1. Introduction

The rapid transition toward carbon neutrality and the large-scale integration of renewable energy sources are reshaping the structure and operation of modern power systems. Variable wind and photovoltaic (PV) generation introduce strong volatility and uncertainty, significantly increasing the requirements for system flexibility, reliability, and economic performance. At the same time, conventional thermal power and hydropower remain indispensable for balancing supply and demand. Consequently, developing optimization-based scheduling methods that can coordinate multiple heterogeneous resources under uncertainty and nonlinearity has become a critical research direction.

Optimization-based scheduling has been widely studied as an effective approach to coordinate multi-type power sources and address the challenges of system flexibility, renewable integration, and operational efficiency. References [

1,

2] establish coordinated planning frameworks that exploit demand response and nodal carbon potential to jointly optimize economic and environmental objectives. In [

3], the flexible retrofitting of thermal power units combined with energy storage deployment is investigated, where the benefits of peak shaving and renewable accommodation are quantitatively evaluated. Reference [

4] introduces a source–load cooperative peak-shaving mechanism that reduces curtailment and improves the efficiency of renewable energy utilization. Reference [

5] proposes an improved day-ahead scheduling strategy that incorporates DC frequency support to enhance renewable accommodation and peak-shaving performance in interconnected grids. Building on day-ahead models, Reference [

6] develops a combined day-ahead and intraday framework, where rolling optimization is used to reduce fluctuations and improve stability. Reference [

7] further introduces a real-time scheduling method based on dynamic decision-making, enabling continuous adjustment of system operating points to address unpredictable power flow deviations.

With the growing share of renewable energy, the variability and intermittency of wind and PV generation have introduced significant uncertainty into power system scheduling. Such uncertainty directly affects the balance of supply and demand, as well as system security and economic efficiency. Consequently, uncertainty modeling has become an essential component of modern scheduling research. Distributionally robust and data-driven scheduling approaches have been applied to improve system resilience against renewable volatility [

8,

9]. For instance, robust two-stage dispatch methods have been developed for wind–thermal coordination [

10], while chance-constrained formulations have been extended to integrated electricity–gas systems [

11]. Further, interval optimization [

12] and probabilistic admissibility assessment [

13] have been proposed to balance modeling fidelity and tractability. These methods demonstrate the importance of explicitly addressing uncertainty, yet they often rely on simplified linear models that may not adequately capture the nonlinear dynamics of hydropower and other flexible units. This creates a critical research gap, i.e., while uncertainty-aware methods have advanced considerably in modeling renewable variability, the flexible resources used to balance this variability—particularly hydropower—are typically represented through aggregated or linearized approximations that ignore essential physical constraints. Such simplifications may lead to suboptimal or infeasible scheduling solutions when detailed operational requirements must be satisfied in practice.

To cope with renewable uncertainty, the regulation capability of hydropower has been gradually incorporated into dispatch models. Owing to its fast response and large storage capacity, hydropower can provide both short-term balancing and long-term flexibility, making it an indispensable resource for enhancing system stability and accommodating variable renewable energy. Recent research has extensively examined the role of hydropower in complementary scheduling frameworks. Reference [

14] develops a short-term scheduling model for the hydropower station and evaluates its performance under multiple operating scenarios. In [

15], a bi-objective optimization model is constructed to maximize hydropower generation while simultaneously smoothing output fluctuations. Reference [

16] investigates two scheduling strategies, one minimizing total output volatility and the other enhancing overall stability. Adaptive operating rules that link short- and long-term scheduling horizons are proposed in [

17], highlighting the need to balance hydropower flexibility with renewable variability. To address the stochastic nature of renewable generation, Reference [

18] applies a probabilistic collocation method based on polynomial chaos expansion, thereby supporting the secure operation of cascade hydropower systems. Reference [

19] embeds short-term fluctuation risks into a mid- to long-term optimization framework, improving the robustness of hydropower scheduling decisions. Furthermore, Reference [

20] emphasizes water-use efficiency by formulating a short-term cascade hydropower optimization model with the objective of minimizing water consumption.

Although hydropower has been increasingly incorporated into scheduling models, most existing studies treat its operation in a simplified manner, often using linear approximations or fixed efficiency factors. In reality, hydropower scheduling is characterized by multiple nonlinear relationships, such as the water level–storage curve, the tail water level–discharge function, and the nonlinear mapping between water head, discharge, and power output. Additional complexities arise from operating constraints, including vibration zone avoidance, output fluctuation limits, and head loss effects, all of which directly influence the feasible operating space. Ignoring or oversimplifying these nonlinear characteristics not only reduces the accuracy of hydropower representation but may also lead to suboptimal or even infeasible scheduling outcomes in practical applications. Therefore, there exists a significant gap between uncertainty-aware scheduling frameworks and detailed physical modeling of flexible resources, hindering the development of truly practical and reliable multi-source coordination strategies.

In recent years, considerable efforts have been devoted to addressing the nonlinear nature of scheduling models, and a variety of approximation and reformulation techniques have been proposed [

21,

22]. Frequency-related nonlinear indices such as nadir and RoCoF are commonly embedded into dispatch through piecewise linearization, which transforms inherently nonlinear expressions into tractable mixed-integer linear forms [

23,

24]. To cope with complex nonlinear coupling between renewable generation and system inertia, synthetic inertia from inverter-based resources has been modeled with linearized approximations [

25]. Decomposition methods have also been developed to separate nonlinear multi-area or multi-timescale problems into smaller subproblems, improving tractability while retaining the essential nonlinear relationships [

26]. Convex relaxation techniques have been applied to replace nonconvex constraints with equivalent convex envelopes, thereby accelerating the solution of large-scale nonlinear scheduling problems [

27]. In addition, unit commitment formulations considering nonlinear dynamic responses have been approximated through bi-level or linearized models [

28], and multi-area frequency-constrained scheduling has been reformulated with linear surrogates to handle otherwise intractable nonlinear dynamics.

