This section is organised into four subsections, which describe the data acquisition hardware, the control software, the experimental setup for sensor calibration and validation, and the field installation. While this section provides a concise overview, comprehensive technical details are provided in the appendices.

2.1. Hardware

This sub-section details the development of the picoSMMS, a low-cost, off-grid monitoring station designed to measure and record soil moisture and temperature. The core of the picoSMMS is a data acquisition and logging system, hereafter referred to as the picoLogger. The picoLogger is designed around a central compute module with several peripheral components to facilitate the measurement and recording of soil moisture and temperature data. The design prioritises the use of readily available, well-documented, and affordable components to ensure high reproducibility. A list of materials, along with the specifications of each component and a rough estimate of their cost, is provided in

Appendix A.1.

The central compute module of the picoLogger is the Raspberry Pi Pico, hereafter referred to simply as Pico. It was selected for its low cost, extensive documentation, wide consumer adoption, and robust support for various communication protocols, including I2C, SPI, and UART, which are essential for interfacing with the system’s peripheral modules.

The LCSMS, as seen in

Figure 1, constitutes the main sensor. It provides an analog voltage output, which requires conversion to a digital signal for processing. While the Pico features a built-in Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC), its resolution is limited, and its accuracy is susceptible to noise from the Pico’s switching-mode power supply. To ensure high-precision measurements [

40], an external 16-bit ADC, the ADS1115, is employed. This module communicates with the Pico via the I2C protocol and provides four input channels. Three channels are dedicated to reading data from the LCSMS, while the fourth is used for monitoring the system’s battery voltage via a voltage divider circuit.

Accurate timestamping of the collected data is critical for temporal analysis. To this end, a DS3231 Real-Time Clock (RTC) module is integrated into the picoLogger. The DS3231, which also communicates via I2C, provides precise and temperature-compensated timekeeping and has a backup battery, ensuring data integrity even in the event of a main power failure.

For data storage, the 2 MB of onboard flash memory on the Pico is insufficient for long-term, high-frequency data logging. Therefore, a microSD card module is incorporated to provide expandable storage capacity, allowing for extended, autonomous data collection campaigns. This module interfaces with the Pico via the SPI protocol.

The system is powered by a 3000 mAh LiPo battery, which is charged by a 1 W solar panel via a dedicated solar charger module (DFRobot DFR0264). To ensure stable and safe operation, the power management circuitry includes a Schottky diode for reverse current protection and a Zener-clamp circuit to regulate the solar panel’s output voltage. An IRFZ44N MOSFET (Infineon Technologies, Prague, Czechia) is used to switch power to the peripherals, minimising idle power consumption. This power system is designed for perpetual, off-grid operation; a detailed power budget analysis is provided in

Appendix A.

In addition to the core components, several peripherals are integrated for user interaction and diagnostics. These include an RGB LED for visual status indication, two toggle switches for power and function control, and a UART interface for accessing operational logs.

The picoLogger, its current version as seen in

Figure 2, is designed to interface with two types of sensors: the LCSMS for measuring soil moisture and the DS18B20 (hereafter referred to as STS), as seen in

Figure 3, for measuring soil temperature. The exposed electronics on the LCSMS units are waterproofed using a custom 3D-printed housing filled with epoxy resin. The STS units are pre-packaged in a waterproof metal casing. All external components are connected to the main unit via robust, waterproof AMP SuperSeal connectors.

The entire picoLogger is housed within a custom-designed, 3D-printed enclosure. The internal components are assembled on two perfboards for a compact and organised layout. The cost of materials for the entire station was less than UDS 100. Further details on the physical assembly and wiring are available in

Appendix A.

2.3. Experimental Setup

To assess the accuracy and reliability of the LCSMS, a rigorous calibration and validation procedure was conducted in a controlled laboratory environment following the guidelines proposed by Jones et al. [

32] and closely modelled after Bogena et al. [

8].

