Evaluating the Impact of Aggregation Operators on Fuzzy Signatures for Robot Path Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- It presents the first systematic application of fuzzy signatures (FSigs) as the primary environment representation data structure specifically for the mobile robot path planning task.

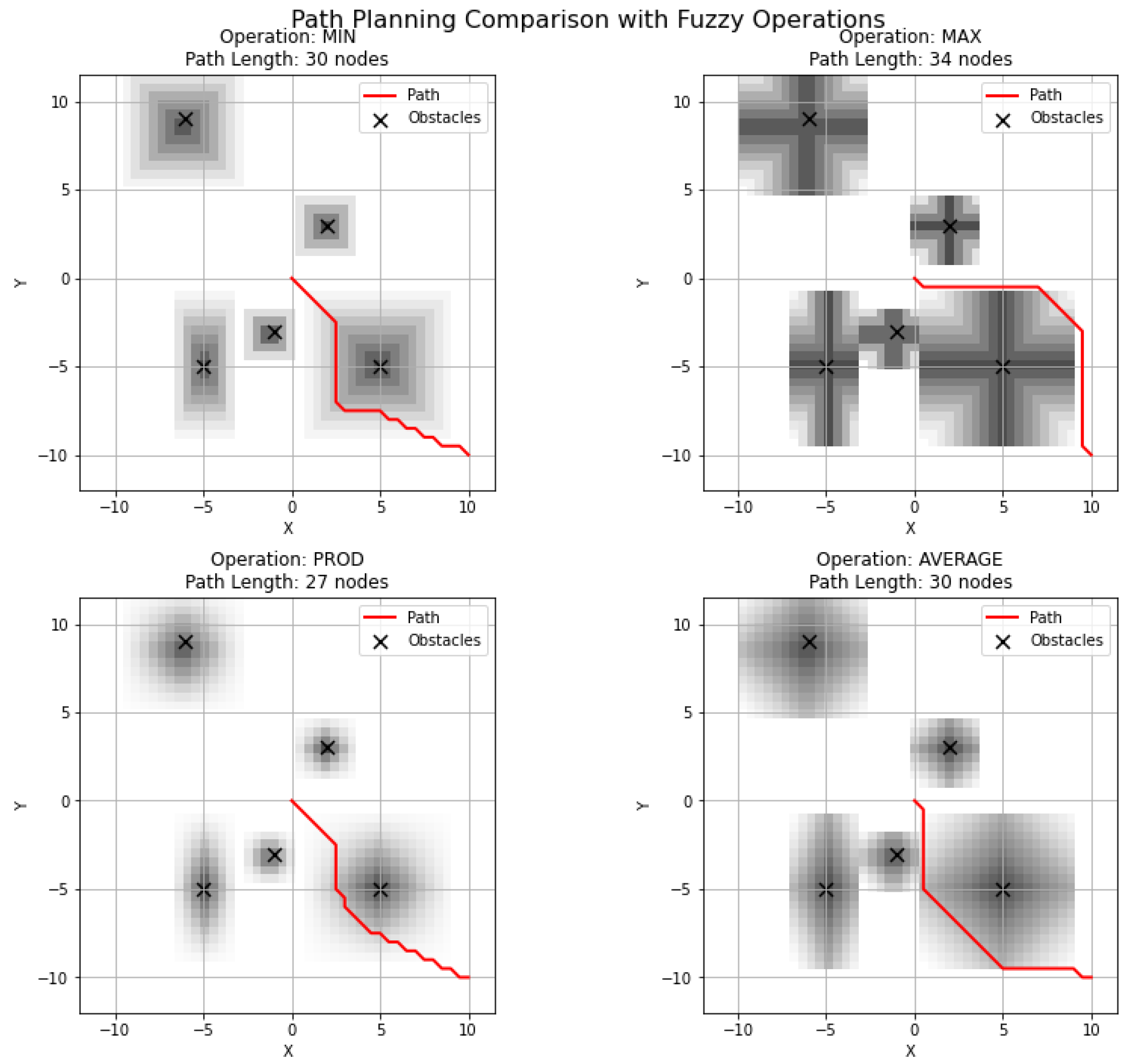

- It provides a comprehensive empirical analysis comparing the effects of four fundamental aggregation operators (minimum, maximum, algebraic product and arithmetic mean) on the efficiency of the FSigs-based system.

- It quantifies the impact of the chosen aggregation operator on key performance metrics, namely the resulting path length and the total computational execution time, offering evidence-based guidance for designing intelligent navigation systems. This work is the first empirical comparison of fuzzy aggregation operators specifically tailored for fuzzy signature-based mobile robot path planning.

