1. Introduction

Air pollution poses a significant and pressing challenge for modern society. Its detrimental effects extend beyond the environment, encompassing glacier melting, extreme temperature variations, droughts, and floods. Moreover, air pollution has grave implications for human well-being and health. These consequences include cardiovascular disease and asthma [

1], as well as pneumonia and influenza in the elderly [

2]. Globally, approximately 1.1 billion people are exposed to unhealthy air each year, resulting in 7 million deaths [

3,

4]. To effectively combat air pollution, it is essential to accurately identify the sources of pollution. There are two main approaches for achieving precise pollutant localization: pollutant dispersion modeling through air dynamic simulation and extensive monitoring of air sensors.

The study of pollutant dispersion using physical modeling tracking methods has been conducted in recent years. Douglas et al. studied the dispersion of bioaerosols using an atmospheric dispersion model [

5]. Parvez et al. proposed a local-scale dispersion model R-LINE to estimate the mass of road emission sources [

6]. Monbureau et al. proposed a modification to the plume dispersion model that significantly improved the simulation of ground-level pollutant concentrations in buildings [

7]. However, contaminant traceability approaches based on physical or statistical methods have some drawbacks. The approach proposed by Karl et al. [

8] for estimating air pollutants using deterministic chemical transport models that incorporate meteorological, physical, and chemical processes is susceptible to uncertainties in emission quantities and chemical reactions. Meanwhile, methods for predicting pollutants by statistical models, such as multiple linear regression models [

9] and geographically weighted regression models [

10], often result from simplifying the complex relationships between air pollutant concentrations and predictor variables. Also, due to the lack of bandwidth [

11], network security vulnerability issues [

12], and insufficient data protection [

13,

14] in the traditional IoT context. We present a novel algorithm that integrates a federated learning (FL) framework and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model to enhance the Gaussian model through a retrospective approach. FL is widely used as one of the most promising distributed machine learning frameworks, enabling resource-constrained edge devices to collaboratively build shared global models [

15]. In light of the increasing focus on data protection in both domestic and international legal frameworks, Federated Learning (FL) is emerging as a prominent machine learning technique to address the issue of data silos prevalent in modern times. Diverging from traditional federated learning approaches, our methodology utilizes genetic algorithms instead of cloud neural networks to accelerate the learning process and achieve iterative optimization.

With the rapid development of AI (Artificial Intelligence) and IoT (Internet of Things), it is widely considered that AIoT systems, such as intelligent light poles with detection modules, are also effectively used for air quality monitoring. However, these systems use monitoring data for air quality analysis offline and do not achieve real-time intelligent computing analysis with edge intelligence algorithms. The number of installations is constrained and unable to satisfy the intricate requirements of air pollution traceability due to the high cost of building, operating, and maintaining such fixed systems. Additionally, the currently common compact sensors are only functional for the surroundings around the instrument and are unable to adequately respond to the overall air quality in an area, particularly in cities where air pollution in cities is related to terrain and building height. An important problem arises when attempting to identify the source of contaminants at certain nodes. In terms of IoT technologies, Abbas et al. developed a smart meter based on Narrowband IoT [

16]. Ejaz et al. investigated the problem of energy-efficient scheduling for smart homes and wireless power transmission for the Internet of Things in smart cities [

17]. In addition to these applications, 5G and Wi-Fi can also be relevant to the operation of smart cities [

18]. The theory of collaborative multi-intelligent body sensing has strong technical backing thanks to the convergence of edge computing and networked communication discovery. Edge computing has attracted increasing attention as an effective solution to address long latency issues and enhance existing network architectures [

19]. The hypothesis of multi-intelligent body collaborative perception is well supported technically by the convergence of edge computing and networked communication discovery.

In this paper, we design an air pollutant traceability system based on EIPA networks. The contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

The EIPA networks refer to a type of multi-agent network that combines Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things. In this network, intelligent light poles are installed with wireless sensors and edge computing capabilities, serving as stationary agent nodes.

- (2)

In order to accurately track the location of air pollution, it is crucial to implement a sophisticated air quality monitoring system that can operate in various weather conditions. In this study, we propose the development of an Enhanced Intelligent Lamp-Post (EIPA) system, which involves integrating air quality sensors and edge computing technology into conventional lamp-posts. Additionally, we introduce a novel algorithm that enables the traceability of air pollutants through a collaborative learning approach involving cloud and edge computing.

- (3)

