Analysis of Deep-Learning Methods in an ISO/TS 15066–Compliant Human–Robot Safety Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A body-part-aware RGB-D safety framework aligned with ISO/TS 15066. We introduce a human–robot–safety framework (HRSF) that uses deep learning to estimate the 3D locations of individual human body parts and maps them to the body-part-specific safety limits specified in ISO/TS 15066. In contrast to existing whole-body detection approaches, the framework enables differentiated separation distances that reflect the varying biomechanical tolerances of different human regions.

- A systematic comparison of deep learning architectures for safety-critical spatial perception. We benchmark multiple state-of-the-art RGB-D models for body and body part localization with respect to accuracy, robustness, latency, and failure modes—metrics that have rarely been evaluated together in prior vision-based human–robot collaboration (HRC) safety work. This analysis supports a more realistic assessment of whether body part granularity can meaningfully improve safety-aware robot motion.

- A dynamic velocity-adaptation scheme based on body part proximity. We implement and evaluate a separation-monitoring controller that adjusts robot velocity according to the nearest detected body part and its corresponding ISO/TS 15066 threshold. This differentiates our work from existing RGB-D safety systems that rely on uniform safety margins and cannot exploit less conservative limits when nonsensitive body regions are closest.

- Experimental validation in a real collaborative manufacturing scenario. Using a KUKA LBR iiwa 7-DOF robot (KUKA AG, Augsburg, Germany) we demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed framework in a representative screwing task and measured the operational impact of body-part-aware velocity regulation. Although limited in subject number, task diversity, and repetitions, these experiments provide initial evidence for how fine-grained human perception can influence cycle time under real processing latencies.

2. Safety Aspects According to ISO/TS 15066

- Safety-rated monitored stop.

- Hand guiding.

- Speed and separation monitoring (SSM).

- Power and force limiting (PFL).

3. Localization of Humans and Human Body Parts in the Workspace

3.1. Relevant Deep Learning Approaches

3.1.1. Human Body Recognition

3.1.2. Human Body Segmentation

3.1.3. Human Pose Estimation

3.1.4. Human Body Part Segmentation

3.2. Selected Deep Learning Approaches

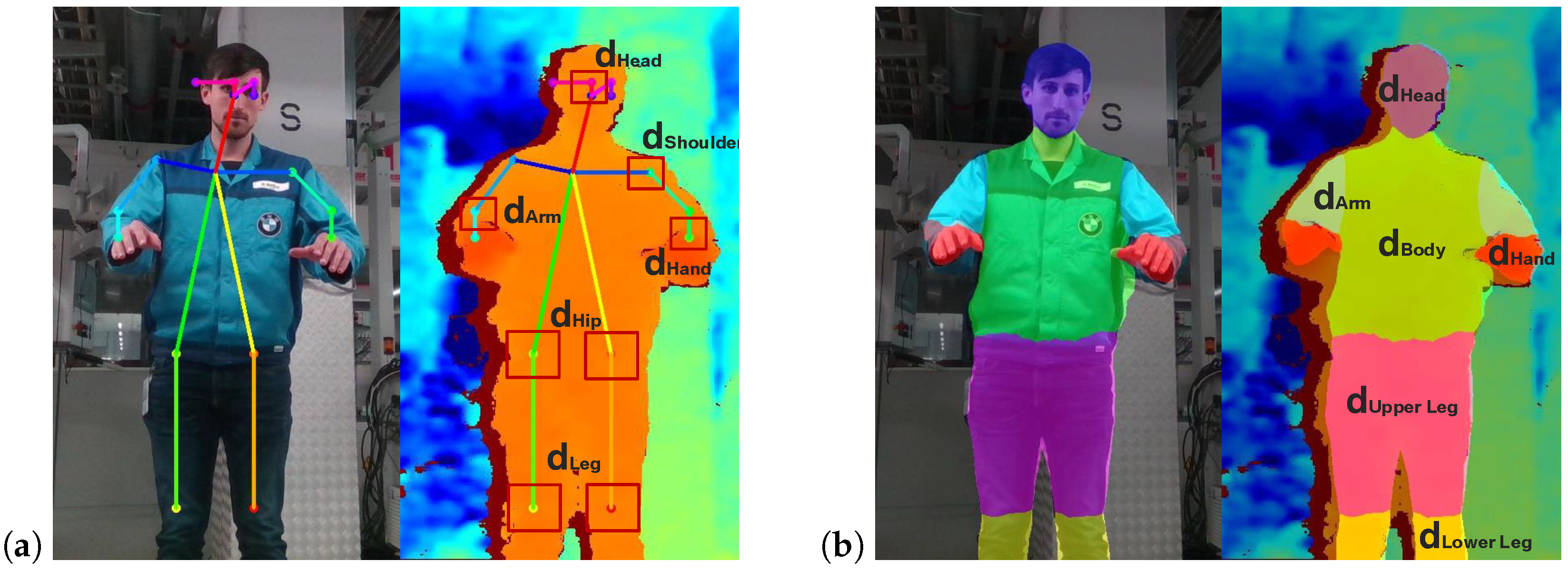

3.3. Extraction of Depth Information

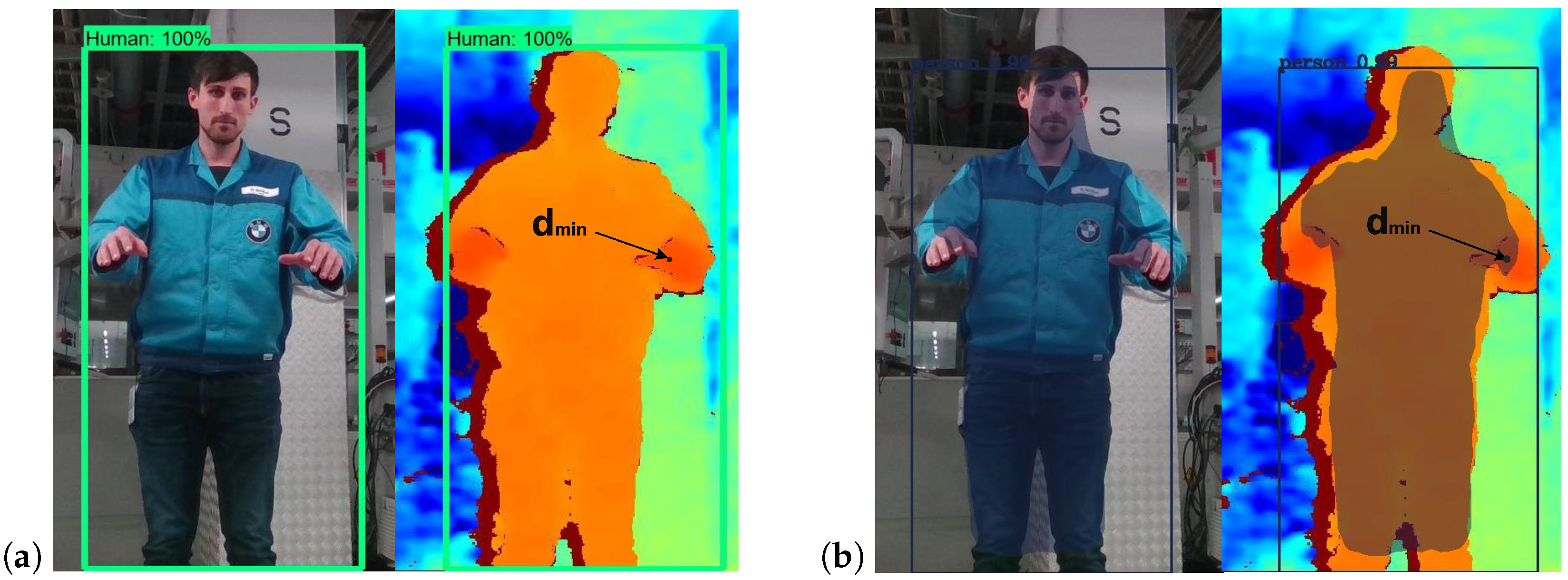

- A

- Determination of the minimal separation distance of the closest body point to a hazardous area.

- B

- Determination of the separation distance for individual body parts.

