Mechanical FBG-Based Sensor for Leak Detection in Pressurized Pipes: Design, Modal Tuning, and Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Modal analysis of the bare pipe to identify natural frequencies and the spatial distribution of antinodes and nodes.

- Design of Experiments (DOE) evaluating the influence of the fiber free length L and proof mass diameter D on the natural frequencies of the fiber–mass subsystem.

- Assembly of the coupled pipe–sensor FEM model, including bonded contact at the pipe-base interface, rigid joints at the fiber clamps, and a lumped mass at the fiber midpoint.

- Generation of the equivalent excitation using CFD-derived pressure fields to define a localized 0.1 MPa pressure patch at the leak position.

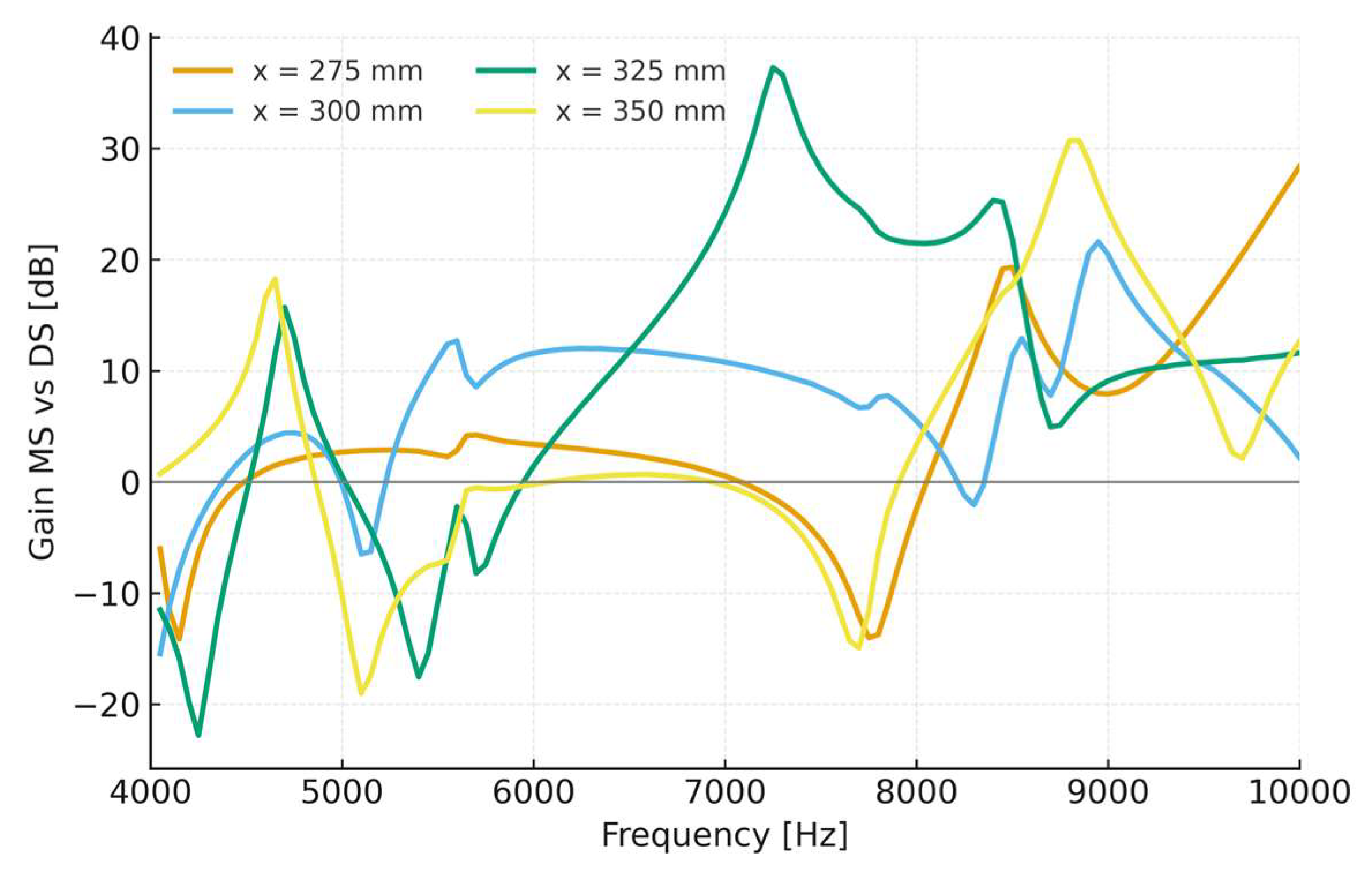

- Harmonic response simulations of both the directly bonded FBG (DS) and the mechanical sensor (MS) under identical excitation conditions.

