Research on Wavefront Sensing Applications Based on Photonic Lanterns

Abstract

1. Introduction

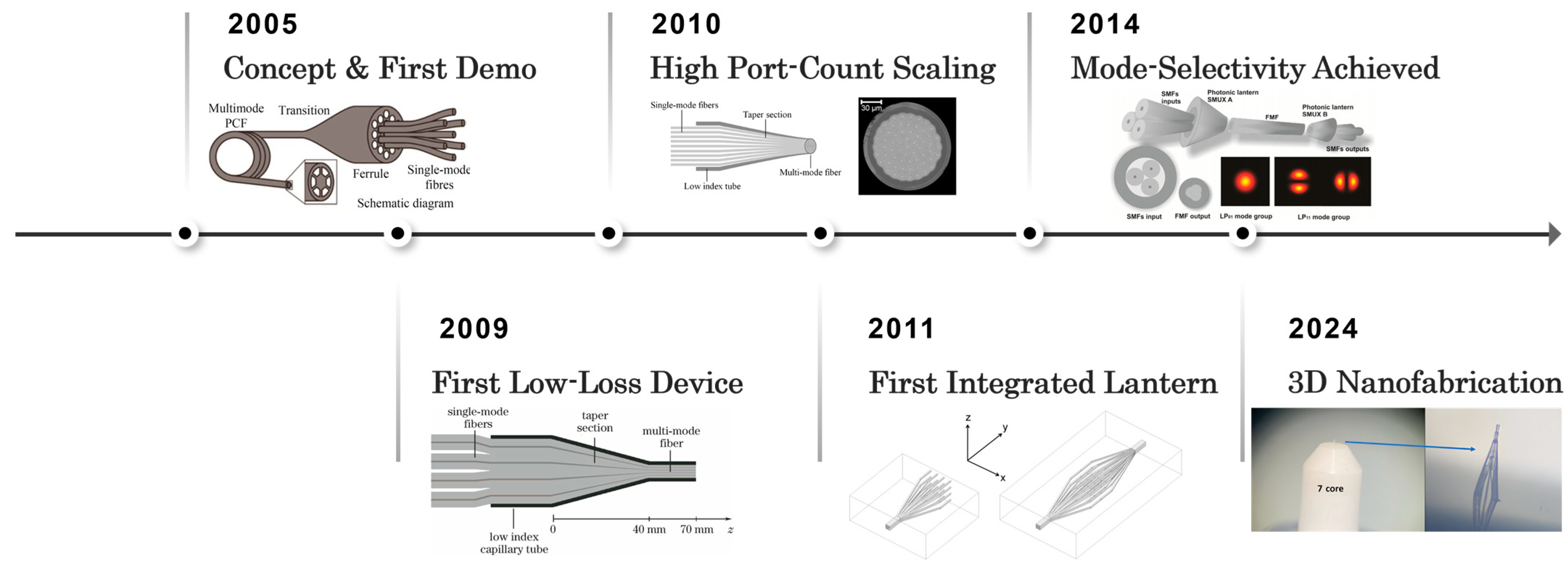

2. Fabrication of Photonic Lanterns

3. Current Status of Photonic Lantern Wavefront Sensor Research

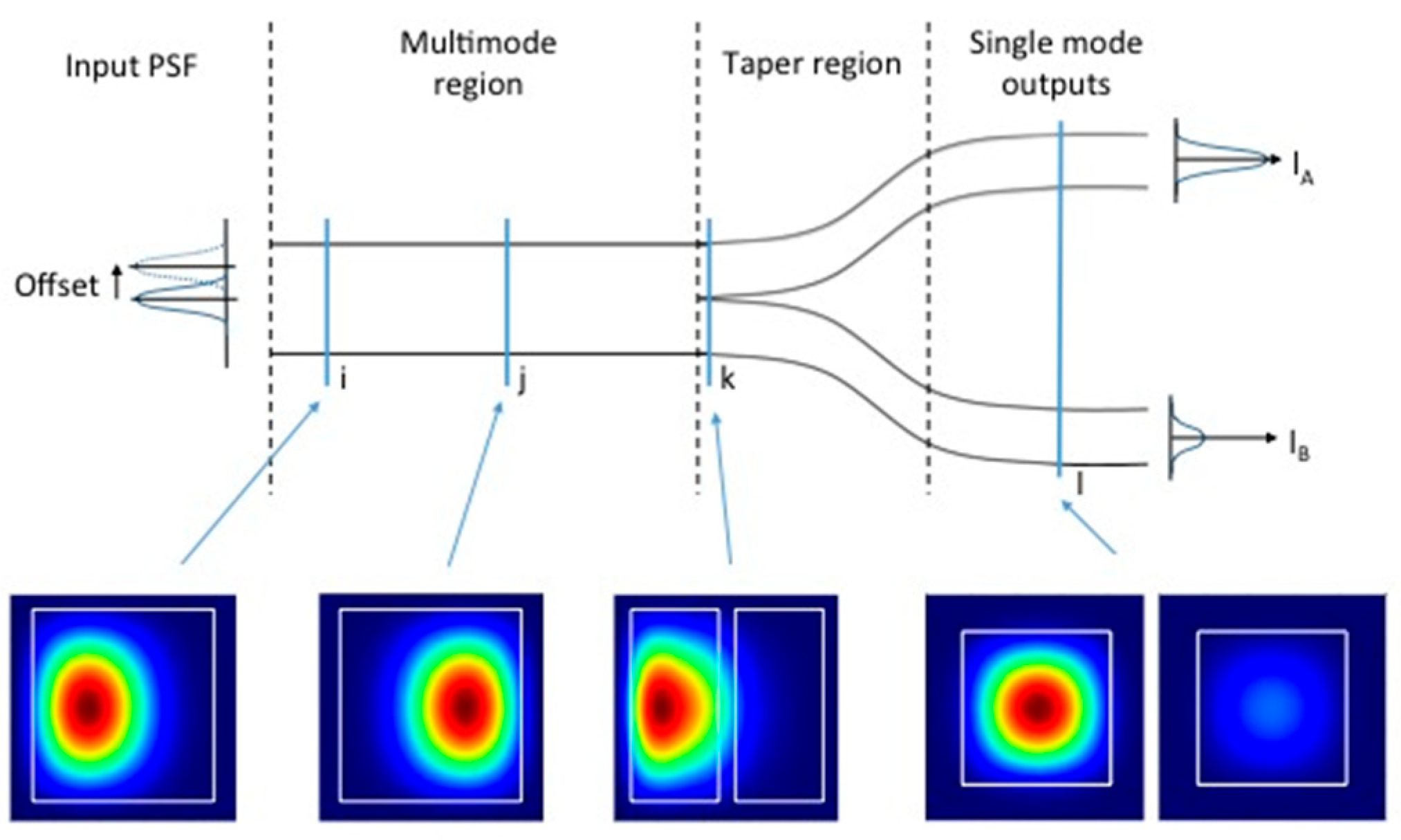

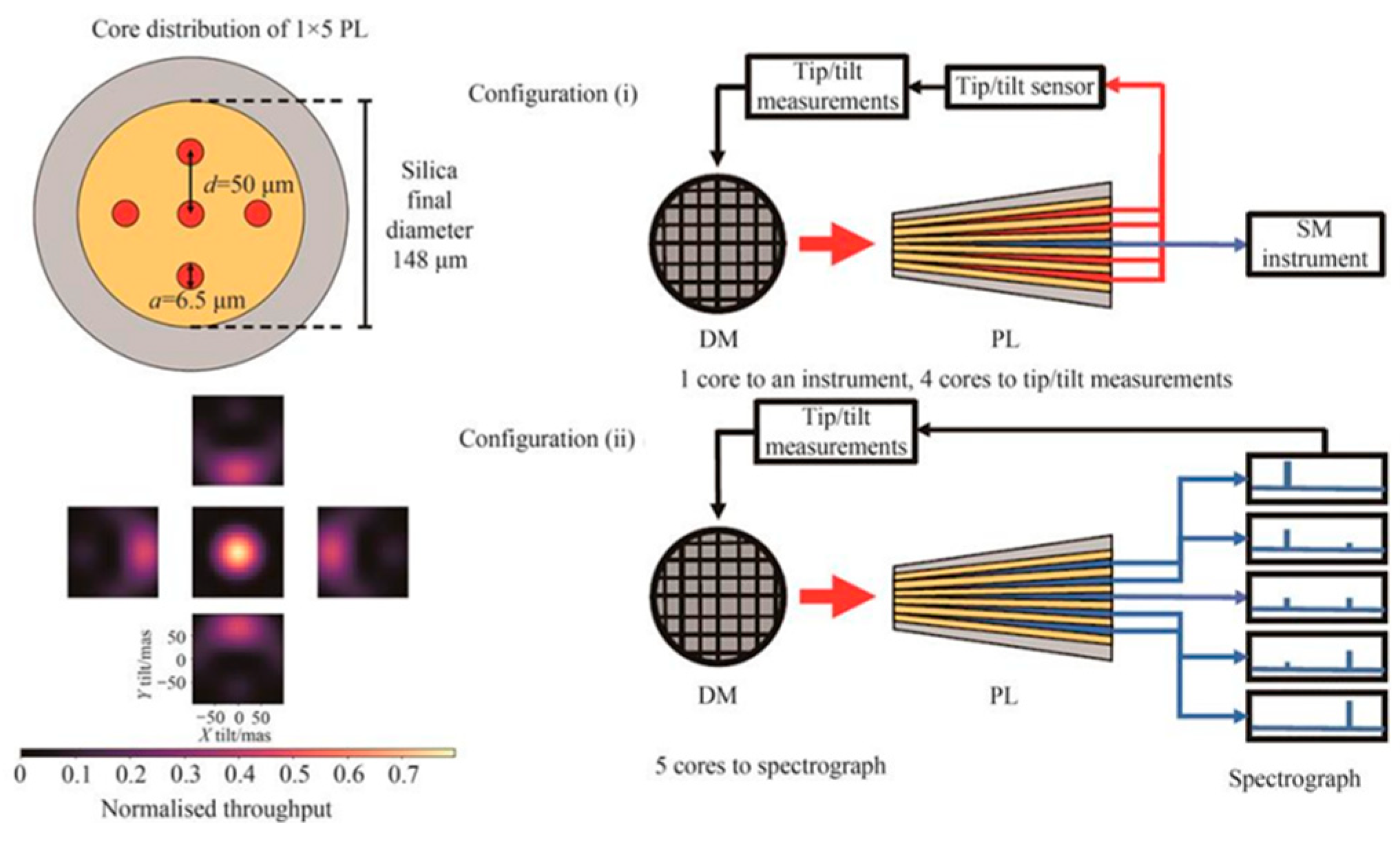

3.1. Initial Explorations

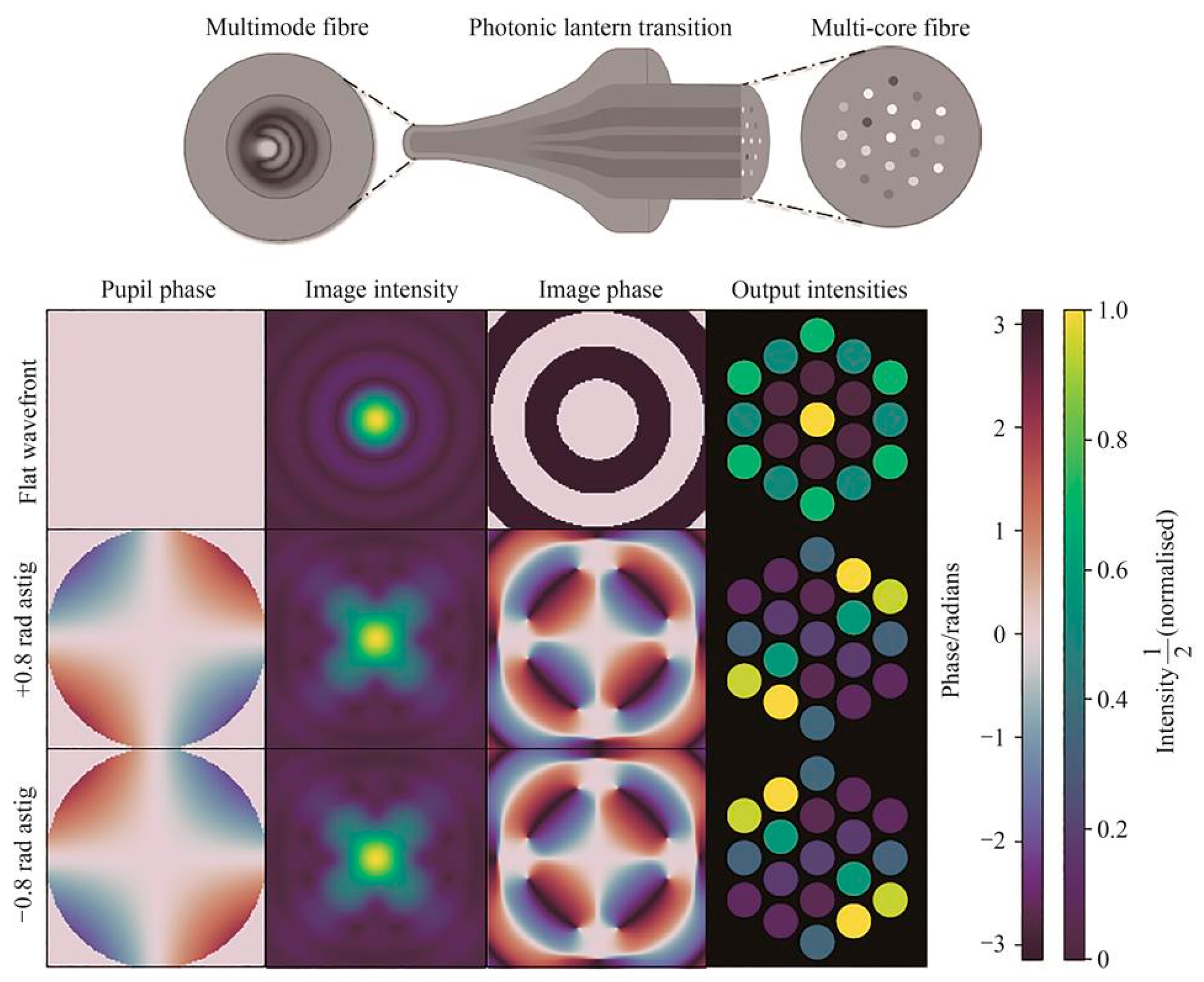

3.2. Theoretical Modeling

3.3. Neural Network Technology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babcock, H.W. The Possibility of Compensating Astronomical Seeing. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 1953, 65, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Williams, D.R.; Miller, D.T. Supernormal Vision and High-Resolution Retinal Imaging through Adaptive Optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1997, 14, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.V. Atmospheric-Turbulence Compensation Experiments Using Cooperative Beacons. Linc. Lab. J. 1992, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, B.C.; Shack, R. History and Principles of Shack-Hartmann Wavefront Sensing. J. Refract. Surg. 2001, 17, S573–S577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyant, J.C. Use of an Ac Heterodyne Lateral Shear Interferometer with Real–Time Wavefront Correction Systems. Appl. Opt. 1975, 14, 2622–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddier, F. Curvature Sensing and Compensation: A New Concept in Adaptive Optics. Appl. Opt. 1988, 27, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, J.-F.; Fusco, T.; Rousset, G.; Petit, C. Calibration and Precompensation of Noncommon Path Aberrations for Extreme Adaptive Optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2007, 24, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milli, J.; Mouillet, D.; Beuzit, J.-L.; Sauvage, J.-F.; Fusco, T.; Bourget, P.; Kasper, M.; Tristam, K.; Reyes, C.; Girard, J.H.; et al. Low Wind Effect on VLT/SPHERE: Impact, Mitigation Strategy, and Results. