Towards User-Generalizable Wearable-Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Multi-Task Contrastive Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel multi-task supervised contrastive learning framework for user-generalizable wearable HAR. By jointly leveraging activity and user labels during training, the framework explicitly promotes user-invariant yet activity-discriminative representations, allowing the model to perform user-independent inference without any per-user calibration.

- We introduce a unified single-stage optimization strategy that integrates supervised classification and contrastive objectives into one cohesive learning process. This design avoids the objective misalignment and complexity commonly seen in two-stage pipelines, providing a simple and effective approach for improving user-level generalization.

2. Related Work

2.1. Wearable Sensor-Based HAR Model

2.2. Contrastive Learning for HAR

2.3. Personalization and User Generalization Approaches

2.3.1. Personalized Approaches

2.3.2. User Generalization

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Setup

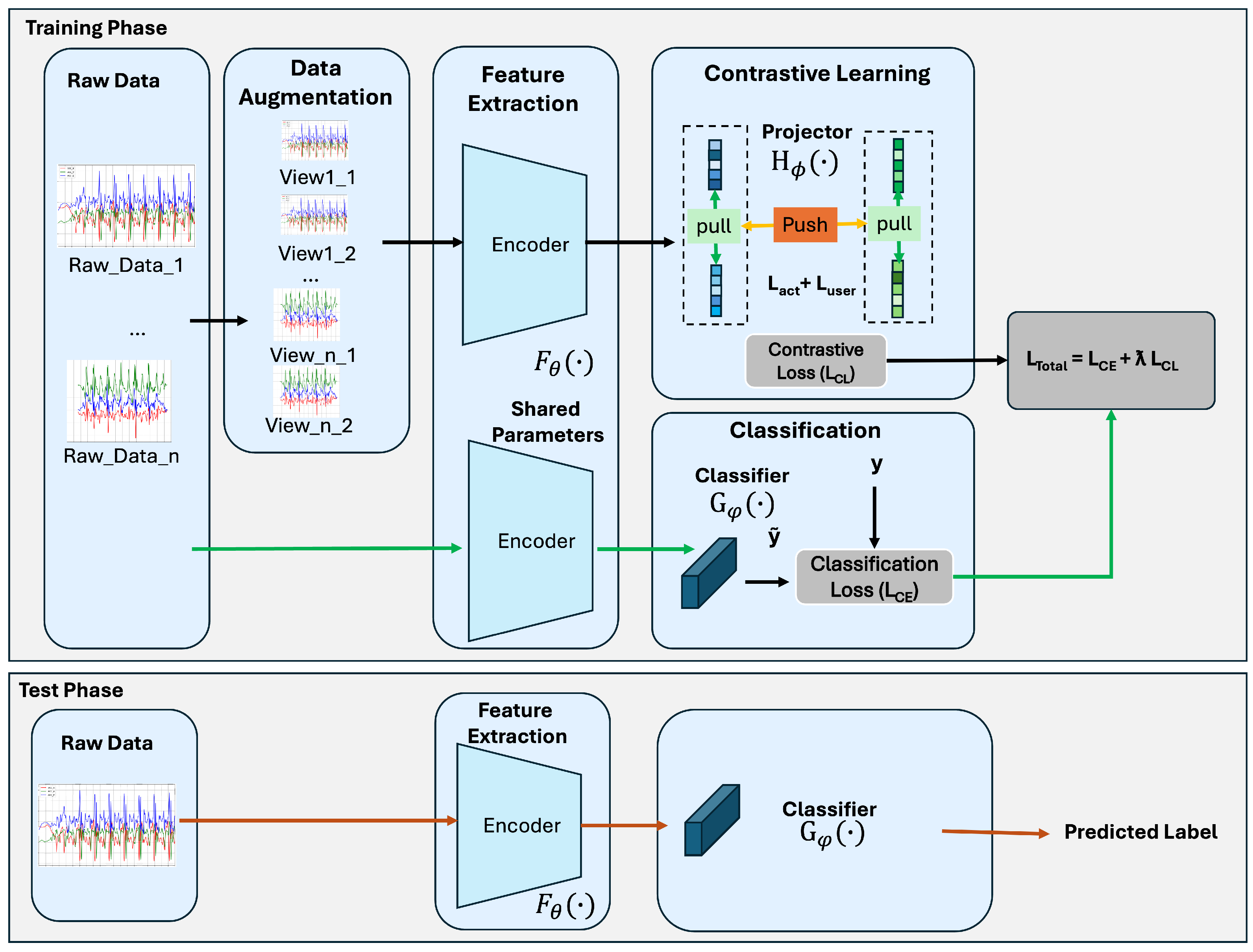

3.2. Multi-Task Contrastive Learning Framework

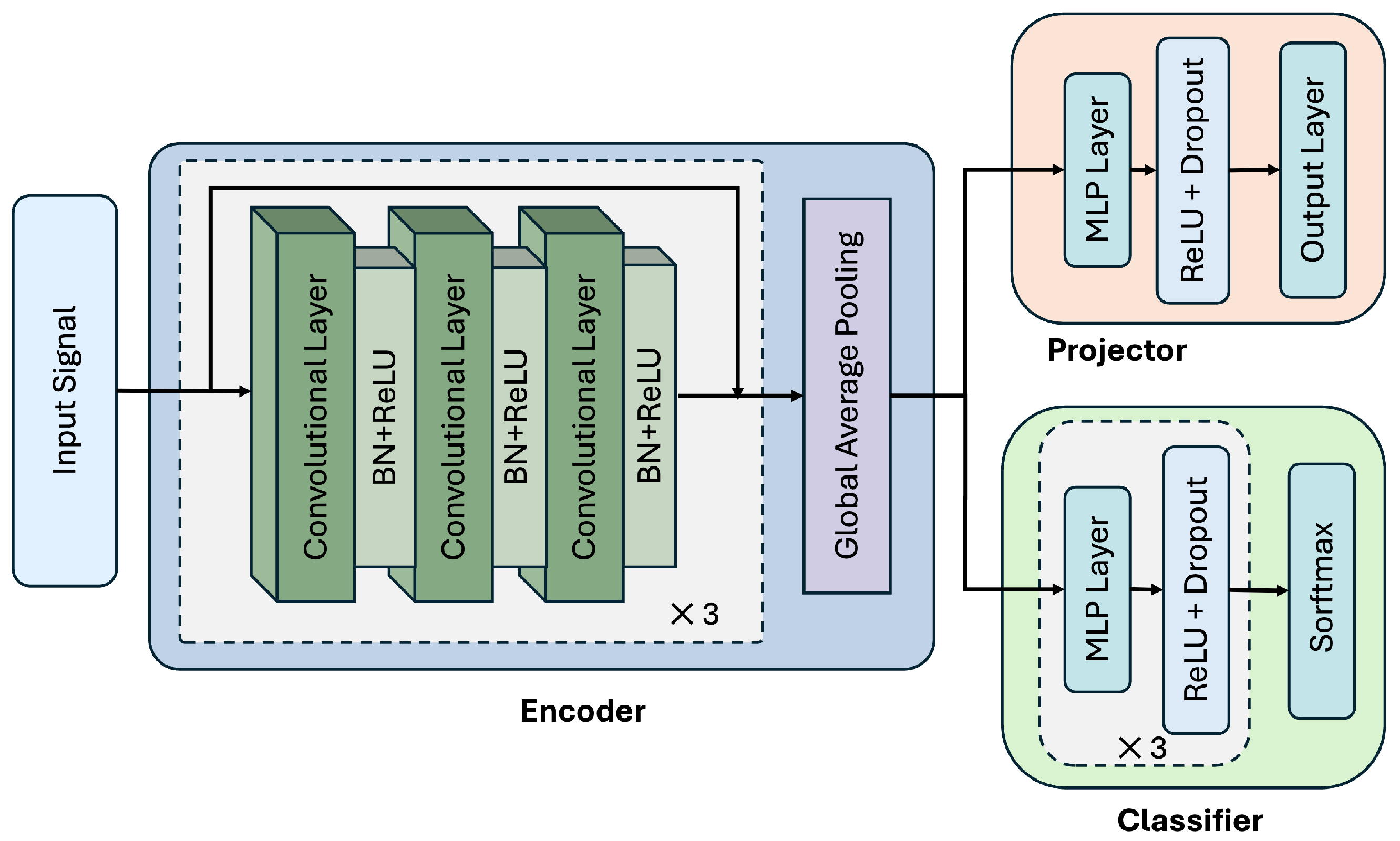

3.2.1. Model Architecture

3.2.2. Activity Classification Task

3.2.3. Contrastive Learning Task

- Jittering: Adds Gaussian noise to the signal.

- Scaling: Multiplies the signal by a random scalar drawn from a normal distribution.

- Channel Shuffle: Randomly permutes the channels of multivariate time-series data.

- Rotation: Randomly inverts the sign of the signal values.

- Permutation: Divides the signal into segments and permutes their order.

- -

- Positive pairs: samples with the same activity label across different users.

- -

- Negative pairs: samples with different activity labels but from the same user.