- Computation of the strain amplification.

- Experimental validation comparing the simulated frequency response with measured spectrograms during controlled leak events.

2. Materials and Methods

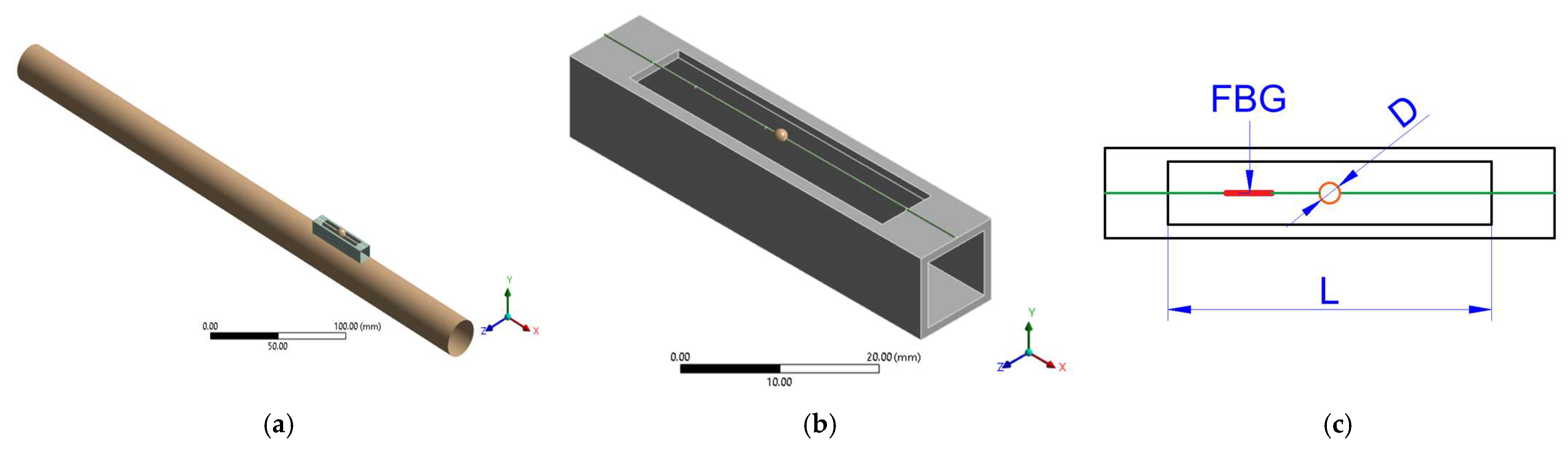

2.1. Geometry

- DS: an FBG directly bonded to the outer wall of the pipe, acting as a direct strain pickup; and

- MS: an FBG integrated into a mechanical transducer composed of a base-fiber-mass assembly designed to amplify local strain and enhance detection sensitivity.

2.2. Computational Tools and Numerical Implementation

2.3. Design Principles of the Mchanical Sensor

2.4. Meshing Strategy

2.5. Material Behavior and Strength Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Modal Deformation Analysis of the Pipe