However, these linearized methods cannot be directly applied to hydropower scheduling, since its nonlinearities stem from water level–storage and tail water level–discharge relationships, as well as the bilinear dependence of head, discharge, and power output. Additional constraints such as vibration zones and head loss make the problem more complex, requiring dedicated modeling approaches beyond conventional linearization or relaxation techniques.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes an optimization-based scheduling method that coordinates hydropower, thermal power, and PV generation under uncertainty and nonlinearity. The main contributions are as follows:

A detailed hydropower model is established, incorporating water balance, reservoir dynamics, operational constraints, and nonlinear head–discharge–power characteristics to ensure physical feasibility and scheduling accuracy.

A linearization framework is proposed to approximate nonlinear hydropower constraints, including reservoir storage, tail water level–discharge relations, vibration zones, head loss, and turbine power characteristics, enabling accurate representation of physical features while maintaining computational tractability. The proposed nonlinear constraint processing framework extends beyond traditional convex relaxation and static piecewise linearization by introducing adaptive, physically interpretable reformulations for hydropower-related nonlinearities. Through tailored linearization of head loss, vibration zone, and turbine power coupling constraints, the method maintains global model linearity while dynamically balancing computational efficiency and accuracy.

A comprehensive scheduling framework is constructed that simultaneously accounts for uncertainty and nonlinearity, enabling more realistic and reliable multi-source coordination.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 formulates the optimization-based scheduling model for coordinating multi-type power sources.

Section 3 introduces the proposed methods for handling nonlinearity and uncertainty.

Section 4 discusses the case study and result analysis. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

4. Case Study

4.1. Tested System and Parameter Settings

The modified IEEE −39 system is applied for the case study. It consists of eight thermal power units, four hydroelectric power units, and two PV plants, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The detailed parameters of thermal and hydroelectric power units are listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively. For the PV generation, two plants are integrated into the system, with rated capacities of 1400 MW (PV1) and 600 MW (PV2), corresponding to a penetration rate of approximately 29% (ratio of all PVs’ capacity to the whole power generations’ capacity [

31]).

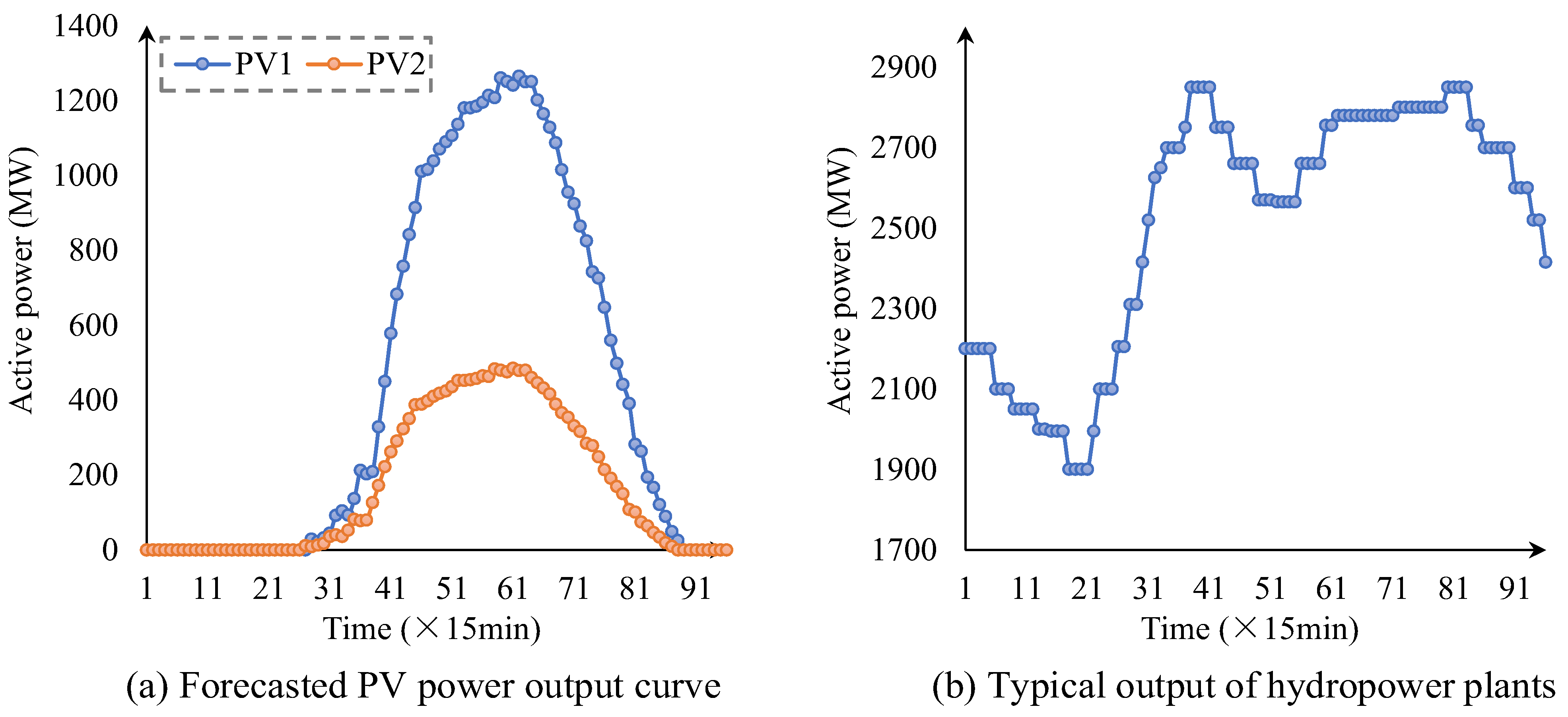

The forecasted power output curves of the two PV plants are illustrated in

Figure 2a, showing the typical daily variation in solar power under different irradiation conditions. The generation schedule of the cascaded hydropower plants is presented in

Figure 2b, exhibiting a clear time-varying pattern. Specifically, the output decreases during the early periods of the day, followed by a gradual increase. In the mid-day to evening hours, the hydropower output reaches relatively higher levels and remains stable.

