Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning for MRI Brain Tumor Classification Using CLIP and Vision Transformers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning for Data Efficiency

1.2. Our Work and Contributions

- Research Questions (RQs)

- Can FSL models such as Prototypical Networks classify brain tumors effectively under few-shot constraints?

- How does CLIP-based ZSL compare against purely visual FSL models in this medical domain?

- What trade-offs exist between interpretability, precision, and data efficiency for these models?

- Rigorous Comparative Analysis. We conduct a direct performance comparison between Prototypical Networks (FSL) and CLIP (ZSL), rigorously benchmarking these distinct learning paradigms under data-scarce constraints. This includes a rigorous 1000-episode evaluation, replacing earlier single-split results.

- Prompt Engineering Analysis. This research presents a systematic evaluation of prompt engineering strategies for zero-shot medical image classification, including a CLIP prompt ablation study with four prompt styles, demonstrating how prompt design significantly impacts CLIP performance on tumor classification.

- Optimal Data Efficiency Analysis. Through extensive evaluation with varying numbers of support samples, we identify the minimal data requirements for reliable tumor classification and quantify the relationship between sample size and performance, demonstrating high accuracy (up to 85%) in extremely low-data scenarios.

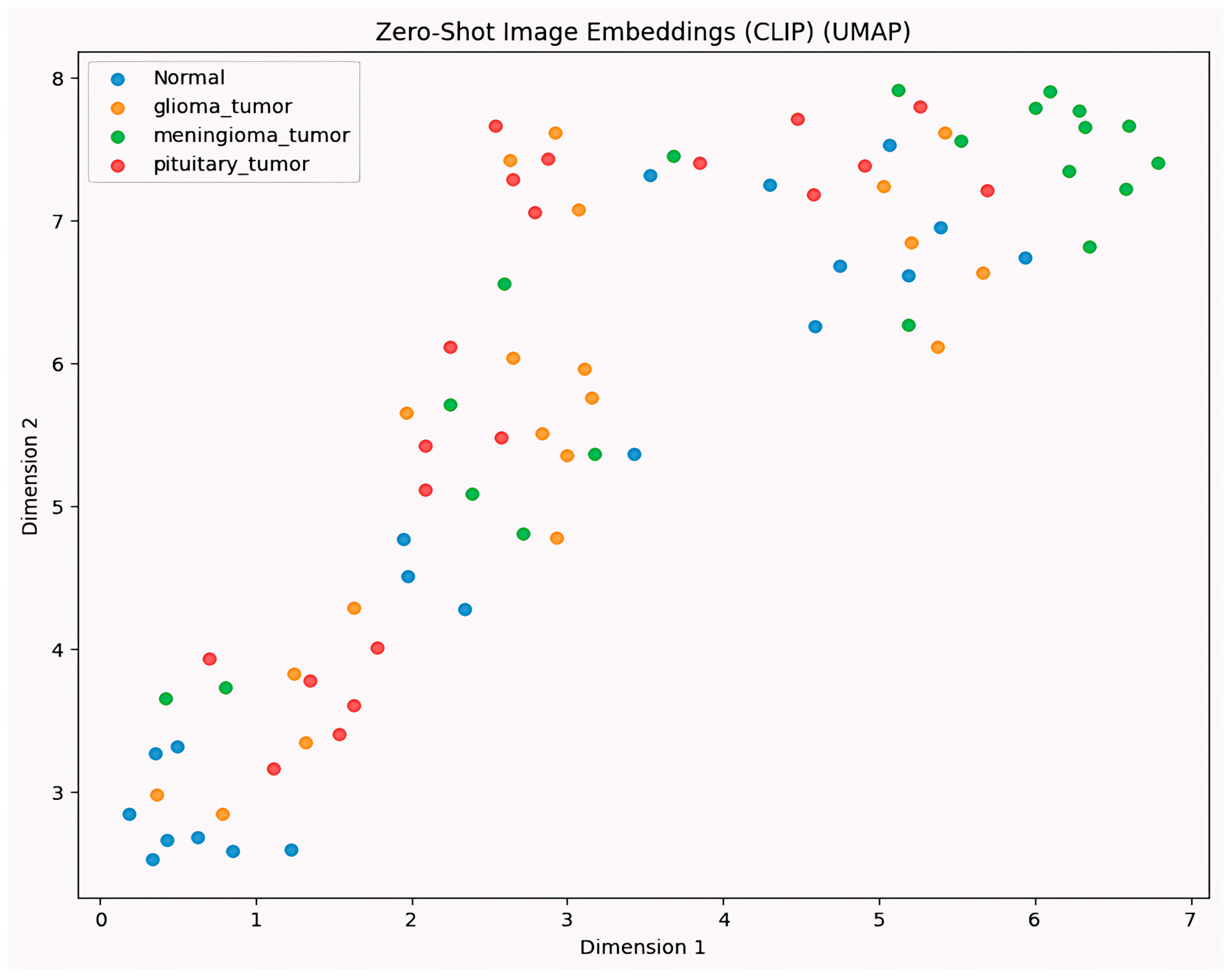

- Detailed Interpretability Assessment. Our research analyzes the model decision-making processes through gradient-based visualization techniques (Grad-CAM) and UMAP visualization, ensuring that classifications are based on clinically relevant features rather than artifacts and providing a detailed analysis of interpretability.

