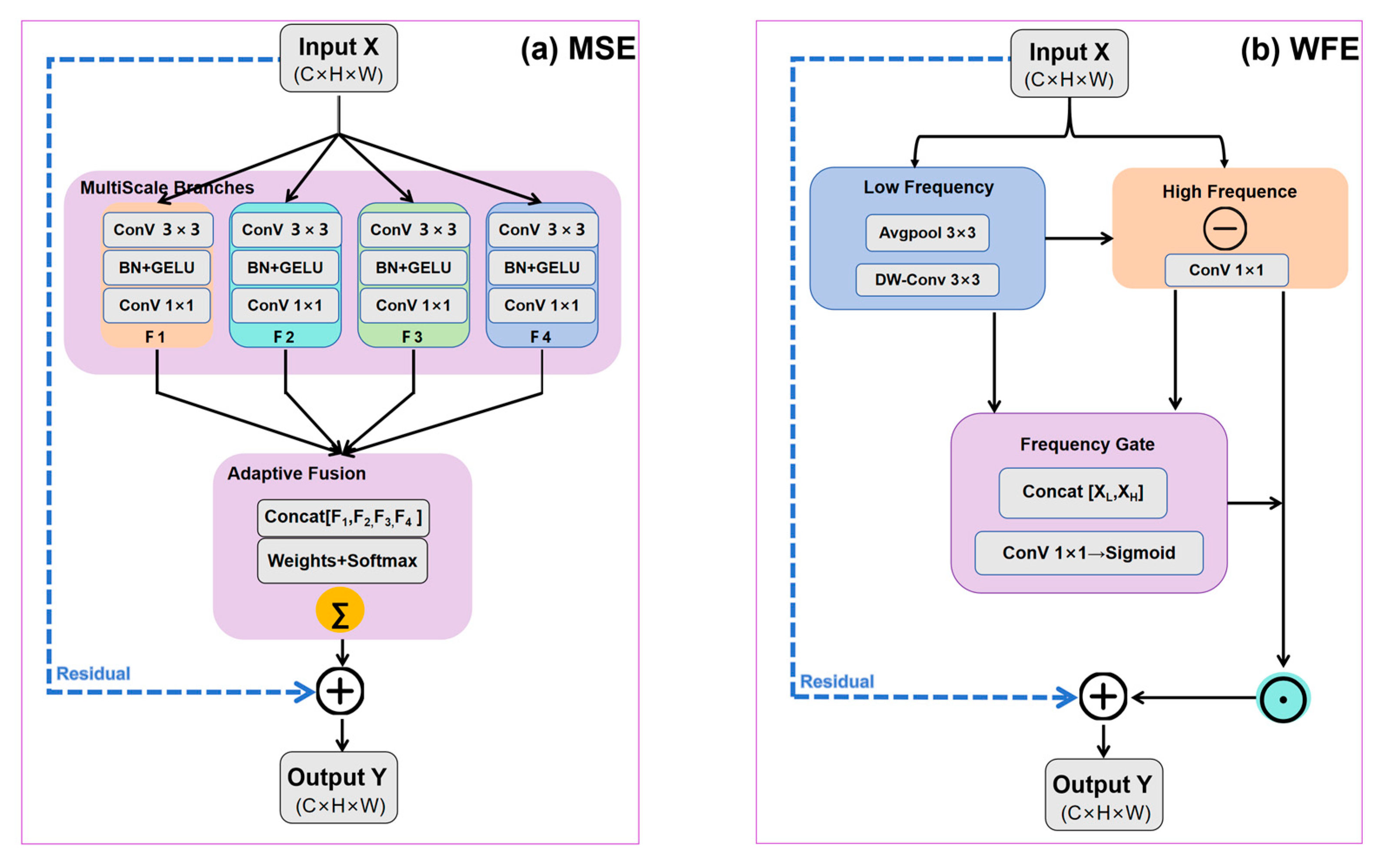

2.3.4. Multi-Scale Enhancement (MSE)

- F is the input feature map.

- (⋅) denotes a 3 × 3 dilated convolution with dilation rate.

- D is the number of dilation branches.

- is the feature extracted at scale.

- is the learnable weight for scale.

- The term is a softmax ensuring normalized scale weights.

- provides a residual connection for stability.

- is the fused multi-scale feature.

2.3.5. Water Frequency Enhancement (WFE)

- denotes depthwise convolution capturing low-frequency components.

- extracts fine-grained high-frequency details.

- and represent low- and high-frequency features, respectively.

- Concat[·] denotes channel-wise concatenation.

- Conv(·) is a convolution that produces the gating feature.

