Image-Based Evaluation Method for the Shape Quality of Stacked Aggregates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Aggregate Image Acquisition

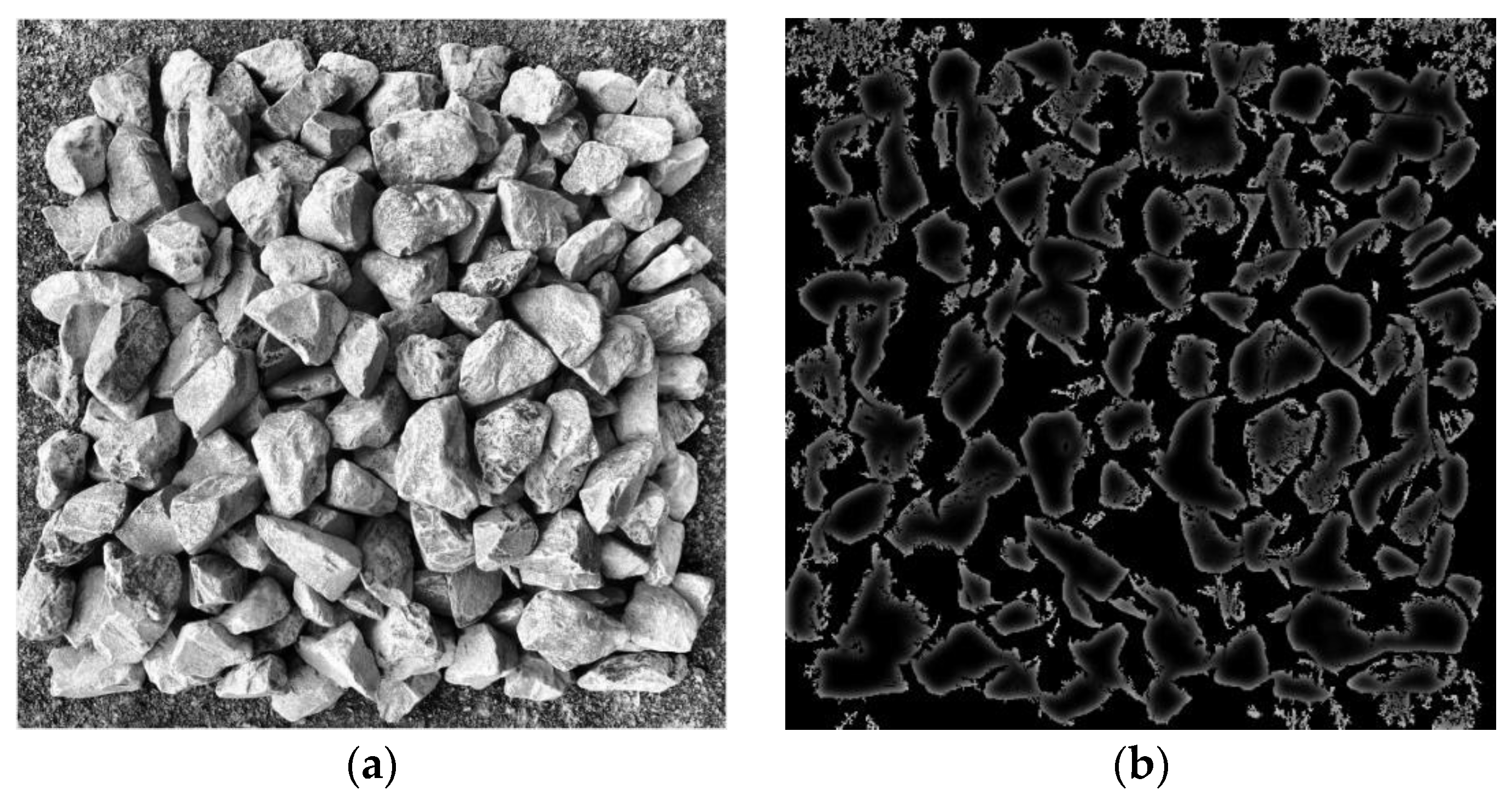

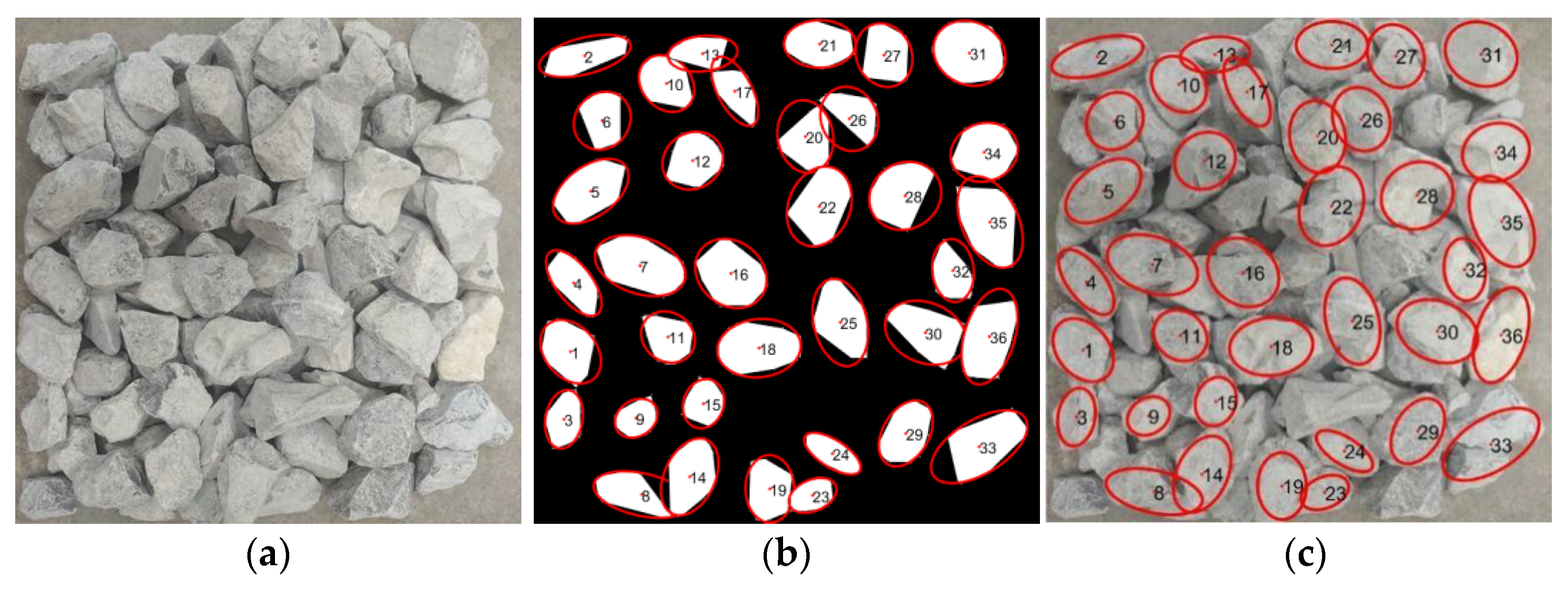

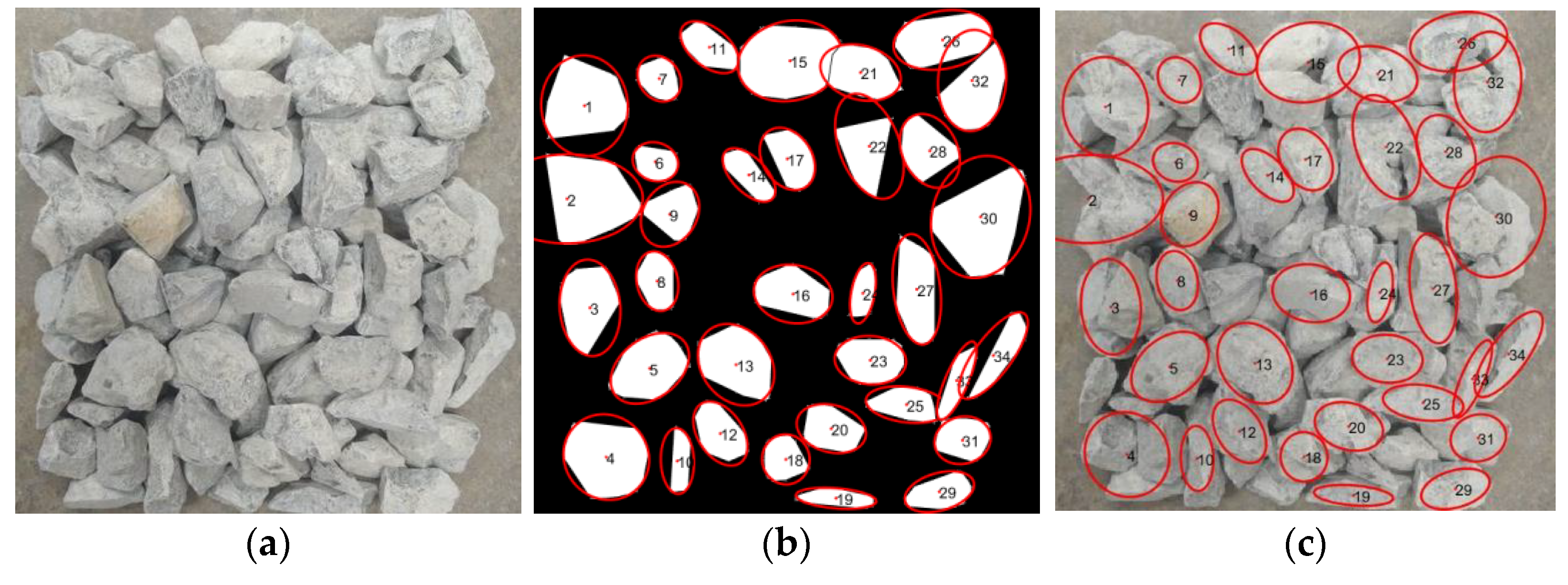

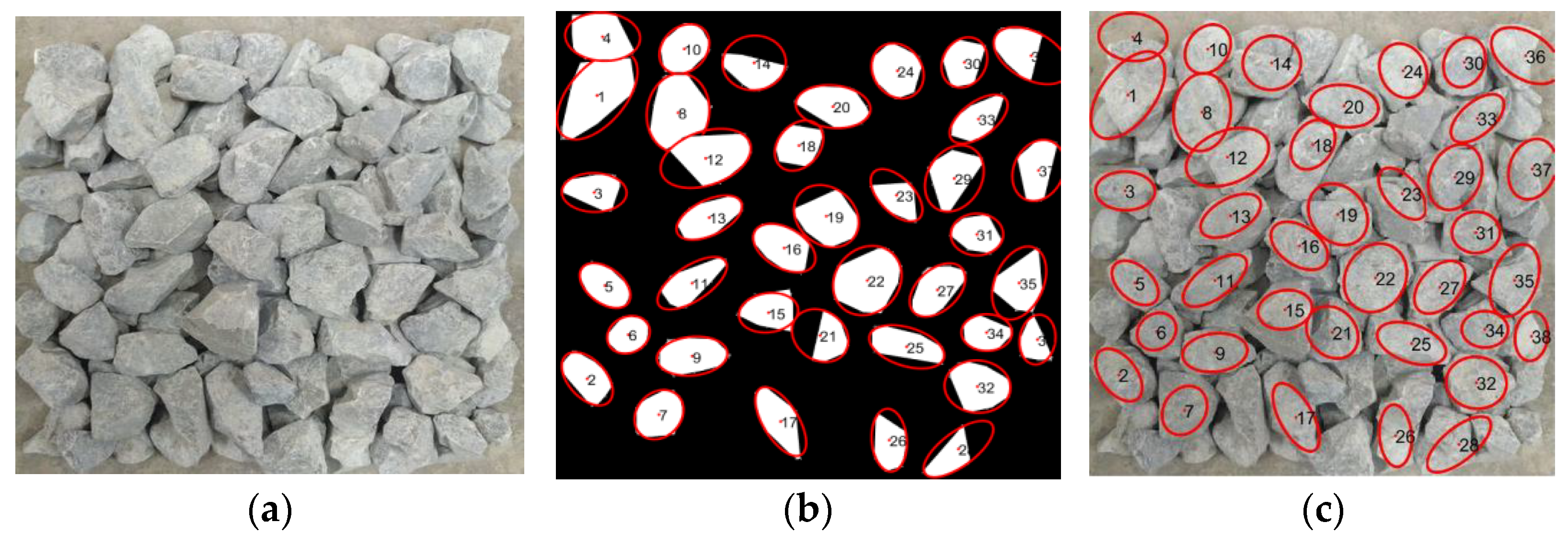

2.2. Image Preprocessing and Segmentation