- Real-World Applicability. We validate a system that can act as a practical diagnostic support tool for data-efficient classification of brain tumors in clinical settings with limited radiological imaging data, addressing a key bottleneck in AI-driven healthcare.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset

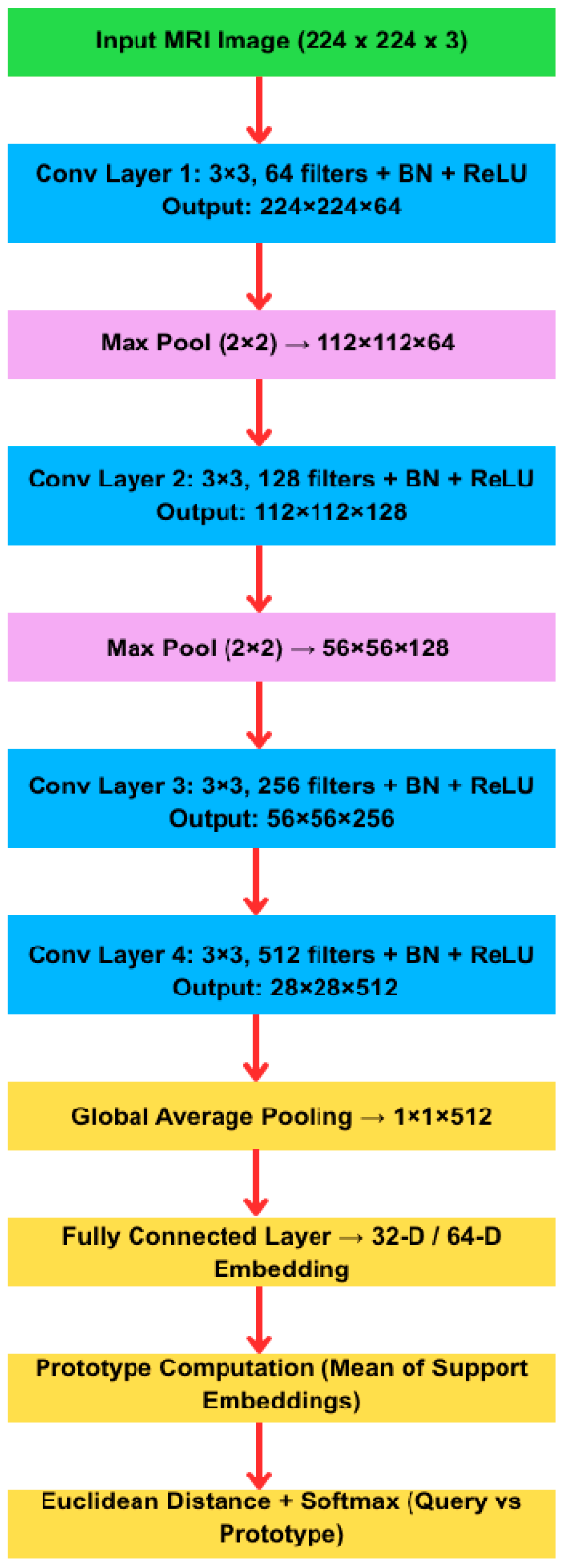

3.2. Model Architectures

- The architecture variants tested are as follows:

3.3. Training and Implementation Details

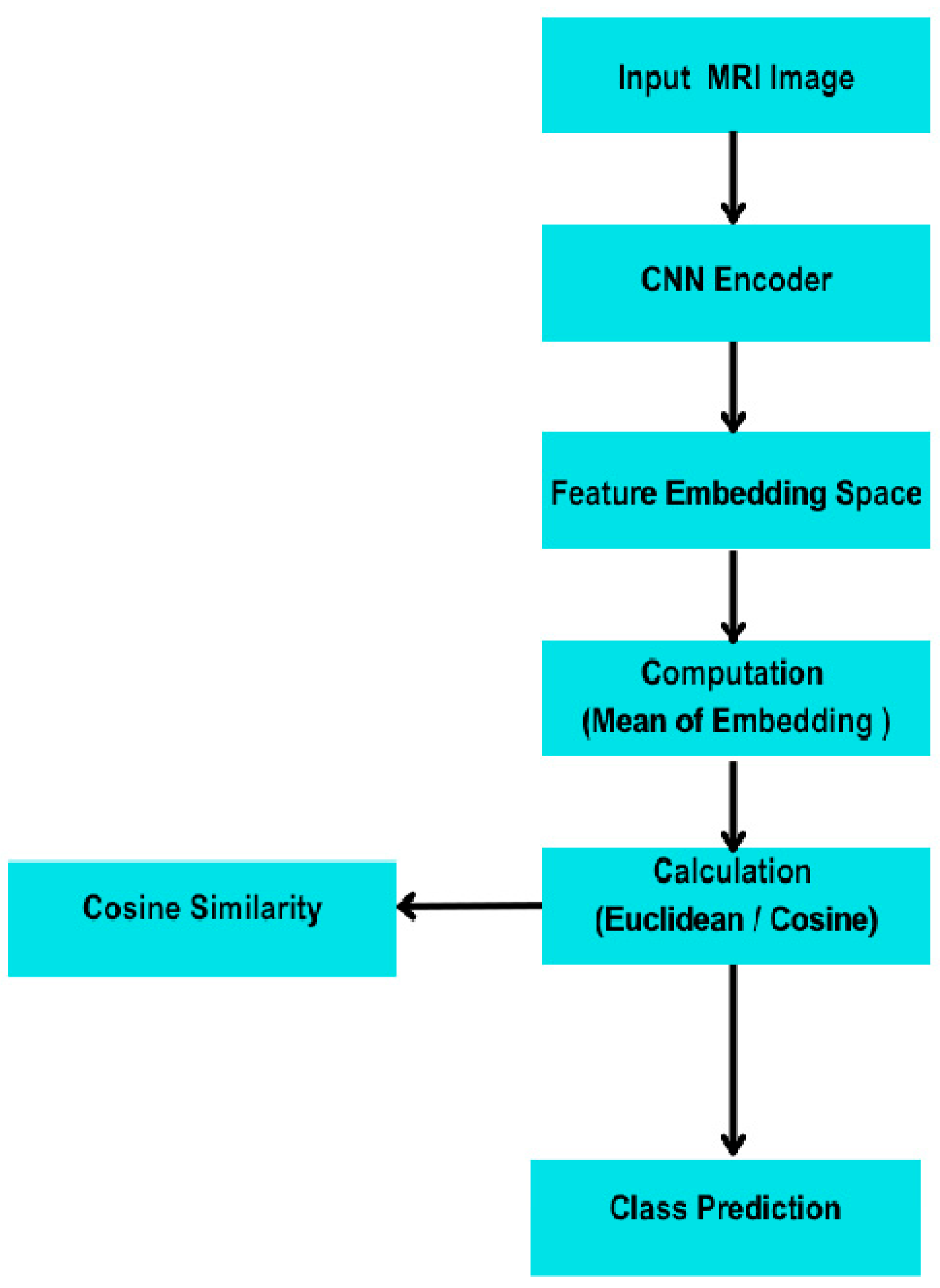

- Few-Shot Learning (FSL)—Prototypical Network

- Episodes. The model was trained and evaluated in 4-way K-shot episodes (4 classes, K examples/class), using 5 query examples per class for validation. We explored K = 1, 5, and 10.

