1. Introduction

Ultra-wideband (UWB) technology has been applied in various ground-proximity fuzes due to its high ranging accuracy and strong anti-interference capabilities [

1,

2]. The precise ranging of the UWB fuze relies on accurate measurement of the time of flight (ToF) of echo signals. However, when detecting extended, non-uniform complex targets such as the ground, multipath propagation effects inevitably spread a single pulse into a complex echo with temporal overlap. This temporal aliasing caused by delay spread obscures the time marker of the true distance by inducing peak ambiguity and energy center shift [

3], thereby constraining the fuze’s ranging accuracy and reliability. Therefore, accurately recovering the underlying multipath structure—i.e., the channel impulse response (CIR)—that causes the delay spread, through deconvolution techniques, is crucial for enhancing the environmental awareness of the fuze and improving its operational effectiveness.

A variety of deconvolution approaches have been investigated to address this challenge. Among them, the CLEAN algorithm and its variants have been widely applied to UWB CIR measurements with sparse multipath characteristics, including in-vehicle [

4,

5], indoor and outdoor propagation [

6,

7], soil [

8], and near-ground environments [

9]. However, CLEAN still suffers from limitations in noise sensitivity and resolution [

10], motivating the development of several alternative or complementary methods. For example, Lin [

11] introduced a matching pursuit-based tap selection method to exploit the inherent sparsity of UWB channels for efficient equalization. Savelyev [

12] developed a fast frequency-domain deconvolution algorithm for high-resolution UWB radar imaging. Hanssens [

13] extended the RiMAX algorithm with an iterative maximum likelihood estimation scheme to achieve high-precision multipath parameter extraction. Rittiplang [

14] proposed a sparse deconvolution approach with arctangent regularization, effectively suppressing noise amplification and enhancing imaging stability, and Nunoo [

15] designed a sparsity-constrained LMS algorithm with iterative gradient updates for low-complexity, real-time estimation of time-varying UWB channels.

However, these deconvolution methods rely on prior knowledge of the UWB signal waveform. The true physical waveform of the source signal can undergo unknown distortion due to system non-idealities, and any prior mismatch may lead to severe distortion in the recovered results. This issue is particularly pronounced in the Equivalent Time Sampling (ETS) system employed in this study, as its time-scale transformation process further amplifies the uncertainty in the final equivalent source signal. It is this very uncertainty regarding the precise morphology of the source signal that renders supervised methods inadequate, thereby underscoring the necessity and importance of developing blind deconvolution techniques.

Blind deconvolution is a fundamentally underdetermined problem, as it seeks to recover both the source signal and the CIR from a single observation, yielding a solution space with extremely high degrees of freedom [

16]. Incorporating sparsity priors effectively constrains the solution space and mitigates the inherent ambiguity [

17]. Notably, UWB ground propagation channels inherently exhibit discrete multipath structures and sparsity, enabling near-unique recovery of the channel response even when the source signal is unknown. Therefore, sparsity-constrained blind deconvolution represents the most practical and robust approach for tackling such problems.

Sparse blind deconvolution (SBD) was originally developed for image deblurring and has since been widely extended to a variety of signal inversion problems [

18]. In ultrasonic non-destructive testing (NDT), Gao [

19] devised a two-phase algorithm featuring an initialization stage with blind gain calibration and ADMM, followed by an alternating optimization stage accelerated by PALM and MM methods, to recover severely overlapping and noisy echo signals. For ground-penetrating radar (GPR) data blind deconvolution, Jazayeri [

20] proposed an SBD method that simultaneously estimates the source signal and subsurface reflectivity using an ℓ

2-ℓ

1 optimization scheme, without relying on prior knowledge of the wavelet. In the context of seismic data deconvolution, Repetti [

21] introduced the Sparse Optimization via Optimal Thresholding (SOOT) algorithm, which integrates alternating minimization with forward-backward splitting, accelerated by a majorization-minimization (MM) framework. Within the Bayesian framework for sparse blind deconvolution, Civek [

22] developed an improved estimation method based on a Normal-Inverse-Gamma (NIG) prior, solved efficiently using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques.

However, existing single-channel SBD frameworks still face three major challenges in non-cooperative scenarios:

- (1)

High sensitivity to initialization in a highly non-convex landscape;

- (2)

Lack of effective structured priors to resolve ambiguity in super-resolution regimes;

- (3)

Poor performance and instability under low SNR conditions.

Although strategies based on multi-channel observations [

23] or known pilot signals [

24] can alleviate these issues in specific applications, they are not applicable in the single-channel scenarios considered here. Minimum entropy deconvolution (MED) methods [

25,

26] primarily target source signal recovery and are insufficient for revealing the fine-grained structure of the CIR. Recent joint optimization approaches combining sparsity priors with dictionary learning [

27] offer high modeling flexibility, but without structural guidance, they still rely on blind search in high-dimensional spaces and are prone to local minima. More advanced non-convex optimization frameworks have emerged, providing theoretical insights under specific assumptions. Li [

28] established a landmark framework with provable convergence guarantees, but its reliance on random subspace assumptions limits its applicability to channels governed by structural physics. Wang [

29] provided crucial theoretical understanding for L1-based methods, yet their core requirement of pulse separation directly contradicts the super-resolution challenge of overlapping echoes. The work of Guo and Bhandari [

30] provides an elegant continuous domain solution by constructing source wavelets, but it relies on a Prony-like approach, making it only effective for low-order sparsity and not suitable for our dense multipath channel model. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a novel single-channel SBD framework that leverages domain-specific structural priors to ensure both reliable convergence and robustness in complex, low-SNR UWB conditions.