2. Related Works

2.1. Application of Fuzzy Signatures and Aggregation Operators

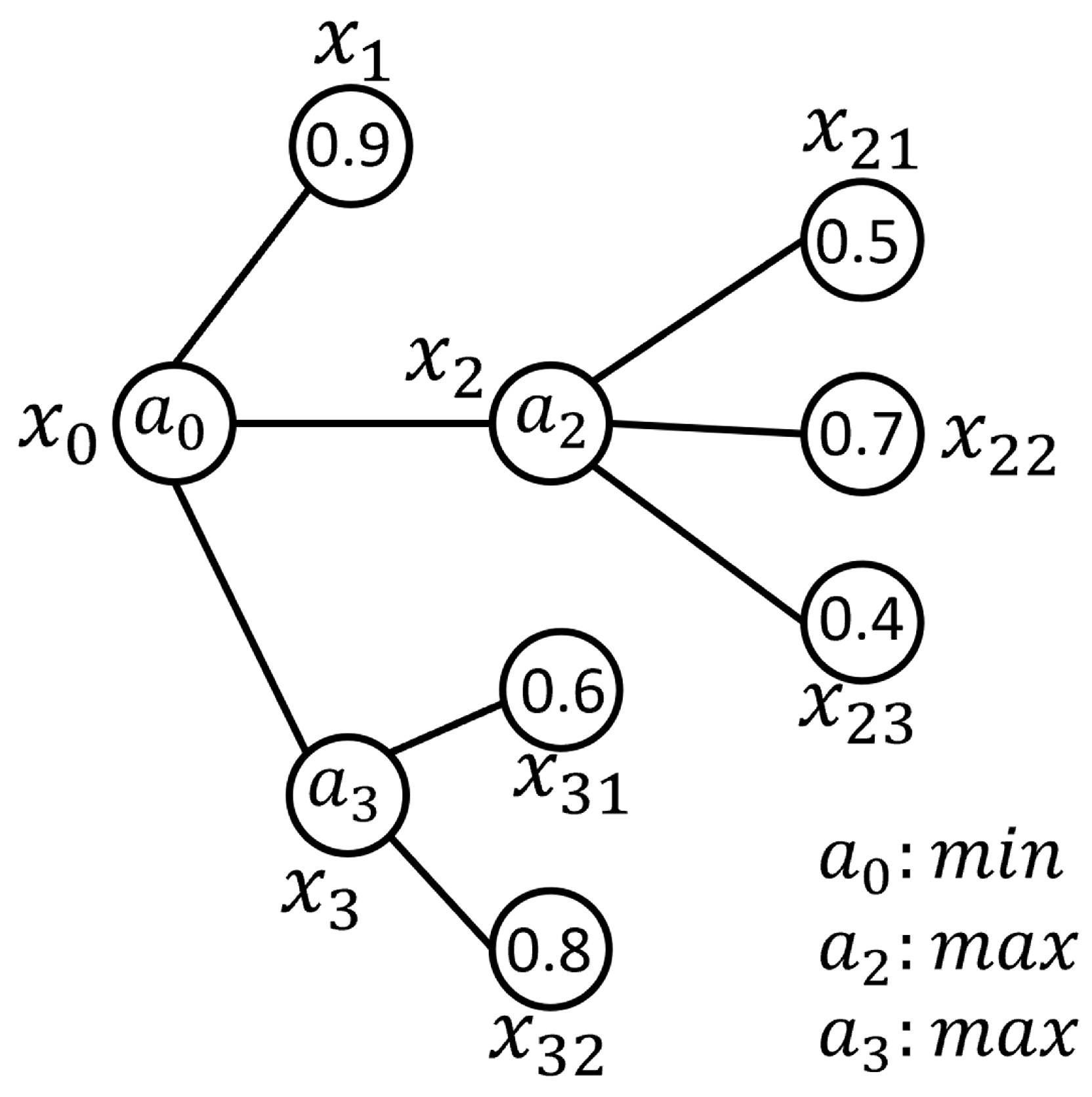

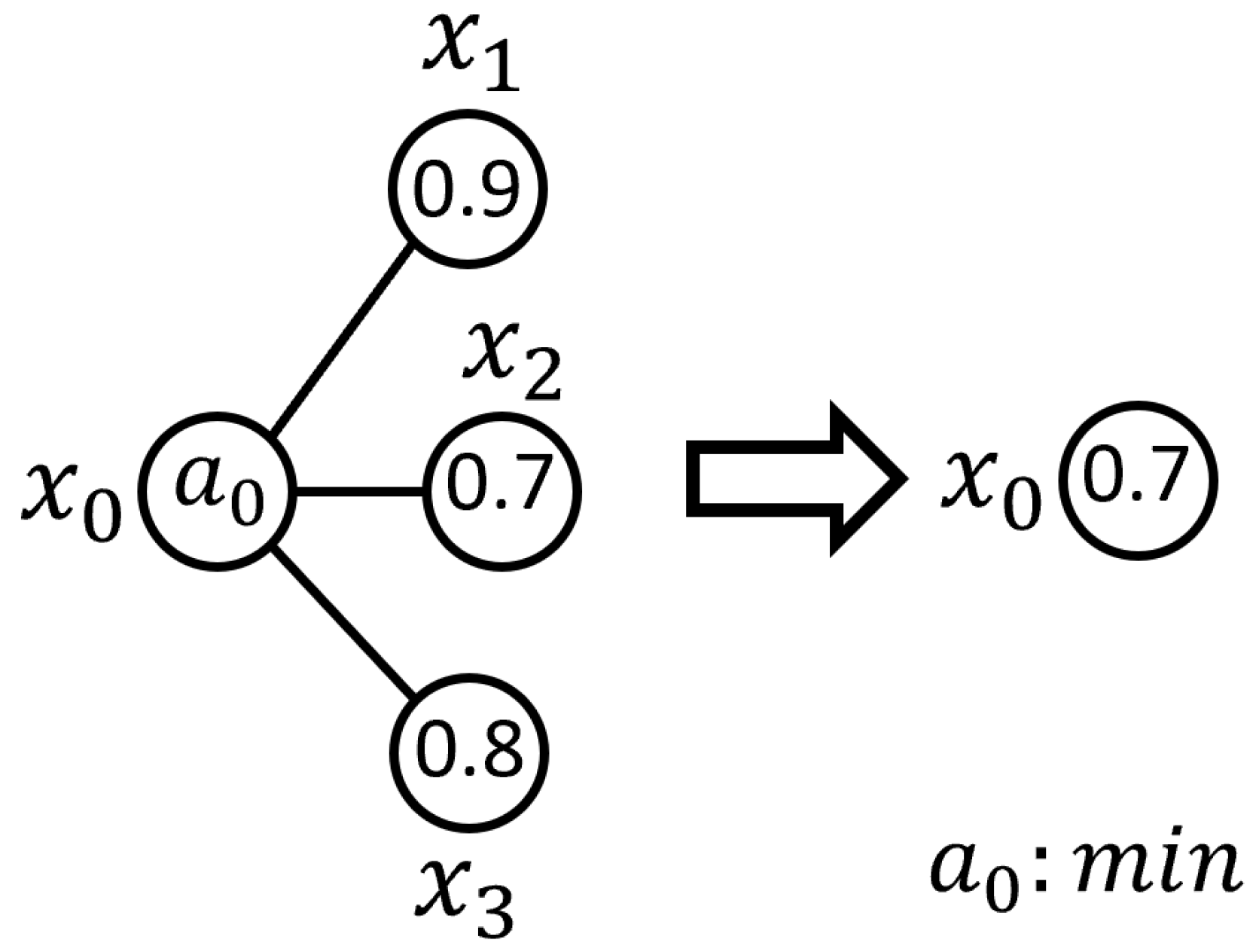

- T-norms (Triangular Norms): Such as minimum and product. These operators are typically used for an “AND”-like aggregation, where the output is sensitive to the lowest input values. The minimum operator represents a pessimistic view (the chain is only as strong as its weakest link), while the product provides a smoother, more balanced aggregation.