4.2. Analysis of Scheduling Results

To characterize the impact of uncertainty on scheduling results, this study introduces different confidence levels . The confidence level represents the probability threshold at which the scheduling solution remains feasible under uncertainties. Higher values indicate conservative strategies requiring feasibility in more scenarios, suitable for systems with strict reliability requirements, while lower values allow greater risk tolerance to maximize renewable accommodation. In practice, should be selected considering system reliability standards, historical forecast error distributions, and economic trade-offs between curtailment and generation costs. The confidence level range ( 0.98, 0.96, 0.94, 0.92, 0.90, 0.88) reflects typical reliability standards in power system scheduling.

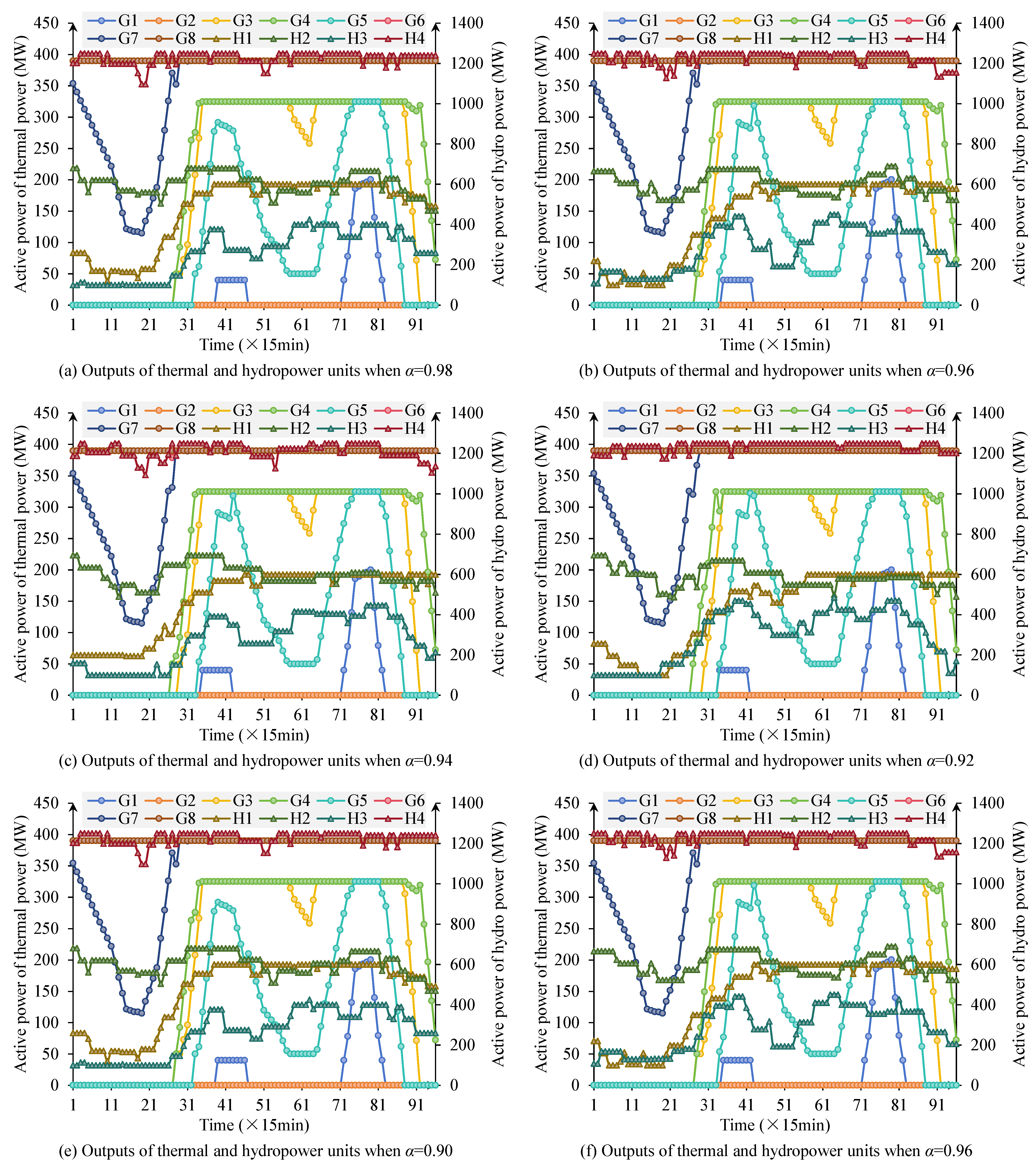

Figure 3 shows the output variation trends of thermal and hydropower units under different confidence levels. When the confidence level is high, the system has strong requirements for preventing stochastic risks. To satisfy strict feasibility requirements under uncertainty, the optimizer adopts conservative strategies by increasing thermal reserves and reducing dependence on variable renewables, representing risk-averse operation suitable for systems with critical reliability requirements. At this stage, thermal units maintain relatively high output levels overall, accompanied by obvious start-stop adjustments to ensure system reliability. The regulation capability of hydropower units is also fully utilized, with output showing strong following characteristics to compensate for PV output fluctuations. During this phase, renewable energy accommodation is somewhat suppressed, PV utilization is insufficient, and curtailment phenomena are prominent. As the confidence level gradually decreases, the scheduling strategy’s tolerance for uncertainty risks increases. Relaxed feasibility constraints enable the optimizer to exploit statistical expectations of renewable output rather than worst-case scenarios, reducing conservative reserve requirements. This manifests as a gradual decline in thermal unit operating frequency and average output, hydropower unit output becoming more stable, and PV and other renewable energy sources receiving more adequate accommodation in the system. Particularly at

, PV output is utilized to a significant extent, and the overall system operational mode shifts from “conservative” to “economic”. This demonstrates that systems with abundant flexibility resources can adopt lower confidence levels to maximize economic and environmental benefits while maintaining acceptable reliability.