- Distance Metric. Euclidean distance was used to compare query embeddings to class prototypes.

- Loss Function. Negative log-likelihood over softmax probabilities derived from distance-based similarity scores was minimized.

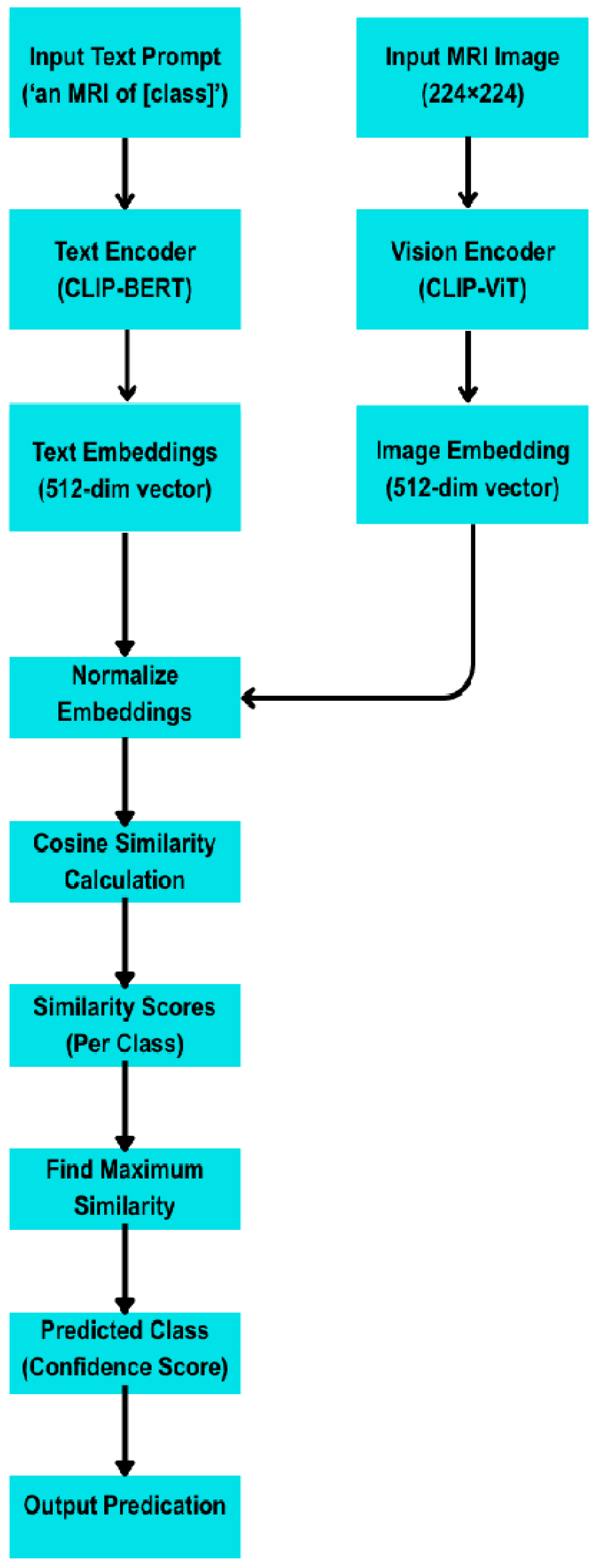

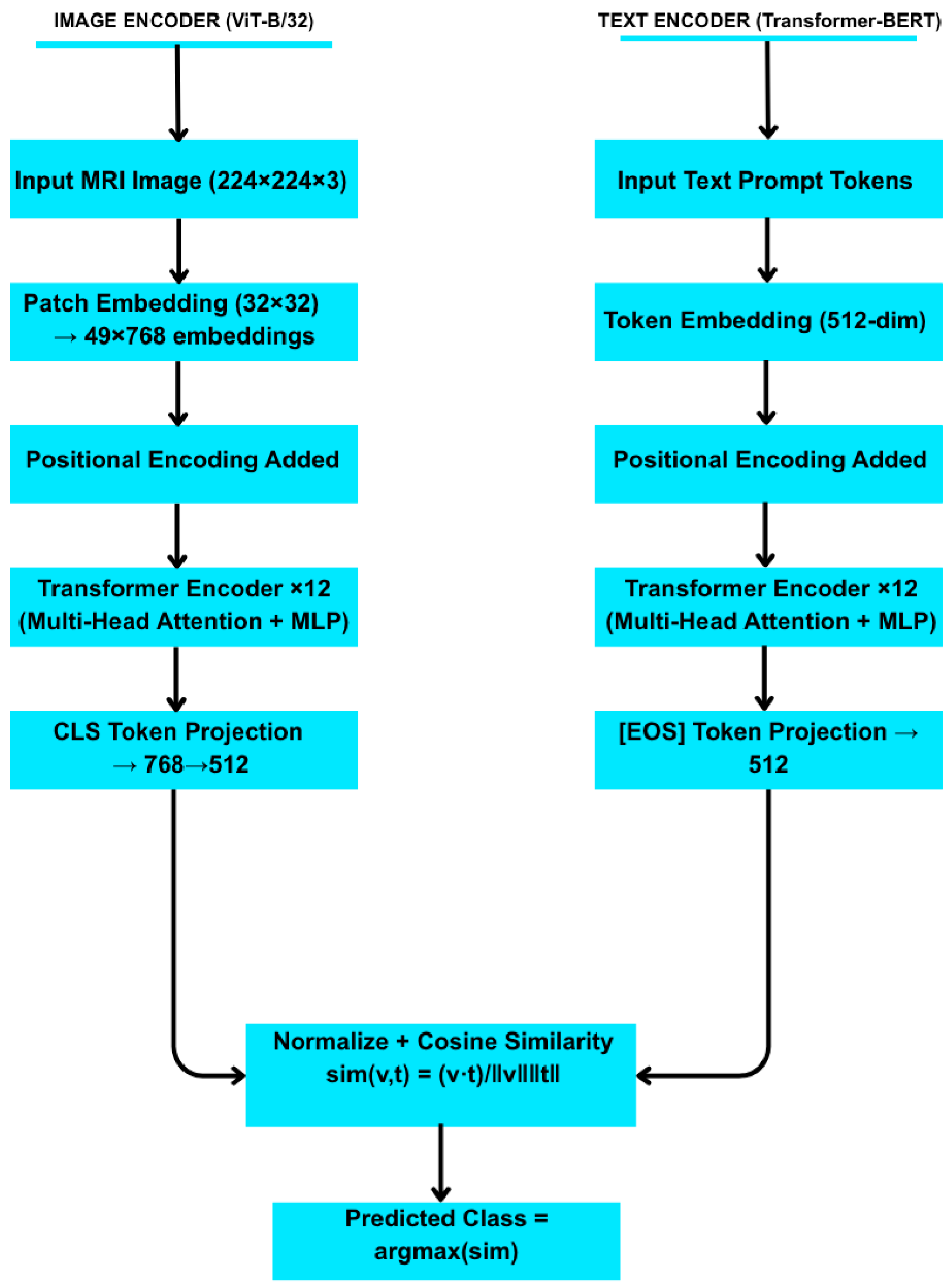

- Zero-Shot Learning with CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training)

- Text Prompts. Each class label was associated with five handcrafted natural language prompts, such as “An MRI image of a brain with a pituitary tumour.”

- Image Encoding. Each test image was encoded via CLIP’s visual encoder.

- Classification. The cosine similarity between the image embedding and the average of each class’s text prompt embeddings was computed. The class with the highest similarity was selected.

- Prompt Engineerin and Text Encoding

- Prompt Examples

- Normal: “An MRI of a healthy brain.” “No visible tumours in this scan.”

- Glioma: “An MRI showing a glioma tumour.” “Malignant glioma present.”

- Meningioma: “A benign meningioma tumour seen in this MRI.” “Well-defined meningioma mass.”

- Pituitary: “A pituitary tumour pressing on the optic chiasm.” “Enlargement of pituitary gland in MRI.”

4. Experiments

Simulation Setup

- Few-shot learning using Prototypical Networks;

- Zero-shot learning using the CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) model simulations were carefully timed and logged for reproducibility and benchmarking.

- Fine-Tuning Baseline