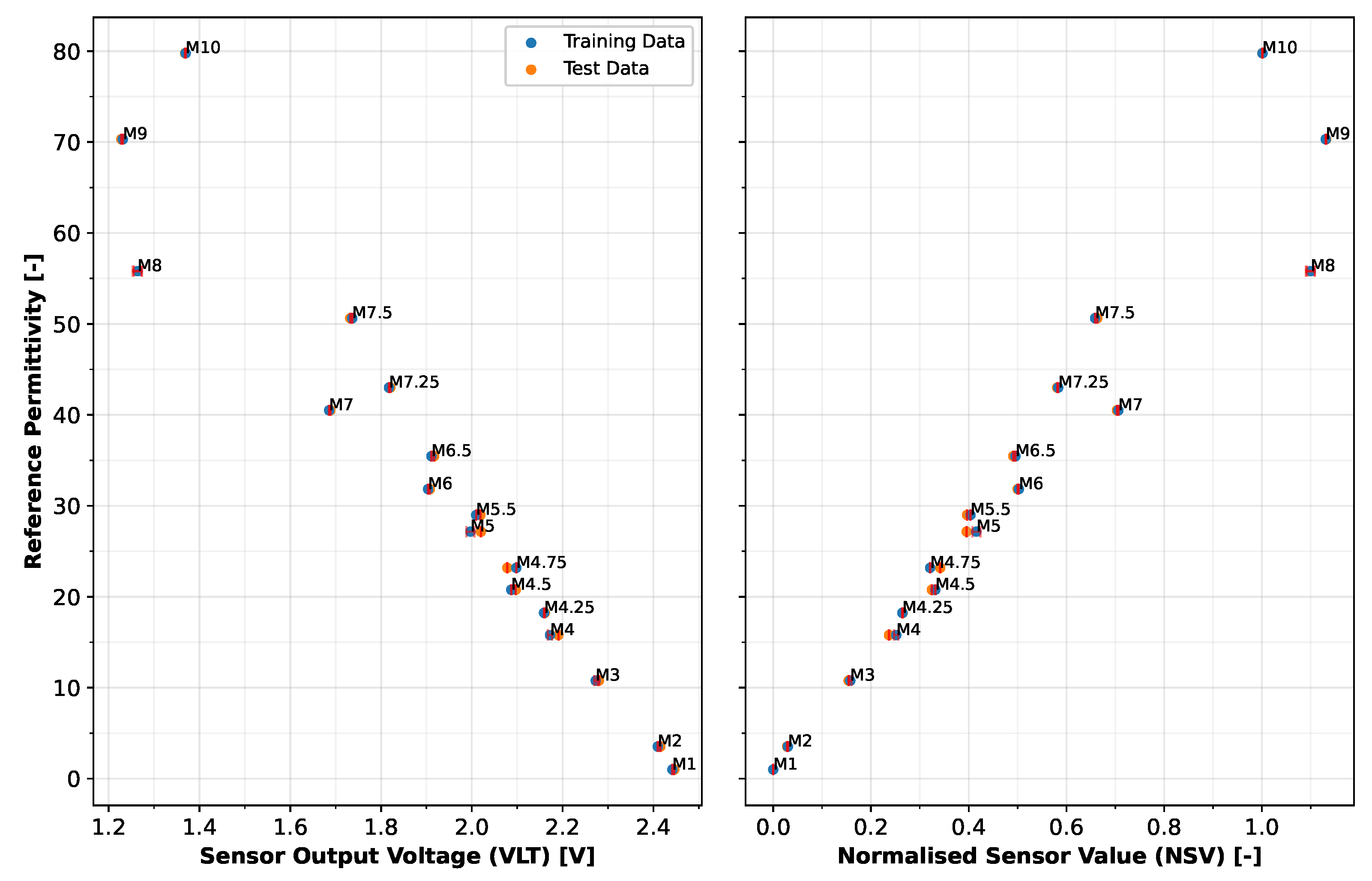

Liquids with well-defined

values ranging from 1.0 (air) to approximately 80.0 (deionised water), hereafter referred to as “reference media”, were prepared using approximately 15 L of 2-isopropoxyethanol (i-C3E1; Art.-Nr. 8706.2, Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), 10.5 L of deionised water, and soda lime glass beads (type: Silibeads 4501, Sigmund Lindner GmBH, Warmensteinach, Germany) with a grain size of 0.25–0.5 mm. The glass beads, when thoroughly shaken to achieve good packing, exhibit a permittivity of 3.34 at 25 °C and a porosity of 0.38 [

8]. These media, detailed in

Table 1, were designed to cover the full spectrum of permittivities with particular focus on the range encountered in typical inorganic-heavy soils. The permittivities of each medium were measured using Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR; CS645 from Campbell Scientific Inc., Logan, UT, USA) probes at the respective experimental temperatures and are hereafter referred to as “reference permittivity or (

)”. Additional equipment included magnetic stirrers with a hot-bed, a sieve shaker, thermometers, and standard laboratory glassware.