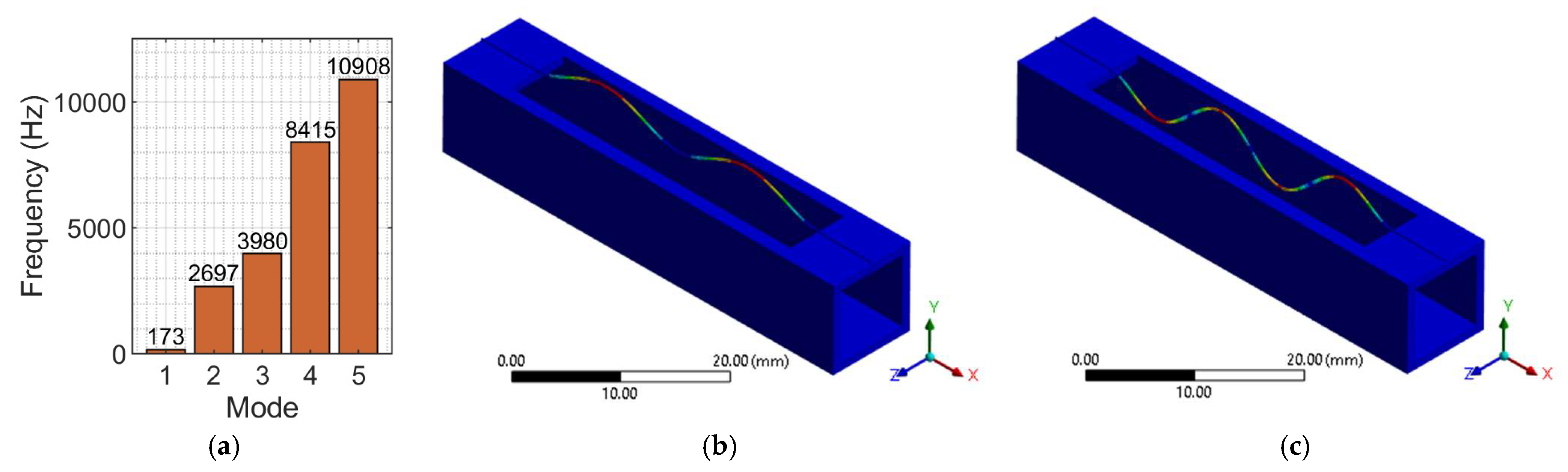

3.2. Design of Experiments (DOE) for MS Tuning

3.3. Harmonic Response Analysis

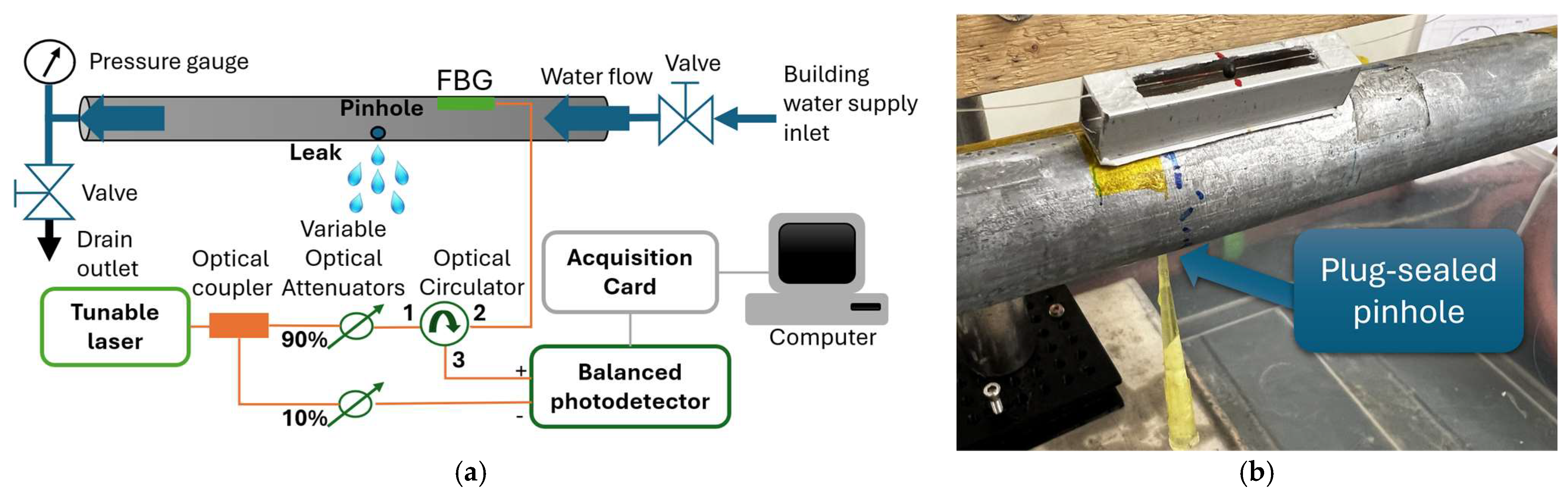

4. Experimental Validation

5. Discussion

- Resonance-based, frequency-selective amplification;

- Modal alignment with leak-excited modes;

- Non-intrusive and reconfigurable installation;

- Strong numerical–experimental agreement;

- Superior detection of high-frequency leak signatures that remain weak or masked when using directly bonded FBGs.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Scope and Limitations

