1. Introduction

Tire hydroplaning represents a complex phenomenon influenced by several parameters related to the tire state, such as tread depth, inflation pressure, vertical load, longitudinal speed and the road state, including water film depth and road macro-texture [

1]. The risk of tire hydroplaning may be defined as the proximity of a tire to losing contact with the road surface and transitioning to complete rolling on the water layer [

2]. At present, no comprehensive model exists that captures all of the relevant parameters influencing hydroplaning risk. Furthermore, even if such a model were to be developed, a significant challenge would remain in obtaining accurate, real-time measurements of these parameters to enable reliable risk estimation. This study addresses the challenge by developing a real-time hydroplaning risk assessment methodology, leveraging data acquired based on an in-house-developed intelligent tire system.

An extensive literature review on tire hydroplaning, with a focus on real-time estimation methodologies and numerical modeling for both partial and total hydroplaning phenomena, was conducted by our research group at Virginia Tech [

3]. One major research direction in hydroplaning risk assessment is the development of intelligent tire systems, which integrate embedded sensors to monitor tire–road interactions in real time and provide data for improving vehicle safety and control. Comprehensive surveys were presented by Taheri [

4] and Yang [

5]. Tuononen [

6] proposed the first intelligent tire concept for hydroplaning risk estimation, utilizing an optical sensor to identify shifts in peak vertical carcass deflection caused by the water wedge effect. On the next iteration of the intelligent tire design, Tuononen [

7] replaced the optical sensor with three accelerometers mounted on the tire inner liner, aiming at detecting the threshold between partial and total hydroplaning based on longitudinal and lateral acceleration signals. Using a similar instrumentation methodology, Cheli [

8] and D’Alessandro [

9] were able to calculate a hydroplaning index from the radial acceleration signal measured by an MEMS accelerometer mounted on the tire inner liner. The hydrodynamic lift force and the water wedge effect modify the radial acceleration signature, producing delayed entry, signal oscillations, and a more pronounced minimum acceleration at patch exit. Hartman [

10] proposes a real-time hydroplaning risk assessment system that combines external and internal sensing technologies. Road conditions are classified using a surround-view camera with computer vision and machine learning, while an intelligent tire equipped with an accelerometer detects the hydroplaning signature from radial acceleration. Data fusion enables an accurate estimation of the critical hydroplaning speed for the instrumented tire. Another research direction involves assessing hydroplaning risk using sensors already available in modern vehicles, with notable contributions from Fichtinger [

11] and Blandina [

1].

Model-based approaches have also been pursued. Montini [

12] extended the MF-Tyre (Magic Formula) model by introducing scaling factors to represent water effects on cornering stiffness, relaxation length, friction, and motion resistance, calibrated against experimental data and linked to the volumetric drainage capacity of the tire. An ADAS (Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems) control strategy was demonstrated on a 14-DOF vehicle model, reducing speed below the critical threshold via rear-axle braking and stabilizing yaw through the cleaning effect.

In line with this research direction, this work underscores the significance of water evacuation capacity on critical hydroplaning speed, emphasizing recent analyses of groove flow mechanics in the contact patch region. Cabut [

13] related the hydroplaning risk to the ability of the tire tread to evacuate water. Therefore, the research effort focused on better understanding the water flow inside the tread groove and identifying the key parameters that influence this physical phenomenon using an optical method based on Particle Image Velocimetry. The flow inside the longitudinal grooves reveals elongated white filaments, indicating air bubbles or cavities. Flow distortions can be observed, particularly in larger longitudinal grooves, displaying periodic behavior aligned with the spacing between adjacent transverse grooves. Within the contact patch area, the deformable solid walls of the groove (side walls and upper wall) are essentially stationary and the flow inside the groove approximates a channel flow with no-slip boundaries. The authors also emphasized that a significant mechanism affecting water flow in the tread grooves is vortex formation. This effect occurs near the entry of the contact patch area, where the load exerted by the tire on the layer of water causes a squeezing action, which can lead to the creation of two vortices with transverse water injection into the lower part of the groove.

Todoroff [

14] and Veith [

15] demonstrated in their research the influence of hydroplaning on the braking performance of both new and worn tires. Todoroff [

14] introduced the concept of “hydro efficiency” to assess the tire sensitivity to hydroplaning, while Veith [

15] developed the “water discharge capacity” parameter to evaluate the tire water evacuation capability. Both studies revealed that worn tires exhibit a significant reduction in braking capacity at higher longitudinal speeds, attributed to the onset of partial hydroplaning. These findings underscore the importance of developing real-time methodologies to quantify hydroplaning risk, not only to understand the proximity of the tire to complete loss of road contact, but also to enable a more accurate assessment of a vehicle’s braking performance. Lower [

16] developed a test procedure for measuring the fluid pressure between the tire and the wet pavement using an inner drum test bench equipped with a piezoelectric pressure sensor. The results revealed a sharp increase in pressure as the sensor entered the tire contact patch, followed by a decline toward zero, eventually reaching a negative pressure region at the rear of the footprint where the tread lifts off the pavement. (A similar trend was observed in the present experimental setup, where the force sensor was embedded in the tire groove rather than on the road surface.) In his research, Wies [

17] examined the influence of tread pattern voids on hydroplaning by applying existing hydrodynamic pressure models. A key finding relevant to the present study is the mechanism by which water floods the tread grooves. The interaction between the tread block and the wet pavement was analyzed using the Bathelt [

18] rib sinkage model, which solves the Navier–Stokes equations analytically for an infinitely long pattern rib penetrating the water layer to reach the road surface. As the tread blocks contact the wet pavement, the water film is partly squeezed into the grooves and partly expelled to the edges of the contact patch. Once the grooves are flooded, the tire effectively behaves like a smooth tire. Even more importantly, the research demonstrates that groove flooding can occur even under hydroplaning conditions where the water film thickness is significantly less than the tread depth. Sinnamon [

19] detailed how the squeeze-film phenomenon and water accumulation in the tread grooves are influenced by the contact patch length and the contact patch pressure distribution. For example, in the case of shallow hydroplaning conditions, the portion of the contact patch that becomes flooded with water is inversely proportional to the contact patch length and the contact patch pressure. If the inflation pressure is increased, the contact pressure increases and the contact patch length decreases. In this scenario, the net effect of the inflation pressure on the flooding of the contact patch remains small. In the case of deep hydroplaning conditions (consistent with the majority of literature on hydroplaning, where the water depth has high values above 7–8 mm), the additional hydrodynamic pressure tends to slow down the squeeze-film phenomenon, and the inflation pressure has a much greater effect on the overall hydroplaning phenomenon [

19]. Consistent with the mechanism described above, an increase in tire vertical load will generate an increase in contact patch length and contact patch pressure. This will improve the tire’s overall hydroplaning behavior. Tire temperature is not specifically included in hydroplaning studies, although the expected effects on hydroplaning behavior are anticipated to follow the same mechanisms related to contact patch length and contact patch pressure distribution.

Current research on hydroplaning primarily focuses on deep water conditions where a water wedge forms in front of the tire contact patch. Most of the sensing and modeling approaches rely on this mechanism to estimate the risk of hydroplaning. As indicated in our previous research [

20], the developed intelligent tire system and the proposed methodology aim to estimate the hydroplaning risk also in shallow water conditions where the water wedge effect is not always present. In this research, the hydroplaning risk is estimated based on direct measurement of the water lift force inside the tread groove and provides real-time information about the onset of partial hydroplaning. This approach does not depend on the formation of the water wedge and can therefore offer reliable hydroplaning risk estimation across both shallow and deep-water conditions.