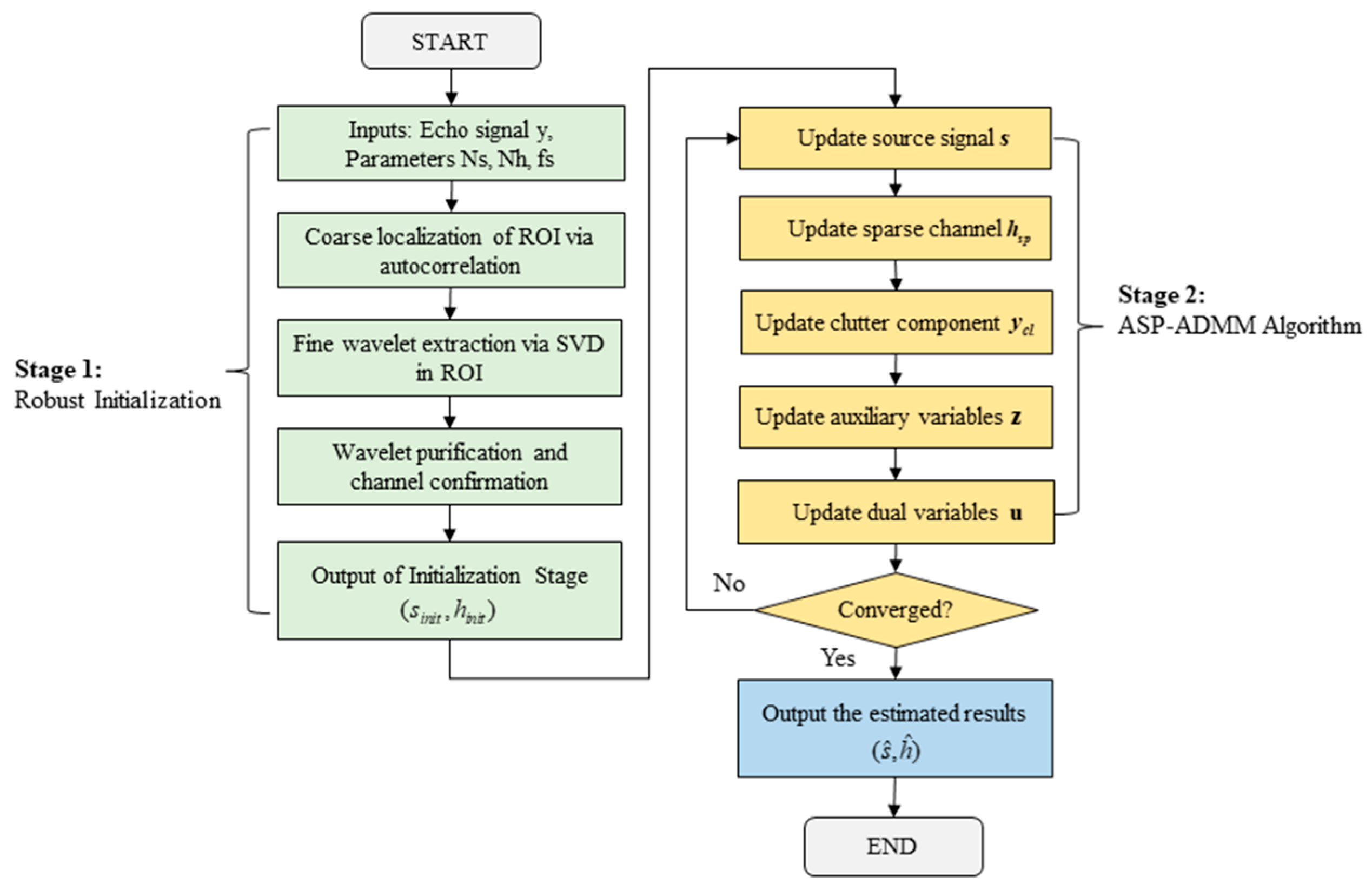

To address the aforementioned challenges of non-convexity, noise, and solution ambiguity, this paper proposes a two-stage blind deconvolution framework. First, the framework employs a data-driven strategy based on Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) for robust initialization, providing a high-quality starting point deep within the true solution’s basin of attraction for subsequent iterations. Second, within the core ADMM iterations, an innovative three-variable robust decomposition model is utilized to actively separate dispersed clutter. This model moves beyond the conventional two-variable paradigm by explicitly modeling structured echoes, non-periodic clutter, and noise, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s noise resistance. Most critically, under this purified framework, asymmetric and strongly structured priors are imposed to resolve the fundamental solution ambiguity and enable super-resolution. This prior breaks the problem’s symmetry by enforcing distinct physical constraints on the source signal the channel response : the physical morphology of is strictly constrained via parametric projections, while a periodic sparse cluster projection operator is designed to precisely model the quasi-periodic structure of . This channel-side prior is key to bypassing the coherence limitations inherent in separating severely overlapping echoes. Ultimately, this synergistic method can accurately recover the CIR characterizing ground multipath effects from a single echo, offering a novel technical pathway for UWB fuze to achieve environmental awareness and informed decision-making.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 develops an equivalent discrete multipath model (EDMM) to characterize the ground CIR for UWB fuze.

Section 3 formulates the blind deconvolution problem and introduces the initialization strategy along with the iterative optimization algorithm, incorporating the EDMM established in

Section 2 as a prior constraint.

Section 4 evaluates the performance of the proposed approach through comparative analysis against classical deconvolution methods. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential future research directions.

2. UWB Impulse Response Model

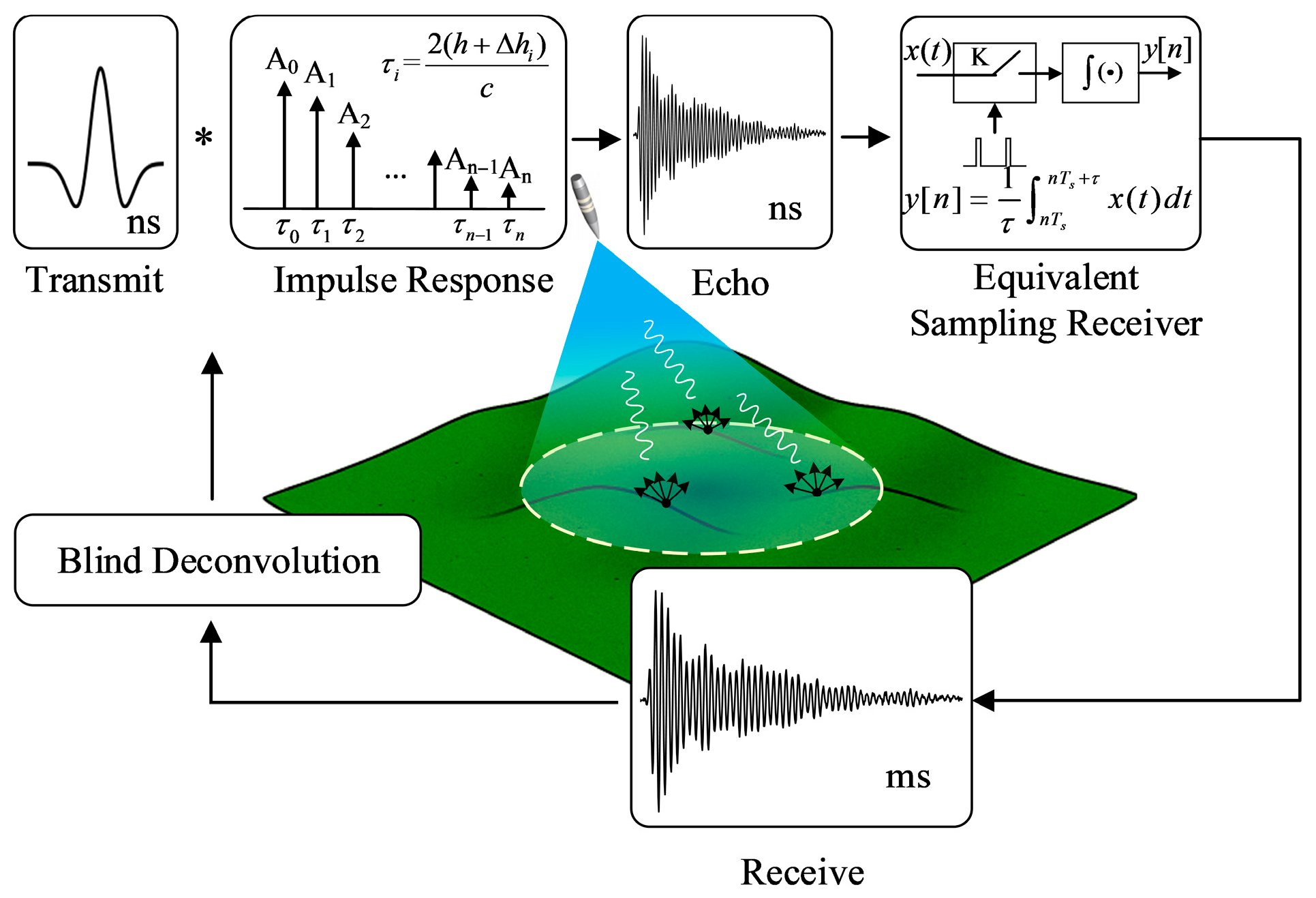

Figure 1 illustrates the core framework of this study, which performs blind deconvolution from the ground echo signal of UWB fuze. The forward physical model indicates that the equivalent source signal

, shaped by the system link and antenna transient response, is convolved with a physical channel

exhibiting delay spread due to ground multipath effects, resulting in a high-speed aliased echo

, which can be approximated by an equivalent linear time-invariant (LTI) model. This signal is then converted via ETS into the only known low- rate observed signal

. The inverse problem is solved through blind deconvolution, where the blind nature of the problem arises from the unpredictability of

caused by dynamic coupling between the antenna and the near-field environment. Thus, the goal of the algorithm is to jointly recover the equivalent source signal

and the equivalent channel

—which characterizes the ground multipath structure—using only the indirect equivalent observation

, even though both

, and

being unknown, thereby mitigating the ranging uncertainty induced by delay spread.