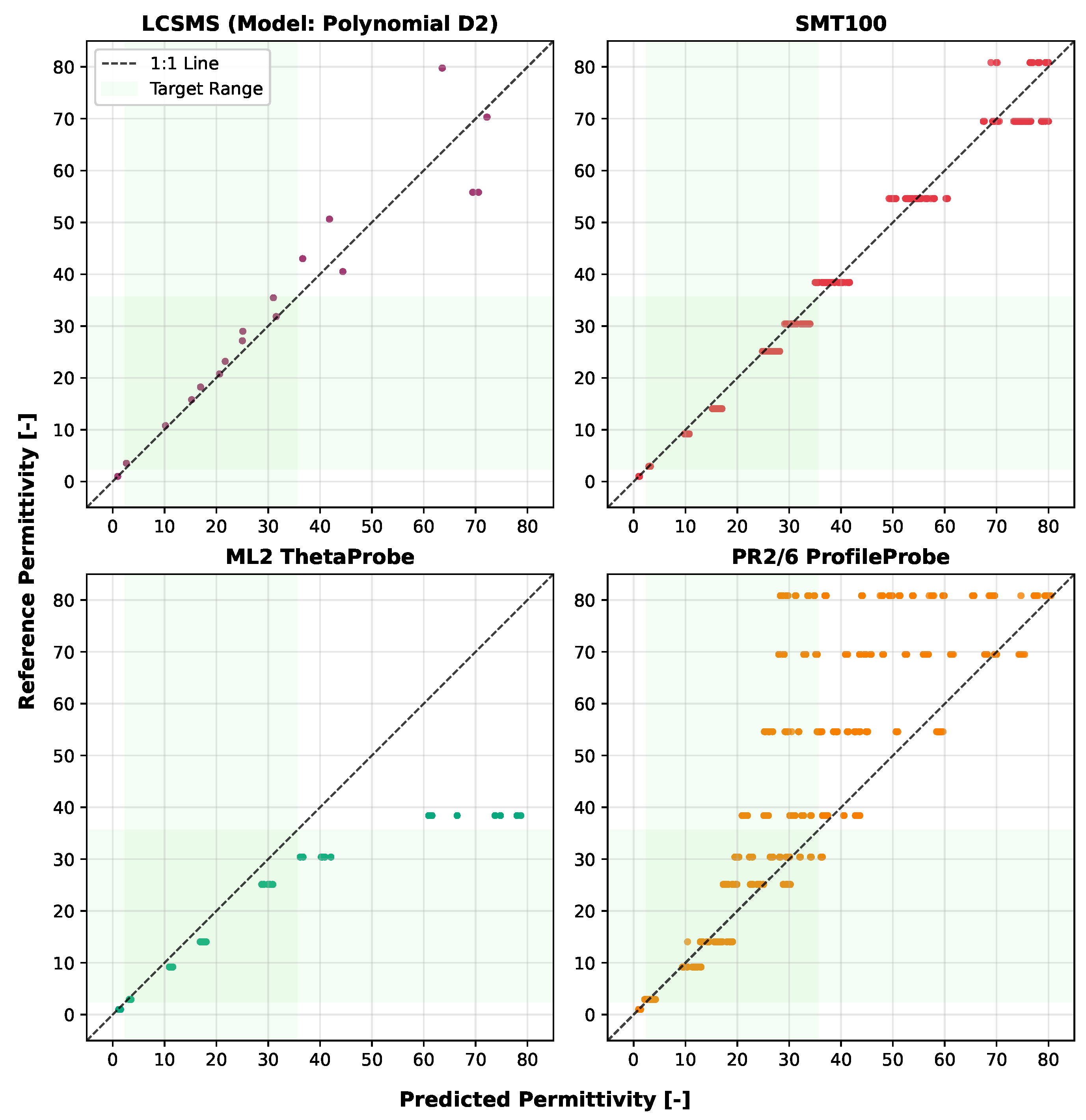

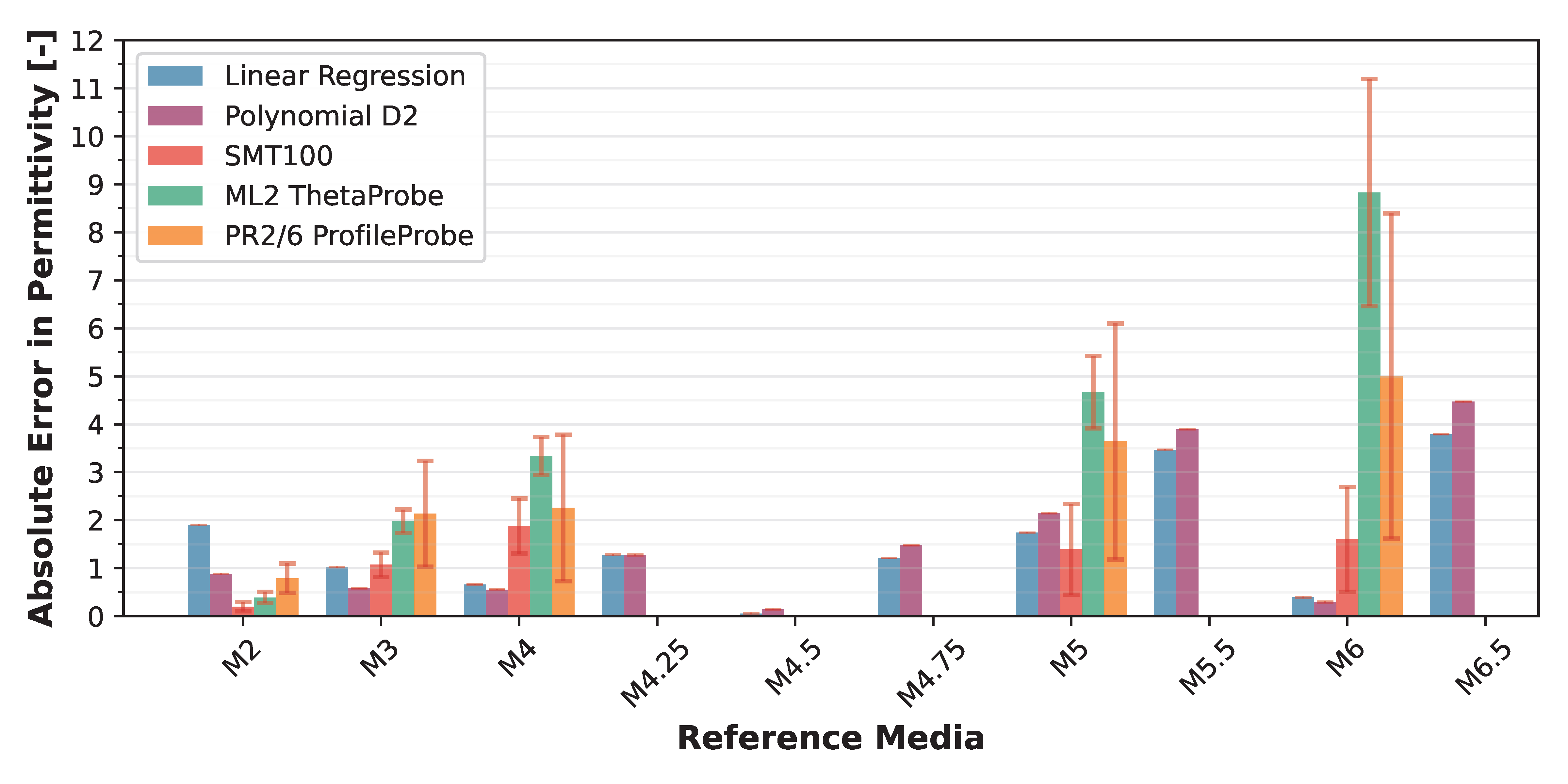

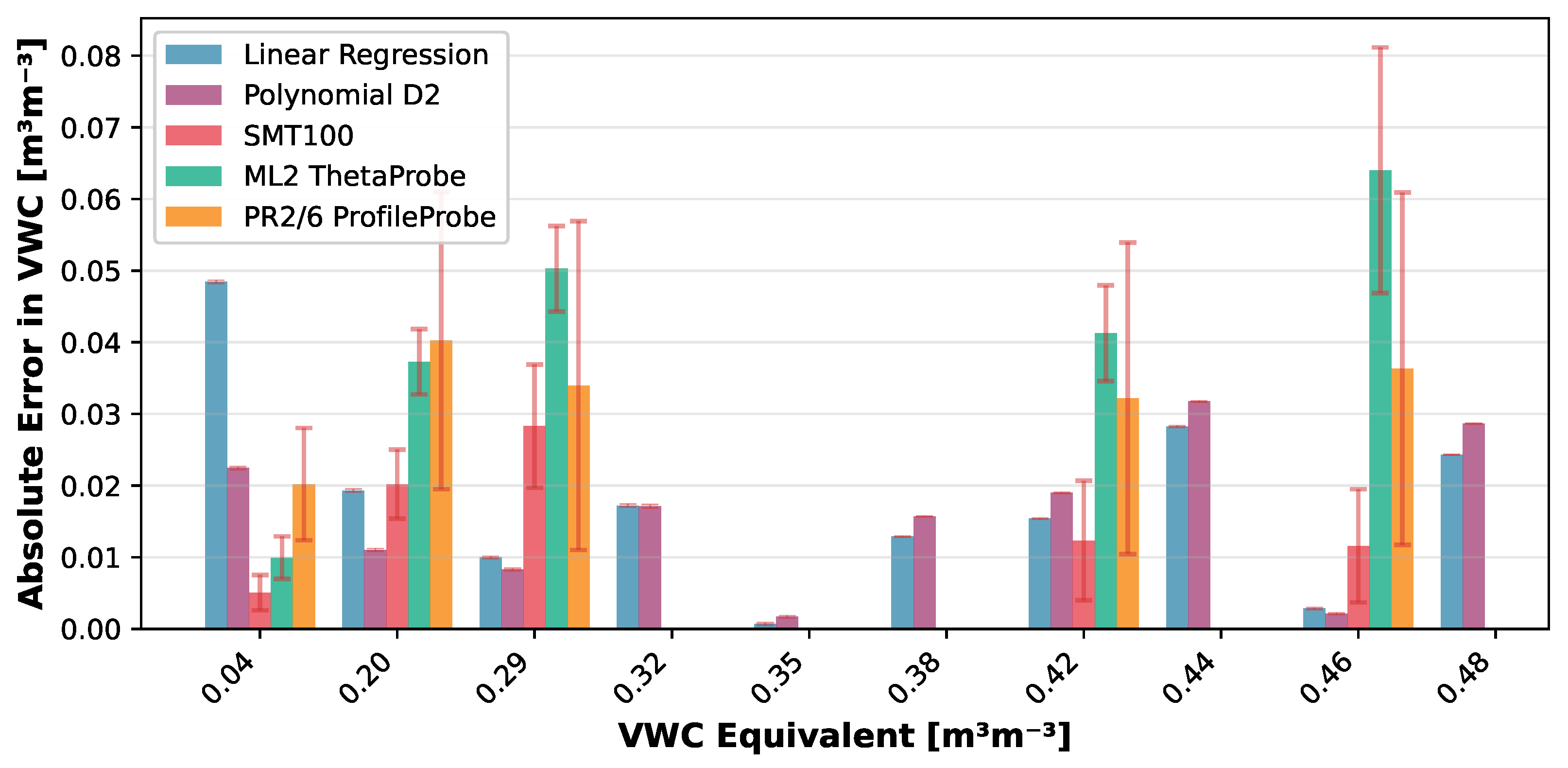

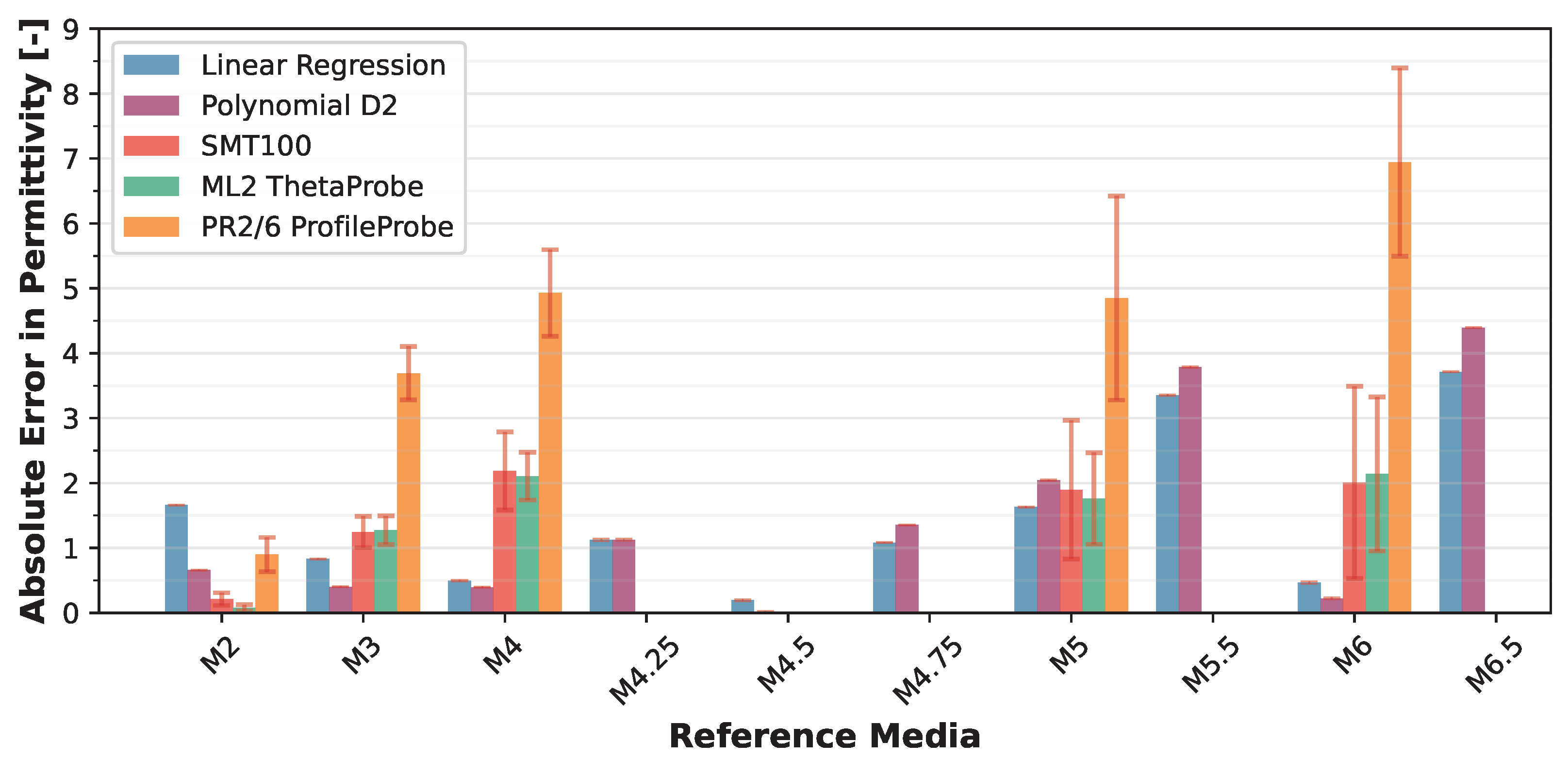

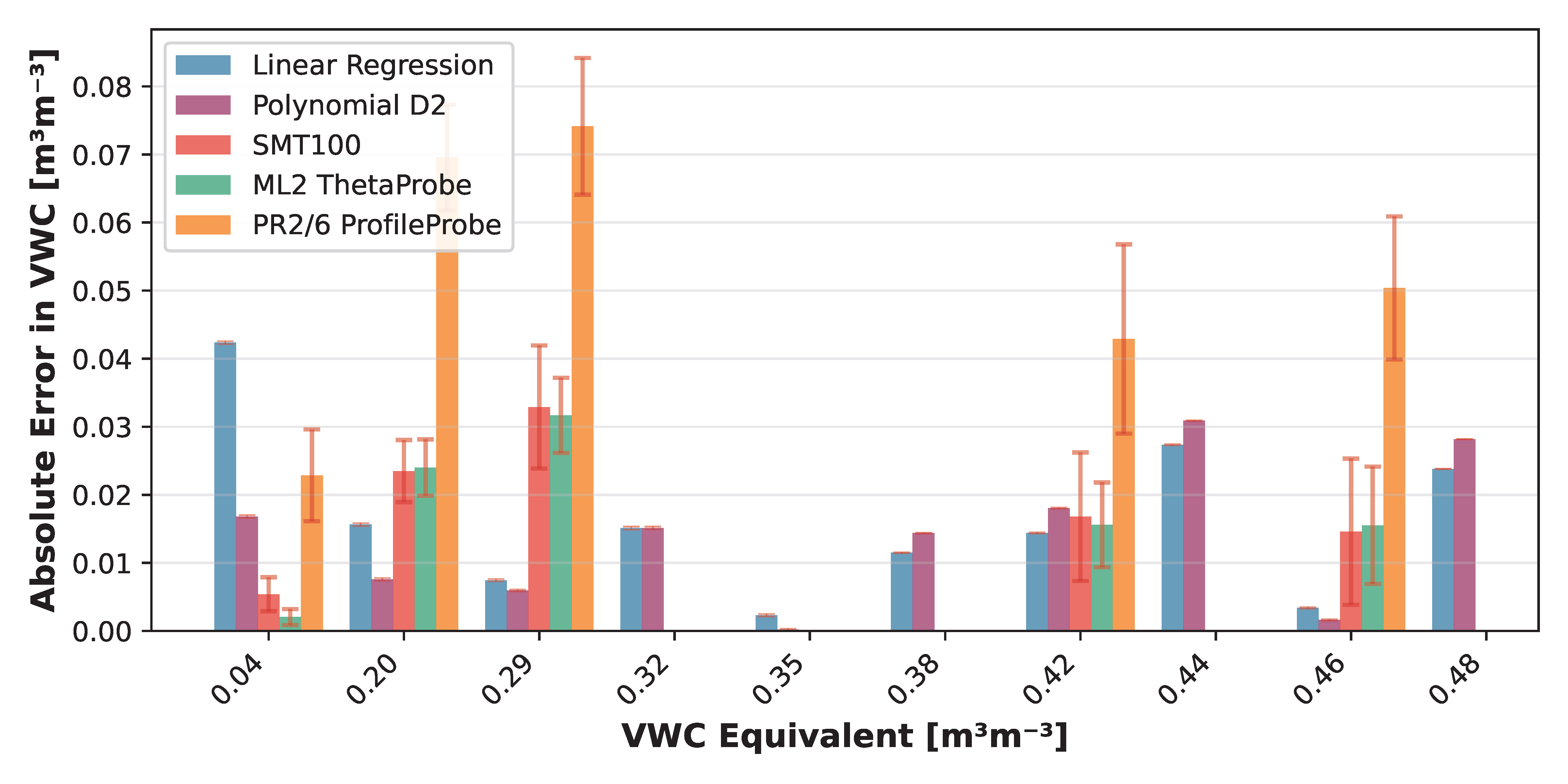

The calibration and validation experiments were conducted in two phases. The first experiment, carried out in 2022 as part of a previously unpublished study, subjected a diverse set of commercial sensors—SMT100 (TRUEBNER GmbH, Neustadt, Germany), ML2 ThetaProbe (Delta-T Devices Ltd., Cambridge, UK), and PR2/6 ProfileProbe (Delta-T Devices Ltd.), hereafter referred to as “benchmark sensors”—to validate across reference media at 17 ± 1 °C. A subsequent experiment in 2025 focused on calibration and validation of the LCSMS at 25 ± 1 °C, employing a similar but refined protocol that included additional intermediate reference media within the critical permittivity range (2.5 to 35.5) typical of inorganic-heavy soils. The 2022 benchmark sensor dataset provided comparative context for evaluating the calibrated LCSMS performance.