3.3.1. Minimal Separation Distance for a Single Body Point

3.3.2. Separation Distance for Individual Body Parts

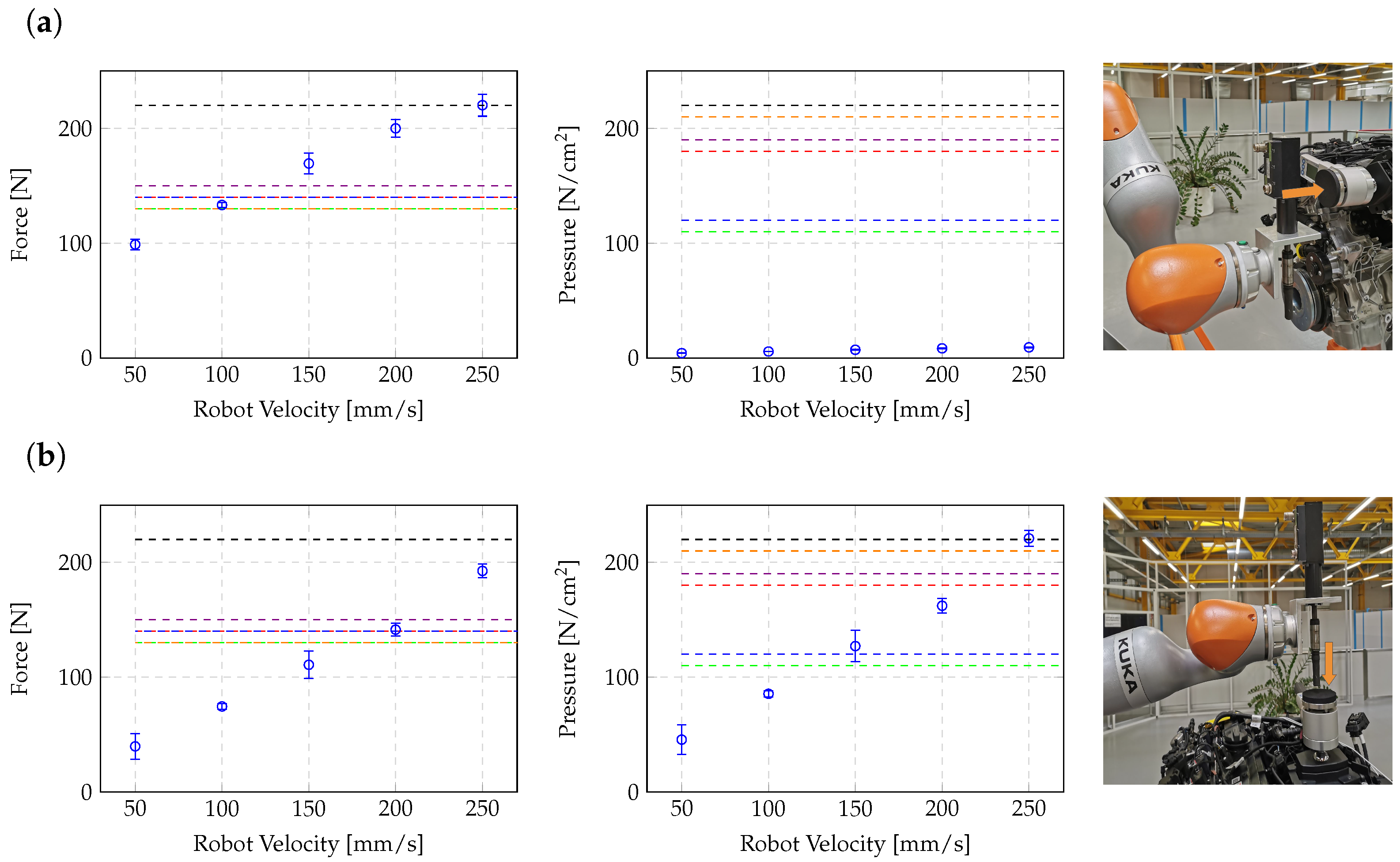

4. Determination of ISO-Relevant Safety Parameters for Specific Robotic Systems

4.1. Minimum Separation Distance

4.1.1. Distance Due to Human Motion

4.1.2. Position Prediction Uncertainty

4.1.3. Intrusion Distance C

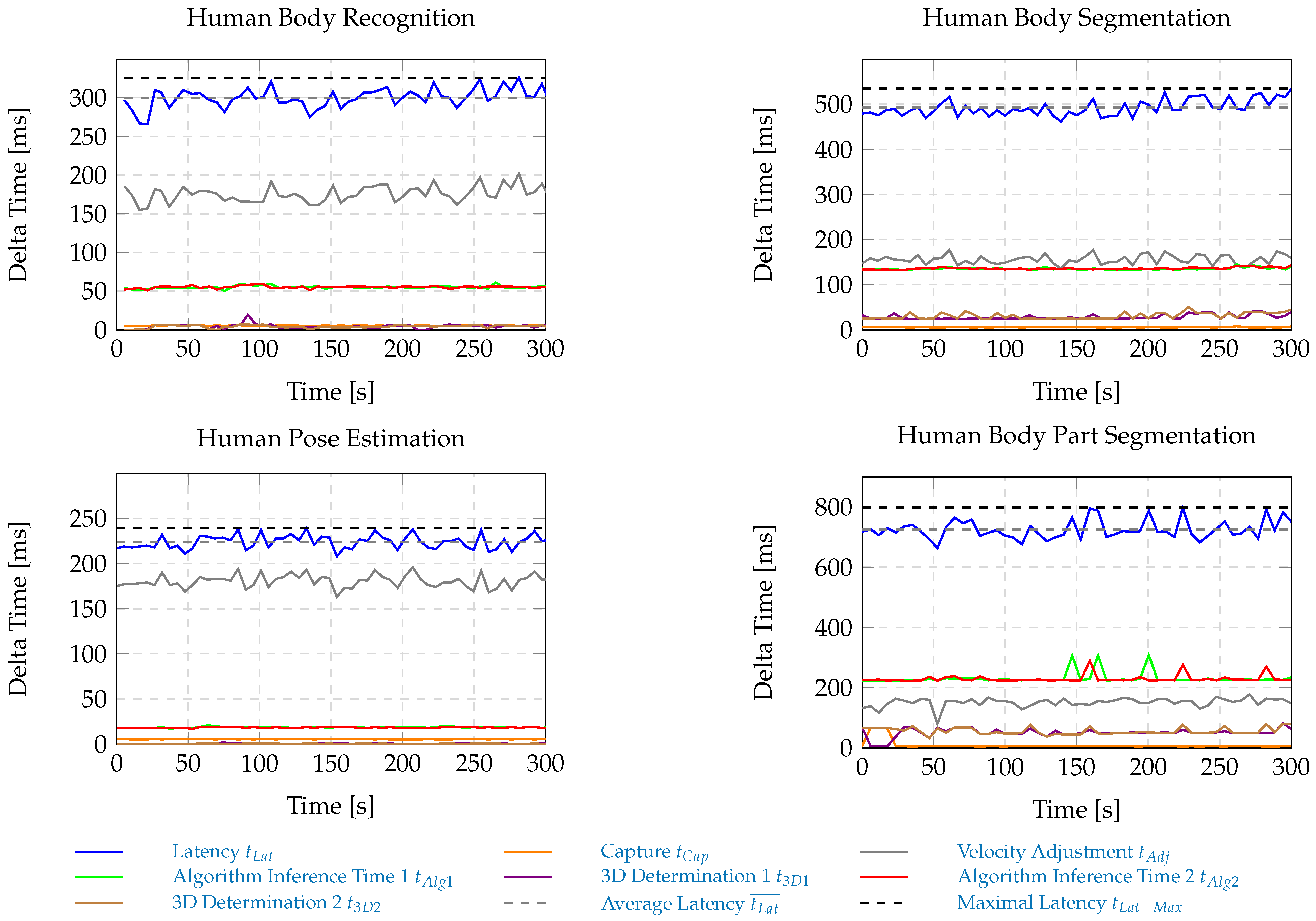

4.1.4. Robot Latency Contribution