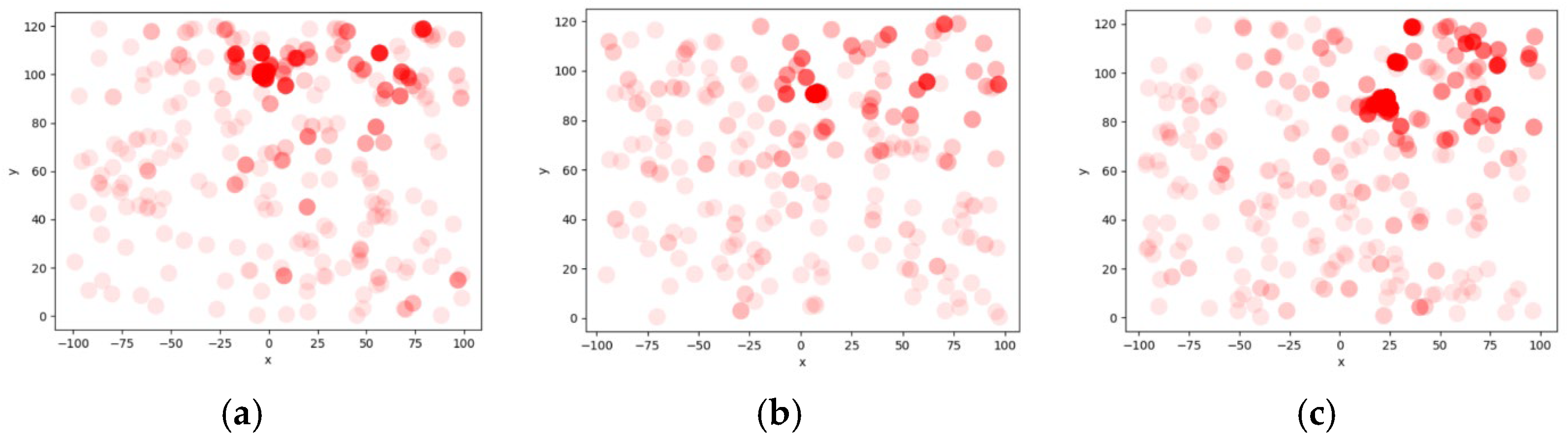

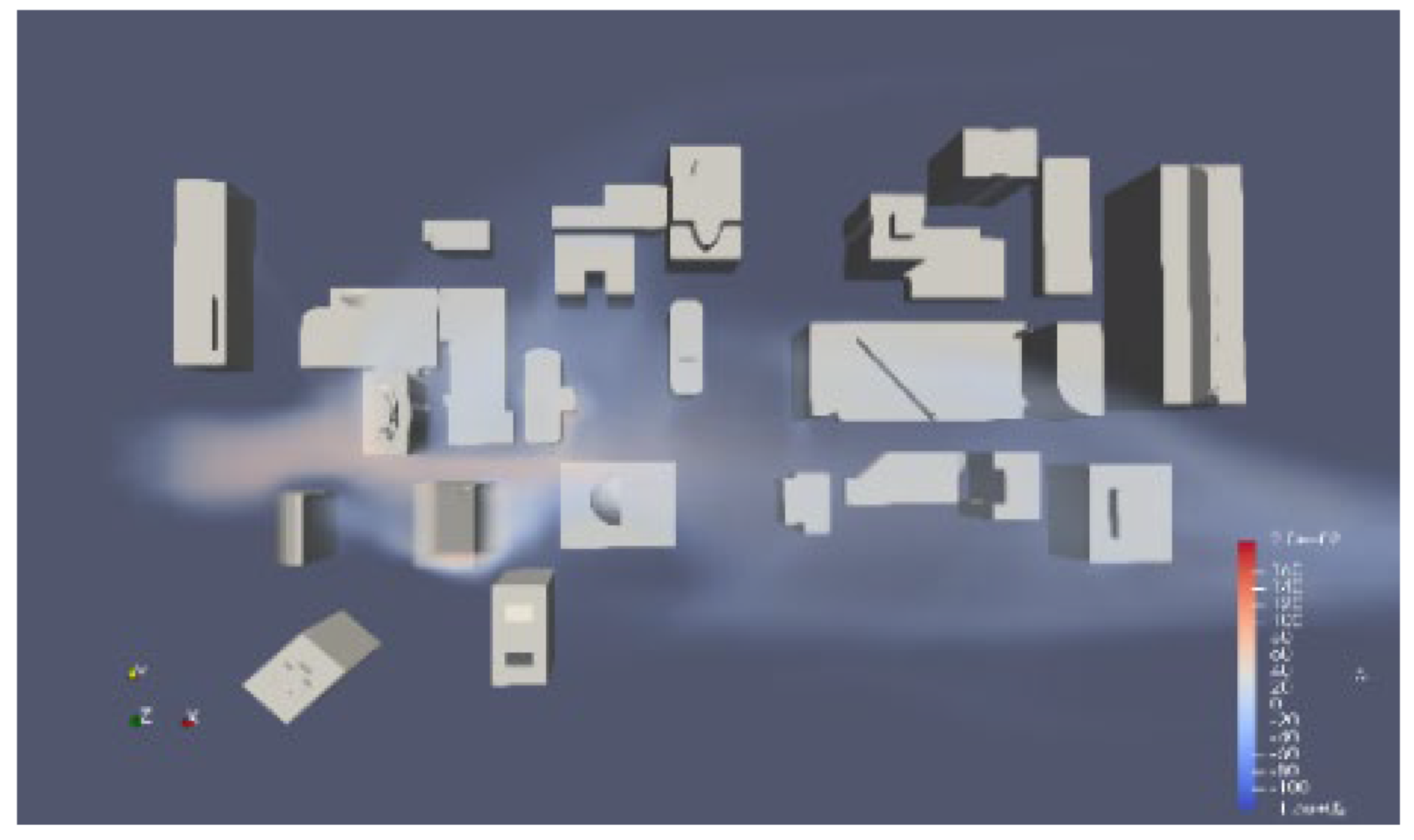

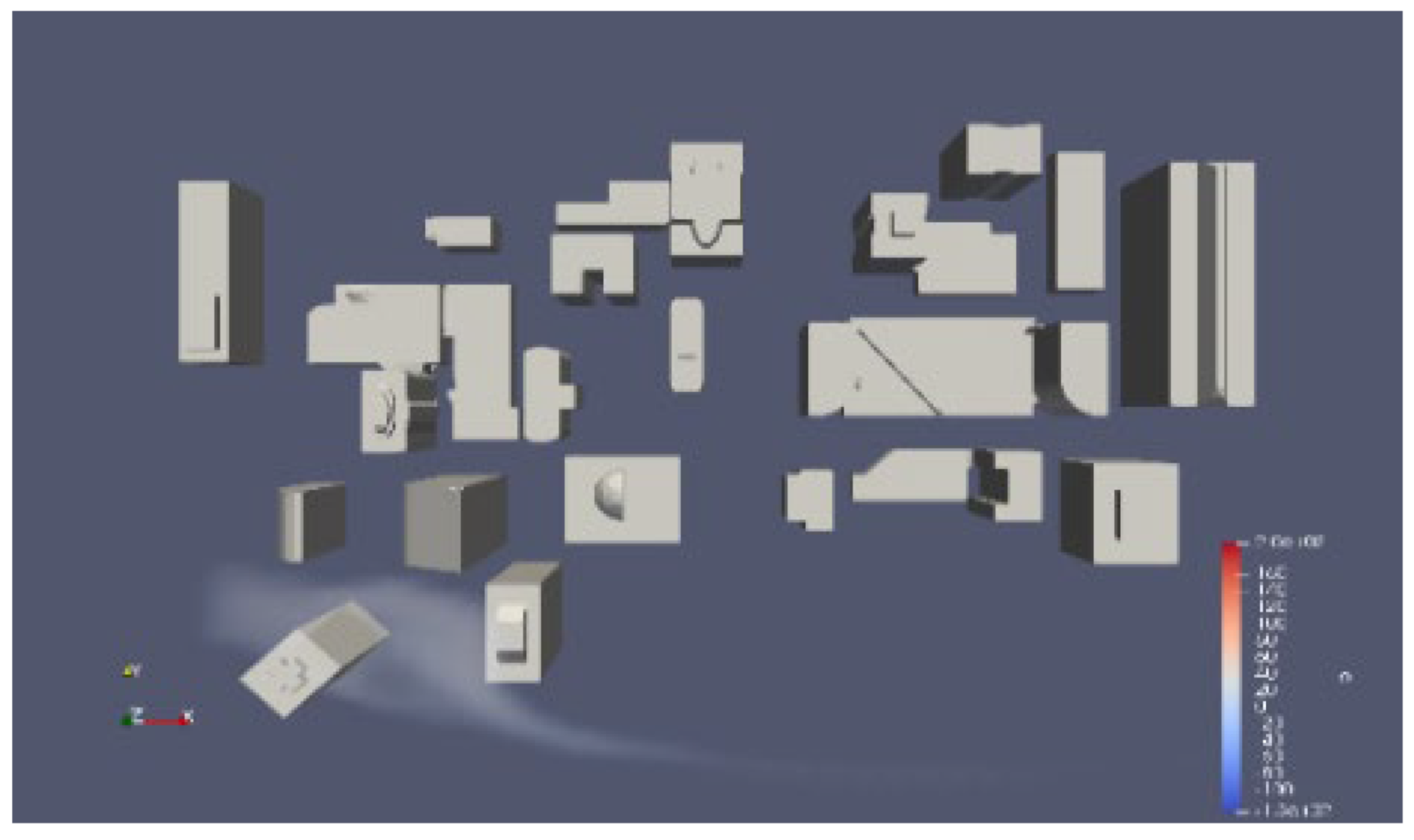

Owing to the limited occurrence of air pollution events within industrial parks, the acquisition of an adequate amount of pollution data presents a challenge. To address this issue, we have developed a dataset using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation. This dataset allows for the analysis of air pollutant data and the verification of the air pollutant traceability algorithm. The findings of our study demonstrate promising potential for the application of the EIPA system. Furthermore, we have made our data openly accessible to other researchers to facilitate further investigations in this field.