The experimental apparatus comprised the following components. Two LCSMS units paired with a soil temperature sensor (STS; DS18B20) were interfaced with the picoLogger for data acquisition. Six SMT100 sensors, five ML2 ThetaProbe units (), and three PR2/6 ProfileProbe units were read, using a fixed immersion depth, via an Arduino Uno-based data acquisition system. Three TDR probes provided reference permittivity measurements and were read manually through a CR6 datalogger. The measurements, excluding the LCSMS temperature-sensitivity tests, were conducted in ten containers (6.4 dm

3 HDPE bottles and PVC containers) selected to be sufficiently large to minimise edge effects. For the LCSMS temperature-sensitivity tests, sensors were positioned diagonally in a beaker with the sensing side facing downwards, as the sensor’s limited sensing volume minimises fringe effects; notably, approximately 5 mm of the bottom-most portion of the LCSMS, where no capacitive traces are present, does not contribute to sensing. Examples of the measurement setup are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

A standardised protocol was followed for all measurements to ensure consistency and repeatability. Prior to each measurement, liquid solutions were thoroughly stirred, and the glass bead medium was homogenised using a sieve shaker for 120 s.

To investigate the relationship between the sensor’s output and permittivity, each probe was fully immersed in the centre of its container as their readings were recorded. PR2 ProfileProbe measurements were taken for each of the six rings individually by adjusting the immersion depth. The temperature of the medium was recorded concurrently for all measurements. To prevent cross-contamination, sensors were rinsed with deionised water after each measurement, and containers were kept closed to minimise evaporation. For the LCSMS, two sets of 25 readings were recorded with 0.1 s intervals between readings and 15 s intervals between sets. The measurements of LCSMS were taken at a stable temperature of 25 ± 1 °C, while that of benchmark sensors were taken at a stable temperature of 17 ± 1 °C. For the benchmark sensors, 20 readings were taken in each medium at 15 s intervals over a 300 s period.