- T-conorms (Triangular Conorms): Such as maximum. These are used for an “OR”-like aggregation, representing an optimistic view where the output is driven by the highest input value.

- Averaging Operators: Such as the arithmetic mean. These provide a neutral, linear combination of all input values.

2.2. Path Planning in Robotics

2.3. Synthesis and Research Gap

3. Methodology

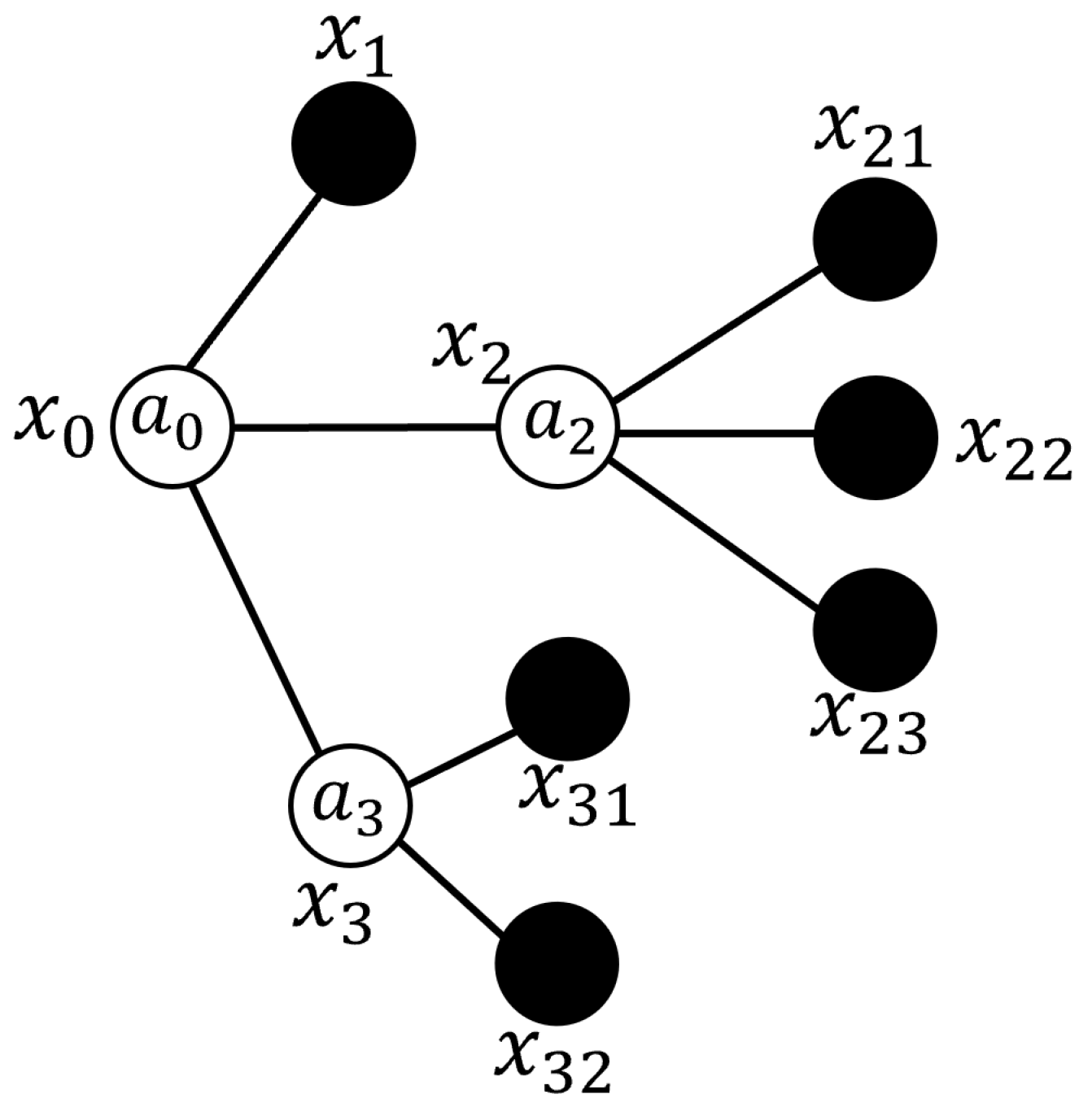

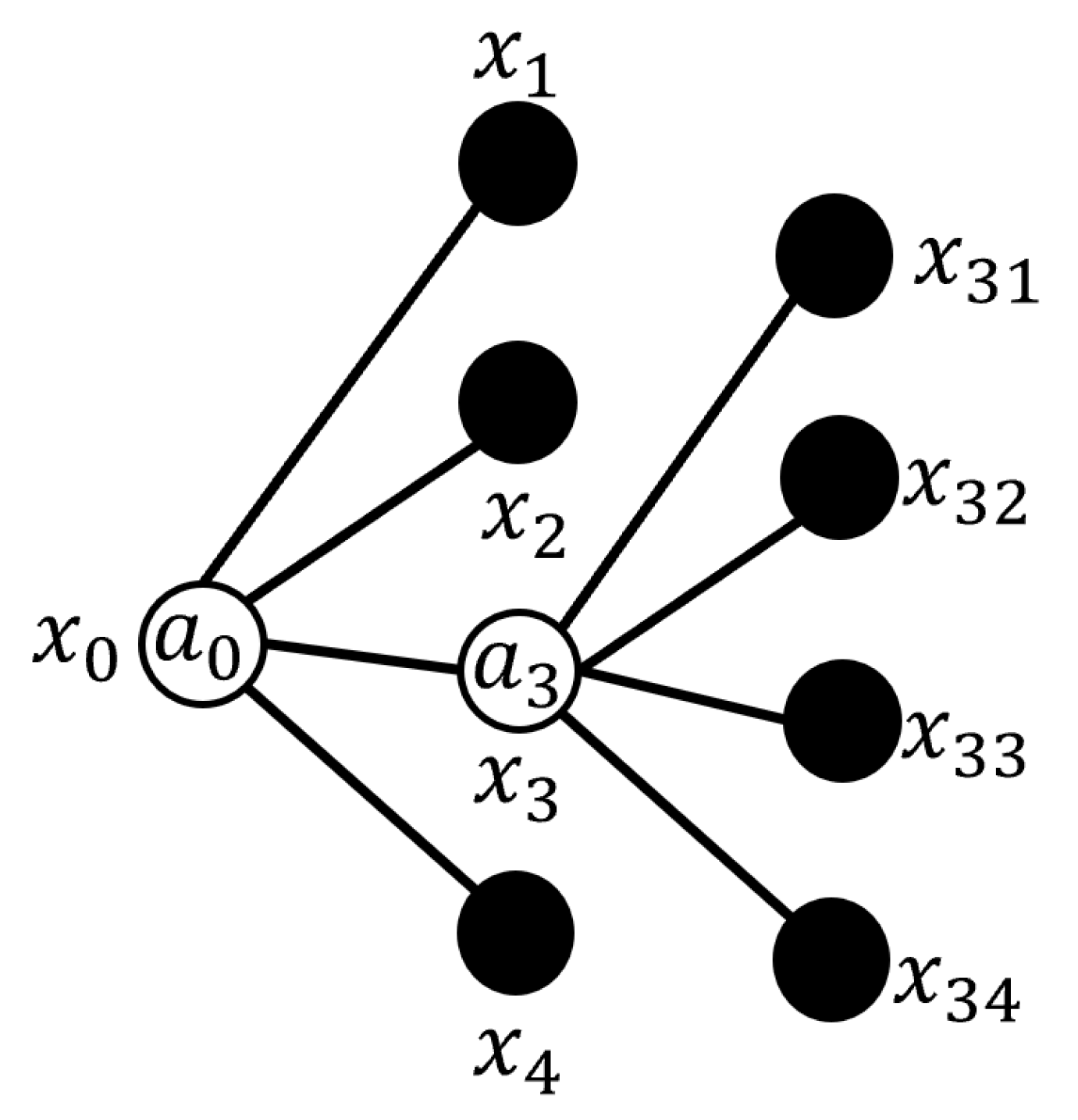

3.1. Fuzzy Signatures (FSigs)