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Optics Systems VI; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Close, L.M., Eds.; SPIE: Austin, TX, USA, 2018; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, K.M.; Turcotte, R.; Miller, D.T.; Kurokawa, K.; Males, J.R.; Ji, N.; Booth, M.J. Adaptive Optics for High-Resolution Imaging. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-Deana, R.I.; Sivry-Houle, M.P.; de Virally, S.; Boudoux, C.; Godbout, N. Mode-Selective Photonic Lanterns with Double-Clad Fibers. J. Lightwave Technol. 2025, 43, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, T.A.; Gris-Sánchez, I.; Yerolatsitis, S.; Leon-Saval, S.G.; Thomson, R.R. The Photonic Lantern. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2015, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gris-Sánchez, I.; Haynes, D.M.; Ehrlich, K.; Haynes, R.; Birks, T.A. Multicore Fibre Photonic Lanterns for Precision Radial Velocity Science. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2018, 475, 3065–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Saval, S.G.; Fontaine, N.K.; Salazar-Gil, J.R.; Ercan, B.; Ryf, R.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. Mode-Selective Photonic Lanterns for Space-Division Multiplexing. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikenberry, S.S.; Bentz, M.; Gonzalez, A.; Harrington, J.; Jeram, S.; Law, N.; Maccarone, T.; Quimby, R.; Townsend, A. Astro2020 Project White Paper: PolyOculus—Low-Cost Spectroscopy for the Community. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.08273. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, B.R.M.; Wei, J.; Betters, C.H.; Wong, A.; Leon-Saval, S.G. An All-Photonic Focal-Plane Wavefront Sensor. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milli, J.; Kasper, M.; Bourget, P.; Pannetier, C.; Mouillet, D.; Sauvage, J.F.; Reyes, C.; Fusco, T.; Cantalloube, F.; Tristam, K.; et al. Low Wind Effect on VLT/SPHERE: Adaptive Optics Systems VI 2018. In Adaptive Optics Systems VI; SPIE: Austin, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland-Hawthorn, J.; Kern, P. Astrophotonics: A New Era for Astronomical Instruments. