An Annular CMUT Array and Acquisition Strategy for Continuous Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

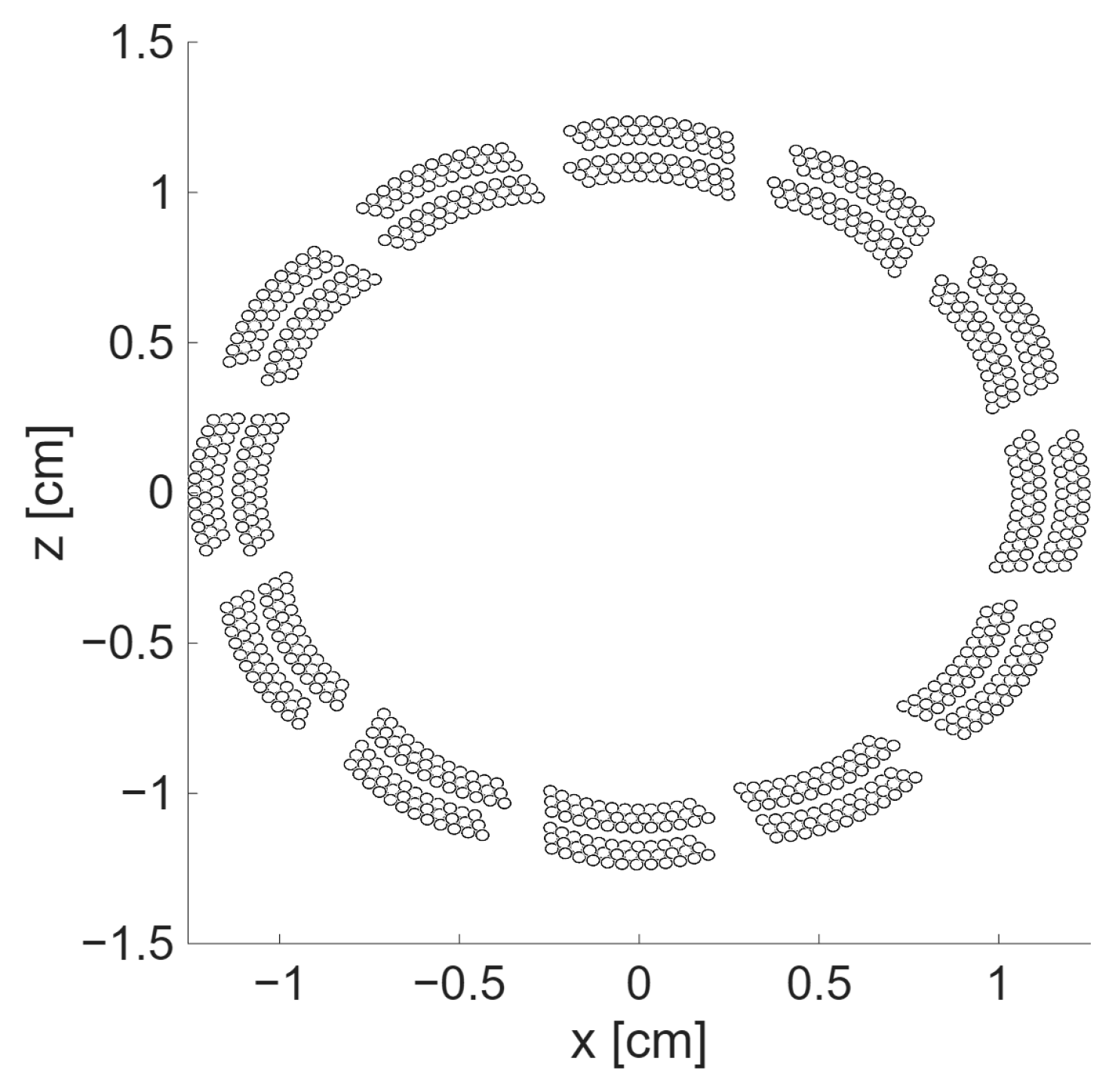

2.1. Transducer Design and Fabrication

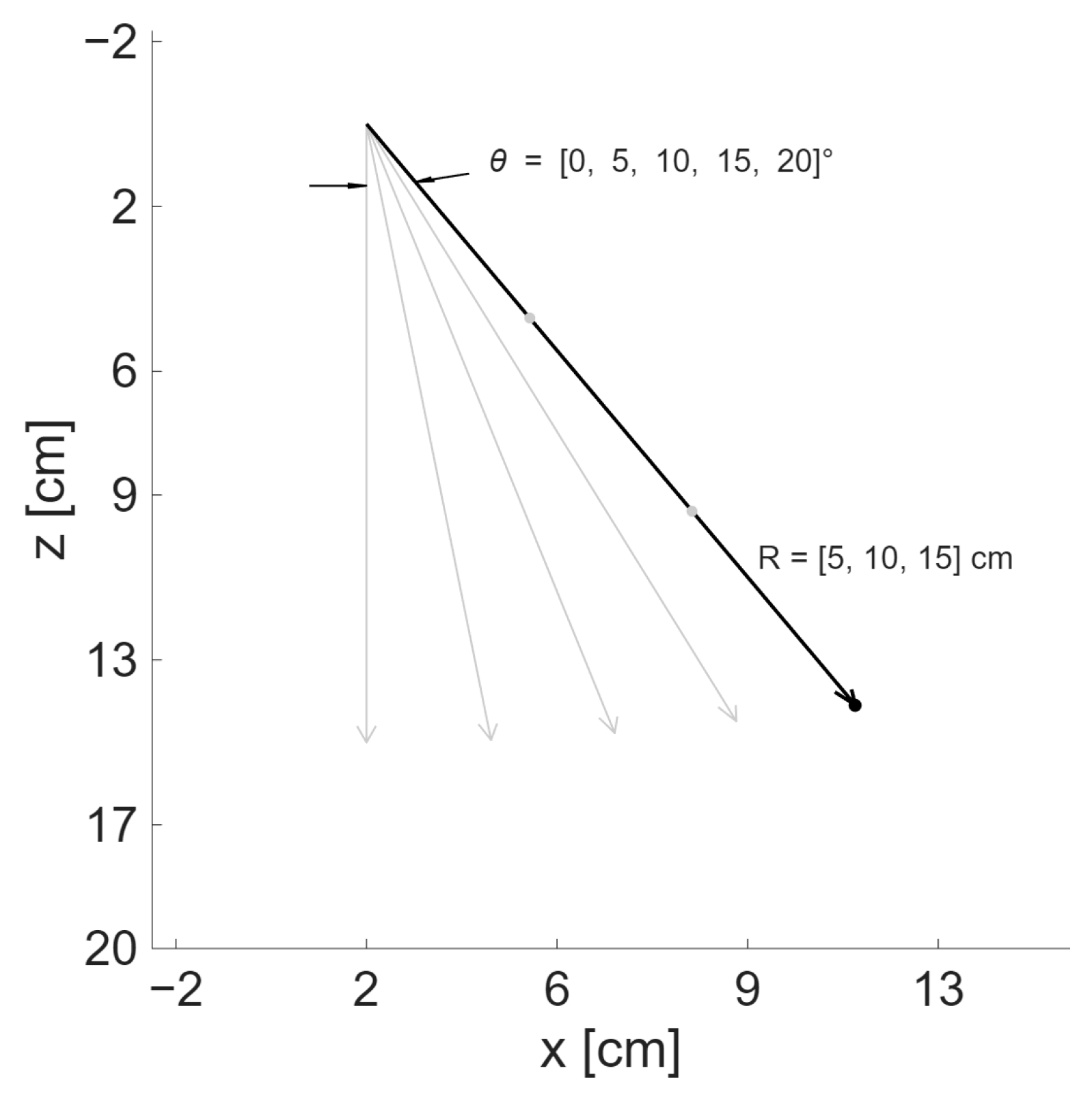

2.2. Transmission Sequence Design

2.2.1. Simulation Method

- be the position of a single scatterer.

- be the position of the i-th transmitting element.

- be the position of the j-th receiving element.

- Spherical spreading factor

- Attenuation, for which a uniform coefficient may be specified, giving