2.1. Ground Impulse Response Model

For typical terrain detected by UWB fuze, the surface is generally electromagnetically rough, and the most of its backscattered energy originates from incoherent diffuse reflection. This physical mechanism implies that each small rough unit illuminated by the antenna beam can be equivalently regarded as a secondary source radiating in all directions. Given that the distance between the fuze antenna and the ground is on the same order of magnitude as its illumination footprint on the ground, the wide beam angle inevitably receives backscattered echoes from ground scattering points at different distances simultaneously, resulting in geometric delay spread.

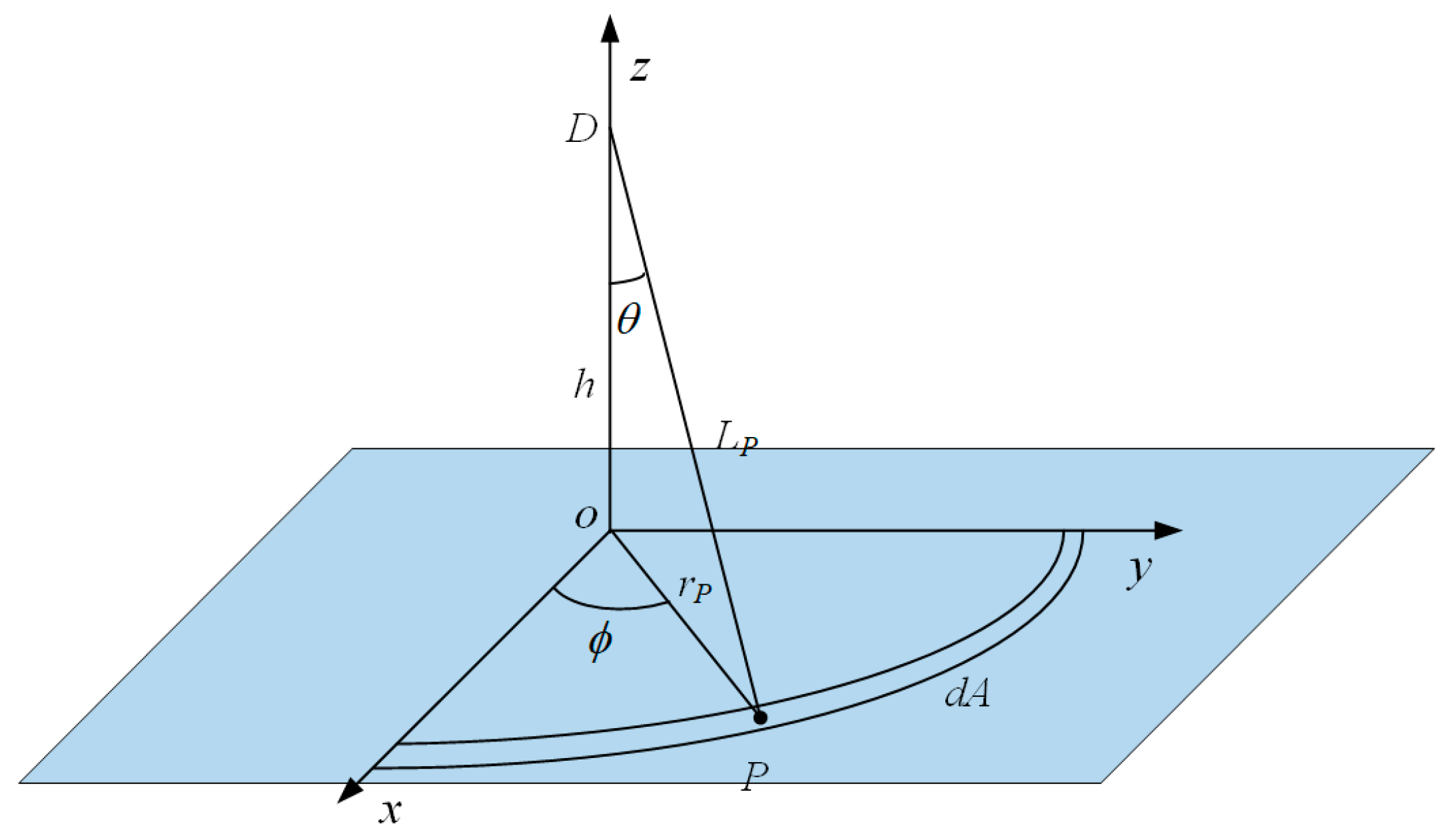

Assume that the UWB fuze is located at

, and the scattering surface is a complex ground with random undulations, whose surface height is described by the function

, where

represents the horizontal coordinates (see

Figure 2).

According to Huygens’ Principle and the radar equation, the channel response

at frequency

results from the coherent superposition of echoes from all scattering points.

where

is the complex amplitude associated with scattering point

,

denotes the differential surface area, and

is the signal round-trip time delay.

Since the ground undulation height being much smaller than the antenna height , the path length can be decomposed into an average path length and a perturbation . The corresponding time delay is , where is the horizontal distance of the ground scattering point .

By analyzing the ensemble average response of the channel and assuming that the scattering coefficient

is statistically independent of the surface undulation

, and integrating the azimuth Angle

, the result can be obtained.

where

is the average scattering amplitude,

is the coherence attenuation factor determined by the surface roughness.

Equation (2) indicates that the core phase structure of the average channel response is exactly the same as that of an ideal flat ground. Therefore, the channel can be analyzed based on the ideal delay .

Convert the integral variable from the spatial domain

to the time-delay domain

.

where c is the propagation speed of electromagnetic waves. The contour with equal time delay forms a circle, and the area

of its micro-element corresponds to the area

of the ring in the interval.

can be rewritten as

where

is the excess time delay;

is the minimum propagation delay occurring at the reflection point

, and

;

includes the rate of change in amplitude and area.

Decompose the integration interval [

of Equation (5) by period

.

where

.

Within the interval

, perform the first-order Taylor expansion on

with the midpoint

as the center and substitute it into

to obtain

The integral of the zero-order term is zero, and the integral of the first-order term is calculated as

, thus

Equation (9) indicates that the channel’s response to a single frequency is a coherent superposition of a series of contributing elements arranged in a period in the time domain.

For a UWB signal with a central frequency of

, the average structure

of its CIR can be efficiently approximated by an equivalent, time-equally spaced discrete multipath sequence

.

where

is the position of each time window.

The response intensity

of

at each moment is jointly determined by path loss, antenna directionality gain and ground scattering coefficient.

where

is a constant term incorporating system-specific factors.

is the antenna power gain function, which is dependent on the incident angle

and the azimuth angle

. Both angles are functions of the time delay

.

is the ground backscattering coefficient.

Therefore, the expression of the equivalent discrete multipath model (EDMM) is

This model thus provides a parameterized skeleton for the ground impulse response, whose key parameters are directly governed by physical properties of the radar system and the terrain. The fundamental delay interval

is dictated by the system’s center frequency, imprinting a periodic structure on the channel. The effective number of significant paths

is determined by the interplay between the antenna beamwidth and the platform altitude

, which define the size of the illuminated area and thus the maximum delay of detectable scatterers. Crucially, the amplitude

of each path, as specified in Equation (11), encapsulates the terrain-dependent physics. The ground backscattering coefficient

integrates the effects of two primary factors. The first is the complex dielectric constant, which governs the average reflection strength and its dependence on physical properties like soil moisture. The second is the surface microscopic roughness, which governs the transition from coherent to incoherent scattering and the associated random fluctuations in

. This physically grounded interpretability of the EDMM parameters justifies the adoption of a strong, structured prior in the subsequent blind deconvolution algorithm.

2.2. UWB Signal Convolution Model

UWB signals are generated by narrow pulse generation circuits and can be represented in the form of the second derivative of a Gaussian pulse [

31]. The mathematical expression is:

where

is the amplitude control coefficient of pulse signal;

is the width control coefficient of the pulse signal;

is the pulse width.