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 1880–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, D.; Norris, B.R.M.; Tuthill, P.; Scalzo, R.; Wei, J.; Betters, C.H.; Leon-Saval, S.G. Learning the Lantern: Neural Network Applications to Broadband Photonic Lantern Modelling. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2021, 7, 028007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, B.R.M.; Wei, J.; Betters, C.; Leon-Saval, S.; Xin, Y.; Lin, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Sallum, S.; Lozi, J.; Vievard, S.; et al. Demonstration of a Photonic-Lantern Focal-Plane Wavefront Sensor Using Fibre Mode Conversion and Deep Learning. In Adaptive Optics Systems VIII; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Vernet, E., Eds.; SPIE: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2022; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Saval, S.G.; Birks, T.A.; Bland-Hawthorn, J.; Englund, M. Multimode Fiber Devices with Single-Mode Performance. Opt. Lett. 2005, 30, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordegraaf, D.; Skovgaard, P.M.; Nielsen, M.D.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. Efficient Multi-Mode to Single-Mode Coupling in a Photonic Lantern. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordegraaf, D.; Skovgaard, P.M.W.; Maack, M.D.; Bland-Hawthorn, J.; Haynes, R.; Laegsgaard, J. Multi-Mode to Single-Mode Conversion in a 61 Port Photonic Lantern. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 4673–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.R.; Birks, T.A.; Leon-Saval, S.G.; Kar, A.K.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. Ultrafast Laser Inscription of an Integrated Photonic Lantern. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 5698–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, Y.; Garcia, Y.; Kukin, A.; Dallachiesa, L.; Guerrier, S.; Fontaine, N.K.; Marom, D.M. Free-Standing Microscale Photonic Lantern Spatial Mode (De-)Multiplexer Fabricated Using 3D Nanoprinting. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, P.; Fokine, M. Thermometric Study of CO2-Laser Heated Optical Fibers in Excess of 1700 °C Using Fiber Bragg Gratings. