Research on UAV Autonomous Trajectory Planning Based on Prediction Information in Crowded Unknown Dynamic Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

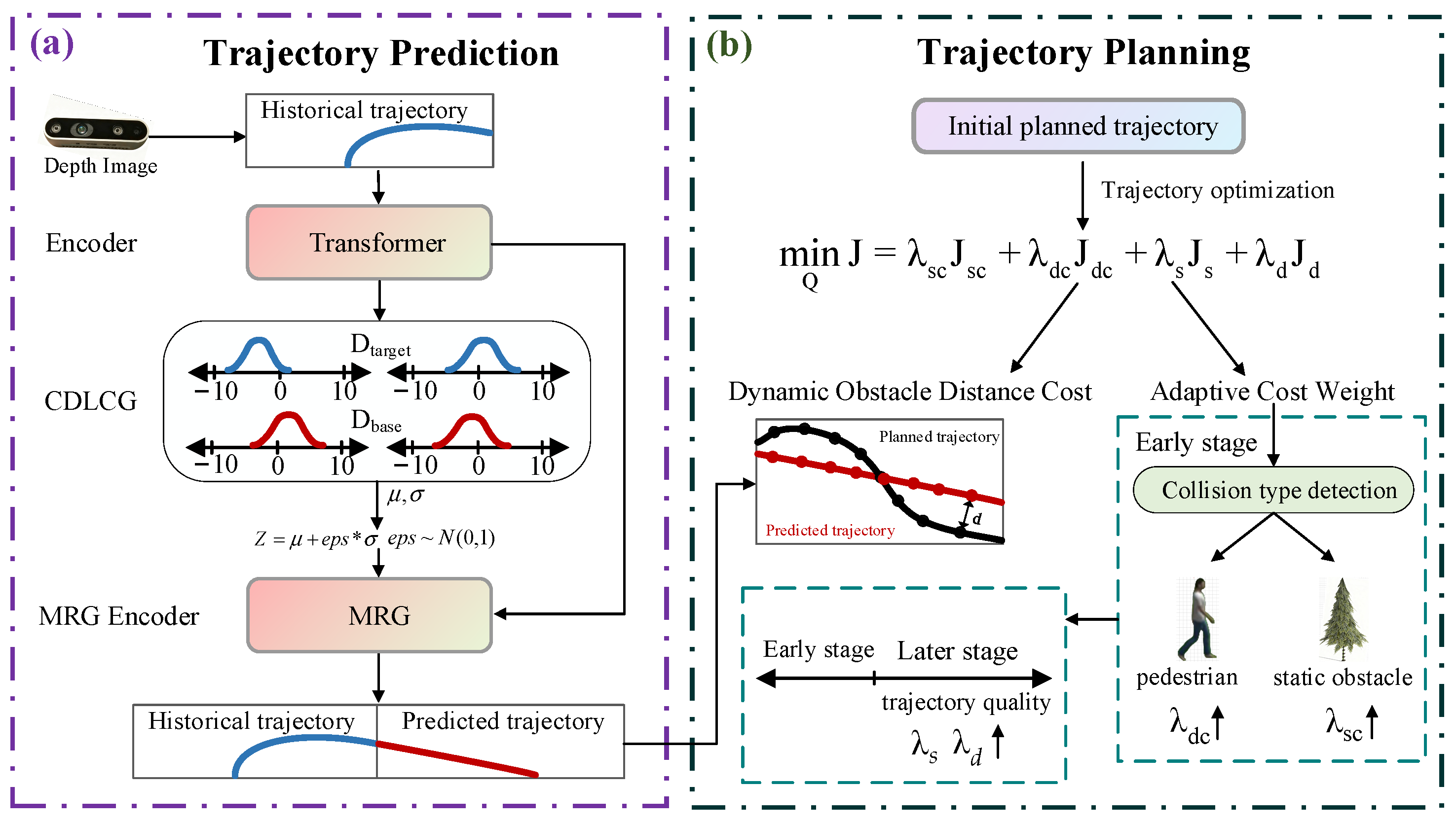

- This paper proposes a Contrastive Distribution Latent Code Generator (CDLCG), whose core innovation lies in guiding the predictive model to learn how to infer appropriate Gaussian distribution parameters from limited historical observation information in practical deployment scenarios. The model samples latent codes based on these distributions to produce a set of candidate prediction trajectories, and then selects optimal trajectories based on probabilistic evaluation.