4. Model Validation

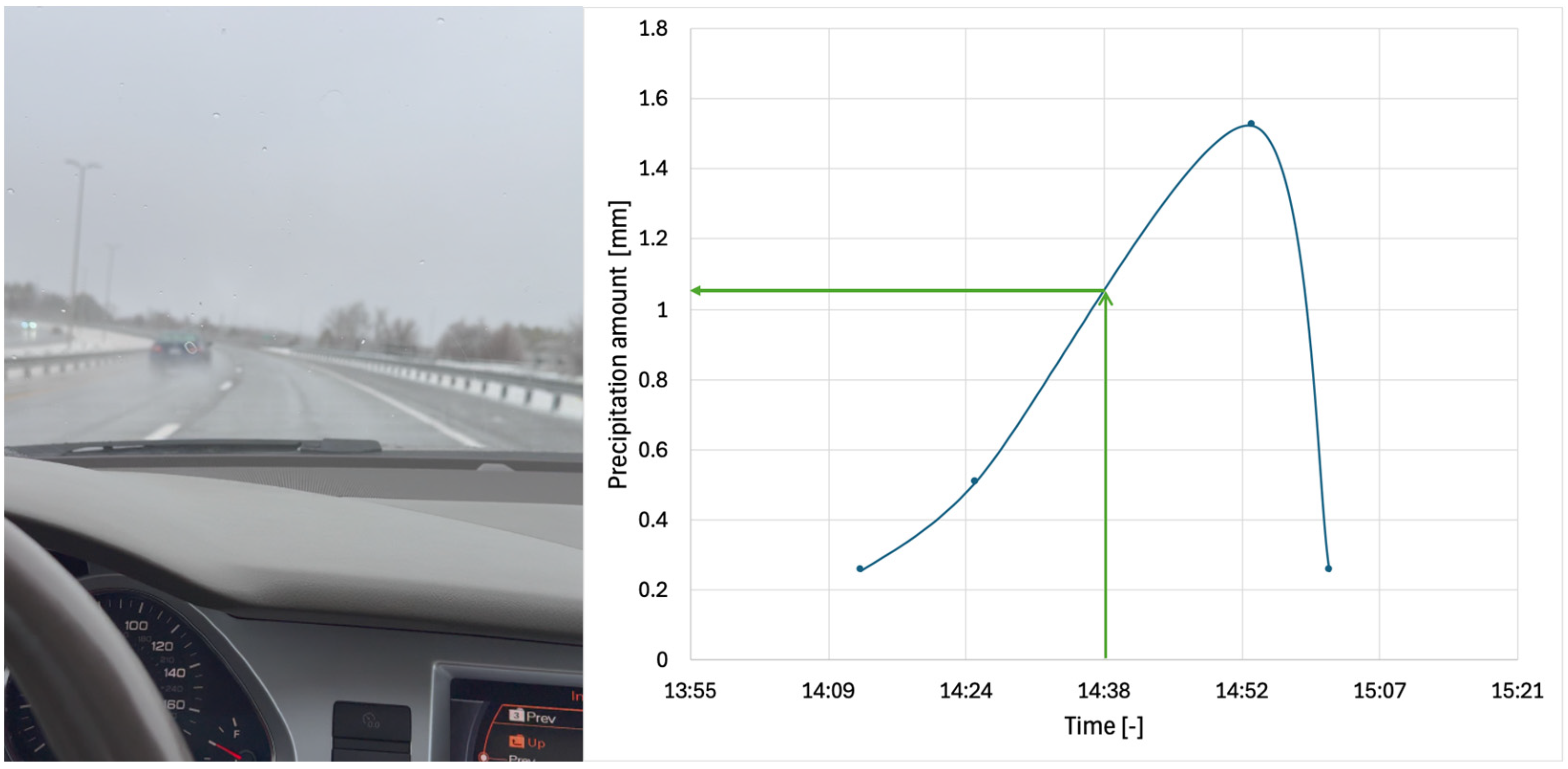

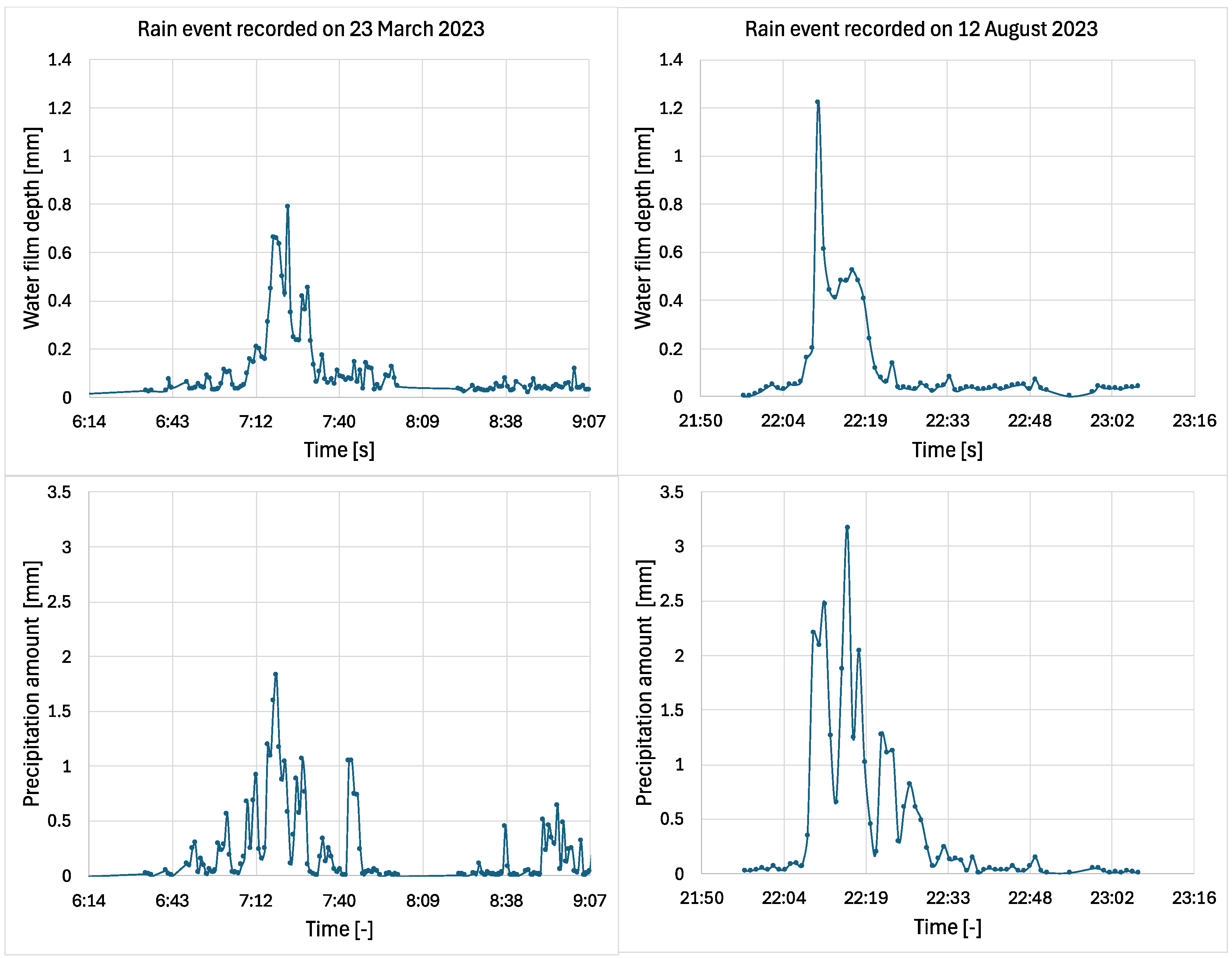

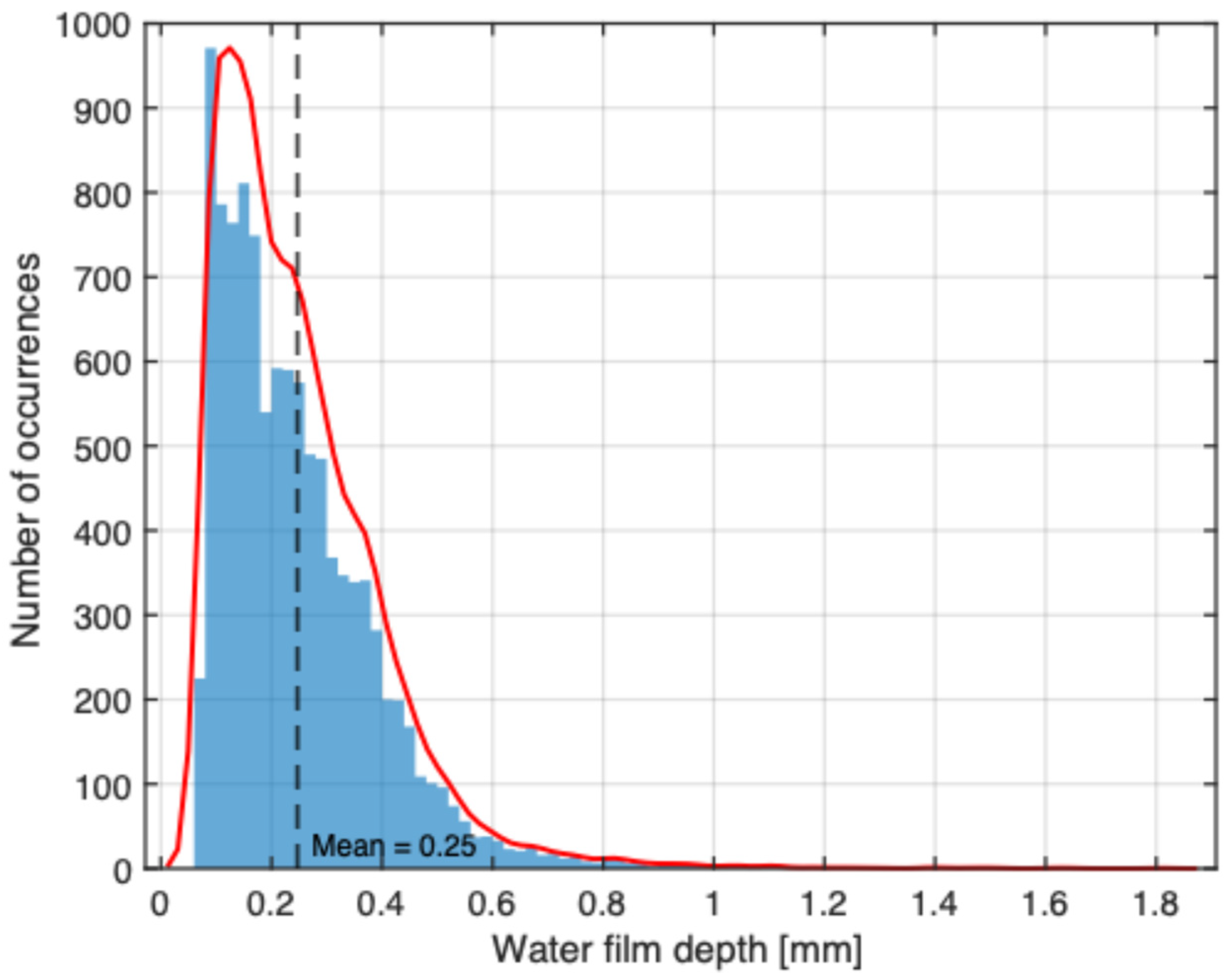

This section presents the method used to validate the hydroplaning risk model developed in the previous chapters. The validation approach involves comparing the hydroplaning risk data obtained with the intelligent tire system during controlled tests at a water film depth of 1.05 mm with literature data obtained from optical observations of the tire contact patch filmed under similar conditions. The validation tests were performed at Michelin Laurens Proving Grounds in South Carolina. One of the main sources of uncertainty in the presented hydroplaning data is the estimation of the water film depth. While most standardized hydroplaning tests are performed at a water depth of approximately 8 mm, this value does not reflect typical conditions encountered in real-world driving. To address this gap, the tests in this study were specifically performed at a controlled water film depth of 1.05 mm, in order to better represent realistic wet-road scenarios.

Figure 13 illustrates the testing setup and environmental conditions used during the validation experiments.