4.1.5. Robot Positioning Uncertainty

4.2. Maximum Robot Velocities

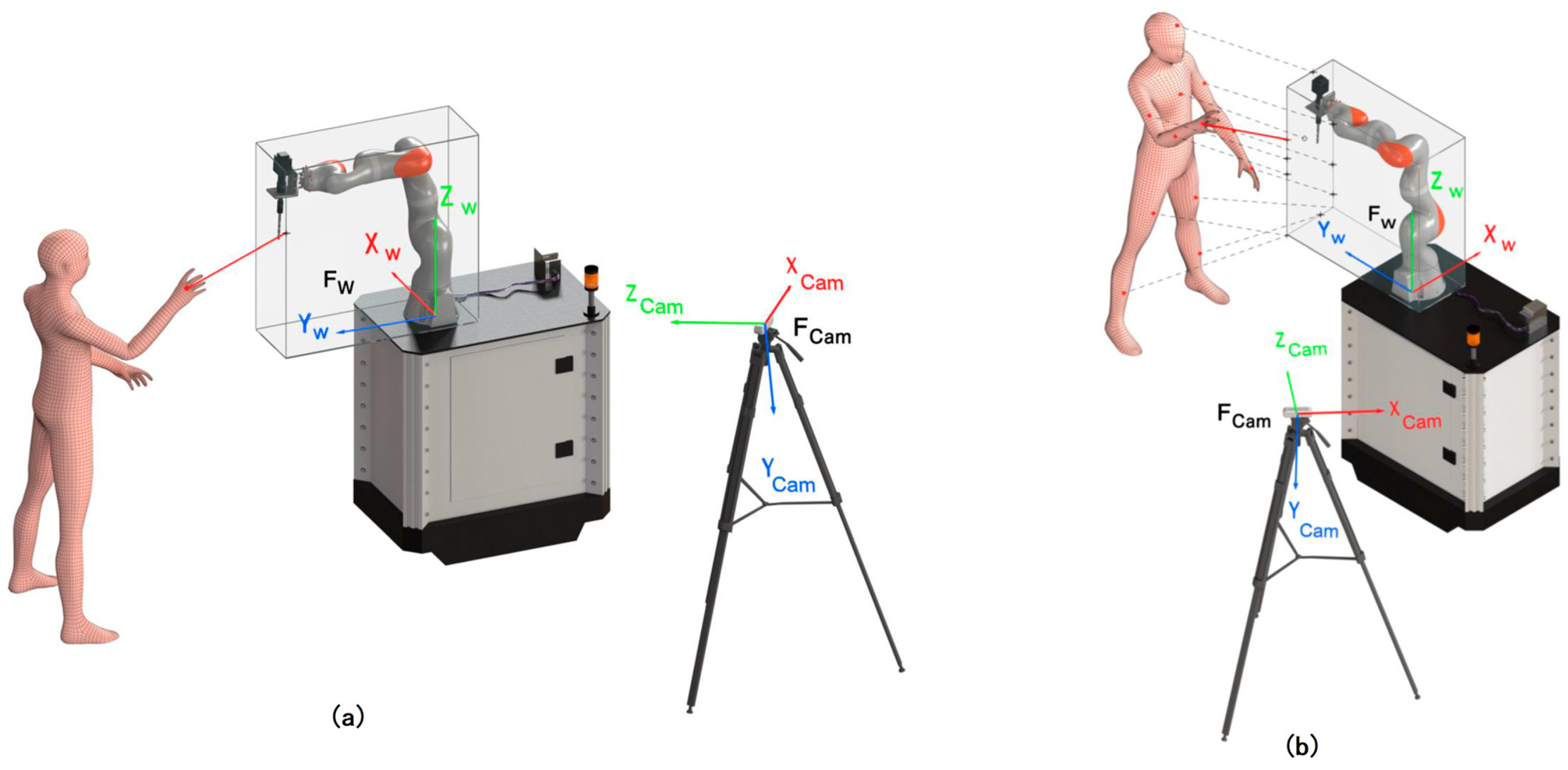

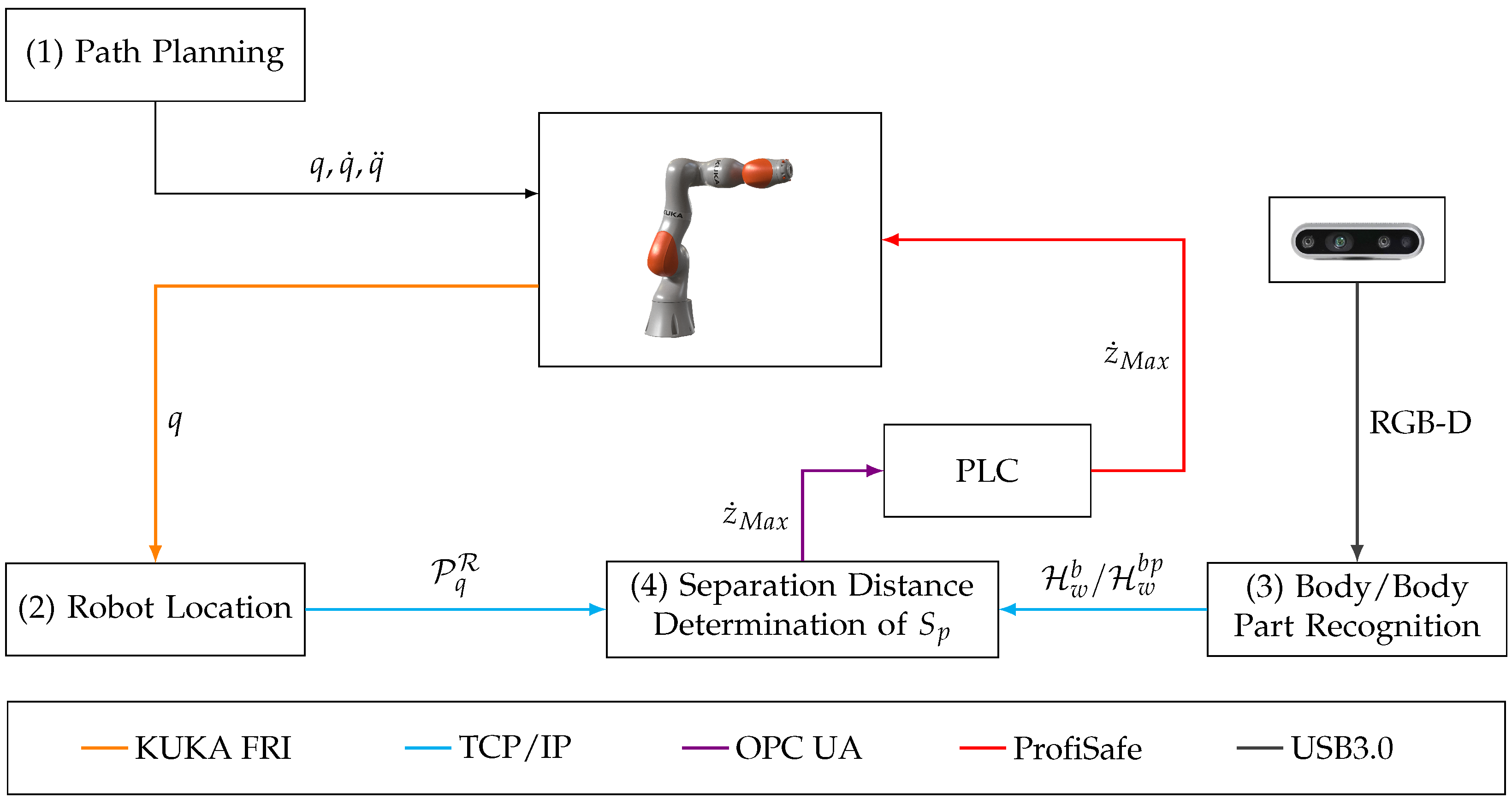

5. The Human–Robot–Safety Framework

6. Experimental Validation

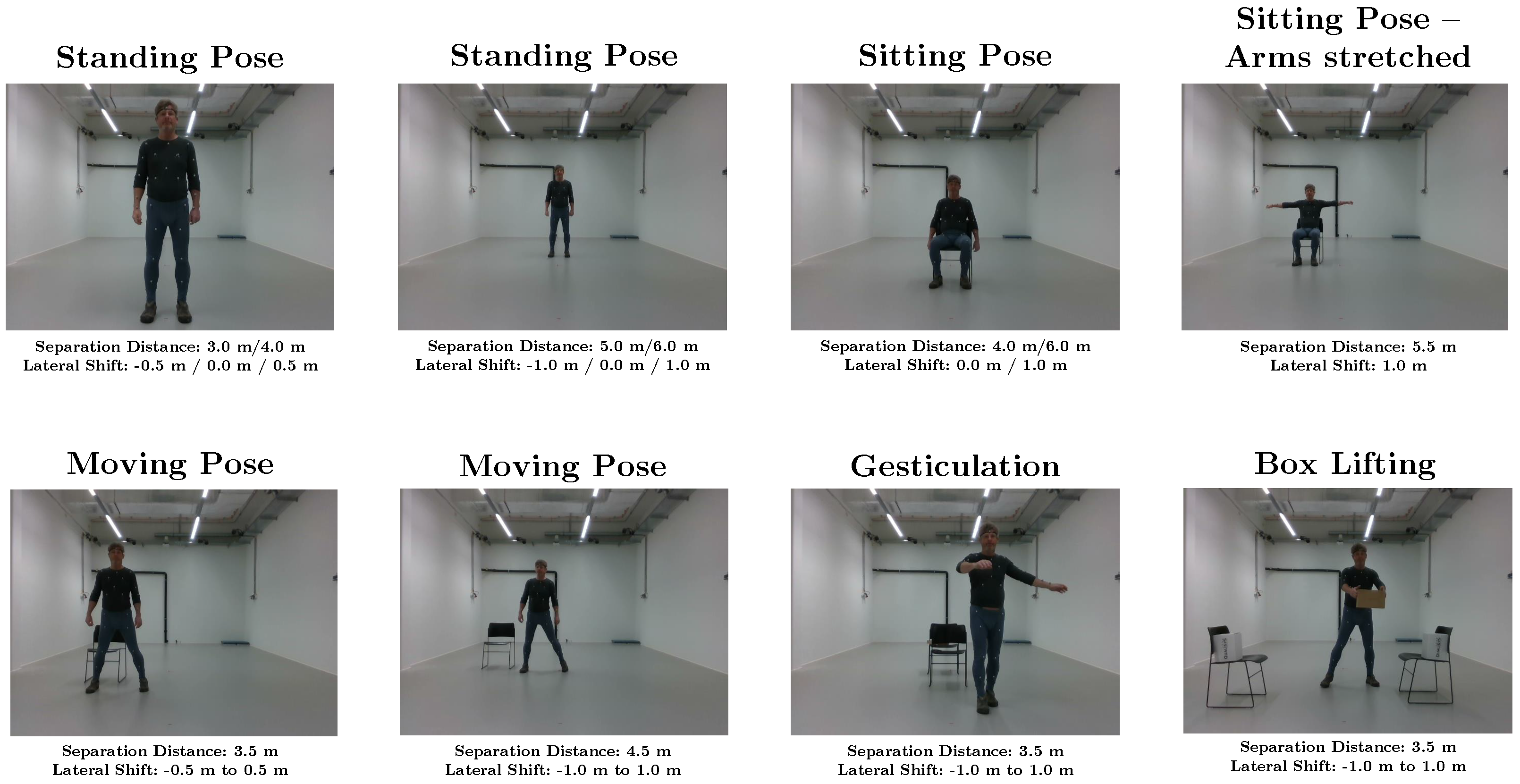

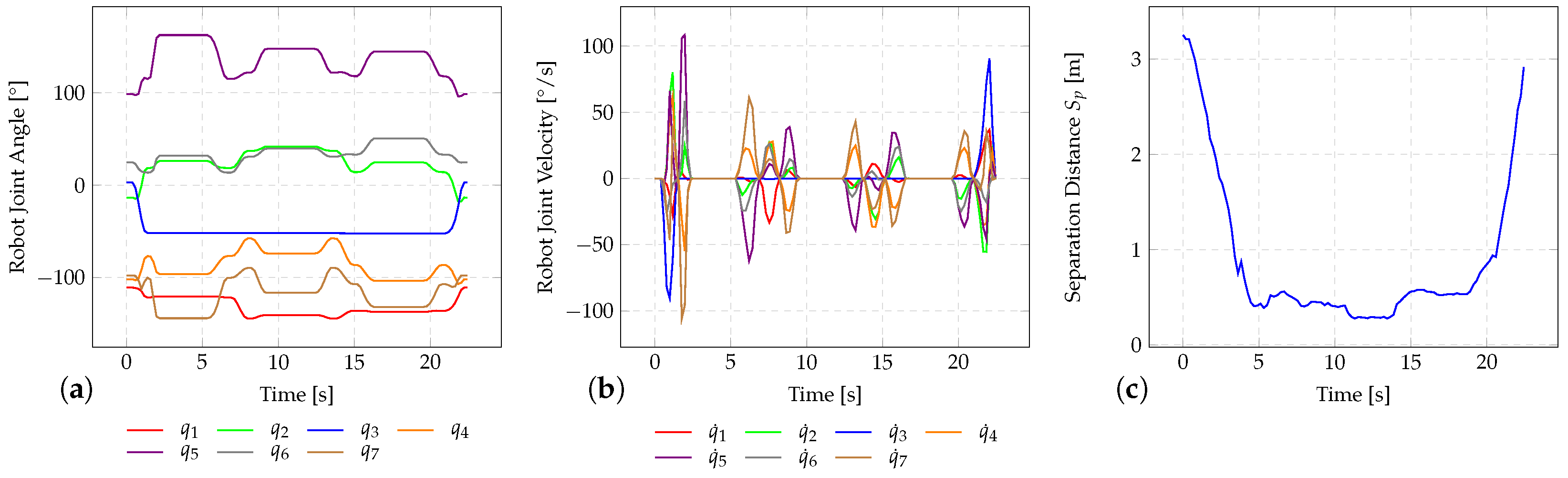

6.1. Test Scenario

- Coexistence: Human and robot are located far away from each other but are both heading towards the engine block.