3.2.4. Loss and Optimization

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

4.1.1. MobiAct [39]

4.1.2. UCI HAR [40]

4.1.3. USC-HAD [41]

4.2. Implementation Details

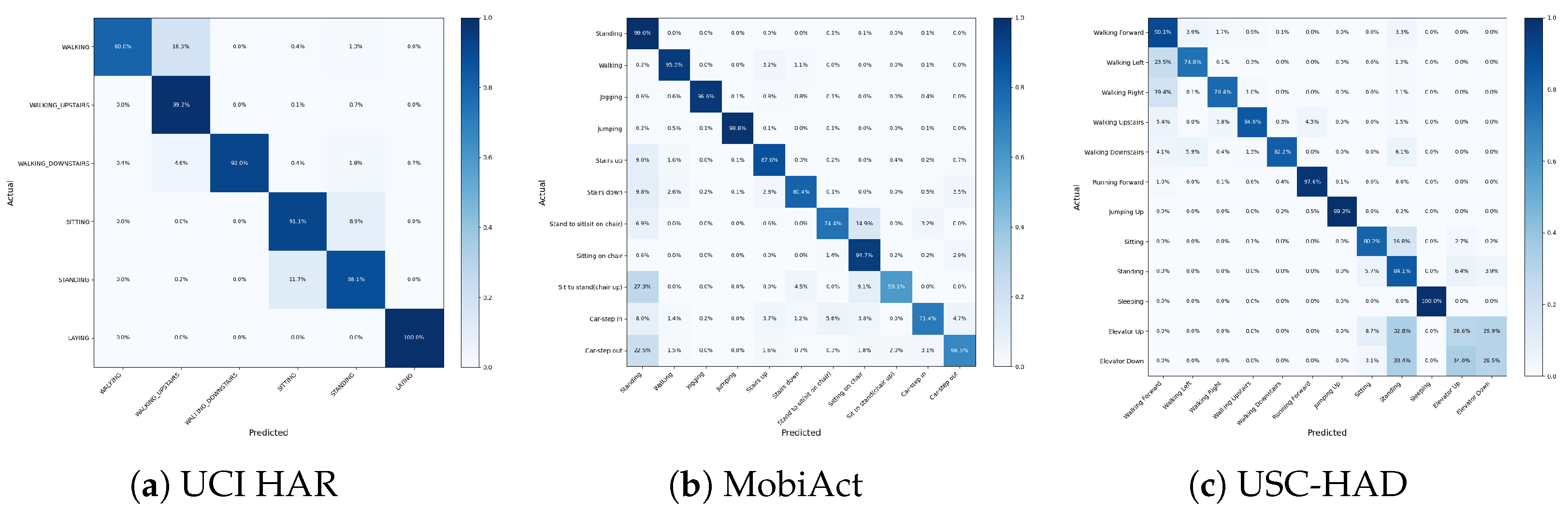

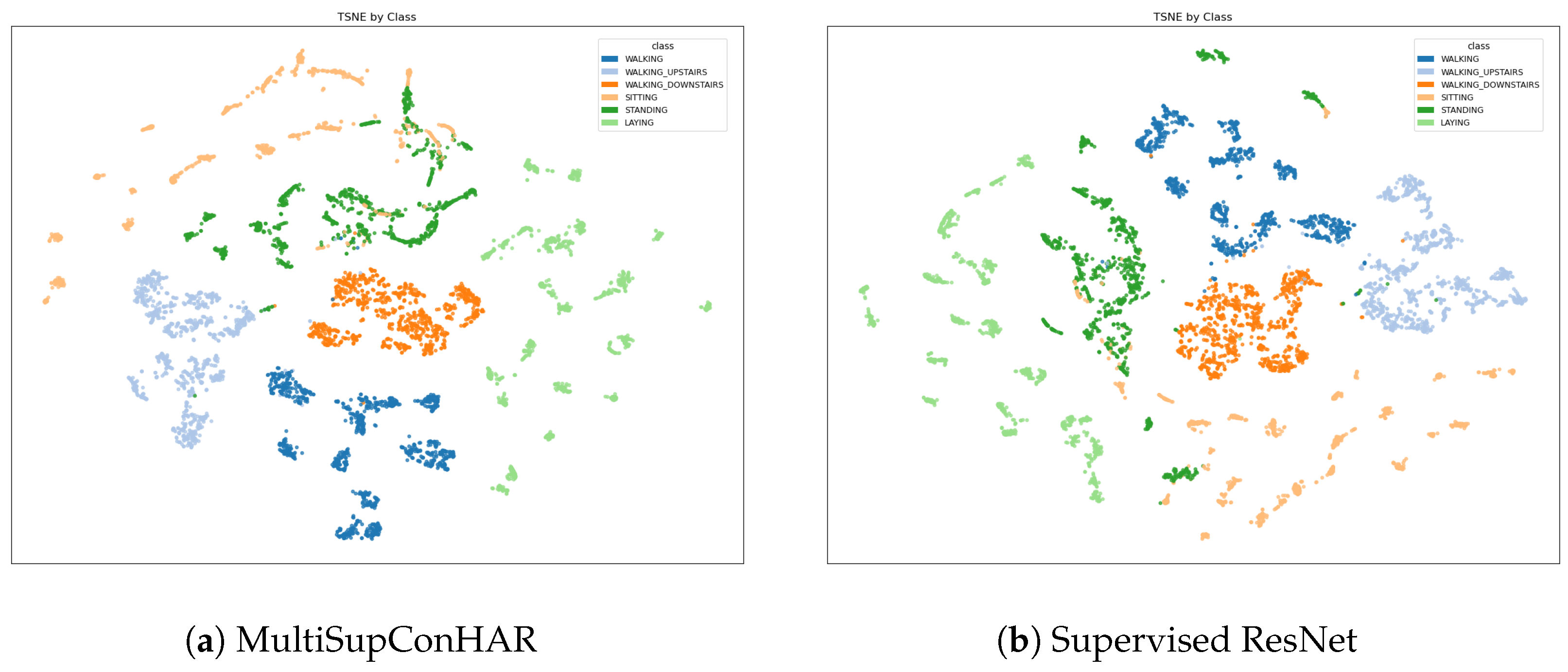

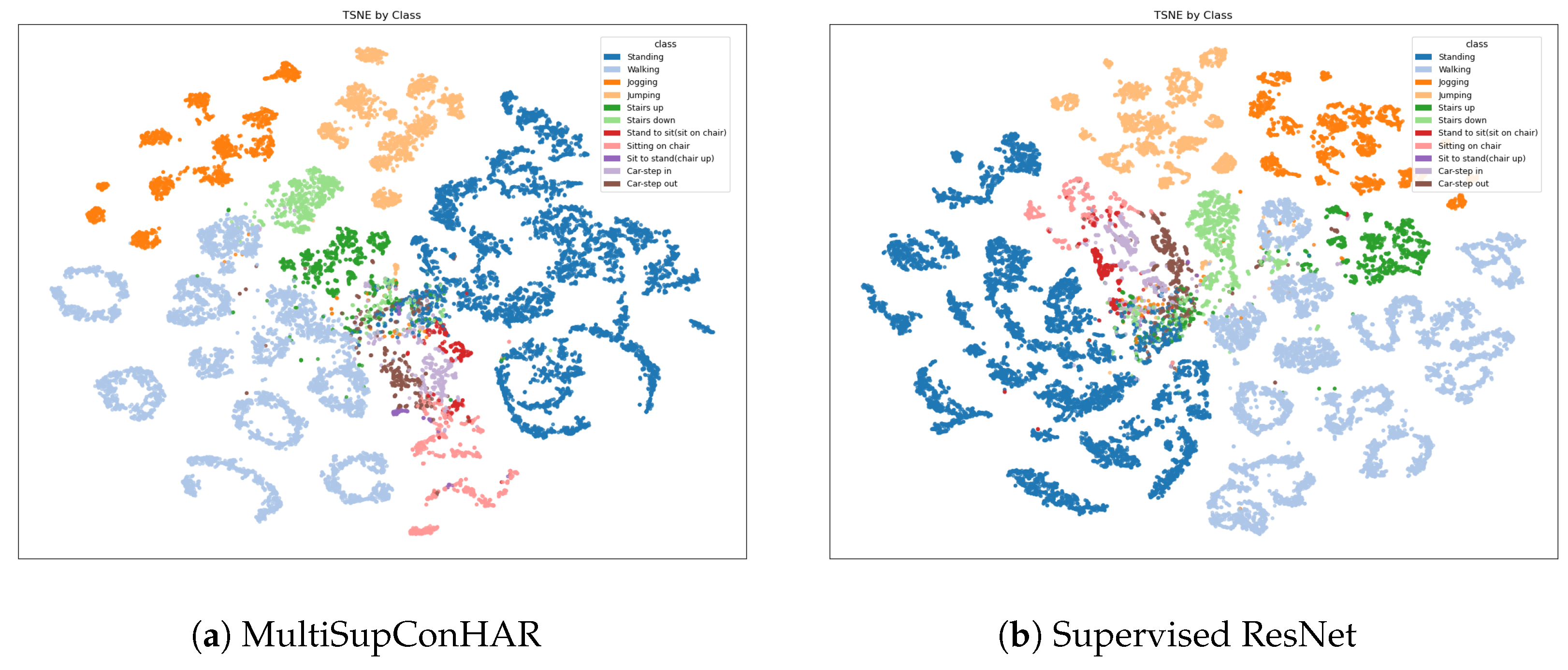

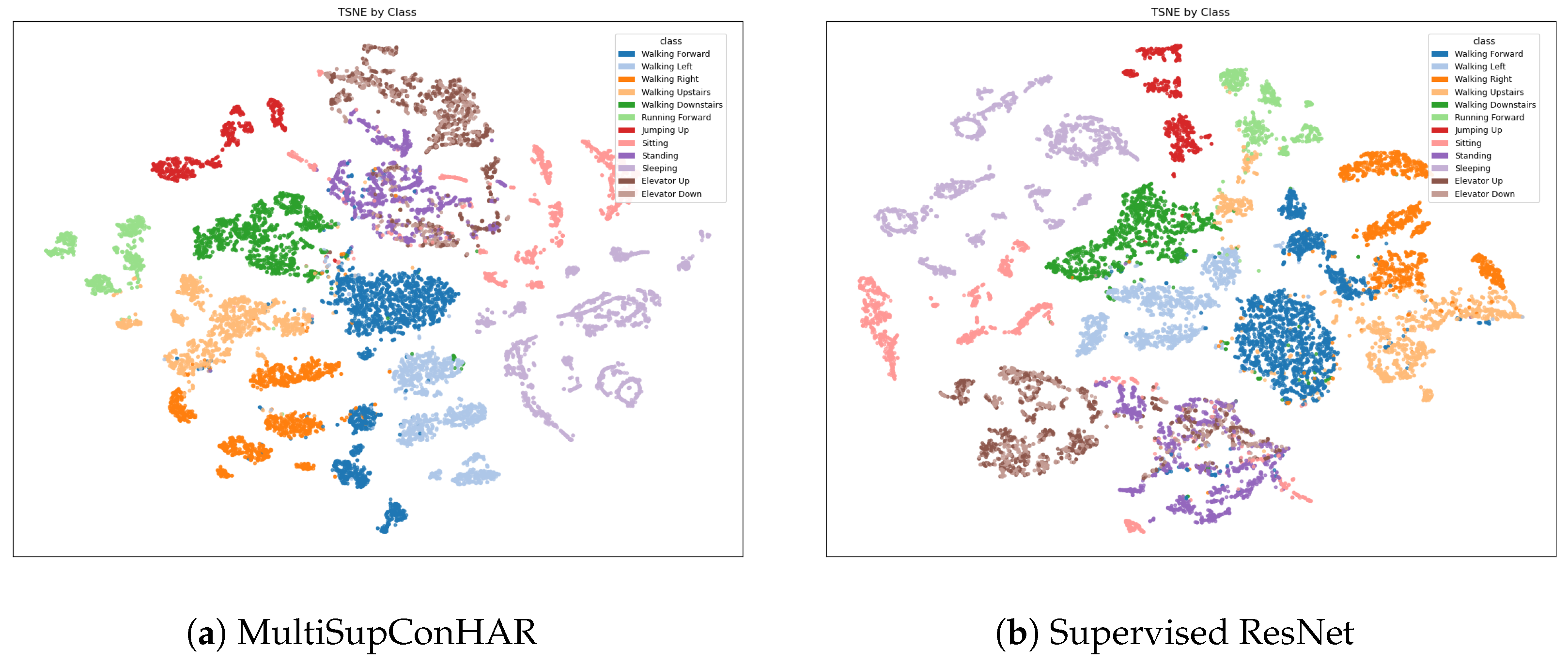

4.3. Main Results

4.4. Ablation Study

- Effectiveness of Multi-Task Training: We compare three settings—supervised classification only (primary task), supervised contrastive learning followed by downstream classification (auxiliary task only), and our joint multi-task training approach.

- Contrastive Learning Strategies: We investigate different strategies for constructing positive and negative pairs, including with/without user labels, with/without activity labels, and compare two-stage versus single-stage training schemes.