| Algorithm 1: Few-Shot Learning with Prototypical Networks |

| Pseudocode for Prototypical Network Training (4-way K-shot) Initialize embedding network f_θ (3-layer CNN) Repeat for each training episode: Sample support set S and query set Q from training data For each class c ∈ {1,…,4}: Compute prototype p[c] = (1/|S_c|) × Σ_{(x_i,y_i)∈S, y_i = c} f_θ(x_i) For each query example (x, y) ∈ Q: For each class c: d[c] = Euclidean Distance(f_θ(x), p[c]) # ||f_θ(x) − p[c]||_2 Compute class probabilities via softmax: P(y = c|x) = exp(−d[c])/Σ_{c′} exp(−d[c′]) Accumulate loss L += −log P(y_true|x) Update network parameters θ by minimizing L (e.g., via Adam optimizer) |

| Algorithm 2: Zero-Shot Learning with CLIP |

| Pseudocode for CLIP Zero-Shot Classification: Load pretrained CLIP model with image encoder E_img and text encoder E_txt For each class c: Define a set of textual prompts for class c Compute text embeddings t[c] = (1/N_p) ∗ Σ_{prompt} E_txt(prompt) # average over prompts For each test image x: Compute image embedding v = E_img(x) For each class c: sim[c] = cosine_similarity(v, t[c]) = (v · t[c])/(||v|| ||t[c]||) Predicted class = argmax_c sim[c] |

5. Results

5.1. Few-Shot (Prototypical Network)

5.2. Zero-Shot (CLIP)

- Overall Comparison

- Analysis of Prototypical Network (ProtoNet) Variants (FSL)

- ProtoNet ResNet-18 Embed Dim 32 (Best Model)

- Comparison with other ProtoNet Variants

- Analysis of Fine-Tuned Baseline and Image-Proto

- Finetune ResNet-50 (Baseline)