While Equation (14) provides a specific model, a more general and powerful representation for such transient, time-localized, bandpass signals is the Gabor atom. In our framework, we adopt this parametric model for the unknown source signal . This choice is justified by two fundamental reasons. Physically, a Gabor atom, being a Gaussian-windowed sinusoid, accurately captures the essential morphology of a typical UWB pulse. Mathematically, Gabor atoms are known to achieve the optimal joint time-frequency concentration dictated by the Uncertainty Principle, making them an extremely efficient and compact basis. This physically grounded parameterization constrains the unknown wavelet to a low-dimensional manifold, which is a crucial step for regularizing the ill-posed blind deconvolution problem.

Ideally, the received signal

of the UWB fuze can be modeled as a linear convolution of the unknown source signal

and the CIR

, which is interfered by noise

.

where

is the linear convolution operation.

However, in reality, the ground is a dissipative medium, and its scattering cross-section is a function of the incident angle as well as the frequency. During the scattering process of the source signal, there exists a problem of pulse shape distortion caused by the dispersion of the medium. To handle this issue reasonably within the framework of the classical LTI convolutional model, a key assumption is introduced: the waveform distortion caused by dispersion is equivalent to the superposition of several micro-multipath replicas of the original source signal wavelet.

Specifically, the pulse of the

i-th path after dispersion distortion can be approximately represented as the convolution of the undistorted equivalent source signal and the distortion operator.

where

is a compact pulse train with energy concentrated near the origin, which describes the individual filtering effect of the

i-th path.

The equivalent CIR of the final required solution is defined as

contains several sparse path clusters as well as tiny peak clusters. The internal structure of this peak cluster encodes the dispersion characteristics of each path. Despite this randomness, the overall form of the impulse-response model remains unchanged.

Substitute Equation (17) into Equation (15), and rewrite the received signal

as

Through the above derivation, we have successfully converted a complex physical process with time-varying source signals mathematically into an equivalent standard LTI convolution model.

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Simulation Data Experiment and Analysis

To quantitatively characterize the severity of temporal overlap among multipath components and thereby depict the ill-posedness of the inverse problem, this paper introduces a resolution factor. This factor compares the minimum path delay separation Δτ in the CIR with the system’s inherent delay resolution 1/BW, defining it explicitly as their ratio:

According to Equation (11), it can be concluded that

, indicating that the resolution factor is approximately equal to the relative bandwidth of the source signal.

where

and

denote the −10 dB cutoff frequencies.

When , all multipath components are resolvable in principle, and the corresponding inverse problem is relatively well-conditioned.

When , the time delay between at least two paths is less than or equal to the system’s Rayleigh resolution limit. In this scenario, classical linear methods will fail, and the problem enters the super-resolution region. A smaller value of indicates a more ill-conditioned problem, placing higher demands on the recovery algorithm’s ability to leverage prior knowledge.

Since the real source signal

and channel response

are unknown, to verify and evaluate the performance of the algorithm proposed in this paper, simulation data is constructed based on the following LTI model.

The source signal

is represented by Gabor pulses, making it easy to control different center frequencies and pulse widths. Its discrete time is defined as

where

is the sampling period and

is the effective length of the signal.

The channel response

is modeled as an ideal, equally spaced sparse pulse train.

where

is the initial delay of the first path,

is the fixed delay interval between paths, and

is the number of sparse paths.

The amplitude

of the

k-th pulse is jointly modulated by macroscopic attenuation and microscopic randomness. It can be obtained by multiplying a deterministic exponential attenuation envelope with a random lognormal fluctuation. The attenuation rate is controlled by the time constant

, and the intensity of the lognormal fluctuation is controlled by

.

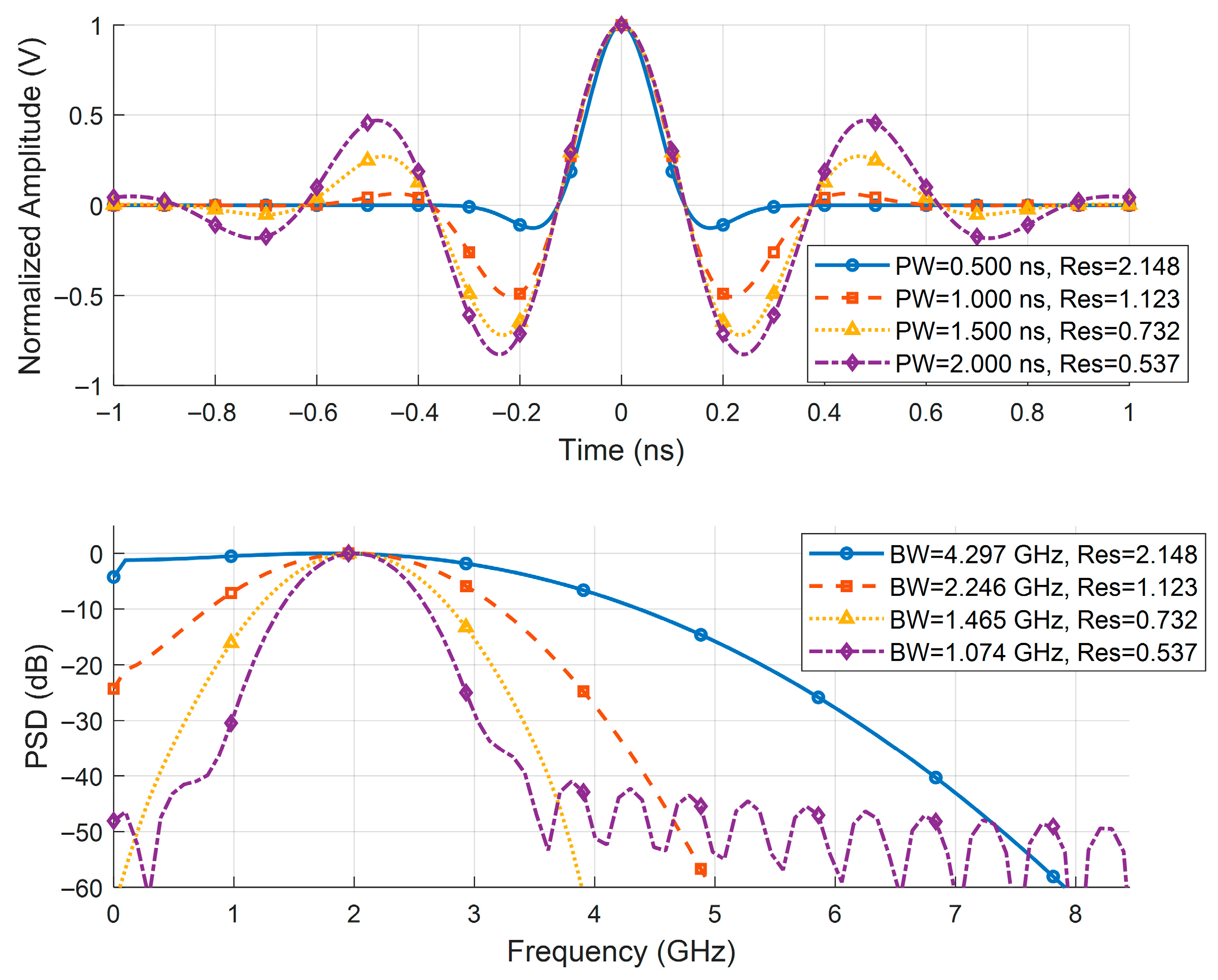

To systematically evaluate the algorithm’s performance across varying resolution factors, this study maintains the quasi-periodic structure of the channel (i.e., fixes the minimum path separation ) and achieves continuous control over by adjusting the effective bandwidth of the source signal . Specifically, based on Equation (40), the time-domain pulse width of is progressively broadened while holding its center frequency constant. Leveraging the time-bandwidth inverse proportionality principle of the Fourier transform, this operation generates a series of source waveforms with distinct system resolutions. Finally, convolving these resolution-varying source signals with a fixed CIR produces a comprehensive test dataset spanning from the resolvable region to the super-resolution region.