- (4)

Air pollutants are a complex mixture of gases and particulate matter that can have detrimental effects on both the environment and human health. Major gaseous pollutants include nitrogen oxides (NO

x), sulfur dioxide (SO

2), carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O

3), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), while particulate matter (PM) is classified by size as PM

10 (diameter ≤ 10 μm) and PM

2.5 (diameter ≤ 2.5 μm). These pollutants originate from diverse sources such as industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust, coal combustion, and natural processes [

20].

PM

2.5, in particular, has attracted significant attention due to its ability to penetrate deep into the respiratory system and enter the bloodstream, causing chronic respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [

21]. The chemical composition of these pollutants varies widely depending on emission sources and atmospheric transformation processes, making accurate traceability a challenging task. In urban environments, the interaction between pollutants and meteorological conditions further complicates the dispersion patterns of pollutants.

Effective management and mitigation of air pollution require not only advanced monitoring technologies but also a comprehensive understanding of pollutant behavior in different environmental contexts. Recent studies have focused on developing integrated approaches combining real-time sensing, data-driven modeling, and physical simulations to improve the accuracy of pollution source identification and prediction [

22]. Such approaches are crucial for formulating targeted pollution control strategies and protecting public health.

To address the challenges of air pollutant traceability in complex urban environments, this paper proposes an innovative approach that integrates federated learning, LSTM, and genetic algorithms within an Edge Intelligent Perception Agent (EIPA) network. The subsequent sections are organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review, highlighting the limitations of existing physicochemical, statistical, and machine learning-based methods for pollution source localization.

Section 3 details the proposed methodology, including the hardware architecture of the EIPA system, the federated learning framework, the LSTM model design, and the integration with genetic algorithms for parameter optimization.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup, dataset generation using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, and the evaluation results comparing the proposed approach with traditional methods. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the key findings, discusses the practical implications of the research, and outlines potential directions for future work.

3. Methodology

3.1. Hardware Architecture and Data Acquisition Methods

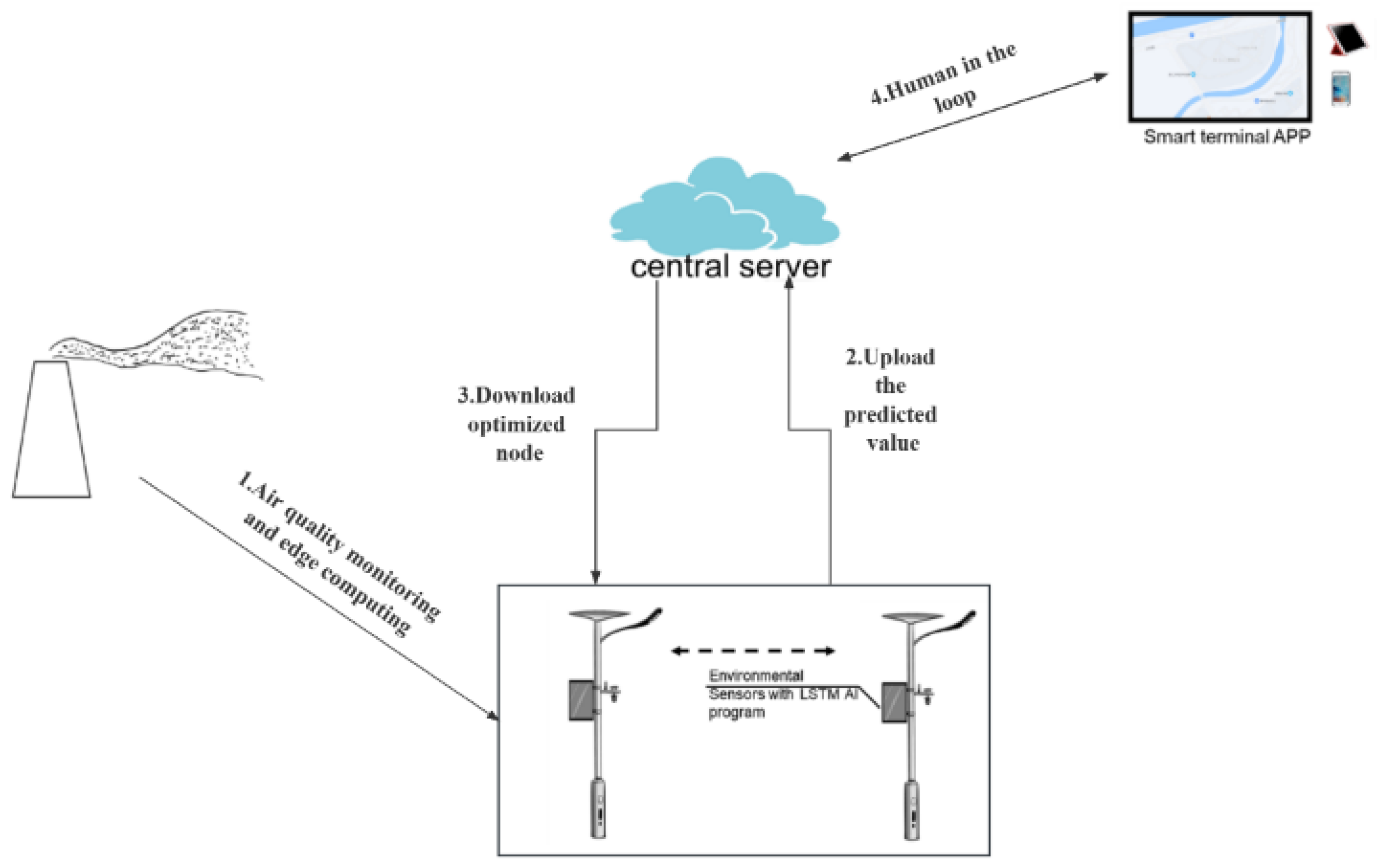

The EIPA network has been designed with the objective of providing a comprehensive artificial intelligence (AI) solution and facilitating the development of smart cities. The hardware architecture and data flow of the EIPA network are illustrated in

Figure 1. The static nodes, represented by smart light poles, serve as the foundation for edge computing and smart sensing networks, enabling various applications in smart cities, including air pollution monitoring. The EIPA system can sense the urban environment autonomously and flexibly by collaborating with static nodes. The EIPA nodes will establish communication with the server in order to exchange information and receive commands for activating various functions. Additionally, a smart terminal application has been developed to operate on the EIPA network. This application serves as a control interface, enabling human operators to monitor and control various nodes. After obtaining the location of the contaminant dispersion center, the administrator can assess the leakage situation and take appropriate measures. In this paper, we mainly introduce the construction of the EIPA static node and its application algorithm.

Each static EIPA node is capable of autonomously selecting multi-modal sensors according to specific environmental monitoring requirements, thereby constructing a sensor array to fulfill diverse monitoring needs. The selection of sensors presented in

Table 1 highlights some of the ones utilized in our study.