3.2. Aggregation Operators and Assessment of Their Impacts

3.3. Fuzzy Situational Maps (FSMs)

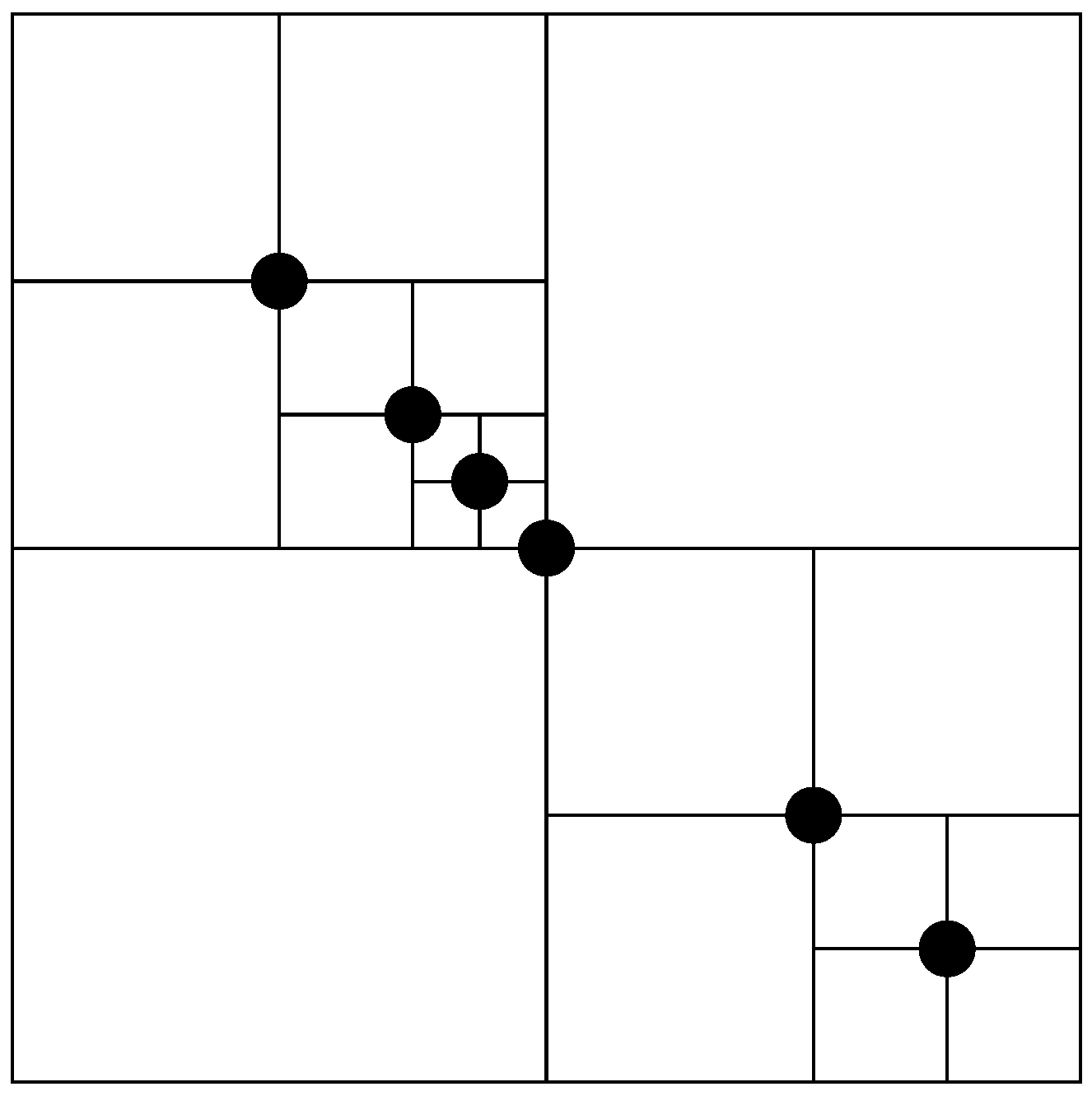

3.4. Quadtrees

3.5. Fuzzy Signatures Based Environment Representation

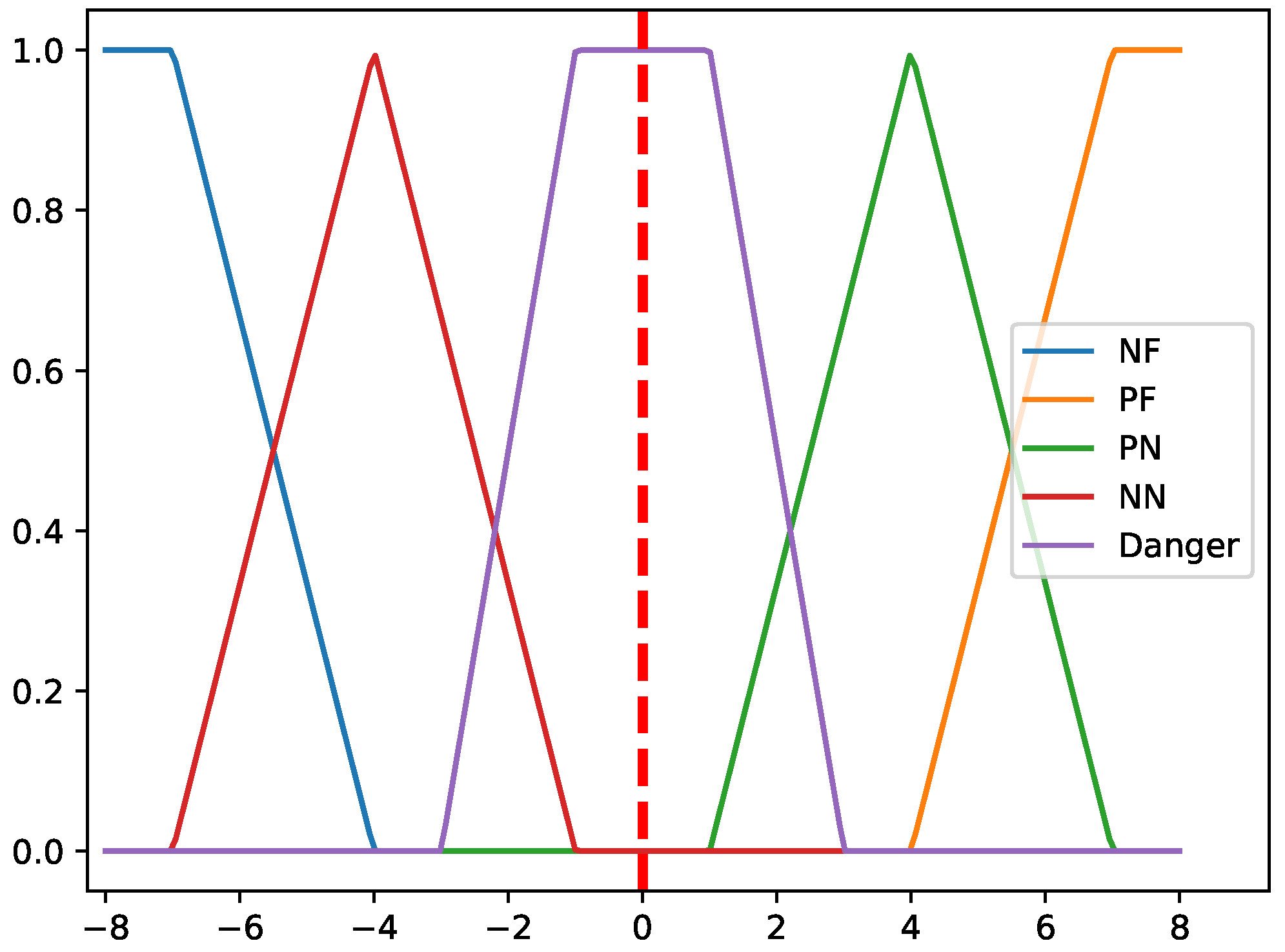

- Negative Far (NF): Indicates a situation where the attribute of interest is positioned far away from the robot on the negative side of the axis, signifying no immediate threat or concern.

- Negative Near (NN): Represents that the attribute is relatively near to the robot on the negative side of the axis, posing a significant risk that requires attention.

- Danger (D): Denotes a critical scenario where the attribute is dangerously close to the robot, necessitating immediate action to avoid a potential collision.

- Positive Near (PN): Similar to NN, but on the positive side of the axis, signifying a considerable risk due to proximity to the robot.

- Positive Far (PF): Similar to NF, but on the positive side of the axis, indicating that the attribute is far from the robot and does not pose an immediate danger.