2.2.1. Image Enhancement

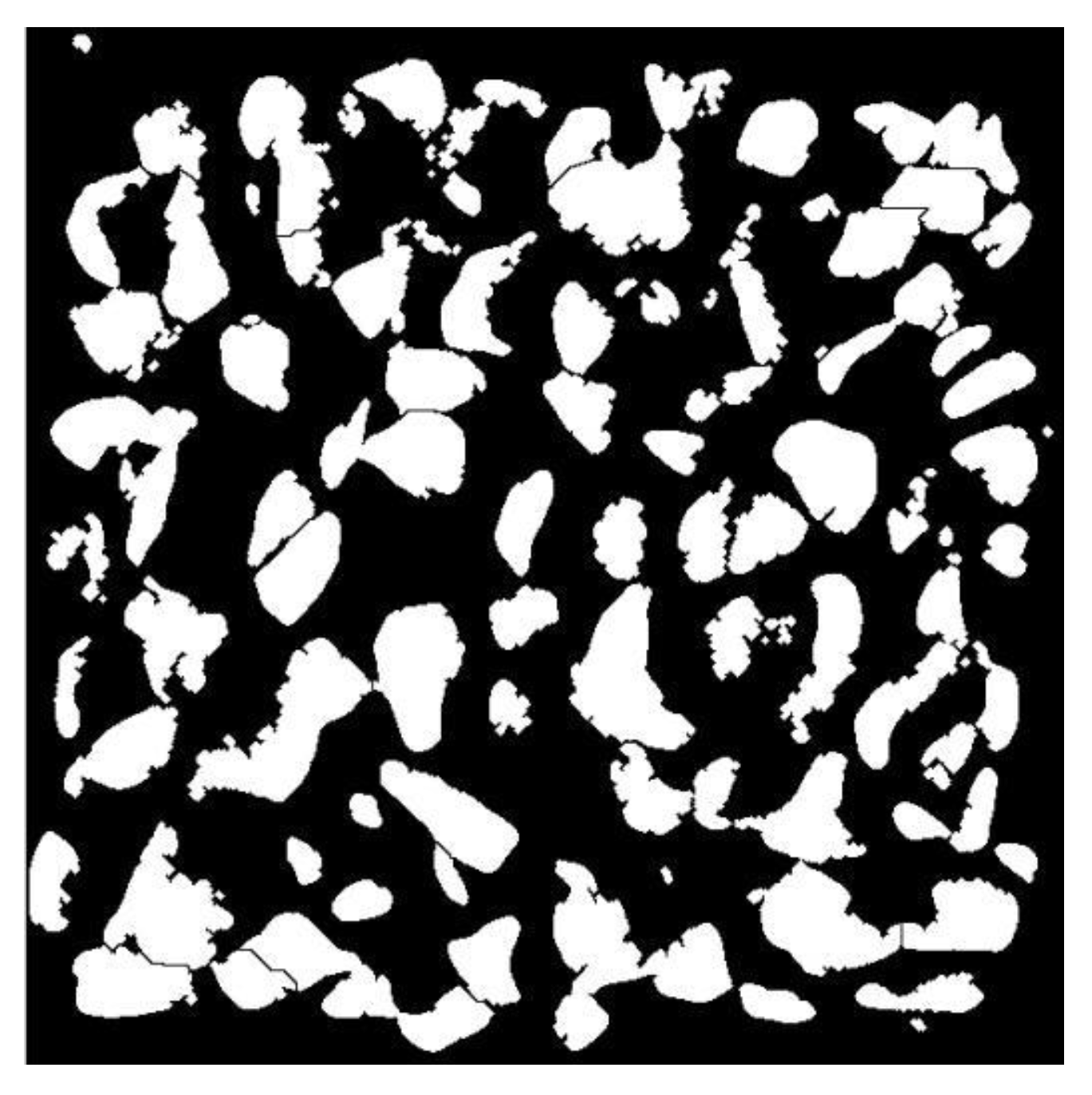

2.2.2. Edge Detection and Segmentation

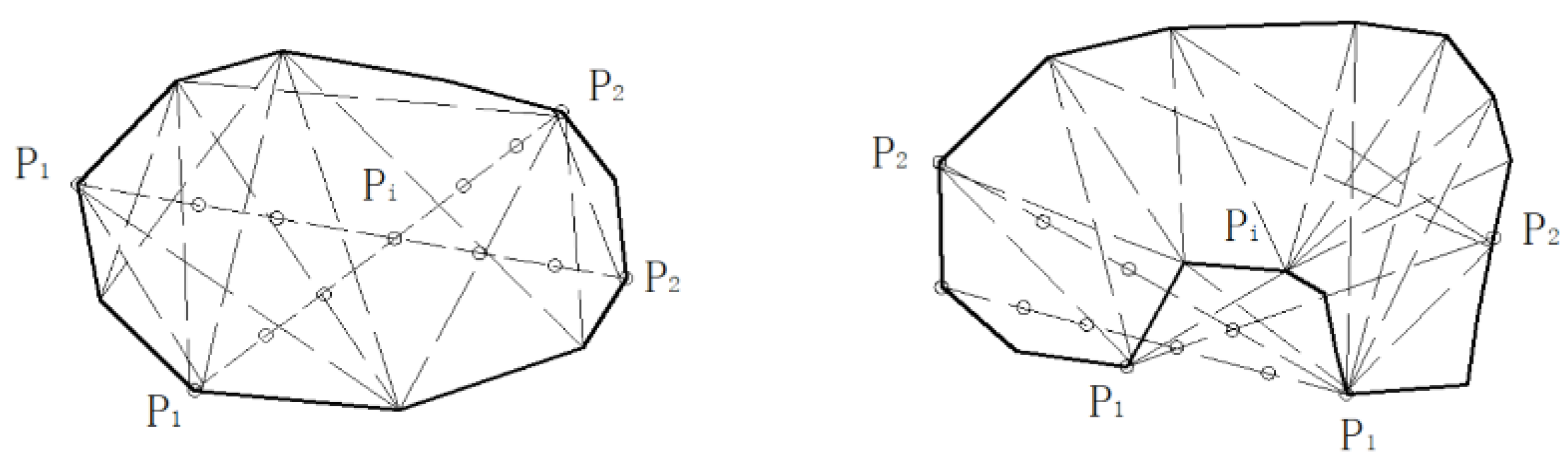

2.2.3. Contour Extraction

- (1)

- Reference point selection: Identify the point P0 with the minimum y-coordinate as the base point.

- (2)

- Polar angle sorting: Connect all other points to P0 and sort them by polar angle relative to the x-axis.

- (3)

- Counterclockwise traversal: Sequentially traverse the sorted points in counterclockwise order, adding points to the convex hull.

- (4)

- Convexity check: Remove intermediate points that violate the convex condition, ensuring the final polygon remains convex.