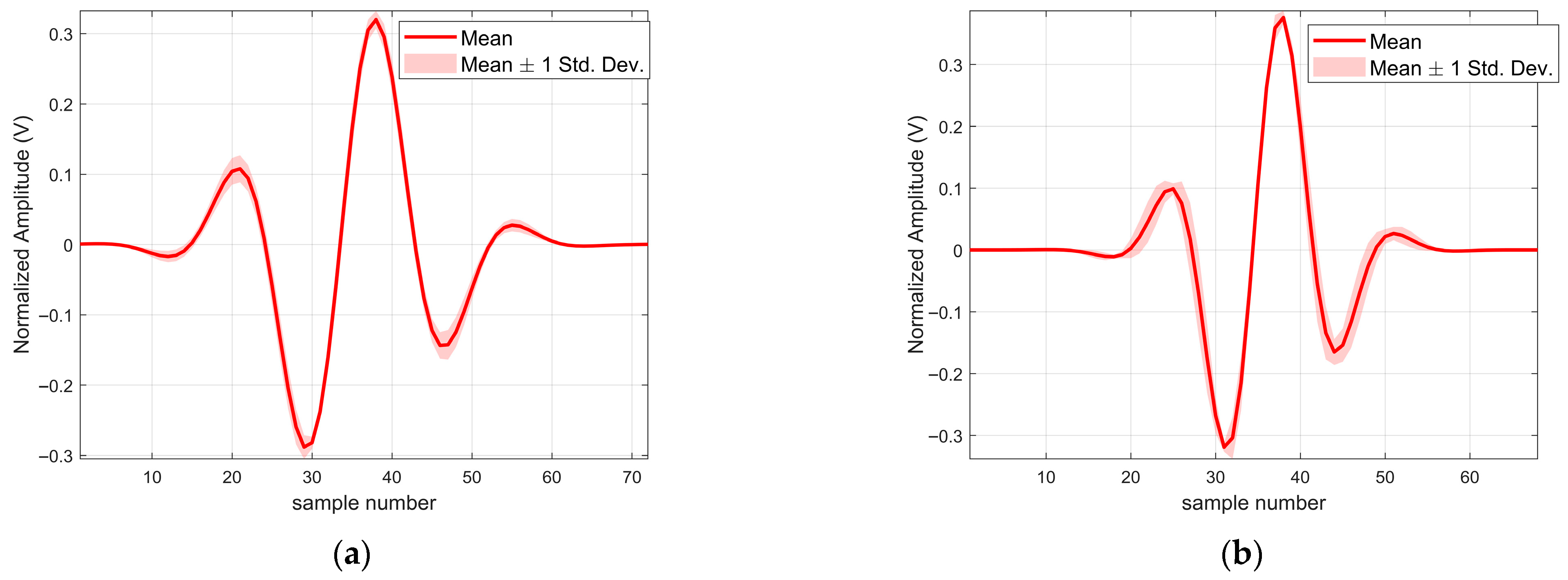

To fairly compare the proposed algorithm with SOOT, MCMC, and L1-ADMM, all experiments share unified settings: the impulse response length is Nh = 500, containing 49 evenly spaced non-zero pulses with interval 10 and amplitudes given by Equation (42). Source signals of different bandwidths are used to represent various resolution conditions. The specific source signals are shown in

Figure 4. Gaussian white noise is added with SNR levels of {5,10,15,20,25,30} dB. Each algorithm performs 50 Monte Carlo trials per SNR, with a maximum of 1000 iterations and convergence tolerance

. We define a recovered sparse sequence

as a successful estimate if its Normalized Mean Square Error (NMSE) with respect to the ground truth

is less than a given threshold

.

The prior configurations of the compared algorithms are summarized as follows:

SOOT: assumes known impulse response length Nh and uses a smoothed ℓ1/ℓ2 sparsity regularizer, with parameters tuned via validation to minimize NMSE.

MCMC: assumes Nh and an upper bound on sparsity, adopting the spike-and-slab prior with parameters validated for optimal recovery.

L1-ADMM: the same initialization as the proposed algorithm, but with the periodic projection prior on h replaced by an ℓ1 sparsity regularizer.

All algorithms are evaluated under identical noise realizations and random seeds for paired comparisons. For the baseline methods, all respective hyperparameters were individually optimized via validation to ensure a fair comparison, whereas for our proposed method, they were fixed to and for simulation scenarios. To remove the influence of amplitude scaling and time shift, all estimates are aligned before computing NMSE. A trial is considered successful if NMSE ≤ 0.2, and the success rate is reported for each SNR. Experiments are repeated with different source bandwidths to assess robustness and recoverability under super-resolution conditions.

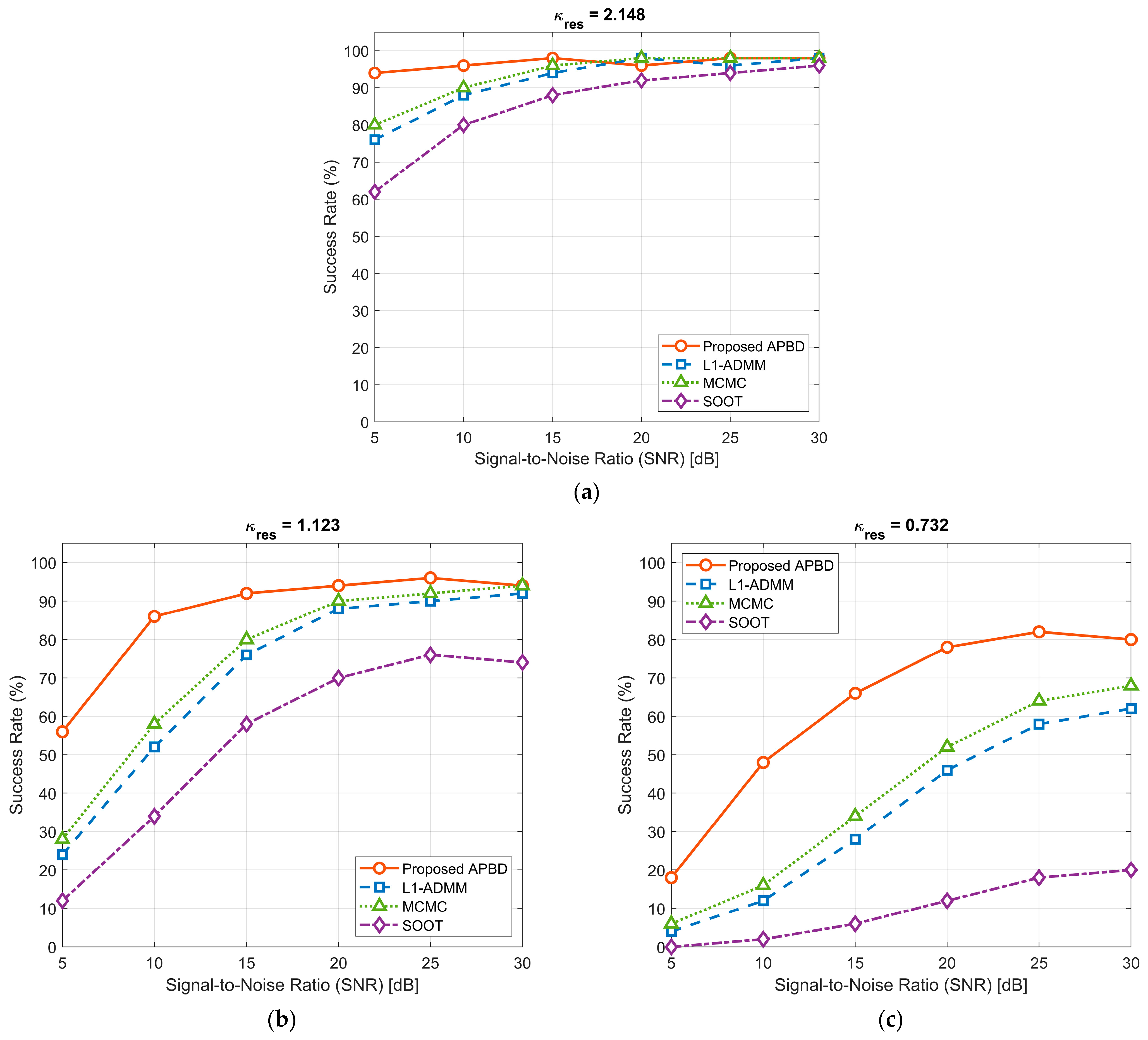

The experimental results, shown in

Figure 5, clearly demonstrate that the alignment between the prior model and the problem structure has a decisive impact on recovery performance. In the resolvable region with