- Collaboration: Human and robot work are at the same work piece on different workings tasks. At this stage, collisions are rather likely to occur, and thus the robot must be operated with decreased velocities.

- Cooperation: After finishing all working tasks at the engine block, the operator carries out other tasks in the common workspace. At this stage, collisions between human and robot are rather unlikely.

6.2. Speed Adjustment

6.3. Cycle Time Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Standing poses | ||||||||

| Distance | Human Body Recognition | Human Body Segmentation | ||||||

| to Camera | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| [m] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| 2.5 | −7 ± 50 | −23 ± 137 | −134 ± 130 | 0 | −7 ± 50 | −21 ± 136 | −132 ± 126 | 0 |

| 3.0 | 7 ± 45 | −76 ± 11 | −155 ± 188 | 0 | 8 ± 43 | −68 ± 111 | −132 ± 149 | 0 |

| 4.0 | −14 ± 87 | −205 ± 63 | −25 ± 155 | 0 | −138 ± 86 | −202 ± 55 | −238 ± 124 | 0 |

| 5.0 | −236 ± 104 | −154 ± 224 | −47 ± 429 | 0 | −192 ± 78 | −99 ± 172 | −273 ± 226 | 0 |

| 6.0 | 18 ± 78 | −28 ± 107 | −19 ± 244 | 0 | 48 ± 59 | −242 ± 73 | −164 ± 183 | 0 |

| Sitting poses | ||||||||

| Distance | Human Body Recognition | Human Body Segmentation | ||||||

| to Camera | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| [m] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| 4.0 | 35 ± 43 | 172 ± 168 | −17 ± 163 | 0 | 52 ± 28 | 184 ± 149 | −108 ± 87 | 0 |

| 5.5 (Arms stretched) | −248 ± 67 | 221 ± 124 | −22 ± 75 | 0 | −215 ± 44 | 226 ± 102 | −196 ± 71 | 0 |

| 6.0 | −17 ± 93 | 249 ± 102 | −294 ± 9 | 0 | −3 ± 88 | 259 ± 91 | −279 ± 84 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Recognition | Human Body Segmentation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pose | to Camera | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| [m] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | |

| Moving from left to right | 3.5 | 88 ± 49 | −18 ± 357 | 272 ± 497 | 3 | 154 ± 289 | −19 ± 367 | 283 ± 494 | 0 |

| Moving from left to right | 4.5 | 195 ± 219 | 363 ± 387 | −5 ± 25 | 0 | 212 ± 97 | 374 ± 396 | 51 ± 179 | 0 |

| Moving from left to right | 5.5 | −274 ± 1173 | −4 ± 543 | −135 ± 333 | 7 | 69 ± 83 | 16 ± 564 | −4 ± 183 | 0 |

| Gesticulation of hands and feet | 4.0 | 472 ± 422 | −291 ± 488 | −13 ± 283 | 1 | 567 ± 303 | −325 ± 456 | −51 ± 278 | 0 |

| Box Lifting | 3.5 | −112 ± 948 | −537 ± 601 | −317 ± 312 | 7 | 286 ± 391 | −53 ± 545 | −7 ± 139 | 0 |