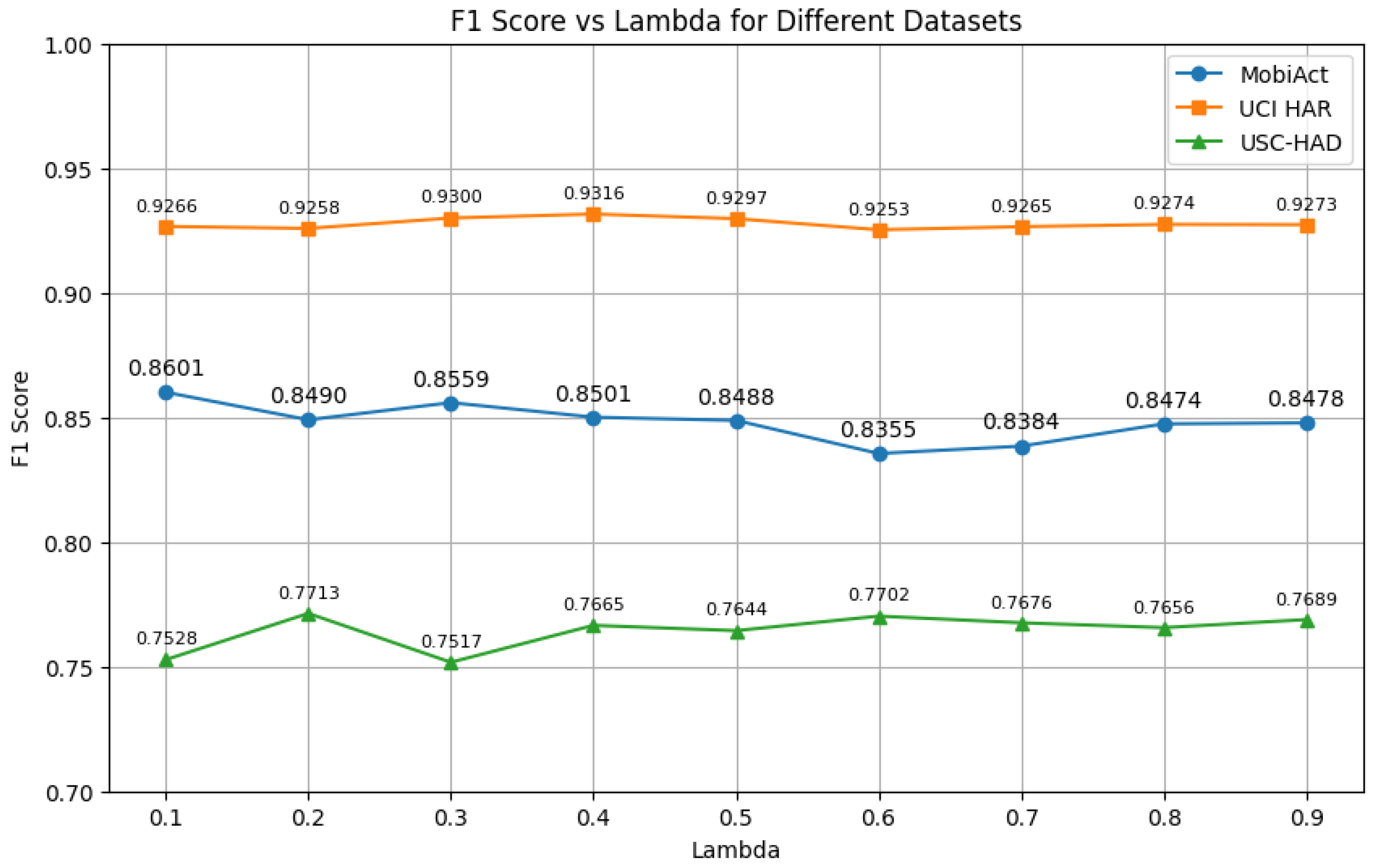

- Auxiliary Task Weight(): We vary the weight of the contrastive loss in the total loss function, testing to observe its influence on model performance.