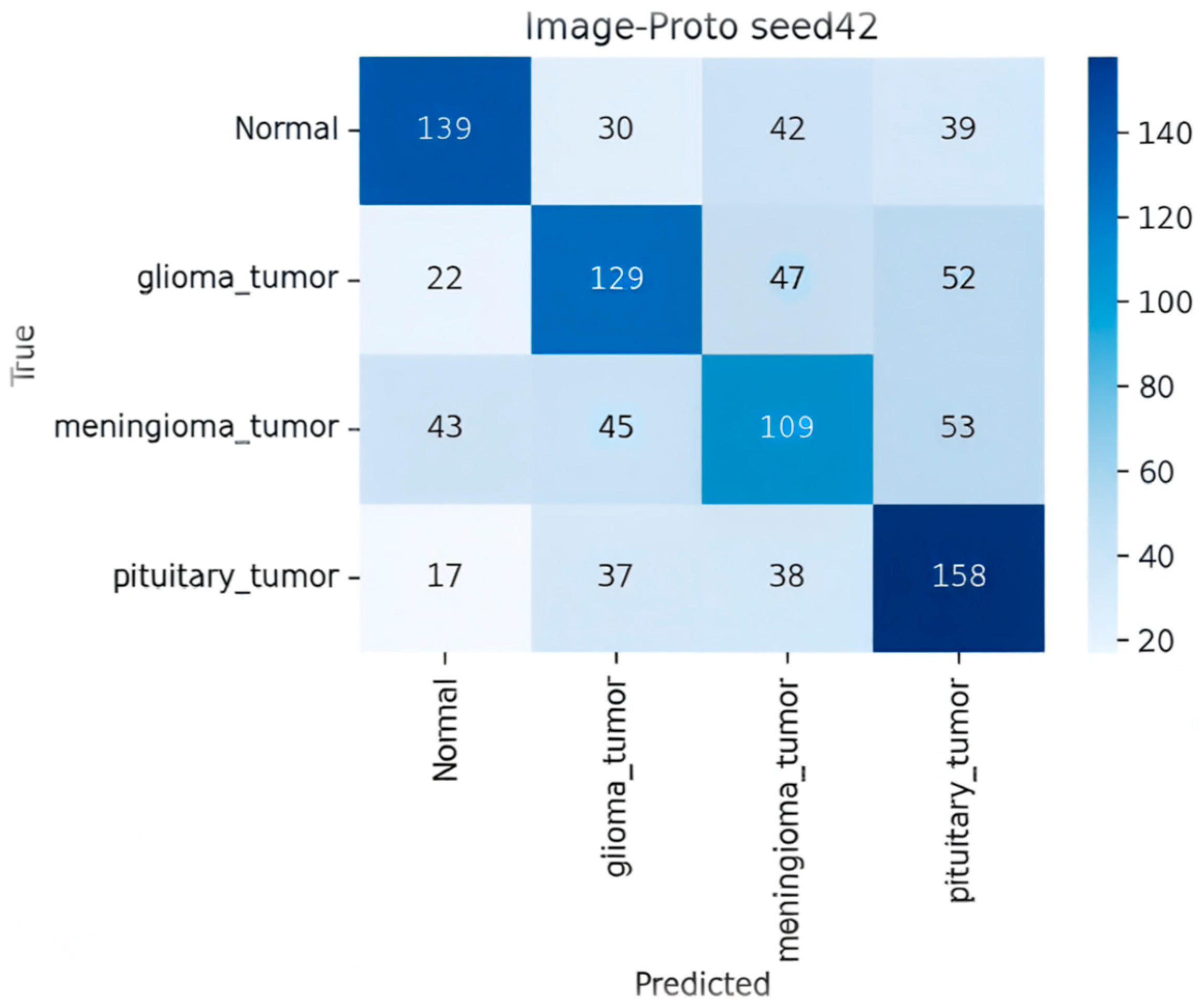

- Image-Proto (Zero-Shot/FSL Hybrid)