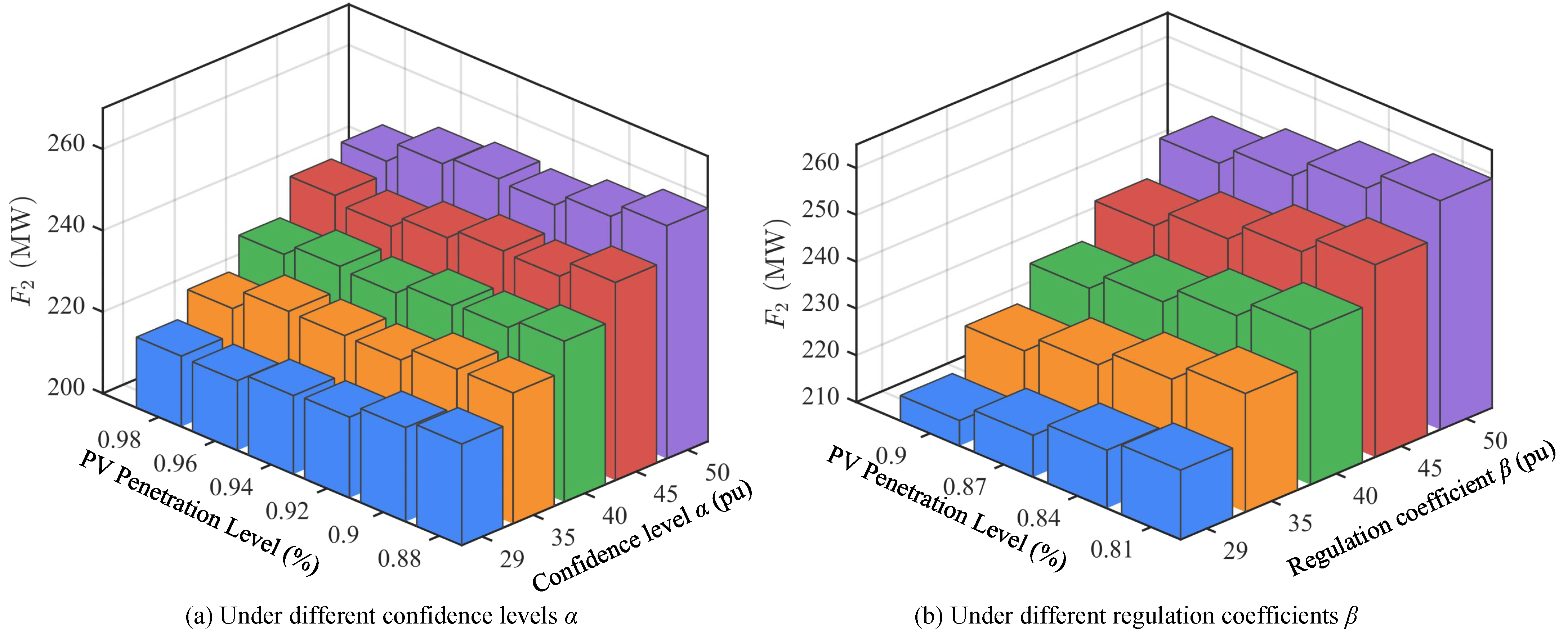

Table 3 lists the three types of objective function values under different confidence levels, further validating the scheduling trends revealed in

Figure 3. Specifically, thermal power operating cost

F1 gradually decreases as the confidence level decreases, from 1.584 × 10

6$ at

to 1.538 × 10

6$ at

, indicating that thermal unit output decreases under lower confidence levels and system operating costs are effectively controlled. The hydropower deviation index

F2 gradually increases as the confidence level decreases, from 215.4 MW to 223.5 MW, suggesting that under low confidence levels, the difference between hydropower units and expected output expands, with the system trading precise hydropower scheduling constraints for better economic performance and renewable energy accommodation. The PV curtailment index

F3 shows a decreasing trend as the confidence level decreases, from 268.9 MW to 253.2 MW, indicating that under low confidence levels, PV output can be more fully integrated into the grid, and curtailment phenomena are significantly improved. Overall, high confidence levels correspond to high reliability but higher costs and severe curtailment, while low confidence levels achieve reduced operating costs and improved PV accommodation at the expense of some hydropower scheduling precision.