Per Michelin’s standard test protocols, the water depth was maintained approximately constant along the longitudinal direction of the test track (150 m in length), while in the lateral direction it varied for different fixed values below the maximum of 1.05 mm, according to the marked reference lines shown in

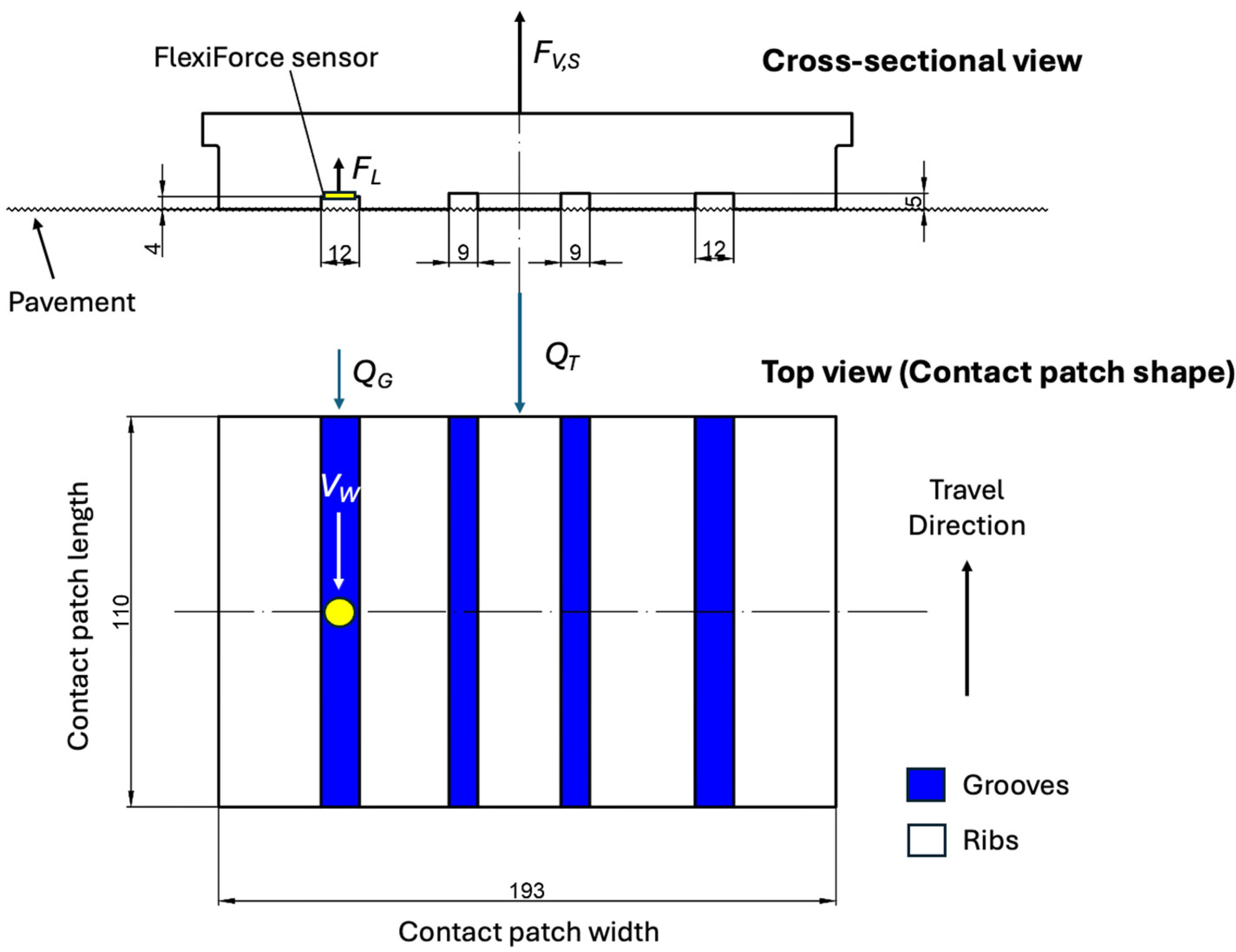

Figure 13. For these experiments, the instrumented tire was mounted on the left front wheel position to ensure that the test tire encountered the desired water depth. The tests were conducted on 21 August 2025, more than six months after the initial real-world measurements on US 460. During this interval, the tires accumulated an additional 4000 miles (6437 km), and the wear-related parameters summarized in

Table 1 were updated accordingly. The groove depth

GD of the instrumented channel decreased to 3.7 mm, while the average tread depth

TD reached 4.4 mm. The total cross-sectional area of the grooves was measured at 180.3 mm

2, with the groove instrumented with the FlexiForce sensor having an area of 44.4 mm

2. Based on these updated values, the groove flow rate

QG is estimated to represent 24.6% of the total intake flow rate

QT, thereby modifying the first term of Equation (5).