The DHT11 module is a sensor used for measuring temperature and humidity. It consists of an 8-bit microcontroller unit (MCU) that is connected to a resistive humidity sensing element and a Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC) temperature measuring element. The module retrieves data by reading the value from the MCU.

The MQ-2, MQ-7, and MQ-137 sensors are part of a series of sensors that monitor gas composition. These sensors utilize tin dioxide as a gas-sensitive material, which becomes highly reactive when heated to its operating temperature. At this temperature, tin dioxide adsorbs oxygen from the surrounding air, leading to the formation of negatively charged oxygen ions. This process results in a reduction in electron density within the semiconductor, thereby increasing its resistance. When the sensor comes into contact with smoke, the concentration of smoke causes a change in the potential barrier at the intergranular boundary, resulting in a modification of surface conductivity. By utilizing this phenomenon, it becomes possible to gather information regarding the presence of smoke. The relationship between smoke concentration and electrical conductivity is directly proportional, while the relationship between smoke concentration and output resistance is inversely proportional. Consequently, a higher concentration of smoke leads to a stronger output analog signal. The MQ-2 sensor, known for its high sensitivity to alkane smoke and resistance to interference, is employed in conjunction with an ADC circuit to convert the voltage signal into a digital format. This digital signal is then further processed to obtain an accurate measurement of smoke concentration. The MQ-7 sensor utilizes temperature cycle detection methods to detect the concentration of carbon monoxide. It employs low temperature (1.5 V voltage heating) to detect carbon monoxide by measuring the conductivity of the sensor with the air containing carbon monoxide gas. The conductivity of the sensor increases as the concentration of carbon monoxide gas in the air rises. On the other hand, a high temperature (5.0 V heating) is used to eliminate any stray gas that may have been adsorbed at a low temperature. The MQ-137 sensor is specifically designed to detect ammonia gas in the surrounding environment. The conductivity of the sensor increases in proportion to the concentration of ammonia gas in the air. This information can be collected by the ADC circuit to accurately determine the concentration of ammonia gas.

The BMP388 air pressure sensor adopts piezoelectric pressure sensor technology, offering higher resolution and lower power consumption. The BMP388 barometric pressure sensor adopts piezoelectric pressure sensor technology with higher resolution and lower power consumption. It converts the voltage signal into a digital signal and then accurately measures the barometric pressure value using the ADC circuit.

After obtaining the environmental parameters, a Gaussian dispersion model can be used to fit the dispersion state of the pollutant. The equation of the Gaussian dispersion model is as follows:

where

Q represents the intensity of the field source pollutant, V denotes the measured wind speed, Ci represents the concentration of the pollutant detected at the ith light pole, and

σy and

σz are the diffusion coefficients of pollutants in the horizontal and vertical directions. H is the effective source height, y is the distance relative to the pollutant centerline in the perpendicular direction, and z is the height of the monitoring point.

The functions of

σy and

σz are presented:

where x is the relative distance of the light pole in the downwind direction of the pollution source.

Table 2 shows the reference values of parameters

a,

b,

c, and

d.

The traditional Gaussian model, however, is no longer suitable for modeling the dispersion of air pollutants within cities due to the high level of development of modern cities and the shading of pollutants by tall structures. We divide the metropolitan areas using intelligent light poles and independently update the Gaussian dispersion models in each area to address the issue of pollutant dispersion in contemporary cities.

3.2. Federated Learning Algorithm Design

In the context of federated learning (FL), intelligent terminals leverage their local data to train a deep learning model that is necessary for the central server. Subsequently, these intelligent terminals transmit the model parameters, as opposed to the raw data, to the server to facilitate cooperative learning tasks. Due to its ability to protect data privacy, Lee et al. applied federated learning (FL) to medical image analysis, specifically in the context of thyroid ultrasound image analysis [

30]. Nehal Muthukumar discusses the use of FL in natural language processing [

31] by incorporating the Amazon Review dataset. Wu et al. applied this approach to IoT-based human activity recognition [

32] as a way to enhance security and privacy within the IoT context. The anonymity of air pollutant traceability research is not an issue, though. FL has the ability to reduce data connection bandwidth and excels at activities requiring real-time dynamic air pollutant traceability.

We have enhanced the conventional FedAVG algorithm to facilitate the implementation of distributed joint learning. In the original FedAVG approach, during each iteration, a central server chooses a fixed number of nodes (k) to distribute copies of the initial model parameters (vt). The selected static nodes update the local model wk,t, 0 = vt with the received model parameters. They will be trained locally using the environmental data detected by the sensors on the nodes, with Ω local iterations performed by the optimizer, after which each static node uploads the local model wk,t +1 = wk, t, Ω to the central server, which aggregates them to get a new global model [

33] for the next training session.

In this case, the central server or other nodes never directly see the data on any other nodes, which effectively protects data privacy.