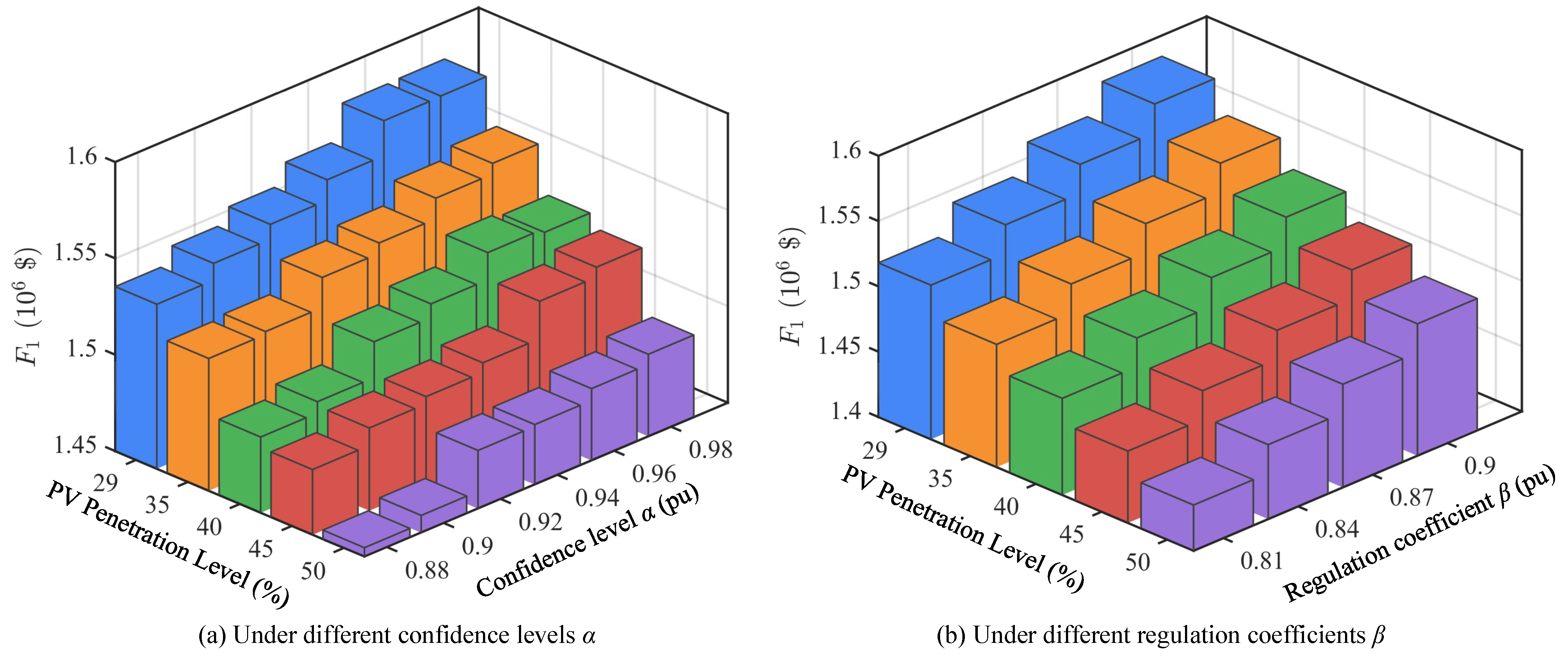

The regulation coefficient dynamically limits thermal power output to prioritize renewable energy accommodation. Larger values provide thermal units more operational freedom, suitable for early-stage renewable integration, while smaller values enforce renewable priority for high-penetration scenarios. In practice, should be selected based on renewable policy targets, thermal unit economic operation ranges, system flexibility requirements, and seasonal renewable patterns, with potential for real-time adjustment. This paper sets , , , , for comparative analysis.

Figure 4 shows the output scheduling curves of thermal and hydropower units under different

values. From the results, it can be seen that as

decreases, thermal unit output is gradually suppressed, the number of start-stop operations of some units decreases, and overall operating levels decline. Smaller

values impose tighter constraints on thermal generation, effectively forcing the system to prioritize renewable accommodation. When thermal power is constrained, hydropower must undertake more load-following and ramping tasks to maintain balance. Correspondingly, the regulation role of hydropower units is further enhanced, with output undertaking more load-following tasks and demonstrating strong ramping capabilities. This trend indicates that smaller

values can effectively suppress excessive thermal power output, making room for renewable energy accommodation. Meanwhile, PV output receives more grid utilization, and curtailment phenomena are alleviated. From an engineering perspective,

serves as a policy instrument for balancing renewable integration targets with system stability requirements and could be dynamically adjusted based on grid conditions and operational priorities. Overall, the smaller the

is, the more the system operating mode tends toward “renewable energy priority”; while the larger the

is, the more system operation relies on thermal power stability.

Table 4 quantitatively presents the three types of objective function values under different

values. From the results, it can be seen that thermal power operating cost

F1 continuously decreases as

decreases, from 1.584 × 10

6$ at

to 1.518 × 10

6$ at

. This indicates that by tightening thermal power output upper limits, the system reduces its dependence on thermal units, effectively controlling operating costs. The hydropower deviation index

F2 gradually increases as

decreases, from 214.2 MW to 224.8 MW, reflecting that under thermal power limitations, hydropower undertakes more load regulation tasks, with increased deviations from expected output. The PV curtailment index

F3 significantly decreases as

decreases, from 268.9 MW to 253.8 MW, indicating that after thermal power output is limited, PV grid output is significantly improved, and curtailment phenomena are alleviated.

4.3. Scheduling Under Different PV Penetration Levels

To further evaluate the impact of large-scale PV integration on power system optimal scheduling, this paper conducts comparative analysis of scheduling results under different PV penetration levels (29–50%), as shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The research focuses on three objective functions: thermal power operating cost

F1, hydropower output deviation index

F2, and PV curtailment index

F3, and examines the impact of different confidence levels

and regulation coefficients

on scheduling results.