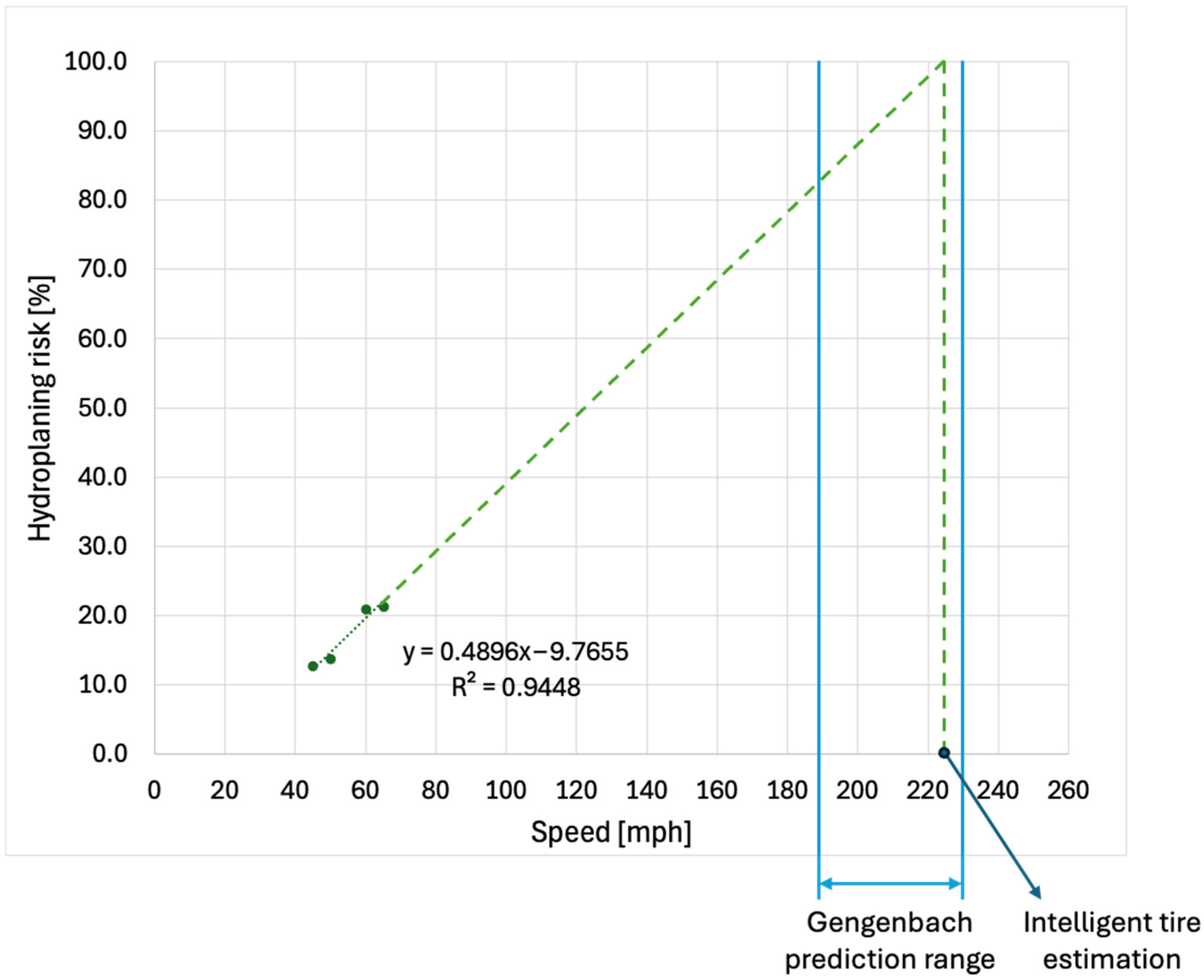

Figure 14 shows the measured lift force signal for two longitudinal speeds at 40 mph (64.4 km/h) and 50 mph (80.5 km/h), and a controlled water depth of 1.05 mm.

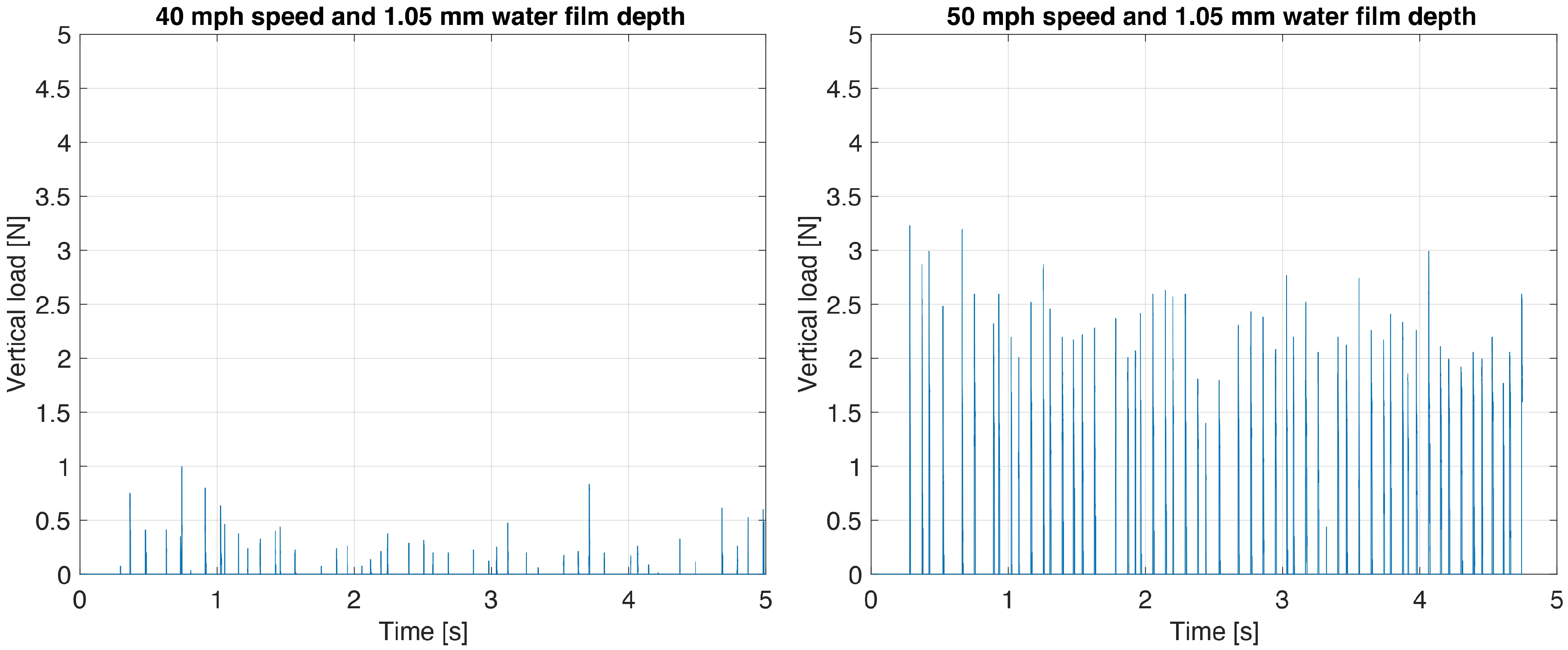

At a water film depth of 1.05 mm, the measured vertical load signal exhibits distinct features between the two tested longitudinal speeds. At 40 mph (64.4 km/h), the signal is characterized by very low peak amplitudes, not exceeding 0.5–1 N. By contrast, at 50 mph (80.5 km/h), the signal displays a marked increase, both in amplitude and in frequency of occurrence. The vertical load peaks regularly exceed 2.0 N, with the highest values approaching 3.5 N. These observations confirm that, for the same controlled water depth, the intelligent tire system correctly detected the expected increase in water lift force associated with a higher longitudinal speed.

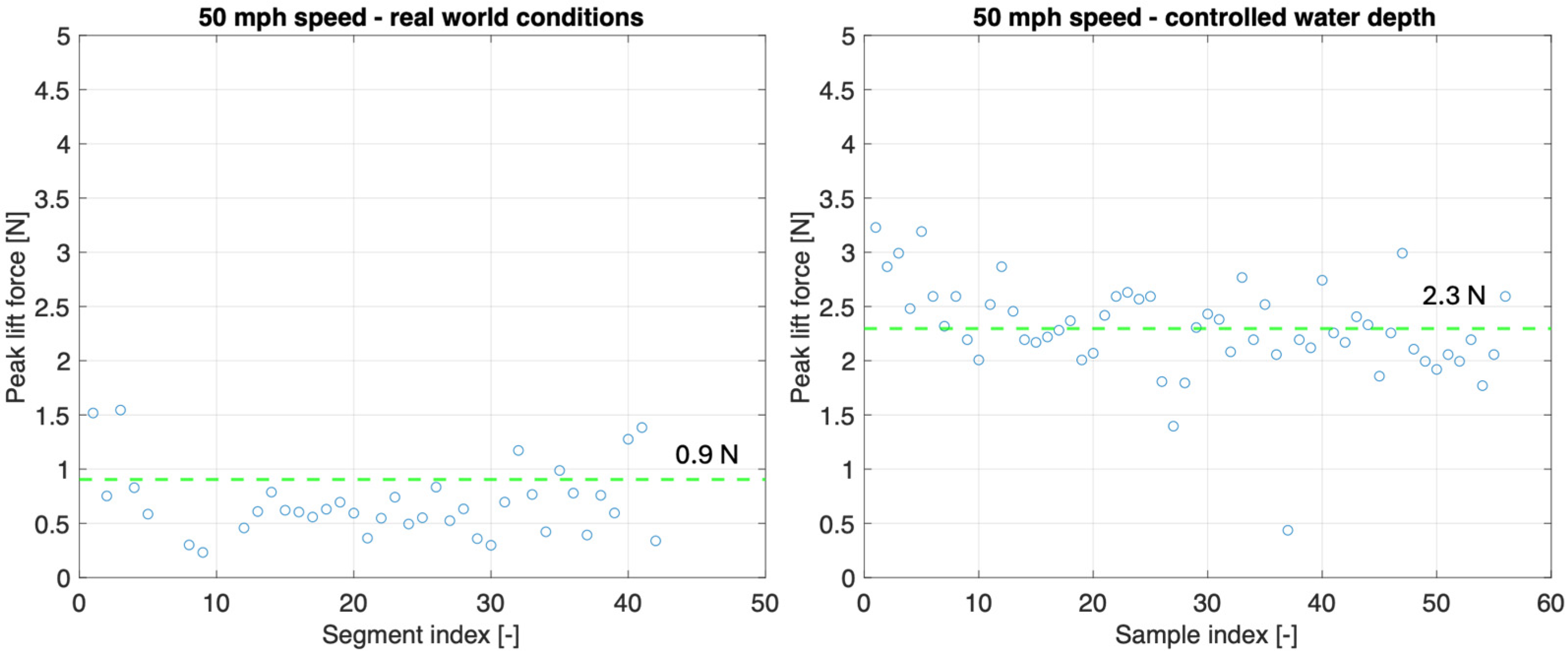

Figure 15 compares the measured peak water lift force at 50 mph (80.5 km/h) for the controlled water depth test conducted on 21 August 2025 and the real-world test conducted on 12 February 2025. Due to the limited amount of data available for the controlled water depth tests, the data set is no longer divided into 1000 sample segments for computing the average peak value.