, all sparsity-based methods perform well. However,

drops below 1, the ill-posedness of the problem intensifies, and performance differences become pronounced. L1-ADMM and MCMC, which rely on generic random sparsity priors, struggle to stably separate closely spaced paths under highly correlated sensing matrices, leading to a rapid decline in success rates. SOOT performs the worst due to fundamental mismatches between its physical model and the temporal structure of the channel. In contrast, the proposed algorithm employs a periodic-structure projection operator to precisely constrain the solution space onto the correct low-dimensional manifold. Even in the deep super-resolution scenario of

, the success rate remains stably above 80% for SNRs exceeding 20 dB, demonstrating outstanding robustness. These results further confirm that directly embedding a strong, structure-specific prior into the optimization process is the most effective approach for addressing such extreme recovery problems.

4.2. Measured Data Experiment and Analysis

For validation on measured data, a comprehensive dataset was acquired using a UWB fuze system. The system’s receiver architecture is based on ETS, which leverages Doppler frequency shift for high-resolution waveform reconstruction. To generate the required relative motion during experiments, the fuze system was mounted on an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that executed vertical descent maneuvers over the ground targets, simulating terminal engagement scenarios. A total of 20 independent measurements were acquired for each of two distinct ground surfaces: a smooth soil ground referred to as Surface A, and a grassland referred to as Surface B. The final segment consisting of 870 samples, recorded at a sampling frequency of 2.5 kHz, was retained from each measurement for subsequent analysis (see

Figure 6).

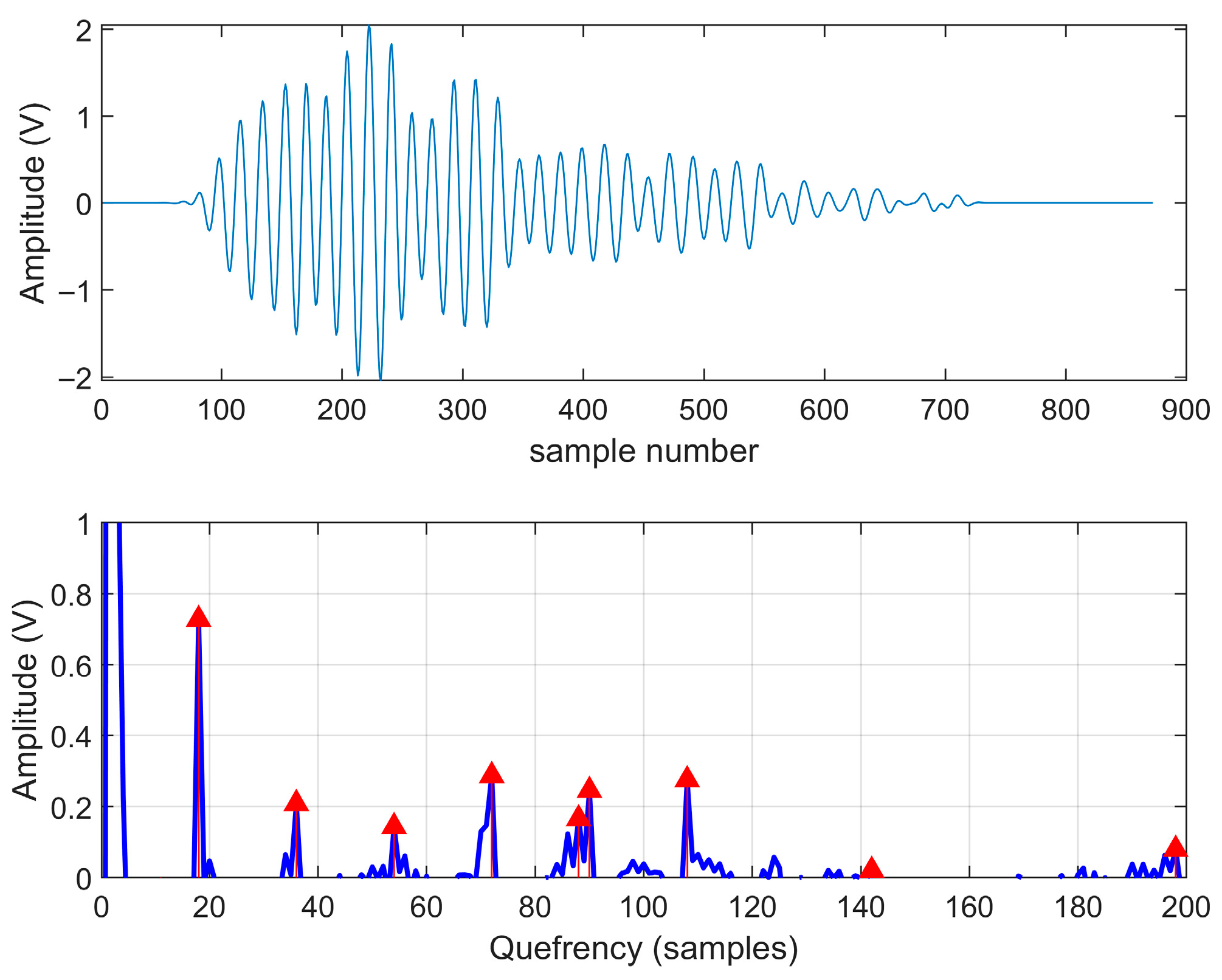

Before performing blind deconvolution on the truly measured ground echo signals, it is necessary to analyze the internal structure of the signals first. In this paper, cepsogram analysis is adopted to transform the convolution relationship in the time domain into a linear additive relationship in the cepsogram domain, thereby effectively separating the contributions of the source signal and the channel.

It can be observed that in the low-quefrency region of the cepstrum, there exists an isolated dominant peak with highly concentrated energy, a feature consistent with the cepstral morphology of short-duration, aperiodic pulses. In the high-quefrency region, the cepstrum exhibits a series of distinct and approximately equally spaced harmonic peaks, as marked by the red triangles in

Figure 7. Since the contribution of the short-duration pulse in this region has largely decayed to zero, these periodic peaks must originate from the CIR. Furthermore, the decaying trend of these peaks corroborates that the channel exhibits physically plausible energy attenuation characteristics. Therefore, cepstrum analysis empirically demonstrates that the observed signal results from the convolution of a short-duration pulse component and a channel component with inherent periodic structure. This finding provides direct and compelling justification for subsequent algorithms to incorporate periodic structural priors in modeling the channel.