- This paper proposes an integrated UAV trajectory planning method that combines pedestrian trajectory prediction with gradient-based planning. The method utilizes trajectory prediction techniques to obtain future motion trajectories of dynamic obstacles and integrates this prediction information into the trajectory planning process. Additionally, adaptive cost weights based on optimization stages and obstacle types are designed to achieve adaptive gradient-based trajectory planning.

2. Trajectory Prediction

2.1. Contrastive Distribution Latent Code Generator

2.2. Social Feature Extraction

2.3. Dual Distribution Learning Strategy

2.4. Latent Code Generation

3. Trajectory Planning

3.1. Optimization Problem Formulation

- (1)

- Static Obstacle Distance Cost: The static obstacle distance cost is utilized to ensure that the trajectory’s control points maintain a safe distance from static obstacles. The construction method of the distance cost function is adopted from the referenced literature [19]. For each control point , the distance to the nearest obstacle surface is defined as , and the cost function takes a piecewise form:where is the safety distance threshold, and . is the static obstacle distance cost generated by . When the control point is sufficiently far from obstacles ( > ), no penalty is incurred; when the control point is within the safety distance (), the cost increases smoothly; when the control point enters the obstacle (), the cost increases rapidly. When multiple obstacles exist around a control point, the static obstacle distance cost generated by is , where is the number of pairs for . The total static obstacle distance cost is:The gradient information for optimization can be obtained by taking the derivative of with respect to [20].

- (2)

- Dynamic Obstacle Distance Cost: When pedestrians are detected, this paper integrates the predicted pedestrian trajectory information from the prediction model into local planning. This method not only accounts for the current positions of dynamic obstacles but also considers their potential future movement patterns, enabling proactive collision avoidance. Accordingly, a dynamic obstacle distance cost function is designed to incorporate the future motion trajectories of dynamic obstacles. First, the B-spline trajectory is divided into M consecutive time segments, with each segment storing all predicted positions of pedestrian within that time interval. The m-th time segment corresponds to the time interval , where and , with being the time step. Second, the predicted trajectory of pedestrian is temporally mapped to each time segment, constructing the segmented prediction set:which represents the collection of all predicted positions and time points of pedestrian within the m-th time segment. Third, K time instants are uniformly sampled within the m-th time segment. For each sampled instant , the UAV trajectory position is computed via the B-spline, and the corresponding pedestrian position is retrieved from the prediction set. If no prediction data exists at that instant, linear interpolation between adjacent predicted points is performed to ensure temporal continuity. Finally, the distance between the UAV and the pedestrian at instant is calculated as:where is half the width of the pedestrian. The cost function takes a piecewise form:where is the safety distance threshold, and . is the dynamic obstacle distance cost generated by pedestrian at instant . When the UAV is sufficiently far from obstacles, no penalty is incurred; when the UAV is within the safety distance, the cost increases smoothly; when the UAV enters the obstacle, the cost increases rapidly. The total dynamic obstacle distance cost generated by pedestrian across all time segments is:The aggregate dynamic obstacle distance cost for all pedestrians is:where N is the number of detected pedestrians.

- (3)

- Smoothness Cost: To ensure the physical feasibility of the predicted trajectory, we implement smoothness constraints by minimizing the high-order derivatives (acceleration) of the trajectory [21,22]. The smoothness cost is:where is the acceleration of control point . The gradient for optimization can be obtained by taking the derivative of with respect to .

- (4)

- Feasibility Cost: The construction method of the feasibility cost function is adopted from the referenced literature [19]. To ensure the trajectory conforms to kinematic constraints, the feasibility cost is:where , , , are the corresponding weight coefficients, and F(·) is a twice continuously differentiable metric function of higher order derivatives of control points.where , are chosen to meet the second-order continuity, is the derivative limit, is the splitting points of the quadratic interval and the cubic interval is an elastic coefficient with to make the final results meet the constraints, since the cost function is a tradeoff of all weighted terms [19]. The gradient for optimization can be obtained by taking the derivative of with respect to .