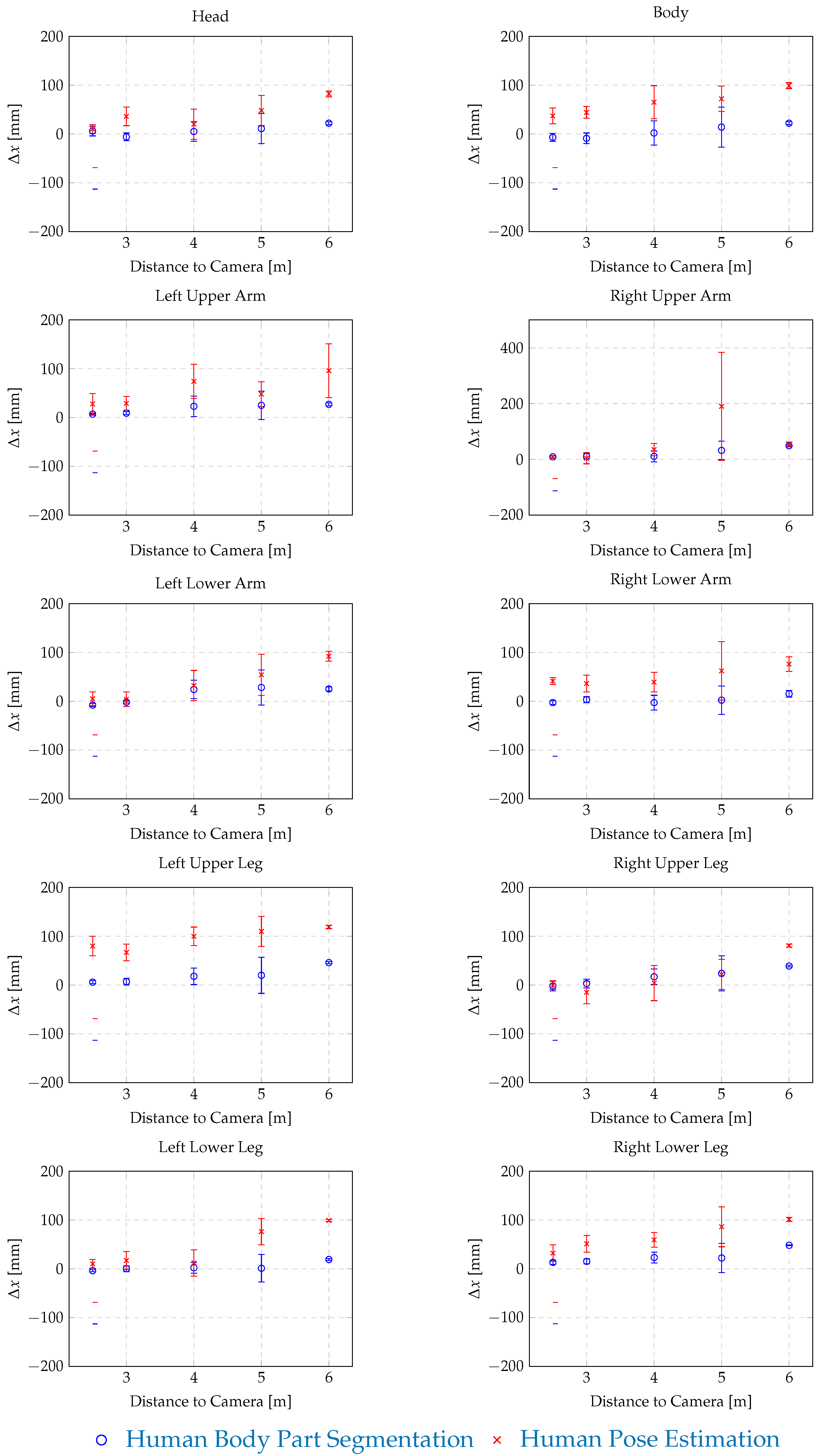

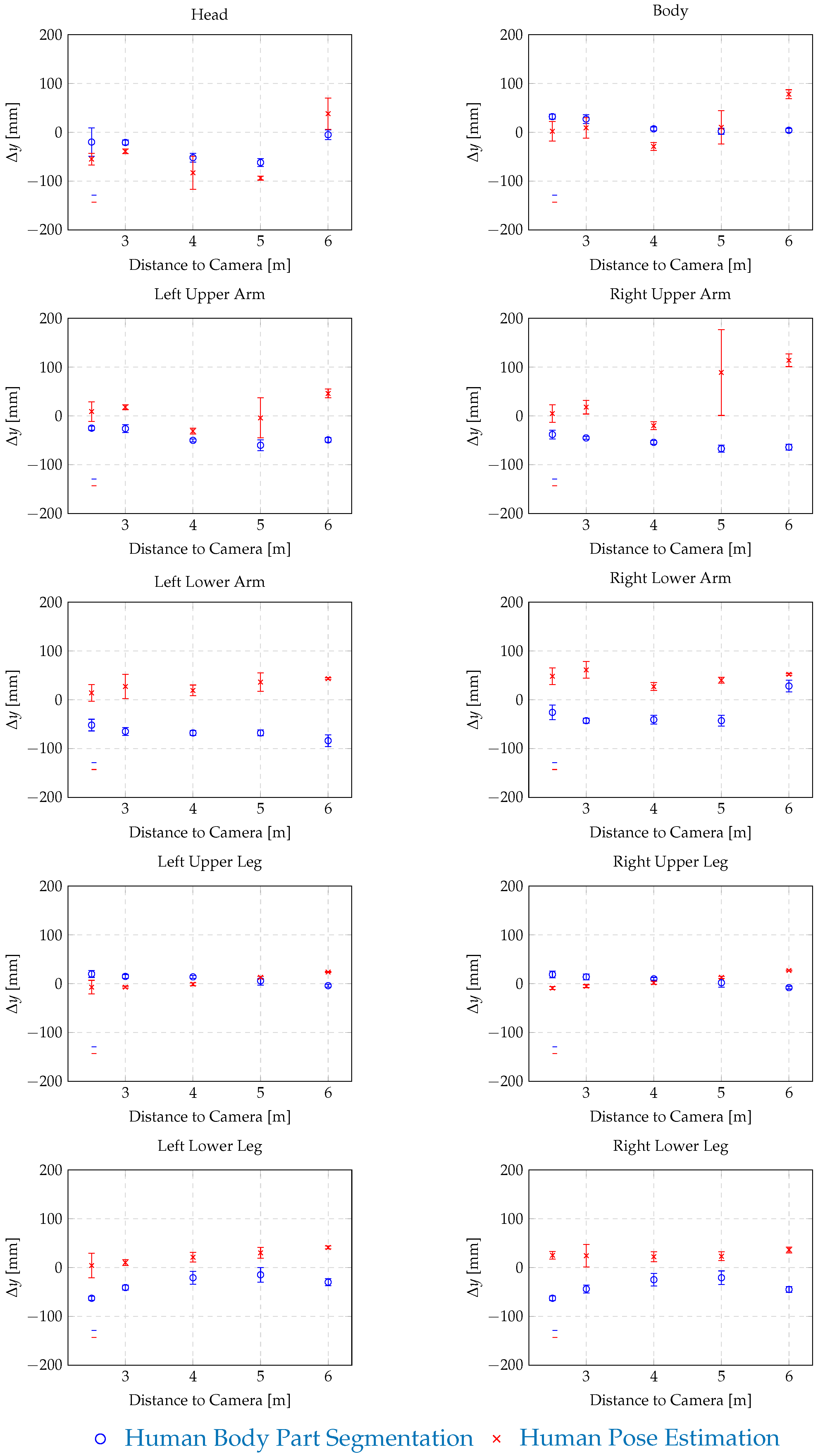

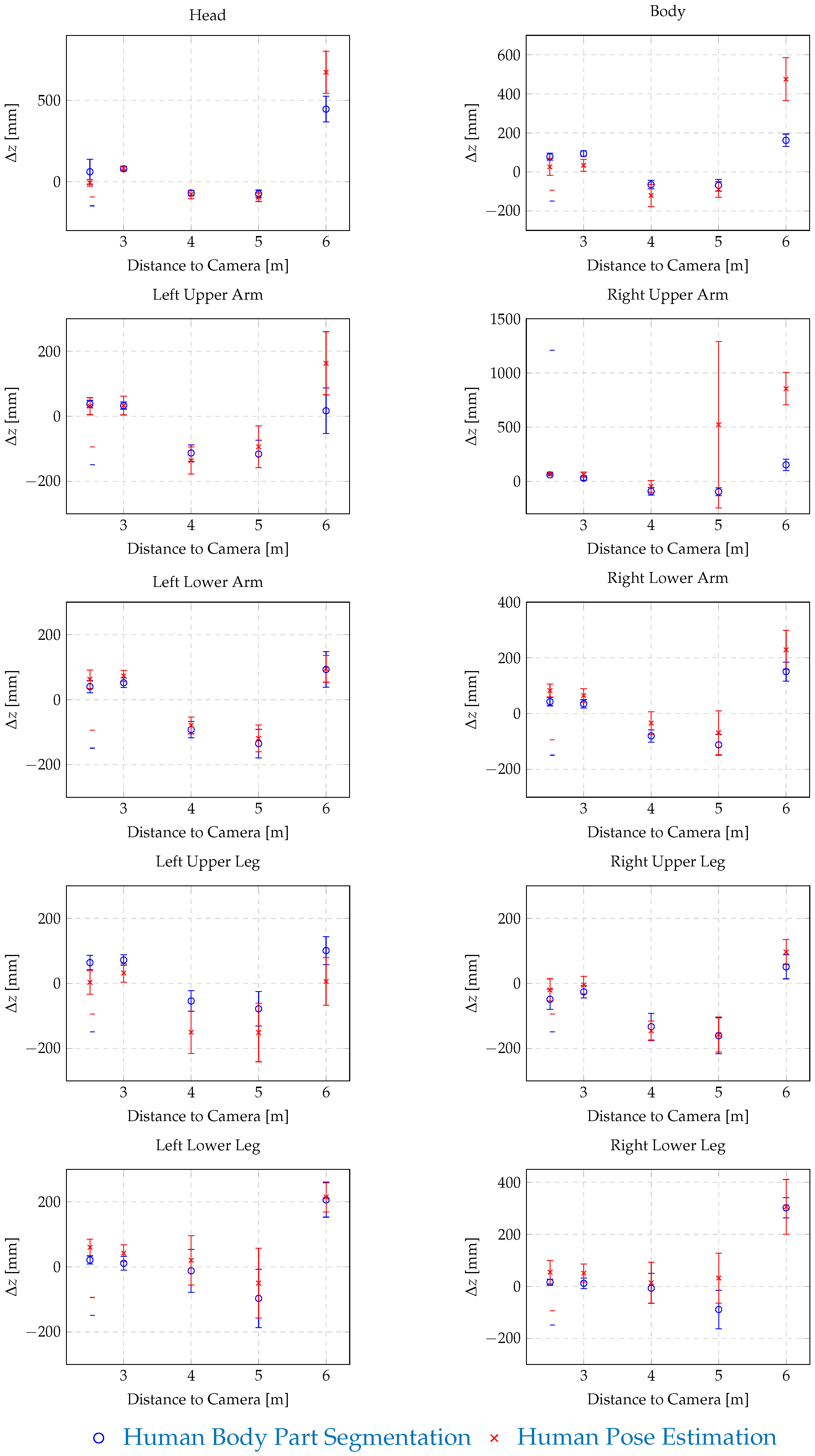

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 2.5 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 61 ± 76 | 6 ± 10 | −20 ± 29 | 0 | −7 ± 21 | 10 ± 9 | −55 ± 12 | 0 |

| Body | 78 ± 18 | −7 ± 8 | 32 ± 5 | 0 | 26 ± 44 | 37 ± 16 | 2 ± 20 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | 38 ± 11 | 7 ± 2 | −25 ± 4 | 0 | 31 ± 26 | 28 ± 21 | 9 ± 20 | 1 |

| Right Upper Arm | 59 ± 9 | 9 ± 3 | −38 ± 9 | 0 | 67 ± 17 | 9 ± 5 | 5± 18 | 31 |

| Left Lower Arm | 40 ± 19 | −8 ± 3 | −52 ± 12 | 0 | 63 ± 28 | 5 ± 14 | 14 ± 17 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | 43 ± 15 | −3 ± 4 | −26 ± 15 | 0 | 83± 23 | 41 ± 7 | 48 ± 17 | 0 |

| Left Upper Leg | 64 ± 22 | 6 ± 3 | 20 ± 7 | 0 | 3± 36 | 80 ± 20 | −7 ± 14 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −49 ± 31 | −2 ± 10 | 19 ± 7 | 0 | −20 ± 34 | 0 ± 9 | −9 ± 3 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | 21 ± 12 | −4 ± 2 | −63 ± 4 | 0 | 60 ± 25 | 10 ± 9 | 4 ± 25 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 16 ± 12 | 13 ± 4 | −63 ± 5 | 0 | 55 ± 45 | 32± 17 | 25 ± 8 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 3.0 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 79 ± 13 | −6 ± 8 | −21 ± 5 | 0 | 83 ± 14 | 36 ± 19 | −39 ± 5 | 0 |

| Body | 94 ± 14 | −9 ± 11 | 27 ± 9 | 0 | 34 ± 31 | 44 ± 12 | 9 ± 21 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | 33 ± 11 | 9 ± 3 | −26 ± 8 | 0 | 33 ± 29 | 29 ± 14 | 18 ± 5 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | 29 ± 20 | 11 ± 10 | −45 ± 3 | 0 | 61 ± 25 | 4 ± 20 | 18 ± 14 | 0 |

| Left Lower Arm | 52 ± 15 | −2 ± 2 | −65 ± 8 | 0 | 73 ± 17 | 4 ± 15 | 27 ± 25 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | 35 ± 15 | 3 ± 6 | −43 ± 5 | 0 | 65± 24 | 36 ± 17 | 61 ± 17 | 1 |

| Left Upper Leg | 72 ± 16 | 7 ± 7 | 15 ± 4 | 0 | 32 ± 28 | 67 ± 17 | −7 ± 2 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −26 ± 19 | 3 ± 9 | 14 ± 6 | 0 | −5 ± 27 | −15 ± 23 | −5 ± 3 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | 11 ± 21 | 0 ± 6 | −41 ± 5 | 0 | 42 ± 26 | 17 ± 18 | 10 ± 6 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 12 ± 20 | 15 ± 5 | −44 ± 8 | 0 | 51 ± 35 | 51 ± 17 | 24± 23 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 4.0 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | −70 ± 15 | 5 ± 20 | −52 ± 9 | 0 | −79 ± 26 | 20 ± 31 | −83 ± 34 | 0 |