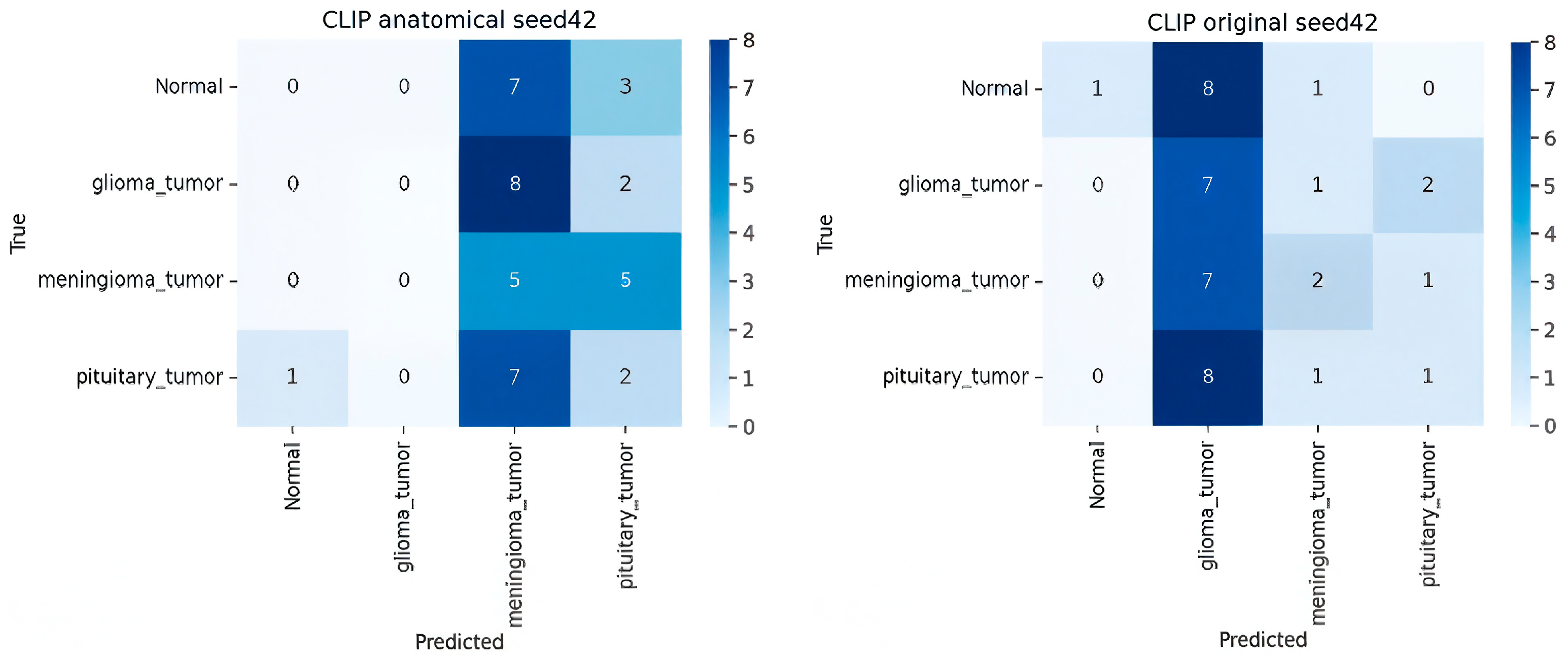

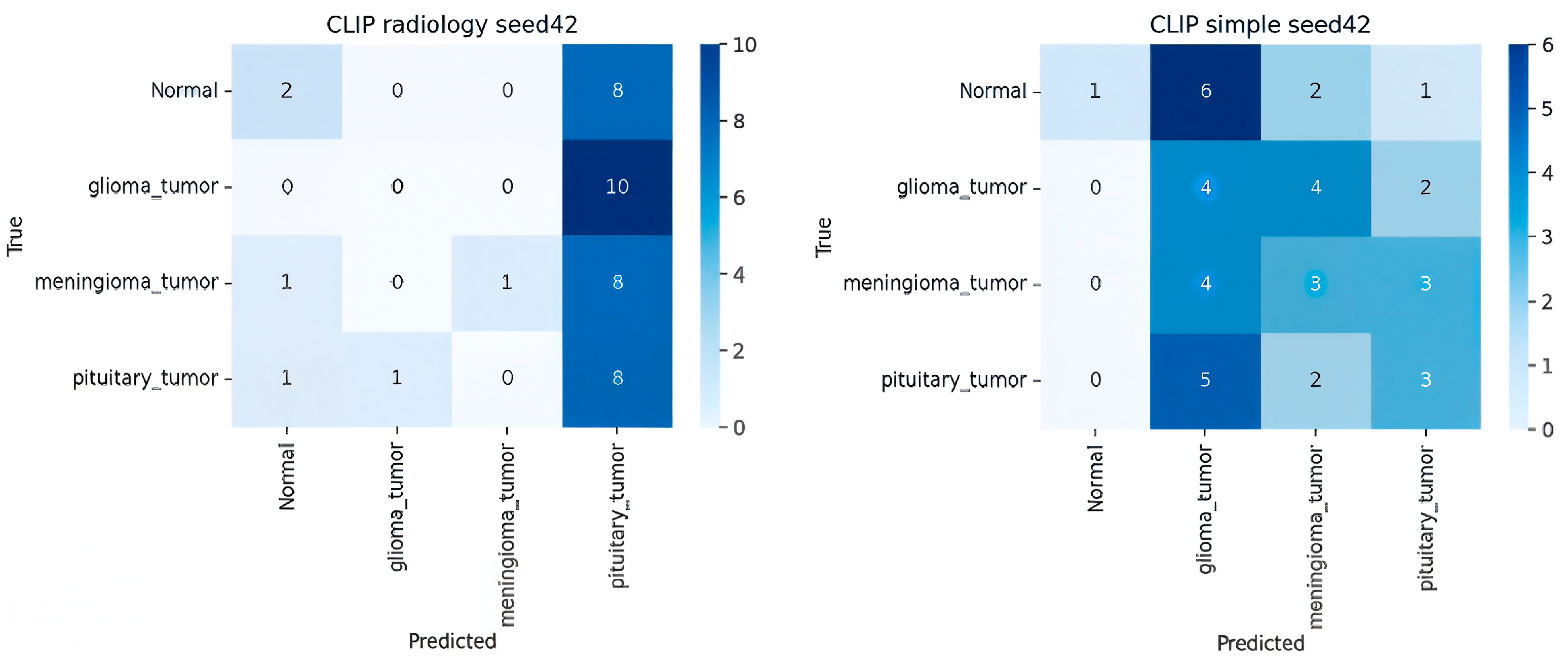

- Analysis of CLIP Zero-Shot (ZSL) Variants

- Ablation Studies

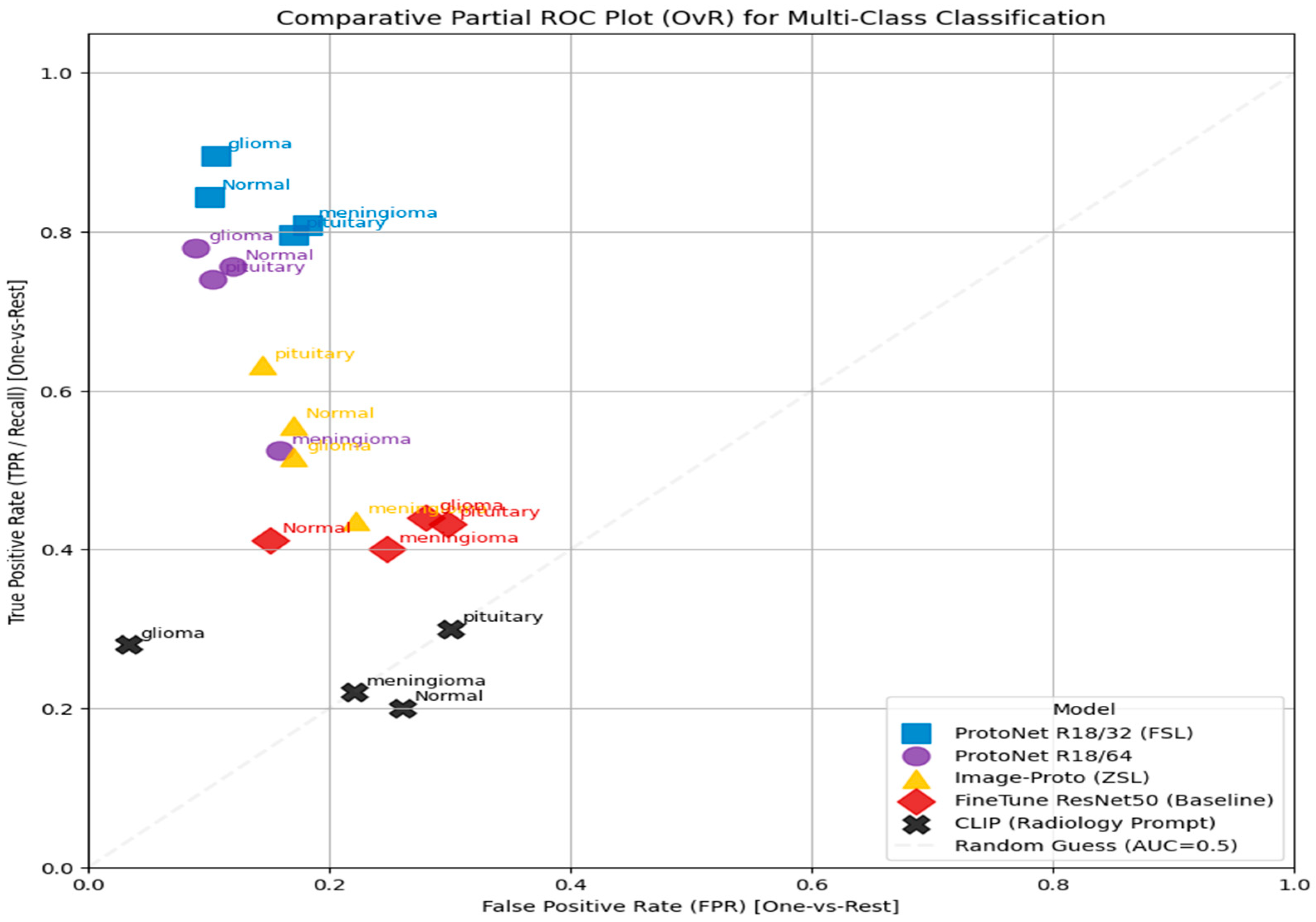

- Comparative Partial ROC Plot Analysis

5.3. Discussion

- Performance and Methodological Trade-Offs

- Contextualization within the Literature

- Interpretability

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

- Data and Evaluation Scope

- Model-Specific Constraints

- Clinical and Statistical Rigor

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menze, B.H.; Jakab, A.; Bauer, S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Farahani, K.; Kirby, J.; Burren, Y.; Porz, N.; Slotboom, J.; Wiest, R.; et al. The Multimodal Brain Tumor Image Segmentation Benchmark (BRATS). IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 1993–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, J.; Swersky, K.; Zemel, R. Prototypical Networks for Few-Shot Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4077–4087. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Blundell, C.; Lillicrap, T.; Wierstra, D. Matching Networks for One-Shot Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29, 3630–3638. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.; Vendt, B.; Smith, K.; Freymann, J.; Kirby, J.; Koppel, P.; Moore, S.; Phillips, S.; Maffitt, D.; Pringle, M.; et al. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): Maintaining and operating a public information repository. J. Digit. Imaging 2013, 26, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.-Z.; Ni, D.; Chou, Y.-H.; Qin, J.; Tiu, C.-M.; Chang, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-S.; Shen, D.; Chen, C.-M. Computer-aided diagnosis with deep learning architecture: Applications to breast lesions in US images and pulmonary nodules in CT scans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Huang, W.; Cao, S.; Yang, R.; Yang, W.; Yun, Z.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Q. Enhanced performance of brain tumor classification via tumor region augmentation and partition. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, D.; Wickramasinghe, D.; Wijerathne, T.; Meedeniya, D.; Yogarajah, P. Brain Tumour Segmentation and Edge Detection Using Self-Supervised Learning. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. (IJOE) 2025, 21, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermany, D.S.; Goldbaum, M.; Cai, W.; Valentim, C.C.S.; Liang, H.; Baxter, S.L.; McKeown, A.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. Cell 2018, 172, 1122–1131.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xin, T.; Zhang, H. Transformer-Based Few-Shot Segmentation for Medical Imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 3205–3218. [Google Scholar]

- Dhinagar, N.J.; Santhalingam, V.; Lawrence, K.E.; Laltoo, E.; Thompson, P.M. Few-Shot Classification of Autism Spectrum Disorder using meta-learning across mul-ti-site MRI. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gulshan, V.; Peng, L.; Coram, M.; Stumpe, M.C.; Wu, D.; Narayanaswamy, A.; Venugopalan, S.; Widner, K.; Madams, T.; Cuadros, J.; et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA 2016, 316, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çallı, E.; Sogancioglu, E.; van Ginneken, B.; van Leeuwen, K.G.; Murphy, K. Deep learning for chest X-ray analysis: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 72, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Yao, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, R.; He, Z.; Tao, X.; Zhou, S.K. CARZero: Cross-Attention Alignment for Radiology Zero-Shot Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2024/papers/Lai_CARZero_Cross-Attention_Alignment_for_Radiology_Zero-Shot_Classification_CVPR_2024_paper.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Tschandl, P.; Rinner, C.; Apalla, Z.; Argenziano, G.; Codella, N.; Halpern, A.; Janda, M.; Lallas, A.; Longo, C.; Malvehy, J.; et al. Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Shen, G.; Farris, C.W.; Zhang, X. Few-Shot Deployment of Pretrained MRI Transformers in Brain Imaging Tasks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Mohammad Hossein Hashemi. Crystal Clean: Brain Tumors MRI Dataset [Data Set]. Kaggle. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mohammadhossein77/brain-tumors-dataset (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. NeurIPS 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Badawi, M.; Abushanab, M.; Bhat, S.; Maier, A. Review of Zero-Shot and Few-Shot AI algorithms in the medical domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16143. [Google Scholar]