- σ(·) is the sigmoid activation controlling enhancement strength.

- denotes element-wise multiplication.

- is the frequency-enhanced output feature.

2.4. Experimental Setup

2.4.1. Water Body Extraction Workflow

2.4.2. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

2.4.3. Computational Complexity and Efficiency Analysis

- (1)

- Theoretical Complexity Analysis

- (2)

- Empirical Efficiency Comparison

2.5. Model Performance Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

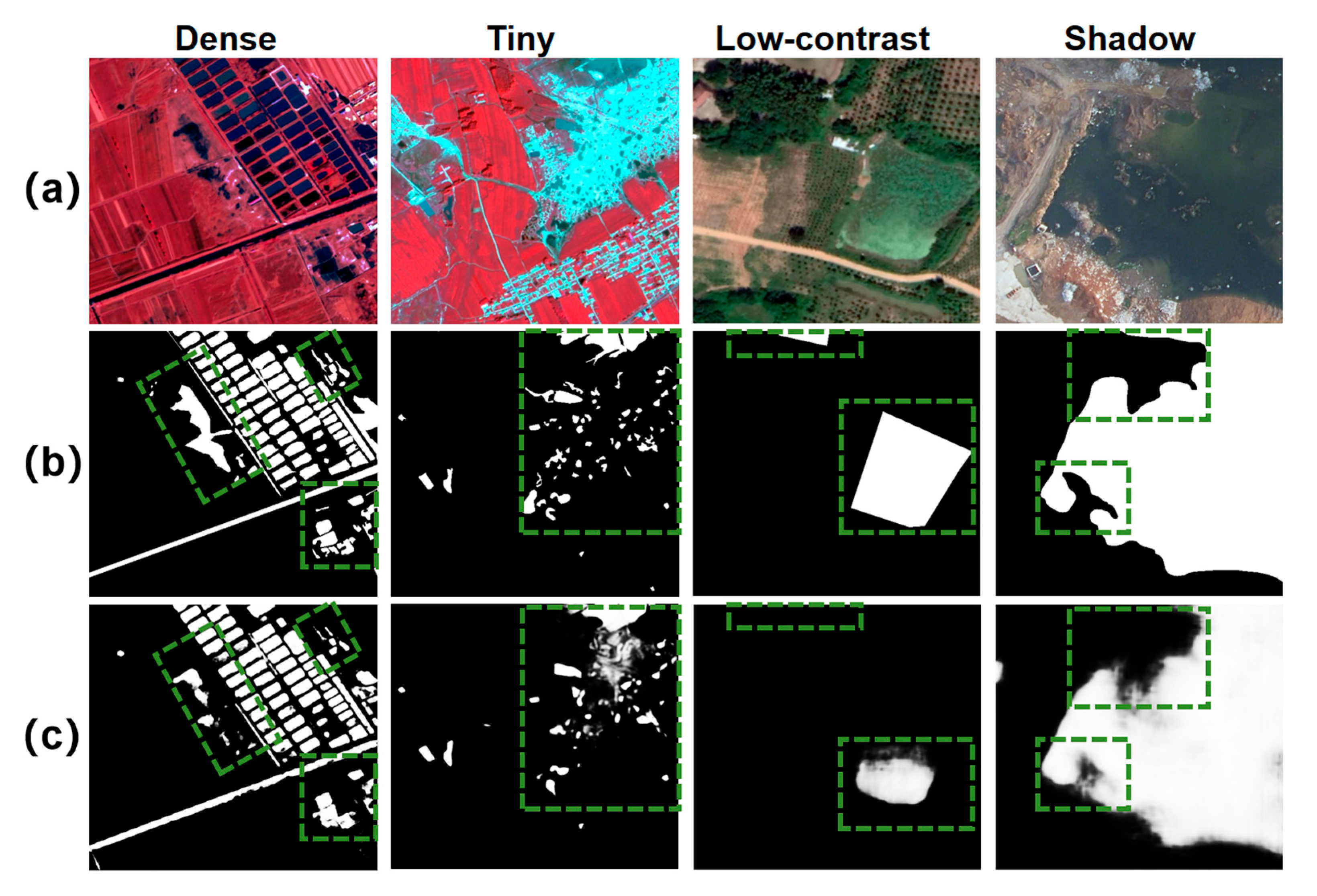

3.1. Visualization of Segmentation Results for Water Bodies with Different Scales and Morphologies

3.2. Ablation Study

3.3. Comparative Study on the LoveHY Dataset

3.4. Comparative Study on the LoveDA Dataset

3.5. Failure Cases and Error Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of Key HyMambaNet Modules to Water Body Segmentation Performance