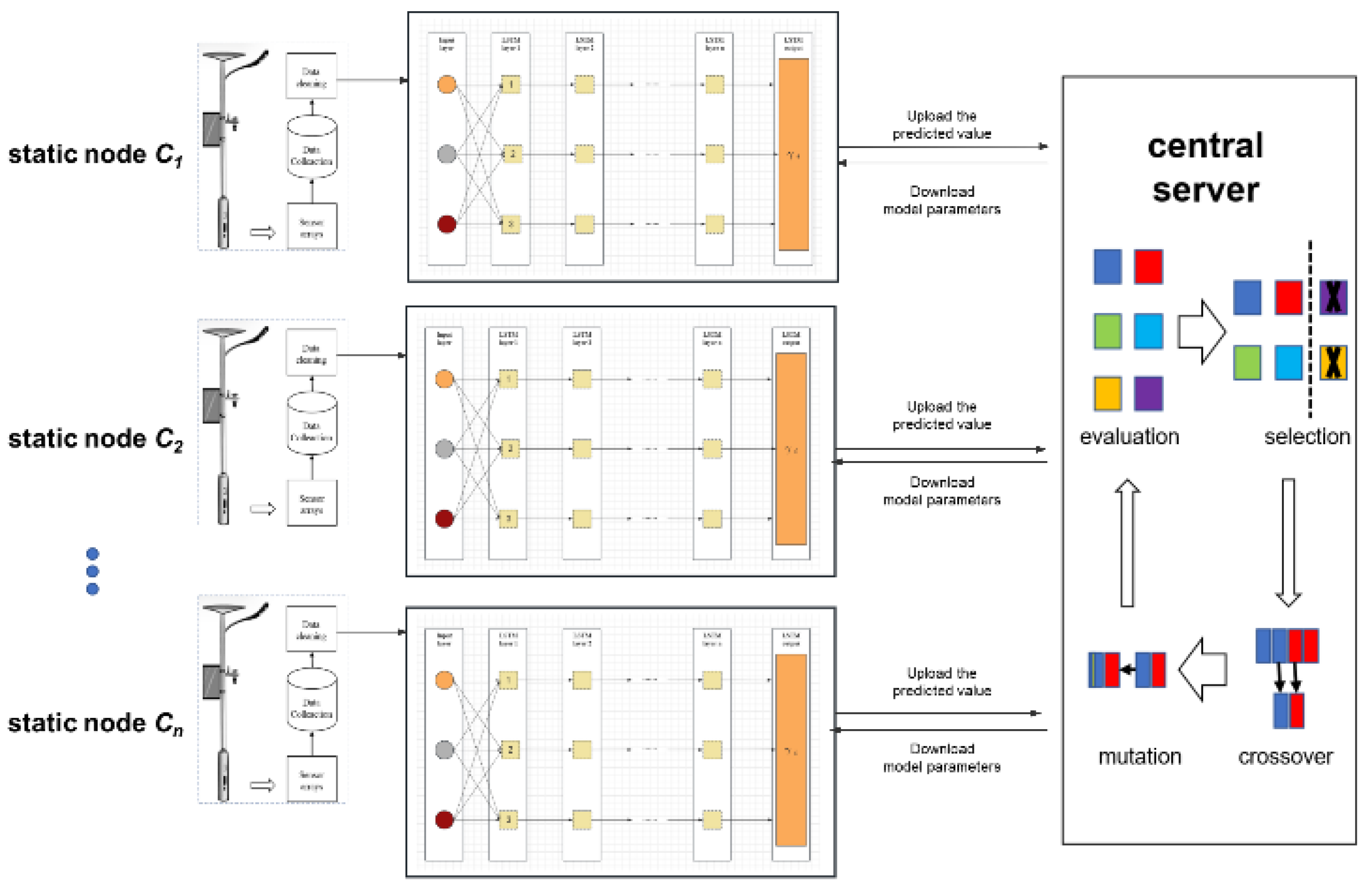

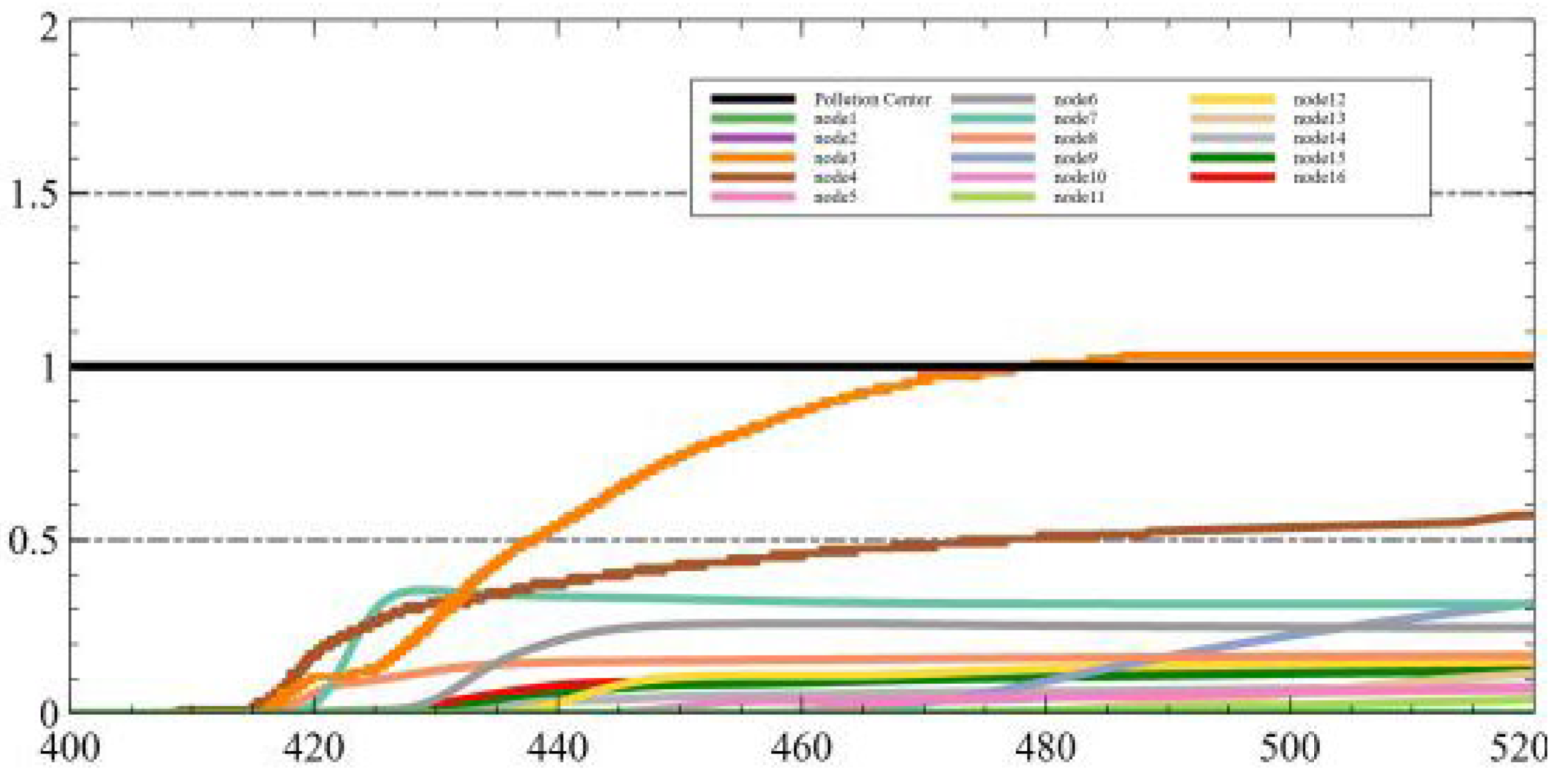

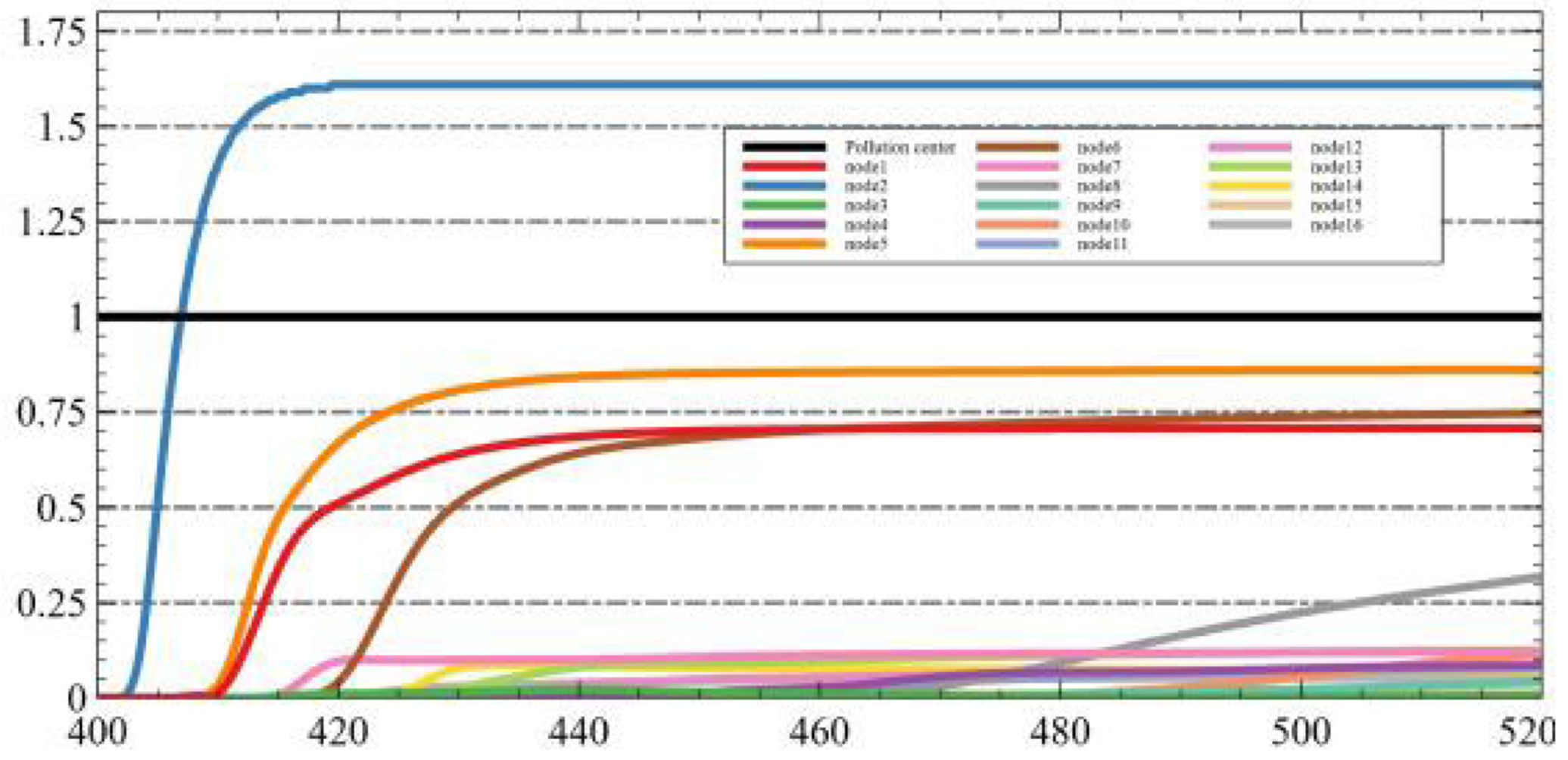

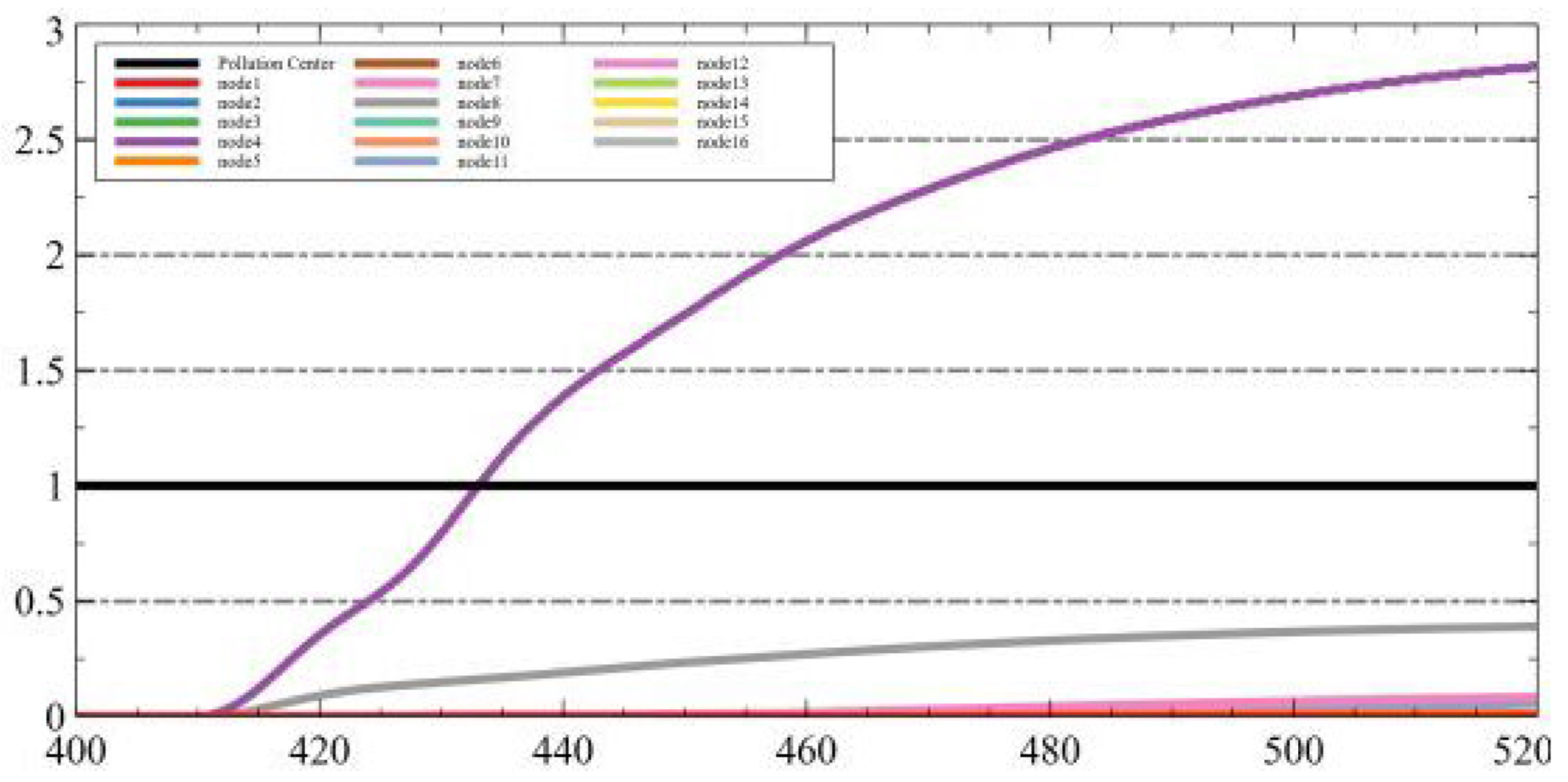

Our enhanced algorithm for tracking the origins of pollution from air pollution data incorporates a novel FL model that combines LSTM and GA. The complete workflow of the algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 2. Each stationary node collects and preprocesses time series data using a sensor array integrated with a lamp pole. The edge computing module, equipped with the lamp pole, utilizes long-term and short-term memory modules to learn from extensive data. Afterward, the training model parameters and predicted values are uploaded to the central server, where the FedAVG, combined with the GA optimization program, is executed. The detailed design of the GA and the LSTM learning process is elaborated in

Section 3.4.

The aim of the entire Federated Learning framework is to optimize the gain factor

γi for the Gaussian diffusion model and to make full use of the edge computing module on the smart light pole while reducing the burden on the central server. In an infinitely large unobstructed wind field, the concept of

γi is presented:

where Ci is the concentration of the pollutant detected by the ith static node, C is the concentration of the source, and ‘ρ-Ri’ is the distance from the source to the monitoring point of the ith static node.