3.2. Adaptive Cost Weight

4. Experiment Results

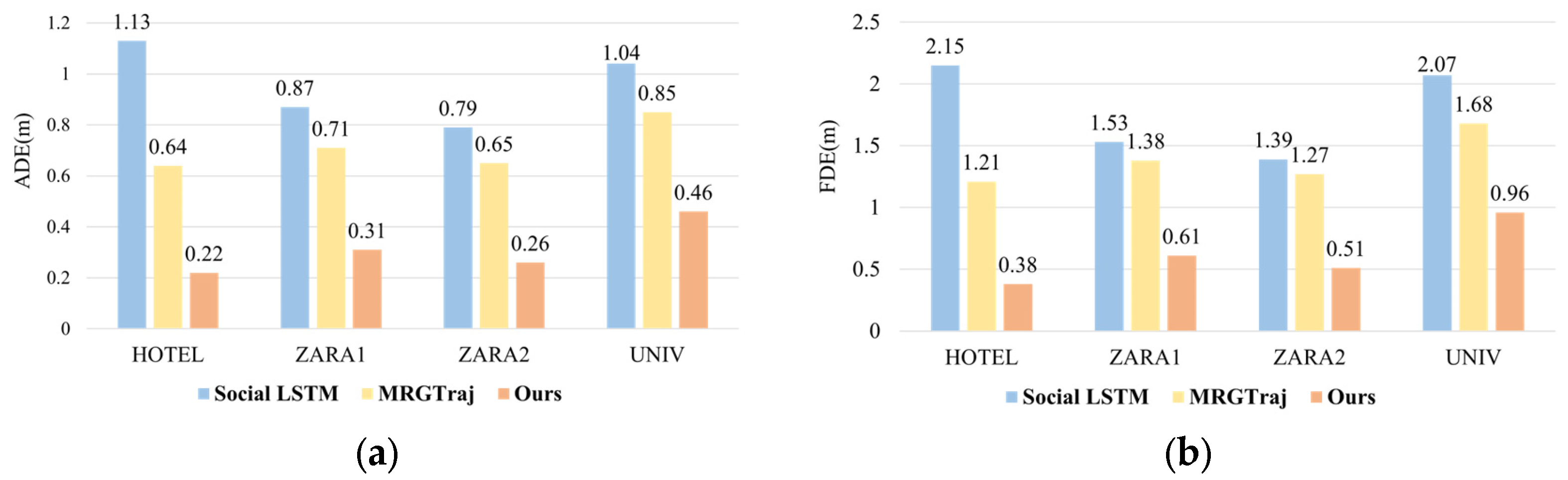

4.1. Trajectory Prediction and Error Evaluation

4.1.1. Simulation Experiments of Trajectory Prediction

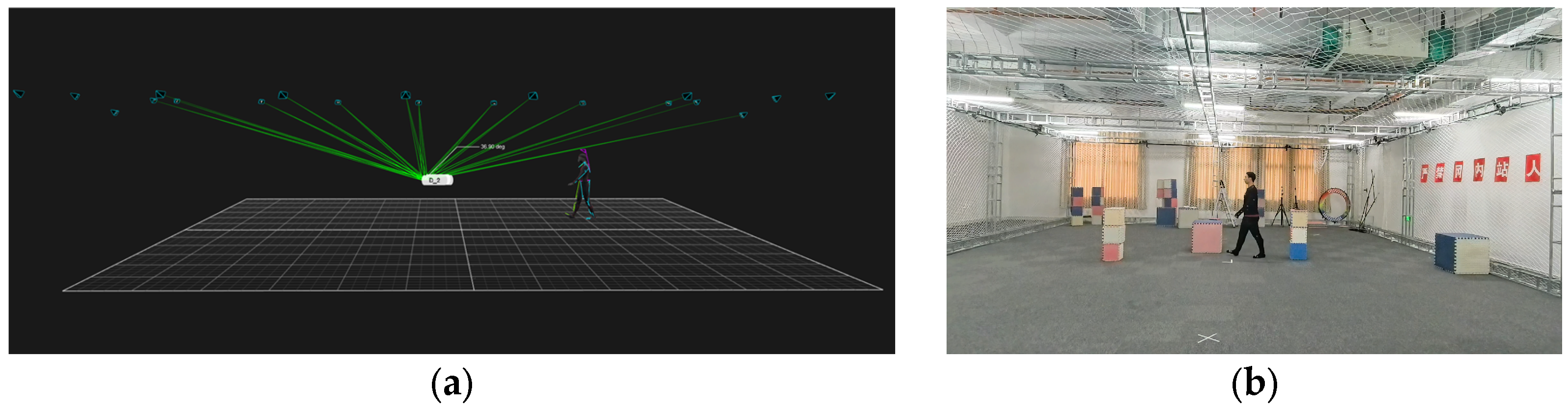

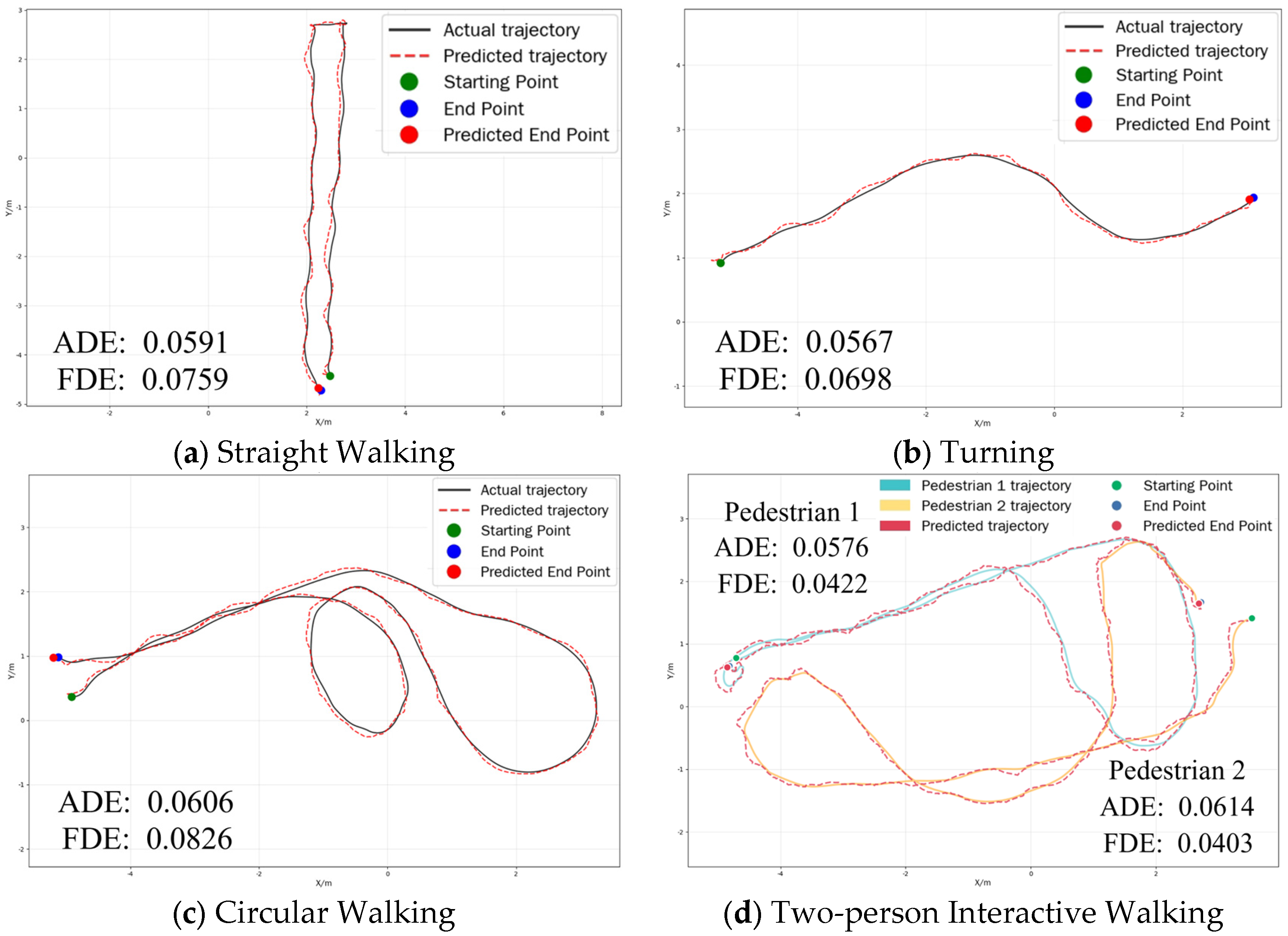

4.1.2. Physical Experiments of Trajectory Prediction

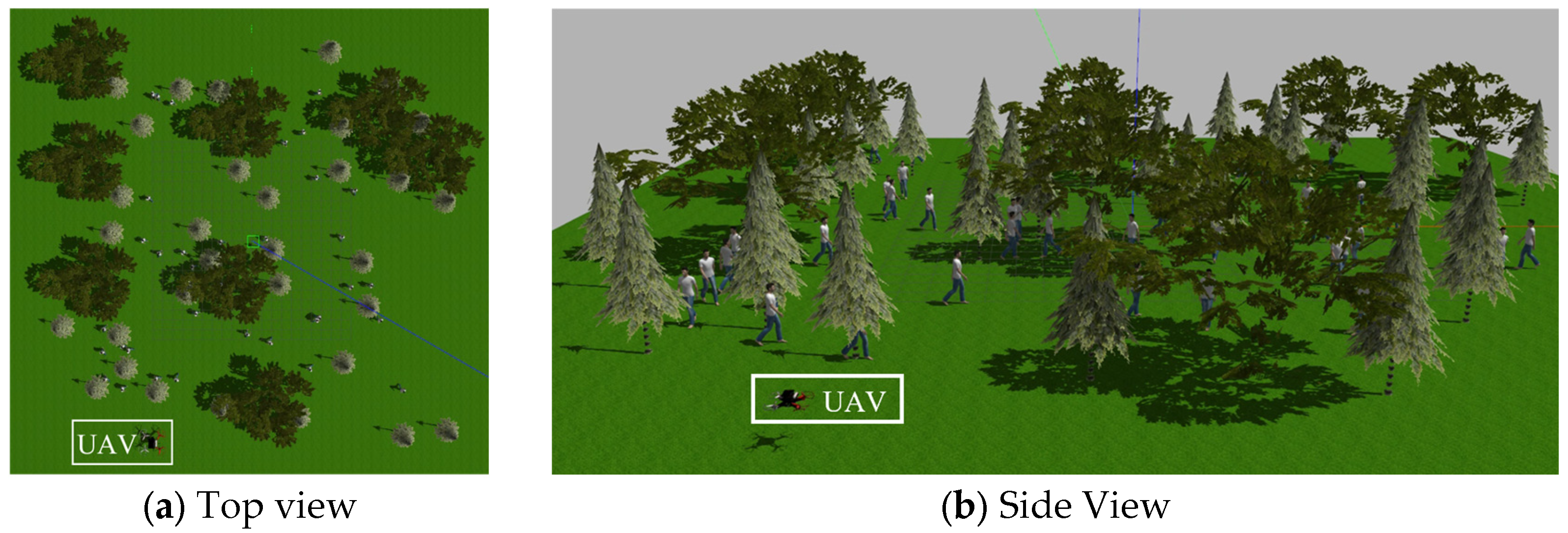

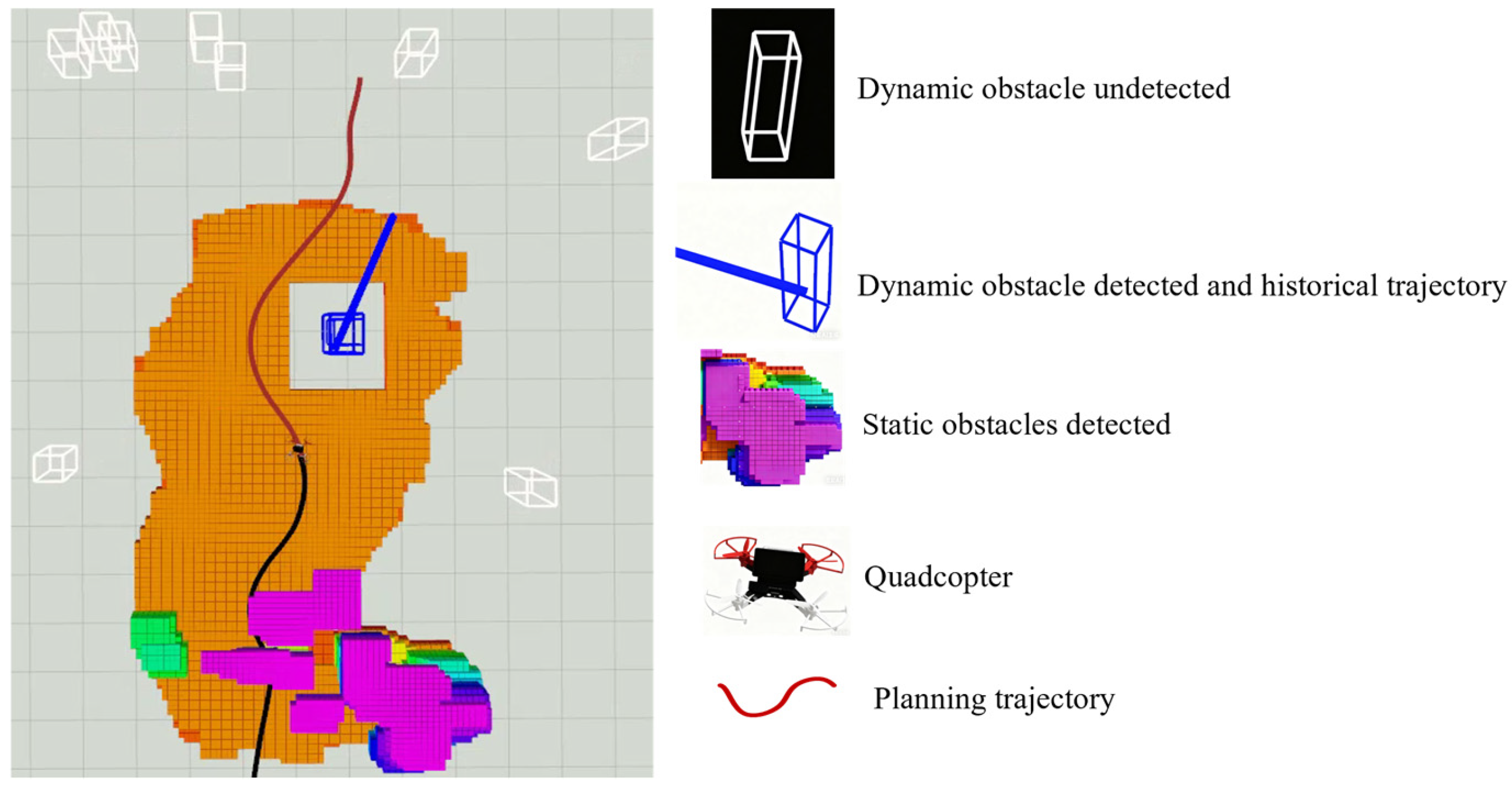

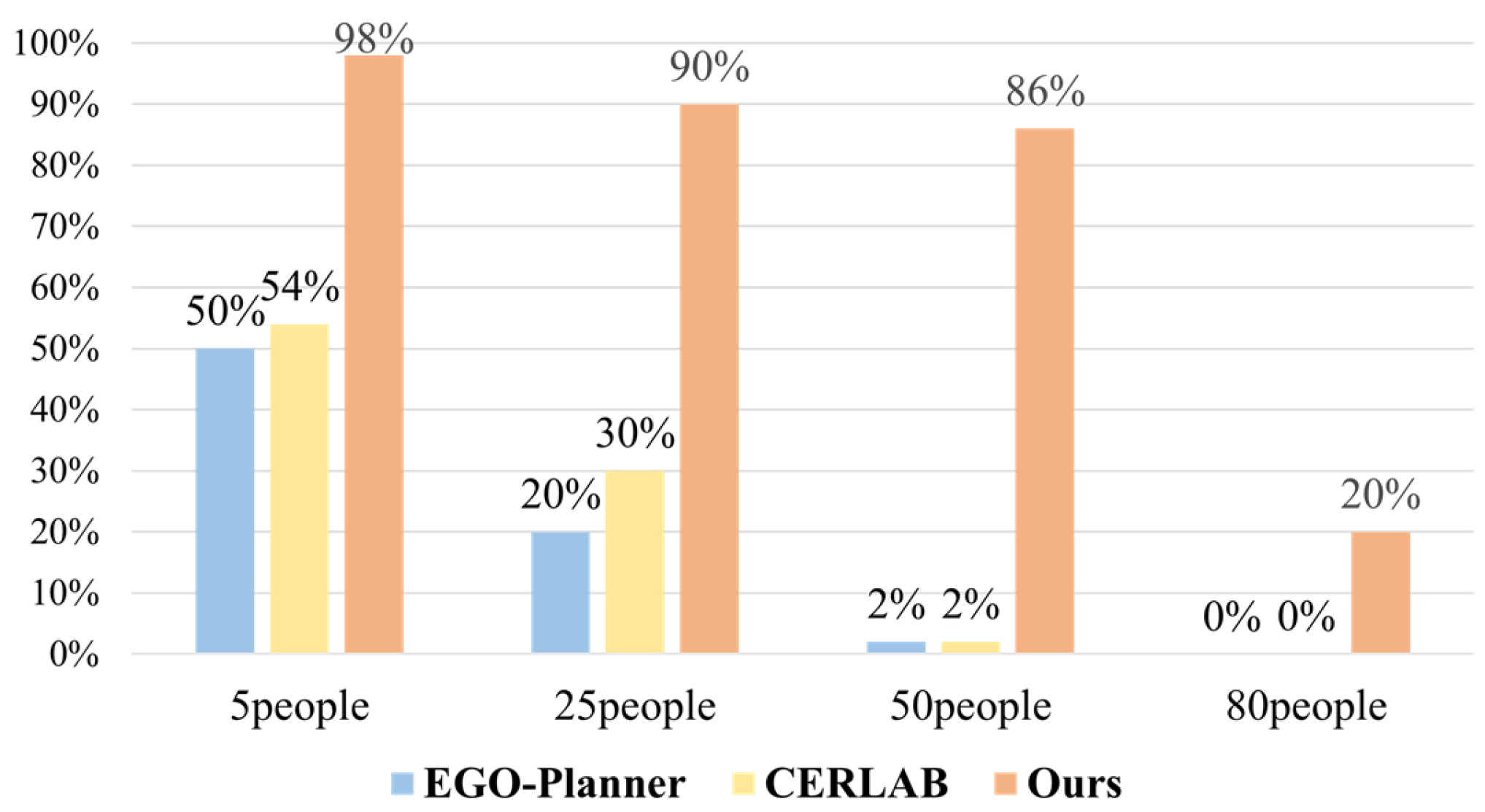

4.2. Trajectory Planning Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikolic, J.; Burri, M.; Rehder, J.; Leutenegger, S.; Huerzeler, C.; Siegwart, R. A UAV System for Inspection of Industrial Facilities. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alahi, A.; Goel, K.; Ramanathan, V.; Robicquet, A.; Fei-Fei, L.; Savarese, S. Social Lstm: Human Trajectory Prediction in Crowded Spaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 961–971. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, X.-T.; Ngo, T.D. Toward Socially Aware Robot Navigation in Dynamic and Crowded Environments: A Proactive Social Motion Model. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2017, 14, 1743–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, X.-T.; Ngo, T.