2.3. Shape Evaluation Method and Standard

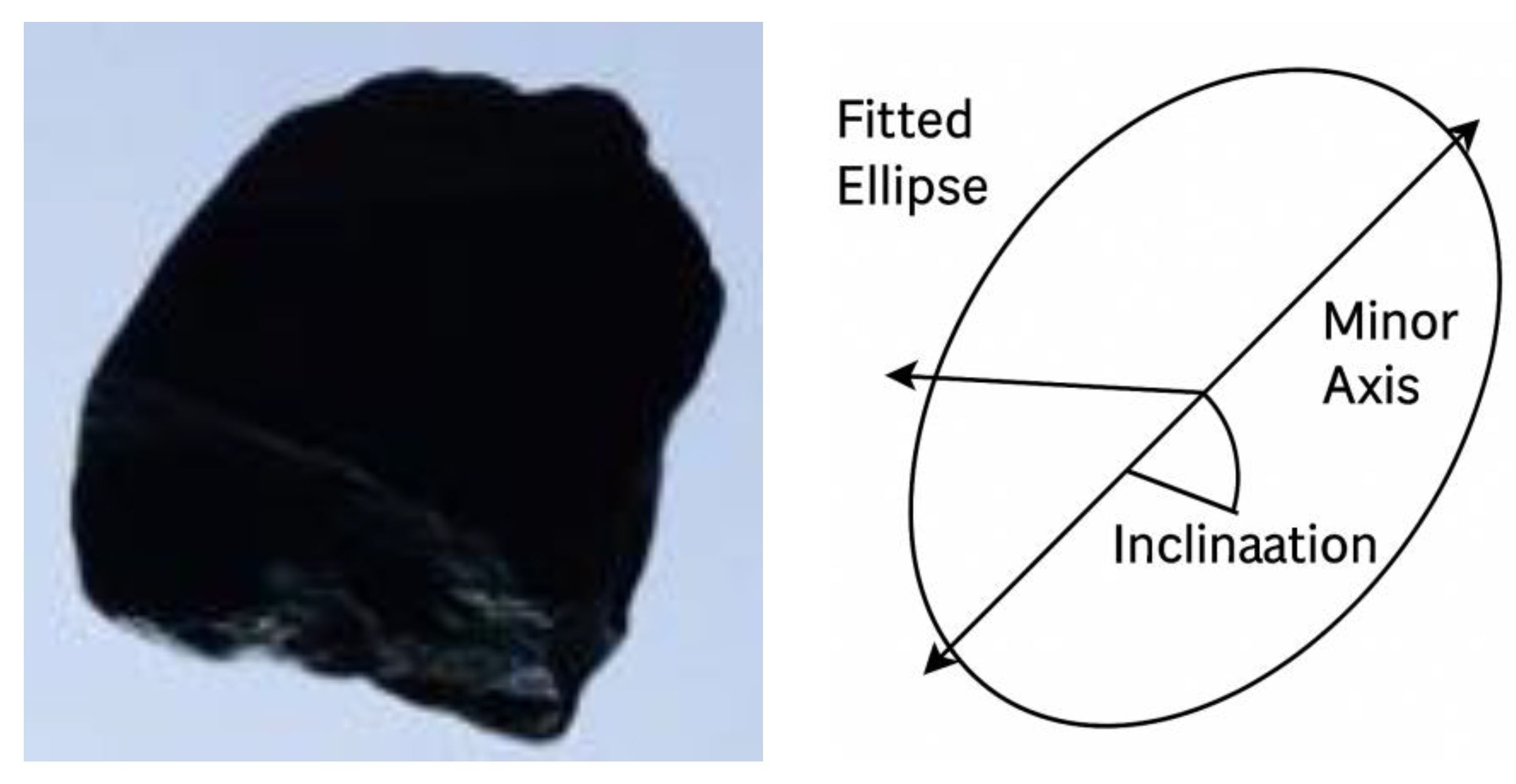

2.3.1. Particle-Level Shape Descriptors

2.3.2. Batch-Level Statistical Metrics

2.3.3. Establishment of Evaluation Standard

3. Results

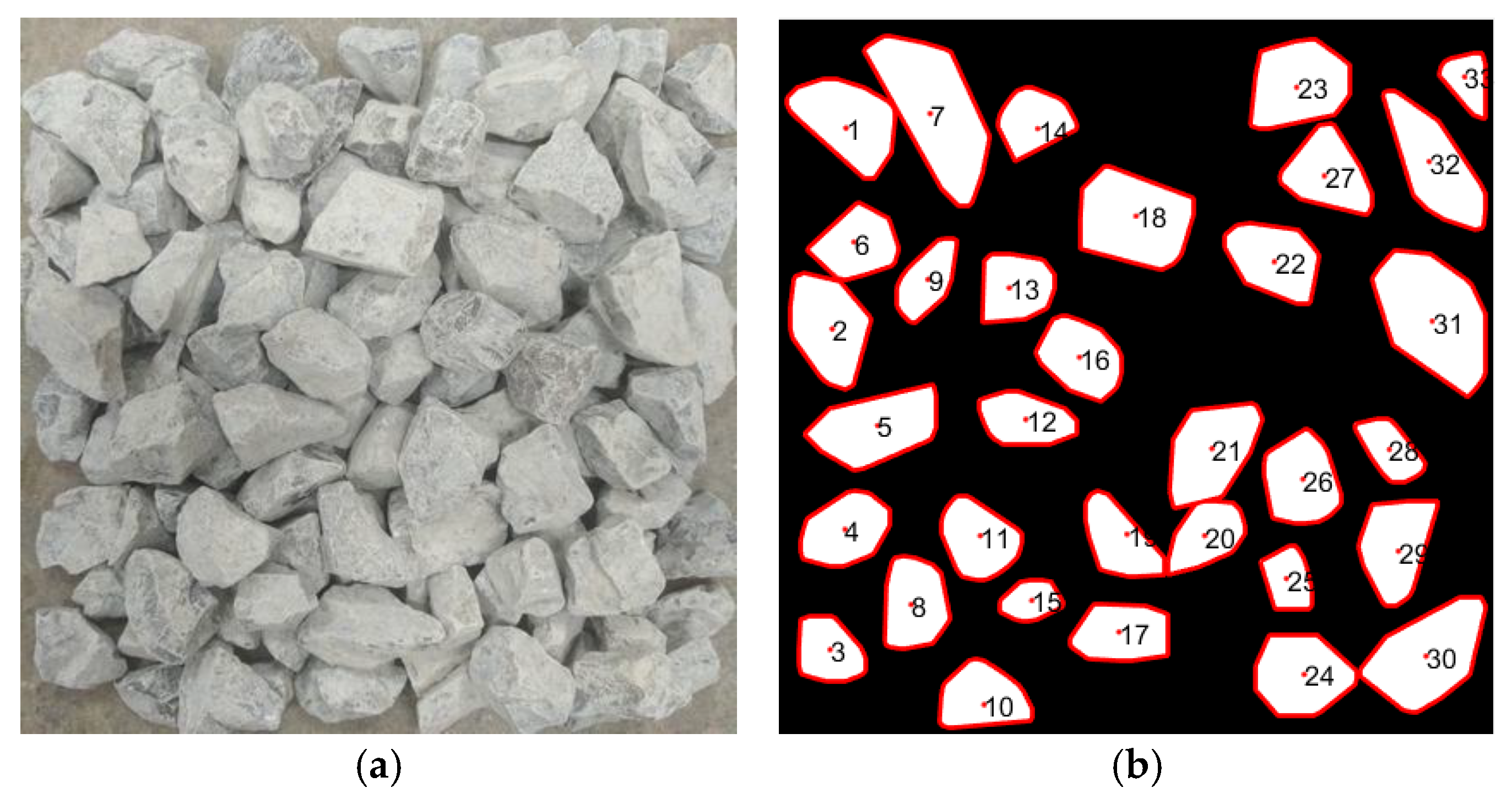

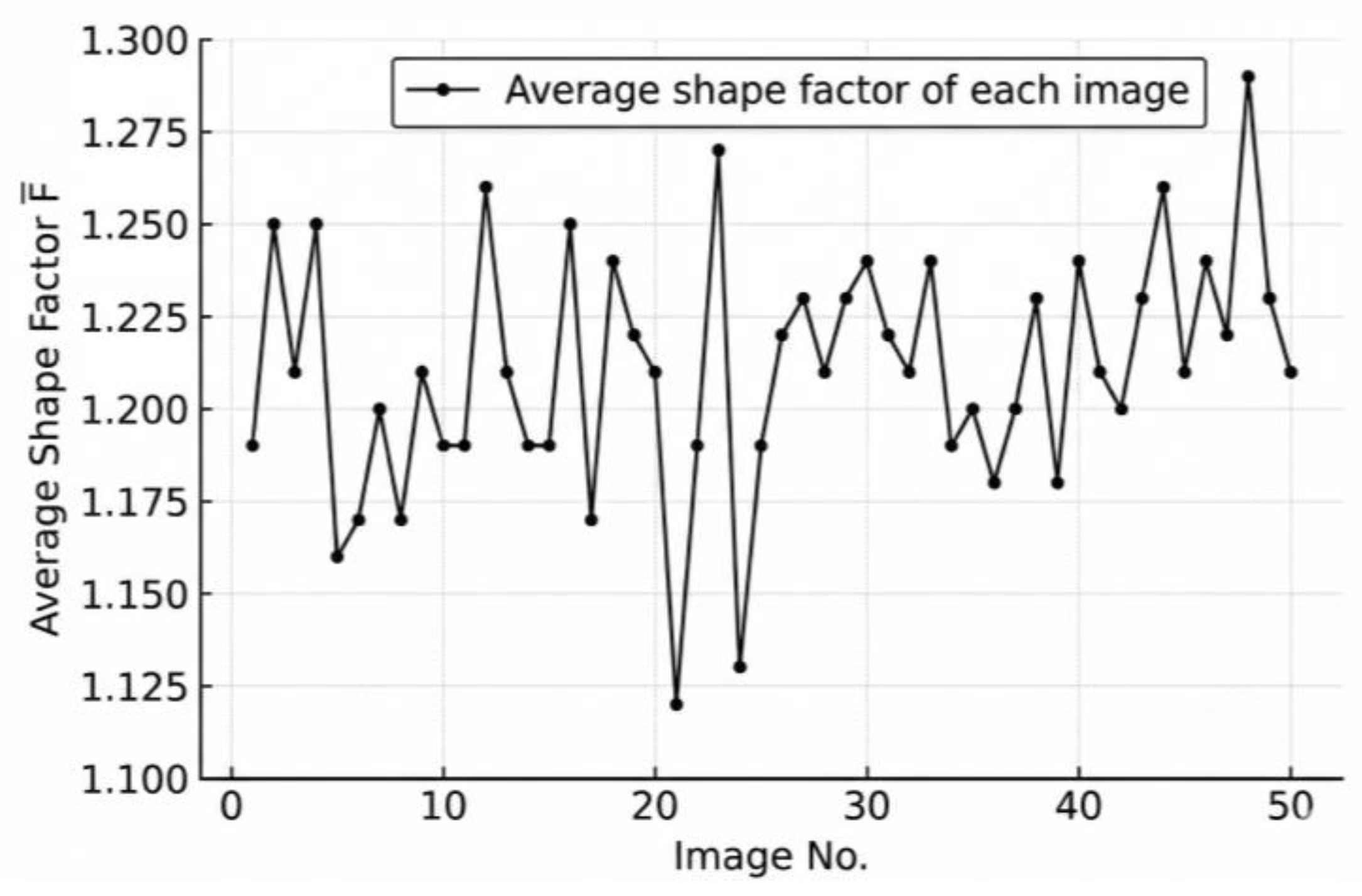

3.1. Particle-Level Results

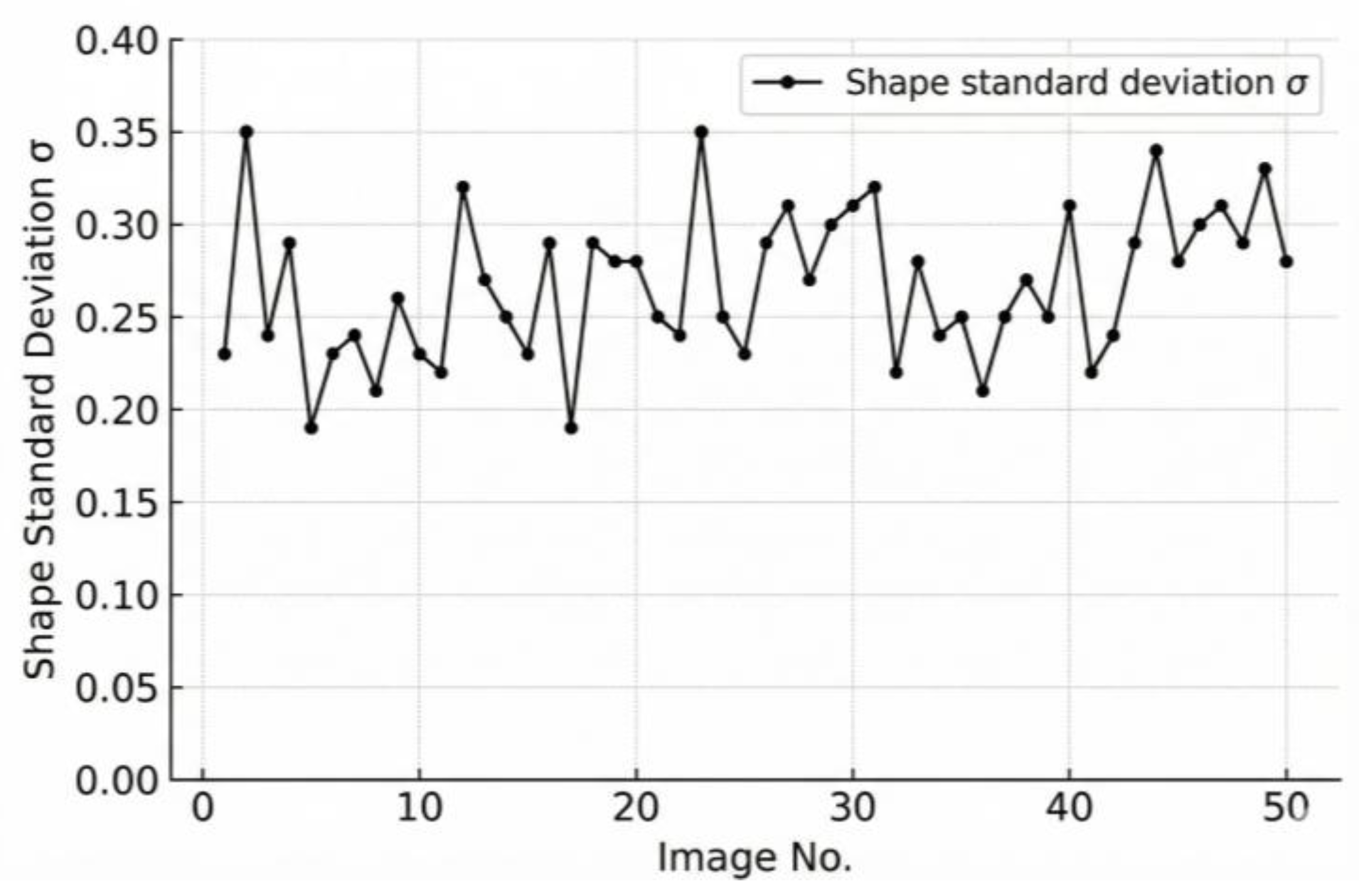

3.2. Validation of Batch-Level Statistical Metrics

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The developed image-processing pipeline integrates enhancement, Gaussian filtering, contour extraction using the Graham scan convex hull algorithm, and morphological parameter computation, enabling accurate boundary identification even under complex particle overlap conditions.

- (2)

- The morphological characteristics of individual aggregates were quantified using the equivalent ellipse method, in which the shape factor () and its standard deviation () were introduced as the key parameters reflecting particle uniformity and overall shape quality. Based on the analysis of 50 stacked aggregate images containing 1050 particles, the results demonstrate that effectively characterizes the dispersion degree of particle geometries—smaller values correspond to more uniform and better-shaped aggregates, while larger values indicate greater shape variability and poorer overall quality.

- (3)

- According to the experimental data, an evaluation criterion for batch-level aggregate shape quality was established. When lies between 0 and 0.32, the aggregates exhibit excellent shape uniformity; values between 0.32 and 0.42 correspond to good shape quality; and values greater than 0.42 indicate poor shape consistency. This -based evaluation index provides a reliable and interpretable measure for aggregate shape assessment and can be further extended to real-time monitoring of aggregates on conveyor belts, supporting intelligent quality control in material production and pavement construction.