4.2. Performance and Generalization Analysis Across Different Datasets

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, P.; Zou, S.; Li, J.; Ju, H.; Zhang, J. Advancing Water Quality Management: Harnessing the Synergy of Remote Sensing, Process-Based Models, and Machine Learning to Enhance Monitoring and Prediction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, H.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, S. Dynamic Monitoring of Poyang Lake Water Area and Storage Changes from 2002 to 2022 via Remote Sensing and Satellite Gravimetry Techniques. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; Masek, J.G.; Cohen, W.B.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E. Opening the archive: How free data has enabled the science and monitoring promise of Landsat. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaywant, S.A.; Arif, K.M. Remote Sensing Techniques for Water Quality Monitoring: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijeesh, T.V.; Narasimhamurthy, K.N. Surface water detection and delineation using remote sensing images: A review of methods and algorithms. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, K.; Ahmad, A.; Selamat, A.; Hazini, S. Water Feature Extraction and Change Detection Using Multitemporal Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4173–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnizova, A.; Siemens, J.; Langer, M.; Boike, J. Small ponds with major impact: The relevance of ponds and lakes in permafrost landscapes to carbon dioxide emissions. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2012, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.C.; Falcão, A.P.; Oliveira, R.P.d. Using Sentinel Imagery for Mapping and Monitoring Small Surface Water Bodies. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoepers, T.R.; Leithold, J.; Monteiro, M.M.; Corzo Perez, G.A.; Scapulatempo Fernandes, C.V.; Zevenbergen, C.; Costa Dos Santos, D. An integrated approach to decision-making variables on urban water systems using an urban water use (UWU) decision-support tool. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakati, S.S.; Shoko, C.; Dube, T. Integrated flood modelling and risk assessment in urban areas: A review on applications, strengths, limitations and future research directions. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Zhang, L.; Ury, E.A.; Li, S.; Xia, B. Restoring small water bodies to improve lake and river water quality in China. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, J. A method for extracting small water bodies based on DEM and remote sensing images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisa, G.L.; Meilby, H.; Fensholt, R.; Proud, S.R. Automated Water Extraction Index: A new technique for surface water mapping using Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, D.; Di Martino, G.; Di Simone, A.; Imperatore, P. Flood Detection with SAR: A Review of Techniques and Datasets. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. The use of the normalized difference water index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D. Water body extraction from multi spectral image by spectral pattern analysis. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, XXXIX-B8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ling, F.; Ghassemian, N.; Zhang, C. A robust Multi-Band Water Index (MBWI) for automated extraction of surface water from Landsat 8 OLI imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 68, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhang, L.; Wylie, B. Analysis of dynamic thresholds for the Normalized Difference Water Index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kong, J.; Hu, H.; Du, Y.; Gao, M.; Chen, F. A Review of Remote Sensing for Water Quality Retrieval: Progress and Challenges. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; He, G.; Gao, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M. OCNet-Based Water Body Extraction from Remote Sensing Images. Water 2023, 15, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, B.; Manocha, A. Small water body extraction in remote sensing with enhanced CNN architecture. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 169, 112544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer, E.; Long, J.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Fang, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ghamisi, P. NFANet: A novel method for weakly supervised water extraction from high-resolution remote-sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5617114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X. Lightweight deep neural network method for water body extraction from high-resolution remote sensing images with multisensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wei, Q.; Luo, X.; Xie, Y.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; et al. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 97, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual attention network for scene segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3141–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze and excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Yi, J.; Li, S.; Wang, R.; Wu, Y. Agricultural surface water extraction in environmental remote sensing: A novel semantic segmentation model emphasizing contextual information enhancement and foreground detail attention. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 129110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, B.; Deng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Mu, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Deep high-resolution representation learning for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 3349–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Yu, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, K. DenseASPP for semantic segmentation in street scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3684–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.; et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence to sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6881–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I. Generating long sequences with sparse transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.10509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Building Extraction from Remote Sensing Images with Sparse Token Transformers. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Geng, G.; Zhou, P.; Yan, L.; Zhou, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. A Mamba based vision transformer for fine grained image segmentation of mural figures. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. Vmamba: Visual State Space Model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 103031–103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, F.; Wang, B. U-mamba: Enhancing long-range dependency for biomedical image segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba UNet for medical image segmentation. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2025, 21, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Quan, C.; Zhao, T.; Huo, W.; Huang, Y. Mamba-STFM: A Mamba-Based Spatiotemporal Fusion Method for Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; He, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote Sensing Change Detection with Spatiotemporal State Space Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5626720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Rsmamba: Remote Sensing Image Classification with State Space Model. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6006705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xing, Z.; Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; Xie, Q. SF-Mamba: A Semantic-Flow Foreground-Aware Mamba for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Multimed. 2025, 32, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dan, J.; Lu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X. CM-UNet: Hybrid CNN-Mamba UNet for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P.; Bai, L.; Ouyang, W. RS-Mamba for Large Remote Sensing Image Dense Prediction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5633314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Tao, L.; Li, Y. CM-UNet++: A Multi-Level Information Optimized Network for Urban Water Body Extraction from High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, A.; Lu, X.; Zhong, Y. LoveDA: A Remote Sensing Land-Cover Dataset for Domain Adaptive Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.08733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Skip Connection Enhancerne Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6230–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Kamnitsas, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Glocker, B.; Rueckert, D. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 12077–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, M.; Xia, M.; Lin, H. Multi-Scale Feature Aggregation Network for Water Area Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Han, K.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, W.; Gao, X. SPFDNet: Water Extraction Method Based on Spatial Partition and Feature Decoupling. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Params (M) | GFLOPS | Inference Time (ms) | Input Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Fusion | 28.6 | 64.3 | 32.7 | 512 × 512 |