However, in different urban environments, γi varies with the topography, so for the intra-city pollution dispersion problem, we need to obtain a refined gain factor for small areas.

In the event of a release of contaminants, the stationary node promptly notifies the server of any significant changes in the concentration of the contaminant. Subsequently, the server distributes a copy of the parameters of the global model to all stationary nodes that have detected a change in contaminant concentration. To effectively accomplish our objective in a practical setting, it is necessary to incorporate additional processing from the server to the nodes. The server has the capability to communicate with both stationary nodes via the Internet or wireless networks. We make the assumption that the following scenarios will occur:

− Increase: When there is a pollutant leak, the EIPA system will add all EIPA Static nodes Ci that detect a change in pollutant concentration to the server. The server will then issue an initial model and give each node an initial weight tij for the current leaked pollutant, where tij represents the weight of the jth pollutant detected by EIPA node Ci.

− Decrease: Whenever an EIPA node detects a change in pollutant concentration less than εj, the EIPA system will automatically remove the Static node from the server, along with the weight tij of the node.

− Periodic Response: At regular intervals, the EIPA system will broadcast an interrogation message to all nodes to ensure that all nodes are online and can be activated quickly for contaminant processing.

Upon receiving the global model parameters from the central server, the static node proceeds to update its local model and utilize the local data for training purposes. The input data consists of meteorological information along with pollutant concentrations. The air quality data is collected by sensor arrays placed at static EIPA nodes, which monitor several important air pollutants, including particulate matter (PM10 or PM2.5), ammonia (NH3), and carbon monoxide (CO). These pollutants are commonly employed in the calculation of the Air Quality Index (AQI) for specific locations. The static EIPA node simultaneously maintains a record of diverse meteorological parameters, such as relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, temperature, velocity, and wind direction. These parameters are utilized to predict the dispersion centers of pollutants. Subsequently, the collected data undergoes a data cleaning process to rectify any issues, such as ensuring data consistency and handling invalid or missing values.

3.3. LSTM Algorithm Design

Data-driven time series prediction methods have shown their effectiveness in a variety of industrial production. Imad Alawe et al. investigated the role of LSTM models in flow load prediction [

34], while Shu et al. utilized LSTM models for interpersonal relationship recognition to address the challenge of recognizing human interactions in videos [

35].

The LSTM model controls the discarding or addition of information through the gate to achieve the functions of forgetting and remembering.

Figure 3 depicts a standard LSTM cell that has three gates: the forget gate, the input gate, and the output gate.

Forget gate: The forget gate is a function of the output ht-1 of the previous unit and the input

xt of this unit as input, and its output is ft, which is used to control the degree to which the state of the previous unit is forgotten. The concept of ft is presented as follows:

where

Wf is the weight matrix of the forget gate, and bf is the bias term of the forget gate.

Wf is a random initial value from 0 to 1, and the initial value of b is 0.

Input gate: The input gate and a tanh function work together to control the input of new information. The concept is presented as follows.

where

Wi is the weight matrix of the forget gate, bi is the bias term of the oblivion gate. Wi is a random initial value from 0 to 1, and the initial value of bi is 0.

Output gate: The output gate

ot is used to control the amount of the current cell state that is filtered out. The input state is activated first, and the output gate controls the amount of the input state that is filtered out. The concept of

ot is presented as follows:

where

Wo is the weight matrix of the forget gate,

bo is the bias term of the oblivion gate. Wo is a random initial value from 0 to 1, and the initial value of

bo is 0.

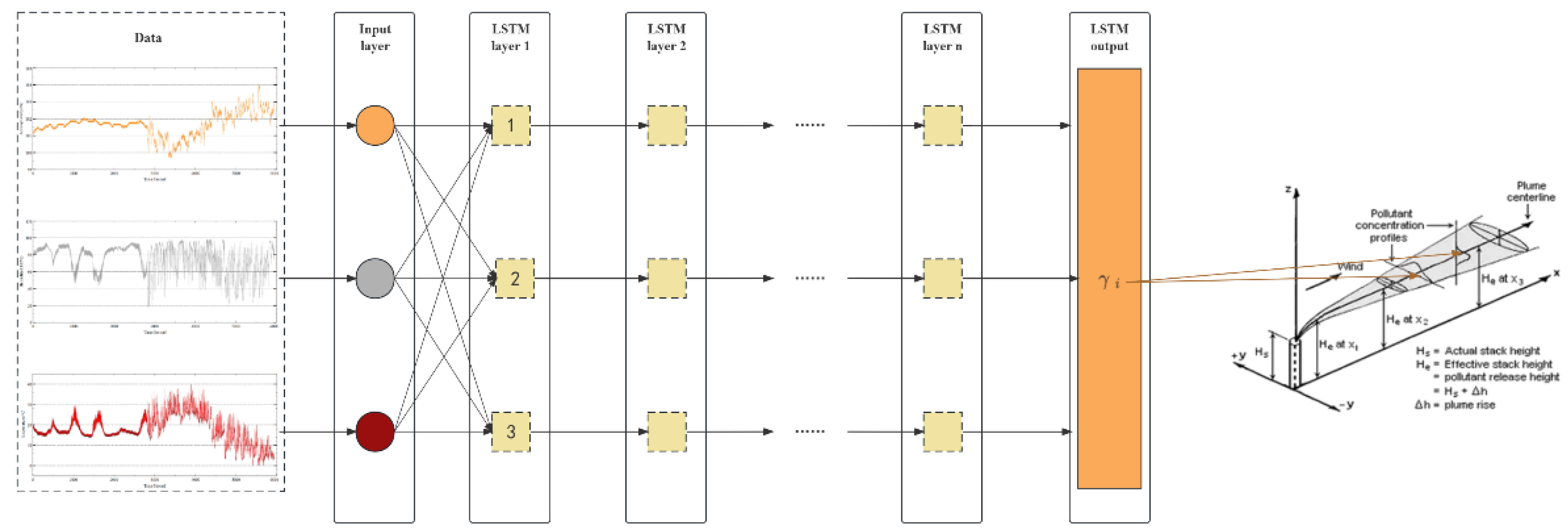

Although LSTM models have been used for large-scale air quality prediction, only a few LSTM models have been utilized for source dispersion traceability in chemical parks. In contrast to conventional air quality prediction methods, chemical parks face additional challenges, such as building occlusion and the need for timely traceability. To address these obstacles, we propose a novel approach that combines a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model with a genetic algorithm.

We train the dataset by deploying a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model on a distributed static EIPA node. In the previous section, we introduced our optimization object γi. After conducting a preliminary analysis, we found that γi is influenced by the wind field. However, its precise value is also affected by factors such as temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, and the value from the previous moment. Since the recurrent neural network (RNN) model overwrites its memory in an uncontrolled manner at each time step, with both gradient explosion and gradient disappearance, the LSTM model, on the other hand, modifies its memory in a more precise way: by using a special mechanism to selectively remember and update information, it is able to keep track of the information for a longer duration. Therefore, we introduce the LSTM model to train on γi.

During the phase of training the model, the central server employs a random selection process to choose several static nodes. These nodes are then determined to be suitable through the addition and deletion methods discussed in the preceding section. Subsequently, the global model is distributed to the selected nodes. Upon receiving the model, each static node utilizes the environmental data collected from the smart light pole to train the model. Once the local training is completed, the node uploads the model weights to the central server. The server then aggregates these model weights to generate a new global model.