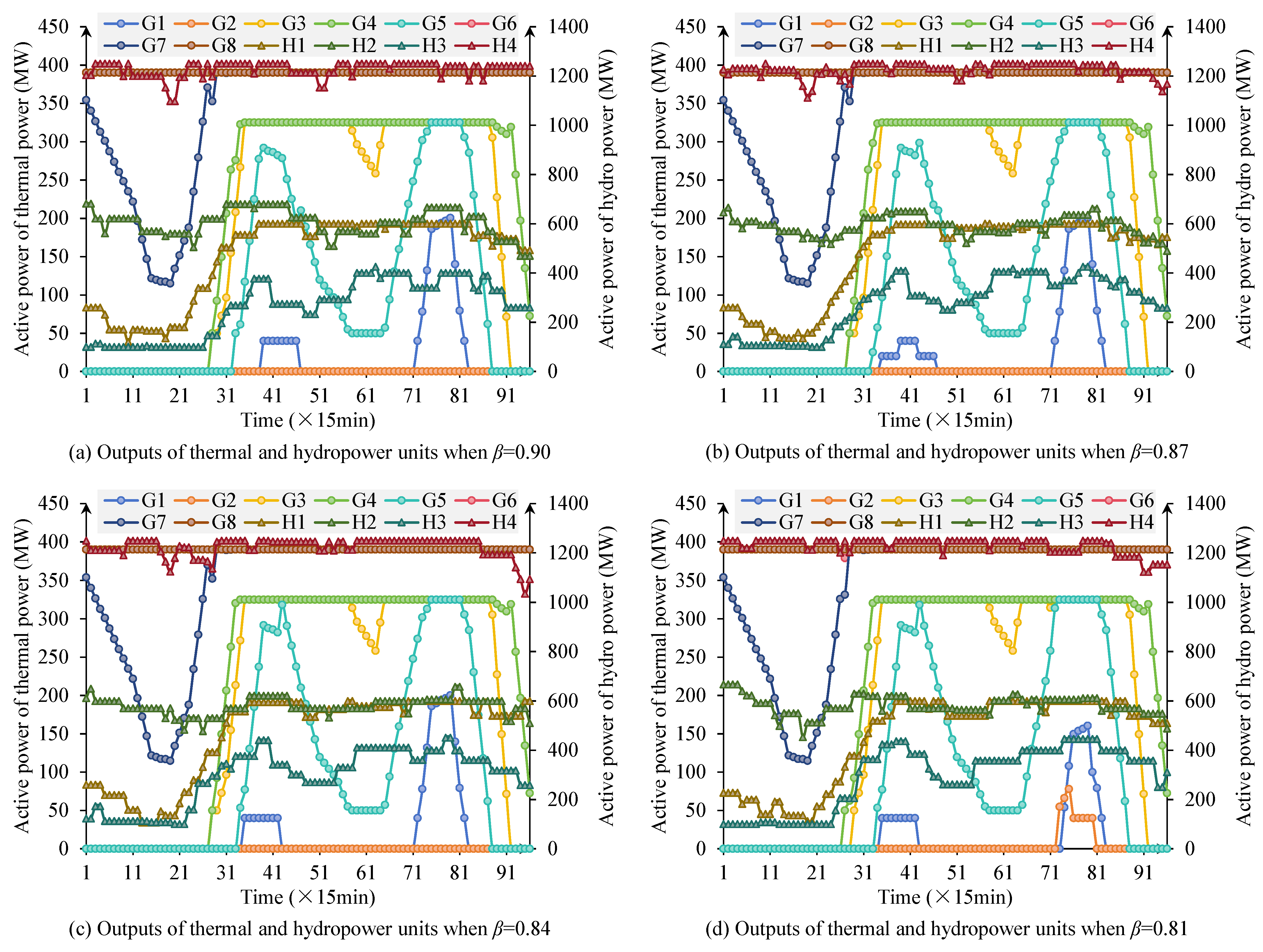

Figure 5 shows the values of objective function

F1 under different PV penetration levels. It can be seen that as PV penetration gradually increases, system dependence on thermal units decreases significantly, resulting in an overall declining trend in operating costs. For example, under conditions of

and

,

F1 decreases from approximately 1.584 × 10

6$ at 29% penetration to approximately 1.501 × 10

6$ at 50% penetration. This trend remains consistent under different confidence levels and regulation coefficients, indicating that increasing PV share can effectively reduce system economic operating costs, but also increases system adaptation requirements for renewable energy fluctuations.

Figure 6 shows the values of objective function

F2 under different PV penetration levels. Contrary to

F1,

F2 gradually increases with increasing PV penetration, rising from approximately 215 MW at 29% to over 250 MW at 50%. This indicates that under high-proportion PV integration, hydropower units undertake more regulation tasks to balance PV output fluctuations and uncertainties. Therefore, hydropower unit scheduling flexibility requirements continue to strengthen, and their operational deviations expand accordingly. This result highlights the important role of hydropower as the main flexible regulation resource under high penetration scenarios.

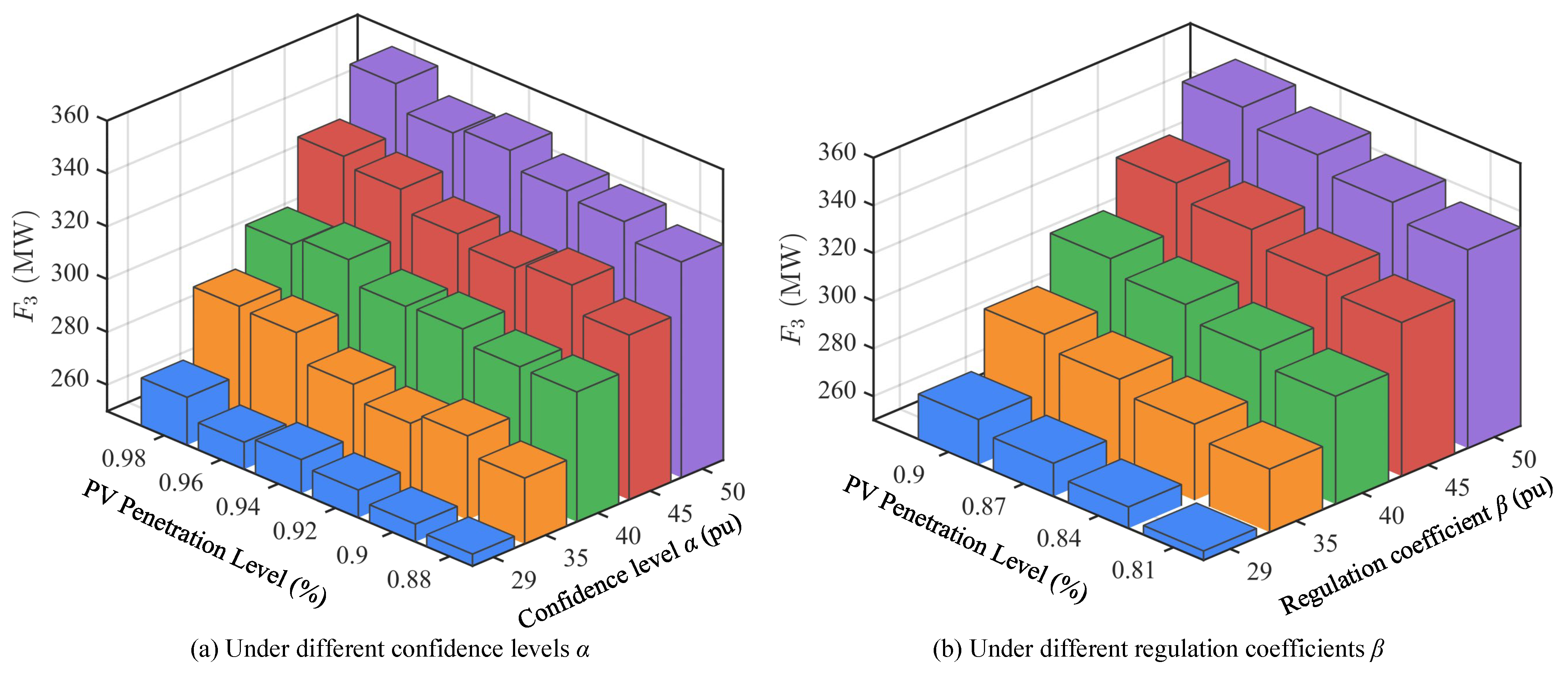

Figure 7 shows the values of objective function

F3 under different PV penetration levels. From the changes in PV curtailment index

F3, as penetration increases, curtailment shows a gradual upward trend. At 29% PV penetration, curtailment is relatively low, while at 50% penetration,

F3 has exceeded 330 MW. This indicates that under insufficient system regulation capability, high-proportion PV integration inevitably brings higher curtailment risks. However, reasonable settings of regulation coefficient

and confidence level

can alleviate curtailment problems to some extent, enabling more effective utilization of renewable energy sources.