At a longitudinal speed of 50 mph (64.4 km/h), the measured peak lift force shows a clear dependency on the water depth. Under controlled water depth conditions of 1.05 mm, the average peak lift force reached 2.3 N, whereas under real-world conditions, the average value was only 0.9 N. The significant reduction in the lift force values confirms that the actual water depth encountered during real-world testing was substantially lower than the water depth maintained under controlled conditions. Assuming a linear dependency of lift force on water film depth (for shallow hydroplaning conditions), the measured results suggest that the water depth in real conditions was approximately 0.4 mm, which is consistent with the estimated value reported in

Section 2.1. This outcome indicates that the intelligent tire system is sensitive to water depth variations.

Hermange [

29] analyzed high-speed camera images that capture the contact patch behavior during partial and total hydroplaning, with the camera mounted below a transparent pavement section. To establish a reference surface area,

S0, the tests were conducted at a constant speed of approximately 20 mph (32.2 km/h), where hydroplaning effects are minimal, and the contact patch dimensions are stable. The critical hydroplaning speed was determined as the speed at which the contact surface area,

S, between the tire and the measurement window approaches zero. Some of the data published by Hermange [

29] will be adapted to align with the hydroplaning risk data presented in the previous section. In this study, a ratio of

S/S0 of 0% indicates a 100% hydroplaning risk, while an

S/S0 of 100% corresponds to a 0% hydroplaning risk.

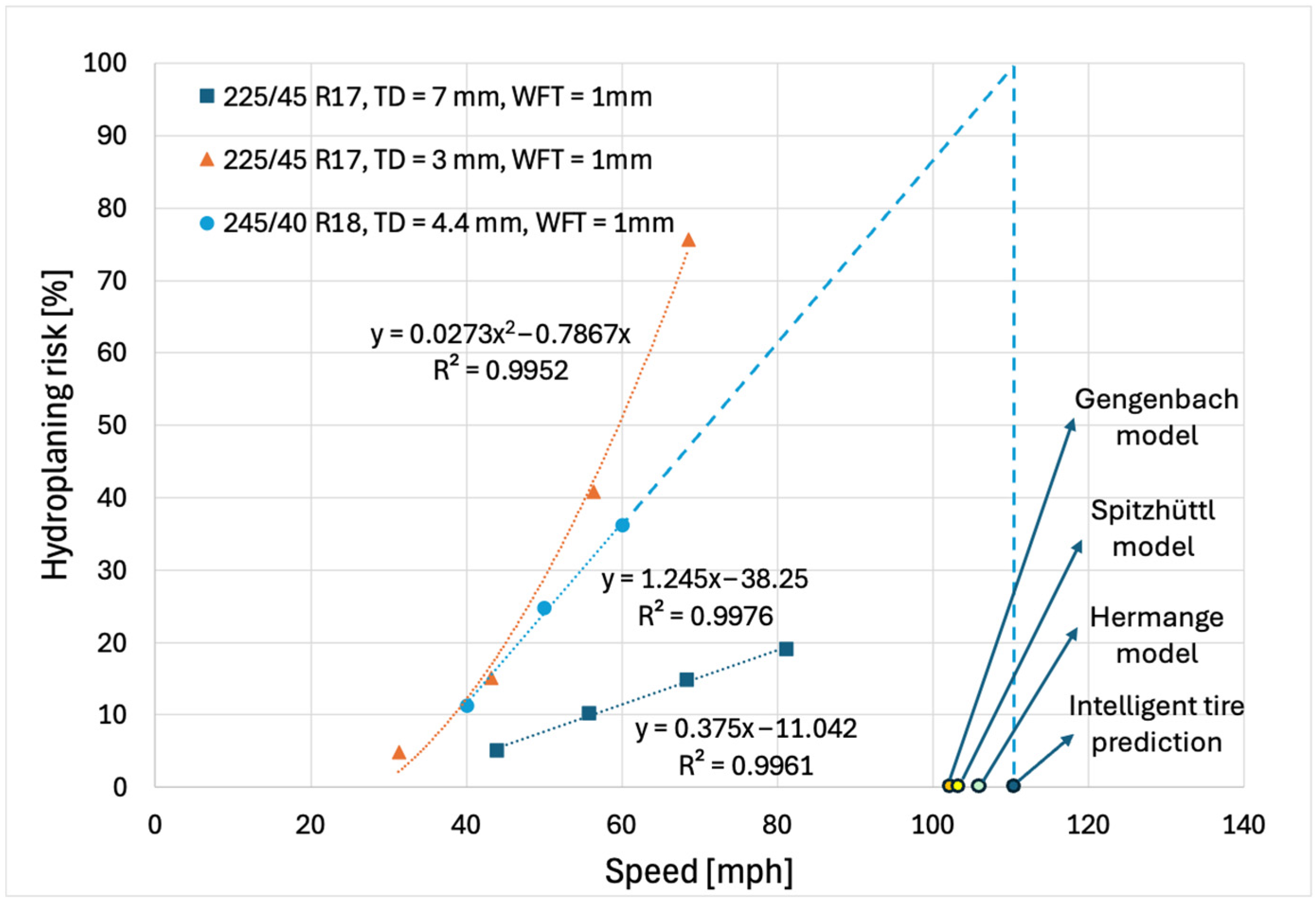

Figure 16 shows the evolution of hydroplaning risk as a function of longitudinal speed for both the tested tire equipped with the FlexiForce sensor and the reference tires from Hermange’s study [

29].

