An Angle-Dependent Bias Compensation Method for Hemispherical Resonator Gyro Inertial Navigation Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Introduction of harmonic errors in the HRG-based INS and establishment of the relationship between harmonic bias errors and temperature (frequency).

- (2)

- Development of a novel error model for the hemispherical resonator gyro that incorporates harmonic bias errors and their temperature coefficients.

- (3)

- Design of a new Kalman filter for system-level calibration of the HRG-based INS according to the proposed error model.

2. Error Model

2.1. Definition of Reference Frames

- (1)

- The inertial coordinate system (i-frame) has its origin at the center of the Earth, with axes non-rotating relative to the celestial sphere. The three axes are defined as , forming a right-handed coordinate system, where the is aligned with the Earth’s polar axis.

- (2)

- The navigation coordinate system (n-frame) has its origin at the position of the vehicle. Its axes are aligned with the directions of North (N), East (E), and Down (D). Navigation computations are typically performed in the n-frame.

- (3)

- The body coordinate system (b-frame) has its origin at the center of mass of the vehicle. Its axes are aligned with the vehicle’s pitch axis, roll axis, and yaw axis, pointing toward the right, forward, and upward directions of the vehicle’s motion, respectively.

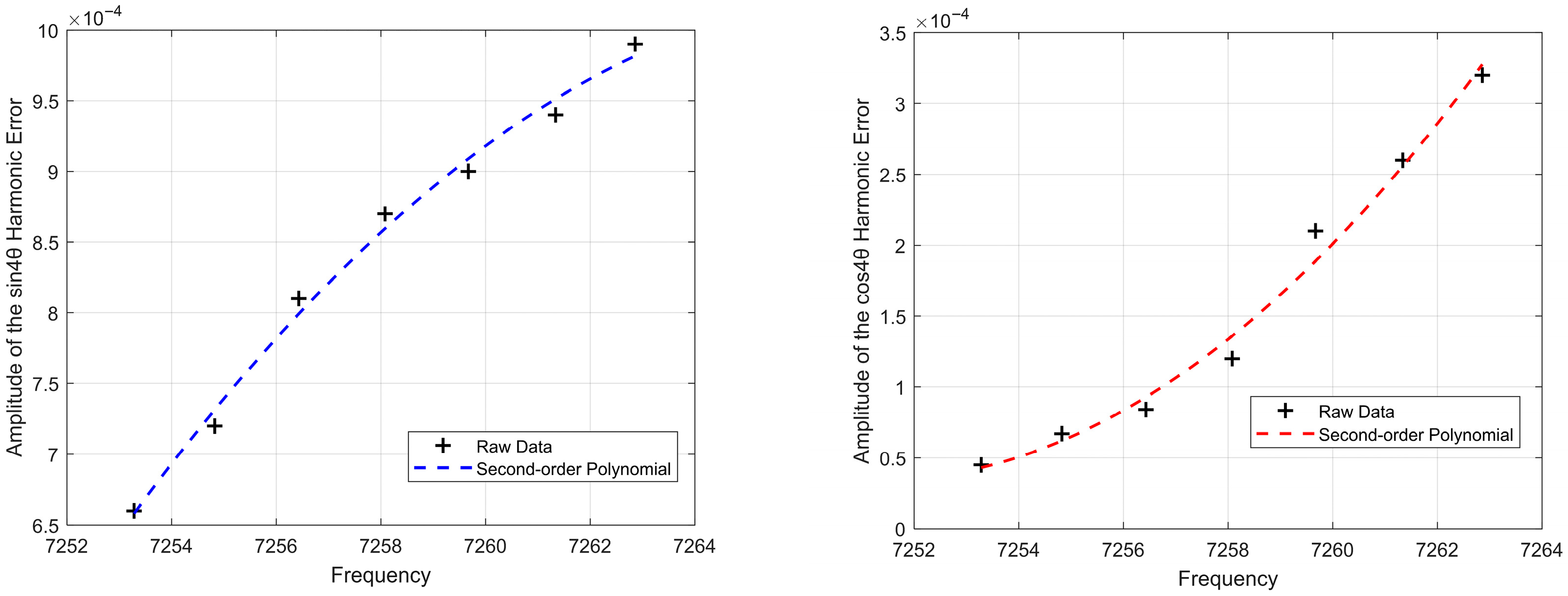

2.2. Relationship Between Harmonic Error and Temperature

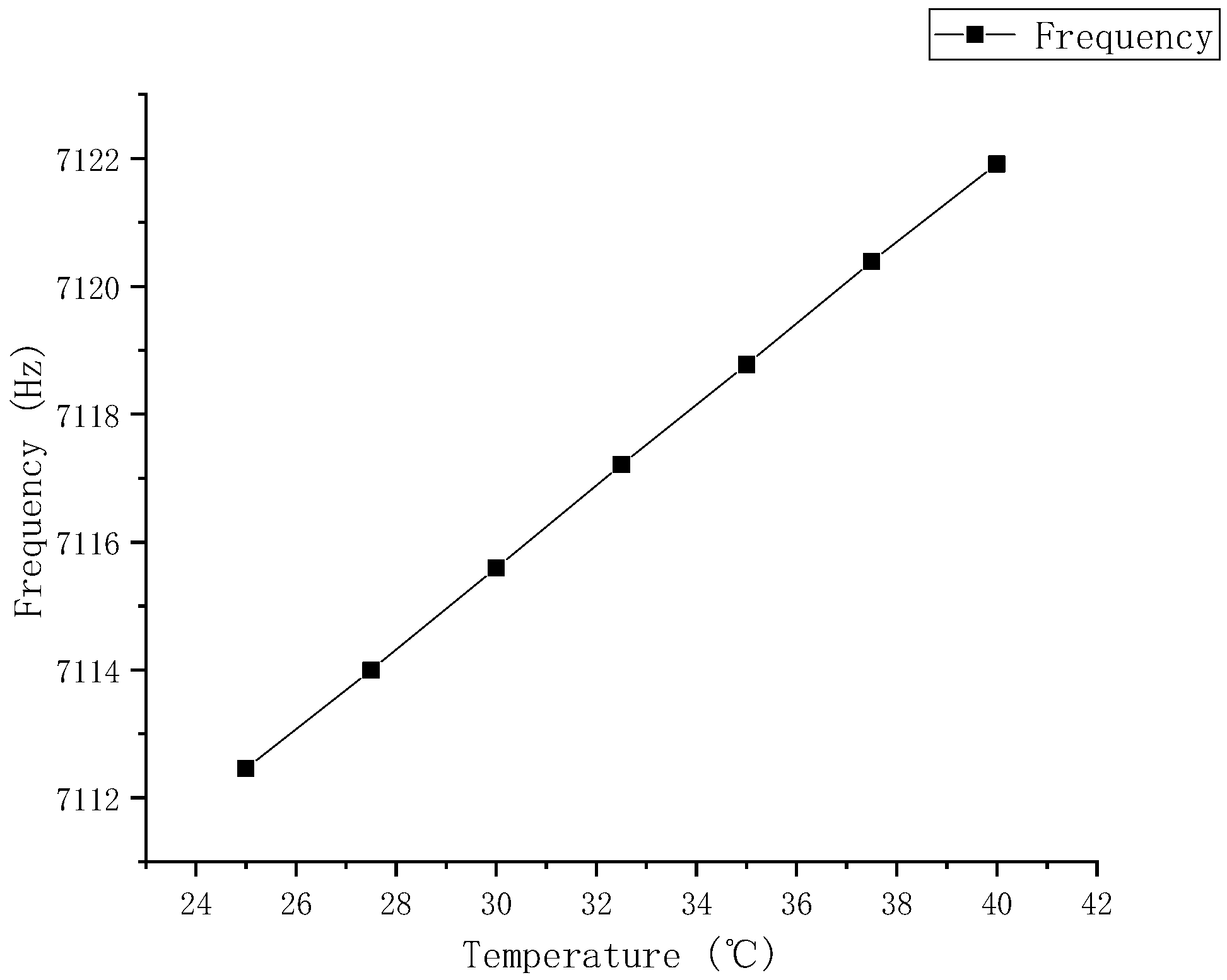

2.3. Relationship Between Temperature and Resonant Frequency

2.4. Temperature (Frequency)-Dependent Harmonic Bias Error Model

2.5. IMU Error Model

2.5.1. Hemispherical Resonator Gyro Error Model

- Bias Error

- Scale Factor Error

- Installation Error

2.5.2. Accelerometer Error Model

- Bias Error

- Scale Factor Error

- Installation Error

2.6. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Error Equations

- Attitude Error Equations

- Velocity Error Equations

- Position Error Equations

3. System-Level Calibration Kalman Filter

3.1. Construction of a 48-D Kalman Filter

3.2. Calibration Path and Observability

4. System-Level Calibration Experiments and Navigation Experiments

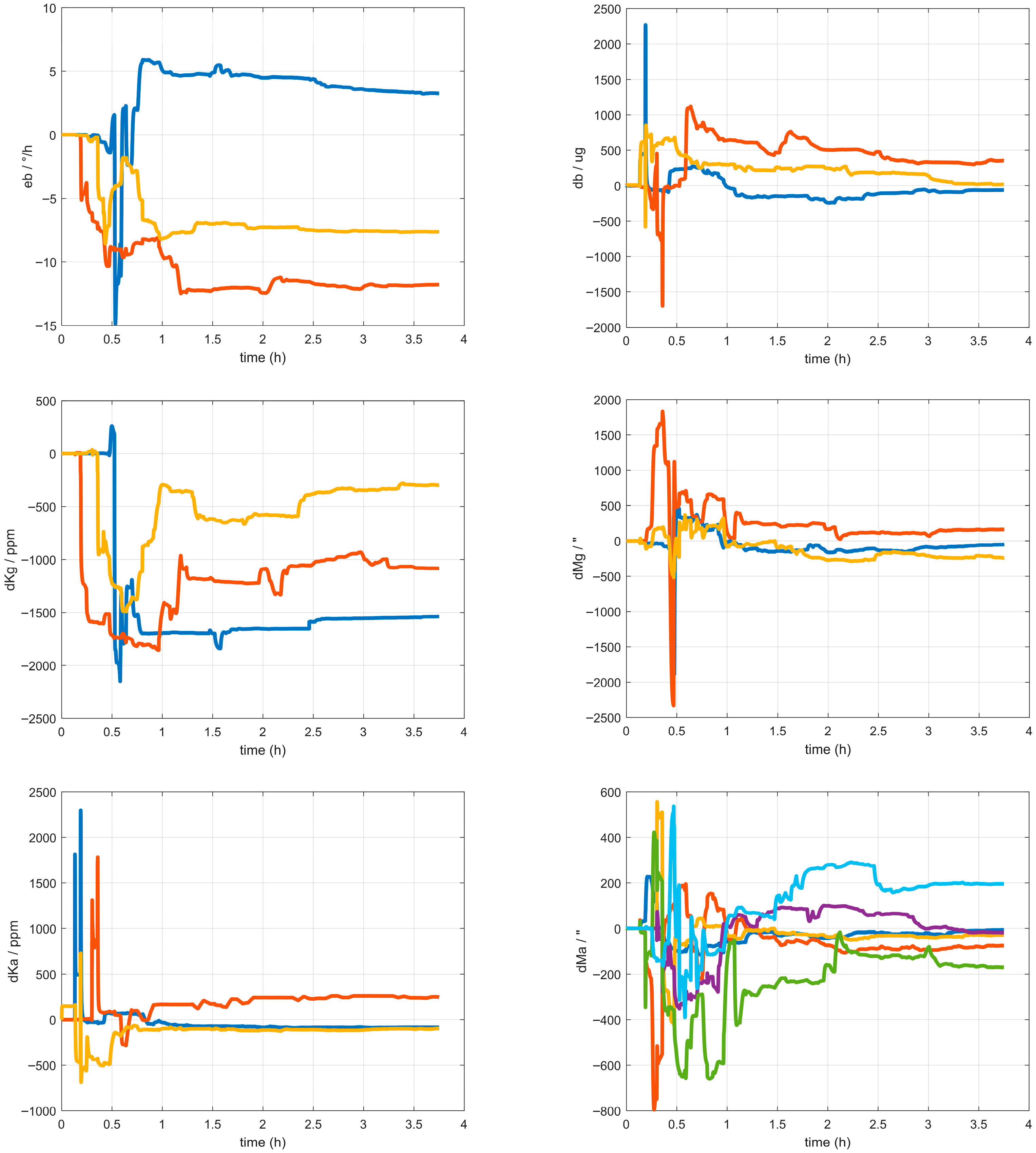

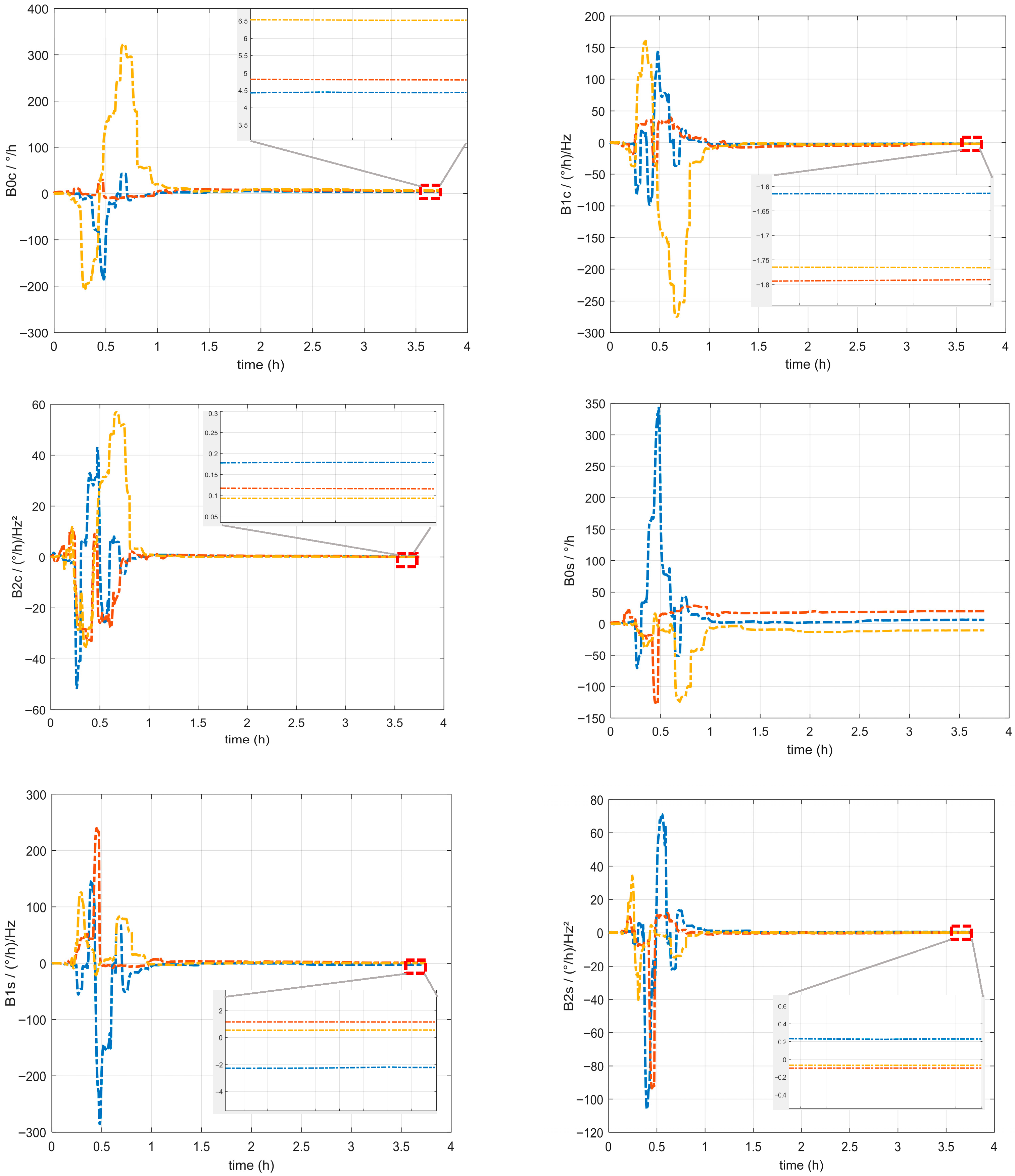

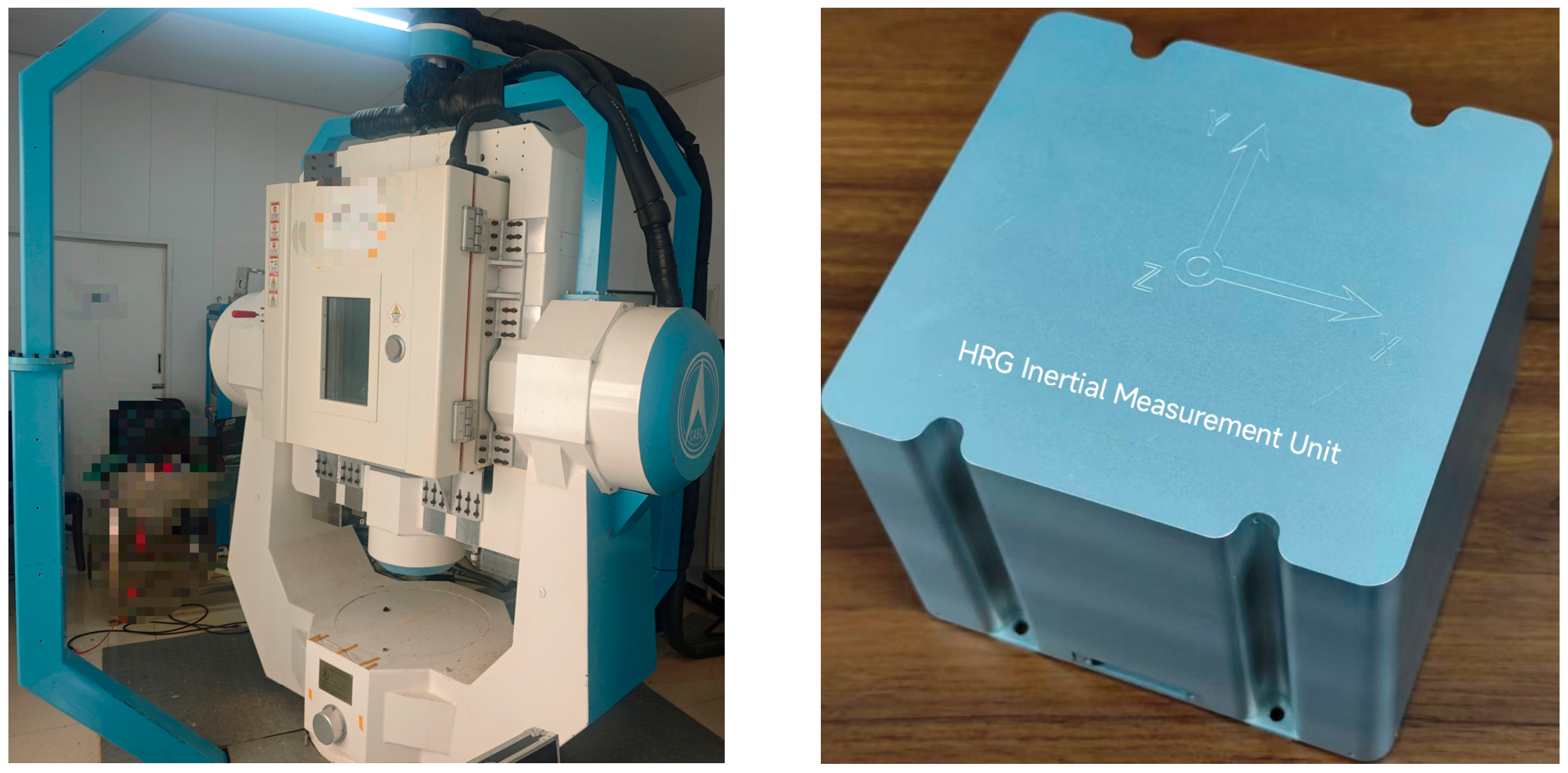

4.1. System-Level Calibration Experiments

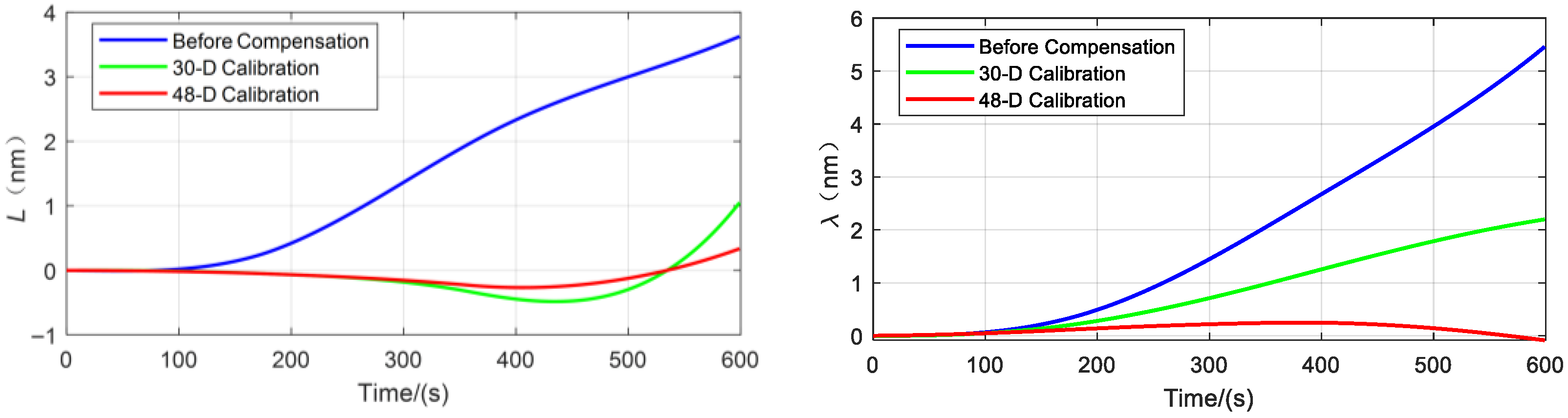

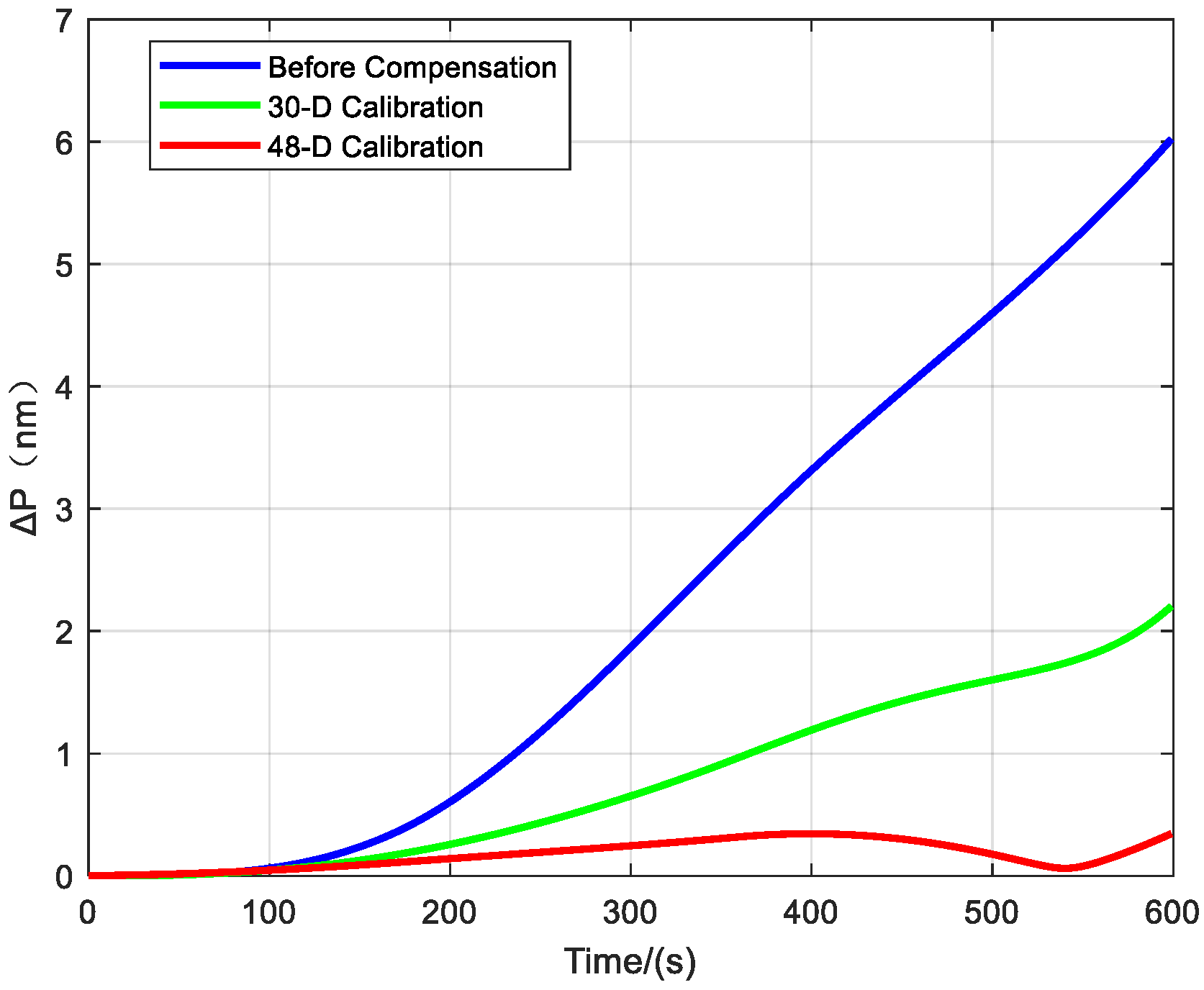

4.2. Navigation Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryan, G.H. On the beats in the vibrations of a revolving cylinder or bell. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1890, 7, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rozelle, D.M. The hemispherical resonator gyro: From wineglass to the planets. Adv. Astronaut. Sci. 2009, 134, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Rozelle, D. Milli-HRG inertial navigation system. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Myrtle Beach, SC, USA, 23–26 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Delhaye, F.; De Leprevier, C. SkyNaute by Safran—How the HRG technological breakthrough benefits to a disruptive IRS (Inertial Reference System) for commercial aircraft. In Proceedings of the 2019 DGON Inertial Sensors and Systems (ISS), Braunschweig, Germany, 10–11 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chikovani, V.V.; Golovach, S. Rate vibratory gyroscopes bias minimization by the standing wave angle installation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 40th International Conference on Electronics and Nanotechnology (ELNANO), Kyiv, Ukraine, 22–24 April 2020; pp. 706–709. [Google Scholar]

- Chikovani, V.V.; Holovach, S.; Strokach, H.; Avrutov, V. The development features and design of a vibratory gyroscope with a metallic cylindrical resonator. Eng. Trans. 2025, 73, 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.C.; Yan, L.H.; Jiang, C.Q.; Fang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Fang, H.B. Application and implementation of Cordic algorithm in hemispherical gyro. Piezoelectr. Acoustoopt. 2016, 38, 934–937. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L. Process Optimization and Structural Testing of Micro Hemispherical Resonator Gyroscope. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2018; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.Y. Error Analysis and Testing Technology of Hemispherical Resonator Gyro. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2009; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Peng, H.; Fang, Z.; Zhou, B.Q. Design of digital control loop for hemispherical resonator gyro in force balance mode. Piezoelectr. Acoustoopt. 2015, 37, 899–903. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Cui, Y.T.; Wang, Y.Y.; Jiang, X.X. Analysis of vacuum requirement for hemispherical resonator gyro. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 2020, 28, 510–514. [Google Scholar]

- Klimov, D.M.; Zhuravlev, V.F.; Zhbanov, Y.K. Quartz Hemispherical Resonator (Wave Solid-State Gyroscope); Kim L.A.: Moscow, Russia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q.; Teng, L.; Yue, Y.Z.; Cao, S.Y.; Zhu, L.J.; Meng, B. Design and parameter optimization of hemispherical resonator with variable wall thickness. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 2020, 28, 789–793. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Q.; Ding, X.K.; Chen, H.; Jia, J.; Li, H.S. Calculation method of modal principal axis azimuth for micro hemispherical resonator gyro. Transducer Microsyst. Technol. 2021, 40, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Camberlein, L.; Mazzanti, F. Calibration technique for laser gyro strapdown inertial navigation systems. In Proceedings of the Symposium Gyro Technology, Stuttgart, Germany, 24–25 September 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.H. Research on System-Level Calibration and Alignment Methods for Laser Gyro Inertial Measurement Units. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.Y.; Tang, J.X.; Han, S.L.; Yuan, B.L. System-level calibration method for laser gyro SINS based on 36-dimensional Kalman filter. Hongwai Yu Jiguang Gongcheng/Infrared Laser Eng. 2015, 44, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H.N.; Hu, X.M.; Pei, Z.; Chen, X.; Yang, J.L. A novel temperature error compensation method for accelerometers. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 2009, 17, 479–482. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.F. Research on Dithered Ring Laser Gyro Strapdown Inertial Navigation System and Its Real-Time Temperature Compensation Method. Master’s Thesis, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.B.; Zhang, S.F.; Cai, H. Modeling method for gyro temperature drift based on cross-validation. J. Astronaut. 2007, 28, 589–593. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G. Research on Key Technologies of Dual-Axis Rotating Inertial Navigation System with Dithered Ring Laser Gyro. Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Tian, W.; Jin, Z.; Qian, L. Temperature drift modelling and compensation for a dynamically tuned gyroscope by combining WT and SVM method. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, W.Q.; Lian, J.X. Calibration method for temperature model parameters of accelerometer assembly under cold start. J. Chin. Inert. Technol. 2011, 19, 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, J. Multi-position continuous rotate-stop fast temperature parameters estimation method of flexible pendulum accelerometer triads. Measurement 2021, 169, 108372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Q.X.; Li, D.; Li, H.P.; Liu, C.; Lan, T.; Tan, Z.; Yu, X. A system-level calibration method for INS: Simultaneous compensation of accelerometer asymmetric errors and second-order temperature-related errors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Qiao, X.W.; Chen, Z.H.; Liang, A.Q.; Wang, L.; Shi, Q. Research on temperature compensation technology for hemispherical resonator gyro inertial navigation system. Navig. Control 2023, 22, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.T.; Ban, J.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Wang, S.L.; Xia, X. Temperature compensation method for hemispherical resonator gyro in INS based on PSO algorithm. Navig. Position. Timing 2023, 10, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Loper, E.J.; Lynch, D.D.; Stevenson, K.M. Projected performance of smaller hemispherical resonator gyros. In Proceedings of the IEEE Position Location and Navigation Symposium, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–7 November 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wu, W.Q.; Fang, Z.; Luo, B.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Q.G. Temperature drift compensation for hemispherical resonator gyro based on natural frequency. Sensors 2012, 12, 6434–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Sun, W.; Gao, Y. MEMS IMU error mitigation using rotation modulation technique. Sensors 2016, 16, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.G. Research on initial alignment and self-calibration of rotary strapdown inertial navigation systems. Sensors 2015, 15, 3154–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Y.; Zha, F.; Li, F.; Wei, Q.S. A combination scheme of pure strapdown and dual-axis rotation inertial navigation systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Position | Rank | Position | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 11 | 48 |