In summary, scheduling results under different PV penetration levels show significant differences. As PV penetration increases, thermal power operating costs continue to decrease, reflecting the gradual weakening of system dependence on thermal units; meanwhile, hydropower deviation indices show an increasing trend, indicating that hydropower units undertake more regulation tasks; PV curtailment indices also gradually increase with penetration, reflecting more obvious PV output limitations under high penetration conditions.

4.4. Error Analysis of Nonlinear Constraint Linearization

In this section, the accuracy of handling nonlinear constraints in the scheduling model is evaluated. The analysis focuses on the linearization of the water level–storage and tail water level–discharge relationships, the effectiveness of vibration zone constraints, the impact of output fluctuation duration constraints, and the approximation of head loss and power surface functions.

The operating ranges of typical cascade hydropower stations are selected as test conditions, where the upstream water level varies within the 800–880 m range, corresponding to storage capacities of 1.2 × 10

8–3.6 × 10

8 m

3; unit discharge ranges from 300 to 1000 m

3/s, corresponding to tail water levels between 120 and 138 m. Based on data from this operating range, the linearization accuracy of water level–storage and tail water level–discharge relationships is analyzed, with results shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6. From the comparison results, it can be seen that the piecewise linear interpolation method can well approximate the original nonlinear curves. For the water level–storage relationship, errors between fitted values and actual values are small, with overall relative errors consistently controlled within 1%, indicating that storage estimation can maintain high reliability. In the tail water level–discharge relationship, piecewise linear approximation also shows good fitting performance, with relative errors all below 0.5%, accurately reflecting the variation pattern of tail water levels with discharge. Comprehensively, the piecewise linearization method significantly reduces the nonlinear complexity of the model while ensuring low error levels, providing efficient and accurate mathematical expressions for subsequent scheduling optimization. This precision level fully meets the requirements of practical scheduling applications.

This paper adopts linearized vibration zone avoidance constraints aimed at preventing hydropower units from entering mechanical vibration zones during scheduling, preventing equipment wear or operational risks caused by long-term operation in unstable conditions. Case study results show that in all operating scenarios set in this paper, each unit does not enter its respective vibration zone throughout the entire scheduling period, indicating that the constraints effectively function. Taking

Figure 3a as an example, H1’s output always remains above 150 MW or far above the upper limit, avoiding the (90–150 MW) vibration zone; H2’s output is mostly above 500 MW, not entering the (105–175 MW) unstable interval; H3’s minimum output maintains at 100 MW, above the (60–100 MW) boundary; H4’s output basically maintains at 1150–1250 MW, avoiding the (190–320 MW) interval. This shows that the proposed vibration zone avoidance constraints achieve the expected goal during the optimization scheduling process, namely using auxiliary variables and the big-M method to logically separate unit output from vibration zone intervals, making the feasible solution space automatically avoid unsafe intervals. The results not only ensure the safety and stability of operating curves but also verify the feasibility and practical value of this method in complex scheduling models.

Next, the impact of output fluctuation duration constraints (minimum duration time) is analyzed. This paper introduces output fluctuation duration constraints in the scheduling model, stipulating that units must maintain a certain minimum duration time during power increase or decrease processes to avoid short-term frequent fluctuations. To verify the effectiveness of this constraint, this paper sets two scenarios for comparison: one is “without considering output fluctuation constraints,” and the other is “considering minimum duration constraints (4 periods),” with results shown in

Table 7. It can be seen that without considering constraints, hydropower unit output curves show multiple rapid increase-decrease switches, with cumulative fluctuation counts reaching 14 times, and some continuous power increase processes lasting only 1 period. After considering minimum duration constraints, unit fluctuation counts decrease to 6 times, with single increase-decrease process durations all exceeding 4 periods, making curve changes smoother. Further comparison of system operating indices reveals that although introducing this constraint slightly reduces hydropower-thermal coordination, leading to approximately 1.1% increase in overall operating costs, it effectively avoids frequent hydropower regulation and improves system stability.