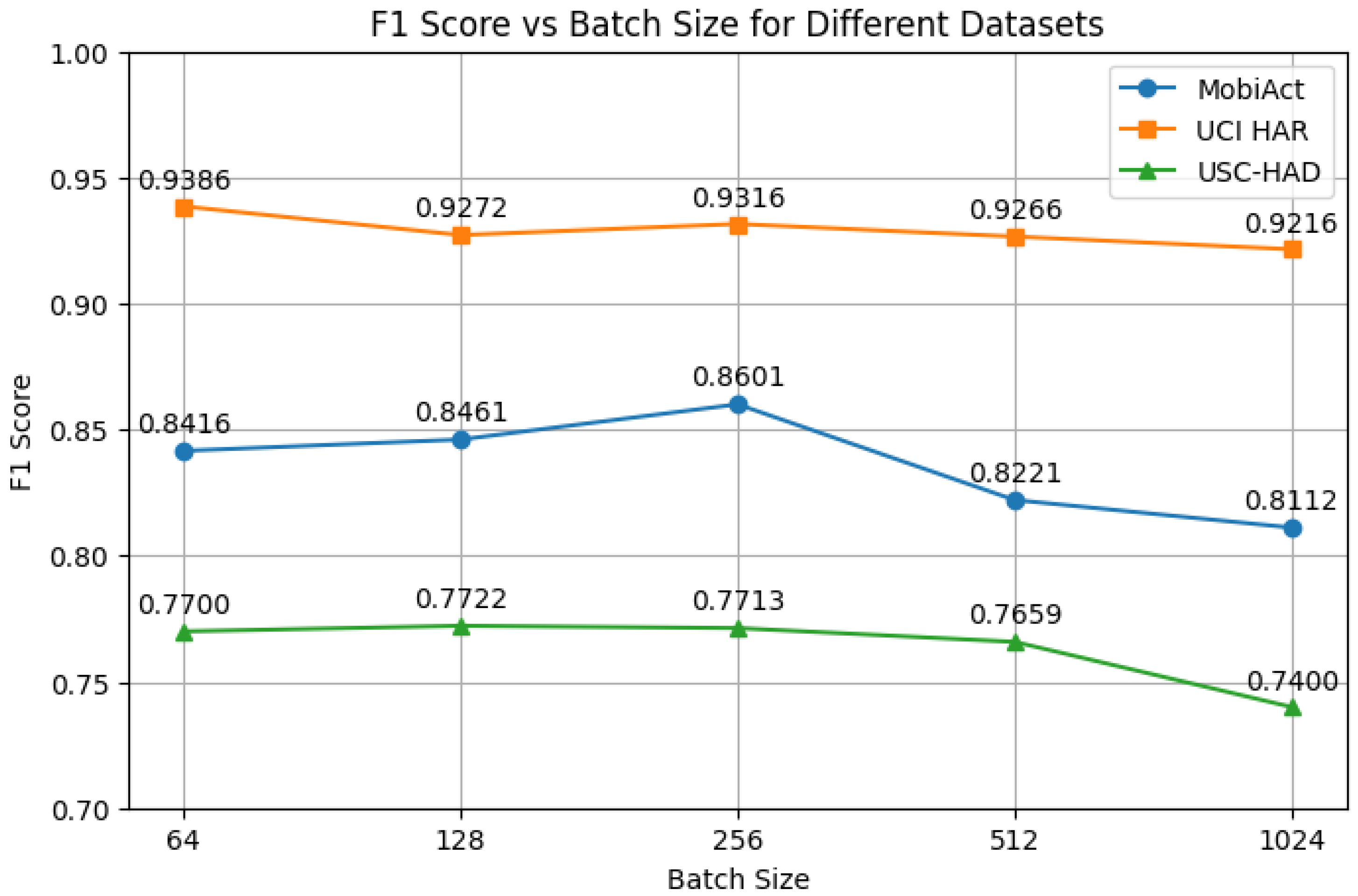

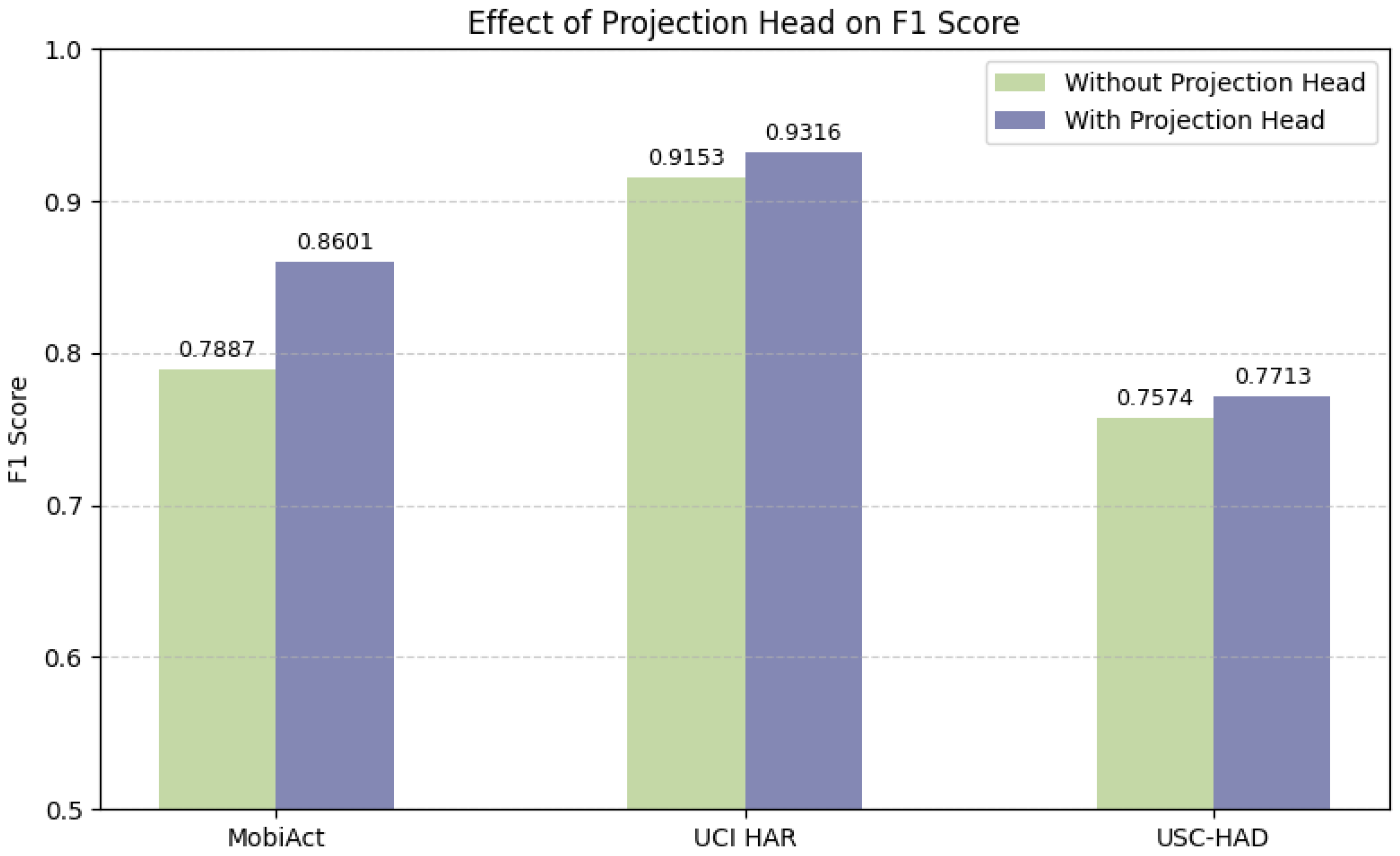

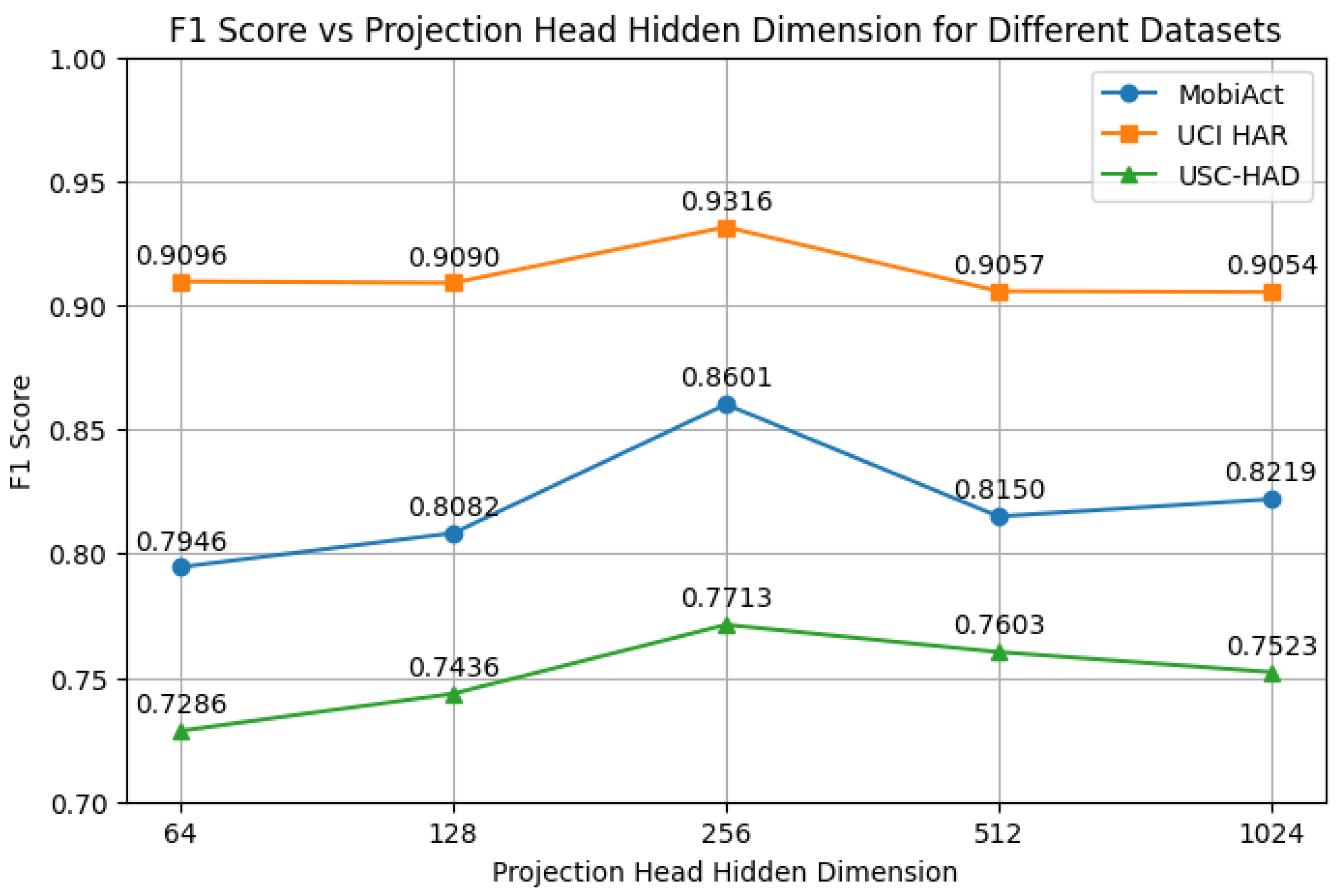

- Hyperparameter Sensitivity: We study the impact of key hyperparameters, including batch size, the presence of a projection head, and the hidden dimensionality of the projection head.