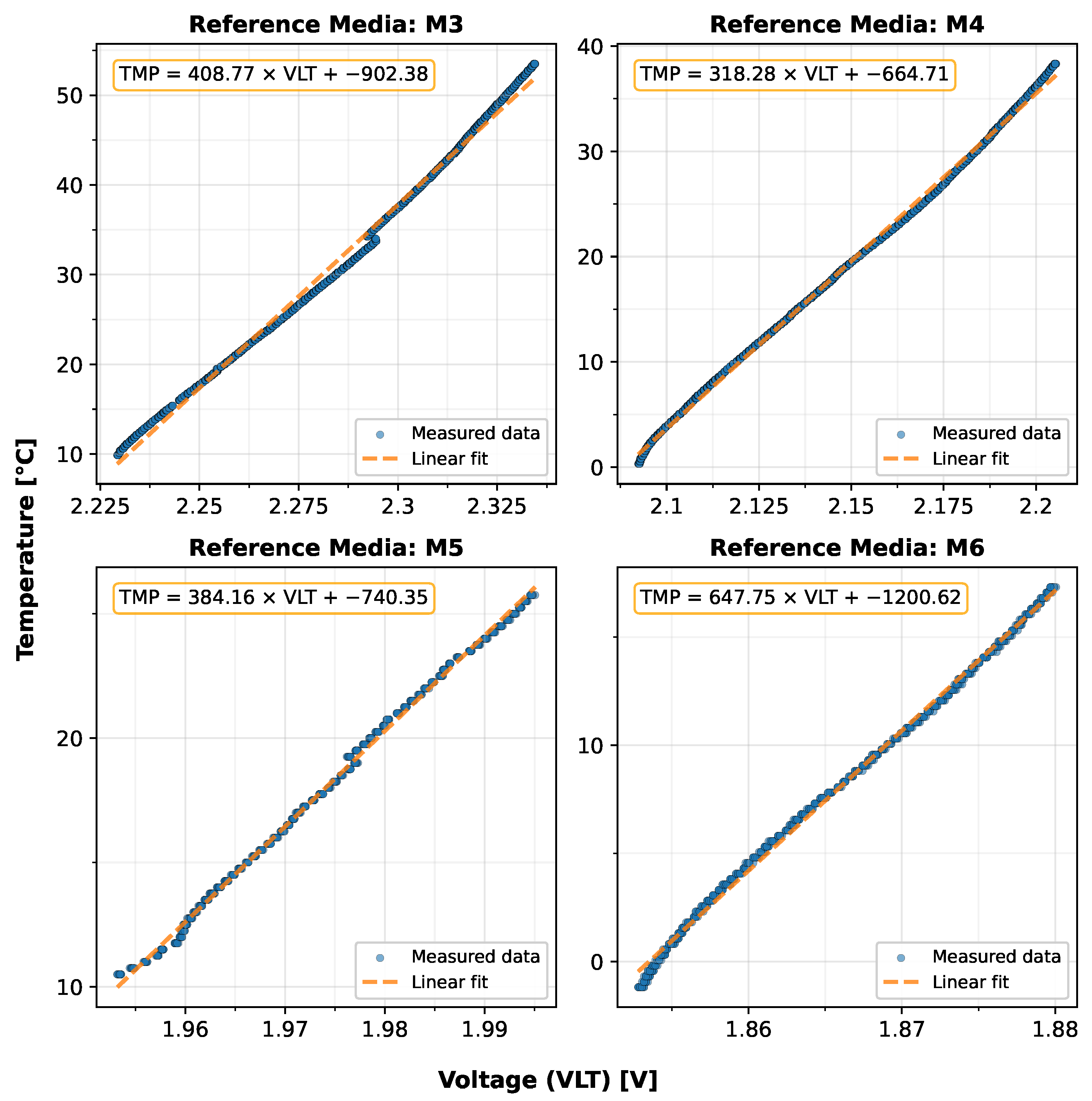

To investigate temperature effects of LCSMS, LCSMS and STS were immersed in selected reference media (M3, M4, M5, and M6) that was initially cooled and then subject to gradual heating on a hot-plate along with continuous stirring using a magnetic stirrer. Readings from LCSMS were recorded for every 0.1 °C change in temperature; initial and final readings were discarded to account for thermal equilibration time.

The raw value from an LCSMS reading is a 16-bit signed integer reading from the ADC, henceforth referred to as “raw sensor value” of

that corresponds to the voltage output of the LCSMS sensor, henceforth referred to as “sensor/LCSMS output voltage” or

. Given that the ADS (ADS1115) was configured with a gain of 4.096 V, as in this case, the relationship between the LCSMS’ output voltage and the raw sensor value is given by Equation (

1):

where 32,767 is the maximum 16-bit signed integer value.