- Scatterer directivityScatterer directivity only applies to density scatterers, which behave as dipoles. For improved comprehension, only bulk-modulus scatterers, i.e., monopole-like scatterers, are modeled in the upcoming analysis.

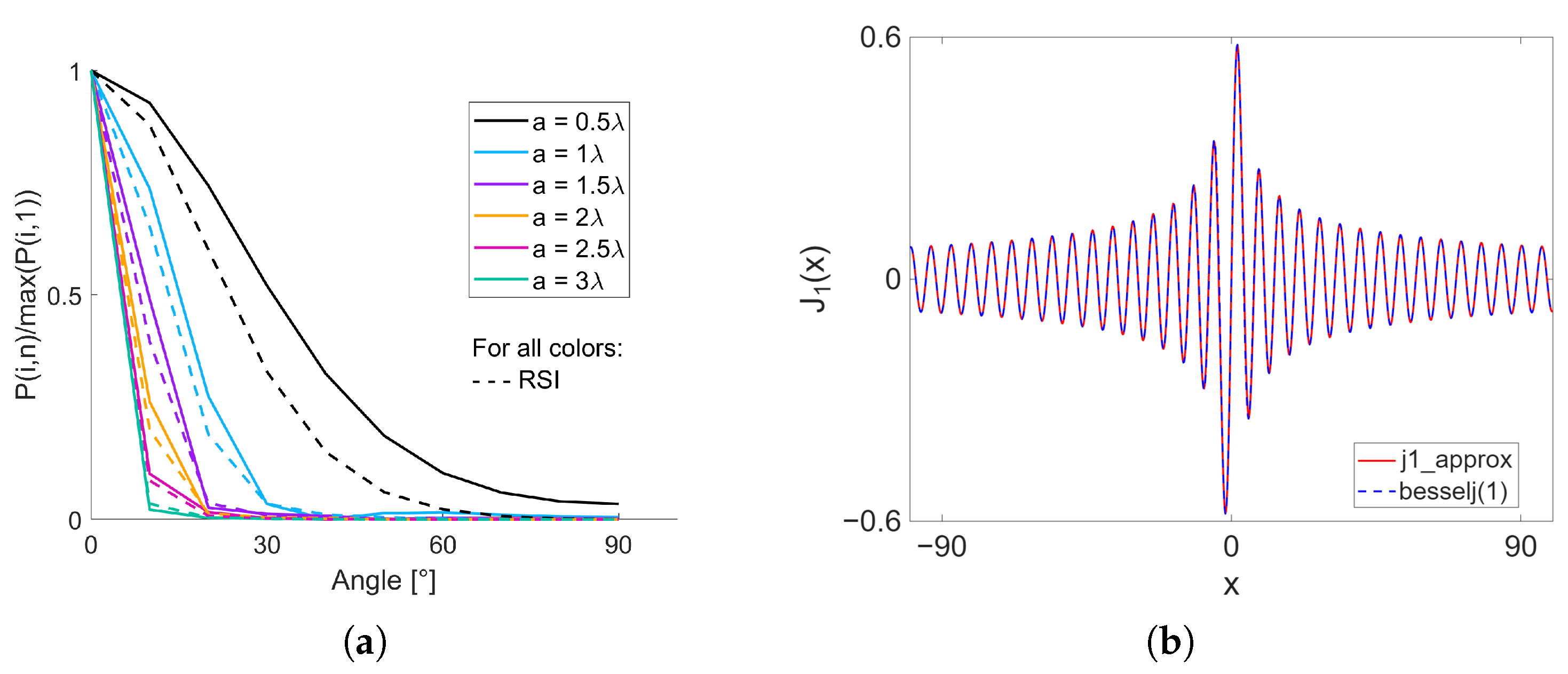

- Element directivity, which is modeled with a Bessel-based scalingwhere is the first-order Bessel function and is the element width relative to the center wavelength, so

2.2.2. Simulation Steps

- For the three VSs patterns, the transmission delays corresponding to each VS were computed and assigned as independent transmission events.