- (4)

- Although the proposed method demonstrates satisfactory performance in stacked aggregate detection, there is still room for further improvement. The classification thresholds proposed in this study (excellent, good, and poor) were derived based on the observed statistical distribution of the shape factor and its consistency with manually measured particle morphology. Although no external benchmark currently exists for stacked aggregate morphology evaluation, the proposed thresholds align with engineering judgment commonly used in asphalt mixture quality control. Moreover, the consistency between the classification results and manual inspection confirms the rationality of the threshold settings. Future work will include external validation using larger datasets and cross-validation with other digital aggregate characterization methods.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Shi, L.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y.; Nie, W. Study on the Influence of Coarse Aggregate Morphology on the Meso-Mechanical Properties of Asphalt Mixtures Using Discrete Element Method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawenda, T.; Surowiak, A.; Krawczykowska, A.; Stempkowska, A.; Niedoba, T. Analysis of the Aggregate Production Process with Different Geometric Properties in the Light Fraction Separator. Materials 2022, 15, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stempkowska, A.; Gawenda, T.; Naziemiec, Z.; Ostrowski, K.A.; Saramak, D.; Surowiak, A. Impact of the Geometrical Parameters of Dolomite Coarse Aggregate on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Preplaced Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshan, A.; Abdelrahman, M. Influence of Aggregate Properties on Skid Resistance of Pavement Surface Treatments. Coatings 2024, 14, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Tao, Y.; Liu, K. Review of Visualization Technique and Its Application of Road Aggregates Based on Morphological Features. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.; Pouteau, P.; Suquet, P.; Vanel, L. Image-Based Gradation and Aggregate Characterisation: Case of Cement-Stabilised Quarry Fines. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 2185–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, X.; Ni, X.; Koukkari, P.; He, Y. Analysis of Particle Size Distribution of Coke on Blast Furnace Belt Using Object Detection. Processes 2022, 10, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ren, W.; Jiang, T.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Influence of Morphological Characteristics of Coarse Aggregates on Skid Resistance of Asphalt Pavement. Materials 2023, 16, 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M.; Ning, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, K.; Long, Y. A Novel Method for Predicting Coarse Aggregate Particle Size Distribution Based on Segment Anything Model and Machine Learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 429, 136429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, G.; Hyndman, A.; Moyle, S. Fast Inspection for Size-Based Analysis in Aggregate Production Using 2D Vision. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2015, 26, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Pei, L.; Li, W.; Hao, X. Classification of Coarse Aggregate Particle Size Based on Deep Residual Network. Symmetry 2022, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.; Soille, P. Watersheds in Digital Spaces: An Efficient Algorithm Based on Immersion Simulations. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1991, 13, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F. The Watershed Concept and Its Use in Segmentation: A Brief History. In Mathematical Morphology: From Theory to Applications; Najman, L., Talbot, H., Eds.; ISTE: Washington, DC, USA; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, R.L. An Efficient Algorithm for Determining the Convex Hull of a Finite Planar Set. Inf. Process. Lett. 1972, 1, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igathinathane, C.; Pordesimo, L.O.; Columbus, E.P.; Batchelor, W.D.; Methuku, S.R. Shape Identification and Particle Size Distribution from Basic Shape Parameters Using ImageJ. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 63, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Basset, J.M.; Lemaire, J. A Machine Vision Approach to the Grading of Crushed Aggregate (On-belt Camera). Mach. Vis. Appl. 2005, 16, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, D.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X. A deep learning-based framework for detecting coarse aggregate morphology in asphalt mixtures. Autom. Constr. 2023, 151, 104933. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Actual Length (mm) | Elliptical Major Axis (mm) | Relative Error (%) | Actual Width (mm) | Elliptical Minor Axis(mm) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32.15 | 32.10 | 0.15 | 24.65 | 24.97 | 1.32 |