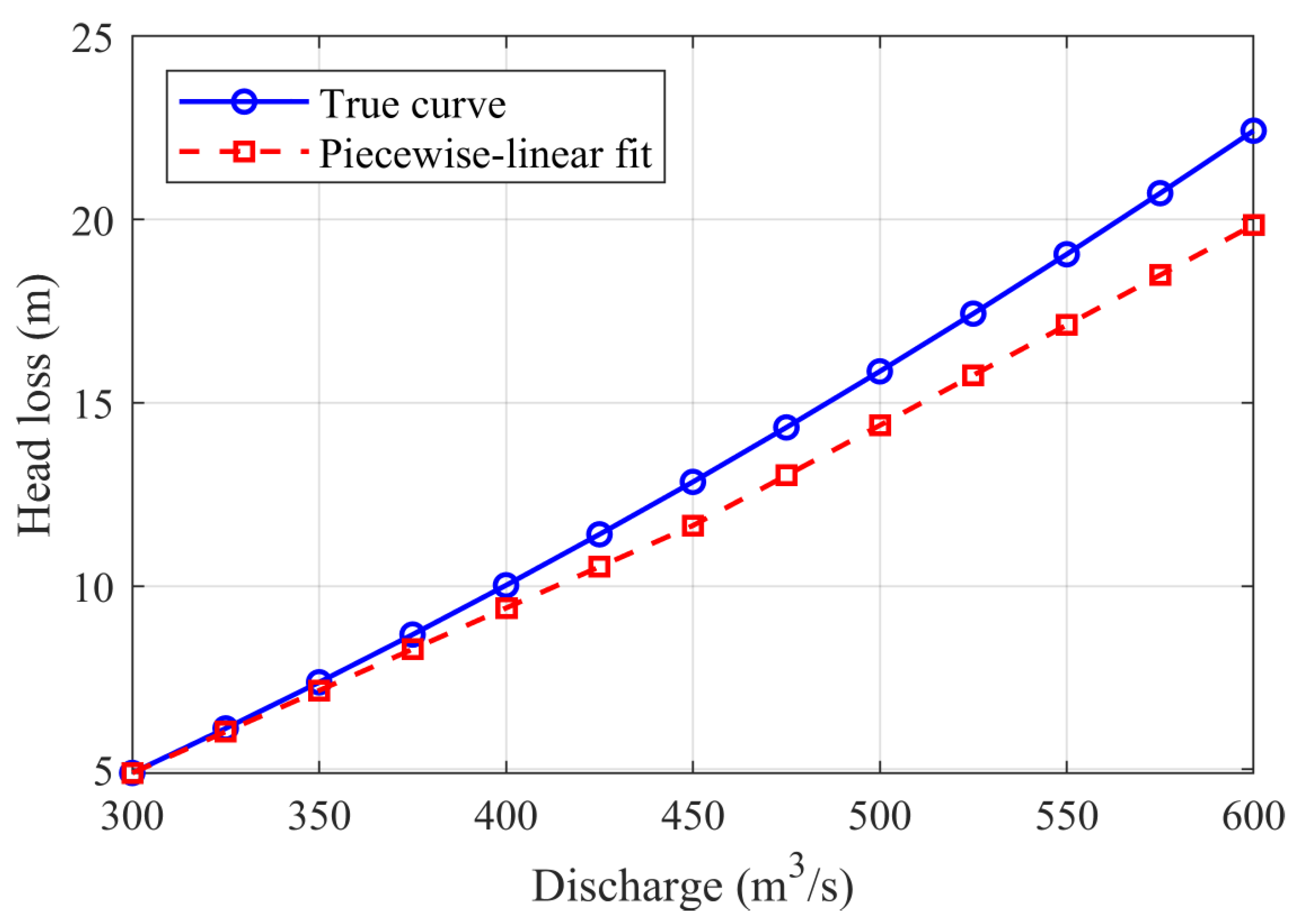

To ensure modeling accuracy while reducing the nonlinear complexity of optimization problems, this paper adopts piecewise linear and piecewise bilinear approximations for the head loss function

and unit dynamic characteristics

(power-head-discharge bivariate relationship), respectively. First, within the discharge range

, two-segment piecewise linear functions are constructed using endpoint interpolation (segment points 300, 450, 600), and fitting errors are evaluated at 25 m

3/s fine-grain sampling, with results shown in

Figure 8. It can be seen that piecewise linear fitting can well approximate the original head loss curve, with mean absolute error (MAE) of approximately 0.021 m, maximum absolute error of approximately 0.042 m, and relative error peak not exceeding 0.45%, indicating that this approximation is sufficient to replace the original nonlinear relationship at the scheduling scale.

For unit dynamic characteristics

, within the head range

and discharge range

, segment points

= 125, 127.5, 130, 132.5, 135 and

= 300, 375, 450, 525, 600 are selected to construct a two-dimensional grid for bilinear interpolation approximation of the power surface, with absolute errors between fitted results and actual values shown in

Figure 9. It can be seen that the maximum absolute error is approximately 2.078 MW, with relative error peak not exceeding 0.74%. Therefore, using a small number of segments can effectively linearize the bivariate coupling

while ensuring high accuracy. The segmentation scheme adopted in this study achieves a good balance between engineering computability and approximation accuracy, providing a stable and reliable linear approximation model for scheduling optimization.

4.5. Comparison with Other Method

As a reference method, we construct a full nonlinear mixed-integer benchmark (MINLP) that preserves all hydropower physics without linearization. The water level–storage and tailwater–discharge relations are modeled by cubic-spline interpolation; head-loss is kept in its quadratic form; and the turbine power–head–discharge coupling is represented by the original bilinear/quadratic equations. Vibration-zone avoidance and minimum output-duration constraints are imposed with binary variables (big-M) and logical linking constraints (the same logic as in the proposed model, but without linear surrogates for the physics). The day-ahead horizon, discretization, initial/terminal levels, PV/load scenarios, and all operational bounds are identical to the proposed method to ensure fairness. The MINLP is solved by a state-of-the-art nonlinear branch-and-bound solver with relative/absolute optimality tolerances of 10−4/10−6, feasibility tolerance 10−6, and a wall-clock limit of 3600 s; warm starts are disabled to avoid bias.

We compared the (i) objective value and relative optimality gap, (ii) CPU time, and (iii) constraint violations of the proposed method and the compared method. The results are shown in

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10. Based on these results, the Proposed method demonstrates clear advantages over the Compared method in both computational efficiency and practical accuracy. As shown in

Table 8, the Proposed method achieves nearly identical objective value (1.584 × 10

6$ vs. 1.592 × 10

6$) while reaching a proven optimal solution with zero optimality gap, whereas the Compared method retains a 1.2% residual gap after reaching the time limit.

Table 9 further indicates that the Proposed method converges within 182 s—over 20 times faster than the Compared method, which requires the full 3600 s time limit without full convergence. Regarding model fidelity (

Table 10), the Proposed method maintains small approximation errors in the hydropower physics—storage, tailwater level, and head-loss MAEs remain below 1% of their respective ranges—and negligible power-balance violations, confirming that linearization does not significantly compromise accuracy. Overall, these results verify that the Proposed method achieves a favorable balance between modeling precision and computational tractability, making it more suitable for large-scale, time-sensitive power-system scheduling applications.