| Body | −65 ± 22 | 2 ± 25 | 7 ± 4 | 0 | −121 ± 57 | 65 ± 34 | −29 ± 8 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −113 ± 25 | 23 ± 21 | −50 ± 3 | 0 | −136 ± 42 | 74 ± 35 | −31 ± 6 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | −92 ± 35 | 11 ± 20 | −54± 4 | 0 | −46 ± 54 | 35 ± 22 | −20 ± 8 | 0 |

| Left Lower Arm | −92 ± 25 | 24 ± 19 | −68 ± 5 | 0 | −79 ± 26 | 32 ± 31 | 19 ± 11 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | −80 ± 22 | −3 ± 15 | −41 ± 9 | 0 | −34 ± 41 | 39 ± 20 | 27 ± 8 | 21 |

| Left Upper Leg | −54 ± 32 | 18 ± 17 | 14 ± 3 | 0 | −150 ± 65 | 100 ± 19 | −1 ± 3 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −133 ± 41 | 17± 16 | 10 ± 3 | 0 | −146 ± 30 | 4 ± 36 | 2 ± 3 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | −12 ± 66 | 2 ± 11 | −21 ± 13 | 0 | 20 ± 76 | 12 ± 27 | 21 ± 10 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | −7 ± 57 | 23 ± 11 | −25 ± 13 | 0 | 14 ± 79 | 59 ± 15 | 22 ± 10 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 5.0 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | −75 ± 23 | 11 ± 31 | −62 ± 8 | 0 | −96 ± 26 | 48 ± 31 | −94 ± 4 | 0 |

| Body | −69 ± 30 | 14 ± 41 | 2 ± 6 | 0 | −90 ± 40 | 72 ± 26 | 10 ± 31 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −116 ± 42 | 25 ± 29 | −60 ± 11 | 0 | −94 ± 64 | 48 ± 25 | −4 ± 41 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | −96 ± 36 | 32 ± 33 | −67 ± 7 | 0 | 522 ± 767 | 190 ± 194 | 89 ± 88 | 11 |

| Left Lower Arm | −135 ± 44 | 28 ± 36 | −68 ± 6 | 0 | −119 ± 41 | 54 ± 42 | 36 ± 19 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | −112 ± 38 | 2 ± 29 | −43 ± 11 | 0 | −69 ± 79 | 62 ± 60 | 40 ± 6 | 9 |

| Left Upper Leg | −78 ± 53 | 20 ± 37 | 6 ± 9 | 0 | −151± 90 | 110 ± 31 | 13± 2 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −161 ± 55 | 24 ± 36 | 2 ± 9 | 0 | −157 ± 54 | 22± 31 | 13 ± 2 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | −97 ± 90 | 1 ± 28 | −15 ± 15 | 0 | −50 ± 107 | 76 ± 27 | 30 ± 11 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | −89 ± 74 | 22 ± 30 | −21 ± 14 | 0 | 32 ± 96 | 86 ± 41 | 23 ± 9 | 1 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 6.0 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 446 ± 79 | 22 ± 3 | −5 ± 10 | 0 | 673 ± 129 | 82 ± 6 | 38 ± 32 | 0 |

| Body | 162 ± 32 | 22 ± 3 | 4 ± 4 | 0 | 475 ± 110 | 99 ± 6 | 78 ± 9 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | 17 ± 70 | 27 ± 3 | −49 ± 5 | 0 | 163 ± 97 | 96± 55 | 46 ± 9 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | 152 ± 52 | 49 ± 3 | −64 ± 6 | 0 | 855 ± 149 | 53 ± 9 | 114± 13 | 0 |

| Left Lower Arm | 93 ± 55 | 25 ± 4 | −84 ± 12 | 0 | 95 ± 41 | 92 ± 10 | 43 ± 2 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | 151 ± 34 | 15 ± 7 | 28 ± 12 | 0 | 229 ± 70 | 76± 15 | 52 ± 2 | 0 |

| Left Upper Leg | 101 ± 43 | 46 ± 2 | −4 ± 3 | 0 | 6 ± 73 | 119 ± 3 | 24 ± 1 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | 51 ± 37 | 39 ± 2 | −8 ± 3 | 0 | 97 ± 38 | 81± 3 | 27 ± 1 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | 206 ± 53 | 19 ± 2 | −30 ± 7 | 0 | 215± 46 | 99± 2 | 41 ± 3 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 302 ± 39 | 48 ± 1 | −45 ± 6 | 0 | 306 ± 105 | 101± 4 | 36 ± 6 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 4.0 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | −71 ± 19 | 3 ± 2 | −36 ± 3 | 0 | −49 ± 39 | 29 ± 38 | −66 ± 4 | 0 |

| Body | −40 ± 20 | −3 ± 3 | 34 ± 6 | 0 | −90 ± 43 | 78 ± 2 | −12 ± 3 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −97 ± 31 | 24 ± 2 | −38 ± 3 | 0 | −117 ± 40 | 92 ± 2 | −12 ± 2 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | −12 ± 30 | 30 ± 2 | −69 ± 4 | 0 | 57 ± 58 | 60 ± 4 | −8 ± 3 | 31 |

| Left Lower Arm | −66 ± 19 | 33 ± 3 | −38 ± 3 | 0 | −85 ± 20 | 45 ± 5 | 21 ± 3 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | −53 ± 25 | −17 ± 3 | 7 ± 4 | 0 | 40 ± 35 | 12 ± 6 | 68 ± 7 | 0 |

| Left Upper Leg | −51 ± 12 | 31 ± 3 | −55 ± 1 | 0 | −123 ± 37 | 131 ± 0 | 4 ± 3 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | 180 ± 18 | 21 ± 2 | −52 ± 2 | 0 | 316 ± 20 | 7 ± 1 | 1 ± 2 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | 115 ± 17 | 9 ± 2 | −21 ± 4 | 0 | 129 ± 23 | 29 ± 35 | −58 ± 3 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 65 ± 16 | 6 ± 1 | −22 ± 4 | 0 | 267 ± 80 | 54 ± 6 | −56 ± 25 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 6.0 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 254 ± 53 | 44 ± 10 | −19 ± 5 | 0 | 314 ± 68 | 140 ± 13 | −5 ± 5 | 0 |

| Body | 168 ± 26 | 35 ± 5 | 11 ± 6 | 0 | 210 ± 66 | 148 ± 12 | 45 ± 4 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | 69 ± 56 | 24 ± 7 | −59 ± 2 | 0 | 107 ± 116 | 65 ± 17 | 44 ± 5 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | 239 ± 45 | 99 ± 10 | −57 ± 5 | 0 | 456 ± 132 | 112 ± 27 | 49 ± 4 | 0 |

| Left Lower Arm | 111 ± 33 | 61 ± 5 | −62 ± 5 | 0 | 73 ± 25 | 156 ± 15 | 31 ± 3 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | 144 ± 39 | 21 ± 25 | 34 ± 7 | 0 | 376 ± 68 | 112 ± 14 | 118 ± 4 | 0 |

| Left Upper Leg | 111± 27 | 52 ± 4 | −108± 3 | 0 | 57 ± 26 | 111 ± 4 | −51 ± 2 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | 372 ± 34 | 92± 7 | −101 ± 3 | 0 | 490 ± 30 | 70 ± 6 | −50 ± 2 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | 277 ± 42 | 50 ± 7 | −81 ± 6 | 0 | 320 ± 56 | 114 ± 9 | −96 ± 28 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 94 ± 67 | 36 ± 15 | −65 ± 9 | 0 | 1756 ± 125 | 554 ± 31 | −98± 41 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 5.5 m | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 277 ± 91 | 28 ± 9 | −21 ± 6 | 0 | 223 ± 74 | 55 ± 10 | −43 ± 5 | 0 |

| Body | 147 ± 69 | 11 ± 8 | 33 ± 2 | 0 | 142 ± 75 | 62 ± 8 | 10 ± 2 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | 598 ± 131 | 59 ± 10 | −42 ± 3 | 0 | 133 ± 91 | 99 ± 8 | −29 ± 2 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | 259 ± 133 | 83 ± 20 | −30 ± 2 | 0 | 385 ± 179 | 163 ± 27 | −26 ± 4 | 0 |

| Left Lower Arm | 943 ± 592 | 712 ± 522 | −50 ± 35 | 41 | 1743 ± 366 | 116 ± 72 | 52 ± 24 | 5 |

| Right Lower Arm | 669 ± 224 | 216 ± 108 | −27 ± 5 | 0 | 859 ± 333 | 219 ± 74 | 17 ± 27 | 10 |

| Left Upper Leg | −34 ± 61 | 40 ± 6 | −42 ± 5 | 0 | −56 ± 78 | 50 ± 7 | −18 ± 5 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | 148 ± 51 | 10 ± 7 | −35 ± 4 | 0 | 377 ± 78 | 111 ± 12 | −23 ± 5 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | −13 ± 31 | 18 ± 3 | −15 ± 4 | 0 | 177 ± 57 | 51 ± 4 | −45 ± 5 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | −165 ± 21 | −10 ± 3 | −1 ± 4 | 0 | 154 ± 121 | 120 ± 21 | −44 ± 9 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 3.5 m (Moving) | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 28 ± 70 | 7 ± 47 | −29 ± 28 | 0 | 4 ± 29 | 22 ± 44 | −41 ± 86 | 0 |

| Body | 26 ± 23 | −10 ± 51 | −6 ± 8 | 0 | −31 ± 39 | 33 ± 52 | −15 ± 17 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −25 ± 28 | 28 ± 45 | 10 ± 14 | 0 | −35 ± 32 | 30 ± 51 | −24± 17 | 1 |

| Right Upper Arm | 12 ± 32 | −27 ± 46 | −1 ± 11 | 0 | 21 ± 143 | 6 ± 72 | −15 ± 109 | 2 |