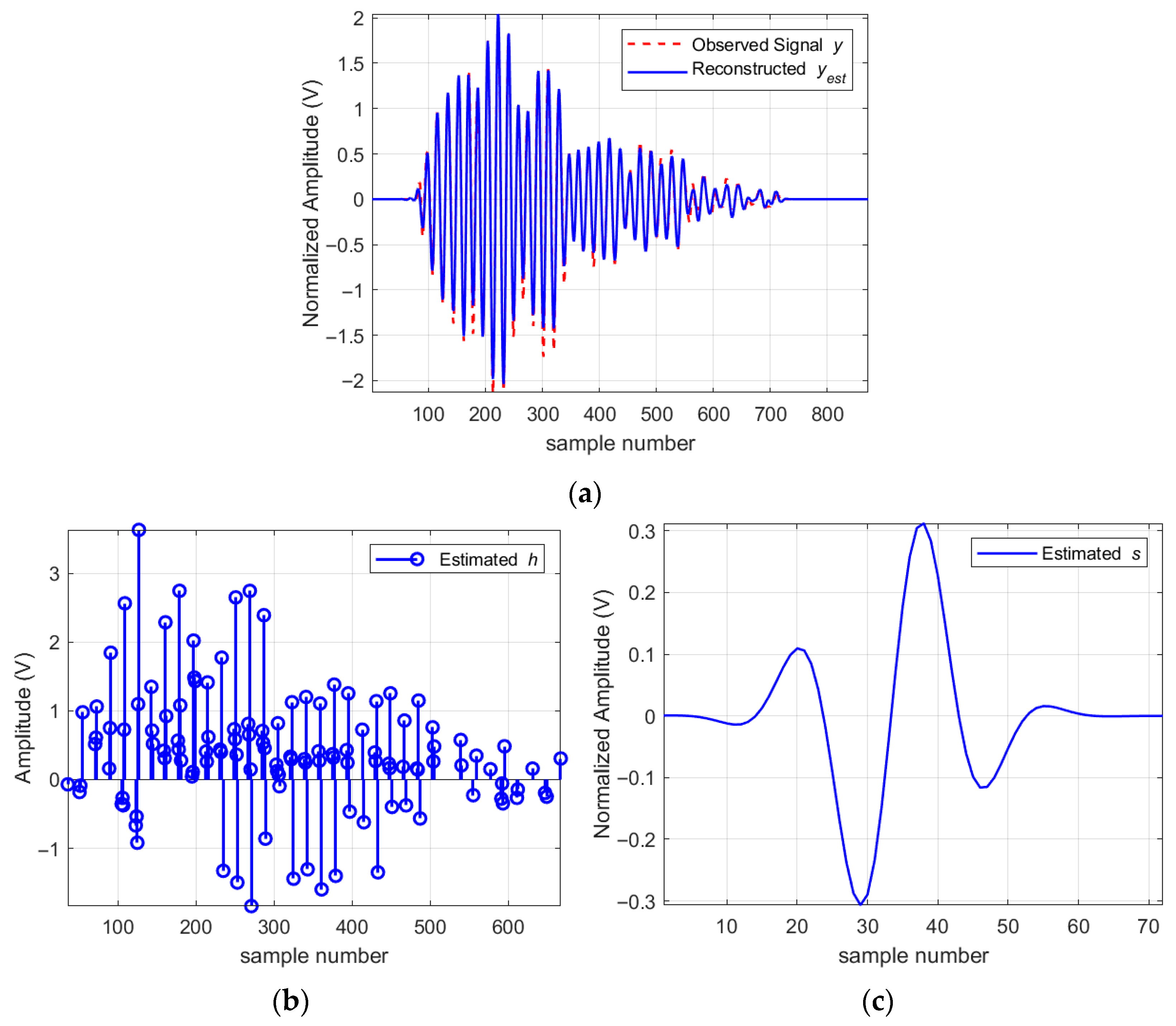

The method proposed in this paper is used to perform blind deconvolution on the observed signal to obtain the source signal and the CIR .

As can be seen from

Figure 8, the amplitude envelope of the CIR is basically consistent with the envelope of the observed signal. Due to the parametric prior, the curve of the source signal is very smooth. The resolution factor calculated according to Equation (38) is 0.751. Therefore, the CIR of the measured data is super-resolution, which gives full play to the advantages of the method proposed in this paper. This recovered CIR provides a clear manifest of the individual multipath components, transforming the ranging problem from peak detection on an ambiguous waveform to a more informed decision-making process based on identifying the true range-marker, such as the first significant path, within the now-decoupled channel structure.

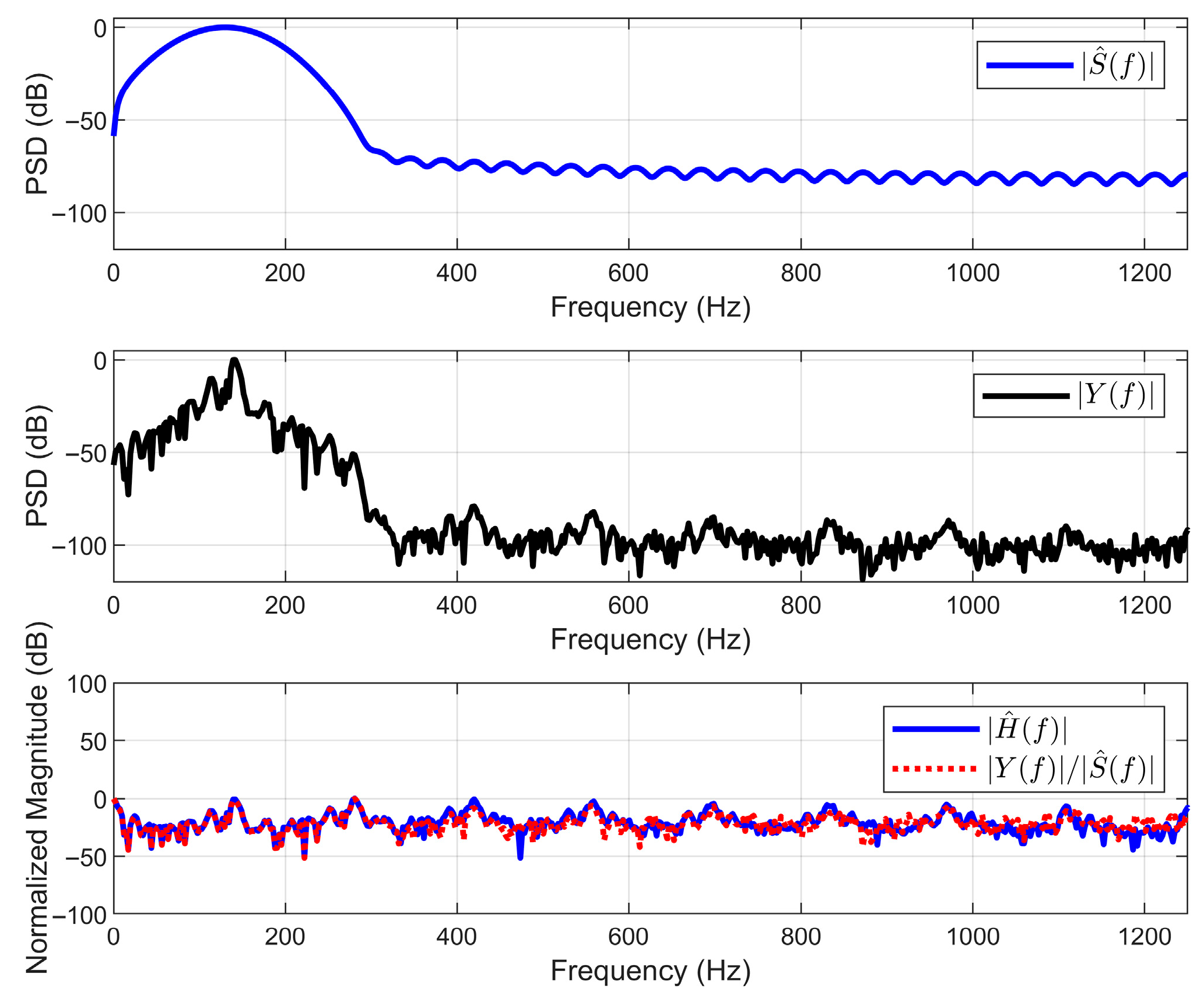

To independently verify the effectiveness and consistency of the algorithm, the recovery results are analyzed in the frequency domain. The core lies in verifying whether the solution pairs follow the convolution theorem . For this purpose, the channel transfer function directly restored by the algorithm is compared with the indirectly inferred.