- Marzullo, A.; Ranzini, M.B.M. Exploring Zero-Shot Anomaly Detection with CLIP in Medical Imaging: Are We There Yet? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.09310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachetti, E.; Colantonio, S. A systematic review of few-shot learning in medical imaging. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 156, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathematics Behind K-Mean Clustering Algorithm—Muthukrishnan. 7 July 2018. Available online: https://muthu.co/mathematics-behind-k-mean-clustering-algorithm/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Alon, Y. Anomaly Detection in Monitored Systems (Part 1). Towards Data Science. 14 July 2020. Available online: https://medium.com/data-science/anomaly-detection-in-monitored-systems-part-1-a6080da61c75 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Exponential Function—Formula, Asymptotes, Domain, Range. Cuemath. Available online: https://www.cuemath.com/calculus/exponential-functions/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- MME Revise. Velocity-Time Graphs Questions|Worksheets and Revision|MME. MME. 29 August 2024. Available online: https://mmerevise.co.uk/gcse-maths-revision/velocity-time-graphs-gcse-revision-and-worksheets/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Zhang, G.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jiangqin, C.; Zhou, D.; Chai, W.; Yang, H.; Lai, Z.; He, Y. Nickel Grade Inversion of Lateritic Nickel Ore Using WorldView-3 Data Incorporating Geospatial Location Information: A Case Study of North Konawe, Indonesia. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mei, X.; Ji, G. “Walking with Dreams”: The Categories of Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy and Its Influence on Learning Engagement of Senior High School Students. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1174, Erratum in Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Ali, M.S.; Nafi, A.A.N.; Ahmed, M.F.; Ahmed, K.M.; Miah, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Niu, M. Brain tumor detection and classification in MRI using hybrid ViT and GRU model with explainable AI in Southern Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phase | No. of Images | Classes Involved | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Few-shot train | 3000 (1000/class) | 4 | Episodic training subset for few-shot learning. |

| Few-shot test | 3000 (1000/class) | 4 | Support–query episodes for evaluation. |

| Zero-shot eval | 3000 (1000/class) | 4 | CLIP zero-shot predictions (unseen samples). |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning rate | 1 × 10−4 |

| Epochs | 50 |

| Batch size (episodes) | 16 |

| Image size | 224 × 224 |

| Embedding dimensions | 32, 64 |

| Backbones | CNN/ResNet-18/ViT |

| Distance metric | Euclidean |

| Seeds | 3 |

| Loss | Prototype contrastive loss |

| Parameter Category | Description/Setting |

|---|---|

| Model Backbone | CLIP ViT-B/32 (12-layer vision transformer, patch size = 32 × 32) |

| Text Encoder | Transformer (12 layers, 512 dim text embeddings) |

| Image Encoder | Vision transformer (ViT-B/32) producing 512 dim embeddings |

| Embedding Normalization | L2 normalization applied before cosine similarity |

| Prompt Design | 5 handcrafted radiology-style prompts per class (e.g., “T1-weighted MRI showing pituitary tumour”) |

| Prompt Evaluation | 20 candidate prompts/class tested; top 5 selected by cosine similarity margin on a 1000-image validation subset |

| Classification Criterion | Cosine similarity between the averaged text and image embeddings |

| Fine-Tuning | None (true zero-shot setting) |

| Batch Size (Inference) | 32 images per batch |

| Resolution | 224 × 224 pixels |

| Computation Platform | Google Colab, Tesla T4 GPU |

| Evaluation Metric | Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC (macro-averaged) |

| Run Consistency | All random seeds fixed to 42 for reproducibility |

| Prompt Type | Example | Accuracy | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | “a photo of a brain tumour” | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| Anatomical | “an MRI image of glioma in the brain” | 0.28 | 0.21 |

| Radiology | “an axial T1-weighted MRI of a malignant tumour” | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| Descriptive | “a clinical MRI showing tumourous tissue mass” | 0.27 | 0.20 |

| Model | Backbone | Embed Dim | Accuracy ± SD | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProtoNet | ResNet-18 | 32 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| ProtoNet | ResNet-18 | 64 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| ProtoNet | CNN | 32 | 0.55 ± 0.11 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.52 |

| ProtoNet | CNN | 64 | 0.45 ± 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.38 |

| Fine-tuned ResNet-50 | ResNet-50 | — | 0.42 ± 0.12 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| Image-Prototype (ZSL) | ResNet-50 | — | 0.54 ± 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.52 |

| CLIP (Radiology Prompt) | ViT-B/32 | — | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| Model | Normal (TP) | Glioma (TP) | Meningioma (TP) | Pituitary (TP) | Key Misclassification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProtoNet R18/32 | 211 | 169 | 152 | 164 | glioma meningioma |

| ProtoNet R18/64 | 189 | 195 | 131 | 185 | meningioma was frequently confused with normal (57) and glioma (69) |

| ProtoNet CNN/32 | 156 | 131 | 129 | 127 | High uniform misclassification across all tumor types |

| Variable | Setting | Accuracy ± SD | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embedding Dim | 32 → 64 (ResNet-18) | 0.85 → 0.85 (± 0.08) | 0.84 → 0.85 |

| Backbone | CNN → ResNet-18 → ViT | 0.55 → 0.85 → 0.68 | 0.52 → 0.85 → 0.66 |

| Prompt Type | Simple → Radiology | 0.26 → 0.30 | 0.19 → 0.23 |

| Model | Marker | Performance Summary | Key Classes/T PR |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProtoNet R18/32 (FSL) | Blue Square | Superior performance. Consistently achieves the highest TPR at low FPR. | Strongest for glioma and normal (highest points in top left). |

| ProtoNet R18/64 | Purple Circle | Strong performance. Nearly matches R18/32, demonstrating high discriminative power. | Very strong for glioma and normal. |

| Finetune ResNet50 (Baseline) | Yellow Triangle | Moderate performance. Better than random, but significantly lower than ProtoNet models. | Moderate for normal and pituitary (TPR). |

| Image-Proto (ZSL) | Red Diamond | Moderate/weak performance. Points cluster near the center. | Weakest discrimination for meningioma, close to the random guess line. |

| CLIP (Radiology Prompt) | Black “X” | Suboptimal performance. Lowest overall performance. | All classes are clustered near the random guess line (TPR typically). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Das, A.; Singh, S. Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning for MRI Brain Tumor Classification Using CLIP and Vision Transformers. Sensors 2025, 25, 7341. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237341

Das A, Singh S. Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning for MRI Brain Tumor Classification Using CLIP and Vision Transformers. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7341. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237341

Chicago/Turabian StyleDas, Abir, and Saurabh Singh. 2025. "Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning for MRI Brain Tumor Classification Using CLIP and Vision Transformers" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7341. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237341

APA StyleDas, A., & Singh, S. (2025). Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning for MRI Brain Tumor Classification Using CLIP and Vision Transformers. Sensors, 25(23), 7341. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237341