- Does joint multi-task training yield better HAR classification performance than training on individual tasks alone?

- How should positive and negative pairs be constructed? Is incorporating user identity during training beneficial?

- Is the proposed single-stage multi-task approach more effective than a two-stage contrastive pre-training followed by fine-tuning?

- How sensitive is model performance to the choice of contrastive loss weight ()?

- Are the selected hyperparameters (e.g., batch size, projection head) optimal for both performance and generalization?

4.4.1. Effectiveness of Multi-Task Training

- Supervised Classification Only (Primary Task Only): The model is trained solely with the cross-entropy loss for activity classification.

- SupCon Only (Act + User): A two-stage training approach in which the model is first trained using the supervised contrastive loss with both activity and user labels. The encoder is then frozen, and a classifier is fine-tuned on the fully labeled dataset.

- MultiSupConHAR (SupCon Act + User): Our proposed method, where the model is trained end-to-end by jointly optimizing the classification loss and the supervised contrastive loss.

4.4.2. Contrastive Strategy Analysis

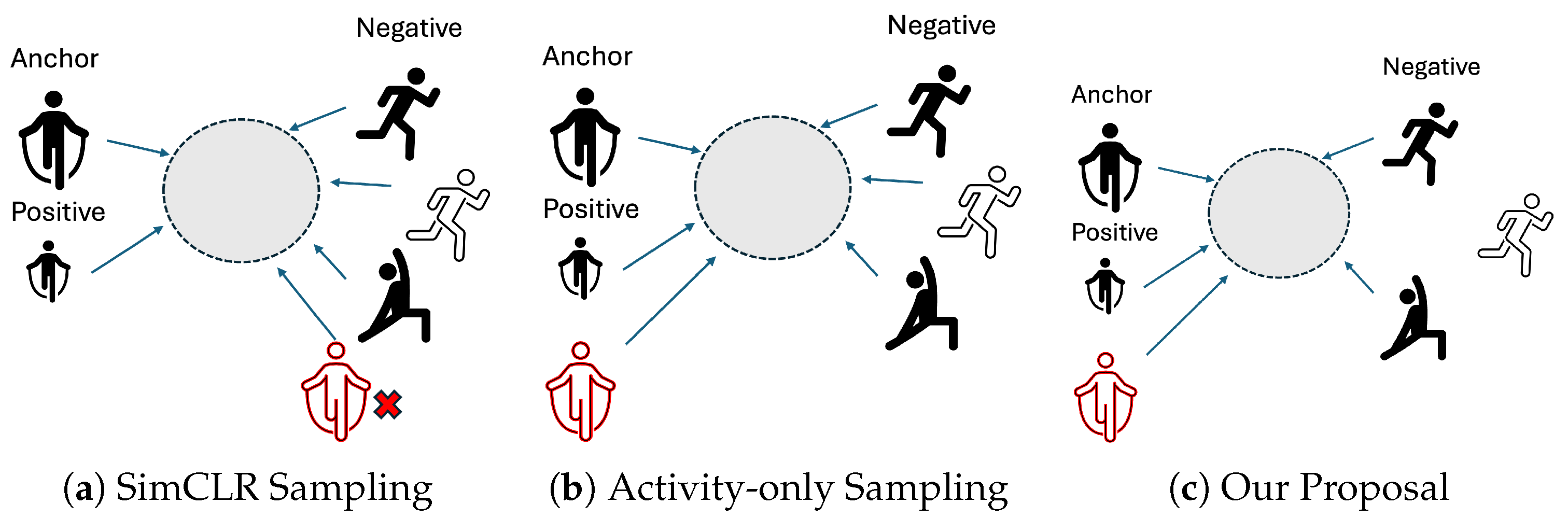

- SimCLR (Two-stage): Self-supervised contrastive learning based solely on data augmentations, without using any labels. The construction of positive and negative pairs follows Figure 3a. The encoder is then frozen, and a classifier is fine-tuned on the fully labeled dataset. The contrastive loss is computed using the XNent loss Formulation (8) [34].

- SupCon (Act Only, Two-stage): Supervised contrastive learning using only activity labels to construct positive and negative pairs (Figure 3b). The encoder is then frozen, and a classifier is fine-tuned on the fully labeled dataset.

- SupCon (Act + User, Two-stage): A stricter version of SupCon, in which both activity and user labels must match to form positive and negative pairs (Figure 3c).

- Multi-task + SupCon (Act Only): Joint training with SupCon using activity labels (Figure 3c).

- Does leveraging label information in contrastive learning improve downstream HAR performance?

- Does incorporating both user and activity identities into positive sampling help the model learn more user-invariant features?

- Do multi-task learning variants outperform their two-stage counterparts across different strategies?

4.4.3. Auxiliary Task Weight Analysis

4.4.4. Hyperparameter Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Results and Comparisons

- Self-supervised pretraining (e.g., Multi-task SSL [33]) learns transformation-aware representations through auxiliary tasks. While effective for representation learning, these methods typically rely on separate pretraining and fine-tuning stages, which limits task-level integration.

- Domain disentanglement methods (e.g., GILE [17]) aim to separate domain-invariant and domain-specific features through probabilistic modeling. These approaches enable zero-shot transfer but involve complex, sampling-based training procedures.

5.2. Ablation Study Discussion

- Supervised contrastive learning (SupCon) achieves higher performance than self-supervised contrastive learning (SimCLR), indicating that label supervision is beneficial for wearable HAR tasks.

- Multi-task variants consistently outperform their two-stage counterparts, highlighting the advantages of end-to-end joint training in balancing generalization and optimization stability.

- Interestingly, while incorporating both activity and user labels (Act + User) into the contrastive learning process improves performance in the multi-task setting, we observe limited or no improvement in the two-stage setting. This difference may arise from how the two paradigms utilize supervision signals during optimization.

- Batch Size: Consistent with prior studies [46], excessively large batch sizes can reduce gradient diversity and introduce optimization instability. We select a batch size of 256 to balance computational efficiency and model performance.

- Projection Head: The inclusion of a projection head improves performance, aligning with previous findings in contrastive learning [32]. The projection head serves as a representation bottleneck, decoupling the contrastive space from the classification space and thereby enhancing generalization.