- For the focused transmission, the delays to focus and steer the beam to the location of the point scatterer were computed for each element. To reduce computational load, only one focus point was defined, which was collocated with the scatterer.

- For the plane wave, as for the focused transmission sequence, only one angle was used, corresponding to the angle used to position the scatterer.

2.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Full width at half-maximum (FWHM): Lateral distance (x-axis) when the profile amplitude drops to dB. FWHM assesses the resolution of the system, so the smaller the value, the better the performance.

- CR: Ratio of the average envelope amplitude in a volume of interest to the average envelope amplitude of the background. The volume of interest was defined as a cube of dimensions given by the FWHM, centered at the known scatterer position. The remaining reconstruction volume was set as background. CR is used to estimate the visibility of the targeted structure and is expected to be maximized for improved detectability.

- Peak sidelobe level (PSL): Amplitude of the largest sidelobe relative to the main lobe computed on the PSF x-axis profile. PSL offers insights into the apex intensity emanating from sidelobes, which is undesirable and therefore aimed to be minimized.

- Integrated sidelobe level (ISL): Ratio of integration over the sidelobe region with respect to the integration of the main lobe section of the PSF x-axis profile. High ISL reduces contrast, as it represents the total energy in the sidelobes with respect to the energy of the main beam.

2.3. Experimental Validation

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Method Validation

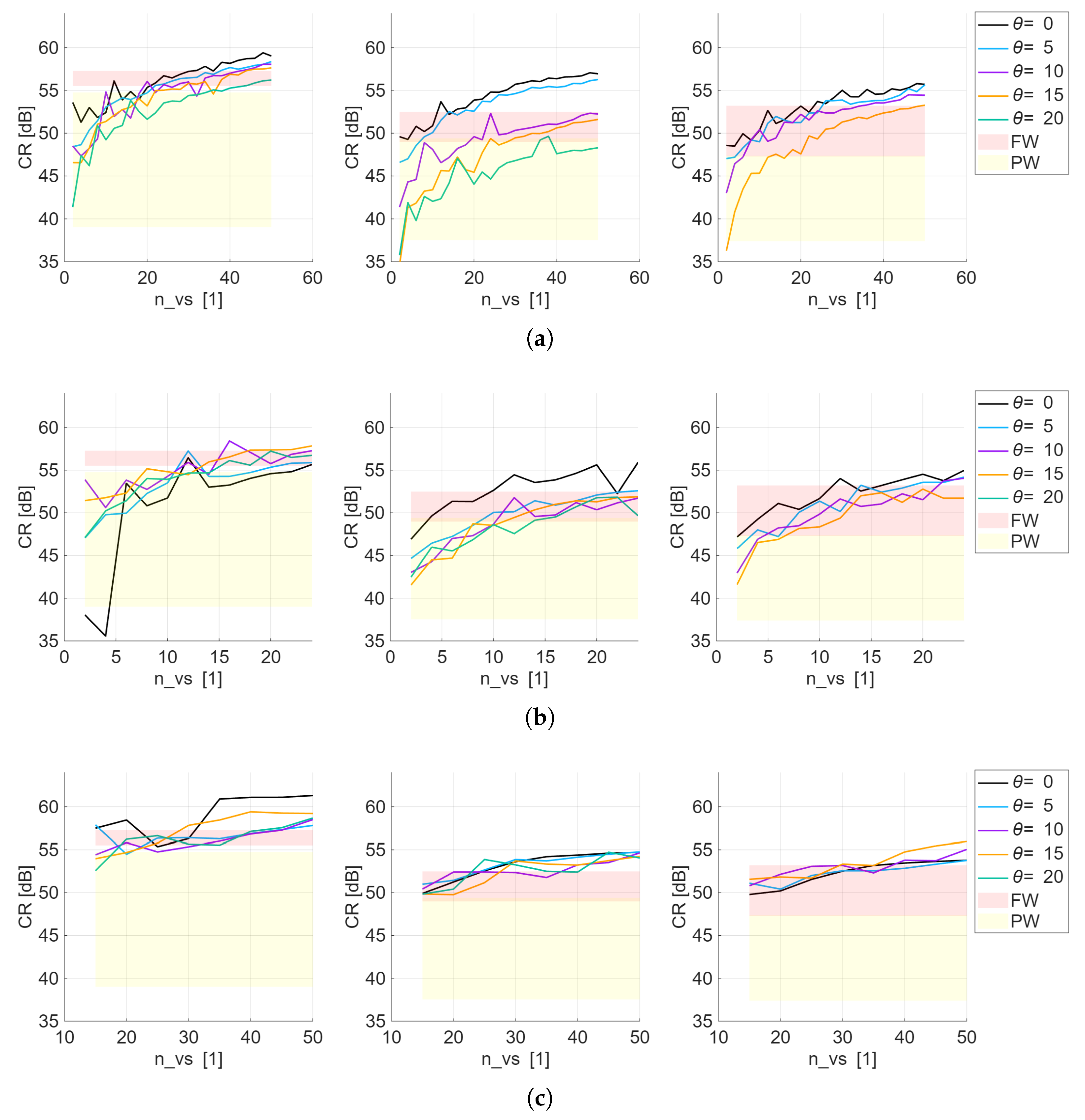

3.2. Transmission Sequence Design

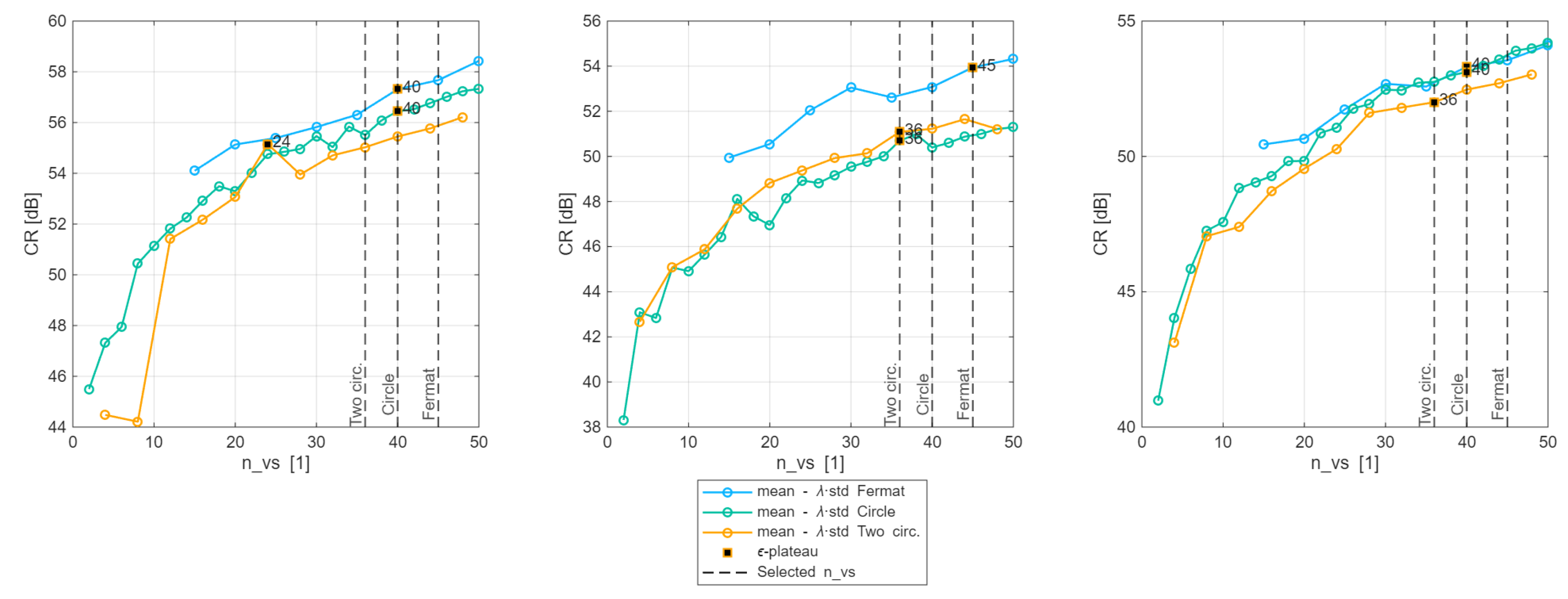

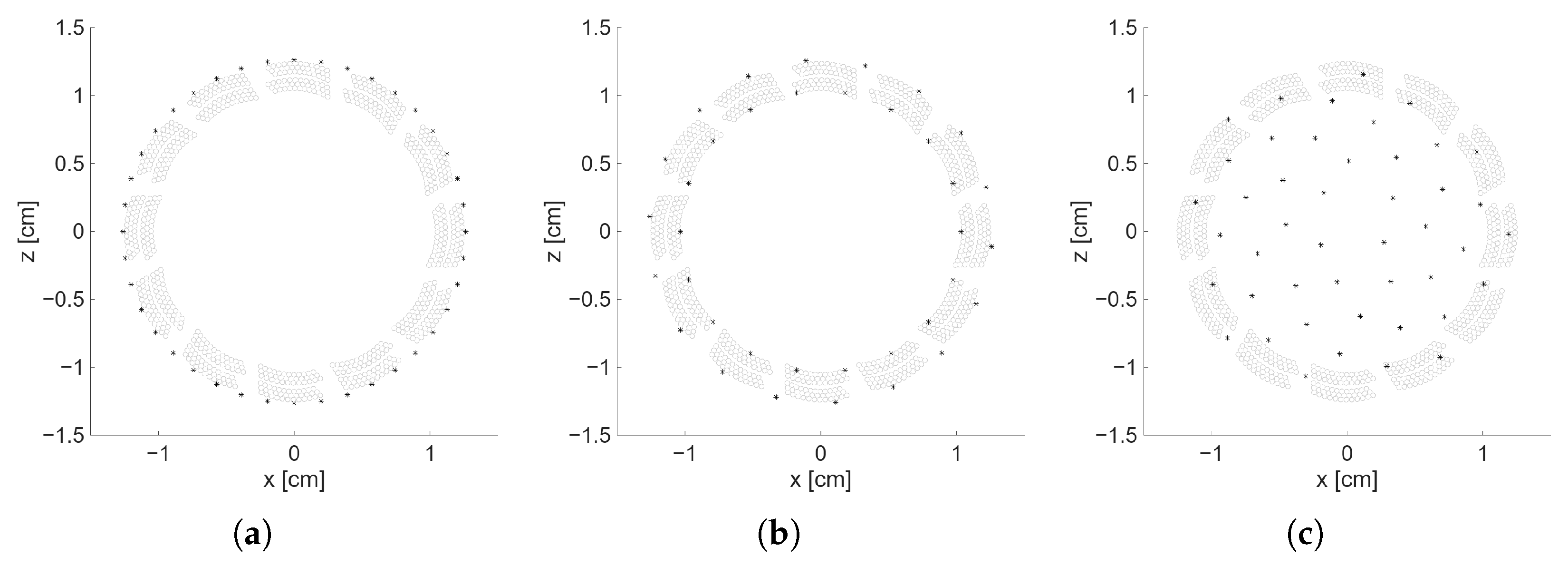

3.2.1. Selection of for Each VS Pattern

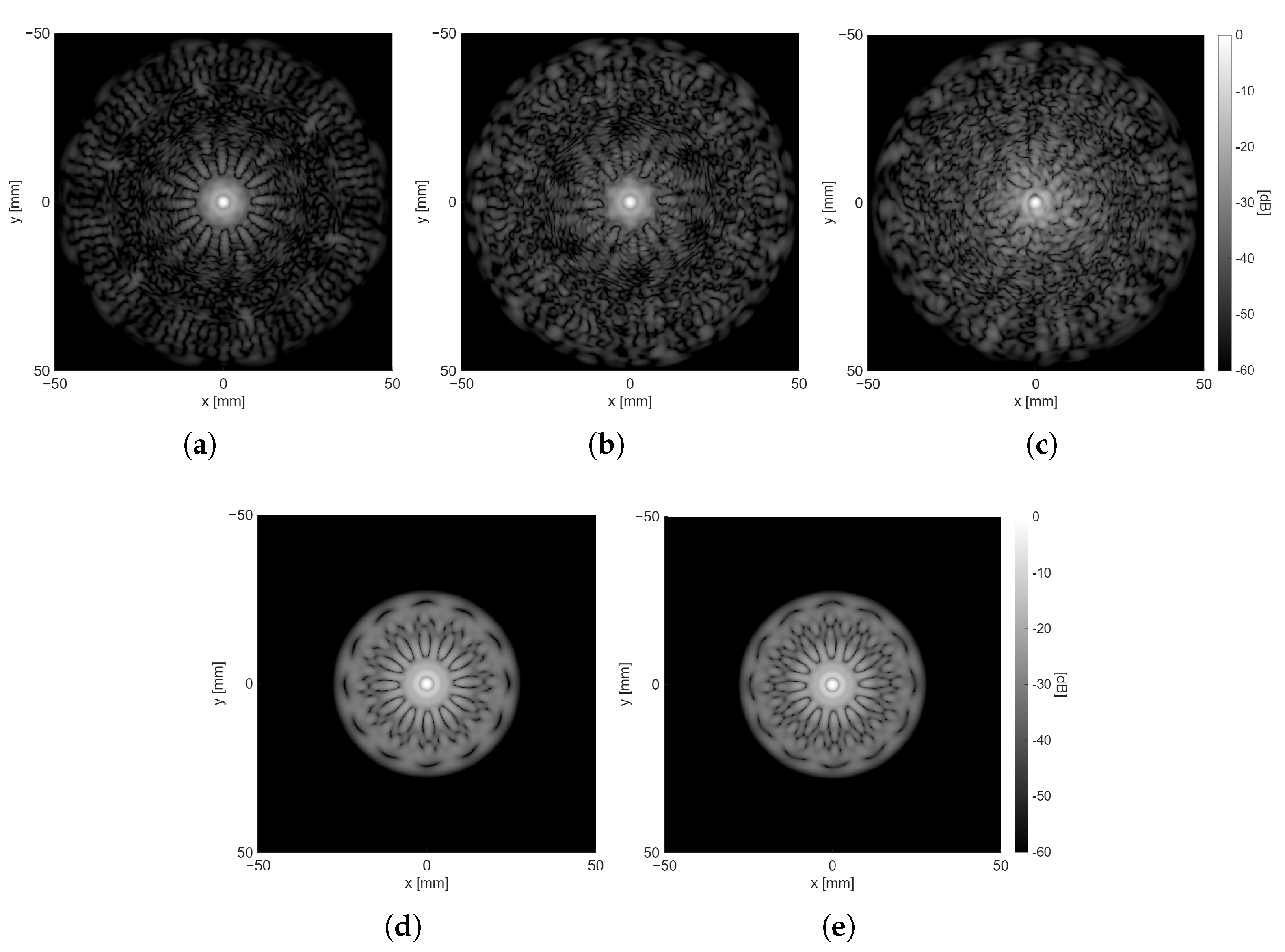

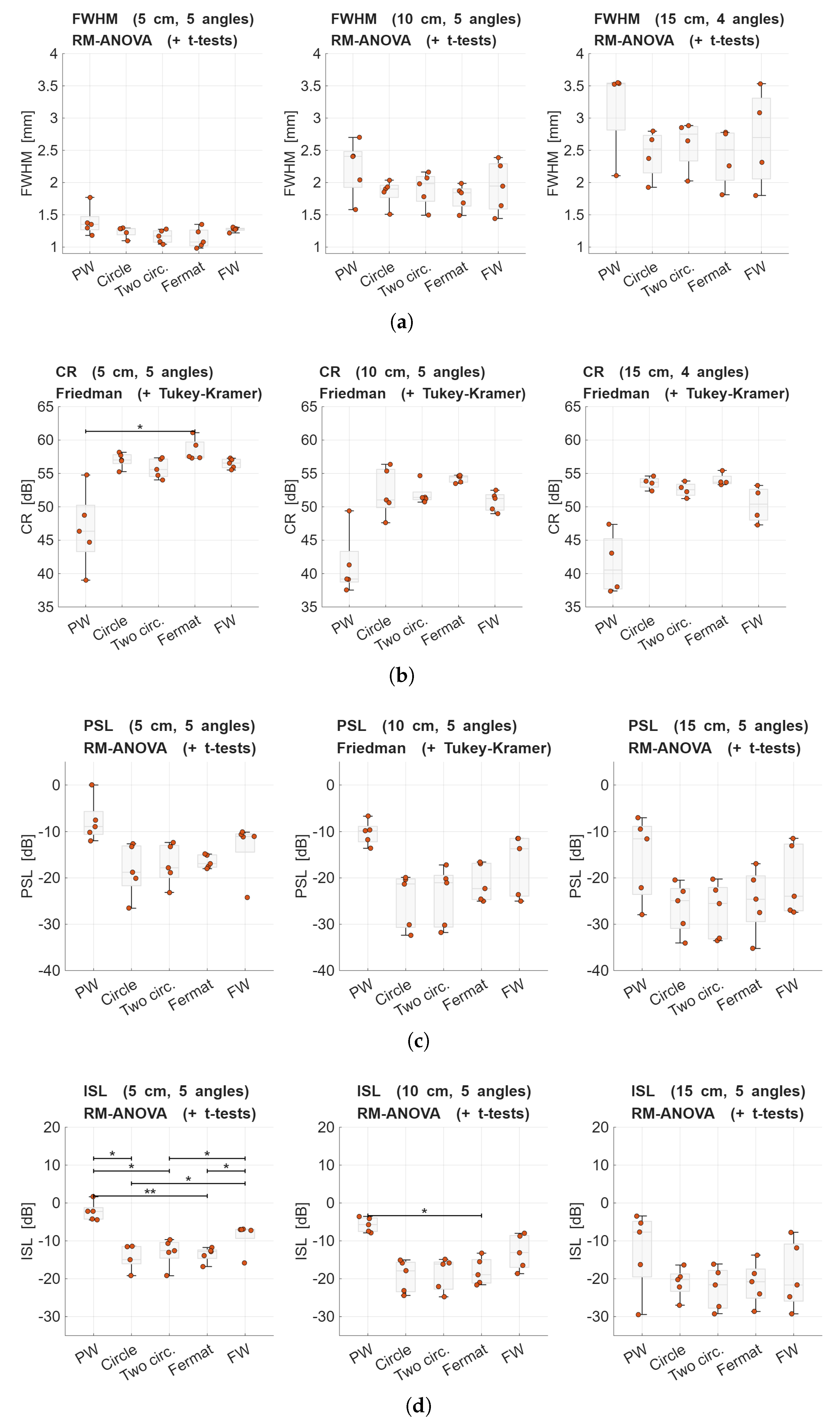

3.2.2. Performance Evaluation of Transmission Schemes