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2013, 30, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J.D.; Henry, W.M.; Stewart, W.J.; Black, R.J.; Lacroix, S.; Gonthier, F. Tapered Single-Mode Fibres and Devices. Part 1: Adiabaticity Criteria. IEE Proc. J. (Optoelectron.) 1991, 138, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.M.; Miura, K.; Sugimoto, N.; Hirao, K. Writing Waveguides in Glass with a Femtosecond Laser. Opt. Lett. 1996, 21, 1729–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasu, Y.; Kohtoku, M.; Hibino, Y. Low-Loss Waveguides Written with a Femtosecond Laser for Flexible Interconnection in a Planar Light-Wave Circuit. Opt. Lett. 2005, 30, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola, A.; Gross, S.; Jovanovic, N.; Charles, N.; Tuthill, P.G.; Olaizola, S.M.; Fuerbach, A.; Withford, M.J. Low Bend Loss Waveguides Enable Compact, Efficient 3D Photonic Chips. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 2978–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, M.; Harris, R.J.; Thomson, R.R.; MacLachlan, D.G.; Allington-Smith, J.; Myers, R.; Morris, T. Wavefront Sensing Using a Photonic Lantern; Marchetti, E., Close, L.M., Véran, J.-P., Eds.; SPIE: Edinburgh, UK, 2016; p. 990969. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, M.; Morris, T.J.; Harris, R.J.; Anagnos, T. Demonstration of a Photonic Lantern Low Order Wavefront Sensor Using an Adaptive Optics Testbed. In Adaptive Optics Systems VI; Schmidt, D., Schreiber, L., Close, L.M., Eds.; SPIE: Austin, TX, USA, 2018; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Delgado, D.; Alvarado-Zacarias, J.C.; Cooper, M.A.; Wittek, S.; Dobias, C.; Martinez-Mercado, J.; Antonio-Lopez, J.E.; Fontaine, N.K.; Amezcua-Correa, R. Photonic Lantern Tip/Tilt Detector for Adaptive Optics Systems. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Xin, Y.; Guyon, O.; Leon-Saval, S.; Norris, B.; Jovanovic, N. Focal-Plane Wavefront Sensing with Photonic Lanterns I: Theoretical Framework. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2022, 39, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Fitzgerald, M.P.; Xin, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Guyon, O.; Leon-Saval, S.; Norris, B.; Jovanovic, N. Focal-Plane Wavefront Sensing with Photonic Lanterns II: Numerical Characterization and Optimization. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2023, 40, 3196–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.W.; Fitzgerald, M.P.; Xin, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Guyon, O.; Norris, B.; Betters, C.; Leon-Saval, S.; Ahn, K.; Deo, V.; et al. Real-Time Experimental Demonstrations of a Photonic Lantern Wave-Front Sensor. ApJL 2023, 959, L34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Fitzgerald, M.P. Nonlinear Techniques for Few-Mode Wavefront Sensors. Appl. Opt. 2024, 63, 8748–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Fitzgerald, M.P.; Xin, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Guyon, O.; Norris, B.; Betters, C.; Leon-Saval, S.; Ahn, K.; Deo, V.; et al. Experimental and On-Sky Demonstration of Spectrally Dispersed Wavefront Sensing Using a Photonic Lantern. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, A.R.; Chambouleyron, V.; Diaz, J.; DeMartino, M.; Jensen-Clem, R.; Gerard, B.L.; Messerly, M.J.; Pax, P.; Dillon, D.; Bundy, K.; et al. Experimental Validation of Photonic Lantern Imaging and Wavefront Sensing Performance. In Techniques and Instrumentation for Detection of Exoplanets XII; SPIE: Austin, TX, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, M.A.; Batarseh, A.B.; Crowe, T.; Conwell, R.; Dobias, C.; Cruz-Delgado, D.; Bandres, M.A.; Amezcua-Correa, R.; Eikenberry, S.S. Broadband Photonic Lantern Transfer Matrix Characterization for Wavefront Sensing. In Photonic Instrumentation Engineering XII; Soskind, Y., Busse, L.E., Eds.; SPIE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Batarseh, A.B.; Romer, M.A.; Bandres, M.A.; Amezcua-Correa, R.; Cruz-Delgado, D.; Eikenberry, S.S. Broadband Phase Retrieval for Photonic Lantern Wavefront Sensors. In Photonic Instrumentation Engineering XII; Soskind, Y., Busse, L.E., Eds.; SPIE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, N.K.; Ryf, R.; Bland-Hawthorn, J.; Leon-Saval, S.G. Geometric Requirements for Photonic Lanterns in Space Division Multiplexing. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 27123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Norris, B.; Betters, C.; Leon-Saval, S. Demonstration of a Photonic Lantern Focal-Plane Wavefront Sensor: Measurement of Atmospheric Wavefront Error Modes and Low Wind Effect in the Nonlinear Regime. J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 2024, 10, 049001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.R.; Diaz, J.; Gerard, B.L.; Jensen-Clem, R.; Dillon, D.; DeMartino, M.; Bundy, K.; Cetre, S.; Chambouleyron, V. Photonic Lantern Wavefront Reconstruction in a Multi-Wavefront Sensor Single-Conjugate Adaptive Optics System. In Adaptive Optics Systems IX; SPIE: Austin, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, X. Wavefront Sensing Using a 1*19 Photonic Lantern. In AOPC 2024: Laser Technology and Applications; Zhou, P., Ed.; SPIE: Beijing, China, 2024; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xie, L.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhu, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; et al. Research on Wavefront Sensing Applications Based on Photonic Lanterns. Sensors 2025, 25, 7300. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237300

Zhao Z, Zheng H, Xie L, Zhang J, Feng Z, Liu K, Zhu B, Wang D, Wang J, Liu W, et al. Research on Wavefront Sensing Applications Based on Photonic Lanterns. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7300. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237300

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhengkang, Hangyu Zheng, Lianghua Xie, Jie Zhang, Zhuoyun Feng, Kaige Liu, Bin Zhu, Deen Wang, Ju Wang, Wei Liu, and et al. 2025. "Research on Wavefront Sensing Applications Based on Photonic Lanterns" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7300. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237300

APA StyleZhao, Z., Zheng, H., Xie, L., Zhang, J., Feng, Z., Liu, K., Zhu, B., Wang, D., Wang, J., Liu, W., & Yuan, Q. (2025). Research on Wavefront Sensing Applications Based on Photonic Lanterns. Sensors, 25(23), 7300. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237300