| Left Lower Arm | −4 ± 29 | 8 ± 42 | −24 ± 19 | 0 | 18 ± 35 | 5 ± 46 | 28 ± 17 | 2 |

| Right Lower Arm | 2 ± 27 | −0 ± 43 | 5 ± 16 | 0 | 29 ± 40 | 40 ± 44 | 44 ± 13 | 10 |

| Left Upper Leg | 22 ± 23 | 6 ± 42 | −16 ± 9 | 0 | −23 ± 33 | 54 ± 50 | 5 ± 18 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −69 ± 25 | −6 ± 45 | −29 ± 13 | 0 | −16 ± 53 | −4 ± 58 | 6 ± 66 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | −11 ± 28 | 11 ± 44 | −42 ± 14 | 0 | 9 ± 33 | 17 ± 45 | 27 ± 21 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 0 ± 29 | 5 ± 43 | −53 ± 17 | 0 | 17 ± 43 | 46 ± 45 | 36 ± 20 | 0 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 4.5 m (Moving) | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 34 ± 34 | 14 ± 40 | −26 ± 14 | 0 | 24 ± 35 | 32 ± 42 | −53 ± 15 | 0 |

| Body | 29 ± 39 | −5 ± 42 | −13 ± 9 | 0 | −46 ± 55 | 47 ± 46 | −7 ± 27 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −30 ± 47 | 25 ± 38 | −4 ± 10 | 0 | −39 ± 54 | 53 ± 45 | −24 ± 28 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | 6 ± 48 | −12 ± 38 | −17 ± 9 | 0 | 55 ± 157 | 34 ± 65 | −6 ± 33 | 7 |

| Left Lower Arm | −6 ± 50 | 10 ± 37 | −61 ± 13 | 3 | 21 ± 67 | 24 ± 44 | 18 ± 20 | 1 |

| Right Lower Arm | 11 ± 57 | 8 ± 37 | −22 ± 19 | 2 | 35 ± 71 | 58 ± 42 | 34 ± 28 | 23 |

| Left Upper Leg | 33 ± 43 | 14 ± 32 | −30 ± 10 | 0 | −25 ± 61 | 68 ± 44 | 4 ± 7 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −46 ± 43 | −3 ± 32 | −44 ± 15 | 0 | 0 ± 71 | 11 ± 47 | 1 ± 8 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | −10 ± 41 | 16 ± 33 | −25 ± 20 | 0 | 34 ± 57 | 34 ± 37 | 29 ± 25 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | 15 ± 40 | 14 ± 33 | −35 ± 20 | 0 | 68 ± 87 | 72 ± 40 | 37 ± 20 | 4 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 5.5 m (Moving) | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | −7 ± 45 | 18 ± 54 | −44 ± 15 | 0 | −16 ± 61 | 54 ± 56 | −87 ± 28 | 0 |

| Body | −29 ± 42 | 5 ± 52 | −27 ± 10 | 0 | −56 ± 68 | 69 ± 56 | 7 ± 25 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −69 ± 126 | 36 ± 45 | −14 ± 16 | 0 | −67 ± 78 | 74 ± 52 | −11 ± 32 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | −1 ± 87 | 0 ± 43 | −36 ± 12 | 1 | 230 ± 438 | 67 ± 108 | 23 ± 53 | 14 |

| Left Lower Arm | −42 ± 94 | 25 ± 44 | −64 ± 14 | 10 | −28 ± 95 | 41 ± 50 | 28 ± 14 | 0 |

| Right Lower Arm | −11 ± 119 | 14 ± 44 | −36 ± 25 | 10 | 103 ± 375 | 80 ± 50 | 27 ± 14 | 15 |

| Left Upper Leg | −20 ± 60 | 24 ± 42 | −41 ± 16 | 0 | −97 ± 84 | 94 ± 54 | 16 ± 11 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −95 ± 73 | 7 ± 43 | −56 ± 18 | 0 | −55 ± 93 | 18 ± 54 | 12 ± 12 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | −56 ± 56 | 23 ± 44 | −22 ± 28 | 0 | −8 ± 93 | 53 ± 50 | 38 ± 16 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | −43 ± 57 | 17 ± 44 | −31 ± 29 | 0 | 100 ± 282 | 85 ± 52 | 33 ± 29 | 4 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 3.5 m (Gesticulation) | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 21 ± 55 | 2 ± 28 | −33 ± 17 | 0 | 11 ± 55 | 21 ± 30 | −49 ± 21 | 0 |

| Body | 9± 50 | −13 ± 42 | −17 ± 11 | 0 | −36 ± 72 | 34 ± 39 | −11 ± 21 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | −30 ± 64 | 17 ± 35 | −17 ± 27 | 0 | −39 ± 72 | 30 ± 38 | −29 ± 24 | 0 |

| Right Upper Arm | 23 ± 155 | −13 ± 38 | −27 ± 27 | 0 | 59 ± 261 | 24 ± 50 | −24 ± 79 | 3 |

| Left Lower Arm | −19 ± 76 | 7 ± 44 | −44 ± 43 | 0 | 19 ± 88 | 19 ± 49 | 13 ± 40 | 5 |

| Right Lower Arm | −20 ± 165 | 2± 55 | −13 ± 78 | 0 | −293 ± 940 | 25 ± 154 | 6 ± 209 | 19 |

| Left Upper Leg | 32 ± 51 | 6 ± 35 | −19 ± 19 | 0 | −25 ± 61 | 55 ± 37 | 4 ± 12 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −63 ± 79 | −18 ± 34 | −27 ± 20 | 0 | −3 ± 91 | −7± 35 | 3 ± 12 | 0 |

| Left Lower Leg | 9 ± 59 | 12 ± 29 | −35 ± 17 | 0 | 27 ± 60 | 18± 36 | 29 ± 24 | 0 |

| Right Lower Leg | −3 ± 75 | −6± 31 | −44 ± 21 | 0 | 37 ± 94 | 47 ± 37 | 35 ± 26 | 4 |

| Distance | Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Pose Estimation | ||||||

| to Camera: | x | y | z | Failed Identifications | x | y | z | Failed Identifications |

| 3.0 m (Lifting) | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] | [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | [%] |

| Head | 38 ± 51 | 12 ± 81 | −6 ± 31 | 0 | 34 ± 56 | 39 ± 55 | −57± 33 | 5 |

| Body | −67 ± 60 | 3 ± 95 | 2 ± 34 | 0 | −32 ± 68 | 51 ± 68 | 23 ± 31 | 0 |

| Left Upper Arm | 1 ± 99 | 39± 92 | −23 ± 31 | 0 | −31 ± 79 | 34 ± 68 | −19± 28 | 1 |

| Right Upper Arm | 151 ± 155 | −39± 113 | −62± 51 | 3 | 283 ± 196 | 46 ± 65 | −11 ± 31 | 6 |

| Left Lower Arm | −41 ± 128 | 49 ± 76 | −49 ± 33 | 0 | 11 ± 92 | 68 ± 71 | −10 ± 33 | 3 |

| Right Lower Arm | −23 ± 155 | −37 ± 97 | −47 ± 38 | 0 | 24 ± 142 | 24 ± 80 | −11 ± 38 | 11 |

| Left Upper Leg | −12 ± 65 | 25 ± 63 | −41± 21 | 0 | −126 ± 138 | 69 ± 73 | 4 ± 22 | 0 |

| Right Upper Leg | −54 ± 96 | −7 ± 73 | −55 ± 23 | 0 | −42 ± 175 | 7 ± 69 | 0 ± 27 | 3 |

| Left Lower Leg | −26 ± 76 | 24 ± 47 | −21 ± 24 | 0 | 36 ± 87 | 57 ± 65 | 42 ± 24 | 1 |

| Right Lower Leg | −18± 84 | −8 ± 54 | −29 ± 23 | 0 | 58 ± 144 | 46± 65 | 37 ± 27 | 3 |

References

- Ogenyi, U.E.; Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Ju, Z.; Liu, H. Physical Human–Robot Collaboration: Robotic Systems, Learning Methods, Collaborative Strategies, Sensors, and Actuators. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 1888–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalos, G.; Makris, S.; Tsarouchi, P.; Guasch, T.; Kontovrakis, D.; Chryssolouris, G. Design Considerations for Safe Human-robot Collaborative Workplaces. Procedia CIRP 2015, 37, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TS 15066:2016; Robots and Robotic Devices—Collaborative Robots. Technical Specification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Halme, R.J.; Lanz, M.; Kämäräinen, J.; Pieters, R.; Latokartano, J.; Hietanen, A. Review of vision-based safety systems for human-robot collaboration. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, M.; Basso, F.; Menegatti, E. Tracking people within groups with RGB-D data. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 2101–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Munaro, M.; Menegatti, E. Fast RGB-D People Tracking for Service Robots. Auton. Robot. 2014, 37, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakis, N.; Maratos, V.; Makris, S. A cyber physical system (CPS) approach for safe human-robot collaboration in a shared workplace. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 56, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.P.; Laursen, T.; Schultz, U.P. Human detection and tracking for collaborative robot applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shotton, J.; Fitzgibbon, A.; Cook, M.; Sharp, T.; Finocchio, M.; Moore, R.; Kipman, A.; Blake, A. Real-time human pose recognition in parts from a single depth image. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Portland, OR, USA, 23–28 June 2013; pp. 1297–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, D.; Sridhar, S.; Sotnychenko, O.; Rhodin, H.; Shafiei, M.; Seidel, H.P.; Theobalt, C. VNect: Real-time 3D human pose estimation with a single RGB camera. ACM Trans. Graph. 2017, 36, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. Realtime multi-person 2D pose estimation using Part Affinity Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7291–7299. [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou, G.; Zhu, T.; Chen, L.C.; Gidaris, S.; Tompson, J.; Murphy, K. PersonLab: Person pose estimation and instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, V.; Bawa, A. Semantic segmentation for safe human-robot collaboration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini, L.; De Magistris, G.; Roveda, L.; Sanguineti, M.; Masia, L. Deep learning for safe human–robot collaboration. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102037. [Google Scholar]