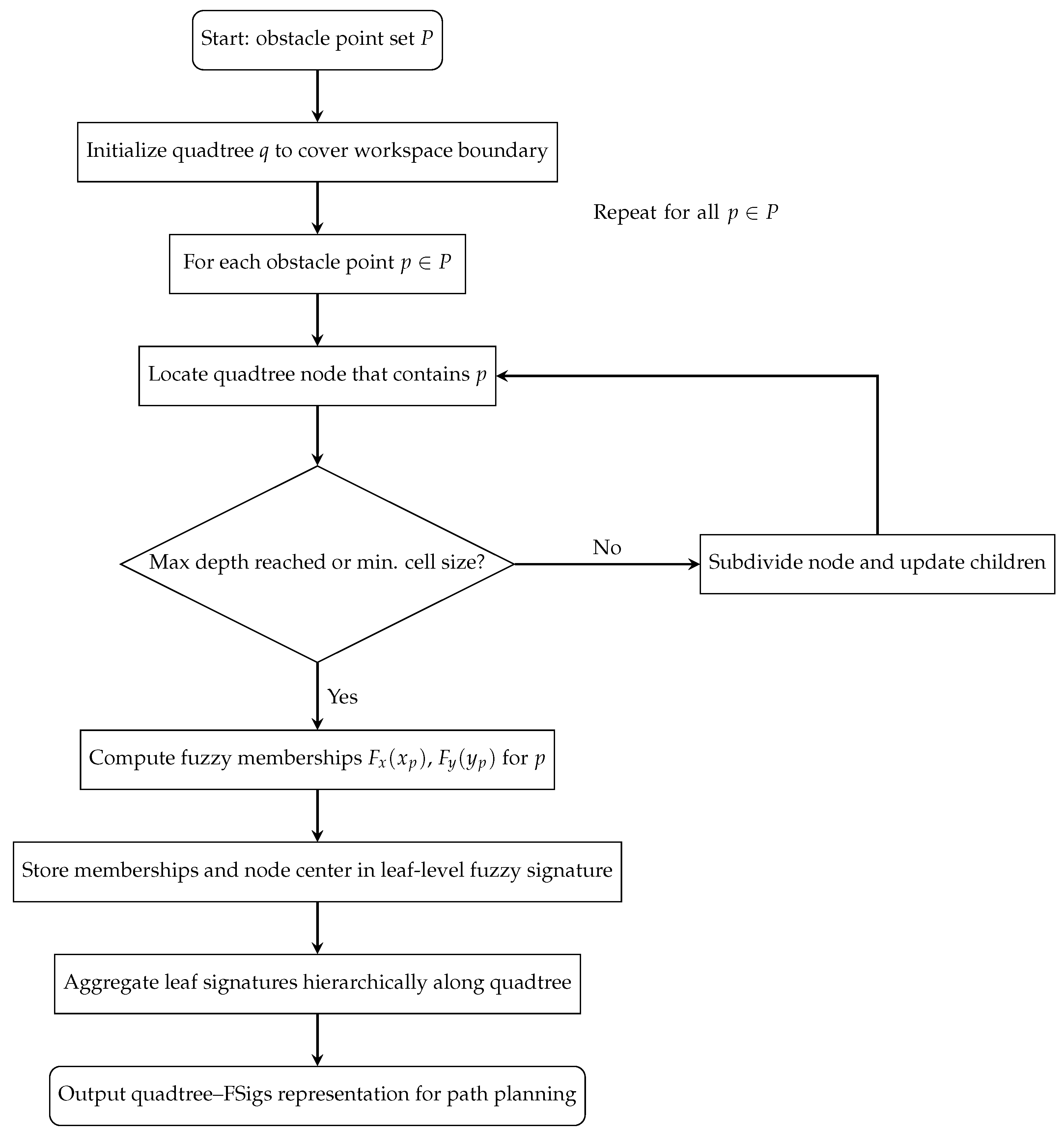

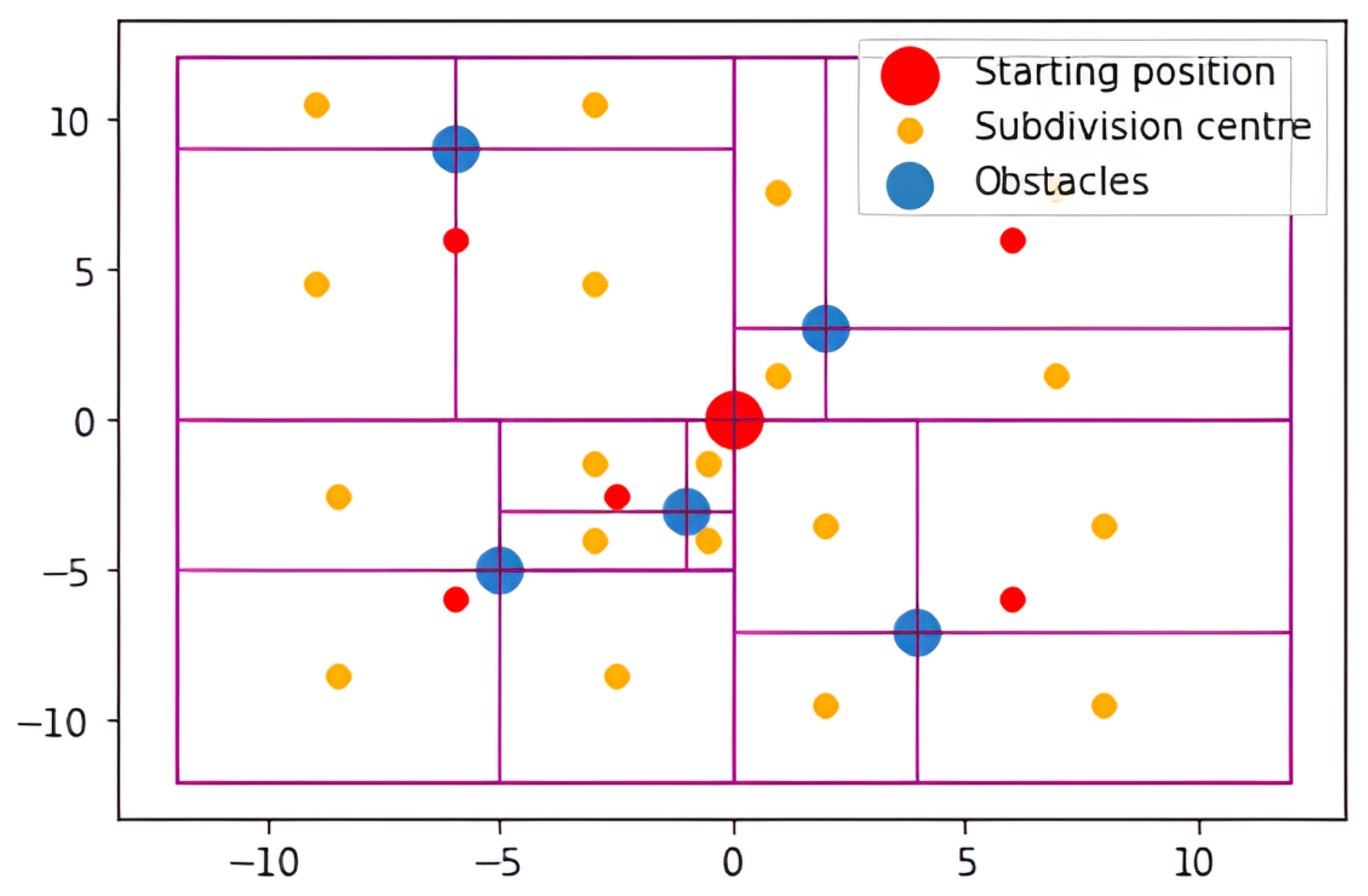

- Begin by setting up the quadtree q to cover the designated boundary area of the robot’s environment. This boundary defines the spatial extent within which the robot operates and where obstacles may be present.

- For each point p in the set P, divide the space as needed and place p at the center of the newly formed sector. Identify the fuzzy sets associated with p and save them alongside their coordinates. Modify the membership function of the obstacle to represent its specific properties. Create four child nodes for each node, defining their subdivided boundaries in advance but leaving their values unassigned for now.

- When a sector reaches its maximum allowable depth, then update the fuzzy signature value associated with that node. Modify the membership functions if necessary, which might happen when a new obstacle with more significant attributes is identified or because of the defuzzification process.

3.6. Path Planning Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Path Finding Algorithm |

|

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Computational Complexity Comparison

5.2. Practical Implications and Generalizability

5.3. Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hentout, A.; Maoudj, A.; Kouider, A. Shortest Path Planning and Efficient Fuzzy Logic Control of Mobile Robots in Indoor Static and Dynamic Environments. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 27, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrun, S.; Burgard, W.; Fox, D. Probabilistic Robotics (Intelligent Robotics and Autonomous Agents); The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Karadeniz, A.M.; Ballagi, A.; Kóczy, L.T. Transfer Learning-Based Steering Angle Prediction and Control with Fuzzy Signatures-Enhanced Fuzzy Systems for Autonomous Vehicles. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, N.F.; Saygın, A.; Türk, F. Utilizing VR Technology in Foundational Welding Skill Development. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, A.M.; Hajdu, C.; Kóczy, L.T. Mobile Robot Environment Representation Through Fuzzy Signatures-Integrated Quadtrees. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 28, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kóczy, L.T.; Cornejo, M.E.; Medina, J. Algebraic structure of fuzzy signatures. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2021, 418, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Jin, Z.; Gedeon, T.; Biswas, A.; Tabassum, R.; Shubho, F.H.; Rahman, S. Aggregated Fuzzy Signature Structures for Multi-class Medical Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing, Auckland, New Zealand, 2–6 December 2024; Mahmud, M., Doborjeh, M., Wong, K., Leung, A.C.S., Doborjeh, Z., Tanveer, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowaková, J.; Prílepok, M.; Snášel, V. Medical Image Retrieval Using Vector Quantization and Fuzzy S-tree. J. Med. Syst. 2017, 41, 18, Erratum in: J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-0957-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.W.; Chumwatana, T.; Tikk, D. Exploring the use of fuzzy signature for text mining. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 18–23 July 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jočić, D.; Štajner Papuga, I. A Note on Aggregation of t-norm-based, Fuzzy Vector Subspaces. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2025, 22, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R.; Filev, D.P. Essentials of Fuzzy Modeling and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J. Optimization of a Navigation System for Autonomous Charging of Intelligent Vehicles Based on the Bidirectional A* Algorithm and YOLOv11n Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ge, S.S. Efficient Package Delivery Task Assignment for Truck and High Capacity Drone. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 13422–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Wei, G. A Comprehensive Review of Path-Planning Algorithms for Planetary Rover Exploration. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugaraja, M.; Thangamuthu, M.; Ganesan, S. Hybrid Path Planning Algorithm for Autonomous Mobile Robots: A Comprehensive Review. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, A.; Dong, C.; Dai, H.; Xu, Z. Completion Time Minimization for Multi-UAV Information Collection via Trajectory Planning. Sensors 2019, 19, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ibáñez, J.R.; Pérez-del Pulgar, C.J.; García-Cerezo, A. Path Planning for Autonomous Mobile Robots: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koçak, N.F.; Saygın, A. Real-time laser weld point seam tracking system for robotic welding. J. Comput. Electr. Electron. Eng. Sci. 2025, 3, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, M.; Huang, L.; Shi, K.; Zou, C.; Chen, B. Local Path Planning for Mobile Robots Based on Fuzzy Dynamic Window Algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, M.A.; Khanday, O.M.; Kovács, S. Implementation Guidelines for Ethologically Inspired Fuzzy Behaviour-Based Systems. Infocommun. J. 2024, XVI, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betalo, M.L.; Leng, S.; Mohammed Seid, A.; Nahom Abishu, H.; Erbad, A.; Bai, X. Dynamic Charging and Path Planning for UAV-Powered Rechargeable WSNs Using Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 15610–15626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, A.M.; Hajdu, C.; Rutkowska, D.; Kóczy, L.T. Hypergraph Formalism for Fuzzy Signature-Based Robot Environment Representation. J. Artif. Intell. Soft Comput. Res. 2025, 16, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precup, R.E.; Bojan-Dragos, C.A.; Gao, K.; Cui, S. Problem Setting for Trajectory Planning and Cruise Control of a Connected Autonomous Electric Bus in Intersection Scenarios with Human-Driven Vehicles to Optimize Energy, Comfort and Tracking. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 28, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ala, A.; Liu, Z.; Cui, W.; Ding, H.; Jin, G.; Lu, X. A Hybrid Equilibrium Optimizer Based on Moth Flame Optimization Algorithm to Solve Global Optimization Problems. J. Artif. Intell. Soft Comput. Res. 2024, 14, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozna, C.; Minculete, N.; Precup, R.E.; Kóczy, L.T.; Ballagi, A. Signatures: Definitions, operators and applications to fuzzy modelling. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2012, 201, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballagi, A.; Pozna, C.; Földesi, P.; Kóczy, L. Fuzzy Situational Maps: A new approach in mobile robot cooperation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 17th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES), San Jose, CA, USA, 19–21 June 2013; pp. 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zakaria, M.A.; Younas, M. Path Planning Trends for Autonomous Mobile Robot Navigation: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, A.M.; Hajdu, C.; Kóczy, L.T.; Ballagi, Á. Robot environment representation based on Quadtree organization of Fuzzy Signatures. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Timisoara, Romania, 19–21 May 2021; pp. 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könczöl, B.; Gál, L. Analysing fuzzy logic-based line following model car. Eng. IT Solut. 2020, 1, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, H. The Quadtree and Related Hierarchical Data Structures. ACM Comput. Surv. 1984, 16, 187–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, D. Geometric modeling using octree encoding. Comput. Graph. Image Process. 1982, 19, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyeri, U.; Dindar, T.; Kökver, Y.; Koçak, N.F. Machine learning methods on quantized vectors. J. Comput. Electr. Electron. Eng. Sci. 2023, 1, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyombo, M.E.; Liu, Y.-k.; Mulenga, C.M.; Siamulonga, A.; Kabanda, M.C.; Shaba, P.; Xi, C.; Ayodeji, A. Optimal path planning in a real-world radioactive environment: A comparative study of A-star and Dijkstra algorithms. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 420, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadrin, G.; Krasavin, A.; Nazenova, G.; Kussaiyn-Murat, A.; Kadyroldina, A.; Haidegger, T.; Alontseva, D. Application of Compensation Algorithms to Control the Speed and Course of a Four-Wheeled Mobile Robot. Sensors 2024, 24, 7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R.; Watanobe, Y.; Islam, M.R.; Naruse, K. Enhanced Robot Motion Block of A-Star Algorithm for Robotic Path Planning. Sensors 2024, 24, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature/Approach | Existing Fuzzy Path Planning (FPP) Methods | General Fuzzy Signature (FSigs) Applications | Proposed FSigs-Quadtree Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Structure | Often uses linear rule-bases, sensor models, or dynamic windows [21,22]. | Nested vectors or graphical FSigs focused on symbolic data [24,25,26]. | Quadtree-organized hierarchical FSigs combined with path planning |