-D. “To Approach Humans?”: A Unified Framework for Approaching Pose Prediction and Socially Aware Robot Navigation. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2017, 10, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, F.; Bellotto, N.; Cosar, S.; Weber, F.; Nathanael, D.; Althoff, M.; Wu, J.; Ruenz, J.; Dietrich, A.; Markkula, G. Pedestrian Models for Autonomous Driving Part II: High-Level Models of Human Behavior. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 5453–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammoun, S.; Nashashibi, F. Real Time Trajectory Prediction for Collision Risk Estimation between Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 27–29 August 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Ouyang, W.; Zhang, P.; Xue, J.; Zheng, N. Sr-Lstm: State Refinement for Lstm towards Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 12085–12094. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Ma, X.; Ren, J.; Zhao, H.; Yi, S. Spatio-Temporal Graph Transformer Networks for Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12357, pp. 507–523. ISBN 978-3-030-58609-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.; Qian, K.; Elhoseiny, M.; Claudel, C. Social-Stgcnn: A Social Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Neural Network for Human Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 19 June 2020; pp. 14424–14432. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, L. MRGTraj: A Novel Non-Autoregressive Approach for Human Trajectory Prediction. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValle, S.M. Rapidly-Exploring Random Trees: A New Tool for Path Planning; Technical Report 98-11; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, A.; Wurm, K.M.; Bennewitz, M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. OctoMap: An Efficient Probabilistic 3D Mapping Framework Based on Octrees. Auton. Robots 2013, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, J.; Sujit, P.B. PANDA: Priority-Based Collision Avoidance Framework for Heterogeneous UAVs Navigating in Dense Airspace. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Detroit, MI, USA, 19–23 May 2025; Richland: Columbia, SC, USA, 2025; pp. 2750–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Teo, R.S.H.; Tan, K.K. Collision Avoidance of Multi Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Review. Annu. Rev. Control 2019, 48, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, J.R.; Olsen, P.A. Approximating the Kullback Leibler Divergence between Gaussian Mixture Models. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing-ICASSP’07, Honolulu, HI, USA, 15–20 April 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 4, pp. IV–317. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Tian, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Qi, X.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H. Decoupled Kullback-Leibler Divergence Loss. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 74461–74486. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, I.; Matthey, L.; Pal, A.; Burgess, C.; Glorot, X.; Botvinick, M.; Mohamed, S.; Lerchner, A. Beta-Vae: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Ye, H.; Xu, C.; Gao, F. Ego-Planner: An Esdf-Free Gradient-Based Local Planner for Quadrotors. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 6, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Qin, C.; Luo, L.; Liu, H.H.-T.; Hu, S. Cpa-Planner: Motion Planner with Complete Perception Awareness for Sensing-Limited Quadrotors. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 8, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenko, V.; Von Stumberg, L.; Pangercic, A.; Cremers, D. Real-Time Trajectory Replanning for MAVs Using Uniform B-Splines and a 3D Circular Buffer. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Gao, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Shen, S. Robust and Efficient Quadrotor Trajectory Generation for Fast Autonomous Flight. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 3529–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, S.; Ess, A.; Schindler, K.; Van Gool, L. You’ll Never Walk Alone: Modeling Social Behavior for Multi-Target Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 27 September–4 October 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, A.; Chrysanthou, Y.; Lischinski, D. Crowds by Example. Comput. Graph. Forum 2007, 26, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhan, X.; Chen, B.; Xiu, Y.; Yang, C.; Shimada, K. A Real-Time Dynamic Obstacle Tracking and Mapping System for UAV Navigation and Collision Avoidance with an RGB-D Camera. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 10645–10651. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Motion Capture System | OptiTrack |

| Software | Motive |

| Number of Cameras | 20 |

| Camera Frame Rate | 150 fps |

| Export Format | Csv |

| Exported Data Frame Rate | 1000 fps |

| Dynamic capture accuracy | Sub-millimeter level |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Sensor perception range | 9 m |

| Maximum flight speed | 2 (m·s−1) |

| Maximum flight acceleration | 3 (m·s−2) |

| Safety distance threshold | 0.5 m |

| Map resolution | 0.1 m |

| Map size | 40 × 40 × 3 m |

| Number of pedestrian obstacles | 5/25/50 |

| Max pedestrian speed | 1 (m·s−1) |

| Planner | ||

|---|---|---|

| CERLAB | 1.6 ms | 1.9 ms |

| Ours | 1 ms | 1.2 ms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Yin, Q.; Zhou, S. Research on UAV Autonomous Trajectory Planning Based on Prediction Information in Crowded Unknown Dynamic Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237343

Tang J, Yang S, Chen S, Li Q, Yin Q, Zhou S. Research on UAV Autonomous Trajectory Planning Based on Prediction Information in Crowded Unknown Dynamic Environments. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237343

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Jianing, Songyan Yang, Shijie Chen, Qiao Li, Qian Yin, and Sida Zhou. 2025. "Research on UAV Autonomous Trajectory Planning Based on Prediction Information in Crowded Unknown Dynamic Environments" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237343

APA StyleTang, J., Yang, S., Chen, S., Li, Q., Yin, Q., & Zhou, S. (2025). Research on UAV Autonomous Trajectory Planning Based on Prediction Information in Crowded Unknown Dynamic Environments. Sensors, 25(23), 7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237343