- Petković, T.; Miklić, D. Vision-based safety monitoring for collaborative robotics: A deep learning approach. Sensors 2021, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Flacco, F.; Kroeger, T.; De Luca, A.; Khatib, O. Depth-based human motion tracking for real-time safe robot guidance. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 2710–2716. [Google Scholar]

- Roncone, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Pattacini, U.; Metta, G. Safe and compliant physical human–robot interaction using vision-based tracking. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Haddadin, S.; De Luca, A.; Albu-Schäffer, A. Collision detection, isolation, and identification for robots in human environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), St Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; pp. 3356–3363. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, O. Real-time Obstacle Avoidance for Manipulators and Mobile Robots. Int. J. Rob. Res. 1986, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C. Global path planning using artificial potential fields. In Proceedings of the 1989 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 14–19 May 1989; pp. 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, S. Dynamic Safety Zones in Human Robot Collaboration. In Cooperating Robots for Flexible Manufacturing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, N.; Zucker, M.; Bagnell, A.; Srinivasa, S. CHOMP: Gradient Optimization Techniques for Efficient Motion Planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kalakrishnan, M.; Chitta, S.; Theodorou, E.; Pastor, P.; Schaal, S. STOMP: Stochastic trajectory optimization for motion planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 4569–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Pan, J.; Manocha, D. Real-time optimization-based planning in dynamic environments using GPUs. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6–10 May 2013; pp. 4090–4097. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.S.; Park, C.; Manocha, D. I-Planner: Intention-aware motion planning using learning-based human motion prediction. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Suita, K.; Imai, K.; Ikeda, H.; Sugimoto, N. A failure-to-safety robot system for human-robot coexistence. Rob. Autonom. Syst. 1996, 18, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Hirasawa, Y.; Huang, S.; Umetani, Y.; Suita, K. Human-robot contact in the safeguarding space. IEEE Trans. Mechatronics 1997, 2, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakura, S.; Murakami, T.; Ohnishi, K. An approach to collision detection and recovery motion in industrial robot. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–10 November 1989; pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivaliotis, P.; Aivaliotis, S.; Gkournelos, C.; Kokkalis, K.; Michalos, G.; Makris, S. Power and force limiting on industrial robots for human-robot collaboration. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 59, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Funabora, Y.; Yokoe, K.; Aoyama, T.; Doki, S. Funabot-Sleeve: A Wearable Device Employing McKibben Artificial Muscles for Haptic Sensation in the Forearm. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sahoo, D.; Hoi, S.C. Recent advances in deep learning for object detection. Neurocomputing 2020, 396, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2014), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 346–361. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Yang Fu, C.; Berg, A. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. Scaled-YOLOv4: Scaling Cross Stage Partial Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13029–13038. [Google Scholar]

- Ciresan, D.; Giusti, A.; Gambardella, L.; Schmidhuber, J. Deep Neural Networks Segment Neuronal Membranes in Electron Microscopy Images. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; pp. 2852–2860. [Google Scholar]

- Farabet, C.; Couprie, C.; Najman, L.; LeCun, Y. Learning Hierarchical Features for Scene Labeling. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 1915–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Long, P.; Gu, Y.; Li, W. Recent advances in 3D object detection based on RGB-D: A survey. Displays 2021, 70, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Bolya, D.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, F.; Lee, Y.J. YOLACT++ Better Real-Time Instance Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 1108–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, P.; Shotton, J. Key Developments in Human Pose Estimation for Kinect; Consumer Depth Cameras for Computer Vision, ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Toshev, A.; Szegedy, C. DeepPose: Human Pose Estimation via Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1653–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Ouyang, W.; Li, H.; Wang, X. End-to-End Learning of Deformable Mixture of Parts and Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3073–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, C.; Shen Wei, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. Adversarial PoseNet: A Structure-Aware Convolutional Network for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2017), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1221–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Ouyang, W.; Li, H.; Wang, X. Structured Feature Learning for Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4715–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompson, J.; Jain, A.; LeCun, Y.; Bregler, C. Joint Training of a Convolutional Network and a Graphical Model for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 1799–1807. [Google Scholar]

- En Wei, S.; Ramakrishna, V.; Kanade, T.; Sheikh, Y. Convolutional Pose Machines. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4724–4732. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.S.; Lu, G.; Fang, X.; Xie, J.; Tai, Y.W.; Lu, C. Weakly and Semi Supervised Human Body Part Parsing via Pose-Guided Knowledge Transfer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B., Tuytelaars, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Mottaghi, R.; Liu, X.; Fidler, S.; Urtasun, R.; Yuille, A. Detect What You Can: Detecting and Representing Objects using Holistic Models and Body Parts. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1979–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Rathod, V.; Sun, C.; Zhu, M.; Korattikara, A.; Fathi, A.; Fischer, I.; Wojna, Z.; Song, Y.; Guadarrama, S.; et al. Speed/Accuracy Trade-Offs for Modern Convolutional Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3296–3297. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 13849-1:2015; Safety of Machinery—Safety-Related Parts of Control Systems—Part 1: General Principles for Design. Technical Report; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- IEC 61508:2010; Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems. Technical Report; IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Standard, Parts 1–7.

- Bricher, D.; Müller, A. Analysis of Different Human Body Recognition Methods and Latency Determination for a Vision-based Human-robot Safety Framework According to ISO/TS 15066. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics, ICINCO 2020, Paris, France, 7–9 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO13855; Safety of Machinery—Positioning of Safeguards with Respect to the Approach Speeds of Parts of the Human Body. Specification; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Brandstötter, M.; Komenda, T.; Ranz, F.; Wedenig, P.; Gattringer, H.; Kaiser, L.; Breitenhuber, G.; Schlotzhauer, A.; Müller, A.; Hofbaur, M. Versatile Collaborative Robot Applications Through Safety-Rated Modification Limits. In Proceedings of the Advances in Service and Industrial Robotics; Berns, K., Görges, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 438–446. [Google Scholar]

| Work/Approach | Modality | Standard | Body Part | Dynamic Velocity | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressed | Awareness | Adaptation | Validation | ||

| Industrial safety scanners/light curtains | 2D laser/IR | ISO 13855 | No | No (fixed stop/speed) | Industrial use; no body part tests |

| RGB-D human detection [8,9,10] | RGB-D | None or partial | Whole-body only | Limited; coarse scaling | Laboratory demonstrations; limited safety analysis |

| Skeleton/keypoint tracking [11,12] | RGB/RGB-D | Not aligned with ISO/TS 15066 | Joint-level but not mapped to limits | Rarely implemented | Laboratory tests only |

| DL-based human segmentation for HRC [13,14,15] | RGB-D | Partial references | Region level | Limited/no modulation | Laboratory studies; no latency/failure modes |

| Depth-based SSM [16,17,18] | Depth, 3D sensors | Partially aligned w/ ISO/TS 15066 | Whole-body/coarse regions | Yes, but uniform margins | Strong validation; no body part integration |

| Proposed HRSF (this work) | RGB-D + DL | Explicit ISO/TS 15066 mapping | Yes, per-body-part 3D localization | Yes, part-specific velocity scaling | Real-robot evaluation; accuracy, latency, robustness |

| Detection Algorithm | Method |

|---|---|

| Human Body Recognition | SSD [54] |

| Human Body Segmentation | Mask R-CNN [42] |

| Human Pose Estimation | Deep Pose [45] |

| Human Body Part Segmentation | Human Body Part Parsing [51] |

| Method | ||

|---|---|---|

| [ms] | [mm] | |

| Human Body Recognition | 370 | 592 |

| Human Pose Estimation | 305 | 488 |

| Human Body Segmentation | 559 | 894 |

| Human Body Part Segmentation | 812 | 1299 |

| Method | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|

| [mm] | [mm] | [mm] | |

| Human Body Recognition | 346 | 767 | 399 |

| Human Body Segmentation | 346 | 416 | 334 |

| Human Pose Estimation | 131 | 57 | 206 |

| Human Body Part Segmentation | 87 | 71 | 151 |

| Body Part | [mm/s] |

|---|---|

| Skull/Forehead | 50 |

| Hand/Fingers/Lower Arms | 100 |

| Chest | 100 |

| Upper Arms | 100 |

| Thighs | 200 |

| Lower Legs | 50 |

| Method | [s] |

|---|---|

| Human Body Recognition | 24.84 ± 2.31 |

| Human Body Segmentation | 25.60 ± 0.41 |

| Human Pose Estimation | 22.81 ± 1.17 |

| Human Body Part Segmentation | 22.78 ± 0.37 |

| Laser Scanner | 26.98 ± 0.59 |

| No Additional Safety System | 35.08 ± 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bricher, D.; Müller, A. Analysis of Deep-Learning Methods in an ISO/TS 15066–Compliant Human–Robot Safety Framework. Sensors 2025, 25, 7136. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237136

Bricher D, Müller A. Analysis of Deep-Learning Methods in an ISO/TS 15066–Compliant Human–Robot Safety Framework. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7136. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237136

Chicago/Turabian StyleBricher, David, and Andreas Müller. 2025. "Analysis of Deep-Learning Methods in an ISO/TS 15066–Compliant Human–Robot Safety Framework" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7136. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237136

APA StyleBricher, D., & Müller, A. (2025). Analysis of Deep-Learning Methods in an ISO/TS 15066–Compliant Human–Robot Safety Framework. Sensors, 25(23), 7136. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237136