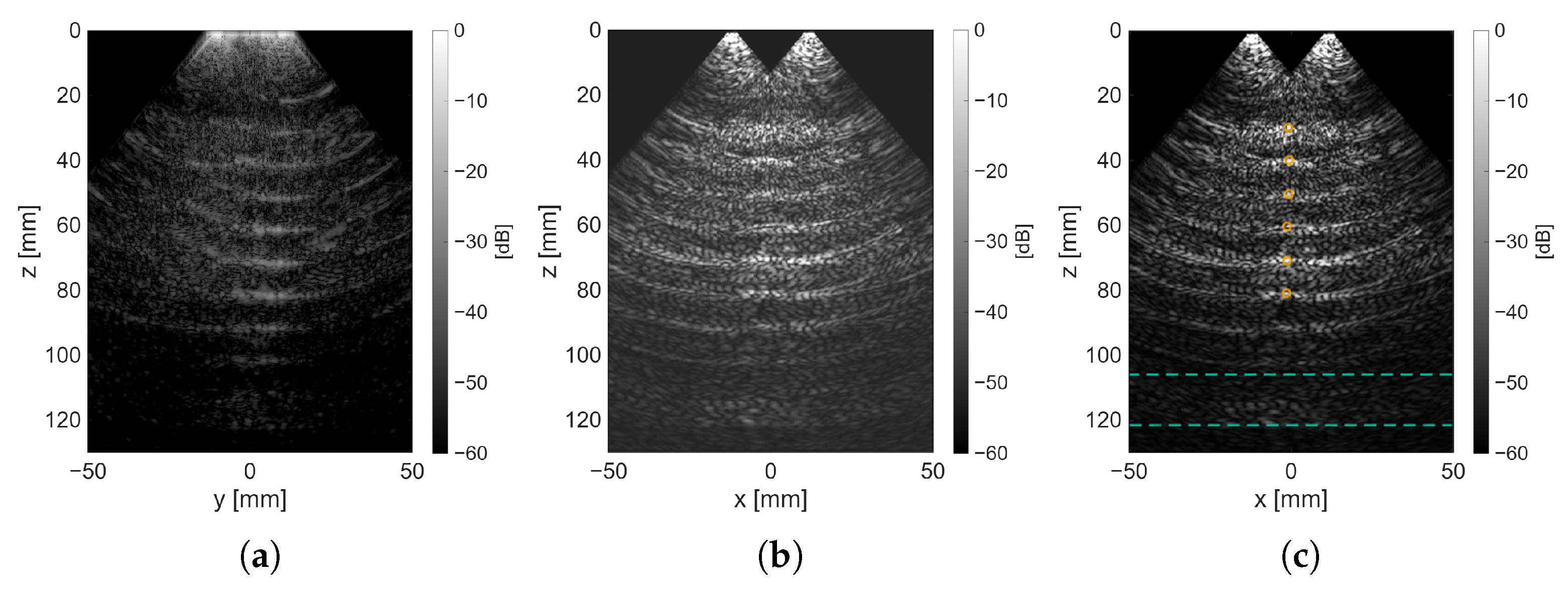

3.2.3. Evaluation of Experimental Data

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTG | Cardiotocography |

| CMUT | Capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer |

| DW | Diverging waves |

| VS | Virtual source |

| RSI | Rayleigh–Sommerfeld integral |

| PSF | Point spread function |

| CR | Contrast ratio |

| FWHM | Full width at half-maximum |

| PSL | Peak sidelobe level |

| ISL | Integrated sidelobe level |

| MIP | Maximum Intensity Projection |

Appendix A. Bessel of First Kind Piecewise Approximation

- Very small .Here already gives machine precision accuracy, avoiding divisions by very small numbers in the polynomial.