3.4. Genetic Algorithm Optimization

The genetic algorithm is a probabilistic technique used for global optimization in search. It emulates the processes of replication, crossover, and mutation that take place in natural selection and heredity. By initiating with an initial population, the algorithm progresses towards a more favorable region in the search space through random selection, crossover, and mutation operations. This results in the generation of individuals who are better suited to the environment. Through multiple iterations, the algorithm eventually converges to a group of individuals that are best adapted to the environment, thereby identifying the optimal solution.

A typical genetic algorithm (GA) is structured as follows: initially, each individual within the solution space is encoded using binary code. Subsequently, an adaptive degree function F is proposed. New individuals are generated within the search space through the utilization of selection, crossover, and variation operators. Simultaneously, in order to prevent convergence to a local optimum, the fitness is compromised. This means that individuals with higher fitness have a greater likelihood of being selected, while those with lower fitness have a reduced chance of being chosen. The optimal solution is achieved through multiple iterations. The process of a standard genetic algorithm is depicted in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Genetic Algorithm |

Input: pop (initial populations), pc (crossover probability), pc (mutation probability)},

f (adaptability value), M (population size), g (number of iterations)

output: Individual (x,y) with the lowest adaptation |

Initializing the population new_pop

Do:

Do:

Randomly generate two random numbers between (0,1) and select two individuals

Randomly generate a random number l between (0,1)

if : l < pc

Crossover of two individual chromosomes to produce a new individual

Put two individuals into the new population new_pop

if : l < pb

Two individuals mutate to produce a new individual

Put two individuals into the new population new_pop

until |new_pop| = M

pop ← new_pop

until The number of iterations reached or individual adaptation to reach f

return (x,y) |

In the model inference stage, the smart light pole will use the sensor detection data on the pole to reason about the cloud model. And upload the Gaussian correction parameters of the area where the smart light pole is located to the cloud, which will use the gain factor to locate the pollution source by genetic algorithm.

With the LSTM model, we are able to obtain the next moment of

γi, and combined with the next moment of monitoring values, we can obtain the fitted diffusion center of the pollution source through the genetic algorithm. The objective function F is presented as follows:

where C is the concentration of the source, X and Y are the coordinates of the pollution source, Xi and Yi are the coordinates of the ith detection point, x and y are the coordinate compensation calculated by

γi, and Ci is the concentration value of the pollutant detected at the ith detection point.

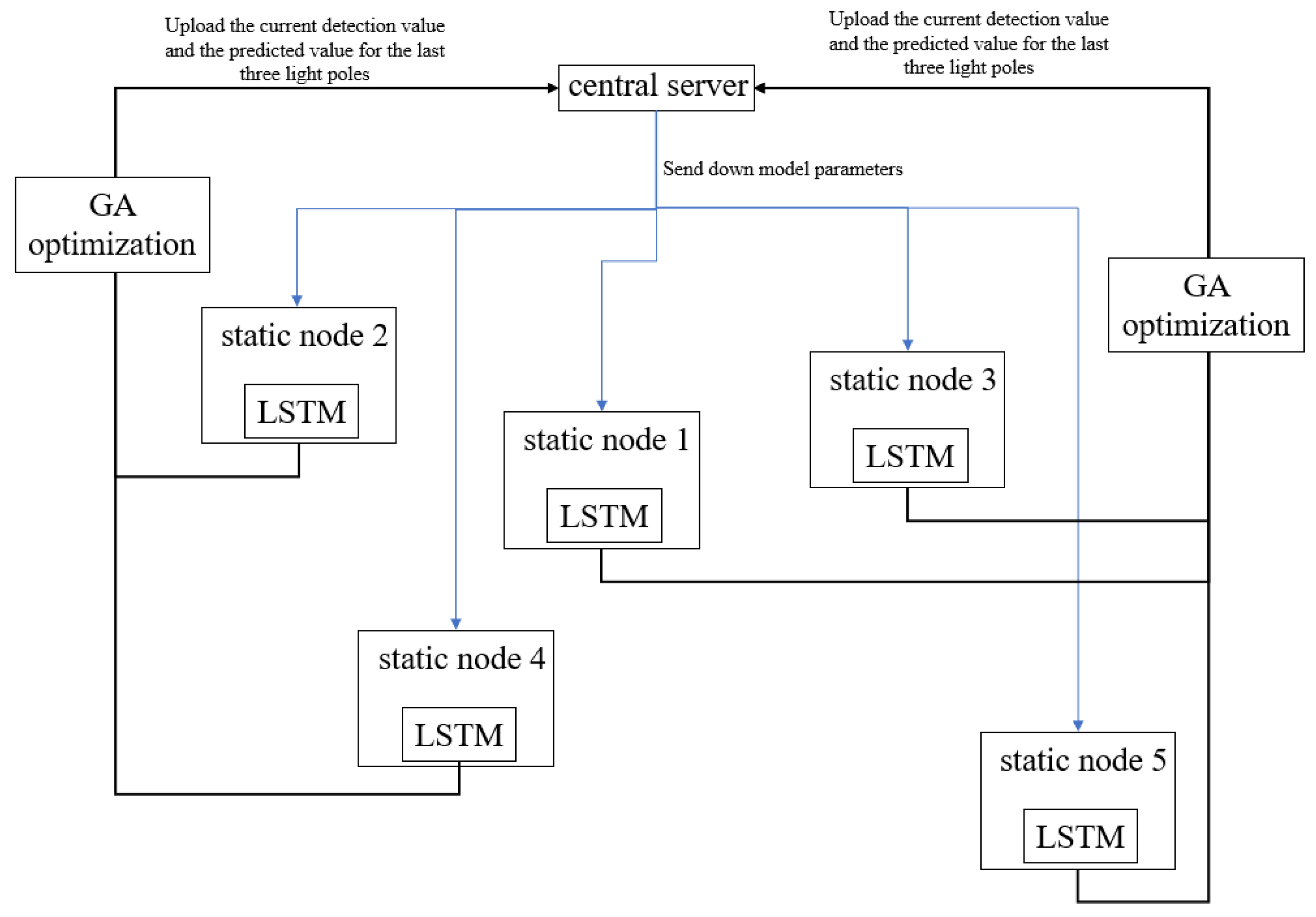

In an effort to enhance the stability and resilience of Federated Learning during the assessment of the global model provided by static EIPA nodes, we present an optimization approach that leverages the real-time monitoring values of adjacent light poles for validation purposes. Following the completion of each training iteration, the light poles make predictions on the monitoring data of the three closest neighboring light poles and transmit these predictions to the central server. The central server then requests the actual monitoring data from the respective light poles and evaluates the training outcomes using this methodology. A concrete example illustrating our algorithm is depicted in

Figure 4.

In this example, after completing one round of training, Node 1 will upload the detection data of the three smart light poles of Node 2, Node 3, and Node 4, which are predicted for the next moment. The central server will then request the current actual detection values from the above three light poles, compare them with the predicted data, update the Gaussian model, and retrain it.