- Hidden Dimension: Using overly small (e.g., 64) or large (e.g., 1024) hidden dimensions leads to performance degradation. This suggests that under-parameterization limits representational capacity, while over-parameterization may cause overfitting or training instability. A moderate hidden dimension (e.g., 256) provides the best trade-off.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Z.; Jin, D.; He, J.; Zhou, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, T. Digital Health Platform for Improving the Effect of the Active Health Management of Chronic Diseases in the Community: Mixed Methods Exploratory Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e50959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ke, Q.; Rahmani, H.; Bennamoun, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, J. Human Action Recognition From Various Data Modalities: A Review. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 3200–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobir, M.I.; Machado, P.; Lotfi, A.; Haider, D.; Ihianle, I.K. Enhancing Multi-User Activity Recognition in an Indoor Environment with Augmented Wi-Fi Channel State Information and Transformer Architectures. Sensors 2025, 25, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. Deep Learning Based Human Activity Recognition (HAR) Using Wearable Sensor Data. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2021, 1, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Min, F.; Song, A. Channel-Equalization-HAR: A Light-Weight Convolutional Neural Network for Wearable Sensor Based Human Activity Recognition. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 22, 5064–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y.; Huang, W.; Min, F.; He, J. Human Activity Recognition Using Wearable Sensors by Heterogeneous Convolutional Neural Networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 198, 116764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Gao, W.; Min, F.; He, J. Shallow Convolutional Neural Networks for Human Activity Recognition Using Wearable Sensors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 2510811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Min, F.; He, J. Multiscale Deep Feature Learning for Human Activity Recognition Using Wearable Sensors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.R.; Kapila, R.; Panse, A.; Zhang, X.; Teng, D.; Kulkarni, R.; Hong, D.; Gupta, R.K.; Shang, J. ZeroHAR: Sensor Context Augments Zero-Shot Wearable Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–7 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 16046–16054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.; Han, C. Generalizable Sensor-Based Activity Recognition via Categorical Concept Invariant Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–7 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhong, S.; Lyu, W.; Wang, H.; Ding, Y.; He, T.; Zhang, D. CrossHAR: Generalizing Cross-Dataset Human Activity Recognition via Hierarchical Self-Supervised Pretraining. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2024, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, V.; Bassoli, M.; Lombardo, G.; Fornacciari, P.; Mordonini, M.; De Munari, I. IoT Wearable Sensor and Deep Learning: An Integrated Approach for Personalized Human Activity Recognition in a Smart Home Environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8553–8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Samanta, R.; Roy, R.B.; Chakraborty, C.; Ghosh, S.K. Personalized Human Activity Recognition: Real-Time On-Device Training and Inference. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2025, 14, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Moosmann, J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, B.; Magno, M.; Lukowicz, P.; Bian, S. Bridging Generalization and Personalization in Wearable Human Activity Recognition via On-Device Few-Shot Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.15413. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.15413 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Fu, Z.; He, X.; Wang, E.; Huo, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, D. Personalized Human Activity Recognition Based on Integrated Wearable Sensor and Transfer Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Song, A. FedHAR: Semi-Supervised Online Learning for Personalized Federated Human Activity Recognition. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 22, 3318–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Pan, S.J.; Miao, C. Latent Independent Excitation for Generalizable Sensor-Based Cross-Person Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 11921–11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, W.; Jiang, X. Domain Generalization for Activity Recognition via Adaptive Feature Fusion. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2023, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hoey, J.; Nugent, C.D.; Cook, D.J.; Yu, Z. Sensor-Based Activity Recognition. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. C Appl. Rev. 2012, 42, 790–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Intille, S.S. Activity Recognition from User-Annotated Acceleration Data. In Pervasive Computing; Ferscha, A., Mattern, F., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3001, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, N.; Dandekar, N.; Mysore, P.; Littman, M. Activity Recognition from Accelerometer Data. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 9–13 July 2005; pp. 1541–1546. [Google Scholar]

- Kwapisz, J.R.; Weiss, G.M.; Moore, S.A. Activity Recognition Using Cell Phone Accelerometers. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2010, 12, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.M.; Timko, J.L.; Gallagher, C.M.; Yoneda, K.; Schreiber, A.J. Smartwatch-Based Activity Recognition: A Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 February 2016; pp. 426–429. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.M.; Gumaei, A.; Aloi, G.; Fortino, G.; Zhou, M. A Smartphone-Enabled Fall Detection Framework for Elderly People in Connected Home Healthcare. IEEE Netw. 2019, 33, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, S. Improving Human Activity Recognition Performance by Data Fusion and Feature Engineering. Sensors 2021, 21, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Nakayama, M. Transformer-Based Human Activity Recognition Using Wearable Sensors for Health Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Applications (ICBEA), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 February–2 March 2025; pp. 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Nakayama, M. CNN-Transformer-Bi-LSTM: A Hybrid Deep Learning Framework for Wearable Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning (SPML), Hohhot, China, 15–17 July 2025; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Haresamudram, H.; Anderson, D.V.; Plötz, T. On the Role of Features in Human Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (ISWC), London, UK, 9–13 September 2019; pp. 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, F.J.; Roggen, D. Deep Convolutional and LSTM Recurrent Neural Networks for Multimodal Wearable Activity Recognition. Sensors 2016, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haresamudram, H.; Essa, I.; Plötz, T. Contrastive Predictive Coding for Human Activity Recognition. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2021, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; Volume 119, pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.I.; Perez-Pozuelo, I.; Spathis, D.; Mascolo, C. Exploring Contrastive Learning in Human Activity Recognition for Healthcare. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.11542. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.11542 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Saeed, A.; Ozcelebi, T.; Lukkien, J. Multi-Task Self-Supervised Learning for Human Activity Detection. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2019, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaertdinov, B.; Ghaleb, E.; Asteriadis, S. Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning for Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Biometrics (IJCB), Shenzhen, China, 4–7 August 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, T.; Chen, L.L.; Ning, H.; Wan, Y. Negative Selection by Clustering for Contrastive Learning in Human Activity Recognition. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 10833–10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Sarna, A.; Tian, Y.; Isola, P.; Maschinot, A.; Liu, C.; Krishnan, D. Supervised Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 18661–18673. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R. Multitask Learning. Mach. Learn. 1997, 28, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, W.; Oates, T. Time Series Classification from Scratch with Deep Neural Networks: A Strong Baseline. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 14–19 May 2017; pp. 1578–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzaki, C.; Pediaditis, M.; Vavoulas, G.; Tsiknakis, M. Human Daily Activity and Fall Recognition Using a Smartphone’s Acceleration Sensor. In Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 736, pp. 100–118. [Google Scholar]

- Anguita, D.; Ghio, A.; Oneto, L.; Parra, X.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.L. A Public Domain Dataset for Human Activity Recognition Using Smartphones. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks (ESANN), Bruges, Belgium, 24–26 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Sawchuk, A.A. USC-HAD: A Daily Activity Dataset for Ubiquitous Activity Recognition Using Wearable Sensors. In Proceedings of the ACM International Joint Conference on Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 5–8 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey, N.; Diethe, T.; Fafoutis, X.; Elsts, A.; McConville, R.; Flach, P.; Craddock, I. A Comprehensive Study of Activity Recognition Using Accelerometers. Informatics 2018, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Bu, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Song, A. ProtoHAR: Prototype Guided Personalized Federated Learning for Human Activity Recognition. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 3900–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, M.; Wang, H. Temporal Contrastive Learning for Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Self-Supervised Approach. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Tian, T.; Miao, C. What Makes Good Contrastive Learning on Small-Scale Wearable-Based Tasks? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.05998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Tao, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, P.; Deng, Y. Enhanced Multiview Attention Network with Random Interpolation Resize for Few-Shot Surface Defect Detection. Multimed. Syst. 2025, 31, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tao, H.; Zhou, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, P. A Content-Style Control Network with Style Contrastive Learning for Underwater Image Enhancement. Multimed. Syst. 2025, 31, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apedo, Y.; Tao, H. A Weakly Supervised Pavement Crack Segmentation Based on Adversarial Learning and Transformers. Multimed. Syst. 2025, 31, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Classes | Frequency | Sensors | Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobiAct [39] | 11 | 200 Hz | A, G, O | 66 |