6.2. Generalization and Implications

6.3. Practical Outcome

7. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C | Damping matrix (Rayleigh-type) |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| D | Diameter of the proof mass |

| DOE | Design of experiments |

| DS | Direct sensor (directly bonded FBG) |

| FBG | Fiber bragg grating |

| F(ω) | Equivalent load derived from leak-induced pressure perturbation |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| FEA | Finite element analysis |

| K | Global stiffness matrix |

| L | Free fiber length |

| M | Global mass matrix |

| MS | Mechanical sensor (base–fiber–mass transducer) |

| ϕ | Mode shape vector |

| u(ω) | Steady-state displacement field |

| ω | Natural circular frequency |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Keramat, A.; Duan, H.-F. Formulation and analysis of transient flows in fluid pipelines with distributed leakage. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 212, 111294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Luo, R. Numerical analysis of incompressible flow leakage in short pipes. In Proceedings of the Pipeline Technology Conference 2017, Berlin, Germany, 2−4 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Luo, R. Numerical Analysis on Pipeline Leakage Characteristics for Incompressible Flow. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2019, 12, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.M.C.; Soares, A.K.; Ramos, H.M.; Covas, D.I.C. CFD modeling of transient flow in pressurized pipes. Comput. Fluids 2016, 126, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, O.Y.; Masuri, S.U. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis on Single Leak and Double Leaks Subsea Pipeline Leakage. CFD Lett. 2019, 11, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, N.M.; Carriço, N.J.; Ramos, H.M.; Covas, D.I. Velocity-distribution in pressurized pipe flow using CFD: Accuracy and mesh analysis. Comput. Fluids 2014, 105, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, H.; Karkulali, P.; Ukil, A.; Dauwels, J. Testbed for real-time monitoring of leak in low-pressure gas pipeline. In Proceedings of the IECON 2016—42nd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Florence, Italy, 23−26 October 2016; pp. 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, A.B.; Nasir, A.; Ayo, S.A.; Ige, B. Hydraulic Transient Analysis in Fluid Pipeline: A Review. J. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 7, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Okosun, F.; Cahill, P.; Hazra, B.; Pakrashi, V. Vibration-based leak detection and monitoring of water pipes using output-only piezoelectric sensors. Eur. Phys. J. Spéc. Top. 2019, 228, 1659–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okosun, F.; Celikin, M.; Pakrashi, V. A Numerical Model for Experimental Designs of Vibration-Based Leak Detection and Monitoring of Water Pipes Using Piezoelectric Patches. Sensors 2020, 20, 6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaev, A.G.; Fuming, Z. A Leak Detection Method for Underground Polyethylene Gas Pipelines Using Simulation Software Ansys Fluent. Int. J. Eng. 2024, 37, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, G.; Liu, H.; Meng, Q.; Li, Y. Deformation Analysis of Crude Oil Pipeline Caused by Pipe Corrosion and Leakage. In Advances in Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing, Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on IIH-MSP in Conjunction with the 12th International Conference on FITAT, Jilin, China, 18–20 July 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 157, pp. 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, C.A.; Romero, O.J. Influence of oil leakage in the pressure and flow rate behaviors in pipeline. Lat. Am. J. Energy Res. 2017, 4, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraiuolo, R.; De Paola, F.; Fiorillo, D.; Caroppi, G.; Pugliese, F. Experimental and Numerical Assessment of Water Leakages in a PVC-A Pipe. Water 2020, 12, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wang, S.; Ling, K. Detection of two-point leakages in a pipeline based on lab investigation and numerical simulation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K.; Singh, S.; Rokade, M.; Singh, S. Experimental and computational fluid dynamic (CFD) simulation of leak shapes and sizes for gas pipeline. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2023, 84, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchôa, J.G.S.M.; Yu, T.; Yu, S.; Neto, I.E.L. Computational Simulation of the Flow Induced by Water Leaks in Pipes. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2023, 149, 05023004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lv, M.; Dong, S.; Li, H.; Lu, C. Research on Simulation and Dynamic Pressure Prediction of Pipeline Transient Conditions Based on Fluent and Deep Learning. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 618, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, R.; Khoo, B.C. Numerical and experimental study on the generation and propagation of negative wave in high-pressure gas pipeline leakage. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2020, 65, 104129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, X.; Neto, I.E.L.; Zhang, T.; Shao, Y.; Ye, M. Impact of Orifice-to-Pipe Diameter Ratio on Leakage Flow: An Experimental Study. Water 2019, 11, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.F.; Lee, P.; Karney, B.W. A selective literature review of transient-based leak detection methods. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2009, 2, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puust, R.; Kapelan, Z.; Savic, D.A.; Koppel, T. A review of methods for leakage management in pipe networks. Urban Water J. 2010, 7, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Ren, L.; Jia, Z.; Li, D.; Li, H. Application of FBG Based Sensor in Pipeline Safety Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Lee, A.; Park, S.W.; Yeo, C.; Bae, C.; Park, H.J. Experimental Study on Leak-induced Vibration in WaterPipelines Using Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors. Curr. Opt. Photonics 2022, 6, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altabey, W.A.; Wu, Z.; Noori, M.; Fathnejat, H. Structural Health Monitoring of Composite Pipelines Utilizing Fiber Optic Sensors and an AI-Based Algorithm—A Comprehensive Numerical Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.-W.; Pei, H.-F.; Yin, J.-H.; Lu, X.-C.; Teng, J. Monitoring and analysis of PHC pipe piles under hydraulic jacking using FBG sensing technology. Measurement 2014, 49, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Ji, C.; Pham, D.T. Strain Modal Analysis of Small and Light Pipes Using Distributed Fibre Bragg Grating Sensors. Sensors 2016, 16, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Chen, G.; Xu, C.; Xu, W. Design and experimental study of a sensitization structure with fiber grating sensor for nonintrusive pipeline pressure detection. ISA Trans. 2020, 101, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, L.; Jia, Z.; Jiang, T.; Wang, G.-X. A novel pipeline leak detection and localization method based on the FBG pipe-fixture sensor array and compressed sensing theory. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Lu, S.; Zhang, H.; Shu, Q.; Xiao, W. An FBG-based high-sensitivity structure and its application in non-intrusive detection of pipeline. Measurement 2022, 199, 111498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budinski, V.; Njegovec, M.; Pevec, S.; Macuh, B.; Donlagic, D. High-Order Fiber Bragg Grating Corrosion Sensor Based on the Detection of a Local Surface Expansion. Struct. Control. Heal. Monit. 2023, 14, 9972511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, L.; Jia, Z.; Jiang, T.; Wang, G.-X. Pipeline leak detection and corrosion monitoring based on a novel FBG pipe-fixture sensor. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 21, 1819–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Ren, L.; Li, H.; Wu, W.; Jiang, T. Performance Study of FBG Hoop Strain Sensor for Pipeline Leak Detection and Localization. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 31, 04018050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wei, Q. A Fiber Bragg Grating Pressure Sensor and Its Application to Pipeline Leakage Detection. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2013, 5, 590451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, S.; Luo, R.; Tang, J.; Zhang, C. UWFBG Array Vibration Sensing Technology for Gas Pipeline Leakage Detection and Location. Opt. Commun. 2024, 560, 130414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, F.; Quinci, G.; Nardin, C.; Vezzari, V.; Marino, A.; Ciucci, M. Bolted flange joints equipped with FBG sensors in industrial piping systems subjected to seismic loads. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 72, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, T.; Xiang, H. Leakage detection of water pipelines based on active thermometry and FBG based quasi-distributed fiber optic temperature sensing. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2021, 32, 1744–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Fu, B.; Hou, X.; Gan, W.; Huang, C. FBG strain sensing technology-based gas pipeline leak monitoring and accurate location. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y.; Shao, Y.; Sun, C. Application of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Technology to Leak Detection and Monitoring in Diaphragm Wall Joints: A Field Study. Sensors 2021, 21, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Okabe, Y. High-sensitivity ultrasonic phase-shifted fiber Bragg grating balanced sensing system. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 28353–28362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, Q. Pasted-type distributed two-dimensional fiber Bragg grating vibration sensor. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 86, 075009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Z. A Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Based Triaxial Vibration Sensor. Sensors 2015, 15, 24214–24229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrigal, J.; Ruiz, V.J.; Defez, B.; Gosálbez, J.; Sales, S. Pipeline leaks acoustic detection using mechanically amplified fiber Bragg grating sensors and artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Porto, Portugal, 25–30 May 2025; p. 136397A. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.D.; Chiang, C.C.; Nguyen, C.N.; Hsu, H.C. Design and optimization of medium-high frequency FBG acceleration sensor based on symmetry flexible hinge structure. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2023, 78, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Defez, B.; Madrigal, J.; Sales, S.; Gosalbez, J. Mechanical FBG-Based Sensor for Leak Detection in Pressurized Pipes: Design, Modal Tuning, and Validation. Sensors 2025, 25, 7260. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237260

Defez B, Madrigal J, Sales S, Gosalbez J. Mechanical FBG-Based Sensor for Leak Detection in Pressurized Pipes: Design, Modal Tuning, and Validation. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7260. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237260

Chicago/Turabian StyleDefez, Beatriz, Javier Madrigal, Salvador Sales, and Jorge Gosalbez. 2025. "Mechanical FBG-Based Sensor for Leak Detection in Pressurized Pipes: Design, Modal Tuning, and Validation" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7260. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237260

APA StyleDefez, B., Madrigal, J., Sales, S., & Gosalbez, J. (2025). Mechanical FBG-Based Sensor for Leak Detection in Pressurized Pipes: Design, Modal Tuning, and Validation. Sensors, 25(23), 7260. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237260