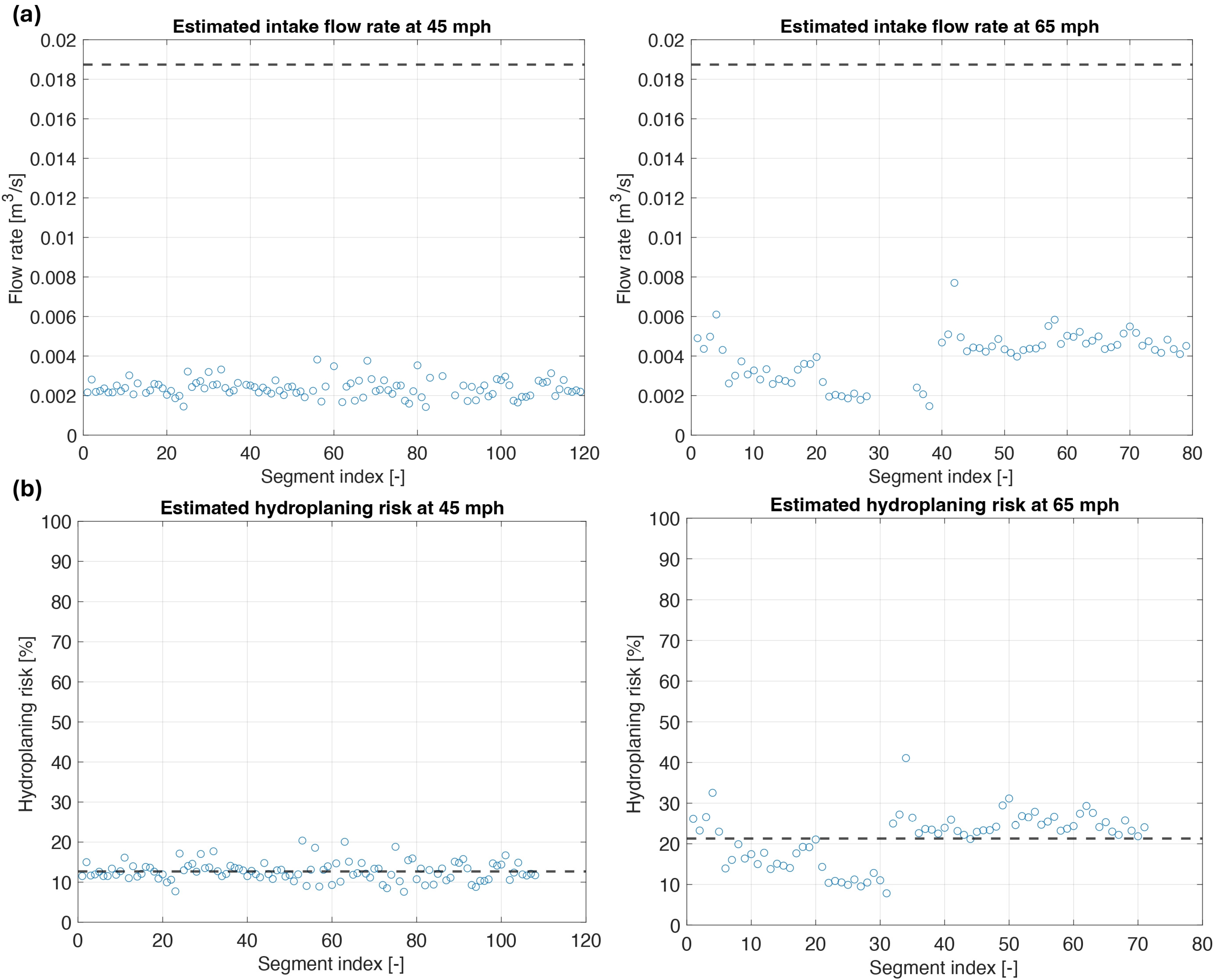

Using the intelligent tire system in controlled water depth conditions, three hydroplaning risk points were measured and analyzed at 40 mph (64.4 km/h), 50 mph (80.5 km/h), and 60 mph (96.6 km/h), following the procedure described in

Section 2.2 and

Section 3.2. The hydroplaning risk data points were collected at the Michelin proving ground in Clermont-Ferrand, France, under a water depth of 1 mm, using two separate tires, one with a tread depth of 7 mm and one with a tread depth of 3 mm. Following Sinnamon groove flow theory [

19], the tire with a 7 mm tread depth is experiencing shallow hydroplaning conditions, where the intake flow rate varies linearly with longitudinal speed, resulting in a linear relationship between hydroplaning risk and vehicle speed. The intelligent tire used for this study also exhibits shallow hydroplaning behavior, and the hydroplaning risk varies linearly with vehicle speed. In contrast, the tire with a 3 mm tread depth is in deep hydroplaning conditions, where a water wedge forms ahead of the contact patch, causing the intake flow rate (and hydroplaning risk) to vary with longitudinal speed squared.

Several important differences should be noted between the instrumented tire and the reference tires. First, the reference tires were tested on a glass panel, which prevents water drainage into pavement asperities. Under real-world conditions, the same tires would likely exhibit lower hydroplaning risk. Second, the cross-sectional width of the test tire was larger, resulting in a wider tread. This characteristic typically reduces hydroplaning performance compared with narrower reference tires [

19,

27]. Third, the inflation pressure of the reference tires was lower (220 kPa) than that of the test tire (280 kPa). However, for shallow water depths, this parameter is not expected to play a significant role in hydroplaning behavior. Fourth, the vertical load applied to the reference tires was not reported, but a qualitative assessment of the test vehicle indicates that it was lower than the load applied to the test tire. A lower vertical load generally reduces hydroplaning performance. The tread designs of the test tire and the reference tire are similar; therefore, the tread pattern is unlikely to account for the observed differences.

Although the test conditions and tire specifications differ, the hydroplaning risk estimation algorithm produces results within the expected range, between those of the Hermange reference tires with tread depths of 3 mm and 7 mm. For all three cases, hydroplaning risk begins to deviate from zero at approximately 30 mph (48.3 km/h), marking the onset of partial hydroplaning. The critical hydroplaning speed predicted by the intelligent tire system (HR = 100%) is 111 mph (178.6 km/h), which is substantially lower than values reported under real-world conditions. This discrepancy further confirms that the effective water depth in real conditions is significantly lower than the controlled depth of 1.05 mm. Using Equation (9) with the same instrumented tire parameters and a water depth of 1.05 mm, the Gengenbach model predicts a critical hydroplaning speed of 102 mph (164.2 km/h). The relative difference between the two predictions is 8%. As in the real-world case, the Gengenbach model yields a lower critical speed compared to the proposed methodology.

Based on experimental data, Hermange [

29] has introduced a new equation for calculating the critical hydroplaning speed

Vp (km/h) as a function of water absorption capability

γ1.

The water absorption capability is defined in the literature [

19] as the ratio between the tire groove capacity

g and the water film depth

h. The tread groove capacity

g is calculated based on average tread depth

TD and contact surface ratio

CSR according to Equation (11) [

20,

29].

For a contact surface ratio of 0.65, an average tread depth of 4.4 mm, and a water depth of 1.05 mm, the water absorption capability γ1 of the intelligent tire is 1.47. Applying the Hermange model (Equation (10)), the predicted critical hydroplaning speed is 106 mph (170.6 km/h). This value remains lower than that predicted by the proposed methodology, but the relative difference is reduced to 5%.

Spitzhüttl [

30] proposed a model similar to that of Hermange for calculating the critical hydroplaning speed

Vp (km/h) as a function of the water absorption capability

γ1 and the tire inflation pressure

P (bar).

For an inflation pressure of 280 kPa (2.8 bar) and assuming the same water absorption capability of 1.47, this model predicts a critical hydroplaning speed of 103 mph (165.8 km/h). The calculated value further supports the accuracy of the intelligent tire system predictions and the proposed hydroplaning risk estimation methodology.

To improve clarity, the validation results presented above can be viewed as three complementary pathways, each supporting a different aspect of the proposed hydroplaning risk estimation method. First, the controlled experimental validation confirms that the intelligent tire system correctly captures the expected increase in water lift force with longitudinal speed and water film depth (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15), demonstrating sensitivity to fundamental hydrodynamic trends. Second, the comparison with published optical measurements of the contact patch (adapted from Hermange [

29]) shows that the hydroplaning risk evolution measured by the instrumented tire falls within the expected range defined by reference tires with different tread depths (

Figure 16), despite differences in tire specifications and test conditions. Third, the comparison between the critical hydroplaning speed predicted by the proposed method and the results obtained from established analytical models (Gengenbach, Hermange, and Spitzhüttl) shows good agreement, with relative differences in the range of 5–8%. Taken together, these three validation pathways confirm that the proposed hydroplaning risk estimation methodology is reliable and robust.

5. Conclusions

This study developed and validated a real-time hydroplaning risk estimation methodology leveraging an intelligent tire system instrumented with a FlexiForce sensor. This work demonstrates, for the first time, a practical method for measuring the hydrodynamic lift generated in one of the tire tread grooves in real-world operation conditions. An analytical water intake flow rate model was derived based on the lift force model developed by Horne, providing a robust estimate of the amount of water that the tire needs to evacuate. The hydroplaning risk index is then obtained by computing the ratio between the estimated intake flow rate and the choke flow rate limit of the tire. In contrast to most existing hydroplaning studies, which focus on deep water conditions and rely on the formation of a water wedge in front of the contact patch, the method developed in this work is not dependent on this mechanism. Due to the position of the sensor on the exterior of the tire carcass, the intelligent tire is also able to estimate the hydroplaning risk in shallow water conditions where the water wedge effect is not always present. Furthermore, the direct measurement of the water lift force provides physically meaningful information about the hydroplaning mechanism. This represents an advantage compared to methods that rely on indirect measurements to estimate the risk of hydroplaning.