| Main Application Focus | Real-time control, local obstacle avoidance, trajectory generation [21,22,25,27]. | Medical diagnosis, image processing, data mining, and knowledge representation [8,9,10,16]. | Empirical study on aggregation operator impact for global path planning efficiency |

| Hierarchy/Structure | May utilize fuzzy logic, but lacks a formalized multidimensional hierarchy [9]. | Hierarchical but non-spatial and focused on abstract symbolic relations [7,25,26]. | Strictly coupled spatial (Quadtree) and fuzzy (FSigs) hierarchy optimized for rapid spatial queries and dimensionality consistency |

| Research Gap Addressed | Lack of systematic use of FSigs for environment mapping [24]. | Lack of empirical analysis on aggregation operator effects on robot performance [28]. | Provides the first systematic comparison of core aggregation operators (, , , ) for FSigs in robot path planning |

| Parameters | Goal Position | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−10, −10) | (10, −10) | (10, 10) | (−10, 10) | ||

| MIN | Path Length (nodes) | 27 | 30 | 24 | 23 |

| Execution Time (s) | 0.1020 | 0.1237 | 0.0922 | 0.1146 | |

| MAX | Path Length (nodes) | 31 | 34 | 28 | 25 |

| Execution Time (s) | 0.1923 | 0.1344 | 0.0967 | 0.1079 | |

| PROD | Path Length (nodes) | 26 | 27 | 22 | 22 |

| Execution Time (s) | 0.0964 | 0.1111 | 0.0913 | 0.0961 | |

| MEAN | Path Length (nodes) | 30 | 30 | 24 | 23 |

| Execution Time (s) | 0.1036 | 0.1446 | 0.0957 | 0.0984 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karadeniz, A.M.; Hajdu, C.; Ballagi, Á.; Kóczy, L.T. Evaluating the Impact of Aggregation Operators on Fuzzy Signatures for Robot Path Planning. Sensors 2025, 25, 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237342

Karadeniz AM, Hajdu C, Ballagi Á, Kóczy LT. Evaluating the Impact of Aggregation Operators on Fuzzy Signatures for Robot Path Planning. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237342

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaradeniz, Ahmet Mehmet, Csaba Hajdu, Áron Ballagi, and László T. Kóczy. 2025. "Evaluating the Impact of Aggregation Operators on Fuzzy Signatures for Robot Path Planning" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237342

APA StyleKaradeniz, A. M., Hajdu, C., Ballagi, Á., & Kóczy, L. T. (2025). Evaluating the Impact of Aggregation Operators on Fuzzy Signatures for Robot Path Planning. Sensors, 25(23), 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237342