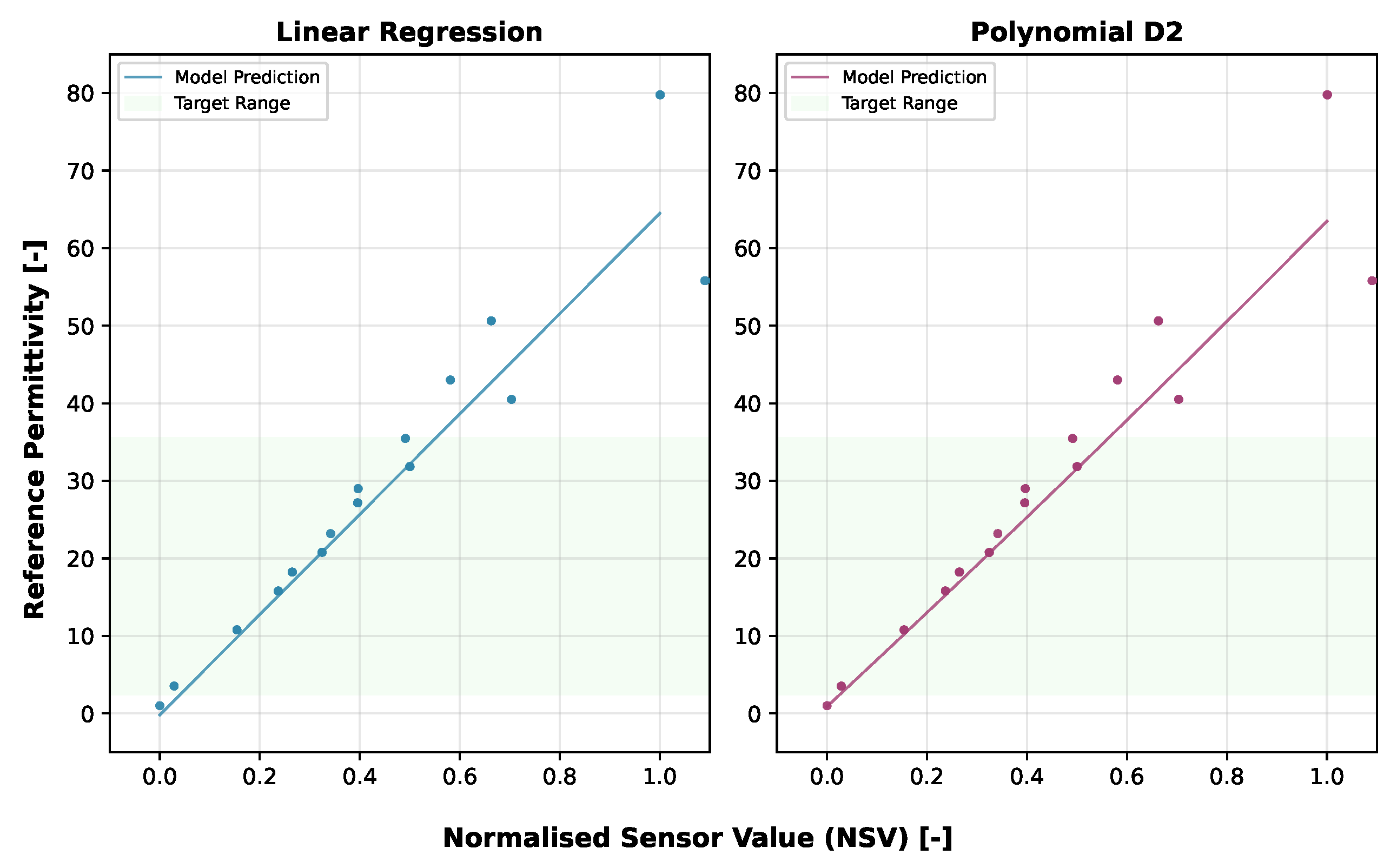

The procedure for the LCSMS was conducted using two units: one for model calibration and the other for independent validation. The objective was to establish a model,

, that predicts the permittivity of the media the sensor is exposed to, from the normalised sensor value (

; a normalised value of the sensor output as described in Equation (

2)) and the temperature of the said media (

, in °C). The permittivity predicted from such models shall henceforth be referred to as “predicted permittivity” or

. The raw sensor value was normalised for each sensor using measurements in air and deionised water, effectively scaling each sensor’s output to a common reference frame from 0 (air) to 1 (water), with normalised values increasing with increasing permittivity, as shown in Equation (

2).

where

is the raw sensor value in air, and

is the raw sensor value when fully immersed in deionised water.

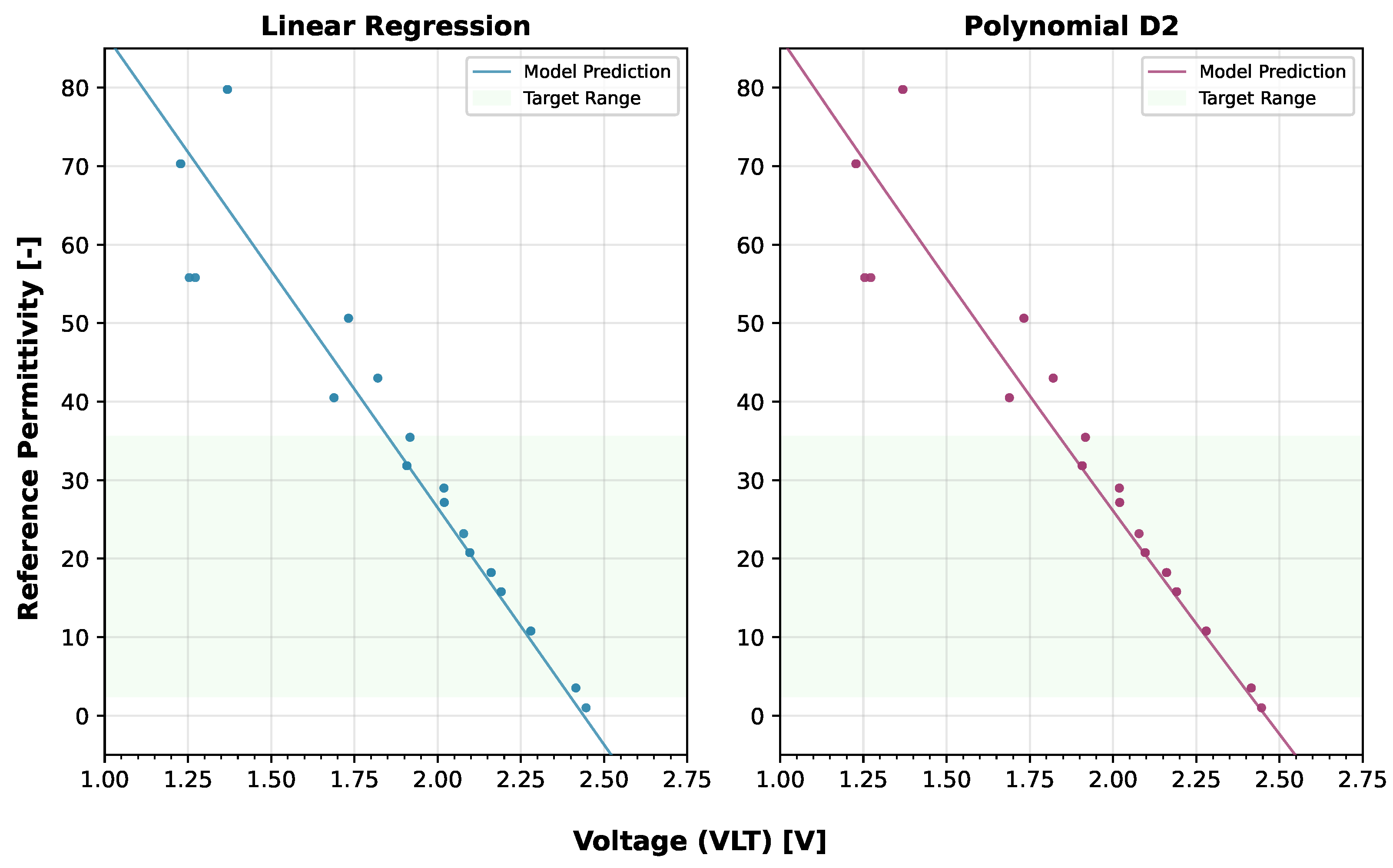

The operating principle of LCSMS is based on a capacitor formed by two PCB traces acting as plates with the surrounding medium serving as the dielectric. The sensor’s output is therefore sensitive to the physical dimensions of these traces, including their thickness, spacing, and coating. Due to the low-cost manufacturing process, dimensional inconsistencies are anticipated, leading to non-negligible variability between individual sensor units. While this variability was not formally quantified in this study, the normalisation procedure establishes a common measurement scale. To assess the effect of normalisation, similar models were also trained using the sensor’s output voltage and corresponding temperature, henceforth referred to as “VLT-trained models” whose performance was compared with that of models trained on normalised sensor values, henceforth referred to as “NSV-trained models”.