| UCI HAR [40] | 6 | 50 Hz | A, G | 30 |

| USC-HAD [41] | 12 | 100 Hz | A, G | 14 |

| Dataset | Projection Size | Batch Size | Epochs (ES) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobiAct | 0.0003 | 256 | 256 | 0.1 | 200 (30) | 0.2 |

| UCI HAR | 0.0003 | 256 | 256 | 0.1 | 100 (30) | 0.4 |

| USC-HAD | 0.0001 | 256 | 256 | 0.1 | 200 (30) | 0.3 |

| Type | Method | MobiAct | UCI-HAR | USC-HAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sup. | DeepConvLSTM [29] | 82.40 ± 1.82 | 82.64 ± 0.86 | 67.14 ± 2.56 |

| Sup. CSSHAR [34] | 82.97 ± 1.10 | 93.73 ± 1.02 | 59.53 ± 1.06 | |

| CTBL [27] | 78.66 ± 5.30 | 92.72 ± 1.48 | 69.11 ± 4.29 | |

| CAE [28] | 78.75 ± 1.76 | 79.82 ± 0.97 | 49.88 ± 1.87 | |

| SSL | CSSHAR [34] | 80.22 ± 1.02 | 90.51 ± 0.60 | 60.57 ± 1.92 |

| CPC [30] | 81.54 ± 1.30 | 82.08 ± 1.04 | 52.31 ± 1.95 | |

| ClusterCLHAR * [35] | - | 92.12 | 58.85 | |

| Pers. | ProtoHAR * [44] | - | - | 71.71 |

| FedHAR * [16] | - | 79.34 | - | |

| Gen. | Multi-task SSL [33] | 76.40 ± 1.59 | 82.30 ± 1.36 | 49.83 ± 3.58 |

| GILE * [17] | - | 88.17 | - | |

| CCIL * [10] | - | - | 57.5 | |

| AFFAR * [18] | - | - | 72.58 | |

| Ours | MultiSupConHAR | 85.93 ± 1.23 | 91.07 ± 2.09 | 76.84 ± 1.09 |

| Method | Metric | MobiAct | UCI HAR | USC-HAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepConvLSTM | Model size | 458.00 k | 458.00 k | 458.00 k |

| FLOPs (Inference) | 53.20 M | 53.20 M | 53.20 M | |

| Memory (Inference) | 2.35 M | 2.35 M | 2.35 M | |

| CSSHAR | Model size (parameters) | 9.30 M | 5.40 M | 6.60 M |

| FLOPs (Inference) | 823.70 M | 491.44 M | 614.75 M | |

| Memory (Inference) | 48.40 M | 26.98 M | 31.59 M | |

| MultiSupConHAR | Model size (parameters) | 565.60 k | 566.00 k | 566.40 k |

| FLOPs (Inference) | 48.50 M | 48.50 M | 48.50 M | |

| Memory (Inference) | 2.20 MB | 2.20 MB | 2.20 MB |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking | 99.48 | 80.00 | 88.68 | 950 |

| Walking upstairs | 81.28 | 99.16 | 89.33 | 950 |

| Walking Downstairs | 100.0 | 92.02 | 95.85 | 890 |

| Sitting | 86.65 | 91.06 | 88.80 | 962 |

| Standing | 88.67 | 88.09 | 88.38 | 1075 |

| Laying | 99.43 | 100.0 | 99.71 | 1045 |

| Accuracy | 91.77 | 5872 | ||

| Macro Avg | 92.58 | 91.72 | 91.79 | 5872 |

| Weighted Avg | 92.52 | 91.77 | 91.80 | 5872 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standing | 94.19 | 99.27 | 96.66 | 6445 |

| Walking | 99.38 | 88.82 | 93.80 | 5964 |

| Jogging | 95.34 | 94.00 | 94.67 | 1718 |

| Jumping | 99.77 | 99.88 | 99.83 | 1736 |

| Stairs up | 70.84 | 87.42 | 78.26 | 906 |

| Stairs down | 68.23 | 90.45 | 77.78 | 838 |

| Stand to sit | 91.18 | 72.37 | 80.69 | 257 |

| Sitting | 91.94 | 95.13 | 93.51 | 863 |

| Sit to stand | 80.00 | 70.33 | 74.85 | 91 |

| Car-step in | 80.71 | 70.10 | 75.03 | 388 |

| Car-step out | 77.41 | 60.61 | 67.99 | 424 |

| Accuracy | 94.49 | 25,116 | ||

| Macro Avg | 84.75 | 84.03 | 84.01 | 25,116 |

| Weighted Avg | 94.60 | 94.49 | 94.44 | 25,116 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking Forward | 69.90 | 89.80 | 78.64 | 2054 |

| Walking Left | 88.67 | 67.65 | 76.75 | 1354 |

| Walking Right | 90.85 | 76.57 | 83.10 | 1354 |

| Walking Upstairs | 94.51 | 83.38 | 88.60 | 1342 |

| Walking Downstairs | 96.59 | 82.26 | 88.85 | 1274 |

| Running Forward | 91.12 | 94.64 | 92.85 | 672 |

| Jumping Up | 100.0 | 98.50 | 99.24 | 666 |

| Sitting | 89.77 | 79.33 | 84.23 | 1350 |

| Standing | 50.25 | 85.60 | 63.33 | 1160 |

| Sleeping | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1960 |

| Elevator Up | 37.08 | 34.99 | 36.00 | 886 |

| Elevator Down | 47.53 | 30.68 | 37.29 | 942 |

| Accuracy | 79.13 | 14,996 | ||

| Macro Avg | 79.69 | 76.96 | 77.41 | 14,996 |

| Weighted Avg | 81.08 | 79.13 | 79.17 | 14,996 |

| Task | MobiAct | UCI HAR | US-HAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Only | 75.13 | 89.71 | 71.35 |

| SupCon (Act + User) | 82.81 | 92.22 | 67.14 |

| MultiSupConHAR | 86.01 | 93.16 | 77.13 |

| Method | MobiAct | UCI HAR | USC-HAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised | 82.81 | 92.22 | 67.14 |

| SimCLR | 72.28 | 81.35 | 56.94 |

| SupCon (Act Only) | 78.22 | 89.24 | 71.56 |

| SupCon (Act + User) | 75.13 | 89.71 | 71.35 |

| Multi-task (SimCLR) | 80.44 | 91.83 | 73.73 |

| Multi-task (SupCon Act Only) | 82.38 | 92.69 | 74.36 |

| MultiSupConHAR | 86.01 | 93.16 | 77.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, P.; Nakayama, M. Towards User-Generalizable Wearable-Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Multi-Task Contrastive Learning Approach. Sensors 2025, 25, 6988. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226988

Guo P, Nakayama M. Towards User-Generalizable Wearable-Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Multi-Task Contrastive Learning Approach. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6988. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226988

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Pengyu, and Masaya Nakayama. 2025. "Towards User-Generalizable Wearable-Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Multi-Task Contrastive Learning Approach" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6988. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226988

APA StyleGuo, P., & Nakayama, M. (2025). Towards User-Generalizable Wearable-Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Multi-Task Contrastive Learning Approach. Sensors, 25(22), 6988. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226988