| MambaFusion | 17.9 | 27.4 | 14.8 | 512 × 512 |

| Experiment ID | Module Combination | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | IoU (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0 | UNet | 81.18 | 82.32 | 67.33 | 81.75 |

| A1 | A0 + VGGBlock | 83.45 | 81.28 | 68.92 | 82.35 |

| A2 | A1 + MSE | 82.91 | 85.67 | 70.15 | 84.26 |

| A3 | A2 + SCE | 85.13 | 84.93 | 71.84 | 85.02 |

| A4 | A3 + WFE | 84.76 | 88.45 | 73.29 | 86.58 |

| A5 | A4 + MambaFusion | 86.21 | 89.73 | 74.18 | 87.94 |

| A6 | Full Model | 86.88 | 90.97 | 74.82 | 88.87 |

| Methods | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | IoU (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deeplabv3+ | 84.19 | 84.55 | 72.59 | 84.37 |

| HRNet | 80.25 | 83.28 | 66.58 | 81.74 |

| PSPNet | 67.79 | 78.48 | 58.84 | 72.77 |

| SegNet | 80.05 | 79.85 | 66.59 | 79.95 |

| UNet | 81.18 | 82.32 | 67.33 | 81.75 |

| U++ | 81.22 | 82.49 | 68.35 | 81.85 |

| AttenUNet | 81.97 | 84.08 | 69.66 | 83.02 |

| Segformer-B0 | 70.08 | 76.61 | 57.35 | 73.19 |

| TransUNet | 84.14 | 90.56 | 71.35 | 87.26 |

| Ours | 86.88 | 90.97 | 74.82 * | 88.87 * |

| Methods | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | IoU (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deeplabv3+ | 86.79 | 90.21 | 80.07 | 88.47 |

| HRNet | 86.35 | 86.07 | 76.72 | 86.21 |

| PSPNet | 85.31 | 90.00 | 78.36 | 87.61 |

| SegNet | 85.64 | 86.20 | 75.92 | 85.92 |

| UNet | 86.42 | 87.33 | 77.12 | 86.87 |

| U++ | 86.56 | 87.38 | 77.09 | 86.97 |

| AttenUNet | 86.02 | 91.51 | 77.10 | 88.68 |

| Segformer-B0 | 81.55 | 82.59 | 70.64 | 82.09 |

| TransUNet | 85.99 | 89.94 | 78.75 | 87.91 |

| Ours | 88.29 | 91.79 | 81.30 * | 89.99 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Mu, G.; Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, S. HyMambaNet: Efficient Remote Sensing Water Extraction Method Combining State Space Modeling and Multi-Scale Features. Sensors 2025, 25, 7414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247414

Liu H, Mu G, Li K, Zhang H, Sun Y, Sun H, Li S. HyMambaNet: Efficient Remote Sensing Water Extraction Method Combining State Space Modeling and Multi-Scale Features. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247414

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Handan, Guangyi Mu, Kai Li, Haowei Zhang, Yibo Sun, Hongqing Sun, and Sijia Li. 2025. "HyMambaNet: Efficient Remote Sensing Water Extraction Method Combining State Space Modeling and Multi-Scale Features" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247414

APA StyleLiu, H., Mu, G., Li, K., Zhang, H., Sun, Y., Sun, H., & Li, S. (2025). HyMambaNet: Efficient Remote Sensing Water Extraction Method Combining State Space Modeling and Multi-Scale Features. Sensors, 25(24), 7414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247414