| 2 | 37.01 | 38.91 | 5.12 | 22.07 | 20.47 | 7.24 |

| 3 | 38.87 | 28.49 | 26.70 | 24.08 | 20.74 | 13.87 |

| 4 | 36.76 | 34.10 | 7.25 | 24.72 | 20.46 | 17.22 |

| 5 | 39.57 | 36.41 | 7.99 | 29.94 | 24.60 | 17.85 |

| 6 | 26.51 | 29.03 | 9.50 | 22.23 | 25.72 | 15.68 |

| 7 | 28.15 | 38.74 | 37.63 | 23.96 | 26.30 | 9.76 |

| 8 | 33.64 | 40.22 | 19.57 | 22.62 | 22.31 | 1.38 |

| 9 | 32.51 | 24.49 | 24.67 | 24.76 | 20.34 | 17.83 |

| 10 | 36.09 | 29.37 | 18.62 | 26.68 | 24.34 | 8.75 |

| 11 | 30.03 | 27.73 | 7.66 | 24.17 | 24.08 | 0.36 |

| 12 | 32.93 | 29.66 | 9.93 | 24.41 | 26.09 | 6.89 |

| 13 | 29.68 | 31.71 | 6.84 | 19.8 | 20.20 | 2.00 |

| 14 | 37.21 | 35.13 | 5.60 | 23.43 | 24.80 | 5.83 |

| 15 | 36.06 | 25.89 | 28.21 | 27.03 | 21.68 | 19.81 |

| 16 | 31.95 | 33.70 | 5.47 | 28 | 28.50 | 1.79 |

| 17 | 42.15 | 33.54 | 20.42 | 22.05 | 19.88 | 9.83 |

| 18 | 39.3 | 35.86 | 8.75 | 26.52 | 26.89 | 1.40 |

| 19 | 35.62 | 30.96 | 13.07 | 28.59 | 24.19 | 15.38 |

| 20 | 34.67 | 32.62 | 5.92 | 28.35 | 26.19 | 7.62 |

| 21 | 39.13 | 32.27 | 17.53 | 30.33 | 23.74 | 21.72 |

| 22 | 33.45 | 35.31 | 5.56 | 29.64 | 28.03 | 5.43 |

| 23 | 40.33 | 25.97 | 35.60 | 28.11 | 19.00 | 32.41 |

| 24 | 35.72 | 30.25 | 15.32 | 27.6 | 17.84 | 35.36 |

| 25 | 34.58 | 37.25 | 7.73 | 32.56 | 25.47 | 21.76 |

| …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… |

| 1046 | 36.79 | 43.13 | 17.22 | 29.94 | 30.23 | 0.95 |

| 1047 | 30.02 | 39.64 | 32.04 | 24.09 | 29.83 | 23.84 |

| 1048 | 48.99 | 38.90 | 20.61 | 30.42 | 25.90 | 14.86 |

| 1049 | 37.45 | 31.97 | 14.64 | 23.57 | 22.85 | 3.06 |

| 1050 | 39.4 | 35.49 | 9.92 | 20.11 | 23.97 | 19.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, S.; Zeng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, B. Image-Based Evaluation Method for the Shape Quality of Stacked Aggregates. Sensors 2025, 25, 7261. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237261

Ren S, Zeng S, Zhou Y, Peng Y, Liu B. Image-Based Evaluation Method for the Shape Quality of Stacked Aggregates. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7261. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237261

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Shaobo, Sheng Zeng, Yi Zhou, Yuming Peng, and Binqing Liu. 2025. "Image-Based Evaluation Method for the Shape Quality of Stacked Aggregates" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7261. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237261

APA StyleRen, S., Zeng, S., Zhou, Y., Peng, Y., & Liu, B. (2025). Image-Based Evaluation Method for the Shape Quality of Stacked Aggregates. Sensors, 25(23), 7261. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237261