- Mid range .A polynomial expansion in odd powers of x is used,where the coefficients are chosen to match the Maclaurin series for up to .

- Large .The standard asymptotic form of the Bessel function is used:

Appendix B. Computation of

References

- Soma-Pillay, P.; Nelson-Piercy, C.; Tolppanen, H.; Mebazaa, A. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016, 27, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, W. Early-pregnancy maternal heart rate is related to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 268, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, U.S.P.S.T.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Barry, M.J.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W.; Kemper, A.R.; Krist, A.H.; et al. Screening for Preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2017, 317, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, E.R.; Bylsma-Howell, M.; Shamsi, S.; Towell, M.E. A scoring system for nonstressed antepartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1979, 133, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli, A.; Ferrario, M.; Piccini, L.; Andreoni, G.; Matrone, G.; Magenes, G.; Signorini, M.G. Prototype of a wearable system for remote fetal monitoring during pregnancy. In Proceedings of the 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 31 August–4 September 2010; pp. 5815–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Indications for outpatient antenatal fetal surveillance: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 828. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, e177–e197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffmann, T.; Silberman, M. Fetal Monitoring; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Newby, S.; Potluri, P.; Mirihanage, W.; Fernando, A. Emerging Paradigms in Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring: Evaluating the Efficacy and Application of Innovative Textile-Based Wearables. Sensors 2024, 24, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres-de Campos, D. Electronic fetal monitoring or cardiotocography, 50 years later: What’s in a name? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.R.; Peaceman, A.M. Identification, Assessment and Management of Fetal Compromise. Clin. Perinatol. 2012, 39, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelmann, P.; Vullings, R.; Kolen, A.F.; Bergmans, J.W.M.; van Laar, J.O.E.H.; Tortoli, P.; Mischi, M. Doppler Ultrasound Technology for Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring: A Review. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelect. Freq. Control. 2020, 67, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J. The Future of Fetal Monitoring. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 5, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wu, R.S.; Lin, M.; Xu, S. Emerging Wearable Ultrasound Technology. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2024, 71, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Huang, H.; Li, M.; Gao, X.; Yin, L.; Qi, R.; Wu, R.S.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, K.; et al. A wearable cardiac ultrasound imager. Nature 2023, 613, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Andre, M.; Chitnis, P.; Xu, S.; Croy, T.; Wear, K.; Sikdar, S. Clinical, Safety, and Engineering Perspectives on Wearable Ultrasound Technology: A Review. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2023, 71, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Makihata, M.; Liu, H.-C.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, X. Bioadhesive ultrasound for long-term continuous imaging of diverse organs. Science 2022, 377, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, K.-Y. Applications of Advanced Ultrasound Technology in Obstetrics. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, H.; Staudach, A.; Spitzer, D.; Schaffer, H. Three-dimensional ultrasound in obstetrics and gynaecology: Technique, possibilities and limitations. Hum. Reprod. 1994, 9, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, E.; Varray, F.; Petrusca, L.; Cachard, C.; Tortoli, P.; Liebgott, H. Experimental 3-D ultrasound imaging with 2-D sparse arrays using focused and diverging waves. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoop, H.; Vermeulen, M.; Schwab, H.M.; Lopata, R.G.P. Coherent Bistatic 3-D Ultrasound Imaging Using Two Sparse Matrix Arrays. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2023, 70, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, M.H.; Kaddoura, T.; Zemp, R.J. Costas Sparse 2-D Arrays for High-Resolution Ultrasound Imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2023, 70, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.A.; Schou, M.; Jørgensen, L.T.; Tomov, B.G.; Stuart, M.B.; Traberg, M.S.; Taghavi, I.; Øygaard, S.H.; Ommen, M.L.; Steenberg, K.; et al. Anatomic and Functional Imaging Using Row–Column Arrays. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2022, 69, 2722–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, S.I.; Yen, J.T. 3-D Spatial Compounding Using a Row-Column Array. Ultrason. Imaging 2009, 31, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Lok, U.W.; Dong, Z.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Song, P.; Chen, S. Enhancing Row-Column Array (RCA)-Based 3D Ultrasound Vascular Imaging With Spatial-Temporal Similarity Weighting. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2025, 44, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.; Lockwood, G. Theoretical assessment of a crossed electrode 2-D array for 3-D imaging. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Ultrasonics, Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–8 October 2003; pp. 968–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalli, A.; Boni, E.; Savoia, A.S.; Tortoli, P. Density-tapered spiral arrays for ultrasound 3-D imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2015, 62, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalli, A.; Boni, E.; Giangrossi, C.; Mattesini, P.; Dallai, A.; Liebgott, H.; Tortoli, P. Real-Time 3-D Spectral Doppler Analysis With a Sparse Spiral Array. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, H.J.; Boni, E.; Ramalli, A.; Piccardi, F.; Traversi, A.; Galeotti, D.; Noothout, E.C.; Daeichin, V.; Verweij, M.D.; Tortoli, P.; et al. Sparse Volumetric PZT Array with Density Tapering. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Kobe, Japan, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Graullera, O.; Martín, C.J.; Godoy, G.; Ullate, L.G. 2D array design based on Fermat spiral for ultrasound imaging. Ultrasonics 2010, 50, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, D.H.; Foster, F.S. Two-dimensional transducer arrays for medical ultrasound: Beamforming and imaging (Invited Paper). In Proceedings of the New Developments in Ultrasonic Transducers and Transducer Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 5 November 1992; pp. 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, B.; Robini, M.; Tortoli, P.; Cachard, C.; Liebgott, H. Design of Optimal 2-D Nongrid Sparse Arrays for Medical Ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 60, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, E.; Ramalli, A.; Tortoli, P.; Cachard, C.; Robini, M.C.; Liebgott, H. 2-D Ultrasound Sparse Arrays Multidepth Radiation Optimization Using Simulated Annealing and Spiral-Array Inspired Energy Functions. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2016, 63, 2138–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, S.H.C.; Chiu, T.; Fox, M.D. Ultrasound image enhancement: A review. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2012, 7, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, B.; Thittai, A.K. Diverging beam transmit through limited aperture: A method to reduce ultrasound system complexity and yet obtain better image quality at higher frame rates. Ultrasonics 2019, 91, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaldo, G.; Tanter, M.; Bercoff, J.; Benech, N.; Fink, M. Coherent plane-wave compounding for very high frame rate ultrasonography and transient elastography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2009, 56, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H.; Kanai, H. High-frame-rate echocardiography using diverging transmit beams and parallel receive beamforming. J. Med. Ultrason. 2011, 38, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, H.; Petterson, N.J.; van de Vosse, F.N.; van Sambeek, M.R.H.M.; Schwab, H.M.; Lopata, R.G.P. Multiperspective Ultrasound Strain Imaging of the Abdominal Aorta. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 3714–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadacci, C.; Pernot, M.; Couade, M.; Fink, M.; Tanter, M. High-contrast ultrafast imaging of the heart. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2014, 61, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schaijk, R.; in ’t Zandt, M.; Robaeys, P.; Slotboom, M.; Klootwijk, J.; Bekkers, P. Reliability of collapse mode CMUT. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 3–8 September 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herickhoff, C.D.; van Schaijk, R. cMUT technology developments. Z. Fur Med. Phys. 2023, 33, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.A. Field: A Program for Simulating Ultrasound Systems: 10th Nordic-Baltic Conference on Biomedical Imaging. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1997, 34, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.A. Users’ Guide for the Field II Program. 3.30 ed; Technical University of Denmark: Lyngby, Denmark, 2001; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- McGough, R.J. Rapid calculations of time-harmonic nearfield pressures produced by rectangular pistons. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 115, 1934–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigier, A.; Varray, F.; Garcia, D. SIMUS: An open-source simulator for medical ultrasound imaging. Part II: Comparison with four simulators. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 220, 106774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeby, B.E.; Cox, B.T. k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010, 15, 021314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encino, K.; Panduro, M.A.; Reyna, A.; Covarrubias, D.H. Novel Design Techniques for the Fermat Spiral in Antenna Arrays, for Maximum SLL Reduction. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions: With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 1965; Chapter 9; pp. 355–434. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. Fast and Accurate Bessel Function Computation. In Proceedings of the 2009 19th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, Portland, OR, USA, 8–10 June 2009; pp. 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, T.L. Array Beamforming. In Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging: Inside Out; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; pp. 209–255. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Wafer level | ||