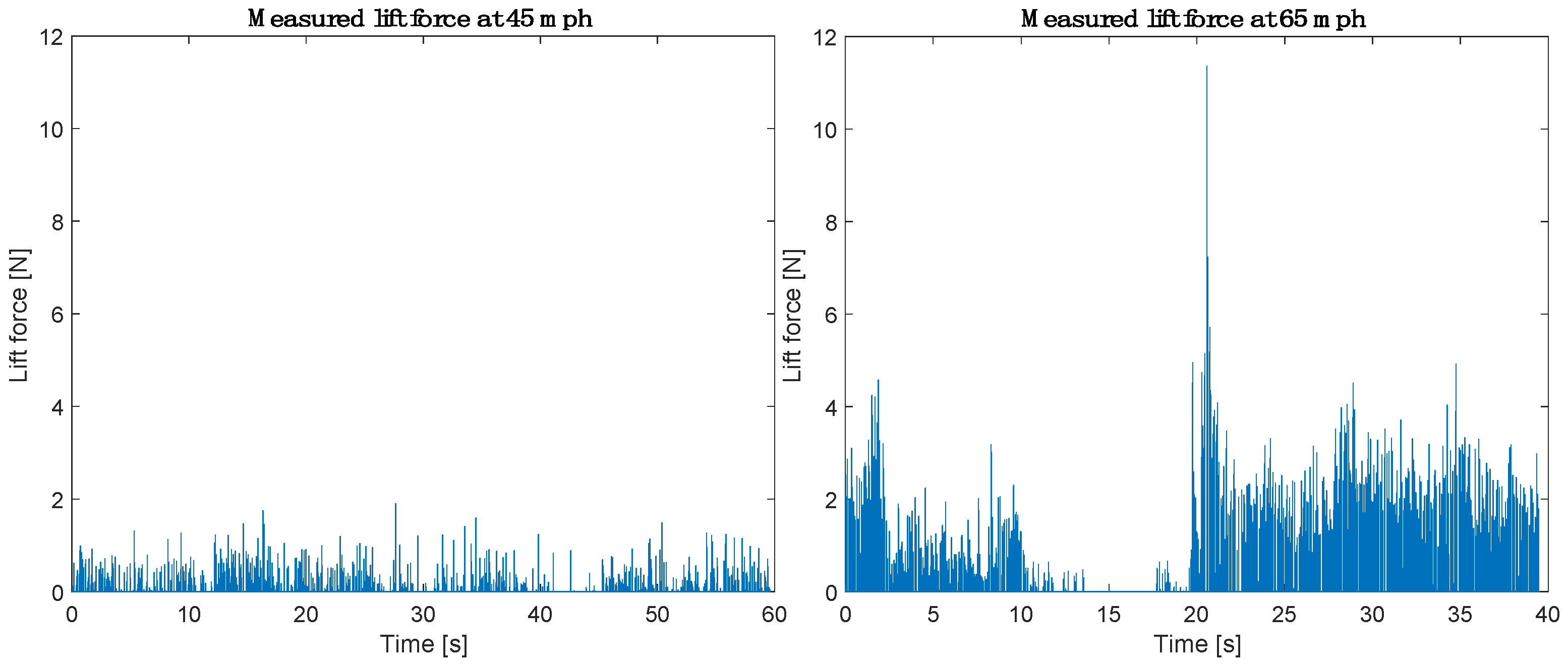

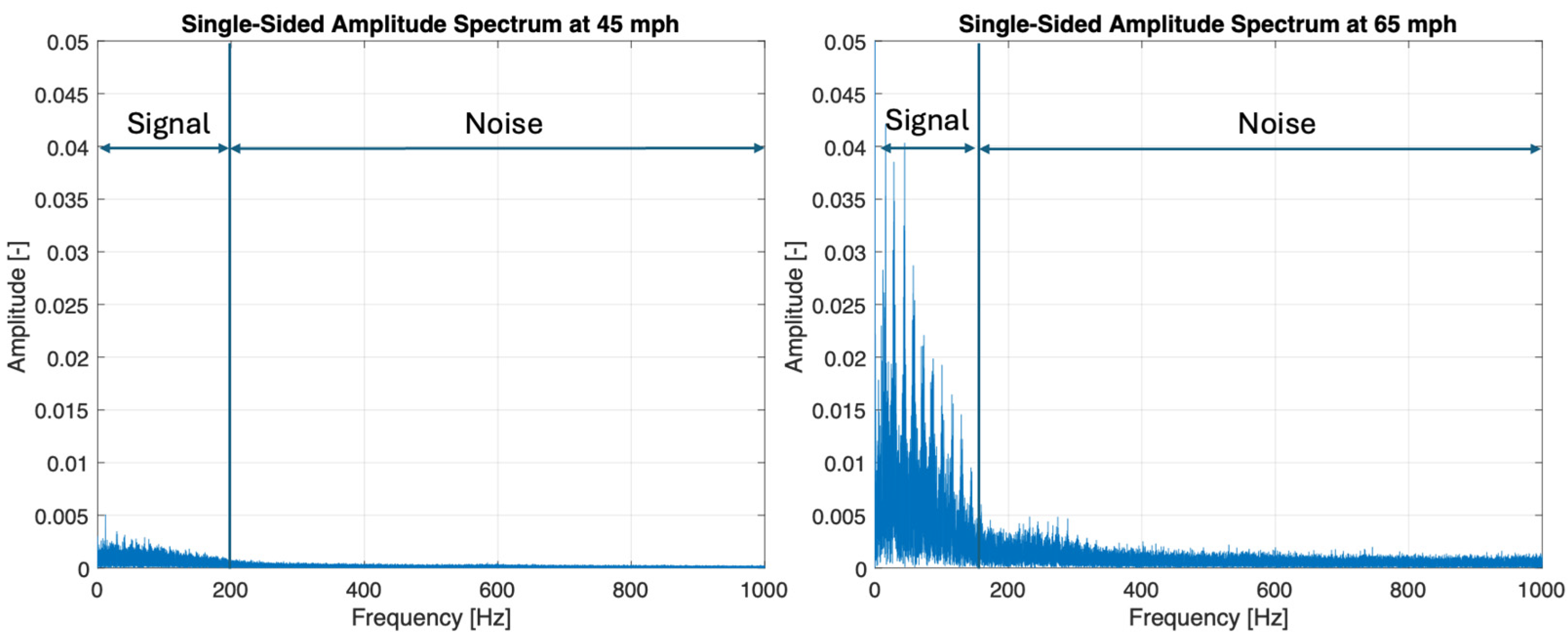

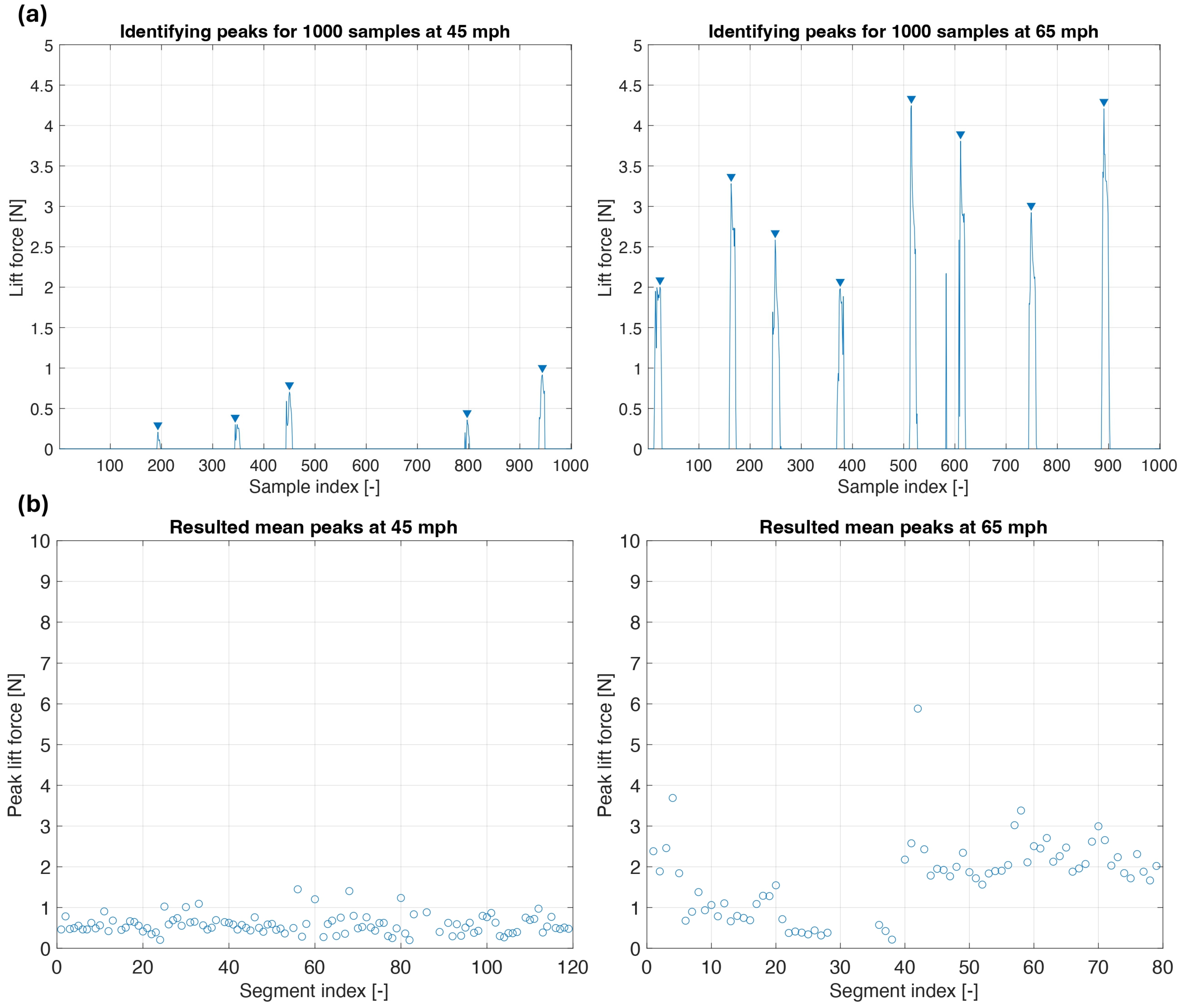

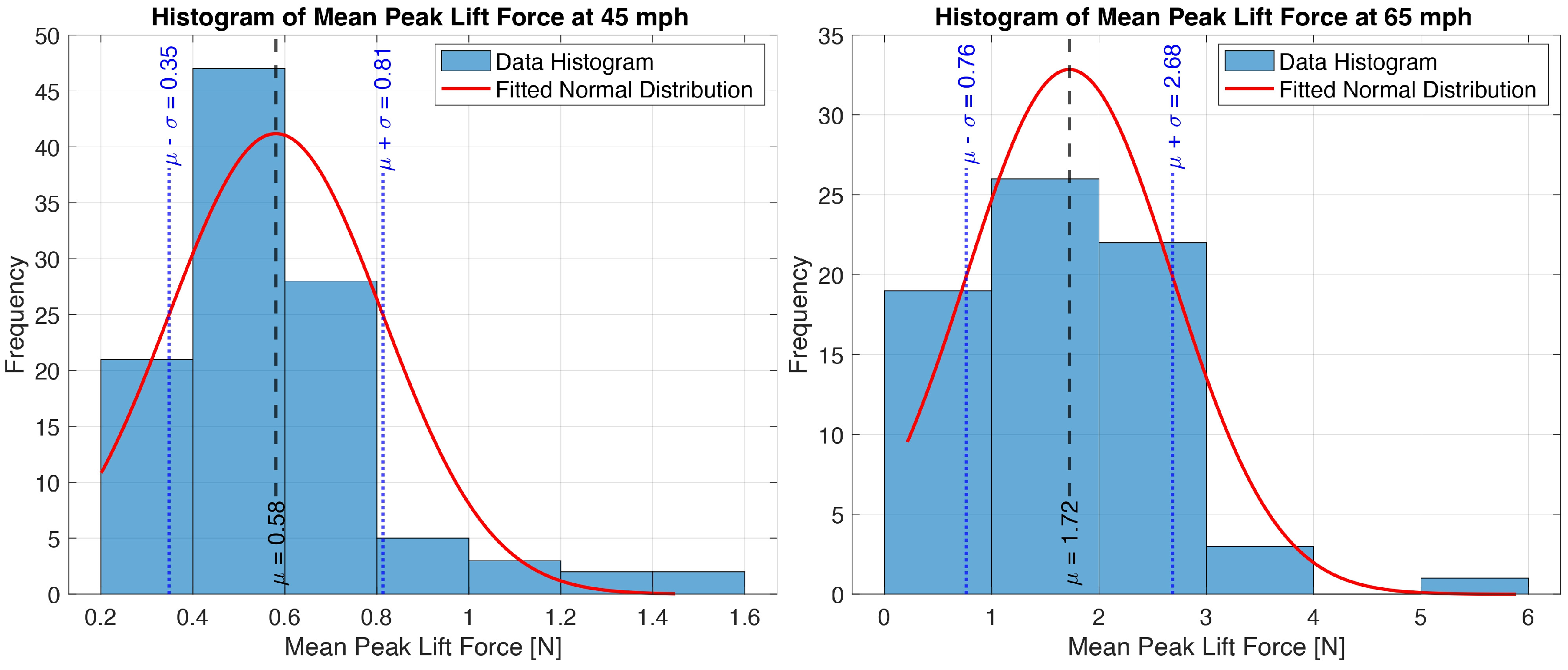

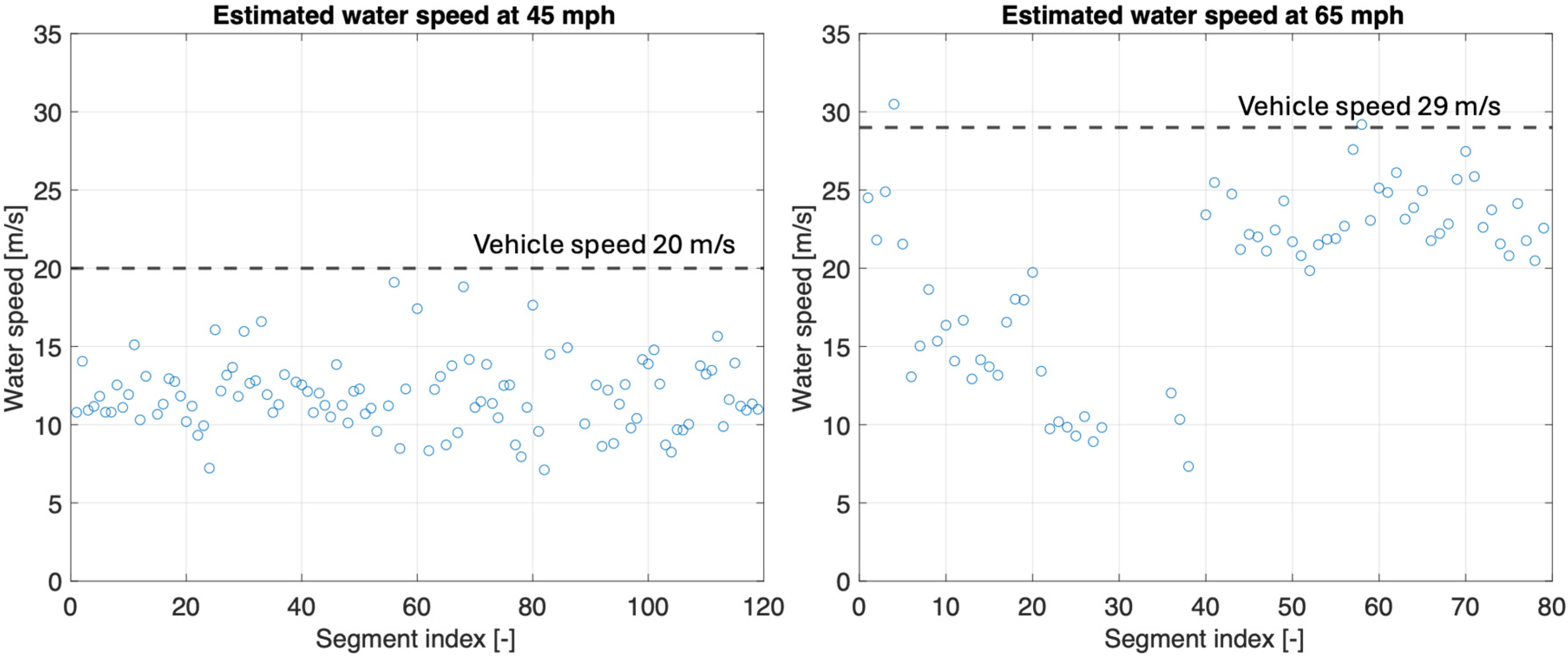

The proposed methodology has been applied to two data sets obtained from real-world rolling conditions at 45 mph and 65 mph, which resulted in mean hydroplaning risk values of 12.6% and 21.3%. These values are well below the 100% threshold for total hydroplaning and are consistent with previous empirical predictions, which indicated that the same tire would not reach critical conditions until approximately 190 mph (305.8 km/h) for a 0.3 mm water film depth. Frequency-domain analysis confirmed strong signal-to-noise ratios (14.6 dB at 45 mph (72.4 km/h) and 18.2 dB at 65 mph (104.6 km/h)), ensuring reliable measurement of the lift force signal even in real-world conditions.

Wet rolling tests were conducted under controlled water depth conditions of 1.05 mm at the Michelin Laurens Proving Grounds in South Carolina. Validation was performed by comparing the hydroplaning risk estimated by the intelligent tire system with data obtained from the literature through an optical imaging method. Despite differences in tire construction, loading, and test surfaces, the hydroplaning risk predicted by the intelligent tire showed close agreement with the optical imaging results reported by Hermange. Specifically, the intelligent tire, with a tread depth of 4.4 mm, exhibited hydroplaning risk levels between those observed for reference tires with 7 mm and 3 mm tread depths. Furthermore, the critical hydroplaning speed estimated by the intelligent tire system was 111 mph (178.6 km/h), falling within 5–8% of the predictions made using analytical models proposed by Gengenbach, Hermange, and Spitzhüttl.

Beyond its scientific contributions, the proposed algorithm offers a data-driven approach for estimating hydroplaning risk that can be embedded in future intelligent tire designs to enhance advanced driver-assistance systems (ADASs). A real-time hydroplaning risk signal could issue visual warnings and also inform the stability management system, giving drivers and automated vehicles additional reaction time before grip is compromised.

Future work should broaden the test matrix to include a wider range of water film depths, varied tread patterns, and the effects of inflation pressure and vertical load. For commercial implementation, future research should also assess long-term sensor durability and calibration drift. Additionally, recent advances in machine learning techniques could be coupled with the analytical flow model to improve accuracy across a wider operating envelope.