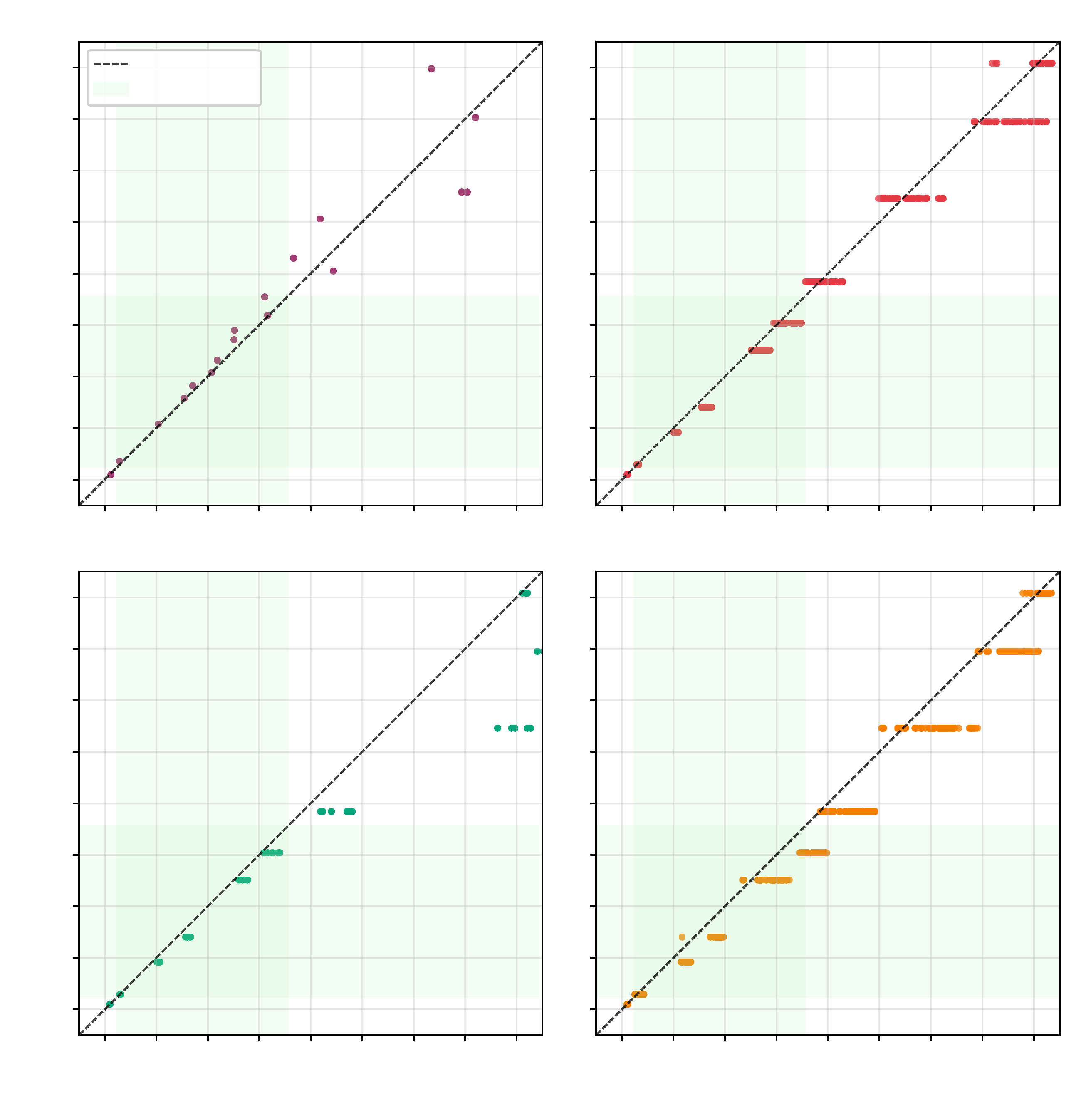

Several modelling approaches were evaluated to predict permittivity from the normalised sensor value and temperature, including Linear, Polynomial, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Support Vector Regression. The training dataset comprised 12,075 samples with feature inputs being (1) voltage reading (VLT) and temperature (TMP), and (2) normalised sensor value (NSV) and temperature (TMP). To focus the calibration on the permittivity range most relevant to typical inorganic-heavy soils, a weighting scheme was employed during model training, prioritising accuracy within the 2.5 to 35.5 permittivity range by assigning a weight of 1.0 to samples within this range and 0.1 to samples outside it. This resulted in 11,875 of the 12,075 training samples being given higher priority. For validation, the second sensor was subjected to all reference media and its output was recorded, generating 83 unique test samples. As a validation strategy, resulting measurements were used to predict permittivities with the trained models, and the predicted permittivities were then compared to the reference permittivities, with results presented in the subsequent sections.

Similarly, for the benchmark sensors, a two-point normalisation procedure was applied. Given that the deviation in the measured variable can be assumed linear, measurements in air and deionised water were used to correct the sensor outputs. This approach preserved the manufacturer’s conversion from the primary measured variable to permittivity. For the ThetaProbe units and PR2/6 ProfileProbe units, voltage values were corrected, while for the SMT100 sensors, the permittivity reported by the sensor was treated as the primary variable and adjusted accordingly to preserve the manufacturer’s device-specific conversion. Ref. Francke and Terschlüsen [

41] provides a detailed description of this procedure, along with an R-package to perform such recalibrations. The permittivities reported by benchmark sensors using the manufacturer-provided calibration shall henceforth be referred to as “measured permittivity”.

For data management, raw data gathered by the Arduino logger from the benchmark sensors, stored on its SD card, was exported to Excel, organised by date, time, and sensor ring, and merged with manually recorded temperature and medium information. For the LCSMS experiments, individual data files were merged into a single pandas dataframe containing sensor ID (SID), temperature (TMP), reference media (SOL), reference permittivity (EPS), and raw sensor value (RSV), which was then exported to a single CSV file.