| Bias voltage | 35 | V |

| Max. voltage (bias + RF) | 55 | V |

| Acoustical characterization | ||

| Center frequency | 2.7 | MHz |

| Fractional bandwidth * | 116 | % |

| Max. pressure † | 1.4 | MPa |

| Sensitivity | 3.4 | MPa/100V RF |

| Piston Width (a) Relative to | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

|---|---|

| 0.089 | |

| 0.022 | |

| 0.012 | |

| 0.008 | |

| 0.003 | |

| 0.002 |

| Pattern | at -plateau, cm | Selected |

|---|---|---|

| Circumference | [40, 36, 40] | 40 |

| Two concentric circ. | [24, 36, 36] | 36 |

| Fermat’s spiral | [40, 45, 40] | 45 |

| Depth | Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| FWHM | ||

| 5 cm | RM-ANOVA | |

| 10 cm | RM-ANOVA | |

| 15 cm | RM-ANOVA | 0.002 |

| CR | ||

| 5 cm | Friedman | 0.009 |

| 10 cm | Friedman | 0.028 |

| 15 cm | Friedman | 0.029 |

| PSL | ||

| 5 cm | RM-ANOVA | |

| 10 cm | Friedman | 0.014 |

| 15 cm | RM-ANOVA | 0.001 |

| ISL | ||

| 5 cm | RM-ANOVA | |

| 10 cm | RM-ANOVA | |

| 15 cm | RM-ANOVA | 0.002 |

| Depth (z) [mm] | FWHM [mm] | CR [dB] |

|---|---|---|

| 29.91 | 1.51 | 15.57 |

| 39.87 | 6.31 | 16.92 |

| 50.30 | 6.21 | 14.19 |

| 60.26 | 2.50 | 15.39 |

| 70.84 | 6.44 | 17.26 |

| 80.80 | - | 14.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almario Escorcia, M.J.; Gholampour, A.; van Schaijk, R.; de Wijs, W.-J.; Immink, A.; Henneken, V.; Lopata, R.; Schwab, H.-M. An Annular CMUT Array and Acquisition Strategy for Continuous Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 6637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216637

Almario Escorcia MJ, Gholampour A, van Schaijk R, de Wijs W-J, Immink A, Henneken V, Lopata R, Schwab H-M. An Annular CMUT Array and Acquisition Strategy for Continuous Monitoring. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216637

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmario Escorcia, María José, Amir Gholampour, Rob van Schaijk, Willem-Jan de Wijs, Andre Immink, Vincent Henneken, Richard Lopata, and Hans-Martin Schwab. 2025. "An Annular CMUT Array and Acquisition Strategy for Continuous Monitoring" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216637

APA StyleAlmario Escorcia, M. J., Gholampour, A., van Schaijk, R., de Wijs, W.-J., Immink, A., Henneken, V., Lopata, R., & Schwab, H.-M. (2025). An Annular CMUT Array and Acquisition Strategy for Continuous Monitoring. Sensors, 25(21), 6637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216637