As can be seen from

Figure 9, the spectrum

of the restored source signal presents a physically reasonable smooth broadband function, while the spectrum

of the observed signal shows a quasi-periodic harmonic structure under its envelope. The directly restored

and the indirectly inferred

show a high consistency in the main harmonic structure, and the deviation part mainly stems from the influence of noise. This result proves that the algorithm has successfully decoupled a solution pair that is consistent with the convolution theorem. Furthermore, the approximate comb spectral form presented by the reduced

not only explains the harmonic source of

, but also, in turn, confirms the validity of the adopted quasi-periodic structure prior.

To evaluate the recovery consistency of this algorithm when processing different measured data, we performed blind deconvolution on the measured data of two types of ground echo signals.

As shown in

Figure 10, the source signals recovered from the measured data of the same ground type (represented by the translucent curves in

Figure 10a,b) demonstrate a high degree of consistency, clustering closely around their respective clear average waveforms (solid red lines). Moreover, a comparison of the average waveforms for the two ground types reveals a strong similarity in both waveform structure and envelope morphology (see

Table 1).

To quantitatively evaluate the consistency of the algorithm in processing multiple sets of real measurements, the average correlation coefficients of the source signals recovered from two sets of measured signals were first calculated, reaching 0.9938 and 0.9956, respectively. This indicates that the algorithm can robustly recover the inherent morphological structure of the source signals from different observations with high stability. Secondly, the relative standard deviation norms were computed as 0.1296 and 0.2099, respectively. This suggests that, despite the randomness and physical variations introduced by different measurements, the overall point-by-point fluctuation of the recovery results is effectively constrained within an extremely small range (see

Figure 11).

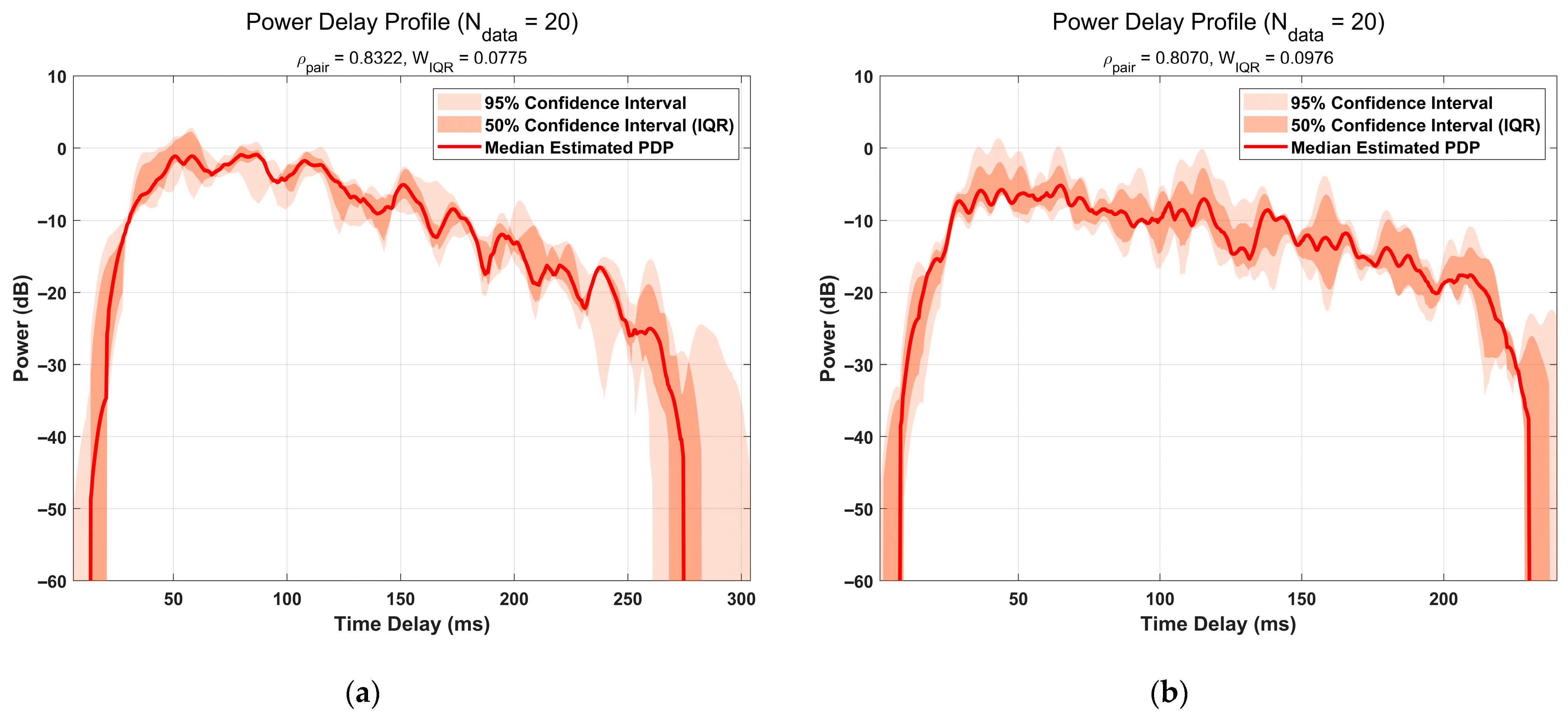

The macroscopic structure of the recovered CIR was analyzed using its PDP, where the instantaneous power was smoothed with a Gaussian window for a more stable energy trend.

Figure 10 shows a high visual consistency of the PDPs for both ground types. To quantify this consistency and the fine-waveform similarity of the CIRs, respectively, the relative IQR width of 20 PDP measurements and the average pairwise correlation coefficient of 20 CIR measurements were computed. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

The quantitative results demonstrate the algorithm’s efficacy: the low relative IQR widths (0.0775 and 0.0976) indicate stable recovery of the macroscopic energy envelope. Furthermore, the high average pairwise correlation coefficients (0.8322 and 0.8070) validate its capability to accurately reconstruct the fine-grained waveform structure.

5. Conclusions

To address the severe ranging ambiguity in UWB fuzes caused by multipath delay spread, this paper proposes and validates a blind deconvolution framework based on an asymmetric structural prior. The core contribution of this method lies in providing a tool for channel structure extraction, where the recovered fine-grained multipath information offers essential theoretical insights and analytical foundations for fundamentally understanding and resolving the ranging ambiguity induced by signal aliasing. The simulation experiments verify the effectiveness and robustness of the framework, thereby providing the necessary confidence for its application to measured data. The main conclusions of the simulation and actual measurement analysis are as follows:

First, we established and validated an equivalent discrete multipath model to effectively characterize the ground CIR. We further confirm the hypothesized quasi-periodic structure of the channel through cepstral analysis of measured signals. The cepstrum of real echo data clearly shows distinct, evenly spaced harmonic peaks, providing direct and data-driven evidence of the channel’s inherent periodicity. This key finding provides both physical and empirical justifications for discarding generic random sparsity assumptions and designing a targeted periodic structural prior.

Second, in the challenging deep super-resolution scenarios () encountered with the measured data, the proposed framework successfully recovered the underlying periodic channel structure, whereas conventional algorithms failed. This result demonstrates the decisive advantage of our novel periodic sparse cluster projection operator in overcoming fundamental resolution limits.

Finally, analysis of multiple measured datasets confirmed the algorithm’s high consistency and repeatability. The recovered source signal exhibited high morphological consistency. Concurrently, the channel PDPs showed excellent stability in their macroscopic energy structure. Together, these results validate the framework’s ability to robustly decouple a stable source signal from a consistent channel representation in real-world scenarios.

These findings highlight the algorithm’s strength in channel structure extraction, positioning it primarily as a powerful offline analysis tool. This perspective guides future work in two key directions: leveraging the recovered CIRs as a benchmark for developing improved real-time ranging algorithms and using their statistical properties for terrain characterization to enable future terrain-adaptive fuzes. While the current method is best suited for uniform terrains, extending it to non-uniform scatterers remains an important challenge. Ultimately, this work provides a foundational methodology for understanding and overcoming ranging ambiguity in UWB fuzes.