| 2 | 18 | 12 | 48 |

| 3 | 24 | 13 | 48 |

| 4 | 30 | 14 | 48 |

| 5 | 36 | 15 | 48 |

| 6 | 39 | 16 | 48 |

| 7 | 42 | 17 | 48 |

| 8 | 45 | 18 | 48 |

| 9 | 47 | 19 | 48 |

| 10 | 48 |

| Error Terms | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| (°/h) | 3.25 | −11.79 | −7.62 |

| (μg) | −62.39 | 350.38 | 18.69 |

| (ppm) | −1538 | −1083 | −297 |

| (ppm) | −84.09 | 247.74 | −97.24 |

| (°/h) | 4.43 | 4.79 | 6.52 |

| ((°/h)/Hz) | −1.61 | −1.79 | −1.77 |

| ((°/h)/Hz2) | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| (°/h) | 5.93 | 19.54 | −10.59 |

| ((°/h)/Hz) | −2.21 | 1.15 | 0.55 |

| ((°/h)/Hz2) | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| : −49.71 | : 160.14 | : −24.28 | |

| : −6.68 | : −173.87 | : −28.02 | |

| : −17.63 | : −69.96 | : 195.84 |

| Schemes | Maximum Radial Error | 50% CEP |

|---|---|---|

| Before Compensation | 6.02 nm | 1.86 nm |

| 30-D | 2.2 nm | 0.65 nm |

| 48-D | 0.34 nm | 0.17 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Lou, Q.; Li, D.; Li, H.; Lan, T.; Wu, Y.; Meng, H.; Li, J.; Xia, T.; Yu, X. An Angle-Dependent Bias Compensation Method for Hemispherical Resonator Gyro Inertial Navigation Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216639

Liu C, Lou Q, Li D, Li H, Lan T, Wu Y, Meng H, Li J, Xia T, Yu X. An Angle-Dependent Bias Compensation Method for Hemispherical Resonator Gyro Inertial Navigation Systems. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216639

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Chao, Qixin Lou, Ding Li, Huiping Li, Tian Lan, Yutao Wu, Hongjie Meng, Jingyu Li, Tao Xia, and Xudong Yu. 2025. "An Angle-Dependent Bias Compensation Method for Hemispherical Resonator Gyro Inertial Navigation Systems" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216639

APA StyleLiu, C., Lou, Q., Li, D., Li, H., Lan, T., Wu, Y., Meng, H., Li, J., Xia, T., & Yu, X. (2025). An Angle-Dependent Bias Compensation Method for Hemispherical Resonator Gyro Inertial Navigation Systems. Sensors, 25(21), 6639. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216639